Abstract

The gene that encodes de novo DNA methyltransferase 3A (DNMT3A) is frequently mutated in acute myeloid leukemia genomes. Point mutations at position R882 have been shown to cause a dominant negative loss of DNMT3A methylation activity, but 15% of DNMT3A mutations are predicted to produce truncated proteins that could either have dominant negative activities or cause loss of function and haploinsufficiency. Here, we demonstrate that 3 of these mutants produce truncated, inactive proteins that do not dimerize with WT DNMT3A, strongly supporting the haploinsufficiency hypothesis. We therefore evaluated hematopoiesis in mice heterozygous for a constitutive null Dnmt3a mutation. With no other manipulations, Dnmt3a+/– mice developed myeloid skewing over time, and their hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells exhibited a long-term competitive transplantation advantage. Dnmt3a+/– mice also spontaneously developed transplantable myeloid malignancies after a long latent period, and 3 of 12 tumors tested had cooperating mutations in the Ras/MAPK pathway. The residual Dnmt3a allele was neither mutated nor downregulated in these tumors. The bone marrow cells of Dnmt3a+/– mice had a subtle but statistically significant DNA hypomethylation phenotype that was not associated with gene dysregulation. These data demonstrate that haploinsufficiency for Dnmt3a alters hematopoiesis and predisposes mice (and probably humans) to myeloid malignancies by a mechanism that is not yet clear.

Keywords: Hematology, Oncology

Keywords: Epigenetics, Hematopoietic stem cells, Leukemias

Introduction

The DNA methyltransferase 3A (DNMT3A) gene is mutated in approximately 37% of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) patients with a normal karyotype (and ~25% of all AML cases) (1) and is also frequently mutated in patients with myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) (2) and T cell leukemias (3). These mutations are almost always heterozygous and have been demonstrated to be associated with high myeloblast counts, advanced age, and poor prognosis (1, 4–7). In addition, these mutations typically occur at variant allele frequencies (VAFs) of approximately 50%, often persist in clinical remissions (8), and return at relapse as part of the founding clone (5, 9). Mutations in DNMT3A are by far the most common found in elderly people with clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential (CHIP) (10–12). All of these data suggest that DNMT3A mutations probably represent initiating events for many patients with AML.

In AML patients, DNMT3A mutations are highly enriched for changes at a single amino acid in the catalytic domain at position R882 (1). Recent studies have shown that the R882H mutation leads to an approximately 80% reduction in the methyltransferase activity of the DNMT3A enzyme and also exerts a dominant negative effect on the remaining WT DNMT3A protein present in the same cells (13, 14). DNMT3A molecules with the R882H mutation form stable heterodimers with WT DNMT3A, which interferes with the ability of the WT DNMT3A protein to form active homotetramers and leads to a canonical hypomethylation signature in AML samples with R882 DNMT3A mutations (14, 15). In contrast, this hypomethylation signature was undetectable in primary AML samples with non-R882 DNMT3A mutations, even though these mutations are also associated with poor prognosis in AML (1, 14).

About 15%–20% of DNMT3A mutations found in AML are single-copy deletions or truncations of DNMT3A resulting from nonsense or insertion-deletion frameshift mutations at positions other than R882 (1, 16). In MDS patients, 30% of DNMT3A mutations are predicted to cause loss of function (2), but about 60% of DNMT3A mutations in people with CHIP have mutations of this class (10–12). As noted above, normal karyotype AML patients with non-R882 DNMT3A mutations do not have a detectable DNA hypomethylation phenotype, suggesting that these mutations generally do not have dominant negative activity (14). Therefore, we hypothesized that the non-R882 mutations in DNMT3A — especially those that are predicted to cause truncations of DNMT3A — may contribute to leukemogenesis through a different mechanism, i.e., haploinsufficiency.

In this study, we define the molecular consequences of 3 truncation mutations and show that they function as null alleles. We therefore modeled haploinsufficiency by characterizing hematopoiesis in mice heterozygous for a germline null mutation in Dnmt3a (17). Our findings suggest that many DNMT3A mutations found in AML patients lead to haploinsufficiency and that DNMT3A haploinsufficiency may predispose to myeloid malignancies in both mice and humans.

Results

AML-associated DNMT3A truncation mutations produce an inactive DNA methyltransferase.

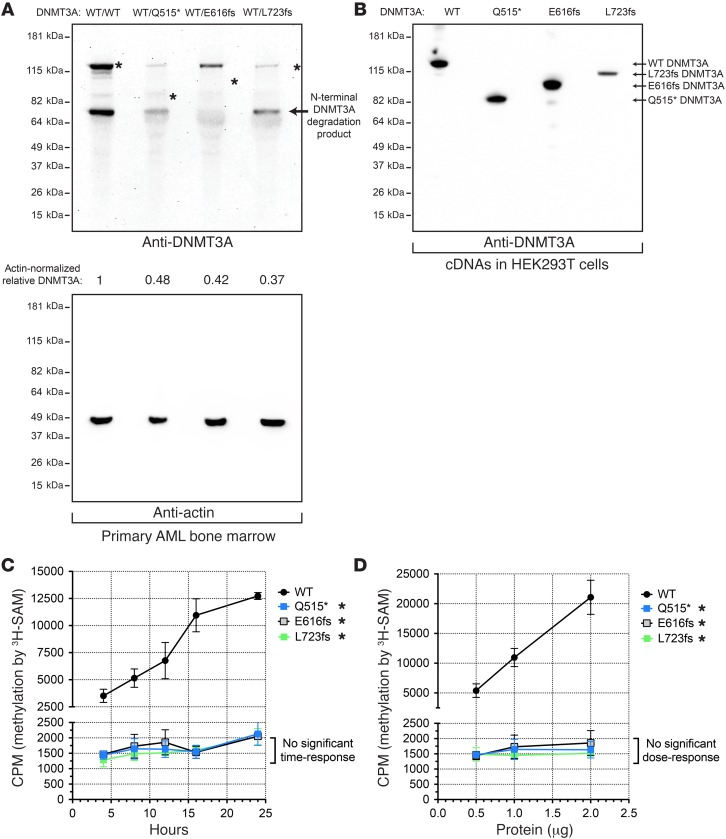

To determine whether AML-associated DNMT3A truncation mutations can yield stable proteins that can be found in AML cells, we focused on 3 representative mutations first identified in normal karyotype AML patients: Q515*, E616fs, and L723fs (1). Whole-genome sequencing of primary diagnostic bone marrow samples from these AML patients demonstrated that these mutant alleles were present at VAFs consistent with heterozygosity in nearly all the cells in the samples, and RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) detected expression of all of the corresponding transcripts, showing that these 3 mutations do not cause nonsense-mediated decay (Supplemental Table 1; supplemental material available online with this article; https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI93041DS1). We performed Western blots for DNMT3A on whole cell lysates of primary AML diagnostic bone marrow samples possessing these mutations (Figure 1A). Discrete bands at the predicted positions of the truncated proteins were not detected (despite the detection of full-length DNMT3A in all 3 samples), suggesting that these mutant proteins may be unstable in AML cells. Quantification of these Western blots revealed that full-length DNMT3A was reduced in abundance by 52%–63% compared with that in a control AML sample that was WT for DNMT3A; this also suggests that the residual WT DNMT3A allele in these samples must be functional. However, transient expression of the cDNAs encoding these mutant forms of DNMT3A did yield stable, truncated proteins of the predicted sizes in HEK293T cells (Figure 1B), suggesting that these proteins may in fact be produced in AML cells and may have potential functional consequences on WT DNMT3A.

Figure 1. Truncated DNMT3A proteins are absent in AML cells, but stable in HEK293T cells, and lack de novo DNA methyltransferase activity.

