Abstract

Intraosseous arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) have been associated with distortion, hypertrophy, osteolytic skeletal changes, bleeding, leg length discrepancy, and pathologic fracture. Computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging is helpful in the evaluation of the extent and depth of intraosseous AVMs and associated soft-tissue AVMs. Treatment approaches can differ, depending on the angiographic classification. Embolotherapy with ethanol, coils, or n-butyl cyanoacrylate is the primary treatment for symptomatic intraosseous AVMs, and the goal of treatment is symptom improvement with few complications.

Keywords: intraosseous AVM, embolization, embolotherapy, interventional radiology

Objectives : Upon completion of this article, the reader will be able to discuss treatment options for different types of AVMs and explain why intraosseous AVMs, although rare, should be treated first, before all others.

Accreditation : This activity has been planned and implemented in accordance with the Essential Areas and Policies of the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME) through the joint providership of Tufts University School of Medicine (TUSM) and Thieme Medical Publishers, New York. TUSM is accredited by the ACCME to provide continuing medical education for physicians.

Credit : Tufts University School of Medicine designates this journal-based CME activity for a maximum of 1 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit ™. Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity.

Around 18% of extremity arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) are associated with intraosseous AVMs, and multiple bone involvement is observed in 36% of intraosseous AVMs. More than 80% of intraosseous AVMs have combined soft-tissue AVMs, but in pure intraosseous AVMs, enlarged vessels in the soft tissue are dilated, feeding arteries or draining veins of the pure intraosseous AVMs. 1 Intraosseous AVMs of the extremity have been associated with distortion, hypertrophy, osteolytic skeletal changes, and additional clinical manifestations of leg length discrepancy and pathologic fracture. 1 2 3

Because of AVMs' biologic nature and their high-flow shunting, they have a more aggressive behavior and are more often associated with life- or limb-threatening complications than other types of congenital vascular malformation. Therefore, early aggressive treatment of AVMs is recommended. Inappropriate treatment strategy (e.g., partial excision, ligation, or endovascular occlusion of the feeding artery) only stimulate the AVM lesion to a proliferative state, resulting in massive growth with uncontrollable complications. Surgical resection of AVM lesions carries the risk of massive intraoperative hemorrhage, incomplete removal of the AVM nidus, surrounding organ or tissue injury, and high recurrence rates. 4 5

Endovascular treatment using a variety of embolic and sclerosing agents has become an accepted therapeutic option for the management of AVMs, and endovascular treatment of AVMs has advanced rapidly in the past two decades, but there is no widely accepted consensus about endovascular treatment of intraosseous AVMs.

In this article, clinical presentation, imaging findings, and endovascular treatment of intraosseous AVMs will be described.

Clinical Presentation

The common clinical manifestations of intraosseous AVMs of the extremity are pain, pulsating mass, bone overgrowth at the lesion site, osteolytic bone lesion, skin ulceration, and enlargement of the draining vein, which are not very different from those of soft-tissue AVMs of the extremity, except for osteolytic bone lesion and/or bone overgrowth. 1 2 3 Without careful evaluation of the length of both extremities and/or the imaging findings of simple radiography, computed tomography (CT), or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), intraosseous AVMs can be missed. In the head and neck, the most common site of bone involvement of AVMs is the mandible and maxilla, and intraosseous maxillo-mandible AVMs can cause life-threatening gingival bleeding, swelling of the soft tissues, and cosmetic deformity. 6 7 8

Imaging Findings

Simple Radiography

Simple radiographic findings of intraosseous AVMs include 1 multiple smooth osteolytic or lucent serpiginous lesions involving the cortex and medulla; 2 large osteolytic lesion at the medulla without cortical expansion, although the osteolytic lesions may extend to the cortical margin; 3 and less dramatic periosteal reaction ( Figs. 1 and 2 ). 2

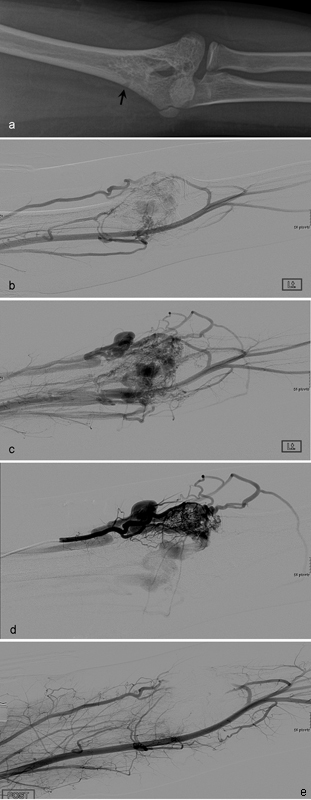

Fig. 1.

