Abstract

Background

Oxidative stress is highly prevalent in patients with end-stage renal disease and is linked to excess cardiovascular risk. Identifying therapies that reduce oxidative stress has the potential to improve cardiovascular outcomes in patients undergoing maintenance dialysis.

Study Design

Placebo-controlled, three-arm, double-blind, randomized, clinical trial

Setting & Participants

65 patients undergoing thrice-weekly maintenance hemodialysis

Intervention

Patients were randomly assigned in a 1:1:1 ratio to receive once daily CoQ10 (600 mg or 1200 mg) or matching placebo for 4 months.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was plasma oxidative stress, defined as plasma concentration of F2-isoprotanes. Secondary outcomes included plasma isofurans, cardiac biomarkers, pre-dialysis blood pressure, and safety/tolerability.

Measurements

F2-isoprostanes and isofurans were measured as plasma markers of oxidative stress, and N-terminal-pro-b-type natriuretic peptide and troponin T were measured as cardiac biomarkers at baseline, 1, 2, and 4 months.

Results

Among 80 patients randomized, 15 were excluded due to not completing at least one post-baseline study visit, and 65 were included in the primary intention-to-treat analysis. No treatment-related major adverse events occurred. Daily treatment with 1200 mg but not 600 mg CoQ10 significantly reduced plasma concentrations of F2-isoprostanes at 4 months compared to placebo (adjusted mean change −10.7 pg/ml [95% CI −7.1 to −14.3 pg/mL], P < 0.001; and −8.3 pg/ml [95% CI −5.5 to −11.0 pg/ml], P = 0.1, respectively). There were no significant effects of CoQ10 treatment on plasma isofurans, cardiac biomarker concentrations, or pre-dialysis blood pressures.

Limitations

Study not powered to detect small treatment effects; difference in baseline characteristics among randomized groups.

Conclusions

In patients undergoing maintenance hemodialysis, daily supplementation with 1200 mg of CoQ10 is safe and results in a reduction in plasma concentrations of F2-isoprostanes, a marker of oxidative stress. Future studies are needed to determine whether CoQ10 supplementation improves clinical outcomes for patients undergoing maintenance hemodialysis.

INTRODUCTION

Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death for patients undergoing maintenance hemodialysis (MHD) in the United States.1 The prevalence of risk factors traditionally associated with cardiovascular disease, such as diabetes, hypertension, and lipid abnormalities, is higher in MHD patients than in the general population.2 However, this increased prevalence of traditional risk factors does not explain most of the extraordinarily high cardiovascular disease risk in dialysis patients.3,4 Increased oxidative stress is present in patients undergoing MHD, and has been identified as a key contributor to the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis and other cardiovascular disease in this population.4–7 Identifying novel drug therapies that may reduce oxidative stress thus has the potential to improve clinical cardiovascular outcomes for patients undergoing MHD. F2-isoprostanes and isofurans, two products of non-enzymatic peroxidation of arachidonic acid that have been shown to be reliable markers of oxidative stress, are elevated in MHD patients, and thus represent ideal targets for interventions aimed at reducing oxidative stress burden.8–12

Coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10) is a potent lipophilic antioxidant that couples electron transport to oxidative phosphorylation in mitochondria, is readily available as a dietary supplement, and is used frequently as an alternative and complementary therapy. CoQ10 supplementation has previously been shown to have potential clinical benefit in the treatment of heart failure and improves endothelial function in patients with type II diabetes.13–16 Plasma concentrations of CoQ10 are depressed in patients undergoing MHD, suggesting that CoQ10 supplementation may represent an ideal antioxidant therapy for these patients.17

In this study, we hypothesized that administration of coenzyme Q10 would lead to improvements in biomarkers of oxidative stress in patients undergoing MHD. We also assessed effects of the intervention on biomarkers of cardiac function and pre-dialysis blood pressures, and further monitored study agent safety and tolerability as secondary outcomes measures.

METHODS

Study Design and Participants

This was a pilot, double-blind, parallel group, randomized clinical trial comparing daily CoQ10 antioxidant therapy at two different doses (600 mg daily and 1200 mg daily), with matching placebo (NCT01408680). Study subjects were recruited by study coordinators from outpatient dialysis facilities in the Seattle metropolitan area from September 2011 through April 2013. Criteria for study participation included: patients receiving thrice-weekly MHD for at least 90 days, age >18 and <85 years, life expectancy greater than 1 year, and the ability to provide informed consent. Exclusion criteria included history of poor adherence to dialysis or medications; kidney transplant less than 6 months before study enrollment; use of antioxidant nutritional supplements other than vitamin-C; hospitalization within 30 days, history of a major atherosclerotic event within six months; and current use of a hemodialysis catheter.

