Abstract

Can the quality of care be improved by repeated measurement? We show that measuring protocol adherence repeatedly over ten weeks leads to significant improvements in quality immediately and up to 18 months later without any additional training, equipment, supplies or material incentives. 96 clinicians took part in a study which included information, encouragement, scrutiny and repeated contact with the research team measuring quality. We examine protocol adherence over the course of the study and for 45 of the original clinicians 18 months after the conclusion of the project. Health workers change their behavior significantly over the course of the study, and even eighteen months later demonstrate a five percentage point improvement in quality. The dynamics of clinicians’ reactions to this intervention suggest that quality can be improved by the repeated measurement by external peers in a way that provides reminders of expectations.

Keywords: Quality of Care, Low Income Countries, Results Based Financing, The Hawthorne Effect, Altruism, Pro-social Motivation, Supportive Supervision

1 Introduction

In developing and transition countries, quality of health care services are generally low in large part because adherence to medical protocols is low (Das & Gertler, 2007; Das & Hammer, 2007; Holloway, Ivanovska, Wagner, Vialle-Valentin, & Ross-Degnan, 2013; Leonard & Masatu, 2007; Rowe, de Savigny, Lanata, & Victora, 2005) and increases in adherence are one of the most effective ways to improve outcomes and prevent childhood deaths (Black, Morris, & Bryce, 2003; Jones et al., 2003; Rowe et al., 2005). Many types of interventions to improve quality have been tested in developing countries with somewhat positive results, including improved supervision, additional training, and interventions to change the workplace culture (such as institutional and management changes and group-based techniques). Yet few of these techniques have lasting impacts or have been rolled out effectively at scale and low adherence remains. Importantly there is increasing evidence of an important know-do gap (Das & Hammer, 2007; Leonard & Masatu, 2010; Rethans, Sturmans, Drop, van der Vleuten, & Hobus, 1991) in which clinicians demonstrate that they know how to adhere to protocol but choose not to do so. Indeed it is possible that the short-term benefits to a wide variety of interventions and the demonstrated know-do gap are connected and demonstrate a basic Hawthorne effect: when faced with the immediate attention and scrutiny inherent in any intervention, clinicians improve adherence but adherence falls as the attention diminishes.

This paper examines a specific program designed to extend a short-term Hawthorne effect to the medium-term by maintaining scrutiny and attention without any training, explicit supervision, institutional reforms or external rewards. The study encouraged clinicians to adhere to protocol and then returned about two weeks later to see if quality had improved. To test for the medium-term impact we designed the intervention with a follow-up at about 6 weeks after the original encouragement. As we show in this paper, we observed the opposite of what we expected: quality was only marginally higher in the short-term (the two week window) but significantly higher for the medium-term (the 8 week window). As a result of this surprising finding, we returned almost a year and half later to visit the same clinicians and found that quality was still higher than in the baseline though slightly less than at the medium-term.

This paper uses this data on the response to the program in the short, medium and long-term and shows evidence that the know-do gap is closed with increased and sustained attention and scrutiny, and that some forms of measurement, by themselves, can lead to long-term improvements in quality.

2 Methods

The data in this paper comes from 4,512 patient exit interviews conducted in two different periods and over three samples of clinicians. For a four-hour window on a randomly-selected unannounced date, members of the enumeration team asked all the patients who had visited a particular clinician a series of questions about their consultation based on the symptoms that they reported. The interviews with patients followed the Retrospective Consultation Review (RCR) instrument which allows us to reconstruct the clinicians’ activities, specifically the extent to which they followed protocol (Brock, Lange, & Leonard, 2016). All the questions used in the instrument are reported in Table 6, Table 7, and Table 8 in the appendix. For example, according to protocol, a doctor is supposed to check for neck stiffness for all patients reporting with a fever, and we ask patients with a fever “did the doctor ask you if your neck was stiff?” Although patient recall is not perfect, it is highly correlated with what actually takes place (Leonard & Masatu, 2006).

Table 6.

Average Protocol Adherence for Individual Items (Part I)

| Summary scores | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||

| Overall Adherence | 0.736 (0.012) | 0.749 (0.014) | 0.718 (0.016) | 0.729 (0.009) | 0.810 (0.009) + | 0.773 (0.014) + | 0.730 (0.011) | |

| Primed items adherence | 0.719 (0.014) | 0.746 (0.017) | 0.717 (0.019) | 0.737 (0.011) | 0.836 (0.010) + | 0.725 (0.015) | 0.706 (0.012) | |

| Non-primed items adherence | 0.764 (0.009) | 0.766 (0.012) | 0.771 (0.013) | 0.767 (0.007) | 0.813 (0.007) + | 0.823 (0.010) + | 0.799 (0.007) + | |

| Overall effect size | 0.679 (0.013) | 0.691 (0.017) | 0.657 (0.019) | 0.674 (0.010) | 0.768 (0.010) + | 0.707 (0.015) | 0.662 (0.012) | |

| Item type | Did the doctor … | |||||||

| General History Taking | ask you how long you had been suffering? | 0.901 (0.013) | 0.918 (0.016) | 0.918 (0.017) | 0.923 (0.009) | 0.956 (0.008) + | 0.931 (0.015) | 0.918 (0.011) |

| ask you if there were other symptoms different from the main complaint? | 0.817 (0.017) | 0.815 (0.023) | 0.754 (0.027)− | 0.789 (0.014) | 0.889 (0.012) + | 0.826 (0.022) | 0.752 (0.018) − | |

| * ask if you already received treatment elsewhere or took medicine? | 0.705 (0.020) | 0.754 (0.026) | 0.691 (0.029) | 0.737 (0.015) | 0.864 (0.014) + | 0.725 (0.026) | 0.662 (0.020) | |

| Fever, history taking | ask you how long you had had a fever? | 0.756 (0.037) | 0.744 (0.048) | 0.767 (0.050) | 0.755 (0.030) | 0.816 (0.032) | 0.789 (0.049) | 0.748 (0.038) |

| ask you if you had chills or sweats? | 0.600 (0.042) | 0.439 (0.055) − | 0.507 (0.059) | 0.599 (0.034) | 0.730 (0.036) + | 0.606 (0.058) | 0.565 (0.043) | |

| ask you if you had a cough or difficulty breathing? | 0.667 (0.041) | 0.585 (0.055) | 0.575 (0.058) | 0.528 (0.034) − | 0.645 (0.039) | 0.606 (0.058) | 0.519 (0.044) − | |

| ask you if you had diarrhea or vomiting? | 0.694 (0.040) | 0.634 (0.054) | 0.548 (0.059) − | 0.575 (0.034) − | 0.724 (0.036) | 0.704 (0.055) | 0.626 (0.042) | |

| ask if you had a runny nose? | 0.701 (0.040) | 0.683 (0.052) | 0.603 (0.058) | 0.646 (0.033) | 0.730 (0.036) | 0.732 (0.053) | 0.695 (0.040) | |

| Fever, history taking, under 5 | ask the child had convulsions? | 0.119 (0.042) | 0.349 (0.074) + | 0.194 (0.072) | 0.195 (0.044) | 0.192 (0.055) | 0.303 (0.081) + | 0.389 (0.067) + |

| ask about difficulty drinking or breastfeeding? | 0.339 (0.062) | 0.558 (0.077) + | 0.355 (0.087) | 0.390 (0.054) | 0.481 (0.070) | 0.424 (0.087) | 0.556 (0.068) + | |

| Listen to the child’s breathing, or use a stethoscope? | 0.644 (0.063) | 0.558 (0.077) | 0.613 (0.089) | 0.602 (0.054) | 0.712 (0.063) | 0.758 (0.076) | 0.755 (0.060) | |

