Abstract

Introduction

Cross-sectional research has found that young men who have sex with men (YMSM) are more likely to engage in heavy drinking and to have higher rates of marijuana and other illicit drug use compared to their heterosexual peers, but considerably less is known about their patterns of substance use over time.

Methods

In this study, we combined two longitudinal samples of racially diverse YMSM (N=552) and modeled their substance use trajectories from late-adolescence to young adulthood, including their frequency of alcohol use, frequency of marijuana use, and poly-drug use, using piecewise latent curve growth modeling to model change from ages 17–21 and change from ages 22–24.

Results

We found that all three substance use behaviors increased linearly over the adolescent-to-adult transition. The trajectories for all three substance use behaviors were significantly correlated from ages 17–21. Black YMSM had significantly lower growth from ages 17–21 in alcohol, marijuana, and poly-drug use compared to White YMSM. Hispanic/Latino YMSM had significantly higher growth from ages 22–24 in alcohol use but significantly lower growth in poly-drug use compared to White YMSM. YMSM with higher alcohol frequency slopes and YMSM with higher marijuana use slopes were more likely to have alcohol-related and marijuana-related problems, respectively, at the last wave of the study.

Conclusions

The results of the present study suggest that the transition from adolescence to adulthood for YMSM is a time of increasing and co-varying substance use and may be a critical period for substance use behaviors to grow into substance use problems.

Keywords: YMSM, alcohol, marijuana, substance use, longitudinal, problems

1. Introduction

The transition from adolescence to young adulthood is a critical period for understanding patterns of alcohol, marijuana, and illicit drug use (Schulenberg et al., 2001; Schulenberg and Maggs, 2002). This is especially true for young men who have sex with men (YMSM), who initiate alcohol use at younger ages (Corliss et al., 2008), have a higher prevalence of heavy drinking (Hughes and Eliason, 2002; Talley et al., 2014), and have higher rates of illicit drug use compared to their heterosexual peers (Marshal et al., 2008; Newcomb et al., 2014a).

The prevalence of substance use behaviors among YMSM varies depending on one’s racial/ethnic background and sexual orientation. Evidence suggests that Black YMSM are less likely to binge drink (Newcomb et al., 2012; Newcomb et al., 2014b; Wong et al., 2008) and engage in illicit drug use compared to White YMSM (Clatts et al., 2005; Kipke et al., 2007; Newcomb et al., 2014a; Newcomb et al., 2014b; Wong et al., 2010). There is similar evidence to suggest that YMSM that identify as Latino/Hispanic engage in less illicit drug use compared to non-Latino Whites (Newcomb et al., 2014a; Newcomb et al., 2014b; Warren et al., 2008). Young people who identify as bisexual have also been found to have higher rates of illicit drug use compared to those identifying as gay or heterosexual (Greenwood et al., 2001; Marshal et al., 2008; Newcomb et al., 2014a).

Cross-sectional prevalence rates are informative in illustrating the increased risks faced by YMSM and subgroups within the YMSM population, but they do not inform how substance use behaviors develop and change during the transition from adolescence to adulthood. Lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) adolescents have been found to escalate their alcohol use more rapidly during the transition to adulthood compared to their heterosexual counterparts (Marshal et al., 2009). YMSM, specifically, have been shown to have a greater increase in alcohol consumption during this transition compared to their heterosexual male peers (Dermody et al., 2014; Hatzenbuehler et al., 2008; Talley et al., 2010) and sexual minority women (Dermody et al., 2014; Newcomb et al., 2012).

Research on longitudinal change in marijuana and illicit drug use with YMSM has been sparse compared to the number of studies addressing change in alcohol use. Halkitis and colleagues (2014) followed YMSM at ages 18–19 for eighteen months and found that not only did YMSM increase in alcohol use over time, but that they also increased in marijuana and illicit drug use (defined in this study as cocaine, ecstasy, GHB, ketamine, heroin, rohypnol, and methamphetamine use) as well. These findings are in line with what has typically been found with heterosexual male populations (Chen and Kandel, 1995; Kandel and Logan, 1984). Given the general lack of research on substance use trajectories among YMSM, there is a need for additional studies that address trajectories of marijuana and illicit drug use.

Equally unexplored in YMSM communities are the prevalence rates of problematic substance use, such as an inability to discontinue using a substance or an inability to maintain work or social roles because of alcohol or marijuana use. Substance use problems indicate the degree to which substance use is negatively impacting someone’s life, as opposed to the quantity and frequency of use. Research on alcohol-related problems with adult men have at times found higher rates of problems for adult MSM compared to heterosexual men (Knowlton et al., 1994) but at other times found no differences (Drabble et al., 2005; Mackesy-Amiti et al., 2009). Similar results have been found for marijuana-related problems with some studies finding higher rates of problems for MSM (Cochran et al., 2004) and other studies finding no differences (Mackesy-Amiti et al., 2009). Further, research on alcohol problems in MSM has not found evidence of racial differences (Knowlton et al., 1994; Stall et al., 2001) but there is some evidence that marijuana-related problems may be higher in non-White participants (Mackesy-Amiti et al., 2009).

It is also important to consider the developmental context in which these behaviors occur when examining trajectories of change. Young adulthood is characterized not only by notably high rates of substance use, but also identity exploration, instability and transitional life events (Arnett, 2005; Wong et al., 2013). Research on contextual changes and substance use behavior in YMSM has shown that moving away from home is associated with increased substance use, while employment functions as a protective factor as YMSM age (Wong et al., 2013). Studies with heterosexuals are consistent with YMSM findings that living with parents protects against increased substance use in young adulthood (Bachman et al., 1997; White et al., 2008). Furthermore, reaching age 21 (i.e., the legal age to purchase alcoholic beverages and enter drinking venues) represents an important transition that may impact trajectories of alcohol and drug use by exposing YMSM to social environments (e.g., bars, clubs) in which alcohol and drug use are more common.

1.1. Current Study

The purpose of the present study was to examine trajectories of alcohol and substance use in a racially diverse sample of YMSM in order to more fully understand how these behaviors change across the transition from late adolescence to young adulthood. We hypothesize that alcohol, marijuana, and illicit drug use would increase over this period, would co-vary with one another over time, and predict higher levels of alcohol-related and marijuana related problem behaviors at a later time point. We also predict that trajectories of substance use behaviors will be different from ages 17–21 and 22–24, specifically that growth in use will be higher during the 17–21 age period.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedures

Participants came from RADAR, an ongoing longitudinal cohort study of YMSM that aims to understand multilevel influences on HIV risk and substance use. This large cohort is being formed by merging three existing studies of YMSM: two longitudinal studies of YMSM (Project Q2 and Crew 450) and a cross-sectional adolescent-extension of CDC’s National HIV Behavioral Surveillance, called ChiGuys. Because the aims of the current analyses were to understand developmental trajectories of alcohol and drug use, we utilized an analytic sample of only those YMSM from Project Q2 and Crew 450. These participants had up to 8 waves of longitudinal data and completed the baseline visit for the RADAR study (up to 9 waves of data total).

Project Q2 was a longitudinal study of the health and development of LGBT youth that included 117 YMSM (Mustanski et al., 2010). YMSM in Project Q2 included individuals who were assigned male at birth, between 16 and 20 years old at baseline interview, and identified as gay, bisexual, questioning, or endorsed same-sex attraction. Data collection began in 2007 and continued with 8 waves at 6 to 18 month intervals depending on the wave. Crew 450 (N=450) was a longitudinal study examining a syndemic of psychosocial conditions associated with HIV among YMSM (Garofalo et al., 2016; Newcomb et al., 2014b). Crew 450 eligibility criteria included being born male, English speaking, between 16 and 20 years old, and had a previous sexual encounter with a man or identified as gay or bisexual. Data collection began in December 2009 and participants were followed for up to 8 waves of data collection at 6 month intervals. There were 15 participants who were enrolled in both Project Q2 and Crew 450. For those participants, data was taken from the study where the participant completed the most waves (final analytic N = 552). Baseline visits for the RADAR study (i.e., the final time point for the current analyses) occurred between 2015 and 2016. Each study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) with a waiver of parental permission for participants under 18 years under 45 CFR 46, 408(c) (Mustanski, 2011). Participants provided written informed consent/assent, and mechanisms to protect participant confidentiality were utilized (i.e., a federal certificate of confidentiality).

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Demographics

The demographics questionnaire at each time point assessed participant age, birth sex, race/ethnicity, self-reported sexual orientation, employment status, student status, and living situation.