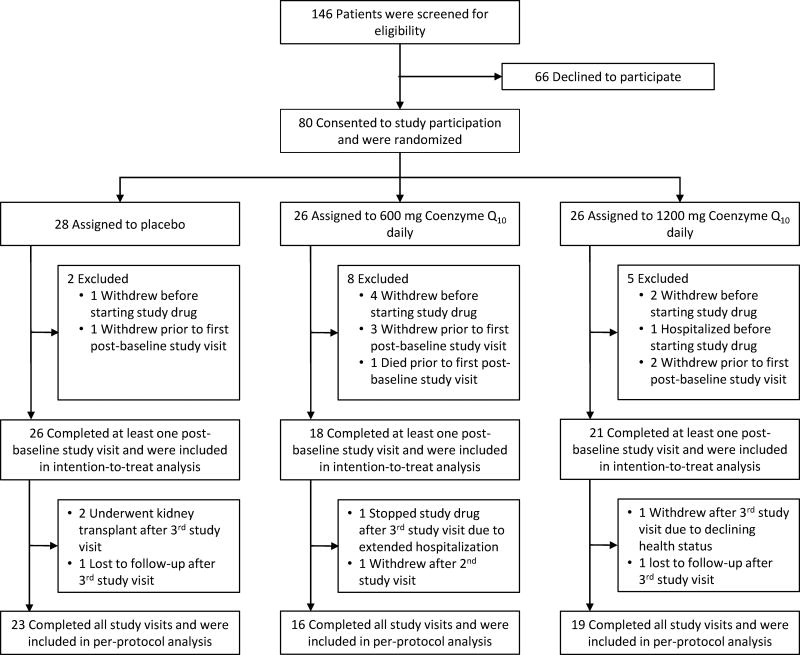

A total of 146 patients were assessed for eligibility, and 80 gave consent and were randomized (Figure 1). Subjects were randomly assigned to one of the three study groups in a 1:1:1 ratio by a permuted block randomization strategy using a block size of 12. Prior to starting study treatment, seven subjects voluntarily elected not to participate in the study and one subject was hospitalized. Additionally, one subject assigned to placebo, 3 subjects assigned to 600 mg CoQ10, and 2 subjects assigned to 1200 mg CoQ10 withdrew from the study prior to the first post-baseline study visit. One subject assigned to 600 mg CoQ10 died prior to the first post-baseline visit. Thus, 65 subjects were included in the intention-to-treat analysis. Of these, 58 (89%) completed the study (600 mg CoQ10 group; 16; 1200 mg CoQ10 group, 19; placebo group, 23) and were included in the per-protocol analysis (Figure 1). Among subjects included in the intention-to-treat analysis who did not complete all four study visits, two assigned to the placebo group underwent kidney transplant, one assigned to the placebo group and one assigned to 1200 mg CoQ10 were lost to follow-up, one assigned to 600 mg and one assigned to 1200mg CoQ10 withdrew consent, and one assigned to 1200mg CoQ10 stopped the study drug due to an extended hospitalization (Figure 1). A data safety monitoring board oversaw the safety profile of the study, and no interim efficacy analyses were planned or conducted. The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the University of Washington Institutional Review Board (Human Subjects Application #40428). All subjects provided written informed consent before study enrollment.

Figure 1. Flow chart of study population, including the number of patients who were screened, gave consent, underwent randomization, completed the study treatment and were analyzed for the primary outcome.

Study Procedures

Subjects were screened for eligibility criteria within 28 days prior to beginning the study. The duration of study treatment was 4 months, and subjects underwent in-person pre-dialysis assessments at a dialysis facility at baseline, 2 weeks, and monthly thereafter. Fasting blood sample collection was performed at baseline, 1, 2 and 4 months. CoQ10 was provided by study coordaintors to patients as a chewable wafer (Vitaline Formulas, Wilsonville, OR), and matching wafers were provided to the placebo group (CuliNex, LLC, Seattle, WA; and College Pharmacy, Colorado Springs, CO). Throughout the course of the study, patients received usual dialysis care prescribed by each patient’s nephrologist.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was change in the plasma marker of oxidative stress F2-isoprotanes from baseline. Secondary outcomes included change in plasma isofurans concentration, plasma CoQ10 concentration and CoQ10 redox ratio (defined as the ratio of reduced CoQ10H2 [ubiquinol] to oxidized CoQ10 [ubiquinone]), changes in biomarkers of cardiac function (troponin T and n-terminal pro-b-type natriuretic peptide [NT-proBNP]), and changes in pre-dialysis blood pressures. Safety and tolerability of the CoQ10 preparations over the 4 month study period, defined as incidence of treatment-related adverse events and number of patients prematurely discontinuing study treatment, respectively, were also assessed as secondary outcomes. Adverse events were assessed by study coordinators at study visits using open-ended questions, and were attributed to study treatment by study investigators, who were blinded to assigned treatment.

Analytic Procedures

Heparinized blood samples were transported to the lab on ice and centrifuged within one hour of collection at 2500 RPM, 4°C, for 15 minutes. Plasma was removed, stored at −80°C, and thawed immediately prior to analysis. For measurement of CoQ10, 100 µL aliquots were mixed with 200 µL ice cold 1-propanol containing Coenzyme Q9 (CoQ9) and CoQ9H2 as internal standards. Precipitated proteins were removed by cold centrifugation, and the supernatant analyzed using an Agilent 6400-series liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometer (Agilent Technologies, Inc., Santa Clara, CA) equipped with a Zorbax SB-C18 column maintained at 40°C.18

For F2-isoprostanes and isofurans measurements, internal standard [2H4]-15-F2T-isoprostane was added to plasma and followed by C-18 and silica solid phase extraction, thin layer chromatography, and derivatization to penta-fluorobenzyl ester, trimethylsilyl ether in preparation for gas chromatography/negative ion chemical ionization/mass spectrometry analysis (Agilent 5973, Agilent Technologies, Inc., Santa Clara, CA) using 15 cm × 0.25 µm thick fused silica capillary columns.19 Cardiac troponin T and NT-proBNP were measured using electrochemiluminescent-based immunoassays with calibrators and external controls run prior to samples (cobas® E411, Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN).

Statistical Analyses

Sample size was computed on the basis of change in F2-isoprostanes concentrations from baseline to 4 months using a t-test approach. Previously published observational data among MHD patients showed a mean F2-isoprostane concentration of 96.2 pg/mL, with a standard deviation of 48.8 pg/mL.8 In the absence of available data from interventional studies from which to estimate an effect size, a reduction in F2-isoprostane concentrations by 50% was postulated a priori to be clinically significant.20 Given these assumptions, a sample size of 22 in each study arm (total, 66) was estimated to achieve 86% power to detect a 50% reduction in the primary outcome with a two-sided 5% significance level, assuming a drop-out rate of 10%.

