Abstract

Cancer cell migration and invasion involves temporal and spatial regulation of actin cytoskeleton reorganization, which is regulated by the WASP family of proteins such as N-WASP (Neural- Wiskott Aldrich Syndrome Protein). We have previously shown that expression of N-WASP was increased under hypoxic conditions. In order to characterize the regulation of N-WASP expression, we constructed an N-WASP promoter driven GFP reporter construct, N-WASPpro-GFP. Transfection of N-WASPpro-GFP construct and plasmid expressing HiF1α (Hypoxia Inducible factor 1α) enhanced the expression of GFP suggesting that increased expression of N-WASP under hypoxic conditions is mediated by HiF1α. Sequence analysis of the N-WASP promoter revealed the presence of two hypoxia response elements (HREs) characterized by the consensus sequence 5′-GCGTG-3′ at -132 bp(HRE1) and at -662 bp(HRE2) relative to transcription start site (TSS). Site-directed mutagenesis of HRE1(-132) but not HRE2(-662) abolished the HiF1α induced activation of N-WASP promoter. Similarly ChIP assay demonstrated that HiF1α bound to HRE1(-132) but not HRE2(-662) under hypoxic condition. MDA-MB-231 cells but not MDA-MB-231KD cells treated with hypoxia mimicking agent, DMOG showed enhanced gelatin degradation. Similarly MDA-MB-231KD(N-WASPpro-N-WASPR) cells expressing N-WASPR under the transcriptional regulation of WT N-WASPpro but not MDA-MB-231KD(N-WASPproHRE1-N-WASPR) cells expressing N-WASPR under the transcriptional regulation of N-WASPproHRE1 showed enhanced gelatin degradation when treated with DMOG. Thus indicating the importance of N-WASP in hypoxia induced invadopodia formation. Thus, our data demonstrates that hypoxia-induced activation of N-WASP expression is mediated by interaction of HiF1α with the HRE1(-132) and explains the role of N-WASP in hypoxia induced invadopodia formation.

Keywords: N-WASP, Hypoxia, HRE, Invadopodia

Highlights

-

•

Expression of N-WASP expression is enhanced under hypoxia conditions.

-

•

N-WASP is essential for hypoxia induced invasion.

-

•

HiF1α binds to hypoxia response element (HRE) in N-WASP promoter.

-

•

HRE1 is essential for hypoxia induced invadopodia activity

1. Introduction

Hypoxia is a hallmark of various pathophysiological conditions such as cancer, tissue ischemia, inflammation and tumor growth [1]. Under hypoxia conditions, the expression of non-essential genes is downregulated to conserve cellular energy and only genes vital for cell survival are expressed [2]. Hypoxia provides a selective pressure for the tumor cell survival leading to resistance towards anti-cancer drugs and metastasis [3]. Hypoxia provides resistance against radiation and anti-cancer drugs through various mechanisms: (1) Reducing the cytotoxic activity of some drugs and radiation (2) Genetic instability leading to drug resistance (3) Altering cellular drug detoxification mechanisms [4].

Hypoxia inducible factors are heterodimeric transcriptional factors consisting of an alpha subunit (HiFα) and a beta subunit (HiFß). Out of the three isoforms of HiFα (HiF1α, HiF2α and HiF3α), HiF1α is the primary transcription factor responsible for inducing genes that promote cell survival under hypoxia [5]. HiF1ß (aryl hydrocarbon nuclear translocator, ARNT) is a constitutively expressed nuclear protein and its stability is independent of oxygen tension [6]. Under normoxia conditions, HiF1α is targeted for degradation by a family of 2-oxoglutarate (2-OG)-dependent dioxygenases termed as Prolyl hydroxylase domain (PHD). Under hypoxia conditions, HiF1α accumulates in the nucleus and binds to HiFβ to form a heterodimer which binds to the HREs in target genes [7]. HiF1α is essential for transcriptional regulation of genes responsible for angiogenesis, iron metabolism, glucose metabolism and cell proliferation/survival and overexpression of HiF1α increases metastasis in tumor cells [2].

During metastasis, cancer cells undergo morphological and physiological changes to promote cell invasion. Actin cytoskeleton reorganization is essential for the cancer cells to acquire migratory and invasive properties [8]. Actin and actin associated proteins are vital for the formation of migratory organelles such as filopodia, lamellipodia and invadopodia [9]. N-WASP is critical for the formation of actin-rich structures such as filopodia, dorsal ruffles, lamellipodia and invadopodia [10], [11], [12], [13], [14]. N-WASP belongs to the WASP/SCAR protein family, which activates the Arp2/3 complex and enhances actin polymerization [15]. N-WASP expression is upregulated in hypoxia induced epithelial mesenchymal transition (EMT) and expression of N-WASP is essential for metastasis [16], [17]. N-WASP has also been shown to localize in the nucleus and regulate transcription [18]. The importance of N-WASP in cancer cell invasion and migration can be attributed to its function in actin nucleation and extracellular matrix degradation [19], [20]. Expression of N-WASP is increased under hypoxia conditions [16] but the exact mechanism of upregulation of N-WASP expression remains uncharacterized.

In the present study, we have identified two HREs in the N-WASP promoter with the consensus sequence 5′-GCGTG-3′ and used an N-WASPPro-GFP reporter construct to show that HiF1α enhanced N-WASP promoter activity. Using site directed mutagenesis and ChIP, we have shown that the HRE1(-132) is essential for HiF1α mediated enhanced N-WASP promoter activity. Increased matrix degradation activity of breast cancer cells under DMOG treatment was abolished when N-WASP was knocked down or when N-WASP expression was under the regulation of N-WASP promoter with mutated HRE1 suggesting that the increased expression of N-WASP under hypoxic conditions is critical for matrix degradation and invasion.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Cell culture and treatments

HEK293T, HeLa and MDA-MB-231 cell lines were maintained in DMEM (Thermo Scientific) supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin in a 5%CO2 environment. For growth under hypoxia conditions, cells were kept under 95% N2/5% CO2 in a Modular Incubator Chamber (Billups-Rothenberg) for 24 h. For hypoxia studies, DMOG (Enzo Life Sciences) and YC-1 (Enzo Life Sciences) were dissolved in DMSO and used at a final concentration of 1 mM and 60 μM respectively.

2.2. Generation of stable cells by lentiviral transduction

N-WASP shRNA (NM_003941.2-1058s21c1) was cloned in pLJM1 plasmid (Addgene plasmid 19319). Four silent mutations were introduced into cDNA encoding Human N-WASP to render it resistant to N-WASP shRNA and cloned into pLJM1 to generate plasmid expressing N-WASPR construct. Wild type N-WASP promoter 1624 bp (N-WASPpro) and HRE1 mutant N-WASP promoter 1624 bp (N-WASPproHRE1) were cloned upstream of N-WASPR in pLJM1 plasmid to generate N-WASPpro-N-WASPR and N-WASPproHRE1-N-WASPR respectively. Lentivirus particles were generated using third-generation packaging constructs as described in [21]. Viral supernatant was used to transduce cells using polybrene followed by puromycin selection.

