Abstract

Intervertebral disc degeneration (DD) is a cause of low back pain (LBP) in some individuals. However, while >30% of adults have DD, LBP only develops in a subset of individuals. To gain insight into the mechanisms underlying non-painful versus painful DD, human cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) was examined using differential expression shotgun proteomic techniques comparing healthy controls, subjects with non-painful DD, and patients with painful DD scheduled for spinal fusion surgery. Eighty-eight proteins were detected, 27 of which were differentially expressed. Proteins associated with DD tended to be related to inflammation (e.g. cystatin C) regardless of pain status. In contrast, most differentially expressed proteins in DD-associated chronic LBP patients were linked to nerve injury (e.g. hemopexin). Cystatin C and hemopexin were selected for further examination by ELISA in a larger cohort. While Cystatin C correlated with DD severity but not pain or disability, hemopexin correlated with pain intensity, physical disability and DD severity. This study demonstrates that CSF can be used to study mechanisms underlying painful DD in humans, and suggests that while painful DD is associated with nerve injury, inflammation itself is not sufficient to develop LBP.

Keywords: proteomics, intervertebral disc degeneration, low back pain, cystatin C, hemopexin

Introduction

Chronic low back pain (LBP) is a highly prevalent, costly, and disabling condition which is undertreated.55 In some individuals, LBP arises from the intervertebral discs, which may undergo degeneration, resulting in alterations in volume, shape, structure and composition.12 However, the link between intervertebral disc degeneration (DD) and chronic LBP is unclear, as 30% of adults without LBP have signs of DD,7, 51 associated with normal aging.71 Because of this, magnetic resonance imaging studies are unable to differentiate painful from non-painful degenerating discs.48 Furthermore, while radiating pain is often associated with LBP, nerve compression is not commonly observed by magnetic resonance imaging techniques.36 Other factors not detectable by imaging must therefore contribute to the pathophysiological mechanisms of painful vs. non-painful intervertebral DD. A greater understanding of these factors will identify mechanisms that should be targeted for pain relief.

Biochemical indices of intervertebral DD can be observed in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), as the spinal canal where CSF is obtained is in close proximity to the intervertebral discs. For instance, previous studies have observed altered protein expression in the CSF of patients with lumbar disc herniation.10, 11, 62, 105 Our goal was to examine CSF for differences between individuals with painful and non-painful DD by quantitative shotgun proteomics. Shotgun proteomics has the advantage of providing an unbiased account of protein expression, allowing for the identification of proteins that would not have been predicted a priori to be involved in the disease pathology.

In CSF there is a large dynamic range between the most abundant (e.g. albumin; 130–350 mg/L) and the least abundant detectable proteins (ng/L).82 Since highly abundant and large proteins produce many peptide fragments which can mask the signal of potentially more interesting, low abundance proteins, we employed two methods of sample enrichment prior to proteomic analysis: immunodepletion and acetonitrile precipitation. Isobaric tags for relative and absolute quantification (iTRAQ) were then used in an exploratory cohort to compare relative protein abundances in the CSF of: i) normal controls, ii) subjects with non-painful moderate to severe DD, iii) patients with DD-associated chronic LBP that were scheduled for spinal fusion surgery.

The inclusion of the pain-free DD group allowed us to distinguish between processes involved in painful vs. non-painful disc-degeneration, permitting the identification of pain-specific changes in protein expression. After the initial proteomic screen, two candidate proteins were selected for quantification by ELISA in a larger cohort. Based on the patterns of differential protein expression observed in the proteomics screen, we hypothesized that Cystatin C, a marker for inflammation, would be associated with disc degeneration but not with pain or disability. In contrast, we hypothesized that hemopexin, a protein previously linked to nerve injury, would be correlated with pain, disability and disc degeneration.

Methods

Overview of Experimental Design

In painful intervertebral DD, changes in CSF levels of proteins may be a reflection of the DD itself or of alterations related to the pathophysiological mechanisms driving pain. In order to distinguish between these two possibilities, a group of subjects with asymptomatic, pain-free DD was recruited to act as an internal control, allowing us to differentiate between biochemical indices of asymptomatic versus symptomatic DD. The inclusion of a pain-free group with DD as an internal control to differentiate between biochemical indices of asymptomatic and symptomatic DD is a key feature of this study.

Healthy subjects without DD, pain-free subjects with moderate to severe DD, and patients with chronic LBP linked to intervertebral DD (selected to undergo spinal fusion surgery to treat LBP) were recruited for the study between March 2006 and August 2008. Lumbar MRIs were obtained and CSF was collected and pooled for exploratory proteomic analysis.

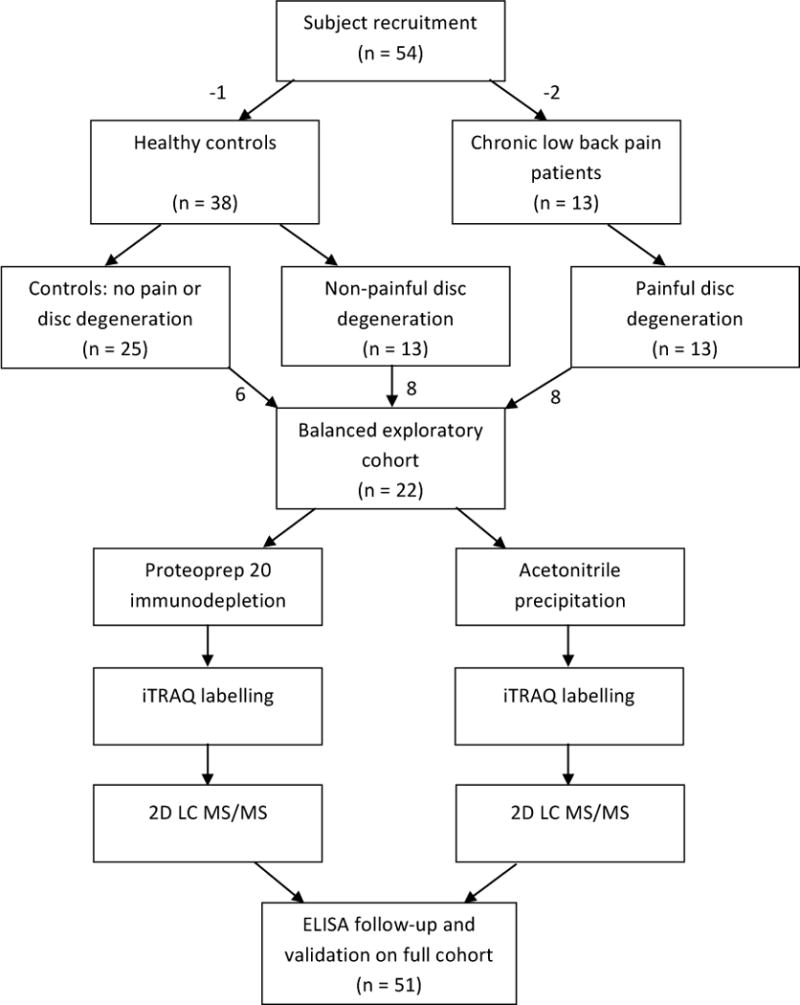

CSF was analyzed by mass spectrometry using two different sample preparation protocols for removal of abundant proteins. Removal of abundant proteins is important because of the large dynamic range present in CSF, which extends at least 10 orders of magnitude.103 Currently, isotopic labeling techniques are limited in that they can only determine changes in relative abundance over a dynamic range of 2 to 3 orders of magnitude.86 Samples were digested with trypsin and labelled with iTRAQ for analysis by 2D liquid chromatography (LC) tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS). A flow chart describing the experimental protocol of the exploratory proteomics experiment is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Overview of experimental design. Healthy subjects and LBP patients were recruited. Lumbar MRIs were taken, pain and disability assessments were recorded, and CSF was collected. Healthy subjects were segregated into a control group without DD, or a group with pain-free DD. For the initial proteomic study, an exploratory cohort was created to balance age and sex differences. This was performed in order to reduce variation and to maximize the likelihood that changes in protein levels were due to the presence of DD and/or pain. CSF was pooled and subsequently fractionated by two different sample preparation techniques. In one analysis pathway, CSF was immunodepleted using a Proteoprep 20 spin column. In the other analysis pathway, acetronitrile was used to precipitate and remove large molecular weight proteins. Samples were then subjected to iTRAQ labelling for quantitative analysis. Two differentially expressed proteins were then selected for further analysis by ELISA in the full cohort.

Based on the results of the initial proteomic screen, two proteins (Cystatin C and Hemopexin) were selected for further analysis by ELISA. Finally, the relationship between these two proteins and pain intensity, physical disability and DD severity were examined.

All procedures were approved by the institutional review boards of the University of Minnesota (Protocol #0407M62061), Allina Health Hospitals & Clinics (Protocol #1885) and McGill University (Protocol #A02-M29-07B). Informed consent was obtained from each subject. CSF collection, MRIscoring, and all biochemistry were performed by individuals blind to experimental group.

