Abstract

Objective

To determine test characteristics of provider judgment for empiric antibiotic provision to patients undergoing STI testing.

Study design

We conducted a retrospective cross-sectional electronic health record review of all patients aged 13–19 years who had GC and CT testing sent from an urban, academic pediatric ED in 2012. We abstracted data including patient demographics, chief complaint, STI test results, and treatment. We calculated test characteristics comparing clinician judgment for presumptive STI treatment with the reference standard of the actual results of STI testing.

Results

Of 1223 patient visits meeting inclusion criteria, 284 (23.2%) had a positive GC and/or CT test result. Empiric treatment was provided in 615 encounters (50.3%). Provider judgment for presumptive treatment had an overall sensitivity of 67.6% (95%CI 61.8, 73.0) and a specificity of 55% (95%CI 51.7, 58.2) for accurate GC and/or CT detection.

Conclusions

Many adolescents tested for GC and CT receive empiric treatment at the initial ED visit. Provider judgment may lack sufficient sensitivity and specificity for identifying infected patients, resulting in the potential for under-treatment of true disease, overtreatment of uninfected patients, or both.

Keywords: Neisseria gonorrheae, Chlamydia trachomatis, empiric antibiotic treatment, adolescents, sexually transmitted infection, health disparities, emergency department

Chlamydia trachomatis [CT] is the most commonly reported sexually transmitted infection [STI] in the United States, and prevalence of Neisseria gonorrhoeae [NG] and CT is highest among people age 25 years and younger.1,2 Although adolescents comprise 25% of the sexually active population, they account for 50% of all STIs annually.3 Adolescent youth who seek care in hospital emergency departments [EDs] may be at even higher risk for infection as they represent a high risk and vulnerable population. In fact, studies in pediatric ED settings have demonstrated GC and/or CT infection prevalence ranging from 5% in asymptomatic patients to 20–28% in symptomatic patients.4–8

Timely and appropriate treatment of GC and CT is important to reduce the risk of complications and transmission to sexual partners. Potential complications in women include pelvic inflammatory disease, infertility, ectopic pregnancy, chronic pain, and increased risk of HIV transmission.2 In one study of patients returning for CT treatment after positive screening tests, 23% of women and 71% of men developed clinical cervicitis or urethritis in the interval between screening and treatment (median elapsed time 13 days). Two women (1.7%) developed pelvic inflammatory disease within one month of positive screening for CT and/or GC.9

Test results for GC and CT may return several days after the initial visit, and studies have shown loss-to-follow-up rates for untreated adolescents with positive GC/CT test results ranging from 31–43%.7,8 Given the high GC/CT prevalence in adolescent age groups and the lack of same-day test results, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC] recommend empiric (presumptive) treatment for GC and CT for patients under 25 years of age who have clinical cervicitis or urethritis.10 Although GC and CT tests are generally ordered from the ED to evaluate patients with symptoms or increased risk of STIs, studies have shown that not all adolescents seen in the ED receive empiric treatment when testing is sent. Two studies in pediatric EDs found rates of empiric treatment of 39% and 70% for adolescents with testing sent.7,8 Pattishall et al reported 59% sensitivity and 68% specificity of pediatric emergency medicine healthcare provider judgment for empiric treatment of GC/CT in their sample of 198 patients age 18 years and younger presenting to an urban, free-standing pediatric ED.8

We report the test characteristics of provider decision-making for presumptive treatment of GC/CT in a larger sample population seen in the pediatric ED. Furthermore, we examined the association between patient demographics and chief complaint with the likelihood of empiric treatment and positive GC/CT test results. We also determined the test characteristics of provider judgment in subgroups of patients with different presenting complaints.

Methods

We performed a retrospective, cross-sectional review of the electronic health record for all adolescent visits to the pediatric ED of an urban, academic children’s hospital from January through December 2012. We included all encounters with patients aged 13–19 years with both GC and CT testing sent from the ED. Encounters were excluded from the analysis if GC and CT were not both ordered, if either GC or CT test results were not documented, if the encounter was known to be related to a sexual assault, or if the patient was admitted to the hospital or transferred to another facility after the ED visit.