2.2.2. Alcohol Use

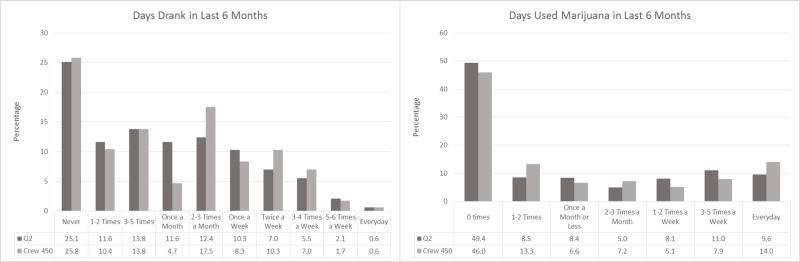

In Project Q2, participants were asked to report the number of days in the last 6 months that they had consumed alcohol (one item, range: 0–180). In Crew 450, participants were given the same question but were given the response options “Never”, “1 or 2 times in the past 6 months”, “3 to 5 times in the past 6 months”, “Once a month”, “2 to 3 times a month”, “Once a week”, “Twice a week”, “3 to 4 times a week”, “5 to 6 times a week” and “Everyday” (range: 0–9). Project Q2 responses were recoded to fit within the Crew 450 response options. We chose to recode the Project Q2 data in this manner because 1) Crew 450 represented over 80% of the full sample and 2) the Crew 450 response options, which each represented a broad range of possible values, did not lend themselves to a straightforward numeric transformation. In order to transform the Project Q2 data, we assumed that number of days participants consumed alcohol was evenly distributed over the six month period. For instance, if a participant responded that they consumed alcohol on 6 days in the last six months, we coded that person as “Once a month” on the Crew 450 scale. The distribution of values for Project Q2 participants was similar to the Crew 450 distribution after the recode (see Figure 1). In both studies participants were asked, “When you drank, how many drinks did you have?,” with the response options “0 drinks”, “1 drink”, “2 drinks”, “3 drinks”, “4 drinks”, “5 drinks”, and “6 or more drinks” (range: 0–6). Alcohol quantity-frequency was created at each wave by multiplying response on the 0–9 ordinal scale measuring days of use by the response to the 0–6 scale asking the number of drinks (range: 0–54).

Figure 1.

Comparison of Recoded Q2 and Crew 450 Substance Use Data for All Waves

At the final time point, the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT), a 10-item screening tool assessing consumption, behaviors, and problems related to alcohol in the past 6 months, was administered (Saunders et al., 1993). Participants who score a sum of 8–15 are considered to have a hazardous level of alcohol-related problems and for those who score 16 or higher, they are considered to have a disordered level of alcohol-related problems that may indicate a possible alcohol dependence disorder. We calculated a mean score of the AUDIT at the final time point.

2.2.3. Marijuana Use

In Project Q2, participants were asked to report the number of days in the last 6 months that they had used marijuana (one item, range: 0–180). In Crew 450, participants were given the same question but were given the response options “0 times”, “1 or 2 times in the past 6 months”, “Once a month or less (3–6 times in the past 6 months)”, “2 or 3 times a month”, “1 or 2 times a week”, “3 to 5 times a week”, and “Everyday or almost everyday.” Project Q2 responses were recoded to fit within the Crew 450 response options for the same reasons that Project Q2 responses to alcohol items were recoded. The distribution of values were similar for each cohort after the recode (see Figure 1). This item was used as our measure of marijuana frequency (range: 0–6).

At the final time point, problematic cannabis use was assessed using the CUDIT-R (Adamson et al., 2010). This screening tool includes 8 questions related to problems, dependence, and psychological features of cannabis use. Sum scores between 8–11 indicate a hazardous level of marijuana-related problems. Scores of 12 or above indicate that a participant may have a cannabis use disorder. We utilized computed mean scores of the CUDIT-R at the final time point.

2.2.4. Poly-Drug Use

Participants in both Project Q2 and Crew 450 were asked about their use of cocaine, methamphetamines, and ecstasy in the previous six months. We created a sum score based on the number of illicit drugs participants endorsed using in that period (range: 0–3).

2.3. Statistical Analyses

We ran latent growth curve models in MPlus to assess change in substance use behaviors. MPlus uses maximum likelihood to adjust for missing data. In order to account for the fact that participants had their first time point at different ages and had different assessment schedules based on whether they originated from Project Q2 or Crew 450, we used individually-varying time scores in MPlus to account for participants’ varying assessment schedules (Mehta and West, 2000; Sterba, 2014). Time scores are used as person-specific factor loadings that account for the differences in interview schedule and age. Time scores were centered at age 17. To be included in our analyses, each age had to be represented by at least 100 participants who provided data in that year (for instance, 102 participants reported data at a wave where they were age 17). For this reason, waves where participants were outside of the 17–24 age range were not included. Model fit was assessed using Loglikelihood, Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC). For all three measures, lower values indicate improved fit. Initially we tested for non-linear effects within the growth models but dropped those effects because they were not significant. In order to understand how the rate of growth might not be the same from ages 17 to 24, we also tested piecewise latent growth models that included the slope from age 17 to 21 and the slope from age 22 to 24. To test the piecewise growth models, we created individually-varying loadings for each slope using Sterba’s (2014) SAS macro for creating individually-varying time scores for piecewise models.

We followed up the individual latent growth models by modeling all three of the substance use behaviors together in a single parallel process model. In a parallel process model, multiple simultaneous behaviors are modeled together in order to understand associations between growth across those behaviors. We tested for these effects within a single parallel process model that included change in alcohol, marijuana, and poly-drug use. We then proceeded to add demographic characteristics as predictors to the parallel process model, including race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, and study origination cohort. Cohort effects were not significant in any of the models and were dropped. Race was included as three separate dummy codes (Black, Latino/Hispanic, and other race) with White as the reference group. Sexual orientation was coded as two separate dummy codes (bisexual and other sexual orientation) with gay-identifying participants as the reference group.

For the last parallel process model, we took the parallel process with demographics model and included the AUDIT and CUDIT as outcomes to see if change in substance use was associated with alcohol and marijuana problems at the last wave of data collection.

To test the effects of predictors that were variable over time, we modeled change in substance use using a multilevel model conducted in MPlus. The baseline demographic factors added in previous models (race/ethnicity and sexual orientation) were included as between-person effects. The new predictors to this model, student status, employment status, and whether participant lived with a parent at that wave were modeled as within-person and between-person effects. We chose to look at these predictors within a multilevel framework because of the challenge of interpreting time-varying predictors in parallel process models that adjust for individually-varying assessment schedules and for the opportunity to determine whether these predictors fostered within-person change or between-person differences.

3. Results

3.1. Demographics

The combined Project Q2 and Crew 450 sample had an average age of 18.92 years (SD = 1.34) at baseline. By the last wave, the average age was 23.59 years (SD = 1.97). Participants completed a mean of 5.84 (SD = 2.25) waves of data collection. The retention for both cohorts was high over the course of each study (Beck et al., 2015; Newcomb et al., 2012; Newcomb and Mustanski, 2015; Newcomb et al., 2015). Of the 552 participants at baseline, 35.14% (N=194) participated in the last wave and contributed outcome data. One major factor that contributed to the large drop in retention from the first wave to the last wave was that only a randomized half of Crew 450 participants were eligible for RADAR (data from which were used for the final wave). Participants originally recruited into Project Q2 represented 21.2% of the sample (N = 117) and 78.8% (N = 435) were originally recruited into Crew 450. In terms of race/ethnicity, 284 participants (51.5%) identified as African American/Black, 104 (18.8%) as Hispanic/Latino, 102 (18.5%) as White, and 62 (11.2%) as either Asian/Pacific Islander, Native American, or “other.” Three hundred and ninety-six participants (71.9%) identified as gay, 120 (21.8%) as bisexual, and 36 (6.5%) as straight/questioning or “other.” At baseline, 388 (70.3%) identified as students, 173 (31.3%) said they were employed, and 294 (53.3%) answered that they lived with a parent.

The sample N, broken down by age, is presented in Table 1, along with descriptives for alcohol, marijuana, and poly-drug use at each age. Of the three substances used to measure poly-drug use, methamphetamines were endorsed less often at age 17 (only 2.0% reported use in the previous six months) compared to cocaine (4.9%) and ecstasy (4.9%). For the participants who provided data at the last wave, 18.6% met the criteria for hazardous alcohol use on the AUDIT and 5.2% for disordered alcohol use. In terms of CUDIT scores, 13.4% met the criteria for hazardous marijuana use and 21.1% for disordered marijuana use.

Table 1.

Substance Use by Age

| Age | N | Data Points | Alcohol Quantity- Frequency |

Marijuana Frequency |

Poly-Drug Use | Used Cocaine |

Used Meth | Used Ecstasy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | % (N) | % (N) | % (N) | |||

| 17 | 102 | 146 | 6.99 (10.24) | 1.77 (2.20) | 0.10 (.37) | 4.9 (5) | 2.0 (2) | 4.9 (5) |

| 18 | 183 | 284 | 8.37 (11.05) | 1.73 (2.15) | 0.09 (.37) | 4.9 (9) | 0.5 (1) | 6.0 (11) |

| 19 | 308 | 491 | 10.15 (11.68) | 1.85 (2.22) | 0.12 (.43) | 6.8 (21) | 1.6 (5) | 8.4 (26) |

| 20 | 413 | 660 | 11.39 (11.87) | 2.12 (2.30) | 0.19 (.52) | 9.2 (38) | 2.4 (10) | 11.6 (48) |

| 21 | 393 | 640 | 11.27 (11.86) | 2.04 (2.33) | 0.15 (.47) | 7.1 (28) | 2.0 (8) | 10.2 (40) |

| 22 | 311 | 448 | 11.24 (11.50) | 1.77 (2.27) | 0.18 (.53) | 8.4 (26) | 1.3 (4) | 8.4 (26) |

| 23 | 217 | 263 | 11.03 (11.68) | 1.63 (2.22) | 0.16 (.45) | 6.0 (13) | 1.4 (3) | 7.4 (16) |

| 24 | 131 | 146 | 9.33 (10.14) | 1.80 (2.20) | 0.23 (.60) | 8.4 (11) | 3.8 (5) | 6.1 (8) |

Note: N indicates number of participants with data at that age, Data Points indicate the number of instances at that age (participants could provide data twice at a given age because of the six month gap between some surveys).

