Abstract

Objectives

Extracellular microRNAs represent functional biomarkers for obesity and related disorders; we investigated plasma microRNAs in insulin resistance phenotypes in obesity.

Methods

175 microRNA were analysed in females with (insulin sensitivity n=11; insulin resistance n=19; Type-II diabetes n=15) and without (n=12) obesity. Correlations between microRNA level and clinical parameters, and levels of 15 microRNA in a murine obesity model were investigated.

Results

106 microRNA were significantly (adjusted P≤0.05) different between controls and at least one obesity phenotype, including microRNAs with: previously reported roles in obesity and altered circulating levels (e.g. miR-122, miR-192); known roles in obesity but no reported changes in circulating level (e.g. miR-378a); no current reported role in, or association, with obesity (e.g. miR-28-5p, miR-374b, miR-32). miRNA in the latter group were found to be associated with extracellular vesicles. 48 microRNA showed significant correlations with clinical parameters; stepwise regression retained let-7b, miR-144-5p, miR-34a, and miR-532-5p in a model predictive of insulin resistance (R2 = 0.57, P=7.5 × 10-8). miR-378a and miR-122 were perturbed in metabolically relevant tissues in a murine model of obesity.

Conclusions

This study expands on the role of extracellular miRNA in insulin resistant phenotypes of obesity and identifies candidate miRNA not previously associated with obesity.

Keywords: insulin resistance, obesity, gene expression

Introduction

The pandemic levels of obesity represent a major public health challenge. Obesity is a systemic disorder and risk factor for multiple diseases including Type-II diabetes (T2D), hypertension, and cardiovascular disease. Insulin resistance (IR) is strongly associated with obesity and T2D; however, not all individuals with obesity develop insulin resistance and T2D.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small, non-coding RNAs (19-23 nucleotides) that inhibit translation and/or direct mRNA degradation (1). They are involved in the pathogenesis of complex diseases including obesity (2) and T2D (3). MiRNAs are present in blood where they are packaged in extracellular vesicles (EVs) (4), associated with lipoprotein (LDL/HDL) (5), or bound by RNA-binding protein Argonaute-2 (6) to prevent their degradation. As such, their potential as disease biomarkers is increasingly interrogate. In vitro miRNAs transported in association with exosomes or HDL can be delivered to recipient cells in their active form and modulate target mRNAs (4, 5), altering cell function and key cell signalling processes. Therefore, while there is still much to understand about the functional role of circulating miRNAs in vivo, they represent a novel cell-cell communication network, mediating cross-talk between organs.

Following the first report of circulating miRNAs associated with T2D in 2010 (7), studies have reported associations between circulating miRNA levels and obesity in adults (8, 9), young adults (10) and children (11), and with related metabolic disorders including metabolic syndrome (12, 13), prediabetes (14, 15), and T2D (9, 15, 16). Obesity is strongly associated with IR and while a number of these studies have investigated potential correlations between IR and miRNA levels, none to our knowledge have specifically interrogated insulin sensitivity (IS) phenotypes in obesity. Here we investigate circulating plasma miRNAs in individuals with three obesity phenotypes, IS, IR, and T2D, and examine potential tissues of origin for miRNAs of interest in a mouse model of obesity.

Methods

Sample Inclusion

Subjects gave written informed consent and the study complied with the Helsinki Declaration. The Central Regional Ethics Committee, Wellington, NZ approved the study of individuals with obesity (WGT/00/04/030). Samples from individuals without obesity were recruited from within the Institute of Environmental Research under Institutional ethics (ESR). All individuals self-reported as European.

Samples from individuals with obesity were obtained from patients undergoing gastric bypass. Individuals were fasted overnight, blood collected prior to gastric bypass in EDTA tubes, centrifuged at 1300 g for 10 min, and plasma removed and stored at - 80°C. Study participants were females with severe obesity grouped into three categories: individuals with T2D, and those without T2D were classified as IS or IR. Insulin sensitivity was assessed using two indices, HOMA-IR (homeostasis model assessment) using the HOMA2 Calculator (v2.2.3) from © Diabetes Trials Unit, University of Oxford (https://www.dtu.ox.ac.uk/homacalculator) and McAuley Index (McA) (17) calculated as EXP(3.29-(0.25 × ln(insulin mU/l))-(0.22 × ln(BMI))-(0.28 × ln(triglycerides mmol/l)). Individuals without diabetes were classified as IS if they had a HOMA-IR ≤1.0, McA > 6.3, and IR if they had a HOMA-IR ≥ 1.0 and McA <6.3. Individuals with T2D were either diagnosed at time of gastric bypass (n=6, fasting glucose mmol/L ≥ 7 and/or HbA1c ≥ 6.5 % DCCT) or previously diagnosed and taking oral hypogylcemics (n=8) or diet controlled (n=1). Clinical and anthropometric data are presented in Table 1. Fasted plasma samples were also obtained from 12 non-diabetic (self-reported) age (44 ±9) and sex (female) matched controls with BMI 22.9 ± 2.6 kg/m2. Age did not differ significantly between individuals with and without obesity. Additional clinical information was not available for controls.

Table 1. Clinical and anthropometric data for the obese study cohort.

| Insulin Sensitive (S) (n=11) | Insulin Resistant (R) (n=19) | Type-2 diabetic (T2D)(n=15) | S vs R+ | S vs T2D+ | R vs T2D+ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 41 (± 5) | 40 (± 6) | 45 (±8) | NS | NS | NS |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 42.6 (±4.0) | 44.7 (±3.9) | 44.2 (± 4.2) | NS | NS | NS |

| Fasting glucose (mmol/L) | 4.6 (± 0.3) | 4.7 (± 0.4) | 9.3 (±4.4) | NS | 0.002 | 7.5 × 10-5 |

| Fasting insulin (pmol/L) | 41.9 (± 9.2) | 105.9 (± 35.6) | 142.0 (±67.7) | 6.4×10-5 | 6.2 × 10-5 | NS |

| HOMA2 IR | 0.8 (± 0.2) | 1.9 (±0.6) | 3.4 (± 3.0) | 4.8 × 10-5 | 0.009 | NS |

| McAuley Index | 7.8 (±1.0) | 5.4 (±0.6) | 4.7 (± 1.0) | 6.8 × 10-9 | 4.9 × 10-8 | 0.04 |

| HbA1c (DCCT %) | 5.4 (± 0.3) | 5.4 (± 0.3) | 7.5 (± 1.7) | NS | 0.0007 | 1.0 × 10-5 |

| Total Cholesterol (mmol/L) | 5.14 (± 1.05) | 5.11 (± 0.80) | 5.02 (± 1.0) | NS | NS | NS |

| Triglycerides (mmol/L) | 0.94 (±0.29) | 1.57 (±0.63) | 2.29 (± 1.35) | 0.0004 | 0.003 | 0.04 |

| LDL (mmol/L) | 3.06 (± 1.0) | 3.08 (±0.65) | 3.11 (± 1.26) | NS | NS | NS |

| HDL (mmol/L) | 1.64 (± 0.31) | 1.33 (±0.18) | 1.21 (± 0.22) | 0.002 | 0.0004 | NS |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 132.4 (±9.9) | 134.2 (±13.9) | 143.9 (± 13.0) | NS | 0.02 | 0.04 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 70.4 (± 10.1) | 76.0 (± 10.4) | 74.6 (± 7.9) | NS | NS | NS |

