Abstract

Can governments increase private savings by taxing savings up front instead of in retirement? Roth 401(k) contributions are not tax-deductible in the contribution year, but withdrawals in retirement are untaxed. The more common before-tax 401(k) contribution is tax-deductible in the contribution year, but both principal and investment earnings are taxed upon withdrawal. Using administrative data from eleven companies that added a Roth contribution option to their existing 401(k) plan between 2006 and 2010, we find no evidence that total 401(k) contribution rates differ between employees hired before versus after Roth introduction, which implies that take-home pay declines and the amount of retirement consumption being purchased by 401(k) contributions increases after Roth introduction. We reject several neoclassical explanations for our null finding. Results from a survey experiment suggest two behavioral explanations: (1) employee confusion about and neglect of the tax properties of Roth balances and (2) partition dependence.

Keywords: Roth 401(k), Tax salience, Partition dependence

Choosing the right retirement savings rate is complicated. As a result, many employees seem to choose their 401(k) contribution rates using rules of thumb such as “contribute the minimum amount necessary to earn the maximum employer match,” “contribute the maximum amount allowed by the plan,” or “contribute 10% of my pre-tax income” (Choi et al., 2002; Benartzi and Thaler, 2007; Choi et al., 2013). These heuristics are not contingent on the tax treatment of the particular type of 401(k) account used. Even savings recommendations by sophisticated practitioners frequently do not vary according to how the savings vehicles used are taxed (e.g., Ibbotson et al., 2007).1 If individuals neglect taxes when choosing how much to save, it may be possible for governments to increase the after-tax stock of private savings without altering the present value of taxes by shifting the timing of taxation. Rather than allowing savings to be deducted from taxable income today and then taxing both principal and investment earnings when withdrawn in retirement, have individuals save with after-tax dollars today and then exempt the accumulated savings from taxation in retirement.

The following two-period example illustrates how this mechanism would work. Suppose that an individual earns $100 of pre-tax income in period 1, and he follows a rule of thumb when making his savings decision, setting aside 10% of his pre-tax income regardless of the tax rules. The income tax rate is 20%, and the rate of return is r.

First consider the case in which savings are tax-deductible initially and principal and investment earnings are taxed in period 2. The individual saves $10 in period 1, following the 10% rule of thumb; the government collects ($100−$10) × 0.2 = $18 in tax revenue; and the individual consumes the rest of his income, $72. In period 2, the individual has $10 × (1 + r) × (1−0.2) = $8 × (1 + r) of savings available to consume, and the government collects $2 × (1 + r) in taxes.

Now consider the case in which savings cannot be deducted from taxable income initially but principal and investment earnings are not taxed in period 2. The individual's budget constraint is unchanged; by saving only $8 in period 1, he finances the same consumption stream as in the previous scenario. In addition, the after-tax rate of return on saving is unchanged. Hence, we should expect a rational agent who saves $10 in the first regime to save only $8 in the second. Based on this intuition, Robalino et al. (2005, p. 212) conclude that “any difference in the economic impacts of either [tax regime] will be of a second order of magnitude.”2

But if the individual continues to follow the 10% rule of thumb, he saves $10 in period 1; the government collects $20 in tax revenue; and the individual consumes the rest of his income, $70. In period 2, the individual has $10 × (1 + r) of savings available to consume—a 25% increase over the first scenario. This increase in period 2 consumption occurs because period 1 savings did not fall in response to the fact that, in the second scenario, each dollar of savings in period 1 buys more consumption in period 2. The increase in period 2 consumption is financed by the $2 decrease in period 1 consumption, which is necessitated by the fact that savings are not deductible from taxable income. The government collects $0 in taxes in period 2 in the second scenario, but in both scenarios, the present value of taxes is the same, $20.

The introduction of Roth 401(k) savings plans allows us to test whether the above mechanism plausibly exists. Since January 1, 2006, U.S. employers have had the option to include a Roth contribution alternative in their 401(k) retirement savings plan. The Plan Sponsor Council of America (2012) reports that 49% of 401(k) plans offered a Roth option in 2011. Like contributions to a Roth IRA, employee contributions to a Roth 401(k) are not deductible from current taxable income, but withdrawals of principal and investment earnings in retirement are tax-free. In contrast, before-tax 401(k) contributions – the most common type of 401(k) contribution – are deductible from current taxable income, but all principal and investment earnings are taxed upon withdrawal. Therefore, a dollar of Roth balances purchases more retirement consumption than a dollar of before-tax balances if the marginal tax rate in retirement is positive. If people neglect taxes in making savings decisions, the total dollars contributed to the 401(k) will not change when a Roth becomes available, causing effective retirement savings to increase (and current consumption to fall), provided that some of those dollars are contributed to the Roth.

We use administrative 401 (k) plan data from eleven companies that introduced a Roth 401 (k) between 2006 and 2010 to analyze the impact of a Roth option on savings plan contributions. We find no evidence that total contribution rates differ between employees hired after a Roth option is introduced and employees hired before. We consider and reject several neoclassical explanations for our null finding: the fact that the Roth introduction relaxes the effective 401(k) contribution limit, low employee take-up of the Roth option, and kinks in the budget set created by the employer match that inhibit employee savings responses.

The unresponsiveness of total 401(k) contributions to Roth introduction could also be due to the fact that the Roth option makes 401(k) savings more attractive. Savings that would otherwise occur outside the 401(k) (e.g., in a Roth IRA) may shift into the 401(k). Because we have only 401(k) data, we are unable to rule out such a shift. In addition, because tax rates are not flat and time-invariant as in our stylized example, the introduction of the Roth weakly increases the employee's aftertax expected return from saving. If the substitution effect is large enough relative to the income effect, total desired savings weakly increases, and the 401(k) contribution rate should be the margin of adjustment. These forces could in combination fully offset the drop in 401(k) contributions that would otherwise be expected when a Roth becomes available.

Because our field data do not allow us to test these last two explanations, we ran an online survey experiment on 7000 defined contribution plan participants. Respondents were asked to make a 401(k) contribution rate recommendation for a fictional couple for whom asset shifting and substitution effects are not relevant. We also asked four questions to test knowledge of 401(k) tax rules. We continue to find that adding a Roth option causes more retirement consumption to be purchased. Consistent with our motivating hypothesis, we find evidence of employee confusion about and neglect of the tax properties of before-tax and Roth accounts. The experimental results also suggest that partition dependence (Fox et al., 2005 helps keep total contribution rates from falling when a Roth option is introduced. Partition dependence, which results from a bias towards allocating an equal amount to every discrete option available in a choice set, predicts an increase in total savings when the choice set is {current consumption, before-tax saving, Roth saving} instead of {current consumption, before-tax saving}.

The remainder of the paper proceeds as follows. In Section 1, we summarize the key institutional rules regulating 401(k) savings. Section 2 describes our 401(k) data. Section 3 discusses our estimates of the impact of Roth 401(k) introduction on total 401(k) contribution rates, and Section 4 presents our survey experiment. Section 5 concludes.

1. Background on 401(k) contributions

A traditional 401(k) savings plan allows employees to make before-tax 401(k) contributions that are deductible from current-year taxable income. In lieu of current taxation, the principal and investment earnings are taxed at the individual's ordinary income tax rate upon withdrawal. Hence, the marginal dollar of pre-tax income buys (1 + r)(1 − τ1) of future consumption if it is contributed to a before-tax 401(k) account, where r is the return earned on the contribution between the contribution and withdrawal dates and τ1 is the household's marginal ordinary income tax rate in the year of the withdrawal plus an adjustment if the withdrawal generates an increase in the taxation of Social Security benefits or a reduction in means-tested benefits. An additional 10% tax penalty applies to both the principal and earnings withdrawn if the account owner is younger than 59½ years old.

In contrast to contributions to a before-tax 401(k), Roth contributions are not deductible from current-year taxable income, but principal and investment earnings may be withdrawn tax-free if the withdrawal is considered qualified.3 The marginal dollar of pre-tax income can thus purchase (1 − τ0)(1 + r) of future consumption if a Roth account is used as the savings vehicle and the balance is accessed through a qualified withdrawal, where τ0 is the household's marginal ordinary income tax rate plus any marginal reduction in means-tested benefits due to the additional dollar of taxable income in the year of the contribution. Put another way, each dollar contributed to a Roth account buys 1 + r of future consumption. For non-qualified withdrawals, the withdrawn principal is not taxed, but the earnings are subject to ordinary income tax. If the account owner is younger than 59½, the withdrawn earnings are also assessed a 10% tax penalty under most circumstances. The appeal of Roth contributions relative to before-tax contributions increases with the probability of withdrawal before age 59½, since Roth principal is exempt from the 10% early withdrawal penalty but before-tax principal is not.

Some 401(k) plans allow participants to make after-tax contributions. Like Roth contributions, after-tax 401(k) contributions are not deductible from current taxable income, and principal can be withdrawn tax-free from after-tax accounts. Unlike Roth contributions, however, earnings on after-tax contributions are taxed at the ordinary income tax rate when withdrawn. If an after-tax 401(k) account is used, the marginal dollar of pre-tax income can buy (1 − τ0)[1 + (1 − τ1)r] of future consumption; equivalently, each dollar contributed to an after-tax account buys 1 + (1 − τ1)r of future consumption. An additional 10% tax penalty applies to earnings (but not principal) withdrawn by account owners younger than 59½. After-tax contributions are not common. In 1999, only 7% of 401(k) participants made an after-tax contribution (Holden and Vanderhei, 2001).