2.3. Plasmid constructs, transient transfection and GFP reporter assay

N-WASP promoter constructs were generated by PCR using the primers mentioned in Table S1 and cloned in pcDNA3.1HisC expression plasmid. HiF1α expression plasmid, pHIF1A-IRES-RFP was generated by cloning HIF1A gene upstream of an IRES element and RFP gene and control plasmid consisted of HIF1A gene with a STOP instead of the WT HIF1A. HEK293T cells were seeded in a 6-well plate and transfected with 4 µg of plasmid DNA using PEI when the cells reached 60–80% confluency. For co-transfection experiments, cells were co-transfected with equal amount of GFP (2 μg) plasmid and RFP plasmid (2 μg) for GFP/RFP normalization. For measuring fluorescent intensity, cells were lysed 36 h after using 350 μl of lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, 1% Triton X-100, 0.03% SDS, pH 7.4) and incubated on a shaker for 10 min in dark at room temperature. The lysate was centrifuged at 14,100g for 5 min to remove the cell debris. The supernatant was divided in three wells of a 96-well plate. The fluorescence intensity was measured using Tecan plate reader (GFP: Excitation-480 nm, Emission-530 nm and RFP: Excitation-550 nm, Emission 630 nm).

2.4. Real-time PCR

Total RNA was extracted from HeLa cells using Trizol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and converted to cDNA using M-MLV Reverse transcriptase (Promega). Real-time PCR amplifications were carried out using SYBR Green reagent (Invitrogen) in triplicates using primers listed in Table S2. The RT-PCR was performed on 7500 Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems) using the comparative CT method and the relative quantification of N-WASP expression was calculated [22].

2.5. Immunoblotting

Cell lysates were prepared, resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred onto nitrocellulose membrane [16]. The membrane was probed with appropriate primary antibody and secondary antibody conjugated with horse radish peroxidase (HRP). Primary antibodies used: Anti-HiF1α (BD Transduction Laboratories (610958)), Anti-N-WASP (in-house), Anti-GAPDH (Ambion (AM4300)). All the experiments were carried out in triplicate and densitometry was performed with ImageJ analysis software (NIH) [23]. Sample intensity was normalized to GAPDH intensity.

2.6. Immunofluorescence

Cells grown on coverslips were fixed, permeabilized and blocked as described [16]. The cells were incubated with appropriate primary antibodies (1:50) in blocking solution and incubated for 1 h. The cells were washed with PBS and incubated with fluorescent labelled secondary antibody for 1 h. The cells were washed with PBS and stained with Alexa594-conjugated phalloidin (Molecular probe (A12381)) to stain for actin. DAPI was used to stain the nuclei. Fluorescent images were captured with an inverted fluorescence microscope (Olympus IX51) fitted with Photometrics Cool Snap HQ2 camera.

2.7. Chromatin immunoprecipitation assay

HeLa cells were cultured in either normoxic or hypoxia-mimicking conditions (DMOG treatment) for 6 h. ChIP assay was performed as described [24]. Briefly, cells were fixed with 1% formaldehyde, quenched with 0.125 mM glycine, scraped in cold PBS and lysed in RIPA lysis buffer. The cross-linked chromatin suspension was sonicated to generate 0.5–0.8 kb fragments and diluted with IP dilution buffer. Supernatants were then incubated with 1 μg anti-HiF1α antibody or mouse IgG (Santa Cruz) at 4 °C for 4 h. DNA-protein-antibody complexes were pulled down using protein A/G beads. The beads were washed with low salt buffer, high salt buffer and LiCl wash buffer followed by two washes with TE buffer. Bound chromatin was eluted using 300 μl of elution buffer. DNA-protein cross-linking was reversed using 200 mM NaCl followed by RNase/proteinase K treatment. DNA was recovered by using phenol/chloroform/isoamyl alcohol extraction and subjected to PCR analysis by primers mentioned in Table S3.

2.8. Gelatin degradation assay

Coverslips coated with Oregon Green 488-conjugated fluorescent gelatin (Molecular Probes) were prepared as described [25]. Gelatin-coated coverslips were incubated with complete media for 1 h at 37 °C before plating cells. Cells (4×104/ml) were seeded on coated coverslips, incubated for 6 h with 1 mM DMOG at 37 °C and subsequently actin cytoskeleton was visualized vy staining with Alexa594-conjugated phalloidin. Invadopodia were identified by areas of matrix degradation characterized by loss of green fluorescence and showing co-localization with red actin spots. Invasion was quantified by calculating percentage of cells degrading gelatin. 30 cells were counted for each triplicate sample and the graph represents data of three independent experiments.

2.9. Bioinformatic analysis

HRE elements in selected DNA region were identified with MatInspector software [http://www.genomatix.de/solutions/genomatix-software-suite.html] [26].

2.10. Statistical analysis

Statistical significance analysis was performed using Student's t-test and p≤0.05 was considered statistically significant. Values presented in bar charts represent mean±S.D of at least three independent experiments.

