Significance

Nuclear factor-κB (NFκB) transcription factors have been implicated in several major diseases, including inflammatory disorders, viral infections, and cancer. NFκB-inhibiting drugs typically have side effects, possibly due to sustained NFκB suppression. The ability to affect induced, but not basal, NFκB activity could provide therapeutic benefit without associated toxicity. We report that the transcription-regulating kinases CDK8/19 potentiate NFκB activity, including the expression of tumor-promoting proinflammatory cytokines, by enabling the completion of NFκB-initiated transcription. CDK8/19 inhibitors suppress the induction of gene expression by NFκB or other transcription factors, but generally do not affect basal expression of the same genes. The role of CDK8/19 in newly induced transcription identifies these kinases as mediators of transcriptional reprogramming, a key aspect of development, differentiation, and pathological processes.

Keywords: NFκB, CDK8, CDK19, RNA polymerase II, regulation of transcription

Abstract

The nuclear factor-κB (NFκB) family of transcription factors has been implicated in inflammatory disorders, viral infections, and cancer. Most of the drugs that inhibit NFκB show significant side effects, possibly due to sustained NFκB suppression. Drugs affecting induced, but not basal, NFκB activity may have the potential to provide therapeutic benefit without associated toxicity. NFκB activation by stress-inducible cell cycle inhibitor p21 was shown to be mediated by a p21-stimulated transcription-regulating kinase CDK8. CDK8 and its paralog CDK19, associated with the transcriptional Mediator complex, act as coregulators of several transcription factors implicated in cancer; CDK8/19 inhibitors are entering clinical development. Here we show that CDK8/19 inhibition by different small-molecule kinase inhibitors or shRNAs suppresses the elongation of NFκB-induced transcription when such transcription is activated by p21-independent canonical inducers, such as TNFα. On NFκB activation, CDK8/19 are corecruited with NFκB to the promoters of the responsive genes. Inhibition of CDK8/19 kinase activity suppresses the RNA polymerase II C-terminal domain phosphorylation required for transcriptional elongation, in a gene-specific manner. Genes coregulated by CDK8/19 and NFκB include IL8, CXCL1, and CXCL2, which encode tumor-promoting proinflammatory cytokines. Although it suppressed newly induced NFκB-driven transcription, CDK8/19 inhibition in most cases had no effect on the basal expression of NFκB-regulated genes or promoters; the same selective regulation of newly induced transcription was observed with other transcription signals potentiated by CDK8/19. This selective role of CDK8/19 identifies these kinases as mediators of transcriptional reprogramming, a key aspect of development and differentiation as well as pathological processes.

The nuclear factor-κB (NFκB) family of transcription factors, comprising a variety of dimers of NFκB and Rel family proteins, has been implicated in viral infections, inflammation, and cancers (1, 2). NFκB activation in cancers has been linked to tumor cell resistance to apoptosis and necrosis, increased proliferation, angiogenesis, and metastasis. NFκB is transiently activated by a variety of signals, including cytokines (e.g., TNFα and IL1β), chemokines, bacterial and viral products, and free radicals. Most of the inducers activate NFκB through the canonical pathway, which involves phosphorylation of NFκB-binding inhibitory IκB proteins by IκB kinases (IKKs), followed by proteasomal degradation of IκB. NFκB dimers released from IκB inhibition enter the nucleus, where they bind to specific cis-regulatory sequences in the promoters of NFκB-responsive genes, in association with coactivator proteins and RNA polymerase II (Pol II) (1). Certain signals activate NFκB through alternative pathways, mediated by IKK or IκB proteins, such as the noncanonical pathway triggered by lymphotoxin-α that regulates a distinct class of genes.

Numerous clinical and experimental drugs have been identified as NFκB inhibitors (1, 2), with the largest groups of such inhibitors targeting IKK or blocking proteasome activity, thereby suppressing NFκB entry into the nucleus. These NFκB-inhibiting drugs typically have significant side effects, however, possibly due to sustained NFκB suppression (1). Drugs that would specifically affect the induced, but not the basal, NFκB activity may be able to suppress disease-promoting effects of NFκB activation without associated toxicity.

NFκB has been identified as a key factor mediating the induction of transcription of tumor-promoting cytokines and other disease-associated genes by chemotherapy-induced DNA damage (3) or by the damage-inducible cell cycle inhibitor p21 (CDKN1A) (4). Using chemical genomics, we have developed a series of small molecules that suppress the induction of transcription by p21 or by DNA damage; the activities of these compounds include suppression of the induction of an NFκB-dependent consensus promoter by p21. These compounds were identified as selective inhibitors of two closely related cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs), CDK8 and CDK19 (3). CDK8 (universally expressed) and its closely related paralog CDK19 (variably expressed) are alternative subunits of the regulatory CDK module of the transcriptional Mediator complex.

Unlike better-known members of the CDK family, CDK8 and CDK19 do not mediate cell cycle progression (5). A key function of CDK8/19 is phosphorylation of the C-terminal domain (CTD) of RNA Pol II, enabling elongation of the transcription; CDK8/19 exert this activity not globally, but rather only in the context of genes that become activated by transcription-inducing factors (6–8). CDK8/19 regulation is especially pertinent in cancers, where CDK8 positively regulates several cancer-relevant signaling pathways (5), including Wnt/β-catenin (9), the serum response network (6), TGFβ (10), HIF1α (7), and estrogen receptor (8). CDK8 has been identified as an oncogene implicated in colorectal (9), pancreatic (11), and breast (3, 8, 12, 13) cancers and melanomas (14) and associated with the stem cell phenotype (15). CDK8/19 inhibition also has an antiproliferative effect in a subset of leukemias (16, 17). Several groups are currently in the process of developing CDK8/19 inhibitors for cancer therapy applications (18). Although a recent paper reported significant toxicity of two CDK8/19-inhibiting small molecules (19), no toxicity has been reported in animal studies with other CDK8/19 inhibitors, including those used in the present work (3, 8, 16, 17).

The effect of CDK8/19 inhibitors against the induction of NFκB-mediated transcription by p21 has been linked to the ability of p21 to bind CDK8 and stimulate its kinase activity (3). However, CDK8 is also active in the absence of p21, and thus we were interested in exploring whether CDK8/19 inhibition would affect the induction of NFκB transcriptional activity by a p21-independent canonical pathway. Here we report that combining canonical pathway activators with CDK8/19 inhibitors partially suppresses transient NFκB-induced gene expression, but not basal NFκB activity. CDK8/19 inhibition has the strongest effect on induction of the IL8/CXCL1/CXCL2 cytokine family, which reportedly has key roles in chemotherapy-induced tumor-promoting activities (20), similar to those suppressed by CDK8/19 inhibition (3). Coregulation of NFκB by CDK8/19 is exerted by elongation-enabling CTD phosphorylation of Pol II in the context of NFκB-induced genes. These results suggest the potential utility of CDK8 inhibitors in therapeutic situations involving transient NFκB activation.

Results

CDK8/19 Inhibition Suppresses NFκB Activity Induced by the Canonical Pathway.

