Significance

Histone H2AK119 ubiquitination (H2Aub), as mediated by Polycomb repressive complex 1 (PRC1), is a prevalent modification which has been linked to gene silencing. We report that remodeling and spacing factor 1 (RSF1), a subunit of the RSF complex, is a H2Aub-binding protein. It reads H2Aub through a previously uncharacterized ubiquitinated H2A binding (UAB) domain. We show that RSF1 is required both for H2Aub-target gene silencing and for maintaining stable nucleosome patterns at promoter regions. The role of RSF1 in H2Aub function is further supported by the observation that RSF1 and Ring1, a Xenopus PRC1 subunit mediating H2Aub, regulate in concert mesodermal cell specification and gastrulation during Xenopus embryogenesis. This study reveals that RSF1 mediates the gene-silencing function of H2Aub.

Keywords: RSF1, H2A ubiquitination, H2Aub binding protein, PRC1, transcription repression

Abstract

Posttranslational histone modifications play important roles in regulating chromatin-based nuclear processes. Histone H2AK119 ubiquitination (H2Aub) is a prevalent modification and has been primarily linked to gene silencing. However, the underlying mechanism remains largely obscure. Here we report the identification of RSF1 (remodeling and spacing factor 1), a subunit of the RSF complex, as a H2Aub binding protein, which mediates the gene-silencing function of this histone modification. RSF1 associates specifically with H2Aub, but not H2Bub nucleosomes, through a previously uncharacterized and obligatory region designated as ubiquitinated H2A binding domain. In human and mouse cells, genes regulated by RSF1 overlap significantly with those controlled by RNF2/Ring1B, the subunit of Polycomb repressive complex 1 (PRC1) which catalyzes the ubiquitination of H2AK119. About 82% of H2Aub-enriched genes, including the classic PRC1 target Hox genes, are bound by RSF1 around their transcription start sites. Depletion of H2Aub levels by Ring1B knockout results in a significant reduction of RSF1 binding. In contrast, RSF1 knockout does not affect RNF2/Ring1B or H2Aub levels but leads to derepression of H2Aub target genes, accompanied by changes in H2Aub chromatin organization and release of linker histone H1. The action of RSF1 in H2Aub-mediated gene silencing is further demonstrated by chromatin-based in vitro transcription. Finally, RSF1 and Ring1 act cooperatively to regulate mesodermal cell specification and gastrulation during Xenopus early embryonic development. Taken together, these data identify RSF1 as a H2Aub reader that contributes to H2Aub-mediated gene silencing by maintaining a stable nucleosome pattern at promoter regions.

In eukaryotic cells, genomic DNA is organized into a chromatin structure by association with histone and nonhistone proteins (1). Posttranslational histone modifications, such as acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation, ubiquitination, and sumoylation, play important roles in modulating chromatin dynamics and in controlling chromatin-based nuclear processes (2, 3). Histone H2A ubiquitination is a prevalent modification, occurring on 10% of total cellular H2A (4). Although ubiquitination has been observed on H2A residues lysine (K) 129 and K15, ubiquitination predominately occurs on H2AK119 (abbreviated as H2Aub) (4–6). We previously reported that Polycomb protein complex 1 (PRC1), a fundamental developmental regulator, acts as the ubiquitin ligase for H2AK119, linking this modification to PRC1-mediated silencing of key developmental genes and the essential roles of PRC1 in cell lineage commitment, stem cell identity, tumorigenesis, and genomic imprinting (7–10). However, the mechanisms of how this modification is recognized and how it elicits downstream effects remain largely unidentified.

Spatially, H2Aub is situated in nucleosomes in the vicinity where linker histone H1 binds. H2Aub slightly facilitates linker histone binding (11), whereas deubiquitination of H2Aub leads to H1 dissociation, accompanied by gene activation (12). H2Aub has also been shown to interfere with the recruitment of FACT (facilitates chromatin transcription), thus blocking transcription elongation (13). In addition, H2Aub blocks the subsequent methylation of H3K4 di- and trimethylation through a novel transhistone code pathway (14). The loss of these gene-activation histone marks is proposed as one of the mechanism leading to transcription repression.

Using nucleosomes assembled with H2A ubiquitinated by PRC1 in vitro, Kalb et al. (15) identified PRC2 and PRC1 as the major factors interacting H2Aub. The interaction with PRC2 may occur through the ubiquitin interacting motif of Jarid2, an auxiliary PRC2 subunit critical for its function in embryonic stem cells (ESCs) (16, 17). The recruitment of PRC2 enhances local H3K27me3, preventing H3K27 acetylation and gene activation (15, 17–19). PRC1 may interact with H2Aub through Rybp, an auxiliary subunit for PRC1 variant (20). Therefore, H2Aub, PRC1, and PRC2 seem to form a feedback control loop to enhance the repressive states of chromatin conformation. However, it remains unclear how they elicit local chromatin conformation changes, leading to gene silencing. Using a ubiquitin affinity column, Richly et al. (21) identified zuotin-related factor (ZRF1) as a H2Aub-binding protein. However, ZRF1 activates rather than represses transcription, and it appears to do so by competitive binding to H2Aub with PRC1, facilitating removal of the H2Aub mark. This latter observation suggests that ZRF1 may function in special circumstances, such as during ESC differentiation.

In this study, by using differential binding to H2A and H2Aub nucleosomes, the stable isotope labeling of amino acids in cell culture (SILAC) technique, and quantitative mass spectrometry, we identified a H2Aub-binding protein, previously identified as the remodeling and spacing factor 1 (RSF1) (22–24). RSF1 is a subunit of the RSF complex, which can remodel the chromatin structure and generate regularly spaced nucleosome arrays (22–24). Our studies show that RSF1 reads H2Aub nucleosomes through a previously uncharacterized region, which we designated as the ubiquitinated H2A binding (UAB) domain. Our studies further demonstrate that RSF1 is required both for H2Aub target gene silencing and for maintaining the stable nucleosome patterns at promoter regions. The role of RSF1 in the PRC1-H2Aub axis is further supported by the observation that RSF1 and Ring1, a Xenopus PRC1 subunit which mediates H2Aub, regulate in concert mesodermal cell specification and gastrulation during Xenopus embryogenesis. Therefore, our studies show that RSF1 plays a critical role in mediating the gene-silencing function of H2Aub.

Results

Identification of RSF1 as a H2Aub Nucleosome-Associated Protein.

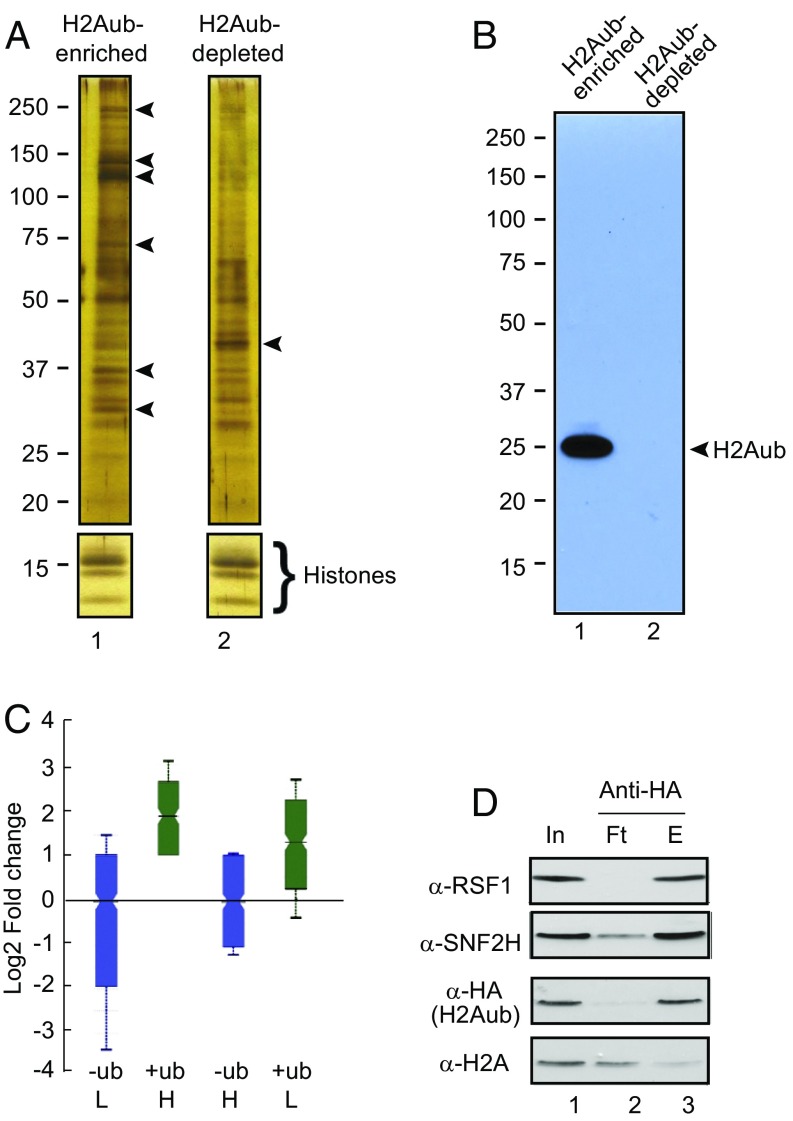

To identify H2Aub binding proteins, we purified ubiquitinated mononucleosomes via anti-HA immunoprecipitation (IP) from a HeLa cell line stably overexpressing HA-tagged ubiquitin (25). Since the level of ubiquitinated H2B (H2Bub) is low (∼0.1%) in mammalian cells, we deemed the IP fraction as H2Aub-enriched nucleosomes; the flow-through (FT) contained low levels of H2Aub from endogenous ubiquitin and was referred as the H2Aub-depleted nucleosomes (Fig. 1A). Equal amounts of H2Aub-enriched and -depleted nucleosomes, as judged by Coomassie brilliant blue (CBB) -stained core histones, were then analyzed by SDS/PAGE and silver staining. Several polypeptides were present only in H2Aub-enriched nucleosomes, whereas only one polypeptide was enriched in H2Aub-depleted nucleosomes (Fig. 1A, arrowheads). Immunoblot with the HA-antibody revealed that only one ubiquitinated polypeptide at the position corresponding to H2Aub. The band was present only in the H2Aub-enriched, but not H2Aub-depleted nucleosomes even after prolonged exposure (Fig. 1B). These results suggest that the other enriched polypeptides associated with H2Aub nucleosomes were not ubiquitinated themselves, but rather represent H2Aub-binding or -interacting proteins.

Fig. 1.

RSF1 preferentially associates with H2Aub-enriched nucleosomes in HeLa cells expressing HA-ubiquitin. (A) Silver staining of a protein gel containing equal amounts of H2Aub-enriched or -depleted mononucleosomes reveals polypeptides enriched specifically within each group of nucleosomes (arrowheads). Different staining times were used for core histones and the rest of the proteins. (B) Anti-HA immunoblot of a protein gel containing an aliquot of the above samples shows that a single protein corresponding to the H2Aub position containing HA-ubiquitin (arrowhead). (C) RSF1 is enriched in the H2Aub-enriched nucleosomes in the SILAC assays, shown by log2-fold enrichment of RSF1 abundance, quantified by the intensity of a RSF1 unique peptide (Fig. S1), in H2Aub-enriched (+ub) or -depleted (−ub) nucleosomes. H and L represent heavy and light lysine labeling, respectively. (D) Immunoblot analyses of proteins contained in the flow-through (Ft) or the eluate (E) of anti-HA IP of H2Aub-containing nucleosomes show that RSF1 is enriched in the H2Aub nucleosomes, along with SNF2H, another component of the RSF complex. In, input. Antibodies used are indicated at the left.