Internal Revenue Service regulations stipulate that the sum of an individual's before-tax and Roth contributions in a calendar year cannot exceed a certain limit that is adjusted each year. For individuals younger than 50, this limit was $14,000 in 2005 (the last year before Roth contributions were allowed); it has been increased several times since then and stands at $18,000 in 2015. Those age 50 and older are allowed an additional “catch-up” contribution; this additional amount was $4000 in 2005 and has since been increased to its current (2015) level of $6000. Because a dollar of Roth balances buys weakly more retirement consumption than a dollar of before-tax balances, people who are constrained by the before-tax plus Roth contribution ceiling could find it advantageous to make Roth contributions instead of before-tax contributions in order to extend the 401(k) tax shelter over more effective dollars. In addition to the limits on employee contributions, there is a limit on the sum of employer and employee contributions that was $42,000 in 2005 and has been raised to $53,000 in 2015 for individuals younger than 50.

Although employers can structure their savings plans to allow Roth, before-tax, and after-tax employee contributions, employer matching contributions must be made using before-tax dollars, so the entire principal and earnings of the match balance are subject to ordinary income tax upon withdrawal. A company might not match certain types of employee contributions (e.g., after-tax contributions), but among the types of contributions it does match, the match formula typically does not vary by the type of contribution. This invariance reduces the attractiveness of Roth and after-tax contributions if the employee's marginal 401(k) contribution dollar is being matched.4 Despite the Roth's disadvantaged position with respect to the match, as long as τ1 > 0, it is still the case that one needs to contribute less than $1 to the Roth in order to buy as much retirement consumption (including what the match would fund) as one would get from contributing $1 before-tax and earning the match.5

2. Data description

For our analysis,we use administrative data from the 401(k) plans of eleven U.S. firms that introduced a Roth option to their savings plan between 2006 and 2010. The data come from Aon Hewitt, a large benefits administration and consulting firm. For each firm, we have repeated cross-sectional snapshots at the end of each calendar year that contain individual-level data on every employee's current plan participation status, plan enrollment date, monthly contribution rates, plan balances, birth date, hire date, salary (for eight of the eleven companies), and gender.6 We restrict our sample to employees between the ages of 20 and 69.

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the eleven companies as of year-end 2010. In order to preserve anonymity, we refer to each company by the letters A through K and only disclose approximate employee counts. The companies are all large, ranging from approximately 10,000 employees to 100,000 employees. Seven of the eleven companies are in the financial services industry, and average salaries exceed $100,000 at Companies A, D, E, and H. Hence, the employees at these firms are likely to be more financially sophisticated than the typical U.S. employee. Average employee age ranges from 35 to 48 years; average tenure at the companies ranges from five years to sixteen years; and the percentage male ranges from 33% to 76%.

Table 1.

Company characteristics as of 2010.

| Company | Industry | Total employees | Average age | Median salary | Average salary | Average tenure | Percent male |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Pharmaceutical | ∼50,000 | 43.1 | $95,100 | $106,089 | 10.6 years | 54% |

| B | Financial services | ∼10,000 | 46.4 | $77,079 | $84,285 | 11.9 years | 42% |

| C | Financial services | ∼25,000 | 43.7 | $54,687 | $73,679 | 9.6 years | 46% |

| D | Financial services | ∼50,000 | 35.0 | $140,598 | $295,206 | 4.9 years | 61% |

| E | Financial services | ∼25,000 | 44.0 | $80,304 | $148,184 | 8.4 years | 60% |

| F | Financial services | ∼10,000 | 47.5 | N/A | N/A | 12.2 years | 53% |

| G | Financial services | ∼25,000 | 40.7 | N/A | N/A | 8.9 years | 33% |

| H | Business services | ∼25,000 | 36.4 | $83,900 | $109,856 | 6.6 years | 62% |

| I | Manufacturing | ∼25,000 | 46.6 | $59,218 | $74,808 | 16.0 years | 65% |

| J | Manufacturing | ∼100,000 | 45.7 | $67,694 | $77,694 | 13.4 years | 76% |

| K | Financial services | ∼10,000 | 42.3 | N/A | N/A | 8.1 years | 35% |

Table 2 summarizes the key features of the 401(k) plan at each company in the year that the Roth option was introduced. Five companies introduced the Roth option in 2006, one in 2007, two in 2008, one in 2009, and two in 2010. Four companies automatically enrolled their employees in the 401(k) at before-tax contribution rates between 2% and 6% of income. Consistent with findings from the previous literature (Choi et al., 2002, 2004; Beshears et al., 2008), the 401(k) participation rate among employees who have 11 months of tenure at the end of the calendar year in which the Roth was introduced is substantially higher at firms with automatic enrollment than at firms with opt-in enrollment schemes: 92% vs. 54%. Nine companies match employee contributions up to a threshold between 2% and 8% of income at rates between 25% and 133%. The maximum percent of a paycheck that can be contributed to the 401(k) ranges from 20% to 100%.

Table 2.

401(k) plan characteristics in year of Roth introduction.

| Company | Participation rate at 11 months after hire | Enrollment default | Employer match structure | Max contribution allowed (% of salary) | Roth 401(k) introduction date |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 93% | 3% before-tax contribution rate | 75% match on first 6% of income contributed after 1 year of tenure | 50% | Jan 1, 2008 |

| B | 93% | 3% before-tax contribution rate | 70% match on first 6% of income contributed | 20% | Sep 1, 2006 |

| C | 61% | Non-enrollment | 133% match on first 3% of income contributed after 1 year of tenure | 45% | Jan 1, 2006 |

| D | 62% | Non-enrollment | No match | 50% | Feb 1, 2006 |

| E | 63% | Non-enrollment | 100% match on first 6% of income contributed after 1 year of tenure | 100% | Jan 1, 2007 |

| F | 60% | Non-enrollment | No match | 50% | Jan 1, 2006 |

| G | 31% | Non-enrollment | 115% match on first 6% of income contributed after 1 year of tenure | 20% | Jan 1, 2008 |

| H | 64% | Non-enrollment | Either 33%, 50%, or 100% match on first 6% of income contributed | 50% | Jan 1, 2006 |

| I | 90% | 6% before-tax contribution rate | Either 70% or 100% match on first 6% of income contributed | 35% | Jan 1, 2009 |

| J | 91% | 2% before-tax contribution rate | 100% match on the first 2% of income contributed, 50% match on the next 2% of income contributed, and 25% match on the next 4% of income contributed | 75% | Jan 1, 2010 |

| K | 37% | Non-enrollment | 50% match on the first 6% of income contributed | 100% | Jul 1, 2010 |

3. The impact of Roth introduction on total 401(k) contribution rates

To estimate the impact of Roth introduction on retirement savings, we compare the 401(k) contribution rates of employees hired before the Roth introduction to those of employees hired after the Roth introduction, controlling for tenure at the company.7 Our identifying assumption is that conditional on one's employer, whether one has access to the Roth immediately upon hire or shortly after hire is orthogonal to savings preferences, an assumption that seems plausible. Because there may be seasonal patterns in the types of employees hired, we restrict our analysis to employees hired in the same calendar month at each firm. Specifically, we compare employees hired in the twelfth month prior to the introduction of the Roth to employees hired one year later, in the month immediately following the introduction of the Roth. This allows us to follow the contributions of newly hired employees through eleven months of tenure (after which the pre-Roth hire cohort becomes eligible to contribute to a Roth account).

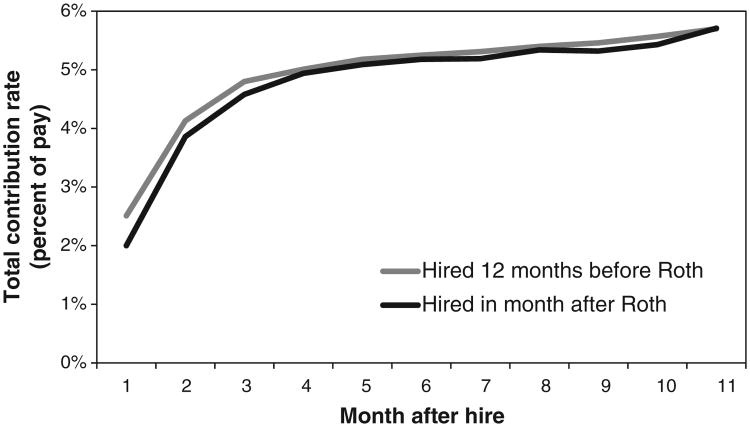

Table 3 shows the average age at hire, average annual salary in the year of hire, and gender composition of the pre-Roth and post-Roth hire cohorts at each company. Companies F, G, and K do not have salary data available. Five companies – B, D, E, F, and G – experienced no statistically significant changes across cohorts in their observed variables. The other six companies experienced at least one statistically significant change. We will control for age, salary (when possible), and gender in the regressions that follow, but it is possible that companies in which observed characteristics change across cohorts are more likely to have unobserved characteristics change across cohorts as well. We will therefore examine effects averaged across all companies and also across the subset of companies where no observable characteristics changed significantly. We start our analysis by plotting in Fig. 1 the average total 401(k) contribution rate (before-tax plus after-tax contribution rates for the pre-Roth cohort, and before-tax plus after-tax plus Roth contribution rates for the post-Roth cohort) of each hire cohort against tenure for all eleven companies combined. Non-participants in both cohorts are coded as having a total contribution rate of zero. The average total contribution rate of both cohorts increases with tenure, a trend that largely reflects increases in savings plan participation rather than increases in contribution rates among those already participating. Comparing the total contribution rates of the two cohorts, we see that the lines in Fig. 1 lie nearly on top of each other, particularly after the third month of tenure. The difference in the average total contribution rate between the two cohorts is small and only statistically significant in the first month of tenure.8 These results suggest that adding a Roth contribution option to the 401(k) plan does not cause total 401(k) contributions to decline.

