Abstract

More than 100,000 community wells have been installed in the 150–300 m depth range throughout Bangladesh over the past decade to provide low-arsenic drinking water (<10 μg/L As), but little is known about how aquifers tapped by these wells are recharged. Within a 25 km2 area of Bangladesh east of Dhaka, groundwater from 65 low-As wells in the 35–240 m depth range was sampled for tritium (3H), oxygen and hydrogen isotopes of water (18O/16O and 2H/1H), carbon isotope ratios in dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC, 14C/12C and 13C/12C), noble gases, and a suite of dissolved constituents, including major cations, anions, and trace elements. At shallow depths (<90 m), 24 out of 42 wells contain detectable 3H of up to 6 TU, indicating the presence of groundwater recharged within 60 years. Radiocarbon (14C) ages in DIC range from modern to 10 kyr. In the 90–240 m depth range, however, only 5 wells shallower than 150 m contain detectable 3H (<0.3 TU) and 14C ages of DIC cluster around 10 kyr. The radiogenic helium (4He) content in groundwater increases linearly across the entire range of 14C ages at a rate of 2.5×10−12 ccSTP 4He g−1 yr−1. Within the samples from depths >90 m, systematic relationships between 18O/16O, 2H/1H, 13C/12C and 14C/12C, and variations in noble gas temperatures, suggest that changes in monsoon intensity and vegetation cover occurred at the onset of the Holocene, when the sampled water was recharged. Thus, the deeper low-As aquifers remain relatively isolated from the shallow, high-As aquifer.

AGU index terms: Groundwater hydrology, Stable isotope geochemistry, Chemistry of fresh water, Radioisotope geochronology, Water management

Keywords: Tritium, Radiocarbon, Noble gas temperatures, Arsenic, Bangladesh, Groundwater dating

1. Introduction

Arsenic is a naturally occurring toxic metalloid that is released from sediment to groundwater under anoxic conditions that prevail in the low-lying river and delta plain aquifers of South and Southeast Asia [Ravenscroft et al., 2009; Fendorf et al., 2010]. The majority of the rural population in Bangladesh, as in several other countries in the region, rely on privately-installed shallow tubewells for their drinking water supply. However, a large proportion of these wells contain As concentrations of >10 μg/L, exposing tens of millions of Bangladeshis and >100 million people throughout South and SE Asia to the harmful effects of As, including multiple forms of cancer, cardiovascular disease, and diminished childhood intellectual function [Smith et al., 2000; BGS/DPHE, 2001; Wasserman et al., 2004; Ravenscroft et al., 2009; Argos et al., 2010].

Exploiting the knowledge that peak As concentrations in the Bengal Basin are usually located 20–40 m below ground level (bgl), and that deeper, orange-colored sediments of Pleistocene origin usually host low concentrations of dissolved As in groundwater [BGS/DPHE, 2001; van Geen et al., 2003; Ravenscroft et al., 2005; McArthur et al., 2008; Fendorf et al., 2010], non-governmental organizations and government agencies have installed >100,000 deep (150–300 m bgl) wells in Bangladesh alone to mitigate the As poisoning [Ahmed et al., 2006; van Geen et al., 2007;; Michael and Voss, 2008; Burgess et al., 2010; DPHE/JICA, 2010; Ravenscroft et al., 2013]. Deeper wells appear to be an effective and available alternative for low-As drinking water supply in the short term [Ravenscroft et al., 2013; 2014]. As this source of low-As drinking water is increasingly pumped for urban supply and a cone of depression is developing around Dhaka [Hoque et al., 2007], several studies have raised concerns about the sustainability of its use. The possibility of vertical leakage of high-As and organic laden shallow groundwater due to irrigation pumping has been evaluated for deeper wells with basin-scale models under the assumption that in the coming decades pumping for irrigation purposes might switch to the currently safe aquifers at depths >150 m bgl [Michael and Voss, 2008; Burgess et al., 2010; Radloff et al., 2011].

The low-As aquifers have been characterized as Pleistocene in age or older, and their sediments have likely been flushed of labile As and/or organic carbon that could fuel the reductive release of As [BGS/DPHE, 2001; Ravenscroft et al., 2005]. The flushing presumably occurred due to a sequence of sea level lowstands, resulting in deep river channel incisions, larger horizontal hydraulic gradients in aquifers compared to the present, and consequently faster groundwater flow during the Pleistocene [Goodbred and Kuehl, 2000b; McArthur et al., 2008]. However, depth is a poor predictor for aquifers that are systematically low in As in the Bengal Basin because of the large hydrogeological heterogeneity of the delta [van Geen et al., 2003; Zheng et al., 2005; McArthur et al., 2008; Fendorf et al., 2010].

Previous studies have identified transitional aquifers, boundaries of which vary in depth, where groundwater As is low, but the residence times and other hydrogeochemical features may resemble those of the high-As aquifer, and “deep” aquifers typically found at greater depths that contain much older groundwater [Aggarwal et al., 2000; BGS/DPHE, 2001; Hoque and Burgess, 2012]. In this study, the transitional aquifer is referred to as “shallow” low-As aquifer (<90 m bgl), whereas the deeper aquifers are split into “intermediate” (90–150 m bgl) and “deep” (>150 m bgl) categories. These definitions account for the drilling method used for well installations, as well as the government’s Department of Public Health Engineering standard definition of wells deeper than 150 m as deep [van Geen et al., 2015; Choudhury et al., 2016]. The shallow aquifer designates the low-As aquifer that extends beneath the depth of peak As concentrations [van Geen et al., 2003] to the depth of ~90 m bgl, within the reach of the traditional hand-flapper installation method [Ali, 2003; Horneman et al., 2004]. Wells in the intermediate aquifer (90–150 m bgl) can no longer be installed by the hand-flapper technique but are shallower, and therefore less expensive to install, than the typical deep wells (>150 m bgl).

Despite concerns about the status of the deep aquifer [Hoque et al., 2007; McArthur et al., 2008; Michael and Voss, 2008; 2009a; b; Burgess et al., 2010; Fendorf et al., 2010; Mukherjee et al., 2011; Radloff et al., 2011], and a few reports of well failures [Aggarwal et al., 2000; van Geen et al., 2007] or presumed incursions of As and/or organic matter from Holocene aquifers [McArthur et al., 2011; Mukherjee et al., 2011], relatively little is known about the basic hydrology of the low-As aquifers, including flow patterns and mean residence times. Groundwater dating, primarily by 14C in dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC), has typically covered large areas with sparsely spaced data points [Aggarwal et al., 2000; BGS/DPHE, 2001; Fendorf et al., 2010; Majumder et al., 2011]. The available data indicate that low-As groundwater at depths >120 m bgl, and in certain locations at depths of only ~30 m bgl [Zheng et al., 2005], might be >10 kyr old. Previous studies that integrated spatial observations of deep groundwater ages have argued that deep aquifers are recharged by long flowpaths originating from the basin margins [Majumder et al., 2011; Hoque and Burgess, 2012], and such a conceptual model of flow has been successfully tested by the models of Michael and Voss [2008]. However, the above studies did not use multiple tracers and did not consider the potential impact of climate change at the Pleistocene to Holocene transition about 12 kyr ago.

In this study, we report tritium (3H) concentrations from 65 low-As wells ranging in depth between 35–240 m bgl in a 25 km2 area approximately 20 km east of Dhaka, Bangladesh. Radiocarbon ages based on DIC 14C data from a subset of 38 wells are interpreted using groundwater chemistry records, compared to a noble gas dating technique, and linked to the stable isotopic ratios in groundwater (2H/1H, 18O/16O, 13C/12CDIC). Field procedures and measurement techniques, litholog collection, and groundwater sampling and analyses for 3H, 13C/12C and 14C/12C (in DIC and dissolved organic carbon, DOC), major cations, anions, Si, P, As, Mn, Fe, DIC and DOC concentrations, 2H/1H, 18O/16O, and noble gases are described in Section 2. The results of these measurements and analyses, along with the 14C age correction models and the noble gas model used to calculate recharge temperatures and radiogenic He, are presented in Section 3. Section 4 provides a discussion of the main results, including groundwater chemistry and age/residence time estimates at different depths of the low-As aquifers. The isotopic ratios of the deepest and oldest samples are also placed into the context of deglaciation in early Holocene. The implications of our findings for the sustainability of deep, low-As aquifers are discussed before concluding the study in Section 5.

2. Methods

2.1. Field area and sampling campaigns

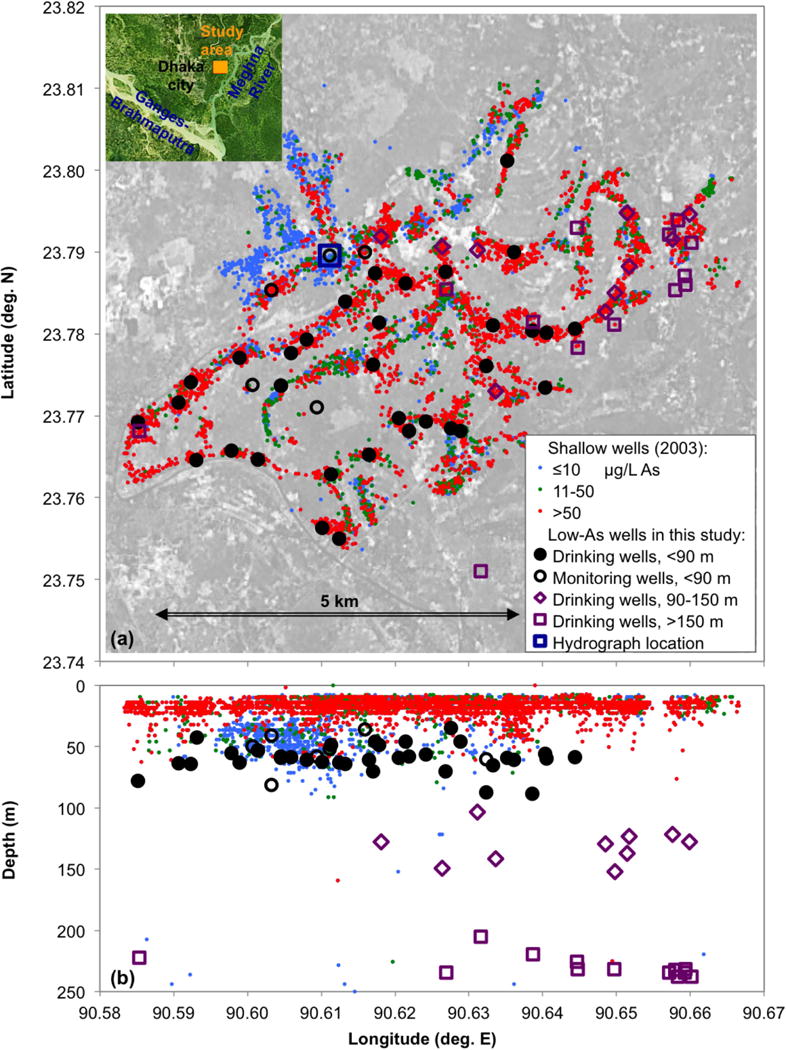

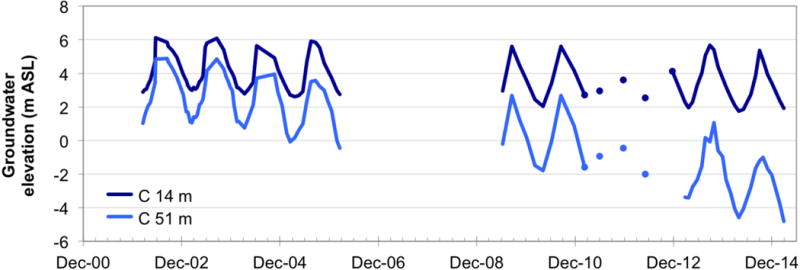

The study was conducted in Araihazar upazila approximately 20 km east of the capital, Dhaka, in an area described by van Geen et al. [2003] where the majority of shallow wells (mostly <30 m deep) exceed 50 μg/L As dissolved in groundwater (Fig. 1). This area has also seen decreasing water levels at depth (Fig. 2) likely due to depressurization caused by deep pumping in Dhaka, resulting in a growing downward vertical hydraulic gradient between the shallow, high-As and deeper, low-As aquifers. Recent data indicated that this gradient generally ranges from 0.01 to 0.03 in the study area, but averaged as high as 0.16 over the last year of measurements at the location shown in Figure 2. The present study focuses on 65 low-As wells (<10 μg/L As, except three wells with 10–29 μg/L As) that were installed in the depth ranges of 35–88 m bgl (n = 42), and 104–153 m bgl (n = 10), and 205–238 m bgl (n = 13) (Fig. 1, Table 1). A subset of the studied wells (n = 20 at the shallow depth, 35–90 m bgl, n = 6 at intermediate depth, 90–150 m bgl, and n=13 at depths >150 m bgl) was sampled for a broad series of chemical parameters, referred to here as extensive sampling, whereas the remaining wells were only sampled for 3H and/or water stable isotopes (18O and 2H).

Figure 1.