Results of a chi-square test revealed that participants in Project Q2 were more likely to complete the last wave and have outcome data compared to Crew 450 participants (53.0% vs. 31.4%; χ2(1) = 18.63, p < .001). They also had more waves of data (Std. Beta = .26, p < .001). These differences were no longer significant when Crew 450 participants who were not randomized into RADAR were dropped from the comparisons, which suggested that the randomization was responsible for the differences. Participants with higher baseline poly-drug use (Std. Beta = −.13, p < .01) and higher baseline marijuana use (Std. Beta = −.10, p < .05) had fewer waves of data. There were no differences based on race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, or baseline age.

3.2. Individual Latent Growth Curves

The fit indices for the invididual latent growth curves for substance use behaviors are in Table 2. For all three substance use behaviors, the latent growth curve models with intercept and piecewise slopes provided better fit to the data compared to the intercept only and intercept + slope models.

Table 2.

Latent Growth Curve Fit Statistics

| Intercept Only | Intercept + Slope | Intercept + Piecewise Slopes | Intercept, Piecewise Slopes + Covariates | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol Q-F | |||||

| Loglikelihood | −9132.17 | −9107.82 | −8649.39 | - | |

| AIC | 18286.33 | 18243.64 | 17334.78 | - | |

| BIC | 18298.84 | 18259.56 | 17355.18 | - | |

|

| |||||

| Marijuana Frequency | |||||

| Loglikelihood | −5004.52 | −4953.35 | −4645.42 | - | |

| AIC | 10031.03 | 9934.69 | 9326.84 | - | |

| BIC | 10078.48 | 9995.08 | 9404.42 | - | |

|

| |||||

| Poly-Drug Use | |||||

| Loglikelihood | −1643.10 | −1592.24 | −1422.89 | - | |

| AIC | 3308.20 | 3212.47 | 2881.76 | - | |

| BIC | 3355.65 | 3272.86 | 2959.35 | - | |

|

| |||||

| Parallel Process | |||||

| Loglikelihood | −15638.10 | −15480.95 | −14513.30 | −14392.64 | |

| AIC | 31348.20 | 31069.90 | 29188.61 | 29037.28 | |

| BIC | 31389.20 | 31302.83 | 29280.58 | 29180.12 | |

Alcohol Q-F = Alcohol Quantity-Frequency

The individual latent growth curves for alcohol, marijuana, and poly-drug use are presented in Table 3. The mean value for the alcohol intercept was significant (Beta = 7.34, SE = 1.21). The alcohol slope from ages 17–21 was significant (Beta = 1.00, SE = 0.34) and showed an increase in alcohol quantity-frequency from late adolescence into early adulthood. The slope from ages 22–24 was not significant (Beta = 0.02, SE = 0.21). The mean for the marijuana intercept (Beta = 1.52, SE = 0.21) and the 17–21 slope (Beta = 0.15, SE = 0.06) were both significant and suggested that marijuana frequency increased over time into early adulthood. The 22–24 slope was not significant (Beta = −0.06, SE = 0.05). The 17–21 slope for poly-drug use was significant (Beta = 0.04, SE = 0.01). Based on the slope, poly-drug use increased over the late adolescent period. The 22–24 poly-drug use slope was not significant (Beta = 0.01, SE = 0.01).

Table 3.

Latent Growth Curve Models

| Means | Variance | AI | AS17 | AS22 | MI | MS17 | MS22 | PI | PS17 | PS22 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||

| Beta (SE) | Beta (SE) | Beta (SE) | Beta (SE) | Beta (SE) | Beta (SE) | Beta (SE) | Beta (SE) | Beta (SE) | Beta (SE) | Beta (SE) | |

| Individual Slope Models | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Alcohol Intercept | 7.34 (1.21)*** | 126.60 (49.14)* | - | −22.87 (13.16) | −13.98 (4.42)** | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Alcohol Slope 17–21 | 1.00 (.34)** | 9.93 (3.78)** | −22.87 (13.16) | - | 1.84 (1.09) | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Alcohol Slope 22–24 | .02 (.21) | 3.03 (.97)** | −13.98 (4.42)** | 1.84 (1.09) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

|

| |||||||||||

| Marijuana Intercept | 1.52 (.21)*** | 6.80 (1.71)*** | - | - | - | - | −1.46 (.50)** | −.77 (.36)* | - | - | - |

| Marijuana Slope 17–21 | .15 (.06)* | .59 (.16)*** | - | - | - | −1.46 (.50)** | - | .08 (.10) | - | - | - |

| Marijuana Slope 22–24 | −.06 (.05) | .35 (.09)*** | - | - | - | −.77 (.36)* | .08 (.10) | - | - | - | - |

|

| |||||||||||

| Poly Drug Intercept | .00 (.04) | .12 (.08) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | −.04 (.04) | −.02 (.03) |

| Poly Drug Slope 17–21 | .04 (.01)*** | .03 (.01) | - | - | - | - | - | - | −.04 (.04) | - | .00 (.01) |

| Poly Drug Slope 22–24 | .01 (.01) | .02 (.01)** | - | - | - | - | - | - | −.02 (.03) | .00 (.01) | - |

|

| |||||||||||

| Parallel Process Model | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Alcohol Intercept | 6.73 (1.11)*** | 173.22 (41.87)*** | - | −39.27 (10.99)*** | −13.24 (4.64)** | 27.92 (6.96)*** | −5.32 (1.86)** | −2.30 (1.19)* | 2.78 (1.07)** | −.46 (.37) | .73 (.39) |

| Alcohol Slope 17–21 | 1.16 (.33)*** | 15.52 (3.05)*** | −39.27 (10.99)*** | - | −7.08 (2.06)** | 1.89 (.55)** | .34 (.32) | −.83 (.29)** | .30 (.10)** | −.17 (.09) | |

| Alcohol Slope 22–24 | −.01 (.21) | 4.40 (1.07)*** | −13.24 (4.64)** | 1.06 (1.19) | - | −1.08 (.91) | .10 (.25) | .60 (.22)** | −.56 (.19)** | .08 (.06) | .02 (.05) |

| Marijuana Intercept | 1.53 (.22)*** | 7.68 (1.67)*** | 27.92 (6.96)*** | −7.08 (2.06)** | −1.08 (.91) | - | −1.70 (.48)*** | −.79 (.30)** | .56 (.21)** | −.11 (.08) | −.01 (.06) |

| Marijuana Slope 17–21 | .15 (.06)* | .65 (.14)*** | −5.32 (1.86)** | 1.89 (.55)** | .10 (.25) | −1.70 (.48)*** | - | .09 (.08) | −.16 (.05)** | .06 (.02)** | .01 (.02) |

| Marijuana Slope 22–24 | −.08 (.05) | .34 (.08)*** | −2.30 (1.19)* | .34 (.32) | .60 (.22)** | −.79 (.30)** | .09 (.08) | - | −.11 (.04)** | .01 (.01) | .03 (.01)** |

| Poly Drug Intercept | .02 (.04) | .17 (.05)*** | 2.78 (1.07)** | −.83 (.29)** | −.56 (.19)** | .56 (.21)** | −.16 (.05)** | −.11 (.04)** | - | −.06 (.02)*** | .00 (.01) |

| Poly Drug Slope 17–21 | .04 (.01)** | .03 (.01)*** | −.46 (.37) | .30 (.10)** | .08 (.06) | −.11 (.08) | .06 (.02)** | .01 (.01) | −.06 (.02)*** | - | −.01 (.00) |

| Poly Drug Slope 22–24 | .02 (.01)* | .02 (.01)** | .73 (.39) | −.17 (.09) | .02 (.05) | −.01 (.06) | .01 (.02) | .03 (.01)** | .00 (.01) | −.01 (.00) | - |

Notes:

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001.

