Abstract

Background

Glutaric aciduria type II (GA II) is an autosomal recessive disorder affecting fatty acid and amino acid metabolism. The late-onset form of GA II disorder is almost exclusively associated with mutations in the electron transfer flavoprotein dehydrogenase (ETFDH) gene. Till now, the clinical features of late-onset GA II vary widely and pose a great challenge for diagnosis. The aim of the current study is to characterize the clinical phenotypes and genetic basis of a late-onset GAII patient.

Methods

In this study, we described the clinical and biochemical manifestations of a 23-year-old female Chinese patient with late-onset GA II, and performed genomic DNA-based PCR amplifications and sequence analysis of ETFDH gene of the whole pedigree. We also used in-silicon tools to analyze the mutation and evaluated the pathogenicity of the mutation according to the criteria proposed by American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG).

Results

The muscle biopsy of this patient revealed lipid storage myopathy. Blood biochemical test and urine organic acid analyses were consistent with GA II. Direct sequence analysis of the ETFDH gene (NM_004453) revealed compound heterozygous mutations: c.250G > A (p.A84T) on exon 3 and c.920C > G (p.S307C) on exon 8. Both mutations were classified as “pathogenic” according to ACMG criteria.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our study described the phenotype and genotype of a late-onset GA II patient, reiterating the importance of ETFDH gene screening in these patients.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12944-017-0576-5) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Glutaric aciduria type II (GA II), Electron transfer flavoprotein dehydrogenase (ETFDH), Autosomal recessive disorder

Background

Glutaric aciduria type II (GA II), also known as multiple Acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency (MADD), is a rare autosomal recessive disorder of fatty acid, amino acid and choline metabolism caused by a defect in the alpha or beta subunit of the mitochondrial electron transfer flavoprotein (ETFA, ETFB) protein or the electron transfer flavoprotein dehydrogenase (ETFDH) protein [1]. The clinical manifestation of GA II is heterogeneous, from severe neonatal form to mild late-onset form. Children with the severe form usually show a fatal course in the neonatal period. In the mild form, the age of onset and the symptoms are variable with intermittent episodes, challenging the clinical diagnosis [2]. These patients often present with fluctuating proximal muscle weakness or episodes of rhabdomyolysis. Other manifestations include sensory neuropathy, loss of tendon reflex, fatty liver, etc. [2]. Current clinical diagnosis is mainly based on tandem mass spectrometry findings of elevated plasma levels of short, medium, and long chain acylcarnitines. However, in late-onset patients, the elevation of acylcarnitine levels may be mild and atypical, or detectable only during an acute episode. Under these circumstances, genetic screening is the key to establish a definitive diagnosis.

It has long been well-known that the mild form of GAII has exceptionally good response to riboflavin supplementation, although its true mechanism remains to be clarified. Recent work also suggests that most late-onset GA II patients with good response to riboflavin have mutations in the ETFDH gene. The ETFDH gene is located at 4q32.1, with a total of 13 exons. It encodes the electron transfer flavoprotein: ubiqionone oxidoreductase (ETF: QO) [3]. As a component in mitochondrial respiratory chain, ETF: QO forms a short pathway with ETF to transfer electrons from mitochondrial flavoprotein dehydrogenases to the ubiquinone pool [4].

So far, more than 190 mutations in the ETFDH gene, including point mutations, nonsense mutations, insertions, deletions, splicing mutations, have been reported according to the Human Gene Mutation Database (HGMD) [5]. The genotype and phenotype in ETFDH-mutant GAII patients were previously reported to be correlated. Nonsense mutations leading to truncation or missense mutations affecting protein stability in both alleles were generally associated with a severe phenotype [6, 7]. However, according to a recent cohort study, in the late-onset mild forms, the correlation between genotype and phenotype (including age of onset, disease severity and response to treatment) is not well-established [8].

Herein, we describe the clinical presentation and course of a 23-year-old female who was diagnosed as late-onset GA II. We identified heterozygous mutations in ETFDH gene, including a p.A84T, located at the flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD)-binding domain and a p.S307C mutation, located within the ubiquinone (UQ)-binding domain of ETF dehydrogenase.