| check the child’s ear? | 0.373 (0.063) | 0.442 (0.077) | 0.355 (0.087) | 0.349 (0.053) | 0.481 (0.070) | 0.667 (0.083) + | 0.491 (0.069) | |

| ask questions about the child’s vaccinations? | 0.288 (0.059) | 0.442 (0.077) | 0.387 (0.089) | 0.361 (0.053) | 0.308 (0.065) | 0.424 (0.087) | 0.509 (0.069) + | |

| ask the duration of the cough? | 0.849 (0.035) | 0.875 (0.045) | 0.870 (0.050) | 0.853 (0.028) | 0.884 (0.033) | 0.814 (0.051) | 0.793 (0.042) | |

| Cough, history taking | ask if there was sputum? | 0.642 (0.047) | 0.571 (0.067) | 0.565 (0.074) | 0.635 (0.039) | 0.716 (0.047) | 0.610 (0.064) | 0.663 (0.050) |

| ask if you had blood in your cough? | 0.396 (0.048) | 0.429 (0.067) | 0.435 (0.074) | 0.381 (0.039) | 0.568 (0.051) + | 0.373 (0.063) | 0.391 (0.051) | |

| ask if you had difficulty breathing? | 0.698 (0.045) | 0.661 (0.064) | 0.717 (0.067) | 0.755 (0.035) | 0.821 (0.040) + | 0.576 (0.065) | 0.674 (0.049) | |

| ask if you also have a fever? | 0.830 (0.037) | 0.750 (0.058) | 0.870 (0.050) | 0.774 (0.034) | 0.758 (0.044) | 0.627 (0.063) − | 0.674 (0.049) − | |

Columns represent proportion of the time that an item is properly used for 1) baseline, 2) scrutiny, 3) post-scrutiny, 4) short-term post encouragement, 5) medium-term post encouragement, 6) longer term post encouragement, and 7) comparison sample baseline.

+ and − indicate values that are significantly greater and lesser than the baseline.

indicates primed items

Table 7.

Average Protocol Adherence for Individual Items (Part II)

| Item type | Did the doctor … | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cough, history taking, under 5 | ask about difficulty drinking or breastfeeding? | 0.196 (0.059) | 0.387 (0.089) + | 0.316 (0.110) | 0.328 (0.062) | 0.250 (0.073) | 0.217 (0.088) | 0.231 (0.068) |

| ask if the child had convulsions? | 0.283 (0.067) | 0.484 (0.091) + | 0.474 (0.118) | 0.431 (0.066) | 0.389 (0.082) | 0.217 (0.088) | 0.487 (0.081) + | |

| check the child’s ear? | 0.196 (0.059) | 0.258 (0.080) | 0.263 (0.104) | 0.153 (0.047) | 0.056 (0.039) − | 0.130 (0.072) | 0.231 (0.068) | |

| ask if the child had diarrhea or vomiting? | 0.304 (0.069) | 0.387 (0.089) | 0.474 (0.118) | 0.373 (0.063) | 0.333 (0.080) | 0.478 (0.106) | 0.436 (0.080) | |

| ask about the history of vaccinations? | 0.500 (0.075) | 0.484 (0.091) | 0.474 (0.118) | 0.610 (0.064) | 0.500 (0.085) | 0.391 (0.104) | 0.564 (0.080) | |

| Diarrhea, history taking | ask how long you have had diarrhea? | 0.829 (0.065) | 0.750 (0.112) | 0.800 (0.133) | 0.902 (0.047) | 0.960 (0.040) | 0.952 (0.048) | 0.763 (0.070) |

| ask how often you have a movement? | 0.657 (0.081) | 0.533 (0.133) | 0.500 (0.167) | 0.707 (0.072) | 0.920 (0.055) + | 0.952 (0.048) + | 0.711 (0.075) | |

| ask about the way the stool looks? | 0.743 (0.075) | 0.667 (0.126) | 0.500 (0.167) | 0.707 (0.072) | 0.840 (0.075) | 0.762 (0.095) | 0.658 (0.078) | |

| as if there was blood in the stool? | 0.571 (0.085) | 0.467 (0.133) | 0.400 (0.163) | 0.550 (0.080) | 0.720 (0.092) | 0.714 (0.101) | 0.579 (0.081) | |

| ask if you are vomiting? | 0.743 (0.075) | 0.733 (0.118) | 0.900 (0.100) | 0.700 (0.073) | 0.760 (0.087) | 0.857 (0.078) | 0.684 (0.076) | |

| as if you also have a fever? | 0.800 (0.069) | 0.600 (0.131) | 0.900 (0.100) | 0.750 (0.069) | 0.840 (0.075) | 0.667 (0.105) | 0.421 (0.081) − | |

| Diarrhea, history taking, under 5 | ask about difficulty drinking or breastfeeding? | 0.545 (0.157) | 0.545 (0.157) | 0.400 (0.245) | 0.400 (0.112) | 0.600 (0.163) | 0.385 (0.140) | 0.455 (0.109) |

| ask if the child had convulsions? | 0.273 (0.141) | 0.273 (0.141) | 0.400 (0.245) | 0.200 (0.092) | 0.100 (0.100) | 0.154 (0.104) | 0.364 (0.105) | |

| check the child’s ear? | 0.182 (0.122) | 0.364 (0.152) | 0.600 (0.245) | 0.300 (0.105) | 0.500 (0.167) | 0.692 (0.133) + | 0.364 (0.105) | |

| ask if the child had diarrhea or vomiting? | 0.727 (0.141) | 0.727 (0.141) | 0.800 (0.200) | 0.800 (0.092) | 1.000 (0.000) + | 0.769 (0.122) | 0.864 (0.075) | |

| ask questions about the child’s vaccinations? | 0.273 (0.141) | 0.545 (0.157) | 0.400 (0.245) | 0.250 (0.099) | 0.400 (0.163) | 0.385 (0.140) | 0.273 (0.097) | |

| Fever, diagnostic | * take your temperature? | 0.746 (0.037) | 0.614 (0.054) − | 0.553 (0.057) − | 0.688 (0.031) | 0.763 (0.035) | 0.718 (0.054) | 0.756 (0.038) |

| check for neck stiffness? | 0.338 (0.041) | 0.366 (0.054) | 0.247 (0.051) | 0.272 (0.031) | 0.322 (0.038) | 0.408 (0.059) | 0.356 (0.042) | |

| ask if you felt weakness from lack of blood? | 0.346 (0.041) | 0.463 (0.055) + | 0.233 (0.050) − | 0.305 (0.032) | 0.434 (0.040) | 0.634 (0.058) + | 0.504 (0.044) + | |

| look in your ears or throat? | 0.309 (0.040) | 0.366 (0.054) | 0.192 (0.046) − | 0.268 (0.030) | 0.368 (0.039) | 0.423 (0.059) | 0.244 (0.038) | |

| check your stomach? | 0.331 (0.040) | 0.378 (0.054) | 0.192 (0.046) − | 0.221 (0.028) − | 0.303 (0.037) | 0.338 (0.057) | 0.282 (0.039) | |

| ask for a blood slide? | 0.750 (0.037) | 0.646 (0.053) | 0.726 (0.053) | 0.775 (0.029) | 0.757 (0.035) | 0.732 (0.053) | 0.664 (0.041) |

Columns represent proportion of the time that an item is properly used for 1) baseline, 2) scrutiny, 3) post-scrutiny, 4) short-term post encouragement, 5) medium-term post encouragement, 6) longer term post encouragement, and 7) comparison sample baseline.