Figures are presented as mean ± standard deviation. T.Test P values are presented for the comparisons between clinical groups, NS indicates not significant, a threshold of P ≤ 0.05 was considered significant. For the healthy females (n=12) mean age was 44 (±9) which was not significantly different from any of the three phenotypic groups above. Mean BMI was 22.9 ± 2.6, which was significantly different from the insulin sensitive (P=3.4 × 10-12), insulin resistant (P=7.8 × 10-17) and T2D (P=3.9 × 10-14) phenotypes.

Animal model

Experiments were conducted in accordance with the BIDMC animal ethics committee and IACUC regulations. Male C567BL/6 mice (Jackson Laboratories) were fed normal chow (n=5) or a 45% high fat high sucrose diet (HFHS, n=5) from 11 weeks of age for a total of 20 weeks. Mice were housed in a barrier facility for the entirety of the experiment and allowed free access to food and water. At time of sacrifice, mice fed normal chow had a mean body weight of 33.6 ± 2.8 g (± SD), while HFHS diet fed mice were 53.1 ± 2.5 g. Animals were euthanized by ketamine/xylazine overdose and blood and organs were collected immediately. Total blood was collected in EDTA micro-centrifuge tubes and centrifuged at 1,000 × g for 15 min to separate plasma. Plasma was centrifuged at 2,000 × g for 15 min. Heart, liver, subcutaneous adipose, pericardial adipose, and visceral adipose were harvested, washed in PBS, and snap frozen on dry ice.

RNA extraction and analysis, and statistical analyses

Results

Circulating miRNA in human plasma

We compared the levels of 170 detectable miRNAs in plasma between three groups with obesity (IS, IR and T2D) and controls (Figure S1). Eighteen miRNA showed a significant difference (adjusted P≤0.05) in levels in all groups with obesity compared to controls (14 down-regulated, 4 up-regulated). These included miRNA with: previously reported roles in obesity and altered circulating levels associated with disease (e.g. miR-144, miR-151-5p); roles in obesity but no reports of changes in plasma abundance (e.g miR-365, miR-23b, miR-26a), and no current reported role in, or association with, obesity (miR-28-5p, miR-374b, miR-32), Table 2.

Table 2. Summary of the literature for the 18 miRNA showing significantly different plasma levels in all obese groups compared to lean controls.

| Changes in circulating levels in human studies of obesity and T2D | Tissue expression and relevant functional roles in animal and cell models | |

|---|---|---|

| miR-23a | Decreased serum levels in T2D and pre-diabetic patients (15); increased in whole blood of patients with metabolic syndrome and hypercholesterolemia (12) | NA |

| miR-23b | NA | Decreased in diet-induced obese mice, up-regulated with low-fat feeding (31); increased exosome-bound miR-23b released from adipocytes cultured from obese vs lean subjects visceral fat (S1) |

| miR-26a | NA | Promotes brown fat adipogenesis through targeting ADAM17 (S2); Decreased in diet-induced obese mice, up-regulated with low-fat feeding (31); decreased liver expression in overweight vs lean subjects, overexpression in high fat diet fed mice improves insulin sensitivity (S3) |

| miR-28-5p | NA | NA |

| miR-30e-3p | NA | Down-regulated in white adipose tissue of mice fed HFD (S4) |

| miR-151-5p | Decreased serum levels in obese vs non-obese young adults (10) | Decreased expression in WAT of obese vs lean subjects (S5) |

| miR-151-3p | Decreased serum levels in obese vs non-obese young adults (10) | NA |

| miR-181a | Increased in the serum of male T2D patients (S6); decreased in monocytes of obese patients, weight loss normalized expression levels (S7) | Targets IDH1 and decreases expression of lipid synthesis genes, transgenic mice have lower body weight (S8); targets SIRT1 (S6) |

| miR-197 | Increased in whole blood of patients with metabolic syndrome and hypercholesterolemia (12); decreased in patients with T2D (7); expression levels inversely correlated with risk of glycemic progression in Asian Indians (S9) | |

| miR-374b | NA | NA |

| miR-584 | Increased in whole blood of patients with metabolic syndrome and hypercholesterolemia (12) | NA |

| let7d | NA. Let-7 in general but none specific to let-7d | NA |

| let7e | NA Let-7 in general but none specific to let-7e | NA |

| let7f | Decreased in patients with T2D, increases with diabetic treatment (S10) | Decreased in diet-induced obese mice, up-regulated with low-fat feeding (31) |

| miR-32 | NA | NA |

| miR-101 | Increased in serum of T2D vs normal glucose tolerance patients | |

| miR-144 | Upregulated in whole blood of T2D vs impaired fasting glucose patients (S11); higher plasma expression associated with T2D in Swedes but not Iraqis (16) | Targets IRS1 (S11); liver levels increased in morbidly obese patients with non-alcohol steatohepatitis, targets ABCA1 (S12) |

| miR-365 | NA | Regulates brown fat adipogenesis (S13, S14) |

References S1-S14 can be found in Supplementary References

Significant differences (P≤0.05) were observed for IS vs IR (miR-335 and miR-423-5p), IS vs T2D (let-7b) and IR vs T2D (miR-19b, miR-22, miR-22-5p, miR-136, miR-152, miR-484). Table 3 presents the top 5 miRNAs with greatest positive and negative fold-change difference between controls and each subgroup with obesity.

