Abstract

Introduction:

The minimally invasive treatment of small renal masses with cryoablation has become increasingly widespread during the past 15 years. Studies with long-term follow-up are beginning to emerge, showing good oncological control, however, tumors with a central and endophytic location seem to possess an increased risk of treatment failure. Such tumors are likely to be subjected to a high volume of blood giving thermal protection to the cancerous cells. Arterial clamping during freezing might reduce this effect but at the same time subject the kidney to ischemia. The aim of this study was to evaluate the effect of renal artery clamping during cryoablation in a porcine survival model.

Methods:

Ten Danish Landrace pigs (approximately 40 kg) underwent bilateral laparoscopic cryoablation with clamping of the right renal artery during freezing. The cryoablation consisted of a standard double-freeze cycle of 10-minute freeze followed by 8 minutes of thaw. Arterial clamping subjected the right kidney to 2 cycles of ischemia (10 minutes) with perfusion in between. After surgery, the animals were housed for 14 days prior to computed tomography perfusions scans, radioisotope renography, and bilateral nephrectomy.

Results:

No perioperative or postoperative complications were experienced. Mean differential renal function was 44% (95% confidence interval: 42-46) in the clamped right kidney group and 56% (95% confidence interval: 54-58) in the nonclamped left kidney group, P < .05. The ±5% technical inaccuracy is not accounted for in the results. Mean maximum temperature between freeze cycles was 5.13°C (95% confidence interval: −0.1 to 10.3) in the clamped right kidney group and 22.7°C (95% confidence interval: −16.6 to 28.8) in the nonclamped left kidney group, P < .05. Mean cryolesion volume, estimated on computed tomography perfusion, was 12.4 mL (95% confidence interval: 10.35-14.4) in the clamped right kidney group and 6.85 mL (95% confidence interval: 5.57-8.14) in the nonclamped left kidney group, P < .05. Pathological examination shows a higher degree of vital cells in the intermediate zone of the cryolesions in the nonclamped left kidneys when compared with the clamped right kidneys.

Conclusion:

Arterial clamping increases cryolesion size by approximately 80%, and pathologic examinations suggest a decreased risk of vital cells in the intermediate zone. The clamped kidneys showed no sign of injury from the limited ischemic insult. This study was limited by being a nontumor model.

Keywords: cryoablation, cryosurgery, animal research, renal cancer, central, endophytic, arterial clamping, ischemia

Introduction

During the last 3 decades, the widespread use of computed tomography (CT) has resulted in an increased number of accidentally diagnosed small renal masses (SRMs).1,2 In Europe, an estimated 84 400 new cases of renal cell carcinomas are diagnosed each year with more than 60% of these being T1a tumors, thus amenable for nephron-sparing surgery.3–5

The current gold standard for treating SRMs is partial nephrectomy (PN) as stated by both European Association of Urology and American Urology Association.5–7 However, with the introduction of commercially available cryosystems and with easy access to imaging such as CT or ultrasound, cryoablation (CA) has become an alternative to standard surgical procedures in selected patients.8 Several reviews have concluded that an advantage of CA compared to PN is an associated lower risk of complication and a better preservation of the renal function. When it comes to oncological outcome, CA is generally considered less effective compared to radical nephrectomy or PN.1,5–10 However, direct comparison of the 2 modalities is difficult due to selection biases and confounding. In addition, long-term data are still very sparse when it comes to CA and PN. Furthermore, no randomized study exists at this point.

Central and/or endophytic tumors have been demonstrated to be associated with a higher risk of treatment failure.11–13 Such central and/or endophytic tumors are likely to be subjected to a high volume of circulating warm blood giving thermal protection to cells in the vicinity of larger blood vessels.3,14,15 Temporary occlusion of the blood flow has been proposed as a way to limit this perfusion-mediated tissue heating (PMTH) effect.16–19 However, such occlusion will subject the kidney to general warm ischemia and the potential risk of injury to the renal parenchyma. The aim of this study was to evaluate the effect of renal artery clamping during laparoscopic cryoablation (LCA) in a porcine survival model by CT perfusion scan, histology, and radioisotope renography (RR).