+ and − indicate values that are significantly greater and lesser than the baseline.

indicates primed items

Table 8.

Average Protocol Adherence for Individual Items (Part III)

| Item type | Did the doctor … | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fever, diagnostic, under 5 | check if the child was sleepy, try to wake up the child? | 0.300 (0.060) | 0.357 (0.075) | 0.129 (0.061) − | 0.256 (0.048) | 0.283 (0.062) | 0.394 (0.086) | 0.528 (0.069) + |

| pinch the skin fold of the child? | 0.305 (0.060) | 0.405 (0.077) | 0.194 (0.072) | 0.207 (0.045) | 0.377 (0.067) | 0.394 (0.086) | 0.472 (0.069) + | |

| check both of the child’s feet? | 0.136 (0.045) | 0.190 (0.061) | 0.323 (0.085) + | 0.122 (0.036) | 0.283 (0.062) + | 0.303 (0.081) + | 0.377 (0.067) + | |

| check the child’s weight against a chart? | 0.356 (0.063) | 0.524 (0.078) + | 0.419 (0.090) | 0.354 (0.053) | 0.377 (0.067) | 0.424 (0.087) | 0.283 (0.062) | |

| Cough, diagnostic | * look at your throat? | 0.448 (0.049) | 0.509 (0.068) | 0.404 (0.072) | 0.442 (0.040) | 0.442 (0.051) | 0.197 (0.051) − | 0.275 (0.047) − |

| listen to your chest? | 0.676 (0.046) | 0.691 (0.063) | 0.596 (0.072) | 0.686 (0.037) | 0.779 (0.043) | 0.633 (0.063) | 0.670 (0.050) | |

| * take your temperature? | 0.629 (0.047) | 0.564 (0.067) | 0.574 (0.073) | 0.561 (0.040) | 0.663 (0.049) | 0.450 (0.065) − | 0.527 (0.053) | |

| Cough, diagnostic, under 5 | check if the child was sleepy, try to wake up the child? | 0.302 (0.071) | 0.516 (0.091) + | 0.250 (0.099) | 0.390 (0.064) | 0.263 (0.072) | 0.522 (0.106) + | 0.282 (0.073) |

| pinch the skin fold of the child? | 0.295 (0.070) | 0.452 (0.091) | 0.263 (0.104) | 0.310 (0.061) | 0.333 (0.080) | 0.348 (0.102) | 0.205 (0.066) | |

| check the child’s eyes, tongue, and palms? | 0.318 (0.071) | 0.419 (0.090) | 0.316 (0.110) | 0.500 (0.066) + | 0.333 (0.080) | 0.348 (0.102) | 0.333 (0.076) | |

| check both of the child’s feet? | 0.136 (0.052) | 0.290 (0.083) | 0.105 (0.072) | 0.155 (0.048) | 0.167 (0.063) | 0.130 (0.072) | 0.154 (0.059) | |

| check the child’s weight against a chart? | 0.205 (0.062) | 0.355 (0.087) | 0.421 (0.116) + | 0.431 (0.066) + | 0.222 (0.070) | 0.217 (0.088) | 0.231 (0.068) | |

| Diarrhea, diagnostic | pinch the skin on the stomach? | 0.286 (0.077) | 0.500 (0.129) | 0.300 (0.153) | 0.268 (0.070) | 0.320 (0.095) | 0.238 (0.095) | 0.237 (0.070) |

| * take your temperature? | 0.457 (0.085) | 0.375 (0.125) | 0.400 (0.163) | 0.439 (0.078) | 0.680 (0.095) + | 0.524 (0.112) | 0.421 (0.081) | |

| If the child is under two years, look at the child’s head? | 0.029 (0.029) | 0.067 (0.067) | 0.100 (0.100) | 0.049 (0.034) | 0.040 (0.040) | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.081 (0.045) | |

| offer the child a drink of water or observe breastfeeding? | 0.182 (0.122) | 0.100 (0.100) | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.100 (0.069) | 0.300 (0.153) | 0.077 (0.077) | 0.130 (0.072) | |

| Diarrhea, diagnostic, under 5 | check the child’s eyes, tongue, and palms? | 0.182 (0.122) | 0.400 (0.163) | 0.200 (0.200) | 0.400 (0.112) | 0.300 (0.153) | 0.538 (0.144) + | 0.391 (0.104) |

| check both of the child’s feet? | 0.091 (0.091) | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.200 (0.092) | 0.500 (0.167) + | 0.154 (0.104) | 0.348 (0.102) | |

| check the child’s weight against a chart? | 0.545 (0.157) | 0.200 (0.133) | 0.800 (0.200) | 0.450 (0.114) | 0.400 (0.163) | 0.154 (0.104) − | 0.348 (0.102) | |

| General, diagnostic Education | examine you? | 0.755 (0.021) | 0.771 (0.028) | 0.710 (0.031) | 0.693 (0.018) − | 0.700 (0.020) − | 0.860 (0.032) + | 0.835 (0.024) + |

| * tell you the name of your illness? | 0.745 (0.019) | 0.786 (0.024) | 0.781 (0.026) | 0.771 (0.014) + | 0.846 (0.014) + | 0.793 (0.023) | 0.797 (0.017) − | |

| * explain your illness in plain language? | 0.778 (0.018) | 0.786 (0.024) | 0.781 (0.026) | 0.774 (0.014) + | 0.869 (0.013) + | 0.767 (0.024) | 0.773 (0.017) − | |

| * explain if you need to return? | 0.712 (0.019) | 0.776 (0.025) + | 0.746 (0.027) | 0.763 (0.015) + | 0.836 (0.015) + | 0.715 (0.026) | 0.643 (0.020) − |

Columns represent proportion of the time that an item is properly used for 1) baseline, 2) scrutiny, 3) post-scrutiny, 4) short-term post encouragement, 5) medium-term post encouragement, 6) longer term post encouragement, and 7) comparison sample baseline.

+ and − indicate values that are significantly greater and lesser than the baseline.

indicates primed items

The first period of data collection represents the initial study which took place over approximately 10 weeks (for each health worker). The second period, a follow-up study, took place over a year later. In the Period 1, we visited all clinics in the urban and peri-urban areas of Arusha, Tanzania and enrolled all clinicians that we could find working in the OPD clinics of facilities that had a reasonable number of patients per day (at least 5). This resulted in a sample of 96 clinicians in 40 health care facilities including clinicians working in public, private, and non-profit/charitable facilities. The term “clinician” refers to primary health workers who provide outpatient care. All clinicians have significant medical training but the majority of them do not have full medical degrees.

All clinicians in the sample consented to be in a study (103 clinicians were contacted but 1 refused consent and 5 consented but were reposted before the study began). Although clinicians knew they were in a study, they did not know how or when we were going to begin collecting data. By visiting clinics where these clinicians worked and interviewing patients who were leaving the clinic after being consulted, we were able to measure the baseline level of protocol adherence without clinicians knowing that we were measuring adherence. This sample of 96 clinicians, unaware that their activities were measured comprise the baseline sample which is an unbiased estimate of protocol adherence in the absence of treatment.

One and a half years later, we tried to find all the clinicians in the sample at their original places of work and found 45 clinicians still practicing in the same facility. This group of clinicians represents the treated sample and we measured the quality of care provided at this point. At the same time, we enrolled a new sample of 97 clinicians at the same facilities where we found the follow-up sample. By construction, this comparison sample was not part of the initial study.