Table 3.

Comparison of hire cohort characteristics.

This table shows the average age as of hire date, average salary, and gender composition at each company among employees who were hired in the twelfth month prior to Roth introduction or in the month after Roth introduction. The change in these variables between the before and after cohorts is also reported, with standard errors in parentheses. Salary is in 2005 dollars, deflated by CPI-W. The last column shows the number of employees in the before and after cohorts combined. Salaries are calculated using fewer employees than in the last column because of missing data.

| Company | Age (years) | Salary | Percent male | N | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||||||

| Before Roth | After Roth | Change | Before Roth | After Roth | Change | Before Roth | After Roth | Change | ||

| A | 36.4 | 33.7 | −2.75** (0.74) | $83,192 | $65,121 | −$18,071** (3420) | 47.6% | 44.7% | 2.91% (4.07) | 603 |

| B | 36.8 | 38.3 | 1.54 (2.20) | $62,684 | $67,462 | 4778 (6981) | 38.4% | 48.6% | 10.22 (9.73) | 108 |

| C | 35.0 | 37.3 | 2.26**(0.83) | $39,133 | $41,183 | 2050 (3304) | 58.9% | 46.7% | −12.12** (3.90) | 652 |

| D | 31.2 | 29.5 | −1.69 (0.94) | $184,811 | $160,114 | −24,697 (30,906) | 60.6% | 68.4% | 7.83 (6.37) | 226 |

| E | 35.9 | 36.1 | 0.21 (1.06) | $59,908 | $66,787 | 6879 (5953) | 58.0% | 54.9% | −3.08 (4.74) | 444 |

| F | 38.7 | 36.5 | −2.21 (1.40) | N/A | N/A | N/A | 46.9% | 48.8% | 1.92 (5.98) | 285 |

| G | 33.6 | 33.1 | −0.51 (0.77) | N/A | N/A | N/A | 39.1% | 42.2% | 3.13 (3.55) | 775 |

| H | 34.4 | 33.2 | −1.18 (0.74) | $66,492 | $78,773 | 12,281**(3401) | 58.2% | 58.9% | 0.70 (3.44) | 904 |

| I | 35.5 | 37.7 | 2.28 (2.36) | $55,814 | $74,345 | 18,531*(7240) | 64.3% | 50.0% | −14.34 (11.19) | 151 |

| J | 36.3 | 37.9 | 1.57*(0.68) | $59,479 | $62,280 | 2800 (1812) | 71.5% | 74.6% | 3.07 (2.52) | 1334 |

| K | 35.8 | 38.1 | 2.31 (2.85) | N/A | N/A | N/A | 64.3% | 42.9% | −21.43*(12.10) | 70 |

Significant at 5% level.

Significant at 1% level.

Fig. 1.

Average total contribution rate by hire cohort.

In Table 4, we show the average total contribution rates for the pre-Roth and post-Roth cohorts separately for each company at six and eleven months after hire.9 The only six-month difference that is statistically significant at the 5% level is at Company A, where the post-Roth cohort contributes 0.95% of income less than the pre-Roth cohort. At eleven months, the only statistically significant differences are at Companies A and G, where the post-Roth cohorts contribute 1.25% and 0.78% of income less than the pre-Roth cohorts, respectively. Pooling together all eleven companies yields statistically insignificant and economically small Roth introduction effects: an average contribution rate decrease of 0.06% of pay at six months of tenure and a 0.02% of pay increase at eleven months of tenure. Restricting the analysis to companies with no significant observable changes in employee characteristics across hire cohorts yields an insignificant average contribution rate increase of 0.14% at six months and a decrease of 0.01% of income at eleven months.

Table 4.

Average total contribution rates by hire cohort.

This table shows the average total employee contribution rate (before-tax plus Roth plus after-tax) at six or eleven months after hire among employees who were hired in the twelfth month prior to Roth introduction or in the month after Roth introduction. The change in the average total contribution rate between the before and after cohorts is also reported, with standard errors in parentheses. The penultimate row shows the averages pooling all companies together, and the last row shows the averages excluding companies that had one or more significant demographic changes across the before and after hire cohorts in Table 3.

| Company | Total contribution rate 6 months after hire | Total contribution rate 11 months after hire | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| Before Roth | After Roth | Difference | Before Roth | After Roth | Difference | |

| A | 7.48 | 6.53 | −0.95*(0.46) | 8.14 | 6.89 | −1.25*(0.51) |

| B | 5.71 | 7.17 | 1.46 (0.98) | 5.85 | 7.09 | 1.24 (1.01) |

| C | 3.45 | 3.63 | 0.18 (0.42) | 3.88 | 4.31 | 0.43 (0.45) |

| D | 7.26 | 5.97 | −1.28 (1.33) | 6.99 | 7.76 | 0.77 (1.47) |

| E | 7.33 | 7.29 | −0.04 (1.38) | 9.86 | 9.02 | −0.84 (1.89) |

| F | 5.03 | 4.89 | −0.14 (0.97) | 5.35 | 4.92 | −0.43 (1.03) |

| G | 2.14 | 2.07 | −0.07 (0.31) | 2.94 | 2.16 | −0.78*(0.32) |

| H | 5.45 | 5.89 | 0.44 (0.52) | 5.84 | 6.59 | 0.75 (0.55) |

| I | 7.40 | 7.86 | 0.46 (1.39) | 7.05 | 7.86 | 0.82 (1.30) |

| J | 5.54 | 6.00 | 0.46 (0.30) | 5.56 | 6.11 | 0.55 (0.31) |

| K | 2.96 | 2.29 | −0.68 (1.15) | 3.36 | 2.19 | −1.17 (1.15) |

| All | 5.25 | 5.18 | −0.06 (0.20) | 5.70 | 5.71 | 0.02 (0.23) |

| All with no demographic changes | 4.53 | 4.67 | 0.14 (0.44) | 5.44 | 5.43 | −0.01 (0.55) |

Significant at 5% level.

To control for any changes in the demographic composition of employees hired before versus after Roth introduction, in Table 5 we regress total contribution rates at six or eleven months of tenure on a post-Roth hire cohort dummy, age, age squared, a male dummy, and log salary. As in Table 4, we report the results first separately for each firm, and then pooling firms together. The regression results are qualitatively similar to the results from the simple mean comparisons in Table 4. Out of 22 post-Roth hire cohort dummy coefficient estimates at the individual company level (eleven at six months of tenure and eleven at eleven months of tenure), only one is significant at the 5% level, about what one would expect by chance. Pooling together all eight companies with complete employee demographic data yields insignificant estimates of the effect of Roth introduction on the total contribution rate equal to 0.09% and 0.34% of income at six and eleven months of tenure, respectively. Excluding companies with significant observable employee characteristic changes yields insignificant Roth effects of −0.08% of income at six months of tenure and 0.26% at eleven months of tenure.

Table 5.

The impact of Roth introduction on total 401(k) contribution rates

Each row is an ordinary least squares regression where the dependent variable is the total employee contribution rate (before-tax plus Roth plus after-tax) at six months after hire (panel A) or eleven months after hire (panel B). The sample is employees who were hired in the twelfth month prior to Roth introduction or in the month after Roth introduction at the company indicated in the first column. The penultimate row in each panel includes in its sample all companies that have a complete set of employee characteristic data. The last row in each panel includes all companies that have a complete set of employee characteristic data and did not have a significant demographic change across the before and after hire cohorts in Table 3. The explanatory variables are a constant, a dummy for being in the post-Roth hire cohort, age as of hire date, age squared, a male dummy, and log salary in the year of hire (in 2005 dollars). Standard errors are in parentheses.

