Significance

Upon receipt of different cues, transcription factors bind to specific DNA sequences to recruit the general transcriptional machinery for gene expression. Chromatin modification plays a central role in the regulation of gene expression by providing transcription factors and the transcription machinery with dynamic access to an otherwise tightly packaged genome. We use Arabidopsis to study how chromatin perceives ethylene signaling, an important plant hormone in plant growth, development, and stress responses. We demonstrate that the essential factor EIN2, which mediates ethylene signaling from the endoplasmic reticulum to the nucleus, directly regulates histone acetylation through an interaction with a histone-binding protein. This study reveals the novel mechanism of how chromatin perceives the hormone signals to integrate into gene regulation.

Keywords: histone acetylation, ethylene, Arabidopsis, CRISPR/dCas9, ChIP-reChIP-seq

Abstract

Ethylene gas is essential for developmental processes and stress responses in plants. Although the membrane-bound protein EIN2 is critical for ethylene signaling, the mechanism by which the ethylene signal is transduced remains largely unknown. Here we show the levels of H3K14Ac and H3K23Ac are correlated with the levels of EIN2 protein and demonstrate EIN2 C terminus (EIN2-C) is sufficient to rescue the levels of H3K14/23Ac of ein2-5 at the target loci, using CRISPR/dCas9-EIN2-C. Chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by deep sequencing (ChIP-seq) and ChIP-reChIP-seq analyses revealed that EIN2-C associates with histone partially through an interaction with EIN2 nuclear-associated protein1 (ENAP1), which preferentially binds to the genome regions that are associated with actively expressed genes both with and without ethylene treatments. Specifically, in the presence of ethylene, ENAP1-binding regions are more accessible upon the interaction with EIN2, and more EIN3 proteins bind to the loci where ENAP1 is enriched for a quick response. Together, these results reveal EIN2-C is the key factor regulating H3K14Ac and H3K23Ac in response to ethylene and uncover a unique mechanism by which ENAP1 interacts with chromatin, potentially preserving the open chromatin regions in the absence of ethylene; in the presence of ethylene, EIN2 interacts with ENAP1, elevating the levels of H3K14Ac and H3K23Ac, promoting more EIN3 binding to the targets shared with ENAP1 and resulting in a rapid transcriptional regulation.

The plant hormone ethylene is essential for a myriad of physiological and developmental processes. It is important in responses to stress, such as drought, cold, flooding, and pathogen infection (1, 2), and modulates stem cell division (3). The common aquatic ancestor of plants possessed the ethylene signaling pathway and the mechanism has been elucidated by analysis of Arabidopsis (4). Ethylene is perceived by a family of receptors bound to the membrane of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) that are similar in sequence and structure to bacterial two-component histidine kinases (5–9). Each ethylene receptor has an N-terminal transmembrane domain, and the receptors form dimers that bind ethylene via a copper cofactor RAN1 (10, 11). Signaling from one of the receptors, ETR1, induces its physical association with the ER-localized protein RTE1 (12). The ethylene receptors function redundantly to negatively regulate ethylene responses (5) via a downstream Raf-like protein kinase called CTR1 (13, 14).

In the absence of ethylene, both the ethylene receptors and CTR1 are active, and CTR1 is associated with the ER membrane through a direct interaction with ETR1 (13). The CTR1 downstream factor, EIN2, is localized to the ER membrane, where it interacts with ETR1 (15). The protein stability of EIN2 is regulated by two F-box proteins, ETP1 and ETP2, which mediated its degradation by the ubiquitin–proteasome pathway (16). In the absence of ethylene, the CTR1-mediated phosphorylation at the C-terminal end of EIN2 (EIN2-C) leads to a repression of EIN2 activity (17). In the presence of ethylene, the EIN2-C is dephosphorylated, cleaved from the rest of the protein, and translocated into the nucleus (18) or into the P-body (19, 20). In the P-body, the EIN2-C mediates translational repression of EBF1 and EBF2 (19, 20). In the nucleus, the EIN2-C transduces signals to the transcription factors EIN3 and EIL1, which are key for activation of expression of all ethylene-response genes (21, 22). We recently discovered that acetylation at H3K23 and H3K14Ac is involved in ethylene-regulated gene activation in a manner that depends on both EIN2 and EIN3 (23, 24).

Here we show that the levels of H3K14/23Ac are positively correlated with the EIN2 protein levels and demonstrate that EIN2-C is sufficient to rescue the levels of H3K14Ac and H3K23Ac in ein2-5 at loci targeted using CRISPR/dCas9-EIN2-C. Chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by deep sequencing (ChIP-seq) and ChIP-reChIP-seq analyses reveal that EIN2-C associates with histones partially through an interaction with EIN2 nuclear-associated protein1 (ENAP1), which preferentially binds to the genome regions that are associated with actively expressed genes in both the presence and absence of ethylene. Specifically, in the presence of ethylene, ENAP1-binding regions are more accessible upon the interaction with EIN2, and more EIN3 proteins bind to the loci where ENAP1 is enriched for a quick response. Together, these results reveal EIN2-C is the key factor regulating H3K14Ac and H3K23Ac in response to ethylene and uncover a unique mechanism by which ENAP1 interacts with chromatin, potentially preserving the open chromatin regions in the absence of ethylene; in the presence of ethylene, EIN2 interacts with ENAP1, elevating the levels of H3K14/23Ac, promoting more EIN3 proteins binding to the targets shared with ENAP1 and resulting in a rapid transcriptional regulation.

Results

EIN2 Is the Key Regulator of Histone Acetylation of H3K14 and H3K23 in Response to Ethylene.

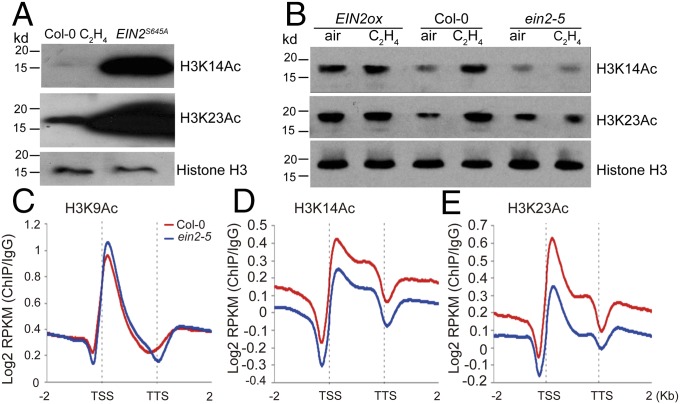

Previous work demonstrated that EIN2 is involved in the regulation of H3K14Ac and H3K23Ac levels in ethylene response (23). To explore the molecular mechanisms that underlie this regulation, we examined the levels of H3K14Ac and H3K23Ac in EIN2S645A transgenic plants, in which EIN2-C is constitutively localized to the nucleus, and these plants display a constitutive ethylene responsive phenotype (18). To our surprise, significant amounts of H3K14Ac and H3K23Ac were elevated in EIN2S645A in comparison to Col-0 plants treated with ethylene (Fig. 1A). Based on this result and our previous data (23), we speculated that EIN2-C itself is the key factor for histone acetylation in the ethylene response. We then examined the global levels of H3K14Ac and H3K23Ac in EIN2 gain-of-function plants (EIN2ox) and Col-0 and ein2-5 mutant plants treated with or without ethylene by Western blot. As previously reported, both H3K14Ac and H3K23Ac were elevated in Col-0 plants by ethylene treatment (Fig. 1B). The levels of H3K14Ac and H3K23Ac were higher in EIN2ox plants than in Col-0 plants both with and without ethylene treatments (Fig. 1B), and they were lower in ein2-5 mutant than in Col-0 plants in the absence of ethylene. No ethylene-induced elevations were detected in the ein2-5 mutant (Fig. 1B). To confirm the Western blot result at the molecular level, we revisited previously published ChIP-seq data of H3K14Ac and H3K23Ac from Col-0 and ein2-5 mutant plants (23). In the ein2-5 mutant, levels of both H3K14Ac and H3K23Ac were lower than in Col-0 plants, whereas no significant difference was detected for H3K9Ac (Fig. 1 C–E and Fig. S1). Taken together, these results suggest the EIN2-C has a key role in the regulation of histone acetylation of H3K14 and H3K23 in the ethylene response.

Fig. 1.

EIN2 is the key factor that regulates H3K14Ac and H3K23Ac in ethylene response. (A) Total histone proteins extracted from 3-d-old etiolated EIN2S645A and Col-0 seedlings were analyzed by Western blot for H3K14Ac and H3K23Ac. (B) Total histone proteins extracted from 3-d-old etiolated EIN2ox, Col-0, and ein2-5 seedlings treated with air or with ethylene were analyzed by Western blot for H3K14Ac and H3K23Ac. (C–E) Average normalized H3K9Ac (C), H3K14Ac (D), and H3K23Ac (E) ChIP-seq signals in regions 2 kbp up- and downstream of genes in ein2-5 and Col-0 plants are plotted. Transcription start sites (TSS) and transcription termination sites (TTS) were aligned.

Fig. S1.

H3K14Ac and H3K23Ac levels in ein2-5 are lower than in Col-0. Shown are heat maps showing H3K9Ac, H3K14Ac, and H3K23Ac enrichment (IgG normalized RPKM) at all genes in Col-0 and ein2-5 along with relative mRNA values. Scatter plot for mRNAs is ranked according to gene expression levels in 3-d-old Col-0 seedlings under air treatment. Heat maps are ranked according to gene expression levels.

EIN2-C Is Able to Restore the Levels of Histone Acetylation at Ethylene-Regulated Gene Loci in the ein2-5 Mutant.