This process results in three samples: (1) the baseline sample (96 clinicians), which consists of clinicians measured before they had received any intervention in the first period; (2) the treated sample (45 clinicians) which consists of clinicians measured in the follow-up survey who were also measured in the baseline; and (3) the comparison sample (97 clinicians) which consists of clinicians measured only in Period 2. The CONSORT diagram for these three samples is shown in Figure 1. Note that in the diagram, clinicians are sorted by whether they were found at the follow-up and then selected into treatment (or not). In reality, all clinicians in the baseline went through the initial stage of the treatment but we only use the baseline data for this group and the CONSORT diagram represents this group as not treated. In this paper we examine the effect of the treatment on the treated sample first by comparing the treated sample at the follow-up to the baseline sample and the comparison sample and second by comparing clinicians in the treated sample to themselves at the baseline.

Figure 1.

Consort Flow Diagram

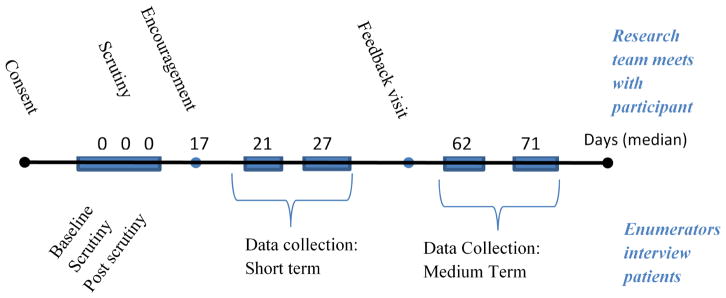

The treatment involved of a series of phases, lasting about 10 weeks overall. The original design was based on the idea that, in an urban area, an encouraging visit from a peer was a policy relevant intervention only if the impact was still visible at least two weeks later. We expected the impact to decline thereafter and planned to use the medium-term data collection visits to estimate the rate of decline. Figure 2 shows the steps followed with each clinician in the treatment. Activities are divided into two broad categories: those in which our team had direct contact with the clinician (shown on top of the timeline) and those in which we had contact only with patients (shown below the timeline). First, clinicians were enrolled (providing consent) and then shortly after were visited by a research team that measured the quality of care under normal circumstances (baseline), with a clinician observer in the room (scrutiny) and then immediately after the observer left the room (post-scrutiny). On the day of this visit, the first time a clinician would know that the research team was there would be during the scrutiny visit, when a member of our team introduced themselves and took a seat in the room. After the observer left the room (post-scrutiny) the clinician might believe we had left, or know that we were continuing to interview patients. Importantly clinicians could not know the team was present during the initial baseline part of this first visit day.

Figure 2.

Activities of the Encouragement Study

About two to three weeks (a median of seventeen days) after this one-day intensive visit, a Tanzanian doctor on the research team (a peer) visited the clinician and read an encouragement script (see Figure 3). The encouragement script told clinicians that protocol was important and mentioned five specific (primed) items chosen because previous studies had found that most good clinicians included them and few poor clinicians did. The primed items were (1) telling the patient their diagnosis, (2) explaining the diagnosis in plain language, and (3) explaining whether the patient needs to return for further treatment, (4) asking if the patient has received treatment elsewhere or taken any medication, and (5) checking the patient’s temperature, and checking their ears and/or throat when indicated by the symptom. The first three health education items and general history taking question apply to all cases, that checking the temperature applies to all cases presenting with a fever, cough or diarrhea and that checking the ears and/or throat applies to all cases that present with a cough. Within the following two weeks, enumerators visited on two separate occasions to measure the short-term response in protocol adherence. Following these data visits, half of the clinicians received a feedback visit (randomly assigned at the clinician level). Finally, each clinician was visited again twice to measure the medium-term response of protocol adherence. These visits took place between 6 to 8 weeks after the encouragement visit.

Figure 3.

Encouragement Script

The enumeration team never alerted clinicians that they were present and, because they could catch patients who were leaving the facility, at least the first few patients interviewed had received their consultations before the team even arrived. Thus, the quality measures do not reflect an instantaneous reaction to the team’s presence. Importantly, we also control for the order of patients seen for each clinician in the course of the visit (usually five patients per visit) as a test of whether or not the measures reflect the fact that the clinician was alerted to the team’s presence. If clinicians detect the research team during the visit, quality should increase with the order of patients. The results below demonstrate adherence does not increase over this period, verifying that the team was not detected in any way that would lead to immediate improvements in quality. However, field reports from the teams suggest that health facility staff eventually realized there was someone there from the team and reported this to the health worker being studied. The awareness that the team had been present may have lead health workers to change behavior after the visit, but did not affect that data already collected. Importantly, the fact that clinicians knew they were being repeatedly visited likely contributed significantly to the medium and long-term response to the study.

Quality of care is measured by the proportion of items required by national protocol that are implemented in the consultation, as reported in the RCR survey. We include four measures of protocol adherence:

Overall: the raw percentage of items provided out of all items required for protocol given the patient’s age and presenting symptoms

Primed items: the raw percentage of items required by protocol that were mentioned in the encouragement script.

Non-primed items: the raw percentage of items required by protocol that were not mentioned in the encouragement script.

Overall Effect Size: the sum of items provided, weighted by the standard deviation of that item in the whole sample, divided by the maximum possible score. The effect size over-represents protocol items that have widely divergent adherence and underweights items to which almost all (or almost no) clinicians adhere.

We analyze the changes in quality using a mixed effects model with random effects at the facility level and random or fixed effects at the clinician level. Random effects at the facility level reflect the fact that patients sort according to facility. The use of fixed effects at the clinician level is essentially modeling the change in quality for a given clinician across the various treatments in the experiment. The effects of the treatment are measuring as dummy variables. We control for characteristics of the patient that might independently impact the protocol adherence: the age category of the patient (infant, child and adult); the presenting symptoms (fever, cough, and diarrhea); gender of the patient and a quadratic specification for the time of day (to control for the fact that the sickest patients usually report early in the morning).

3 Results

In this section, we first examine the three samples in order to establish that, in the baseline, they are similar. Then we compare the impact of treatment on the treated sample observed at least 18 months after they completed the initial study (the treated sample at the follow-up visit) and compare protocol adherence at this point to the baseline and comparison samples. In other words, clinicians treated in Period 1 and observed in Period 2 are compared to untreated clinicians in both Period 1 and Period 2. Finally, we compare the treated clinicians only to themselves in the baseline and examine how the protocol adherence evolves over the course of the treatment.

3.1 Comparing the samples

Table 1 shows the balance tables for clinicians and patients across the three different samples. Recall that the difference between the baseline and the treatment sample is that all clinicians in the treatment sample were still in the same location almost two years later, whereas over half of the clinicians in the baseline sample could not be located two years later. However both samples represent the conditions at the baseline in Period 1. The comparison sample includes the new clinicians in Period 2.

Table 1.