Study Participants

Three groups of participants were included in this study: i) pain-free subjects without DD, ii) pain-free asymptomatic subjects with DD, and iii) patients with chronic LBP with DD. Questionnaires, physical examinations and CSF collection were performed at the University of Minnesota General Clinical Research Center. Lumbar MRIs were collected at the Fairview University Medical Center or the Twin Cities Spine Center. Descriptive statistics for the three groups are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

A. Characteristics of the full subject and patient pool (used in the ELISA analysis)

| N | M:F | Age | Maximum disc degeneration score (/5) | Total disc degeneration score (/25) | ODI % disability | VAS | Total MPQ score | Total protein concentration (μg/ml) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| Control (no pain or disc degeneration) | 25 | 13:12 | 32 ± 2 | 2.7 ± 0.1 | 12.0 ± 0.6 | 0 ± 0 | 0.8 ± 0.6 | 0 ± 0 | 238 ± 14 |

| Non-painful disc degeneration | 13 | 10:3 | 48 ± 3*** | 4.2 ± 0.1*** | 17.8 ± 0.8*** | 1 ± 0.5*** | 3 ± 2 | 0.5 ± 0.3 | 311 ± 24*** |

| Painful disc degeneration | 13 | 6:7 | 42 ± 3* | 4.0 ± 0.3*** | 16.4 ± 0.8** | 45 ± 2*** ### | 54 ± 6*** ### | 17 ± 2*** ### | 301 ± 30 |

| B. Characteristics of the exploratory cohort (used in the proteomic analysis) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | M:F | Age | Maximum disc degeneration score (/5) | Total disc degeneration score (/25) | ODI % disability | VAS | Total MPQ score | Total protein concentration (μg/ml) | |

|

| |||||||||

| Control (no pain or disc degeneration) | 6 | 3:3 | 41 ± 2 | 2.8 ± 0.2 | 13.3 ± 1.1 | 0.3 ± 0.3 | 1.8 ± 1.5 | 0 ± 0 | 283 ± 27 |

| Non-painful disc degeneration | 8 | 6:2 | 46 ± 4 | 4.1 ± 0.2*** | 17.3 ± 1.0* | 0.5 ± 0.5 | 0.4 ± 0.4 | 0.1 ± 0.1 | 320 ± 30 |

| Painful disc degeneration | 8 | 5:3 | 41 ± 3 | 4.4 ± 0.3*** | 17.4 ± 0.6* | 47 ± 3*** ### | 66 ± 7*** ### | 18 ± 3 *** ### | 290 ± 29 |

All values listed as mean ± SEM.

ODI: Oswestry low back disability index version 2.0

VAS: Visual analogue scale

MPQ: McGill Pain Questionnaire

Compared to control

= p < 0.05,

= p < 0.01,

= p < 0.001

Compared to non-painful disc degeneration

= p < 0.001

General exclusion criteria for all subjects included complicating medical factors such as previous spine surgery, pregnancy, lactation, meningitis, hepatitis, scoliosis, osteoporosis, neuropathies, and neurological conditions (e.g. psychosis, dementia, Parkinson’s, etc.). Subjects were asked to refrain from strenuous exercise 3 days before the pain assessment and CSF collection.

Pain-free healthy male and non-pregnant female volunteers ages 21–65 were recruited by advertisement. Individuals were considered for inclusion if they had no history of chronic pain of any type and no LBP over the last three months. Volunteers were excluded if they were using prescribed steroids or narcotics for chronic medical conditions, if they refused to discontinue anti-inflammatory and analgesic medications for 72 hours prior to physical exam and CSF collection, or if they were using antidepressants and had not been on a steady dose for at least 2 months. Lumbar MRIs were scored by an observer blind to participant status to determine if DD was present. Subjects with lumbar discs scoring ≤ 3 on the 5-point Thompson scale108 were placed in the control (no pain or DD) group. Those with at least one lumbar disc scoring 4 or 5 on the Thompson scale were placed in non-painful DD group. The 5-point (1–5) Thomson scale was developed with cadaveric samples and grades gross morphological changes, taking into account the shape of the NP, AF, endplate and vertebral body. Lumbar discs scoring 4 or 5 have clefts in the nucleus, focal disruptions in the annulus, irregularity and sclerosis of the endplate, and osteophytes at vertebral body margins.

For inclusion in the symptomatic painful DD group, patients aged 21–65 years with chronic LBP associated with diagnosed DD were recruited at the Twin Cities Spine Centre. Only patients with a minimum of 6 months of severe pain, scoring 4 or 5 for at least one disc on the Thompson scale, and selected for disc removal and spinal fusion, were recruited. MRI imaging was used by the clinical staff to determine the subject’s suitability for surgery. These MRIs were then re-evaluated by a blind observer together with the MRIs from the pain-free volunteers as described above. Patients were excluded unless they belonged to one of the following three medication regiments: non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) and opioid, NSAID and steroid, opioid and steroid. Analgesic use was not withheld. The potential contribution of other structures (e.g. facet joints, ligaments, muscles) to chronic LBP in this population was not evaluated.

All subjects were assessed for perceived pain intensity using a visual analogue scale (VAS) out of 100. Pain-free subjects were included in the study if they reported scores of ≤ 10, and LBP subjects were included if they reported scores ≥ 25. Subjects also completed the short form of the McGill pain questionnaire (MPQ).73, 74 The Oswestry low back disability index (ODI) version 2.034 was used to evaluate how chronic LBP affected subjects’ perceived ability to perform daily activities.

Lumbar MRI scores were missing from three subjects in the control group and four subjects in the painful DD group. Only the available data was analyzed, and missing values were not replaced with replacement values, uncertain values, or modeled data.

Sample Collection and Storage

CSF was collected with a 25 gauge Whitacre spinal needle under i.v. sedation with midazolam. The needle was introduced to the spinal canal at L3/4 according to standard practice using surface landmarks and CSF was collected by passive drip until either a) the 20 ml cutoff was reached or b) the CSF stopped flowing freely. At the time of collection, the quality of the tap and the visual appearance of the CSF were recorded (clear, cloudy, yellow or bloody). No traumatic taps were recorded and all but 4 samples were clear. One of the 4 was excluded due to high protein content, the remaining 3 became clear after the initial tap and produced protein concentration and expression values in range with their respective experimental groups (2 pain-free with no DD and 1 pain-free with DD). Collected CSF was chilled, centrifuged at 250 g for 10 minutes to remove any cellular or other contamination, the supernatant flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C.

Safety

A maximum of 20 mL of CSF was collected to reduce variability from rostro-caudal concentration gradients and to minimize the risk of post-dural headache. Following CSF collection, each subject was monitored closely for 1–2 hours for any post-dural puncture complications. During this interval, the patients received i.v. fluids at a rate of 200 ml/hr to help minimize the development of post-dural headache. Once the patient was stable and feeling well, standard post-procedure instructions were given to the subjects, and they were released to a friend or family member who escorted them home and stayed with them overnight. Only one case of a possible post-dural headache was reported. However, this individual did not follow post-procedure instructions and consumed excess amounts of alcohol the evening following CSF collection, and may have been experiencing hangover symptoms. The individual declined follow-up treatment.

Creation of the Exploratory Cohort

For the initial proteomics screen, a subset of samples was selected to create an exploratory cohort balanced for sex and age to maximize the chances that observed differences in protein expression were due to disease state rather than variations within the subject pool. This was necessary because of the age differences between groups. The experimental design, in which pain-free individuals were recruited and then separated into ‘with’ or ‘without DD’ groups based on MRI, did not allow for age matching as the grouping was performed post hoc based on DD, which increases with age.

Samples were pooled for proteomic analysis into 1) subjects without DD or LBP, 2) subjects with DD but without LBP, 3) subjects with both DD and LBP. Pooling began with the thawing of equal volumes of CSF from each subject and mixing all the samples from each group together into a single vessel. The vessel was then vortexed briefly to ensure homogenous mixing. Prior to pooling total protein content of the CSF from each individual was determined using the Bradford protein assay (Pierce Biotechnology).

Gel Electrophoresis

Gel electrophoresis was performed with 8–16% polyacrylamide precast Ready Gels (BioRad). Gels were stained with silver nitrate and developed with sodium carbonate for visualization. Polyacrylamide gels were then digitized with a gel reader.

ProteoPrep Immunodepletion of Abundant Proteins

CSF immunodepletion was performed with a ProteoPrep 20 plasma immunodepletion column (Sigma-Aldrich) in 100 μl increments. Two cycles of immunodepletion were performed on CSF to fully deplete abundant proteins. To prevent order effects, the order of immunodepletion between samples was controlled by latin square randomization. The flow through was concentrated before the second round of immunodepletion. This was accomplished using a centrifugal evaporation unit (Eppendorf vacufuge). Flow through CSF was then immunodepleted again using the ProteoPrep 20 column, again accounting for order effects by latin square randomization. The second flow through was then desalted and concentrated with a Vivaspin 500 5 kD nominal molecular weight cutoff ultrafiltration unit (Sartorius Stedim). 10 μg of depleted CSF protein from each group was transferred to a new microcentrifuge tube for digestion and iTRAQ labeling. The removal of abundant proteins was confirmed by gel electrophoresis (Figure 2A).

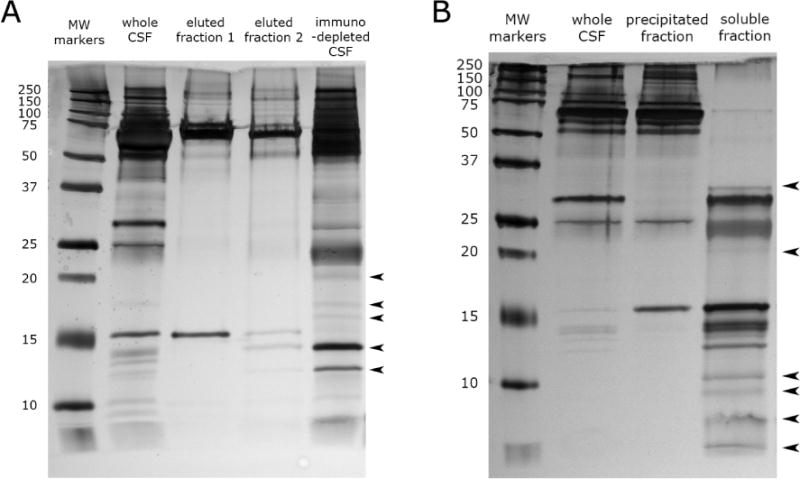

Figure 2.