Primary analyses were performed on an intention-to-treat basis, including all randomized participants who completed at least one post-baseline study visit, regardless of adherence or compliance status. Secondary analyses were performed on a per-protocol basis, including only patients who reported adherence to the assigned study agent and who completed all study visits. Multiple imputation for missing laboratory and blood pressure outcome data among study participants who did not complete all study follow-up visits was performed using chained equations with 5 imputations, with estimates combined using Rubin’s rules.21–24 Missing values were modelled as continuous variables using linear regression. Imputation regressions included fixed independent variables for age, sex, race, etiology of end-stage renal disease, and also included oxidative stress, cardiac biomarker, and blood pressure values from prior study visits. Using this approach, laboratory and blood pressure outcome data for the third study visit were imputed for one subject, and for the fourth study visit for 7 subjects. Least squares means for study outcomes at each time point were determined using linear regression with robust standard errors adjusted for age, sex, race, and etiology of end-stage renal disease. The effect of randomized treatment assignment on primary and secondary outcomes over follow-up was assessed using generalized estimating equations with respect to intervention arm and time, with an unstructured correlation matrix. Changes from baseline to 1, 2, and 4 months of follow-up for each study outcome were also assessed using linear regression. All models included baseline values, age, sex, race, and etiology of end-stage renal disease as covariates due to observed imbalance among treatment groups, an approach that was pre-specified in the study protocol. CoQ10 levels, oxidative stress markers, and cardiac biomarkers were log-transformed prior to analysis due to right-skewed distributions. One value for NT-proBNP of >350,000 pg/ml was greater than 4-fold higher than the next highest value and was excluded from analyses. All analyses were performed using Stata, version 11 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX; www.stata.com). The nominal level of significance was defined as P<0.05.

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics

Overall, subjects had a mean age of 54 ± 13 years; 22 subjects (34%) were female, 17 (26%) were black, and 25 (40%) had diabetes (Table 1). Over 90% of subjects dialyzed using an arteriovenous fistula. Patients assigned to receive 600 mg CoQ10 daily were younger, more likely to be black, and less likely to have diabetes compared to patients assigned to the placebo group. Patients assigned to receive 1200 mg CoQ10 daily were less likely to be black and more likely to have diabetes and cardiovascular disease compared to patients assigned to placebo. The proportion of patients assigned to each treatment group did not differ between patients who dropped out and those who did not (Supplemental Table S1).

Table 1.

Baseline Patient Characteristics by Treatment Group

| Placebo (N = 26) |

600 mg Coenzyme Q10 (N = 18) |

1200 mg Coenzyme Q10 (N = 21) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 57± 13 | 49 ± 16 | 56 ± 12 |

| Male gender, n (%) | 19 (69) | 12 (67) | 13 (62) |

| Race, n (%) | |||

| White | 18 (69) | 8 (44) | 12 (57) |

| Black | 6 (23) | 7 (38) | 4 (18) |

| Asian | 1 (4) | 1 (6) | 2 (10) |

| Other/Unknown | 1 (4) | 2 (12) | 3 (15) |

| Height, centimeters | 171 ± 10 | 174 ± 11 | 170 ± 9 |

| Weight, kilograms | 86 ± 28 | 93 ± 31 | 85 ± 22 |

| Body Mass Index | 29 ± 8 | 31 ± 10 | 29 ± 7 |

| Months since initiation of dialysis | 31 (17, 68) | 67 (33, 88) | 38 (14, 71) |

| Cause of end-stage renal disease, n (%) | |||

| Diabetes | 8 (31) | 4 (22) | 10 (47) |

| Hypertension | 9 (35) | 2 (11) | 6 (29) |

| Glomerular Disease | 3 (12) | 4 (22) | 0 |

| Other | 6 (23) | 8 (45 | 5 (24) |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | |||

| Diabetes | 8 (35) | 7 (39) | 10 (48) |

| Hypertension | 22 (85) | 17 (94) | 18 (90) |

| Cardiac Disease | 6 (23) | 3 (17) | 6 (32) |

| Stroke | 3 (12) | 3 (17) | 1 (6) |

| Peripheral Vascular Disease | 4 (17) | 3 (17) | 5 (26) |

| Dyslipidemia | 5 (19) | 5 (31) | 8 (40) |

| Cancer | 5 (19) | 3 (18) | 2 (11) |

| Tobacco Use, n (%) | |||

| Current smoker | 3 (12) | 3 (17) | 2 (10) |

| Ever smoker | 11 (42) | 10 (56) | 10 (48) |

| Never smoker | 15 (58) | 8 (44) | 11 (52) |

| Vascular Access Type, n (%) | |||

| Arteriovenous fistula | 24 (92) | 15 (83) | 19 (90) |

| Arteriovenous graft | 2 (8) | 3 (17) | 2 (10) |

| Medications, n (%) | |||

| ACE inhibitor or ARB | 6 (23) | 8 (44) | 9 (43) |

| Anti-platelet agent | 10 (38) | 3 (17) | 13 (62) |

| Statin | 8 (31) | 4 (22) | 7 (33) |

| Insulin | 6 (23) | 3 (17) | 8 (38) |

| Beta-blocker | 10 (38) | 11 (61) | 7 (33) |

Summary statistics are mean ± SD, median (interquartile range) or number (%) as appropriate.

Abbreviations: ACE, angiotensin converting enzyme; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker

Change in Plasma CoQ10 Concentrations

Compared to patients assigned to placebo, those assigned to either 600 mg or 1200 mg CoQ10 had significantly higher mean plasma CoQ10 concentrations over study follow-up (P = 0.001, and P < 0.001, respectively) (Table 2). There was no significant difference in the mean CoQ10 redox ratio among patients assigned to placebo versus 600 mg daily CoQ10 supplementation. In contrast, after adjustment for baseline values, patients assigned to 1200 mg of CoQ10 had a significantly higher mean redox ratio over study follow-up, (P < 0.001).

Table 2.

Mean Total Plasma Coenzyme Q10 Concentrations and Coenzyme Q10 Redox Ratios over Study Period, by Treatment Group

| Placebo (N = 26) |

600 mg Coenzyme Q10 (N = 18) |

1200 mg Coenzyme Q10 (N = 21) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Total CoQ10, ng/ml | |||

| Baseline | 624 (516, 731) | 720 (568, 872) | 490 (375, 604) |

| 1 month | 737 (489, 984) | 1901 (1354, 2448) | 2875 (2308, 3443) |

| 2 months | 642 (445, 840) | 1878 (1329, 2427) | 2938 (2247, 3629) |

| 4 months | 681 (426, 936) | 1901 (1280, 2521) | 1974 (1328, 2621) |

| p-valuea | Reference | 0.001 | <0.001 |

| CoQ10redox ratiob | |||

| Baseline | 13.6 (11.1, 16.2) | 14.4 (11.5, 17.4) | 12.8 (10.7, 15.0) |

| 1 month | 15.5 (11.7, 17.4) | 15.5 (12.7, 18.2) | 20.4 (16.8, 24.1) |

| 2 months | 13.9 (10.9, 16.9) | 15.4 (12.8, 18.1) | 18.5 (15.2, 21.8) |

| 4 months | 16.0 (12.8, 19.1) | 14.1 (11.9, 16.2) | 16.8 (13.4, 20.1) |

| p-valuea | Reference | 0.34 | <0.001 |

Note: Results reported are from the primary intention-to-treat analysis. Values are least squares mean (95% confidence interval), adjusted for age, sex, race, and etiology of end-stage renal disease.

p-value for comparison of average treatment effect from generalized estimating equation model, adjusted for age, sex, race, etiology of end stage renal disease, and baseline measurements; reference group: placebo. Outcome measurements log transformed prior to analysis.