Sample Averages at Baseline

| Samples | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| baseline | treatment | comparison | p-value of comparison | |||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | 1 vs. 2 | 1 vs. 3 | 2 vs. 3 | |

| Characteristics of the average health worker | ||||||

| Individual Health Worker Protocol Adherence Scores in the baseline | ||||||

| Overall | 0.755 (0.019) | 0.740 (0.031) | 0.732 (0.019) | 0.667 | 0.394 | 0.818 |

| Primed items | 0.741 (0.023) | 0.709 (0.036) | 0.715 (0.020) | 0.450 | 0.396 | 0.879 |

| Non-primed Items | 0.780 (0.015) | 0.768 (0.023) | 0.799 (0.014) | 0.642 | 0.358 | 0.224 |

| Overall effect size | 0.698 (0.021) | 0.676 (0.034) | 0.664 (0.020) | 0.567 | 0.245 | 0.747 |

| Observations | 96 | 45 | 97 | |||

| Characteristics of the average consultation | ||||||

| Baseline Protocol Adherence for consultations seen at baseline and after treatment | ||||||

| Overall | 0.728 (0.008) | 0.729 (0.012) | 0.730 (0.007) | 0.968 | 0.879 | 0.937 |

| Primed items | 0.712 (0.009) | 0.703 (0.014) | 0.706 (0.007) | 0.584 | 0.595 | 0.852 |

| Non-primed Items | 0.759 (0.006) | 0.761 (0.009) | 0.799 (0.005) | 0.829 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Overall effect size | 0.666 (0.009) | 0.667 (0.013) | 0.662 (0.008) | 0.975 | 0.729 | 0.754 |

| Characteristics of the patient and caregiver | ||||||

| gender (female = 1) | 0.534 (0.021) | 0.573 (0.029) | 0.543 (0.021) | 0.276 | 0.762 | 0.402 |

| Age | 21.734 (0.648) | 23.098 (0.890) | 23.586 (0.664) | 0.217 | 0.046 | 0.664 |

| Child (5 to 15) | 0.181 (0.016) | 0.187 (0.022) | 0.162 (0.015) | 0.840 | 0.389 | 0.357 |

| Adult (15+) | 0.639 (0.020) | 0.672 (0.027) | 0.680 (0.019) | 0.325 | 0.135 | 0.804 |

| Age of caretaker | 31.230 (0.410) | 32.505 (0.561) | 32.241 (0.417) | 0.068 | 0.084 | 0.709 |

| Gender of caretaker (female = 1) | 0.654 (0.020) | 0.693 (0.027) | 0.658 (0.020) | 0.243 | 0.887 | 0.294 |

| Fever | 0.259 (0.018) | 0.226 (0.024) | 0.222 (0.017) | 0.278 | 0.137 | 0.892 |

| Cough | 0.178 (0.016) | 0.187 (0.022) | 0.154 (0.015) | 0.743 | 0.267 | 0.208 |

| Diarrhea | 0.059 (0.010) | 0.069 (0.015) | 0.063 (0.010) | 0.577 | 0.779 | 0.748 |

| Infant fever | 0.100 (0.012) | 0.108 (0.018) | 0.091 (0.012) | 0.702 | 0.584 | 0.400 |

| Infant cough | 0.073 (0.011) | 0.075 (0.015) | 0.063 (0.010) | 0.891 | 0.513 | 0.493 |

| Infant diarrhea | 0.019 (0.006) | 0.039 (0.011) | 0.034 (0.008) | 0.064 | 0.097 | 0.695 |

| time of day | 11.220 (0.063) | 11.316 (0.084) | 11.373 (0.066) | 0.365 | 0.094 | 0.605 |

| Observations | 590 | 305 | 585 | |||

The first four rows of the table examine the characteristics of clinicians. Overall there is no difference in the baseline adherence across the samples by any of the measures. Note that by all four quality measures, the treatment sample is insignificantly worse than the baseline sample. This suggests that clinicians who we found almost two years later were different from those we could not find.

The second part of the table examines the characteristics of patients seen in each of the three samples: at the baseline for the baseline sample, after treatment for the treated sample and at the baseline for the comparison sample. Note that the characteristics of clinicians are those that existed at the baseline. In other words, for the baseline sample the average consultation involved a visit to a clinician with a baseline overall adherence of 72.8%, for the treated sample the average consultation (in Period 2 after the treatment) involved a visit to a clinician with a baseline overall adherence (measured in Period 1) of 72.9%, and for the comparison sample, the average consultation (in Period 2) involved a visit to a clinician with a baseline overall adherence (measured in Period 2) of 73.0%. By this consultation weighted measure of clinician quality we see that clinicians in the comparison sample had higher protocol adherence for non-primed items than either the baseline or treated sample. This same difference was evident in the first part of the table, but since the number of observations is much higher when we weight for consultations, it is now significant.

The average patient across the three samples is between 22 and 24 years old and the proportions in different age categories are similar: about 64% are adults, 18% are children and 18% are infants. About 26% report with a fever as the primary symptom compared to 18% with a cough and 6% with diarrhea. Infants are most likely to report with a fever and most of the remaining infants have either a cough or diarrhea. Note that 64% of non-infants and 30% of infants report with primary symptoms other than fever, cough or diarrhea. Patients are almost evenly split between men and women but caregivers (which includes the patient if the patient is an adult) are much more likely to be female.

Note that the average patient in the second period is accompanied by a slightly older caretaker and is almost as twice as likely to be an infant suffering from diarrhea. These patient characteristics represent changes taking place in the population of patients over the one and a half year gap between the two periods, but are not present in the difference between the treated and the comparison samples (which were both collected at the same time). In addition, the data collected in Period 2 was collected about 10 minutes later in the day.

Overall, we see that there are no significant differences across the clinicians in the three samples, except that the comparison sample of clinicians has a slightly higher adherence to non-primed items. In addition, patient characteristics do not change markedly over this period. The changes in the type of presenting conditions are controlled for in all subsequent regressions. Importantly, even though there are no significant difference across clinicians in the three samples, we will be deliberately sensitive to the fact that clinicians in the treated sample appear marginally worse (at the baseline) than other clinicians in the baseline sample.

3.2 Comparing the long-term impact of treatment to the baseline and comparison samples

Table 2 examines the long-term impact of the treatment (about a year and a half after the treatment ended) by comparing this level of quality to both the original baseline and the comparison sample. Table 2 shows the levels of protocol adherence across the three samples, with the baseline sample divided into clinicians who are eventually part of the treatment sample and clinicians who are not part of the treatment sample. The baseline adherence for the treated sample is shown as the base category and the other three samples are shown with marginal coefficients (the difference from the base category). The four columns report the results for the four different quality scores. For the overall score and for the overall effect size, the follow-up sample is significantly better than the baseline for the treated clinicians (by about 6 and half percentage points) but neither of the other two baseline samples are significantly different. Table 2 also shows the p-value of the test that the follow-up sample for the treated group is not significantly different than the baseline for the comparison group. For both the overall score and the overall effect size, this hypothesis is rejected. In other words, the treated sample observed at follow-up shows higher quality care compared to its own baseline and compared to the comparison sample. The result for non-primed items is similar: the effect of treatment is positive and the follow-up for the treated sample is significantly better than both the baseline for the treated and the comparison sample. For primed items however, the treated sample (though significantly better than at the baseline) is not significantly better than the comparison sample. In this case we cannot rule out the possibility of a secular trend increasing adherence to the items primed in the encouragement script, even for clinicians who were never exposed to any treatment.

Table 2.