(A) Western blot of endogenous DNMT3A (top panel) or actin (bottom panel) from primary AML bone marrow samples (DNMT3AWT/WT, DNMT3AWT/Q515*, DNMT3AWT/E616fs, and DNMT3AWT/L723fs). Asterisks indicate predicted positions of DNMT3A based on corresponding cDNAs (B). (B) Western blot of exogenous DNMT3A produced by WT, Q515*, E616fs, and L723fs DNMT3A cDNAs expressed in HEK293T cells. (C) In vitro methylation of a linearized plasmid DNA substrate (pcDNA3.1) by recombinant full-length human WT or mutant DNMT3A (Q515*, E616fs, or L723fs). Time-course assays using 1 μg of total protein per 35 μl reaction (250 nM). (D) In vitro methylation of a linearized plasmid DNA substrate (pcDNA3.1) by recombinant full-length human WT or mutant DNMT3A (Q515*, E616fs, or L723fs). Dose response with fixed 16-hour incubation. All experiments were independently performed 3 times, and data for C and D are shown as mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments, each performed in triplicate. *P < 0.05, 2-way ANOVA relative to WT DNMT3A.

To explore the biochemical consequences of these 3 truncated proteins, we purified human WT, Q515*, E616fs, and L723fs DNMT3A using an N-terminal 6x-histidine tag and immobilized metal ion (Ni2+) affinity chromatography. Purified recombinant proteins were assessed by BCA assays, SYPRO Ruby protein gel stains, and quantitative Western blots to validate protein purity and abundance. We compared the de novo DNA methyltransferase activities of WT, Q515*, E616fs, and L723fs DNMT3A using an in vitro DNA methylation assay that detects the DNMT3A-mediated transfer of tritiated methyl groups from the methyl-donor molecule S-adenosylmethionine (3H-SAM) to a linearized, CpG-rich pcDNA3.1 plasmid DNA containing 334 CpG residues in the 5.4-kb plasmid. WT DNMT3A exhibited robust de novo methylation activity, which increased proportionally with reaction time (Figure 1C) and enzyme concentration (Figure 1D). In contrast, we observed a near total loss of methyltransferase activity with each of the 3 truncated DNMT3A forms (Figure 1, C and D).

DNMT3A truncation mutants fail to heterodimerize with WT DNMT3A.

X-ray crystallography analyses and biochemical studies of DNMT3A have revealed that its active form is a homotetramer, with 2 interfaces mediating homooligomerization. Both of these interfaces are located within the C-terminal catalytic methyltransferase domain of DNMT3A: one is a hydrophobic FF interface (specifically, F732 and F772), and the other is a polar RD interface (specifically, R885 and D876) (18). DNMT3A mutations at residues near these interacting interfaces are common in AML patients (e.g., R729, R736, R771, and R882). AML mutations that produce truncated DNMT3A proteins, including Q515*, E616fs, and L723fs, remove both of the DNMT3A self-interacting interfaces, and therefore we predicted these proteins would fail to dimerize with WT DNMT3A.

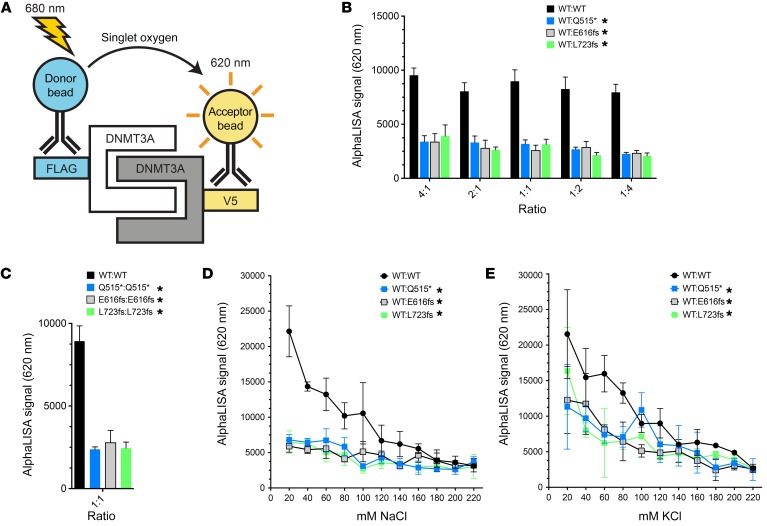

To test this hypothesis, we utilized the PerkinElmer AlphaLISA amplified luminescence proximity platform (19) to measure direct interactions between DNMT3A molecules with or without the mutations of interest (Figure 2A). Our approach utilized whole cell lysates of HEK293T cells expressing C-terminal epitope-tagged (FLAG or V5) WT or mutant DNMT3A, in combination with anti-FLAG donor and anti-V5 acceptor beads. Upon dimerization of FLAG-tagged and V5-tagged proteins and colocalization of their corresponding beads, excitation of the donor bead with 680 nm light resulted in emission of a quantifiable signal of 620 nm light from the acceptor bead.

Figure 2. DNMT3A truncation mutants do not heterodimerize with WT DNMT3A and fail to form mutant DNMT3A homodimers.

(A) AlphaLISA assay schematic of assay for B–E, in which the interaction between DNMT3A-FLAG and DNMT3A-V5 molecules is measured. Anti-FLAG “donor” beads excited by light at 680 nm release singlet oxygen, which can excite anti-V5 “acceptor” beads within 200 nm, leading to emission light at 620 nm. (B) AlphaLISA measurement of dimerization of WT DNMT3A-V5 with DNMT3A-FLAG (WT, Q515*, E616fs, and L723fs), with crosstitration (4:1, 2:1, 1:1, 1:2, 1:4). (C) Quantification of DNMT3A-FLAG:DNMT3A-V5 homodimerization (WT:WT, Q515*:Q515*, E616fs:E616fs, and L723fs:L723fs) when mixed at 1:1 stoichiometric ratio. (D) Oligomerization of WT DNMT3A-V5 and DNMT3A-FLAG (WT, Q515*, E616fs, or L723fs), mixed at a 1:1 stoichiometric ratio, in response to NaCl. (E) WT DNMT3A-V5 and DNMT3A-FLAG (WT, Q515*, E616fs, or L723fs) oligomerization, mixed at a 1:1 stoichiometric ratio, in response to KCl. All data are shown as mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments, each performed in triplicate. *P < 0.05, 2-way ANOVA relative to WT:WT.

HEK293T cells were transiently transfected with expression vectors containing cDNAs for DNMT3A-FLAG (WT, Q515*, E616fs, and L723fs) or DNMT3A-V5 (WT), and mixed cell lysates were analyzed with the AlphaLISA assay to compare the WT/WT interaction with the WT/mutant interactions for Q515*, E616fs, and L723fs (Figure 2B). Each of these 3 truncated forms of DNMT3A failed to interact with WT DNMT3A when mixed at a 1:1 ratio. To detect weak WT/mutant interactions, we altered the ratios of DNMT3A proteins in the AlphaLISA assay to drive complex formation with a 2- or 4-fold excess of either DNMT3A protein component. While the WT/WT DNMT3A interaction remained robust across this range of protein ratios, the WT/mutant interactions were not detectable using any of these conditions (Figure 2B). Furthermore, none of these 3 truncated forms of DNMT3A were able to produce homodimers detectable by this assay (Figure 2C), indicating that they must exist as monomers, essentially ruling out the possibility that stable mutant/mutant complexes mask the detection of weak WT/mutant interactions.

Although purified DNMT3A oligomers are stable at physiological salt conditions (20), optimal de novo DNA methylation occurs at low-salt conditions (i.e., <50 mM NaCl or KCl) (21, 22). To determine whether low-salt conditions favorable for de novo DNA methylation could facilitate interactions between WT and truncated forms of DNMT3A, we directly explored the effects of NaCl and KCl levels on DNMT3A oligomerization using the AlphaLISA assay (Figure 2, D and E). As predicted, the WT/WT DNMT3A interaction was maximal at low-salt concentrations and was inhibited with increasing concentrations of NaCl or KCl. The DNMT3A truncations, however, exhibited minimal interactions with WT DNMT3A, even at very low-salt (e.g., 20 mM) concentrations.