CoQ10 redox ratio calculated as ratio of CoQ10H2 (reduced) to CoQ10 (oxidized)

Change in Plasma F2-Isoprostane Concentrations

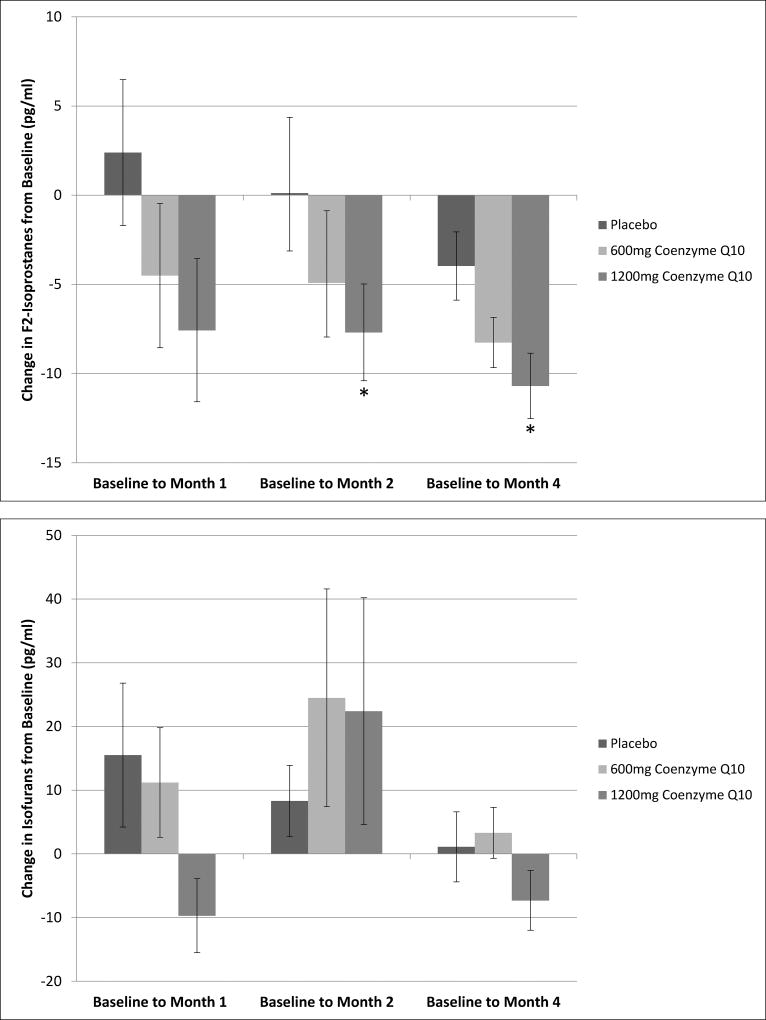

Compared to patients assigned to placebo, patients assigned to 1200 mg daily CoQ10 supplementation had significantly lower mean plasma concentrations of F2-isoprostanes over the study treatment period (P = 0.002) (Table 3). Adjusted mean change from baseline for plasma F2-isoprostanes in patients assigned to this higher dose of CoQ10 was −7.7 pg/ml (95% confidence interval [CI] −2.4 to −13.0 pg/ml) at 2 months and −10.7 pg/ml (95% CI −7.1 to −14.3 pg/ml) at 4 months (P = 0.005 and P < 0.001, respectively) (Figure 2). For patients assigned to 600 mg daily CoQ10, there was a decrease in F2-isoprostane concentrations from baseline to the 4-month follow-up time point of −8.3 pg/ml (95% CI −5.5 to −11.0 pg/ml), but this change was not significantly different compared to the placebo group (P = 0.10). Mean F2-isoprostanes concentrations over the 4-month study duration were also not significantly different for patients assigned to 600 mg CoQ10 compare to those assigned to placebo.

Table 3.

Mean Plasma Markers of Oxidative Stress over Study Period, by Treatment Group

| Placebo (N = 26) |

600 mg Coenzyme Q10 (N = 18) |

1200 mg Coenzyme Q10 (N = 21) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| F2-isoprostanes, pg/ml | |||

| Baseline | 49.3 (40.6, 58.0) | 45.6 (35.1, 56.1) | 62.4 (43.5, 81.3) |

| 1 month | 54.0 (44.8, 63.2) | 47.1 (38.7, 55.6) | 48.5 (36.8, 60.3) |

| 2 months | 50.4 (41.1, 59.7) | 42.1 (32.6, 51.6) | 51.9 (37.2, 66.7) |

| 4 months | 45.1 (36.6, 53.6) | 39.2 (30.9, 47.6) | 47.5 (33.2, 61.8) |

| p-valuea | Reference | 0.34 | 0.002 |

| Isofurans, pg/ml | |||

| Baseline | 64.8 (56.4, 73.1) | 68.1 (60.1, 76.2) | 94.2 (77.7, 110) |

| 1 month | 86.2 (62.5, 110) | 84.5 (67.5, 102) | 73.2 (57.4, 88.9) |

| 2 months | 75.6 (62.5, 86.7) | 90.0 (57.9, 122) | 115 (74.8, 155) |

| 4 months | 69.8 (60.0, 79.6) | 73.5 (62.9, 84.0) | 82.8 (66.7, 98.9) |

| p-valuea | Reference | 0.71 | 0.07 |

Note: Results reported are from the primary intention-to-treat analysis. Values are least squares means (95% confidence interval), adjusted for age, sex, race, and etiology of end-stage renal disease.

p-value for comparison of average treatment effect from generalized estimating equation model, adjusted for age, sex, race, etiology of end stage renal disease, and baseline measurements; reference group: placebo. Outcome measurements log transformed prior to analysis.