Comparing original sample to the comparison sample

| Dependent Variable: Protocol Adherence | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | primed items | non-primed items | Overall effect size | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

|

| ||||

| Baseline for treatment sample | 0.727 (0.025)*** | 0.695 (0.027)*** | 0.760 (0.019)*** | 0.663 (0.027)*** |

| Marginal effects (difference from the treated sample at the baseline) | ||||

| Baseline for clinicians not found at follow-up | 0.045 (0.033) | 0.083 (0.035)** | 0.033 (0.024) | 0.057 (0.036) |

| Baseline for comparison sample | 0.01 (0.029) | 0.031 (0.031) | 0.044 (0.020)** | 0.006 (0.031) |

| Follow-up for treatment sample | 0.065 (0.020)*** | 0.049 (0.021)** | 0.079 (0.014)*** | 0.063 (0.021)*** |

| Observations | 1477 | 1474 | 1475 | 1480 |

| p-value of test that follow-up for treatment sample is equal to baseline for comparison sample | 0.059 | 0.566 | 0.087 | 0.071 |

Protocol adherence is the percentage of items required by protocol used, as reported by the patient. Each coefficient is the percentage point increase in adherence from a baseline adherence. Mixed effects regression with health worker and facility random effects. Sample includes all clinicians seen in the baseline, all clinicians in the control group and all observations for clinicians seen in the follow-up visit. Standard errors in parenthesis:

indicates

p<0.01,

p<0.05,

p<0.1

3.3 Impact of the encouragement

Table 3 examines adherence for the 45 clinicians in the treatment sample, following them across 6 different stages: 1) the baseline, 2) when subject to the scrutiny of a peer, 3) immediately after the peer leaves the room (post-scrutiny), 4) about one week after the encouragement visit (short-term post encouragement), 5) six weeks after the encouragement visit (medium-term post encouragement) and 6) over a year later (long-term post encouragement). In addition to the previous control variables we include a variable indicating whether the clinician received a randomly assigned feedback visit interacted with the two measurement periods after the feedback visit to test if having received feedback increased protocol adherence after that visit. Note that all coefficients are interpreted as the percentage point change in quality from the baseline.

Table 3.

Impact of the study and follow up on treated clinicians

| Dependent Variable: Percentage point increase in protocol adherence above the baseline | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | primed items | non-primed items | Overall effect size | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

|

| ||||

| Impact of initial interventions | ||||

| Scrutiny | 0.045 (0.020)** | 0.056 (0.023)** | 0.03 (0.014)** | 0.045 (0.019)** |

| Post-Scrutiny | 0.006 (0.022) | 0.007 (0.027) | 0.022 (0.016) | 0.009 (0.022) |

| Impact of encouragement intervention | ||||

| Short-term post enc. | 0.051 (0.021)** | 0.107 (0.025)*** | 0.055 (0.014)*** | 0.062 (0.020)*** |

| Feedback received | 0.002 (0.018) | 0.013 (0.022) | 0.001 (0.013) | 0.011 (0.018) |

| Medium-term post enc. | 0.114 (0.023)*** | 0.187 (0.027)*** | 0.084 (0.016)*** | 0.125 (0.023)*** |

| Long-term post enc. | 0.073 (0.023)*** | 0.067 (0.028)** | 0.097 (0.016)*** | 0.066 (0.023)*** |

| Impact of patient order (testing for detection of research team during data visit) | ||||

| patient order by day | 0.000 (0.002) | 0.006 (0.003)** | 0.003 (0.002)* | 0.002 (0.002) |

| patient order after enc. | −0.005 (0.003)* | −0.008 (0.003)** | −0.005 (0.002)** | −0.005 (0.003)* |

| Clinician effects | clinician fixed effects included | |||

| Patient effects | patient and illness type characteristics included | patient chars included | ||

| N (patients) | 2556 | 2555 | 2554 | 2557 |

Protocol adherence is the percentage of items required by protocol used, as reported by the patient. Each coefficient is the percentage point increase in adherence from a baseline average of 73%. Sample includes health workers seen in each of both rounds.

The model is a mixed effects regression with health worker fixed effects and facility random effects. Standard errors in parenthesis:

indicates

p<0.01,

p<0.05,

p<0.1

Column 1 (overall adherence) shows that adherence increased during the scrutiny visit by four and a half percentage points over the baseline. After the observer left the room, adherence fell back to a point where it was not statistically different than the baseline. The short-term impact of encouragement is similar to the impact of scrutiny (a five percentage point increase in quality). The medium-term impact after the encouragement is larger than the short-term impact (about 11 percentage points greater than the baseline). The coefficient measuring the impact of feedback shows that the feedback itself had no impact on quality: clinicians increased quality as the study continued at the same rate whether or not they had received any feedback. Almost two years later, quality is still significantly higher than in the baseline, though less than the medium-term. In addition, by examining the impact for primed and non-primed items (Columns 2 and 3), we can see that the character of the response has changed over this period. Initially the biggest impact was for the items explicitly mentioned in the script, but 18 months later, there is a larger impact on the items that were not mentioned.

3.4 Heterogeneous Impacts

In this section we examine the results for the treated sample broken into different ages for patients and separated into clinicians who are above and below the median baseline adherence.

Table 4 shows the results for four different groupings of ages: infants, children (between 5 and 14), the combination of infants and children, and adults (anyone over 15). The table examines the results for the treated sample using the same framework and controls as Table 3. The results for adults are much weaker than for other ages and, except for the medium-term impact of the encouragement, are not significant. This is driven by the fact that adults are less likely than children and infants to present with conditions for which protocol is easy to establish (such as cases presenting with fever, cough or diarrhea). This might mean that clinicians don’t improve their care because protocol is less clear, but it could just as easily mean that our instruments fail to capture improvements in quality because adherence is more difficult to measure. More importantly, the results for infants and children are much stronger than the full sample and protocol adherence appears to be increasing by almost 20 percentage points by some measures, and between 16 and 18 percentage points even a year and a half after the study was completed. These are relevant and large improvements for a vulnerable population.

Table 4.

Impact of treatment by age of patient

| Dependent Variable: Protocol adherence | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infants (<5) | Children (5–14) | Infants & Children | Adults (15+) | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Impact of initial interventions | ||||

| Scrutiny | 0.126 (0.040)*** | 0.016 (0.047) | 0.074 (0.031)** | 0.024 (0.025) |

| Post-Scrutiny | 0.103 (0.048)** | 0.012 (0.051) | 0.049 (0.036) | −0.013 (0.029) |

| Impact of encouragement intervention | ||||

| Short-term post enc. | 0.061 (0.049) | 0.073 (0.054) | 0.085 (0.037)** | 0.036 (0.025) |

| Feedback received | −0.034 (0.043) | −0.023 (0.047) | −0.036 (0.032) | 0.019 (0.022) |

| Medium-term post enc. | 0.197 (0.054)*** | 0.18 (0.060)*** | 0.206 (0.041)*** | 0.078 (0.028)*** |

| Long-term post enc. | 0.163 (0.056)*** | 0.168 (0.057)*** | 0.187 (0.041)*** | 0.014 (0.028) |

| Impact of patient order (testing for detection of research team during data visit) | ||||

| patient order by day | −0.010 (0.005)* | 0.010 (0.005)** | 0.002 (0.004) | 0.000 (0.003) |

| patient order after enc. | 0.001 (0.007) | −0.011 (0.007) | −0.007 (0.005) | −0.005 (0.004) |

| Clinician effects | clinician fixed effects included | |||

| Patient effects | patient and illness type characteristics included | |||

| N (patients) | 453 | 411 | 864 | 1692 |

Protocol adherence is the percentage of items required by protocol used, as reported by the patient. Each coefficient is the percentage point increase in adherence from a baseline average of 73%. Sample includes health workers seen in each of both rounds.

The model is a mixed effects regression with health worker fixed effects and facility random effects. Standard errors in parenthesis:

indicates

p<0.01,

p<0.05,

p<0.1

Table 5 shows the impact by two different types of clinicians in the treated sample. To classify clinicians we look at the average protocol adherence for both the baseline visit and the post-scrutiny visit. We include the post-scrutiny visit because Table 3 suggests the quality observed during this visit is not different from the quality observed in the baseline and the combination of two visits creates a baseline score more reliably. Then we classify clinicians into those above and those below the median adherence to quality. Table 5 shows that clinicians above the median decreased quality and clinicians below the median increased quality. This overall effect could be caused by mean reversion, particularly considering that clinicians with very high level of adherence cannot significantly improve quality because it is bounded at 100%. Note however, that for clinicians below the median, quality continues to increase over the course of the study (suggesting a real trend) whereas for those above the median the pattern is less clear (which is more consistent with mean reversion).