AI = Alcohol Intercept, AS17 = Alcohol Slope from 17–21, AS22 = Alcohol Slope from 22–24, MI = Marijuana Intercept, MS17 = Marijuana Slope from 17–21, MS22 = Marijuana Slope from 22–24, PI = Poly-drug Intercept, PS17 = Poly-drug Slope from 17–21, PS22 = Poly-drug Slope from 22–24

3.3. Substance Use Parallel Process Model

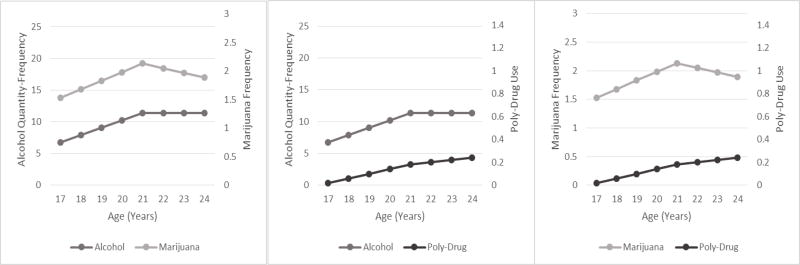

Results for the parallel process model for substance use behaviors are in Table 3 and Figure 2. Similar to the individual models, the parallel process model that included intercepts and piecewise slopes was a better fit compared to the intercept only and intercept + single slope models. Estimates for the intercepts and slopes were equivalent to what was found in the individual growth models with the exception that the 22–24 slope for poly-drug use was significant (Beta = 0.02, SE = 0.01) when all three substance use behaviors were modeled together. This suggested that when we controlled for marijuana frequency, alcohol quantity-frequency and the associations between the substance use behaviors, poly-drug use significantly increased over the period from ages 22–24 for this sample.

Figure 2.

Parallel Process Piecewise Model: Change in Substance Use Behaviors Over Time

Change over time in all three substance use behaviors from age 17 to 21 were significantly correlated. Increases in alcohol quantity-frequency were associated with increases in marijuana (Beta = 1.89, SE = 0.55) and poly-drug use (Beta = 0.30, SE = 0.10). Likewise, higher growth in marijuana frequency was associated with higher growth in poly-drug use (Beta = 0.06, SE = 0.02). There was a similar pattern for the slopes from ages 22 to 24. Increases in marijuana frequency were associated with higher increases in alcohol (Beta = 0.60, SE = 0.22) and poly-drug use (Beta = 0.03, SE = 0.01). However, the correlation between slopes for alcohol and poly-drug use was not significant (Beta = 0.02, SE = 0.05).

3.4. Effects of Demographic Characteristics on Parallel Process Latent Growth Factors

The effects of demographic characteristics on the substance use growth curves are presented in Table 4. The overall pattern of change in substance use behaviors over time stayed consistent after controlling for demographic factors. Participants who identified as Black had significantly lower growth in alcohol (Beta = −2.36, SE = 1.04), marijuana (Beta = −0.44, SE = 0.17), and poly-drug use (Beta = −0.11, SE = 0.04) compared to White participants from the ages of 17 to 21. Black participants also had lower growth in marijuana frequency from 22 to 24 compared to White participants (Beta = −0.25, SE = 0.12). Latino/Hispanic-identified participants had significantly higher growth in alcohol quantity-frequency from ages 22 to 24 compared to non-Latino White participants (Beta = 1.58, SE = 0.78), and significantly lower growth in poly-drug use over the same period (Beta = −0.09, SE = 0.05). Participants in the “other” race category had significantly lower growth in marijuana frequency at ages 17 to 21 compared to White participants (Beta = −0.41, SE = .21).

Table 4.

Latent Growth Curve Models

| Means | Variance | AI | AS17 | AS22 | MI | MS17 | MS22 | PI | PS17 | PS22 | AUDIT | CUDIT | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||||

| Beta (SE) | Beta (SE) | Beta (SE) | Beta (SE) | Beta (SE) | Beta (SE) | Beta (SE) | Beta (SE) | Beta (SE) | Beta (SE) | Beta (SE) | Beta (SE) |

Beta (SE) | |

| Parallel Process Model with Predictors | |||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||

| Alcohol Intercept | 8.74 (3.51)* | 173.90 (43.25)*** | - | −40.76 (11.61)*** | −12.43 (4.46)** | 29.18 (7.11)*** | −5.80 (1.88)** | −2.74 (1.14)* | 2.80 (1.09)* | −.48 (.38) | .54 (.37) | - | - |

| Alcohol Slope 17–21 | 2.58 (.97)** | 14.83 (3.29)*** | −40.76 (11.61)*** | - | .70 (1.15) | −7.16 (2.06)** | 1.90 (.55)** | .30 (.30) | −.83 (.29)** | .27 (.10)** | −.16 (.09) | ||

| Alcohol Slope 22–24 | −.29 (.49) | 4.00 (.94)*** | −12.43 (4.46)** | .70 (1.15) | - | −1.23 (.82) | .16 (.22) | .56 (.20)** | −.48 (.17)** | .06 (.05) | .04 (.05) | - | - |

| Marijuana –Intercept | 1.06 (.54)* | 7.54 (1.66)*** | 29.18 (7.11)*** | −7.16 (2.06)** | −1.23 (.82) | - | −1.64 (.47)** | −.86 (.27)** | .55 (.20)** | −.10 (.07) | −.01 (.06) | - | - |

| Marijuana Slope 17–21 | .40 (.15)** | .62 (.14)*** | −5.80 (1.88)** | 1.90 (.55)** | .16 (.22) | −1.64 (.47)** | - | .10 (.07) | −.16 (.05)** | .05 (.02)** | .00 (.02) | ||

| Marijuana Slope 22–24 | .16 (.09) | .32 (.07)*** | −2.74 (1.14)* | .30 (.30) | .56 (.20)** | −.86 (.27)** | .10 (.07) | - | −.09 (.04)** | .01 (.01) | .03 (.01)** | - | - |

| Poly Drug Intercept | −.06 (.12) | .17 (.04)*** | 2.80 (1.09)* | −.83 (.29)** | −.48 (.17)** | .55 (.20)** | −.16 (.05)** | −.09 (.04)** | - | −.06 (.02)*** | .00 (.01) | - | - |

| Poly Drug Slope 17–21 | .11 (.04)** | .03 (.01)*** | −.48 (.38) | .27 (.10)** | .06 (.05) | −.10 (.07) | .05 (.02)** | .01 (.01) | −.06 (.02)*** | - | −.01 (.00) | ||

| Poly Drug Slope 22–24 | .09 (.04)* | .02 (.01)** | .54 (.37) | −.16 (.09) | .04 (.05) | −.01 (.06) | .00 (.02) | .03 (.01)** | .00 (.01) | −.01 (.00) | - | - | - |

|

|

|||||||||||||

| Bisexual | - | - | .99 (2.70) | −.37 (.75) | −.83 (.54) | −.44 (.53) | .29 (.15)* | −.23 (.14) | .02 (.10) | .01 (.03) | −.02 (.02) | - | - |

| Other Sexual | |||||||||||||

| Orientation | - | - | −5.70 (4.32) | 2.52 (1.26)* | −.64 (.93) | −.45 (1.03) | .28 (.30) | −.25 (.20) | .09 (.14) | −.01 (.05) | .00 (.05) | - | - |

| Black | - | - | −2.40 (3.78) | −2.36 (1.04)* | .60 (.59) | .91 (.63) | −.44 (.17)* | −.25 (.12)* | .10 (.12) | −.11 (.04)** | −.07 (.04) | - | - |

| Hispanic | - | - | −1.45 (4.37) | −.99 (1.23) | 1.58 (.78)* | .19 (.69) | −.30 (.20) | −.18 (.12) | .07 (.14) | −.07 (.05) | −.09 (.05)* | - | - |

| Other Race | - | - | −2.60 (4.44) | −1.11 (1.30) | −.93 (.71) | .74 (.75) | −.41 (.21)* | −.26 (.15) | .10 (.19) | −.07 (.07) | .06 (.05) | - | - |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Parallel Process Model on Substance Use Problems | |||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||

| Alcohol Intercept | 8.53 (3.48)* | 179.88 (50.03)*** | - | −43.03 (13.80)** | −9.57 (3.78)* | 28.88 (7.15)*** | −5.66 (1.86)** | −3.26 (1.21)** | 2.82 (1.23)* | −.48 (.41) | .62 (.37) | .04 (.11) | −.09 (.09) |

| Alcohol Slope 17–21 | 2.66 (.95)** | 15.62 (3.96)*** | −43.03 (13.80)** | - | −.03 (1.02) | −6.94 (2.09)** | 1.83 (.55)** | .43 (.33) | −.85 (.35)* | .28 (.11)* | −.18 (.10) | .15 (.04)*** | −.10 (.05) |

| Alcohol Slope 22–24 | −.44 (.45) | 3.71 (1.10)** | −9.57 (3.78)* | −.03 (1.02) | - | −1.34 (.74) | .19 (.20) | .52 (.20)** | −.46 (.19)* | .05 (.06) | .03 (.05) | .05 (.18) | −.36 (.23) |

| Marijuana Intercept | 1.10 (.54)* | 7.71 (1.76)*** | 28.88 (7.15)*** | −6.94 (2.09)** | −1.34 (.74) | - | −1.69 (.51)** | −.79 (.27)** | .54 (.20)** | −.10 (.07) | .00 (.05) | .03 (.18) | .69 (.18)*** |