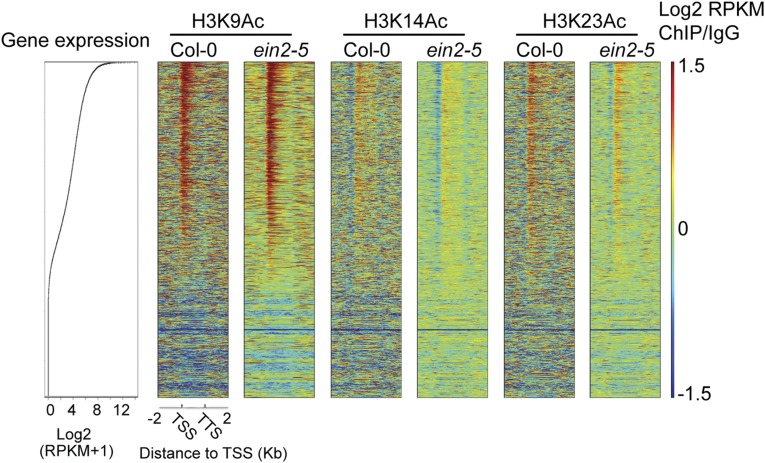

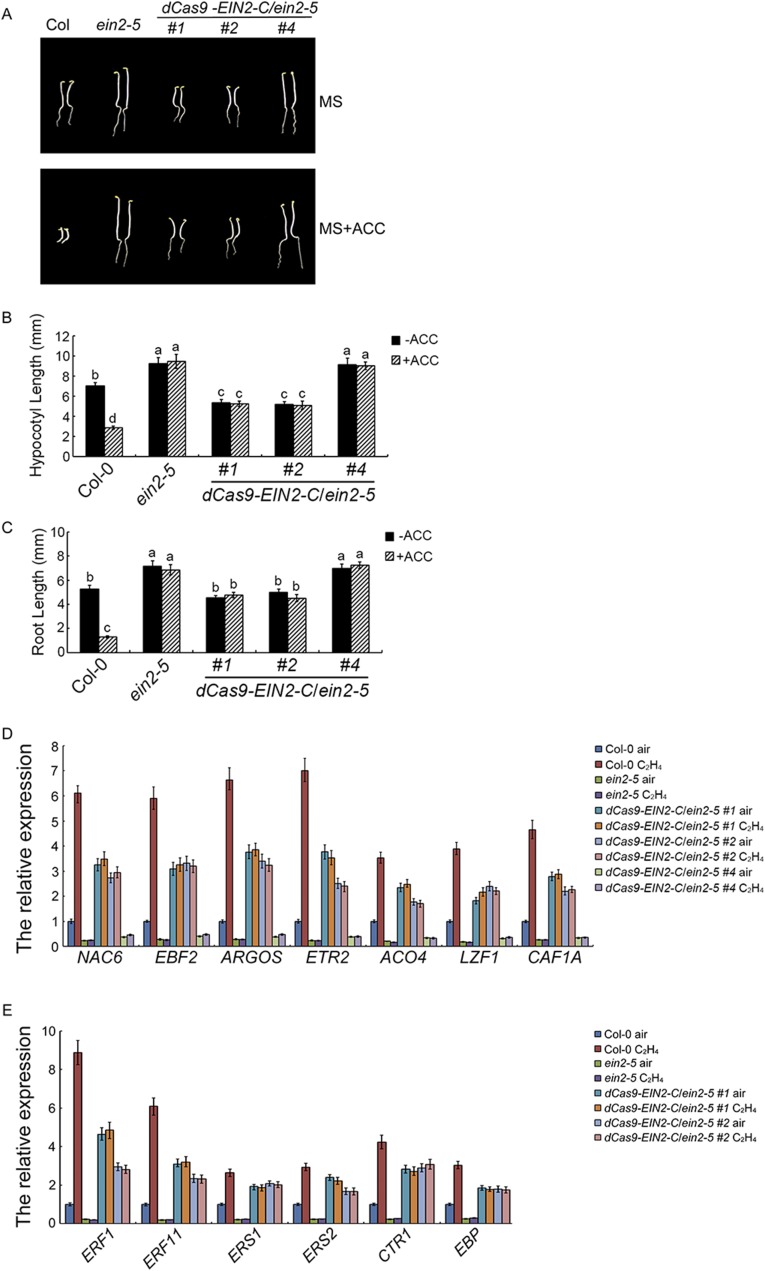

To further examine the function of EIN2-C in histone regulation, we decided to use the CRISPR-dCas9 system to test the function of EIN2-C in histone acetylation in specific loci. As shown in Fig. 2A, two previously described point mutations were introduced into Cas9 to generate the deactivated dCas9 (25) and the EIN2-C coding sequence was fused with that of dCas9. We designed two guide RNAs for targeting EBF2 promoter regions (gEBF2a and gEBF2b), regions at which H3K23Ac is elevated by ethylene in an EIN2-dependent manner (23). We also designed a guide RNA for targeting to the loci containing the EIN3-binding motif (gEIN3-T) (Fig. 2A) (22). The constructs described in Fig. 2A were introduced into the ein2-5 mutant; dCasS9-EIN2C without guide RNAs was introduced into the ein2-5 mutant and served as a control.

Fig. 2.

gRNA-EIN3-T/dCas9-EIN2-C partially restores the ein2-5 phenotype (A) Diagram showing the construction of binary vector containing both dCas9 and guide RNAs. Guide RNA expression is driven by the OsU3 promoter (39), and dCas9-EIN2-C is driven by the 35S promoter. (B) The seedling phenotype of CRISPR/dCas9-EIN2-C transgenic plants is shown. Three-day-old etiolated seedlings were grown on the medium with or without 10 µM ACC before being photographed. (C and D) The measurements of hypocotyls (C) and roots (D) in 3-d-old etiolated seedlings of the plants are shown. Plotted are means ± SD of at least 30 seedlings. Different letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05).

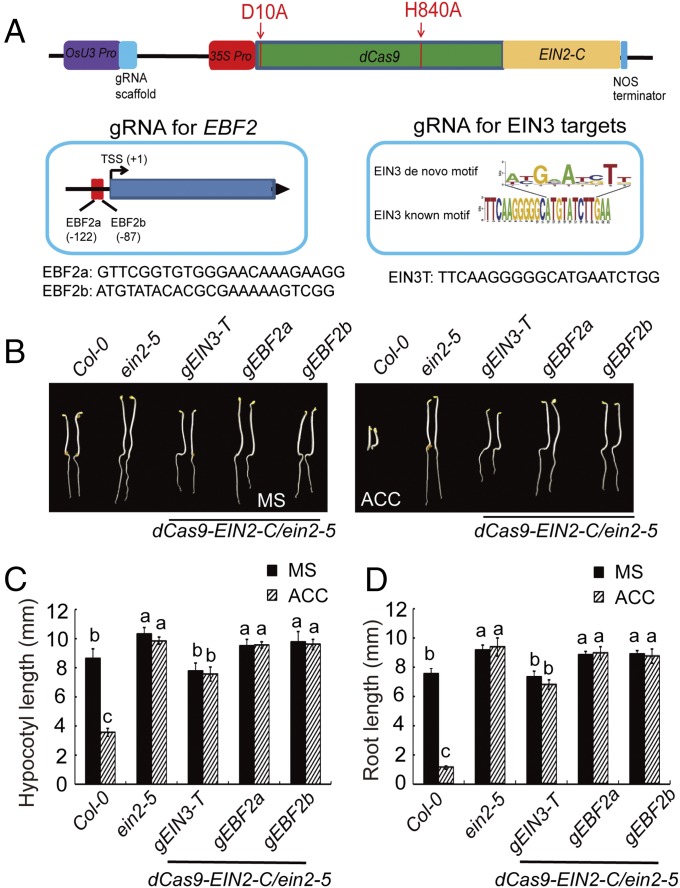

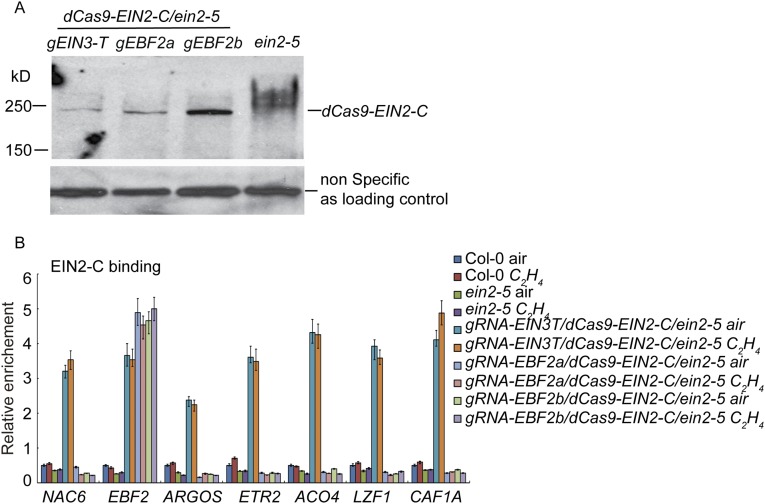

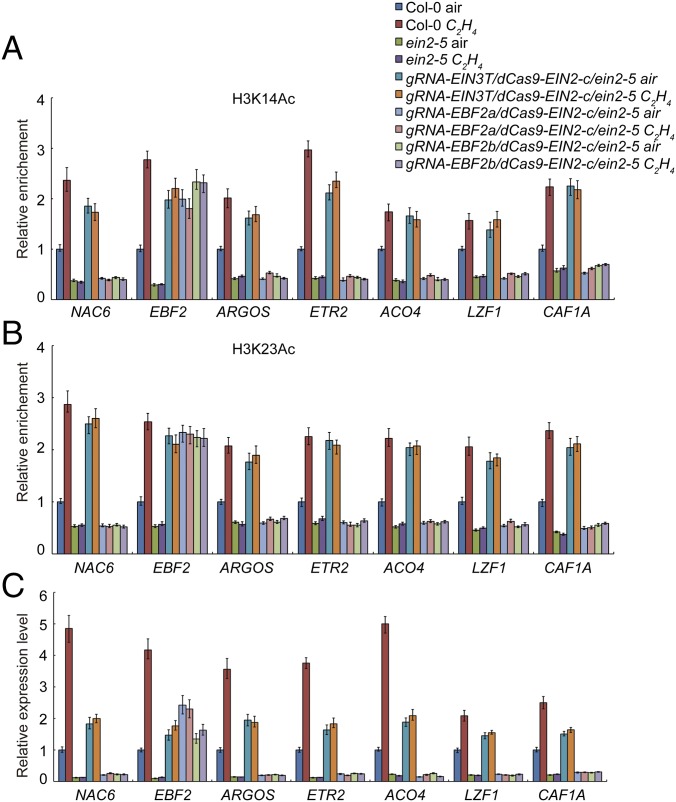

The ein2-5 mutants that expressed gRNA-EIN3-T/dCas9-EIN2-C (gRNA-EIN3-T/dCas9-EIN2-C/ein2-5) were slightly dwarfed compared with the ein2-5 mutant treated with or without ethylene, and the phenotype of gRNA-EBF2a,b/dCas9-EIN2-C/ein2-5 plants was similar to that of the ein2-5 mutant (Fig. 2B). The expression of dCas9-EIN2-C was detected in all of the plants examined (Fig. S2A). ChIP–quantitative PCR (ChIP-qPCR) of EIN2-C in gRNA-EIN3-T/dCas9-EIN2-C/ein2-5 and gRNA-EBF2a/b/dCas9-EIN2-C/ein2-5 plants confirmed the presence of EIN2-C at target loci (Fig. S2B). We next conducted ChIP-qPCR to quantify H3K14Ac and H3K23Ac in the targeted loci in Col-0, ein2-5, gRNA-EIN3-T/dCas9-EIN2-C/ein2-5, and gRNA-EBF2a,b/dCas9-EIN2-C/ein2-5 plants treated with or without ethylene. The levels of H3K14Ac and H3K23Ac in gRNA-EIN3-T/dCAS9-EIN2-C/ein2-5 and gRNA-EBF2a,b/dCas9-EIN2-C/ein2-5 plants were enriched significantly relative to those in Col-0 plants treated with air, and the levels were comparable to those in Col-0 plants treated with ethylene (Fig. 3 A and B). No significant enrichment of H3K14Ac or H3K23Ac was detected in the ein2-5 mutant with or without ethylene treatments (Fig. 3 A and B). Levels of H3K14Ac and H3K23Ac in gRNA-EIN3-T/dCas9-EIN2-C/ein2-5 and gRNA-EBF2a,b/dCas9-EIN2-C/ein2-5 were not regulated by ethylene due to the constitutive expression of EIN2-C in the target loci. In addition, no off-target activity for dCas9-EIN2-C was observed in gRNA-EIN3-T/dCas9-EIN2-C/ein2-5 and gRNA-EBF2a,b/dCas9-EIN2-C/ein2-5 plants (Fig. 3 A and B).