(a) Map of the field area in Araihazar upazilla, Bangladesh, and (b) depth distribution of the wells. The low-arsenic wells discussed in this work are marked by large circles, diamonds, and squares. In this figure, and hereafter, the data are plotted as black circles for low-As groundwater from shallow depth (<90 m bgl), open purple diamonds for intermediate aquifer (90–150 m bgl), and open purple squares for deep groundwater (>150 m bgl). In this figure only, the distinction is also made between drinking (filled circles) and monitoring wells (open circles) installed within the shallow low-As aquifer; in subsequent figures, all shallow samples are rendered as filled black circles. The small circles in the background show the distribution of surveyed private, mostly shallow tubewells [van Geen et al., 2003] and are color-coded for As concentrations. The orientation of Araihazar field area (red square) with respect to Dhaka, Bangladesh and the major rivers is indicated by the inset in map (a).

Figure 2.

Hydrographs of a very shallow, high-arsenic well (14 m bgl) and a shallow-depth, low-arsenic well (C5 in this study, 51 m bgl) at the location of multi-level nest C, designated by the large blue square in Fig. 1(a). Hydraulic head data since 2001 indicate a steadily declining water level of the deeper, low-As well, and thus an increasing downward vertical hydraulic gradient between the shallowest and the deepest wells at this site.

Table 1.

Well names, depths, and locations, along with lithological information, 3H and groundwater stable isotope (18O and 2H) concentrations.

| Well ID | Depth (m) | Lat (°N) | Long (°E) | Cumm. Claya (m) | Sand color | As (μg/L) | 2006 3H b (TU) | ± σ (TU) | 2010 3H (TU) | ± σ (TU) | 2011 3H (TU) | ± σ (TU) | δ2H (‰) | ± σ (‰) | δ18O (‰) | ± σ (‰) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CW28 | 34.7 | 23.76845 | 90.62760 | 6.1 | Orange | – | 2.01 | 0.04 | ||||||||

| E5 | 36.1 | 23.78999 | 90.61588 | 14.6 | Orange | 2.4 | 0.03* | 0.18 | −26.18 | 1 | −4.43 | 0.1 | ||||

| A7 | 40.7 | 23.78534 | 90.60322 | 15.2 | Orange | 0.0 | −0.30* | n/a | −33.28 | 1 | −5.20 | 0.1 | ||||

| CW39 | 42.7 | 23.76458 | 90.59310 | 15.8 | Orange | – | 0.63 | 0.04 | −37.41 | 1 | −5.60 | 0.1 | ||||

| CW27 | 45.7 | 23.76813 | 90.62888 | 18.9 | Orange | 0.0 | 6.15 | 0.13 | 4.44 | 0.08 | 4.94 | 0.10 | −21.56 | 0.04 | −3.68 | 0.02 |

| CW23 | 45.7 | 23.78743 | 90.61733 | 11.0 | Orange | 0.1 | 3.36 | 0.07 | 3.01 | 0.06 | −12.83 | 0.08 | −2.22 | 0.02 | ||

| CW9 | 45.7 | 23.78614 | 90.62142 | 14.6 | Orange | – | 0.42 | 0.05 | ||||||||

| CW24 | 48.8 | 23.78139 | 90.61780 | 29.3 | Orange | – | 0.21 | 0.05 | ||||||||

| CW37 | 48.8 | 23.76285 | 90.61137 | 18.3 | Orange | – | −0.01 | 0.03 | ||||||||

| G5 | 49.8 | 23.77376 | 90.60069 | 12.2 | Orange | 6.6 | 0.12* | 0.05 | −38.06 | 1 | −6.01 | 0.1 | ||||

| C5 | 52.2 | 23.78955 | 90.61113 | 31.4 | Orange | 2.9 | 0.17* | 0.18 | −32.44 | 1 | −5.11 | 0.1 | ||||

| CW14 | 53.3 | 23.76468 | 90.60143 | 12.8 | Orange | 0.5 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | −34.02 | 0.05 | −5.45 | 0.02 | ||

| CW16 | 53.3 | 23.76574 | 90.59781 | 13.4 | Orange | – | 0.10 | 0.04 | ||||||||

| CW8 | 55.5 | 23.77374 | 90.59457 | 11.6 | Orange | – | 0.08 | 0.03 | ||||||||

| CW11 | 56.1 | 23.77347 | 90.64032 | 21.3 | Brownish-grey | – | 2.17 | 0.16 | ||||||||

| CW29 | 56.4 | 23.76932 | 90.62417 | 14.0 | Orange | 0.4 | 0.15 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.03 | −28.89 | 0.06 | −4.82 | 0.02 | ||

| F5 | 57.9 | 23.77364 | 90.60453 | 15.2 | Orange | 1.0 | 0.05* | 0.05 | −39.78 | 1 | −5.95 | 0.1 | ||||

| CW31 | 57.9 | 23.76812 | 90.62185 | 14.0 | Yellowish-grey | 0.3 | 0.10 | 0.03 | −0.03 | 0.02 | −28.95 | 0.01 | −4.78 | 0.00 | ||

| DI4 | 57.9 | 23.77100 | 90.60941 | 7.6 | Orange | 0.6 | 0.05ˆ | 0.02 | −27.65 | 1 | −4.68 | 0.1 | ||||

| CW6 | 58.5 | 23.78060 | 90.64434 | 7.9 | Orange | – | 0.10 | 0.03 | ||||||||

| CW20 | 58.5 | 23.77768 | 90.60592 | 3.0 | Orange | – | 0.12 | 0.03 | ||||||||

| CW35 | 59.1 | 23.80112 | 90.63520 | 21.3 | Orange | – | 0.08 | 0.02 | ||||||||

| CW32 | 59.4 | 23.76968 | 90.62048 | 25.6 | Orange | – | 0.16 | 0.05 | ||||||||

| CW50 | 59.4 | 23.77364 | 90.60453 | no data | Orange | – | 0.01 | 0.04 | ||||||||

| CW3 | 59.7 | 23.78013 | 90.64050 | 3.7 | Orange | – | −0.03 | 0.03 | ||||||||

| M1.5 | 60.5 | 23.77612 | 90.63238 | 14.0 | Orange | 2.2 | 2.04 | 0.06 | −20.05 | 0.09 | −3.16 | 0.01 | ||||

| CW10 | 61.0 | 23.79000 | 90.63612 | 12.2 | Orange | – | 0.11 | 0.03 | ||||||||

| CW21 | 61.0 | 23.77928 | 90.60805 | 10.4 | Orange | – | 0.12 | 0.04 | ||||||||

| CW30 | 61.0 | 23.76525 | 90.61650 | 21.3 | Orange | – | 0.04 | 0.04 | ||||||||

| CW15 | 62.5 | 23.75635 | 90.61013 | 24.4 | Orange | 0.1 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.11 | 0.05 | −0.01 | 0.03 | −36.34 | 0.09 | −5.51 | 0.03 |

| CW13 | 62.8 | 23.75499 | 90.61245 | 11.6 | Orange | – | 0.06 | 0.03 | −32.51 | 1 | −5.21 | 0.1 | ||||

| CW19 | 62.8 | 23.77703 | 90.59895 | 18.9 | Orange | – | 0.12 | 0.02 | ||||||||

| CW17 | 63.4 | 23.77158 | 90.59070 | 12.2 | Orange | – | 0.15 | 0.05 | −40.51 | 1 | −5.95 | 0.1 | ||||

| CW18 | 64.0 | 23.77413 | 90.59233 | 9.8 | Orange | 9.4 | 0.06 | 0.02 | −0.02 | 0.03 | 0.08 | 0.04 | −31.95 | 0.04 | −5.20 | 0.03 |

| CW22 | 64.0 | 23.78395 | 90.61327 | 14.6 | Orange | 0.0 | 2.67 | 0.06 | −21.27 | 0.03 | −3.77 | 0.02 | ||||

| CW4 | 65.2 | 23.78108 | 90.63325 | 15.8 | Brownish-grey | 29.1 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.02 | −32.13 | 0.05 | −5.15 | 0.01 | ||

| CW25 | 70.1 | 23.77623 | 90.61705 | 3.7 | Yellowish-grey | 16.9 | 0.27 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.04 | −24.52 | 0.11 | −4.35 | 0.03 | ||

| CW33 | 70.1 | 23.78758 | 90.62680 | no data | Orange | – | 0.17 | 0.04 | ||||||||

| CW38 | 78.0 | 23.76919 | 90.58512 | no data | Orange | – | 0.14 | 0.03 | ||||||||

| A8 | 81.5 | 23.78534 | 90.60322 | 15.2 | Orange | 1.0 | 0.10* | n/a | ||||||||

| CW12 | 87.2 | 23.77612 | 90.63238 | 21.3 | Grey | 0.4 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.03 | −21.35 | 0.04 | −3.67 | 0.03 | ||

| B CW2 | 88.5 | 23.78036 | 90.63856 | 7.3 | Grey | 11.0 | 0.05 | 0.09 | −26.11 | 1 | −3.13 | 0.1 | ||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||

| CW34 | 103.6 | 23.79025 | 90.63115 | 28.0 | Orange | – | 0.17 | 0.04 | ||||||||

| CW41 | 121.9 | 23.79158 | 90.65763 | 31.7 | Orange | – | 0.23 | 0.05 | −35.95 | 1 | −5.62 | 0.1 | ||||

| CW7 | 123.1 | 23.78822 | 90.65173 | 23.2 | Orange | – | 0.17 | 0.04 | ||||||||

| CW46 | 128.0 | 23.79188 | 90.61815 | 12.2 | Orange | 1.3 | −0.01 | 0.03 | −26.95 | 0.03 | −4.58 | 0.02 | ||||

| CW42 | 128.0 | 23.79463 | 90.65992 | 18.3 | Orange | 0.2 | 0.05 | 0.03 | −37.60 | 0.08 | −5.99 | 0.02 | ||||

| CW45 | 129.5 | 23.78267 | 90.64853 | 12.2 | Orange | 3.6 | 0.10 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.02 | −32.75 | 0.24 | −5.35 | 0.05 | ||

| CW47 | 137.2 | 23.79475 | 90.65147 | 18.3 | Orange | 1.8 | −0.06 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.02 | −36.47 | 0.13 | −5.85 | 0.01 | ||

| CW5 | 141.4 | 23.77305 | 90.63365 | 2.4 | Orange | – | 0.11 | 0.03 | ||||||||

| CW36 | 149.4 | 23.79062 | 90.62635 | 6.7 | Orange | 1.0 | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.04 | −31.17 | 0.07 | −5.11 | 0.02 | ||

| CW44 | 152.4 | 23.78500 | 90.64982 | 21.3 | Orange | 6.7 | 0.06 | 0.02 | −33.76 | 0.12 | −5.50 | 0.02 | ||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||

| WAB24030 | 205.4 | 23.75098 | 90.63160 | no data | Orange | 8.7 | 0.03 | 0.03 | −32.26 | 0.04 | −5.26 | 0.03 | ||||

| WAB24529 | 219.5 | 23.78147 | 90.63872 | no data | Orange | 0.7 | 0.04 | 0.04 | −30.26 | 0.00 | −5.02 | 0.00 | ||||

| WAB24509 | 222.5 | 23.76812 | 90.58532 | no data | Orange | 0.3 | 0.00 | 0.03 | −33.70 | 0.01 | −5.43 | 0.01 | ||||

| WAB24522 | 225.6 | 23.79296 | 90.64467 | no data | Orange | 0.4 | 0.01 | 0.03 | −34.51 | 0.08 | −5.56 | 0.02 | ||||

| WAB24531 | 231.6 | 23.77832 | 90.64477 | no data | Whitish-gray | 0.6 | 0.04 | 0.03 | −24.34 | 0.05 | −4.25 | 0.01 | ||||

| WAB24501 | 231.6 | 23.78110 | 90.64968 | no data | Orange | 0.9 | 0.01 | 0.04 | −31.75 | 0.02 | −5.20 | 0.00 | ||||

| WAB24527 | 231.6 | 23.78598 | 90.65933 | no data | Orange | 1.4 | −0.01 | 0.03 | −33.49 | 0.06 | −5.44 | 0.00 | ||||

| WAB24538 | 232.3 | 23.78538 | 90.65800 | no data | Whitish-grey | 1.4 | 0.04 | 0.03 | −34.29 | 0.09 | −5.57 | 0.01 | ||||

| WAB24511 | 234.7 | 23.78545 | 90.62695 | no data | Orange | 1.6 | 0.04 | 0.03 | −30.58 | 0.05 | −5.06 | 0.02 | ||||

| WAB24504 | 234.7 | 23.79211 | 90.65718 | no data | Orange | 1.6 | 0.00 | 0.04 | −36.97 | 0.07 | −5.93 | 0.02 | ||||

| WAB24528 | 234.7 | 23.78707 | 90.65923 | no data | Whitish-grey | 1.7 | 0.07 | 0.04 | −33.87 | 0.01 | −5.49 | 0.00 | ||||

| WAB24513 | 237.7 | 23.79385 | 90.65831 | no data | Whitish-grey | 1.8 | 0.04 | 0.04 | −37.80 | 0.03 | −6.02 | 0.01 | ||||

| WAB24502 | 237.7 | 23.79117 | 90.66017 | no data | Whitish-grey | 1.8 | 0.06 | 0.03 | −37.29 | 0.03 | −5.90 | 0.01 | ||||

Cummulative thickness of silt and clay layers above well filter, excluding the top soil

Sampled for 3H in 2003 (*) or 2008 (ˆ)

“ – ” indicates no measurement was performed; n/a = not available

Extensive well sampling in 2010 and 2011 was performed mostly from community wells used for drinking, including 18 community wells (CW) and 13 Water Aid Bangladesh (WAB) wells. CWs were installed at depths 35–152 m bgl by Dhaka University in 2001–2004 [van Geen et al., 2007] to provide access to As-safe water in the most severely affected villages within the study area. Some CWs were sampled twice for 14CDIC (2010 and 2011) and two or three times for 3H (2006, 2010, 2011); all measured values are reported. WAB wells, installed later in 2010 by the NGO Water Aid Bangladesh over a broader area, are deeper (>200 m bgl) and cluster towards the eastern end of the study area. A set of 8 monitoring wells installed in the intermediate depth range (35–88 m bgl) was also extensively sampled, including M1.5 (2011), DI4 (2008), and the deepest wells from multi-level well nests A–G (2003). Well DI4 was sampled before the in situ study of As sorption on low-As aquifer sediments reported by Radloff et al. [2011], whereas some results of the sampling of wells A–G were also previously reported [Zheng et al., 2005; Stute et al., 2007; Dhar et al., 2008; Mailloux et al., 2013]. All well screens were made of slotted PVC and ranged in length from 6.1 m (20 ft) at WAB wells to 3.0 m (10 ft) at CWs and 0.9–1.5 m (3–5 ft) at all other locations.