A 21-year-old man with intraosseous arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) at the distal tibia. ( a ) Simple radiography shows large osteolytic lesion in the medulla without cortical expansion (arrows). ( b ) Oblique angiography shows intraosseous AVMs at the distal tibia (arrows).

Fig. 2.

A 12-year-old boy with type III intraosseous arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) at the distal humerus. ( a ) Radiography demonstrates a lucent serpiginous lesion involving the cortex and medulla of the distal humerus (arrow). Pretreatment angiographies in arterial ( b ) and venous ( c ) phases show type III intraosseous AVMs at the distal humerus. ( d ) Selective angiography shows more details of type III intraosseous AVMs. ( e ) Angiography after transarterial injection of 30 mL of absolute ethanol shows complete obliteration of intraosseous AVMs.

Computed Tomography

CT with early arterial enhancement (CT angiography) and three-dimensional reconstruction images are quite helpful for diagnosis, follow-up, and planning of treatment. Current technique with three-dimensional reconstruction provides information about extension of the soft-tissue AVM lesion, feeding artery, exact shunting points, draining vein, and involvement of the bone. Typical CT finding of intraosseous AVMs is contrast-enhancing multiple small osteolytic lesions or a single large cavitary lesion in the medulla with or without cortical destruction. For evaluation of the cortical changes by AVMs, CT is better than MRI ( Figs. 3 and 4 ). However, its use is limited for pediatric patients or pregnant women because of radiation hazard.

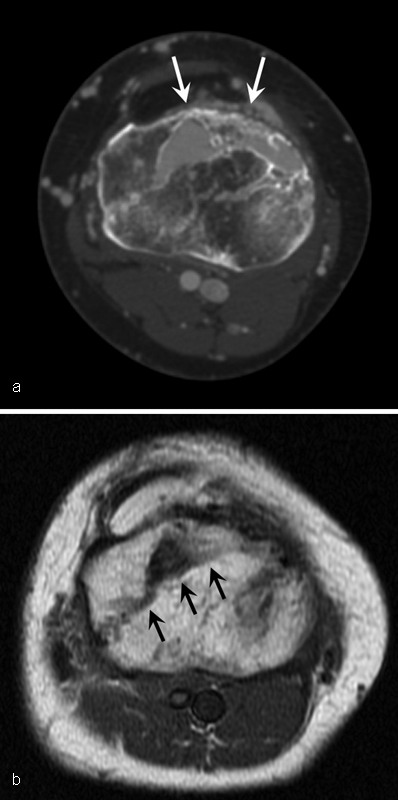

Fig. 3.

A 46-year-old woman with intraosseous arteriovenous malformations at the proximal tibia. ( a ) Axial CT shows multiple cortical defect and osteolytic lesion (arrows) with contrast enhancement at the proximal tibia. ( b ) Axial T1-weighted MR image shows signal voiding lesion (arrows) at the proximal tibia.

Fig. 4.

A 15-year-old girl with type II intraosseous arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) of the mandible. ( a ) Axial CT shows contrast-enhanced osteolytic lesion (arrows) with cortical erosion of the mandible. ( b ) Axial fat-suppressed gradient-echo MR image shows high signal lesion (arrows) at the mandible. Pretreatment lateral angiographies in arterial ( c ) and venous ( d ) phases show type II intraosseous AVMs (arrows). ( e ) Embolotherapy was performed with 10 mL of absolute ethanol through a direct-punctured needle (arrow). ( f ) Completion angiography shows complete obliteration of intraosseous AVMs. ( g ) Follow-up axial CT image 4 years later shows no residual intraosseous AVMs.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

MRI can determine and distinguish between high-flow and low-flow malformations. Further, various imaging sequences make it easy to determine relationships to adjacent anatomic structures such as organs, muscles, nerves, and so on. The high temporal resolution of time-resolved MR angiography enables arterial, venous, and nidus localization. Intraosseous AVMs typically demonstrate signal voids in the cortex or medulla on most sequences ( Fig. 3 ). These flow voids are felt to be predominantly due to time-of-flight phenomena with turbulence-related rephasing also contributing to signal loss. An additional feature to differentiate high-flow lesions from low-flow lesions is the presence of enlarged feeding arteries and dilated draining veins. Gradient echo sequences show AVMs as bright, signal, serpiginous, and vascular structures. 9

Angiography

For the diagnosis of AVMs and to determine treatment strategy, angiography is the most accurate diagnostic option. In addition to the primary AVM lesion, it can provide information about secondary changes (e.g., enlargement, tortuosity) of the artery and veins around the AVM lesion. In particular, it provides hemodynamic information about the AVM lesion that is critical to establish a treatment plan.