Materials and Methods

Aarhus University and The Danish Authority on Animal Experiments approved the study. All animals were female Danish Landrace pigs weighing approximately 40 kg and being approximately 100 days old. On day 1, the animals underwent LCA on each kidney with clamping of the right renal artery/arteries. After surgery, the animals were kept at a certified animal research farm for 14 days. At day 14, a CT perfusion scan was performed together with an RR to give an estimate of differential renal function. After imaging, the kidneys were removed for histological examination, and the animals were killed.

Anesthesia

Premedication consisted of 2 mL Penovet Vet 300 000 IU/mL, 4 mL of Stresnil 40 mg/mL, 4 mL of Dormicum Vet 5 mg/mL, and 10 mL of Hypnomidate 2 mg/mL. During surgery, the animal was in general anesthesia and kept pain-free with an infusion of 10 mL/h fentanyl 50 μg/mL. A single dose of 750 mg cefuroxime was given before surgery and at the end of surgery, together with an intramuscular injection of 2 mL Finadyne 50 mg/mL.

Bilateral Renal CA With Unilateral Arterial Clamping

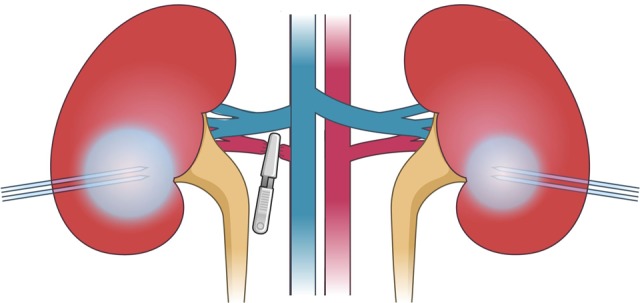

By a standard 3-port laparoscopic approach, the kidney was identified and the peritoneum covering the kidney was opened. On the right side, the renal hilum was carefully dissected to reveal the artery/arteries. One IceSphere 17-gauge cryoprobe (Galil Medical, Arden Hills, Minnesota) was inserted to a depth of 3 to 4 cm, going parallel with the collecting system toward the hilum in the lower pole (Figure 1). A multipoint 17-gauge Thermal Sensor (Galil Medical) was placed parallel with the cryoprobe at a distance of 10 mm. Endoscopic ultrasound (Analogic BK 4-Way Laparoscopic 8666-RF, Peabody, Massachusetts, USA) was used to assist and ensure correct placement of the cryoprobe and thermal sensor. Prior to initiation of the CA, an atraumatic endoscopic vessel clamp was placed on the renal artery/arteries. Cryoablation was delivered using a Visual-ICE System (Galil Medical) with argon gas for freezing and helium gas for thawing. The CA was a standard double-freeze cycle of 10-minute freeze followed by 6-minute passive thaw and 2-minute active thaw in each cycle. Arterial clamping was applied during freezing and removed during passive and active thawing. After the procedure, the cryoprobe and thermal sensor were removed and a TachoSil fibrin sealant patch (Takeda, Osaka, Japan) was placed over the insertion holes to prevent significant hemorrhage. The same procedure was performed on the left kidney but without dissection and clamping of the renal artery. All procedures were performed by the same surgeons (L.L.N. and T.K.N.).

Figure 1.

Cryoprobe placement.

The CT Perfusion Scan, RR, and Bilateral Nephrectomy

On day 14, the animals were subjected to general anesthesia as previously described. The renal differential function was estimated with RR done with DTPA, MAG3, or DMSA isotopes on a gamma scanner (Philips, BrightView Gamma Camera System, SYST, BRIGHTVIEW TILT, 3/8″; Philips Nuclear Medicine, Inc., California, USA). All CT perfusion examinations were performed using a 320-detector row CT scanner (Aquilion ONE; Toshiba Medical Systems, Otawara, Japan). A total dose of 30 mL Optiray 350 (Mallinckrodt Deutschland GmbH, Hennef, Germany) was used as contrast agent. The reconstructed data sets were transferred to a stand-alone workstation (Vitrea 6.3, Vital Images; Toshiba Medical Systems, Minnetonka) for postprocessing. For data analysis, the input artery was selected by placing a 100 mm2 circular region of interest (ROI) in the center of the abdominal aorta, and a second ROI was placed in normal renal parenchyma. Parametric perfusion maps were generated with the following perfusion parameters: arterial flow (tissue perfusion measured in mL·min−1·100 g−1), blood volume (measured in mL·100 g−1), and permeability (measured as ktrans in mL·min−1·100 g−1). The CT examinations were evaluated by an experienced uroradiologist (O.G.) in terms of the cryolesion location, size, and contrast enhancement (CE) of +25 HU. The cryolesions were measured cranial–caudal (CC), medial-lateral (ML), and anterior–posterior (AP). Assuming the cryolesions were sphere shaped, the volumes were calculated using the following formula: CC × ML × AP × 0.5. Each cryolesion was evaluated regarding vital parenchyma in the border zone and cavity of the cryolesion including calyx system. Mixed rim enhancement was defined as less than 50% rim enhancement of the cryolesion.