| Marijuana Slope 17–21 | .39 (.15)** | .64 (.15)*** | −5.66 (1.86)** | 1.83 (.55)** | .19 (.20) | −1.69 (.51)** | - | .09 (.07) | −.15 (.05)** | .05 (.02)** | .00 (.02) | −.17 (.23) | 1.34 (.32)*** |

| Marijuana Slope 22–24 | .17 (.09)* | .32 (.08)*** | −3.26 (1.21)** | .43 (.33) | .52 (.20)** | −.79 (.27)** | .09 (.07) | - | −.11 (.04)** | .01 (.02) | .03 (.01)* | .02 (.30) | 1.05 (.50)* |

| Poly Drug Intercept | −.10 (.12) | .18 (.05)*** | 2.82 (1.23)* | −.85 (.35)* | −.46 (.19)* | .54 (.20)** | −.15 (.05)** | −.11 (.04)** | - | −.06 (.02)*** | .00 (.01) | −.65 (4.66) | −.96 (4.08) |

| Poly Drug Slope 17–21 | .12 (.04)** | .03 (.01)*** | −.48 (.41) | .28 (.11)* | .05 (.06) | −.10 (.07) | .05 (.02)** | .01 (.02) | −.06 (.02)*** | - | −.01 (.01) | −.17 (10.24) | −1.16 (8.88) |

| Poly Drug Slope 22–24 | .08 (.04)* | .02 (.01)** | .62 (.37) | −.18 (.10) | .03 (.05) | .00 (.05) | .00 (.02) | .03 (.01)* | .00 (.01) | −.01 (.01) | - | .45 (6.64) | .51 (5.53) |

|

|

|||||||||||||

| Bisexual | - | - | 1.02 (2.70) | −.40 (.75) | −.67 (.53) | −.48 (.53) | .30 (.15)* | −.23 (.14) | .03 (.10) | .01 (.03) | −.02 (.02) | .02 (.20) | −.04 (.34) |

| Other Sexual | |||||||||||||

| Orientation | - | - | −5.41 (4.39) | 2.44 (1.27)* | −.69 (.92) | −.44 (1.03) | .28 (.30) | −.28 (.21) | .07 (.15) | .00 (.05) | −.01 (.05) | .19 (.62) | −.28 (.64) |

| Black | - | - | −1.88 (3.82) | −2.51 (1.05)* | .69 (.56) | .92 (.63) | −.44 (.17)* | −.26 (.12)* | .13 (.12) | −.12 (.04)** | −.07 (.04) | −.02 (.40) | .20 (.42) |

| Hispanic | - | - | −1.33 (4.34) | −1.04 (1.22) | 1.64 (.75)* | .16 (.70) | −.29 (.20) | −.20 (.12) | .09 (.14) | −.08 (.05) | −.09 (.05)* | .00 (.42) | .92 (.51) |

| Other Race | - | - | −2.48 (4.55) | −1.16 (1.32) | −.76 (.69) | .75 (.77) | −.41 (.22)* | −.25 (.15) | .17 (.20) | −.08 (.07) | −.05 (.05) | −.06 (.14) | −.05 (.43) |

Notes:

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001.

AI = Alcohol Intercept, AS17 = Alcohol Slope from 17–21, AS22 = Alcohol Slope from 22–24, MI = Marijuana Intercept, MS17 = Marijuana Slope from 17–21, MS22 = Marijuana Slope from 22–24, PI = Poly-drug Intercept, PS17 = Poly-drug Slope from 17–21, PS22 = Poly-drug Slope from 22–24

Bisexual participants reported higher growth in marijuana frequency from 17 to 21 compared to gay participants (Beta = 0.29, SE = 0.15). Participants in the “other” sexual orientation category reported higher growth in alcohol quantity-frequency from the ages 17 to 21 compared to gay participants (Beta = 2.52, SE = 1.26).

3.5. Effects of Latent Growth Factors on Alcohol and Marijuana Problems

Results for substance use factors predicting AUDIT and CUDIT scores are presented in Table 4. Higher growth in alcohol quantity-frequency from 17 to 21 was predictive of higher AUDIT scores (Beta = 0.15, SE = 0.04). There was no association between growth from 22 to 24 and AUDIT scores (Beta = 0.05, SE = 0.18).There were no associations between marijuana and poly-drug factors and AUDIT score. There were no significant differences on AUDIT scores based on sexual orientation or race/ethnicity.

Higher marijuana intercepts (Beta = 0.69, SE = 0.18), 17–21 slopes (Beta = 1.34, SE = 0.32), and 22–24 slopes (Beta = 1.05, SE = 0.50) were associated with higher CUDIT scores. None of the other substance use factors were significantly associated with CUDIT scores. There were no significant race/ethnicity or sexual orientation differences on the CUDIT.

3.6. Within-Person Predictors of Substance Use Growth Factors

Multilevel results looking at the effects of student status, employment status, and living with parents on change in substance use can be found in Table 5. We found no significant within-person differences in substance use behaviors based on student or employment status. There were also no within-person differences based on living with parents. This suggests that changes over time in these factors did not explain within-person change in alcohol, marijuana, or poly-drug use. Within-persons, all three substance use behaviors were significantly positively correlated.

Table 5.

Multilevel Model with Within- and Between-Person Predictors

| AQF | MF | PU | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| Beta (SE) | Beta (SE) | Beta (SE) | |||||||

| Within | |||||||||

| Currently Student | .10 (.46) | .09 (.08) | −.02 (.02) | ||||||

| Currently Employed | −.28 (.39) | −.12 (.08) | −.03 (.02) | ||||||

| Live with Parent | −.33 (.50) | .02 (.09) | .04 (.02) | ||||||

|

|

|||||||||

| Alcohol Quantity-Frequency | - | .93 (.32)** | .22 (.08)** | ||||||

| Marijuana Frequency | .93 (.32)** | - | .02 (.01)* | ||||||

| Poly Drug Use | .22 (.08)** | .02 (.01)* | - | ||||||

|

| |||||||||

| AI | AS17 | AS22 | MI | MS17 | MS22 | PI | PS17 | PS22 | |

|

| |||||||||

| Between | Beta (SE) | Beta (SE) | Beta (SE) | Beta (SE) | Beta (SE) | Beta (SE) | Beta (SE) | Beta (SE) | Beta (SE) |

|

|

|||||||||

| Alcohol Intercept | - | −.32.51 (17.98) | −.12.19 (15.56) | 20.99 (6.42)** | −.4.12 (1.75)* | −.1.32 (1.39) | 2.20 (1.66) | −.31 (.55) | .60 (.72) |

| Alcohol Slope 17–21 | −.32.51 (17.98) | - | .88 (4.07) | −.4.93 (1.87)** | 1.39 (.52)** | .09 (.35) | −.60 (.45) | .19 (.15) | −.16 (.19) |

| Alcohol Slope 22–24 | −.12.19 (15.56) | .88 (4.07) | - | −.1.11 (2.41) | .17 (.61) | .22 (.20) | −.32 (3.72) | .03 (.94) | −.02 (.04) |

| Marijuana Intercept | 20.99 (6.42)** | −.4.93 (1.87)** | −.1.11 (2.41) | - | −.1.47 (.48)** | −.58 (.28)* | .49 (.26)* | −.10 (.09) | .01 (.07) |

| Marijuana Slope 17–21 | −.4.12 (1.75)* | 1.39 (.52)** | .17 (.61) | −.1.47 (.48)** | - | .07 (.08) | −.15 (.06)* | .05 (.02)* | .00 (.02) |

| Marijuana Slope 22–24 | −.1.32 (1.39) | .09 (.35) | .22 (.20) | −.58 (.28)* | .07 (.08) | - | −.05 (.17) | .00 (.04) | .02 (.01) |

| Poly Drug Intercept | 2.20 (1.66) | −.60 (.45) | −.32 (3.72) | .49 (.26)* | −.15 (.06)* | −.05 (.17) | - | −.06 (.03) | .00 (.05) |

| Poly Drug Slope 17–21 | −.31 (.55) | .19 (.15) | .03 (.94) | −.10 (.09) | .05 (.02)* | .00 (.04) | −.06 (.03) | - | .01 (.01) |

| Poly Drug Slope 22–24 | .60 (.72) | −.16 (.19) | −.02 (.04) | .01 (.07) | .00 (.02) | .02 (.01) | .00 (.05) | .01 (.01) | - |

|

|

|||||||||

| Currently Student | −.21.07 (6.28)** | 5.12 (1.76)** | .24 (1.64) | −.3.97 (1.07)*** | .65 (.30)* | .39 (.19)* | −.48 (.43) | .07 (.12) | .00 (.06) |

| Currently Employed | 9.36 (5.85) | −.1.21 (1.66) | 1.85 (.83)* | .02 (1.16) | −.20 (.33) | .47 (.24)* | −.21 (.26) | .07 (.08) | .06 (.05) |

| Live with Parent | 2.56 (4.59) | −.1.11 (1.26) | −.17 (.77) | −.77 (.88) | .22 (.25) | .06 (.17) | .26 (.32) | −.10 (.09) | .05 (.04) |

| Bisexual | .73 (2.65) | −.14 (.74) | −.50 (.50) | −.55 (.55) | .25 (.16) | −.07 (.12) | −.02 (.20) | .02 (.06) | .00 (.03) |

| Other Sexual Orientation | −.5.53 (4.89) | 2.49 (1.37) | −.42 (.71) | −.79 (1.10) | .23 (.31) | .11 (.20) | .06 (.35) | −.02 (.10) | .03 (.04) |

| Black | −.5.22 (5.30) | −.1.05 (1.47) | .89 (1.17) | .56 (.68) | −.47 (.19)* | −.03 (.15) | .01 (.24) | −.09 (.07) | .00 (.05) |

| Hispanic | −.3.78 (5.24) | .01 (1.45) | 1.27 (1.32) | .21 (.74) | −.35 (.21) | −.08 (.14) | .03 (.24) | −.06 (.07) | −.06 (.05) |

| Other Race | −.4.62 (5.52) | −.24 (1.59) | −.70 (.90) | .25 (.85) | −.32 (.23) | −.12 (.14) | .03 (.33) | −.05 (.09) | −.04 (.05) |

Notes:

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001.