| Panel A: contribution rate 6 months after hire | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Company | Roth | Age | Age2 | Male | log(salary) | N |

| A | −0.109 (0.489) | −0.088 (0.217) | 0.003 (0.003) | 0.236 (0.477) | 2.018**(0.594) | 519 |

| B | 1.095 (0.899) | −0.281 (0.319) | 0.004 (0.004) | −0.149 (0.953) | 4.160**(1.032) | 108 |

| C | 0.398 (0.411) | 0.270 (0.144) | −0.003 (0.002) | 0.467 (0.407) | 1.744**(0.241) | 650 |

| D | −1.165 (1.341) | −0.548 (0.833) | 0.012 (0.012) | 0.491 (1.418) | −0.372 (1.104) | 225 |

| E | −0.146 (1.384) | 0.416 (0.436) | −0.003 (0.005) | −0.443 (1.475) | 0.161 (0.878) | 441 |

| F | 0.244 (0.949) | 0.333 (0.277) | −0.002 (0.003) | 1.212 (0.938) | N/A | 285 |

| G | −0.045 (0.306) | 0.355**(0.103) | −0.004**(0.001) | 1.016**(0.311) | N/A | 775 |

| H | 0.094 (0.524) | −0.646**(0.165) | 0.009**(0.002) | −0.592 (0.527) | 4.371**(0.647) | 890 |

| I | −0.543 (1.319) | −0.913**(0.329) | 0.013**(0.004) | −0.761 (0.949) | 3.692**(0.932) | 150 |

| J | 0.252 (0.287) | −0.298**(0.083) | 0.004**(0.001) | −0.221 (0.315) | 3.125**(0.246) | 1326 |

| K | −0.889 (1.197) | 0.102 (0.413) | 0.000 (0.005) | −0.250 (1.169) | N/A | 70 |

| All with complete data | 0.090 (0.230) | −0.133 (0.074) | 0.003**(0.001) | −0.162 (0.235) | 2.214**(0.165) | 4309 |

| Complete data, no demographic changes | −0.084 (0.880) | 0.250 (0.303) | −0.001 (0.004) | 0.242 (0.930) | 0.260 (0.522) | 774 |

|

| ||||||

| Panel B: contribution rate 11 months after hire | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Company | Roth | Age | Age2 | Male | log(salary) | N |

| A | −0.536 (0.558) | 0.079 (0.247) | 0.001 (0.003) | 0.786 (0.544) | 1.727*(0.678) | 519 |

| B | 0.903 (0.925) | −0.276 (0.328) | 0.004 (0.004) | −0.614 (0.980) | 4.396**(1.062) | 108 |

| C | 0.415 (0.451) | 0.258 (0.158) | −0.003 (0.002) | 0.173 (0.446) | 0.646*(0.264) | 650 |

| D | 0.988 (1.481) | −1.020 (0.920) | 0.019 (0.013) | −0.169 (1.566) | 0.299 (1.220) | 225 |

| E | −0.978 (1.899) | 0.672 (0.598) | −0.005 (0.007) | −0.400 (2.025) | 0.297 (1.205) | 441 |

| F | −0.051 (1.012) | 0.094 (0.295) | 0.001 (0.004) | 0.465 (1.000) | N/A | 285 |

| G | −0.781* (0.314) | 0.213*(0.106) | −0.002 (0.001) | 1.260**(0.320) | N/A | 775 |

| H | 0.381 (0.550) | −0.569**(0.173) | 0.008**(0.002) | −0.039 (0.554) | 4.332**(0.680) | 890 |

| I | 0.038 (1.228) | −0.890**(0.307) | 0.013**(0.004) | −0.168 (0.883) | 2.967**(0.868) | 150 |

| J | 0.359 (0.295) | −0.153 (0.085) | 0.002*(0.001) | −0.607 (0.324) | 2.844**(0.253) | 1326 |

| K | −1.429 (1.198) | −0.088 (0.413) | 0.002 (0.005) | −0.102 (1.169) | N/A | 70 |

| All with complete data | 0.339 (0.275) | −0.004 (0.089) | 0.001 (0.001) | −0.133 (0.282) | 1.940**(0.197) | 4309 |

| Complete data, no demographic changes | 0.264 (1.164) | 0.446 (0.400) | −0.003 (0.005) | 0.353 (1.230) | 0.132 (0.691) | 774 |

Significant at 5% level.

Significant at 1% level.

Our analysis thus far indicates that introducing a Roth option to the 401(k) does not significantly change total contributions to the 401(k). An unchanged total contribution rate translates into higher after-tax retirement consumption if some of those contributions are directed to the Roth and the balances are kept in the Roth for a long enough period of time.

One potential explanation for why there is no difference in average total contributions between the pre- and post-Roth cohorts is that the introduction of the Roth relaxes the effective 401(k) contribution limit, since the same dollar limit applies to both Roth and before-tax contributions despite Roth dollars being more valuable in retirement than before-tax dollars. Suppose somebody with only a before-tax 401(k) contribution option would like to contribute $50,000 in before-tax dollars to the 401(k) in 2010. He is constrained to contribute only $16,500 in before-tax dollars, the IRS contribution limit in 2010. If he had access to a Roth 401(k), he might contribute $16,500 to the Roth instead because doing so gets him closer to the retirement consumption he would have been able to afford with a $50,000 before-tax contribution. For this person, the in sensitivity of total contributions to Roth availability is created by the fact that the contribution limit binds both with and without the Roth option.

Such a censoring mechanism is unlikely to explain why we find total contribution rate insensitivity in our data. In the calendar year of their hire, only 3.1% of employees in the pre-Roth cohort across all of our sample companies were at the employee before-tax contribution limit, were at the combined employee plus employer contribution limit, or were contributing the maximum percentage of salary allowed by their 401(k) plan for the entire year. This proportion is similar to the 2.8% of employees in the post-Roth hire cohort who were analogously constrained. Appendix Table 2 shows the results from tobit regressions analogous to the ordinary least squares contribution rate regressions in Table 5. Allowing for left-censoring at zero and right-censoring if the employee was at any of the relevant limits does not qualitatively change our estimates of the Roth introduction effect on total contribution rates.

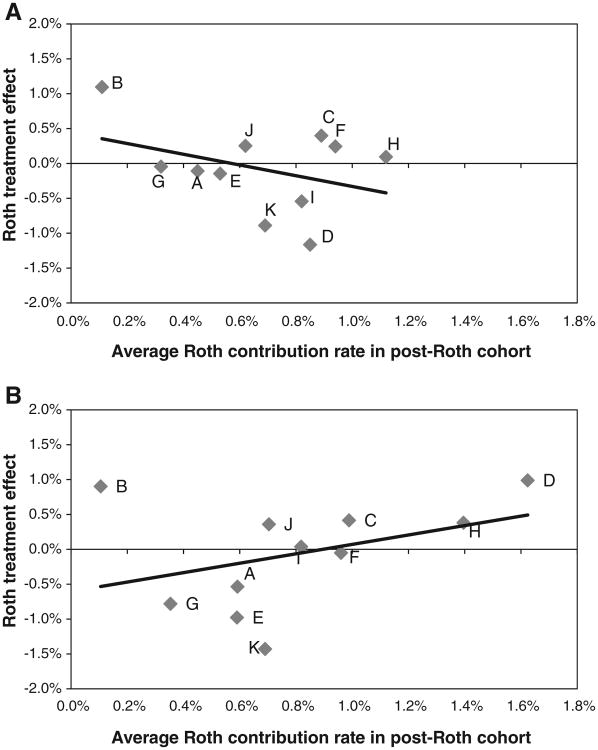

A second potential explanation is that post-Roth employees are not contributing to the newly available Roth accounts, in which case we should not expect any change in average total contribution rates. To assess whether insufficient Roth participation could account for the trivial total contribution rate effects that we estimate, we examine the correlation across firms between the estimated Roth treatment effect and the average Roth contribution rate for the post-Roth cohort. If small average total contribution rate effects arise from low Roth contribution rates, this correlation should be a negative.

Fig. 2A and B graph the estimated Roth introduction effect at each company (from Table 5) against the average Roth contribution rate in the company's post-Roth cohort (from Appendix Table 1) at six and eleven months after hire, respectively. The average Roth contribution rate ranges from 0.1% to 1.1% of pay at six months, and that range widens to between 0.1% and 1.6% of pay at eleven months. The fitted regression lines indicate that weighting each company equally, there is an insignificant negative association between the estimated treatment effect and the average Roth contribution rate at six months of tenure (slope = −0.77, t = −1.18, p = 0.268) and an insignificant positive association at eleven months of tenure (slope = 0.679, t = 1.22, p = 0.252). At both time horizons, the point estimate of the Roth introduction effect is positive at the three companies with the highest average Roth contribution rates. Overall, there is little support for the notion that our null estimates of the impact of Roth introduction on total 401(k) contributions are due to limited Roth participation.

Fig. 2.

A. Estimated Roth treatment effects on total contribution rate against average Roth contribution rates among post-Roth hires, 6 months after hire. The y-axis values are the individual company post-Roth hire cohort dummy coefficients from the regressions found in Table 5, panel A. The x-axis values are the average Roth contribution rate of the post-Roth hire cohort at each company at 6 months after hire. B. Estimated Roth treatment effects on total contribution rate against average Roth contribution rates among post-Roth hires,11 months after hire. The y-axis values are the individual company post-Roth hire cohort dummy coefficients from the regressions found in Table 5, panel B. The x-axis values are the average Roth contribution rate of the post-Roth hire cohort at each company at 11 months after hire.