Both kidneys were removed and the animal was killed by an overdose of pentobarbital. The kidneys were fixated in a formalin solution for later histological examination by an experienced (>20 years) uropathologist (S.H.). Masson trichrome stain and cytokeratin AE1/AE3 immunostain were deemed appropriate owing to its usefulness in distinguishing vital tissue from fibrotic tissue.

Statistics

Kidneys were divided into a clamped right kidney and a nonclamped left kidney groups for statistical analysis and reporting. Fisher exact test was used for categorical variables and independent t test for continuous variables. Statistical significance was evaluated based on a 2-sided significance level of .05. Data analysis was performed using STATA version 13 software (StataCorp, LP, Texas, USA).

Results

Animals and Procedures

A total of 10 animals, giving 10 clamped right kidneys and 10 nonclamped left kidneys, were included in the study. No major complications were experienced during the surgical procedures, and the postoperative well-being of all animals was excellent.

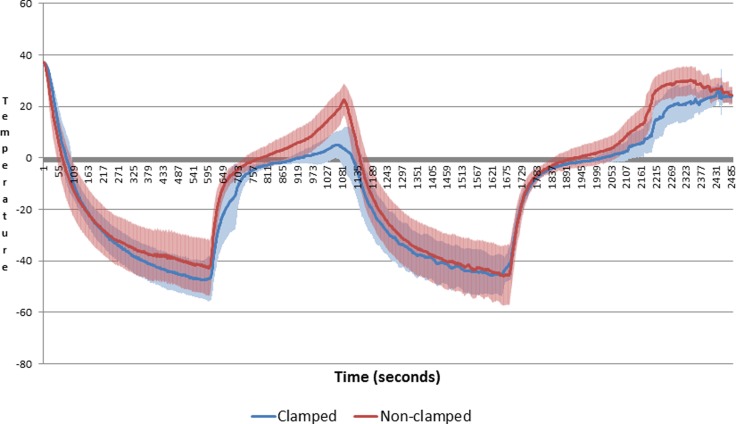

Temperature readings from the Visual-ICE system showed no significant differences between the clamped and nonclamped left kidney group in terms of lowest temperature or time to lowest temperature. The nonclamped left kidney group reached a significantly higher temperature between freeze cycles with 22.7°C (95% confidence interval [CI]: 16.6 to 28.8) versus 5.13°C (95% CI: −0.1 to 10.3), as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Mean temperature.