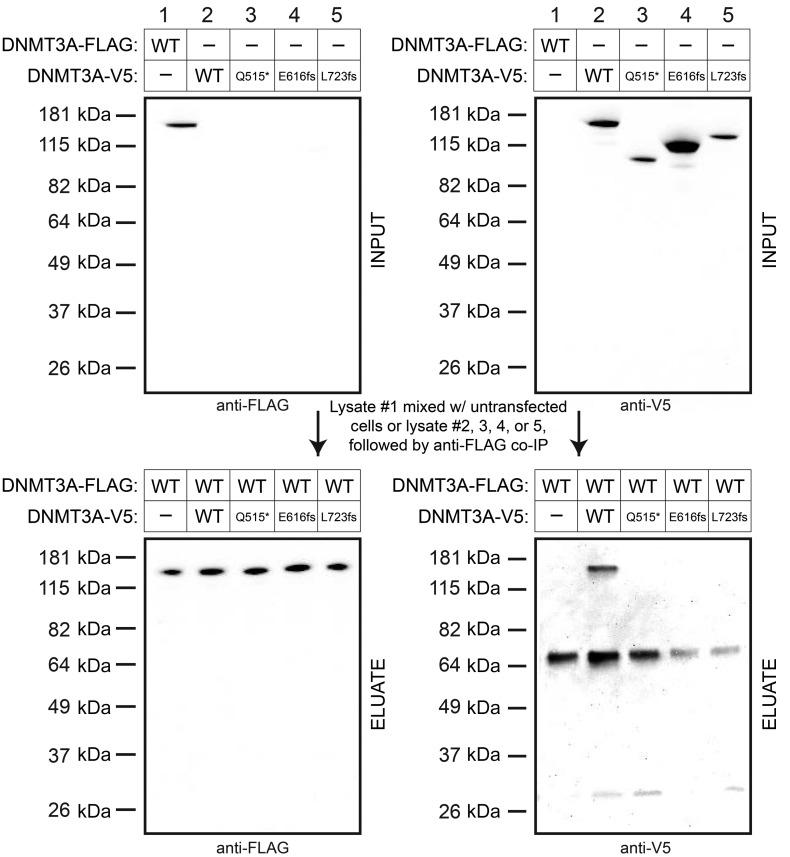

We orthogonally validated the lack of interaction among these 3 truncated forms of DNMT3A and the WT protein using immunoprecipitation assays. We performed low-stringency anti-FLAG coimmunoprecipitation assays on FLAG-tagged WT DNMT3A mixed with DNMT3A-V5 (WT, Q515*, E616fs, or L723fs). Although we could easily detect coimmunoprecipitation of WT DNMT3A-V5 from the WT DNMT3A-FLAG pull-down, no truncated DNMT3A-V5 forms were detected in the WT DNMT3A-FLAG pull-down eluate by Western blotting (Figure 3). This confirms the lack of WT/mutant DNMT3A interactions for these 3 truncation mutations and implies that cells with these mutations are essentially haploinsufficient for DNMT3A protein.

Figure 3. DNMT3A truncation mutants do not coimmunoprecipitate with WT DNMT3A.

Anti-FLAG immunoprecipitation of WT DNMT3A-FLAG in HEK293T whole cell lysates mixed with HEK293T whole cell lysates with DNMT3A-V5 (either WT, Q515*, E616fs, or L723fs) or equivalent protein from untransfected cells. All experiments were independently performed twice.

Young Dnmt3a+/– mice exhibit normal hematopoiesis.

To characterize the effects of Dnmt3a haploinsufficiency on hematopoiesis, we used a previously described constitutive Dnmt3a-knockout mouse with a neomycin resistance cassette inserted into a deletion of exons 18 and 19 of the catalytic domain of Dnmt3a (17). We previously verified that this mutation produces a null allele with no detectable Dnmt3a protein by Western blotting of homozygous null embryos with an N-terminal Dnmt3a antibody (23) and determined that the bone marrow cells of these homozygous Dnmt3a–/– mice have a focal, canonical DNA hypomethylation phenotype using targeted bisulfite sequencing (23). In this study, we intercrossed heterozygous Dnmt3a+/– mice on a C57BL/6 background to generate Dnmt3a+/+, Dnmt3a+/–, and Dnmt3a–/– littermates. Mice with all 3 genotypes were born at the expected ratios, but the Dnmt3a–/– mice were severely runted and died 2 to 3 weeks after birth, as previously described (17). Dnmt3a+/– mice did not exhibit a runting phenotype. Using intracellular flow cytometry on stem and progenitor populations, we verified that the bone marrow cells of Dnmt3a+/– mice produced approximately 50% as much Dnmt3a protein as the cells from Dnmt3a+/+ mice in all hematopoietic compartments assessed (Supplemental Figure 1). Six-week-old Dnmt3a+/– and Dnmt3a+/+ mice were euthanized, and bone marrow was harvested for study of mature lineage compartments (myeloid, B, and T cells; Supplemental Figure 2A) as well as for myeloid precursors (granulocyte-macrophage progenitor [GMP], common myeloid progenitor [CMP], and megakaryocyte–erythroid progenitor [MEP] cells) and enriched hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs/KLS-SLAM cells; Supplemental Figure 2B). At this age, no significant differences in the frequencies of any of these compartments were observed between Dnmt3a+/+ and Dnmt3a+/– mice.

Loss of 1 copy of Dnmt3a did not lead to an aberrant self-renewal phenotype when whole bone marrow from these mice was serially replated in MethoCult media (Supplemental Figure 2C). Large cohorts of Dnmt3a+/– (n = 43) and Dnmt3a+/+ mice (n = 20) were generated, and peripheral blood counts were evaluated serially; no differences were observed between these genotypes at any time point up to 1 year of age (data not shown).

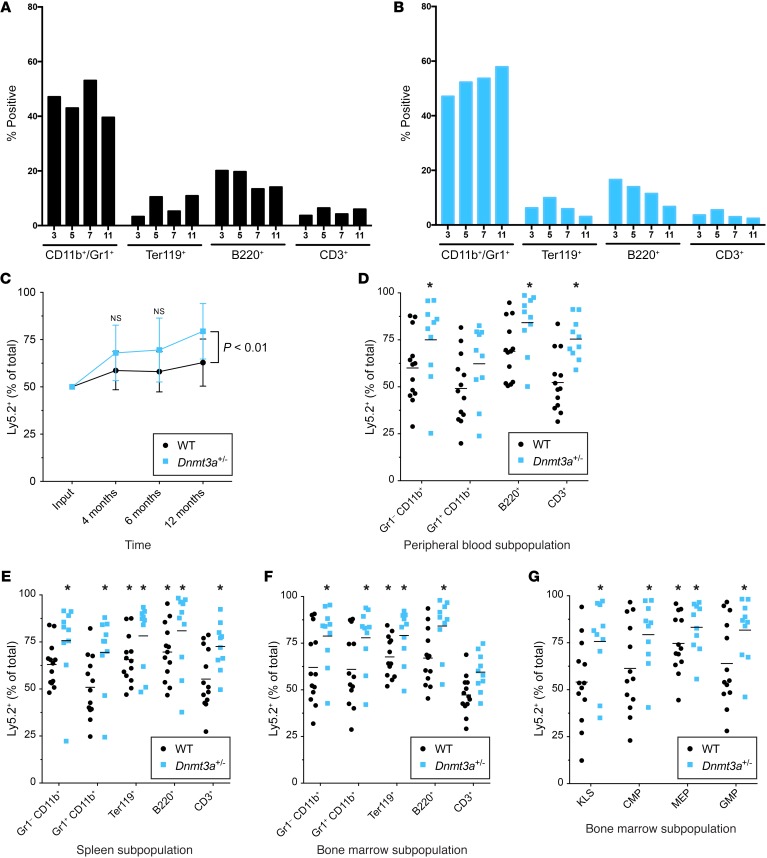

Dnmt3a+/– mice gradually develop myeloid skewing, and their HSPCs display a competitive advantage that is time dependent.