Methods

Case description

A 23-year-old female was admitted to our hospital because of exercise intolerance and general muscle weakness, especially in her lower limbs, for 3 months. The symptom of weakness in her neck and proximal limb muscles was noted to have aggravated in last 1 month. She had difficulty walking long distances, gradually she was unable to raise her head and arms away from bed. Two weeks before admission, she experienced intermittent vomiting and weight loss. Her prenatal history and early development were both normal, and her life history was unremarkable. Physical and neurological examinations showed neck and proximal muscle weakness (manual muscle testing (MMT) score 3/5 in neck, 2/5 in lower limbs, 4/5 in upper arm).

Besides her clinical history, other clinical details including blood biochemical examinations, blood acylcarnitine analysis, urine organic acids spectrum, muscle magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), CT scan of the abdomen, electrocardiogram (EEG) were also collected. Muscle biopsy was performed on the right biceps brachii and immunohistochemistry was performed using frozen sections. The patient was treated with riboflavin (120 mg/day) and carnitine supplements (1 g/day). Two days after riboflavin and carnitine treatment, she experienced a severe respiratory infection and developed rapidly progressive quadriparesis with acute respiratory failure. Despite immediate tracheal intubation, the patient succumbed to sudden heart arrest, which showed no response to chest compressions, intravenous adrenalin, or electric defibrillation.

The proband and her family were Han Chinese and lived in southern China. Her parents were not consanguineous and had no myopathic symptom. The younger brother of the proband, a 15-year old boy, had no history of neuromuscular disease. After written informed consent was obtained, blood samples of all family members were collected for genetic testing.

Mutation analysis

Genomic DNA-based PCR amplifications and sequence analysis of ETFDH gene of the whole pedigree was performed. Briefly, genomic DNA from peripheral blood leukocytes was isolated by proteinase K digestion and phenol/chloroform extraction. All of the exons and exon-intron boundaries of the ETFDH (GenBank NM_004453) gene were amplified by PCR with high fidelity KOD-plus polymerase from the hyperthermophilic Archaeon Thermococcus kodakaraensis KOD1 (TOYOBO, Japan) using primers listed in Table 1. The amplified PCR products were purified from agarose gel using QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and sequenced via the ABI3730XL sequencer (Applied Biosystems, CA, USA). Mutations were confirmed using control DNA from 200 unaffected Chinese individuals after obtaining a written informed consent.

Table 1.