Figure 2. Mean Change in Plasma F2-Isoprostanes and Isofurans Concentrations from Baseline to Months 1, 2 and 4 of Follow-up, by Treatment Group.

Values are least squares means adjusted for baseline measurements, age, sex, race, etiology of end-stage renal disease. Error bars represent ± standard error of the least squares mean. Asterisk indicates P < 0.01 for comparison of mean change from baseline with reference group of patients assigned to placebo.

Secondary Outcomes

In contrast to the findings for the primary outcome measure, there was no significant change from baseline in plasma concentrations of isofurans with either either dose of CoQ10 (Figure 2). There was a trend toward lower mean concentrations of isofurans over the 4-month study period for patients assigned to 1200 mg CoQ10 compared to placebo, though this trend was not statistically significant (P = 0.07) (Table 3). There were also non-significant trends toward lower mean serum concentrations of NT-proBNP and cardiac troponin T for patients assigned to the higher CoQ10 dose compared to placebo (P = 0.10 and P = 0.09, respectively) (Table 4). These trends were not evident for patients assigned to the lower 600 mg dose. There were no significant differences in mean pre-dialysis systolic or diastolic blood pressures comparing patients assigned to either dose of CoQ10 versus placebo (Table 4).

Table 4.

Mean Pre-Dialysis Blood Pressure and Serum Concentrations of Cardiac Troponin T and N-terminal-proBNP, by Treatment Group

| Placebo (N = 26) |

600 mg Coenzyme Q10 (N = 18) |

1200 mg Coenzyme Q10 (N = 21) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| Troponin T, ng/ml | |||

| Baseline | 0.05 (0.04, 0.07) | 0.11 (0.07, 0.15) | 0.09 (0.04, 0.14) |

| 1 month | 0.08 (0.04, 0.11) | 0.11 (0.07, 0.16) | 0.08 (0.03, 0.13) |

| 2 months | 0.05 (0.04, 0.08) | 0.10 (0.07, 0.14) | 0.08 (0.02, 0.15) |

| 4 months | 0.07 (0.04, 0.10) | 0.11 (0.07, 0.15) | 0.06 (0.02, 0.10) |

| p-valuea | Reference | 0.71 | 0.10 |

| N-terminal-proBNP, pg/ml | |||

| Baseline | 8412 (2672, 13,151) | 8862 (4262, 13,461) | 6794 (2668, 10,920) |

| 1 month | 11,294 (5033, 17,555) | 8857 (2958, 14,757) | 7768 (2443, 13,094) |

| 2 months | 10,740 (5579, 15,901) | 11,169 (4714, 17.624) | 6062 (0, 12,353) |

| 4 months | 9562 (2803, 16,321) | 13,510 (5752, 21,268) | 2601 (0, 5558) |

| p-valuea | Reference | 0.92 | 0.09 |

| Pre-dialysis systolic blood pressure, mmHg | |||

| Baseline | 133 (126, 140) | 144 (134, 155) | 138 (131, 146) |

| 1 month | 136 (127, 145) | 144 (136, 152) | 143 (131, 154) |

| 2 months | 141 (130, 151) | 146 (135, 157) | 143 (131, 154) |

| 4 months | 138 (127, 150) | 140 (131, 150) | 128 (112, 143) |

| p-valuea | Reference | 0.87 | 0.90 |

| Pre-dialysis diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | |||

| Baseline | 73 (67, 79) | 78 (68, 89) | 75 (69, 81) |

| 1 month | 73 (66, 79) | 78 (72, 84) | 77 (68, 85) |

| 2 months | 77 (69, 85) | 79 (70, 87) | 77 (69, 85) |

| 4 months | 75 (68, 82) | 77 (71, 84) | 70 (62 (78) |

| p-valuea | Reference | 0.99 | 0.93 |

Note: Results reported are from the primary intention-to-treat analysis. Values are least squares means (95% confidence interval), adjusted for age, sex, race, and etiology of ESRD.

p-value for comparison of average treatment effect from generalized estimating equation model, adjusted for age, sex, race, etiology of ESRD, and baseline measurements; reference group: placebo. Outcome measurements log transformed prior to analysis.

Sensitivity Analyses

Three sets of sensitivity analyses were performed. In the first, per-protocol analyses were performed among the pre-specified group of patients who completed all four study visits and who adhered to the assigned study treatment (N = 58). In these per-protocol analyses, the non-significant trends seen in the primary analysis toward lower mean concentrations of isofurans, troponin T and NT-proBNP among patients assigned to 1200 mg CoQ10 compared to placebo were found to be significant (P < 0.05) (Supplementary Tables S2 and S3). In a second set of sensitivity analyses, statistical comparisons were performed adjusting only for baseline outcome values, and were similar to the primary results. Finally, analyses performed replacing missing laboratory values with the last observed value rather than using multiple imputation also showed similar results.

Safety and Tolerability

Adverse events in study participants are reported in Table 5. One patient assigned to 600 mg CoQ10 died two weeks after enrollment, prior to the second study visit. Six patients were hospitalized, including 1 patient assigned to placebo, 3 patients assigned to 600 mg CoQ10, and 2 patients assigned to 1200 mg CoQ10. One hospitalization for abdominal pain in a patient assigned to 1200 mg CoQ10 was deemed possibly related to study treatment. Study agents were generally well tolerated. One patient assigned to 600 mg CoQ10 elected to discontinue treatment after the second study visit due to difficulty chewing the study agent wafers. One patient assigned to 600 mg and one assigned to 1200 mg CoQ10 withdrew prior to the second study visit due to gastrointestinal discomfort. The overall adverse event rates were 0.25, 1.3, and 0.45 per patient-year for placebo, 600 mg and 1200 mg CoQ10, respectively.

Table 5.