Although Dnmt3a+/– mice have normal hematopoiesis at 6 weeks of age, serial evaluation of littermate-matched, unmanipulated Dnmt3a+/+ versus Dnmt3a+/– mice at 3, 5, 7, and 11 months of age revealed a subtle but consistent increase in myeloid lineage cells in the bone marrow over time (Figure 4, A and B), with a reciprocal decrease in B, T, and erythroid lineage cells. However, the progenitor populations from these samples were not significantly altered, consistent with the data from 6-week-old mice (Supplemental Figure 2 and data not shown). To determine whether the hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells (HSPCs) of Dnmt3a+/– mice had a competitive advantage over WT cells, we mixed whole bone marrow cells from 6-week-old Dnmt3a+/+ or Dnmt3a+/– animals (Ly5.2) with equal numbers of competitor WT bone marrow cells (Ly5.1x5.2), and transplanted these cells into lethally irradiated mice (n = 13 for Dnmt3a+/+ and n = 10 for Dnmt3a+/– mice). There was not a significant advantage for Dnmt3a+/–-derived donor cells in the peripheral blood at 4 or 6 months after transplant (Figure 4C). However, when the peripheral blood of these mice was analyzed at 1 year after transplant, the Dnmt3a+/– donor cells made up approximately 80% of all donor-derived cells (Figure 4, C and D). We therefore sacrificed all of the mice at this time point to more thoroughly define the lineage and progenitor compartments that were affected by Dnmt3a haploinsufficiency. We found a significant advantage for Dnmt3a+/– cells in both the myeloid and lymphoid lineage cells of the spleen and bone marrow (Figure 4, E and F). The KLS, MEP, CMP, and GMP compartments from bone marrow cells all predominately comprised Dnmt3a+/– -derived cells (Figure 4G). Together, these data suggest that absence of a single copy of Dnmt3a provides an advantage for HSPCs with multilineage potential.

Figure 4. Bone marrow cells from Dnmt3a+/– mice display myeloid skewing and a competitive advantage that is time dependent.

(A and B) Flow cytometric evaluation of lineage markers from the bone marrow cells of unmanipulated mice harvested at the indicated ages, designated in months (n = 1 per genotype per time point). (A) Dnmt3a+/+ mice. (B) Dnmt3a+/– mice. (C–G) Bone marrow from 6-week-old Dnmt3a+/+ or Dnmt3a+/– mice (Ly5.2) was mixed 50:50 with WT competitor marrow (Ly5.1x5.2) and transplanted into lethally irradiated WT mice (Ly5.1). n = 13 Dnmt3a+/+; n = 10 Dnmt3a+/–. (C) Peripheral blood chimerism at 4 months, 6 months, and 1 year after transplant. P < 0.01, 2-sample, 2-tailed t test. (D–G) Percentage of Ly5.2+ cells (i.e., experimental cells, either Dnmt3a+/+ or Dnmt3a+/–) in the indicated lineage or progenitor populations at the 1-year time point. *P < 0.05, 1-sample, 2-tailed t test vs. 50% corrected for multiple testing by Bonferroni’s method. (D) Peripheral blood–derived cells. (E) Spleen-derived cells. (F and G) Bone marrow–derived cells.

Dnmt3a+/– mice develop myeloid malignancies after a long latent period.

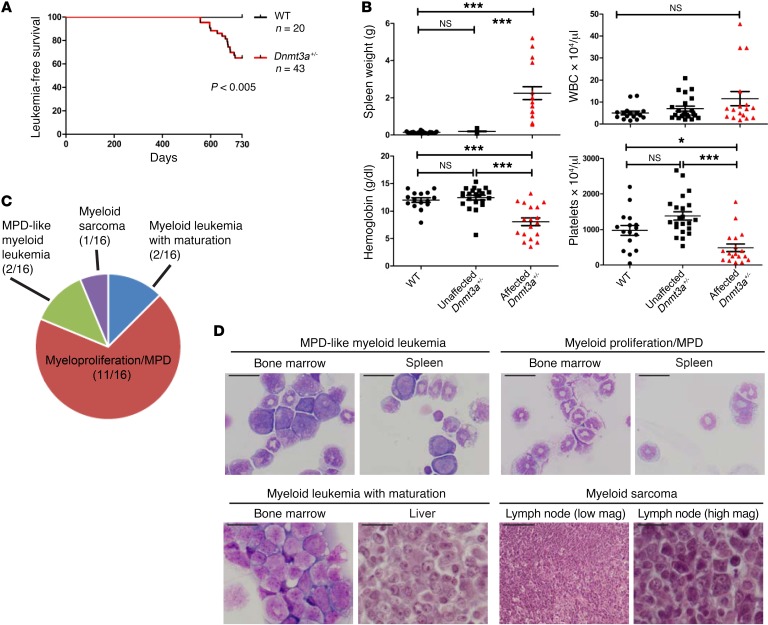

Because the myeloid skewing and competitive advantage of Dnmt3a+/– bone marrow cells was slow to develop, we decided to test whether these mice had an increased risk for developing myeloid malignancies after a long latent period. We therefore monitored a large cohort of unmanipulated, littermate-matched Dnmt3a+/– and Dnmt3a+/+ mice for 2 years. After 18 months, several Dnmt3a+/– mice (15/43, 35%) became moribund, exhibiting lethargy, abdominal distension, ruffled fur, and pale extremities (Figure 5A). Affected mice were euthanized and found to have varying degrees of hepatosplenomegaly, with myeloid infiltrates in the spleen, liver, and other organs, including the mediastinal and cervical lymph nodes (Supplemental Table 2). At the conclusion of the tumor watch at 2 years, all remaining mice were euthanized for pathologic examination and an additional 9 Dnmt3a+/– mice were found to have similar pathologic findings, for an overall penetrance of 24/43 (56%). Affected mice were defined as those with spleen sizes greater than 5 SD above the mean spleen size of Dnmt3a+/+ mice at 2 years of age (Figure 5B). In addition to splenomegaly, many Dnmt3a+/– mice displayed anemia and thrombocytopenia. Flow cytometry of the spleen cells of affected animals revealed positivity for the myeloid markers Gr-1 and/or CD11b (Supplemental Table 2). Further, many spleens contained sizable populations of cells that coexpressed the late myeloid marker Gr-1 and the progenitor marker CD34, one of the hallmarks of myeloid leukemias in mice. No cases of myeloid malignancy were observed in any of the 20 Dnmt3a+/+ mice during the duration of the tumor watch. On the basis of flow cytometry and histopathologic evaluation by a blinded, board-certified hematopathologist (J.M. Klco), 11 of 16 tumors from the Dnmt3a+/– mice were classified by the Bethesda criteria (24) as myeloproliferative disease (MPD), 2 were defined as myeloid leukemia with maturation, 2 were called MPD-like myeloid leukemia, and 1 was classified as a myeloid sarcoma (Figure 5, C and D, Table 1, and Supplemental Table 2). No T cell leukemias were identified.

Figure 5. Dnmt3a+/– mice develop myeloid malignancies after a long latent period.