AQF = Alcohol Quantity-Frequency, MF = Marijuana Frequency, PU = Poly-drug Use, AI = Alcohol Intercept, AS17 = Alcohol Slope from 17–21, AS22 = Alcohol Slope from 22–24, MI = Marijuana Intercept, MS17 = Marijuana Slope from 17–21, MS22 = Marijuana Slope 22–24, PI = Poly-drug Intercept, PS17 = Poly-drug Slope from 17–21, PS22 = Poly-drug Slope from 22–24

There were significant between-person differences based on student and employment status. Students reported significantly lower alcohol (Beta = −21.07, SE = 6.28) and marijuana frequency at age 17 (Beta = −3.97, SE = 1.07), but also had significantly higher growth in alcohol quantity-frequency (Beta = 5.12, SE = 1.76) and marijuana frequency from ages 17 to 21 (Beta = 0.65, SE = 0.30), and higher growth in marijuana frequency from ages 22–24 compared to non-students (Beta = 0.39, SE = 0.19). Participants who reported being employed had higher growth in alcohol (Beta = 1.85, SE = 0.83) and marijuana frequency (Beta = 0.47, SE = 0.24) from ages 22 to 24 compared to unemployed participants. There were no significant differences based on living with a parent.

4. Discussion

We found significant growth in quantity-frequency of alcohol use, frequency of marijuana use, and poly-drug use from late adolescence to age 21 for YMSM. Growth from the age of 22 to 24 was only significant for poly-drug use. Previous research has found evidence of increases in alcohol and drug use as YMSM move from adolescence to young adulthood (Dermody et al., 2014; Halkitis et al., 2014; Hatzenbuehler et al., 2008; Marshal et al., 2009; Newcomb et al., 2012), and these analyses expand on prior work and indicate that this growth may occur primarily during the teenage years. We also found that change for all three substance use behaviors was significantly positively correlated at both ages 17–21 and ages 22–24, with the exception of alcohol and poly-drug use which was only correlated at ages 17–21. To our knowledge, this is the first study to look at the associations between change in these different substance use factors for YMSM. The results suggest that during the transition from adolescence to adulthood, change in marijuana, alcohol, and illicit drug use co-vary across time.

These analyses revealed significant racial/ethnic group differences in substance use. Similar to previous research that has suggested that Black YMSM engage in less alcohol use compared to White YMSM (Newcomb et al., 2012; Newcomb et al., 2014b; Wong et al., 2008), Black participants had significantly lower increases in quantity-frequency of alcohol use from age 17 to 21. Hispanic/Latino participants were not significantly different from White participants on growth in alcohol quantity-frequency from 17–21, but they were significantly higher in growth from ages 22 to 24. Previous research with YMSM has been mixed with some finding that Hispanic/Latino YMSM were less likely to use alcohol compared to White YMSM (Newcomb et al., 2014b) and others finding no differences (Dermody et al., 2014). The current findings suggest that White and Hispanic/Latino YMSM do not start to diverge in alcohol use until later in young adulthood.

With regard to marijuana frequency, White participants had higher growth from ages 17 to 21 compared to Black participants and participants in the combined “other” racial group, but not compared to Hispanic/Latino participants. Black participants also had lower growth in marijuana frequency from ages 22 to 24 compared to White participants. Change in poly-drug use from 17 to 21 was lower for Black participants compared to non-Hispanic White participants. Growth in poly-drug use from ages 22 to 24 was lower for Hispanic/Latino participants compared to non-Hispanic Whites. Halkitis et al. (2014) were the only previous researchers to examine trajectories in YMSM for marijuana and illicit drug use. They found higher growth in marijuana use among Hispanic/Latino YMSM. They also found no racial/ethnic differences on growth in illicit drug use. Those patterns were not replicated in this study. The difference may be due in part to how substance use was measured by Halkitis and colleagues. They asked about the number of days substances were used in the prior month at each time point, instead of asking about use over the previous six months. They also asked about a wider variety of illicit substances. The different results may also be indicative of the difference in racial makeup of the two samples. While both were minority-majority in terms of race/ethnicity, our sample was much more heavily Black (51.5% vs. 14.9%) and less Hispanic/Latino (18.8% vs. 28.3%) compared to their sample. It may be that our samples differed in how representative they are of different racial/ethnic groups. The difference in patterns further demonstrates the necessity for more research analyzing long term patterns of change in marijuana and illicit substance use for YMSM.

Previous research has found bisexual YMSM to be more frequent substance users compared to their gay-identifying counterparts (Greenwood et al., 2001; Marshal et al., 2008; Newcomb et al., 2014a). In the current study, we did find higher growth in marijuana use for bisexual YMSM from ages 17 to 21 compared to gay participants. However, we did not find any differences in poly-drug use factors. If we had data on a wider variety of substances or a more high-risk sample, we may have been better able to detect significant differences on illicit substance use based on sexual orientation.

This is one of the few studies to look at concurrent change in alcohol, marijuana, and poly-drug use in YMSM. The mean age by the last wave was 23.59 and we still saw no evidence of substance use behaviors significantly decreasing. However, we did see evidence that growth was beginning to slow by the slopes at later ages measured in our study. Growth was lower from ages 22 to 24 and no longer significant for alcohol and marijuana use. These analyses suggest that alcohol, marijuana and illicit drug use increase more rapidly during the late teenage years than during young adulthood. Given that teens leave high school during the late teens and enter into more independent environments (e.g., college, work), this transition may provide more opportunities for substance use. It will be necessary to continue to follow MSM past age 24 to see if use begins to decrease over the course of their mid-to-late 20’s.

The pattern of covariation in the substance use measures has important implications for YMSM. Past research has already identified YMSM as separately vulnerable to higher rates of alcohol, marijuana, and illicit drug use (Corliss et al., 2008; Hughes and Eliason, 2002; Marshal et al., 2008; Newcomb et al., 2014a; Talley et al., 2014). That these behaviors covary suggests that the same YMSM with elevated levels of one substance use behavior may be at higher risk for elevated use of the other two, especially in the developmental period between 17–21, where we found all three to be significantly associated. This could be especially important for interventions targeting substance use in YMSM because it indicates that interventions should be tailored toward addressing co-occurrences of substance use behaviors. It also suggests that more research is necessary to determine why these behaviors co-occur in this population.

The impact of student status, employment status, and living with a parent were tested in a different framework compared to other predictors because they could vary over time. The multilevel model we ran found no within-person differences in substance use behaviors based on change in these three predictors over the course of the study. The lack of within-person differences might be partially due to a lack of change through the course of the study. Only 54.5% of participants reported a change in student status. For employment it was 64.9% and for living with a parent it was 47.5%. We may need to follow these YMSM for longer to fully understand the within-person effect of transitioning out or into these roles. We did find between-person differences for student and employment status. Identifying as a student appeared to be associated with lower alcohol and marijuana use at age 17 but higher growth over time in both behaviors compared to non-students. This is similar to past research with heterosexual samples that has found high school students who go on to attend college and college students at age 18 to have lower alcohol and marijuana use, but higher growth in both substances during their college years compared to youth who do not attend college (O’Malley and Johnston, 2002; White et al., 2005). It is therefore not surprising that we saw a more pronounced increase in substance use during the late teen years than during ages 22–24, given that most people transition out of college during the latter developmental period. Employment was associated with higher growth in alcohol and marijuana use later on from ages 22 to 24 compared to unemployment. We did not find evidence to support living at home or employment as protective factors as past research with YMSM has (Wong et al., 2013).