Fig. S2.

The protein levels and binding of dCas9-EIN2-C in transgenic plants. (A) Western blot to detect the expression of dCas9-EIN2-C protein levels. Total protein extractions from 3-d-old etiolated seedlings from the plants shown were subjected to anti-EIN2-C antibody. (B) ChIP-qPCR to examine the presence of EIN2-C in the target loci in the plants shown.

Fig. 3.

EIN2-C restores H3K14Ac and H3K23Ac levels in the ein2-5 mutant background. (A and B) ChIP-qPCR to examine the levels of H3K14Ac (A) and H3K23Ac (B) from 3-d-old etiolated seedlings of Col-0, ein2-5, and the transgenic plants, treated with air or ethylene. (C) qRT-PCR to examine the target gene expression in 3-d-old etiolated seedlings of the plants shown. Each ChIP-qPCR or qRT-PCR was repeated at least three times, and a representative result is presented.

Expression of the target genes in gRNA-EIN3-T/dCas9-EIN2-C/ein2-5 and gRNA-EBF2a,b/dCas9-EIN2-C/ein2-5 plants was significantly elevated compared with levels in Col-0 plants without ethylene treatment (Fig. 3C), indicating a positive correlation between the levels of H3K23Ac and H3K14Ac and gene expression. Additionally, levels of mRNA produced from the target loci were not subjected to ethylene regulation due to the constitutive expression of EIN2-C (Fig. 3C). Further, the dCas9-EIN2-C/ein2-5 control plants, which do not contain guide RNAs, displayed a slightly dwarf phenotype, and the gene expression in the control plants was slightly elevated, but with no locus specificity compared with gRNA-EIN3-T/dCas9-EIN2-C/ein2-5 and gRNA-EBF2a,b/dCas9-EIN2-C/ein2-5 (Fig. S3 A–E). Taken together, these results demonstrate EIN2-C is sufficient to rescue the levels of H3K14Ac and H3K23Ac in the ein2-5 mutant, and the elevation of H3K23Ac and H3K14Ac is correlated with the activation of gene expression.

Fig. S3.

dCas9-EIN2-C partially restores ein2-5 mutant phenotype. (A) The seedling phenotype of dCas9-EIN2-C/ein2-5 transgenic plants shown. Three-day-old etiolated seedlings were grown on the medium with or without 10 µM ACC before being photographed. (B and C) The measurement of hypocotyls (B) and roots (C) in 3-d-old etiolated seedlings of the plants shown. Different letters indicate significant differences. Each measurement is with at least 30 seedlings. (D and E) qRT-PCR to examine the gene expression in dCas9-EIN2-C/ein2-5 transgenic plants.

EIN2 Associates with Histone Partially Through the Interaction with ENAP1.