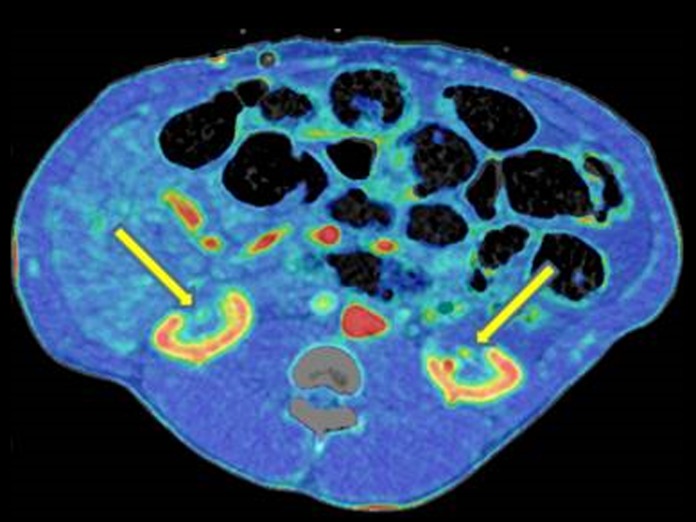

Perfusion CT Findings

All CAs had penetrated the calyx system and had a central position close to the renal hilum. The mean cryolesion volumes were 6.8 mL (95% CI: 5.57-8.17) in the nonclamped left kidney group compared to 12.37 mm3 (95% CI: 10.35-14.4) in the clamped right kidney group (P < .05). Three in the nonclamped left kidney group and 4 in the clamped right kidney group had vital arteries centrally in the cryolesion. An example of this is shown in Figure 3 with a 3-dimensional rendering from the CT perfusion scan. Parenchyma with CE in relation to the calyx system was seen in 3 in the clamped right kidney group and 1 in the nonclamped left kidney group. A single central nodular CE was found in both groups in the same animal, as shown in Figure 4. Rim/mixed rim CE was seen in 8 kidneys in both groups.

Figure 3.

Major perfused artery centrally in both cryolesions.

Figure 4.

Computed tomography (CT) perfusion scan of central nodular contrast enhancement.