We have previously reported that a selective small-molecule CDK8/19 inhibitor Senexin A suppresses p21-induced activation of a consensus NFκB-dependent promoter construct driving luciferase expression in HT1080 fibrosarcoma cells (3). In the present study, to determine whether the effect of CDK8/19 inhibitors on these promoters depends on p21, we measured the effect of Senexin A in the same reporter cell line, untreated or treated for 18 h with TNFα, a canonical p21-independent NFκB inducer. As shown in Fig. 1A, Senexin A had no significant effect on basal promoter activity, but inhibited TNFα-induced transcription in a concentration-dependent manner, reducing reporter activity to levels close to those seen in untreated cells. We obtained similar results in IL1R-overexpressing HEK293 cells with NFκB-stimulated E-selectin promoter driving luciferase expression (21, 22), where NFκB was activated by a 4-h treatment with IL1 or TNFα (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Effects of Senexin A (SnxA) on NFκB-dependent promoter activity and NFκB translocation. (A) Effect of Senexin A on GFP expression from NFκB-dependent consensus promoter in HT1080 cells, untreated or treated with TNFα (20 ng/mL, 18 h). The effects of Senexin A on TNFα-induced GFP were statistically significant (P < 0.05) at all concentrations. (B) Effects of Senexin A on luciferase expression from NFκB-dependent E-selectin promoter in HEK293 cells untreated or treated with IL1 (10 ng/mL, 4 h) or TNFα (10 ng/mL, 4 h). Asterisks indicate significant effects of Senexin A (P < 0.05). (C) Effects of TNFα (20 ng/mL, 30 min), on the appearance of p50 and p65 in the nuclear fractions of the HT1080 derivative used in Fig. 1A and in HEK293 cells treated or untreated with Senexin A (5 μM), TPCK (50 μM), or MG115 (20 μM) for 2 h.

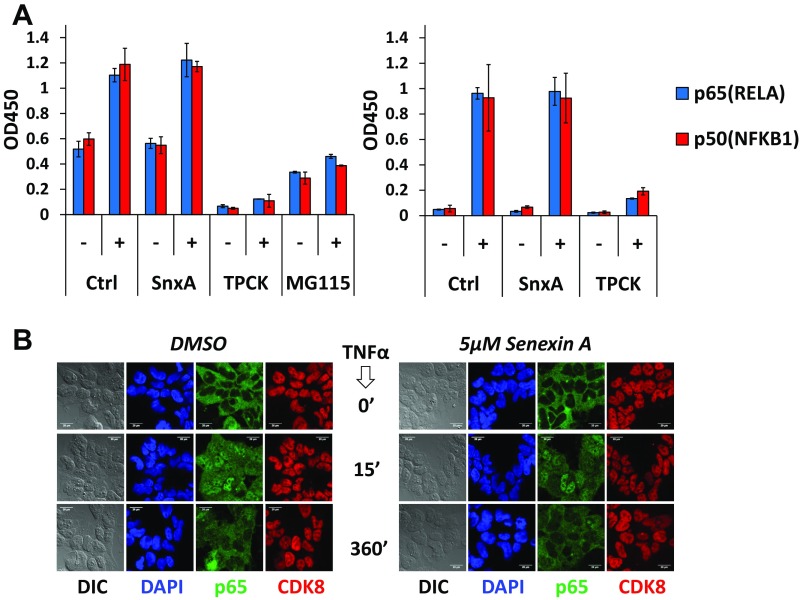

CDK8/19 Inhibition Does Not Prevent Nuclear Translocation of NFκB.

The majority of known NFκB inhibitors affect NFκB degradation in the cytoplasm or its translocation to the nucleus. While CDK8/19 are found only in the nucleus, they regulate the transcription of multiple genes and thus can exert their effects on NFκB either directly in the nucleus or indirectly in the cytoplasm, affecting the nuclear translocation of NFκB. We tested the effects of Senexin A on TNFα-induced nuclear translocation of p65 and p50 in HT1080 and HEK293 cells by isolating the nuclear fraction, followed by immunoblotting. As shown in Fig. 1C, TNFα stimulated the appearance of RELA (p65) and NFKB1 (p50) subunits of NFκB in the nucleus. This effect of TNFα was suppressed by TPCK (tosyl phenylalanyl chloromethyl ketone) and MG115, known to inhibit NFκB in the cytoplasm by acting on IKK or the proteasome (2). In contrast, Senexin A had no effect on TNFα-induced NFκB entry into the nucleus (Fig. 1C). We obtained the same results using an assay measuring the binding of nuclear p65 and p50 to oligonucleotides containing NFκB-binding sites (Fig. S1A) and by immunofluorescence analysis of cellular localization of p65 (Fig. S1B). Since Senexin A does not affect the nuclear translocation of NFκB, these results indicate that the effect of CDK8/19 inhibition on NFκB activity is exerted in the nucleus.

Fig. S1.

Effects of Senexin A on TNFα-induced activation and translocation of NFκB proteins. (A) Effects of TNFα (10 ng/mL), in the absence or presence of 5 µM Senexin A, 50 µM TPCK, and 20 µM MG115, on NFκB site DNA binding of p50 and p65 in the nuclei of HT1080-p21-9-NFκB (Left) and HEK293 (Right) cells (TransAM NFκB assay; Active Motif). (B) Immunofluorescence analysis of the effects of 10 ng/mL TNFα treatment of different durations on the cytoplasm-to-nucleus translocation of p65 in HEK293 cells, in the absence (Left) or presence (Right) of 5 µM Senexin A.

CDK8/19 Inhibition Preferentially Affects NFκB Induction of Cytokines That Show a Strong Early Response to NFκB Activation.

We performed microarray analysis of gene expression in two different sublines of HEK293, treated with TNFα or IL1 and with or without Senexin A, for different times. As shown in Fig. S2 A–C, the genes most strongly induced by TNFα or IL1 at early time points were also the genes most strongly affected by Senexin A. Fig. 2 shows the results of quantitative reverse-transcription PCR (qPCR) analysis of the time course of the induction of 15 genes by TNFα in the absence or presence of Senexin A. The four genes most strongly affected by Senexin A—CXCL1, CXCL2, IL8, and CCL20—encode a family of tumor-promoting cytokines. The effects of Senexin A on the induction of these genes were similar at different concentrations of TNFα (Fig. S3A) and were unaffected by different serum concentrations (Fig. S3B). The effects of TNFα and Senexin A on CXCL1 expression were verified at the protein level by ELISA (Fig. S3C). In contrast to the early-induced genes, genes induced by TNFα at later time points, including IL32 and TNF, were affected by Senexin A only weakly or not at all. As in the promoter assays, Senexin A had no effect on the basal expression of the majority of NFκB-regulated genes; exceptions were EGR1, JUN, and MYC, which are activated by serum factors and only weakly induced by TNFα. These genes were significantly inhibited by Senexin A in the absence of TNFα (Fig. 2).

Fig. S2.

Effects of Senexin A on NFκB-mediated transcription by microarray analysis. (A) Agilent microarray analysis of the effects of 10 ng/mL TNFα and 5 µM Senexin A at different time points (2, 6, 12, and 24 h) on the expression of TNFα-regulated genes in HEK293 cells. (B) Agilent microarray analysis of the effects of 10 ng/mL TNFα and 5 µM Senexin A at 30 min after TNFα stimulation on the expression of the top TNFα-regulated genes in HEK293 cells. (C) Illumina microarray analysis of the effects of 20 ng/mL IL1 and 5 µM Senexin A at 2 h after IL1 stimulation on expression of the top IL1-regulated genes in HEK293-IL1R-pELAM-Luc cells.

Fig. 2.

qPCR analysis of the effects of TNFα and Senexin A on 15 NFκB-regulated genes following treatment with 10 ng/mL TNFα for indicated periods, with or without 5 μM Senexin A (added 2 h before TNFα). Asterisks indicate significant effects of Senexin A (P < 0.05).

Fig. S3.

Effects of CDK8/19 inhibition on NFκB-dependent gene expression. Asterisks denote statistically significant effects of Senexin B (P < 0.05). (A) Effects of different concentrations of TNFα (2-h treatment) in the absence or presence of 1 μM Senexin B on the expression of CXCL1, CXCL2, and NFKBIA in HEK293 cells. (B) Effects of 10 ng/mL TNFα and 1 μM Senexin B on the expression of CXCL1, CXCL2, and IL8 in HEK293 cells in serum-free (SF) media or in the presence of 1% or 10% FBS. (C) Effects of 10 ng/mL TNFα and 1 μM Senexin B on CXCL1 protein expression in conditioned media of HEK293 cells (ELISA).