3. Results

3.1. Expression of N-WASP is upregulated under hypoxic conditions and in the presence of hypoxia mimicking agent DMOG

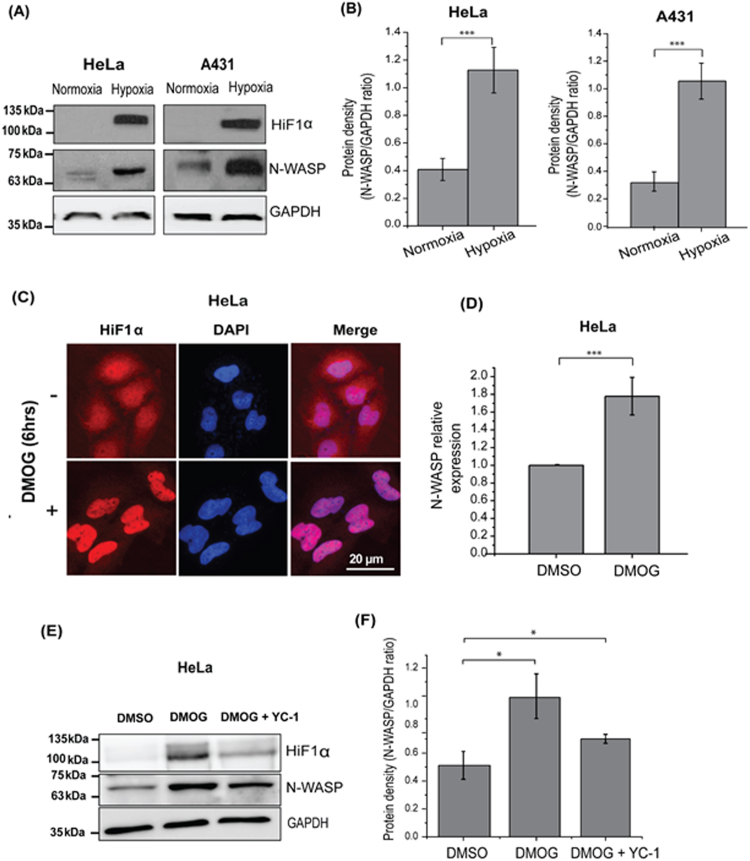

Expression of N-WASP has been shown to be increased under hypoxic conditions in A431 cells [16]. We tested whether expression of N-WASP is also upregulated in HeLa cells by incubating HeLa cells in a hypoxia chamber. Since HiF1α is degraded in presence of oxygen, the cells from the hypoxia chamber were lysed immediately using 2X SDS sample buffer. Western blot analysis showed that the expression of HiF1α was markedly increased in HeLa cells under hypoxia condition (Fig. 1A and B). Similarly, expression of N-WASP was found to be significantly upregulated in hypoxia treated A431 cells compared to normoxia cells (Fig. 1A and B).

Fig. 1.

Expression of N-WASP is enhanced under hypoxic conditions. (A) Lysates from HeLa and A431 cells grown under hypoxia conditions for 24 h at 37 °C were analyzed by immunoblotting to check the expression of HiF1α and N-WASP. GAPDH was used as a loading control (B) Densitometric analysis of N-WASP/GAPDH protein ratio in HeLa and A431 cells grown under hypoxia conditions for 24 h (C) HeLa cells grown in the presence or absence of 1 mM DMOG were immunostained to visualize HiF1α localization. (D) Real-time PCR analysis of N-WASP mRNA levels in cell grown in the presence or absence of 1 mM DMOG (E) Western blot analysis of N-WASP and HiF1α expression in presence of DMSO, DMOG and DMOG+YC-1 (F) Densitometric analysis of N-WASP/GAPDH protein ratio in cells grown in the presence of DMOG or DMOG+YC-1. * p<0.05; ***p<0.001.

Di-methyl-oxaloyl-glycine (DMOG) is a cell-permeable pan hydroxylase inhibitor which is commonly used to mimic hypoxia-mediated stabilization of HiF1α [27]. In presence of DMOG, HeLa cells showed increased expression of HiF1α within 6 h and the expression of HiF1α remained stable for 24 h with no visible cellular toxicity to DMOG. Exposure of HeLa cells to 1 mM DMOG for 6 h caused the nuclear localization of HiF1α (Fig. 1C). In order to verify if increased N-WASP expression was due to increased transcription, total RNA from DMOG treated cells was used to analyze expression of N-WASP by Real Time PCR. DMOG treated cells showed increased N-WASP mRNA levels (Fig. 1D). Similarly HeLa cells treated with DMOG showed significant increase in expression of HiF1α as compared to the control DMSO treated cells (Fig. 1E). Thus the increased expression of N-WASP in DMOG treated cells was consistent with the observations using the hypoxia chamber and is due to increased transcription (Fig. 1D). To confirm that the increased expression of N-WASP in presence of DMOG is due to HiF1α, HiF1α inhibitor YC-1 was used. YC-1 downregulates HiF1α post-translationally by functional inactivating HiF1α [28]. As shown in Fig. 1E-F, YC-1 blocked upregulation of N-WASP expression despite the presence of DMOG suggesting that hypoxia-induced N-WASP expression is due to HiF1α.

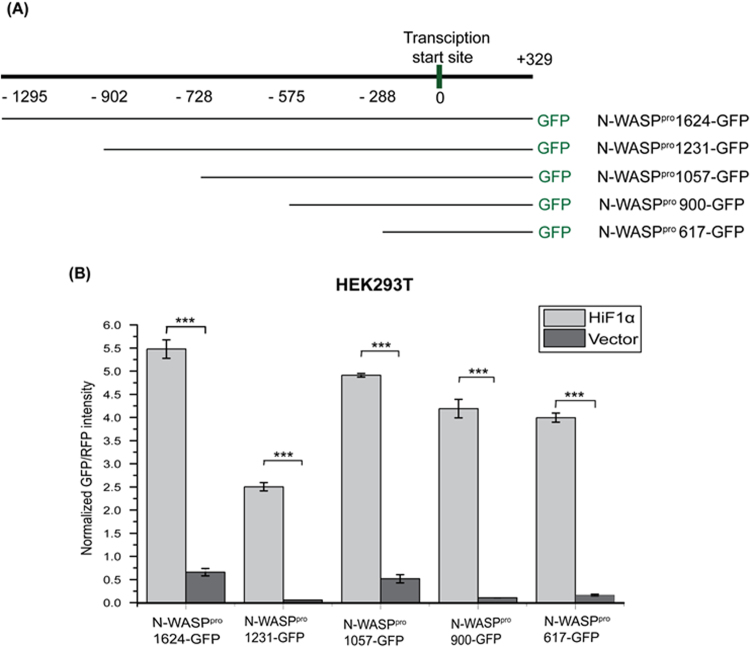

3.2. N-WASP promoter activity is enhanced in the presence of HiF1α

Expression of HiF1α and DNA-binding activity of HiF1α has been shown to increase exponentially with decreasing oxygen tension in HeLa cells [29]. In order to delineate the DNA elements in N-WASP which are responsible for HiF1α regulated expression, we generated a series of deletion fragments of N-WASP promoter and cloned the fragments upstream of GFP gene in an expression vector (Fig. 2A). We transfected pN-WASPpro1624-GFP together with plasmid expressing HiF1α-IRES-RFP into HEK293T cells and quantified the GFP and RFP fluorescence using a plate reader. Control plasmid consists of HiF1α with a STOP codon, thus does not express HiF1α which was confirmed by western blot analysis (data not shown). GFP/RFP normalization was performed to normalise transfection efficiency of the different constructs. We found that expression of GFP from N-WASPpro1624-GFP was enhanced in the presence of HiF1α (Fig. 2B) suggesting that HiF1α regulates the activity of N-WASP promoter. We subsequently tested all the five constructs and found that expression of HiF1α enhanced N-WASP promoter activity and the results suggest that enhanced expression of N-WASP under hypoxia condition may be due to activation of N-WASP promoter by HiF1α. The results also suggest that at least 1 functional HRE is found in the smallest N-WASP promoter fragment, N-WASPpro617.