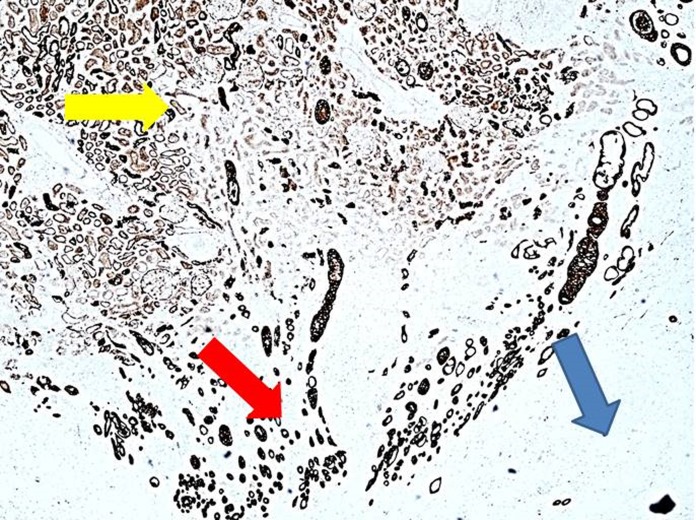

Histological Examinations

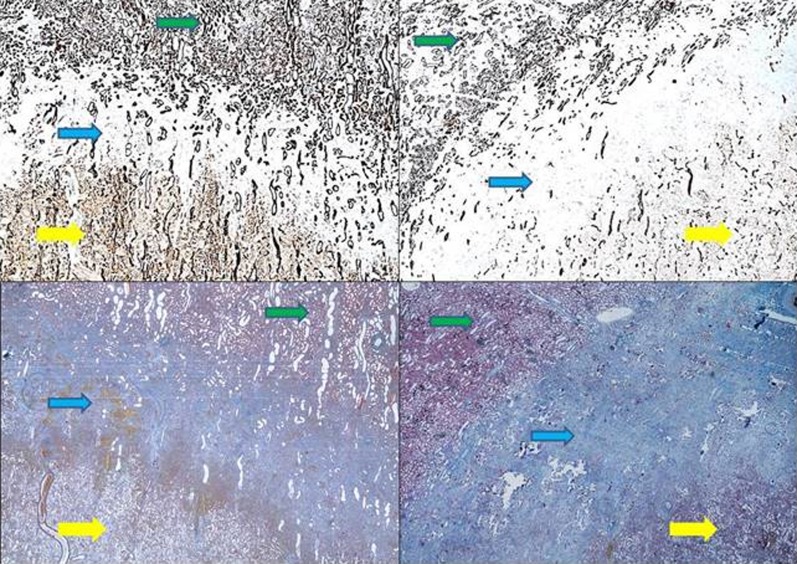

All cryolesions presented with distinct central zones of complete coagulative necrosis and intermidiate zones with partial coagulative necrosis. Both the clamped right kidney group and the nonclamped left kidney group displayed areas between the renal hilum and the central zone with vital epithelial cells (Figure 5). These areas are seen in close relation to the central zone of complete coagulative necrosis. When comparing to similar areas, not related to hilum, there would be fewer vital cells as seen in the intermediate zones (Figure 6). These findings were not affected by clamping as they were seen in both the clamped and nonclamped left kidney groups. The intermediate zones in the clamped right kidney group were more well defined when compared to the nonclamped left kidney group. The mean gross diameter at the widest point was 3.18 mm (95% CI: 2.8-3.55) in the nonclamped left kidney group and 2.82 mm (95% CI: 2.4-3.26) in the clamped right kidney group, which is not statiscally significant. Furthermore, the number of vital renal cells in the intermediate zone was higher in the nonclamped left kidney group compared to the clamped right kidney group (Figure 6). Hilar vessels of urothelia were found to be intact in all specimens. Lymfocyte infiltration below the renal capsule in the cryolesion was seen in 7 cryolesions in the clamped right kidney group compared to 5 cryolesions in the nonclamped left kidney group (not significant).

Figure 5.

Area with vital cells between central zone and renal hilum from the clamped group, cytokeratin AE1/AE3 immunostain, yellow arrow indicates central zone, red arrow indicates vital cells, and blue arrow indicates renal hilum, ×40.

Figure 6.

Left panel indicates nonclamped, right panel indicates clamped, top panel indicates cytokeratin AE1/AE3 stain, and bottom panel indicates Masson trichrome stain; yellow arrow indicates central zone, blue arrow indicates intermediate zones, green arrow indicates normal parenchyma, ×20.

Radioisotope Renography

The mean estimated differential renal functions were 44% (95% CI: 42-46) in the clamped right kidney group and 56% (95% CI: 54-58) in the nonclamped left kidney group, 2 weeks after surgery. These results are uncorrected for the ±5% technical inaccuracy and the different size in cryolesions.

Discussion

This model of central and endophytic CA has proved to be both a robust and a reproducible survival model, causing very little discomfort to the animals.

The mean postoperative differential renal function was 44%/56%. These results are uncorrected for the ±5% technical inaccuracy and different cryolesion sizes, which therefore are considered normal. This suggests that the renal function is not significantly affected on a short-term basis by 2 times 10 minutes of warm ischemia. These findings are similar to a review by Volpe et al. However, as stated in this review, the porcine renal physiology does not necessarily mimic humans.20 Most evidence on human renal ischemia comes from PN studies, which suggest that warm ischemia under 20 minutes is safe in a normal healthy kidney.8,21,22 However, if deemed necessary, several methods (renal cooling, optimizing kidney perfusion, segmental artery clamping) can be applied to further reduce the risk.23

The temperature readings showed no differences in terms of time to minimum temperature, which is probably due to the relative close proximity of the thermosensor probe. It was placed approximately 10 mm from the cryoprobe where all tissue and vessels are frozen solid, and therefore, any potential PMTH effect would not be evident. However, between freeze cycles, the nonclamped cryolesions reached a significantly higher temperature with a mean difference of +17.6°C compared to the clamped cryolesions. The reason for this might be the relative larger size of the clamped cryolesion, which requires a larger area to thaw before reaching the thermoprobe. Another explanation is a possible slowed reperfusion of the frozen arteries when clamping. However, the perfusion might even be increased in the clamped right kidney group given the thawing of a larger cryolesion. However, if there was a “hidden” hyperperfusion, it did not affect the viability of the cells in the cryolesions as seen by our histologic examinations.

A general increase in cryolesion size of 80% (clamped compared to nonclamped) was found. We consider this to be caused primarily by the arterial clamping and not the unavoidable minimal inaccuracy in placement of the cryoprobes. The overall structure of the porcine and the human kidneys resembles; however, this is a nontumor model. Porcine renal tissue was showed by Chosy et al to undergo complete necrosis at −19.4°C or lower,24 whereas temperatures of −40°C are recommend for tumors.25 This might lead to a possible smaller area of necrosis when treating tumorous tissue. Despite this, the effect of arterial clamping might still be present when comparing tumorous tissue. The objective of creating a larger cryolesion with 1 cryoprobe is irrelevant, because in most cases, multiple cryoprobes are used to ensure complete tumor coverage. However, other seemingly beneficial effects of clamping would probably still be present with multiple cryoprobes. Furthermore, renal fractures and major bleeding have been reported when using a large number of cryoprobes.26–28 The size increase also indicates a significant effect on CA by the renal blood flow.