Both CDK8 and CDK19 Are Involved in NFκB-Induced Transcription.

To verify that the effects of Senexin A are due to CDK8/19 inhibition, we compared the effects of different concentrations of Senexin A, its more potent derivative Senexin B (an early clinical stage drug candidate) (8), and an equipotent analog of a structurally unrelated CDK8/19 kinase inhibitor, Cortistatin A (23), on the expression of CXCL1 and IL8 following the addition of TNFα to HEK293 cells. As shown in Fig. 3A, all of the compounds inhibited the induction of NFκB-responsive cytokines; the compounds’ IC50 values for this effect were proportional to their potency of CDK8/19 inhibition (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3.

Effects of CDK8/19 inhibition by different kinase inhibitors or shRNAs on NFκB-induced transcription. (A) Effects of the CDK8/19 kinase inhibitors Senexin A (SnxA), Senexin B (SnxB), and an equipotent derivative of Cortistatin A (CA) on CXCL1 and IL8 expression in HEK293 cells, pretreated with CDK8/19 inhibitors for 1 h and then treated with 10 ng/mL TNFα for 2 h. (B) Immunoblotting analysis of CDK8 and CDK19 knockdown (KD) in HEK293 derivatives. (C) Effects of TNFα and Senexin A on the mRNA expression of indicated genes in HEK293 cells and their derivatives with single or double knockdown of CDK8 and CDK19, pretreated with or without 5 μM Senexin A for 2 h, followed by 30 min treatment with 10 ng/mL TNFα. Asterisks mark significant effects of Senexin A (P < 0.05). (D) Immunoblotting analysis of CDK8 knockdown in HT1080 subline used in Fig. 1A and its CDK8 knockdown derivative. (E) Effects of TNFα and Senexin A on the expression of the indicated genes in HT1080 cells with or without CDK8 knockdown (the same treatment as in Fig. 3C). Asterisks denote significant effects of Senexin A (P < 0.05).

To determine whether CDK8 and CDK19 have differential effects on NFκB activity, we used shRNA to knock down CDK8, CDK19, or both in HEK293 cells (Fig. 3B). qPCR analysis showed that the knockdown of CDK8 or CDK19 alone partially decreased the induction of CXCL1, CXCL2, and IL8 by TNFα, as well as the effect of Senexin A on this induction, whereas both the induction and the effect of Senexin A were greatly diminished by the knockdown of both CDK8 and CDK19 (Fig. 3C). These results indicate that both CDK8 and CDK19 are involved in NFκB-induced transcription. In contrast to HEK293 cells, which express both CDK8 and CDK19, HT1080 cells express very low levels of CDK19 (3). Partial CDK8 knockdown in an HT1080 derivative was sufficient to decrease the induction of CXCL2 and TNF by TNFα and the effect of Senexin A on this induction (Fig. 3 D and E).

Mechanism of NFκB Coregulation by CDK8/19.

To investigate the mechanism of the effect of CDK8/19 on NFκB-induced transcription, we carried out a series of chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays in HEK293 cells that were untreated or treated with TNFα, Senexin A, or TNFα plus Senexin A. The results of ChIP analysis for NFκB-inducible CXCL1, CXCL2 (strongly CDK8/19-regulated) and NFKBIA (weakly CDK8/19 regulated), as well as for the constitutively expressed housekeeping genes GAPDH and HPRT1, are shown in Fig. 4. As expected, TNFα treatment induced association of the p65 subunit of NFκB to the promoter regions of NFκB-responsive genes, but not of housekeeping genes. p65 recruitment was not affected by Senexin A (Fig. 4A). On TNFα treatment, CDK8/19 [analyzed using an antibody that cross-reacts with both isoforms (24)] was corecruited with p65 to the promoter and the adjacent body regions of NFκB-responsive genes, but not of housekeeping genes. As for p65, the strongest CDK8 recruitment was associated with NFKBIA, confirming that p65 and CDK8/19 were corecruited (Fig. 4B). Senexin A had only a minor effect on the overall TNFα-induced recruitment of CDK8/19 (Fig. 4B). CDK9, a Pol II kinase required for the elongation of transcripts, was also recruited by TNFα treatment to the promoters and downstream regions of NFκB-regulated genes. Senexin A treatment had a small inhibitory effect on CDK9 association with these genes, most notably NFKBIA (Fig. S4A).

Fig. 4.

Mechanism of NFκB coregulation by CDK8/19. HEK293 cells were pretreated with or without 5 μM Senexin A (SnxA) for 2 h, followed by a 30-min treatment with 10 ng/mL TNFα. (A–E) ChIP analysis of the effects of TNFα and Senexin A on binding of p65 (A), CDK8/19 (B), Pol II (C), Pol II phosphorylated at S5 of the CTD (D), and Pol II phosphorylated at S2 of the CTD (E), to three NFκB-regulated and two housekeeping genes. Gene maps are shown at the top. (F) Schematic illustration of the mechanism of NFκB coregulation by CDK8/19.

Fig. S4.

ChIP analysis of the effects of TNFα and Senexin A on binding of CDK9 (A) and H3K9/14Ac (B) to three NFκB-regulated genes and two housekeeping genes. Gene maps are shown at the top.

To analyze histone acetylation, the function of p300/CBP coactivators of NFκB, we conducted a ChIP analysis for H3K9/14Ac. The binding of this acetylated histone to the promoters of CXCL1 and CXCL2 was strong and unaffected by TNFα, but TNFα did increase its association with the NFKBIA promoter. H3K9/14Ac binding was unaffected by Senexin A, indicating that inhibition of CDK8/19 kinase does not affect NFκB coactivator function (Fig. S4B).

Finally, we analyzed the effects of TNFα and Senexin A on the binding of total RNA Pol II (Fig. 4C) and its CTD-phosphorylated forms S5P (which promotes Pol II detachment from the promoter) (Fig. 4D) and S2P (which allows the elongation of transcription) (25) (Fig. 4E). TNFα treatment stimulated the association of all three forms of Pol II with the promoter and the bodies of NFκB-responsive genes, but not of housekeeping genes. Senexin A strongly inhibited the association of the elongation-competent S2P with gene bodies and had a weaker but still significant effect on the binding of S5P and total Pol II. This effect of Senexin B was very pronounced for the strongly CDK8/19-regulated CXCL1 and CXCL2 genes, less prominent for the weakly CDK8/19-regulated NFKBIA gene, and not observed with the housekeeping genes. Hence, the mechanism of the effect of CDK8/19 on NFκB can be described as follows: CDK8/19 are corecruited with NFκB to NFκB-responsive promoters, followed by elongation-enabling phosphorylation of Pol II CTD in an NFκB-inducible gene-specific context (Fig. 4F).

Effects of CDK8/19 on Newly Induced Gene Expression in Different Cell Types.

To compare the impact of CDK8/19 on NFκB-induced transcription in different cell types, we used RNA-Seq to analyze gene expression in HEK293 and HCT116 colon cancer cells that were untreated or treated with TNFα and Senexin B (a more potent derivative of Senexin A), individually and in combination. TNFα affected 71 genes in HEK293 and 201 genes in HCT116 cells [FDR <0.005; fold change (FC) >1.5]; >75% of these genes were induced by TNFα. Fig. 5A compares how these genes are affected by TNFα or by Senexin B in the presence of TNFα. TNFα induction of a subset of these genes was significantly diminished by Senexin B (33% of genes in HEK293 and 13% in HCT116). In both cell lines, the most strongly TNFα-induced genes tended to be those most strongly affected by Senexin B. However, only eight genes (CXCL1, CXCL2, IL8, IER3, SDC4, CD83, NFKBIA, and NFKBIZ) were coregulated by TNFα and Senexin B in both HEK293 and HCT116 cells.

