Abstract

We conducted a meta-analysis of observational studies to examine the hypothesized association between breast cancer and antihypertensive drug (AHT) use. Fixed- or random- effect models were used to calculate pooled risk ratios (RRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for all AHTs and individual classes (i.e., angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, [ACEi]; angiotensin-receptor blockers, [ARBs]; calcium channel blockers, [CCBs]; beta-blockers, [BBs], and diuretics). Twenty-one studies with 3,116,266 participants were included. Overall, AHT use was not significantly associated with breast cancer risk (RR = 1.02, 95% CI: 0.98-1.06), and no consistent association was found for specific AHT classes with pooled RRs of 1.02 (95% CI: 0.96-1.09) for BBs, 1.07 (95% CI: 0.99-1.16) for CCBs, 0.99 (95% CI: 0.93-1.05) for ACEi/ARBs, and 1.05 (95% CI: 0.99-1.12) for diuretics. When stratified by duration of use, there was a significantly reduced breast cancer risk for ACEi/ARB use ≥10 years (RR = 0.80, 95% CI: 0.67-0.95). Although there was no significant association between AHT use and breast cancer risk, there was a possible beneficial effect was found for long-term ACEi/ARB. Large, randomized controlled trials with long-term follow-up are needed to further test the effect of these medications on breast cancer risk.

Keywords: antihypertensive drug, breast cancer, meta-analysis, cancer prevention, epidemiology

INTRODUCTION

Hypertension is a highly prevalent condition worldwide, affecting more than one billion individuals and causing 9.4 million deaths annually [1]. Antihypertensive drugs (AHTs) are commonly prescribed to help prevent detrimental outcomes of hypertension including stroke, coronary artery disease, and heart failure. It is estimated that AHT consumption has nearly doubled in OECD countries from 2000 to 2011. In the United States alone, the number of filled prescriptions reached 678.2 million in 2010 [2]. Despite their increasing use by patients with cardiovascular-related conditions, the noncardiovascular effects of AHTs remain unclear. Indeed, the carcinogenic potential of AHT has long been under scrutiny. During the past two decades, nearly all AHT classes have been reported to increase the risk of total cancer [3], as well as renal cancer [4], glioma [5], and epithelial ovarian cancer [6].

Breast cancer is the most common form of cancer and the second leading cause of cancer-related death among women worldwide [7]. There has been growing interest in the relationship between AHT use and breast cancer risk since the 1990s when Heinonen et al reported the results of a case-control study implicating rauwolfia derivatives in increasing breast cancer risk among women older than 50 [8]. Following this discovery, numerous observational studies examined the association between major AHT classes and breast cancer risk, but the results have been conflicting and inconsistent. Some groups [9–12] found that use of beta blockers (BBs), calcium channel blockers (CCBs), or diuretics was positively associated with breast cancer risk, but most [2, 13–24] observed no relationships. In addition, evidence for angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers (ACEi/ARBs) is also inconsistent, with some studies [2, 9, 12, 14, 16, 18, 20, 22, 25, 26] suggesting that their use is not associated with breast cancer risk, and others [23, 27] reporting increased or decreased risk.

Thus, given the widespread use of AHTs and the continued uncertainty regarding their effects on breast cancer incidence, we carried out a comprehensive meta-analysis to determine if there is an association of AHT use, including overall and different classes, with breast cancer risk based on all available observational studies.

RESULTS

Literature search

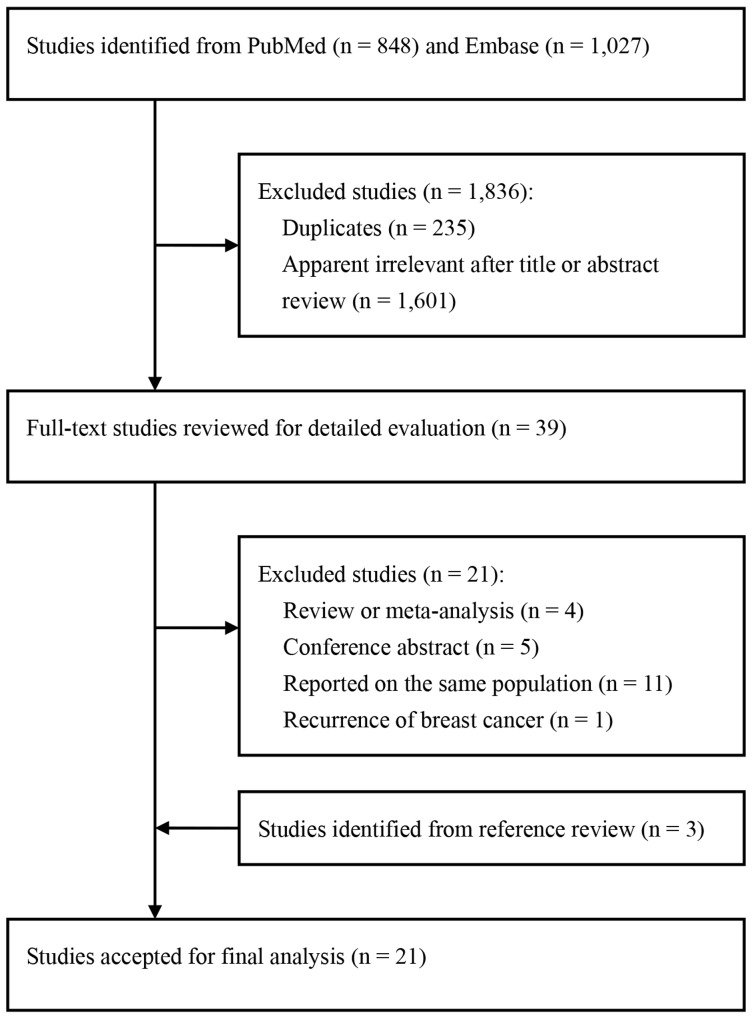

A total of 1,875 potentially eligible studies were identified during the initial search. After removing the duplicates and reviewing the titles or abstracts, 1,836 studies were deemed ineligible. Among the 39 articles for full-text review, 21 were further excluded for the following reasons: review or meta-analysis [32–35]; conference abstracts [36–40]; duplicate reports from the same study population [41–50]; or outcome was breast cancer recurrence [51]. Three additional articles [13, 14, 18] were included from the reference review. Finally, a total of 21 studies [2, 9–13, 15–27, 52, 53] published from 1996 to 2016 were included. The study selection process is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Flow chart of study selection.

Study characteristics

A list of details abstracted from the 21 included studies is provided in Table 1. All studies were published in English. Nine were prospective cohort studies, and 12 were case-control studies. Eleven studies were conducted in the United States, eight in Europe, one in Canada, and one in Taiwan. The sample sizes of the included studies ranged from 654 to 2,300,000, with a total of 3,167,020 participants, and the number of breast cancer cases varied from 31 to 58,000, with a total of 102,054. Of those studies, 11 provided results for BBs, 13 for CCBs, 13 for ACEi/ARBs, and 11 for diuretics. Drug use assessments were not consistent between studies; most used questionnaires and prescription database reviews. Case ascertainment was based on cancer registries or medical records in all studies. The adjusted covariates in individual studies differed, and most risk estimates were adjusted for age, body mass index, alcohol intake, and hormone replacement therapy use. Quality scores according to the Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale varied from 5 to 9 points, with a median of 7.14, indicating high quality of the studies included in the meta-analysis.