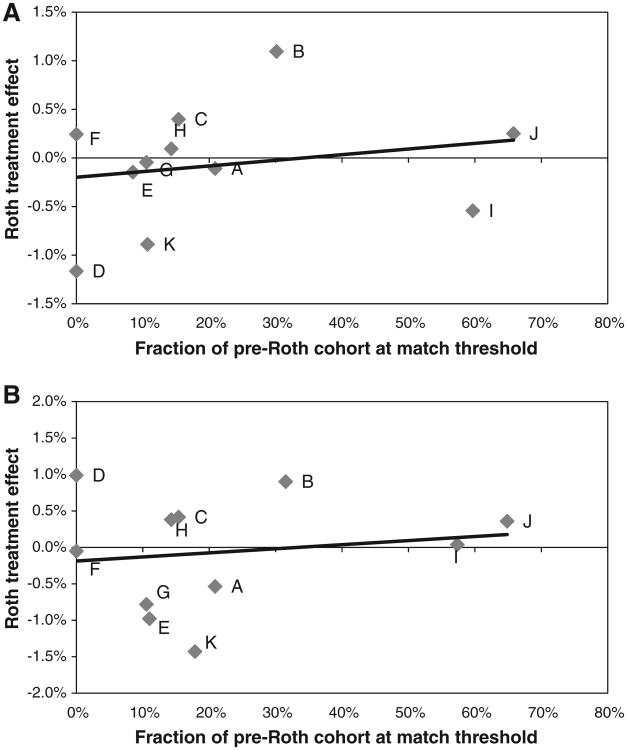

A third potential explanation is that there are many employees at kinks in the budget set created by match thresholds, where they should rationally not be very responsive to changes in savings incentives. To assess the importance of this explanation, Fig. 3A and B graph the estimated Roth introduction effect at each company (from Table 5) against the fraction of the pre-Roth hire cohort contributing at a match threshold at six and eleven months after hire, respectively.10 The fraction of employees at a match threshold ranges from a low of 0% (at the two companies with no match) to a high of 66% at six months of tenure and 65% at eleven months of tenure (at Company J, which has a tiered match). At both time horizons, there is no relationship between the estimated Roth effect at each firm and the fraction of pre-Roth employees who are at a match threshold. The regression lines in Fig. 3A and B are practically flat, and the slope coefficients are both small and statistically insignificant (slope = 0.006, t = 0.63, p = 0.543 at six months; slope = 0.006, t = 0.60, p = 0.566 at eleven months). Examining the predicted Roth effect when there are no employees at the match threshold (and thus the budget set kink is not a plausible explanation for the absence of a Roth effect), we see that at six months, the intercept of the regression line in Fig. 3A is small and not significantly different from zero (intercept = −0.199, t = −0.72, p = 0.491), as is the case at eleven months in Fig. 3B (intercept = −0.150, t = −0.47, p = 0.646). The average Roth effect within the two companies that have no match falls on both sides of zero depending on horizon: −0.46% at six months and 0.47% at eleven months. Taken together, there is no compelling evidence that our null Roth introduction effects are due to employees remaining at budget set kinks.

Fig. 3.

A. Estimated Roth treatment effects on total contribution rate against fraction of pre-Roth hires contributing at a match threshold, 6 months after hire. The y-axis values are the individual company post-Roth hire cohort dummy coefficients from the regressions in Table 5, panel A. The x-axis values are the fraction of the pre-Roth hire cohort contributing at a match threshold at each company 6 months after hire. B. Estimated Roth treatment effects on total contribution rate against fraction of pre-Roth hires contributing at a match threshold, 11 months after hire. The y-axis values are the individual company post-Roth hire cohort dummy coefficients from the regressions in Table 5, panel B. The x-axis values are the fraction of the pre-Roth hire cohort contributing at a match threshold at each company 11 months after hire.

4. Survey experiment

Although we find that 401(k) contributions do not drop when a Roth option is introduced, our data cover only the 401(k), so we do not know the extent to which the increased effective saving inside the 401(k) is offset by decreased saving outside the 401(k). Furthermore, even if we knew that offset is minimal, we cannot tell from our data whether employees increase their effective saving due to confusion about and/ or neglect of the tax properties of Roth balances, or due to a rational substitution effect created by the Roth 401(k) increasing the after-tax return on savings.

To gauge how important savings offset and the substitution effect are, we ran an experiment within the Boston Research Group's online 2014 Defined Contribution Plan Participant survey. All respondents were current participants in a 401(k), 403(b), 457, or profit-sharing savings plan whose record-keeper was one of 30 major record-keeping companies. Of course, survey responses raise questions of external validity; subjects' responses do not affect their economic outcomes, and neighbors, co-workers, family, the media, and professional advisors influence individuals' financial choices in the field (Beshears et al., 2015; Brown et al., 2008; Chalmers and Reuter, 2012; Duflo and Saez, 2002 and Duflo and Saez, 2003; Engelberg and Parsons, 2011; Hong et al., 2004; Tetlock, 2007). Nonetheless, survey responses shed light on individuals' intuitions about optimal choices. Intuitive choices may serve as an initial anchor from which people adjust away, and this adjustment may be only partial (Tversky and Kahneman, 1974).

Respondents were randomly assigned to make a 401(k) contribution rate recommendation for a fictional couple with a relatively high income (and hence a positive current marginal tax rate) who has access to (1) only a before-tax 401(k) account, (2) only a Roth 401(k) account, or (3) both before-tax and Roth 401(k) accounts. Respondents were told that this couple has minimal existing savings and wishes to do all of its saving over the next year in the husband's 401(k), so changes in the husband's 401(k) contribution rate represent the entire change in the couple's savings rate. In addition, their goal is to have a material standard of living that does not change for the rest of their lives; that is, their substitution effect is zero. The husband's 401(k) does not allow withdrawals before age 59½ for any reason, so the fact that early withdrawals from Roth balances face a lesser tax penalty than early withdrawals from before-tax balances should play no role in the contribution rate recommendation. Other details of the vignette were chosen to make the couple's circumstances familiar ones to most respondents.

The first question asked of respondents in the before-tax account condition was, “What percent of Jack's $100,000 income should he contribute as a before-tax contribution to his 401(k) plan over the next 12 months? The maximum he is allowed to contribute is 17.5%. If you would like Jack to contribute nothing, the box must have a ‘0’ in it.” The second question asked was, “What percent of Jack's 401(k) contributions should be invested in stocks? (The rest of the contributions will be invested in bonds.) Enter a number between 0 and 100.”

Respondents in the Roth-only condition saw identical text, except we substituted in the sentence, “Jack's company offers a 401(k) retirement savings plan that only has a Roth contribution option (it only accepts after-tax dollars),” and asked for a Roth contribution rate. Respondents in the both-accounts condition instead saw the sentence, “Jack's company offers a 401(k) retirement savings plan that allows both before-tax contributions and Roth (i.e., after-tax dollar) contributions.” Half of subjects in this condition were asked to type in a before-tax contribution rate and a Roth contribution rate on the same screen in which the vignette text appeared. This elicitation mimics the usual way 401(k) contribution rates are elicited from employees. The other half of subjects were asked to first type in the total before-tax plus Roth contribution rate, knowing that they would specify on the next screen how this total contribution rate would be split between a before-tax contribution rate and a Roth contribution rate.

After making their contribution rate and asset allocation recommendations, respondents in all arms of the survey were asked two randomly selected11 questions from a set of four possible questions about 401(k) tax rules. The appendix shows the text of all of the questions asked in the survey. Our sample contains 7000 respondents, of whom 1749 were in the before-tax-only condition, 1750 were in the Roth-only condition, 1750 were in the both-accounts condition and were asked to enter both the before-tax and Roth contribution rates on the first screen, and 1751 were in the both-accounts condition and were asked to enter only a total contribution rate on the first screen.

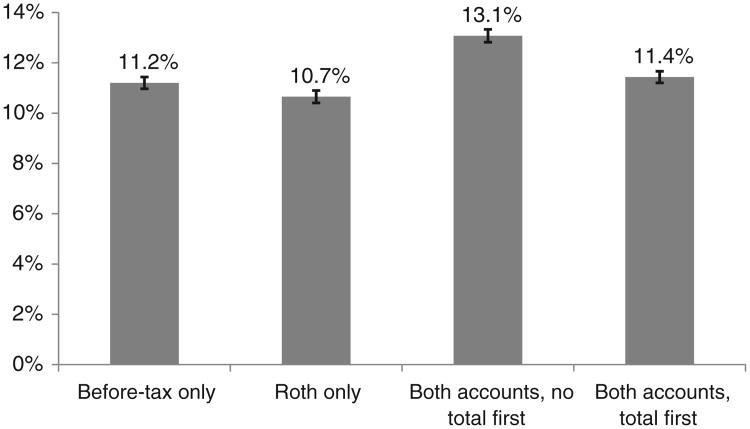

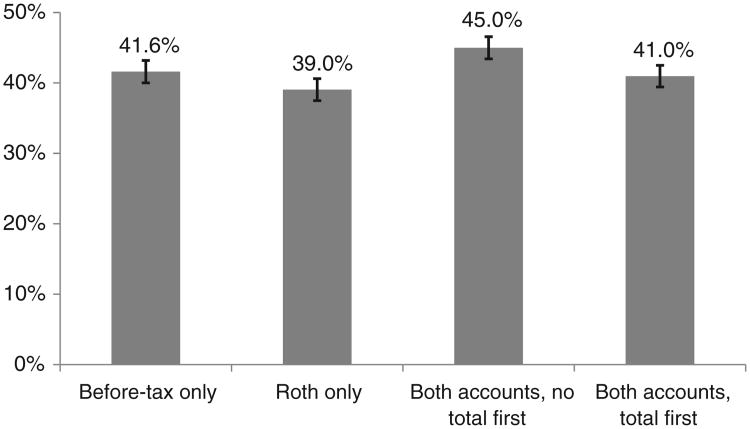

Fig. 4 shows the average total 401(k) contribution rate recommendations of respondents in each arm of the survey. Despite the elimination of asset shifting and substitution effects in the survey scenario, respondents recommend only a slightly lower contribution rate in the Roth-only condition than in the before-tax-only condition. The average recommended before-tax contribution rate is 11.2%, and the average recommended Roth contribution rate is 10.7% (p-value of difference = 0.002).12 In the very likely scenario that Jack and Cindy's marginal income tax rate currently and in retirement is greater than 4.5%, respondents in the Roth-only condition are in fact delivering more retirement consumption and less current consumption to Jack and Cindy than are respondents in the before-tax-only condition.13 Since Jack and Cindy want a flat consumption path, moving current and retirement consumption in opposite directions cannot be the optimal solution. Respondents should either deliver weakly more consumption in both periods or strictly less consumption in both periods.