Adverse Events in Study Participants

| Placebo (N = 28) |

600 mg Coenzyme Q10 (N = 26) |

1200 mg Coenzyme Q10 (N = 26) |

P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serious adverse eventsa | 2 (7) | 5 (19) | 3 (12) | 0.4 |

| Death | 0 (0) | 1 (4) | 0 (0) | 0.3 |

| Initial or prolonged hospitalizationb | 1 (4) | 3 (12) | 2 (8)c | 0.5 |

| Important medical events | 1 (4) | 1 (4) | 1 (4) | 0.9 |

| Other adverse events | 0 (0) | 2 (8) | 1 (4) | 0.3 |

| Abdominal discomfort | 0 (0) | 1 (4) | 1 (4) | 0.6 |

| Hyperkalemia not requiring hospitalization | 0 (0) | 1 (4) | 0 (0) | 0.3 |

Note: Values are given as number (percentage). Adverse events assessed among all randomized subjects, and defined as any undesirable medical event occurring to a subject, whether or not it is related to the study agent.

Serious adverse event (SAE) defined as: death, life-threatening experience, inpatient hospitalization or prolongation of existing hospitalization, persistent or significant disability/incapacity, congenital anomaly/birth defect, or an important medical events that may jeopardize the subject and may require medical or surgical intervention

One hospitalization for abdominal pain in a patient assigned to 1200 mg CoQ10 was deemed possibly related to study treatment. All other adverse events were deemed unlikely related to study treatment.

DISCUSSION

In this randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of patients receiving MHD, the provision of daily CoQ10 as antioxidant therapy was safe, well tolerated, and resulted in a significant and dose dependent increase in plasma CoQ10 levels compared to placebo. In addition, CoQ10 supplementation using a 1200 mg daily dose significantly decreased plasma concentrations of F2-isoprostanes, a robust plasma marker of oxidative stress. In the primary intention-to-treat analysis, there was no significant effect of CoQ10 on plasma isofurans, troponin-T, and NT-proBNP, or on pre-dialysis systolic or diastolic blood pressures. However, trends toward reductions in isofurans, troponin-T, and NT-proBNP with 1200 mg daily CoQ10 were evident, and were significant in a per-protocol analysis.

We chose to study CoQ10 in this clinical trial for a number of reasons. First, CoQ10 is a readily available dietary supplement that has shown a favorable safety profile and has been well tolerated at high doses in previous clinical trials of patients with congestive heart failure, diabetes, and a variety of neurological disorders.25–28 Second, patients undergoing MHD are known to have low plasma CoQ10 levels compared to age- and sex-matched healthy individuals, and that these levels are associated with reduced coronary blood flow.17,29 Third, previous data from a non-randomized CoQ10 dose escalation study in MHD patients confirmed that doses as high as 1800mg per day were safe and well-tolerated, and suggested that CoQ10 supplementation may be associated with improvements in oxidative stress burden in these individuals.30 Finally, prior studies have shown that in patients with kidney disease, perturbations in cell metabolism lead to preferential dysregulation of mitochondrial respiratory machinery that is closely associated with the enhanced oxidative stress seen in these individuals.31,32 CoQ10, which exerts antioxidant activity by coupling electron transport to oxidative phosphorylation locally in mitochondria, thus represents an ideal antioxidant agent for the dialysis population.

In our study, we found that CoQ10 supplementation significantly reduced plasma F2-isoprostanes but not isofurans concentrations. Prior studies have demonstrated that relative formation of lipid peroxidation products is profoundly influenced by ambient oxygen concentration.10 Specifically, in highly oxygenated tissues such as the central nervous system, isofurans formation predominates, while F2-isoprostanes formation is favored in cellular environments where oxygen concentrations are low. In advanced chronic kidney disease, rarefication of post-glomerular capillaries leads to substantial tissue hypoxia.33 Additionally, uremia leads to accelerated atherogenesis, and recent research has suggested that atherosclerotic plaques are characterized by hypoxic cores.34 Thus, in patients undergoing maintenance dialysis, production of F2-isoprostanes as a marker of oxidative stress may predominate, and thus be preferentially amenable to reduction with antioxidant therapy. These observations together provide one possible explanation for the observed differential effect of CoQ10 on F2-isoprostanes compared to isofurans in our study.

In addition to the impact of CoQ10 administration on F2-isprostanes, we observed a reduction in troponin T and NT-pro-BNP concentrations with CoQ10 supplementation in a pre-specified per-protocol analysis. Such a trend is consistent with previous investigations among healthy patients that have observed an inverse association between serum levels of CoQ10 and NT-proBNP, and a reduction in NT-proBNP levels in individuals assigned to take CoQ10 supplements.35,36 Additionally, a large multi-center randomized trial conducted in patients with moderate to severe heart failure showed a trend toward decline in NT-proBNP with even low dose (300 mg per day) CoQ10 supplementation.13 To our knowledge our findings represent the first report of a potential benefit of antioxidant therapy on markers of cardiac function in patients with kidney disease. Larger trials will be required for assessment of postulated cardiovascular and other clinical benefits.

This pilot study has a number of important strengths. First, we used a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study design, and had low drop-out rates and high treatment adherence. Second, we used a CoQ10 formulation with well-established bioavailability and purity that has been used previously in randomized clinical trials.37,38 Third, the lipid peroxidation biomarkers (F2-isoprostanes and isofurans) were analyzed in a reference quality laboratory using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry, and CoQ10 concentrations were measured via a validated technique utilizing ultra-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry.