Fig. 2.

Increased N-WASP expression in hypoxia is dependent on HiF1α. (A) N-WASP promoter deletion constructs as indicated were generated and cloned upstream of a GFP gene. (B) HEK293T cells were co-transfected with 2 µg of N-WASPpro-GFP constructs expressing GFP and 2 µg of HiF1α-IRES-RFP or HiF1α-STOP-IRES-RFP constructs expressing RFP. GFP and RFP fluorescence intensity was quantified as described in Materials and Methods and GFP/RFP values were plotted (N=3). ***p<0.001.

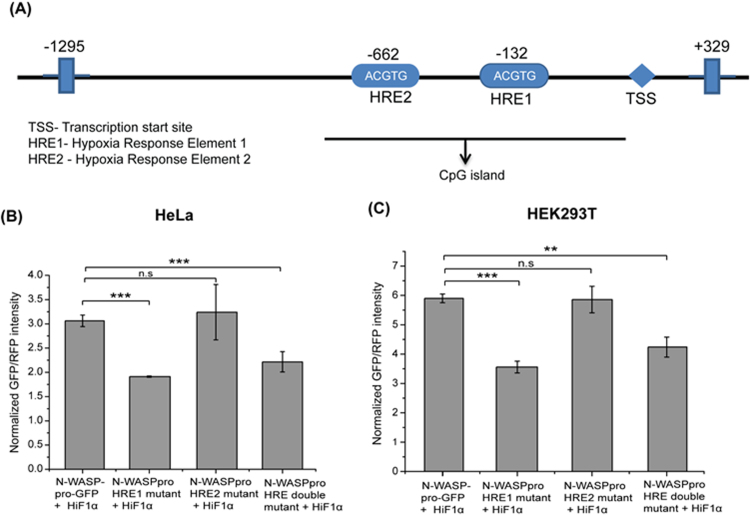

3.3. Identification of two putative HREs in N-WASP promoter

HiF1α binds to the consensus HRE sequence present in the promoter of target genes and enhances the target gene expression [30]. Bioinformatic analysis of the sequence upstream of the WASL gene revealed the presence of two putative HREs that resembled the canonical A/G/CGTG sequence (Fig. 3A). The first potential HiF1α binding site, HRE1 was at position -132 (in the N-WASPpro-617) and the second site, HRE2 at position -662 relative to the TSS. In order to determine the functionality of HRE1 and HRE2 in the N-WASP promoter, we generated site directed mutants of N-WASP promoter with mutations in either of the HREs or both the HREs via overlap extension PCR. The consensus HRE sequence was mutated from 5′-GCGTG-3′ to 5′-GAAAG-3′. HeLa cells were transiently co-transfected with the N-WASP promoter constructs and HiF1α expression plasmid and relative fluorescence intensity was measured (Fig. 3B). Wild Type N-WASP promoter activity was enhanced in the presence of HiF1α (Fig. 3B). The activity of N-WASP promoter with HRE1(-132) mutated was significantly decreased in the presence of HiF1α whereas, the activity of N-WASP promoter with HRE2(-662) mutated remained unchanged. N-WASP promoter with both HREs mutated (double mutant HRE) showed a decreased activity in presence of HiF1α similar to N-WASP promoter with HRE1(-132) mutated. Similar results were observed in HEK293T cells (Fig. 3C) indicating that though there are 2 HREs, only HRE1(-132) is functional and binds to HiF1α and mutating the consensus sequence abolished the binding site for HiF1α resulting in decreased promoter activity.

Fig. 3.

Presence of hypoxia response elements in N-WASP promoter. (A) Schematic diagram of Human N-WASP promoter region encompassing ~1295 bp upstream of the start codon showing presence of two HRE elements i.e. HRE1(-132) and HRE2(-662). (B) N-WASP promoter constructs (WT, HRE1 mutant, HRE2 mutant or HRE1 & HRE2 double mutant) were transfected together with HiF1α into HeLa (B) or HEK293T cells (C). GFP and RFP fluorescence intensity was quantified as described in Materials and Methods and GFP/RFP were plotted (N=3). **p<0.01; ***p<0.001.

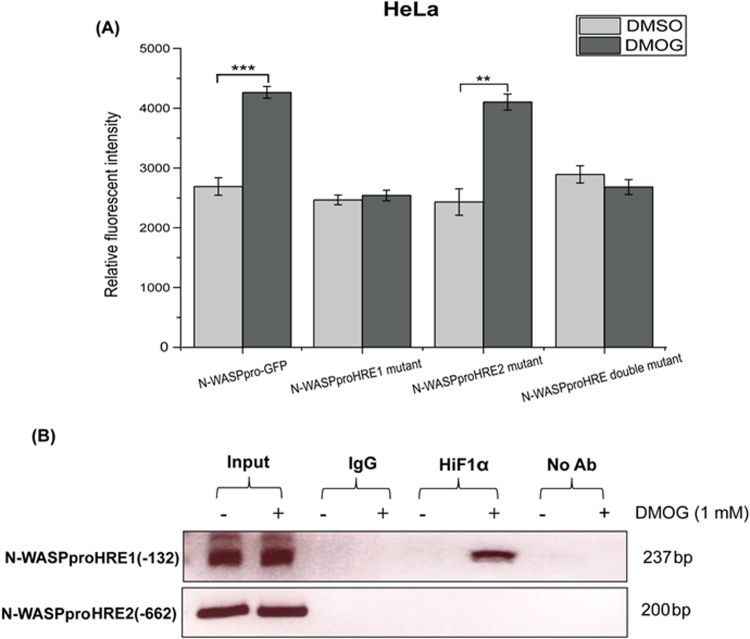

3.4. HiF1α binds to HRE1(-132) in N-WASP promoter

The site directed mutational analysis indicates that mutating HRE1(-132) significantly reduced HiF1α induced N-WASP promoter activity in HeLa and HEK293T cells (Fig. 3). In order to ascertain that HRE1(-132) is responsible for hypoxia induced increased N-WASP expression, we tested the effect of mutating N-WASP promoter HREs in the presence of DMOG. Hence, HeLa cells were transiently co-transfected with the N-WASP promoter constructs (wild type and HRE mutants) and were treated with 1 mM DMOG for 6 h. Treatment with DMOG enhanced the activity of wild type promoter but not the activity of HRE1(-132) mutant (Fig. 4A). The activities of HRE2(-662) mutant remained unchanged with/without DMOG. This suggests that HRE1(-132) may be the only functional binding site of HiF1α in N-WASP promoter, whereas HRE2(-662) may not be involved in hypoxia-mediated upregulation of N-WASP promoter activity.

Fig. 4.