Table 3. Top 5 miRNA in each patient group showing greatest positive and negative fold change difference to controls.

| miRNA | Log2 Fold Change (Control) | KS test statistic1 | Adjusted P value2 | Changes in circulating levels in human studies of obesity and T2D | Tissue expression and relevant functional roles in animal and cell models | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Insulin Sensitive | miR_144 | 5.1 | 1 | 0.0003 | Up regulated in whole blood of T2D vs impaired fasting glucose patients (S11); higher plasma expression associated with T2D in Swedes but not Iraqis (16) | Targets IRS1 (S11); Liver levels increased in morbidly obese patients with non-alcohol steatohepatitis, targets ABCA1 (S12) |

| miR_365 | 4.0 | 1 | 0.0037 | NA | Regulates brown fat adipogenesis (S13, S14) | |

| miR_32 | 3.4 | 1 | 0.0002 | NA | NA | |

| miR_451 | 3.1 | 0.83 | 0.0476 | Serum levels down-regulated following Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery in low BMI patients (S15); serum levels increased in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (25) | Increased in the heart of high fat diet-induced diabetic mice, knock-out reduces cardiac lipotoxicity, targets CAB39 (S16) | |

| miR_150 | 2.1 | 1 | 0.0003 | Obese knock out mice have exacerbated insulin resistance (S17); up-regulated in pancreatic islet cells of diabetic mice (S18) | ||

| let_7f | -3.8 | 0.91 | 0.0058 | Decreased in patients with T2D, increases with diabetic treatment (S10) | Decreased in diet-induced obese mice, up-regulated with low-fat feeding (31) | |

| let_7e | -3.6 | 1 | 0.0005 | NA Let-7 in general but none specific to let-7e | Decreased in diet-induced obese mice, up-regulated with low-fat feeding (31) | |

| miR_409_3p | -3.5 | 0.83 | 0.0476 | NA | NA | |

| miR_151_5p | -3.0 | 0.91 | 0.0058 | NA | NA | |

| miR_374b | -2.8 | 0.91 | 0.0058 | NA | NA | |

| Insulin Resistant | miR_144 | 5.3 | 1 | 0.0002 | As above | As above |

| miR_193b | 3.8 | 1 | 0.0005 | Increased in pre-diabetes but not T2D, levels are normalized with chronic exercise (14) | Targets CREB5, NRIP1, and NFYA, stimulates adiponectin secretion in adipocytes and white adipose tissue (S19); indirectly regulates CCL2 production in white adipose tissue(5); regulates brown fat adipogenesis(14) | |

| miR_365 | 3.8 | 1 | 0.0001 | NA | As above | |

| miR_451 | 3.2 | 1 | 2.4 ×10-6 | As above | As above | |

| miR_122 | 3.1 | 0.92 | 7.5 ×10-5 | Highly associated with obesity and insulin resistance (8,10,11); reduced after weight loss (11); associated with hepatic steatosis (25) | Decreased expression following bariatric surgery in rats with shifts in metabolic profile, targets CS, GLUT1, G6PD, FASN, PRKAB1, and ALDOA (S20) | |

| miR_409_3p | -4.0 | 0.92 | 0.0002 | NA | NA | |

| let_7f | -4.0 | 1.00 | 2.4 × 10-6 | As above | As above | |

| let_7e | -3.9 | 1.00 | 2.0 × 10-5 | As above | NA | |

| miR_1974 | -3.7 | 1.00 | 2.4 × 10-6 | NA | NA | |

| miR_382 | -3.7 | 0.83 | 0.0020 | NA | NA | |

| Typeype-2 Diabetic | miR_193b | 5.1 | 0.93 | 0.0063 | As above | As above |

| miR_144 | 4.1 | 1 | 0.0006 | As above | As above | |

| miR_136 | 3.8 | 0.83 | 0.0349 | NA | NA | |

| miR_34a | 3.5 | 0.85 | 0.0049 | Increased circulating levels in T2D patients, significant with meta-analysis across controlled studies (24) | Suppresses FGF1 and SIRT1 and inhibits brown fat formation in obese mice (S21); targets NAMPT and SIRT1 in liver (S22); disrupts beta KL/FGF19 signalling in liver (S23) | |

| miR_32 | 3.4 | 1 | 2.0 × 10-5 | NA | NA | |

| let_7d | -3.7 | 0.92 | 0.0005 | Let-7 in general but none specific to let-7d. | NA | |

| let_7c | -3.6 | 0.83 | 0.0197 | Let-7 in general but none specific to let-7c. | Decreased in diet-induced obese mice, up-regulated with low-fat feeding (31) | |

| let_7e | -3.4 | 1 | 2.0 × 10-5 | As above | As above | |

| let_7f | -3.2 | 1 | 2.0 × 10-5 | As above | As above | |

| miR_485_3p | -2.8 | 0.93 | 0.0003 | NA | NA |

Kolmogorov-Smirnov test statistic

Bonferroni adjusted P value. References S10-S23 can be found in Supplementary References.

We interrogated potential associations between plasma miRNA (ΔCt) and 11 clinical parameters using Pearson correlation. Forty-eight miRNA showed a significant correlation (adjusted P≤0.05, absolute r≥0.3) with at least one clinical parameter (Table S1). No significant correlations were observed with fasting cholesterol, and only one significant miRNA:trait correlation was observed for diastolic blood pressure (miR-145) and fasting LDL (miR-17). Table 4 presents the miRNA:trait correlations with absolute r≥0.4.

Table 4. Correlations between plasma miRNA level and Clinical traits passing absolute r≥0.4 and adjusted P ≤0.05.

| Clinical Trait | Direction of Fold Change vs Controls+ | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| miRNA | Glucose | HbA1c | Insulin | McAuley Index | HOMA-IR | Triglycerides | HDL | Systolic BP | insS | insR | T2D |

| let-7b | -0.44 (0.006) | ↓ | ↓ | ||||||||

| let-7c | 0.4 (0.013) | ↓ | ↓ | ||||||||

| let-7d | 0.47 (0.003) | -0.43 (0.008) | 0.41 (0.012) | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | |||||

| miR-21 | -0.43 (0.007) | ↓ | ↓ | ||||||||

| miR-22 | -0.41 (0.011) | -0.42 (0.009) | -0.43 (0.007) | ||||||||

| miR-22-5p | -0.42 (0.010) | ||||||||||

| miR-25 | -0.45 (0.005) | ||||||||||

| miR-30a | -0.41 (0.013) | ||||||||||

| miR-34a | -0.44 (0.006) | 0.49 (0.002) | -0.43 (0.008) | -0.49 (0.002) | ↑ | ↑ | |||||

| miR-99a | -0.45 (0.005) | ||||||||||

| miR-122 | -0.46 (0.004) | 0.56 (2 × 10-4) | -0.41 (0.013)) | -0.41 (0.012) | ↑ | ↑ | |||||

| miR-155 | 0.41 (0.012) | ↓ | ↓ | ||||||||

| miR-192 | -0.42 (0.011) | ↑ | |||||||||

| miR-193b | -0.46 (0.004) | ↑ | ↑ | ||||||||

| miR-194 | -0.41 (0.011) | ↑ | |||||||||

| miR-210 | -0.42 (0.010) | -0.43 (0.009) | 0.48 (0.003) | -0.41 (0.012) | |||||||

| miR-215 | -0.44 (0.007) | ↑ | ↑ | ||||||||

| miR-378 | -0.54 (4×10-4) | 0.42 (0.009) | -0.52 (8 × 10-4) | -0.47 (0.003) | 0.49 (0.002) | ↑ | |||||

| miR-505 | -0.50 (0.001) | ||||||||||

| miR-532-5p | -0.44 (0.007) | ↑ | |||||||||

| miR-660 | -0.45 (0.005) | ||||||||||

Correlation analyses were performed on normalised miRNA Ct levels (ΔCt), a higher Ct indicates a lower miRNA level.