Major vital arteries were identified on CT in 4 of the clamped cryolesions and 3 of the nonclamped cryolesions, suggesting that major arteries can survive being frozen regardless of arterial clamping. Janzen et al did a study on CA centrally in the kidney and also found vital arteries in approximately 50% of the study animals 30 days after treatment.15 Our histologic examinations have not found any evidence of vital renal cells in proximity of the vital arteries in the central necrotic zone. However, it would be difficult to investigate the length of an artery by histologic means.

The finding of vital arteries coupled with the radioisotope renographs suggests that central CA is safe in regard to peripheral renal tissue. Furthermore, no complications were experienced and no urothelial damage was found in the histologic examinations. Sung et al and Janzen et al did intentional CA on central renal structures in a porcine model and also found no evidence of urothelial damage when not physically puncturing.15,29 These findings are also validated on patients by Atwell et al.30 This supports the cryoresistance of the urothelia and the safety, in regard to complications, of using CA near the renal hilum.

Parenchymal CE in relation to the calyx system was 3 in the clamped right kidney group and 1 in the nonclamped left kidney group. This is probably due to the fact that cryolesion in the clamped right kidney group was larger, thus involving more renal tissue around the calyx system. This finding suggests some cryoprotective capabilities of the renal tissue close to the calyx system. Contrast enhancement in the central parenchyma was seen in 1 clamped cryolesion and 1 nonclamped cryolesion, indicating incomplete ablation in the central zone. The histologic examinations of these 2 kidneys did not find any vital renal tissue in the central zone. Two studies by Nielsen et al and Tsivian et al investigated CT findings after CA and found spontaneous resolution of CE in 45% and 56.7% of patients, with no association between nodular, diffuse, and rim enhancement pattern.31,32 Thus, our finding of nodular CE might not be evidence of residual vital tissue in the central zone of the cryolesion. The time of scan is only 14 days after treatment, where much remodeling of the tissue can be expected. Furthermore, these findings are on nontumors, why comparison should be taken with extreme caution.

Rim CE was seen in approximately 80% in both groups. Tsivian et al found 4 rim enhancements, with none needing retreatment. Furthermore, as stated in a review by Kawamoto et al, rim CEs are a benign physiologic response to ablation and are barely detectable after 3 months.33

Histologic examinations presented all lesions with the same central zone of complete necrosis. The intermediate zones of the clamped right kidney group were generally thinner and had fewer vital cells. By reducing the PMTH effect with arterial clamping, it can be expected that temperatures in the intermediate zone are lower, while also increasing the volume of the central zone. This effect might be beneficial when treating central SRMs. These can be located close to vital renal structures, which limits the possible tumor margins. Georgiades et al did an animal study where tumor margins of 6 mm were recommend; however, this might not always be possible.3 Furthermore, the mean diameter of the intermediate zones was on average 3 mm in all cryolesions. By utilizing arterial clamping, the surgeon will be able to secure a more defined tumor margin when margins of 6 mm are not possible. On the other hand, it may possibly make it more difficult to foresee cryolesion development—requiring the surgeon to using dosimetry more actively.

Our findings validate the findings of Auriol et al and Collyer et al who found a significant size increase when clamping while performing central and peripheral CA on porcine models.34,35 The study done by Collyer et al also found a significant increase in the intermediate zone but not a significant increased zone of complete necrosis, contradicting our findings. However, as stated by Collyer et al, the lack of significance is grossly related to a small number of animals, and they did see a mean increase of 4 mm of the zone of complete necrosis. Campbell et al did a study on canines where arterial occlusion was also investigated and found that arterial clamping did not increase cryolesion size or time to minimum temperature (cooling slope).36 The study by Campbell et al differs significantly from this study in several ways. Most importantly, the location of the cryoprobes was only inserted 10 mm into the lower pole, meaning a peripheral location and less major vessels. Furthermore, the cryolesions was created at −192°C, compared to the more clinically relevant −80°C used in this study.