(A) Kaplan-Meier plot of survival data from littermate-matched Dnmt3a+/– (n = 43) and Dnmt3a+/+ (n = 20) mice that were monitored in a 2-year tumor watch. Mice that became moribund were euthanized for pathologic analysis. (B) After 2 years, all remaining mice were bled for CBCs and euthanized. All mice were grouped by spleen size into Dnmt3a+/+, clinically unaffected Dnmt3a+/–, and affected (moribund) Dnmt3a+/– mice (see Results for details). Affected Dnmt3a+/– mice exhibited anemia and thrombocytopenia, but not significant leukocytosis. *P < 0.05; ***P < 0.001, 1-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s correction for multiple testing. (C) Distribution of pathologic diagnoses according to Bethesda criteria for all mice that could be definitively classified (n = 16). (D) Representative histology of tissues from affected Dnmt3a+/– mice. Scale bars: 20 μm; 200 μm (low mag).

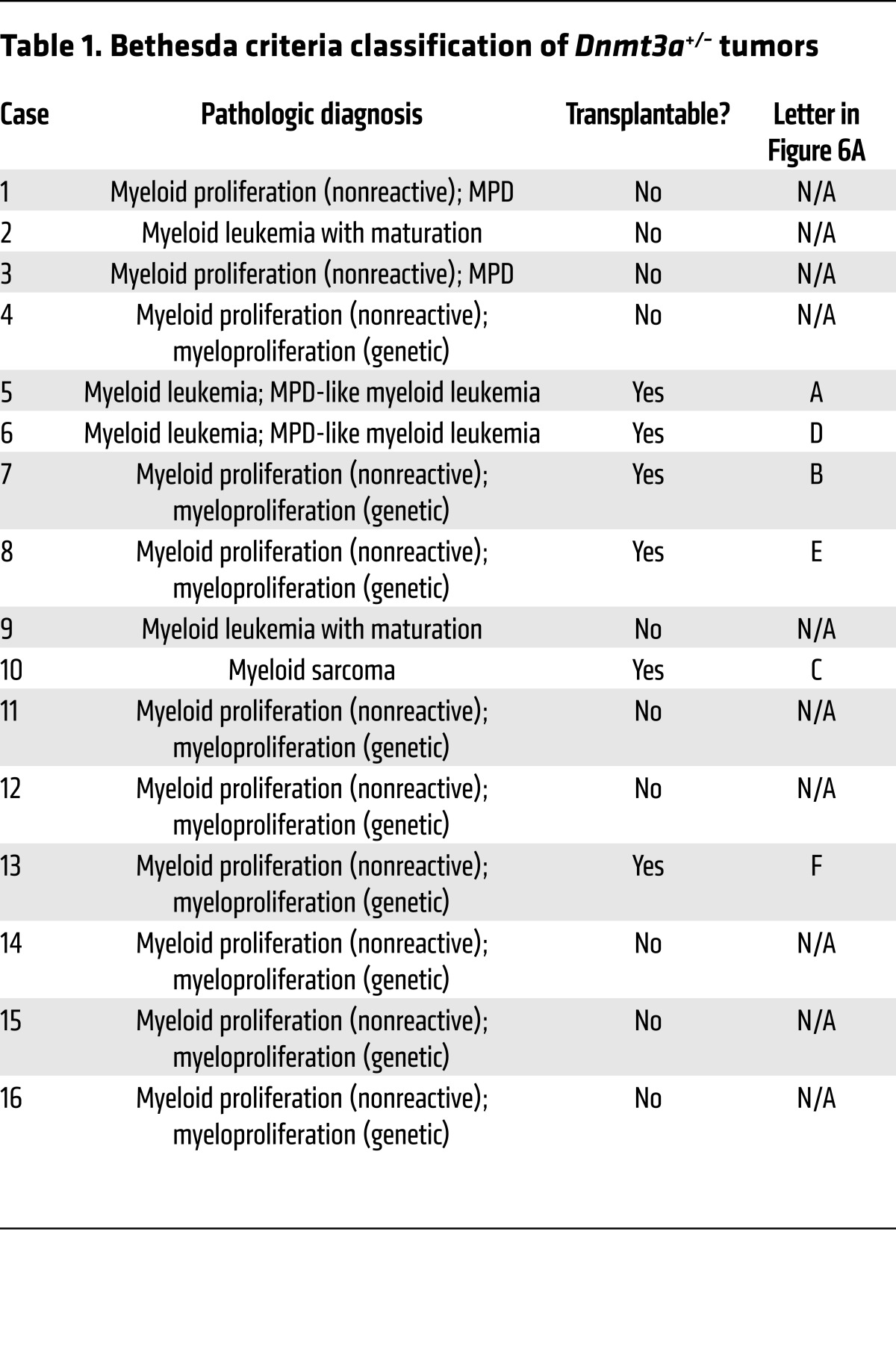

Table 1. Bethesda criteria classification of Dnmt3a+/– tumors.

Transplantable tumors from Dnmt3a+/– mice retain a functional WT Dnmt3a allele.

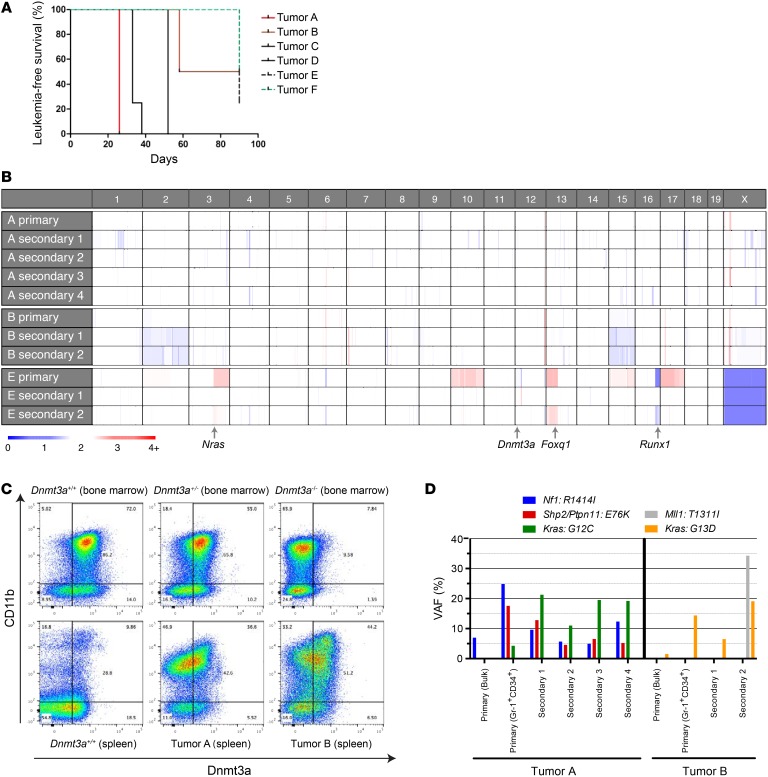

Of the 16 Dnmt3a+/– mice with myeloid disease that were fully characterized, 6 caused an acute, lethal malignancy when tumors were transplanted into sublethally irradiated, WT recipient mice (Figure 6A). Similarly, Poitras et al. (25) noted that 6 of 12 tumors arising in Dnmt3afl/+ × Flt3-ITD mice were transplantable. The median disease latencies of the transplanted tumors from our study ranged from 26 to 90 days (Figure 6A). Flow cytometry and gross pathologic examination demonstrated that tumors derived from the secondary animals were myeloid malignancies that recapitulated the cell surface phenotypes of the primary tumors, which all arose in unmanipulated Dnmt3a+/– mice (see Supplemental Figure 3 for a representative example).

Figure 6. Persistent expression of the residual WT Dnmt3a gene in AML samples arising in Dnmt3a+/– mice.