HiF1α interacts with HRE1(-132) of the N-WASP promoter. (A) HeLa cells were transfected with wild type N-WASP promoter or N-WASP promoter with mutations in HREs. Cells were incubated with/without 1 mM DMOG for 6 h and the fluorescence intensity was quantified, normalized and plotted (B) ChIP assay was performed using HeLa cells with/without DMOG treatment using anti-HiF1α , IgG and No antibody. Crosslinked chromatin was used as the input. PCR primers flanking HRE1(-132) and HRE2(-662) in N-WASP promoter were used for PCR amplification. **p<0.01; ***p<0.001.

ChIP assay was performed to check for an in vivo binding of HiF1α to the HREs in N-WASP promoter. HeLa cells were grown to 80% confluency and cultured for 6 h with/without DMOG. Chromatin was crosslinked and ChIP assay was performed as described in Materials and Methods. DNA fragments brought down by HiF1α were used to amplify either the region flanking HRE1(-132) or HRE2(-662) in N-WASP promoter. Negative control reaction was set up using a primer flanking a region in exon 1 of N-WASP. PCR amplification was observed for region containing HRE1(-132) in DMOG-treated cells immunoprecipitated with HiF1α antibody and input (Fig. 4B). In contrast, there was no significant PCR amplification of region flanking HRE2(-662) in the N-WASP promoter. No significant PCR amplification was observed for mouse IgG as well as no-antibody control indicating the specificity of the interaction between HiF1α and HRE1(-132). These findings confirm that HiF1α specifically binds to the HRE1(-132) in the N-WASP promoter under hypoxia conditions.

3.5. N-WASP is important for hypoxia-induced invadopodia formation

Hypoxia leads to upregulation of HiF1α which has been linked to increased metastatic potential [31]. HiF1α has been shown to be necessary for hypoxia induced invadopodia formation [32] and N-WASP is important for invadopodia formation and activity [11]. Hence, we assessed the role of increased N-WASP expression during hypoxia in invadopodia formation by performing gelatin degradation assay in HeLa cells. However, no gelatin degradation was observed for HeLa cells (data not shown) probably due to low ECM degradative capacity of HeLa cells. MDA-MB-231 cell line is an invasive breast carcinoma cell line expressing high levels of MMPs and hence used extensively to study invadopodia activity in the gelatin degradation assay [33]. Expression of N-WASP was found to be significantly upregulated in DMOG treated MDA-MB-231 cells compared to DMSO treated cells (Fig. 5A and B). In order to determine the role of N-WASP in invadopodia during hypoxia, we generated N-WASP knockdown stable cells (MDA-MB-231KD) and control cells with empty pLJM1 plasmid (MDA-MB-231Vect) by lentiviral transduction. Knockdown cells with N-WASP reconstitution were referred to as MDA-MB-231KD+N-WASPR and knockdown cells with empty pLJM1 plasmid were referred to as MDA-MB-231KD+Vect (Fig. 5C and D).

Fig. 5.

N-WASP is critical for hypoxia induced invadopodia formation. (A) Western blot analysis of N-WASP and HiF1α expression in MDA-MB-231 cells grown in presence of DMOG for 6 h (B) Densitometric analysis of N-WASP/GAPDH protein ratio in MDA-MB-231 cells treated with DMOG (C) Western blot analysis of N-WASP expression in control cells (MDA-MB-231Vect), N-WASP knockdown cells reconstituted with N-WASPR (MDA-MB-231KD+N-WASPR) and N-WASP knockdown cells with Vector (MDA-MB-231KD+Vect) (D) Densitometric analysis of N-WASP/GAPDH protein ratio of western blot in panel C. (E) Cells (MDA-MB-231Vect, MDA-MB-231KD+Vect and MDA-MB-231KD+N-WASPR) were seeded on fluorescent gelatin coated coverslips and treated with 1 mM DMOG for 6 h, fixed and immunostained. Degraded areas of fluorescent gelatin along with staining for F-actin (red) indicate presence of invadopodia. Images were taken using 40X oil objective lens. Presence of actin dots (red) with underlying degraded gelatin (black areas) was used to identify degradation areas (red dots on gelatin degraded areas). Arrows indicate areas of gelatin degradation (F) Percentage of cells (Panel E) with invadopodia was counted for DMSO and DMOG treated cells and 30 cells were analyzed for each triplicate sample (N=3) *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001.

MDA-MB-231 cells (Control, KD+Vect and KD+N-WASPR), on gelatin matrix were subjected to DMOG treatment and the actin cytoskeleton was visualized with fluorescent labelled phalloidin. Treatment of control cells with DMOG increased the number of invadopodia as can be seen by enhanced degradation of gelatin (indicated by arrows) while MDA-MB-231KD cells had reduced percentage of cells forming invadopodia (Fig. 5E). Interestingly, DMOG treatment did not increase the number of invadopodia forming cells in MDA-MB-231KD cells as the number of cells with/without DMOG was similar. Reconstitution of N-WASP in knockdown cells rescued the gelatin degradation capacity of MDA-MB-231KD cells which was further enhanced in presence of DMOG (Fig. 5E and F). This suggests that N-WASP plays a vital role in hypoxia induced invadopodia formation.