(A) CSF immunodepletion by the Proteoprep 20 spin column. Lane 2 shows CSF before depletion with the Proteoprep 20 immunodepletion column. Lanes 3 and 4 show CSF proteins that were removed by serial passes through the immunodepletion column. The 5th lane shows the immunodepleted CSF. Arrows denote new protein bands that are now visible after immunodepletion. (B) CSF fractionation by acetonitrile precipitation. Lane 2 shows CSF before acetonitrile precipitation. Lane 3 shows CSF proteins that were precipitated by acetonitrile. The 4th lane shows the CSF proteins that where soluble in acetonitrile and were used for analysis in this study. Arrows denote new protein bands that are now apparent in CSF after abundant protein depletion by acetonitrile precipitation.

Precipitation of Abundant Proteins with Acetonitrile

1.5 ml of pooled CSF from each group was thawed on ice. Each sample was dialyzed for 24 hours against MilliQ H2O using an Ettan Mini-dialysis unit (GE Healthcare) at 4°C to remove biological salts. Acetonitrile precipitation was performed by adding a 1.5× volume of acetonitrile (Fisher Scientific) to each unit of dialized CSF. The mixture was then vortexed for 10 seconds and incubated for 1 hour at room temperature. Samples were then centrifuged at 15,000g for 10 minutes. Supernatant was then completely evaporated in a centrifugal evaporation unit to remove acetonitrile. The lyophilized acetonitrile soluble proteins were reconstituted in MilliQ H2O. Protein quantification was performed with the Bradford protein determination method (Pierce Biotechnology). 10 μg of depleted CSF protein from each group was transferred to a new microcentrifuge tube for digestion and iTRAQ labeling detailed below. This precipitation procedure was performed twice. In one run, peptides were concentrated with an SCX ziptip (Millepore), and in the other run, peptides were not ziptipped. The results of these two runs were combined in the data analysis phase. The separation of proteins by molecular weight proteins was confirmed by gel electrophoresis (Figure 2B).

Trypsin Digestion and iTRAQ Labeling

iTRAQ reagents are a set of isobaric reagents that allow for the identification and quantitation of up to four different samples simultaneously.94 Manufacturers protocols were followed (Promega Corperation).

2D LC-MS/MS

Samples were analyzed at the Genome Quebec Proteomics Platform. The sample was reconstituted in 10%ACN:0.1%TFA. Samples were diluted with 30 μl of 3%ACN:0.1%FA. A fraction of the sample was injected onto a Zorbax Bio-SCXII 50×0.8mm strong cation exchange column (Agilent). Elution from the SCX column was done by stepwise 40 μl injections of 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, 65, 80, 100, 125, 150, 180, 250 and 500 mM NaCl:0.1%FA:3%ACN. Eluted peptides were trapped and desalted with a Zorbax 300SB-C18 (5×0.3 mm) at 15 μl/min of 3%ACN:0.1%FA for 20 min. Nanoflow chromatography separation of peptides was performed with an 1100 series nanoHPLC system using a Biobasic C18 (10 × 0.075 mm) integrafrit column (New Objective). Peptides were eluted using a gradient of solvent A (0.1%FA) and solvent B (95%ACN:0.1%FA) starting at 5% B, reaching 20% B after 29 min, 40% B after 84 min and finally 90% B after 90 min at a flow rate of 200nl/min.

Eluted peptides were analyzed by tandem MS with a QTRAP 4000 (Sciex-Applied Biosystems). Enhanced MS scans in the 375–1500 m/z range were acquired at a 4000 amu/sec scan speed using an active Dynamic Fill time. Information-dependent MS/MS analysis was performed on the 3 most intense 2+, 3+ or 4+ charged ions. Charge determination was done by additional Enhanced Resolution scans of each candidate precursor ion at a speed of 250 amu/sec. A dynamic exclusion was used to limit resampling of previously selected ions to a maximum two events within 180 sec. Three scans were summed, MS/MS scans for each precursor were acquired between 100–1600 m/z at a scan speed of 4000 amu/sec. Fixed fill time was set at 20 ms with Q0 trapping and rolling collision energy of +5 eV.

Database Search

Immunodepleted CSF and acetonitrile soluble CSF was searched using a UniProt human protein database obtained on March 2008 containing 71371 sequences.89 Spectral processing included peak smoothing and centroiding without de-isotoping and peak picking for peaklist generation was done with the Mascot distiller ver.2.1 (Matrixscience) algorithm using tryptic peptides with up top 1 miscleavage, methylthiocysteine as fixed modification, methionine oxidation, iTRAQ modified N-terminus, lysine and tyrosines as the variable modification with a 1.5 Da precursor and 0.8 MS/MS fragment tolerances was used to search the databases.

Protein quantitation was done using the Interrogator algorithm of ProQuant ver1.4 (Applied Biosystems) using the same database used for the Mascot searches. N-term iTRAQ and methylthiocysteines were used as fixed modifications. Methionine oxidation and iTRAQ modified lysine and tyrosine were used as variable modifications. Search tolerances were identical to those used for Mascot. Protein grouping was performed with the Progroup software (Applied Biosystems).

To minimize false positive protein identifications, a protein was only considered if a minimum of two peptides belonging to the protein were identified (ProtSc ≥ 2).

Expanded Cohort for ELISA

Two proteins from the initial proteomic screen were selected for follow up for validation by ELISA and analyzed individually. Cystatin C was chosen because the initial proteomics screen determined that it was increased in both symptomatic and asymptomatic DD and because of its association with inflammation.83 In addition, cystatin C was previously proposed as a putative CSF biomarker for pain,44, 67 although this claim is controversial.31 Hemopexin was selected because the initial proteomic screen found that it was significantly increased in painful DD, but not pain-free DD. Furthermore, hemopexin is of interest because of its association with nerve injury.52

Due to the constraints of our study design, ie. a proteomic screen followed by validation studies with ELISA, it was not possible to estimate sample sizes a priori. The “1-Way ANOVA Pairwise, 2-Sided Equality” calculator on powerandsamplesize.com was used to perform a post-hoc power analysis (power, 1 – β = 0.7, type 1 error rate, α = 10%), using values based on the results of the magnitude in change of protein levels, coupled with literature values of means and variance for cystatin C90 and hemopexin92. Calculated sample sizes per pairwise comparison was 31 for cystatin C and 39 for hemopexin.

ELISA Assays

Commercial ELISA kits for cystatin C and hemopexin were used. Cystatin C human ELISA was purchased from Biovendor R&D (Asheville, NC; Cat# RD191009100, Lot E13-093). Human hemopexin ELISA was purchased from Immunology Consultants Laboratory, Inc (Portland, OR; Cat# E-80HX, Lot 12). Manufacturers’ protocols were followed without modification. Placement of samples on the ELISA microplates was randomized to minimize any location and order biases. All samples were processed in duplicate using a microplate reader (Spectramax M2E, Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA).

Statistical Analysis

In the exploratory proteomic analysis of CSF, peptides were identified by mass spectrometry, and the ratio of iTRAQ isobaric reporter tags between groups was measured. Multiple peptides from the same parent protein may be observed. The p-value denoted in Tables 2 and 3 reflects the consistency of the ratio of iTRAQ tags on the peptides belonging to the same protein.

Table 2.

Differentially expressed proteins from proteoprep 20 immunodepleted CSF

| Protein name | Accession number | ProtSc | Ratio Pain-free DDD vs Control | Ratio Painful DDD vs control | Postulated Mechanistic Association | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apolipoprotein E precursor | P02649 | 24.38 | 1 P=1# |

1.07 P<0.001* |

Peripheral nerve injury | 8, 40 |

| Hemopexin precursor | P02790 | 12.36 | 1.08 P= 0.18# |

1.12 P<0.05* |

Peripheral nerve injury | 14, 65, 66 |

| Apolipoprotein D precursor | P05090 | 7.45 | 1.08 P=0.32# |

1.14 P=0.032* |

Peripheral nerve injury | 8, 40 |

| Apolipoprotein A-IV precursor | P06727 | 5.49 | 1.04 P=0.54# |

1.16 P=0.023* |

Peripheral nerve injury | 9 |

| ProSAAS precursor | Q9UHG2 | 5.54 | 1.08 P=0.062# |

1.17 P<0.0001* |

Neuropeptide processing | 28, 37, 84, 120 |

| Beta-2-microglobulin precursor | P61769 | 2.04 | 1.18 P=0.091# |

1.24 P=0.05# |

Microglial activation | 6, 22, 23, 43 |

| Prostaglandin-H2 D-isomerase precursor | P41222 | 10.12 |

0.86 P<0.0001* |

0.87 P<0.0001* |

Inflammation | 88, 95, 98, 99 |

| Cystatin-C precursor | P01034 | 8.21 |

1.08 P<0.001* |

1.13 P<0.0001* |

Inflammation | 1, 19, 31, 33, 67 |

| Alpha-1 -antichymotrypsin precursor | P01011 | 7.92 |

1.18 P<0.001* |

1.27 P<0.0001* |

Inflammation | 13, 15, 29, 38 |

| Serum albumin precursor | P02768 | 5.09 |

0.82 P=0.036* |

0.96 P=0.681# |

Inflammation | 54, 81, 97, 109 |

| Serine/cysteine proteinase inhibitor clade G member 1 splice variant 2 | Q5UGI6 | 4.26 |