Despite its strengths, the results of our study should be interpreted in light of some limitations. First, this was a pilot study, and the small number of participants resulted in limited statistical power to demonstrate small treatment benefits. Thus, it is possible that the in a larger study, a CoQ10 dose of 1200 mg may result in a significant reduction in troponin T and NT-proBNP. Second, there were some differences in baseline characteristics between the treatment groups due to chance in the setting of a small number of subjects randomized. We attempted to account for these differences through statistical adjustment, but residual confounding by measured or unmeasured factors may exist. If present, such residual confounding may have influenced the magnitude of the observed treatment effect, and the directionality of such influence may be unclear. Third, in our study we observed attrition of subjects following randomizing, including five subjects assigned to the placebo group, 10 subjects assigned to 600 mg CoQ10 and 7 subjects assigned to 1200 mg CoQ10. Although the a priori defined primary analysis pre-specified inclusion only of subjects who completed at least one post-baseline study visit, the differential attrition of subjects from the CoQ10 groups compared to the placebo group may have led to baseline imbalance among groups. We have partially addressed this limitation by utilizing multiple imputation for missing outcome data among subjects who withdrew from the study after the second study visit and by adjusting for baseline characteristics in our statistical models, but we cannot exclude the possibility that differential attrition led to bias in our estimates of treatment effect. Fourth, in our study we measured only two products of lipid peroxidation (F2-isoprostanes and isofurans) as markers of systemic oxidative stress, and did not assess other oxidative stress pathways such as protein or DNA oxidation. Although isoprostanes have been shown in previous studies to be the most accurate and reliable plasma measures of oxidative injury in vivo, it is possible that CoQ10 supplementation may have had an effect on oxidative stress pathways that we did not assess.39–41 Finally, there were differences in baseline concentrations of F2-isoprostanes and isofurans among the treatment groups observed, again due to chance in the setting of the small number of study participants. In the primary analyses, we adjusted for baseline biomarker concentrations to ensure robust statistical comparisons, but we cannot exclude a possible contribution of regression toward the mean in the observed CoQ10 treatment effect.

In conclusion, in patients undergoing MHD, daily CoQ10 supplementation was safe and well tolerated, and resulted in a reduction in F2-isoprostanes, a plasma marker of oxidative stress. Future studies are warranted to determine whether treatment with CoQ10 among dialysis patients results in improvement in clinical outcomes such as rates of infection, hospitalization, cardiovascular events, and mortality.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

CKY would like to acknowledge the Norman S. Coplon Extramural Grant Program by Satellite Healthcare, a not-for-profit renal care provider. The authors would like to gratefully acknowledge Bret A. Lynch, Jerry Gillick, RPh, and Deb Schaller, RPh, for their assistance with formulating and compounding the placebo wafer.

Support: This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, including National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine R21 AT004265 and R21 AT3844, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases T32 DK007467 and K24 DK62849, National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences KL2 TR000421 and UL1 TR000445, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences P30 ES000267, and National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute R01 HL070938. This word was additionally supported by an unrestricted gift from the Northwest Kidney Centers to the Kidney Research Institute. The study funders had no role in study design; collection, analysis, or interpretation of data; writing the report; or the decision to submit the report for publication.

Footnotes

Financial disclosure: Matthew Rivara: None. Catherine Yeung: None. Cassianne Robinson-Cohen: None. Brian Phillips: None. John Ruzinski: None. Denise Rock: None. Lori Linke: None. Danny Shen: None. Alp Ikizler: None. Jonathan Himmelfarb: None.

Contributions: Research idea and study design: TI, JH, CKY; data acquisition: LL, JR, DR, CKY, BRP, DDS; data analysis/interpretation: all authors; statistical analysis: MBR, CRC; supervision or mentorship: TI, JH. Each author contributed important intellectual content during manuscript drafting or revision and accepts accountability for the overall work by ensuring that questions pertaining to the accuracy or integrity of any portion of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. MBR takes responsibility that this study has been reported honestly, accurately, and transparently; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned and registered have been explained.