(A) Plot demonstrating disease latency for sublethally irradiated WT animals engrafted with Dnmt3a+/– tumors, designated A–F (see Table 1 and Supplemental Table 2). For each of the 6 primary tumors that were transplanted, 3 to 5 secondary recipient mice were assessed. (B) Copy number variation in sequenced tumors. Note that none of the tumors has deletions involving chromosome 12 at the location of the Dnmt3a gene. The locations of 3 cancer-related genes that were amplified (Nras, Foxq1) or deleted (Runx1) in tumor E are shown. Tumor E was derived from a male mouse; the single copy of the X chromosome in these tumors “calibrates” the color value for a single copy deletion. (C) Representative flow cytometry plots for Dnmt3a protein abundance in the CD11b+ compartment of Dnmt3a+/+, Dnmt3a+/–, and Dnmt3a–/– bone marrow samples (top panels) and a WT spleen or Dnmt3a+/– tumors A and B (derived from the unmanipulated spleen samples from the primary mice), showing preserved expression of WT Dnmt3a protein in the CD11b+ cells in each tumor spleen sample. The level of Dnmt3a protein in the tumor cells was similar to that of the haploinsufficient bone marrow cells. (D) VAFs for selected mutations detected in primary tumors (either bulk or sorted to enrich for Gr-1+CD34+ myeloid tumor cells) and in corresponding tumors from transplanted secondary recipients. Kras mutation VAFs are from AmpliSeq data (Supplemental Table 6), while other mutation VAFs are from exome sequencing (Supplemental Tables 3–5).

Whole-exome sequencing was performed on 3 of the 6 transplantable tumors (tumors A, B, and E) and on tumors from secondarily transplanted animals to determine whether the residual Dnmt3a allele had been inactivated by deletion or mutation. Tumors were compared with sorted B220+ B cells from the primary animal’s spleen as the control population. No point mutations or insertion-deletions in the residual Dnmt3a allele were detected in any of the tumors (Supplemental Tables 3, 4, and 5, and data not shown). A copy number variation algorithm was employed to detect copy number changes at the Dnmt3a locus. Similarly, when compared with a pooled normal control sample, no copy number changes were detected at the Dnmt3a locus in any of the sequenced tumors or their derivatives (Figure 6B). Further, intracellular flow cytometry for Dnmt3a protein was performed on spleen cells from tumors A and B, which demonstrated that Dnmt3a protein expression was maintained in the myeloid tumor cells (Figure 6C). The level of protein detected was similar to that of CD11b+ cells derived from Dnmt3a+/– mice. These data suggest that the residual WT Dnmt3a allele remains functional in fully transformed AML tumors arising in Dnmt3a+/– mice.

Exome sequencing revealed potential cooperating mutations in 3 sequenced tumors. Tumor A (classified as AML with maturation) contained somatic mutations in the Ras/MAPK pathway, including a missense mutation in the tumor suppressor Nf1 (R1414I; tumor A in Figure 6D, and Supplemental Table 3). In addition, all 4 secondary tumors derived from this primary tumor exhibited a canonical activating mutation in Kras (G12C) and a canonical activating mutation in Shp2/Ptpn11 (E76K; Figure 6D). The Kras and Shp2/Ptpn11 mutations were undetectable in the primary bulk tumor analysis, but were detected when the tumor was resorted for Gr-1, CD34 double-positive cells to enrich for the myeloid tumor population (Figure 6D), suggesting that these mutations were in a different, small subclone. Tumor B also contained a canonical activating mutation in Kras (G13D; tumor B in Figure 6D and Supplemental Table 4). A potentially relevant mutation in the H3K4 methyltransferase Mll1 (T1311I) was detected in 1 of 2 secondary tumors. This mutation was not detected in the original primary tumor even after sorting to enrich for myeloid cells, suggesting it may have been in a very small subclone in the primary sample or acquired during progression in the transplanted animals. The secondary samples from tumor B also contained a loss of most of chromosome 2 (Figure 6B), which is often associated with AML progression in mice (26). To validate the activating Kras mutations, we performed targeted sequencing using a PCR-based approach, followed by sequencing of a 200-bp amplicon containing the region encoding amino acids G12 and G13. This approach confirmed the Kras mutations in tumors A and B and identified an additional tumor with a Kras G12C mutation (Supplemental Table 6). These Ras/MAPK pathway mutations tended to occur at a higher VAF in the secondary tumors than in the unsorted primary tumors (Figure 6D and Supplemental Table 6), suggesting that they occurred in subclones that were positively selected for when the tumors expanded in secondary recipients. Of note, activated Ras mutations have previously been detected in tumors arising spontaneously in Dnmt3a-deficient mice (27) and they are known to cooperate with Dnmt3a deficiency to cause AML (28). Further, 9 of 52 (17%) AML samples with DNMT3A mutations from the TCGA study contained NRAS or KRAS mutations (16). Finally, although tumor E did not have any somatic mutations or insertion-deletions that are known to be associated with AML, this tumor had multiple copy number alterations that may have been relevant for pathogenesis, including the amplification of a segment of chromosome 3 (containing Nras) and chromosome 13 (containing Foxq1) and a deletion of a segment of chromosome 16 (containing Runx1) (Figure 6B; see Supplemental Table 7 for a list of potentially relevant genes on copy number–altered intervals).

DNA methylation and expression phenotypes in bone marrow cells from Dnmt3a+/– mice.