To reveal the identity of these H2Aub-binding proteins, we used the SILAC technique (26). We cultured the stable HA-ubiquitin expressing HeLa cell line in a medium containing 13C labeled l-lysine (termed H, for heavy isotope) and isolated H2Aub-enriched mononucleosomes. We then mixed these nucleosomes with equal amounts of H2Aub-depleted nucleosomes prepared from the same cell line cultured in normal 12C medium (termed L, for light isotope). In parallel, we performed studies using mononucleosomes that were reversely labeled. Mass spectrometry-based quantitative proteomics analysis identified polypeptides that were differentially enriched in H2Aub-enriched or -depleted nucleosomes (Table S1). RSF1 (22–24) and Msx2-interacting protein SPEN (27, 28) were the leading candidates that were significantly enriched in the H2Aub-containing nucleosomes (Table S1). In this study, we focused on the RSF1 protein.

Table S1.

Proteins that are significantly enriched or depleted in H2Aub nucleosomes isolated from HeLa cells overexpressing HA-ubiquitin

| Accession no. | Name | Gene | Log2 (fold-change) | In negative control IP | Mann–Whitney test (Bonferroni corrected) | |||

| H2Aub depleted | H2A enriched | |||||||

| SILAC labeled | Unlabeled | SILAC labeled | Unlabeled | |||||

| P38159 | RNA-binding motif protein, X chromosome | RBMX | −0.0119 | −0.0247 | 2.9391 | 2.464 | Yes | 0.0031 |

| Q96T58 | Msx2-interacting protein | SPEN | 0.2218 | 0.2813 | 3.3034 | 1.9627 | No | 0.032 |

| Q13435 | Splicing factor #B subunit 2 | SF3B2 | 0.0452 | 0.0452 | 1.4797 | 1.9167 | Yes | 0.00015 |

| C9JNJ1 | Remodeling and spacing factor 1 | RSF1 | −0.0021 | 0 | 1.3044 | 1.8278 | No | 0.011 |

| Q13573 | SNW domain-containing protein 1 | SNW1 | −0.1363 | −0.0432 | 1.6406 | 0.7747 | Yes | 0.039 |

| A6NJZ9U | Nucleolar complex protein 3 homolog | NOC3L | 0.0308 | 0.0308 | 0.5244 | 0.7512 | No | 0.00027 |

| Q9NYF8-2 | Bcl-2–associated transcription factor 1 | BCLAF1 | 0.0164 | 0.0164 | 2.579 | 0.6463 | Yes | 0.0015 |

| Q9Y2X3 | Nucleolar protein 58 | NOP58 | −0.0963 | −0.0963 | 0.7584 | 0.3893 | Yes | 0.0086 |

| Q15029 | 116 kDa U5 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein component | EFTUD2 | −0.0149 | −0.0149 | 1.4838 | 0.3651 | Yes | 0.01 |

| P02545 | Prelamin-A/C | LMNA | 0 | 0 | −0.4099 | −0.7106 | — | 0.017 |

| P62701 | 40S ribosomal protein S4, X isoform | RPS4X | 0.0639 | 0.0639 | −0.2305 | −0.9616 | — | 0.0053 |

| Q12906 | Interleukin enhancer-binding factor 3 | ILF3 | 0 | 0 | −1.2755 | −1.2198 | — | 0.012 |

| Q08945 | FACT complex subunit SSRP1 | SSRP1 | −0.0457 | −0.0457 | −0.148 | −1.2864 | — | 0.00024 |

| P62750 | 60S ribosomal protein L23a | RPL23A | 0 | 0 | −0.5037 | −1.2923 | — | 0.0011 |

| P62805 | Histone H4 | HIST1H2A | 0.0287 | 0.0287 | −0.464 | −1.8234 | — | 0.0014 |

| P32969 | 60S ribosomal protein L9 | RPL9 | −0.018 | −0.018 | −2.006 | −2.1686 | — | 0.026 |

| P11387 | DNA topoisomerase 1 | TOP1 | 0 | 0 | −1.124 | −2.4621 | — | 0.012 |

| B4E0E1 | Highly similar to Poly(ADP ribose) polymerase 1 | 0.0182 | 0.0182 | −1.8421 | −2.7885 | — | 0.0011 | |

| P08133 | Annexin A6 | ANXA6 | −0.0323 | −0.0323 | −4.2228 | −5.1433 | — | 0.0081 |

A negative control, where parallel IP experiment was performed with parental cell lines, was included. Proteins that were not immunoprecipitated in negative control are in bold.

Log2 fold-change in RSF1 abundance, as quantified by the intensity of the RSF1 unique fragment (Fig. S1), confirmed that RSF1 level was higher in H2Aub-enriched nucleosomes, independent of the heavy or light lysine label (Fig. 1C). Immunoblot analysis also corroborated that RSF1 was enriched in H2Aub-containing nucleosomes and depleted in the FT of anti-HA IP (Fig. 1D). RSF1 is a subunit of the chromatin remodeling RSF complex, which also contains the SNF2H subunit (22–24). We then examined the distribution of SNF2H. SNF2H was detected at higher levels in H2Aub-enriched nucleosomes, although low levels of SNF2H were also present in the FT fraction (Fig. 1D). These data reveal that RSF1 preferentially associates with H2Aub-enriched nucleosomes and may function together with SNF2H on H2Aub nucleosomes.

Fig. S1.

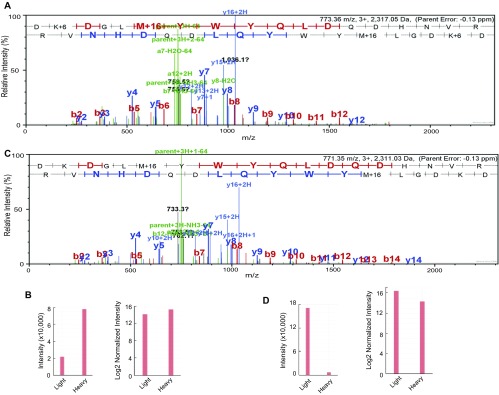

Mass spectrometry quantification of a RSF1 unique peptide in H2Aub-enriched and -depleted nucleosomes. (A) Spectrum of a RSF1 fragment (DKDGLmYWYQLDQDHNVR) in H2Aub-enriched and -depleted nucleosomes. In these experiments, H2Aub-enriched nucleosomes were labeled with heavy lysine and H2Aub-depleted nucleosomes were obtained from cells cultured in light medium. (B) Quantification of the labeled RSF1 fragment intensity from A. Both the intensity and log2-normalized intensity are shown. (C) Spectrum for RSF1 Fragment (DK+6DGLmYWYQLDQDHNVR) in H2Aub-enriched and -depleted nucleosomes. In these experiments, H2Aub-depleted nucleosomes were labeled with heavy lysine and H2Aub-enriched nucleosomes were obtained from cells cultured in light medium. (D) Quantification of the labeled RSF1 fragment intensity from C. Both the intensity and log2-normalized intensity are shown.

RSF1 Binds to H2Aub Nucleosomes Through a Previously Uncharacterized Region in Vitro and in the Cell.

RSF1 is a 1,441-aa protein containing two tandem WHIM domains (amino acids 97–148 and 149–182), a PHD finger (amino acids 893–939), an annotated bromo adjacent homology domain (amino acids 914–968), and a CDC45 domain (amino acids 1,092–1,171) (Fig. 2A). Recombinant proteins of full-length RSF1 and serial fragments were recovered by tandem his- and CL7-affinity purification from bacteria cell extracts (29) (Fig. 2B, Top) and used for an in vitro pull-down assay to determine the physical interaction between RSF1 and H2Aub nucleosomes. While full-length RSF1 pulled down H2Aub nucleosomes, only fragment 7 (amino acids 770–807) was able to do so among all of the fragments tested (Fig. 2B, Middle). We designated the region as the UAB domain.

Fig. 2.

RSF1 binds H2Aub nucleosomes through a previously uncharacterized UAB domain. (A) Schematic representation of the RSF1 domain organization and fragments used in nucleosome pull-down assay. (B) The full-length and fragment 7 (amino acids 770–807) of RSF1 bind to H2Aub nucleosomes. (Top) CBB-stained protein gel containing purified full-length RSF1 and its serial fragments. F1: 1–97 aa; F2, 98–182 aa; F3, 183–397 aa; F4, 398–608 aa; F5, 609–690 aa; F6, 691–785 aa; F7, 770–807 aa; F8, 808–890 aa; F9, 891–941 aa; F10, 942–1,441 aa. (Middle) Pull-down assays show that only the full-length RSF1 and fragment 7 (designated as the UAB domain) bind to H2Aub nucleosomes. (Bottom) Treatment with the H2Aub-specific deubiquitinase USP16 abolishes binding of RSF1 and fragment 7 to the nucleosomes. (C) The UAB domain specifically pulls down reconstituted nucleosomes subjected to in vitro ubiquitination by PRC1 (lane 2), but not unmodified nucleosomes (lane 1). (D) The UAB domain specifically pulls down H2Aub (lane 1), but not H2Bub (lane 2) nucleosomes. (E) The UAB domain is required for RSF1 to interact with H2Aub nucleosomes in 293T cells. Cells were transfected with an empty vector or vectors expressing Flag-RSF1 or mutated Flag-RSF1 (MT) in which the UAB domain was in-frame deleted. Mononucleosomes were prepared and subjected to anti-Flag IP followed by immunoblots. (F) Metaplot of Flag-RSF1 in control (blue line) and Ring1B KO (red line) mouse ESCs. For all data, the minimum value is set to 0. The signal plot is normalized by subtracting IgG ChIP-seq signal from the same cell lines. Transcription start site (TSS) plus 10-kb upstream and transcription termination site (TTS) plus 10-kb downstream are shown. (G) Venn diagram shows the overlap between RSF1 bound genes and H2Aub marked genes in mouse ESCs. About 82% of H2Aub sites are bound by RSF1.