Fig. 5.

Effects of Senexin B (SnxB) on the induction of gene expression by NFκB in different cell lines and by different transcription factors in HEK293. (A) Comparison of the effects of TNFα and Senexin B on the expression of TNFα-regulated genes in HEK293 and HCT116 cells (RNA-Seq data). Cells were pretreated with or without 1 μM Senexin B for 1 h, followed by 2 h treatment with 10 ng/mL TNFα. Red dots indicate genes significantly affected by Senexin B. (B) Effects of TNFα and Senexin B on the expression of CXCL1, CXCL2, and IL8 in HCT116 derivatives control, p21−/−, and p53 −/−, with the same treatment as in A. Asterisks indicate statistically significant effects of Senexin B (P < 0.05). (C) Comparison of the effects of TNFα and Senexin B on the expression of CXCL1, CXCL2, and IL8 in the indicated cell lines. Cells were treated as in A except for LNCAP cells, which were pretreated with 5 μM Senexin B for 1 h, followed by a 30-min treatment with TNFα. Asterisks denote significant effects of Senexin B (P < 0.05). (D) Effects of hypoxia (∼2–3% O2, 24 h) and Senexin B (1 µM) on the expression of a hypoxia-inducible gene in HEK293 cells. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences between hypoxia and hypoxia + SnxB groups (P < 0.05). (E) Effects of IFNγ (250 IU/mL, 5 h) and Senexin B (1 µM) on STAT1 expression in HEK293 cells. Asterisks denote statistically significant effects of Senexin B (P < 0.05).

We asked whether p21, which stimulates CDK8 activity (3), would affect the magnitude of the effect of CDK8/19 inhibitors on NFκB-regulated transcription, using HCT116 derivatives with knockouts of p21 or its upstream regulator p53 (26, 27). As shown in Fig. 5B, the fold induction of CXCL1, CXCL2, and IL8 by TNFα was decreased in cells with p21 or p53 knockout, but the effect of Senexin B on this induction remained the same in all three cell lines, confirming that CDK8/19 act downstream of p21 (Fig. 5B). We also used qPCR to compare the effects of TNFα and Senexin B on CXCL1, CXCL2, and IL8 in 11 tumor and normal human cell lines, all of which induced these three genes on TNFα treatment. The effects of Senexin B were variable; in four cell lines, Senexin B inhibited the induction of all three genes by TNFα (Fig. 5C), but in six cell lines, only IL8 induction was reduced by the CDK8/19 inhibitor, and in one cell line Senexin B augmented rather than inhibited CXCL1 and IL8 expression (Fig. S5). Hence, while CDK8/19 inhibition suppressed NFκB-induced cytokine expression in most of the tested cell lines, these effects of CDK8/19 were highly cell context-dependent.

Fig. S5.

Comparison of the effects of TNFα and Senexin B on the expression of CXCL1, CXCL2, and IL8 in the indicated cell lines. Asterisks denote statistically significant effects of Senexin B (P < 0.05).

Similar variability among different cell lines was previously reported for the effects of CDK8 shRNA on hypoxia-induced HIF1A-mediated transcription (7). We have now tested the effects of hypoxia and Senexin B treatment of HEK293 cells on four genes found in a previous study (7) to be strongly induced by hypoxia and regulated by CDK8 in HCT116. Induction of one of these genes, ANKRD37, was attenuated by Senexin B (Fig. 5D). Notably, the CDK8/19 inhibitor affected only hypoxia-induced, and not basal, ANKRD37 expression, as we also observed for almost all of the TNFα-induced genes and promoters (Figs. 1 A and B, 2, and 5C). We also tested the effect of Senexin B on IFN γ-induced expression of STAT1 in 293 cells and found that Senexin B inhibited only IFN γ-induced, and not basal, expression of this gene (Fig. 5E), confirming the general gene context specificity of the role of CDK8/19.

Discussion

We have found that CDK8/19 inhibition by different small-molecule kinase inhibitors or by shRNA knockdown of both CDK8 and CDK19 inhibits the induction of transcription on NFκB activation. In contrast to almost all known NFκB inhibitors, the effect of CDK8/19 inhibition is not exerted at the level of NFκB stability, nuclear translocation, or binding of NFκB to the responsive promoters. Instead, ChIP analysis revealed that CDK8/19 is corecruited with NFκB to the promoters of NFκB-responsive genes. While CDK8/19 kinase inhibition does not affect the promoter recruitment of CDK8/19, it decreases the elongation-enabling CTD phosphorylation of Pol II at S2 and S5 and suppresses the movement of Pol II along gene bodies. This effect of CDK8/19 inhibition is specific to NFκB-induced genes and was not observed with constitutively expressed genes. The mechanism of NFκB coregulation by CDK8/19, illustrated in Fig. 4F, matches the previously elucidated mechanisms of the effect of CDK8 on the transcription induced by serum (6), HIF1A (7), or estrogen receptor (8), indicating that Pol II CTD phosphorylation in the context of newly activated genes is the most general mechanism of transcriptional coregulation by CDK8/19. It is not the sole mechanism of regulation by CDK8/19, however; other CDK8/19 phosphorylation substrates also have roles in transcription-regulatory effects, such as phosphorylation of SMADs in the TGFβ pathway (10), of E2F1 (which acts as a repressor of β-catenin/TCF transcriptional activity) (28), and of STAT1 in IFNγ-induced transcription (29). Our data do not preclude the possibility that some other CDK8/19 phosphorylation substrates (e.g., STAT1) could complement Pol II CTD phosphorylation in NFκB coregulation by CDK8/19.

In a previous study, we reported that CDK8/19 inhibition suppressed the induction of NFκB-driven transcription by p21 (3). In the present work, we observed this effect of CDK8/19 inhibition when NFκB was induced by the p21-independent canonical pathway inducers, TNFα and IL1, and noted that the effect of CDK8/19 inhibition on TNFα-induced NFκB-mediated transcription was undiminished by p21 knockout. In addition, a recent study reported that siRNA knockdown of both CDK8 and CDK19 in a myeloma cell line decreased the induction of several NFκB-inducible genes by a Toll-like receptor agonist (30). Thus, CDK8/19 potentiate the transcriptional effects of NFκB induced by different signals.

The effects of CDK8/19 on NFκB-regulated genes were preferentially associated with genes showing a strong and early response to NFκB. Remarkably, in several cell lines of epithelial origin, the top CDK8/19-coregulated NFκB targets included a family of related cytokines with tumor-promoting and proinflammatory activities: IL8, CXCL1, and CXCL2. These cytokines, ligands of CXCR1/2 receptors, are known to play key roles in the interactions of tumor cells with various stromal components of the tumor microenvironment (31, 32). In particular, the induction of chemoresistance and metastasis in breast cancer xenografts treated with doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide has been associated with TNFα-induced NFκB-mediated transcription of CXCL1/2 (20). In a previous study, we found that doxorubicin treatment of mice promoted tumor engraftment and drug resistance in lung cancer xenograft models, effects that were suppressed by administration of the CDK8/19 inhibitor Senexin A, and identified IL8 as one of the damage-induced cytokines affected by Senexin A in HCT116 cells (3). In both studies, it appears likely that cytokine induction through cooperation of damage-stimulated NFκB and CDK8/19 might have been responsible for the tumor-promoting effects of chemotherapy.