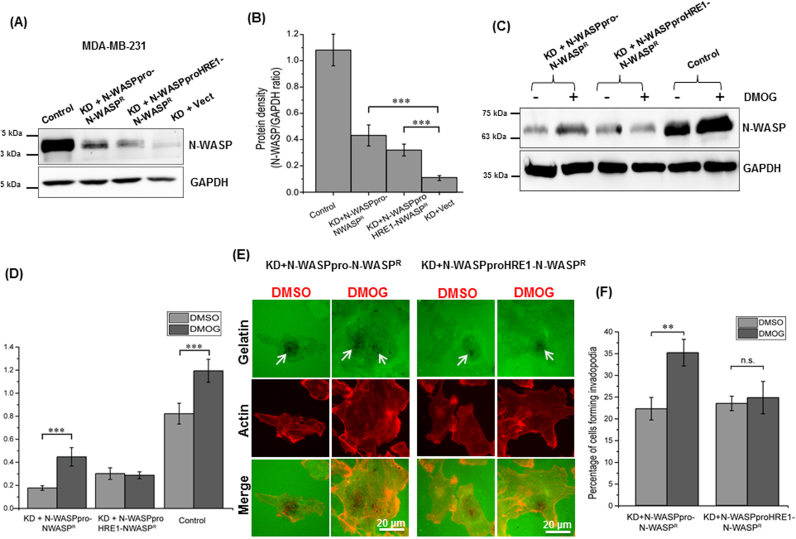

In order to check if HRE1 in N-WASP promoter is critical for N-WASP expression in hypoxia-induced invadopodia activity, we generated two constructs in which the expression of shRNA resistant N-WASP was under the transcription regulation of WT N-WASP promoter of 1624 bp, N-WASPpro-N-WASPR, or N-WASP promoter of 1624 bp with HRE1 site mutated, N-WASPproHRE1-N-WASPR. These two constructs were used to generate lentivirus and infect N-WASP knockdown stable cells to generate MDA-MB-231KD(N-WASPpro-N-WASPR) and MDA-MB-231KD(N-WASPproHRE1-N-WASPR) and the expression was analyzed by immunoblotting (Fig. 6A and B). Induction with DMOG was found to enhance N-WASP expression in cells expressing N-WASPR under the regulation of WT N-WASPpro, but not in cells expressing N-WASPR under the regulation of N-WASPproHRE1 (Fig. 6C and D). This suggests that mutating HRE1 abolished DMOG induced upregulation of N-WASP expression. Treatment of MDA-MB-231KD(N-WASPpro-N-WASPR) cells with DMOG caused a small but significant increase in percentage of cells forming invadopodia as can be seen by enhanced degradation of gelatin (indicated by arrows) (Fig. 6E and F). DMOG treatment did not increase the number of invadopodia forming cells in MDA-MB-231KD(N-WASPproHRE1-N-WASPR) cells as the number of cells with/without DMOG was similar. Thus the HRE1 site in N-WASP promoter is critical for increased expression of N-WASP and activity during hypoxia induced invasion.

Fig. 6.

HRE1 in N-WASP promoter is critical for N-WASP expression and invadopodium-mediated invasion in MDA-MB-231 cells under hypoxic condition. (A) Western blot analysis of N-WASP expression in MDA-MB-231Vect (Control), MDA-MB-231KD(N-WASPpro-N-WASPR), MDA-MB-231KD(N-WASPproHRE1-N-WASPR), MDA-MB-231KD(Vect) cells (B) Densitometric analysis of N-WASP/GAPDH protein ratio in the cells in panel A (C) Western blot analysis of N-WASP expression in MDA-MB-231KD(N-WASPpro-N-WASPR), MDA-MB-231KD(N-WASPproHRE1-N-WASPR) and MDA-MB-231Vect (Control) cells in the presence of 1 mM DMOG (6 h) (D) Densitometric analysis of N-WASP/GAPDH protein ratio in panel C (E) Cells (MDA-MB-231KD with N-WASPpro-N-WASPR or N-WASPproHRE1-N-WASPR) were seeded on fluorescent gelatin coated coverslips and treated with 1 mM DMOG for 6 h, fixed and immunostained. Degraded areas of fluorescent gelatin along with staining for F-actin (red) indicate presence of invadopodia. Images were taken using 40× oil objective lens. Presence of actin dots (red) with underlying degraded gelatin (black areas) was used to identify degradation areas (red dots on gelatin degraded areas). Arrows indicate areas of gelatin degradation (F) Percentage of cells from panel E, with invadopodia was counted for DMSO and DMOG treated cells and 30 cells were analyzed for each triplicate sample (N=3) **p<0.01; ***p<0.001.

4. Discussion

Hypoxia causes tumor cells to undergo molecular changes by activating signaling pathways critical for adapting to an oxygen deprived environment leading to enhanced cell invasion and migration [34]. Members of the WASP family of proteins are critical for actin polymerization which is essential for cell motility and invasion [35]. N-WASP regulates actin cytoskeleton by activating the Arp2/3 complex [36]. A number of studies have demonstrated the importance of N-WASP in cancer cell motility and cell adhesion [17], [19], [37], [38]. Expression of N-WASP is upregulated during hypoxia induced EMT suggesting that N-WASP may play a role in actin remodeling events during metastasis [16], [39]. N-WASP is also responsible for recruiting MT1-MMP from the late endosomes into invasive pseudopods during metastasis [19].

We find that expression of N-WASP was enhanced under hypoxia conditions in HeLa cells similar to A431 cells [16]. Hypoxia conditions were mimicked by using 1 mM DMOG, which stabilizes HiF1α expression under normoxia conditions and N-WASP promoter activity was found to be enhanced in presence of DMOG (Fig. 2B). The enhancement of N-WASP expression by DMOG was reduced by YC-1, an inhibitor of HiF1α (Fig. 1E). DMOG does not affect the levels of HiF2α and induces invadopodia specifically via HiF1α [32]. Expression of N-WASP was enhanced at protein as well as mRNA level under hypoxic conditions (Fig. 1A–D). Transfection of N-WASPpro-GFP construct with HiF1α expression plasmid enhanced N-WASP promoter activity (Fig. 2B) confirming the role of HiF1α in regulating N-WASP expression under hypoxic conditions. Hence, N-WASP promoter was analyzed by Bioinformatics which identified two putative HREs (5′-GCGTG-3′) at position -132 and -662 relative to the TSS. Functional analysis of site-directed mutants showed that HRE1(-132) is functional as mutating HRE1(-132) caused a decrease in HiF1α enhancement of N-WASP promoter activity. Mutating HRE2 did not affect the N-WASP promoter activity suggesting that HRE2(-662) may not be functional even though it has the consensus HRE sequence. ChIP assay confirmed HRE1(-132) as the binding site for HiF1α (Fig. 4B) which is responsible for hypoxia-induced activation of N-WASP promoter. Thus, our results show that N-WASP expression is enhanced under hypoxia conditions due to the direct binding of HiF1α to the HRE1(-132) in the N-WASP promoter.

A number of genes which are important for cancer invasion are regulated by HiF1α [32], [40]. Studies in MDA-MB231 cells have shown that overexpression of HiF1α increases invadopodia formation and enhanced matrix degradative capacity compared to control (normoxia) cells. N-WASP is vital for invadopodia function and hypoxia environment induces formation of invadopodia [11], [41]. Also, HiF1α regulates expression of N-WASP in hypoxia conditions which suggests a role of N-WASP in hypoxia-induced invadopodia formation. It is possible that HiF1α may induce invadopodia formation through multiple cytoskeletal pathways. Studies in human glioblastoma cell lines have identified c-Src and N-WASP as the key mediators for enhanced cell motility under low oxygen conditions suggesting a crucial role in mediating the molecular pathogenesis of hypoxia induced-enhanced brain invasion by gliomas [42]. Another WASP family member WAVE3 was shown to be critical for hypoxia mediated invasion and its promoter contains 2 functional HREs which bind to HiF1α under hypoxia condition. WAVE2 promoter did not contain any HRE sequence, whereas WAVE1 promoter contains one HRE sequence at ~1200 bp upstream of transcription initiation site [43]. Similarly, other actin cytoskeleton regulators such as Cdc42, Arp2, β-PIX have been shown to be upregulated in DMOG-treated MDA-MB-231 cells using PCR array. β-PIX promoter sequence consists of two putative HREs and β-PIX is essential for invadopodia formation under hypoxia conditions [32]. Sequence analysis of ~1200 bp upstream of transcription initiation site for Cdc42 and Arp2 genomic sequence showed presence of 2 HRE sequences for Cdc42 and none for Arp2. Whether the HRE sequences in WAVE1, Cdc42 and β-PIX promoter binds directly to HiF1α remains to be investigated.