0.90 P<0.05* |

0.96 P=0.44# |

Inflammation | 18 |

| Gelsolin | Q5T0I2 | 3.99 |

1.16 P<0.05* |

1.17 P<0.01* |

Inflammation | 85, 115 |

| Chromogranin-A precursor | P10645 | 3.4 |

1.44 P=0.001* |

1.51 P=0.001* |

Inflammation | 20, 27, 45 |

| Superoxide dismutase | P00441 | 4.57 |

0.78 P<0.001* |

0.78 P=0.069# |

Free radical scavenger | 49, 68 |

| Extracellular superoxide dismutase [Cu-Zn] precursor | P08294 | 3.05 |

0.89 P<0.01* |

0.93 P=0.11# |

Free radical scavenger | 49, 68 |

| Neural cell adhesion molecule L1-like protein precursor | O00533 | 7.02 |

1.13 P<0.05* |

1.14 P=0.06# |

Cell adhesion | 46 |

| Amyloid-like protein 1 precursor | P51693 | 5.78 |

1.14 P<0.05* |

1.17 P<0.05* |

NMDA receptor homeostasis | 21 |

| Calsyntenin-1 precursor | O94985 | 2.75 |

0.96 P<0.05* |

1.01 P=0.69# |

Axonal transport | 112 |

ProtSc (Protein Score) is a statistical calculation of protein confidence reflecting the number and uniqueness of the observed peptides that are attributed to a particular parent protein.

The p-values reflect the consistency of the observed ratio of iTRAQ tags on peptides belonging to the same parent protein.

denotes P-values which are Benjamini-Hochberg significant at false discovery rate < 0.2.

denotes P-values which are not Benjamini-Hochberg significant at false discovery rate < 0.2.

Table 3.

Differentially expressed proteins from acetonitrile precipitated CSF

| Protein name | Accession number | ProtSc | Ratio Pain-free DDD vs Control | Ratio Painful DDD vs control | Postulated Mechanistic Association | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apolipoprotein A1 | Q9Y355 | 4.02 |

0.65 P<0.05* |

1.03 P=0.82# |

Peripheral nerve injury | 9 |

| Insulin-like growth factor II precursor | P01344 | 2.52 | 0.99 P=0.93# |

1.23 P<0.05* |

Peripheral nerve injury | 41 |

| Prosaposin | Q53FJ5 | 2.01 | 1.09 P=0.20# |

1.29 P<0.05* |

Peripheral nerve injury | 47, 111 |

| ProSAAS precursor | Q9UHG2 | 9.58 | 1.06 P=0.28# |

1.15 P<0.01* |

Neuropeptide processing | 28, 37, 84, 120 |

| Cystatin-C precursor | P01034 | 14 |

1.18 P=0.0001* |

1.21 P<0.0001* |

Inflammation | 1, 19, 31, 33, 67 |

| Serum albumin precursor | P02768 | 12 |

0.81 P<0.0001* |

0.90 P<0.0001* |

Inflammation | 54, 81, 97, 109 |

| Prostaglandin-H2 D-isomerase precursor | P41222 | 9.64 |

0.92 P<0.05* |

0.96 P=0.38# |

Inflammation | 88, 95, 98, 99 |

| Orosomucoid 1 | Q5T539 | 4.01 |

0.49 P<0.05* |

0.84 P=0.26# |

Inflammation | 32, 76 |

| Alpha-2-HS-glycoprotein precursor | P02765 | 2.13 |

0.67 P<0.05* |

0.75 P=0.25# |

Inflammation | 24, 57, 114 |

ProtSc (Protein Score) is a statistical calculation of protein confidence reflecting the number and uniqueness of the observed peptides that are attributed to a particular parent protein.

The p-values reflect the consistency of the observed ratio of iTRAQ tags on peptides belonging to the same parent protein.

denotes P-values which are Benjamini-Hochberg significant at false discovery rate < 0.2.

denotes P-values which are not Benjamini-Hochberg significant at false discovery rate < 0.2.

The unused ProteinScore (ProtSc) is a statistical calculation of protein confidence. It denotes the number of peptides observed that are unique to a particular parent protein. A completely unique peptide sequence increases ProtSc by 1, and shared sequences increase ProtSc by fractional amounts. In this study, a minimum ProtSc cutoff of 2 was selected, corresponding to 99% confidence of protein identification.

To control for multiple comparisons in the proteomic analysis, the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure was utilized.53 The Benjamini-Hochberg critical value for a false discovery rate (FDR) was set to 0.02.

The ELISA data was analyzed and graphed using Prism (Graphpad). Comparisons between groups were made using one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post-hoc tests comparing all groups to each another. Correlation analysis was performed using the non-parametric Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient on data from all groups (healthy controls, pain-free DD, painful DD).

Results

Study Participants

A total of 54 participants were enrolled in the study following recruitment at the TC Spine Clinic or by telephone screening, consisting of 39 pain-free subjects and 15 LBP patients with intervertebral DD. Of the 39 pain pain-free subjects which were enrolled, only 38 subjects who completed the study met the inclusion criteria after examination (one subject had a ventriculoperitoneal shunt and was excluded). Following MRI grading, 25 pain-free subjects were determined to not have intervertebral DD, while the other 13 were found to have pain-free DD. In the LBP patient group, only 13 of the 15 patients met inclusion criteria (one patient was excluded because of an intervertebral disc herniation, and another was excluded due to hepatitis C infection). Table 1A shows the characteristics of the subject and patient populations in the study. Because pain-free individuals were recruited and then separated into ‘with DD’ and ‘without DD’ groups based on post hoc MRI results, age differences were expected and were observed between groups. The characteristics of the exploratory cohort created for the initial proteomic screen (formed to reduce expected age and sex differences between painful vs nonpainful DD groups) are provided in Table 1B.

CSF Sample Preparation: Immunodepletion (Exploratory Cohort)

The ProteoPrep 20 immunodepletion column is designed to remove the top 20 most abundant proteins in plasma. As there was no depletion column designed specifically for CSF, the Proteoprep 20 immunodepletion spin column was adapted for use with CSF. The ProteoPrep 20 immunodepletion column removes: albumin, IgG, transferrin, fibrinogen, IgA, alpha-2-macroglobin, IgM, alpha-1-antitrypsin, complement C3, haptoglobin, apolipoprotein A1, apolipoprotein A2, apolipoprotein B, acid-1-glycoprotein, ceruloplasmin, compliment C4, complement C1q, IgD, prealbumin, and plasminogen. All of these proteins are found in CSF.

The ProteoPrep 20 immunodepletion successfully removed abundant proteins as shown by gel electrophoresis in Figure 2A. After immunodepletion, a number of protein bands were no longer visible while other bands increased in intensity (arrows), demonstrating that the removal of highly abundant proteins resulted in an increase in the relative abundance of the low abundance proteins. The majority of albumin was removed in the first depletion step as shown by the removal of the large band at 66 kDa. The second depletion removed additional albumin among other proteins.

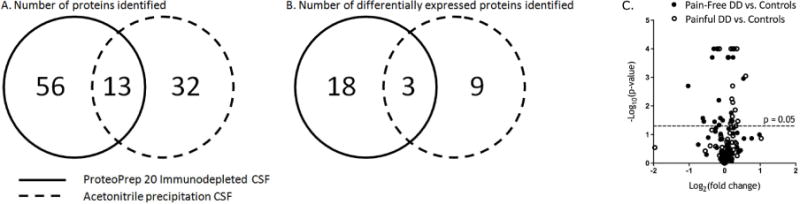

A total of 56 proteins were detected by mass spectrometry after immunodepletion (Figure 3A, Supplemental Table 1. 18 of these proteins were differentially expressed compared to pain-free controls without DD (Figure 3B, Table 2).

Figure 3.

Number of proteins detected and differentially expressed in CSF. (A) The total number of proteins identified by the two different sample preparation methods is shown. (B) The number of differentially expressed proteins is shown. Using different sample preparation techniques, distinct differentially expressed proteins were identified from CSF. (C) A volcano plot of iTRAQ quantification ratio in pain-free and painful intervertebral disc degeneration is shown. Points above the horizontal line represent proteins with significant (p<0.05) differences when compared to healthy controls, with points with FDR <0.02 marked as “×”.

CSF Sample Preparation – Acetonitrile Precipitation (Exploratory Cohort)

Acetonitrile precipitation was also used to remove abundant proteins from CSF. Acetonitrile precipitates larger proteins before smaller proteins, and thus, highly abundant large proteins can be separated from smaller proteins by this method.16 An additional benefit to this method over immunodepletion is that it causes smaller peptides to be released from larger carrier proteins.75 In contrast, immunodepletion can result in the loss of small peptides if they are associated with immunodepleted carrier proteins such as albumin.

The silver stained gel electrophoresis of acetonitrile precipitated CSF demonstrates the separation of high molecular weight proteins from low molecular weight proteins (Figure 2B). Notably, the precipitation removed the majority of albumin (MW = 66.5 kDa), the most abundant CSF protein, from the sample. This resulted in an increase in the relative abundance of smaller (<35 kDa), low abundance proteins (arrows).

The number of proteins identified by mass spectrometry in the acetonitrile precipitated samples was 32 (Figure 3A, Supplemental Table 2). 9 of these proteins were differentially expressed compared to pain-free controls without DD (Figure 3B, Table 3).