Where a significant (adjusted P ≤ 0.05) difference was detected between the miRNA levels in the control and obese groups the direction of fold change is indicated. All blood measures were assayed on fasted samples.

We further explored which miRNA(s) were the best predictors of trait by performing step-wise regression analyses of all miRNA significantly associated with a given trait (Table 5). Notably, we observed four miRNA (let-7b, miR-144-5p, miR-34a and miR- 532-5p) retained in a model strongly predictive of insulin resistance, R2=0.57, P=7.5 × 10-8. To investigate the potential contribution of clinical and anthropometric variables (Table 1) to these models (Table 5) we performed additional step-wise regression analyses by including these variables and the miRNA from the respective final model (Table 5); miRNAs were retained in the final model for all clinical traits except fasting glucose, HbA1c and HDL (as expected the strong correlation between HbA1c and fasting glucose, R2=0.86, P=2.2 × 10-16 dominated the respective models). For insulin resistance (McA) three of the four miRNA (let-7b, miR-144-5p, miR-34a) were retained and fasting lipids (total cholesterol, HDL LDL) were included in the final model (R2=0.70, P=8.6 × 10-10).

Table 5. Results from step-wise linear regression of miRNAs against trait.

| Trait | miRNA Final Model | Final Model including Clinical Variables | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| miRNAs loaded in final model | Adjusted R2 | R2 P value | Variables loaded in final model | Adjusted R2 | R2 P Value | |

| McAuley Index | let-7b, miR-144-5p, miR-34a, miR532-5p | 0.57 | 7.5 × 10-8 | let-7b, miR-144-5p, miR-34a, total cholesterol*, HDL*, LDL* | 0.70 | 8.6 × 10-10 |

| HOMA-IR | let-7g, miR-378 | 0.27 | 5.3 × 10-4 | miR-378, HbA1c, HDL*, LDL* | 0.47 | 5.9 × 10-6 |

| Fasting Insulin | let-7d, let7g, miR-122, miR-15b, miR-193b, miR-210, miR-335, miR-34a, miR-374a, miR-374b, miR-378, miR-421 | 0.50 | 2.1 × 10-4 | let-7d, miR-193b, miR-335, miR-34a, miR-374a, glucose*, HbA1c, diastolic blood pressure, HDL* | 0.53 | 2.1 × 10-5 |

| Fasting Glucose | Let-7g, miR-22 | 0.27 | 5.1 × 10-4 | Age, insulin*, HbA1c, LDL* | 0.88 | 2.2 × 10-16 |

| HbA1c | miR-136, miR-155, miR-505 | 0.37 | 5.4 × 10-5 | Glucose*, insulin*, HOMA-IR, systolic blood pressure, HDL*, LDL* | 0.91 | 2.2 × 10-16 |

| Fasting Triglycerides | miR-125b, miR-193b, miR-215, miR-22, miR-27b, miR-34a, miR-502-3p, miR-532-5p | 0.47 | 7.8 ×10-5 | miR-125b, miR-193b, miR-215, miR-27b, miR-34a, BMI, insulin*, HOMA-IR, HbA1c, diastolic blood pressure, LDL* | 0.64 | 1.1 × 10-6 |

| Fasting HDL | miR-22, miR-378 | 0.26 | 7.7 × 10-4 | Glucose*, insulin*, HOMA-IR, McA, HbA1c, total cholesterol*, LDL* | 0.57 | 1.5 × 10-6 |

| Systolic BP | miR-155, miR-193b | 0.24 | 0.0014 | miR-155, miR-193b, BMI, glucose, HOMA-IR, diastolic blood pressure, total cholesterol* | 0.40 | 3.4 × 10-4 |

Indicates fasting blood measures

To determine extracellular compartmentalisation, we investigated miRNA found in our study but not previously implicated in obesity (Table 2), in plasma EVs isolated from six females with obesity. Additionally, we measured the expression of two miRNA previously associated with non-EV fractions as controls (miR-146a (18) and miR-92 (19)). All but one of the miRNA of interest tested (miR-23b) were undetectable (mean Ct ≥ 35) in the non-EV fraction but detectable in the EV fraction: miR-374b (Ct 21.6 ±1.5), let-7d (Ct 22.1 ± 1.1), let-7f (Ct 22.1 ±1.3), miR-32 (Ct 27.4 ± 0.9), miR-26a (Ct 21.1 ± 1.2), miR-30e (Ct 25.0 ±1.3), and miR-365 (Ct 30.6 ± 0.8). miR-23b was detected in both the EV (Ct 18.9 ± 1.1) and flow (Ct 28.5 ±4.4) fractions, similar to that observed for control miRNA (miR-146a: EV = Ct 21.0 ±1, flow = Ct 25.7 ±4.1 and miR-92a: EV = Ct 23.2 ± 0.8, flow = Ct 29.8 ± 4.6). Thus, the majority of these miRNA are EV-associated and miR-23b may also be associated with either Ago-2 proteins or lipoprotein complexes.

Analysis of candidate miRNA in mouse model of obesity

Fifteen miRNA were selected for further analysis based on i) no previous report of a role in obesity or T2D (let-7d, let-7e, miR-32, miR-28-5p), ii) potential role in obesity, but no previous report of changing circulating levels (miR-365), or iii) reported role in obesity and a correlation with at least one clinical parameter in the current study (miR-19a, miR-34a, miR-122, miR-155, miR-192, miR-193b, miR-378a, miR-451, miR-484); let-7f was also included because of the reported association with T2D and because many studies to date have not differentiated between let-7 family members (see Tables 2 and 3). We compared miRNA levels in mice on normal chow versus a HFHS diet for 20 weeks (body weight of HFHS mice increased by 27.2g ± 2.1, compared to controls 7.4g ±2.2).