Fig. 4.

Average total contribution rate recommendations. Error bars show 95% confidence intervals.

Why doesn't the recommended contribution rate fall more in the Roth-only condition relative to the before-tax-only condition? One possibility is that the recommended asset allocation changes greatly between the before-tax-only and Roth-only conditions. According to the Euler equation, the optimal savings rate for an investor depends on the risk of her portfolio, so a dramatically different asset allocation could rationalize an effective savings rate that is much higher in the Roth-only condition. Fig. 5 shows that although respondents do recommend statistically different equity allocations between the two conditions (p-value of difference = 0.025), the gap is economically small: 42% in the before-tax-only group versus 39% in the Roth-only group.14

Fig. 5.

Average equity allocation recommendations. Error bars show 95% confidence intervals.

A more likely possibility is that the insensitivity of contributions across conditions is driven by ignorance and/or neglect of the 401(k) tax rules. Table 6 reports how many survey respondents are able to correctly answer the four questions on the tax treatment of 401(k) contributions and withdrawals, as a percent of those who were asked each question. Only 49% correctly respond that making before-tax 401(k) contributions decreases taxable income in the year of the contribution, and only 46% correctly respond that making Roth 401(k) contributions does not affect taxable income in the year of the contribution. Because these two questions were multiple-choice questions with three options (corresponding to the contribution increasing taxable income, not affecting taxable income, and decreasing taxable income, plus an “I don't know” option), randomly guessing would have produced the correct answer 33% of the time. Knowledge of how withdrawals are taxed in retirement is also low. When asked these free-response questions, only 33% can correctly identify how much of a $150,000 before-tax withdrawal at age 65 would be taxable income, and only 25% can correctly answer an analogous question about a $150,000 Roth withdrawal at age 65.15 About half of respondents admit that they do not know the answer to each of the withdrawal questions, which makes it unlikely that they could condition their contribution rate recommendations on the tax treatment of withdrawals.

Table 6.

Knowledge of 401(k) taxation rules.

This table shows how many respondents gave the correct answer or indicated they did not know the correct answer for each question about 401(k) taxation rules, as a percent of the total number of respondents who were asked each question.

| Percent correct | Percent who answered “I don't know” | N | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Suppose a person with a $100,000 salary started making before-tax 401(k) contributions this calendar year without changing any of her contributions to other retirement savings accounts. What effect would this have on her taxable income this year? | 49% | 14% | 3609 |

| Suppose a person with a $100,000 salary started making Roth 401(k) contributions this calendar year without changing any of her contributions to other retirement savings accounts. What effect would this have on her taxable income this year? | 46% | 19% | 3499 |

| Suppose you made $100,000 in before-tax contributions to a 401(k) over the course of your working life. Your 401(k) investments went up in value, so that at age 65, your before-tax contributions are worth $150,000. You withdraw the entire $150,000 balance from your 401(k) at once at age 65. How much of this $150,000 withdrawal is taxable income in the year of the withdrawal? | 33% | 52% | 3467 |

| Suppose you made $100,000 in Roth contributions to a 401(k) over the course of your working life. Your 401(k) investments went up in value, so that at age 65, your Roth contributions are worth $150,000. You withdraw the entire $150,000 balance from your 401(k) at once at age 65. How much of this $150,000 withdrawal is taxable income in the year of the withdrawal? | 25% | 49% | 3425 |

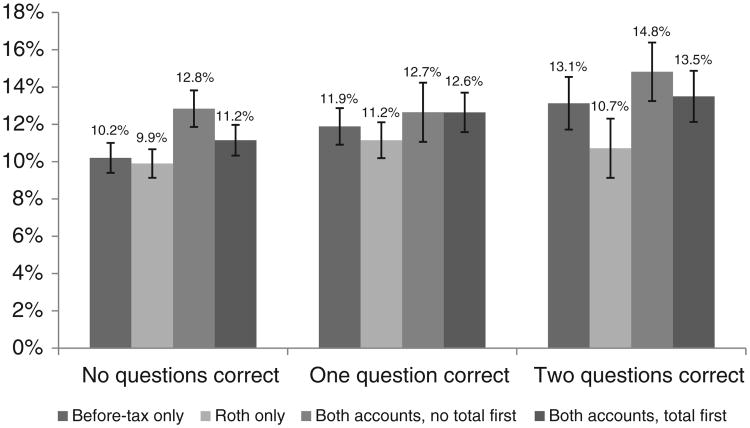

In Fig. 6, we categorize respondents by the number of tax knowledge questions answered correctly and show each group's average total contribution rate recommendation in each of the four survey conditions. Recall that each respondent answered only two randomly selected tax knowledge questions. Forty-five percent answered neither of their two questions correctly; 33% answered only one question correctly; and 22% answered both questions correctly. We see that the drop in the recommended contribution rate as we move from the before-tax-only condition to the Roth-only condition is 0.38% and insignificant (p = 0.143) among those who answered zero questions correctly, 0.54% and marginally significant (p = 0.061) among those who answered exactly one question correctly, and 0.85% and significant (p = 0.025) among those who answered two questions correctly. Although we do not have statistical power to reject the hypothesis that these three contribution rate differences are equal to each other, this pattern suggests that tax ignorance may play an important role in the insensitivity of contribution rates to the tax treatment of 401(k) balances.

Fig. 6.

Average total contribution rate recommendations by knowledge of 401(k) tax rules. Error bars show 95% confidence intervals.

Even the 0.85% of pay decrease exhibited by the most knowledgeable group is a modest one, implying that current consumption falls and retirement consumption rises if the marginal income tax rate in both periods is greater than 6.9%.16 The modest drop may be due to those who know the relevant tax rules still neglecting to take them into account. But it is at least partly also due to knowledge being imperfect even in the most knowledgeable group. A more stringent test of knowledge is being able to answer the free-response tax questions correctly.17 Fig. 7 shows the contribution rates recommended by respondents who were asked the two free-response questions. The 16% who answered both questions correctly recommended a much larger contribution rate drop (2.41%, p = 0.030) when moving from the before-tax-only condition to the Roth-only condition, and this drop is marginally significantly different (p = 0.082) from the 0.30% drop among those who answered neither free-response question correctly.18

Fig. 7.

Average total contribution rate recommendations by knowledge of 401(k) tax rules in free-response questions. Error bars show 95% confidence intervals.

Because any employer that offers a Roth 401(k) is required by law to also offer a before-tax 401(k), the experimental condition where both before-tax and Roth accounts are available most closely corresponds to the situation actually faced by employees hired after a Roth 401(k) introduction. The third bar in Fig. 4 shows that when the before-tax and Roth contribution rates are elicited in the usual way – without first asking respondents what the sum of the contribution rates will be – the average recommended total contribution rate is 13.1%, which is substantially higher than the recommended contribution rate in the two single-account conditions (p-value of difference with respect to either condition = 0.000).19 This is puzzling because having both accounts available instead of only one weakly increases the after-tax rate of return on saving, so a couple like Jack and Cindy whose intertemporal elasticity of substitution is zero should weakly decrease its savings rate when moving from one account to two. Having both the before-tax and Roth accounts also allows one to diversify tax risk by contributing to both accounts. A decrease in investment risk is an additional force that should decrease saving for an agent with an intertemporal elasticity of substitution less than one (Weil, 1990).

A very different portfolio allocation in the both-accounts condition could potentially explain a higher contribution rate. But in Fig. 5, the recommended equity allocation of 45% in the both-accounts condition, although statistically different from the 42% allocation in the before-tax-only condition (p-value of difference = 0.003) and the 39% allocation in the Roth-only condition (p-value of difference = 0.000), is only slightly higher in economic terms. Neither is confusion about taxation a likely explanation: Figs. 6 and 7 indicate that the disparity between the recommended contribution rate in the both-accounts condition and the single-account conditions is not smaller among the most tax-knowledgeable respondents.

In a pilot survey we ran before the survey reported in this paper, we observed that recommended total contributions rose in the both-accounts condition when contribution rates were elicited as above. We hypothesized that this rise was caused by the psychological phenomenon of partition dependence. Fox, Ratner, and Lieb (2005) show that since people have a bias towards allocating an equal amount to every discrete option presented to them, choices are sensitive to how the action space is partitioned.20 If current consumption is a category that respondents are considering when making their contribution decisions, then a bias towards equal allocation would reduce consumption when the three partitions {current consumption, before-tax contribution, Roth contribution} are considered relative to when only two partitions, {current consumption, before-tax contribution} or {current consumption, Roth contribution}, are considered.

One way Fox et al. (2005) demonstrate partition dependence is by running an experiment where participants were asked to divide $2 among one international charity and four local charities. Participants who were asked to first decide how much to allocate internationally versus locally before dividing the local allocation among the four local charities chose to give 52% to the international charity, whereas participants who were not prompted to follow this hierarchical procedure chose to give 21% to the international charity. In the context of savings, a study on very low income day laborers in India by Soman and Cheema (2011) finds that asset accumulation is significantly higher when individuals partition their savings into two “accounts” (envelopes in their experiment) rather than a single account because individuals spend less out of their savings when it is partitioned.