Primers and amplicons for detecting ETFDH gene mutation

| Name | Sequence of primers | Amplicon(bp) |

|---|---|---|

| ETFDH-Exon1-F | CAATCGATCTCGAAGGGCACT | 659 bp |

| ETFDH--Exon1-R | TTAATTCTACCAACTGGGGCAAC | |

| ETFDH--Exon2-F | GTTAAGCCTGACATGAGCTAAATTG | 537 bp |

| ETFDH--Exon2-R | TAATTGTCGTGTTGTTGACTGAAGG | |

| ETFDH--Exon3-F | TGTGCAAAACACAGGGAGAATTTC | 512 bp |

| ETFDH--Exon3-R | AGCCTGGGCAACAAGAGTGAAA | |

| ETFDH--Exon4-F | AGGAGAAACACTTGAACCCAGGA | 502 bp |

| ETFDH--Exon4-R | AGTAAGTCCTTCAAATATCTGGGTCTC | |

| ETFDH--Exon5-F | TGAAAGTGTGACCATCAATGTAGCA | 437 bp |

| ETFDH--Exon5-R | TTGATGGGGGTACAACATGAGGA | |

| ETFDH--Exon6-F | CTTTCTCATCAAGGTTGTGGCAT | 405 bp |

| ETFDH--Exon6-R | TTGGAGAGATGGGGTTTCACTTT | |

| ETFDH--Exon7-F | CCATTGGCAGAGGAGCTGGAT | 683 bp |

| ETFDH--Exon7-R | CAACACTTGATACGACAATTCCAAC | |

| ETFDH--Exon8-F | CACCGTGCCCAGCCTTCTT | 477 bp |

| ETFDH--Exon8-R | AATGACACAGCAGCCATAAGCACT | |

| ETFDH--Exon9-F | CCAGAGCACAAGGATTTCTTAATATG | 693 bp |

| ETFDH--Exon9-R | ATTTGTTGTAGAGATGGGGTTTCG | |

| ETFDH—Exon10-F | ATTTTTCAGCCTTTCCCTACAGC | 551 bp |

| ETFDH—Exon10-R | GCCTACCAAAGTGCTGGGATTAC | |

| ETFDH—Exon11-F | CCAACCTGGGTGACAGAGCAA | 580 bp |

| ETFDH—Exon11-R | CTTCAACAATTTTGAGGGAAATGCT | |

| ETFDH—Exon12-F | TGAGGGCTAGTCATATTTCTTTGGT | 444 bp |

| ETFDH—Exon12-R | TTTCTAAGGAATGGAAGGAGATACAG | |

| ETFDH—Exon13-F | TGAGAGGATGACTGTGAATAAGGGA | 689 bp |

| ETFDH—Exon13-R | GAACTGAAGAGGTAGGAAGATGCTG |

Bioinformatic analysis

Two in silicon tools were used for the analysis of mutation pathogenicity. The machine learning method predicts variants according to Bayesian methods (PolyPhen2) [9], or mathematical operations (SIFT) [10]. Multiple sequence alignment was performed using ClustalX [11]. The X-ray crystal structure of pig ETF:QO (Protein Data Bank entry 2GMH, resolution 2.5 Å) [12] was used as the template to construct human wild type and S307C mutational ETFDH structure models. The sequence of human ETFDH was retrieved from UniProt (http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/Q16134). The 3D models of human ETFDH complexed with substrates (ubiquinone, FAD, and 4Fe4S) were generated using MODELLER (version 9.12) [13].

Results

Clinical information

Laboratory examinations revealed an elevated plasma creatine kinase (CK) level up to 26,997 IU/ml (normal 26-140 U/L). Other dramatically abnormal parameters included: alanine aminotransferase (ALT) 598 U/L (normal 9-50 U/L), aspartate aminotransferase (AST) 5029 U/L (normal 15-40 U/L), creatine kinase-MB (CKMB) 944 U/L (normal 0-23 U/L), myoglobin >3000 ng/mL (28-72.0 ng/mL), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) >4000 U/L (109-245 U/L).

Organic acid analysis of the urine sample showed a marked increase in a variety of dicarboxylic acids (Table 2), including glutarate, adipate, 2-hydroxyglutaric acid, 3-hydroxyglutaric acid, 2-hydroxy adipic acid, orotic acid, 4-hydroxy-phenyllactic acid, and ethylmalonic acid. The organic acid profile in urine was highly suggestive of GA II. Acylcarnitine analysis of blood sample was unremarkable. No elevation of short (C6), medium (C8, C10:1, C10) or long chain (C14:1, C14) acylcarnitines was observed.

Table 2.

GC / MS analysis of the organic acid of the urine sample

| No. | Test item | Results | Normal average | Normal min | Normal max | Results (Average) | Results (Max) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | glutarate | 105.21 | 1.9 | 0 | 4 | 55.37 | 26.3 |