A survey of various types of tumor and normal cells regarding the effect of CDK8/19 inhibition on the induction of CXCL1, CXCL2, and IL8 by TNFα showed substantial heterogeneity among cell lines, with IL8 showing the most consistent response. Similar heterogeneity was seen in the effect of CDK8 shRNA in suppressing hypoxia-induced transcription of different genes in different cell lines (7); a heterogeneous response to various transcription factors and cofactors is a general feature of transcriptional regulation in eukaryotes. Importantly, CDK8/19 inhibition, while suppressing newly induced NFκB-driven transcription, in most cases had no effect on the ongoing expression of NFκB-regulated genes. The same selective regulation of newly induced but not already active transcription by CDK8/19 inhibition was seen here for IFNγ- and hypoxia-induced gene expression and in our previous study for estrogen receptor-regulated transcription (8). This selective action of CDK8/19 identifies these kinases as mediators of transcriptional reprogramming, a key feature of development and differentiation as well as of pathological processes, most notably cancer. With this unique function, CDK8/19 inhibitors, some of which are now entering clinical trials, provide flexible tools for studying and modulating many important biological and pathological processes.

Materials and Methods

Sources of the reagents and antibodies and descriptions of all procedures are provided in SI Materials and Methods. Cell lines are described in Table S1. Primers used for qPCR analysis are listed in Table S2, and primers used for ChIP analysis are listed in Table S3.

Table S1.

Cell lines

| Cell line | Resource | Cell line origin/description | Culture medium |

| HFFF2 | Sigma-Aldrich; 86031405 | Human fetal foreskin fibroblast | DMEM (high-glucose) + 2 mM glutamine + 10% FBS + 1% penicillin-streptomycin |

| A549 | ATCC; CCL-185 | Human lung carcinoma | DMEM (high-glucose) + 2 mM glutamine + 10% FBS + 1% penicillin-streptomycin |

| HCT 116 | ATCC; CCL-247 | Human colorectal carcinoma | DMEM (high-glucose) + 2 mM glutamine + 10% FBS + 1% penicillin-streptomycin |

| HCT116 p21−/− | (6) | HCT116 derivative with p21 knockout | DMEM (high-glucose) + 2 mM glutamine + 10% FBS + 1% penicillin-streptomycin |

| HCT116 p53−/− | (7) | HCT116 derivative with p53 knockout | DMEM (high-glucose) + 2 mM glutamine + 10% FBS + 1% penicillin-streptomycin |

| MDA-MB-231 | ATCC; HTB-26 | Human breast carcinoma | DMEM (high-glucose) + 2 mM glutamine + 10% FBS + 1% penicillin-streptomycin |

| BJ-EN | (8) | Human normal fibroblasts immortalized by hTERT | DMEM/M199 (4:1) + + 2 mM glutamine + 10% FBS + 1% penicillin-streptomycin + 1 mM sodium pyruvate |

| 293 [HEK-293] | ATCC; CRL-1573 | Human embryonic kidney epithelial cells | DMEM (high-glucose) + 2 mM glutamine + 10% FBS + 1% penicillin-streptomycin |

| RWPE-1 | ATCC; CRL-11609 | Human normal prostate epithelial cell line | Keratinocyte Serum-Free Medium Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific; 17,005-042) |

| LNCaP clone FGC | ATCC; CRL-1740 | Human prostate carcinoma | RPMI-1640 + 2 mM glutamine + 10% FBS + 1% penicillin-streptomycin + 10 mM Hepes + 1 mM sodium pyruvate + 0.15% sodium bicarbonate |

| PC3 | ATCC; CRL-1435 | Human prostate carcinoma | DMEM (high-glucose) + 2 mM glutamine + 10% FBS + 1% penicillin-streptomycin |

| NOMO-1 | Creative Bioarray; CSC-C0550 | Human acute myeloid leukemia | RPMI-1640 + 2 mM glutamine + 10% FBS + 1% penicillin-streptomycin |

| MCF7 | ATCC; HTB-22 | Human breast adenocarcinoma | DMEM (high-glucose) + 2 mM glutamine + 10% FBS + 1% penicillin-streptomycin + 0.01 mg/mL human recombinant insulin + 1 mM sodium pyruvate |

| HT1080-p21-9-NFκB-GFP | (1) | HT1080 derivative with IPTG-inducible p21 and NFκB-inducible GFP reporter | DMEM (high-glucose) + 2 mM glutamine + 10% FBS + 1% penicillin-streptomycin |

| HEK293-IL1R-pELAM-Luc | (2, 3) | HEK293 derivative with IL1R overexpression and firefly luciferase gene under an NFκB-responsive E-Selectin gene promoter | DMEM (high-glucose) + 2 mM glutamine + 10% FBS + 1% penicillin-streptomycin |

ATCC, American Type Culture Collection.

Table S2.

qPCR primer sequences

| Primer | Sequence |

| BIRC3-F | GTCAAATGTTGAAAAAGTGCCA |

| BIRC3-R | CAATGCAGAAGATGAAATAAGGG |

| CCL20-F | GTGCTGCTACTCCACCTCTG |

| CCL20-R | CGTGTGAAGCCCACAATAAA |

| CCL2-F | GCCTCCAGCATGAAAGTCTC |

| CCL2-R | AGGTGACTGGGGCATTGAT |

| CDK19-F | GTTTCACCGTGCATCAAAAGC |

| CDK19-R | ACCCAATTTGCATGGAGGTAATG |

| CDK8-F | AAGTTGGCCGAGGCACTTAT |

| CDK8-R | ATGCCGACATAGAGATCCCA |

| CXCL1-F | GAAAGCTTGCCTCAATCCTG |

| CXCL1-R | AACAGCCACCAGTGAGCTTC |

| CXCL2-F | GGGCAGAAAGCTTGTCTCAA |

| CXCL2-R | GCTTCCTCCTTCCTTCTGGT |

| CXCL3-F | CCATGGTTCAGAAAATCATCG |

| CXCL3-R | TTCAGCTCTGGTAAGGGCAG |

| EGR1-F | AGCCCTACGAGCACCTGAC |

| EGR1-R | AAAGCGGCCAGTATAGGTGA |

| GAPDH-F | CCATCACCATCTTCCAGGAGCG |

| GAPDH-R | AGAGATGATGACCCTTTTGGC |

| HPRT1-F | ACCCTTTCCAAATCCTCAGC |

| HPRT1-R | GTTATGGCGACCCGCAG |

| IL32-F | GCCTTGGCTCCTTGAACTTT |

| IL32-R | CCAACCCCTGAGCAGAAGTA |

| IL8-F | TCCTGATTTCTGCAGCTCTGT |

| IL8-R | AAATTTGGGGTGGAAAGGTT |

| JUN-F | GGAGACAAGTGGCAGAGTCC |

| JUN-R | GTCCTTCTTCTCTTGCGTGG |

| NFKBIA-F | CAGCAGCTCACCGAGGAC |

| NFKBIA-R | AAAGCCAGGTCTCCCTTCAC |

| RPL13A-F | GGCCCAGCAGTACCTGTTTA |

| RPL13A-R | AGATGGCGGAGGTGCAG |

| TNF-F | TCAGCCTCTTCTCCTTCCTG |

| TNF-R | GCCAGAGGGCTGATTAGAGA |

| TNFRSF9-F | TTAAACGGGGCAGAAAGAAA |

| TNFRSF9-R | CTTCTTCTGGAAATCGGCAG |

Table S3.