Table 1. Characteristics of observational studies of antihypertensive drug and breast cancer included in this meta-analysis.

| Author, year | Location | Study period/ follow-up (yrs) | Age (yrs) | No. of cases/ participants | Exposure variables | Exposure assessment | Case ascertainment | Adjustment for covariates | Quality score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prospective studies | |||||||||

| Pahor et al [13], 1996 | USA | 1988-1992/3.7 | ≥71 | 31/3,256 | CCBs | Self-administered questionnaire | Cancer registry | Age, race, hospitalizations, smoking, alcohol intake, oestrogen use, heart disease | 7 |

| Fryzek et al [16], 2006 | Denmark | 1990-2002/5.7 | 50–67 | 264/49,950 | AHT, CCBs, BBs, ACEi/ARBs, and Diuretics | Prescription database | Cancer registry | Age, calendar year, age at first birth, parity, HRT, NSAID use | 8 |

| Van Der Knaap et al [25], 2008 | Netherlands | 1989-2004/9.6 | ≥55 | 142/4,710 | ACEi/ARBs | Standard questionnaire | Cancer registry | Age, BMI, calendar year, physical activity, age at menarche and menopause, number of children, HRT, NSAID use, hypertension, diabetes, heart disease | 8 |

| Largent, et al [20], 2010 | USA | 1995-2006/10 | 52.8 | 5,865/188,291 | AHT, CCBs, ACEi, and Diuretics | Self-administered questionnaire | Cancer registry | Age, BMI, race, physical activity, smoking, diabetes, drinking, age at first birth, menopausal status, number of children, breastfeeding, HRT, family history of breast cancer, hysterectomy | 7 |

| Biggar et al [10], 2013 | Denmark | 1995-2010 | 62.6 | 58,000/2,300,000 | Spironolactone | Prescription database | Cancer registry | Age, calendar year | 6 |

| Saltzman et al [22], 2013 | USA | 1989-1993 | ≥65 | 188/3,201 | AHT, CCBs, BBs, ACEi, and Diuretics | Self-administered questionnaire | Cancer registry | Age, income, waist-hip ratio, alcohol intake, age at menopause | 7 |

| Devore et al [23], 2015 | USA | 1988-2012 | 25-55 | 10,012/210,641 | AHT, CCBs, BBs, ACEi, and Diuretics | Questionnaire | Medical records | Age, BMI, physical activity, height, shift work history, smoking, alcohol intake, age at menarche, menopause and first birth, parity, menopausal status, oral contraceptive use, HRT, family history of breast cancer, history of benign breast disease | 8 |

| Azoulay et al [24], 2016 | UK | 1995-2010/5.7 | ≥18 | 4,520/273,152 | CCBs | Prescription database | Cancer registry | Age, BMI, calendar year, smoking, alcohol intake, oral contraceptive use, HRT use, NSAID use, aspirin, statins, hysterectomy, previous cancer | 8 |

| Wilson et al [53], 2016 | USA | 2003-2009/5.3 | 35-74 | 1,965/50,754 | AHT, CCBs, BBs, ACEi/ARBs, and Diuretics | Standard questionnaire | Medical records | Age, BMI, race, physical activity, smoking, age at menarche, parity, menopausal status, HRT and statins use | 9 |

| Retrospective studies | |||||||||

| Rosenberg et al [52], 1998 | USA | 1976-1996 | 40-69 | 2,893/6,641 | CCBs, BBs, and ACEi | Standard questionnaire | Medical records | Age, BMI, calendar year, smoking, alcohol intake, age at menarche, age at first birth, parity, age at menopause, oral contraceptive use, HRT use, family history of breast cancer, history of benign breast disease | 8 |

| Li et al [12], 2003 | USA | 1997-1999 | 65-79 | 975/1,982 | AHT, CCBs, BBs, ACEi, and Diuretics | Standard questionnaire | Cancer registry | Age | 6 |

| Gonzalez-Perez et al [15], 2004 | UK | 1995-2001 | 30-79 | 3,780/23,780 | AHT, and BBs | Prescription database | Medical records | Age, BMI, calendar year, smoking, alcohol intake, HRT use, use of other AHT, hypertension, prior breast lump | 8 |

| Largent et al [11], 2006 | USA | 1994-1995 | 50–75 | 523/654 | Diuretics | Self-administered questionnaire | Cancer registry | Age, BMI, education, smoking, alcohol intake, age at first birth, menopausal status, diabetes, family history of breast cancer | 6 |

| Davis et al [17], 2007 | USA | 1992-1995 | 20–74 | 600/1,247 | CCBs, and BBs | Telephone interview | Cancer registry | Smoking, alcohol intake, age at first birth, parity, oral contraceptive use, HRT, family history of breast cancer, hysterectomy, ever upper gastrointestinal series | 5 |

| Assimes et al [18], 2008 | Canada | 1978-1988 | 71.8 | 1,623/17,853 | CCBs, BBs, and ACEi/ARBs | Prescription database | Cancer registry | Age, hypertension, diabetes, heart and chronic lung disease, cerebrovascular arterial disease, migraine, hyperthyroid, scleroderma, use of other AHT, | 6 |

| Coogan et al [19], 2009 | USA | 1976-2007 | 18-79 | 5,989/11,493 | Diuretics | Standard questionnaire | Medical records | BMI, race, education, alcohol intake, parity, menopausal status, oestrogen and oral contraceptive use | 8 |

| Azoulay et al [26], 2012 | UK | 1995-2010/6.4 | 63.4 | 11,312/124,331 | ACEi/ARBs | Prescription database | Cancer registry | BMI, smoking, alcohol intake, diabetes, oral contraceptive, HRT, hysterectomy, previous cancer, use of NSAID, aspirin, and statins | 7 |

| Mackenzie et al [21], 2012 | UK | 1987-2010/4.1 | ≥55 | 28,032/83,993 | Spironolactone | Prescription database | Medical records | Age, BMI, calendar year, Townsend score, alcohol intake, oral contraceptive use, HRT, aspirin, finasteride, hypertension, diabetes, family history of breast cancer, history of benign breast disease, heart disease | 6 |

| Hallas et al [27], 2012 | Denmark | 2000-2005 | 69.4 | 19,947/332,623 | ACEi/ARBs | Prescription database | Cancer registry | Oral contraceptive use, HRT use, NSAID use, aspirin, statins, finasteride, hypertension, diabetes, heart disease, inflammatory bowel disease, chronic lung and kidney disease | 7 |

| Li et al [2], 2013 | USA | 2000-2008 | 55–74 | 1,960/2,851 | AHT, CCBs, BBs, ACEi/ARBs, and Diuretics | Standard questionnaire | Cancer registry | Age, calendar year, race, alcohol intake | 7 |

| Chang et al [9], 2016 | Taiwan | 2001-2011/9.9 | ≥55 | 9,397/46,985 | DiCCBs, BBs, and ACEi/ARBs | Prescription database | Cancer registry | Socioeconomic status, Charlson’s index, number of hospitalizations and outpatient visits, hospital admission length, HRT use, aspirin, statins, fibrates, diuretics, human insulin, diabetes, heart disease, chronic kidney, liver, and lung disease, depression, cerebrovascular arterial disease, number of lipid measurements and mammography | 8 |

AHT, antihypertensive drug; ACEi, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; ARBs, angiotensin receptor blockers; BBs, beta blockers; BMI, body mass index; CCBs, calcium channel blockers; DiCCBs, dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers; HRT, hormone replacement therapy; NSAID, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; UK, United Kingdom.