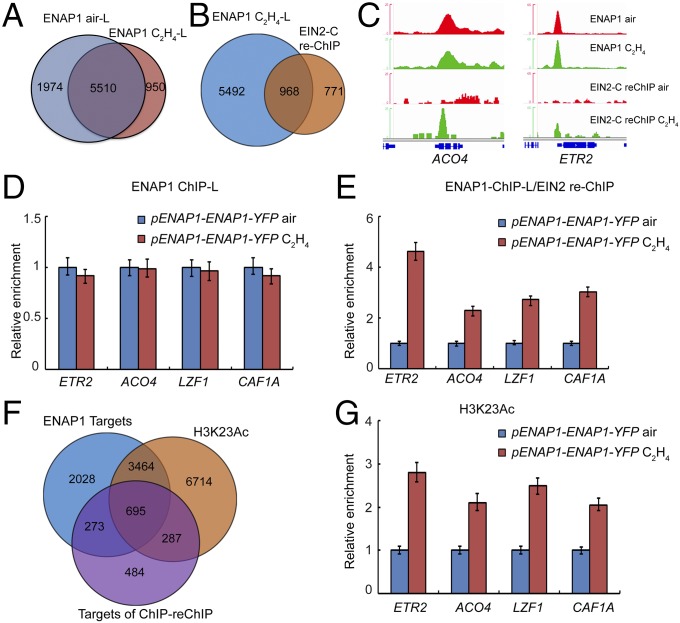

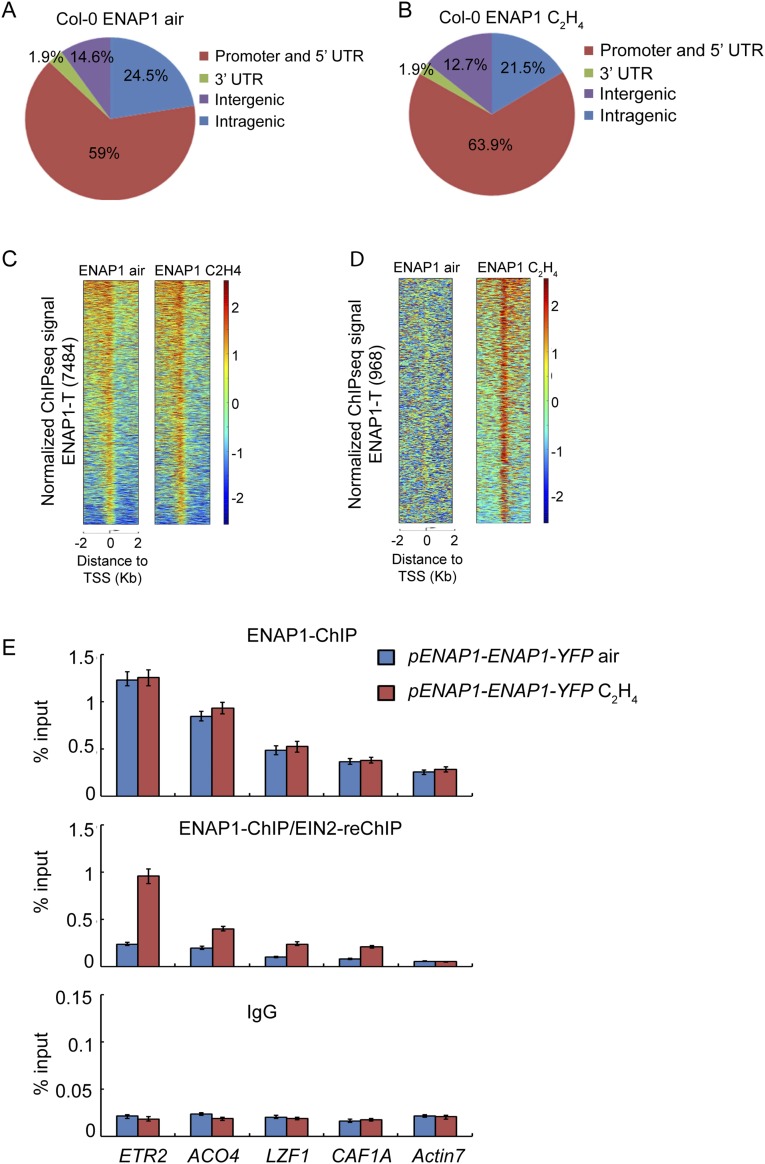

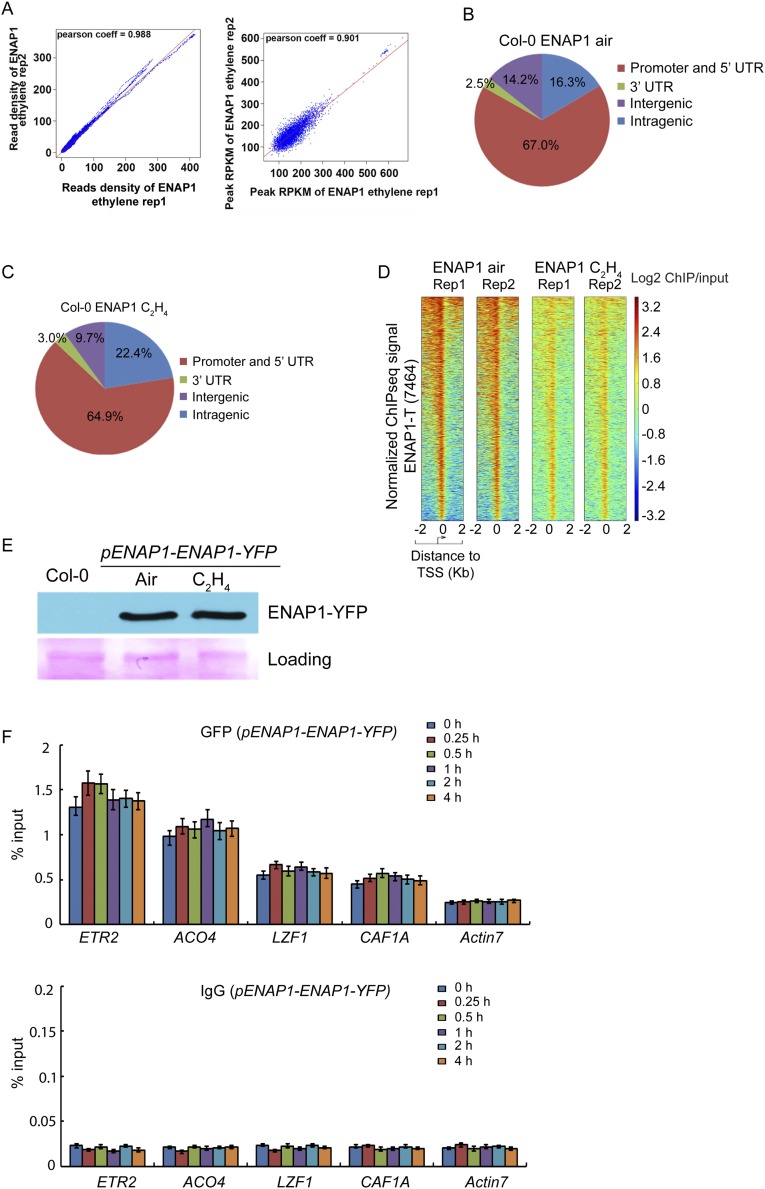

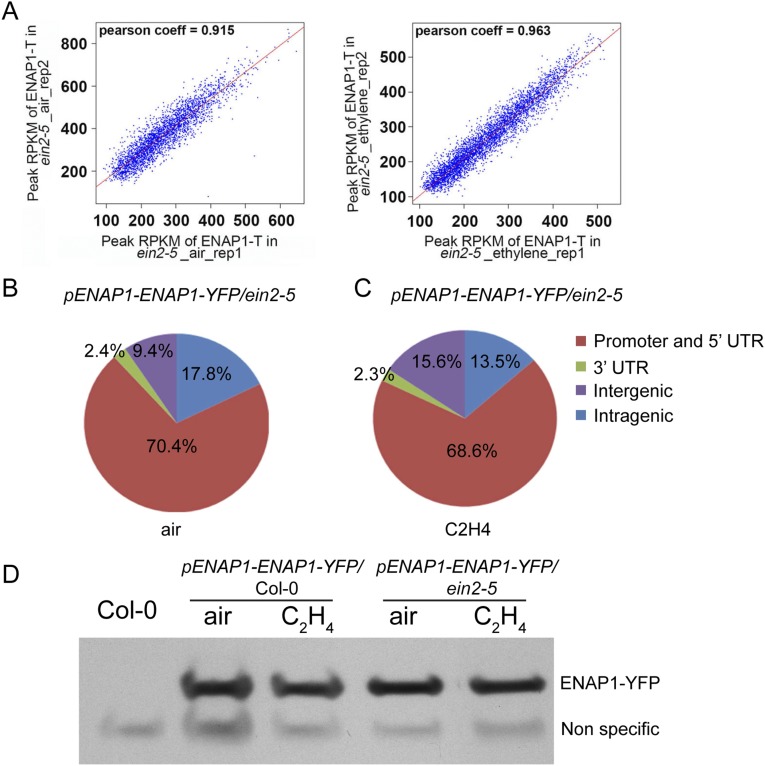

EIN2-C does not contain DNA or chromatin-binding domains, so it is not clear how EIN2-C associates with chromatin to regulate histone acetylation. Given that EIN2-C interacts with ENAP1, a histone-binding protein (23), we conducted ENAP1 ChIP sequencing and ENAP1-ChIP/EIN2-reChIP sequencing by using a long-arm cross-linker, ethylene glycol bis-(succinimidyl succinate) (EGS) in pENAP1-ENAP1-YFP plants with or without ethylene treatment. We identified 7,484 and 6,460 ENAP1 target genes in the plants treated with air and ethylene, respectively (Fig. 4A), and most peaks were located in the promoter regions (Fig. S4 A and B). By ENAP1-ChIP/EIN2-reChIP sequencing in pENAP1-ENAP1-YFP plants treated with ethylene, 1,739 genes bound by both ENAP1 and EIN2 were identified (Fig. 4B), and more than 50% of ENAP1-ChIP/EIN2-reChIP targets were overlapped with ENAP1-binding targets in the presence of ethylene (Fig. 4B), and the binding signals were significantly enriched in those targets with the presence of ethylene (Fig. S4D). The genome browser data and ENAP1-ChIP/EIN2-reChIP qPCR of selected loci further confirmed these findings (Fig. 4 C–E).

Fig. 4.

EIN2 associates with histone partially through ENAP1. (A) Venn diagram showing the ENAP1-bound targets with and without the ethylene treatments. ChIP sequencing using a long-arm cross-linker was conducted in 3-d-old etiolated seedlings of pENAP1-ENAP1-YFP seedlings treated with air or ethylene. (B) Comparison of ENAP1-bound targets with ENAP1-ChIP/EIN2-C-reChIP binding targets. The first ChIP was conducted by using anti-GFP antibody, and the second ChIP (reChIP) was conducted by using anti-EIN2-C antibody with a long-arm cross-linker. (C) Genome browser traces of ENAP1 ChIP-seq and the ENAP1-ChIP/EIN2-C-reChIP-seq data from representative genes. (D) Fold change in ENAP1-ChIP-qPCR signal relative to Col-0 in air obtained using a long-arm cross-linker in both air and ethylene. (E) ChIP-qPCR of selected loci to confirm the ChIP-reChIP-seq result of EIN2-C. (F) Venn diagram showing the overlap of ENAP1-bound targets with H3K23Ac-marked genes. (G) ChIP-qPCR of H3K23Ac showing the elevation of H3K23Ac in EIN2-C–associated genes.

Fig. S4.

ENAP1 ChIP-seq peaks distribution and EIN2-reChIP-seq binding signaling by using a long-arm cross-linker. (A and B) Venn diagram of ENAP1-binding profiles showing most ENAP1 binding enriched in the promoter regions in Col-0 by using a long-arm cross-linker both with (B) and without (A) ethylene treatments. (C) Heat maps show ENAP1-binding signal around 2 kb up- and downstream of TSS in target genes with and without ethylene treatments. The ChIP-seq was done by using a long-arm cross-linker. (D) Heat maps show ENAP1-binding signal around 2 kb upstream and 2 kb downstream of the TSS in ENAP1 ChIP/EIN2-C reChIP target genes with and without ethylene treatments. (E) ChIP-qPCR of ENAP1 and ENAP1 ChIP/EIN2-C reChIP in response to ethylene by using a long-arm cross-linker presented relative to input.

We then examined the association of ENAP1-ChIP/EIN2-reChIP target genes with H3K23Ac. We found that more than 70% of the genes bound by ENAP1 and EIN2 were also marked by H3K23Ac in the presence of ethylene (Fig. 4F). ChIP-qPCR of H3K23Ac further confirmed the association of EIN2-C with H3K23Ac (Fig. 4G and Fig. S4E).

EIN2-C Regulates ENAP1 Binding in Ethylene Signaling.

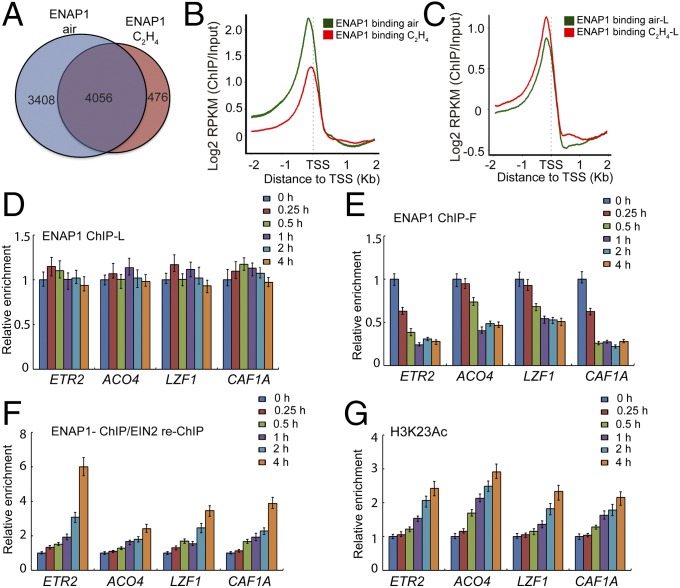

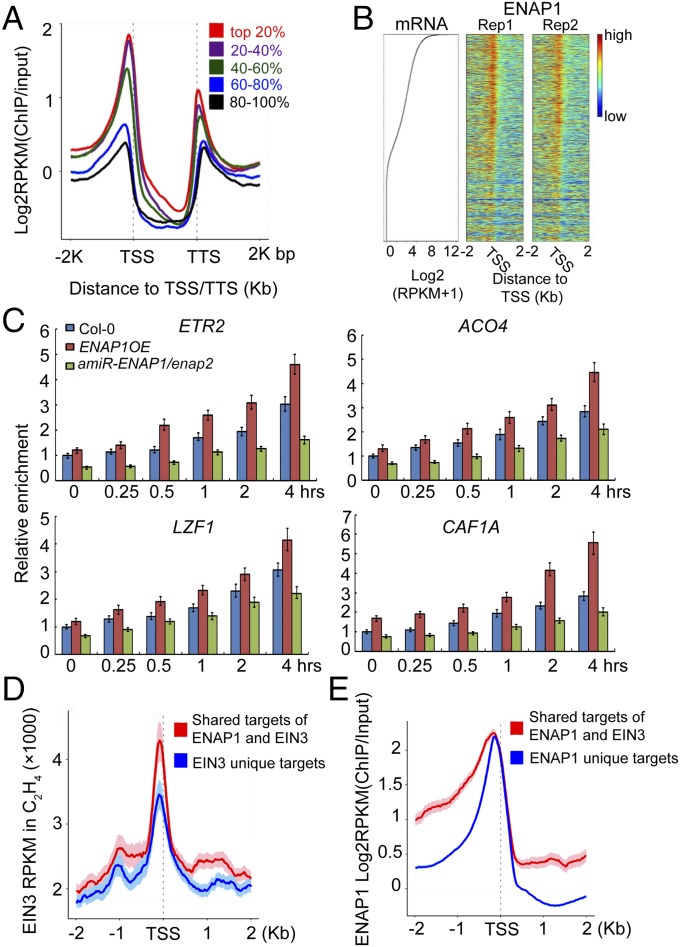

To explore how EIN2-C functions through ENAP1 in response to ethylene, we first examined ENAP1 binding both with and without ethylene treatments by ChIP-seq, using formaldehyde as a cross-linker (Fig. S5A). Nearly 7,000 and 5,000 ENAP1-binding targets were identified from the plants treated with air and ethylene, respectively (Fig. 5A). Most of the ENAP1 binding was in the promoter regions under both conditions (Fig. S5 B and C). To our surprise, we detected down-regulation of ENAP1 binding upon ethylene treatment (Fig. 5B and Fig. S5D), even though the protein levels of ENAP1 did not differ in the presence and absence of ethylene (Fig. S5E). However, previously we did not detect ethylene-induced differential binding of ENAP1 by using a long-arm cross-linker both in ChIP-seq and in ChIP-qPCR (Figs. 4D and 5C and Fig. S4C).

Fig. S5.