Angiographic classification of AVMs was proposed to classify the nidus AVMs in the body and extremity by Cho et al. 10 This classification is helpful in predicting the outcome of endovascular treatment of extremity AVMs. 11 The lesions were classified into three types: Type I (arteriovenous fistula), Type II (arteriolovenous fistulae), and Type IIIa and b (arteriolovenulous fistulae). Type I (arteriovenous fistulae) referred to, at most, three arteries shunted to a single draining vein. Type II (arteriolovenous fistulae) indicated multiple arterioles shunted into a single draining vein. Type III AVMs (arteriolovenulous fistulae) had multiple shunts between the arterioles and venules. All three types of lesion have radiologic findings of the nidus, representing the primitive reticular network of minute dysplastic vessels that failed to mature into capillary vessels. 12 Type II angiography shows multiple arterioles shunt to a dominant single venous component, and CT shows a long, segmental, enhancing, osteolytic lesion or single large, enhancing, cavitary lesion in the medulla of the bone ( Fig. 5 ). Type III angiography shows multiple shunts between arterioles and venules, and CT shows multiple small, enhancing, osteolytic lesions in the cortex and/or medulla of the bone ( Fig. 6 ). Type I AVM is quite rare and occurs in less than 1% of extremity and body. 11 Until now, we did not have a chance to see Type I intraosseous AVMs. By angiographic classification, a treatment approach and method can be determined.

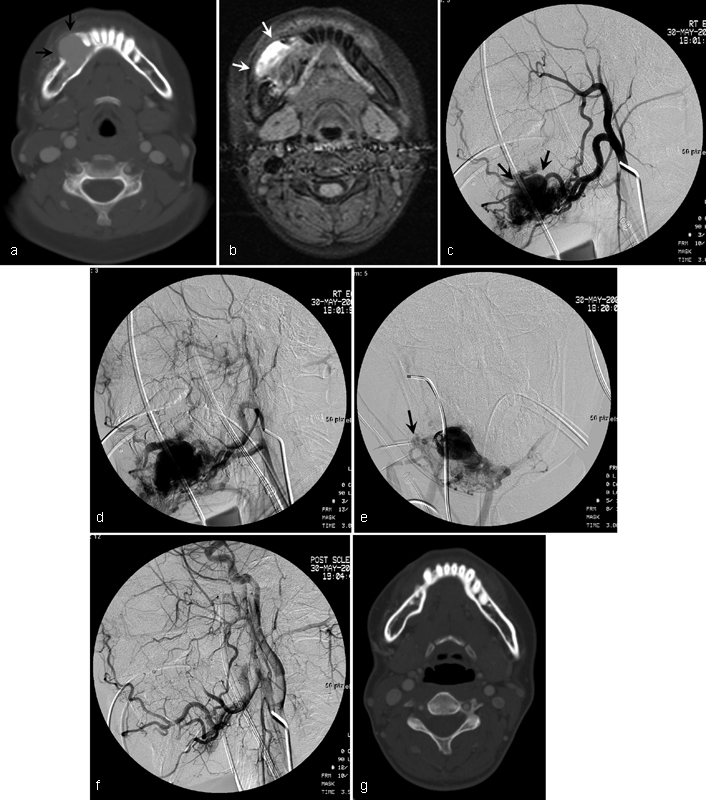

Fig. 5.

A 32-year-old woman with type II intraosseous arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) of the proximal ulna. ( a ) Axial CT shows contrast-enhanced osteolytic lesion (arrow) in the medulla of the ulna. ( b ) Angiography shows AVMs at the forearm. ( c ) Selective angiography shows the feeding artery (black arrow) of AVMs and intraosseous type II AVMs (white arrows) at the proximal ulna.