Association between overall AHT use and breast cancer risk

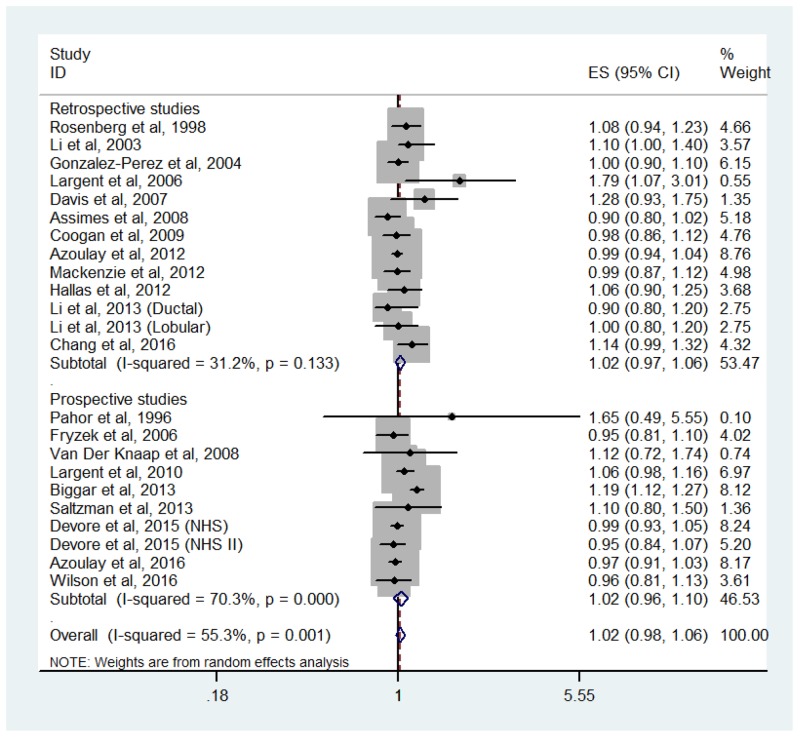

Twenty-one epidemiologic studies (twelve retrospective and nine prospective) presented results on use versus nonuse of AHTs and breast cancer risk. The pooled RR was 1.02 (95% CI: 0.98-1.06), with moderate heterogeneity among studies (Pheterogeneity = 0.001, I2 = 55.3%; Figure 2). When stratified by study design, no significant association was found among retrospective studies (RR = 1.02, 95% CI: 0.97-1.06, Pheterogeneity = 0.133, I2 = 31.2%) or prospective studies (RR = 1.02, 95% CI: 0.96-1.10, Pheterogeneity = 0.000, I2 = 70.3%).

Figure 2. Forest plot of overall antihypertensive use and breast cancer risk.

CI, confidence interval; RR, relative risk.

Association between BB use and breast cancer risk

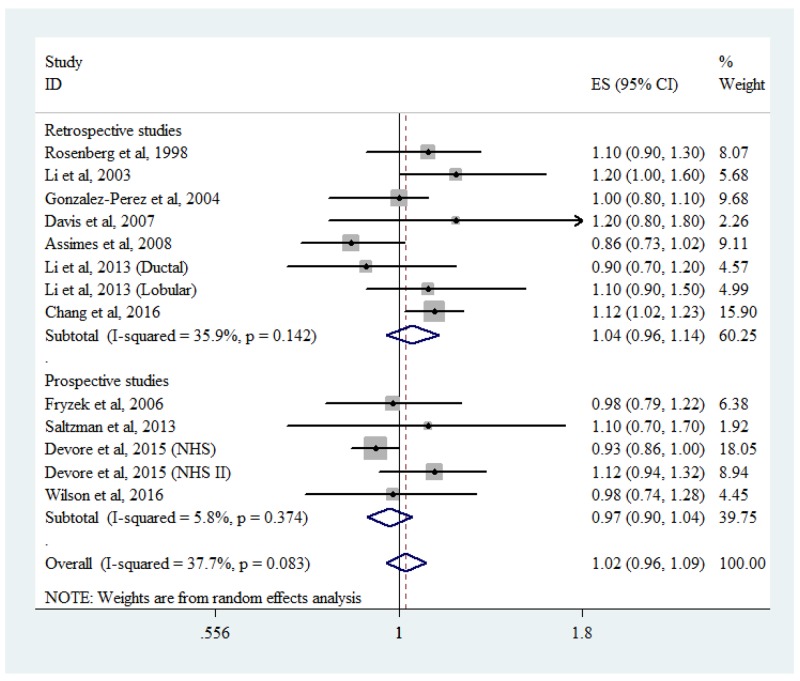

An association between breast cancer risk and BB use was reported in 11 studies [2, 9–12, 15–18, 22, 23, 52, 53], including 7 retrospective studies and 4 prospective studies. The pooled RR was 1.04 (95% CI: 0.96-1.14, Pheterogeneity = 0.142, I2 = 35.9%) for retrospective studies and 0.97 (95% CI: 0.90-1.04, Pheterogeneity = 0.374, I2 = 5.8%) for prospective studies. Combining the retrospective and prospective data, the pooled RR was 1.02 (95% CI: 0.96-1.09) with low heterogeneity among all the studies (Pheterogeneity = 0.083, I2 = 37.7%; Figure 3).

Figure 3. Forest plot of beta-blocker use and breast cancer risk.

CI, confidence interval; RR, relative risk.

Association between CCB use and breast cancer risk

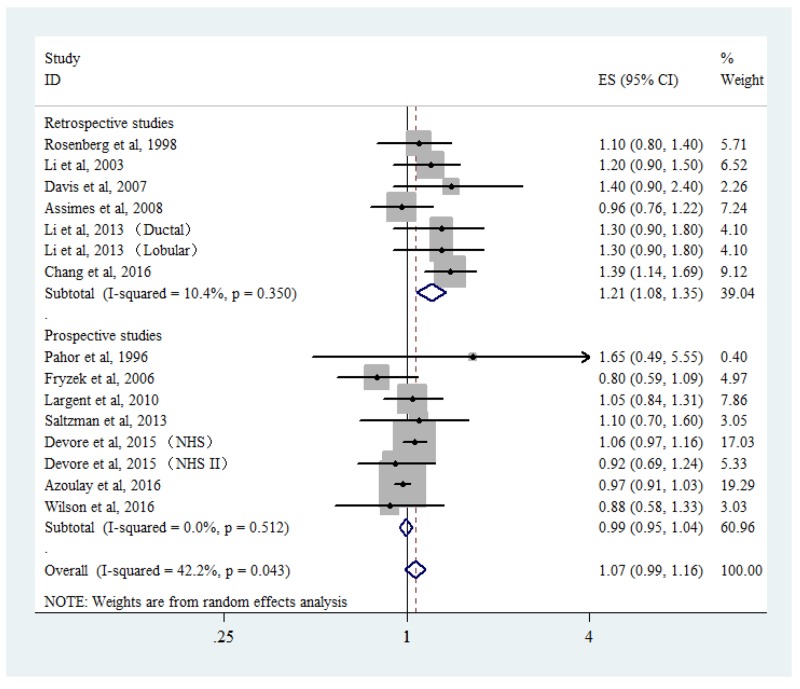

Six retrospective studies and seven prospective studies were included in the analysis for breast cancer risk among CCB users. Low heterogeneity (Pheterogeneity = 0.043, I2 = 42.2%) was found among all the studies. Random-effects pooled analysis suggested that CCB use was not associated with breast cancer risk (RR = 1.07, 95% CI: 0.99-1.16; Figure 4). Subgroup analysis showed a positive association among retrospective studies (RR = 1.21, 95% CI: 1.08-1.35, Pheterogeneity = 0.350, I2 = 10.4%) but not among prospective studies (RR = 0.99, 95% CI: 0.95-1.04, Pheterogeneity = 0.512, I2 = 0.0%).

Figure 4. Forest plot of calcium channel blocker use and breast cancer risk.

CI, confidence interval; RR, relative risk.

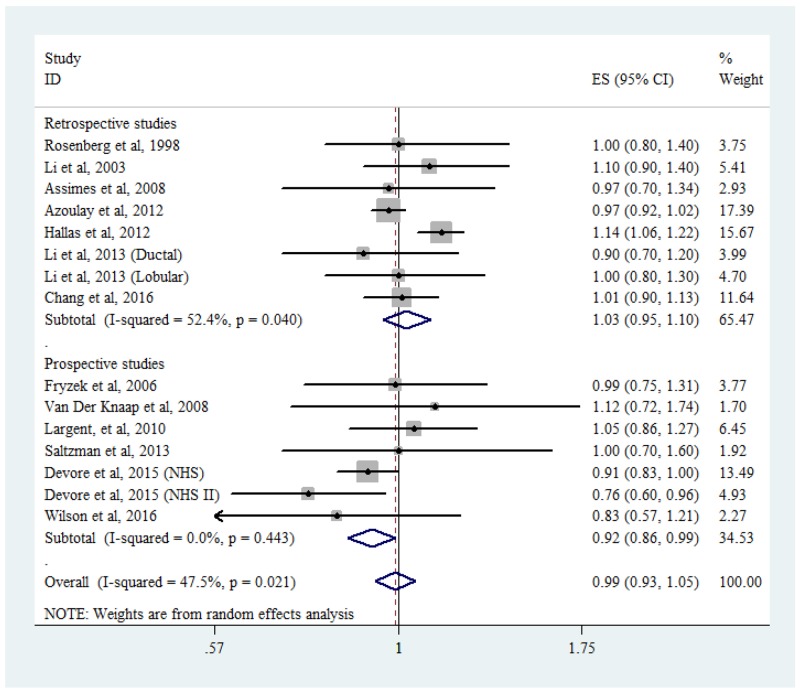

Association between ACEi/ARB use and breast cancer risk

Thirteen studies (seven retrospective and six prospective) examined the role of ACEi/ARB use on breast cancer risk. The results are shown in Figure 5. The pooled RRs comparing ACEi/ARB use and nonuse were 0.99 (95% CI: 0.93-1.05, Pheterogeneity = 0.021, I2 = 47.5%) for overall studies, 1.03 (95% CI: 0.95-1.10, Pheterogeneity = 0.040, I2 = 52.4%) for retrospective studies, and 0.92 (95% CI: 0.86-1.00, Pheterogeneity = 0.356, I2 = 9.3%) for prospective studies.