The increased levels of N-WASP in hypoxia, along with the requirement of N-WASP for invadopodia activity indicated that N-WASP may be regulating hypoxia-induced invadopodia formation. MDA-MB-231KD cells were generated and a gelatin degradation assay was performed using MDA-MB-231Vect and MDA-MB-231KD cells. It was found that DMOG treatment enhanced the gelatin degradative capacity of MDA-MB-231 cells which was consistent with previous reports [32]. Knockdown of N-WASP significantly reduced the number of cells forming invadopodia under hypoxic conditions (Fig. 5E) and reconstitution of N-WASP in knockdown cells restored the number of invadopodia forming cells similar to control cells (Fig. 5E and F). N-WASP knockdown cells expressing N-WASP under the transcriptional regulation of wild type N-WASP promoter showed enhanced N-WASP expression and enhanced gelatin degradation in presence of DMOG. However, knockdown cells expressing N-WASP under the transcriptional regulation of HRE1 mutant N-WASP promoter did not show any significant change in N-WASP expression as well as gelatin degradation in presence of DMOG (Fig. 6E and F). This validated our hypothesis that HRE1 in N-WASP promoter is critical in promoting invasion under hypoxia conditions by regulating the formation of invadopodia.

In summary we have shown that N-WASP promoter, a DNA fragment of 1624 bp is sufficient to recapitulate hypoxia responsive activity. Our data shows that the expression of N-WASP is enhanced under hypoxic conditions by binding of HiF1α to the HRE1(-132) in N-WASP promoter, which regulates hypoxic induction of N-WASP expression. Site-directed mutagenesis and ChIP assay helped to understand the mechanism of regulation of N-WASP by HiF1α. Enhanced N-WASP under hypoxia conditions was found to be important for invadopodia activity. Thus, our findings demonstrate the role of HiF1α in regulating N-WASP expression and tumor invasion.

Author contributions

AS: Carried out the experiments and Drafting of the manuscript. TT: Designed the study, analyzed and interpreted the results and wrote the manuscript.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by the following grants: Academic Research Fund Tier 1 (MOE), RG46/13 and Academic Research Fund Tier 2 (MOE 2013-T2-2-031).

Footnotes

Transparency document associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.bbrep.2016.10.010.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.bbrep.2016.10.010.

Appendix A. Transparency document

Supplementary material

.

Appendix B. Supplementary material

Supplementary material

.