Patient demographics, chief complaint, provider information, medications administered or prescribed in the ED, and GC/CT test results were obtained from the medical record. Patient demographics included age, race, ethnicity, sex, and insurance type. We analyzed age as a continuous variable. Race/ethnicity was defined as non-Hispanic black, non-Hispanic white, Hispanic, other, or unknown. We categorized insurance as private or non-private. Non-private insurance included patients with public insurance, other governmental insurance, no insurance, or missing insurance information. We categorized chief complaints as STI-related or non-STI related. Chief complaints involving request for STI or pregnancy testing, lower abdominal/pelvic pain for females, vaginal or penile discharge, urinary symptoms, vaginal bleeding, testicular symptoms, or other genitourinary complaints were categorized as potentially STI-related. Provider type was determined by the most senior clinician and was categorized as either physician (including fellowship-trained pediatric emergency medicine physicians, general pediatricians, and other pediatric subspecialty physicians), nurse practitioner, physician assistant, or unknown/unavailable. Using the CDC Sexually Transmitted Disease [STD] Treatment guidelines, 2010,10 we defined empiric treatment as receiving any combination of ceftriaxone, cefixime, azithromycin, or doxycycline.

GC/CT test results were considered the reference standard for comparison with provider decision to provide empiric STI treatment. Our institution uses a PCR assay (Abbott RealTime PCR) for detection of GC/CT from cervical, urethral, or urine samples. This assay has a reported sensitivity and specificity of 95.2% and 99.3% for CT and 97.5% and 99.7% for GC.11, 12 In our ED, specimens that are sent for both GC and CT testing generally are obtained from urine, cervical, or urethral sites.

Data were entered into REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture), a secure, web-based application designed to support data capture for research studies.13 We used SPSS (version 22; International Business Machines Corp, Armonk, NY) and SAS (version 9.3, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) for data analysis. We performed chi-square tests and bivariable logistic regression to examine relationships between patient demographic variables and provision of empiric STI treatment. We then performed multivariable logistic regression to identify factors associated with empiric treatment for STIs. Variables with a p-value <0.2 were included in our multivariable model. We calculated test characteristics for provider judgment for empiric STI treatment by comparing provision of STI treatment with GC/CT results. We then calculated these test characteristics in subgroups of patients by chief complaints (STI-related vs. non-STI-related chief complaint). We used Pearson chi-square test for statistical comparisons between sensitivities and specificities in different chief complaint subgroups.

The hospital’s Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Results

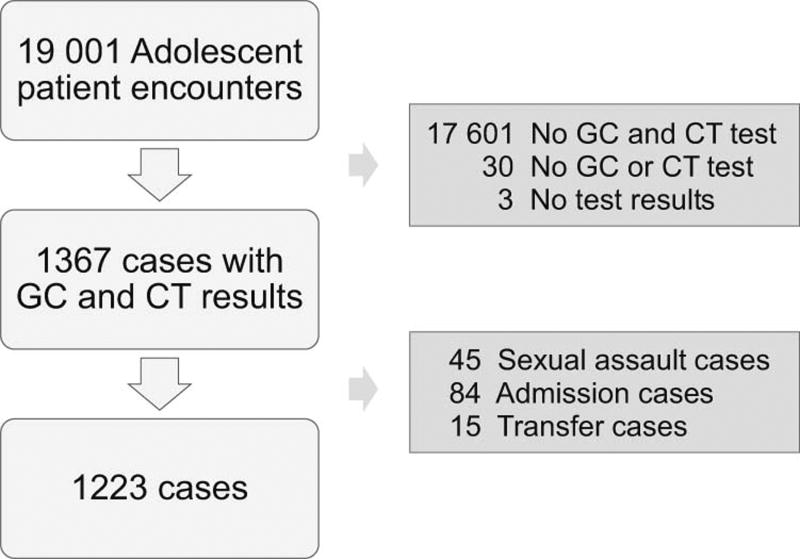

There were 1223 ED visits that met inclusion criteria and were analyzed (Figure). The majority of our study sample was female (84.1%), non-privately insured (86.6%), and of non-Hispanic black race/ethnicity (83.8%), with a median age of 17.2 years (IQR 16.0, 18.0). Most of the providers were physicians who had completed pediatric residency, with or without subspecialty fellowship training (96.1% of encounters). The provider was a nurse practitioner in 46 encounters (3.8%) and a physician assistant in 2 encounters (0.2%). There was trainee involvement in 57.4% of encounters.

Figure 1.