Figure 5. Forest plot of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin-receptor blocker use and breast cancer risk.

CI, confidence interval; RR, relative risk.

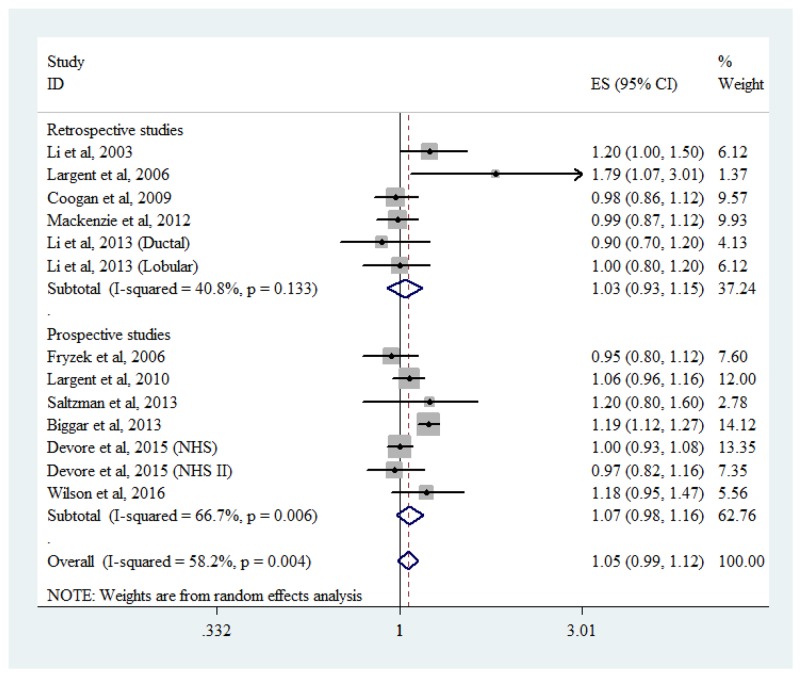

Association between diuretic use and breast cancer risk

Eleven studies provided information on diuretics use (Figure 6). Compared with nonuse, the pooled RR for diuretics was 1.05 (95% CI: 0.99-1.12). There was moderate heterogeneity across studies (Pheterogeneity = 0.004, I2 =58.2%). No significant link was found in retrospective studies (RR = 1.03, 95% CI: 0.93-1.15, Pheterogeneity = 0.133, I2 = 40.8%) or prospective studies (RR = 1.07, 95% CI: 0.98-1.16, Pheterogeneity = 0.006, I2 = 66.7%).

Figure 6. Forest plot of diuretic use and breast cancer risk.

CI, confidence interval; RR, relative risk.

Subgroup analyses

When stratifying by geographic region, we did not found any association between AHT use and breast cancer risk. There was also no association observed in either study quality score stratum. Stratification by time period of drug use (current, recent, or past) showed that exposure to any class of AHT did not alter breast cancer risk. However, in examining duration effects of medication use, a reduced risk of breast cancer was found for ACEi/ARB use for 10 years or longer (RR = 0.80, 95% CI: 0.67-0.95) but not in those observed for 5-10 years or fewer than 5 years. No statistically significant associations were seen for the other drug categories (Tables 2 and 3).

Table 2. Subgroup and sensitivity analyses of associations between use of overall AHT, BBs and CCBs and breast cancer risk.

| AHT | BBs | CCBs | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | n | RR (95% CI) | Pheterogeneity | I2 (%) | n | RR (95% CI) | Pheterogeneity | I2 (%) | n | RR (95% CI) | Pheterogeneity | I2 (%) |

| Total | 21 | 1.02(0.98-1.06) | 0.001 | 55.3 | 11 | 1.02(0.96-1.09) | 0.083 | 37.7 | 13 | 1.07(0.99-1.16) | 0.043 | 42.2 |

| Design | ||||||||||||

| Retrospective study | 12 | 1.02(0.97-1.06) | 0.133 | 23.5 | 7 | 1.04(0.96-1.14) | 0.142 | 35.9 | 6 | 1.21(1.08-1.35) | 0.350 | 10.4 |

| Prospective study | 9 | 1.02(0.96-1.10) | 0 | 70.3 | 4 | 0.97(0.90-1.04) | 0.374 | 5.8 | 7 | 0.99(0.95-1.04) | 0.512 | 0 |

| Geographic area | ||||||||||||

| America | 12 | 1.01(0.96-1.05) | 0.176 | 25.9 | 8 | 1.01(0.93-1.09) | 0.148 | 32.5 | 10 | 1.07(1.00-1.14) | 0.745 | 0 |

| Europe | 8 | 1.02(0.96-1.10) | 0 | 75.2 | 2 | 0.99(0.87-1.13) | 0.883 | 0 | 2 | 0.94(0.81-1.08) | 0.228 | 31.3 |

| Study quality score | ||||||||||||

| High (NOS score >6) | 15 | 1.00(0.97-1.02) | 0.766 | 0 | 8 | 1.03(0.96-1.09) | 0.167 | 30.3 | 10 | 1.06(0.97-1.16) | 0.034 | 47.4 |

| Low (NOS score ≤6) | 6 | 1.10(0.96-1.25) | 0 | 78.6 | 3 | 1.04(0.81-1.35) | 0.046 | 67.5 | 3 | 1.11(0.91-1.35) | 0.266 | 24.4 |

| Time period of use | ||||||||||||

| Current use | 6 | 1.06(0.95-1.19) | 0 | 85.6 | 4 | 1.45(0.98-2.15) | 0 | 95.9 | 4 | 1.72(0.96-3.09) | 0 | 96.6 |

| Recent use | 4 | 1.07(0.98-1.17) | 0.654 | 0 | 3 | 1.06(0.82-1.39) | 0.257 | 26.3 | 4 | 1.16(0.98-1.36) | 0.416 | 0 |

| Former use | 7 | 1.05(0.99-1.12) | 0.209 | 26.4 | 5 | 1.00(0.95-1.06) | 0.423 | 0 | 4 | 1.00(0.83-1.20) | 0.037 | 60.9 |

| Duration of use | ||||||||||||

| <5 years | 10 | 0.99(0.95-1.03) | 0.647 | 0 | 6 | 1.02(0.95-1.10) | 0.595 | 0 | 6 | 1.00(0.90-1.10) | 0.138 | 36.5 |

| 5-10 years | 6 | 1.02(0.95-1.09) | 0.683 | 0 | 4 | 0.94(0.84-1.06) | 0.721 | 0 | 5 | 1.09(0.98-1.20) | 0.985 | 0 |

| ≥10 years | 7 | 1.01(0.92-1.12) | 0.188 | 30.1 | 4 | 1.11(0.85-1.45) | 0.016 | 67.2 | 5 | 1.07(0.71-1.60) | 0.003 | 72.4 |

| Exposure was defined as “ever use” | 17 | 1.01(0.98-1.05) | 0.175 | 24.2 | 7 | 1.06(0.96-1.16) | 0.152 | 36.3 | 10 | 1.08(0.96-1.20) | 0.027 | 52.2 |

| Exposure was assessed by prescription database | 9 | 1.02(0.95-1.09) | 0 | 76.9 | 4 | 1.00(0.88-1.13) | 0.049 | 61.9 | 4 | 1.02(0.84-1.24) | 0.003 | 78.2 |

AHT, antihypertensive medications; BBs, beta blockers; CCBs, calcium channel blockers; RR, relative risk; CI, confidence interval.