2.2. Well purging and field measurements

Well sampling was conducted using a submersible pump producing a flow rate of 5–10 L/min (Typhoon 12-V standard pump, Groundwater Essentials), or by utilizing a hand pump when a submersible pump could not be used due to well construction, i.e. for all WAB wells, with the exception of no. 24030. Tritium sampling of community wells in 2006 was also conducted using the existing hand pump in order to avoid contamination. Three borehole volumes were purged out of a well before sample collection. Electrical conductivity (EC), temperature (T), and pH were monitored by probes in a flow-through portable chamber (MP 556, YSI, Inc.) during purging with a submersible pump and stabilized before sampling. Alkalinity was also measured in the field using standard Gran titrations [Gran, 1952]. Electrodes (EC and pH) were calibrated on site before collecting the first sample of the day, and the flow cell was taken off the line before sample collection to prevent cross-contamination between wells. For WAB wells sampled by hand pumps, EC and pH were measured in an overflowing bucket, which may have introduced a systematic error in pH due to degasing of CO2 from the splashing water. For these wells, pH was calculated (denoted by # in Table S1) from the field-measured alkalinity values (not affected by CO2 degassing) and the total DIC measured at the Woods Hole NOSAMS facility. DIC samples for radiocarbon measurements were collected into glass bottles directly from the hand pump, without splashing, and immediately capped.

2.3. Groundwater sampling and elemental analysis by ICP-MS and IC

Samples for major cation (Na, K, Mg, Ca), Si, P, and trace element (As, Fe, Mn) analysis were collected without filtration into 25 mL HDPE scintillation vials with conical polyseal caps (Wheaton, Fisher Scientific) and later acidified to 1% HCl (Optima, Fisher Scientific). Previous work demonstrated that the well screens in Bangladesh typically provide sufficient filtration without introducing artifacts associated with syringe filtration, such as the removal of Fe and PO4 by rapid ferrihydrite precipitation [Zheng et al., 2004], and that delayed acidification in the lab does not affect the results [van Geen et al., 2007]. The samples were analyzed for Na, K, Mg, Ca, Si, P, As, Fe, and Mn by high-resolution inductively coupled plasma–mass spectrometry (HR ICP-MS) on a single-collector VG Axiom [Cheng et al., 2004] to a precision of ±10% or better. Accuracy of the results was checked against an internal laboratory reference standard and also found to be within <10% of the expected values.

Unacidified samples for anion analyses were collected in parallel with cation and trace element samples. The samples were maintained refrigerated until analysis except for the duration of travel from Bangladesh to USA. The concentrations of Cl, F, Br, and SO4 were determined on a Dionex ICS-2000 ion–chromatograph (IC) with an IonPac AS18 analytical column and an AG18 guard column (Thermo Scientific) using a self-regenerating KOH eluent. A standard was run after every 8–10 samples to ensure accuracy of the measurements, and several samples were analyzed in duplicates or triplicates to confirm analytical precision (typically <5% for Cl, <10% for SO4, and 5–15% for Br and F).

2.4. Sampling and analysis of stable isotopes in water (H218O/H216O and H2H16O/H216O ratios)

Stable isotope samples were collected in 60 mL glass bottles with polyseal lined caps. Measurements of samples collected in 2003 (wells A-G), 2004 (several CWs), and 2008 (DI4) were performed at the Environmental Isotope Laboratory of the University of Waterloo with a precision of ±0.1‰ (H218O/H216O ratio expressed as δ18O) and ±1‰ (H2H16O/H216O ratios expressed as δ2H). Stable isotope measurements on samples collected in 2010 and 2011 (CWs, WABs, and M1.5) were performed on a cavity ringdown (CRD) laser spectrometer at Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory (L2130-i Isotopic H2O, Picarro, Santa Clara, CA) with a precision better than 0.05‰ (δ18O) and 0.25‰ (δ2H). All values are reported in the δ-notation as ‰ deviation from Vienna Standard Mean Ocean Water (VSMOW).

2.5. Sampling and analysis of 3H and noble gases (He, Ne, Ar, Kr, Xe, and 3He/4He)

Groundwater recharged after the onset of surface testing of nuclear weapons can be detected by the presence of elevated tritium (3H), a radioactive isotope of hydrogen released during the tests that began in 1950s and peaked in the early 1960s [e.g., Weiss et al., 1979; Weiss and Roether, 1980], provided that adequate detection limit of 3H is achieved [Eastoe et al., 2012]. Samples for 3H were collected in 125 mL glass bottles with polyseal caps and analyzed at Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory’s Noble Gas Laboratory using the 3He ingrowth technique [Clarke et al., 1976; Bayer et al., 1989; Ludin et al., 1998]. The detection limit of the 3H analyses was 0.05–0.10 TU (1 TU corresponds to a 3H/1H ratio of 10−18), with a precision of ±0.02–0.16 TU (Table 1). Noble gas samples were collected in copper tubes (~1 cm outer diameter) that contain ~19 cm3 of groundwater. Concentrations of He, Ne, Ar, Kr, and Xe isotopes were measured by mass spectrometry [Stute et al., 1995] with typical analytical precisions of ±2% for He and 3He/4He, and ±1% for Ne, Ar, Kr, and Xe. The system was calibrated with atmospheric air standards and water samples equilibrated with atmospheric air at known temperature and pressure.

The measured concentrations of noble gases (He, Ne, As, Kr, and Xe; Table 3) were processed through a sequence of inverse numerical models to estimate the temperature of each groundwater sample at the time of recharge based on the known equilibrium solubilities of noble gases in water [Aeschbach-Hertig et al., 1999; Peeters et al., 2003]. Besides fitting the equilibrium temperature, the models also account for gases in excess of the atmospheric equilibrium concentrations due to trapped bubbles, commonly referred to as “excess air”. The excess air component is either fitted without any fractionation from the atmospheric air (assuming complete dissolution of the bubbles) or with various processes and degrees of fractionation. A constant salinity of 0 and atmospheric pressure of 1013 mbars were assumed for the model calculations. After the best fit was found for observed Ne, Ar, Xe, and Kr concentrations, the predicted He concentration was calculated according to the same model [Aeschbach-Hertig et al., 1999; Peeters et al., 2003]. Any 4He in excess of that amount was reported as “excess He” and is considered a radiogenic input from the radioactive decay processes, hence it can also be named “radiogenic He”. If the input of radiogenic He comes primarily from the aquifer sediments, it can be proportional to the age or residence time of groundwater under the following assumptions: (1) the aquifer matrix and release rates of He from the sediment are fairly homogeneous and constant along the flowpaths; (2) little degasing loss occurs; and (3) no confounding effects of deep crustal He degassing occur [Torgersen and Clarke, 1985].

Table 3.

Noble gas concentrations and the resulting model recharge temperatures and He surplus (radiogenic He) concentrationsa

| Well ID | Depth (m) | He ccSTP g−1GW | Ne ccSTP g−1GW | Ar ccSTP g−1GW | Kr ccSTP g−1GW | Xe ccSTP g−1GW | 3He/4He | Model prob. (%)b | Model T (°C) | err Model T (°C) | He surplusc ccSTP g−1GW | He surp.ccSTP g−1GW |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E5 | 36.2 | 4.00E-08 | 1.29E-07 | 2.40E-04 | 5.51E-08 | 7.73E-09 | 1.27E-06 | 0 | ||||

| A7 | 40.7 | 7.96E-08 | 2.12E-07 | 3.22E-04 | 6.92E-08 | 9.17E-09 | 9.09E-07 | 98.4 | 22.26 | 0.65 | 2.71E-08 | 1.72E-09 |

| CW27 (2010) | 45.7 | 5.46E-08 | 2.20E-07 | 3.17E-04 | 6.65E-08 | 8.29E-09 | 2.75E-06 | 54.9 | 31.95 | 3.44 | −1.55E-09 | 1.51E-09 |

| CW27 (2011, 1) | 45.7 | 5.54E-08 | 2.25E-07 | 3.20E-04 | 6.76E-08 | 8.75E-09 | 3.07E-06 | 73.4 | 24.33 | 0.68 | −9.22E-10 | 1.31E-09 |

| CW27 (2011, 2) | 45.7 | 5.46E-08 | 2.24E-07 | 3.20E-04 | 6.77E-08 | 8.73E-09 | 3.18E-06 | 59.7 | 24.40 | 0.71 | −1.47E-09 | 1.29E-09 |

| CW23 | 45.7 | 5.60E-08 | 2.33E-07 | 3.35E-04 | 7.09E-08 | 8.92E-09 | 1.54E-06 | 16.0 | 25.34 | 1.34 | −2.04E-09 | 1.28E-09 |

| G5 | 49.8 | 5.35E-08 | 1.47E-07 | 2.42E-04 | 5.41E-08 | 7.32E-09 | 1.03E-06 | 0 | ||||

| CW14 | 53.3 | 5.19E-08 | 1.74E-07 | 2.65E-04 | 5.94E-08 | 8.06E-09 | 1.25E-06 | 0 | ||||

| CW29 | 56.4 | 7.25E-08 | 1.96E-07 | 2.97E-04 | 6.40E-08 | 8.41E-09 | 9.31E-07 | 78.2 | 24.77 | 0.66 | 2.37E-08 | 1.58E-09 |

| CW31 | 57.9 | 7.40E-08 | 1.96E-07 | 3.00E-04 | 6.42E-08 | 8.49E-09 | 9.05E-07 | 70.0 | 24.65 | 0.75 | 2.51E-08 | 1.59E-09 |

| CW15 (2010) | 62.5 | 5.01E-08 | 1.03E-07 | 1.64E-04 | 3.78E-08 | 5.56E-09 | 8.15E-07 | 0 | ||||

| CW15 (2011, 1) | 62.5 | 4.71E-08 | 9.88E-08 | 1.63E-04 | 3.72E-08 | 5.48E-09 | 8.76E-07 | 0 | ||||

| CW15 (2011, 2) | 62.5 | 4.77E-08 | 9.73E-08 | 1.59E-04 | 3.73E-08 | 5.52E-09 | 8.38E-07 | 0 | ||||

| CW18 (2010) | 64.0 | 5.49E-08 | 1.72E-07 | 2.80E-04 | 6.07E-08 | 8.00E-09 | 1.07E-06 | 0.1 | ||||

| CW18 (2011) | 64.0 | 5.28E-08 | 1.82E-07 | 2.88E-04 | 6.32E-08 | 8.45E-09 | N/Ad | 82.1 | 24.15 | 0.50 | 7.98E-09 | 1.35E-09 |

| CW22 | 64.0 | 5.71E-08 | 2.22E-07 | 3.21E-04 | 6.71E-08 | 8.58E-09 | 1.69E-06 | 82.1 | 25.88 | 1.04 | 1.33E-09 | 1.30E-09 |

| CW4 | 65.2 | 4.77E-08 | 1.84E-07 | 2.93E-04 | 6.41E-08 | 8.21E-09 | 1.15E-06 | 1.7 | 25.51 | 7.87 | 1.58E-09 | 1.72E-09 |

| CW25 | 70.1 | 5.68E-08 | 2.13E-07 | 3.17E-04 | 6.78E-08 | 9.15E-09 | 1.51E-06 | 36.0 | 22.03 | 0.50 | 3.48E-09 | 1.46E-09 |

| CW12 (2010) | 87.2 | 5.16E-08 | 2.09E-07 | 3.06E-04 | 6.54E-08 | 8.22E-09 | 1.09E-06 | 20.0 | 30.92 | 2.74 | −1.47E-09 | 1.38E-09 |

| CW12 (2011, 1) | 87.2 | 5.32E-08 | 2.05E-07 | 3.03E-04 | 6.53E-08 | 8.64E-09 | 1.27E-06 | 95.1 | 23.74 | 0.52 | 1.76E-09 | 1.38E-09 |

| CW12 (2011, 2) | 87.2 | 5.34E-08 | 2.09E-07 | 3.05E-04 | 6.54E-08 | 8.74E-09 | 1.42E-06 | 48.9 | 23.55 | 0.51 | 1.02E-09 | 1.42E-09 |

|

| ||||||||||||

| CW46 | 128.0 | 8.45E-08 | 2.24E-07 | 3.26E-04 | 6.94E-08 | 8.83E-09 | 8.77E-07 | 18.7 | 24.66 | 0.98 | 2.85E-08 | 1.80E-09 |

| CW42 | 128.0 | 7.40E-08 | 2.12E-07 | 3.17E-04 | 6.81E-08 | 9.39E-09 | 1.09E-06 | 3.4 | 21.22 | 0.48 | 2.17E-08 | 1.78E-09 |

| CW45 | 129.5 | 8.02E-08 | 2.26E-07 | 3.27E-04 | 6.97E-08 | 8.73E-09 | 9.42E-07 | 25.2 | 31.42 | 2.56 | 2.28E-08 | 1.87E-09 |

| CW47 | 137.2 | 7.34E-08 | 2.16E-07 | 3.23E-04 | 6.87E-08 | 8.90E-09 | 1.02E-06 | 75.0 | 24.16 | 1.04 | 1.97E-08 | 1.58E-09 |

| CW36 (2010) | 149.4 | 7.84E-08 | 2.26E-07 | 3.28E-04 | 7.02E-08 | 8.71E-09 | 9.70E-07 | 8.9 | 30.83 | 2.88 | 2.12E-08 | 1.86E-09 |

| CW36 (2011) | 149.4 | 7.69E-08 | 2.27E-07 | 3.25E-04 | 6.95E-08 | 9.42E-09 | 1.04E-06 | 13.7 | 21.32 | 0.49 | 2.02E-08 | 1.86E-09 |

| CW44 | 152.4 | 8.05E-08 | 2.26E-07 | 3.21E-05 | 6.90E-08 | 8.62E-09 | 8.91E-07 | 0 | ||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| WAB24030 | 205.4 | 8.03E-08 | 2.28E-07 | 3.28E-04 | 7.02E-08 | 8.97E-09 | 9.52E-07 | 15.0 | 23.59 | 0.74 | 2.34E-08 | 1.74E-09 |

Grey shading indicates samples that were not used for plots and discussion due to: low model probability and/or model T error >1.5 °C

The model used is described in section 2.3.3.