Identification of Differentially Expressed Proteins in CSF from Individuals with Painful and Pain-Free Intervertebral Disc Degeneration compared to Controls without Disc Degeneration (Exploratory Cohort)

The majority of proteins detected in this study were not significantly different between individuals with either painful or pain-free DD compared to controls without pain or DD. The proportion of proteins that showed differential changes in expression are depicted by volcano plot (Figure 3C).

A total of 15 proteins were identified that were differentially expressed between pain-free individuals with or without DD. These proteins are prostaglandin-H2-D-isomerase, cystatin C, α-1-antichymotrypsin, serine/cysteine proteinase inhibitor clade G, gelsolin, chromogranin A, superoxide dismutase, extracellular superoxide dismutase, neural cell adhesion molecule L1-like protein, amyloid-like protein 1, albumin, calsynthenin-1, orosomucoid-1, apolipoprotein A1, and α-2-HS glycoprotein (Tables 2&3). Of these 15 proteins, 6 were similarly dysregulated in patients with painful DD.

A total of 8 proteins were identified that were differentially expressed in LBP patients but not in pain-free individuals with DD compared to controls. These proteins are hemopexin, apolipoproteins A-IV, D, and E, insulin-like growth factor II, prosaposin, proSAAS, and β-2-microglobulin (Tables 2&3).

CSF Levels of Cystatin C Correlate to Intervertebral Disc Degeneration Severity but not to Pain Intensity or Physical Disability (Full Cohort)

The iTRAQ exploratory experiments with both ProteoPrep 20 immunodepleted and acetonitrile precipitated CSF identified cystatin C as increased in pain-free and in painful DD compared to controls without DD. Cystatin C is a protein associated with inflammation.83 Additionally, CSF cystatin C levels have previously been shown to correlate with pain status,44, 67 although this idea has been at the center of some controversy.31

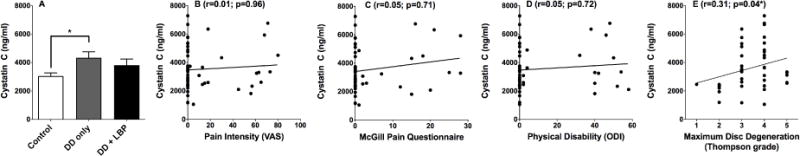

To further explore and validate the association between cystatin C levels and non-painful DD, levels of cystatin C were measured by ELISA in the full cohort. The ELISA results confirmed that levels of cystatin C were significantly greater in the pain-free DD group when compared to healthy individuals (p<0.05; Figure 4A). A Spearman nonparametric correlation found no association with cystatin C and pain intensity as determined by the visual analogue scale (VAS) (r=0.007; p=0.96; Figure 4B). CSF levels of cystatin C were also examined for correlation with the scores on the McGill Pain Questionnaire (MPQ) and no significant correlation was found (r=0.05; p=0.71; Figure 4C). Similar analysis between cystatin C levels and disability, as determined by the Oswestry Disability Index (ODI), also demonstrated no correlation (r=0.05; p=0.72; Figure 4D). However, cystatin C levels significantly correlated with the severity of DD as determined by the maximum score of one or more lumbar discs according to the Thompson scale (r=0.31; p=0.04; Figure 4E). The correlation between cystatin C levels and DD severity is consistent with the results of the initial proteomics screen, and suggest that cystatin C levels are associated with DD but not pain.

Figure 4.

Cystatin C levels in CSF are increased in subjects with degenerative disc disease. (A) CSF Cystatin C levels were compared between healthy, asymptomatic DD, and painful DD subjects. A statistical difference was observed between groups by ANOVA (p = 0.04). Bonferroni multiple comparison tests determined that the healthy group was statistically different from the asymptomatic DD group (p < 0.05). (B) Spearman nonparametric correlation analysis was used to test for a correlation between CSF cystatin C levels and visual analogue scale (VAS) values; no correlation was observed. (C) Similarly, no significant correlation was observed between CSF cystatin C levels and total McGill Pain Questionnaire (MPQ) score. (D) No significant correlation was observed between CSF cystatin C levels and the Oswestry low back disability index (version 2.0). (D) In contrast, CSF cystatin C levels and maximum lumbar intervertebral disc degeneration were significantly correlated (r=0.31; p=0.04) when tested with Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient.

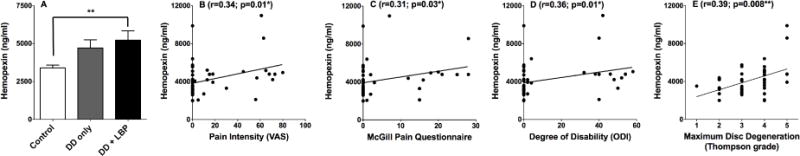

CSF Levels of Hemopexin Correlate with Pain Intensity, Physical Disability and Intervertebral Disc Degeneration Severity (Full Cohort)

The iTRAQ exploratory experiments with ProteoPrep 20 immunodepleted CSF identified hemopexin as differentially expressed in painful but not pain-free DD. Hemopexin is a protein that has been found to be increased after nerve injury.52

To further explore the association between hemopexin and painful DD, hemopexin levels in CSF were quantified by ELISA in the full cohort. Levels of hemopexin were significantly greater in the painful DD group when compared to controls without DD (p<0.01; Figure 5A). Conversely, hemopexin levels in the pain-free DD group were not significantly increased when compared to healthy controls. CSF hemopexin levels and pain intensity (as measured by the VAS) were significantly correlated (r=0.34; p=0.01; Figure 5B). Likewise, CSF levels of hemopexin correlated with total MPQ (r=0.31; p=0.03; Figure 5C), as well as the sensory (r=0.30; p=0.03) and affective subscales (r=0.34; p=0.02) of the MPQ (data not shown). In addition, a significant correlation was observed between hemopexin levels and physical disability as measured by ODI (r=0.36; p=0.01; Figure 5D). Finally, hemopexin levels correlated with maximum lumbar intervertebral DD severity, as measured by the Thompson scale (r=0.39; p=0.008; Figure 5E). Overall, CSF hemopexin levels were associated with painful DD, consistent with the results from the exploratory proteomic screen.

Figure 5.

Hemopexin levels in CSF are increased in subjects with LBP. (A) CSF Hemopexin levels were compared between healthy, asymptomatic DD, and painful DD subjects. A statistical difference was observed between groups by ANOVA (p = 0.004). Bonferroni multiple comparison tests determined that the healthy group was statistically different from the painful DD group (p < 0.01). (B) Spearman nonparametric correlation was used to test for a correlation between CSF hemopexin levels and visual analogue scale (VAS) values. A significant correlation was observed (r=0.34; p=0.014). (C) Similarly, a significant correlation was also observed between CSF hemopexin levels and the total McGill Pain Questionnaire score (r=0.31; p=0.03). (D) CSF hemopexin levels also significantly correlated with the Oswestry low back disability index (r=0.36; p-0.01). (E) Spearman’s nonparametric correlation was also used to test for a correlation between hemopexin levels and maximum lumbar intervertebral disc degeneration according to the Thompson scale. A significant correlation was observed (r=0.39, p=0.008).

Discussion

Differential shotgun proteomics was performed on CSF from control subjects, subjects with non-painful DD, and LBP patients with painful DD. Pain-free individuals with DD or herniation have not been included in previous human pain studies examining CSF for pathophysiological markers. Indeed, this is the first study to include such a group, thus allowing for identification of pain-specific biochemical markers through specific comparison of pain-related and non-pain-related components of DD.4, 11, 59, 60, 62, 117

Differential Protein Expression in CSF suggests that Inflammation is Associated with Intervertebral Disc Degeneration but not with Chronic Low Back Pain

There were 15 proteins identified that were differentially expressed in the presence of DD regardless of pain state, many of which are associated with inflammation. Proteins that were increased in DD included: cystatin C, alpha-1-antichymotrypsin, gelsolin, chromogranin-A, neural cell adhesion molecule L1-like protein, and amyloid-like protein 1. Proteins that were decreased in DD included prostaglandin-H2 D-isomerase, serine/cysteine proteinase inhibitor clade G, superoxide dismutase, extracellular superoxide dismustase, calsyntenin-1, serum albumin, orosomucoid 1, and alpha-2-HS-glycoprotein.

Cystatin C

Cystatin C is a small secreted cysteine protease inhibitor.1 CSF concentrations of cystatin C have been proposed to be indicative of pain,19, 67 although this has been disputed.31 In this study, cystatin C levels were higher in both DD groups compared to the group without DD. These results agree with the body of work suggesting that cystatin C is a marker for inflammation but is not specific to pain.33 Because cystatin C was observed using both separation methods and was previously proposed as a marker for inflammation, it was selected for additional analysis by ELISA. In agreement with the proteomics screen, cystatin C correlated with the severity of DD but not with pain or disability (Figure 4).

Alpha-1 antichymotrypsin

Alpha-1 antichymotrypsin is a serine protease inhibitor which is a type of protein that is increased in response to inflammation13. It was increased by DD and is also increased in inflammatory conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis.15 It exhibits anti-inflammatory activities, cleaving proteases such as cathepsin G29 and chymases38 found in immune cells.

Gelsolin

Gelsolin is important for inflammatory cell migration.115 Gelsolin knockout mice exhibit blunted responses to inflammation due to attenuated infiltration, chemotaxis and apoptosis.85 Increased gelsolin expression in patients with DD suggests ongoing inflammation and immune cell migration.