Table 3. Subgroup and sensitivity analyses of associations between use of ACEi/ARBs and diuretics and breast cancer risk.

| ACEi/ARBs | Diuretics | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | n | RR (95% CI) | Pheterogeneity | I2 (%) | n | RR (95% CI) | Pheterogeneity | I2 (%) |

| Total | 13 | 0.99(0.93-1.05) | 0.021 | 47.5 | 11 | 1.05(0.99-1.12) | 0.004 | 58.2 |

| Design | ||||||||

| Retrospective study | 7 | 1.03(0.95-1.10) | 0.040 | 52.4 | 5 | 1.03(0.93-1.15) | 0.133 | 40.8 |

| Prospective study | 6 | 0.92(0.86-1.00) | 0.356 | 9.3 | 6 | 1.07(0.98-1.16) | 0.006 | 66.7 |

| Geographic area | ||||||||

| North America | 8 | 0.94(0.88-1.00) | 0.547 | 0 | 8 | 1.04(0.98-1.10) | 0.224 | 23.8 |

| Europe | 4 | 1.05(0.92-1.18) | 0.004 | 77.6 | 3 | 1.05(0.90-1.23) | 0.004 | 81.6 |

| Study quality score | ||||||||

| High (NOS score >6) | 11 | 0.98(0.92-1.05) | 0.011 | 53.7 | 7 | 1.01(0.97-1.06) | 0.693 | 0 |

| Low (NOS score ≤6) | 2 | 1.06(0.88-1.27) | 0.530 | 0 | 4 | 1.15(0.99-1.33) | 0.024 | 68.4 |

| Time period of use | ||||||||

| Current use | 4 | 1.05(0.85-1.30) | 0 | 80.7 | 4 | 1.05(0.95-1.17) | 0.003 | 72.0 |

| Recent use | 3 | 1.03(0.88-1.21) | 0.380 | 0 | 1 | 1.20(0.80-1.90) | - | - |

| Former use | 4 | 0.98(0.87-1.12) | 0.097 | 49.0 | 4 | 1.03(0.89-1.19) | 0.002 | 76.2 |

| Duration of use | ||||||||

| <5 years | 5 | 0.95(0.87-1.04) | 0.713 | 0 | 6 | 1.03(0.97-1.10) | 0.921 | 0 |

| 5-10 years | 3 | 0.91(0.78-1.06) | 0.596 | 0 | 4 | 0.99(0.89-1.09) | 0.544 | 0 |

| ≥10 years | 4 | 0.80(0.67-0.95) | 0.610 | 0 | 5 | 1.09(0.99-1.19) | 0.589 | 0 |

| Exposure was defined as “ever use” | 10 | 1.04(0.97-1.10) | 0.120 | 36.0 | 7 | 1.05(0.97-1.13) | 0.151 | 36.3 |

| Exposure was assessed by prescription database | 5 | 1.03(0.94-1.13) | 0.009 | 70.2 | 3 | 1.05(0.90-1.23) | 0.004 | 81.6 |

ACEi, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; ARBs, angiotensin receptor blockers; RR, relative risk; CI, confidence interval.

Further, we performed a subgroup analysis based on AHT subclasses. With respect to CCBs dihydropyridine and nondihydropyridines CCB use were assessed separately, but neither was associated with breast cancer risk. Similarly, analyses by specific ACEi/ARB type did not reveal any statistically significant association. However, in evaluating risks according to diuretic subclasses, a borderline elevated risk of breast cancer was observed among users of thiazides diuretics (RR = 1.12, 95% CI: 1.01-1.24) but not other diuretic subtypes (Table 4).

Table 4. Subgroup analyses of associations between particular types of antihypertensive drug use and breast cancer risk.

| Group | No. of studies | RR (95% CI) | Pheterogeneity | I2 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCBs | ||||

| DiCCBs | 5 | 1.07(0.90-1.27) | 0.026 | 58.1 |

| Non-DiCCBs | 4 | 1.23(1.00-1.51) | 0.115 | 43.5 |

| ACEi/ARBs | ||||

| ACEi | 10 | 0.98(0.91-1.06) | 0.006 | 58.3 |

| ARBs | 5 | 1.02(0.96-1.08) | 0.698 | 0 |

| Diuretics | ||||

| Thiazides | 5 | 1.12(1.01-1.24) | 0.286 | 20.3 |

| Loop | 4 | 0.91(0.77-1.06) | 0.481 | 0 |

| Potassium sparing | 6 | 1.17(1.00-1.36) | 0.024 | 61.2 |

CCBs, calcium channel blockers; DiCCBs, dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers; Non-DiCCBs, Non-dihydropyridines; ACEi, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; ARBs, angiotensin receptor blockers; RR, relative risk; CI, confidence interval.

Sensitivity analyses

To confirm the robustness of our results, we carried out several sensitivity analyses. First, we excluded four studies [2, 10, 15, 23] that defined exposure as current use (in contrast to ever use in most studies). Exclusion of these studies did not substantially alter the overall result. Second, we restricted our analyses to studies [9, 10, 15, 16, 18, 21, 24, 26, 27] that used prescription databases, which made them less susceptible than questionnaire-based studies to recall bias. Again, the risk estimates were firmly in line with the complete analysis (Tables 2, 3). Third, sensitivity analysis was performed for each drug category by sequential omission of individual studies using the random-effects model. The results revealed that no study appeared to influence the overall pooled risk estimates (data not shown). Notably, the study by Chang et al [9] may be the key contributor to the between-study heterogeneity for BBs and CCBs. After excluding the study, no evidence of heterogeneity was observed among the remaining studies for BBs (Pheterogeneity = 0.269, I2 = 17.8%) or CCBs (Pheterogeneity = 0.323, I2 = 11.8%).

Publication bias

There was no evidence of publication bias with regard to use of overall AHTs or individual classes in relation to breast cancer risk according to Begg’s funnel plot and Egger’s regression test (P = 0.827 for AHTs, P = 0.396 for BBs, P = 0.127 for CCBs, P = 0.587 for ACEi/ARBs, and P = 0.734 for diuretics).

DISCUSSION

Results from 21 observational studies including 3,167,020 participants and 102,054 cases show that there is no increase in breast cancer risk among users of AHTs overall or specific major classes as compared to nonusers. These findings remained consistent in most subgroup and sensitivity analyses, which considered study design, geographic area, time period of use, subtypes, drug exposure definition, and drug exposure assessment method. Yet, when stratified by duration of use, a significant reduced risk of breast cancer was particularly observed among females taking ACEi/ARBs for 10 years or longer.

In line with our findings, a network meta-analysis of randomized trials also showed no increased cancer risk with the use of CCBs, ACEi, ARBs, BB, or diuretics [54]. However, our study differs from that of Bangalore and colleagues [54] in that our main analyses specifically focused on the association between AHT use and breast cancer risk, which has a distinctive etiology and pathogenesis compared with other types of cancer. Moreover, the trial evidence of that meta-analysis [54] had a mean follow-up of only 3.5 years, suggesting that the exposure time to AHTs might have been insufficient to make any meaningful conclusions about cancer incidence in humans. By using observational studies in our meta-analysis, we were able to include studies with longer duration of drug use and conduct a subgroup analysis of studies with drug use for 10 years or longer.