ChIP primer sequences

| Primer | Sequence | Genomic location (hg38) | Target gene | Target site (relative to TSS) |

| CXCL1-Z-F | GCAGGCGATGCTTCACTACTA | 4 + 73867954 73867974 | CXCL1 | −1,390 |

| CXCL1-Z-R | TACACAGCCCAGCTCAATAGG | 4 − 73868030 73868050 | ||

| CXCL1-A-F | CTCTCAGGTGGTATCTTCAGCG | 4 + 73869092 73869113 | CXCL1 | −247 |

| CXCL1-A-R | TTCAGAGTAACTCCTGTGGACTC | 4 − 73869176 73869198 | ||

| CXCL1-B-F | ACTCGGGATCGATCTGGAACTC | 4 + 73869291 73869312 | CXCL1 | −53 |

| CXCL1-B-R | CTCCGAGATCCGCGAACCC | 4 − 73869369 73869388 | ||

| CXCL1-J-F | CTCCTCTCACAGCCGCCAG | 4 + 73869434 73869453 | CXCL1 | +101 |

| CXCL1-J-R | CTACCAGGAGCAGGAGCAGC | 4 − 73869530 73869549 | ||

| CXCL1-D-F | TATTCCCAATGCCTGGCGTC | 4 + 73870168 73870187 | CXCL1 | +832 |

| CXCL1-D-R | AGCCAGAACCTGTTGCTGTT | 4 − 73870258 73870277 | ||

| CXCL1-E-F | AGTGTTTCTGGCTTAGAACAAAGG | 4 + 73871162 73871185 | CXCL1 | +1,831 |

| CXCL1-E-R | GTAAAGGTAGCCCTTGTTTCCC | 4 − 73871260 73871281 | ||

| CXCL1-G-F | AAATCCTGAGCCCTGGGTAAC | 4 + 73872112 73872132 | CXCL1 | +2,778 |

| CXCL1-G-R | TGACCTCTATTTGCCCAGCTT | 4 − 73872205 73872225 | ||

| CXCL1-M-F | TCCCACTCCCCTCACAATGA | 4 + 73873322 73873341 | CXCL1 | +3,990 |

| CXCL1-M-R | CCCCTTTCCCACACCTCAAT | 4 − 73873420 73873439 | ||

| CXCL2-Z-F | TCCTGGGATTGGTTCCCTCTA | 4 + 74100236 74100256 | CXCL2 | −1,089 |

| CXCL2-Z-R | AAGGCATCAGCTAAACAGGCTT | 4 − 74100313 74100334 | ||

| CXCL2-A-F | AGTTCGGAAGGAAGGCGATG | 4 + 74099294 74099313 | CXCL2 | −146 |

| CXCL2-A-R | CGGGAGTTACGCAAGACAGT | 4 − 74099370 74099389 | ||

| CXCL2-B-F | CTGTGCGAGGAGGAGAGCTG | 4 + 74099146 74099165 | CXCL2 | +3 |

| CXCL2-B-R | CCAGCCCCAACCATGCATAA | 4 − 74099222 74099241 | ||

| CXCL2-J-F | GGGGGACTTCACCTTCACAC | 4 + 74098828 74098847 | CXCL2 | +310 |

| CXCL2-J-R | TCAGCGAGTCTCTTCTTCCC | 4 − 74098926 74098945 | ||

| CXCL2-D-F | ACACTTCAGCACAACTGGCA | 4 + 74098319 74098338 | CXCL2 | +830 |

| CXCL2-D-R | GGTCACCACCCAGGTTCTTC | 4 − 74098394 74098413 | ||

| CXCL2-E-F | TCTCCTGTCCTGTTTCCCCA | 4 + 74097833 74097852 | CXCL2 | +1,306 |

| CXCL2-E-R | CAAGCCTAGAGGTCCTTGCC | 4 − 74097929 74097948 | ||

| CXCL2-F-F | GCAAATATAGTCCTTGTTTCCCCC | 4 + 74096996 74097019 | CXCL2 | +2,142 |

| CXCL2-F-R | GTGTTAGAGCAGAGAGGTTTCG | 4 − 74097091 74097112 | ||

| CXCL2-G-F | TCAGAAGTTTCCACAAGTGAAGT | 4 + 74095965 74095987 | CXCL2 | +3,174 |

| CXCL2-G-R | AGCTGTCAATAAAATGGTGGCT | 4 − 74096058 74096079 | ||

| NFKBIA-Z-F | GGATCGTGAGCCTACTTCTGG | 14 + 35405667 35405687 | NFKBIA | −960 |

| NFKBIA-Z-R | TCCAATCGCGGTTAAGGCAC | 14 − 35405742 35405761 | ||

| NFKBIA-A-F | CACCCTGTAATCCTGTCCCTCTG | 14 + 35405034 35405056 | NFKBIA | −327 |

| NFKBIA-A-R | TTGGGATCTCAGCAGCCGAC | 14 − 35405109 35405128 | ||

| NFKBIA-B-F | GGCGCCCTATAAACGCTG | 14 + 35404770 35404787 | NFKBIA | −66 |

| NFKBIA-B-R | GAGGACGAAGCCAGTTCTC | 14 − 35404851 35404870 | ||

| NFKBIA-C-F | CTGCTGCAGGTTGTTCTGGA | 14 + 35403690 35403709 | NFKBIA | +1,013 |

| NFKBIA-C-R | TGCACTTGGCCATCATCCAT | 14 − 35403774 35403793 | ||

| NFKBIA-E-F | AACACAAACCTTGACAGGTAGT | 14 + 35401601 35401622 | NFKBIA | +3,100 |

| NFKBIA-E-R | GTGCTTCGAGTGACTGACCC | 14 − 35401689 35401708 | ||

| NFKBIA-F-F | ACACTCCTTATATGTGGAAGACCA | 14 + 35400023 35400046 | NFKBIA | +4,682 |

| NFKBIA-F-R | CCCTTTCCTGATCCACAAACGA | 14 − 35400101 35400122 | ||

| GAPDH-E-F | GCCTTTGCCTGAGCAGTCCG | 12 + 6533990 6534009 | GAPDH | −381 |

| GAPDH-E-R | TCCCCTTTCTTTCTTTCAAAGGCTG | 12 − 6534061 6534085 | ||

| GAPDH-B-F | AAGACCTTGGGCTGGGACTG | 12 + 6534410 6534429 | GAPDH | +41 |

| GAPDH-B-R | AGGCTGCGGGCTCAATTTAT | 12 − 6534489 6534508 | ||

| GAPDH-C-F | ATGCTGCATTCGCCCTCTTA | 12 + 6536395 6536414 | GAPDH | +2,036 |

| GAPDH-C-R | GCGCCCAATACGACCAAATC | 12 − 6536493 6536512 | ||

| GAPDH-D-F | GGGCTTGTGTCAAGGTGAGA | 12 + 6538422 6538441 | GAPDH | +3,205 |

| GAPDH-D-R | CGAAGCAAGCAAGGCTGTTT | 12 − 6538498 6538517 | ||

| GAPDH-F-F | CCTCACTCCTTTTGCAGACCA | 12 + 6537567 6537587 | GAPDH | +4,052 |

| GAPDH-F-R | GATGATGTTCTGGAGAGCCCC | 12 − 6537659 6537679 | ||

| HPRT1-A-F | TGGCTAGAGAGAACCGGAGA | X + 134452956 134452975 | HPRT1 | −7,141 |

| HPRT1-A-R | TATGGGGACGCTTTCCAGTG | X − 134453033 134453052 | ||

| HPRT1-B-F | AGGCGAACCTCTCGGCTTT | X + 134460192 134460210 | HPRT1 | +94 |

| HPRT1-B-R | GACTGCTCAGGAGGAGGAAG | X − 134460267 134460286 | ||

| HPRT1-E-F | GAGGAAGCTTTCCCCTCACC | X + 134483582 134483601 | HPRT1 | +23,497 |

| HPRT1-E-R | CCTCCTTGGCTGTCTGGAAC | X − 134483682 134483701 | ||

| HPRT1-F-F | TTAAGTCGGCCTCACCTCCT | X + 134494021 134494040 | HPRT1 | +33,933 |

| HPRT1-F-R | AATGCCACCCCAGAGTTGTT | X − 134494116 134494135 | ||

| HPRT1-G-F | GGTTGGCGGAGCTACAAAAAT | X + 134500851 134500871 | HPRT1 | +40,764 |

| HPRT1-G-R | CAGAATTCCAAAAGAAAGCCGTG | X − 134500946 134500968 |

SI Materials and Methods

Materials.