Chromogranin-A

Chromogranins are expressed ubiquitously in secretory cells of the immune, nervous, and endocrine systems.45 Chromogranin A is increased in other conditions involving inflammation, such as rheumatoid arthritis.27 Chromogranin A levels correlate with soluble tumor necrosis factor receptors, which are markers of systemic inflammation.20

Prostaglandin-H2 D-isomerase

Prostaglandin-H2 D-isomerase, also known as prostaglandin D-2 (PGD2) synthase, was reduced in both painful and non-painful DD. PGD2 supresses inflammation via inhibition and blockade of nuclear factor-κB kinase,95, 98,99 resulting in reduced expression of proinflammatory cytokines interleukin-1β, interleukin-6, tumor necrosis factor-α secretion and iNOS from macrophages.3, 91, 113 In PGD2 synthase knockout animals, inflammation is more severe and resolution of inflammation is impaired.88 Resolution of inflammation may be similarly impaired in individuals with DD.

Serum albumin

Serum albumin CSF levels were reduced in DD. Hypoalbuminemia is commonly observed in patients with inflammatory diseases such as pneumonia, rheumatoid arthritis, bacterial infection81 and in hemodialysis patients.54 Reduced serum albumin levels have also been observed in patients following surgery.97, 109 Reduced albumin levels in DD are therefore consistent with inflammation.

Superoxide dismutase and extracellular superoxide dismutase

Superoxide dismutase catalyses the conversion of the superoxide anion to hydrogen peroxide, and plays an essential role in antioxidant defense systems. Increased superoxide dismutase expression helps resolve inflammation in colitis,101 inflammatory arthritis,116 pulmonary fibrosis,39 emphysema,35 and hypoxia induced brain injury.118 Superoxide dismutase levels in DD were decreased compared to healthy controls, which may reflect ongoing oxidative stress and chronic inflammation in intervertebral DD. In agreement, animal models have demonstrated that superoxide dismutase levels decrease in age-related intervertebral DD.49

Serine/cysteine proteinase inhibitor clade G

Serine/cysteine proteinase inhibitor clade G, also known as C1 inhibitor, is a complement inhibitory protein that irreversibly binds to and inactivates components of the C1 complex of the complement pathway.119 C1 inhibitor levels were reduced in DD when compared to healthy controls; this reduction could enhance complement activity and contribute to disc inflammation. Indeed, study of human disc tissues have demonstrated enhanced complement activation through the classical pathway in degenerated discs.42

Orosomucoid 1

Orosomucoid 1 has immunosuppressing effects, including inhibition of leukocyte rolling and adhesion, migration, chemotaxis,76 and proliferation.32 CSF levels of orosomucoid 1 were reduced in DD, suggesting that reduced basal immunosuppression by orosomucoid may be contributing to ongoing intervertebral DD.

Alpha-HS-2-glycoprotein: Alpha-HS-2-glycoprotein, also known as fetuin-A, has anti-inflammatory activities.114 Additionally, expression of Alpha-HS-2-glycoprotein is known to be negatively regulated by proinflammatory cytokines such as interferon-γ,57 interleukin-1β and interleukin-6.24 The reduced levels of alpha-HS-2-glycoprotein observed in CSF of subjects with intervertebral DD is consistent with the suggestion that ongoing inflammation is occurring during intervertebral DD.

Other proteins

Levels of neural cell adhesion molecule L1-like protein, amyloid like protein-1, and calsyntenin-1 were differentially regulated in CSF by intervertebral DD. Neural cell adhesion molecule L1-like protein is involved in neuron-neuron adhesion and neurite outgrowth.46 Amyloid like protein-1 is postulated to play a role in NMDA receptor homeostasis.21 Calsyntenin-1 is a transmembrane protein which plays a role in anterograde axonal transport.112 Alpha-2-HS-glycoprotein is a protein whose function is poorly understood. It is thought to act as a functional antagonist of transforming growth receptor-beta, bone morphogenic proteins,26 and insulin receptor tyrosine kinase.70

Differential Protein Expression in CSF suggests that Chronic Low Back Pain Associated with Intervertebral Disc Degeneration has a Neuropathic Component

There were 8 proteins identified that were increased in painful DD compared to pain-free controls without DD. They included apoliprotein E, D, and A-IV, hemopexin, ProSAAS, β-2-microglobulin, prosaposin, and insulin-like growth factor II. Many of these proteins have been previously linked to nerve injury.

Hemopexin

After peripheral nerve injury, hemopexin is expressed by Schwann cells, endoneurial fibroblasts, and invading macrophages.14 Hemopexin levels are elevated in injured nerves,65 remain elevated in states of ongoing Wallerian degeneration,66, 107 and have been shown to negatively regulate inflammatory Th17 T cell responses.93 Likewise, nerve injury also alters T cell responses.69, 79 Consistent with our observation of increased hemopexin in CSF of LBP patients, others have observed a reduction in Th17 T cells in LBP patients and in chronic neuropathic pain patients.63, 64 The observation that the increase in hemopexin levels in the CSF from patients with painful DD but not in pain-free individuals with DD suggests that nerve injury may play a role in the pathophysiology of painful DD. Due to the association between nerve injury and hemopexin levels, hemopexin was selected for further analysis by ELISA. Consistent with the exploratory proteomics screen, hemopexin levels were found to correlate with pain intensity, physical disability and DD severity (Figure 5).

Apolipoproteins

Compared to pain-free controls without DD, apolipoproteins A-IV, D, and E were all significantly increased in the painful DD group but not in the pain-free DD group. Apolipoproteins are important in remyelination, which occurs after axonal injury. Apolipoproteins A-IV,9 D,8 and E,96 accumulate in nerves after peripheral nerve injury. As Schwann cells attempt to remyelinate, apolipoprotein-D and -E expression are induced.40 The finding that apolipoproteins are increased in the CSF of patients with painful DD is further evidence supporting the hypothesis for a neuropathic component to the pathophysiology of painful DD.

Insulin-like growth factor II

Insulin-like growth factor II was increased in the CSF in patients with painful but not pain-free DD. Insulin-like growth factor II is increased in nerves after nerve injury.41 Thus, its upregulation in the CSF of patients with painful DD is consistent with the hypothesis that nerve injury is playing a role in the generation of discogenic pain.

Prosaposin

Prosaposin was upregulated in the CSF of the painful DD group. Prosaposin is a myelinotrophic protein that is secreted by neurons after nerve injury.111 It acts within nerves to provide trophic support to neurons and promote regeneration.47 Elevated CSF levels of prosaposin further suggests that nerve injury contributes to painful DD. Importantly, there was no increase in prosaposin levels in the CSF of the pain-free DD group.

Beta-2-microglobulin

Beta-2-microglobulin is a component of the class I major histocompatability antigens, and is normally expressed on immune cells,22 including microglia.43 It was increased in the CSF of patients with painful DD. CSF beta-2 microglobulin levels are increased in inflammatory conditions within the CNS, such as multiple sclerosis,5 Alzhiemer’s disease,25 HIV dementia,72 bacterial and viral meningitis,106 and spinal cord injury.102 Nerve injury induces central sensitization and central inflammation,56 which is consistent with the observation of increased beta-2-microglobulin levels in painful DD.

ProSAAS

ProSAAS was found to be increased in the group with painful DD using both the ProteoPrep 20 and the acetonitrile precipitation methods. ProSAAS is a neuroendocrine peptide that inhibits pro-hormone convertase 1/3 at nanomolar concentrations.37 Pro-hormone convertases are involved with the proteolytic cleavage of proteins to mature peptides, including the opioid peptides β-endorphin and dynorphin.28, 84, 120 Neuropeptide processing enzymes are also differentially regulated in CSF from patients with painful lumbar herniated discs61 and in disc injury animal models,78 suggesting a role for altered neuropeptide processing in the mechanisms underlying painful DD.

Implications

Intervertebral DD includes a significant inflammatory component.110 We observed that a number of inflammatory markers were increased in the CSF of patients with DD, regardless of pain status, suggesting that inflammation alone is not sufficient to produce chronic LBP. While animal models have demonstrated increases in inflammatory mediators following disc injury or compression,77 these increases are transient,78 and therefore may not be crucial for the development of pain. Studies in human discs found no correlation between pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β and IL-6 in lumbar herniated discs and sciatic pain.2 Our work supports the idea that disc inflammation alone is insufficient for the development of LBP.

Our analysis yielded a number of differentially expressed proteins in individuals with painful DD. A number of these – hemopexin, various apolipoproteins, insulin-like growth factor II, prosaposin, and fibronectin – are increased after nerve injury. These findings are consistent with the hypothesis that nerve injury plays an important role in chronic LBP associated with DD.50, 77

While differential protein expression in the CSF was observed in this study, the source(s) are unknown. One possibility is that mediators move from the disc or surrounding vertebral bones to the CSF. After nerve injury, both the blood-spinal barrier30 and the blood-nerve barrier58 become disrupted, which may allow movement of peripheral molecules and leukocytes into the CSF. Other explanations include the possibility that nerve injury creates an edematous state resulting in a flow of molecules from injured nerves to CSF,87 or that CSF alterations reflect peripherally-driven changes in the central nervous system such as central sensitization and neuroinflammation.100

A limitation of CSF proteomics is the challenge of detecting low abundant proteins. In this study, two sample preparation techniques, immunodepletion and protein precipitation were used to remove abundant proteins. Immunodepletion was carried out with a column designed to remove abundant proteins from serum. The development of CSF specific immunodepletion tools will likely improve the ability to examine low abundance proteins in CSF. Likewise, the acetonitrile precipitation procedure was adapted from serum proteomics experiments. It is possible that the use of other organic solvents, or optimization of the precipitation procedure to CSF proteins, would yield different results. Indeed, while proteomic studies allow for an unbiased account of disease-related changes in protein levels, the information gained from these studies must be validated using additional approaches and models.