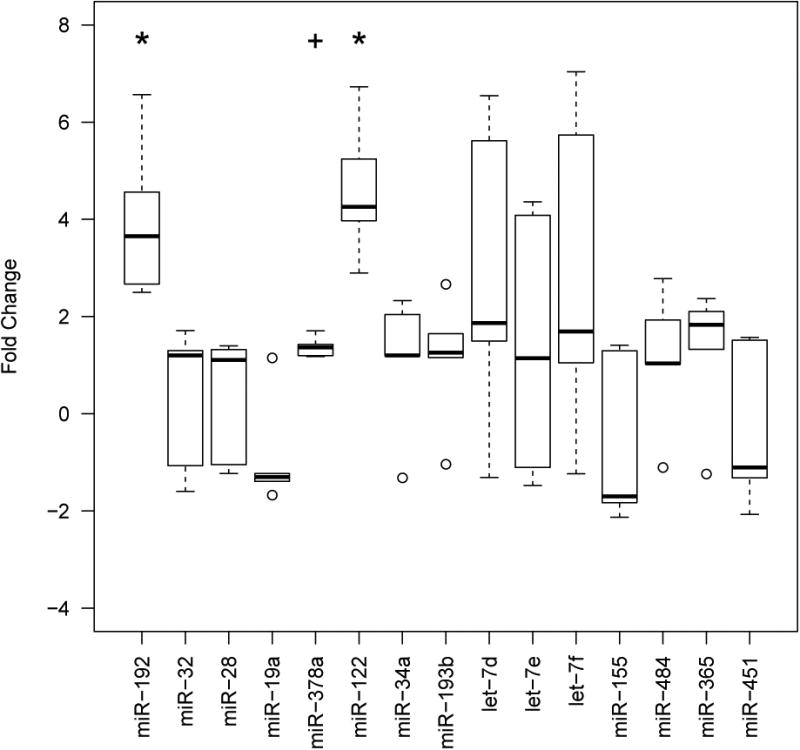

We observed significantly different levels of plasma miRNA between control and HFHS mice for miR-122, and miR-192 (P= 0.008). Performing an additional a priori analysis informed by the direction of change in the human study also revealed a significant difference in the level of miR-378a (P=0.04) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Levels of 15 plasma miRNA in a mouse model of obesity, fold change relative to controls.

Fold change was calculated using the formula 2-ΔΔCt. * indicates significance at P<≤0.05 (two-tailed) and + at P≤ 0.05 (one-tailed).

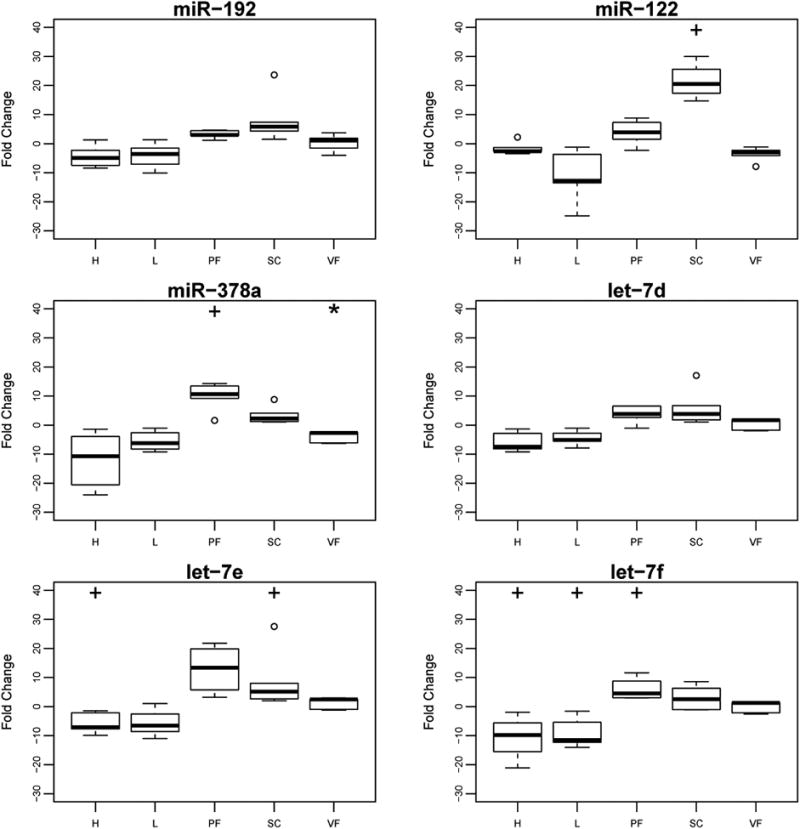

To evaluate potential tissue origins or targets of these miRNAs we investigated the levels of miRNA-122, miRNA-192, miR-378a, let-7d, let-7e, and let-7f in metabolically relevant tissues (subcutaneous adipose, visceral adipose, pericardial adipose, liver, and the left ventricle of the heart, Figure 2). We observed a significant decrease in miR-378a in visceral adipose of HFHS mice compared to control (P=0.008). Given the small sample size, and in order to reveal additional differences which might warrant future investigation, we also applied a less stringent (one tailed) statistical analysis and observed significant increases (P=0.04) in miRNA levels in the HFHS mice compared to the normal chow group for miR-378a and let-7f in pericardial fat, and miR-122 and let-7e in subcutaneous fat, and significant decreases for let-7e and let-7f in heart, and let-7f in liver.

Figure 2.

Tissue miRNA expression levels in a mouse model of obesity, fold change relative to controls.

Levels of miR-192, miR-122, miR-378a, let-7d, let-7e and let-7f in heart (H), liver (L), pericardial adipose (PF), subcutaneous adipose (SC) and visceral adipose (VF). * indicates significance at P<≤0.05 (two-tailed) and + at P≤ 0.05 (one-tailed). Fold change was calculated using the formula 2-ΔΔCt

Discussion

This study investigated plasma miRNA profiles (Exiqon targeted panel) in 45 individuals with obesity (IS =11, IR=19, T2D=15) compared to controls (BMI 22.9 ± 2.6 kg/m2). Eighteen miRNA showed differential abundance in all obese phenotypes (Table 2). While a number of these miRNA had been associated with obesity and/or T2D, three (miR-28-5p, miR-374b, miR-32) had not. Significant differential plasma abundance was also observed for three miRNA in a murine obesity model, with differential expression of two of these seen in metabolically relevant tissues. Strong associations were observed between circulating miRNA levels and clinical traits (Table 4, Table S1). Step-wise regression analyses revealed four miRNA contributing significantly to a model predictive of IR (R2=0.57, P=7.5 × 10-8, Table 5); association of circulating levels of these miRNA with IR in humans has not previously been reported. Further step-wise regression analyses investigating the additional of clinical variables identified a model with increased predictive strength (R2= 0.70, P=8.6 × 10-10, Table 5) which retained three of the four miRNA and included fasting lipids. This study provides additional evidence for a plasma miRNA signature in obesity, and for signatures that may differentiate metabolic sub-phenotypes of IS and IR in obesity; it highlights specific avenues for future research, both in terms of potential circulating miRNA biomarkers, and identification of miRNA with previously unrecognised roles in obesity.