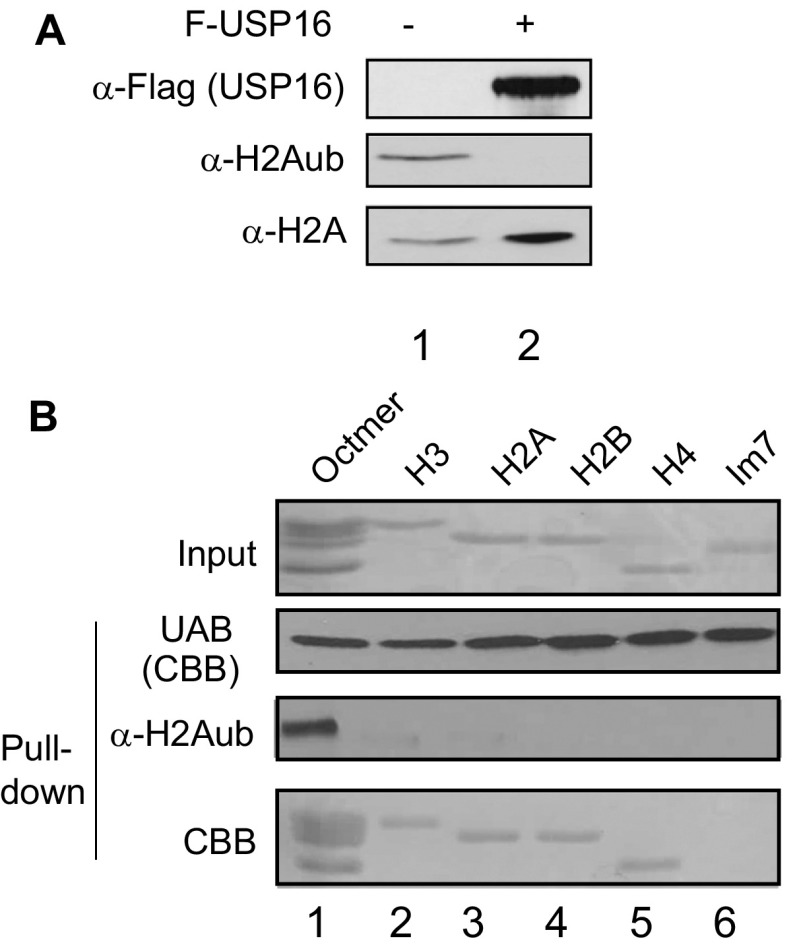

To confirm that H2A ubiquitination in nucleosomes was indeed crucial for RSF1/UAB binding, we incubated H2Aub-containing nucleosomes with recombinant USP16, a histone H2A-specific deubiquitinase that completely removed the ubiquitin moiety from H2Aub in these nucleosomes (25) (Fig. S2A). Treatment with USP16 resulted in failure of RSF1 or UAB to pull down nucleosomes (Fig. 2B, Bottom), despite the presence of other histone modifications (12, 14, 15). This result indicated that H2Aub was required for RSF1/UAB to interact with nucleosomes. Previous studies revealed that RSF1 could interact with histones in vitro, possibly due to the nonspecific electrostatic interaction (23). Our studies confirmed that the UAB domain pulled down each individual core histone but not the unrelated immunity protein 7 (Im7) (Fig. S2B). As UAB pulled down only H2Aub, but not nonubiquitinated nucleosomes, we suggest that the formation of nucleosomes provides the selectivity for RSF1 to interact only with H2Aub nucleosomes.

Fig. S2.

The UAB domain of RSF1 binds to H2Aub nucleosomes specifically. (A) Immunoblots of H2Aub-containing nucleosomes before (lane 1) and after (lane 2) treatment of USP16, a histone H2A specific deubiquitinase (25). Antibodies used are indicated on the left side of the panel. (B) The UAB domain pull-down assays with histone octamer or individual histones as input. The Top panel is a CBB stained gel image containing histone octamer (lane 1, prepared from H2Aub-containing nucleosomes), individual histones (lanes 2–5, purified from E. coli) and an unrelated protein Im7 (lane 6, purified from E. coli). The Bottom three panels show the pull-down proteins, as analyzed by immunoblots (third panel) and CBB staining (second and fourth panels).

Since H2Aub nucleosomes purified by anti-HA IP may contain H2A ubiquitinated at K119 and K129 (4, 6), we further extended the study by using reconstituted nucleosomes that were subjected to in vitro ubiquitination by the PRC1 complex (7, 30). The UAB motif pulled down only nucleosomes treated with PRC1, but not the original reconstituted nucleosomes (Fig. 2C), indicating that the UAB domain indeed interacts with ubiquitinated H2AK119 nucleosomes. In contrast to H2Aub nucleosomes, UAB was unable to pull down ubiquitinated H2B (H2Bub) nucleosomes (prepared from a yeast stain expressing human H2B) (31) (Fig. 2D). These data show that RSF2 interacted specifically with H2Aub nucleosomes.

To determine whether the UAB domain is required for RSF1 to interact with H2Aub nucleosomes in the cell, we prepared mononucleosomes from 293T cells transfected with Flag-tagged RSF1 or a mutated (MT) RSF1 in which the UAB domain was in-frame deleted (Fig. 2E). Anti-Flag IP showed that wild-type, but not the mutant form of RSF1, pulled down H2Aub-containing nucleosomes (Fig. 2E). This result demonstrated an obligatory role of the UAB domain in the interaction between RSF1 and H2Aub nucleosomes in the cell.

Binding Profile of RSF1 Correlates with Those of H2Aub and Ring1B.

Because RSF1 binds to H2Aub nucleosomes, we expect that RSF1 would associate with genes that are marked by H2Aub. We therefore examined the binding profile of RSF1 in mouse ESCs by chromatin IP followed with whole-genome sequencing (ChIP-seq). As commercially available RSF1 antibodies do not work for ChIP-seq, we introduced a Flag-HA dual tag into the C terminus of endogenous RSF1 gene locus using CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing (32). ChIP-seq analyses revealed that RSF1 preferentially bound to transcription start sites (TSSs), regardless of whether IgG was used as controls for ChIP in the same cell lines (Fig. 2F) or the Flag antibody was used as controls for ChIP in parental ESCs (Fig. S3A). RSF1 binding profiles correlated closely to H2Aub marks (33, 34) (Fig. 2F), and also overlapped significantly with that of Ring1B, the subunit of PRC1 which catalyzes H2Aub, and PRC2 which collaborates with PRC1 to repress gene expression (Fig. 2F, Fig. S3B, and Dataset S1). Reduction of H2Aub levels by Ring1B knockout (KO) in mouse ESCs (generated by using the CRISPR/Cas9 system) resulted in a significant decrease in RSF1 binding, suggesting that binding of RSF1 to chromatin, at least partially, depends on H2Aub level (Fig. 2F and Fig. S3A). Strikingly, about 82% of H2Aub sites were bound by RSF1 (Fig. 2G), including the classic PRC1 target genes HoxB8, HoxB7, and HoxC6 (Fig. 3C and Fig. S3C). Interestingly, only about 21% of RSF1 binding sites were marked by H2Aub (Fig. 2G). These results implied that while RSF1 might regulate H2Aub-mediated gene silencing, it also likely has functions independent of H2Aub.

Fig. S3.

RSF1 binding overlaps with RNF2/Ring1B and H2Aub binding. (A) Metaplot of Flag-RSF1 in control (blue line) and Ring1B KO (red line) mouse ESCs. For all data, the minimum value is set to 0. The signal plot is normalized by subtracting Flag ChIP-seq signal from the parental ESC lines. TSS plus 10-kb upstream and TTS plus 10-kb downstream are shown. (B) Venn diagram showing the overlap of binding of RSF1 (blue), Ring1B (teal), and PRC2 (pink) in mouse ESCs. (C) Representative images of HoxB7 and HoxC6 genes with aligned tags from RNA-seq (Top two panels), RSF1 ChIP-seq (third panel), and H2Aub ChIP-seq (fourth panels) in mouse ESCs. Parallel H2A and Flag ChIP were shown as controls. Gene diagrams are shown at the Bottom.

Fig. 3.

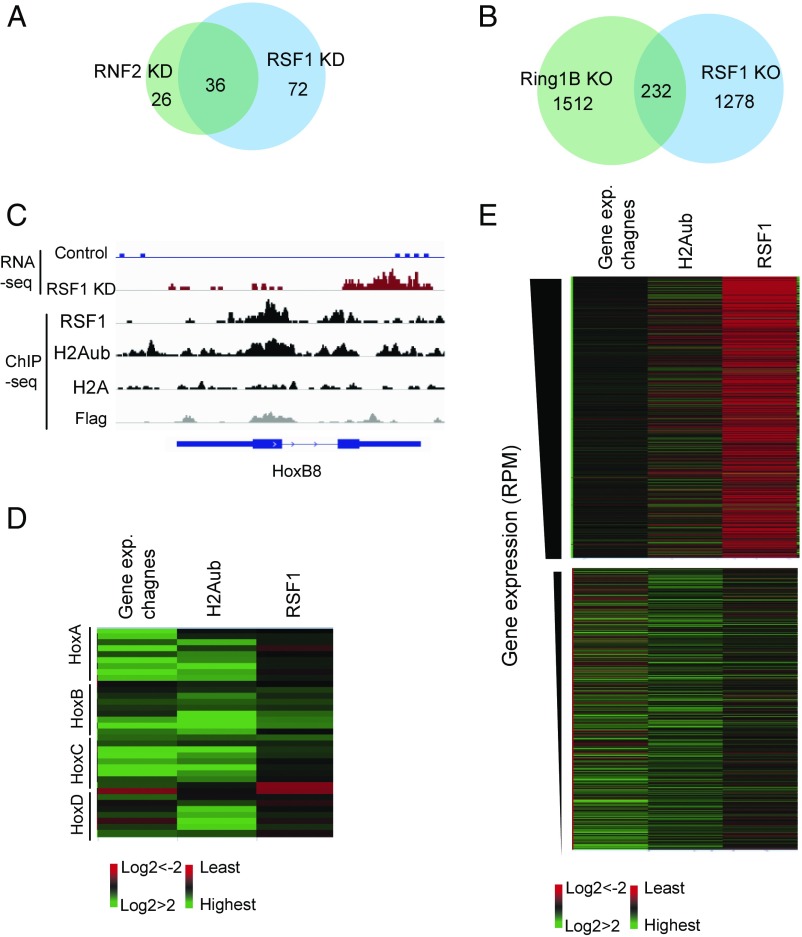

RSF1 and RNF2/Ring1B modulate the expression of a large cohort of common targets in human and mouse cells. (A) Venn diagram shows the overlap of the genes with significant changes in expression in RNF2 or RSF1 KD HeLa cells. (B) Venn diagram shows the overlap of the genes with significant changes in expression in Ring1B or RSF1 KO mouse ESCs. (C) Representative images of the HoxB8 gene locus showing data obtained from the RNA-seq (Top two panels), RSF1 ChIP-seq (third panel), and H2Aub ChIP-seq (fourth panel) assays in mouse ESCs containing RSF1-Flag-HA knockin. Parallel H2A and Flag ChIP in parental ESCs were shown as controls. Gene diagrams are shown (Bottom). (D) Heatmaps shows fold-changes of the expression of the Hox genes in RSF1 KO mouse ESCs compared with control wild-type ESCs from RNA-seq data (first column), tag counts for H2Aub ChIP-seq data (second column), and RSF1 ChIP-seq data (third column) in control wild-type ESCs within 5 kb of gene TSS. The tag counts are RPM-normalized and background-subtracted. (E) Heatmaps shows fold-changes in the expression of all genes in RSF1 KO mouse ESCs compared with wild-type control ESCs from RNA-seq data (first column), tag counts for H2Aub signal (second column), and RSF1 signal (third column) in control wild-type ESCs within 5 kb of gene TSS. Genes are ranked by their expression levels and only the top and bottom 1,000 genes are shown. The tag counts are RPM-normalized and background subtracted.

RSF1 and RNF2/Ring1B Modulate the Expression of a Large Cohort of Common Targets in Human and Mouse Cells.