CCB use has long been hypothesized to promote cell proliferation and tumor growth [13], yet epidemiological studies have reported mixed results in relation to breast cancer occurrence [2, 9, 12–14, 16–18, 20, 22–24]. Our study is generally consistent with two previous meta-analyses of observational data published in 2014 [55, 56], indicating no carcinogenic effect of CCB on breast cancer. In evaluating the effect of long-term CCB use, however, previous meta-analyses [55, 56] drew conflicting conclusions with both positive and null associations. This difference was likely due to the small number of included studies with data on duration ≥10 years (3 [55] and 2 [56], respectively) and insufficient statistical power in their analyses. Three large cohort studies of high quality (all NOS >7) have been published since the meta-analyses, and all showed no association with breast cancer incidence [23, 24, 53]. We added these updated studies to our analysis, which significantly increased the sample size and made our results more accurate. In the subgroup analysis, we found a positive association between CCB use and breast cancer risk in retrospective but not prospective studies. This difference is likely attributable to recall and selection bias inherent in retrospective design. Thus, the positive result should not be overemphasized. Taken together, our findings do not support an overall association of CCB use, including long-term use, with breast cancer risk.

Although our results provided no evidence of an overall association between ACEi/ARB use and breast cancer risk, a potentially intriguing finding is the decreased risk for longer duration of ACEi/ARB use (≥10 years). This finding is consistent with a prior Seattle-Puget Sound case-control study, which identified a borderline significant risk reduction for lobular breast cancers among women using ACEis for 10 years or longer (RR = 0.6, 95% CI: 0.4-1.0) [2]. Furthermore, in line with our finding, two nationwide prospective studies in Taiwan also demonstrated that the effect of ARBs on cancer prevention correlated with treatment duration [48, 57]. The potential mechanisms underlying this antineoplastic effect of ACEi/ARBs on breast cancer are manifold and not completely understood. Several in vitro studies have shown that ACEi/ARBs suppress the cell proliferative effects of angiotensin II in breast cancer by inhibiting the renin-angiotensin system and its downstream signaling proteins such as tissue factor, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), and the transcription factors NF-κB and CREB [58–60]. ACEi/ARBs have also been implicated in inhibiting breast cancer adhesion and invasion through reducing expression of integrin subtypes α3 and β1 [61]. In addition, ARB use has been shown to prevent tumor growth and angiogenesis by blocking VEGF-A expression in mice models of breast cancer [62].

Preclinical studies have shown that antagonism of β-adrenergic receptor signaling by BBs may inhibit multiple cellular processes involved in breast cancer initiation and progression, including cell proliferation, angiogenesis, and tumor immune responses [63]. While a few studies have reported associations between BB use and breast cancer risk [9, 50], our findings are consistent with the majority of observational studies that found no effect of BBs. However, we were unable to explore the relationship between the use of particular types of BBs and breast cancer risk since most of the studies reported BB as a composite class of AHTs and did not separately report the effects of beta-1 selective and nonselective subtypes. Only one case-control study in Taiwan [50] addressed this point and showed an increased risk for treatment with beta-1 selective blockers but not nonselective blockers. Therefore, whether the association differs according to BB subtype warrants further study.

With respect to diuretics, we did not observe an increased risk of breast cancer associated with overall diuretic use. Moreover, no trend of increasing risk with increasing duration of use was observed. Of note though, our subgroup analyses did show that use of thiazide diuretics but not other diuretic subclasses was significantly associated with an increased risk of breast cancer. To interpret the difference by drug subtype is challenging. One possible explanation is that thiazide diuretic use may increase insulin resistance [64], which has long been suggested as a risk factor for breast cancer [65, 66]. Alternatively, the borderline significant association may have occurred by chance due to the limited number of studies and participants analyzed. Consequently, this observation needs to be interpreted cautiously, and it requires replication in studies with sufficient numbers of specific diuretic subtype users.

Even though most of the included studies in this meta-analysis were of high quality as evidenced by high Newcastle-Ottawa quality assessment scores, we acknowledge that there were some limitations, and thus, the results should be interpreted with caution. First, this was a meta-analysis of observational studies, which are inherently prone to several types of bias [67]. For example, most AHT users are hypertensive, leading to selection bias of an unhealthier exposed group. These subjects might also undergo more medical examinations and laboratory surveillance, resulting in detection bias. Additionally, since ascertainment of AHT use largely depended on questionnaires, there is potential for recall bias, and exposure misclassification may have occurred. Second, most of the included studies (except for that by Chang et al [9]) were conducted in Western populations. Therefore, the results might not be generalizable to other groups, especially Asian AHT users with a different baseline breast cancer risk. Third, significant heterogeneity was observed among studies of individual classes of AHT and breast cancer risk. This persisted despite stratifying the data into subgroups based on study design, region, drug class, time period, and duration of drug use. Fourth, confounders were not uniformly adjusted across the included studies. Therefore, we cannot exclude the possibility that potential confounders such as body mass index, diabetes, alcohol use, chronic liver disease, and kidney disease involved in AHT metabolism may have affected the associations. Finally, publication bias could be of concern in our meta-analysis, although no evidence of such a bias was found with Begg’s funnel plot or Egger’s test. However, the number of studies included was relatively small, which may limit their statistical power.

In conclusion, the results of our study suggest a possible beneficial effect of long-term ACEi/ARB use on breast cancer risk. Considering potential biases and confounders in this meta-analysis of observational studies, large clinical trials with long-term follow-up are needed to fully assess the effect of these medications on breast cancer risk.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Literature search

A comprehensive, computerized literature search was independently performed by two investigators (Q.R. and H.B.N.) in PubMed and EMBASE databases from January 1966 through July 2016. The following text and/or medical subject heading terms were used: “antihypertensive drug” or “calcium channel blockers” or “beta blockers” or “angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors” or “angiotensin receptor blockers” or “diuretics” combined with “breast cancer” or “breast neoplasm.” In addition, the reference lists of reviews and retrieved articles were manually searched to identify additional relevant articles. No language restrictions were imposed. The present study was performed in accordance with the guidelines proposed by the Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology group [28].

Study selection

Studies were eligible for this meta-analysis if they fulfilled the following inclusion criteria: (1) published as an original article; (2) used a case-control or cohort design; (3) the exposure of interest was AHT intake, including the following five classes: ACEi, ARB, CCB, BB, or diuretics; (4) outcome was primary breast cancer occurrence; and (5) reported relative risk (RR), odds ratio (OR), or hazard ratio (HR) with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) or sufficient data to calculate them. When multiple studies reported the same data, results from the publication including the largest number of participants were used. We did not consider conference abstracts for inclusion.

Data extraction and quality assessment

From each included study, the following information were recorded: first author’s surname, publication year, study design, geographical location, study period, duration of follow-up evaluation in cohort studies, participant age, numbers of cases and participants, type of medication exposure, assessment method of exposure and breast cancer, and adjustments for confounders. We extracted the risk estimates that reflected the greatest degree of control for potential confounders from each eligible study.

The Newcastle-Ottawa scale was used to assess the quality of individual studies. In brief, a maximum of 9 points was assigned to each study: 4 for selection, 2 for comparability, and 3 for outcomes. A final score >6 was regarded as high quality. Data extraction and quality assessment were performed by two independent investigators (Q.R. and H.B.N.). Any disagreement was settled by discussion.

Statistical analysis

We used RRs as common measures of the association between AHT use and breast cancer risk across studies. For one study [23] that stratified risk estimates by two subcohorts (NHS and NHS II) and another study [2] that reported stratified risk estimates by tumor subtype (ductal and lobular breast cancer), we treated each result as a separate report. The combined risk estimates were computed using either a fixed-effect model or, in the presence of heterogeneity, a random-effect model. Between-study heterogeneity was evaluated by Cochran’s Q and I2 statistics. For Cochran’s Q statistic, results were defined as heterogeneous for P values less than 0.10; I2 values of 25%, 50%, and 75% represented cut-off points for low, moderate, and high heterogeneity, respectively [29].