The results of these experiments motivated us to ask half of the respondents in our both-accounts condition to recommend a total 401(k) contribution rate before deciding how contributions would be split between before-tax and Roth contributions. We predicted that prompting respondents to think of the partitions {current consumption, total contribution} would elicit a total 401(k) contribution rate that is similar to the 401(k) contribution rate in the single-account conditions and lower than the total contribution rate when respondents face the three partitions {current consumption, before-tax contribution, Roth contribution}.

Indeed, Fig. 4 shows that the average total contribution rate recommendation in the both-accounts condition when the total contribution rate was elicited first is 11.4%, which is not significantly different from the before-tax-only recommendation of 11.2% (p = 0.166), although it is significantly different from the Roth-only recommendation of 10.7% (p = 0.000).21 The 41% equity allocation (Fig. 5) in this both-accounts elicitation is not statistically different from the before-tax-only equity allocation of 42% (p = 0.565) or the Roth-only equity allocation of 39%(p = 0.087).Itappears that partition dependence can explain nearly all of the increase in the total contribution rate that occurs when moving from a single-account condition to the both-accounts condition with a one-stage elicitation. Because it is likely that most, if not all, of our sample companies that introduced a Roth use a one-stage elicitation for contribution rates, partition dependence may have played a role in our finding from the 401(k) administrative data that total contribution rates do not decline following Roth introduction.

The results from the survey experiment provide suggestive evidence on some of the mechanisms that determine contribution rates in a before-tax-only versus a before-tax and Roth environment, but we reiterate that there are many caveats in the interpretation of these results. Respondents are making hypothetical choices, and the context in which these choices are being made does not fully reflect the context in which actual 401(k) savings decisions are made. Further, although we tried to describe the scenario in the survey experiment in a way that shuts down asset shifting and substitution effects, we do not know how effectively this was done.

5. Conclusion

Comparing total 401(k) contribution rates of employees hired one year prior to Roth introduction to those of employees hired immediately after Roth introduction, we find no evidence that introducing a Roth 401(k) option decreases total 401(k) contribution rates. This means that the total amount of retirement consumption being purchased via the 401(k) increases after the Roth is made available. Our finding does not appear to be driven by the fact that a Roth introduction relaxes the effective 401(k) contribution limit, low employee take-up of the Roth option, or kinks in the budget set created by the employer match. Our survey experiment provides suggestive evidence that employee confusion about and neglect of the tax properties of Roth balances, along with partition dependence, prevent contribution rates from falling following a Roth introduction. Thus, governments may be able to increase after-tax private savings while holding the present value of taxes collected roughly constant by making savings non-deductible up front but tax exempt in retirement, rather than vice versa.

Whether governments should change the tax treatment of retirement savings in order to increase private savings is a matter we do not take up in this paper, although it is an important normative policy question. Indeed, there have been several proposals in the United States in recent years to either reduce or eliminate the tax deductibility of retirement savings. The right answer depends on many factors not addressed in this paper. For example, is the private savings rate too low? Would shifting savings from before-tax to Roth accounts increase the size of government by shifting tax revenue from the future into the present? Or would shifting tax revenue from the future into the present prompt the government to reduce its debt? We leave these questions for future research.

We should caution that the administrative data used in our analysis end in 2011, only a few years after the inception of Roth 401(k) accounts in 2006. Therefore, our results represent short-term effects and do not necessarily reflect the effects of Roth availability further in the future. Even though Roth IRAs have been available since 1998, awareness of the tax differences between before-tax and Roth 401(k) accounts may still be increasing over time. In addition, the sources of financial advice that individuals consult may offer progressively better recommendations about how to use Roth 401(k) accounts. Such changes could eventually make savings plan contributions more responsive to taxation.

Supplementary Material

Respondents in the before-tax-only condition saw the following text:

Jack and Cindy are married and have two children ages 2 and 4. They are both 30 years old and live in your neighborhood in rental housing. They don't expect to have any more kids. Jack earns $100,000 per year before taxes working as a computer programmer and expects to retire at age 65. He expects his income to grow at the rate of inflation (that is, the rate at which the cost of living index rises) for the rest of his working life. Cindy is staying at home to raise their children and doesn't expect to return to the workforce.

The only savings Jack and Cindy have right now is $5000 in a bank savings account. Jack's company offers a 401(k) retirement savings plan that has only a before-tax contribution option (it only accepts before-tax dollars). Jack's company does not make matching contributions to the 401(k). This 401(k) also has a special rule: It does not allow Jack to withdraw money from it for any reason before he is 59.5 years old, even if Jack leaves the firm. (In real life, 401(k) withdrawal rules are not as strict.)

Jack and Cindy need to decide how much to contribute to the plan and how to invest the contributions. Their financial goal is to have a material standard of living that does not change for the rest of their lives, even in retirement. If they do save anything over the next 12 months, they plan on doing that saving in Jack's 401(k). Please advise Jack and Cindy by recommending, to the best of your ability, a contribution amount and investment allocation. If you feel you need more information than we gave you, make whatever additional assumptions seem natural to you.

Footnotes

We thank Amy Finkelstein, James Poterba, Scott Weisbenner, Michelle White, the editor Wojciech Kopczuk, and two anonymous referees for helpful comments, as well as participants at the NBER TAPES, Boulders, and Summer Institute conferences, the ASSA meetings, and seminars at Harvard and the University of Miami. We thank Jonathan Cohen, Layne Kirshon, Luca Maini, Brendan Price, Michael Puempel, Alexandra Steiny, and Jane Wang for excellent research assistance. We also thank Aon Hewitt for providing the administrative data and Warren Cormier and the Boston Research Group for including our questions in their survey. We acknowledge financial support from the National Institute on Aging (grants R01AG021650 and P01AG005842), the Social Security Administration (grant FLR09010202-02 through RAND's Financial Literacy Center and grant 5RRC08098400-04-00 to the National Bureau of Economic Research as part of the SSA Retirement Research Consortium), and the Pershing Square Fund for Research on the Foundations of Human Behavior. The opinions and conclusions expressed are solely those of the authors and do not represent the opinions or policy of NIA, SSA, any agency of the Federal Government, or the NBER. The authors have, at various times in the last three years, been compensated to present academic research at events hosted by financial institutions that administer retirement savings plans. See the authors' websites for a complete list of outside activities

See de Bartolome (1995), Duflo et al. (2006), Bettinger et al. (2012), Chetty, Looney, and Kroft (2009), Finkelstein (2009), Jones (2010), and Chetty and Saez (2013) for other examples of tax neglect.

See also Whitehouse (1999).

A withdrawal is considered qualified if (i) the account has been held for at least five years and (ii) the account owner is either older than 59½, disabled, or deceased.

To see this, let m be the rate at which employee contributions are matched. The marginal pre-tax dollar can earn m match dollars if it is saved using a before-tax account, but only (1 − τ0)m match dollars if it is saved using a Roth or after-tax account (since τ0 dollars must be paid in taxes, thereby preventing the entire dollar from being contributed to the savings plan). The condition under which employees who have no probability of making a non-qualified withdrawal are better off contributing to the Roth rather than the before-tax account is more restrictive than it is without a match. With a match, the Roth is a better financial deal than contributing before-tax if and only if (1 − τ0)[1 + m(1 − τ1)] > (1 − τ1)(1 + m).

Specifically, one needs to contribute [(1 − τ1) + m(1 − τ1)] / [1 + m(1 − τ1)] dollars, which is less than 1 if τ1 > 0.

Month-end before-tax and after-tax contribution rates are missing in January 2006 for Company C. Month-end before-tax contribution rates are missing in April and June 2006 for Company F and in October 2007 for Company G. Month-end Roth contribution rates are missing in our data for the first few months after the Roth is introduced at the following firms: Company C (January to March 2006), Company F (January to April and June 2006), Company H (January to March 2006), and Company I (January to February 2009). We assign the first observed contribution rate after the missing period to prior missing month-ends unless the employee was not enrolled in the 401(k) at that month-end,inwhich case we assign a 0% contribution rate. Contribution rates for a newly enrolled employee are also sometimes missing for the first few months after his or her enrollment, in which case we perform a similar imputation. Almost all of these missing new-enrollee contribution rates occur between January and March 2006 in Company H.

Beshears et al. (2014) report that Roth 401(k) usage among employees who did not have a Roth option available when they were hired is less than half of that among employees who had a Roth option available from the beginning of their tenure, probably due to employee inertia. By focusing on new hires, we are looking for Roth effects in the population where they are likely to be the largest.

The small difference in average contribution rates in the first month of tenure is driven by the post-Roth cohort taking longer to enroll in the plan than the pre-Roth cohort. This delay would be expected if the addition of a Roth option increases the complexity of the savings plan participation decision (Huberman, Iyengar, and Jiang, 2004; Choi, Laibson and Madrian, 2009; Beshears, Choi, Laibson and Madrian, 2013).

Appendix Table 1 shows the before-tax, after-tax, and Roth contribution rates separately for each hire cohort.

The match thresholds include the maximum contribution rate up to which employee contributions are matched, as well as lower contribution rates where the match rate changes. The latter category is relevant at Company J, which has a tiered match schedule. The analysis in the main text ignores the fact that at some companies, the match does not take effect until the employee has at least one year of tenure. The results are qualitatively unchanged if we instead classify zero employees at these companies as being at a budget set kink.

This randomization was independent of the survey condition.