To determine whether binding of RSF1 to H2Aub nucleosomes mediates H2Aub-associated gene repression (7, 33, 35), we compared changes in gene expression by RNA-sequencing in HeLa cells with siRNA knockdown (KD) of either RSF1 or RNF2, the human homolog of mouse Ring1B, which catalyzes H2Aub. Consistent with previous reports (7, 30), RNF2 KD was associated with a considerable decrease of H2Aub level (Fig. S4A). RSF1 KD affected neither RNF2 nor H2Aub levels (Fig. S4A). Significant changes in expression of 62 and 108 genes were identified in RNF2 KD and RSF1 KD HeLa cells, respectively (Fig. 3A and Dataset S2) (genes selected by q value ≤ 0.05 compared with wild-type). Notably, 36 genes were affected both by RNF2 KD and RSF1 KD. This number represents 58% of genes affected by RNF2 KD and 33.3% of genes affected by RSF1 KD (Fig. 3A). Importantly, virtually all of these genes exhibited changes in expression in the same direction (Fig. S4B). The RNA-seq data were supported by qRT-PCR of selected targets. RNF2 KD resulted in up-regulation of SPP1, DKK1, KCNMA1, FBXO2, SOCS1, KLF2 expression and down-regulation of BMF and GREM1 expression. RSF1 KD resulted in similar changes in the expression of these targets (Fig. S4D). Furthermore, KD of SNF2H—the other component of the chromatin remodeling RSF complex (Fig. S4C)—led to similar changes in expression of these genes (Fig. S4D). The high percentage of overlapping genes affected by RSF1 KD or RNF2 KD indicates that RSF1 or the RSF complex and RNF2 regulate the expression of many common targets and that RSF1 or RSF complex might participate in H2Aub-mediated gene repression.

Fig. S4.

Significant correspondence between RSF1 and RNF2/Ring1B regulated genes. (A) Immunoblot analyses of HeLa cells with KD of RSF1 or RNF2 confirmed the reduction of corresponding target proteins. Antibodies used are indicated on the right of the panels. (B) Waterfall plot showing gene expression changes in RNF2 KD and RSF1 KD HeLa cells. The majority of these genes show changes in the same direction. (C) Immunoblot analyses of control, RSF1, RNF2, and SNF2H KD HeLa cells confirmed the reduction of corresponding target proteins. Antibodies used are indicated on the right of the panels. (D) RT-qPCR analysis of the expression of representative genes in control HeLa cells and in HeLa cells with KD of RSF1, RNF2, and SNF2H. (E) Immunoblots of wild-type, RSF1 KO, or Ring1B KO mouse ESCs confirmed the reduction of corresponding target proteins. Antibodies used are indicated on the right of the panels. (F) Waterfall plot showing gene expression changes in Ring1B KO and in RSF1 KO mouse ESCs. The majority of these genes show changes in the same direction. (G) Venn diagram shows the overlap of H2Aub bound genes with significant changes in expression in Ring1B or RSF1 KO mouse ESCs.

We next extended the study to mouse ESCs. Along with Ring1B KO, we also generated RSF1 KO ESCs by using the CRISPR/Cas9 system (32). As anticipated, Ring1B KO resulted in a dramatic reduction of H2Aub level but did not affect RSF1 level (Fig. S4E). Conversely, RSF1 KO did not affect Ring1B or H2Aub levels (Fig. S4E). RNA-seq analyses revealed that 1,510 genes exhibited significant changes in expression in RSF1 KO mouse ESCs (Fig. 3B and Dataset S3). Based on previous studies (35), we identified 1,744 genes that exhibited significant changes in expression in response to Ring1B KO (Fig. 3B and Dataset S3). Among these genes, 232 were affected both by RSF1 KO and Ring1B KO (Fig. 3B), and 162 of them exhibited changes in the same direction (Fig. S4F). A higher overlapping rate was observed on H2Aub-bound genes: for example, from 15.3 to 25.8% of RSF1 KO affected genes and from 13.3 to 20.6% of Ring1B KO affected genes (Fig. S4G and Dataset S3). The substantial overlap of genes affected by RSF1 KO and Ring1B KO again suggested that RSF1 and Ring1B very likely function in the same pathway to regulate gene expression.

The majority of Hox genes, including the known PRC1 target genes HoxB8, HoxB7, and HoxC6, were marked by H2Aub and repressed in pluripotent mouse ESCs (33, 36). As revealed by RNA-seq, these genes were derepressed after RSF1 KO (Fig. 3 C and D and Fig. S3C). In general, genes with low expression levels also showed high H2Aub levels and substantial RSF1 binding at the TSS, and these genes exhibited significant up-regulation in response to RSF1 KO (Fig. 3E). In contrast, very low levels of H2Aub and RSF1 binding were detected at TSSs of highly expressed genes. These genes did not change their levels of expression in response to RSF1 KO (Fig. 3E). These results support our hypothesis that binding of RSF1 to H2Aub is required for H2Aub-mediated gene silencing.

RSF1 Represses Transcription Activation from H2Aub Chromatin in Vitro.

To substantiate the role of RSF1 in H2Aub target gene repression, we reconstituted a chromatin template containing control H2A or semisynthetic H2Aub (37) (Fig. 4A) and tested the effects of RSF1 on gene activation using an in vitro transcription assay. As shown in Fig. 4B, the naked DNA template and chromatin templates each exhibited transcription stimulation by Gal4-VP16. Chromatin transcription was significantly up-regulated (>10-fold) by the inclusion of acetyl-CoA and p300, a histone acetyltransferase. Inclusion of purified RSF1 with the H2A chromatin template had no effect on this transcription activation. However, inclusion of RSF1 with H2Aub chromatin down-regulated Gal4-VP16/p300-mediated transcription activation dramatically (>8-fold) (Fig. 4B). This experiment provides direct evidence that RSF1 participates in repressing H2Aub target gene activation.

Fig. 4.

RSF1 represses transcription activation from H2Aub nucleosome-containing chromatin in vitro. (A) Supercoiling assay of reconstituted chromatin template. The purified supercoiled plasmids (lane 1) were relaxed to closed circular templates using topoisomerase I (lane 2). After protease digestion and phenol-chloroform extraction, the relaxed plasmids (lane 2) were mixed with histone/ACF/Nap1 in the presence of topoisomerase I to reconstitute chromatin template that restore DNA supercoiling. DNA was then purified and changes in linking number were demonstrated (lanes 3 and 4). (B) In vitro transcription assay on naked DNA and on chromatin templates reconstituted with H2A or semisynthetic H2Aub. GAL4-VP16 and p300/AcCoA activate transcription. RSF1 inhibits transcription activation on H2Aub chromatin template, but has no effect on transcription activation on H2A chromatin.

RSF1 Is Required for Maintaining the Pattern and Stability of H2Aub Nucleosomes at Promoter Regions.

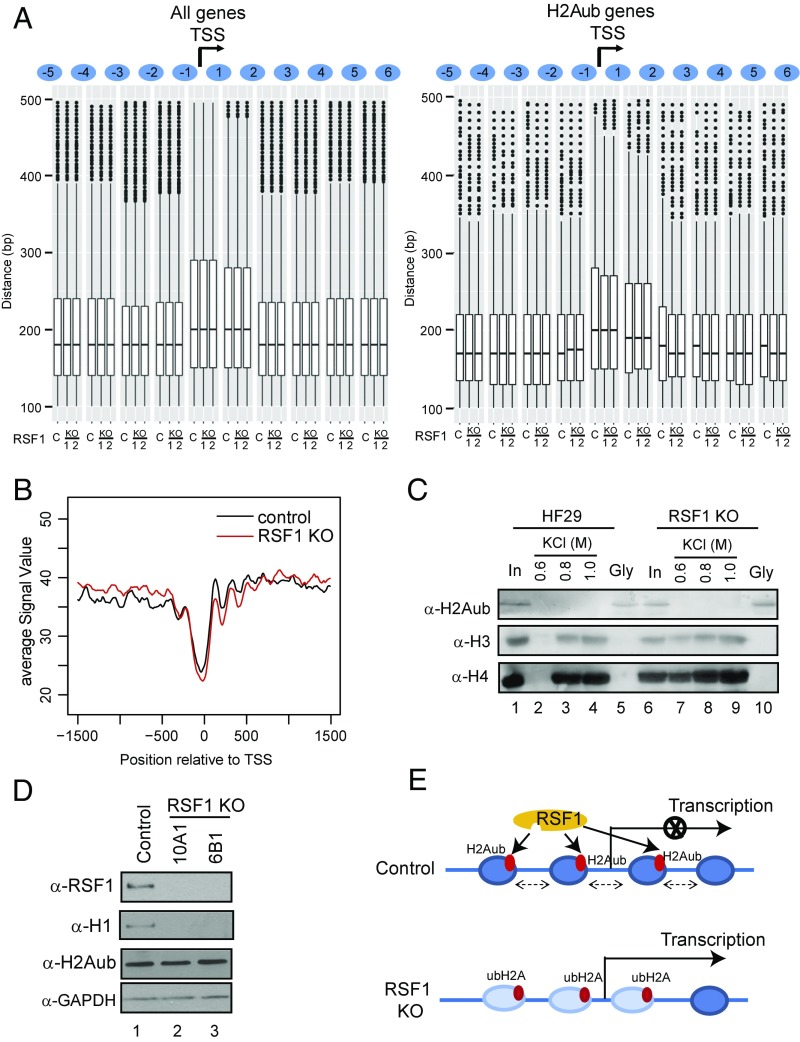

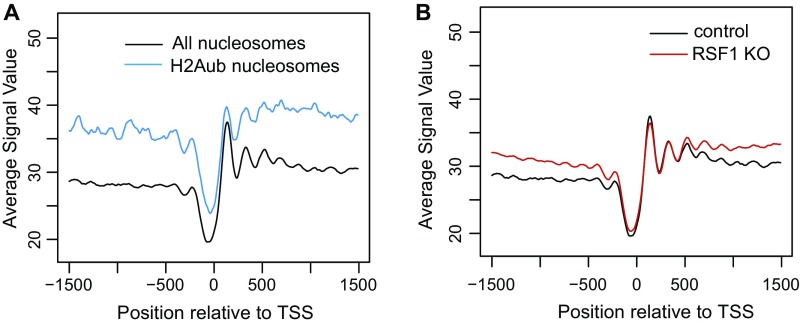

To understand the mechanism by which RSF1 mediates H2Aub target gene silencing, we examined nucleosome organization around the TSS on H2Aub-containing chromatin in control and RSF1 KO mouse ESCs. For comparison, we also determined the organization of nucleosomes for all genes. RSF1 KO did not affect nucleosome array organization for all genes around the TSS (Fig. 5A). However, we found substantial changes of H2Aub nucleosome organization around the TSS upon RSF1 KO (Fig. 5A). Particularly, the spacing of the third, fourth, and sixth nucleosomes were significantly shortened. We inferred that the RSF1 or RSF complex is required for preserving the normal H2Aub nucleosome patterns at promoter regions.

Fig. 5.

RSF1 is required for maintaining the pattern and stability of H2Aub nucleosome arrays at gene promoters. (A) Boxplot of the distance between nucleosomes around TSS in control and two RSF1 KO mouse ESC lines. RSF1 KO affects the organization of H2Aub chromatin around TSS. C, control; 1 and 2, two RSF1 knockout mouse ESCs. (B) Intensity of H2Aub nucleosomes in control (black line) and RSF1 KO (red line) mouse ESCs. (C) H2Aub nucleosomes isolated from control or RSF1 KO HA-ubiquitin-expressing HeLa cells were subjected to increasing concentrations of salt wash. Immunoblot was used to detect the released histones. Gly, glycine elution of the anti-HA beads after 1.0 M salt treatment; HF29, parental HA-ubiquitin overexpressing HeLa cells. Antibodies used are indicated on the left of the panels. (D) RSF1 is required for the binding of linker histone H1 to H2Aub nucleosomes. Immunoblots of H2Aub nucleosomes isolated from control and two independent RSF1 KO HeLa cell lines overexpressing HA-ubiquitin. Antibodies used are indicated on the left of the panels. (E) A proposed model of RSF1 in H2Aub target gene silencing. RSF1 binds to H2Aub nucleosomes to establish and maintain the stable H2Aub nucleosome pattern at promoter regions. The stable nucleosome array leads to a chromatin architecture which is refractory to further remodeling required for H2Aub target gene activation. When RSF1 is knocked out, H2Aub nucleosome patterns are disturbed and nucleosomes become less stable despite the presence of H2Aub. These H2Aub nucleosomes are subjected to chromatin remodeling for gene activation.