The origin and culture conditions for the cell lines are shown in Table S1. Cell lines were authenticated by STR profiling by the University of Arizona Genetic Core. TNFα was obtained from GenScript, IFNγ was from ProSpec-Tany, and Senexin A and Senexin B were from Senex Biotechnology. Cortistatin A derivative (16-didehydro-cortistatin A) was a gift of Dr. Phil Baran, The Scripps Research Institute. The reporter cell lines derived from HT1080 (HT1080-p21-9-NFκB-GFP) (3) and from HEK293 (HEK293-IL1R-pELAM-Luc) (21, 22) have been described previously.

For NFκB activation assays, HT1080-p21-9-NFκB-GFP and HEK293 cells were plated in 150-mm or 100-mm plates at 2 × 106 cells/plate. After 24 h, cells were treated with vehicle control (0.1% DMSO), 5 μM Senexin A, 60 μM TPCK, or 20 μM MG-115 for 2 h and then treated with or without 20 ng/mL TNFα for 30 min. Nuclear extracts were prepared with the Nuclear Extract Kit (Active Motif) and used for NFκB analysis by immunoblotting using antibodies CDK8 (sc-1521; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), CDK19 (HPA007053; Sigma-Aldrich), p65/RELA (sc-372; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), NFKB1 (sc-1190; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and PARP (sc-101675; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and secondary antibodies anti-goat (sc-2020; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-rabbit (NA934; GE Healthcare), and anti-mouse (NXA931; GE Healthcare). The same nuclear extracts were analyzed with the TransAM NFκB Family Kit (Active Motif). Immunofluorescence analysis of p65 translocation was carried out by immunofluorescence with the help of the Microscopy and Flow Cytometry Core (MFCC) of the University of South Carolina Center for Targeted Therapeutics using the following antibodies: CDK8 (sc-1521; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and p65/RELA (sc-372; Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

For promoter activity assays, HT1080-p21-9-NFκB-GFP cells were treated with various concentrations of Senexin A, with or without 20 ng/mL TNFα and incubated for 24 h, followed by flow cytometry analysis of GFP fluorescence. HEK293-IL1R-pELAM-Luc cells were treated with IL1 (20 ng/mL for 4 h) and TNFα (10 ng/mL for 4 h) before luciferase measurement.

For gene expression analysis, cells in 12-well plates were first pretreated with Senexin A, Senexin B, or 0.1% DMSO (control) and then treated with or without 10 ng/mL TNFα for different periods. RNA was extracted with the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) and analyzed using qPCR. The qPCR primers used for real-time PCR are listed in Table S2. To quantitate transcriptional effects of different inhibitors, HEK293 cells were plated in 12-well plates at 3 × 105 cells/well. After 24 h, the plates were treated with Senexin A, Senexin B, or Cortistatin A derivative at concentrations of 0–10 μM for 1 h. After this pretreatment, cells were further treated with 10 ng/mL TNFα for 2 h along with the same concentrations of inhibitors. Total RNA was extracted, and mRNA expression of CXCL1 and IL8 was measured by qPCR. The percent inhibition was calculated by normalization to the expression levels in vehicle control samples, and IC50 values were calculated with Prism 6.0 (GraphPad Software).

To evaluate the effects on hypoxia signaling, HEK293 cells were plated in 12-well plates at 1.5 × 105 cells/well and cultured under normal conditions. After 24 h, the plates were treated with 0.1% DMSO (control) or 1 µM Senexin B and cultured under normoxic (21% O2) and hypoxic (∼2–3% O2) conditions for 24 h, followed by RNA extraction and qPCR analysis.

To evaluate the effects on IFNγ signaling, HEK293 cells were plated in 12-well plates at 3 × 105 cells/well. At 24 h after seeding, the plates were treated with 0.1% DMSO (control), 1 µM Senexin B, 250 U/mL IFNγ, or a combination for 5 h, followed by RNA extraction and qPCR.

For the CXCL1 ELISA essay, HEK293 cells were plated in 12-well plates at 3 × 105 cells/well for 24 h. The cells were pretreated with DMSO or 5 μM Senexin A for 1 h and then treated with or without 10 ng/mL TNFα for 4 h or 24 h, followed by the collection of conditioned media. The conditioned media samples were centrifuged at 500 × g for 5 min, and 20 μL of supernatant was analyzed for CXCL1 protein concentration using the Human CXCL1/GROα Quantikine ELISA Kit (R&D Systems).

For microarray analysis, HEK293 cells pretreated with DMSO or 5 μM Senexin A were untreated or treated with 10 ng/mL TNFα for 30 min, 2 h, 6 h, 12 h, or 24 h. Total RNA was extracted as described above, and RNA quality was evaluated on RNA-1000 chip using Bioanalyzer (Agilent). Agilent microarray analyses were conducted by the Functional Genomics Core of the Center for Targeted Therapeutics using SurePrint G3 Human Gene Expression 8 × 60K Microarray Kit Agilent arrays. HEK293-IL1R-pELAM-Luc cells pretreated with DMSO or 5 μM Senexin A were untreated or treated with 20 ng/mL IL1 for 2 h, followed by RNA extraction and Illumina microarray analysis with an Illumina Human Ref-v3 v1 Expression Bead Chip and BeadArray Reader.

For RNA-Seq analysis, HEK293 and HCT116 cells pretreated with either 1 μM Senexin B or 0.1% DMSO for 1 h were untreated or treated with 10 ng/mL TNFα for 2 h, followed by RNA extraction. Libraries for Illumina sequencing were generated using the Illumina TruSeq RNA Sample Prep Kit (RS-122-2001/RS-122-2002) or TruSeq Stranded mRNA Prep Kit (RS-122-2101/RS-122-2102). Samples were run on an Illumina NextSeq 500 sequencer with the NextSeq 500/550 High-Output Kit v2 (FC-404-2002) using 2 × 75-bp reads and a six-cycle index read. Reads were mapped to the hg38 reference genome using STAR (33) with custom settings. featureCounts (34) was used to obtain read counts over annotated genes, and differentially expressed genes were called through analysis in R with the Edge R package (35). The microarray and RNA-Seq data from this study are available in the GEO database (accession SuperSeries GEO101630).

CDK8 and CDK19 knockdown derivatives of HT1080-p21-9-NFκB-GFP and HEK293 were generated by transduction with pLKO.1 lentiviral vectors (Open Biosystems) or pHLB lentiviral vectors (a modified pLKO.1 vector with a blasticidin-resistance gene replacing the puromycin-resistance gene) expressing the corresponding shRNAs, followed by puromycin or blasticidin selection. The target sequence for CDK8 shRNA was CCTCTGGCATATAATCAAGTT. The target sequence for CDK19 shRNA was GCTTGTAGAGAGATTGCACTT. All virus production was performed by the Functional Genomics Core of the Center for Targeted Therapeutics. Target knockdown was verified by qPCR and immunoblotting using the following antibodies: CDK19 (HPA007053; Sigma-Aldrich), p65/RELA (sc-372; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and GAPDH (sc-32233; Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

For ChIP assays, HEK293 cells were treated with 5 μM Senexin A, 10 ng/mL TNFα, or a combination of TNFα and Senexin A. ChIP assays were performed as described previously (8). In brief, cells were fixed with 1% (vol/vol) formaldehyde, harvested for whole-cell lysate preparation, and immunoprecipitation was performed with 2 μg of antibodies against p65/RELA (sc-372; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), CDK8 [sc-1521; Santa Cruz Biotechnology; which immunoprecipitates both CDK8 and CDK19 (24)], CDK9 (sc-484; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), total RNA-Pol II (C152000004; Diagenode), RNA-Pol II-S5P (C152000007; Diagenode), and RNA-Pol II-S2P (C152000005; Diagenode) and ChIP-enriched DNA was analyzed by qPCR with ChIP primers (Table S3).