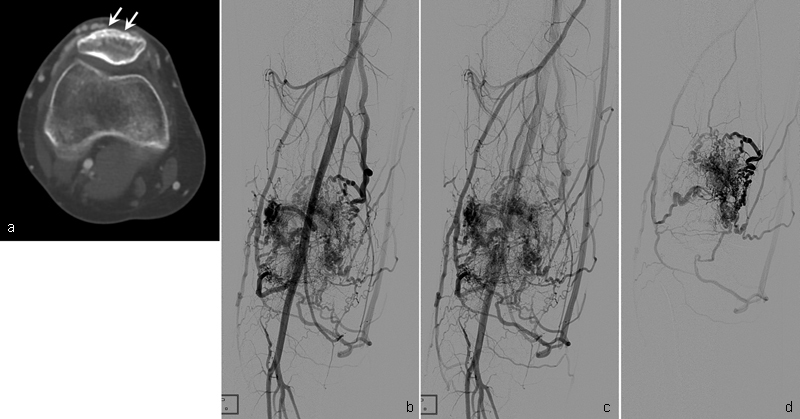

Fig. 6.

A 21-year-old woman with type III intraosseous arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) at the patella. ( a ) Axial CT shows multiple small enhancing osteolytic lesions (arrows) in the cortex of the patella. Angiography in early arterial ( b ) and late arterial ( c ) phases show type III intraosseous AVMs at the patella. ( d ) Selective angiography shows more details of type III intraosseous AVMs.

Endovascular Treatment

Embolotherapy using ethanol, coils, and/or NBCA (n-butyl cyanoacrylate) has been established as an essential therapeutic tool for the management of intraosseous AVMs. According to the angiographic type of intraosseous AVMs, embolic agents, treatment approach, and treatment method can differ, and when intraosseous AVMs are confirmed by imaging study, we should try to treat those areas first rather than the soft-tissue AVMs surrounding the intraosseous AVMs, because soft-tissue AVMs can be the dilated feeders or dilated draining veins of the intraosseous AVMs.

Type II Intraosseous AVM

The main target of Type II intraosseous AVMs is the large venous component of the nidus in the medulla. Transarterial embolization is often not effective for this type of AVM and the mainstay therapeutic approach is transvenous or direct puncture. When there is cortical erosion or thinning, direct puncture can be performed with a needle to access the malformation, and then embolic agents can be used ( Fig. 4 ). When there is no cortical erosion or thinning, direct puncture is quite difficult because of the thick cortex of the bone. In this situation, transvenous approach with a catheter through the vein of existing bone can be performed to access the malformation, and then embolic agents can be used ( Fig. 7 ). The most commonly used embolic agents in the literature are ethanol, coils, NBCA, and polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA), or a combination of these embolic agents. 1 8 13 14 In our institution, coils with ethanol or ethanol only has been used in most cases. When there is a high rate of blood flow in the intraosseous AVM, the use of only an ethanol injection is not sufficient to achieve complete thrombosis. A much higher chance of success can be anticipated by placing a few coils first and then injecting ethanol and, finally, occluding the AVM with coils ( Fig. 7 ). Conceptually, these coils decrease blood flow and increase turbulence in the nidus so that a clot may form and obliterate the AVM. In case reports and small series of Type II intraosseous AVMs, high clinical success has been reported by using coils only, NBCA, and PMMA, 8 13 14 but in terms of AVM treatment, permanence is a significant issue. When using ethanol, cures at long-term follow-up have been documented by several authors. 1 10 11 15 16

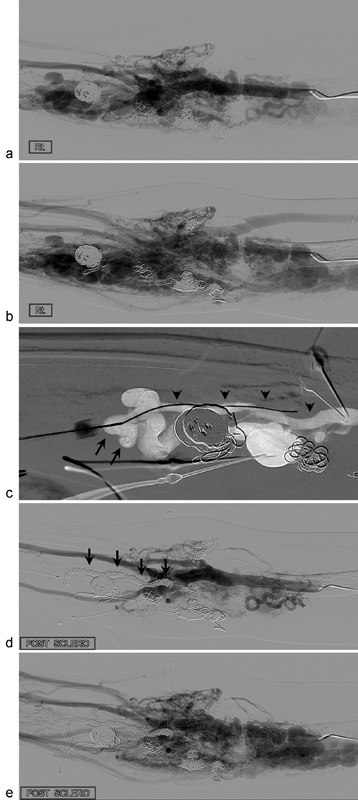

Fig. 7.