The intensity of H2Aub-containing nucleosomes was higher than total nucleosomes (Fig. S5A), suggesting that H2Aub nucleosomes are normally more stable than nonubiquitinated nucleosomes. To determine whether RSF1 contributes to the stability of these H2Aub nucleosomes, we compared the stability of H2Aub nucleosomes in control and RSF1 KO cells. When RSF1 was knocked out, the intensity of H2Aub nucleosomes was reduced dramatically (Fig. 5B), whereas the overall intensity of nucleosomes was not altered (Fig. S5B). This result indicates that RSF1 is required for maintaining the stability of H2Aub nucleosomes. To provide experimental evidence for this observation, we established RSF1 KO lines in HeLa cells that stably overexpress HA-ubiquitin (25). Consistent with our previous RSF1 KD experiments in HeLa cells (Fig. S4 A and C), RSF1 KO did not affect the level of H2Aub in these cells (Fig. 5D). However, H2Aub-containing nucleosomes isolated from RSF1 KO cells by anti-HA IP were less stable than those from the parental HeLa cells, as evidenced by increased H3 and H4 dissociation in lower salt (Fig. 5C). These data indicate that RSF1 indeed contributes to the elevated stability of H2Aub nucleosomes. Linker histone has long been implicated in nucleosome stability and H2Aub target gene repression (11, 12). Interestingly, when H2Aub nucleosomes isolated from the HA-ubiquitin–overexpressing HeLa cells were examined with immunoblots, we found that RSF1 KO resulted in the dissociation of linker histone H1 from H2Aub nucleosomes (Fig. 5D). These results establish RSF1 as a factor which functions downstream of H2Aub but upstream of linker histones to maintain the stability of H2Aub nucleosomes.

Fig. S5.

RSF1 is required for maintaining stable promoter nucleosome arrays. (A) Binding intensity of H2Aub nucleosomes (blue line) and all nucleosomes (black line) in mouse ESCs. (B) Binding intensity of all nucleosomes in control (black line) and RSF1 KO (red line) mouse ESCs.

RSF1 Collaborates with PRC1 Subunit Ring1 to Regulate Mesodermal Specification During Early Xenopus Embryogenesis.

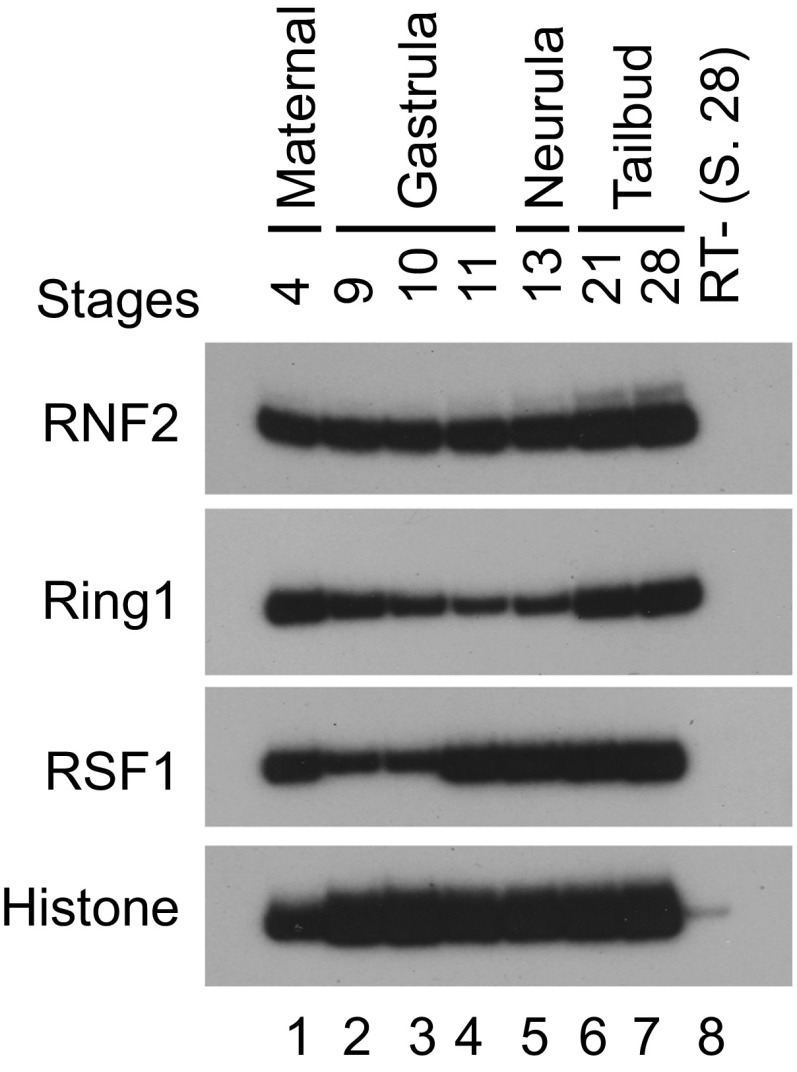

As RSF1 participates in H2Aub-mediated gene repression, we anticipate that RSF1 and PRC1 regulate similar physiological processes. We thus turned to the Xenopus model system to investigate the functions of endogenous RSF1 and PRC1 during early embryogenesis. Xenopus RSF1, and Ring homologs Ring1 and RNF2, were all expressed highly and widely during early developmental stages (Fig. S6). Antisense morpholino oligos (MOs) that blocked mRNA splicing of these genes were used to interfere with the production of these proteins. Injection of either RSF1-MO or Ring1-MO into early frog embryos induced severe gastrulation defects, with tadpoles often displaying shortened body axis and failure in blastopore closure (Fig. 6A). In contrast, injection of RNF2-MO led to a milder phenotype of bent axis and malformation of the head (Fig. 6A). The axial defects induced by KD of Ring1 or RSF1 were MO dose-dependent (Fig. 6B), so that more severe defects were observed with higher doses of the MOs (Fig. 6B). Ring1 and RSF1 seemed to act cooperatively such that a combination of low doses of Ring1-MO and RSF1-MO resulted in an embryonic phenotype that mimicked or surpassed that with the high doses of individual MOs (Fig. 6B). When examined at late gastrula stages, both RSF1 and Ring1 MOs induced a delay in blastopore closure, whereas RNF2 morphant embryos displayed normal blastopore morphology (Fig. 6C). In situ hybridization revealed that the pan-mesodermal marker Brachyury (Bra), the dorsal mesodermal marker Chordin (Chd), and the ventrolateral mesodermal marker (Wnt8) were all reduced in RSF1 and Ring1 morphant embryos, but appeared normal in RNF2 morphant embryos (Fig. 6D). These results reveal that RSF1 acted together with Ring1 to regulate mesodermal cell fate specification during Xenopus gastrulation. The results also suggest that Ring1 might play a more critical role than RNF2 in early Xenopus development. This observation is similar to the situation in mouse and human cells where Ring1B/RNF2 is more critical than Ring1A/Ring1 (7, 35). To support this interpretation, antibodies specific for Xenopus Ring1A/RNF2 will be needed to verify the effectiveness of individual protein KD.

Fig. S6.

RSF1, Ring1, and RNF2, are expressed highly and widely during Xenopus embryonic development. Semiquantitative RT-PCR analyses of RSF1, Ring1, and RNF2 expression in Xenopus larvis at different stages of embryo development.

Fig. 6.

RSF1 collaborates with Ring1 to regulate mesodermal specification during early Xenopus embryogenesis. (A) Both RSF1 and Ring1 regulate Xenopus gastrulation. Injection of RSF1-MO (20 ng) and Ring1-MO (50 ng) induced similar gastrulation defects in Xenopus tadpoles, with embryos displaying short axis and open blastopore. In contrast, RNF2-MO induced a milder phenotype of bent axis and head defects. (B) RSF1-MO and Ring1-MO act cooperatively to induce gastrulation defects. A combination of low doses of Ring1-MO and RSF1-MO resulted in an embryonic phenotype that mimicked or surpassed that with the high doses of individual MOs. (C) At late gastrula stages, RSF1-MO and Ring1-MO cause delay in blastopore closure. Combination of low doses of RSF1-MO and Ring1-MO induced similar gastrulation defects as that when higher doses of individual MOs were used. RNF2-MO did not have obvious effects on blastopore closure. (D) In situ hybridization demonstrated that KD of RSF1 or Ring1 reduced mesodermal markers in a similar fashion. The pan-mesodermal gene Brachyury (Bra), the dorsal mesodermal marker Chordin (Chd), and the ventrolateral mesodermal marker Wnt8 were all reduced upon RSF1 or Ring1 KD. KD of RNF2 did not alter expression of these mesodermal markers. The embryos were injected with the MOs and the lineage tracer encoding nuclear β-Gal into the marginal zone of one cell at the two-cell stage, and the injected region was revealed by staining with the β-Gal substrate Red-Gal.

Discussion

H2Aub is a prevalent histone modification which has been primarily linked to PRC1-mediated gene silencing. Here we identified RSF1 as a binding protein of this modification. The binding region is delineated to a previously uncharacterized region, which we termed the UAB domain. The UAB domain specifically recognizes H2Aub nucleosomes but not H2Bub and nonubiquitinated nucleosomes (Fig. 2). How does the UAB domain specifically recognize the H2Aub nucleosomes? Analyses of the UAB sequence reveals two potential function segments. The central portion of the UAB domain adopts an α-helical conformation and contains two sets of four conserved aliphatic residues that overlapped by two residues (an α-helix has 3.6 residues per turn) facing the same side of the α-helix (Fig. S7). This sequence arrangement resembles the mechanism used by ubiquitin interacting domain to recognize ubiquitinated proteins (38, 39). The N terminus of the UAB domain contains four vertebrate-specific highly conserved arginine residues that can potentially interact with the nucleosome acidic patch through an arginine anchoring mechanism (Fig. S7). Such a sequence feature has been structurally observed in the ubiquitination-dependent recruitment domain of 53BP1 (40, 41) and the Sgf11 subunit of the SAGA complex (42). Therefore, it is likely that the N- and central portion of the UAB domain interacts with H2Aub nucleosomes additively or synergistically, whereas an individual domain would have a much weaker binding affinity. Experimental evidence is needed to support this model. The identification of the UAB domain, which recognizes H2Aub nucleosomes, may lead to the identification of protein readers for other ubiquitinated nucleosomes. It may also provide the foundation for interference of this interaction.

Fig. S7.

The UAB motif harbors features for interaction with H2AK119ub nucleosomes. (A) Sequence alignment of the UAB motif across species. Conserved amino acids are heighted in black or gray. The arginine residues likely involved in binding to the nucleosome acidic patch are marked with asterisks. The two clusters of conserved aliphatic residues potentially binding to the ubiquitin hydrophobic patch are indicated by bracket. (B) A structural modeling of the UAB motif complexed with H2AK119ub nucleosome. The UAB motif is shown in pink. The electrostatic potential of nucleosome core octamer is shown, where blue stands for positive charge and red for negative charge. The side chains of the residues in the ubiquitin hydrophobic patch are shown in spheres, and H2A/H2B ubiquitination sites are indicated with arrows. The distance of the acidic patch to H2BK120 is shorter than that to H2AK119, indicating that the spacing between arginine fingers and aliphatic clusters is important for the preferred binding to H2AK119ub nucleosomes.