Table 5.

Impact of Treatment differentiated by baseline score

| Dependent Variable: Protocol adherence | ||

|---|---|---|

| clinicians below median | clinicians above median | |

| (1) | (2) | |

| Impact of initial interventions | ||

| Scrutiny | 0.058 (0.025)** | 0.013 (0.019) |

| Impact of encouragement intervention | ||

| Short-term post enc. | 0.099 (0.030)*** | −0.012 (0.025) |

| Feedback received | 0.010 (0.030) | 0.041 (0.021)* |

| Medium-term post enc. | 0.185 (0.034)*** | 0.009 (0.028) |

| Long-term post enc. | 0.184 (0.034)*** | −0.076 (0.029)*** |

| Impact of patient order (testing for detection of research team during data visit) | ||

| patient order by day | −0.006 (0.003)* | 0.007 (0.003)*** |

| patient order after enc. | −0.005 (0.004) | −0.005 (0.003) |

| Clinician effects | clinician fixed effects included | |

| Patient effects | patient and illness type characteristics included | |

| N (patients) | 1374 | 1182 |

Protocol adherence is the percentage of items required by protocol used, as reported by the patient. Each coefficient is the percentage point increase in adherence from a baseline average of 73%. Sample includes health workers seen in each of both rounds.

The model is a mixed effects regression with health worker fixed effects and facility random effects. Standard errors in parenthesis:

indicates

p<0.01,

p<0.05,

p<0.1

Although there might be some mean reversion in this pattern, for the clinicians who were initially of lower quality we see large improvements in the quality score, approaching 20 percentage points in the medium and the long-term. Note that the 25th, 50th and 75th percentiles at the baseline were at 65%, 75% and 88% adherence which suggests that a clinician at the 25th percentile improves their adherence enough to reach the 75th percentile of the original distribution. These are important changes in the distribution of quality in our sample.

4 Discussion

Using a simple intervention in which health workers were told how they were expected to improve, encouraged to improve and then received regular visits to measure quality, we show that clinicians react both to direct observation and to the scrutiny implied by having quality repeatedly measured. Clinicians improved protocol adherence immediately when someone entered the room without any new training, equipment or incentives and, as soon as the peer leaves, they return to normal—a classic Hawthorne effect. These same clinicians react even more strongly to being part of a project that encouraged quality, increasing the quality of care in the short, medium and long-term. For a sub-sample that we were able to locate 18 months after the study had ended, we find that quality was still higher by between five and seven percentage points. The improvements in quality for this sample can be seen by comparing clinicians to themselves in the baseline or by comparing clinicians to a new sample of clinicians who never received any encouragement.

The study was designed to see if clinicians increased the quality of care in the short-term: the medium-term data was collected with the expectation that quality would fall within a few weeks of encouragement. We differentiated between primed items and non-primed items in order to test for task shifting, where clinicians increase adherence for items that were specifically mentioned and simultaneously decrease adherence for items that were not mentioned. We included feedback for half the sample to test whether feedback led clinicians to increase adherence. All of our hypotheses—short-term reaction only, task shifting away from non-primed items and positive responses to feedback—were rejected.

Surprisingly, the medium-term reaction is larger than the short-term reaction and even larger than the initial Hawthorne effect. Additionally, although clinicians do increase adherence for items mentioned in the script, they also increase adherence for items that were not mentioned in the script. In the short and medium-term, the reaction for primed items is double that of non-primed items, but in the long-term, the response to primed items is actually lower than the response for non-primed items. Additionally, the average clinician does not react to feedback at all (either positively or negatively). And finally, the improvements in protocol adherence can still be seen almost two years later.

We hypothesize that encouragement, delivered by a peer, sets expectations for clinicians. Initially, these expectations had little meaning because there were no incentives to meet the expectations and this project might have appeared similar to most other projects used in health care: short-term with little expectation of follow-up. However, the research team continued to return to measure quality and clinicians knew they were returning. There was no direct contact with a peer but our measurement method created an indirect link through patient interviews: clinicians knew that peers would evaluate their care for an unknown sample of their patients and that the reports of their patients were the only way to gain or retain the esteem of these peers. Our project served as a continual, subtle reminder of expectations and these expectations, set at the encouragement visit, increased in importance.

However, they did not react narrowly to our encouragement by increasing adherence only for items that we mentioned: they increased their adherence overall. This might be because specific items of protocol adherence are complements: doing more of one thing leads to doing more of other things as well. It could also be the case that clinicians know protocol and know that all items in protocol are important: the feeling of being encouraged and measured causes a general increase in willingness to exert effort on behalf of patients.

Finally, the fact that clinicians were nudged to providing higher quality had lasting impacts even after the measurement stopped. Maybe the patients of these clinicians noticed and were appreciative, or maybe the clinicians themselves observed that they were experiencing better outcomes. Somehow they did not return to normal after this experience.

The changes observed in the quality of care observed significant. The standard deviation of average quality provided is about 17 percentage points, implying that the long-term impact of the project was to increase quality by between a third and a half of a standard deviation. In a systematic review of the impact of audit and feedback interventions, Ivers et al (2012) find an average reduction in non-compliant behavior of 7%, whereas our improvements translate to approximately 18% reduction in non-compliance. Importantly, even though success for performance-based financing in developing countries is sparsely documented (Witter, Fretheim, Kessy, & Lindahl, 2012), one of the best documented successes of the performance-based financing literature (Basinga et al., 2011) shows a 0.14 standard deviation increase in adherence, significantly less than we found in our study.

Indeed, the comparison to PBF is particularly apt, given the design of the study. Evidence from many on-going trials suggests that PBF is transforming the health sectors of many developing countries (Fritsche, Soeters, & Meessen, 2014). Overall, this project included many of the elements that we would expect to find in a PBF program that addressed similar issues: explaining the program, setting expectations, providing accountability and emphasizing autonomy (Miller & Babiarz, 2013). Furthermore the fact that services in PBF schemes are clearly described and measured could be considered, by itself, a form of training. As much of the previous research has demonstrated that each of these elements alone can improve quality, should it be surprising that combining them has positive impacts?

However, unlike many other programs, the PBF scheme does not end: outputs and quality continue to be measured and there is no expectation that effort would remain high if the program ended. Even if constant attention improves measured outcomes, PBF might face the problem that when you use an indicator both to measure impact and reward behavior, the incentive to manipulate data will eventually make the measurement less accurate (an effect referred to as Campbell’s law (Campbell, 1979)). On the other hand, in our study, there are no tangible rewards to increasing adherence to primed items, and we find that, in the long-term, there are improvements for quality items that clinicians did not know we were tracking as well as for items they did know we were tracking. Without explicit rewards, Campbell’s law may not apply.

This suggests a view of health workers as being broadly motivated by the opinion of their peers. A number of studies have shown that improved prosocial motivation (caring about the welfare of others or caring about the opinion of others) results in higher quality care (Delfgaauw, 2007; Kolstad, 2013; Prendergast, 2007; Serra, Serneels, & Barr, 2010; Smith et al., 2013). Importantly, this prosocial motivation exists independent of the work environment. For example, Leonard and Masatu (2010) and Brock, Lange and Leonard (2016) describe a form of latent professionalism in which individuals understand professional norms but follow them only when they believe their fellow professionals can observe or evaluate their behavior. Peabody et al (2014) and Quimbo et al (2015) show that rewarding hospitals for the improved scores of their doctors on clinical performance vignettes (CPVs) leads to increases in both these scores and hospital level outcomes, even in the absence of incentives to improve outcomes. The authors hypothesize that peer pressure within the hospital encourages doctors to improve their scores. Similarly, Kolstad (2013) demonstrates that access to information comparing one’s own performance to the performance of peers leads to significant improvements in quality for many surgeons, again without any additional incentives to improve.