ENAP1 ChIP-seq peaks distribution and binding signaling by using a long-arm cross-linker. (A) Scatter plots of mapped read density showing quality of ChIP-seq data of ENAP1 in Col-0 treated with air (Right) and scatter plots of optimal peaks RPKM showing quality of ChIP-seq data of ENAP1 in Col-0 treated with air (Left). (B and C) Venn diagram of ENAP1-binding profiles showing most ENAP1 binding enriched in promoter regions both in air (B) and in ethylene (C). (D) Heat maps show ENAP1-binding signal around 2 kb up- and downstream of TSS in target genes with and without ethylene treatments. The ChIP-seq was done by using formaldehyde. (E) Western blot assay to show ENAP1 protein levels in indicated plants treated with air or ethylene. (F) ChIP-qPCR assay to test ENAP1 binding in the loci indicated with different periods time of ethylene treatment (Upper) and the input control of ChIP-qPCR (Lower).

Fig. 5.

ENAP1 binding is regulated by ethylene treatment. (A) Venn diagram showing overlap of ENAP1-bound targets in air and ethylene. The ChIP-seq was done by using formaldehyde as a cross-linker in 3-d-old etiolated pENAP1-ENAP1-YFP seedlings treated with air or ethylene. (B) Mean enrichment profiles [Log2 reads per kilobase per million mapped reads (RPKM) (ChIP/Input)] around 2 kb up- and downstream of TSSs in target genes with or without ethylene treatment using formaldehyde cross-linker. (C) Mean enrichment profiles around ±2 kb of TSSs in target genes with or without ethylene treatment using a long-arm cross-linker. (D) ChIP-qPCR to examine ENAP1 binding in pENAP1-ENAP1-YFP plants treated with ethylene for different periods of time by using a long-arm cross-linker. (E) ChIP-qPCR using a formaldehyde cross-linker to examine ENAP1 binding in pENAP1-ENAP1-YFP 3-d-old etiolated plants treated with ethylene for different periods of time relative to no treatment. (F) ChIP-reChIP PCR to examine the binding of EIN2 through the interaction with ENAP1. The first ChIP was performed with anti-GFP antibody and reChIP with anti-EIN2-C antibody in pENAP1-ENAP1-YFP plants treated with ethylene for different periods of time by using a long-arm cross-linker. (G) ChIP-qPCR to examine H3K23Ac in pENAP1-ENAP1-YFP 3-d-old etiolated seedlings treated with ethylene for indicated times.

We speculate that the differential binding of ENAP1 detected by using formaldehyde is due to the type of interaction that occurs between ENAP1 and EIN2 upon ethylene treatment. To test this idea, we conducted ENAP1-ChIP-qPCR, using formaldehyde or the long-arm cross-linker in plants treated with ethylene for different periods of time. No significant differences in ENAP1 binding were detected over time, using the long-arm cross-linker (Fig. 5D and Fig. S5F). However, using the formaldehyde cross-linker, ENAP1 binding was decreased after 15 min of ethylene treatment (Fig. 5E). This is the time frame in which the nuclear translocation of EIN2-C is observed (18).

To explore the connection between the down-regulation of ENAP1 binding and its interaction with EIN2, we conducted ENAP1-ChIP/EIN2-reChIP-qPCR in plants treated with ethylene for different periods of time as shown in Fig. 4 D and E. The levels of EIN2 binding detected were higher in plants treated with ethylene (Fig. 5F), which anticorrelated with ENAP1 binding. Further, the ChIP-qPCR assay showed that the levels of H3K23Ac were elevated with the same treatments (Fig. 5G), which showed a positive correlation with the levels of EIN2 binding. Taken together, these results suggest that in the presence of ethylene, changes in ENAP1 binding are caused by an interaction with EIN2-C, which results in an increase in H3K23Ac over the target loci.

EIN2 Is Required for Alterations in ENAP1 Binding in the Ethylene Response.

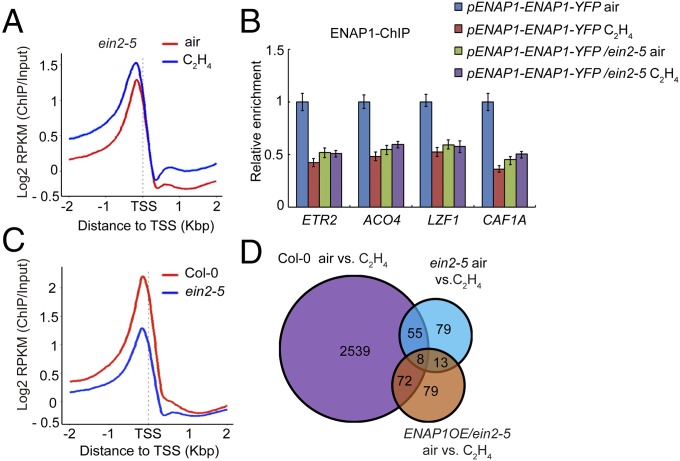

To further explore how EIN2 regulates ENAP1 binding in response to ethylene, we examined ENAP1 binding by ChIP-seq in the ein2-5 mutant both with and without ethylene treatments (Fig. S6A). The ENAP1 binding in the ein2-5 mutant was enriched in the promoter regions in both conditions as it was in Col-0 plants (Fig. S6 B and C). However, the ethylene-induced change in ENAP1 binding was not detected in the ein2-5 mutant (Fig. 6A). These results were confirmed by ChIP-qPCR in ENAP1-YFP/ein2-5 and ENAP1-YFP/Col-0 plants (Fig. 6B).

Fig. S6.

ENAP1 ChIP-seq peaks distribution and protein levels in the ein2-5 mutant. (A) Scatter plots of optimal peaks RPKM show quality of ChIP-seq data of ENAP1 in ein2-5 treated with air or ethylene. (B and C) Venn diagram of ENAP1-binding profiles showing most ENAP1 binding enriched in promoter regions in the ein2-5 mutant both without (B) and with (C) ethylene treatments. The ChIP-seq was conducted by using formaldehyde. (D) Western blot to examine the protein levels of ENAP1 in ein2-5 in response to ethylene. The total proteins were extracted from 3-d old etiolated seedlings of Col-0 or pENAP1-ENAP1-YFP treated with air or ethylene. GFP antibody was used to examine ENAP1-YFP proteins.

Fig. 6.

Ethylene-induced change of ENAP1 binding is EIN2 dependent. (A) Mean enrichment of ENAP1 ChIP-seq signals along target gene bodies in 3-d-old etiolated ein2-5 seedlings treated with air or ethylene. Genes were ranked according to relative mRNA expression levels and divided into five equal sets. (B) ENAP1-ChIP-qPCR in 3-d-old etiolated Col-0 and pENAP1-ENAP1-YFP and PENAP1-ENAP1-YFP/ein2-5 seedlings. (C) Mean enrichment of ENAP1-ChIP-seq signals along 2 kb up- and downstream of TSSs of target genes in Col-0 or ein2-5 mutant seedlings. (D) Overlap of genes regulated by ethylene in Col-0, ein2-5, and ENAP1OE/ein2-5 seedlings.

We also noticed that even though ENAP1 protein levels in Col-0 plants were similar to those in the ein2-5 mutant (Fig. S6D), the average ENAP1-binding signals in the ein2-5 mutant were lower than in Col-0 plants even without ethylene treatment (Fig. 6B), and this result was further confirmed by comparing the ChIP-seq data from ENAP1 in Col-0 and ein2-5 mutant plants (Fig. 6C). We then examined the gene expression in ein2-5 and ENAP1OE/ein2-5 plants with or without ethylene treatment. As in the ein2-5 mutant, the ethylene-induced gene expression was largely impaired in ENAP1OE/ein2-5 plants. More than 92% of genes regulated by ethylene in Col-0 plants were not differentially expressed in ENAP1OE/ein2-5 plants in the presence and absence of ethylene (Fig. 6D). These results provide additional molecular evidence that the function of ENAP1 in the ethylene response is EIN2 dependent.

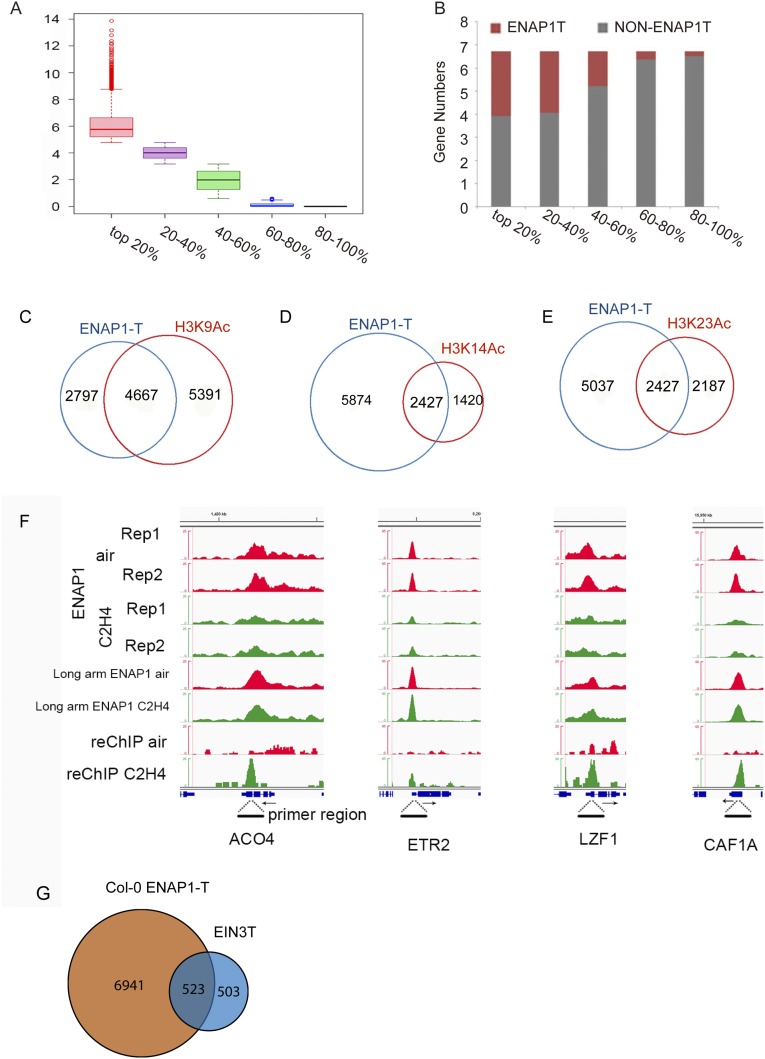

ENAP1 Binds to Active Gene Regions and EIN3 Prefers to Bind ENAP-Targeted Regions.