Study population diagram of adolescents tested for Neisseria gonorrheae and Chlamydia trachomatis

Patients Receiving Empiric Treatment

Empiric antibiotics were administered in 615 of the 1223 encounters (50.3%). In bivariable analyses (Table I), male sex, non-Hispanic race/ethnicity, older age, non-private insurance status, and encounters involving a nurse practitioner were associated with increased likelihood of empiric treatment. Patients with potential STI-related chief complaints were also more likely to receive empiric treatment compared with those with non-STI-related complaints. Trainee involvement in the visit was not associated with provision of empiric treatment. In the multivariable model, sex, race/ethnicity, insurance status, chief complaint, and provider type were all associated with empiric STI treatment (Table I).

Table 1.

Relative Odds of Empiric Treatment by Patient Demographics and Presence of Sexually Transmitted Infection (STI)-Related Chief Complaint, Bivariable and Multivariable Results

| Variable | OR (95%CI) | adjOR (95%CI) |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Sex | ||

| Male | Referent | Referent |

| Female | 0.54 (0.40, 0.74) | 0.51 (0.37, 0.70) |

|

| ||

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| Non-Hispanic Black | Referent | Referent |

| Non-Hispanic White | 1.16 (0.31, 4.34) | 1.07 (0.27, 4.26) |

| Hispanic | 0.41 (0.25, 0.66) | 0.37 (0.23, 0.61) |

| Other/Unknown | 0.93 (0.62, 1.39) | 0.95 (0.62, 1.44) |

|

| ||

| Age in years | 1.09 (1.02, 1.18) | 1.07 (0.99, 1.15) |

|

| ||

| Insurance | ||

| Private | Referent | Referent |

| Non-private | 1.80 (1.28, 2.52) | 1.98 (1.39, 2.82) |

|

| ||

| Chief Complaint | ||

| Other/Nonspecific | Referent | Referent |

| Potential STI-Related including Abdominal/Pelvic Pain | 1.90 (1.43, 2.52) | 1.93 (1.45, 2.58) |

|

| ||

| Provider Type | ||

| Physician | Referent | Referent |

| Nurse Practitioner | 1.90 (1.02, 3.53) | 2.10 (1.11, 4.00) |

Prevalence of Positive GC/CT Tests

The overall prevalence of infection with either GC and/or CT in our sample was 23.2% (18.8% CT, 7.3% GC, and 2.9% co-infection) (Table II). Prevalence was 34% for male adolescents (22.7% CT, 17.0% GC, and 5.7% co-infection) and 21.2% for female adolescents (18.1% CT, 5.4% GC, 2.3% co-infection). The prevalence of GC and/or CT infection was higher among non-Hispanic black patients (24.9%, N=1025) than in the smaller subgroups of Hispanic patients (5.9%, N=85) and non-Hispanic white patients (0%, N=9). There was no significant difference in prevalence between patients with private and non-private insurance (22.6% vs. 23.3%, OR 0.95, 95%CI 0.65, 1.42) or by age category (21.3% in 13–14 year olds, 25.0% in 15–16 year olds, and 23.2% in 17–19 year olds, p=0.56). Patients with possible STI-related chief complaints had a 23.2% prevalence of GC and/or CT infection (224 positives out of 964 cases). The prevalence of GC and/or CT infection was similar in the subset of female patients presenting with a chief complaint of abdominal or pelvic pain (22.4%) versus all patients presenting with possible STIrelated chief complaints.

Table 2.

Test Characteristics of Provider Judgment to Detect Neisseria gonorrheae (GC) and/or Chlamydia trachomatis (CT) Infection

| Positive GC/CT | Negative GC/CT | Total Patients Tested | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Empiric Treatment | 192 | 423 | 615 |

| No Empiric Treatment | 92 | 516 | 608 |

| Total Patients Tested | 284 | 939 |

Sensitivity = 67.6% (95% CI 61.8, 73.0)

Specificity = 55.0% (95% CI 51.7, 58.2)

Positive Predictive Value = 31.2% (95% CI 27.6, 35.1)

Negative Predictive Value = 84.8% (95% CI 81.7, 8.6)

Patients who tested positive for GC and/or CT had increased odds of receiving empiric treatment (OR 2.55, 95%CI 1.92, 3.37). Among those patients who tested positive for an STI, those with CT only were less likely to receive empiric antibiotics than those with either GC only or co-infection (0.54, 95%CI 0.31, 0.95).

Performance Characteristics of Provider Judgment

Table II shows the performance characteristics of provider judgment for provision of empiric STI treatment compared with STI test results. Provider judgment for empiric STI treatment had a sensitivity of 67.6% (95%CI 61.8, 73.0) and specificity of 55.0% (95%CI 51.7, 58.2). With a 23.2% prevalence of STIs, provider judgment for empiric treatment had a positive predictive value of 31.2% (95%CI 27.6, 35.0) and a negative predictive value of 84.9% (95%CI 81.8, 87.6).