We suggest that the reaction to being measured demonstrates the significant role that constant attention can have on the quality of care provided in a developing or transition country setting. However the form of attention may be particularly important: this study did not involve direct contact with peers and did not involve reconstruction of quality from reviews of existing records. Rather, we collected data at a slight distance, through patients. We find that feedback did not improve quality (except possibly for clinicians with high levels of quality), and that health workers returned to normal levels of care immediately after being visited by a peer, suggesting that direct scrutiny does not lead to long-term improvements. Instead it may be that the constant measurement of quality at a slight distance allowed health workers the opportunity to enjoy the satisfaction of having chosen to improve their care and having this choice observed by a peer. This is a very different reaction than that of a health worker who feels pressured to please someone, and it may be more sustainable in the long-term. A systematic review of evidence on the value of supervision suggests a key tension in supervision. “In the policy documents, the central role of supervision in performance and motivation was clear. In the field reports [however], the central role of administrative checking, and examination of records of activities … suggests a level of control around ‘checking up’ on people.” (Bosch-Capblanch & Garner, 2008, p. 374) This contrast is apparent in Tanzania. Although supervision is supposed to include supportive discussions around problem solving, the fact is that supervisors are unable to visit facilities as frequently or as long as is optimal and since the visits must also include checking up on supplies and other input measures, it is likely that little time is spent in tasks that can be construed as encouragement. Despite the fact that all clinicians in this study are supervised, the significant remaining know-do gap was relatively easy to close with encouragement and scrutiny from a single-tasked, independent peer using a small team of easily trained enumerators.

Highlights.

Repeated measurement with simple expectations can improve quality of care.

Benefits of the program were significant over a year after the program ended.

The program succeeded despite the absence of training, materials or incentives.

Clinicians were primed to improve in specific areas but benefits are seen across all measured areas.

The know-do gap closes with this form of independent supportive supervision.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by a Maryland Agricultural Extension Station seed grant, a contract from the Human Resources for Health Group of the World Bank, (in part funded by the Government of Norway), and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Center for Child Health and Human Development grant R24-HD041041 through the Maryland Population Research Center. This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Maryland: 08-457.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Kenneth L Leonard, Associate Professor, Department of Agricultural and Resource Economics, University of Maryland, College Park, Maryland, 20740 USA.

Melkiory C. Masatu, Acting Principal, Centre for Educational Health in Development, Arusha (CEDHA), PO Box 1162 Arusha, Tanzania

References

- Basinga P, Gertler PJ, Binagwaho A, Soucat AL, Sturdy J, Vermeersch CM. Effect on maternal and child health services in Rwanda of payment to primary health-care providers for performance: an impact evaluation. The Lancet. 2011;377(9775):1421–1428. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60177-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black RE, Morris SS, Bryce J. Where and why are 10 million children dying every year? The Lancet. 2003;361(9376):2226–2234. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13779-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosch-Capblanch X, Garner P. Primary health care supervision in developing countries: Supervision of health services in developing countries. Tropical Medicine & International Health. 2008;13(3):369–383. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2008.02012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brock J, Lange A, Leonard KL. Generosity and Prosocial Behavior in Health-Care Provision: Evidence from the Laboratory and Field. Journal of Human Resources. 2016;51(1) [Google Scholar]

- Campbell DT. Assessing the impact of planned social change. Evaluation and Program Planning. 1979;2(1):67–90. [Google Scholar]

- Das J, Gertler PJ. Variations in practice quality in five low-income countries: a conceptual overview. Health Affairs (Project Hope) 2007;26(3):w296–309. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.3.w296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das J, Hammer J. Money for nothing: The dire straits of medical practice in Delhi, India. Journal of Development Economics. 2007;83(1):1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Delfgaauw J. Dedicated Doctors: Public and Private Provision of Health Care with Altruistic Physicians. SSRN Electronic Journal 2007 [Google Scholar]

- Fritsche GB, Soeters R, Meessen B. Performance-Based Financing Toolkit. The World Bank; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Holloway KA, Ivanovska V, Wagner AK, Vialle-Valentin C, Ross-Degnan D. Have we improved use of medicines in developing and transitional countries and do we know how to? Two decades of evidence. Tropical Medicine & International Health: TM & IH. 2013;18(6):656–664. doi: 10.1111/tmi.12123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivers N, Jamtvedt G, Flottorp S, Young JM, Odgaard-Jensen J, French SD, … Oxman AD. Audit and feedback: effects on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2012;6:CD000259. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000259.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones G, Steketee RW, Black RE, Bhutta ZA, Morris SS Bellagio Child Survival Study Group. How many child deaths can we prevent this year? Lancet (London, England) 2003;362(9377):65–71. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13811-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolstad J. Information and Quality when Motivation is Instrinsic: Evidence from Surgeon Report Cards. American Economic Review. 2013;103(7):2875–2910. [Google Scholar]

- Leonard KL, Masatu MC. Outpatient process quality evaluation and the Hawthorne Effect. Social Science & Medicine (1982) 2006;63(9):2330–2340. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard KL, Masatu MC. Variations in the quality of care accessible to rural communities in Tanzania. Health Affairs (Project Hope) 2007;26(3):w380–392. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.3.w380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard KL, Masatu MC. Professionalism and the know-do gap: exploring intrinsic motivation among health workers in Tanzania. Health Economics. 2010;19(12):1461–1477. doi: 10.1002/hec.1564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller G, Babiarz KS. Pay-for-Performance Incentives in Low- and Middle-Income Country Health Programs. National Bureau of Economic Research; 2013. (Working Paper No. 18932) [Google Scholar]

- Peabody JW, Shimkhada R, Quimbo S, Solon O, Javier X, McCulloch C. The impact of performance incentives on child health outcomes: results from a cluster randomized controlled trial in the Philippines. Health Policy and Planning. 2014;29(5):615–621. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czt047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prendergast C. The Motivation and Bias of Bureaucrats. American Economic Review. 2007;97(1):180–196. [Google Scholar]

- Quimbo S, Wagner N, Florentino J, Solon O, Peabody J. Do Health Reforms to Improve Quality Have Long-Term Effects? Results of a Follow-Up on a Randomized Policy Experiment in the Philippines. Health Economics. 2015 doi: 10.1002/hec.3129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rethans JJ, Sturmans F, Drop R, van der Vleuten C, Hobus P. Does competence of general practitioners predict their performance? Comparison between examination setting and actual practice. BMJ. 1991;303(6814):1377–1380. doi: 10.1136/bmj.303.6814.1377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe AK, de Savigny D, Lanata CF, Victora CG. How can we achieve and maintain high-quality performance of health workers in low-resource settings? Lancet (London, England) 2005;366(9490):1026–1035. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67028-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serra D, Serneels P, Barr A. Intrinsic Motivations and the Non-Profit Health Sector: Evidence from Ethiopia. Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA); 2010. IZA Discussion Paper No. 4746. [Google Scholar]

- Smith R, Lagarde M, Blaauw D, Goodman C, English M, Mullei K, … Hanson K. Appealing to altruism: an alternative strategy to address the health workforce crisis in developing countries? Journal of Public Health (Oxford, England) 2013;35(1):164–170. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fds066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witter S, Fretheim A, Kessy F, Lindahl A. Paying for performance to improve the delivery of health interventions in low- and middle-income countries. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2012;(2) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007899.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]