We estimated the associations between overall AHT use as well as specific classes (CCB, ACEi/ARB, BB, and diuretics) and breast cancer risk. For six studies [9, 17, 18, 26, 27, 52] that only reported stratified risk estimates by AHT subtype, we combined the estimates using a random-effects model and then included the pooled estimates in the overall AHT meta-analysis. Among included studies, the most common definition of drugs exposure was “ever use vs. never use,” although four studies [2, 10, 15, 23] only provided results for “current use vs. never use,” we included all these studies in the main meta-analysis and performed a sensitivity analysis that only included studies with exposure defined as “ever use vs. never use.” Prespecified subgroup analyses were performed according to study design (retrospective or prospective), geographic area (North America or Europe), study quality score (high or low), time period of drug use (current, recent, or former), duration of drug use (<5, 5-10, or ≥10 years), and subtype of individual classes to examine the impact of these factors on the associations. Current use was defined as AHT use that lasted until the index date or ended within 6 months prior to the index date, former use was defined as use that ended more than 6 months before the index date, and recent use was defined as use that ended within 2 years prior to the index date. Due to limited number of studies provided data on BB subtypes, the stratified analysis by subclasses focused on CCBs (dihydropyridine or nondihydropyridines), ACEi/ARBs, and diuretics (thiazides, loop, or potassium sparing). To test the robustness of associations, we performed a sensitivity analysis restricted to studies that used a prescription database to identify drug exposure. We also investigated the influence of a single study on the overall risk estimate by omitting each study in each turn.

Potential publication bias was examined using Begg’s funnel plots [30] and Egger’s regression tests [31]. All statistical analyses were performed using STATA 12.0 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA) statistical software. A P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant unless otherwise specified.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Mr. Rock Lau (General Manager) and Dr. Lindsay Reese (senior American copyeditor) from New Bridge Translation Co., Ltd. (Guangzhou, China) for language editing of the manuscript.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

GRANT SUPPORT

No funding was received for this systematic review.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization A global brief on hypertension: silent killer, global public health crisis. 2013 Available at: http://ish-world.com/downloads/pdf/global_brief_hyperten-sion.pdf.