We requested that contribution rate recommendations be entered in units such that “10” would correspond to 10%. A small number of people entered contribution rates between 0 and 1, probably because they misunderstood the units. We multiplied these responses by 100.

The minimum marginal tax rate is derived by solving for τ1 in the inequality 0.112Y(1 + r)(1 − τ1) < 0.107Y(1 + r), where the left-hand side is consumption delivered in the future by saving 11.2% of income in a before-tax account, the right-hand side is consumption delivered in the future by saving 10.7% of income in a Roth account, Y is income, r is the rate of return, and τ1 is the tax rate in retirement. This yields τ1 > 0.045. Similarly, we solve for τ0 in the inequality (1 − 0.112)Y(1 − τ0) > Y(1 − τ0) − 0.107Y, where the left-hand side is consumption today with a savings rate of 11.2% of income in a before-tax account, the right-hand side is consumption today when saving 10.7% of income in a Roth account, and τ0 is the tax rate today. This yields τ0 > 0.045.

As we did for contribution rate recommendations, we multiply the small number of equity allocation responses between 0 and 1 by 100.

We counted the following responses to the before-tax withdrawal question as correct: 150,000;100 (we assumed the respondent meant percent); 150 (we assumed the respondent was answering in thousands); 1,500,000 and 15,000,000 (we assumed the respondent mistyped extra zeros).

This number is derived by solving for τ1 in the inequality 0.122Y(1 + r)(1 − τ1) < 0.114Y(1 + r), where the left-hand side is consumption delivered in the future by saving 11.2% of income in a before-tax account, the right-hand side is consumption delivered in the future by saving 10.7% of income in a Roth account, Y is income, r is the rate of return, and τ1 is the tax rate in retirement. This yields τ1 > 0.069. Similarly, we solve for τ0 in the inequality (1 − 0.122)Y(1 − τ0)> Y(1 − τ0) − 0.114Y, where the left-hand side is consumption today with a savings rate of 11.2% of income in a before-tax account, the right-hand side is consumption today when saving 10.7% of income in a Roth account, and τ0 is the current tax rate. This yields τ0 > 0.069.

We thank the editor, Wojciech Kopczuk, for suggesting this analysis.

With a 2.4% drop, current consumption falls and retirement consumption rises if the marginal income tax rate in both periods is greater than 18.3%, which is still reasonably likely for Jack and Cindy.

The 13.1% average total contribution rate is comprised of an 8.1% average before-tax contribution rate and a 5.0% average Roth contribution rate.

Diversification biases do not necessarily cause people to allocate exactly equal amounts to each option, but rather bias their choices towards an equal allocation.

The 11.4% average total contribution rate is comprised of a 7.5% average before-tax contribution rate and a 4.0% average Roth contribution rate.

Appendix A. Supplementary data: Supplementary data to this article can be found online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2015.09.007.

References

- Benartzi Shlomo, Thaler Richard H. Heuristics and biases in retirement savings behavior. J Econ Perspect. 2007;21:81–104. [Google Scholar]

- Beshears John, Choi James J, Laibson David, Madrian Brigitte C. The importance of default options for retirement savings outcomes: evidence from the United States. In: Kay Stephen J, Sinha Tapen., editors. Lessons from Pension Reform in the Americas. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2008. pp. 59–87. [Google Scholar]

- Beshears John, Choi JamesJ, Laibson David, Madrian BrigitteC. Simplification and saving. J Econ Behav Organ. 2013;95:130–145. doi: 10.1016/j.jebo.2012.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beshears John, Choi JamesJ, Laibson David, Madrian BrigitteC. The effect of providing peer information on retirement savings decisions. J Financ. 2015;70:1161–1201. doi: 10.1111/jofi.12258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beshears John, Choi James J, Laibson David, Madrian Brigitte C. Who uses the Roth 401(k), and how do they use it? In: Wise David A., editor. Discoveries in the Economics of Aging. University of Chicago Press; Chicago: 2014. pp. 411–440. [Google Scholar]

- Bettinger EricP, Long BridgetTerry, Oreopoulos Philip, Sanbonmatsu Lisa. The role of application assistance and information in college decisions: results from the H&R Block FAFSA experiment. Q J Econ. 2012;127:1205–1242. [Google Scholar]

- Brown JeffreyR, Ivkovic Zoran, Smith PaulA, Weisbenner Scott. Neighbors matter: causal community effects and stock market participation. J Financ. 2008;63:1509–1531. [Google Scholar]

- Chalmers John, Reuter Jonathan. What is the impact of financial advisors on retirement portfolio choices and outcomes? NBER Working Paper. 2012;18158 [Google Scholar]

- Chetty Raj, Saez Emmanuel. Teaching the tax code: earnings responses to an experiment with EITC recipients. Am Econ J Appl Econ. 2013;5:1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Chetty Raj, Looney Adam, Kroft Kory. Salience and taxation: theory and evidence. Am Econ Rev. 2009;99:1145–1177. [Google Scholar]

- Choi James J, Laibson David, Madrian Brigitte C, Metrick Andrew. Defined contribution pensions: plan rules, participant decisions, and the path of least resistance. In: Poterba James., editor. Tax Policy and the Economy. Vol. 16. 2002. pp. 67–114. [Google Scholar]

- Choi James J, Laibson David, Madrian Brigitte C, Metrick Andrew. For better or for worse: default effects and 401(k) savings behavior. In: Wise David., editor. Perspectives in the Economics of Aging. University of Chicago Press; Chicago: 2004. pp. 81–121. [Google Scholar]

- Choi James J, Laibson David, Madrian Brigitte C. Reducing the complexity costs of 401(k) participation: the case of quick enrollment. In: Wise David A., editor. Developments in the Economics of Aging. University of Chicago Press; Chicago: 2009. pp. 57–82. [Google Scholar]

- Choi James J, Haisley Emily, Kurkoski Jennifer, Massey Cade. Small cues change savings choices. NBER Working Paper. 2013;17843 doi: 10.1016/j.jebo.2017.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Bartolome CharlesAM. Which tax rate do people use: average or marginal? J Public Econ. 1995;56:79–96. [Google Scholar]

- Duflo Esther, Saez Emmanuel. Participation and investment decisions in a retirement plan: the influence of colleagues' choices. J Public Econ. 2002;85:121–148. [Google Scholar]

- Duflo Esther, Saez Emmanuel. The role of information and social interactions in retirement plan decisions: evidence from a randomized experiment. Q J Econ. 2003;118:815–842. [Google Scholar]

- Duflo Esther, Gale William, Liebman Jeffrey, Orszag Peter, Saez Emmanuel. Savings incentives for low- and middle-income families: evidence from a field experiment with H&R block. Q J Econ. 2006;121:1311–1346. [Google Scholar]

- Engelberg JosephE, Parsons ChristopherA. The causal impact of media in financial markets. J Financ. 2011;66:67–97. [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein Amy. E-ztax: tax salience and tax rates. Q J Econ. 2009;124:969–1010. [Google Scholar]

- Fox CraigR, Ratner RebeccaK, Lieb DanielS. How subjective grouping of options influences choice and allocation: diversification bias and the phenomenon of partition dependence. J Exp Psychol Gen. 2005;134:538–551. doi: 10.1037/0096-3445.134.4.538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holden Sarah, Vanderhei Jack. Contribution behavior of 401(k) plan participants. Investment Company Institute Perspective. 2001;7(4) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong Harrison, Kubik JeffreyD, Stein JeremyC. Social interaction and stock-market participation. J Financ. 2004;59:137–163. [Google Scholar]

- Huberman Gur, Iyengar Sheena S, Jiang Wei. How much choice is too much? Contributions in 401(k) retirement plans. In: Mitchell Olivia S, Utkus Steven P., editors. Pension Design and Structure: New Lessons from Behavioral Finance. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2004. pp. 83–96. [Google Scholar]

- Ibbotson Roger, Xiong James, Kreitler RobertP, Kreitler CharlesF, Chen Peng. National savings rate guidelines for individuals. J Financ Plan. 2007;20(4):50–61. [Google Scholar]

- Jones Damon. Information, preferences, and public benefit participation: experimental evidence from the advance EITC and 401(k) savings. Am Econ J Appl Econ. 2010;2:147–163. [Google Scholar]

- Plan SponsorCouncilofAmerica. PSCA's annual survey shows company contributions are bouncing back. [accessed March 29, 2013];2012 Press Release October 11 http://www.psca.org/psca-s-annual-survey-shows-company-contributions-are-bouncing-back.

- Robalino David A, Whitehouse Edward, Mataoanu Anca N, Musalem Alberto R, Sherwood Elisabeth, Sluchynsky Oleksiy. Pensions in the Middle East and North Africa: time for change. Washington D.C.: The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Soman Dilip, Cheema Amar. Earmarking and partitioning: increasing saving by low-income households. J Mark Res. 2011;48(S1):S14–S22. [Google Scholar]

- Tetlock PaulC. Giving content to investor sentiment: the role of media in the stock market. J Financ. 2007;62:1139–1168. [Google Scholar]

- Tversky Amos, Kahneman Daniel. Judgment under uncertainty: heuristics and biases. Science. 1974;185(4157):1124–1131. doi: 10.1126/science.185.4157.1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weil Philippe. Nonexpected utility in macroeconomics. Q J Econ. 1990;105:29–42. [Google Scholar]

- Whitehouse Edward. The tax treatment of funded pensions. 9910 The World Bank; Social Protection Discussion Paper: 1999. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.