| 2 | adipic acid | 58.55 | 3 | 0.5 | 5 | 19.52 | 11.71 |

| 3 | 2 - hydroxy glutaric acid | 143.58 | 2.3 | 0.6 | 5.9 | 62.42 | 24.34 |

| 4 | 2-hydroxy adipic acid | 43.54 | 1.2 | 0 | 2 | 36.28 | 21.77 |

| 5 | orotic acid | 35.2 | 0.3 | 0 | 1.5 | 117.33 | 23.12 |

| 6 | isovaleryl-glycine | 3.1 | 0.1 | 0 | 0.4 | 31.02 | 7.75 |

| 7 | 4-hydroxy phenyllactic acid | 255.05 | 1.8 | 0 | 7 | 141.7 | 36.44 |

| 8 | ethylmalonic acid | 10.03 | 0.9 | 0 | 5.2 | 11.15 | 1.62 |

| 9 | 4 - hydroxy benzene pyruvic acid | 4.09 | 0.2 | 0 | 0.9 | 20.46 | 4.54 |

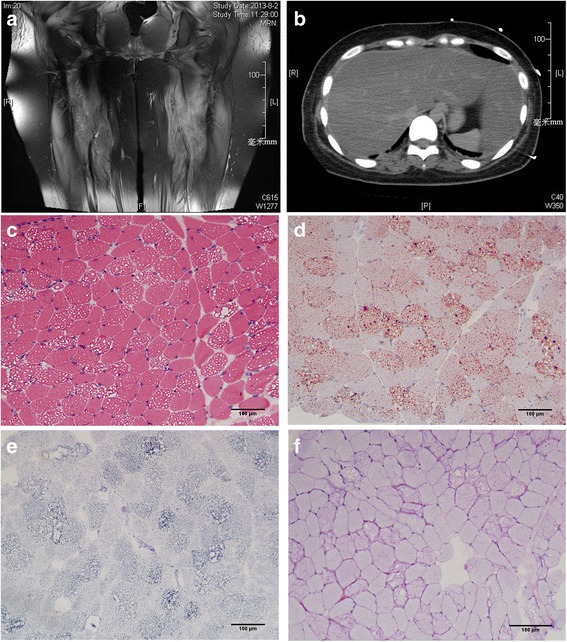

Muscle MRI of lower limbs showed high signal intensity areas in the bilateral lower limb muscles on T2-weighted MR imaging, indicating diffuse muscle injury (Fig. 1a). CT scans of the abdomen indicated severe lipid accumulation in the liver (fatty liver) as suggested by significantly lower density compared with that of the spleen (Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1.

Radiologic and histologic findings of the proband. a Diffuse muscle injury in the lower limbs of the proband as revealed by high signal intensity on T2-weighted MR imaging. b Significantly lower density of the liver compared with that of the spleen on abdominal CT scanning. c H&E staining showed vacuolar myopathy, with fine vacuoles found mainly in type I fibers. d The Oil Red O staining showed diffuse lipid droplets accumulation, predominantly in type I fibers. e NADH staining indicated disorganized myofibrillar network. f PAS staining did not show excessive glycogen content. (C ~ F) Original magnification ×200

Histochemical staining of muscle frozen sections revealed vacuolar myopathy, with numerous fine vacuoles found mainly in type 1 fibers (Fig. 1c). The Oil Red O stain showed diffuse lipid droplets accumulation, predominantly in type 1 fibers (Fig. 1d). Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH) staining indicated the myofibrillar network was disorganized in type 1 fibers, and no excessive glycogen content was observed on periodic acid-schiff (PAS) staining (Fig. 1f and g). The pathological findings were compatible with lipid storage myopathy. Histological findings of a control case were shown in Additional file 1: Figure S1.

Molecular studies

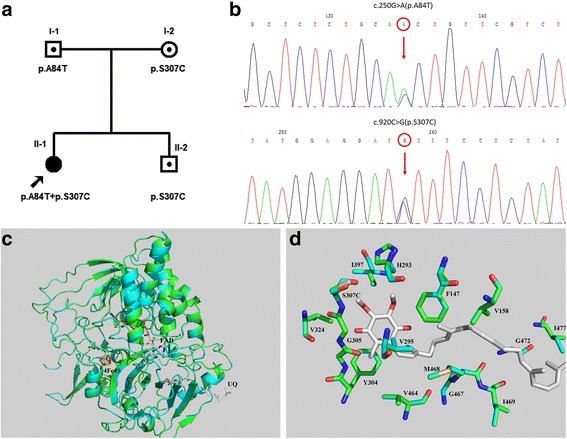

Direct sequencing of all 13 exons of ETFDH gene revealed compound heterozygous mutations in the proband: c.250G > A (p.A84T) on exon 3 and c.920C > G (p.S307C) on exon 8 (Fig. 2b). Her father carried a c.250G > A (p.A84T) on exon 3, while her mother carried a c.920C > G (p.S307C) on exon 8. Her younger brother, a 17-year old boy, inherited c.920C > G (p.S307C) from his mother. The missense mutation c.920C > G (p.S307C) was not identified in a screening of 200 control chromosomes in Chinese individuals. No mutation was identified in ETFA or ETFB gene.

Fig. 2.

Identification of the ETFDH gene mutations and the ETFDH protein structural analysis. a Pedigree of the family based on direct sequencing of the ETFDH gene. b Electropherogram of the proband. c.250G > A (p.A84T) mutation at exon 3 and c.920C > G (p.S307C) mutation at exon 8 of the ETFDH gene were identified. c The 3D models of human ETFDH structures. d The wild type and S307C mutational structures showed cyan and green cartoons. Oxygen atoms are shown in red and nitrogen atoms in blue. Carbon atoms of wild type, S307C mutation and ubiquinone are shown in cyan, green and white, respectively. The phosphorus atom of mutational Cys307 is shown in yellow-orange. Crucial residues in the binding site of ubiquinone are shown as stick and labeled. Figures were generated by PyMol

Bioinformatic and structural analysis

Both silicon tools, namely PolyPhen-2 and SIFT, supported that p.S307C of ETFDH was a deleterious mutation (Table 3). The human and pig ETFDH proteins share 95% sequence identity, which makes homology modeling very reasonable. The results showed a minimal difference between the wild type and mutant structures, even in the ubiquinone binding pocket for p.S307C mutation (Fig. 2d). It should be mentioned that, the structure of amino acid serine (S) was very close to cysteine (C). The only difference in the chemical structure was the Sulfur atom instead of the Oxygen atom.