- 2.Li CI, Daling JR, Tang MT, Haugen KL, Porter PL, Malone KE. Use of antihypertensive medications and breast cancer risk among women aged 55 to 74 years. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:1629–1637. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.9071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Banerjee Y, Taranikanti V, Alriyami M. Can antihypertensive drugs increase the risk of cancer? Trends Mol Med. 2011;17:175–176. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2011.01.009. author reply 176–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fryzek J, Poulsen A, Johnsen SP, McLaughlin J, Sørensen HT, Friis S. A cohort study of antihypertensive treatments and risk of renal cell cancer. Br J Cancer. 2005;92:1302–1306. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Houben M, Coebergh J, Herings R, Casparie M, Tijssen C, van Duijn C, Stricker BC. The association between antihypertensive drugs and glioma. Br J Cancer. 2006;94:752–756. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huang T, Poole EM, Eliassen AH, Okereke OI, Kubzansky LD, Sood AK, Forman JP, Tworoger SS. Hypertension, use of antihypertensive medications, and risk of epithelial ovarian cancer. Int J Cancer. 2016;139:291–299. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heinonen O, Shapiro S, Tuominen L, Turunen M. Reserpine use in relation to breast cancer. Lancet. 1974;304:675–677. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(74)93259-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chang CH, Chiang CH, Yen CJ, Wu LC, Lin JW, Lai MS. Antihypertensive agents and the risk of breast cancer in women aged 55 years and older: a nested case-control study. J Hypertens. 2016;34:558–566. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000000813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Biggar RJ, Andersen EW, Wohlfahrt J, Melbye M. Spironolactone use and the risk of breast and gynecologic cancers. Cancer Epidemiol. 2013;37:870–875. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2013.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Largent JA, McEligot AJ, Ziogas A, Reid C, Hess J, Leighton N, Peel D, Anton-Culver H. Hypertension, diuretics and breast cancer risk. J Hum Hypertens. 2006;20:727–732. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1002075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li CI, Malone KE, Weiss NS, Boudreau DM, Cushing-Haugen KL, Daling JR. Relation between use of antihypertensive medications and risk of breast carcinoma among women ages 65-79 years. Cancer. 2003;98:1504–1513. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pahor M, Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L, Corti MC, Salive ME, Cerhan JR, Wallace RB, Havlik RJ. Calcium-channel blockade and incidence of cancer in aged populations. Lancet. 1996;348:493–497. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)04277-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rosenberg L, Rao RS, Palmer JR, Strom BL, Stolley PD, Zauber AG, Warshauer ME, Shapiro S. Calcium channel blockers and the risk of cancer. JAMA. 1998;279:1000–1004. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.13.1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gonzalez-Perez A, Ronquist G, Garcia Rodriguez LA. Breast cancer incidence and use of antihypertensive medication in women. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2004;13:581–585. doi: 10.1002/pds.910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fryzek JP, Poulsen AH, Lipworth L, Pedersen L, Norgaard M, McLaughlin JK, Friis S. A cohort study of antihypertensive medication use and breast cancer among Danish women. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2006;97:231–236. doi: 10.1007/s10549-005-9091-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davis S, Mirick DK. Medication use and the risk of breast cancer. Eur J Epidemiol. 2007;22:319–325. doi: 10.1007/s10654-007-9135-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Assimes TL, Elstein E, Langleben A, Suissa S. Long-term use of antihypertensive drugs and risk of cancer. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2008;17:1039–1049. doi: 10.1002/pds.1656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coogan PF, Strom BL, Rosenberg L. Diuretic use and the risk of breast cancer. J Hum Hypertens. 2009;23:216–218. doi: 10.1038/jhh.2008.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Largent JA, Bernstein L, Horn-Ross PL, Marshall SF, Neuhausen S, Reynolds P, Ursin G, Zell JA, Ziogas A, Anton-Culver H. Hypertension, antihypertensive medication use, and breast cancer risk in the California teachers study cohort. Cancer Causes Control. 2010;21:1615–1624. doi: 10.1007/s10552-010-9590-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mackenzie IS, Macdonald TM, Thompson A, Morant S, Wei L. Spironolactone and risk of incident breast cancer in women older than 55 years: retrospective, matched cohort study. BMJ. 2012;345:e4447. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e4447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saltzman BS, Weiss NS, Sieh W, Fitzpatrick AL, McTiernan A, Daling JR, Li CI. Use of antihypertensive medications and breast cancer risk. Cancer Causes Control. 2013;24:365–371. doi: 10.1007/s10552-012-0122-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Devore EE, Kim S, Ramin CA, Wegrzyn LR, Massa J, Holmes MD, Michels KB, Tamimi RM, Forman JP, Schernhammer ES. Antihypertensive medication use and incident breast cancer in women. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2015;150:219–229. doi: 10.1007/s10549-015-3311-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Azoulay L, Soldera S, Yin H, Bouganim N. Use of calcium channel blockers and risk of breast cancer: a population-based cohort study. Epidemiology. 2016;27:594–601. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Van Der Knaap R, Siemes C, Coebergh JW, Van Duijn CM, Hofman A, Stricker BH. Renin-angiotensin system inhibitors, angiotensin I-converting enzyme gene insertion/deletion polymorphism, and cancer: The Rotterdam study. Cancer. 2008;112:748–757. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Azoulay L, Assimes TL, Yin H, Bartels DB, Schiffrin EL, Suissa S. Long-term use of angiotensin receptor blockers and the risk of cancer. PLoS One. 2012;7:e50893. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hallas J, Christensen R, Andersen M, Friis S, Bjerrum L. Long term use of drugs affecting the renin-angiotensin system and the risk of cancer: a population-based case-control study. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;74:180–188. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2012.04170.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, Moher D, Becker BJ, Sipe TA, Thacker SB. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. JAMA. 2000;283:2008–2012. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. 1994;50:1088–1101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Egger M, Smith GD, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grossman E, Messerli FH, Goldbourt U. Carcinogenicity of antihypertensive therapy. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2002;4:195–201. doi: 10.1007/s11906-002-0007-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Giordano SH. Breast carcinoma and antihypertensive therapy. Cancer. 2003;98:1334–1336. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goon PK, Messerli FH, Lip GY. Hypertension and breast cancer: an association revisited? J Hum Hypertens. 2006;20:722–724. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1002053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.ARB Trialists Collaboration Effects of telmisartan, irbesartan, valsartan, candesartan, and losartan on cancers in 15 trials enrolling 138,769 individuals. J Hypertens. 2011;29:623–635. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e328344a7de. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Villa M, Boni S, Iodice S, Rognoni M, Sampietro G, Russo A. Beta blockers and breast cancer: Results from a collaborative study. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2013;22:68–69. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Azoulay L, Soldera S, Yin H, Bouganim N. The long-term use of calcium channel blockers and the risk of breast cancer. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2015;24:431. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chang CH, Wu LC, Chiang CH, Lin JW, Lai MS. Long-term use of calcium channel blockers, beta-blockers, angiotensin-receptor blockade and risk of breast cancer in women aged 55 years or older: a nationwide study. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2015;24:312–313. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Raebel MA, Zeng C, Feigelson HS, Shetterly S, Carroll NM, Goddard K, Boudreau DM, Smith DH, Cheetham TC, Tavel H, Xu S. Breast cancer risk with long-term use of calcium channel blockers or angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors among postmenopausal women. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2015;24:552–553. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Soldera SV, Bouganim N, Asselah J, Yin H, Maroun R, Azoulay L. The long-term use of calcium channel blockers and the risk of breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:15. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fitzpatrick AL, Daling JR, Furberg CD, Kronmal RA, Weissfeld JL. Use of calcium channel blockers and breast carcinoma risk in postmenopausal women. Cancer. 1997;80:1438–1447. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19971015)80:8<1438::aid-cncr11>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Olsen JH, Sørensen HT, Friis S, McLaughlin JK, Steffensen FH, Nielsen GL, Andersen M, Fraumeni JF, Olsen J. Cancer risk in users of calcium channel blockers. Hypertension. 1997;29:1091–1094. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.29.5.1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Meier CR, Derby LE, Jick SS, Jick H. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, calcium channel blockers, and breast cancer. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:349–353. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.3.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sørensen HT, Olsen JH, Mellemkjær L, Thulstrup AM, Steffensen FH, McLaughlin JK, Baron JA. Cancer risk and mortality in users of calcium channel blockers. Cancer. 2000;89:165–170. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20000701)89:1<165::aid-cncr21>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Friis S, Sorensen HT, Mellemkjaer L, McLaughlin JK, Nielsen GL, Blot WJ, Olsen JH. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and the risk of cancer: a population-based cohort study in Denmark. Cancer. 2001;92:2462–2470. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20011101)92:9<2462::aid-cncr1596>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pasternak B, Svanstrom H, Callreus T, Melbye M, Hviid A. Use of angiotensin receptor blockers and the risk of cancer. Circulation. 2011;123:1729–1736. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.007336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bhaskaran K, Douglas I, Evans S, van Staa T, Smeeth L. Angiotensin receptor blockers and risk of cancer: cohort study among people receiving antihypertensive drugs in UK General Practice Research Database. BMJ. 2012;344:e2697. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e2697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang KL, Liu CJ, Chao TF, Huang CM, Wu CH, Chen TJ, Chiang CE. Long-term use of angiotensin II receptor blockers and risk of cancer: a population-based cohort analysis. Int J Cardiol. 2013;167:2162–2166. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2012.05.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chang PY, Huang WY, Lin CL, Huang TC, Wu YY, Chen JH, Kao CH. Propranolol reduces cancer risk: a population-based cohort study. Medicine. 2015;94:e1097. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000001097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Leung HW, Hung LL, Chan AL, Mou CH. Long-term use of antihypertensive agents and risk of breast cancer: a population-based case–control study. Cardiol Ther. 2015;4:65–76. doi: 10.1007/s40119-015-0035-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chen L, Malone KE, Li CI. Use of antihypertensive medications not associated with risk of contralateral breast cancer among women diagnosed with estrogen receptor-positive invasive breast cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2015;24:1423–1426. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-15-0547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rosenberg L, Rao RS, Palmer JR, Strom BL, Stolley PD, Zauber AG, Warshauer ME, Shapiro S. Calcium channel blockers and the risk of cancer. JAMA. 1998;279:1000–1004. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.13.1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wilson LE, D’Aloisio AA, Sandler DP, Taylor JA. Long-term use of calcium channel blocking drugs and breast cancer risk in a prospective cohort of US and Puerto Rican women. Breast Cancer Res. 2016;18:61. doi: 10.1186/s13058-016-0720-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bangalore S, Kumar S, Kjeldsen SE, Makani H, Grossman E, Wetterslev J, Gupta AK, Sever PS, Gluud C, Messerli FH. Antihypertensive drugs and risk of cancer: network meta-analyses and trial sequential analyses of 324 168 participants from randomised trials. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:65–82. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70260-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chen Q, Zhang Q, Zhong F, Guo S, Jin Z, Shi W, Chen C, He J. Association between calcium channel blockers and breast cancer: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2014;23:711–718. doi: 10.1002/pds.3645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Li W, Shi Q, Wang W, Liu J, Li Q, Hou F. Calcium channel blockers and risk of breast cancer: a meta-analysis of 17 observational studies. PLoS One. 2014;9:e105801. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0105801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 57.Huang CC, Chan WL, Chen YC, Chen TJ, Lin SJ, Chen JW, Leu HB. Angiotensin II receptor blockers and risk of cancer in patients with systemic hypertension. Am J Cardiol. 2011;107:1028–1033. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Napoleone E, Cutrone A, Cugino D, Amore C, Di Santo A, Iacoviello L, de Gaetano G, Donati MB, Lorenzet R. Inhibition of the renin-angiotensin system downregulates tissue factor and vascular endothelial growth factor in human breast carcinoma cells. Thromb Res. 2012;129:736–742. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2011.11.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Du N, Feng J, Hu LJ, Sun X, Sun HB, Zhao Y, Yang YP, Ren H. Angiotensin II receptor type 1 blockers suppress the cell proliferation effects of angiotensin II in breast cancer cells by inhibiting AT1R signaling. Oncol Rep. 2012;27:1893–1903. doi: 10.3892/or.2012.1720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rodrigues-Ferreira S, Abdelkarim M, Dillenburg-Pilla P, Luissint AC, di-Tommaso A, Deshayes F, Pontes CL, Molina A, Cagnard N, Letourneur F, Morel M, Reis RI, Casarini DE, et al. Angiotensin II facilitates breast cancer cell migration and metastasis. PLoS One. 2012;7:e35667. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Puddefoot J, Udeozo U, Barker S, Vinson G. The role of angiotensin II in the regulation of breast cancer cell adhesion and invasion. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2006;13:895–903. doi: 10.1677/erc.1.01136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chen X, Meng Q, Zhao Y, Liu M, Li D, Yang Y, Sun L, Sui G, Cai L, Dong X. Angiotensin II type 1 receptor antagonists inhibit cell proliferation and angiogenesis in breast cancer. Cancer Lett. 2013;328:318–324. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2012.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Barron TI, Sharp L, Visvanathan K. Beta-adrenergic blocking drugs in breast cancer: a perspective review. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2012;4:113–125. doi: 10.1177/1758834012439738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sarafidis PA, McFarlane SI, Bakris GL. Antihypertensive agents, insulin sensitivity, and new-onset diabetes. Curr Diab Rep. 2007;7:191–199. doi: 10.1007/s11892-007-0031-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bruning PF, Bonfrèr JM, van Noord PA, Hart AA, de Jong-Bakker M, Nooijen WJ. Insulin resistance and breast cancer risk. Int J Cancer. 1992;52:511–516. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910520402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Malin A, Dai Q, Yu H, Shu XO, Jin F, Gao YT, Zheng W. Evaluation of the synergistic effect of insulin resistance and insulin-like growth factors on the risk of breast carcinoma. Cancer. 2004;100:694–700. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Signorello LB, McLaughlin JK, Lipworth L, Friis S, Sørensen HT, Blot WJ. Confounding by indication in epidemiologic studies of commonly used analgesics. Am J Ther. 2002;9:199–205. doi: 10.1097/00045391-200205000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]