References

- 1.Saran R, Li Y, Robinson B, et al. US Renal Data System 2014 Annual Data Report: Epidemiology of Kidney Disease in the United States. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;65(6 Suppl 1):A7. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Longenecker JC, Coresh J, Powe NR, et al. Traditional Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors in Dialysis Patients Compared with the General Population: The CHOICE Study. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13(7):1918–1927. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000019641.41496.1e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheung AK, Sarnak MJ, Yan G, et al. Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risks in chronic hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2000;58(1):353–362. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00173.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Himmelfarb J, Stenvinkel P, Ikizler TA, Hakim RM. The elephant in uremia: Oxidant stress as a unifying concept of cardiovascular disease in uremia. Kidney Int. 2002;62(5):1524–1538. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00600.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stenvinkel P, Diczfalusy U, Lindholm B, Heimbürger O. Phospholipid plasmalogen, a surrogate marker of oxidative stress, is associated with increased cardiovascular mortality in patients on renal replacement therapy. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2004;19(4):972–976. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfh035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Himmelfarb J, McMenamin ME, Loseto G, Heinecke JW. Myeloperoxidase-catalyzed 3-chlorotyrosine formation in dialysis patients. Free Radic Biol Med. 2001;31(10):1163–1169. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(01)00697-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Annuk M, Zilmer M, Lind L, Linde T, Fellström B. Oxidative Stress and Endothelial Function in Chronic Renal Failure. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2001;12(12):2747–2752. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V12122747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ikizler TA, Morrow JD, Roberts LJ, et al. Plasma F2-isoprostane levels are elevated in chronic hemodialysis patients. Clin Nephrol. 2002;58(3):190–197. doi: 10.5414/cnp58190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rivara M, Ikizler TA, Ellis C, Mehrotra R, Himmelfarb J. Association of plasma F2-isoprostanes and isofurans concentrations with erythropoiesis-stimulating agent resistance in maintenance hemodialysis patients. BMC Nephrol. 2015;16:79. doi: 10.1186/s12882-015-0074-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fessel JP, Jackson Roberts L. Isofurans: novel products of lipid peroxidation that define the occurrence of oxidant injury in settings of elevated oxygen tension. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2004;7(1–2):202–209. doi: 10.1089/ars.2005.7.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alkazemi D, Egeland GM, Roberts LJ, Kubow S. Isoprostanes and isofurans as non-traditional risk factors for cardiovascular disease among Canadian Inuit. Free Radic Res. 2012;46(10):1258–1266. doi: 10.3109/10715762.2012.702900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ramos LF, Shintani A, Ikizler TA, Himmelfarb J. Oxidative Stress and Inflammation Are Associated with Adiposity in Moderate to Severe CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19(3):593–599. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007030355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mortensen SA, Rosenfeldt F, Kumar A, et al. The effect of coenzyme Q10 on morbidity and mortality in chronic heart failure: results from Q-SYMBIO: a randomized double-blind trial. JACC Heart Fail. 2014;2(6):641–649. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2014.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fotino AD, Thompson-Paul AM, Bazzano LA. Effect of coenzyme Q10 supplementation on heart failure: a meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;97(2):268–275. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.112.040741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lim SC, Lekshminarayanan R, Goh SK, et al. The effect of coenzyme Q10 on microcirculatory endothelial function of subjects with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Atherosclerosis. 2008;196(2):966–969. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2007.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hamilton SJ, Chew GT, Watts GF. Coenzyme Q10 improves endothelial dysfunction in statin-treated type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(5):810–812. doi: 10.2337/dc08-1736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mehmetoglu I, Yerlikaya FH, Kurban S, Erdem SS, Tonbul Z. Oxidative stress markers in hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis patients, including coenzyme Q10 and ischemia-modified albumin. Int J Artif Organs. 2012;35(3):226–232. doi: 10.5301/ijao.5000078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Claessens AJ, Yeung CK, Risler LJ, Phillips BR, Himmelfarb J, Shen DD. Rapid and sensitive analysis of reduced and oxidized coenzyme Q10 in human plasma by ultra performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry and application to studies in healthy human subjects. Ann Clin Biochem. 2015;53(Pt 2):265–273. doi: 10.1177/0004563215593097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Milne GL, Gao B, Terry ES, Zackert WE, Sanchez SC. Measurement of F2- isoprostanes and isofurans using gas chromatography–mass spectrometry. Free Radic Biol Med. 2013;59:36–44. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.09.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morrow JD. Quantification of isoprostanes as indices of oxidant stress and the risk of atherosclerosis in humans. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25(2):279–286. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000152605.64964.c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.White IR, Royston P, Wood AM. Multiple imputation using chained equations: Issues and guidance for practice. Stat Med. 2011;30(4):377–399. doi: 10.1002/sim.4067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rubin DB. Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys. Hoboken, N.J: Wiley-Interscience; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Little RJ, D’Agostino R, Cohen ML, et al. The Prevention and Treatment of Missing Data in Clinical Trials. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(14):1355–1360. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr1203730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hopke PK, Liu C, Rubin DB. Multiple imputation for multivariate data with missing and below-threshold measurements: time-series concentrations of pollutants in the Arctic. Biometrics. 2001;57(1):22–33. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2001.00022.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Madmani ME, Yusuf Solaiman A, Tamr Agha K, et al. Coenzyme Q10 for heart failure. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;6:CD008684. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008684.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Young JM, Florkowski CM, Molyneux SL, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover study of coenzyme Q10 therapy in hypertensive patients with the metabolic syndrome. Am J Hypertens. 2012;25(2):261–270. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2011.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ferrante KL, Shefner J, Zhang H, et al. Tolerance of high-dose (3,000 mg/day) coenzyme Q10 in ALS. Neurology. 2005;65(11):1834–1836. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000187070.35365.d7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huntington Study Group Pre2CARE Investigators. Hyson HC, Kieburtz K, et al. Safety and tolerability of high-dosage coenzyme Q10 in Huntington’s disease and healthy subjects. Mov Disord Off J Mov Disord Soc. 2010;25(12):1924–1928. doi: 10.1002/mds.22408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Macunluoglu B, Kaya Y, Atakan A, et al. Serum coenzyme Q10 levels are associated with coronary flow reserve in hemodialysis patients. Hemodial Int. 2013;17(3):339–345. doi: 10.1111/hdi.12001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yeung CK, Billings FT, Claessens AJ, et al. Coenzyme Q10 dose-escalation study in hemodialysis patients: safety, tolerability, and effect on oxidative stress. BMC Nephrol. 2015;16:183. doi: 10.1186/s12882-015-0178-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Granata S, Zaza G, Simone S, et al. Mitochondrial dysregulation and oxidative stress in patients with chronic kidney disease. BMC Genomics. 2009;10(1):1–13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-10-388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yazdi PG, Moradi H, Yang J-Y, Wang PH, Vaziri ND. Skeletal muscle mitochondrial depletion and dysfunction in chronic kidney disease. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2013;6(7):532–539. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eckardt K-U, Bernhardt WW, Weidemann A, et al. Role of hypoxia in the pathogenesis of renal disease. Kidney Int. 2005;68(S99):S46–S51. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.09909.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sluimer JC, Gasc J-M, van Wanroij JL, et al. Hypoxia, hypoxia-inducible transcription factor, and macrophages in human atherosclerotic plaques are correlated with intraplaque angiogenesis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51(13):1258–1265. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Onur S, Niklowitz P, Jacobs G, Lieb W, Menke T, Döring F. Association between serum level of ubiquinol and NT-proBNP, a marker for chronic heart failure, in healthy elderly subjects. BioFactors. 2015;41(1):35–43. doi: 10.1002/biof.1198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alehagen U, Johansson P, Björnstedt M, Rosén A, Dahlström U. Cardiovascular mortality and N-terminal-proBNP reduced after combined selenium and coenzyme Q10 supplementation: A 5-year prospective randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial among elderly Swedish citizens. Int J Cardiol. 2013;167(5):1860–1866. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2012.04.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shults CW, Oakes D, Kieburtz K, et al. Effects of coenzyme Q10 in early Parkinson disease: evidence of slowing of the functional decline. Arch Neurol. 2002;59(10):1541–1550. doi: 10.1001/archneur.59.10.1541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.The Parkinson Study Group QE3 Investigators. A randomized clinical trial of high-dosage coenzyme q10 in early parkinson disease: No evidence of benefit. JAMA Neurol. 2014;71(5):543–552. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Morrow JD. The isoprostanes: their quantification as an index of oxidant stress status in vivo. Drug Metab Rev. 2000;32(3–4):377–385. doi: 10.1081/dmr-100102340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kadiiska MB, Gladen BC, Baird DD, et al. Biomarkers of Oxidative Stress Study II: Are oxidation products of lipids, proteins, and DNA markers of CCl4 poisoning? Free Radic Biol Med. 2005;38(6):698–710. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Montuschi P, Barnes P, Roberts LJ. Insights into oxidative stress: the isoprostanes. Curr Med Chem. 2007;14(6):703–717. doi: 10.2174/092986707780059607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.