Alterations in circulating miRNAs in association with obesity (8, 11, 20) and related metabolic disorders (7, 12, 13, 14) have been reported. Of the eighteen circulating miRNAs showing significant alterations in all individuals with obesity compared to those without (Table 2), dysregulation of eleven has previously been reported in obesity, T2D, or metabolic syndrome in humans, while seven have no previous reports of associations between circulating levels in humans and these disorders (miR-23b, miR-26a, miR-28-5p, miR-30-3p, miR-374b, miR-365, miR-32). Altered levels of miR-26a, miR-23b and miR-30e-3p have been shown in murine obesity models, and changes in miR-26a and miR-23b have been observed in human tissues. To our knowledge, miR-28-5p, miR-374b, and miR-32 have not been implicated in previous obesity-related studies, including perturbed levels in human patients (circulating or tissue) or mechanistic studies in animal or cell models.

Not all individuals with obesity develop IR or T2D and it is not fully understood why some are relatively metabolically “healthy” or at least resistant to metabolic complications such as IR. Step-wise regression analyses of the miRNA whose plasma level showed strong associations (absolute r≥0.3, adjusted P≤0.05, Table S1) with IR identified four miRNA contributing significantly to a model predictive of IR (R2=0.57, P=7.5 × 10-8, Table 5). To our knowledge these four miRNA (let-7b, miR-144-5p, miR-34a, miR-532-5p) have not been directly linked with IR in humans. When clinical variables were added three/four miRNA (let-7b, miR-144-5p, miR-34a) were retained in a final model which included (R2=0.70, P=8.6 × 10-10, Table 5). Of these miRNA all but miR-144-5p have been implicated in obesity and/or T2D. A recent analysis of miRNA-seq data revealed a decrease in miR-144-5p in blood in Alzheimer's Disease (21), a disorder in which IR is implicated, consistent with our observations of a negative correlation between plasma miR-144 level and IR. We observed an increase in plasma miR-34a in individuals with obesity and T2D compared to individuals without, and a positive correlation between plasma miR-34a level and IR; this is consistent with previous reports of increased circulating levels of miR-34a in T2D (22, 23, 24). Perturbed circulating levels of miR-34a have also observed in obesity (22), and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (25) along with reported roles for miR-34a in pancreatic beta-cell function (26), and hepatic lipid metabolism (27). Animal studies suggest a role for let-7b in diabetic renal dysfunction (28, 29, 30) and decreased circulating levels are seen in mouse obesity models (31), consistent with our observation of a negative correlation between circulating let-7b and IR.

We observed strong correlations (absolute r≥0.4, adjusted P≤0.05) between circulating levels of miR-122, let-7d, miR-210, and miR-378 and IR (Table 4). Plasma miR-122 level positively correlated with IR, consistent with a study in males which reported that serum miR-122 levels correlated positively with HOMA (r=0.401) (10). While circulating levels of miR-210, miR-378 and let-7d have not been associated with IR to date, studies suggest a potential role. Increased miR-210 is associated with pancreatic beta cell apoptosis in diabetic mouse models (32), and we observed a positive correlation between plasma miR-210 and IR. For let-7d we observed a negative correlation between plasma level and IR; let-7d expression is increased in skeletal muscle in T2D and modulates IL-13 secretion (33), raising the possibility that let-7d may be retained by muscle rather than secreted in to the circulation in IR states, or alternatively that let-7d is delivered to/taken up by skeletal muscle from he circulation in the IR state – options that warrant further investigation. miR-378a modulates PPARGC-1β, and is encoded within an intron of the gene (34). It is upregulated by leptin, IL-6 and TNF-α in human adipocyte cell culture (35) and after exercise in human skeletal muscle (36) with animal studies implicating it in brown adipose tissue thermogenesis (37), hepatic insulin signalling(38) and obesity and adipogenesis (39). We observed a positive correlation between plasma miR-378a level and IR.

While the association of circulating miRNA levels with clinical factors may hint at a functional role, it does not indicate causality but highlights these miRNA for further analyses. This is pertinent because miRNA bound to lipoproteins or EVs can transfer between cell types and functionally effect downstream processes. We investigated the presence of eight miRNA whose circulating levels had not previously been associated with obesity in EVs; all were present at significant levels, adding weight to their candidacy for further investigation.

We observed similar changes in three circulating miRNAs in our human study and murine model of obesity, including miR-122 and miR-192, for which associations with obesity and related disorders in humans and animal models are reported (8, 10, 11). Additionally, we saw increased abundance of plasma miR-378a in HFHS mice; as described above, this miRNA has a number of potential roles in obesity and IR, but changes in circulating levels in humans have not previously been reported. This replication of our observations suggests that miR-122, miR-192, and miR-378a may be conserved biomarkers for obesity or metabolic state. In addition, we observed differential expression of these miRNAs across metabolically relevant tissues including visceral, subcutaneous, and pericardial fat (all implicated in obesity physiology), Figure 2. Specifically, miR-378a was significantly decreased in visceral adipose tissue, but increased in pericardial adipose, demonstrating that miRNA expression patterns are not only tissue specific (e.g. liver and heart), but different across fat deposits. Changes in tissue miRNA levels may reflect changes in transcription rate, degradation of the miRNA, uptake from the circulation or surrounding cells, or release of the miRNA from the cell or tissue. Further studies are required to investigate the mechanisms behind the expression changes we have observed and any functional role these miRNA may have.