References

- 1.Ryan H.E., Poloni M., McNulty W., Elson D., Gassmann M., Arbeit J.M., Johnson R.S. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha is a positive factor in solid tumor growth. Cancer Res. 2000;60:4010–4015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ke Q., Costa M. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF-1) Mol. Pharmacol. 2006;70:1469–1480. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.027029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sullivan R., Graham C.H. Hypoxia-driven selection of the metastatic phenotype. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2007;26:319–331. doi: 10.1007/s10555-007-9062-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Teicher B.A. Hypoxia and drug resistance. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 1994;13:139–168. doi: 10.1007/BF00689633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang G.L., Jiang B.H., Rue E.A., Semenza G.L. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 is a basic-helix-loop-helix-pas heterodimer regulated by cellular O-2 tension. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1995;92:5510–5514. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.12.5510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jaakkola P., Mole D.R., Tian Y.M., Wilson M.I., Gielbert J., Gaskell S.J., von Kriegsheim A., Hebestreit H.F., Mukherji M., Schofield C.J., Maxwell P.H., Pugh C.W., Ratcliffe P.J. Targeting of HIF-alpha to the von Hippel-Lindau ubiquitylation complex by O2-regulated prolyl hydroxylation. Science. 2001;292:468–472. doi: 10.1126/science.1059796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maxwell P.H. Hypoxia-inducible factor as a physiological regulator. Exp. Physiol. 2005;90:791–797. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2005.030924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mareel M., Oliveira M.J., Madani I. Cancer invasion and metastasis: interacting ecosystems. Virchows Arch. 2009;454:599–622. doi: 10.1007/s00428-009-0784-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yilmaz M., Christofori G. EMT, the cytoskeleton, and cancer cell invasion. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2009;28:15–33. doi: 10.1007/s10555-008-9169-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miki H., Sasaki T., Takai Y., Takenawa T. Induction of filopodium formation by a WASP-related actin-depolymerizing protein N-WASP. Nature. 1998;391:93–96. doi: 10.1038/34208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yamaguchi H., Lorenz M., Kempiak S., Sarmiento C., Coniglio S., Symons M., Segall J., Eddy R., Miki H., Takenawa T., Condeelis J. Molecular mechanisms of invadopodium formation: the role of the N-WASP–Arp2/3 complex pathway and cofilin. J. Cell Biol. 2005;168:441–452. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200407076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lorenz M., Yamaguchi H., Wang Y., Singer R.H., Condeelis J. Imaging sites of N-wasp activity in lamellipodia and invadopodia of carcinoma cells. Curr. Biol. 2004;14:697–703. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Legg J.A., Bompard G., Dawson J., Morris H.L., Andrew N., Cooper L., Johnston S.A., Tramountanis G., Machesky L.M. N-WASP involvement in dorsal ruffle formation in mouse embryonic fibroblasts. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2007;18:678–687. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-06-0569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schell C., Baumhakl L., Salou S., Conzelmann A.C., Meyer C., Helmstadter M., Wrede C., Grahammer F., Eimer S., Kerjaschki D., Walz G., Snapper S., Huber T.B. N-wasp is required for stabilization of podocyte foot processes. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2013;24:713–721. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2012080844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Machesky L.M., Mullins R.D., Higgs H.N., Kaiser D.A., Blanchoin L., May R.C., Hall M.E., Pollard T.D. Scar, a WASp-related protein, activates nucleation of actin filaments by the Arp2/3 complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:3739–3744. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.7.3739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Misra A., Pandey C., Sze S.K., Thanabalu T. Hypoxia activated EGFR signaling induces epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT) PloS One. 2012;7:e49766. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0049766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gligorijevic B., Wyckoff J., Yamaguchi H., Wang Y.R., Roussos E.T., Condeelis J. N-WASP-mediated invadopodium formation is involved in intravasation and lung metastasis of mammary tumors. J. Cell Sci. 2012;125:724–734. doi: 10.1242/jcs.092726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu X., Yoo Y., Okuhama N.N., Tucker P.W., Liu G., Guan J.-L. Regulation of RNA-polymerase-II-dependent transcription by N-WASP and its nuclear-binding partners. Nat. Cell Biol. 2006;8:756–763. doi: 10.1038/ncb1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yu X., Machesky L.M. Cells assemble invadopodia-like structures and invade into matrigel in a matrix metalloprotease dependent manner in the circular invasion assay. PloS One. 2012;7:e30605. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yu X., Zech T., McDonald L., Gonzalez E.G., Li A., Macpherson I., Schwarz J.P., Spence H., Futo K., Timpson P., Nixon C., Ma Y., Anton I.M., Visegrady B., Insall R.H., Oien K., Blyth K., Norman J.C., Machesky L.M. N-WASP coordinates the delivery and F-actin-mediated capture of MT1-MMP at invasive pseudopods. J. Cell Biol. 2012;199:527–544. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201203025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Massey A.C., Follenzi A., Kiffin R., Zhang C., Cuervo A.M. Early cellular changes after blockage of chaperone-mediated autophagy. Autophagy. 2008;4:442–456. doi: 10.4161/auto.5654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rao N.V., Shashidhar R., Bandekar J.R. Induction, resuscitation and quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction analyses of viable but nonculturable Vibrio vulnificus in artificial sea water. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2014;30:2205–2212. doi: 10.1007/s11274-014-1640-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schneider C.A., Rasband W.S., Eliceiri K.W. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat. Methods. 2012;9:671–675. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pescador N., Cuevas Y., Naranjo S., Alcaide M., Villar D., Landazuri M.O., Del Peso L. Identification of a functional hypoxia-responsive element that regulates the expression of the egl nine homologue 3 (egln3/phd3) gene. Biochem. J. 2005;390:189–197. doi: 10.1042/BJ20042121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martin K.H., Hayes K.E., Walk E.L., Ammer A.G., Markwell S.M., Weed S.A. Quantitative measurement of invadopodia-mediated extracellular matrix proteolysis in single and multicellular contexts. J. Vis. Exp. 2012:e4119. doi: 10.3791/4119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cartharius K., Frech K., Grote K., Klocke B., Haltmeier M., Klingenhoff A., Frisch M., Bayerlein M., Werner T. MatInspector and beyond: promoter analysis based on transcription factor binding sites. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:2933–2942. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Milkiewicz M., Pugh C.W., Egginton S. Inhibition of endogenous HIF inactivation induces angiogenesis in ischaemic skeletal muscles of mice. J. Physiol. 2004;560:21–26. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.069757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li S.H., Shin D.H., Chun Y.S., Lee M.K., Kim M.S., Park J.W. A novel mode of action of YC-1 in HIF inhibition: stimulation of FIH-dependent p300 dissociation from HIF-1{alpha} Mol. Cancer Ther. 2008;7:3729–3738. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jiang B.H., Semenza G.L., Bauer C., Marti H.H. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 levels vary exponentially over a physiologically relevant range of O-2 tension. Am. J. Physiol.: Cell Physiol. 1996;271:C1172–C1180. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1996.271.4.C1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Semenza G.L., Nejfelt M.K., Chi S.M., Antonarakis S.E. Hypoxia-inducible nuclear factors bind to an enhancer element located 3′ to the human erythropoietin gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1991;88:5680–5684. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.13.5680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harris A.L. Hypoxia--a key regulatory factor in tumour growth. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2002;2:38–47. doi: 10.1038/nrc704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Md Hashim N.F., Nicholas N.S., Dart A.E., Kiriakidis S., Paleolog E., Wells C.M. Hypoxia-induced invadopodia formation: a role for beta-PIX. Open Biol. 2013;3:120159. doi: 10.1098/rsob.120159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Murphy D.A., Courtneidge S.A. The ‘ins’ and ‘outs’ of podosomes and invadopodia: characteristics, formation and function. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2011;12:413–426. doi: 10.1038/nrm3141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Coutts A.S., Pires I.M., Weston L., Buffa F.M., Milani M., Li J.L., Harris A.L., Hammond E.M., La Thangue N.B. Hypoxia-driven cell motility reflects the interplay between JMY and HIF-1 alpha. Oncogene. 2011;30:4835–4842. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Takenawa T., Suetsugu S. The WASP-WAVE protein network: connecting the membrane to the cytoskeleton. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007;8:37–48. doi: 10.1038/nrm2069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rohatgi R., Ma L., Miki H., Lopez M., Kirchhausen T., Takenawa T., Kirschner M.W. The interaction between N-WASP and the Arp2/3 complex links Cdc42-dependent signals to actin assembly. Cell. 1999;97:221–231. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80732-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Misra A., Lim R.P., Wu Z., Thanabalu T. N-WASP plays a critical role in fibroblast adhesion and spreading. Biochem Biophys. Res. Commun. 2007;364:908–912. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.10.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yamaguchi H., Lorenz M., Kempiak S., Sarmiento C., Coniglio S., Symons M., Segall J., Eddy R., Miki H., Takenawa T., Condeelis J. Molecular mechanisms of invadopodium formation: the role of the N-WASP-Arp2/3 complex pathway and cofilin. J. Cell Biol. 2005;168:441–452. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200407076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yanagawa R., Furukawa Y., Tsunoda T., Kitahara O., Kameyama M., Murata K., Ishikawa O., Nakamura Y. Genome-wide screening of genes showing altered expression in liver metastases of human colorectal cancers by cDNA microarray. Neoplasia. 2001;3:395–401. doi: 10.1038/sj.neo.7900185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Victor N., Ivy A., Jiang B.H., Agani F.H. Involvement of HIF-1 in invasion of Mum2B uveal melanoma cells. Clin. Exp.Metastasis. 2006;23:87–96. doi: 10.1007/s10585-006-9024-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Diaz B., Yuen A., Iizuka S., Higashiyama S., Courtneidge S.A. Notch increases the shedding of HB-EGF by ADAM12 to potentiate invadopodia formation in hypoxia. J. Cell Biol. 2013;201:279–292. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201209151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tang Z., Araysi L.M., Fathallah-Shaykh H.M. c-Src and neural Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein (N-WASP) promote low oxygen-induced accelerated brain invasion by gliomas. PloS One. 2013;8:e75436. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0075436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ghoshal P., Teng Y., Lesoon L.A., Cowell J.K. HIF1A induces expression of the WASF3 metastasis-associated gene under hypoxic conditions. Int. J. Cancer. 2012;131:E905–E915. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material

Supplementary material