Table 3.

In silicon prediction of deleterious effect for p.S307C of ETFDH

| Tool | Results | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| PolyPhen-2 | Probably damaging with a score of 1.000 | Deleterious |

| SIFT | Median information content (MIC): 2.96 | Low confidence of deleterious mutation with MIC above 3.25 |

Discussion

GA II is mainly caused by homozygous or compound heterozygous mutations in ETFA, ETFB, or ETFDH genes. Mutations in ETFA and ETFB are usually associated with the neonatal forms, whereas ETFDH mutations often present as late-onset forms. For the late-onset form, the clinical manifestation varies considerably. So far, most GA II patients were reported from East Asia, especially mainland China. A recent study reported the clinical features and ETFDH mutation spectrum of 90 unrelated patients pooled from two major centers in China. Several hot spots were described: c.250G > A (p.A84T), c.770A > G (p.Y257C) and c.1227A > C (p.L409F) with a frequency of 12.2%, 15.0% and 12.2% in Chinese, respectively [8].

According to American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG), the criterion for classification of pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants is weighted as very strong (PVS1), strong (PS1–4), moderate (PM1–6), or supporting (PP1–5) [5]. Several independent studies have consistently reported that the c.250G > A (p.A84T) mutation was the most common mutation in GAII patients from Southern China, as well as those from Taiwan, Hong Kong, Thailand and Singapore (PS1) [14, 15]. Consistently, the current proband and her father, both carrying the c.250G > A (p.A84T) mutation, lived in Zhejiang province, geographically classified as Southern China. The p.A84T mutation was previously reported to cause reduced ETFDH protein expression in vivo (PS3) [16]. The prevalence of p.A84T in GAII patients was significantly increased compared with the prevalence in East Asians (PS4) [15]. The p.A84T mutation itself was a mutational hot spot and located in a critical and well-established functional domain (FAD domain) (PM1). Thus, it was classified as “pathogenic” according to the criteria proposed by ACMG (3PS + 1 PM) [5].

In contrast, the c.920C > G (p.S307C) mutation was relatively new. The p.S307C mutation was previously reported and associated with GA II (PS1) [17, 18]. The p.S307C mutation was located in a critical and well-established functional domain (UQ-binding domain) (PM1) [18]. Furthermore, this variant was neither found in Exome Aggregation Consortium (ExAC) nor 1000 Genomes Project (PM2). Taking co-segregation into account in the pedigree, the p.S307C mutation was in trans with a pathogenic variant p.A84T (PM3). The deleterious effect was supported by multiple lines of computational evidence such as PolyPhen2 and SIFT (PP3). The phenotype of the patient is highly consistent with the phenotype caused by the ETHDH gene (PP4). Based on these findings, it should also be classified as “pathogenic” according to the criteria proposed by ACMG(1PS + 3 PM + 2PP) [5].

The c.920C > G (p.S307C) mutation was previously described in only two patients. Both patients were Han Chinese, whose age of onset were much older than our patient [17, 18]. The features of these three patients carrying the p.S307C mutation were summarized in Additional file 2: Table S1. One patient initially manifested as Bent spine syndrome. Both patients had limb and lip numbness, and EMG showed no sensory nerve action potential, suggesting severe sensory neuropathy besides muscle weakness [17, 18]. However, in the current case, progressive muscle weakness was the major symptom, while sensory nerve action potential was preserved. CT scan of the abdomen in our patient indicated severe lipid accumulation in the liver. Some GA II patients were previously reported to have fatty liver [19, 20]. In one case, liver lipid accumulation relieved after riboflavin supplementation [20]. Since the patient died unexpectedly, we were unable to see an effect of riboflavin supplementation on fatty liver.