Potential limitations of this study include the small sample size. However a stringent adjusted P value was used for our analyses, and our observation of both significant changes in a number of circulating miRNAs consistent with previous reports in the literature, and three miRNA in a mouse model of obesity provide additional confidence in the results. Future studies with larger patient numbers are needed to validate these findings and confirm both the biomarker status for the miRNAs reported here, and any potential functional role in disease biology. While the differences in observed miRNA levels can arise through issues with sanmple age and/or quality, our robust QC analysis and our observation that eleven of eighteen circulating miRNAs showing significant alterations in all individuals with obesity compared to those without (Table 2), have previously been reported in obesity, T2D, or metabolic syndrome in humans provide confidence in our results. Our analysis was performed on miRNA interrogated by an Exiqon serum/plasma focus panel (V1), therefore additional miRNA associated with IR may have been missed by this targeted approach. Our study also focused on females, and while the mouse study investigated circulating miRNA in male mice, and we observed an increase in miR- 122, miR-192 and miR-378a in both the human female cohort and male mice, further studies are needed to explore the miRNA reported here in larger cohorts including both sexes. Finally, while the spin column EV-RNA isolation method employed here is relatively specific for isolation of EV-RNA over non-EV RNA (19), small amounts of non-EV RNA may also be captured by the filter, raising the possibility that some of the obesity-associated miRNAs may also be bound to proteins or lipoproteins.

Conclusion

We have identified miRNA whose circulating levels are significantly perturbed in obesity. Roles for a number of these have previously been reported in obesity and related disorders, highlighting the possibility that other miRNA identified by this study may also have functional roles in obesity. Levels of three miRNA in plasma of a mouse model were consistent with the human data. Forty-eight miRNA were significantly associated with a clinical trait, and four miRNA were retained in a model strongly predictive (R2=0.57) of insulin resistance after step-wise regression. When fasting lipids were added to this model, three of the four miRNA were retained and the strength increased (R2=0.70). These data provide additional evidence for the role of miRNA in obesity and related disorders, and highlight specific avenues for future research.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary File Figure S1: Boxplots showing log2 expression (exprs) levels of circulating miRNA in plasma of control individuals without obesity, and individuals with three different obesity phenotypes - insulin sensitive, insulin resistance and type-two diabetes.

Supplementary File Table S1: Pearson's correlation data for all miRNA: clinical trait associations passing absolute r ≥ 0.3 and adjusted P ≤ 0.05.

What is already known about this subject?

Differences in circulating miRNAs have been reported in individuals with and without obesity

Correlations between levels of circulating miRNAs and measures of insulin resistance have been observed.

What does your study add?

We specifically investigate circulating miRNA in females with different insulin resistance phenotypes of obesity

We identify circulating miRNA which have not previously been associated with obesity

Four miRNA whose circulating levels have not been previously associated with the insulin resistance were retained in a model predictive of this trait.

Acknowledgments

Funding: NZ based research was supported by The Institute of Environmental Science and Research core and pioneer funding. Experiments conducted at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Centre and Massachusetts General Hospital were funded by NIH grants UH3 TR000901 and RO1 HL122547. RVS was funded by The Thrasher Research Fund and The American Heart Association.

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors have nothing to disclose and declare no conflict of interest

References S1-S23 cited in Tables 2 and 3 can be found in Supplementary References.