A 24-year-old woman with type II intraosseous arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) at the forearm and upper arm. She underwent four sessions of embolotherapy in the past 3 years. Pretreatment angiographies in arterial ( a ) and venous ( b ) phases show AVMs at the forearm and upper arm. ( c ) The draining vein (arrows) of the intraosseous AVMs (arrow heads) was punctured with a 21-gauge needle and a microwire was inserted into the intraosseous AVMs. After insertion of a microcatheter in the intraosseous AVMs, embolotherapy was performed with multiple microcoils and 20 mL of absolute ethanol. Posttreatment angiography in arterial ( d ) and venous ( e ) phases shows complete obliteration of the forearm AVMs. Note multiple coils (arrows) in the medulla of the proximal radius. Most dilated vessels of Fig. b ) in the forearm are the dilated draining veins of intraosseous type II AVMs.

Type III Intraosseous AVMs

For Type III intraosseous AVMs, the mainstay therapeutic approach is transarterial or direct puncture. We prefer the transarterial approach, provided there are no obstacles in terms of access and safe embolization ( Fig. 2 ), but when superselection of the feeding arteries of AVMs is difficult or when there is a high risk of skin necrosis with intra-arterial embolic agent injection, direct puncture can be performed with a needle to access the malformation through the cortical defect or thinning, and then embolic agents can be used ( Fig. 8 ). Blood pressure cuff or occlusion balloon may be helpful in slowing down the vascular flow to allow more contact time for embolic agents to work within the malformations. Embolization through the transvenous approach is not recommended for Type III intraosseous AVMs because embolic agents introduced by a transvenous approach will not reach shunts but rather block venous drainage, which results in hypertension in shunts and aggravation of AVMs. In our institution, pure or diluted ethanol has been used in most cases of Type III intraosseous AVMs by transarterial approach or direct puncture, 1 but there are quite rare case reports of using other embolic agents for this type of AVM. 17

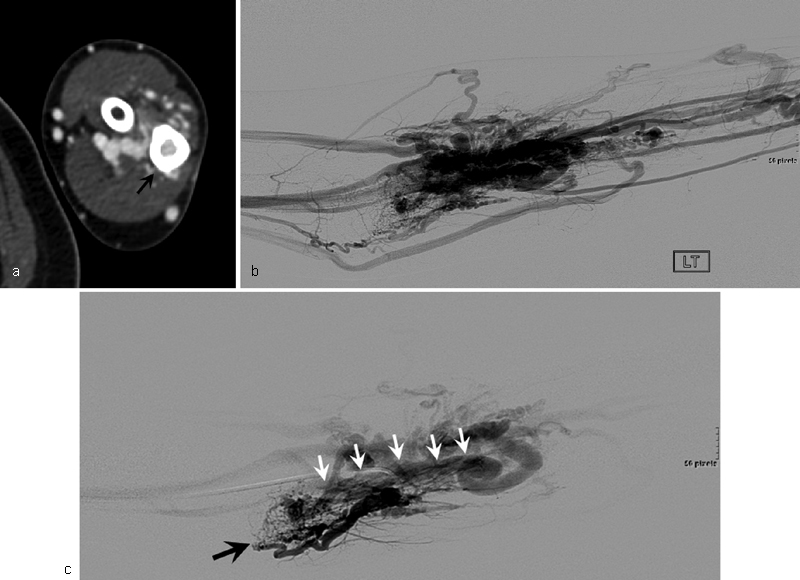

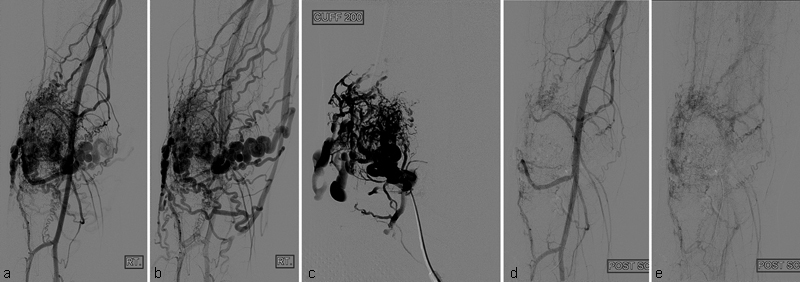

Fig. 8.

A 15-year-old boy with type III intraosseous arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) at the patella. Pretreatment angiographies in arterial ( a ) and venous ( b ) phases show type III intraosseous AVMs at the patella. ( c ) Angiography after direct puncture of the intraosseous AVMs with a needle shows more details of type III intraosseous AVMs. During angiography, BP cuff at the thigh was inflated to 200 mm Hg to slow down the blood flow. Embolotherapy was performed with 10 mL of absolute ethanol under BP cuff inflation. Completion angiographies in arterial ( d ) and venous ( e ) phases show markedly reduced intraosseous AVMs.