The majority of ENAP1 binding was in the promoter regions (Figs. S4 A and B and S5 B and C), suggesting the potential function of ENAP1 in gene regulation. To examine whether there is a correlation between ENAP1 binding and gene expression that would indicate a function in regulation of gene expression, we divided the ≈30,000 genes in the Arabidopsis genome into five groups based on their expression levels in 3-d-old etiolated Col-0 seedlings (Fig. S7A). We then examined average ENAP1 ChIP-seq signals in the five groups of genes. Near transcription start-site (TSS) regions, highly expressed genes showed significantly higher levels of average ENAP1 ChIP signals than in other groups of genes (Fig. 7 A and B). The majority of the ENAP1-bound genes were in the top two groups of most highly expressed genes (Fig. S7B), suggesting that ENAP1 prefers to bind actively transcribed gene regions. Histone acetylation is a well-known mark of gene activation, and we found that about 50% of H3K9Ac, 63% of H3K14Ac, and 53% of H3K23Ac marked genes were bound by ENAP1 (Fig. S7 C–E).

Fig. S7.

ENAP1 associates with active genes. (A) Diagram to show the genes were divided into five groups based on their expression genome-wide. (B) Bar chart showing the distribution of ENAP1-binding target genes in the five groups shown in A. (C–E) Venn diagrams to show the overlap between ENAP1-binding targets with H3K9Ac (C), H3K14Ac (D), and H3K23Ac (E) marked genes. (F) Genome browser of ENAP1 ChIP-seq with air or ethylene treatment using formaldehyde (Top four panels) or using a long-arm cross-linker (Middle two panels) and ChIP-reChIP of EIN2 (Bottom two panels). The dotted lines indicate the PCR-amplified loci in FAIRE-qPCR. (G) Venn diagram to show genes bound by both EIN3 and ENAP1.

Fig. 7.

ENAP1 prefers to bind actively transcribed genes. (A) Mean enrichment of ENAP1 ChIP-seq signals along gene bodies in 3-d-old etiolated pENAP1-ENAP1-YFP seedlings. Genes were ranked according to relative mRNA expression levels and divided into five equal sets. (B) Heat maps show ENAP1 enrichment in all genes in Arabidopsis along with relative mRNA values. Shown is a scatter plot for mRNAs ranked according to gene expression levels in 3-d-old Col-0 seedlings under air treatment. Heat maps are ranked according to gene expression levels. (C) FAIRE-qPCR showing ENAP1 binding is associated with DNA accessibility in the plants shown. (D) Mean enrichment of EIN3 ChIP-seq signals (RPKM) 2 kb up- and downstream of TSSs of the genes cobound by ENAP1 and EIN3 (red) or of the genes bound only by EIN3 (blue) (22). (E) Mean enrichment of ENAP1 ChIP-seq signals around 2 kb up- and downstream of TSSs of the genes cobound by ENAP1 and EIN3 (red) or of the genes bound only by ENAP1 (blue).

To further confirm that ENAP1 prefers to bind actively transcribed gene regions, we examined DNA accessibility at the ENAP1-associated regions, using formaldehyde-assisted isolation of regulatory elements (FAIRE)-qPCR in ENAP1ox, amiR-ENAP1/2, and Col-0 plants untreated or treated with ethylene for different periods of time (Fig. 7C and Fig. S7F). Compared with Col-0 plants, the DNA accessibility in ENAP1-bound regions was slightly higher in ENAP1ox plants and significantly lower in amiRENAP1/enap2 plants, and differences became more significant with longer periods of ethylene treatments (Fig. 7C and Fig. S7F). This result further confirms that ENAP1 associates with actively transcribed gene regions.

EIN3 is the key transcription factor in the ethylene signaling pathway (23). Therefore, we examined the average EIN3 ChIP-seq signals and ENAP1 ChIP-seq signals in TSS regions in the genes cobound by ENAP1 and EIN3 or in the genes bound only by EIN3. The average EIN3-binding signals were significantly higher in cobound genes than in the genes bound only by EIN3 (Fig. 7D and Fig. S7G). No significant differences were detected for the average ENAP1 ChIP-seq signals near TSS regions of genes that were cobound with EIN3 or bound only by ENAP1 (Fig. 7E), showing that EIN3 prefers to bind to ENAP1 target regions, which are more accessible.

Discussion

Histone acetylation has been demonstrated to function in different plant hormones (23, 26–29), and several histone deacetylases are known to be involved in the regulation of gene expression (30–37). The data presented here showed that the C-terminal domain of EIN2 (EIN2-C) is the key factor that drives alterations in histone acetylation during the ethylene response. However, the exact biochemistry functions of EIN2-C remain unknown. We performed a careful motif search in the EIN2-C but no histone acetyltransferase (HAT) motif was identified. It is possible that in the presence of ethylene, EIN2-C is translocated into the nucleus, where it functions as an important scaffold protein to recruit other components required for regulating histone acetylation. As shown by Western blot, H3K14Ac and H3K23Ac were significantly elevated in EIN2S645A plants, and therefore it is possible that EIN2-C functions as a HAT. Even though it does not contain a known HAT motif, it is possible that, when properly folded in vivo, EIN2-C forms a HAT activity domain. A crystal structure of EIN2-C will provide insight into how EIN2-C functions. In addition, isolation of the EIN2-C–containing protein complex that forms in the nucleus in the presence of ethylene will reveal whether EIN2-C associates with a known HAT.

In this study, we observed differences in ENAP1 binding when different cross-linkers were used in ChIP-seq. The differences were not due to the protein levels, because ENAP1 protein levels are similar in the presence and absence of ethylene (Fig. S5D). We then revisited our ChIP-seq data and found that similar total reads and mapping rates were obtained using ENAP1 ChIP-seq both with and without ethylene treatments (Table S1), showing that the ChIP-seq data are not a reason for ENAP1-binding change. Analyses of ENAP1 binding in response to ethylene performed using different cross-linkers strongly suggest that the proximity of ENAP1 to DNA is altered by ethylene treatment. The elevation of H3K23Ac in the presence of ethylene (Fig. 5G) and the FAIRE-qPCR in Fig. 7C provide additional evidence to support our hypothesis that the chromatin is more accessible in ENAP1-bound regions in the presence of ethylene than in the absence of ethylene. Further, we showed that EIN2-C shares a subset of binding targets with ENAP1 by ChIP-reChIP-seq (Fig. 4); all these data suggest a potential mechanism that in the presence of ethylene, ENAP1 interacts with EIN2-C, which leads to the elevation of H3K14Ac and H3K23Ac, resulting in the chromatin regions being more open in the presence of ethylene.

Table S1.

The processing of reads and mapped reads from ChIP-seq of ENAP1 in Col-0 treated with air or ethylene

| Sample name | Repeat | Total_raw_reads | bwa_mapped | bwa_mapped_rate, % |

| COL_ENAP1air | rep1 | 20,599,733 | 13,918,922 | 67.57 |

| rep2 | 23,402,905 | 16,761,706 | 71.62 | |

| COL_ENAP1air-input | rep1 | 20,426,731 | 14,087,335 | 68.97 |

| rep2 | 21,472,909 | 14,703,415 | 68.47 | |

| COL_ENAP1_C2H4 | rep1 | 26,488,258 | 17,211,580 | 64.98 |

| rep2 | 32,226,232 | 19,252,253 | 59.74 | |

| COL_ENAP1_C2H4-input | rep1 | 31,889,975 | 17,862,059 | 56.01 |

| rep2 | 27,117,516 | 15,203,841 | 56.07 |

A previous study showed that the ethylene response can be detected within 30 min at the transcriptional level (22), and we observed that in the presence of ethylene, EIN3, the key transcription factor in ethylene signaling (21, 22, 38), prefers to bind ENAP1-targeted regions (Fig. 7 D and E). Furthermore, in the absence of ethylene, ENAP1 prefers to bind to the DNA regions that are accessible (Fig. 7 A–C), indicating that ENAP1 may serve as a place holder in open chromatin regions to allow EIN3 to quickly bind to target loci for a rapid ethylene response. It should be noted that not all of the binding targets of EIN3 are overlapped with ENAP1-bound regions (Fig. 7D). Due to the weak ethylene-responsive phenotype of amiR-ENAP1/enap2 plants, we speculate that other factors in addition to ENAP1 are involved in EIN3-mediated gene regulation.

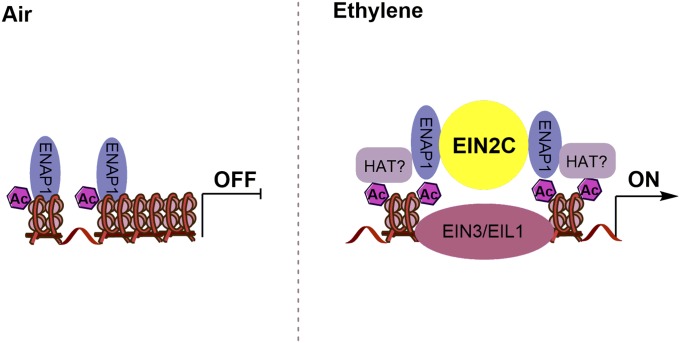

Based on data shown here, we propose a unique function mechanism, by which ENAP1 interacts with histones in the absence of ethylene, potentially preserving the open chromatin status. This enables a rapid response to ethylene stimulation. In the presence of ethylene, EIN2 interacts with ENAP1 and other unidentified factors, elevating H3K14Ac and H3K23Ac levels and promoting EIN3 binding to the targets shared with ENAP1, and resulting in a rapid transcriptional response to the presence of ethylene (Fig. S8). Further examining the binding activity of EIN2 and ENAP1 in the ein3-1 mutant will provide more insight into the molecular function of EIN3 in histone acetylation in the ethylene response.

Fig. S8.

The model for EIN2-C in the regulation of histone acetylation. ENAP1 interacts with histones in the absence of ethylene, potentially preserving the open chromatin status (Left). In the presence of ethylene, EIN2 interacts with ENAP1 and other unidentified factors, elevating H3K14Ac and H3K23Ac levels and promoting EIN3 binding to the targets shared with ENAP1, resulting in a rapid transcriptional response to the presence of ethylene (Right).

Materials and Methods

Details of plant growth and measurements of roots and hypocotyls, ChIP-seq and RNA-seq processing and analysis, and ChIP-PCR and FAIRE-qPCR analysis are described in SI Materials and Methods. All of the primers for ChIP-qPCR, qPCR, and FAIRE qPCR are listed in Table S2.

Table S2.