An additional limitation of this study is that it was not sufficiently powered to examine correlations of either cystatin C and hemopexin specifically within the painful DD group. Adequately powered studies should evaluate this in the future.

Conclusions

The presence of a neuropathic component contributing to discogenic LBP suggests that LBP may respond to treatments targeting neuropathic mechanisms, even in the absence of sciatica. This is consistent with evidence that medications typically used for neuropathic pain, such as tricyclic antidepressants and antiepileptic medications, have efficacy for LBP.17 In addition, this study builds on the data from animal models demonstrating that pain associated with intervertebral DD has neuropathic components.77 Our results also add to the growing body of evidence linking inflammation to intervertebral DD.80 However, our study suggests that inflammatory mechanisms are not central to pain genesis, providing a possible explanation for the lack of consistent benefits from treatments targeting disc inflammation, such as intradiscal steroid injection.104

Finally, these results provide evidence that CSF can be used to study mechanisms underlying painful DD in humans. Future studies may uncover additional clinically-relevant mechanisms underlying LBP that could be targeted for treatment and may provide clues into why some individuals have pain and others do not.

Perspective.

Cerebrospinal fluid was examined for differential protein expression in healthy controls, pain-free adults with asymptomatic intervertebral disc degeneration, and low back pain patients with painful intervertebral disc degeneration. While disc degeneration was related to inflammation regardless of pain status, painful degeneration was associated with markers linked to nerve injury.

Intervertebral disc degeneration induces differential protein expression in CSF

Pain-free disc degeneration is associated with biochemical markers of inflammation

Painful disc degeneration is associated with biochemical markers of nerve injury

Mechanistic insights can be gained by probing for biochemical alterations in CSF

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Ms. Line Roy, Dr. Lucy Vulchanova, Dr. Carolyn Fairbanks, Dr. Patrick Braun and Dr. Akanksha Srivastava for intellectual and technical support throughout the course of this project.