The ETF:QO protein acts in conjunction with ETF to govern electron transport from several flavoprotein acyl-CoA dehydrogenases to the main respiratory chain in mitochondria [12]. Residues A84 and S307 are located in the flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD)-binding domain and the ubiquinone (UQ)-binding domain of ETF dehydrogenase, respectively. Both of the codons are highly evolutionarily conserved. Previous studies have suggested that A84T mutation could affect the interaction between FAD and ETF:QO, thus, could reduce the efficiency of electron transfer [21]. S307, together with Y304, G305 and G306, belong to the β-sheet 11, which wrap around the C5 methyl, O4 carbonyl, and C3 methoxy groups of UQ. In particular, the O4 atom of UQ makes hydrogen bonds to the backbone nitrogen of G306 and carbonyl oxygen of G305 [12]. Based on the structural studies, it is reasonable to assume that the p.S307C mutation, which is beside G306 and G305, might disturb the formation of the hydrogen bonds between UQ and G306/G305. Further in vivo studies are still needed to confirm the pathogenicity of S307C mutation.

Conclusion

In summary, we described the phenotype and genotype of a late-onset GA II patient. Clinicians should be alert to young patients with unexplained muscle weakness and high CK levels. ETFDH gene screening is necessary for establishing the diagnosis and genetic counseling if muscle biopsy showed lipid accumulation.

Additional files

Histological findings of a control case. (TIFF 16416 kb)

Summary of three GA II patients with compound heterozygous mutations including p.S307C. (DOCX 20 kb)

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Pu Xia (Fudan University) for critical reading of the manuscript. We acknowledge Dr. Wenhua Zhu (Department of Neurology, Huashan Hospital, Fudan University) for providing pictures of muscle pathology. We are deeply grateful to the family of the patient for their participation.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 81400834, 81500589, 81570799).

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Abbreviations

- ACMG

American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics

- ALT

Alanine aminotransferase

- AST

Aspartate aminotransferase

- CK

Creatine kinase

- CKMB

Creatine kinase-MB

- EEG

Electrocardiogram

- ETF

Electron transfer flavoprotein

- ETF:QO

Electron transfer flavoprotein: ubiqionone oxidoreductase

- ETFDH

Electron transfer flavoprotein dehydrogenase

- GA II

Glutaric aciduria type II

- HGMD

the Human Gene Mutation Database

- LDH

Lactate dehydrogenase

- MADD

Multiple Acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency

- MMT

Manual muscle testing

- MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging

- NADH

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide

- PAS

Periodic acid-schiff

Authors’ contributions

YX analyzed the patient data and drafted the manuscript. YZ contributed to the case report section and revised the manuscript. KQZ contributed to data interpretation and critical revision of the manuscript. LL coordinated the research. AK contributed to bioinformatic analysis. LYC carried out the molecular genetic study. YHW and ZQL designed the study, revised and prepared the final version of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the local ethics committee (Tongji Hospital of Tongji University). Written informed consent was obtained from each subject participating in the study after full explanation of the purpose and all procedures.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12944-017-0576-5) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Contributor Information

Yuhui Wang, Phone: 010-82801146, Email: yuhui_wang31@hotmail.com.

Zhiqiang Lu, Phone: 021-64041990, Email: lu_zhi_qiang@163.com.