The probability that model is consistent with the data (>1% is minimum, >5% is a strong criterion)

He surplus is equivalent to radiogenic He

3He/4He ratio measurement not available

The model output also included a χ2 probability that the model is consistent with the data. Low χ2 probabilities are considered a reasonable criterion to reject the models, with <1% often used and <5% being a very strong criterion to reject the run. Errors of the modeled temperature and excess He were estimated by a numerical propagation of the experimental uncertainties through the inverse procedure with data sets generated by Monte Carlo simulations [Aeschbach-Hertig et al., 1999; Peeters et al., 2003].

2.6. Sampling and analysis of 14C/12C and 13C/12C in DIC and DOC

Samples for radiocarbon (14C/12C) and carbon stable isotopic (13C/12C) measurements on dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) and dissolved organic carbon (DOC) were collected in 125 mL or larger glass bottles with polyseal caps and immediately “poisoned” with 0.1 mL of saturated mercuric chloride solution. All carbon isotopic measurements were performed at the National Ocean Science Accelerator Mass-Spectrometer (NOSAMS) facility at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution following standard protocols [Elder et al., 1997]. Ratios of 13C/12C are reported as δ13CVPDB in ‰ deviations from the Vienna Pee Dee Belemnite standard, with a typical error of ±0.1‰. Radiocarbon data (14CDIC and 14CDOC) are reported as fraction modern (FM), “modern” being defined as 95% of the AD 1950 radiocarbon concentration of NBS (National Bureau of Standards) Oxalic Acid I normalized to δ13CVPDB of −19‰ [Olsson, 1970]. FM values were normalized for C isotopic fractionation to a value of δ13CVPDB = − 25‰. Errors in FM measurements are shown in Table 2 and range from 0.0012 to 0.0041 FM. Concentrations of DIC and DOC were also reported by NOSAMS for the samples collected in 2010 and 2011 (±2% precision), including some CWs and most WAB wells. For the remaining samples, DIC concentration was calculated from alkalinity and pH values measured in the field (in a flow cell). Where both are available, DIC concentrations calculated from the field data and those reported by NOSAMS are typically in agreement within <10%.

Table 2.

Radiocarbon and 13C data, with calculated 14C agesa

| Well ID | Depth (m) | As (μg/L) | Phase | FM 14Cb | ± σ (FM) | δ13C | UC 14C age | C1 14C age | C2 14C age | Δ14C | Accession # |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A7 | 40.7 | 0.0 | DIC | 0.2843 | n/a | −19.0 | 10,400 | 9,530 | 7,260 | −721.0 | n/a |

| CW27 (2010) | 45.7 | 0.0 | DIC | 1.1216 | 0.0040 | −18.3 | Modernc | Modern | Modern | 113.5 | OS-80269 |

| CW27 (2011) | ║ | n/ap | DIC | 1.1165 | 0.0036 | −18.3 | Modern | Modern | Modern | 108.3 | OS-87014 |

| CW23 | 45.7 | 0.1 | DIC | 1.0792 | 0.0029 | −17.6 | Modern | Modern | Modern | 71.4 | OS-80003 |

| G5 | 49.8 | 6.6 | DIC | 0.6266 | n/a | −21.6 | 3,860 | 2,990 | 1,790 | −369.5 | n/a |

| C5 | 52.3 | 2.9 | DIC | 0.2631 | n/a | −17.6 | 11,040 | 10,170 | 7,250 | −735.2 | n/a |

| CW14 | 53.3 | 0.5 | DIC | 0.7419 | 0.0024 | −18.6 | 2,470 | 1,600 | Modern | −263.5 | OS-87015 |

| CW29 | 56.4 | 0.4 | DIC | 0.3841 | 0.0022 | −21.7 | 7,910 | 7,040 | 5,880 | −618.7 | OS-80000 |

| F5 | 57.9 | 1.0 | DIC | 0.4600 | 0.0020 | −25.9 | 6,430 | 5,560 | 5,860 | −542.5 | OS-41275 |

| F5 | ║ | n/ap | DOC | 0.5010 | 0.0030 | n/a | 5,710 | n/ap | n/ap | −502.0 | n/a |

| CW31 | 57.9 | 0.3 | DIC | 0.3238 | 0.0014 | −20.8 | 9,320 | 8,450 | 6,910 | −678.6 | OS-80004 |

| DI4 | 57.9 | 0.6 | DIC | 0.8259 | 0.0031 | −17.8 | 1,580 | 710 | Modern | −179.9 | OS-68866 |

| M1.5 | 60.5 | 2.2 | DIC | 0.9312 | 0.0030 | −16.6 | 590 | Modern | Modern | −75.6 | OS-90066 |

| M1.5 | ║ | n/ap | DOC | 0.8259 | 0.0021 | −24.9 | 1,580 | n/ap | n/ap | −180.3 | OS-101857 |

| CW15 (2010) | 62.5 | 0.1 | DIC | 0.5064 | 0.0017 | −19.9 | 5,620 | 4,750 | 2,850 | −497.3 | OS-80002 |

| CW15 (2011) | ║ | n/ap | DIC | 0.5027 | 0.0028 | −19.8 | 5,690 | 4,810 | 2,880 | −501.0 | OS-87016 |

| CW18 (2010) | 64.0 | 9.4 | DIC | 0.5692 | 0.0023 | −19.0 | 4,660 | 3,790 | 1,540 | −434.9 | OS-79994 |

| CW18 (2011) | ║ | n/ap | DIC | 0.6628 | 0.0025 | −18.4 | 3,400 | 2,530 | Modern | −342.1 | OS-87124 |

| CW18 (2010) | ║ | n/ap | DOC | 0.4436 | 0.0020 | −26.5 | 6,720 | n/ap | n/ap | −559.6 | OS-80285 |

| CW22 | 64.0 | 0.0 | DIC | 1.0374 | 0.0030 | −18.5 | Modern | Modern | Modern | 29.9 | OS-79996 |

| CW4 | 65.2 | 29.1 | DIC | 0.7429 | 0.0023 | −21.9 | 2,460 | 1,590 | 490 | −262.4 | OS-79992 |

| CW4 | ║ | n/ap | DOC | 0.7521 | 0.0041 | −24.3 | 2,360 | n/ap | n/ap | −253.3 | OS-80290 |

| CW25 | 70.1 | 16.9 | DIC | 0.8199 | 0.0025 | −15.7 | 1,640 | 770 | Modern | −186.1 | OS-87122 |

| A8 | 81.5 | 1.0 | DIC | 0.2842 | n/a | −19.1 | 10,400 | 9,530 | 7,290 | −721.0 | n/a |

| CW12 (2010) | 87.2 | 0.4 | DIC | 0.8992 | 0.0029 | −16.3 | 880 | Modern | Modern | −107.3 | OS-80268 |

| CW12 (2011) | ║ | n/ap | DIC | 0.9096 | 0.0029 | −16.3 | 780 | Modern | Modern | −97.0 | OS-87013 |

| CW12 (2011) | ║ | n/ap | DOC | 0.7373 | 0.0022 | n/a | 2,520 | n/ap | n/ap | −268.1 | OS-86918 |

| B CW2 | 88.5 | 11.0 | DIC | 0.8940 | n/a | −19.2 | 930 | 60 | Modern | −100.4 | n/a |

|

| |||||||||||

| CW46 | 128.0 | 1.3 | DIC | 0.2578 | 0.0013 | −16.8 | 11,210 | 10,340 | 7,050 | −744.1 | OS-79995 |

| CW42 | 128.0 | 0.2 | DIC | 0.2965 | 0.0017 | −20.9 | 10,050 | 9,180 | 7,710 | −705.7 | OS-87052 |

| CW45 | 129.5 | 3.6 | DIC | 0.2526 | 0.0016 | −18.0 | 11,370 | 10,500 | 7,760 | −749.2 | OS-79998 |

| CW47 | 137.2 | 1.8 | DIC | 0.2872 | 0.0012 | −20.7 | 10,310 | 9,440 | 7,870 | −714.9 | OS-79855 |

| CW36 (2010) | 149.4 | 1.0 | DIC | 0.2809 | 0.0013 | −17.5 | 10,500 | 9,630 | 6,680 | −721.2 | OS-79997 |

| CW36 (2011) | ║ | n/ap | DIC | 0.2636 | 0.0014 | −17.8 | 11,020 | 10,150 | 7,320 | −738.4 | OS-87123 |

| CW44 | 152.4 | 6.7 | DIC | 0.2600 | 0.0012 | −18.5 | 11,140 | 10,260 | 7,780 | −741.9 | OS-79856 |

|

| |||||||||||

| WAB24030 | 205.4 | 8.7 | DIC | 0.2856 | 0.0016 | −15.7 | 10,360 | 9,490 | 5,660 | −716.4 | OS-79999 |

| WAB24529 | 219.5 | 0.7 | DIC | 0.2540 | 0.0018 | −16.1 | 11,330 | 10,460 | 6,800 | −747.8 | OS-87239 |

| WAB24509 | 222.5 | 0.3 | DIC | 0.3106 | 0.0022 | −20.4 | 9,670 | 8,790 | 7,120 | −691.7 | OS-87236 |

| WAB24522 | 225.6 | 0.4 | DIC | 0.2757 | 0.0017 | −19.2 | 10,650 | 9,780 | 7,580 | −726.4 | OS-87248 |

| WAB24531 | 231.7 | 0.6 | DIC | 0.2307 | 0.0013 | −13.4 | 12,120 | 11,250 | 6,100 | −771.0 | OS-87238 |

| WAB24501 | 231.7 | 0.9 | DIC | 0.2558 | 0.0014 | −17.2 | 11,270 | 10,400 | 7,320 | −746.1 | OS-87252 |

| WAB24527 | 231.7 | 1.4 | DIC | 0.2737 | 0.0018 | −19.7 | 10,710 | 9,840 | 7,870 | −728.3 | OS-87240 |

| WAB24538 | 232.3 | 1.4 | DIC | 0.2804 | 0.0020 | −19.9 | 10,510 | 9,640 | 7,760 | −721.6 | OS-87245 |

| WAB24511 | 234.7 | 1.6 | DIC | 0.2660 | 0.0013 | −17.4 | 10,950 | 10,080 | 7,090 | −736.0 | OS-87237 |

| WAB24504 | 234.7 | 1.6 | DIC | 0.2889 | 0.0014 | −19.8 | 10,260 | 9,390 | 7,470 | −713.2 | OS-87254 |

| WAB24528 | 234.7 | 1.7 | DIC | 0.2698 | 0.0015 | −19.4 | 10,830 | 9,960 | 7,850 | −732.2 | OS-87246 |

| WAB24513 | 237.7 | 1.8 | DIC | 0.2916 | 0.0018 | −21.1 | 10,190 | 9,320 | 7,890 | −710.5 | OS-87258 |

| WAB24502 | 237.7 | 1.8 | DIC | 0.3007 | 0.0017 | −20.6 | 9,930 | 9,060 | 7,470 | −701.5 | OS-87253 |

14C ages were calculated as described in section 3.2. C1 and C2 ages are not applicable to DOC (“-”)

FM stands for fraction modern radiocarbon

Age is reported as “Modern” when FM≥1 or the age correction resulted in a negative age

║ = same depth as above; n/ap = not applicable ; n/a = not available

2.7. Lithologs

Drill cuttings were collected at 2–5 ft (0.6–1.5 m) intervals from 49 of the 52 wells ≤152 m deep (i.e. all except deep WAB community wells) and were used to calculate the total clay+silt thickness above the well screen (Table 1). The thicknesses of all clay and silt layers encountered in the litholog were added, except for the ground surface clay/soil, as this layer does not play a role in separating the high-As shallow aquifers from the low-As shallow aquifers. We use a depth of 90 m (300 ft) to distinguish shallow private wells installed within a day by a handful of drillers using the manual hand percussion (or “hand-flapper”) method from intermediate wells in the 90–150 m depth range which require a larger team working for several days using a manual rotary drilling-direct circulation method with a double-acting (“donkey”) pump [Ali, 2003; Horneman et al., 2004]. Lithologs for the wells <90 m deep (i.e. the shallow low-As wells) are more reliable in terms of recording the presence of clay layers than lithologs collected with the donkey pump, which are more likely to miss clay layers. Sand color at the depth of filter intake was noted for each well, regardless of the installation depth.