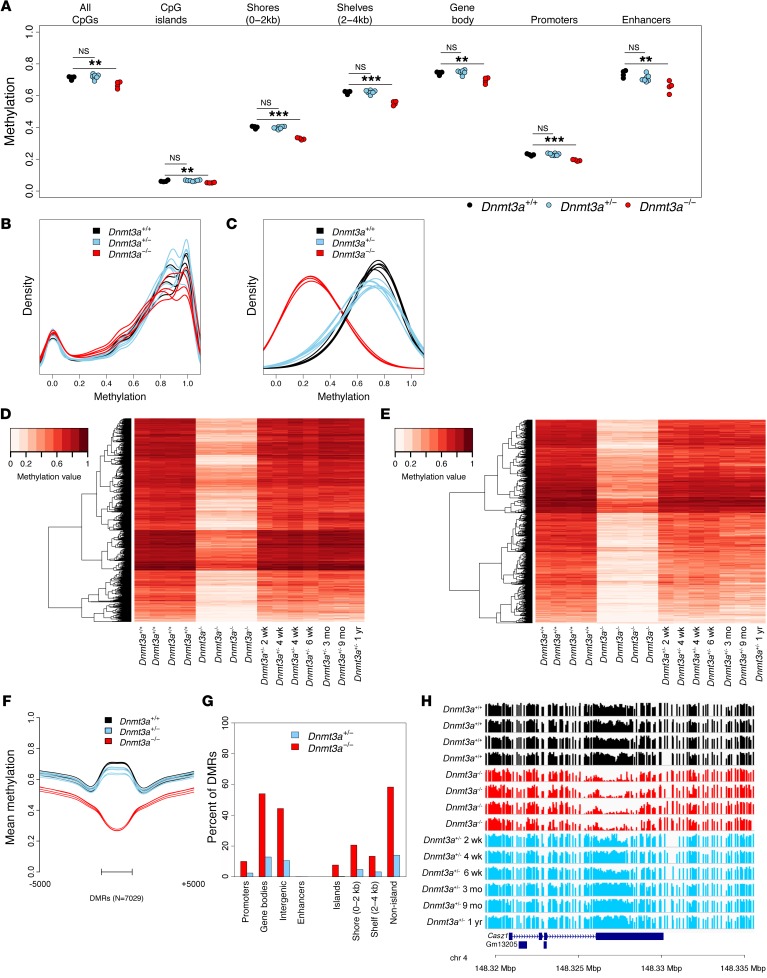

To determine whether nonleukemic Dnmt3a+/– bone marrow cells have a DNA methylation and/or gene expression phenotype that may contribute to the AML susceptibility phenotype, we performed whole-genome bisulfite sequencing and expression studies on these cells. Although similar studies have been performed on Dnmt3afl/fl HSPCs (29), these studies have not yet been described for the germline null mutation in Dnmt3a described by Okano et al. (17), either in the heterozygous or homozygous state. We therefore harvested total bone marrow cells from unmanipulated, nonleukemic Dnmt3a+/+, Dnmt3a+/–, and Dnmt3a–/– mice and subjected DNA from these cells to whole-genome bisulfite sequencing, as previously described (15). Four independent bone marrow samples were evaluated from 2-week-old Dnmt3a+/+ and Dnmt3a–/– mice; previous studies in our laboratory revealed that these samples have highly similar cellular compositions (23). Samples from 6 time points were obtained from Dnmt3a+/– mice, harvested at 2 weeks, 4 weeks (2 mice), 6 weeks, 3 months, 9 months, or 1 year of age. All animals had normal complete blood counts (CBCs) at the time of harvest (data not shown). Evaluation of CpG methylation values across the entire genome revealed that only a small fraction (3.53%) of all measured CpGs were significantly hypomethylated (P < 0.05; see Methods) in Dnmt3a–/– bone marrow cells compared with WT cells, whereas only 0.04% were hypermethylated. Although mean CpG methylation was significantly lower in all annotated regions of the genome in the Dnmt3a–/– samples, CpG island (CGI) shelves, CGI shores, and gene bodies had the most dramatic differences (Figure 7A). Dnmt3a+/– samples had far fewer hypomethylated CpGs and were not statistically different from WT samples at this level of resolution. We plotted the distribution of all methylation values across the genome for each sample, as shown in Figure 7B. As expected from the analysis above, the methylation patterns were highly similar from all sample sets.

Figure 7. DNA methylation phenotypes of Dnmt3a+/+, Dnmt3a+/–, and Dnmt3a–/– mice.

(A) Mean CpG methylation levels from whole-genome bisulfite sequencing of bone marrow cells from Dnmt3a+/+ (n = 4), Dnmt3a–/– (n = 4), and Dnmt3a+/– mice (n = 7). Values for specific annotated regions of the genome are shown. Hypothesis testing was performed via 2-tailed, pairwise t tests, with Bonferroni’s correction for multiple testing within genome regions; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001. (B) Density plot of methylation values from all CpGs for each bone marrow sample shown in A. (C) Density plot of methylation values from 7,029 DMRs defined by comparing the 4 Dnmt3a+/+ and 4 Dnmt3a–/– samples, all obtained from bone marrow of 2-week-old mice. Values for the same DMRs were plotted passively for Dnmt3a+/– samples. (D) Heatmap showing mean methylation values for the 7,029 DMRs as defined above. Note that the Dnmt3a+/– samples are plotted as a function of the age of the mice at harvest. (E) Heatmap showing mean methylation values for the 1,665 DMRs (from the set of 7,029) significantly different between Dnmt3a+/+ and Dnmt3a+/– samples. (F) Mean methylation values for all 7,029 DMRs from all samples, plotted by genotype from the center of the DMRs. (G) Fraction of 7,029 DMRs associated with annotated regions of the genome (Dnmt3a–/– DMRs are shown in red, and DMRs also significant in Dnmt3a+/– mice are shown in blue). (H) Primary methylation values for each CpG (shown as a bar from 0%–100% methylated for each sample) in a Dnmt3a–/– hypomethylated DMR inside the Casz1 gene body (not significantly hypomethylated in the Dnmt3a+/– samples, P = 0.19 by Mann-Whitney U test with Bonferroni’s correction).

We next identified all differentially methylated regions (DMRs) between the Dnmt3a+/+ and Dnmt3a–/– samples using established methods (15) and passively evaluated these DMRs for methylation phenotypes in the Dnmt3a+/– samples. We identified 7,029 DMRs in the Dnmt3a–/– samples, of which 7,023 (99.9%) were hypomethylated (Supplemental Table 8). Then, using this set of DMRs, we defined the mean methylation values for the same regions in the 6 Dnmt3a+/– samples and found that 1,665 regions (23.7% of the total DMRs) were also significantly different in the Dnmt3a+/– samples compared with Dnmt3a+/+ samples (Supplemental Table 8). Of these 1,665 DMRs, 1,662 (99.8%) were hypomethylated in the Dnmt3a+/– samples. A plot of the distribution of methylation values from CpGs in DMRs (Figure 7C) revealed both the clear-cut hypomethylation phenotype of the Dnmt3a–/– DMRs and the subtle but highly consistent hypomethylation phenotype of the Dnmt3a+/– DMRs plotted for the same regions.

The canonical nature of the 7,029 DMRs identified in the Dnmt3a+/+ versus Dnmt3a–/– samples was revealed in heatmaps that display the average methylation value of each DMR as a unique data point (Figure 7D). Clearly, nearly all of the DMRs are present in all 4 of the Dnmt3a–/– samples, which were obtained from 4 independent mice. We passively plotted the methylation data from the 6 Dnmt3a+/– samples according to their ages at harvest to determine whether the subtle methylation changes in the Dnmt3a+/– were age dependent. For this analysis, we focused on the 1,665 DMRs that were originally detected in the Dnmt3a+/+ versus Dnmt3a–/– samples as well as significantly hypomethylated in the Dnmt3a+/– samples (Figure 7E). Clearly, these regions are consistently less methylated in all the Dnmt3a+/– samples regardless of the age of the mouse at harvest and display intermediate methylation levels compared with Dnmt3a+/+ and Dnmt3a–/– samples (Figure 7F). The heatmap suggests that a small subset of CpGs may become more hypomethylated with age, but because the differences were small, few were statistically significant. Most of the DMRs in both the Dnmt3a–/– and Dnmt3a+/– samples mapped to gene bodies and intergenic regions (Figure 7G). Very few DMRs were associated with promoters or bone marrow–specific enhancer elements (as defined by ENCODE) (30). These findings are very similar to those found in nonleukemic human hematopoietic cells with heterozygous DNMT3AR882 mutations (15). An example of a typical DMR that is hypomethylated in all Dnmt3a–/– samples, but unaffected in Dnmt3a+/– samples, is shown in Figure 7H. An example of a DMR that is significantly hypomethylated in both the Dnmt3a–/– and the Dnmt3a+/– samples is shown in Supplemental Figure 4.

To define expression changes associated with Dnmt3a haploinsufficiency, we purified RNA from KLS cells to provide a uniform population of enriched stem/progenitor cells where Dnmt3a is normally highly expressed, performed linear amplification and labeling, and hybridized all samples with Affymetrix Mouse Exon 1.0 ST arrays (Dnmt3a+/+ vs. Dnmt3a+/– nontransplanted KLS cells, n = 3 each). Comparisons of the average expression values of each annotated gene are shown in Supplemental Figure 5. Dnmt3a+/+ and Dnmt3a+/– KLS cells had virtually identical expression patterns; only one probe set (from the Clgn gene) was found to be significantly different (P < 0.05) between WT and Dnmt3a+/– KLS cells, but this finding was not corroborated by other probe sets from this gene. We also evaluated the expression of all genes that were located within 5 kb of a Dnmt3a–/– DMR; none were shown to be dysregulated in Dnmt3a+/– KLS cells.