YMSM in our study with higher alcohol slopes between ages 17–21 were also at greater risk for alcohol-related problems as measured by the AUDIT. This finding indicated that an increase in alcohol quantity-frequency over the late adolescent period was associated with higher alcohol-related problems. This is in line with previous research that has found that earlier use of alcohol is associated with problems in adulthood (Chou and Pickering, 1992; DeWit et al., 2000; Ellickson et al., 2003; Grant and Dawson, 1997; Gruber et al., 1996; Hingson et al., 2006). The marijuana intercept and both slope measures had a similar association with the CUDIT where higher marijuana frequency at age 17 and higher growth over time were associated with more marijuana-related problems. Without the ability to control for AUDIT and CUDIT scores at earlier time points, it is impossible to say at what point higher rates of substance use led to more substance use related problems. These findings suggests that we are not merely observing developmentally normative increases in substance use over time in this sample, but we are also seeing that increases in use are associated with substance use problems.

This study was unique in that we combined data across two longitudinal cohorts of YMSM that we have followed for nine waves and an average of 4.71 years (SD = 1.68). Most previous research on alcohol trajectories followed YMSM for either shorter periods of time (Hatzenbuehler et al., 2008; Newcomb et al., 2012; Talley et al., 2010) or far fewer waves (Dermody et al., 2014; Marshal et al., 2009) and the one additional study to model trajectories of marijuana and illicit substance use only followed YMSM for 18 months (Halkitis et al., 2014). We have also controlled for differences in age and time of interviews by allowing participants to have individually varying assessment schedules within our models. Individually-varying time scores are an effective method for addressing these assessment differences when combining data across multiple studies, and a useful tool for researchers as they seek to create larger and more generalizable longitudinal samples. In addition to increasing the accuracy of our model, the use of time scores made it possible to combine data from the Crew 450 and Q2 samples.

The present study was limited in our measure of poly-drug use. We only had measures of methamphatimes, cocaine, and ecstasy at every time point for the sample. Methamphatimes in particular were lowly endorsed. More comprehensive data on illicit substance use may have identified different longitudinal patterns in the data. For our sample, higher levels of baseline marijuana and poly-drug use were associated with participation in fewer waves of data. MPlus uses maximum likelihood to address missingness which assumes that data will be missing at random. For our sample, that may mean that growth in marijuana and poly-drug use is not as accurate for those with the highest levels of early use. An additional limitation was the high amount of missingness on the AUDIT and CUDIT outcomes where only 35% of respondents provided data. This is largely due to the peculiarities of the RADAR sample where only a randomized half of Crew 450 participants were selected to enroll. For this reason, participants from Project Q2 were more likely to have AUDIT and CUDIT data. Missingness on these outcomes was not associated with sexual orientation, race/ethnicity, baseline age, baseline substance use, education level, student status, employment status, or living with a parent at baseline. To better understand the impact of the large amount of missingness, we reran the outcome model with only the participants who provided outcome data. The significance of substance use factors on the AUDIT and CUDIT replicated with the exception of change in marijuana use from ages 17–21 which was no longer significantly associated with CUDIT scores.

Additional limitations included how we recoded Project Q2 data on alcohol and marijuana use to reconcile with Crew 450 measurements. Both samples had a similar distribution after the recode, but we did assume for the Project Q2 participants that when they reported the number of days of use in the previous six months that the days they reported were evenly distributed over time to match with the Crew 450 categories. That assumption does create an additional source of measurement error if substance use was more concentrated (i.e., if a participant reported 14 days of use in the last six months that actually refers to daily use for two weeks and five and half months of abstinence instead of 2–3 times a month as we assumed in the recode). There is also a limitation to using the individually-varying time scores in this sample. We have fewer participants providing data at age 17 and age 24 compared to the ages in between. It may mean that estimates of substance use at those ages are less reliable compared to the ages where we have more coverage.

Future research should continue to follow YMSM and their engagement with substance use throughout the young adult years and into adulthood. Normative trajectories from adolescence to early adulthood suggest that substance use increases during this period and then begins to decrease when people enter their late 20’s and into their 30’s (Bachman et al., 1997; Chen and Kandel, 1995). With more data we will be able to observe whether YMSM follow this same pattern. The more we understand the long term trajectories, the more we will be able to design prevention efforts around them. It is also important that we better understand the antecedents to higher levels of substance use in this population. There are also many additional factors that can contribute to changes in substance use for YMSM, including experiences of victimization (Huebner et al., 2015; Wong et al., 2010), socioeconomic status (Halkitis et al., 2014), social support (Wright and Perry, 2006), and personality factors (Andrucci et al., 1989; Kalichman et al., 1996; Kalichman et al., 1998; Kashubeck-West and Szymanski, 2008). Finally, we should look at how these substance use trajectories relate to changes in sexual risk-taking over time which may be particularly vital to understand in YMSM populations.

The present study found that development in alcohol, marijuana, and poly-drug use over the course of adolescence into young adulthood was related in YMSM, and that higher growth in alcohol quantity-frequency and marijuana frequency was associated with higher alcohol-related and marijuana-related problems, respectively. The increase in substance use behaviors into young adulthood for YMSM is not by itself atypical compared to heterosexual men, but the fact that those increasing the most over time were at highest risk for problematic alcohol and marijuana use in this sample illustrates the importance of tracking these behaviors and suggests that the dearth of previous research in this area needs to be remedied.

Highlights.

Combined two samples (N=552) of diverse young men who have sex with men (YMSM).

Modeled substance use trajectories from late-adolescence to young adulthood.

Alcohol, marijuana, and poly-drug use significantly increased over time.

Marijuana, alcohol, and poly-drug use trajectories were significantly correlated.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the grant funding that supported the studies described in this manuscript: Crew 450 (National Institute on Drug Abuse, R01DA025548), Q2 (National Institute of Mental Health, R21MH095413), and RADAR (National Institute on Drug Abuse, U01DA036939). We acknowledge the NIH supported Third Coast Center for AIDS Research for creating a supportive environment for HIV/AIDS research (P30AI117943). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funders.

Role of Funding Source

This research was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01DA025548 & U01DA036939) and the National Institute of Mental Health (R21MH095413).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Author Disclosures

Contributors

Gregory Swann led the development of the current manuscript, including contributing a majority of the analytic work and writing included in the final manuscript. Emily Bettin contributed to the development of the Introduction and Discussion, as well as assisting in the writing for both sections. Antonia Clifford was instrumental in the data collection for the Q2 and RADAR samples and drafted the Methods section of the current manuscript. Michael E. Newcomb is a co-PI for the RADAR project. He supervised the development of the current manuscript and contributed to writing. Brian Mustanski is the PI for RADAR, Crew 450, and Project Q2. He also contributed to the writing of the manuscript. All authors have approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict declared.

References

- Adamson SJ, Kay-Lambkin FJ, Baker AL, Lewin TJ, Thornton L, Kelly BJ, Sellman JD. An improved brief measure of cannabis misuse: The Cannabis Use Disorders Identification Test-Revised (CUDIT-R) Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;110:137–143. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrucci GL, Archer RP, Pancoast DL, Gordon RA. The relationship of MMPI and Sensation Seeking Scales to adolescent drug use. J. Pers. Assess. 1989;53:253–266. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa5302_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ. The developmental context of substance use in emerging adulthood. J. Drug Issues. 2005;35:235–254. [Google Scholar]