Ninety-two of the 284 (32.4%) patients who ultimately tested positive for an STI did not receive empiric treatment, and 423 of the 939 (45%) patients who tested negative for an STI were treated empirically. For the remaining 708 patients (57.9% of the total sample), provider judgment regarding empiric antibiotic treatment was in agreement with the test results.

Among patients presenting with possible STI-related chief complaints, provider judgment for empiric antibiotics had a higher sensitivity (71% vs. 55%; p=0.02) but lower specificity (52% vs. 67%; p <0.01) compared with patients with non-STI related complaints. We also examined provider performance characteristics for subgroups of chief complaints (Table III).

Table 3.

Empiric Treatment Performance Characteristics by Chief Complaint

| Chief Complaint | N | Rates of Empiric Treatment for Infected Patients Sensitivity (95%CI) |

Rates of No Antibiotic Treatment for Uninfected Patients Specificity (95%CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| STI-Related Complaint | 964 | 71% (64, 77) | 52% (48, 55) |

| STI Concern | 388 | 83% (74, 90) | 37% (32, 43) |

| Urinary Symptoms | 117 | 77% (56, 91) | 58% (47, 69) |

| Vaginal Bleeding | 58 | 50% (25, 75) | 60% (43, 74) |

| Testicular Complaint | 31 | 100% (48, 100) | 85% (65, 96) |

| Abdominal/Pelvic Pain | 370 | 58% (46, 68) | 60% (54, 66) |

|

| |||

| Other symptom(s) | 259 | 55% (42, 68) | 67% (60, 74) |

|

| |||

| Any symptom(s) | 1223 | 68% (62, 73) | 55% (52, 58) |

Antibiotic Selection

Of the 615 patients who received empiric STI treatment, 558 (90.7%) were treated with antibiotic regimens that complied with the 2010 CDC STD treatment guidelines, including appropriate doses of ceftriaxone + azithromycin, ceftriaxone + doxycycline, cefixime + azithromycin, cefixime + doxycycline, or azithromycin alone at dosing for penicillin and cephalosporin-allergic patients. Another 8.9% (n=55) received treatment that was not in compliance with the 2010 CDC STD treatment recommendations, including monotherapy with azithromycin (n=20), monotherapy with ceftriaxone (n=5), inappropriate dosing with ceftriaxone 125mg (n=29) or inappropriate dosing of azithromycin (n=1). For the remaining 0.3% of empirically treated patients (n=2), ceftriaxone and azithromycin were given but dosing could not be determined.

Discussion

This retrospective, single center study found that sensitivity and specificity of provider judgment for provision of empiric treatment for GC/CT was low. Almost one-third of patients who tested positive for an STI, were not empirically treated. Furthermore, almost half of patients who tested negative for an STI were empirically treated. Lack of sensitivity results in delays in treatment and risks loss-to-follow-up without treatment, and poor specificity suggests unnecessary exposure to antibiotics. Our results are similar to the findings of Pattishall et al of low sensitivity and specificity of provider judgment to detect GC/CT in a pediatric ED. However, in our sample, sensitivity was higher and specificity was lower than Pattishall’s sample, suggesting an overall lower threshold for empiric treatment in our study population. In Pattishall’s sample, only 39% of adolescents who underwent testing received empiric treatment, and 41% of those with positive tests did not receive treatment at the initial visit.8 In part, differences in provider decision making for empiric treatment may be related to local disease prevalence, although the prevalence of GC and/or CT in their study was 28%. The prevalence of GC and/or CT infection of 23.2% in our study is consistent with previous reported prevalence among symptomatic adolescents seeking care at a pediatric ED (20–28%).6–8

Provider judgment for treatment in the subgroup of patients presenting with potentially STI-related chief complaints (including females with abdominal or pelvic pain) was 71% sensitive and 52% specific. Not surprisingly, this suggests that providers have a lower threshold for presumptive treatment when caring for patients who manifest with symptoms that may be related to an STI compared with patients presenting with non-STI-related chief complaints, where provider judgment had 55% sensitivity and 67% specificity. However, current CDC guidelines recommend empiric treatment for all patients presenting with STI-related symptoms. Therefore, our data suggest a role for provider education to increase presumptive STI treatment in patients presenting with STI-related symptoms. If all patients with STI-related symptoms had received empiric treatment, an additional 65 patients would have been treated appropriately for infection at the time of the visit and an additional 382 uninfected patients would have received antibiotics. Consequently, increased empiric treatment for symptomatic patients would have improved sensitivity while decreasing specificity. In areas of high STI prevalence, the public health benefit of earlier treatment and decreased loss-to-follow-up care may justify this tradeoff.