Statistical Analysis.

The effects of Senexin A, Senexin B, or CDK8/19 shRNAs in different cell culture assays were analyzed using Student’s two-tailed t test (Microsoft Excel). For RNA-Seq analysis, the count data were processed with Edge R package and fitted to a negative binomial with quasi-likelihood variance. Differentially expressed genes were defined by criteria of FDR <0.5% and FC >1.5.

Acknowledgments

We thank Rebecca Rokow-Kittell for assistance with some of the experiments; Dr. Phil Baran for the Cortistatin A analog; Dr. Daping Fan for use of hypoxic chamber; and the Functional Genomics and Microscopy and Flow Cytometry Cores of the University of South Carolina Center for Targeted Therapeutics for assistance with lentiviral transduction, microscopy, and flow cytometry. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant P20 GM 109091 (to E.V.B., M.S.S., and I.B.R.), American Cancer Society Grant IRG-13-043-01, US Department of Defense Grant W81XWH-10-1-0125 (to M.C.), and Susan G. Komen Foundation Postdoctoral Fellowship 15329865 (to M.S.J.M.).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: M.C. and E.V.B. are consultants, D.C.P. is an employee, and I.B.R. is the founder and president of Senex Biotechnology, Inc.

Data deposition: The microarray and RNA-Seq data reported in this paper have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo (accession no. GEO101630).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1710467114/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Zhang Q, Lenardo MJ, Baltimore D. 30 years of NF-κB: A blossoming of relevance to human pathobiology. Cell. 2017;168:37–57. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gupta SC, Sundaram C, Reuter S, Aggarwal BB. Inhibiting NF-κB activation by small molecules as a therapeutic strategy. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1799:775–787. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Porter DC, et al. Cyclin-dependent kinase 8 mediates chemotherapy-induced tumor-promoting paracrine activities. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:13799–13804. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1206906109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Poole JC, Thain A, Perkins ND, Roninson IB. Induction of transcription by p21Waf1/Cip1/Sdi1: Role of NFkappaB and effect of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Cell Cycle. 2004;3:931–940. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Galbraith MD, Donner AJ, Espinosa JM. CDK8: A positive regulator of transcription. Transcription. 2010;1:4–12. doi: 10.4161/trns.1.1.12373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Donner AJ, Ebmeier CC, Taatjes DJ, Espinosa JM. CDK8 is a positive regulator of transcriptional elongation within the serum response network. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17:194–201. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Galbraith MD, et al. HIF1A employs CDK8-Mediator to stimulate RNAPII elongation in response to hypoxia. Cell. 2013;153:1327–1339. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.04.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McDermott MS, et al. Inhibition of CDK8 Mediator kinase suppresses estrogen dependent transcription and the growth of estrogen receptor positive breast cancer. Oncotarget. 2017;8:12558–12575. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.14894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Firestein R, et al. CDK8 is a colorectal cancer oncogene that regulates beta-catenin activity. Nature. 2008;455:547–551. doi: 10.1038/nature07179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alarcón C, et al. Nuclear CDKs drive Smad transcriptional activation and turnover in BMP and TGF-beta pathways. Cell. 2009;139:757–769. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.09.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xu W, et al. Mutated K-ras activates CDK8 to stimulate the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in pancreatic cancer in part via the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. Cancer Lett. 2015;356:613–627. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2014.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Broude EV, et al. Expression of CDK8 and CDK8-interacting genes as potential biomarkers in breast cancer. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2015;15:739–749. doi: 10.2174/156800961508151001105814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xu D, et al. Skp2-macroH2A1-CDK8 axis orchestrates G2/M transition and tumorigenesis. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6641. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kapoor A, et al. The histone variant macroH2A suppresses melanoma progression through regulation of CDK8. Nature. 2010;468:1105–1109. doi: 10.1038/nature09590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Adler AS, et al. CDK8 maintains tumor dedifferentiation and embryonic stem cell pluripotency. Cancer Res. 2012;72:2129–2139. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pelish HE, et al. Mediator kinase inhibition further activates super-enhancer-associated genes in AML. Nature. 2015;526:273–276. doi: 10.1038/nature14904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rzymski T, et al. SEL120-34A is a novel CDK8 inhibitor active in AML cells with high levels of serine phosphorylation of STAT1 and STAT5 transactivation domains. Oncotarget. 2017;8:33779–33795. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.16810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Di Giovanni C, Novellino E, Chilin A, Lavecchia A, Marzaro G. Investigational drugs targeting cyclin-dependent kinases for the treatment of cancer: An update on recent findings (2013-2016) Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2016;25:1215–1230. doi: 10.1080/13543784.2016.1234603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clarke PA, et al. Assessing the mechanism and therapeutic potential of modulators of the human Mediator complex-associated protein kinases. Elife. 2016;5:e20722. doi: 10.7554/eLife.20722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Acharyya S, et al. A CXCL1 paracrine network links cancer chemoresistance and metastasis. Cell. 2012;150:165–178. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.04.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li X, et al. Act1, an NF-kappa B-activating protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:10489–10493. doi: 10.1073/pnas.160265197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lu T, et al. Validation-based insertional mutagenesis identifies lysine demethylase FBXL11 as a negative regulator of NFkappaB. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:16339–16344. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908560106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cee VJ, Chen DY, Lee MR, Nicolaou KC. Cortistatin A is a high-affinity ligand of protein kinases ROCK, CDK8, and CDK11. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2009;48:8952–8957. doi: 10.1002/anie.200904778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tsutsui T, et al. Mediator complex recruits epigenetic regulators via its two cyclin-dependent kinase subunits to repress transcription of immune response genes. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:20955–20965. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.486746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gold MO, Tassan JP, Nigg EA, Rice AP, Herrmann CH. Viral transactivators E1A and VP16 interact with a large complex that is associated with CTD kinase activity and contains CDK8. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:3771–3777. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.19.3771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Waldman T, Lengauer C, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. Uncoupling of S phase and mitosis induced by anticancer agents in cells lacking p21. Nature. 1996;381:713–716. doi: 10.1038/381713a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bunz F, et al. Requirement for p53 and p21 to sustain G2 arrest after DNA damage. Science. 1998;282:1497–1501. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5393.1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhao J, Ramos R, Demma M. CDK8 regulates E2F1 transcriptional activity through S375 phosphorylation. Oncogene. 2013;32:3520–3530. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bancerek J, et al. CDK8 kinase phosphorylates transcription factor STAT1 to selectively regulate the interferon response. Immunity. 2013;38:250–262. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yamamoto S, et al. Mediator cyclin-dependent kinases upregulate transcription of inflammatory genes in cooperation with NF-κB and C/EBPβ on stimulation of Toll-like receptor 9. Genes Cells. 2017;22:265–276. doi: 10.1111/gtc.12475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Palena C, Hamilton DH, Fernando RI. Influence of IL-8 on the epithelial-mesenchymal transition and the tumor microenvironment. Future Oncol. 2012;8:713–722. doi: 10.2217/fon.12.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miyake M, et al. CXCL1-mediated interaction of cancer cells with tumor-associated macrophages and cancer-associated fibroblasts promotes tumor progression in human bladder cancer. Neoplasia. 2016;18:636–646. doi: 10.1016/j.neo.2016.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dobin A, et al. STAR: Ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:15–21. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liao Y, Smyth GK, Shi W. featureCounts: An efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:923–930. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McCarthy DJ, Chen Y, Smyth GK. Differential expression analysis of multifactor RNA-Seq experiments with respect to biological variation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:4288–4297. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]