3. Results

3.1. Tritium (3H), radiocarbon (14C), and arsenic

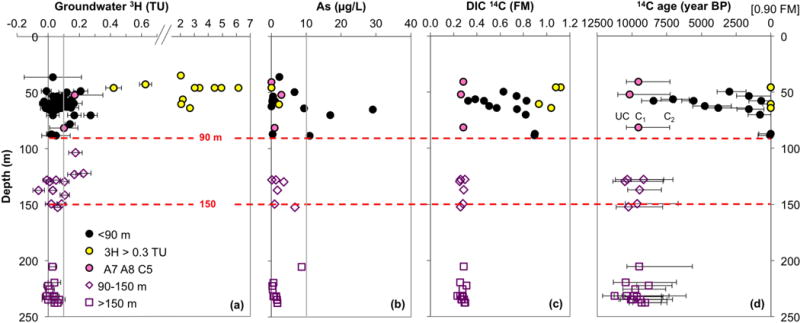

With the exception of three wells that contain 10–29 μg/L As (Fig. 3b) and tap the shallow aquifer (<90 m bgl), all community wells met the WHO guideline for As of 10 μg/L at the time of sampling despite many years of use [van Geen et al., 2007]. Of the 65 wells sampled for 3H, 8 had elevated 3H concentration greater than 0.3 TU, indicating a significant contribution of groundwater recharged within the past 60 years (Fig. 3a and Table 1). All 8 of these wells were screened at depths ≤65 m bgl and contained <3 μg/L As, where measured. Another set of 23 wells contained low 3H concentrations (0.10–0.27 TU) at least at one time of sampling, 21 of which were detectable at the 95% confidence level (0 TU was not within the range of 2σ, twice the analytical error). Most (16) of the 21 wells containing low-level, detectable 3H clustered in the shallow aquifer, whereas only 5 such samples were found in the intermediate aquifer (90–150 m bgl) and none at depths >150 m bgl. The number of samples with detectable 3H paired to concurrent samples with valid noble gas measurements was limited to 3 wells in the shallow aquifer, thus 3H/3He ages were not calculated. Results from the wells sampled two or three times between 2006–2011 (Table 1) showed no temporal trends in 3H concentrations over this time period.

Figure 3.

Profiles of groundwater (a) 3H with analytical error, (b) dissolved As, (c) 14C in DIC, and (d) 14C ages plotted against sample depth. All 3H measurements, including several repeat measurements, are shown; for samples where 14C was measured twice, 14CDIC and calculated ages plotted in this figure, and hereafter, are based on the 14C values obtained in 2010. The grey line in (a) indicates 0.1 TU, the concentration above which all 3H samples (except for two with a large analytical error) are conclusively detectable, whereas the grey line in (b) denotes the current World Health Organization limit of 10 μg/L As in safe drinking water. The symbols in (d) show C1 14C age, a simple open system model that corrects for the initial 14CDIC at recharge of 0.90 FM. The error bars indicate “UC” (uncorrected) 14C age as the maximum age, calculated directly from the measured 14C values without any correction, and C2 14C age as the minimum age, which contains an additional correction for the maximum contribution of radiocarbon-dead carbonate dissolution along the flowpath. In this figure, and hereafter, the pink fill in black circles indicates the shallow depth samples (A7, A8, and C5) with consistent deeper groundwater properties across various geochemical and age parameters, whereas the yellow fill in black circles denotes shallow aquifer groundwater with particularly elevated 3H concentrations (>0.3 TU).

Radiocarbon concentrations in dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) range from 0.26 to 1.12 FM in groundwater from shallow depth <90 m bgl (Fig. 3c and Table 2). Deeper than 90 m, a uniform radiocarbon signature of 0.25–0.31 FM is observed in intermediate and deep aquifer DIC. Within the shallow aquifer, some 14CDIC values fall within the range of those observed in intermediate and deep aquifer groundwater, but only 3 of these samples have a consistent intermediate/deep aquifer signature across various parameters measured in this study (A7, A8, and C5, labeled by pink fill in Fig. 3 and thereafter). These samples come from a shallow outcrop of the confined Pleistocene aquifer in the northwest of our study area [van Geen et al., 2003]. On the other end of the spectrum, samples from 4 wells with the highest 14CDIC (0.93–1.12 FM) also have 3H >2 TU (Fig. 3c), confirming that groundwater recharged since the nuclear weapon testing began in the late 1940s reached these shallower wells, carrying the so-called “bomb” 14C and 3H with it. The remaining shallow aquifer samples (below ~0.9 FM 14CDIC) contain a lower range of 3H concentrations (<0.3 TU).

3.2. Radiocarbon dating

3.2.1. 14C age corrections

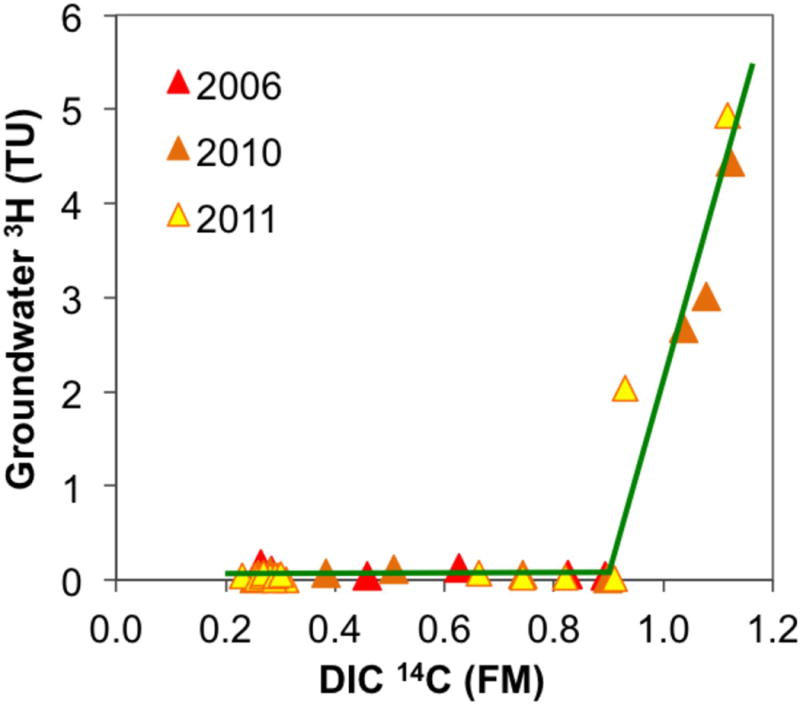

Three groundwater age estimates were determined for each sample on the basis of radiocarbon data (Fig. 3d and Table 2). The 14C half-life of 5730 yr (the “Cambridge half-life”) was used to generate the maximum radiocarbon age, denoted as the uncorrected 14C age (“UC 14C age”). This age assumes the initial 14C concentration of DIC or DOC at recharge to be 1 FM and assumes an evolution of DIC without any carbon reservoir corrections:

| (1) |

This approach might be appropriate for particulate organic material, but the initial 14CDIC is rarely 1 FM, as total DIC is formed by the dissolution of soil CO2 and resident soil carbonates in an open system before the system closes off from the contact with vadose zone carbon sources [Fontes and Garnier, 1979]. Whereas the soil CO2 is a product of oxidation of plant remains, the 14C activity of which is often close to that of atmospheric CO2, soil carbonates usually have a lower 14C activity. One way to estimate the initial 14C activity of DIC is to empirically relate 14CDIC to observed 3H concentrations (Fig. 4), following Verhagen et al. [1974]. This approach yielded an estimate of initial 14CDIC of 0.90 FM for our data set, close to the value of 0.87 FM used by Hoque and Burgess [2012] in their Bengal Basin 14C work and also close to the fixed value of 0.85 FM applied in the “Vogel” model [Vogel and Ehhalt, 1963; Vogel, 1967]. Therefore, the corrected radiocarbon age, or the “C1 14C age”, is adjusted for the initial 14CDIC formed under open system conditions, but not for any subsequent dissolution of carbonates along the flowpath:

| (2) |

Figure 4.

Empirical relationship between groundwater 3H and 14C in DIC plotted for all available samples from the shallow, low-As aquifer (<90 m bgl) with concurrently measured groundwater 3H and 14C in DIC. The initial 14CDIC was determined to be 0.90 FM and used to correct for the vadose zone processes before the recharge closed off from the atmosphere in C1 and C2 14C age calculations.

Finally, the minimum 14C age was calculated from the C1 14C age by estimating the maximum possible contribution of carbonate dissolution along the flowpath to the total DIC and its final 14C concentration, after the system was closed with respect to gas exchange in the vadose zone. This was achieved by using a simple isotopic mixing model based on the δ13C of two end members: the initial DIC and carbonate minerals [Hoque and Burgess, 2012]. In order to make this the maximum possible correction for carbonate dissolution, the value used for the initial δ13CDIC was −25‰, in accordance with the values in Harvey et al. [2002] and Hoque and Burgess [2012], and appropriate for the dominance of 13C-depleted C3 plants [Sarkar et al., 2009]. Similarly, to make this a minimum age, the carbonate minerals in the mixture were assumed to be of marine origin (δ13C = 0‰) and free of radiocarbon. Thus, the minimum radiocarbon age – C2 14C age – includes a correction for mixing of different carbon pools, similar to that of Ingerson and Pearson [1964], but with an added correction for initial 14CDIC of 0.90 FM:

| (3) |

None of the above 14C age corrections account for isotopic fractionation effects during the isotopic exchange reactions of C species (CO2(g) to CO32−(aq) equilibrium), which can have some impact on the final 13C contents [Fontes and Garnier, 1979]. The above models also do not take into account the mineralization of groundwater DOC subsequent to the initial recharge, and the impact it might have on the budget of DIC radiocarbon. Lastly, the 14C ages were not calibrated to calendar years, as doing so would not be meaningful for dating of groundwater 14CDIC that is subject to as many uncertainties as presented above.

3.2.2. Calculated DIC 14C ages

The shallow aquifer groundwater spans a wide range of DIC 14C ages, calculated by all three methods, from modern in the high-3H samples to 7–11 kyr in samples A7, A8, and C5 that resemble the deep aquifer (Fig. 3d and Table 2). In contrast, DIC 14C ages of the intermediate and deep aquifer groundwater are greater and less variable when calculated by a single method, but as seen with the older samples in the shallow aquifer, variation of ages from 6 to 12 kyr exists between different methods of age calculation. The variability among different age calculation methods, and between samples from the shallow aquifer and pooled intermediate and deep aquifer samples, can visualized by the box plots (Fig. S2) that provide minimum, 1st quartile, median, 3rd quartile, and maximum values of the sample group. The 14C age corrected for the initial DIC 14C content of 0.90 FM (C1 age), based on the empirical relationship between 3H and 14C, places the age of intermediate and deep groundwater samples within the 9–11 kyr range, with an average of 9,800 14C yr before present (BP). The maximum, uncorrected (UC) age would result in these samples being ~900 yr older on average (10,700 14C yr BP), whereas the additional correction for dissolution of carbonates along the flowpaths (C2 age) would make them younger by ~2–3 kyr (average 7,300 14C yr BP). The corrections from UC to C1 and C2 14C ages had a similar effect on the shallow aquifer groundwater ages, thus shrinking their overall range and shifting the results towards younger ages with each correction.

3.3. Noble gas temperatures and radiogenic He

The model that best fits the noble gas data (Table 3) considers the equilibrium temperature, the amount of excess air, and the fractionation of excess air as variables in the simulation (“Taf-1” model). The fractionation of excess air is conceptualized as a partial equilibrium dissolution of the trapped air bubbles in a closed system, or the “CE” model [Aeschbach-Hertig et al., 1999; Peeters et al., 2003]. Some of the model results were rejected (Table 3) based on a low model probability and/or a high error in model temperature estimate (>1.5 °C error). At least some of the samples for which the model failed to converge suffered from degassing during sampling, as indicated by Ne concentrations below solubility equilibrium with the soil air (<1.7×10−7 ccSTP g−1). Among the converged samples accepted for further analysis (16 out of 29 samples), model probabilities were well above the strict 5% threshold, except for CW42 with 3.4%, which still produced a reasonable fit (>1 %) and had the lowest model temperature error of the entire data set, thus the fit for this sample was accepted.