Supported by grants from the National Institutes for Health (R21 DA020108) and the Minnesota Medical Foundation to LJK and LSS, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research/Canadian Pain Society/Astrazeneca Biology of Pain Young Investigators Operating Grant XCP-83755 and CIHR Operating Grant MOP-126046 to LSS, the Canadian Foundation for Innovation and the Quebec Network for Oral and Bone Health Research for Infrastructure support to LSS and TKL and the Fonds de la recherche en sante Quebec Salary Award (Bourse de chercheur-boursier “Junior 2”) to LSS. The sponsors had no role in the study design, collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Aldred AR, Brack CM, Schreiber G. The cerebral expression of plasma protein genes in different species. Comp Biochem Physiol B Biochem Mol Biol. 1995;111:1–15. doi: 10.1016/0305-0491(94)00229-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andrade P, Hoogland G, Garcia MA, Steinbusch HW, Daemen MA, Visser-Vandewalle V. Elevated IL-1beta and IL-6 levels in lumbar herniated discs in patients with sciatic pain. Eur Spine J. 2013;22:714–720. doi: 10.1007/s00586-012-2502-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Azuma Y, Shinohara M, Wang PL, Ohura K. 15-Deoxy-delta(12,14)-prostaglandin J(2) inhibits IL-10 and IL-12 production by macrophages. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;283:344–346. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.4783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Backryd E, Ghafouri B, Carlsson AK, Olausson P, Gerdle B. Multivariate proteomic analysis of the cerebrospinal fluid of patients with peripheral neuropathic pain and healthy controls – a hypothesis-generating pilot study. J Pain Res. 2015;8:321–333. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S82970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bagnato F, Durastanti V, Finamore L, Volante G, Millefiorini E. Beta-2 microglobulin and neopterin as markers of disease activity in multiple sclerosis. Neurol Sci. 2003;24(Suppl 5):S301–304. doi: 10.1007/s10072-003-0180-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bernier GM, Fanger MW. Synthesis of 2 -microglobulin by stimulated lymphocytes. J Immunol. 1972;109:407–409. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boden SD, Davis DO, Dina TS, Patronas NJ, Wiesel SW. Abnormal magnetic-resonance scans of the lumbar spine in asymptomatic subjects. A prospective investigation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1990;72:403–408. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boyles JK, Notterpek LM, Anderson LJ. Accumulation of apolipoproteins in the regenerating and remyelinating mammalian peripheral nerve. Identification of apolipoprotein D, apolipoprotein A-IV, apolipoprotein E, and apolipoprotein A-I. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:17805–17815. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boyles JK, Zoellner CD, Anderson LJ, Kosik LM, Pitas RE, Weisgraber KH, Hui DY, Mahley RW, Gebicke-Haerter PJ, Ignatius MJ, Shooter EM. A role for apolipoprotein E, apolipoprotein A-I, and low density lipoprotein receptors in cholesterol transport during regeneration and remyelination of the rat sciatic nerve. J Clin Invest. 1989;83:1015–1031. doi: 10.1172/JCI113943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brisby H, Olmarker K, Larsson K, Nutu M, Rydevik B. Proinflammatory cytokines in cerebrospinal fluid and serum in patients with disc herniation and sciatica. Eur Spine J. 2002;11:62–66. doi: 10.1007/s005860100306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brisby H, Olmarker K, Rosengren L, Cederlund CG, Rydevik B. Markers of nerve tissue injury in the cerebrospinal fluid in patients with lumbar disc herniation and sciatica. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1999;24:742–746. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199904150-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Buckwalter JA. Aging and degeneration of the human intervertebral disc. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1995;20:1307–1314. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199506000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Calvin J, Neale G, Fotherby KJ, Price CP. The relative merits of acute phase proteins in the recognition of inflammatory conditions. Ann Clin Biochem. 1988;25(Pt 1):60–66. doi: 10.1177/000456328802500108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Camborieux L, Bertrand N, Swerts JP. Changes in expression and localization of hemopexin and its transcripts in injured nervous system: a comparison of central and peripheral tissues. Neuroscience. 1998;82:1039–1052. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00271-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chard MD, Calvin J, Price CP, Cawston TE, Hazleman BL. Serum alpha 1 antichymotrypsin concentration as a marker of disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1988;47:665–671. doi: 10.1136/ard.47.8.665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chertov O, Biragyn A, Kwak LW, Simpson JT, Boronina T, Hoang VM, Prieto DA, Conrads TP, Veenstra TD, Fisher RJ. Organic solvent extraction of proteins and peptides from serum as an effective sample preparation for detection and identification of biomarkers by mass spectrometry. Proteomics. 2004;4:1195–1203. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200300677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chou R, Huffman LH, American Pain S, American College of P Medications for acute and chronic low back pain: a review of the evidence for an American Pain Society/American College of Physicians clinical practice guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:505–514. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-7-200710020-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cicardi M, Zingale L, Zanichelli A, Pappalardo E, Cicardi B. C1 inhibitor: molecular and clinical aspects. Springer seminars in immunopathology. 2005;27:286–298. doi: 10.1007/s00281-005-0001-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Conti A, Ricchiuto P, Iannaccone S, Sferrazza B, Cattaneo A, Bachi A, Reggiani A, Beltramo M, Alessio M. Pigment epithelium-derived factor is differentially expressed in peripheral neuropathies. Proteomics. 2005;5:4558–4567. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200402088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Corti A, Ferrari R, Ceconi C. Chromogranin A and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF) in chronic heart failure. Advances in experimental medicine and biology. 2000;482:351–359. doi: 10.1007/0-306-46837-9_28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cousins SL, Dai W, Stephenson FA. APLP1 and APLP2, members of the APP family of proteins, behave similarly to APP in that they associate with NMDA receptors and enhance NMDA receptor surface expression. J Neurochem. 2015;133:879–885. doi: 10.1111/jnc.13063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cresswell P, Ackerman AL, Giodini A, Peaper DR, Wearsch PA. Mechanisms of MHC class I-restricted antigen processing and cross-presentation. Immunol Rev. 2005;207:145–157. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2005.00316.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cresswell P, Springer T, Strominger JL, Turner MJ, Grey HM, Kubo RT. Immunological identity of the small subunit of HL-A antigens and beta2-microglobulin and its turnover on the cell membrane. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1974;71:2123–2127. doi: 10.1073/pnas.71.5.2123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Daveau M, Christian D, Julen N, Hiron M, Arnaud P, Lebreton JP. The synthesis of human alpha-2-HS glycoprotein is down-regulated by cytokines in hepatoma HepG2 cells. FEBS Lett. 1988;241:191–194. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(88)81059-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Davidsson P, Westman-Brinkmalm A, Nilsson CL, Lindbjer M, Paulson L, Andreasen N, Sjogren M, Blennow K. Proteome analysis of cerebrospinal fluid proteins in Alzheimer patients. Neuroreport. 2002;13:611–615. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200204160-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Demetriou M, Binkert C, Sukhu B, Tenenbaum HC, Dennis JW. Fetuin/alpha2-HS glycoprotein is a transforming growth factor-beta type II receptor mimic and cytokine antagonist. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:12755–12761. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.22.12755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.di Comite G, Marinosci A, Di Matteo P, Manfredi A, Rovere-Querini P, Baldissera E, Aiello P, Corti A, Sabbadini MG. Neuroendocrine modulation induced by selective blockade of TNF-alpha in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1069:428–437. doi: 10.1196/annals.1351.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dupuy A, Lindberg I, Zhou Y, Akil H, Lazure C, Chretien M, Seidah NG, Day R. Processing of prodynorphin by the prohormone convertase PC1 results in high molecular weight intermediate forms. Cleavage at a single arginine residue. FEBS Lett. 1994;337:60–65. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)80630-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Duranton J, Adam C, Bieth JG. Kinetic mechanism of the inhibition of cathepsin G by alpha 1-antichymotrypsin and alpha 1-proteinase inhibitor. Biochemistry. 1998;37:11239–11245. doi: 10.1021/bi980223q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Echeverry S, Shi XQ, Rivest S, Zhang J. Peripheral nerve injury alters blood-spinal cord barrier functional and molecular integrity through a selective inflammatory pathway. J Neurosci. 2011;31:10819–10828. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1642-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eisenach JC, Thomas JA, Rauck RL, Curry R, Li X. Cystatin C in cerebrospinal fluid is not a diagnostic test for pain in humans. Pain. 2004;107:207–212. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2003.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Elg SA, Mayer AR, Carson LF, Twiggs LB, Hill RB, Ramakrishnan S. Alpha-1 acid glycoprotein is an immunosuppressive factor found in ascites from ovaria carcinoma. Cancer. 1997;80:1448–1456. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Evangelopoulos AA, Vallianou NG, Bountziouka V, Katsagoni C, Bathrellou E, Vogiatzakis ED, Bonou MS, Barbetseas J, Avgerinos PC, Panagiotakos DB. Association between serum cystatin C, monocytes and other inflammatory markers. Intern Med J. 2012;42:517–522. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2011.02500.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fairbank JC, Pynsent PB. The Oswestry Disability Index. Spine. 25:2940–2952. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200011150-00017. discussion 2952,2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Foronjy RF, Mirochnitchenko O, Propokenko O, Lemaitre V, Jia Y, Inouye M, Okada Y, D’Armiento JM. Superoxide dismutase expression attenuates cigarette smoke- or elastase-generated emphysema in mice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;173:623–631. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200506-850OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Freemont AJ, Peacock TE, Goupille P, Hoyland JA, O’Brien J, Jayson MI. Nerve ingrowth into diseased intervertebral disc in chronic back pain. Lancet. 1997;350:178–181. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(97)02135-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fricker LD, McKinzie AA, Sun J, Curran E, Qian Y, Yan L, Patterson SD, Courchesne PL, Richards B, Levin N, Mzhavia N, Devi LA, Douglass J. Identification and characterization of proSAAS, a granin-like neuroendocrine peptide precursor that inhibits prohormone processing. J Neurosci. 2000;20:639–648. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-02-00639.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fukusen N, Kato Y, Kido H, Katunuma N. Kinetic studies on the inhibitions of mast cell chymase by natural serine protease inhibitors: indications for potential biological functions of these inhibitors. Biochem Med Metab Biol. 1987;38:165–169. doi: 10.1016/0885-4505(87)90076-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gao F, Koenitzer JR, Tobolewski JM, Jiang D, Liang J, Noble PW, Oury TD. Extracellular superoxide dismutase inhibits inflammation by preventing oxidative fragmentation of hyaluronan. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:6058–6066. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709273200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gillen C, Gleichmann M, Spreyer P, Muller HW. Differentially expressed genes after peripheral nerve injury. J Neurosci Res. 1995;42:159–171. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490420203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Glazner GW, Morrison AE, Ishii DN. Elevated insulin-like growth factor (IGF) gene expression in sciatic nerves during IGF-supported nerve regeneration. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1994;25:265–272. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(94)90162-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gronblad M, Habtemariam A, Virri J, Seitsalo S, Vanharanta H, Guyer RD. Complement membrane attack complexes in pathologic disc tissues. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2003;28:114–118. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200301150-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Guillemin GJ, Brew BJ. Microglia, macrophages, perivascular macrophages, and pericytes: a review of function and identification. J Leukoc Biol. 2004;75:388–397. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0303114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Guo SL, Han CT, Jung JL, Chen WJ, Mei JJ, Lee HC, Cheng YC. Cystatin C in cerebrospinal fluid is upregulated in elderly patients with chronic osteoarthritis pain and modulated through matrix metalloproteinase 9-specific pathway. Clin J Pain. 2014;30:331–339. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e31829ca60b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Helle KB. The granin family of uniquely acidic proteins of the diffuse neuroendocrine system: comparative and functional aspects. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc. 2004;79:769–794. doi: 10.1017/s146479310400644x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hillenbrand R, Molthagen M, Montag D, Schachner M. The close homologue of the neural adhesion molecule L1 (CHL1): patterns of expression and promotion of neurite outgrowth by heterophilic interactions. Eur J Neurosci. 1999;11:813–826. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00496.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hiraiwa M, Campana WM, Mizisin AP, Mohiuddin L, O’Brien JS. Prosaposin: a myelinotrophic protein that promotes expression of myelin constituents and is secreted after nerve injury. Glia. 1999;26:353–360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Horton WC, Daftari TK. Which disc as visualized by magnetic resonance imaging is actually a source of pain? A correlation between magnetic resonance imaging and discography. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1992;17:S164–171. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199206001-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hou G, Lu H, Chen M, Yao H, Zhao H. Oxidative stress participates in age-related changes in rat lumbar intervertebral discs. Archives of gerontology and geriatrics. 2014;59:665–669. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2014.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Inoue G, Ohtori S, Aoki Y, Ozawa T, Doya H, Saito T, Ito T, Akazawa T, Moriya H, Takahashi K. Exposure of the nucleus pulposus to the outside of the anulus fibrosus induces nerve injury and regeneration of the afferent fibers innervating the lumbar intervertebral discs in rats. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2006;31:1433–1438. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000219946.25103.db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jensen MC, Brant-Zawadzki MN, Obuchowski N, Modic MT, Malkasian D, Ross JS. Magnetic resonance imaging of the lumbar spine in people without back pain. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:69–73. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199407143310201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jimenez CR, Stam FJ, Li KW, Gouwenberg Y, Hornshaw MP, De Winter F, Verhaagen J, Smit AB. Proteomics of the injured rat sciatic nerve reveals protein expression dynamics during regeneration. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2005;4:120–132. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M400076-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kasen S, Ouellette R, Cohen P. Mainstreaming and postsecondary educational and employment status of a rubella cohort. Am Ann Deaf. 1990;135:22–26. doi: 10.1353/aad.2012.0408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kaysen GA, Dubin JA, Muller HG, Rosales L, Levin NW, Mitch WE. Inflammation and reduced albumin synthesis associated with stable decline in serum albumin in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2004;65:1408–1415. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00520.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kroenke K, Krebs EE, Bair MJ. Pharmacotherapy of chronic pain: a synthesis of recommendations from systematic reviews. General hospital psychiatry. 2009;31:206–219. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2008.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Latremoliere A, Woolf CJ. Central sensitization: a generator of pain hypersensitivity by central neural plasticity. J Pain. 2009;10:895–926. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2009.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Li W, Zhu S, Li J, Huang Y, Zhou R, Fan X, Yang H, Gong X, Eissa NT, Jahnen-Dechent W, Wang P, Tracey KJ, Sama AE, Wang H. A hepatic protein, fetuin-A, occupies a protective role in lethal systemic inflammation. PLoS One. 2011;6:e16945. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lim TK, Shi XQ, Martin HC, Huang H, Luheshi G, Rivest S, Zhang J. Blood-nerve barrier dysfunction contributes to the generation of neuropathic pain and allows targeting of injured nerves for pain relief. Pain. 2014;155:954–967. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2014.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lind AL, Emami Khoonsari P, Sjodin M, Katila L, Wetterhall M, Gordh T, Kultima K. Spinal Cord Stimulation Alters Protein Levels in the Cerebrospinal Fluid of Neuropathic Pain Patients: A Proteomic Mass Spectrometric Analysis. Neuromodulation. 2016;19:549–562. doi: 10.1111/ner.12473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lind AL, Wu D, Freyhult E, Bodolea C, Ekegren T, Larsson A, Gustafsson MG, Katila L, Bergquist J, Gordh T, Landegren U, Kamali-Moghaddam M. A Multiplex Protein Panel Applied to Cerebrospinal Fluid Reveals Three New Biomarker Candidates in ALS but None in Neuropathic Pain Patients. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0149821. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0149821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lindh C, Thornwall M, Hansen AC, Post C, Gordh T, Ordeberg G, Nyberg F. Neuropeptide-converting enzymes in cerebrospinal fluid: activities increased in pain from herniated lumbar dis, but not from coxarthrosis. Acta Orthop Scand. 1996;67:189–192. doi: 10.3109/17453679608994670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Liu XD, Zeng BF, Xu JG, Zhu HB, Xia QC. Proteomic analysis of the cerebrospinal fluid of patients with lumbar disk herniation. Proteomics. 2006;6:1019–1028. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200500247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Luchting B, Rachinger-Adam B, Heyn J, Hinske LC, Kreth S, Azad SC. Anti-inflammatory T-cell shift in neuropathic pain. J Neuroinflammation. 2015;12:12. doi: 10.1186/s12974-014-0225-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Luchting B, Rachinger-Adam B, Zeitler J, Egenberger L, Mohnle P, Kreth S, Azad SC. Disrupted TH17/Treg balance in patients with chronic low back pain. PLoS One. 2014;9:e104883. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0104883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Madore N, Camborieux L, Bertrand N, Swerts JP. Regulation of hemopexin synthesis in degenerating and regenerating rat sciatic nerve. J Neurochem. 1999;72:708–715. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0720708.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]