References

- 1.Goodman SI, Binard RJ, Woontner MR, Frerman FE. Glutaric acidemia type II: gene structure and mutations of the electron transfer flavoprotein:ubiquinone oxidoreductase (ETF:QO) gene. Mol Genet Metab. 2002;77:86–90. doi: 10.1016/S1096-7192(02)00138-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yamada K, Kobayashi H, Bo R, Takahashi T, Purevsuren J, Hasegawa Y, Taketani T, Fukuda S, Ohkubo T, Yokota T, et al. Clinical, biochemical and molecular investigation of adult-onset glutaric acidemia type II: Characteristics in comparison with pediatric cases. Brain and Development. 2016;38:293–301. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2015.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Olsen RK, Olpin SE, Andresen BS, Miedzybrodzka ZH, Pourfarzam M, Merinero B, Frerman FE, Beresford MW, Dean JC, Cornelius N, et al. ETFDH mutations as a major cause of riboflavin-responsive multiple acyl-CoA dehydrogenation deficiency. Brain. 2007;130:2045–2054. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Watmough NJ, Frerman FE. The electron transfer flavoprotein: ubiquinone oxidoreductases. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1797;2010:1910–1916. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2010.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, Bick D, Das S, Gastier-Foster J, Grody WW, Hegde M, Lyon E, Spector E, et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. 2015;17:405–424. doi: 10.1038/gim.2015.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Olsen RK, Andresen BS, Christensen E, Bross P, Skovby F, Gregersen N. Clear relationship between ETF/ETFDH genotype and phenotype in patients with multiple acyl-CoA dehydrogenation deficiency. Hum Mutat. 2003;22:12–23. doi: 10.1002/humu.10226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Olsen RK, Pourfarzam M, Morris AA, Dias RC, Knudsen I, Andresen BS, Gregersen N, Olpin SE. Lipid-storage myopathy and respiratory insufficiency due to ETFQO mutations in a patient with late-onset multiple acyl-CoA dehydrogenation deficiency. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2004;27:671–678. doi: 10.1023/B:BOLI.0000042986.10291.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xi J, Wen B, Lin J, Zhu W, Luo S, Zhao C, Li D, Lin P, Lu J, Yan C. Clinical features and ETFDH mutation spectrum in a cohort of 90 Chinese patients with late-onset multiple acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2014;37:399–404. doi: 10.1007/s10545-013-9671-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adzhubei I, Jordan DM, Sunyaev SR. Predicting functional effect of human missense mutations using PolyPhen-2. Curr Protoc Hum Genet. 2013;Chapter 7(Unit7):20. doi: 10.1002/0471142905.hg0720s76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ng PC, Henikoff S. SIFT: Predicting amino acid changes that affect protein function. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3812–3814. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chenna R, Sugawara H, Koike T, Lopez R, Gibson TJ, Higgins DG, Thompson JD. Multiple sequence alignment with the Clustal series of programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3497–3500. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang J, Frerman FE, Kim JJ. Structure of electron transfer flavoprotein-ubiquinone oxidoreductase and electron transfer to the mitochondrial ubiquinone pool. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:16212–16217. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604567103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marti-Renom MA, Stuart AC, Fiser A, Sanchez R, Melo F, Sali A. Comparative protein structure modeling of genes and genomes. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 2000;29:291–325. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.29.1.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lan MY, Fu MH, Liu YF, Huang CC, Chang YY, Liu JS, Peng CH, Chen SS. High frequency of ETFDH c.250G>A mutation in Taiwanese patients with late-onset lipid storage myopathy. Clin Genet. 2010;78:565–569. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2010.01421.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang ZQ, Chen XJ, Murong SX, Wang N, Wu ZY. Molecular analysis of 51 unrelated pedigrees with late-onset multiple acyl-CoA dehydrogenation deficiency (MADD) in southern China confirmed the most common ETFDH mutation and high carrier frequency of c.250G>A. J Mol Med (Berl) 2011;89:569–576. doi: 10.1007/s00109-011-0725-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liang WC, Ohkuma A, Hayashi YK, Lopez LC, Hirano M, Nonaka I, Noguchi S, Chen LH, Jong YJ, Nishino I. ETFDH mutations, CoQ10 levels, and respiratory chain activities in patients with riboflavin-responsive multiple acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency. Neuromuscul Disord. 2009;19:212–216. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2009.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang Z, Hong D, Zhang W, Li W, Shi X, Zhao D, Yang X, Lv H, Yuan Y. Severe sensory neuropathy in patients with adult-onset multiple acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency. Neuromuscul Disord. 2016;26:170–175. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2015.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peng Y, Zhu M, Zheng J, Zhu Y, Li X, Wei C, Hong D. Bent spine syndrome as an initial manifestation of late-onset multiple acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency: a case report and literature review. BMC Neurol. 2015;15:114. doi: 10.1186/s12883-015-0380-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wolfe LA, He M, Vockley J, Payne N, Rhead W, Hoppel C, Spector E, Gernert K, Gibson KM. Novel ETF dehydrogenase mutations in a patient with mild glutaric aciduria type II and complex II-III deficiency in liver and muscle. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2010;33(Suppl 3):S481–S487. doi: 10.1007/s10545-010-9246-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wen B, Dai T, Li W, Zhao Y, Liu S, Zhang C, Li H, Wu J, Li D, Yan C. Riboflavin-responsive lipid-storage myopathy caused by ETFDH gene mutations. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2010;81:231–236. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2009.176404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Er TK, Chen CC, Liu YY, Chang HC, Chien YH, Chang JG, Hwang JK, Jong YJ. Computational analysis of a novel mutation in ETFDH gene highlights its long-range effects on the FAD-binding motif. BMC Struct Biol. 2011;11:43. doi: 10.1186/1472-6807-11-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Histological findings of a control case. (TIFF 16416 kb)

Summary of three GA II patients with compound heterozygous mutations including p.S307C. (DOCX 20 kb)

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.