Not only RSF1 recognizes H2Aub specifically; it is also required for H2Aub-medaited gene silencing. Genes affected by RSF1 KO or KD overlap significantly with genes affected by Ring1B or RNF2 KO or KD. RSF1 KO in mouse ESCs cause significant changes of H2Aub chromatin organization (Fig. 5 A and B and Fig. S5). The RSF1 complex was initially identified as a factor that initiates transcription together with FACT on chromatin templates (22). Subsequently, the RSF complex is shown to generate regularly spaced nucleosomes from irregularly spaced nucleosomes (23). However, aside from the evidence that RSF1 helps load proteins onto centromeres and at the sites of DNA damage (43–46), the function of RSF1 on chromatin in general remains largely unknown. Our preliminary studies of in vitro transcription revealed that the presence of RSF1 represses transcription activation of H2Aub-containing chromatin, but not chromatin-containing H2A. Furthermore, our studies reveal that the recruitment of RSF1 or the RSF complex to H2Aub nucleosomes results in local compacted structures by incorporating linker histone H1 (Fig. 5D), leading to gene repression. It remains to be determined as to how RSF1 or the RSF1 complex, in coordination with linker histone H1 or additional cellular proteins, remodels H2Aub chromatin conformation to establish stable nucleosome arrays, leading to gene repression. Whether there is a direct causal relationship among nucleosome pattern, nucleosome stability, and H1 binding remains to be determined.

Ubiquitinated H2A is the most abundant ubiquitin conjugate in cells and is produced by the PRC1 ubiquitin ligase activity (7). PRC1 can also compact chromatin by physical association with nucleosome arrays, independent of its H2A ubiquitin ligase activity (47–50). However, in this situation, cells will need many more PRC1 molecules to reach equivalent repressive effects. Therefore, H2Aub provides an efficient way for PRC1 to silence gene expression. Recently, Pengelly et al. (51) generated flies with point mutations either in Sce (the Drosophila homolog of Ring) to abolish its E3 ligase activity or in the H2A ubiquitination site to prevent its ubiquitination. Both the Sce and H2A mutant embryos show overall normal morphology and maintain the repression of Hox genes; however, their development is arrested at the end of embryogenesis, suggesting that H2A ubiquitination by PRC1 may be required for late, but not early, embryogenesis. Alternatively, other epigenetic mechanisms may compensate for the function of H2A ubiquitination (see below).

In mouse ESCs, H2Aub appears to be critical for repression of Hox and other PRC1 target genes and for the maintenance of ESC identity, as Ring1B defective of E3 ligase activity cannot rescue ESCs with double KO of Ring1A /Ring1B, two mouse homologs of Drosophila Sce (35). Furthermore, expression of this mutant form of Ring1B results in redistribution of Ring1B and H3K27me3 into gene bodies, while reducing their signals around the promoter regions. This mutation does not change early gene expression and helps sustain embryonic development into E15.5, five days longer than Ring1B KO mice that die at E10.5. However, the Ring1B mutant embryos cannot develop to term and show edema and exencephaly (52). These results thus imply maintenance of gene silencing in the absence of H2Aub may result from a distinct mechanism that employs H3K27me3 in the gene body. Such mechanism may not be precise or efficient for sustaining a proper regulation of gene expression, leading to embryonic lethality during mouse development.

Our studies here reveal an important role of RSF1 as a reader of H2Aub and show that both PRC1 and RSF1 are required to repress a large body of common targets in mouse ESCs (Fig. 3B). In Xenopus, KD of RSF1, Ring1, or both affects embryogenesis. These two proteins cooperate to regulate gastrulation and mesodermal cell specification (Fig. 6). These studies, together with studies on the H2A ubiquitin ligase and deubiquitinase, establish the important role of H2A ubiquitination in PRC1-mediated repression in higher metazoans and argue the importance of RSF1 in the PRC1–H2Aub axis (7, 25, 34, 53).

In conclusion, based on the biochemical, chromatin structure, gene-expression regulation, and embryological studies, we propose a model for RSF1 in histone H2Aub-mediated gene silencing (Fig. 5E). RSF1 binds to H2Aub nucleosomes to organize stable nucleosome patterns around TSSs. This results in a chromatin conformation that is refractory to nucleosome remodeling, thereby leading to repression of H2Aub target gene expression.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture.

HeLa cell lines stably overexpressing HA-ubiquitin was cultured as described previously (25). Briefly, cells were cultured in DMEM (HyClone) supplemented with 10% FBS (HyClone) and 1% ampicillin-streptomycin (HyClone). SILAC labeling was performed as per the manufacturer’s instructions (Cat#: MS10031; Invitrogen). Briefly, cells were grown in DMEM culture media containing heavy isotope (13C) -labeled lysine for six cell doublings to ensure >95% 13C incorporation. The yeast strain expressing human H2B was cultured in Trp minus medium at 30 °C with gentle shaking until OD600 reach 0.5 (31). Mouse ESCs were cultured in DMEM (high glucose, MT-10-013; Gibco) supplemented with 50 unit/mL penicillin and streptomycin (15070-063; Life technologies), 15% murine ESC defined FBS (SH30070.03E; Thermo Scientific), 2 mM l-glutamine (25-005-CI; Cellgro), 1 mM sodium pyruvate (11360-070; Gibco), 1× nonessential amino acids (25-025-CI, 100× stock; Cellgro), 1× nucleoside (ES-008-D, 100× stock; Millipore), 0.007% β-mercaptoethanol (O3446I; Fisher), and 1,000 unit/mL mLIF (ESGRO; Millipore) on irradiated mouse embryonic fibroblasts (PMEF-NL; Millipore) or 0.1% gelatin-coated plates (34).

Chromatin Reconstitution and in Vitro Transcription Assay.

The pG5ML plasmid containing Gal4 binding sites upstream of the adenovirus major late promoter fused to a G-less cassette was used for chromatin assembly. A standard assembly reaction contained relaxed plasmid DNA (0.35 µg), recombinant histones (0.32 µg), recombinant ATP-using chromatin assembly and remodeling factor (ACF, 60 ng), recombinant NAP1 (2 µg), and topoisomerase I (2 ng). To demonstrate successful nucleosome reconstitution, supercoiling assays were performed. The products of assembly reactions were deproteinized and analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis and subsequent ethidium bromide staining (54). Transcription assays were performed using Gal4-VP16 (20 ng), p300 (20 ng), and acetyl-CoA (10 µM), as reported previously (54), except that RSF1 purified from Escherichia coli (Fig. 2B) was added together with Gal4-VP16. Radiolabeled RNA product was phenol-chloroform–extracted, ethanol-precipitated, analyzed by 5% UREA-PAGE, and visualized by autoradiography. Quantification was conducted by phosphorImager analysis.

Xenopus Manipulation.

Xenopus embryos were obtained as described previously (25). Splicing-blocking antisense MOs were injected into both cells of two-cell stage embryos at 20- to 50-ng doses, as indicated in the figures. The morphology of the resulting embryos was observed at gastrula and tadpole stages. For in situ hybridization, 20–25 ng of MOs was coinjected with 0.2 ng RNA encoding the lineage tracer nuclear β-galactosidase (β-Gal) into the marginal zone of one cell of two-cell–stage embryos. The embryos were collected at gastrula stages, stained with the β-Gal substrate Red-Gal, and subjected to in situ hybridization, as described. The sequences of the MOs are as the following: RSF1-MO: CCTCCTCACCTGCCCCGGTCTCTTC; Ring1-MO: ATGCCCAGAAAAACACTGACCCACT; and RNF2-MO: GATTTACCTGTGGTGTCCTCTGCAG. All animal protocols adhere to the National Institutes of Health Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (55) and were approved by the University of Alabama Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Methods for Nucleosome isolation and reconstitution, Mass spectrometry identification and analysis, RSF1 expression and nucleosome pull-down assay, KD, KO, and knockin experiments, RNA-seq, ChIP-seq and data analyses, and nucleosome mapping can be found in SI Materials and Methods.

SI Materials and Methods

Nucleosome Isolation and Reconstitution.

To isolate H2Aub nucleosomes, HeLa cells stably overexpressing HA-ubiquitin were trypsinized and washed twice with PBS containing 1 g MgCl2/L. Cell pellets were resuspended in Buffer A (0.25 M sucrose, 60 mM KCl, 10 mM NaCl, 15 mM Mes pH 6.5, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM CaCl2, 0.5% Triton X-100, 1 mM DTT, 0.2 mM PMSF, 0.5 μg/mL leupeptin, 0.7 μg/mL pepstatin, and 1 μg/mL aprotinin) and incubated on ice for 15 min. Nuclei were collected by centrifugation at 3,600 rpm (Eppendorf Centrifuge 5415D) for 10 min and washed once with TNM Buffer (10 mM Tris⋅HCl pH 8.0, 10 mM NaCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 0.3 M Sucrose, 1 mM DTT, 0.2 mM PMSF, 0.5 μg/mL leupeptin, 0.7 μg/mL pepstatin, 1 μg/mL aprotinin) containing 5 mM CaCl2 (final). Five-microliters micrococcal nuclease (200 U/μL) was added to nuclei suspension and incubated at 37 °C for 20 min to give a complete digestion. After incubation, digested nuclei were collected by centrifuging at 3,600 rpm (Eppendorf Centrifuge 5415D) for 10 min and resuspended in nucleosome extraction buffer (20 mM Tris⋅HCl pH 7.9, 10 mM EDTA, 0.5 M NaCl). After incubation on ice for 10 min, nuclei were centrifuged at 13,200 rpm (Eppendorf Centrifuge 5415D) for 10 min. The supernatant contains mononucleosomes. After dialysis against histone storage buffer (10 mM Hepes-KOH pH 7.5, 1 mM EDTA, 10 mM KCl, 10% glycerol, 0.2 mM PMSF), these nucleosomes were subjected to anti-HA IP following a standard protocol (25). IP nucleosomes were eluted by HA peptide (5 μg/mL) and saved as H2Aub-enriched nucleosomes. Flow-through from the anti-HA IP was saved as H2Aub-depleted nucleosomes. Core histones were obtained from purified nucleosomes by a small scale hydroxyapatite column as described previously (25, 56). In vitro deubiquitination assay with recombinant USP16 was performed as previously described (25).

To isolate H2Bub or H2B nucleosomes, the yeast strain expressing Flag-human H2B were cultured to OD600 0.3–0.5 or stationary phase (31, 56, 57). Frozen yeast pellet was resuspended in 1× HC buffer (150 mM Hepes-KOH pH 7.6, 1 mM EDTA, 250 mM KCl, 10% glycerol, 1 mM DTT, protease inhibitors) and lysed using Fast Prep bead beater. The supernatant was then sonicated to produce mononucleosomes. After centrifugation at 13,200 rpm (Eppendorf Centrifuge 5415D) for 10 min, the supernatant was then incubated with anti-Flag M2 beads (Sigma) preequilibrated with 1× HC buffer at 4 °C for 3 h. Beads were then washed with 1× HC buffer three times and nucleosomes were eluted with 0.5 μg/μL FLAG peptide in 1× HC buffer.

For nucleosome reconstitution, recombinant H3, H4, H2A, and H2B were purified from Escherichia coli as described previously (58). The 5s DNA fragments were PCR-amplified from the XP-10 plasmid (provided by Jeffrey J. Hayes, University of Rochester Medical Center, Rochester, NY) (25, 59). Histone octamer refolding and nucleosome reconstitution were performed as described previously (25, 59). Reconstituted nucleosomes were subjected to in vitro ubiquitination by reconstituted PRC1 complex as described in previous publications (7, 30).