A major limitation of our study is the nontumor nature of the model, and at this point, no tumor model in pigs is available for research. Furthermore, the number of animals used is relatively small, and the length between CA and examinations is short. The radiologic findings would be more comparable to human findings after at least 1 to 2 months; however, this was not possible given our time frame. The clinical significance of renal arterial occlusion during CA warrants randomized clinical trials before any recommendation can be made.

Conclusion

Arterial clamping increases cryolesion size by approximately 80%, and pathologic examinations suggest a decreased risk of vital cells in the intermediate zone. Vital arteries were found centrally in the cryolesion regardless of arterial clamping. The clamped kidneys showed no sign of short-term injury from the limited ischemic insult. This study was limited by being a nontumor model.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Takeda, Japan, for providing TachoSil fibrin sealant patches.

Abbreviations

- AP

anterior–posterior

- CA

cryoablation

- CC

cranial–caudal

- CE

contrast enhancement

- CI

confidence interval

- CT

computed tomography

- LCA

laparoscopic cryoablation

- ML

medial–lateral

- PMTH

perfusion-mediated tissue heating

- PN

partial nephrectomy

- ROI

region of interest

- RR

radioisotope renography

- SRMs

small renal masses

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Danish Council for Independent Research: 215 712 Danish Krone/US$32 708.18, Minimalt Invasiv UdviklingsCenter: 40 390 Danish Krone/US$6109.13, and Agnes Niebuhr Andersson’s Cancer Research Foundation: 18 000 Danish Krone/US$2729.32.

References

- 1. Kapoor A, Touma NJ, Dib RE. Review of the efficacy and safety of cryoablation for the treatment of small renal masses. Can Urol Assoc J. 2013;7(1-2):E38–E44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hollingsworth JM, Miller DC, Daignault S, Hollenbeck BK. Rising incidence of small renal masses: a need to reassess treatment effect. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98(18):1331–1334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Georgiades C, Rodriguez R, Azene E, et al. Determination of the nonlethal margin inside the visible “ice-ball” during percutaneous cryoablation of renal tissue. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2013;36(3):783–790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Levi F, Ferlay J, Galeone C, et al. The changing pattern of kidney cancer incidence and mortality in Europe. BJU Int. 2008;101(8):949–958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ljungberg B, Bensalah K, Bex A, et al. EAU guidelines on renal cell carcinoma. 2014. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6. Campbell SC, Novick AC, Belldegrun A, et al. Guideline for management of the clinical T1 renal mass. J Urol. 2009;182(4):1271–1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Novick AC, Campbell SC, Arie Belldegrun M, et al. Guideline for management of the clinical stage T1 renal mass. American Urological Association; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zargar H, Atwell TD, Cadeddu JA, et al. Cryoablation for small renal masses: selection criteria, complications, and functional and oncologic results. Eur Urol. 2016;69(1):116–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Klatte T, Shariat SF, Remzi M. Systematic review and meta-analysis of perioperative and oncologic outcomes of laparoscopic cryoablation versus laparoscopic partial nephrectomy for the treatment of small renal tumors. J Urol. 2014;191(5):1209–1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kapoor A, Wang Y, Dishan B, Pautler SE. Update on cryoablation for treatment of small renal mass: oncologic control, renal function preservation, and rate of complications. Curr Urol Rep. 2014;15(4):396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Yoost TR, Clarke HS, Savage SJ. Laparoscopic cryoablation of renal masses: which lesions fail? Urology. 2010;75(2):311–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wright AD. Endophytic lesions: a predictor of failure in laparoscopic renal cryoablation. J Endourol. 2007;21(12):1493–1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Yamanaka T, Yamakado K, Yamada T, et al. CT-guided percutaneous cryoablation in renal cell carcinoma: factors affecting local tumor control. J Vasc Intervent Radiol. 2015;26(8):1147–1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Janzen NK, Perry KT, Han K, et al. The effects of intentional cryoablation and radio frequency ablation of renal tissue involving the collecting system in a porcine model. J Urol. 2005;173(4):1368–1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ahmed M; Technology Assessment Committee of the Society of Interventional Radiology. Image-guided tumor ablation: standardization of terminology and reporting criteria—a 10-year update. J Vasc Intervent Radiol. 2014;25(11):1706–1708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Brace CL. Radiofrequency and microwave ablation of the liver, lung, kidney, and bone: what are the differences? Curr Probl Diagn Radiol. 2009;38(3):135–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Goldberg SN, Hahn PF, Tanabe KK, et al. Percutaneous radiofrequency tissue ablation: does perfusion-mediated tissue cooling limit coagulation necrosis? J Vasc Intervent Radiol. 1998;9(1 pt 1):101–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Oshima F, Yamakado K, Akeboshi M, et al. Lung radiofrequency ablation with and without bronchial occlusion: experimental study in porcine lungs. J Vasc Intervent Radiol. 2004;15(12):1451–1456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Neel HB, Ketcham AS, Hammond WG. Ischemia potentiating cryosurgery of primate liver. Ann Surg. 1971;174(2):309–318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Volpe A, Blute ML, Ficarra V, et al. Renal ischemia and function after partial nephrectomy: a collaborative review of the literature. Eur Urol. 2015;68(1):61–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Becker F, Poppel HV, Hakenberg OW, et al. Assessing the impact of ischaemia time during partial nephrectomy. Eur Urol. 2009;56(4):625–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Shah PH, George AK, Moreira DM, et al. To clamp or not to clamp? Long-term functional outcomes for elective off-clamp laparoscopic partial nephrectomy. BJU Int. 2016;117(2):293–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Klatte T, Ficarra V, Gratzke C, et al. A literature review of renal surgical anatomy and surgical strategies for partial nephrectomy. Eur Urol. 2015;68(6):980–992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chosy SG, Nakada SY, Lee FT, Jr, Warner TF. Monitoring renal cryosurgery: predictors of tissue necrosis in swine. J Urol. 1998;159(4):1370–1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Williams SK, de la Rosette JJMCH, Landman J, Keeley FX., Jr Cryoablation of small renal tumors. European Urology. 2007.