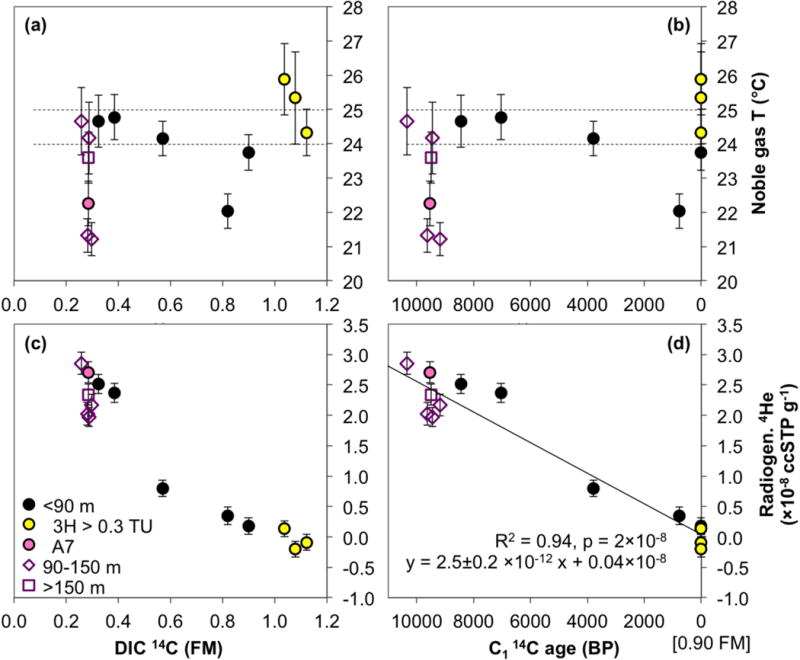

Current groundwater temperatures in the shallow low-As aquifer (Table S1) cluster around an average of 26.2 °C ± 0.3 °C (standard deviation), whereas the average temperatures in intermediate and deep groundwater are slightly higher at 26.7 ± 0.3 °C and 27.0 ± 0.4 °C, respectively. Temperatures calculated by the noble gas model (Table 3), also known as the noble gas temperatures (NGTs), represent groundwater temperatures at the time of recharge at the water table. In the shallow aquifer, NGTs vary between 22.0 and 25.9 °C (Fig. 5ab), with nine of the eleven converging samples clustering between 23.6 and 25.9 °C. Excluding the two outliers with NGTs close to 22 °C, average NGT of the shallow low-As samples is 24.5 °C (± 0.7 °C st. dev.), with the 95% confidence interval between 24.0 and 25.0 °C. The two outliers lie outside the 95% confidence interval by more than double the model error of those samples, and one of them (sample A7 from 40.7 m depth) consistently exhibits the signature of deep aquifer tracers and chemistry. The shallow low-As aquifer 95% confidence interval of NGTs, nevertheless, lies below the temperatures currently measured in this aquifer, as well as below the available temperature measurements made by pressure transducers in very shallow, high-As wells in the study area (25.4 to 26.8 °C range, data not shown).

Figure 5.

Noble gas temperatures and radiogenic (“excess”) He plotted against 14C measured in DIC (a and c), and corrected C1 14C ages (b and d). Noble gas temperatures, corresponding to temperatures at the time of recharge, and radiogenic He were estimated by Taf-1 model fit to the measured noble gas data. Only the samples where model converged are plotted. The errors indicated by vertical error bars combine the analytical error with model fit uncertainty. Only one sample per well is shown; where multiple noble gas measurements were made, those with the best noble gas model fit are displayed. Dashed lines in (a) and (b) mark the 95% confidence interval of the average noble gas temperatures of shallow samples, excluding the two outliers at approximately 22 °C. The trend linking radiogenic He to C1 14C ages was calculated for combined shallow, intermediate, and deep groundwater samples.

Intermediate and deep aquifer NGTs, pooled together, range from 21.2 to 24.7 °C with the average of 23.0 °C (± 1.6 °C st. dev.). The two lowest NGTs from this group are below any NGT observed in the shallow aquifer, and the 95% confidence interval of 21.5 to 24.4 °C is both wider and lower in absolute values relative to that of the shallow samples. There is no temporal trend in recharge temperatures, as NGTs plotted against the C114C age (Fig. 5b) do not have a statistically significant trend (p = 0.19).

The excess or radiogenic He, also estimated by the NG model, increases from ~0 to ~3×10−8 ccSTP g−1 in samples with 14CDIC ranging from modern to ~0.25 FM, with the highest concentrations present in samples from the intermediate and deep aquifers and those with a low 14CDIC from the shallow aquifer (Fig. 5c). The relationship between the radiogenic He and the C1 14C age (Fig. 5d) is linear, and corresponds to an empirical He accumulation rate of 4He = 2.5±0.2×10−12 ccSTPg−1yr−1 • 14C age (yr) +/− 0.04×10−8 ccSTPg−1 (R2 = 0.94, p = 2×10−8, samples from all depths were included in the regression). As a quality control, 3He/4He ratio was also measured. In samples that contain a high concentration of radiogenic He (up to ~35% of the measured He), 3He/4He ratio ranges between 0.9–1.1×10−6 (Table 3). The 3He/4He ratio in these samples falls below that of the remaining samples and below the ratio found in solubility equilibrium with atmospheric air (1.36×10−6) because of the low 3He/4He ratio of radiogenic crustal He (~2×10−8).

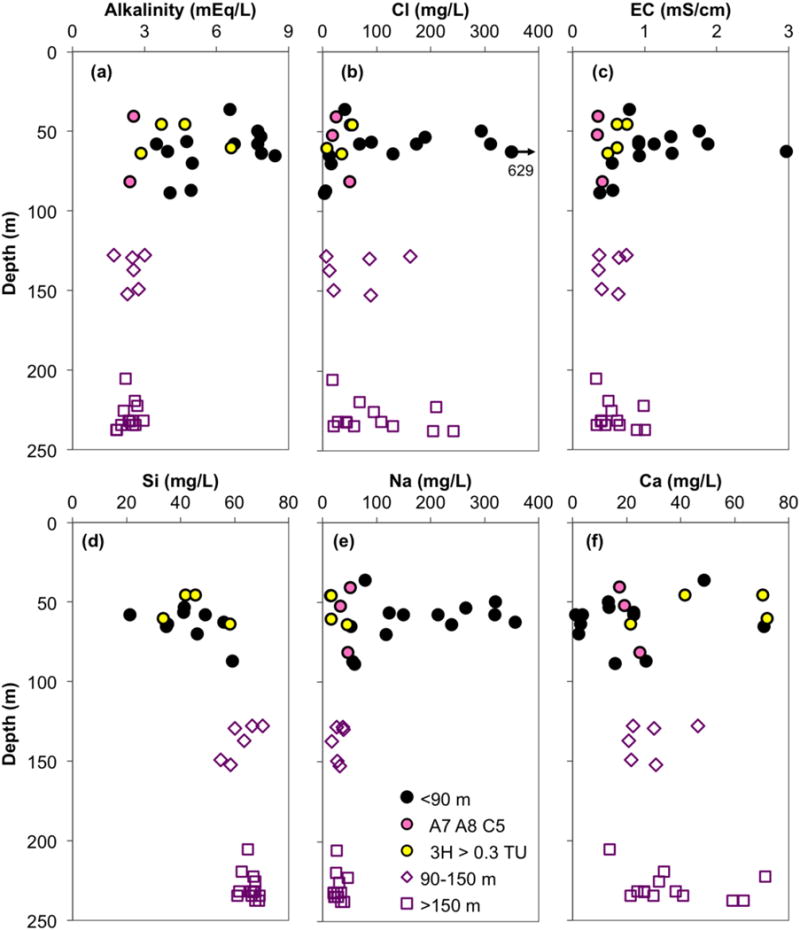

3.4. Chemical composition of groundwater

The great variability of 3H and 14C in the shallow aquifer compared to the intermediate and deep aquifers is matched by an even greater scatter in the shallow groundwater geochemical characteristics, such as pH, electrical conductivity (EC), alkalinity, DIC, Na, and Si concentrations (Fig. 6 and Table S1). In contrast, intermediate and deep aquifer groundwaters carry a more uniform signature of these parameters. In particular, deeper groundwater and the three shallow samples with deep 3H and 14C signatures cluster around lower values of pH (6.5–6.8), EC (0.3–1 mS/cm), alkalinity (1.7–3.0 mEq/L), DIC (3–4.8 mM), and Na (<50 mg/L) relative to most of the shallow aquifer samples, whereas Si concentrations are higher (55–70 mg/L). The concentrations of the remaining major cations (Ca, Mg, and K) and anions (Cl, SO4) are variable and similar between the three aquifers (Fig. 6 and Table S1). One sample from the shallow aquifer (CW15) is particularly high in salinity/EC, with Cl and SO4 concentrations of 629 and 24 mg/L, respectively.

Figure 6.

Profiles of groundwater (a) alkalinity, (b) chloride, (c) electrical conductivity, (d) silicon, (e) sodium, and (f) calcium plotted against the sample depth.

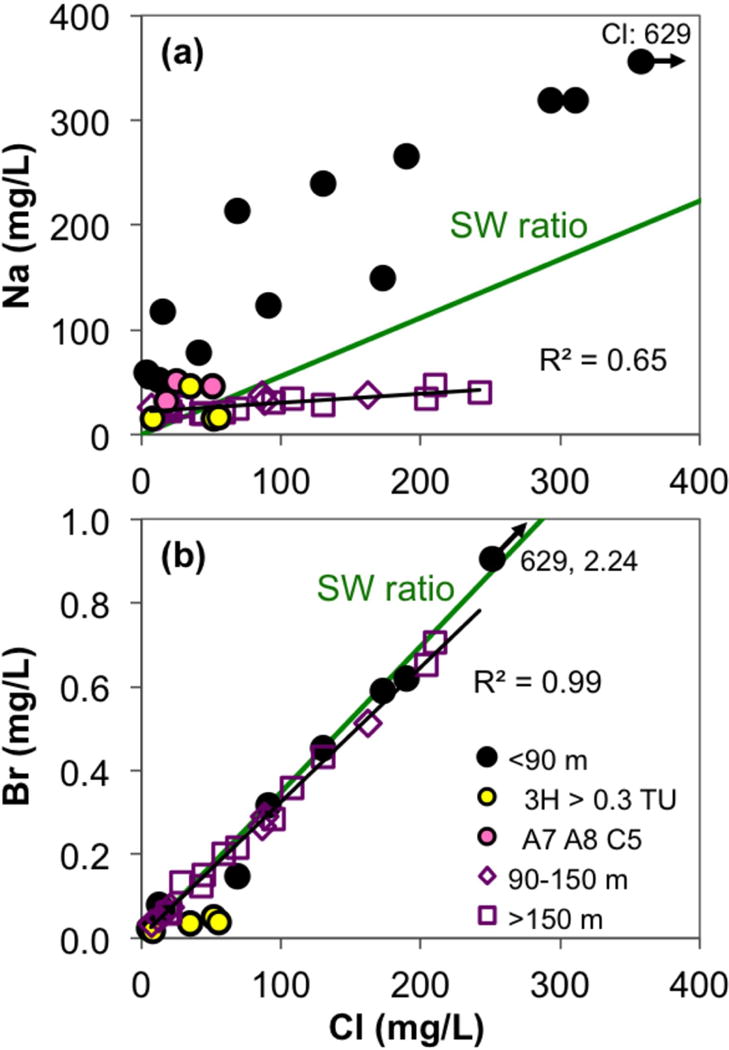

Among the minor groundwater constituents, bromide concentrations remain ≤0.7 mg/L, where detectable (Fig. 9b). Fluoride concentrations are mostly <1 mg/L (Table S1), with intermediate and deep aquifer samples largely <0.4 mg/L. Two samples from the shallow aquifer (2–3 mg/L F) do exceed the WHO guideline of 1.5 mg/L. Fortunately, only one of these high-F wells (CW18) is a drinking water source. Likewise, phosphate is generally below 0.6 mg/L P, except for one sample at 4.7 mg/L (Table S1). Finally, iron and manganese are highly variable in all three aquifers, with concentrations of up to 4 mg/L Fe (mostly <2 mg/L, but one sample has ~10 mg/L) and up to 1,400 μg/L Mn.

Figure 9.

The correlations of (a) sodium and (b) bromide to chloride. Green lines indicate the trendlines with seawater Na/Cl and Br/Cl ratios. Black lines are the trendlines for pooled intermediate (90–150 m bgl) and deep aquifer (>150 m bgl) groundwater samples. The high Cl sample in (a) actually falls on the seawater line.