Primers used in this paper

| Primer name | Sequence | Purpose |

| NAC6 ChIP qF | TAGAGAGGAGCTTCGTTGCTC | ChIP-qPCR |

| NAC6 ChIP qR | GTTTGGAGACGAAGAGGGAAG | ChIP-qPCR |

| EBF2 ChIP qF | AACTTCCACCGTACACCTCTC | ChIP-qPCR |

| EBF2 ChIP qR | GAACCCTAGAAGATTAGGGC | ChIP-qPCR |

| ARGOS ChIP qF | CCTTGTGATTGTGGAGGAAGA | ChIP-qPCR |

| ARGOS ChIP qR | GGCTGACAAATGTGAGGAGA | ChIP-qPCR |

| ETR2 ChIP qF | CGGCTCCTACCTTTACTTAC | ChIP-qPCR |

| ETR2 ChIP qR | ATGCCGGAGATGATTAGTGC | ChIP-qPCR |

| ACO4 ChIP qF | GAGTGTGGAACATAGAGTGC | ChIP-qPCR |

| ACO4 ChIP qR | GCGCCGGAAAAATAACAGAG | ChIP-qPCR |

| LZF1 ChIP qF | GCGTTTTCTGGATGAGTTTGAG | ChIP-qPCR |

| LZF1 ChIP qR | AAGCCCAACAAAGAGCAGC | ChIP-qPCR |

| CAF1A ChIP qF | CTTAAAGCTAACGTCGACGC | ChIP-qPCR |

| CAF1A ChIP qR | TGAAGATCGTCACCGAGGTC | ChIP-qPCR |

| Actin7 ChIP qF | CGGGCTAATTCATTTGAACC | ChIP-qPCR |

| Actin7 ChIP qR | GGTGACCTGGCTTTCACACT | ChIP-qPCR |

| NAC6 qF | CTCTGTTTTACTCGGATCCTC | qPCR |

| NAC6 qR | ACGAATCACGACCGTCGAAAG | qPCR |

| EBF2 qF | TGATGTTGGTCTTGGTGCTGTTGC | qPCR |

| EBF2 qR | ATTCCAGGACACCGTGAAAGGTCA | qPCR |

| ARGOS qF | TGGTCTAACGGCATCTCTG | qPCR |

| ARGOS qR | GAGAAGAAGGCATGAAGGC | qPCR |

| ETR2 qF | GGAGTTGTGAGAAAGCCAGTGG | qPCR |

| ETR2 qR | GAGAAGTTGGTCAGCTTGC | qPCR |

| ACO4 qF | CTCTGCTGTCAAGTTTCAGG | qPCR |

| ACO4 qR | TCACGCAGTGGCCAATGGTC | qPCR |

| LZF1 qF | CTGGTCTAAACTGGCCTAAG | qPCR |

| LZF1 qR | CGTTTCCCAACCCTTTGATTCG | qPCR |

| CAF1A qF | CGGATAGTTTGCTTACGTGG | qPCR |

| CAF1A qR | CCTCAAGCCCATACAAAACC | qPCR |

| UBQ10 qF | CACACTCCACTTGGTCTTGCGT | qPCR |

| UBQ10 qR | TGGTCTTTCCGGTGAGAGTCTTCA | qPCR |

| ETR2 FAIRE F | CGGCTCCTACCTTTACTTAC | FAIRE |

| ETR2 FAIRE R | ATGCCGGAGATGATTAGTGC | FAIRE |

| ACO4 FAIRE F | GTTCACGCTTTTTGGTCGAC | FAIRE |

| ACO4 FAIRE R | GGTTTTTTGGACCACACACATCC | FAIRE |

| LZF1 FAIRE F | CACGTGTCTATCCATTGTTCACTC | FAIRE |

| LZF1 FAIRE R | AAAAGAGAGGGTCTCAGTGCAC | FAIRE |

| CAF1A FAIRE F | AGTAGAGAGTGGCCAACTTG | FAIRE |

| CAF1A FAIRE R | GAGTTGCGAGGAAGAAGAAGTG | FAIRE |

| Actin7 FAIRE F | CGGGCTAATTCATTTGAACC | FAIRE |

| Actin7 FAIRE R | GGTGACCTGGCTTTCACACT | FAIRE |

| ERF1 qF | ACCGCTCCGTGAAGTTAGATAATG | qPCR |

| ERF1 qR | ATCCTAATCTTTCACCAAGTCCCAC | qPCR |

| ERF11 qF | GATTCTTCGTCGGTGGTGATG | qPCR |

| ERF11 qR | TCAGTTCTCAGGTGGAGGAG | qPCR |

| ERS1 qF | CATCATCAGGCTTGGTATCTGC | qPCR |

| ERS1 qR | TCACCAGTTCCACGGTCTG | qPCR |

| ERS2 qF | TGTTTTCCGGTTTCAACTCCGG | qPCR |

| ERS2 qR | TCAGTGGCTAGTAGACGGAG | qPCR |

| CTR1 qF | CAATGAGCCATGGAAGCGTC | qPCR |

| CTR1 qR | TTACAAATCCGAGCGGTTGG | qPCR |

| EBP qF | TTGAGCTGGACGGTAACAC | qPCR |

| EBP qR | CTCATACGACGCAATGACATC | qPCR |

| PHYA qF | GTTAGCCGGAAACTGGTGAAG | qPCR |

| PHYA qR | CTACTTGTTTGCTGCAGCG | qPCR |

| WRKY4 qF | GCTAAATCAAGCAGCCATGC | qPCR |

| WRKY4 qR | AACGGGCTGTTGCTGCTGCTGT | qPCR |

| BES1 qF | GCAGCAATCCAAGAGATTGG | qPCR |

| BES1 qR | CAAGCGTGAGCTCTAGATC | qPCR |

SI Materials and Methods

Plant Growth and Measurements of Roots and Hypocotyls.

Arabidopsis seeds were surface sterilized in 50% bleach with 0.01% Triton X-100 for 15 min and washed five times with sterile, doubly distilled H2O before plating on Murashige & Skoog (MS) medium (4.3 g MS salt, 10 g sucrose, pH 5.7, 8 g phytoagar per liter). After 3–4 d of cold (4 °C) treatment, the plates were wrapped in foil and kept at 24 °C in an incubator before the phenotypes of seedlings were analyzed. Ethylene treatment of Arabidopsis seedlings was performed by growth of seedlings on MS plates in air-tight containers in the dark supplied with either a flow of hydrocarbon-free air (Zero grade air; AirGas) or hydrocarbon-free air with 10 ppm ethylene as previously described (14).

Plasmid Construction.

pRGEB31 vector (Addgene; plasmid no. 51295), has been used for gene targeting and precise genome editing in plants (39). The enzymatic activity of the Cas9 nuclease was abolished by mutation of the RuvC and HNH domains, generating the nuclease-null deactivated Cas9 (dCas9) (40) for pRGEB31 (pRGEB31-dCas9). All PCR amplifications were carried out using Phusion High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (BioLabs M0530L). gRNA sequences were cloned into the BsaI (New England Biolabs) site in pRGEB31-dCas9 as previously described (39).

ChIP-PCR Analysis.

Briefly, 3-d-old etiolated seedlings treated with air or ethylene were harvested and cross-linked in 1% formaldehyde, and the chromatin was isolated. The anti-green fluorescent protein antibodies (Thermo Fisher Scientific) were added to the sonicated chromatin followed by incubation overnight to precipitate bound DNA fragments. DNA was eluted and amplified by primers corresponding to genes of interest.

ChIP-seq and RNA-seq Processing and Analysis.

We conducted a dual cross-linking procedure, using the additional cross-linker EGS (Thermo Fisher Scientific) along with formaldehyde according to ref. 41. Tissue was first cross-linked with 1.5 mM EGS in PBS for 30 min under vacuum. Formaldehyde was subsequently added to a concentration of 1% and further incubated for 10 min under vacuum.

To show ChIP binding signals surrounding TSSs or in gene body regions, genome-wide read coverage of each sample was first calculated by the bamCompare tool in deepTools version 1.5.11 (42). The average signal for each position in the two replicates, after removing the top and bottom one percentiles, was plotted in scatter plots. Differentially binding signals generated using the data in 400-bp regions centered at TSSs were calculated and plotted in box plots. Heat maps of ChIP-seq enrichment across TSS or gene body regions were calculated using deepTools version 1.5.11 (42).

Three-day-old etiolated seedlings treated with air or with 4 h of ethylene were harvested and total RNA was extracted using Plant RNA Purification Reagent (Invitrogen) as in refs. 18 and 19. Total RNA (4 µg) was used to prepare RNA-seq libraries, using a TruSeq RNA Library Prep Kit (Illumina) as described previously (43). Multiplexed libraries were sequenced on an Illumina Hi-Seq 2000. RNA-seq raw reads were aligned to TAIR10 genome release, using TopHat version 2.0.9 (44) with default parameters. Differential expressed genes were identified using Cufflinks version 2.2.1, following the workflow with default parameters (45). Differentially expressed genes were those for which relative fold-change values larger than 1.5 and RPKM value larger than 1 were observed (46, 47).

Chromatin-immunoprecipitated DNA was sequenced using an Illumina HiSeq 2000 platform according to standard operating procedures. Initial quality-control analysis was performed using FastQC (48). Single-end 51-bp reads were first mapped to the Arabidopsis genome (TAIR10) (49), using bwa software (version 0.7.1) (50) with default parameters. For each ENAP1-binding analysis, mapped reads were normalized as RPKM in windows of 1 bp, using deepTools (–scaleFactor 0.001) (42, 51), and then were visualized with the Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV) (52). Peaks significantly enriched in ChIP-seq tags were identified using MACS2 (version 2.1.0.20150603; parameter: -p 1e-3) (53). Peaks present in biological replicates were retained as binding regions. Binding regions were merged when the maximum gap between two peaks was less than 200 bp. The relative enrichments of ChIP regions in important genomic features were analyzed by CEAS software (54). We used two methods to evaluate reproducibility of the ChIP-seq data: (i) Normalized extended read counts at each position (read density) in the reference genome for each sample were calculated (55) and (ii) for each ENAP1-binding region, the RPKMs for each sample were calculated as described in ref. 22. R scripts were used to analyze the correlation between samples.

FAIRE-qPCR.

FAIRE-qPCR was conducted according to Wu et al. (56). Briefly, 2 g of etiolated seedlings treated with air or ethylene for 4 h was cross-linked with 1% formaldehyde in cross-linking buffer under vacuum for 8 min. The Actin7 gene was used as the internal control for all FAIRE experiments. qPCR was performed for cross-linked and non–cross-linked FAIRE samples. Fold enrichment was obtained by normalizing to data on samples with uncross-linked DNA. The fold enrichment at each locus was normalized to Actin7. All of the primers for ChIP-qPCR, qPCR, and FAIRE-qPCR are listed in Table S2.