- 26. Rukstalis DB, Khorsandi M, Garcia FU, Hoenig DM, Cohen JK. Clinical experience with open renal cryoablation. Urology. 2001;57(1):34–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Schmit GD, Atwell TD, Callstrom MR, et al. Ice ball fractures during percutaneous renal cryoablation: risk factors and potential implications. J Vasc Intervent Radiol. 2010;21(8):1309–1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hruby G, Edelstein A, Karpf J, et al. Risk factors associated with renal parenchymal fracture during laparoscopic cryoablation. BJU Int. 2008;102(6):723–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sung GT, Gill IS, Hsu THS, et al. Effect of intentional cryo-injury to the renal collecting system. J Urol. 2003;170(2 pt 1):619–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Atwell TD, Carter RE, Schmit GD, et al. Complications following 573 percutaneous renal radiofrequency and cryoablation procedures. J Vasc Intervent Radiol. 2012;23(1):48–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Tsivian M, Kim CY, Caso JR, et al. Contrast enhancement on computed tomography after renal cryoablation: an evidence of treatment failure? J Endourol. 2012;26(4):330–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Nielsen TK, Østraat Ø, Andersen G, et al. Computed tomography contrast enhancement following renal cryoablation—does it represent treatment failure? J Endourol. 2015;29(12):1353–1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kawamoto S, Solomon SB, Bluemke DA, Fishman EK. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging appearance of renal neoplasms after radiofrequency ablation and cryoablation. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 2009;30(2):67–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Collyer W, Venkatesh R, Vanlangendonck R, et al. Enhanced renal cryoablation with hilar clamping and intrarenal cooling in a porcine model. Urology. 2004;63(6):1209–1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Auriol J, Combelle S, Mazerolles C, Rousseau H, Malavaud BA. Optimisation of renal cryotherapy by temporary occlusion of arterial inflow. An animal study. Eur Urol Suppl. 2012;11(1):e1119a–e1119a. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Campbell SC, Krishnamurthi V, Chow G, et al. Renal cryosurgery: experimental evaluation of treatment parameters. Urology. 1998;52(1):29–33; discussion 33-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]