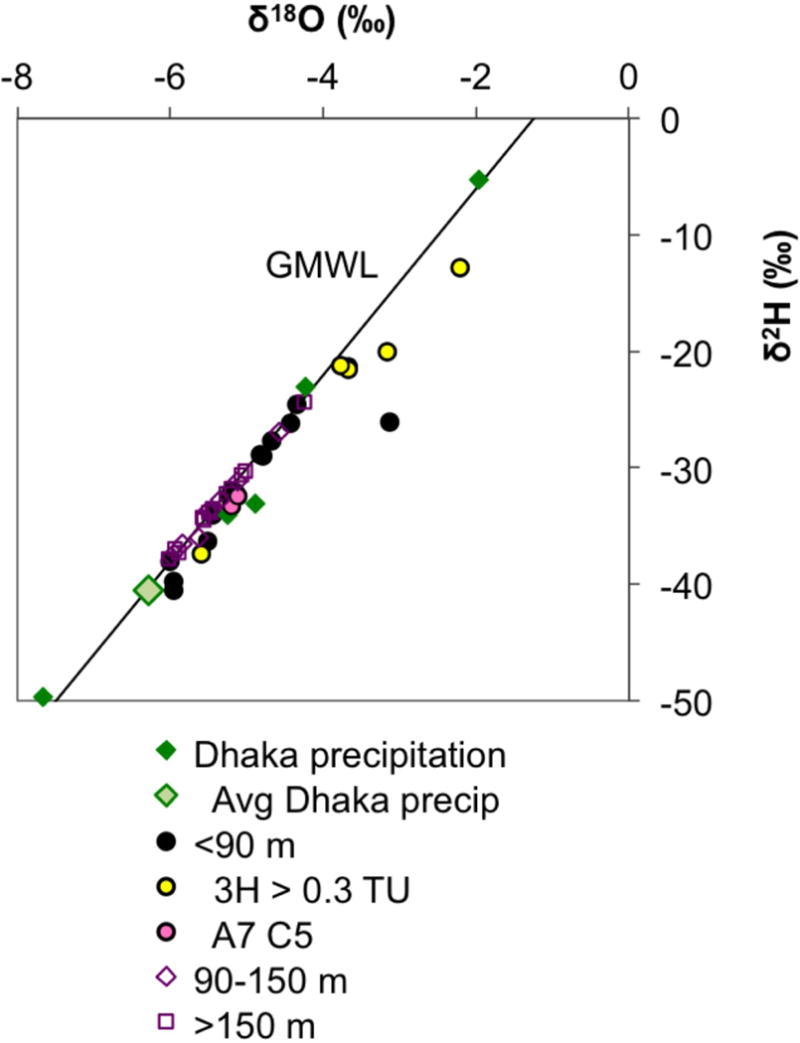

3.5. Environmental stable isotopes: 2H/1H and 18O/16O in water and 13C/12C in DIC

Most water stable isotope values (expressed as δ2H and δ18O) fall on or near the global meteoric water line (GMWL: δ2H = 8 • δ18O + 10‰), but many also plot to the right of this line as a result of evaporation and kinetic isotope fractionation (Fig. 7, Table 1). Virtually all intermediate and deep aquifer samples fall on the GMWL, indicating recharge by precipitation, and cluster around δ18O values between −5 and −6‰ and δ2H values between −30 and −40‰. The average isotope composition of modern precipitation in the area is similar to that observed in the intermediate and deep aquifer samples [Stute et al., 2007]. In contrast, stable isotopes of water in the shallow aquifer span a larger range of values, with nearly half of the samples impacted by some degree of evaporation before recharge, as judged by their distance from the GMWL. Several of the most evaporated samples were recharged in the last 60 years, as evidenced by their high 3H concentrations (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

Water stable isotopic (δ2H and δ18O) composition of groundwater and its relationship to the global meteoric water line (GMWL) of Craig [1961]. For comparison, Dhaka precipitation and its average [Stute et al., 2007] are also displayed. Note that the high-3H samples (yellow fill) plot mostly to the right of the GMWL.

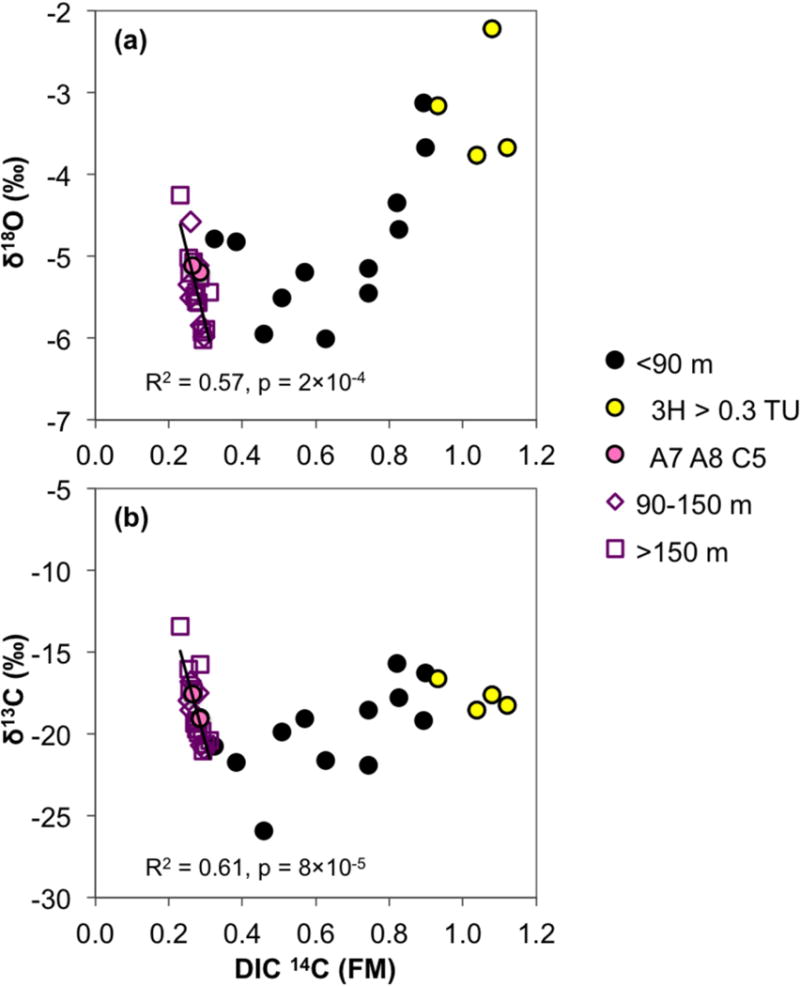

Carbon stable isotope values (δ13C) in DIC range between −15 and −22‰ in all three aquifers (Fig. 8, Table 2). The δ13CDIC values observed here fall in between those expected of oxidized OC from C3 plants (−28‰) and C4 plants (−13‰) in the Bengal Basin [Sarkar et al., 2009], under the assumption that the DIC was produced solely by the oxidation of bulk OC. Carbon isotopic fractionation process between dissolved CO2 produced from OC in equilibrium with bicarbonate/carbonate ions can also account for some of the spread in observed δ13CDIC values, as δ13C is 9–10‰ higher in carbonate ions [Fontes & Garnier, 1979].

Figure 8.

The relationship of (a) water δ18O and (b) DIC δ13C with 14C in DIC. The trendlines, R2 and p values for pooled intermediate (90–150 m bgl) and deep aquifer (>150 m bgl) samples are indicated. A similar pattern to (a) is also observed for δ2H (not shown, R2 = 0.60 and p = 1×10−4).

A striking aspect of the stable isotopic data from intermediate and deep groundwater is the strong correlation of δ13CDIC with both δ2H and δ18O (R2 = 0.81 for both isotopes, δ2H vs. δ13CDIC shown in Fig. S1). Furthermore, all three stable isotopes are systematically correlated with 14C in DIC of the intermediate and deep aquifer groundwater (Fig. 8; δ2H not shown as it follows an identical pattern to that of δ18O). As 14C FM increases, there is a consistent and statistically significant trend towards more negative values of all stable isotopes. The three shallow samples with characteristics of deeper groundwater also fit within the intermediate and deep aquifer trend.

In the shallow aquifer, however, an opposite trend from that in the deeper aquifers is noted: higher (more positive) values of δ13CDIC, δ18O, and δ2H are observed as 14CDIC increases toward modern values (Fig. 8). The trends are less sharply defined than for the deeper aquifers. In addition, the correlation of δ18O (and δ2H) data with 14CDIC must be exaggerated in part by the evaporated nature of the most recently recharged samples with the highest 14C content. The correlations between stable isotopes of the shallow aquifer are likewise less defined than in the deeper aquifers (δ2H vs. δ13CDIC shown in Fig. S1).

4. Discussion

4.1. Penetration of recent recharge into the low-As aquifers

A considerable amount of recharge has occurred within the past 60 years in low-As portion of the shallow aquifer (<90 m bgl), as evidenced by detectable 3H in 24 out of 42 sampled wells (57%). A subset of 8 wells (19% of the total) has particularly large contributions of bomb 3H (>0.3 TU), as well as bomb 14C (~1 FM), where both were measured (Tables 1 and 2). Variable 3H concentrations were expected in the shallow aquifer in Araihazar given that even the high-As shallow aquifer (<20 m bgl) contains mixtures of older groundwater with post-bomb recharge [Stute et al., 2007]. Much of this recent recharge, as well as some of the older shallow aquifer groundwater, comes from a pool of surface water characterized by evaporative enrichment of stable isotopes (Fig. 7), such as stagnant ponds or rice fields that can hold flood water for months at a time [Stute et al., 2007]. In contrast, the intermediate (90–150 m bgl) and deep aquifer (>150 m bgl) groundwater was sourced directly from precipitation, and there is very little penetration of recent recharge to this depth. The presence of low, detectable 3H concentrations (0.10–0.23 TU) in low-As portions of the intermediate aquifer (90–150 m bgl) does suggest a limited contribution of recent recharge at these depths. Using a conservative (low) value of 2–3 TU as a 100% benchmark, as any undiluted recharge since 1980 would now contain ~2–3 TU in the area, the maximum proportion of such a contribution can be 3–11%, and appears insufficient to alter isotopic composition of DIC in the intermediate aquifer. The highly variable 3H and 14CDIC content of the shallow aquifer groundwater is matched by equally variable groundwater chemical properties (Figs. 3 and 6). In contrast, groundwater chemistry of the intermediate and deep aquifer is fairly uniform with consistently low EC, low alkalinity, low Na, high Si, and a Na/Cl ratio below that of the seawater (Figs. 6 and 9a).

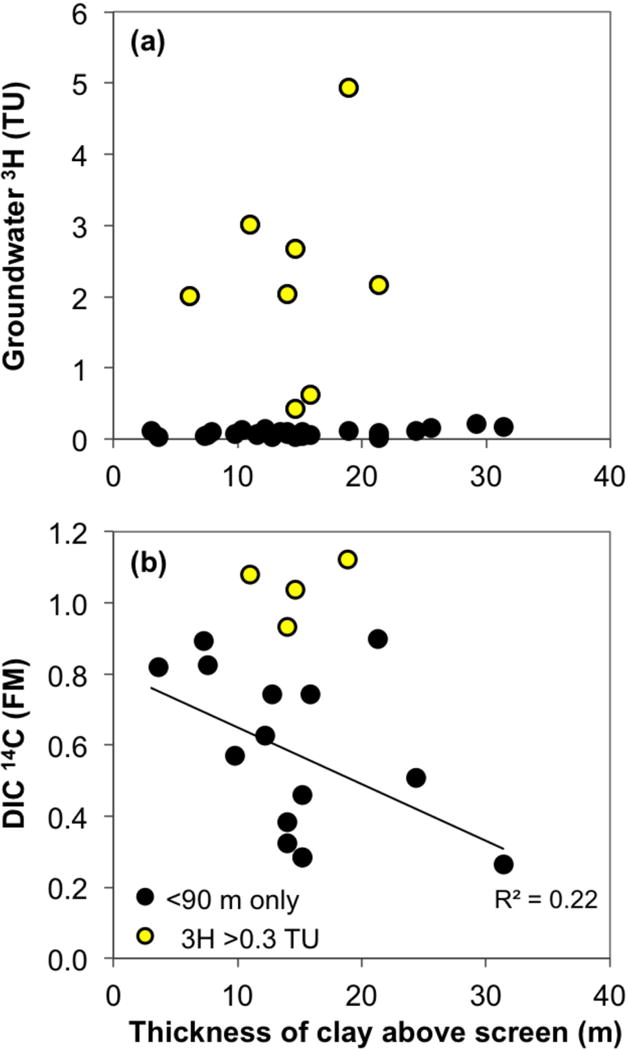

The concentrations of 3H and 14CDIC in groundwater provide a measure of vertical flow, not necessarily local flow, connecting the shallow aquifer to the surface and high-As aquifer. Whether the clay units are continuous and provide confinement could be important for the long-term fate of shallow low-As aquifers but difficult to ascertain. In an attempt to do so, we compared 3H and 14CDIC concentrations to the thickness of overlying clay layers derived from the lithologs (Table 1). This is a simple parameter that presumably reflects the extent of vertical confinement of the aquifer. Overlying clay thickness turns out not to correlate well with either 3H or 14CDIC concentrations in shallow low-As groundwater (Fig. 10). Where clay above the well screen is thicker than 20 m, measured 3H values appear lower, but 4 of the 8 samples still contain detectable 3H (0.1–0.2 TU) and thus receive some recent recharge from the surface. When samples containing 3H concentrations >0.3 TU are excluded (yellow fill in Fig. 10), removing the locations with unusually rapid penetration of bomb 14C from consideration, a weak negative correlation is revealed between the 14CDIC and the clay thickness (Fig. 10b), but this presumed longer-term trend is not statistically significant (p = 0.075). The lack of spatial correlations with local confining units is consistent with recent recharge arriving to the sampled locations via lateral flow and with the flow in the aquifer being mostly horizontal [Aziz et al., 2008]. The observed vertical communication of the shallow aquifer with the surface and high-As groundwater may occur in spatially limited areas of higher hydraulic conductivity where clay layers are thin or missing [McArthur et al., 2010; Shamsudduha et al., 2015], and could be driven by local pumping that increases downward and lateral hydraulic gradients.

Figure 10.

The relationship between groundwater (a) 3H and (b) 14C vs. the total thickness of clay in lithologs of the shallow low-As wells. For samples where multiple measurements were made, the latest non-negative values of 3H are shown in (a) and the 14C values from 2010 are displayed in (b). The high 3H samples (>0.3 TU, yellow fill) were excluded from the 14C trendline with clay thickness shown in (b).