In one study, ethanol embolotherapy of intraosseous AVMs of the extremity was effective in 82% of patients with an 18% cure rate, and reossification of the osteolytic lesion after successful treatment was expected on long-term follow-up. However, ethanol injection is extremely painful and should be used in general anesthesia. Skin necrosis and peripheral nerve injury are common complications, but skin graft is not required, and nerve function recovers within 2 months in most cases. 1 NBCA with or without coils is also an effective agent for treating intraosseous AVMs, especially Type II AVMs, but there is potential for infection and recurrence. 8 13

Conclusion

Intraosseous AVMs are rare, but they should be treated first because differentiation of the surrounding soft-tissue AVMs and enlarged draining veins is difficult. Depending on the type of AVM, treatment approaches can differ. Embolotherapy with ethanol, coils, or NBCA has the potential to eliminate or improve symptoms with an acceptable risk of complications.

References

- 1.Do Y S, Park K B, Park H S et al. Extremity arteriovenous malformations involving the bone: therapeutic outcomes of ethanol embolotherapy. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2010;21(06):807–816. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2010.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Savader S J, Savader B L, Otero R R. Intraosseous arteriovenous malformations mimicking malignant disease. Acta Radiol. 1988;29(01):109–114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boyd J B, Mulliken J B, Kaban L B, Upton J, III, Murray J E. Skeletal changes associated with vascular malformations. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1984;74(06):789–797. doi: 10.1097/00006534-198412000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Szilagyi D E, Smith R F, Elliott J P, Hageman J H. Congenital arteriovenous anomalies of the limbs. Arch Surg. 1976;111(04):423–429. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1976.01360220119020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Flye M W, Jordan B P, Schwartz M Z. Management of congenital arteriovenous malformations. Surgery. 1983;94(05):740–747. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beek F J, ten Broek F W, van Schaik J P, Mali W P. Transvenous embolisation of an arteriovenous malformation of the mandible via a femoral approach. Pediatr Radiol. 1997;27(11):855–857. doi: 10.1007/s002470050254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Siu W W, Weill A, Gariepy J L, Moret J, Marotta T. Arteriovenous malformation of the mandible: embolization and direct injection therapy. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2001;12(09):1095–1098. doi: 10.1016/s1051-0443(07)61597-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Churojana A, Khumtong R, Songsaeng D, Chongkolwatana C, Suthipongchai S. Life-threatening arteriovenous malformation of the maxillomandibular region and treatment outcomes. Interv Neuroradiol. 2012;18(01):49–59. doi: 10.1177/159101991201800107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mulligan P R, Prajapati H J, Martin L G, Patel T H.Vascular anomalies: classification, imaging characteristics and implications for interventional radiology treatment approaches Br J Radiol 201487(1035):2.0130392E7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cho S K, Do Y S, Shin S W et al. Arteriovenous malformations of the body and extremities: analysis of therapeutic outcomes and approaches according to a modified angiographic classification. J Endovasc Ther. 2006;13(04):527–538. doi: 10.1583/05-1769.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Park K B, Do Y S, Kim D I et al. Predictive factors for response of peripheral arteriovenous malformations to embolization therapy: analysis of clinical data and imaging findings. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2012;23(11):1478–1486. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2012.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee B B, Baumgartner I, Berlien H P et al. Consensus Document of the International Union of Angiology (IUA)-2013. Current concept on the management of arterio-venous management. Int Angiol. 2013;32(01):9–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fan X, Zhang Z, Zhang Cet al. Direct-puncture embolization of intraosseous arteriovenous malformation of jaws J Oral Maxillofac Surg 20026008890–896., discussion 896–897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ierardi A M, Mangini M, Vaghi M, Cazzulani A, Mattassi R, Carrafiello G. Occlusion of an intraosseous arteriovenous malformation with percutaneous injection of polymethylmethacrylate. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2011;34 02:S150–S153. doi: 10.1007/s00270-010-0001-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yakes W F. Endovascular management of high-flow arteriovenous malformations. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2004;21(01):49–58. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-831405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Do Y S, Yakes W F, Shin S W et al. Ethanol embolization of arteriovenous malformations: interim results. Radiology. 2005;235(02):674–682. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2352040449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Perrelli L, Cina G, Cotroneo A R, Falappa P, Nanni L. Treatment of intraosseous arteriovenous fistulas of the extremities. J Pediatr Surg. 1994;29(10):1380–1383. doi: 10.1016/0022-3468(94)90120-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]