Provider judgment for the subset of patients with abdominal and/or pelvic pain was 58% sensitive and 60% specific, suggesting a similar threshold for empiric antibiotics as that seen for patients with nonspecific chief complaints. Although the differential diagnosis of abdominal pain may be broader than the differential diagnosis in patients with specific STI concerns or gynecologic complaints, it is still important to consider STI for this subgroup of patients, as illustrated by the fact that testing was sent for these patients. It is difficult to know whether the rate of empiric treatment in this subset was influenced by additional clinical details or by provider perceptions of risk. Nurse practitioner encounters were more likely to involve empiric treatment than physician encounters, suggesting possible differences in training, but the generalizability of this finding is limited by the relatively small number of nurse practitioners in our sample.

Our analysis found that patient sex, age, race/ethnicity, insurance status, and chief complaint were all associated with the provider’s decision to administer empiric antibiotics. The prevalence of GC and/or CT infection was lower in the non-Hispanic white and Hispanic subgroups, but the odds of empiric treatment were higher for non-Hispanic white patients and lower for Hispanic patients compared with non-Hispanic black patients. Our ability to evaluate racial/ethnic differences was limited as most of the patients with testing ordered were non-Hispanic black or Hispanic race/ethnicity. Goyal et. al. examined symptomatic adolescent patients in a pediatric ED and found that patients of black or African-American race were more likely to have STI testing sent, and thus patients of other racial/ethnic groups may be underrepresented in our sample.14 Prior studies have shown a higher prevalence of GC/CT in patients of non-Hispanic black race/ethnicity, although it is not clear if this data reflects differences in exposure or more limited access to healthcare for screening and treatment.1–2,5 Given the high prevalence of GC/CT in adolescents and the barriers to follow up, providers should strongly consider treatment for patients who have clinical indications for testing, regardless of race/ethnicity.

Although older patients and patients with non-private insurance in our sample were more likely to receive empiric antibiotics, there was no significant difference in GC/CT prevalence by age or insurance status, suggesting providers’ threshold to treat younger and privately insured patients empirically may be too high and providers may be missing infections due to bias or assumptions about patient follow up. Inadequate empiric treatment in certain demographic subgroups results in delays in treatment and risks loss-to-follow-up, and will result in maintaining the relatively high infection prevalence observed in our sample and our local community. The ED frequently serves as a “safety-net” provider for patients who lack access to primary care. The ED may also provide an alternative for adolescents followed by pediatricians who do not provide routine gynecologic care in the office, and for adolescents who are uncomfortable discussing sexual health and behaviors with their primary provider.

Although male patients made up only 15.7% of the encounters in which GC/CT testing was performed, they were more likely to receive empiric treatment and more likely to have positive test results. Providers may be less likely to order STI testing for male adolescents, and male patients who undergo testing may be more likely to have clinical evidence of urethritis, prompting empiric treatment. The prevalence of GC/CT among males in our sample was lower than reported elsewhere in the literature. Timm et. al. found that 64% of males age 15–21 years seeking care at a pediatric ED with concern for STI or a genitourinary complaint were positive for GC or CT.15

In our sample, almost one-third of adolescents with GC/CT were discharged without antibiotics and almost half of those with negative tests received presumptive antibiotics. Possible strategies to minimize both loss-to-follow up and delays in treatment, as well as overuse of antibiotics, include improving follow-up mechanisms, developing clinical decision rules for the use of empiric antibiotics, and point-of-care testing for GC/CT in the pediatric ED.7–8,16–18

Our study has some limitations. The study encompassed one year of patient visits to a single pediatric ED, and may not be generalizable to all practice settings, groups of providers, and patient populations. Data for this study were obtained retrospectively and rely on the integrity of the medical record. We do not have information on provider intent, so it is possible that some patients receiving antibiotic combinations inconsistent with the CDC STI guidelines were not being treated for an STI-related infection. It is also possible that the treating provider may have had access to information that is not apparent to us, such as recent treatment for STI, known exposures, or patient refusal to take empiric antibiotics. Furthermore, although we did have access to the chief complaint documented in triage, we did not have specific information on STI symptoms for each patient.