Mass Spectrometry Identification and Analysis.

As judged by CBB staining, equal amounts of heavy (13C labeled) H2Aub-enriched nucleosomes and light H2Aub-depleted nucleosomes, were mixed together and loaded onto a 15% SDS/PAGE gel. In parallel, equal amounts of light H2Aub-enriched nucleosomes and heavy (13C labeled) H2Aub-depleted nucleosomes were also mixed and loaded to a 15% SDS/PAGE gel. Proteins were run ≈1 cm into the resolving gel and stained with CBB to visualize proteins. The protein-containing regions of the gel were excised with a sterile scalpel and cut into 1-mm × 1-mm pieces. In-gel tryptic digestions were performed as described previously (60). Briefly, gel pieces were destained, reduced with 10 mM DTT at 37 °C for 45 min, alkylated with 50 mM iodoacetamide at 37 °C for 45 min, and digested with trypsin overnight at 37 °C. Peptides were extracted from the gel using 50% acetonitrile and concentrated in a speed vacuum. Tryptic digests were loaded onto a 100-μm diameter, 11-cm pulled tip column packed with Jupiter 5 μm C18 reversed-phase beads (Phenomenex) using a Micro AS autosampler and LC nanopump (Eksigent). An acetonitrile gradient in 0.1% formic acid was run from 5 to 40% over 50 min at a flow rate of 650 nL/min. The eluting peptides were analyzed by CID fragmentation on a linear ion trap-Fourier transform-ion cyclotron resonance (LTQ FT-ICR). The LTQ FT-ICR parameters were set as described previously (60). Fully tryptic human peptides were identified using MASCOT 2.2 (Matrix Biosciences), algorithms with a parent ion mass accuracy of 10.0 ppm from the Uniref 100 database (06/2009) and MaxQuant (61). SILAC quantification was performed in MaxQuant. Max Quant results were subsequently normalized to core histone abundance and log2 (fold-change) in protein abundance in heavy and light samples was calculated to identify potential H2Aub associated proteins. In addition, MaxQuant Precursor Intensity results were loaded into the Scaffold Q+S program and SILAC quantification was performed. The list of enriched proteins was counter screened against a list of proteins identified by mass spectrometry in a control anti-HA immunoprecipitation performed in an untagged HeLa cell line.

RSF1 Expression and Nucleosome Pulldown Assay.

To clone RSF1 for expression in E. coli, the whole sequence of human RSF1 was optimized for E. coli codon. Then the whole sequence was divided into five fragments (each with around 950 bp, being separated by the restrictive sites of the RSF1 sequence) and synthesized individually by IDT. Fragments 1 and 3 have T7 promoter primer at the beginning. Fragments 2 and 4 have T7 terminator primer at the end. Fragments 1 and 2 have overlapped sequences and were ligated using fusion PCR. The PCR product (designated as insert I) was cloned into pUC57 by EcoRI and SphI. Fragments 3 and 4 were cloned similarly and designated as insert II. Fragment 5 was cloned directly into pUC57 and designated as insert III. Then insert I was cut out from pUC57 with HindIII and PstI, insert II was cut out with PstI and BsrGI, insert III was cut out with BsrGI and SpeI, respectively. These digested fragments were ligated with pET28a-1TT-F1 which was digested with HindIII and SpeI. This vector was fused a CL7 affinity tag in-frame with the protein of interest for purification purposes, as described previously (29). The cloned RSF1 was subsequently verified by sequencing. To express RSF1 fragments, PCR was performed to obtain the DNAs corresponding to the sequence of the truncated RSF1 from full length RSF1. The PCR products were cloned into pET28a-1TT-F1 using restriction enzymes HindIII and SpeI. All of the truncated fragments were sequenced for verification. The expression and purification was conducted as previously described (29). The purity of RSF1 and fragments was confirmed by SDS/PAGE followed by CBB staining.

For pull-down assays, the Im7 bound recombinant RSF1 protein or fragments were incubated with nucleosomes, histone octamer, or recombinant histones at 4 °C for overnight. The beads were then washed as follows: BC50 twice, BC500 twice, and BC50 twice. The bound proteins were eluted by SDS/PAGE sample loading buffer, heated at 95 °C for 5 min, and resolved on 15% SDS/PAGE. Antibodies used were anti-HA (16B12; Covance), anti-H3 (1791; Abcam), anti-ubiquitin (FK2, ST1200; Millopore). Core histone was detected by CBB staining. Im7 protein and beads are kind gifts from D.G.V.

For expression in mammalian cells, cDNA of RSF1 was cloned into pcDNA3 and the UAB motif (amino acids 770–807) was in-frame–deleted by site-directed mutagenesis. Constructs encoding Flag-tagged RSF1 and the mutant form of RSF1 were transfected into 293T cells using Lipofectamine 2000. Mononucleosomes were prepared and subjected to anti-Flag immunoprecipitation. Antibodies used were anti-H2Aub antibody (05–678, clone E6C5; Millipore), anti-H2A (07–146; Millipore), anti-Flag (F1804; Sigma).

Knockdown, Knockout, and Knockin Experiments.

To knock down RSF1, RNF2, and SNF2H in HeLa cells, siRNAs were purchased from Sigma. The sequences are as following: RSF1, pair 1: sense sequence GGUAGAAUGCCAGAGUACAdTdT, antisense sequence UGUACUCUGGCAUUCUACCDTDT; and pair 2: sense sequence CCAAGAAGCCCUACCGGAUdTdT, antisense sequence, AUCCGGUAGGGCUUCUUGGdTdT; RNF2, pair 1: sense sequence CUAGUGAAAUUGAAUUAGUdTdT, antisense sequence: ACUAAUUCAAUUUCACUAGDTDT and pair 1: sense sequence: GACUACAAAGGAGUGUUUAdTdT, antisense: UAAACACUCCUUUGUAGUCDTDT; SNF2H, pair one: sense sequence CAACAGAUAUGCAUCUAGUdTdT, antisense sequence ACUAGAUGCAUAUCUGUUGdTdT and pair 2: sense sequence CCUUAAUGAUGAAGAGUUAdTdT, antisense sequence UAACUCUUCAUCAUUAAGGdTdT. The siRNAs (including scrambled control) (10 nM) were transfected into HeLa cells using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Forty-eight hours after transfection, cells were lysed in denaturing lysis buffer (50 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% SDS, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 1% Triton X-100, supplemented with 1% protease inhibitor mixture) by scrapping from culturing dishes, and resolved in SDS/PAGE sample loading buffer. Antibodies used included anti-RSF1 (109002; Abcam), anti-Ring1B (39663; Active Motif), anti-SNF2H (3749; Abcam).

To knock out RSF1 and Ring1B in mouse ESCs and RSF1 in HeLa cells expressing HA-ubiquitin, oligonucleotides were synthesized from IDT and cloned into lentiviral vector lentiCRISPRv2 (Addgene) using BsmBI restriction sites. After verification by sequencing, the lentiviral particles were packaged in 293T cells and transduced into V6.5 cells or HeLa cells in the presence of Hexadimethrine bromide (8 μg/mL) (Cat # H9268; Sigma). The positive clones were selected by puromycin (Cat # A1113803; Fisher) and verified by immunoblots. Antibodies used included anti-RSF1 (109002; Abcam) and anti-Ring1B (39663; Active Motif).

CRISPR/Cas9 system was used to facilitate homologous recombination. To construct the template for homologous recombination, a segment of 386 nucleotides with Flag sequence inserted between the last 236 nucleotides of the RSF1 mRNA and the stop codon was synthesized and cloned into plasmid pUC57 (GeneWiz). The 5′ arm (around 2,500 base pairs, part of intron 15 and part of exon 16) and 3′arm (around 2,300 base pairs, part of 3′UTRs) for recombination were amplified from genomic DNA extracted from V6.5 cells using primers: 5′ arm forward: TATTTGCCTAGCATGCCTGA, reverse: AGTCCAATGGGCTCCCTACT; 3′ arm forward: CAGCGGGCCAGTTAGTAAAG, reverse: GCTGGTGTGTGCAGAGGTAG. These two PCR products were subcloned into pUC57 with synthesized Flag-tagged 3′ end of RSF1 mRNA as described above. To facilitate the selection of cell clones with homologous recombination, a pGKneo cassette conveying resistance to neomycin was amplified from pGKneobpA (Addgene) by PCR using primers: forward: GAAGTTCCTATTCTCTAGAAAG, and reverse: GAAGTTCCTATACTTTCTAG. This cassette was then subcloned into the front of 3′ recombination arm of the pUC57 vector as described above. To generate double-strand break in RSF1 genomic loci, guide RNAs were synthesized and cloned into pX330 (Addgene). Sequences of guide RNAs are: #1, ATCTGATGGTTCTCGAACTA; and #2, GTCAGCGCTCTTAACGGCTG. The pX330 containing the guide RNA #1 or #2 was cotransfected with recombination template into V6.5 using electroporation. 48 h later, G418 (150 μg/mL) was added to the culture medium. Three to 5 d later, positive colonies were picked up, expanded and verified by Western blotting.

RNA-Seq, ChIP-Seq, and Data Analyses.

Samples for mRNA were prepared following the Illumina mRNA sequencing sample preparation guide. Briefly, total RNA was extracted with TRIzol (Cat # 15596026; Invitrogen). mRNA was specifically enriched from total RNA using oligo(dT) beads and hydrolyzed into small pieces. The fragments were then reverse-transcribed into first-strand cDNA using random hexamer primers, followed by second strand synthesis using DNA polymerase I. The short cDNA strands were ligated with 3′- and 5′-adapters for amplification and sequencing (Illumina HiSeq v4; pair end, 50 bp, 50 M reads) in the HudsonAlpha Institute for Technology. RT-qPCR was performed following previous publications (31, 34). Primer sequences are available upon request.

ChIP was prepared following previous publications (31, 34). Briefly, cells were cross-linked with 1% formaldehyde and chromatin was disrupted into 100- to 250-bp fragments by sonication and precipitated using antibody and protein A beads as indicated in the text. After elution from the beads and reverse cross-linking, the DNA fragments in immunoprecipitates were extracted with phenol/chloroform and recovered by ethanol precipitation. IP DNA was ligated with 3′- and 5′-adapters for amplification and sequencing by using Illumina II.

RNA-seq reads were mapped to hg19 or mm10 using STAR v2.5.1b (62). Differentially expressed genes (q value ≤ 0.05) were identified with Cuffdiff (63). The log2 fold-change is a direct output from Cuffdiff. For visualization, the mapped reads were converted into BedGraph format using BEDTools (64). ChIP-seq reads were mapped to hg19 or mm10 using bowtie version 1.1.2 (65). Bam files are sorted by Samtools (66) and PCR duplicates were removed using Picard (broadinstitute.github.io/picard). Peak calling was perform using MACS-1.4.2 (67).

The National Center for Biotechnology Information GEO accession number for all RNA-seq, ChIP-seq, MNase-seq data reported in this paper is GSE93090. Additional public datasets used in this work were also obtained from GEO for data series of GSE10476 (68), GSE23716 (69), GSE49435 (70), and GSE52899 (34).

Nucleosome Mapping.