Notably, some samples from the shallow aquifer (A7, A8, C5) appear unaffected by recent recharge, as they have the deeper aquifer signature of low 14C, high radiogenic He, low Na and low alkalinity (Figs. 3, 5, and 6). These wells are located in the NW corner of the study area, close to the southern edge of the uneroded Pleistocene uplands, known as the Madhupur Terrace [Goodbred and Kuehl, 2000b]. The protection of this part of the aquifer afforded by the interfluvial Madhupur paleosol might explain the Pleistocene signature of groundwater found there [McArthur et al., 2008], and the thickest clay layer among the reported lithologs is also found at well C5. This is an example of the area where local stratigraphy clearly limits groundwater flow between aquifers.

Another possible indicator of exchange between the surface and low-As aquifers might be the Cl/Br ratios in groundwater [McArthur et al., 2012]. Three samples from the shallow low-As aquifer stand out with a Cl/Br ratio higher than that of the seawater (yellow fill in Fig. 9b). Besides having an additional source of Cl, these samples have the highest measured 3H concentrations and also contain excess SO4 compared to the marine salt SO4/Cl ratio (not shown), suggesting mixing with surface-derived wastewater. However, Cl/Br ratios of most samples are close to that of SW, indicating that all three low-As aquifers are largely unpolluted by wastewater [Ravenscroft et al., 2013]. Instead, Cl and Br are ultimately sourced from the ocean, via atmospheric aerosol inputs or via a low degree of mixing with remnant seawater from past coastline transgressions.

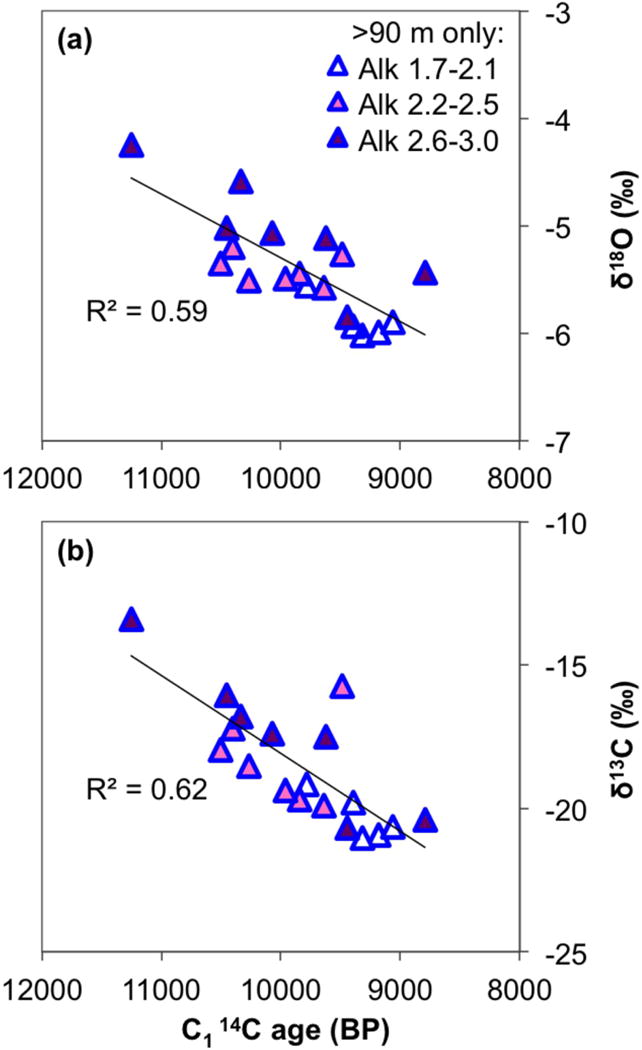

4.2. Groundwater residence time from radiocarbon ages

While mixing of groundwater with different ages can confound radiocarbon ages in the shallow aquifer, which vary from modern to ~10 kyr BP, 14C ages in the intermediate and deep aquifers cluster at approximately 10 kyr BP. Given that the range of calculated residence times put the plausible date of intermediate and deep aquifer recharge to the onset of the Holocene, an issue worth considering is whether the ages need correction for dissolution of carbonates along the flowpath. The reported UC and C1 14C ages of ~10–12 kyr BP do not include such a correction. The C2 14C ages, however, include the additional correction for carbonate dissolution based on the observed 13C/12C ratios in DIC. This correction shifts estimated ages towards the mid-Holocene by 2–3 kyr, which could be significant in the context of changing climate conditions at the time of deeper aquifer recharge.

The relatively low pH, EC, and alkalinity (Table S1 and Fig. 6), as well as the molar ratio of Si to alkalinity of ~1 in the intermediate and deep aquifers (Fig. S1), suggest the predominance of silicate weathering in these aquifers, as do the weak, but significant, correlations of Ca and Mg with Si (not shown, p < 0.04 for both). In contrast, although Ca and Mg are the dominant cations at ~60–70 % of cation equivalence units in intermediate and deep groundwater (Fig. S1), their concentrations are negatively correlated with alkalinity and 13CDIC (Mg not shown; p < 0.04 for all correlations). This is the opposite of what would be expected from the dissolution of Ca or Mg-bearing carbonates in the system. Instead, the sum of Ca and Mg is well correlated with Cl (Fig. S1). Chloride dominates the anion composition when Cl/alkalinity molar ratio is >1, i.e. in ~1/2 of the intermediate and deep samples, and is not related to carbonate chemistry.

The amount of acid-soluble carbonates found in either Holocene or the orange, Pleistocene sand in our field area is near or below the limit of quantification on Shimadzu carbon analyzer (0.01–0.02 weight %) [Mihajlov, 2014]. The Pleistocene sands are also typically low in Ca content [McArthur et al., 2008; van Geen et al., 2013; Mihajlov, 2014], presumably due to the more efficient aquifer flushing under the higher hydraulic gradients of the Pleistocene sea level lowstand [BGS/DPHE, 2001]. The Ca+Mg cation dominance and correlation with Cl in intermediate and deep groundwater (Fig. S1) might instead be related to the low Na concentrations and the low Na/Cl ratio through a cation exchange mechanism that depletes Na and enriches Ca and Mg in groundwater. This could occur during an episode of salinization of an aquifer previously well-flushed by freshwater [Ravenscroft and McArthur, 2004], such as at the onset of the Holocene. Rapid sea-level rise at the time could have caused a minor saltwater intrusion, limited in extent because intermediate and deep groundwater stable isotope ratios and Cl concentrations are not exceptionally high.

It follows from the above discussion that the dissolution of carbonates contributing older, 13C-enriched DIC to groundwater may not be a correct explanation for the mutual correlations of lower 14CDIC with a more positive δ13CDIC and higher alkalinity in the intermediate and deep aquifers (Figs. 8 and S1). When a third dimension is added to the plot of δ13C vs. 14C age in DIC (Fig. 11b), it is clear that the high alkalinity samples are dispersed throughout the trend and not focused at more positive δ13C values and older samples. Since these aquifers are dominated by silicate weathering, which does not add radiocarbon-free DIC to the system, 13C correction for the 14C age of DIC, as performed in the C2 age calculation, appears unnecessary. The open system model (C1 14C age) where the initial 14C activity of DIC is empirically corrected to 0.9 FM appears sufficient to describe radiocarbon ages of the intermediate and deep groundwater and dates these samples to ~9–11,000 years BP (Table 2 and Fig. 3).

Figure 11.

Plots of (a) δ18O and (b) δ13CDIC against the C1 14C age in intermediate and deep groundwater only (samples from >90 m bgl), with an added third dimension of alkalinity. The units of alkalinity concentrations shown in the legend are mEq/L, and the three concentration ranges were selected based on the spread of data values. The overall trendlines for pooled intermediate and deep samples and their R2 values are displayed.

As a limitation to the reported radiocarbon ages, the influence of dissolved and particulate organic matter (DOC and POC) mineralization on the observed 14CDIC after groundwater was recharged and the system closed off from the vadose zone carbon inputs was not accounted for by the age calculations. In the intermediate and deep aquifers, younger DOC from the surface is unlikely to have been metabolized, as a very small proportion (3–10 %) of younger groundwater from the organic matter-rich Holocene aquifer penetrates to the intermediate depth and transport of reactive DOC has been shown to be a slow process [Mailloux et al., 2013]. Also, the DOC sampled in the shallow low-As aquifer is ~2 orders of magnitude lower in concentration than DIC (Table S1) and generally has the same or slightly older 14C age than DIC (Table 2).

A possibility remains, however, that the consumption of resident DOC and POC from the Pleistocene (and older) sediments, coupled to reductive processes such as Fe, Mn, and SO4 reduction or methanogenesis [Harvey et al., 2002], affects the 14C content of DIC in addition to aging. Aging probably still dominates within our study area, however, given the systematic increase in radiogenic He with 14C ages (Fig. 5d). In addition, methanogenesis is unlikely to have played a major role in DIC genesis within our samples, as their DIC does not bear the characteristically enriched 13C signature expected of the methanogenetic environments [Aravena et al., 1995; Harvey et al., 2002].

4.3. Radiogenic helium as a tracer of groundwater age

The linear relationship between C1 14C age and the radiogenic He increases the confidence in the progression of 14C ages of groundwater DIC (Fig. 5d), including also the shallow aquifer, even if the noble gas data did not constrain the absolute 14C age. The slope of the relationship between 14C age and radiogenic He is 2.5±0.2 ×10−12 ccSTP g−1GW yr−1 G for all samples combined, and it represents the 14C-calibrated accumulation rate of He in groundwater due to the radioactive decay of U and Th from the surrounding sediment. To evaluate this result, the median value of the He accumulation rate in groundwater was calculated [Craig and Lupton, 1976; Torgersen, 1980] based on the U and Th concentrations found in the contemporary river sediment from the Ganges, the Brahmaputra and the Chittagong area rivers [Molla et al., 1997; Chowdhury et al., 1999; Granet et al., 2007; Granet et al., 2010; Chabaux et al., 2012], as well as for the average U and Th contents of the upper crust [Torgersen, 1989]. Assuming an aquifer porosity of 0.3, a sediment density of 2.75 g/cm3, and a He release factor (lambda) of 1 (i.e. the release rate equals the production rate, [Torgersen and Clarke, 1985]), the calculated He accumulation rates are 4.9×10−12 and 4.1×10−12 ccSTP g−1GW yr−1 for the Bengal Basin sediment and the average upper crust, respectively, which is within a factor of <2 relative to the 14C-calibrated rate determined from our data. The nearly 2-fold discrepancy may be explained by relative amounts of U and Th in sediments of different grain sizes; while coarser grained aquifer sands tend to by dominated quartz, U and Th concentrations are higher in the finer grained, clayey sediment. River sediments sampled in the above studies included both coarse and fine grained fractions, whereas our study was focused on aquifer settings. Moreover, our radiogenic 4He accumulation rate is also within the range of rates (1–3×10−12 ccSTP g−1GW yr−1) reported for a fluvial-deltaic formation in the Atlantic Coastal Plain of Maryland based on measured U-Th concentrations, 14C ages, and 36Cl ages [Plummer et al., 2012].

Our data from Bangladesh, as well as previous reports of the radiogenic He method [Plummer et al., 2012], suggest that the noble gas technique of He dating could possibly be applied to even older groundwater, such as that found at >200 m bgl in southern parts of Bangladesh with uncorrected 14C ages of >20,000 yr BP [Aggarwal et al., 2000; Majumder et al., 2011; Hoque and Burgess, 2012]. The He dating could work provided that it is not affected by the He diffusing upward from deep, thermogenic natural gas deposits [Dowling et al., 2003], and if care is taken to cross-calibrate the method with U-Th measurements or with other dating techniques, as in our study. The possibility of He accumulation by diffusion from thermogenic natural gas deposits cannot be entirely excluded in our dataset, but it is unlikely given the low concentrations of radiogenic He (<3×10−8 ccSTP g−1), and its absence from depths <250 m bgl may be explained by high sedimentation rates at the geologically young Bengal basin relative to He diffusion rates. Dowling et al. [2003] report radiogenic He values based on He and Ne measurements, and estimate ages of groundwater from ~100–240 m depth to be several hundred to over 1,000 years, assuming a radiogenic He accumulation rate 8-fold higher than in our study. However, if radiogenic He values of Dowling et al. [2003] are plotted versus the 14CDIC data reported for the same set of wells by Aggarwal et al. [2000], and the samples affected by He diffusion from greater depths are excluded, the result is a correlation between the radiogenic He values and 14C ages of 4.7×10−12 ccSTP g−1GW yr−1. This is closer to the radiogenic He accumulation rate reported in the present study, suggesting that the rate used by Dowling et al. [2003] may have been overestimated and that the resulting ages were underestimated.

4.4. Perspectives on Late Pleistocene and Holocene climate from groundwater tracers

4.4.1. Stable isotopes (2H/1H, 18O/16O, and 13C/12C)

If the intermediate and deep aquifers were recharged ~10 kyr BP, groundwater could contain evidence of climate change during the Pleistocene to Holocene transition. Stable isotopes appear to have recorded some of these changes and, thus, lend further support to the dating method. Changing conditions toward a wetter climate can help explain why δ13C in DIC and stable isotope ratios in the water molecule (2H/1H and 18O/16O) co-vary systematically and coherently toward lower values between 11 and 9,000 14C yr BP (Figs. 11 and S1).