Provider judgment to administer empiric treatment for CT and GC infections lack sensitivity and specificity. Future steps should better define indications for empiric treatment in high-risk populations and seek to develop accurate point-of-care testing for these infections.

Acknowledgments

Supported by an NICHD (HD070910 [to M.G.]).

We would like to thank Shilpa Patel MD MPH and James Chamberlain MD for their contributions to data analysis.

Abbreviations

- CT

Chlamydia trachomatis

- ED

Emergency Department

- GC

Neisseria gonorrhoeae

- STI

Sexually transmitted infection

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Torrone E, Papp J, Weinstock H Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Prevalence of Chlamydia trachomatis genital infection among persons aged 14–39 years--United States, 2007–2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63:834–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control. [Accessed May 21, 2015];2013 Sexually Transmitted Diseases Surveillance, National Profile. Last updated Dec 16, 2014, at http://www.cdc.gov/std/stats13/gonorrhea.htm.

- 3.Weinstock H, Berman S, Cates W., Jr Sexually transmitted diseases among American youth: incidence and prevalence estimates, 2000. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2004;36:6–10. doi: 10.1363/psrh.36.6.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miller MK, Dowd MD, Harrison CJ, Mollen CJ, Selvarangan R, Humiston SG. Prevalence of 3 sexually transmitted infections in a pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2015;31:107–12. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000000284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Uppal A, Chou KJ. Screening adolescents for sexually transmitted infections in the pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2015;31:20–4. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000000322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goyal M, Hayes K, Mollen C. Sexually transmitted infection prevalence in symptomatic adolescent emergency department patients. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2012;28:1277–80. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e3182767d7c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huppert JS, Reed JL, Munafo JK, Ekstrand R, Gillespie G, Holland C, Britto MT. Improving notification of sexually transmitted infections: a quality improvement project and planned experiment. Pediatrics. 2012;130:e415–22. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-3326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pattishall AE, Rahman SY, Jain S, Simon HK. Empiric treatment of sexually transmitted infections in a pediatric Emergency Department: are we making the right decisions? Am J Emerg Med. 2012;30:1588–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2011.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Geisler WM, Wang C, Morrison SG, Black CM, Bandea CI, Hook E. The natural history of untreated Chlamydia trachomatis infection in the interval between screening and returning for treatment. Sex Transm Dis. 2008;35:119–23. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318151497d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Workowski KA, Berman S Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59:1–110. Erratum in: MMWR Recomm Rep. 2011 Jan 14;60:18. Dosage error in article text. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/std/treatment/2010/default.htm. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abbott RealTime CT/NG PCR Assay. Abbott Park, IL: 2015. Abbott Laboratories. Package Insert available at http://www.abbottmolecular.com/static/cms_workspace/pdfs/US/CTNG_8L07-91_US_FINAL.pdf on August 20, 2015. Retrieved from http://www.abbottmolecular.com/us/products/infectious-diseases/realtime-pcr/c-trachomatis-n-gonorrhoeae-ct-ng-assay.html on August 20, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marshall R, Chernesky M, Jang D, Hook EW, Cartwright CP, Howell-Adams B, Ho S, Welk J, Lai-Zhang J, Brashear J, Diedrich B, Otis K, Webb E, Robinson J, Yu H. Characteristics of the m2000 automated sample preparation and multiplex real-time PCR system for detection of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45:747–51. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01956-06. Epub 2007 Jan 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap) - a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goyal MK, Hayes KL, Mollen CJ. Racial disparities in testing for sexually transmitted infections in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2012;19:604–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2012.01338.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Timm N, Bouvay K, Scheid B, Defoor WR., Jr Evaluation and management of sexually transmitted infections in adolescent males presenting to a pediatric emergency department: is the chief complaint diagnostic? Pediatr Emerg Care. 2011;27:1042–4. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e318235e950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reed JL, Mahabee-Gittens EM, Huppert JS. A decision rule to identify adolescent females with cervical infections. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2007;16:272–80. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.M077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Greer L, Wendel GD., Jr Rapid diagnostic methods in sexually transmitted infections. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2008;22:601–17. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2008.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huppert JS, Taylor RG, St Cyr S, Hesse EA, Reed JL. Point-of-care testing improves accuracy of STI care in an emergency department. Sex Transm Infect. 2013;89:489–94. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2012-050994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]