- Bachman JG, Wadsworth KN, O’Malley PM, Johnston LD. Smoking, drinking, and drug use in young adulthood: The impacts of new freedoms and new responsibilities. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc; Hillsdale, N.J., England: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Beck EC, Birkett M, Armbruster B, Mustanski B. A data-driven simulation of HIV spread among young men who have sex with men: Role of age and race mixing and STIs. J. Acq. Imm. Defic. Syndr. 2015;70:186–194. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen K, Kandel DB. The natural history of drug use from adolescence to the mid-thirties in a general population sample. Am. J. Public Health. 1995;85:41–47. doi: 10.2105/ajph.85.1.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou SP, Pickering RP. Early onset of drinking as a risk factor for lifetime alcohol-related problems. Br. J. Addict. 1992;87:1199–1204. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1992.tb02008.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clatts MC, Goldsamt LA, Yi H. Club drug use among young men who have sex with men in NYC: A preliminary epidemiological profile. Subst. Use Misuse. 2005;40:1317–1330. doi: 10.1081/JA-200066898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochran SD, Ackerman D, Mays VM, Ross MW. Prevalence of non-medical drug use and dependence among homosexually active men and women in the US population. Addiction. 2004;99:989–998. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00759.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corliss HL, Rosario M, Wypij D, Fisher LB, Austin SB. Sexual orientation disparities in longitudinal alcohol use patterns among adolescents findings from the growing up today study. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2008;162:1071–1078. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.162.11.1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dermody SS, Marshal MP, Cheong J, Burton C, Hughes T, Aranda F, Friedman MS. Longitudinal disparities of hazardous drinking between sexual minority and heterosexual individuals from adolescence to young adulthood. J. Youth Adolesc. 2014;43:30–39. doi: 10.1007/s10964-013-9905-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeWit DJ, Adlaf EM, Offord DR, Ogborne AC. Age at first alcohol use: A risk factor for the development of alcohol disorders. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2000;157:745–750. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.5.745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drabble L, Midanik LT, Trocki K. Reports of alcohol consumption and alcohol-related problems among homosexual, bisexual and heterosexual respondents: Results from the 2000 National Alcohol Survey. J. Stud. Alcohol. 2005;66:111–120. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellickson PL, Tucker JS, Klein DJ. Ten-year prospective study of public health problems associated with early drinking. Pediatrics. 2003;111:949–955. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.5.949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garofalo R, Hotton AL, Kuhns LM, Gratzer B, Mustanski B. Incidence of HIV infection and sexually transmitted infections and related risk factors among very young men who have sex with men. J. Acq. Imm. Defic. Syndr. 2016;72:79–86. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Dawson DA. Age at onset of alcohol use and its association with DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence: Results from the National Longitudinal Alcohol Epidemiological Survey. J. Subst. Abuse. 1997;9:103–110. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(97)90009-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood GL, White EW, Page-Shafer K, Bein E, Osmond DH, Paul J, Stall RD. Correlates of heavy substance use among young gay and bisexual men: The San Francisco Young Men’s Health Study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2001;61:105–112. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(00)00129-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruber E, DiClemente RJ, Anderson MM, Lodico M. Early drinking onset and its association with alcohol use and problem behavior in late adolescence. Prev. Med. 1996;25:293–300. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1996.0059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halkitis PN, Siconolfi DE, Stults CB, Barton S, Bub K, Kapadia F. Modeling substance use in emerging adult gay, bisexual, and other YMSM across time: The P18 cohort study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;145:209–216. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, Corbin WR, Fromme K. Trajectories and determinants of alcohol use among LGB young adults and their heterosexual peers: Results from a prospective study. Dev. Psychol. 2008;44:81–90. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.44.1.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hingson RW, Heeren T, Winter MR. Age at drinking onset and alcohol dependence: Age at onset, duration, and severity. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2006;160:739–746. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.7.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huebner DM, Thoma BC, Neilands TB. School victimization and substance use among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender adolescents. Prev. Sci. 2015;16:734–743. doi: 10.1007/s11121-014-0507-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes TL, Eliason M. Substance use and abuse in lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender populations. J. Prim. Prev. 2002;22:263–298. [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC, Heckman T, Kelly JA. Sensation seeking as an explanation for the association between substance use and HIV-related risky sexual behavior. Arch. Sex. Behav. 1996;25:141–154. doi: 10.1007/BF02437933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC, Tannenbaum L, Nachimson D. Personality and cognitive factors influencing substance use and sexual risk for HIV infection among gay and bisexual men. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 1998;12:262–271. [Google Scholar]

- Kandel DB, Logan JA. Patterns of drug use from adolescence to young adulthood: I. Periods of risk for initiation, continued use, and discontinuation. Am. J. Public Health. 1984;74:660–666. doi: 10.2105/ajph.74.7.660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashubeck-West S, Szymanski DM. Risky sexual behavior in gay and bisexual men -Internalized heterosexism, sensation seeking, and substance use. Counsel. Psychol. 2008;36:595–614. [Google Scholar]

- Kipke MD, Weiss G, Ramirez M, Dorey F, Ritt-Olson A, Iverson E, Ford W. Club drug use in los angeles among young men who have sex with men. Subst. Use Misuse. 2007;42:1723–1743. doi: 10.1080/10826080701212261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowlton R, McCusker J, Stoddard A, Zapka J, Mayer K. The use of the CAGE questionnaire in a cohort of homosexually active men. J. Stud. Alcohol. 1994;55:692–694. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1994.55.692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackesy-Amiti ME, Fendrich M, Johnson TP. Substance-related problems and treatment among men who have sex with men in comparison to other men in Chicago. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2009;36:227–233. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2008.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshal MP, Friedman MS, Stall R, King KM, Miles J, Gold MA, Bukstein OG, Morse JQ. Sexual orientation and adolescent substance use: A meta-analysis and methodological review. Addiction. 2008;103:546–556. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02149.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshal MP, Friedman MS, Stall R, Thompson AL. Individual trajectories of substance use in lesbian, gay and bisexual youth and heterosexual youth. Addiction. 2009;104:974–981. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02531.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta PD, West SG. Putting the individual back into individual growth curves. Psychol. Methods. 2000:5. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.5.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustanski B. Ethical and regulatory issues with conducting sexuality research with LGBT adolescents: A call to action for a scientifically informed approach. Arch. Sexual Behav. 2011;40:673–686. doi: 10.1007/s10508-011-9745-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustanski BS, Garofalo R, Emerson EM. Mental health disorders, psychological distress, and suicidality in a diverse sample of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youths. Am. J. Public Health. 2010;100:2426–2432. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.178319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb ME, Birkett M, Corliss HL, Mustanski B. Sexual orientation, gender, and racial differences in illicit drug use in a sample of US high school students. Am. J. Public Health. 2014a;104:304–310. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb ME, Heinz AJ, Mustanski B. Examining risk and protective factors for alcohol use in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth: a longitudinal multilevel analysis. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs. 2012;73:783–793. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2012.73.783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb ME, Mustanski B. Developmental change in the effects of sexual partner and relationship characteristics on sexual risk behavior in young men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2015;20:1284–1294. doi: 10.1007/s10461-015-1046-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb ME, Ryan DT, Garofalo R, Mustanski B. Race-based sexual stereotypes and their effects on sexual risk behavior in racially diverse young men who have sex with men. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2015;44:1959–1968. doi: 10.1007/s10508-015-0495-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb ME, Ryan DT, Greene GJ, Garofalo R, Mustanski B. Prevalence and patterns of smoking, alcohol use, and illicit drug use in young men who have sex with men. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014b;141:65–71. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Malley PM, Johnston LD. Epidemiology of alcohol and other drug use among American college students. J. Stud. Alcohol Suppl. 2002:14. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, de la Fuente JR, Grant M. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO Collaborative Project on Early Detection of Persons with Harmful Alcohol Consumption--II. Addiction. 1993;88:791–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulenberg J, Magg JL, Steinman KJ, Zucker RA. Development matters: Taking the long view on substance use etiology and intervention during adolescence. In: Monti PM, Colby SM, O’Leary TA, editors. Adolescents, Alcohol, and Substance Abuse: Reaching Teens Through Brief Interventions. Guilford Press; New York: 2001. pp. 19–57. [Google Scholar]

- Schulenberg JE, Maggs JL. A developmental perspective on alcohol use and heavy drinking during adolescence and the transition to young adulthood. J. Stud. Alcohol Suppl. 2002;14:54–70. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stall R, Paul JP, Greenwood G, Pollack LM, Bein E, Crosby GM, Mills TC, Binson D, Coates TJ, Catania J. Alcohol use, drug use and alcohol-related problems among men who have sex with men: The Urban Men’s Health Study. Addiction. 2001;96:1589–1601. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.961115896.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterba SK. Fitting nonlinear latent growth curve models with individually varying time points. Struct. Equat. Model. 2014:21. [Google Scholar]

- Talley AE, Hughes TL, Aranda F, Birkett M, Marshal MP. Exploring alcohol-use behaviors among heterosexual and sexual minority adolescents: Intersections with sex, age, and race/ethnicity. Am. J. Public Health. 2014;104:295–303. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talley AE, Sher KJ, Littlefield AK. Sexual orientation and substance use trajectories in emerging adulthood. Addiction. 2010;105:1235–1245. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.02953.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren JC, Fernandez MI, Harper GW, Hidalgo MA, Jamil OB, Torres RS. Predictors of unprotected sex among young sexually active African American, Hispanic, and White MSM: The importance of ethnicity and culture. AIDS Behav. 2008;12:459–468. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9291-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Fleming CB, Kim MJ, Catalano RF, McMorris BJ. Identifying two potential mechanisms for changes in alcohol use among college-attending and non-college-attending emerging adults. Dev. Psychol. 2008;44:1625–1639. doi: 10.1037/a0013855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Labouvie EW, Papadaratsakis V. Changes in substance use during the transition to adulthood: A comparison of college students and their noncollege age peers. J. Drug Issues. 2005:35. [Google Scholar]

- Wong CF, Kipke MD, Weiss G. Risk factors for alcohol use, frequent use, and binge drinking among young men who have sex with men. Addict. Behav. 2008;33:1012–1020. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong CF, Schrager SM, Chou CP, Weiss G, Kipke MD. Changes in developmental contexts as predictors of transitions in HIV-risk behaviors among young men who have sex with men (YMSM) Am. J. Community Psychol. 2013;51:439–450. doi: 10.1007/s10464-012-9562-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong CF, Weiss G, Ayala G, Kipke MD. Harassment, discrimination, violence, and illicit drug use among young men who have sex with men. AIDS Educ. Prev. 2010;22:286–298. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2010.22.4.286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright ER, Perry BL. Sexual identity distress, social support, and the health of gay, lesbian, and bisexual youth. J. Homosexual. 2006;51:81–110. doi: 10.1300/J082v51n01_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]