References

- 1.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell. 2009;136:215–233. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heneghan HM, Miller N, Kerin MJ. Role of microRNAs in obesity and the metabolic syndrome. Obes Rev. 2010;11:354–361. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2009.00659.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fernandez-Valverde SL, Taft RJ, Mattick JS. MicroRNAs in beta-cell biology, insulin resistance, diabetes and its complications. Diabetes. 2011;60:1825–1831. doi: 10.2337/db11-0171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Valadi H, Ekstrom K, Bossios A, Sjostrand M, Lee JJ, Lotvall JO. Exosome-mediated transfer of mRNAs and microRNAs is a novel mechanism of genetic exchange between cells. Nature Cell Biology. 2007;9:654–U672. doi: 10.1038/ncb1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vickers KC, Palmisano BT, Shoucri BM, Shamburek RD, Remaley AT. MicroRNAs are transported in plasma and delivered to recipient cells by high-density lipoproteins. Nature Cell Biology. 2011;13:423–U182. doi: 10.1038/ncb2210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arroyo JD, Chevillet JR, Kroh EM, Ruf IK, Pritchard CC, Gibson DF, et al. Argonaute2 complexes carry a population of circulating microRNAs independent of vesicles in human plasma. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108:5003–5008. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019055108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zampetaki A, Kiechl S, Drozdov I, Willeit P, Mayr U, Prokopi M, et al. Plasma microRNA profiling reveals loss of endothelial miR-126 and other microRNAs in type 2 diabetes. Circulation research. 2010;107:810–817. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.226357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ortega FJ, Mercader JM, Catalan V, Moreno-Navarrete JM, Pueyo N, Sabater M, et al. Targeting the Circulating MicroRNA Signature of Obesity. Clinical Chemistry. 2013;59:781–792. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2012.195776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pescador N, Perez-Barba M, Ibarra JM, Corbaton A, Martinez-Larrad MT, Serrano-Rios M. Serum circulating microRNA profiling for identification of potential type 2 diabetes and obesity biomarkers. PLoS One. 2013;8:e77251. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang R, Hong J, Cao Y, Shi J, Gu W, Ning G, et al. Elevated circulating microRNA-122 is associated with obesity and insulin resistance in young adults. European journal of endocrinology / European Federation of Endocrine Societies. 2015;172:291–300. doi: 10.1530/EJE-14-0867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Prats-Puig A, Ortega FJ, Mercader JM, Moreno-Navarrete JM, Moreno M, Bonet N, et al. Changes in Circulating MicroRNAs Are Associated With Childhood Obesity. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2013;98:E1655–E1660. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Karolina DS, Tavintharan S, Armugam A, Sepramaniam S, Pek SL, Wong MT, et al. Circulating miRNA profiles in patients with metabolic syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:E2271–2276. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Raitoharju E, Seppala I, Oksala N, Lyytikainen LP, Raitakari O, Viikari J, et al. Blood microRNA profile associates with the levels of serum lipids and metabolites associated with glucose metabolism and insulin resistance and pinpoints pathways underlying metabolic syndrome: the cardiovascular risk in Young Finns Study. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2014;391:41–49. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2014.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parrizas M, Brugnara L, Esteban Y, Gonzalez-Franquesa A, Canivell S, Murillo S, et al. Circulating miR-192 and miR-193b are markers of prediabetes and are modulated by an exercise intervention. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100:E407–415. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-2574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang ZP, Chen HM, Si HQ, Li X, Ding XF, Sheng Q, et al. Serum miR-23a, a potential biomarker for diagnosis of pre-diabetes and type 2 diabetes. Acta diabetologica. 2014;51:823–831. doi: 10.1007/s00592-014-0617-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang X, Sundquist J, Zoller B, Memon AA, Palmer K, Sundquist K, et al. Determination of 14 circulating microRNAs in Swedes and Iraqis with and without diabetes mellitus type 2. PLoS One. 2014;9:e86792. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0086792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McAuley KA, Williams SM, Mann JI, Walker RJ, Lewis-Barned NJ, Temple LA, et al. Diagnosing insulin resistance in the general population. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:460–464. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.3.460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wagner J, Riwanto M, Besler C, Knau A, Fichtlscherer S, Roxe T, et al. Characterization of Levels and Cellular Transfer of Circulating Lipoprotein-Bound MicroRNAs. Arteriosclerosis Thrombosis and Vascular Biology. 2013;33:1392–+. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.300741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Enderle D, Spiel A, Coticchia CM, Berghoff E, Mueller R, Schlumpberger M, et al. Characterization of RNA from Exosomes and Other Extracellular Vesicles Isolated by a Novel Spin Column-Based Method. Plos One. 2015;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0136133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wen D, Qiao P, Wang L. Circulating microRNA-223 as a potential biomarker for obesity. Obesity research & clinical practice. 2015;9:398–404. doi: 10.1016/j.orcp.2015.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Satoh J, Kino Y, Niida S. MicroRNA-Seq Data Analysis Pipeline to Identify Blood Biomarkers for Alzheimer's Disease from Public Data. Biomark Insights. 2015;10:21–31. doi: 10.4137/BMI.S25132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nunez Lopez YO, Garufi G, Seyhan AA. Altered levels of circulating cytokines and microRNAs in lean and obese individuals with prediabetes and type 2 diabetes. Molecular Biosystems. 2016;13:106–121. doi: 10.1039/c6mb00596a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Seyhan AA, Lopez YON, Xie H, Yi FC, Mathews C, Pasarica M, et al. Pancreas-enriched miRNAs are altered in the circulation of subjects with diabetes: a pilot crosssectional study. Scientific reports. 2016;6 doi: 10.1038/srep31479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhu HM, Leung S. Identification of microRNA biomarkers in type 2 diabetes: a metaanalysis of controlled profiling studies. Diabetologia. 2015;58:900–911. doi: 10.1007/s00125-015-3510-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yamada H, Suzuki K, Ichino N, Ando Y, Sawada A, Osakabe K, et al. Associations between circulating microRNAs (miR-21, miR-34a, miR-122 and miR-451) and nonalcoholic fatty liver. Clinica Chimica Acta. 2013;424:99–103. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2013.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaviani M, Azarpira N, Karimi MH, Al-Abdullah I. The role of microRNAs in islet betacell development. Cell biology international. 2016;40:1248–1255. doi: 10.1002/cbin.10691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rottiers V, Naar AM. MicroRNAs in metabolism and metabolic disorders. Nat Rev Mol Cell Bio. 2012;13:239–250. doi: 10.1038/nrm3313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Park JT, Kato M, Lanting L, Castro N, Nam BY, Wang M, et al. Repression of let-7 by transforming growth factor-beta(1)-induced Lin28 upregulates collagen expression in glomerular mesangial cells under diabetic conditions. Am J Physiol-Renal. 2014;307:F1390–F1403. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00458.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schaeffer V, Hansen KM, Morris DR, LeBoeuf RC, Abrass CK. RNA-binding protein IGF2BP2/IMP2 is required for laminin-beta 2 mRNA translation and is modulated by glucose concentration. Am J Physiol-Renal. 2012;303:F75–F82. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00185.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang B, Jha JC, Hagiwara S, McClelland AD, Jandeleit-Dahm K, Thomas MC, et al. Transforming growth factor-beta 1-mediated renal fibrosis is dependent on the regulation of transforming growth factor receptor 1 expression by let-7b. Kidney Int. 2014;85:352–361. doi: 10.1038/ki.2013.372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hsieh CH, Rau CS, Wu SC, Yang JCS, Wu YC, Lu TH, et al. Weight-reduction through a low-fat diet causes differential expression of circulating microRNAs in obese C57BL/6 mice. BMC genomics. 2015:16. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-1896-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nesca V, Guay C, Jacovetti C, Menoud V, Peyot ML, Laybutt DR, et al. Identification of particular groups of microRNAs that positively or negatively impact on beta cell function in obese models of type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2013;56:2203–2212. doi: 10.1007/s00125-013-2993-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jiang LQ, Franck N, Egan B, Sjogren RJO, Katayama M, Duque-Guimaraes D, et al. Autocrine role of interleukin-13 on skeletal muscle glucose metabolism in type 2 diabetic patients involves microRNA let-7. Am J Physiol-Endoc M. 2013;305:E1359–E1366. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00236.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carrer M, Liu N, Grueter CE, Williams AH, Frisard MI, Hulver MW, et al. Control of mitochondrial metabolism and systemic energy homeostasis by microRNAs 378 and 378(star) Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109:15330–15335. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1207605109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xu LL, Shi CM, Xu GF, Chen L, Zhu LL, Zhu L, et al. TNF-alpha, IL-6, and Leptin Increase the Expression of miR-378, an Adipogenesis-Related microRNA in Human Adipocytes. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2014;70:771–776. doi: 10.1007/s12013-014-9980-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McLean CS, Mielke C, Cordova JM, Langlais PR, Bowen B, Miranda D, et al. Gene and MicroRNA Expression Responses to Exercise; Relationship with Insulin Sensitivity. Plos One. 2015;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0127089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim J, Okla M, Erickson A, Carr T, Natarajan SK, Chung S. Eicosapentaenoic Acid Potentiates Brown Thermogenesis through FFAR4-dependent Up-regulation of miR- 30b and miR-378. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2016;291:20551–20562. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.721480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu W, Cao HC, Ye C, Chang CJ, Lu MH, Jing YY, et al. Hepatic miR-378 targets p110 alpha and controls glucose and lipid homeostasis by modulating hepatic insulin signalling. Nature Communications. 2014;5 doi: 10.1038/ncomms6684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Huang NN, Wang J, Xie WD, Lyu Q, Wu JB, He J, et al. MiR-378a-3p enhances adipogenesis by targeting mitogen-activated protein kinase 1. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2015;457:37–42. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.12.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary File Figure S1: Boxplots showing log2 expression (exprs) levels of circulating miRNA in plasma of control individuals without obesity, and individuals with three different obesity phenotypes - insulin sensitive, insulin resistance and type-two diabetes.

Supplementary File Table S1: Pearson's correlation data for all miRNA: clinical trait associations passing absolute r ≥ 0.3 and adjusted P ≤ 0.05.