Mononucleosomes were purified as described above. Mononucleosomes were treated with 50 μg/mL protease K (Cat. # EO0491; Fisher) at 45 °C for 1 h and then resolved on 1.2% agarose. Gels containing mononucleosomes at the size of 150 bp were excised and purified with Qiagen gel purification kit (Cat# 28704; Qiagen). The recovered chromatin DNAs were sequenced using HiSeq v4 PE50 250 M reads 25GB maximum output in the Hudsonalpha Institue. Reads were analyzed and profiled using Danpos (71).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. Runsheng Chen from the Institute of Biophysics, Chinese Academy of Sciences for helpful discussion on this project. This work was supported by NIH Grant GM081489 (to H.W.), National Natural Science Foundation of China Grant 91440116 (to J.L.), National Science Foundation Grant NSF 2016533 (to C.C.), NIH Grant GM098539 (to M.B.R.), and funds from the Anderson Family Endowed Chair (to L.T.C.). H.W. is a Leukemia and Lymphoma Scholar.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Data deposition: The data reported in this paper have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo (accession no. GSE93090).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1711158114/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Kornberg RD, Lorch Y. Twenty-five years of the nucleosome, fundamental particle of the eukaryote chromosome. Cell. 1999;98:285–294. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81958-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zentner GE, Henikoff S. Regulation of nucleosome dynamics by histone modifications. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2013;20:259–266. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tessarz P, Kouzarides T. Histone core modifications regulating nucleosome structure and dynamics. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2014;15:703–708. doi: 10.1038/nrm3890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goldknopf IL, et al. Isolation and characterization of protein A24, a “histone-like” non-histone chromosomal protein. J Biol Chem. 1975;250:7182–7187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mattiroli F, et al. RNF168 ubiquitinates K13-15 on H2A/H2AX to drive DNA damage signaling. Cell. 2012;150:1182–1195. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kalb R, Mallery DL, Larkin C, Huang JT, Hiom K. BRCA1 is a histone-H2A-specific ubiquitin ligase. Cell Rep. 2014;8:999–1005. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.07.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang H, et al. Role of histone H2A ubiquitination in Polycomb silencing. Nature. 2004;431:873–878. doi: 10.1038/nature02985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Laugesen A, Helin K. Chromatin repressive complexes in stem cells, development, and cancer. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;14:735–751. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khan AA, Lee AJ, Roh TY. Polycomb group protein-mediated histone modifications during cell differentiation. Epigenomics. 2015;7:75–84. doi: 10.2217/epi.14.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Piunti A, Shilatifard A. Epigenetic balance of gene expression by Polycomb and COMPASS families. Science. 2016;352:aad9780. doi: 10.1126/science.aad9780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jason LJ, Finn RM, Lindsey G, Ausió J. Histone H2A ubiquitination does not preclude histone H1 binding, but it facilitates its association with the nucleosome. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:4975–4982. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410203200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhu P, et al. A histone H2A deubiquitinase complex coordinating histone acetylation and H1 dissociation in transcriptional regulation. Mol Cell. 2007;27:609–621. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.07.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhou W, et al. Histone H2A monoubiquitination represses transcription by inhibiting RNA polymerase II transcriptional elongation. Mol Cell. 2008;29:69–80. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nakagawa T, et al. Deubiquitylation of histone H2A activates transcriptional initiation via trans-histone cross-talk with H3K4 di- and trimethylation. Genes Dev. 2008;22:37–49. doi: 10.1101/gad.1609708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kalb R, et al. Histone H2A monoubiquitination promotes histone H3 methylation in Polycomb repression. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2014;21:569–571. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jones A, Wang H. Polycomb repressive complex 2 in embryonic stem cells: An overview. Protein Cell. 2010;1:1056–1062. doi: 10.1007/s13238-010-0142-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cooper S, et al. Jarid2 binds mono-ubiquitylated H2A lysine 119 to mediate crosstalk between Polycomb complexes PRC1 and PRC2. Nat Commun. 2016;7:13661. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blackledge NP, et al. Variant PRC1 complex-dependent H2A ubiquitylation drives PRC2 recruitment and Polycomb domain formation. Cell. 2014;157:1445–1459. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cooper S, et al. Targeting Polycomb to pericentric heterochromatin in embryonic stem cells reveals a role for H2AK119u1 in PRC2 recruitment. Cell Rep. 2014;7:1456–1470. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arrigoni R, et al. The Polycomb-associated protein Rybp is a ubiquitin binding protein. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:6233–6241. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Richly H, et al. Transcriptional activation of Polycomb-repressed genes by ZRF1. Nature. 2010;468:1124–1128. doi: 10.1038/nature09574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.LeRoy G, Orphanides G, Lane WS, Reinberg D. Requirement of RSF and FACT for transcription of chromatin templates in vitro. Science. 1998;282:1900–1904. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5395.1900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Loyola A, LeRoy G, Wang YH, Reinberg D. Reconstitution of recombinant chromatin establishes a requirement for histone-tail modifications during chromatin assembly and transcription. Genes Dev. 2001;15:2837–2851. doi: 10.1101/gad.937401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Loyola A, et al. Functional analysis of the subunits of the chromatin assembly factor RSF. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:6759–6768. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.19.6759-6768.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Joo HY, et al. Regulation of cell cycle progression and gene expression by H2A deubiquitination. Nature. 2007;449:1068–1072. doi: 10.1038/nature06256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ong SE, et al. Stable isotope labeling by amino acids in cell culture, SILAC, as a simple and accurate approach to expression proteomics. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2002;1:376–386. doi: 10.1074/mcp.m200025-mcp200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shi Y, et al. Sharp, an inducible cofactor that integrates nuclear receptor repression and activation. Genes Dev. 2001;15:1140–1151. doi: 10.1101/gad.871201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ariyoshi M, Schwabe JW. A conserved structural motif reveals the essential transcriptional repression function of Spen proteins and their role in developmental signaling. Genes Dev. 2003;17:1909–1920. doi: 10.1101/gad.266203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vassylyeva MN, et al. Efficient, ultra-high-affinity chromatography in a one-step purification of complex proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017;114:E5138–E5147. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1704872114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wei J, Zhai L, Xu J, Wang H. Role of Bmi1 in H2A ubiquitylation and Hox gene silencing. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:22537–22544. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600826200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang Z, et al. USP49 deubiquitinates histone H2B and regulates cotranscriptional pre-mRNA splicing. Genes Dev. 2013;27:1581–1595. doi: 10.1101/gad.211037.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hsu PD, Lander ES, Zhang F. Development and applications of CRISPR-Cas9 for genome engineering. Cell. 2014;157:1262–1278. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brookes E, et al. Polycomb associates genome-wide with a specific RNA polymerase II variant, and regulates metabolic genes in ESCs. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;10:157–170. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang W, et al. The histone H2A deubiquitinase Usp16 regulates embryonic stem cell gene expression and lineage commitment. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3818. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Endoh M, et al. Histone H2A mono-ubiquitination is a crucial step to mediate PRC1-dependent repression of developmental genes to maintain ES cell identity. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1002774. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Boyer LA, et al. Polycomb complexes repress developmental regulators in murine embryonic stem cells. Nature. 2006;441:349–353. doi: 10.1038/nature04733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bi X, Yang R, Feng X, Rhodes D, Liu CF. Semisynthetic UbH2A reveals different activities of deubiquitinases and inhibitory effects of H2A K119 ubiquitination on H3K36 methylation in mononucleosomes. Org Biomol Chem. 2016;14:835–839. doi: 10.1039/c5ob02323h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dikic I, Wakatsuki S, Walters KJ. Ubiquitin-binding domains—From structures to functions. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:659–671. doi: 10.1038/nrm2767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Husnjak K, Dikic I. Ubiquitin-binding proteins: Decoders of ubiquitin-mediated cellular functions. Annu Rev Biochem. 2012;81:291–322. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-051810-094654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fradet-Turcotte A, et al. 53BP1 is a reader of the DNA-damage-induced H2A Lys 15 ubiquitin mark. Nature. 2013;499:50–54. doi: 10.1038/nature12318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wilson MD, et al. The structural basis of modified nucleosome recognition by 53BP1. Nature. 2016;536:100–103. doi: 10.1038/nature18951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Morgan MT, et al. Structural basis for histone H2B deubiquitination by the SAGA DUB module. Science. 2016;351:725–728. doi: 10.1126/science.aac5681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Helfricht A, et al. Remodeling and spacing factor 1 (RSF1) deposits centromere proteins at DNA double-strand breaks to promote non-homologous end-joining. Cell Cycle. 2013;12:3070–3082. doi: 10.4161/cc.26033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pessina F, Lowndes NF. The RSF1 histone-remodelling factor facilitates DNA double-strand break repair by recruiting centromeric and Fanconi anaemia proteins. PLoS Biol. 2014;12:e1001856. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Min S, et al. ATM-dependent chromatin remodeler Rsf-1 facilitates DNA damage checkpoints and homologous recombination repair. Cell Cycle. 2014;13:666–677. doi: 10.4161/cc.27548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lee HS, et al. The chromatin remodeller RSF1 is essential for PLK1 deposition and function at mitotic kinetochores. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7904. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Francis NJ, Kingston RE, Woodcock CL. Chromatin compaction by a Polycomb group protein complex. Science. 2004;306:1574–1577. doi: 10.1126/science.1100576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schoenfelder S, et al. Polycomb repressive complex PRC1 spatially constrains the mouse embryonic stem cell genome. Nat Genet. 2015;47:1179–1186. doi: 10.1038/ng.3393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kundu S, et al. Polycomb repressive complex 1 generates discrete compacted domains that change during differentiation. Mol Cell. 2017;65:432–446.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lau MS, et al. Mutation of a nucleosome compaction region disrupts pPlycomb-mediated axial patterning. Science. 2017;355:1081–1084. doi: 10.1126/science.aah5403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pengelly AR, Kalb R, Finkl K, Müller J. Transcriptional repression by PRC1 in the absence of H2A monoubiquitylation. Genes Dev. 2015;29:1487–1492. doi: 10.1101/gad.265439.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Illingworth RS, et al. The E3 ubiquitin ligase activity of RING1B is not essential for early mouse development. Genes Dev. 2015;29:1897–1902. doi: 10.1101/gad.268151.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gu Y, et al. The histone H2A deubiquitinase Usp16 regulates hematopoiesis and hematopoietic stem cell function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:E51–E60. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1517041113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.An W, Palhan VB, Karymov MA, Leuba SH, Roeder RG. Selective requirements for histone H3 and H4 N termini in p300-dependent transcriptional activation from chromatin. Mol Cell. 2002;9:811–821. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00497-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.National Research Council . Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. 8th Ed National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jones A, Joo HY, Robbins W, Wang H. Purification of histone ubiquitin ligases from HeLa cells. Methods. 2011;54:315–325. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Joo HY, et al. Regulation of histone H2A and H2B deubiquitination and Xenopus development by USP12 and USP46. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:7190–7201. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.158311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Luger K, Rechsteiner TJ, Richmond TJ. Preparation of nucleosome core particle from recombinant histones. Methods Enzymol. 1999;304:3–19. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(99)04003-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wang H, et al. Histone H3 and H4 ubiquitylation by the CUL4-DDB-ROC1 ubiquitin ligase facilitates cellular response to DNA damage. Mol Cell. 2006;22:383–394. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Xu Y, et al. Ubp-M serine 552 phosphorylation by cyclin-dependent kinase 1 regulates cell cycle progression. Cell Cycle. 2013;12:3219–3227. doi: 10.4161/cc.26278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cox J, Mann M. MaxQuant enables high peptide identification rates, individualized p.p.b.-range mass accuracies and proteome-wide protein quantification. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:1367–1372. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dobin A, et al. STAR: Ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:15–21. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]