Acknowledgments

We thank S. Sung and his laboratory members for comments, V. Iyer and S. Roux for proofreading, and Natalie Ahn and Nancy Vega for plants and laboratory maintenance. We thank the Salk Institute Genomic Analysis Laboratory for providing seeds. We thank the genomic sequencing and analysis facility of the Institute of Cellular and Molecular Biology at The University of Texas at Austin for RNA-seq and ChIP-seq. We thank V. Iyer for advice on ChIP-seq data analysis. This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (to H.Q.) (NIH-1R01GM115879-01).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: The data reported in this paper have been deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information Sequence Read Archive (NCBI SRA) Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo (accession nos. GSE97288, GSE81200, and GSE83214).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1707937114/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Bailey-Serres J, et al. Making sense of low oxygen sensing. Trends Plant Sci. 2012;17:129–138. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2011.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Achard P, et al. The plant stress hormone ethylene controls floral transition via DELLA-dependent regulation of floral meristem-identity genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:6484–6489. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610717104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ortega-Martínez O, Pernas M, Carol RJ, Dolan L. Ethylene modulates stem cell division in the Arabidopsis thaliana root. Science. 2007;317:507–510. doi: 10.1126/science.1143409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ju C, Chang C. Mechanistic insights in ethylene perception and signal transduction. Plant Physiol. 2015;169:85–95. doi: 10.1104/pp.15.00845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hua J, Meyerowitz EM. Ethylene responses are negatively regulated by a receptor gene family in Arabidopsis thaliana. Cell. 1998;94:261–271. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81425-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang C, Kwok SF, Bleecker AB, Meyerowitz EM. Arabidopsis ethylene-response gene ETR1: Similarity of product to two-component regulators. Science. 1993;262:539–544. doi: 10.1126/science.8211181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hua J, et al. EIN4 and ERS2 are members of the putative ethylene receptor gene family in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 1998;10:1321–1332. doi: 10.1105/tpc.10.8.1321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bleecker AB, Esch JJ, Hall AE, Rodríguez FI, Binder BM. The ethylene-receptor family from Arabidopsis: Structure and function. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1998;353:1405–1412. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1998.0295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hirayama T, et al. RESPONSIVE-TO-ANTAGONIST1, a Menkes/Wilson disease-related copper transporter, is required for ethylene signaling in Arabidopsis. Cell. 1999;97:383–393. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80747-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schaller GE, Ladd AN, Lanahan MB, Spanbauer JM, Bleecker AB. The ethylene response mediator ETR1 from Arabidopsis forms a disulfide-linked dimer. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:12526–12530. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.21.12526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sakai H, et al. ETR2 is an ETR1-like gene involved in ethylene signaling in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:5812–5817. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.10.5812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dong CH, et al. Molecular association of the Arabidopsis ETR1 ethylene receptor and a regulator of ethylene signaling, RTE1. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:40706–40713. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.146605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang Y, Li H, Hutchison CE, Laskey J, Kieber JJ. Biochemical and functional analysis of CTR1, a protein kinase that negatively regulates ethylene signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2003;33:221–233. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2003.01620.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kieber JJ, Rothenberg M, Roman G, Feldmann KA, Ecker JR. CTR1, a negative regulator of the ethylene response pathway in Arabidopsis, encodes a member of the raf family of protein kinases. Cell. 1993;72:427–441. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90119-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bisson MM, Groth G. New paradigm in ethylene signaling: EIN2, the central regulator of the signaling pathway, interacts directly with the upstream receptors. Plant Signal Behav. 2011;6:164–166. doi: 10.4161/psb.6.1.14034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Qiao H, Chang KN, Yazaki J, Ecker JR. Interplay between ethylene, ETP1/ETP2 F-box proteins, and degradation of EIN2 triggers ethylene responses in Arabidopsis. Genes Dev. 2009;23:512–521. doi: 10.1101/gad.1765709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ju C, et al. CTR1 phosphorylates the central regulator EIN2 to control ethylene hormone signaling from the ER membrane to the nucleus in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:19486–19491. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1214848109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Qiao H, et al. Processing and subcellular trafficking of ER-tethered EIN2 control response to ethylene gas. Science. 2012;338:390–393. doi: 10.1126/science.1225974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Merchante C, et al. Gene-specific translation regulation mediated by the hormone-signaling molecule EIN2. Cell. 2015;163:684–697. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.09.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li W, et al. EIN2-directed translational regulation of ethylene signaling in Arabidopsis. Cell. 2015;163:670–683. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.09.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chao Q, et al. Activation of the ethylene gas response pathway in Arabidopsis by the nuclear protein ETHYLENE-INSENSITIVE3 and related proteins. Cell. 1997;89:1133–1144. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80300-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chang KN, et al. Temporal transcriptional response to ethylene gas drives growth hormone cross-regulation in Arabidopsis. eLife. 2013;2:e00675. doi: 10.7554/eLife.00675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang F, et al. EIN2-dependent regulation of acetylation of histone H3K14 and non-canonical histone H3K23 in ethylene signalling. Nat Commun. 2016;7:13018. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang L, et al. Ethylene induces combinatorial effects of histone H3 acetylation in gene expression in Arabidopsis. BMC Genomics. 2017;18:538. doi: 10.1186/s12864-017-3929-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hilton IB, et al. Epigenome editing by a CRISPR-Cas9-based acetyltransferase activates genes from promoters and enhancers. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33:510–517. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yamamuro C, Zhu JK, Yang Z. Epigenetic modifications and plant hormone action. Mol Plant. 2016;9:57–70. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2015.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pandey R, et al. Analysis of histone acetyltransferase and histone deacetylase families of Arabidopsis thaliana suggests functional diversification of chromatin modification among multicellular eukaryotes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:5036–5055. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkf660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu X, et al. Histone acetyltransferases in rice (Oryza sativa L.): Phylogenetic analysis, subcellular localization and expression. BMC Plant Biol. 2012;12:145. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-12-145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhu YX. The epigenetic involvement in plant hormone signaling. Chin Sci Bull. 2010;55:2198–2203. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhou C, Zhang L, Duan J, Miki B, Wu K. HISTONE DEACETYLASE19 is involved in jasmonic acid and ethylene signaling of pathogen response in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2005;17:1196–1204. doi: 10.1105/tpc.104.028514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu K, Zhang L, Zhou C, Yu CW, Chaikam V. HDA6 is required for jasmonate response, senescence and flowering in Arabidopsis. J Exp Bot. 2008;59:225–234. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erm300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhu Z, et al. Derepression of ethylene-stabilized transcription factors (EIN3/EIL1) mediates jasmonate and ethylene signaling synergy in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:12539–12544. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1103959108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen LT, Wu K. Role of histone deacetylases HDA6 and HDA19 in ABA and abiotic stress response. Plant Signal Behav. 2010;5:1318–1320. doi: 10.4161/psb.5.10.13168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang Z, et al. Arabidopsis paired amphipathic helix proteins SNL1 and SNL2 redundantly regulate primary seed dormancy via abscisic acid-ethylene antagonism mediated by histone deacetylation. Plant Cell. 2013;25:149–166. doi: 10.1105/tpc.112.108191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Perrella G, et al. Histone deacetylase complex1 expression level titrates plant growth and abscisic acid sensitivity in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2013;25:3491–3505. doi: 10.1105/tpc.113.114835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee K, Park OS, Jung SJ, Seo PJ. Histone deacetylation-mediated cellular dedifferentiation in Arabidopsis. J Plant Physiol. 2016;191:95–100. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2015.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Colville A, et al. Role of HD2 genes in seed germination and early seedling growth in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Rep. 2011;30:1969–1979. doi: 10.1007/s00299-011-1105-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guo H, Ecker JR. Plant responses to ethylene gas are mediated by SCF(EBF1/EBF2)-dependent proteolysis of EIN3 transcription factor. Cell. 2003;115:667–677. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00969-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xie K, Yang Y. RNA-guided genome editing in plants using a CRISPR-Cas system. Mol Plant. 2013;6:1975–1983. doi: 10.1093/mp/sst119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jinek M, et al. A programmable dual-RNA-guided DNA endonuclease in adaptive bacterial immunity. Science. 2012;337:816–821. doi: 10.1126/science.1225829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pedmale UV, et al. Cryptochromes interact directly with PIFs to control plant growth in limiting blue light. Cell. 2016;164:233–245. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ramirez F, Dundar F, Diehl S, Gruning BA, Manke T. deepTools: A flexible platform for exploring deep-sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:W187–W191. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xing D, Wang Y, Hamilton M, Ben-Hur A, Reddy AS. Transcriptome-wide identification of RNA targets of Arabidopsis SERINE/ARGININE-RICH45 uncovers the unexpected roles of this RNA binding protein in RNA processing. Plant Cell. 2015;27:3294–3308. doi: 10.1105/tpc.15.00641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kim D, et al. TopHat2: Accurate alignment of transcriptomes in the presence of insertions, deletions and gene fusions. Genome Biol. 2013;14:R36. doi: 10.1186/gb-2013-14-4-r36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Trapnell C, et al. Differential gene and transcript expression analysis of RNA-seq experiments with TopHat and Cufflinks. Nat Protoc. 2012;7:562–578. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bai MY, Fan M, Oh E, Wang ZY. A triple helix-loop-helix/basic helix-loop-helix cascade controls cell elongation downstream of multiple hormonal and environmental signaling pathways in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2012;24:4917–4929. doi: 10.1105/tpc.112.105163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang F, et al. Phosphorylation of CBP20 links microRNA to root growth in the ethylene response. PLoS Genet. 2016;12:e1006437. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Andrews S. 2013 FastQC: A quality control tool for high throughput sequence data. Available at www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc. Accessed August 3, 2016.

- 49.Lamesch P, et al. The Arabidopsis Information Resource (TAIR): Improved gene annotation and new tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:D1202–D1210. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ramikie TS, et al. Multiple mechanistically distinct modes of endocannabinoid mobilization at central amygdala glutamatergic synapses. Neuron. 2014;81:1111–1125. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Robinson JT, et al. Integrative genomics viewer. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29:24–26. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang Y, et al. Model-based analysis of ChIP-Seq (MACS) Genome Biol. 2008;9:R137. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-9-r137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shin H, Liu T, Manrai AK, Liu XS. CEAS: Cis-regulatory element annotation system. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2605–2606. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bardet AF, He Q, Zeitlinger J, Stark A. A computational pipeline for comparative ChIP-seq analyses. Nat Protoc. 2011;7:45–61. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2011.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wu M-F, et al. Auxin-regulated chromatin switch directs acquisition of flower primordium founder fate. eLife. 2015;4:e09269. doi: 10.7554/eLife.09269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]