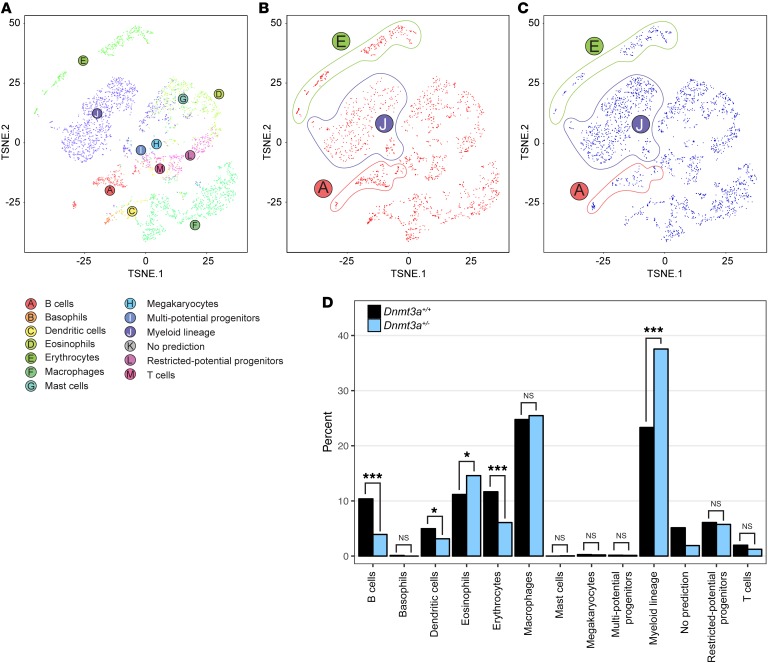

To determine whether Dnmt3a haploinsufficiency altered gene expression in a subpopulation of bone marrow cells and/or altered the cellular composition of bone marrow, we performed single-cell RNA-seq of the total bone marrow cells obtained from a pair of 5-month-old, littermate-matched, nontransplanted Dnmt3a+/+ and Dnmt3a+/– mice (the same 5-month-old samples used in Figure 4, A and B). Using the 10× Genomics platform (31), we made cDNA libraries from 1,870 cells from the Dnmt3a+/+ marrow and 2,419 cells from the Dnmt3a+/– marrow. After normalizing across samples for sequencing depth, the aggregated data set contained a mean of 27,232 reads per cell, a median of 1,478 detected genes per cell, and a median of 5,180 unique molecular identifier (UMI) counts per cell. Each cell was assigned to 1 of 13 hematopoietic cell lineages, as shown in the t-SNE plot of Figure 8A, using a reference set of lineage-specific gene expression profiles from the Haemopedia database (32). The pooled data from the 2 samples revealed all of the expected populations. However, when the 2 samples were examined independently (Figure 8B for Dnmt3a+/+ and Figure 8C for Dnmt3a+/–), an increase in the size of the myeloid lineage population was detected in the Dnmt3a+/– sample, along with reciprocal decreases in the size of the erythroid and B cell populations. The sizes of all identified compartments were compared statistically (Figure 8D), revealing that the changes in the sizes of these 3 lineage compartments in the Dnmt3a haploinsufficient mice were significant (along with smaller changes in other lineages). These data were corroborated by the flow cytometric data shown in Figure 4, A and B. The expression data were also clustered using k-means (k = 10). The resulting clusters recapitulated the major cell clusters inferred using the Haemopedia data set (Supplemental Figure 6A). We then identified genes whose expression was specific to each k-means cluster and found that these genes are consistent both with expected cell-type markers and the lineage assignments (Supplemental Figure 6B). Finally, we examined the cells in the myeloid lineage to detect genes that were differentially expressed between the Dnmt3a+/+ versus Dnmt3a+/– samples. We detected none, in agreement with our observations from the purified KLS cells (see Supplemental Table 9 for a comparison of the expression values for all genes in the myeloid compartment).

Figure 8. Single cell RNA-seq analysis of bone marrow cells from Dnmt3a+/+ versus Dnmt3a+/– mice.

(A) t-SNE plot colored by inferred cell lineage (the 2 basophils detected (B) are not labeled). The compartment labeled “Myeloid lineage” (J) corresponds to the “Neutrophils” in the Haemopedia database. Each dot represents a single cell. (B) t-SNE plot for Dnmt3a+/+ bone marrow cells. Lineages with different frequencies from the Dnmt3a+/– cells are circled (see C). (C) t-SNE plot for Dnmt3a+/– bone marrow cells. Lineages with different frequencies from the Dnmt3a+/+ cells are circled (see B). (D) Percentage of cells in each sample assigned to each lineage. Statistical significance was calculated using Fisher’s exact test with Bonferroni’s correction. *P < 0.01; **P < 0.001; ***P < 0.0001.

Discussion

The most common initiating mutations for normal karyotype AML patients occur in the DNMT3A gene (16). The majority of DNMT3A mutations in AML patients are heterozygous missense alterations, most of which affect amino acid position R882. DNMT3AR882 mutations encode a dominant negative protein that reduces the methyltransferase activity of DNMT3A; as a consequence, these AML samples have a focal, canonical hypomethylation phenotype (14, 15). However, 15%–20% of AML patients have heterozygous nonsense mutations or frameshift insertion-deletions that are predicted to result in premature termination of the protein. In this study, we demonstrate that 3 AML-associated truncation mutations in DNMT3A do not encode dominant negative proteins, but rather cause haploinsufficiency for DNMT3A. Mice that are haploinsufficient for Dnmt3a in the germline have normal resting hematopoiesis when they are young; however, they develop myeloid skewing over time, and their HSPCs develop a competitive advantage. After about 18 months, these mice start to develop spontaneous myeloid malignancies as they acquire cooperating mutations. Notably, these malignancies are not associated with the loss of the remaining Dnmt3a allele, which further supports the predicted haploinsufficiency mechanism. Nonleukemic bone marrow cells from Dnmt3a haploinsufficient mice have a subtle but statistically significant DNA hypomethylation phenotype that may contribute to the development of myeloid malignancies by mechanisms that are not yet clear.

DNMT3A mutations are also the most common mutations found in the blood cells of elderly individuals with CHIP. However, in this group of individuals, DNMT3AR882 mutations are relatively uncommon (10% of cases), while mutations predicted to cause haploinsufficiency are far more common (60% of cases) (10–12). Similarly, in this study, we have shown that mice that are haploinsufficient for Dnmt3a develop myeloid lineage skewing over time and that their HSPCs have a competitive advantage in vivo, perhaps akin to that seen in elderly people with CHIP and also to that in serially transplanted mice that are fully deficient for Dnmt3a (33). Similar observations have been made in mice that are haploinsufficient for PU.1/Spi1, where myeloid lineage expansion dramatically increases the probability that a PML-RARA transgene will cause APL (26). Together, these observations suggest that loss or inactivation of a single copy of DNMT3A may likewise increase the probability of developing AML by expanding the pool of myeloid lineage cells that are capable of cooperating with a second relevant mutation (e.g., NPMc, FLT3-ITD, etc.).

Normal karyotype AML patients with non-R882 DNMT3A mutations have persistent expression of the residual WT DNMT3A allele (16), suggesting that the WT copy is neither lost nor downregulated with tumor progression. Because biallelic DNMT3A mutations are unusual in patients with AML, we asked whether the residual WT Dnmt3a allele in tumors arising in Dnmt3a+/– mice was likewise intact and functional. With sequencing studies, we found no evidence for inactivation of the residual WT allele. Further, we detected Dnmt3a protein in myeloid tumor cells arising in Dnmt3a+/– mice, suggesting that these tumors did not progress because Dnmt3a function was entirely lost. Our biochemical studies of 3 truncation mutations verified that they produce catalytically inactive proteins and that they fail to interact with WT DNMT3A. Together, these findings strongly support the hypothesis that truncation mutations must act by causing DNMT3A haploinsufficiency and that the residual allele is not inactivated during tumor progression in either humans or mice.

The myeloid malignancies that spontaneously developed in Dnmt3a+/– mice were often aggressive, with most cases exhibiting massive splenomegaly and leukemic infiltrates into various extramedullary tissues. While DNMT3A mutations are often found in both myeloid and T cell malignancies in humans, we did not detect any lymphoid malignancies in the Dnmt3a+/– mice. Since C57BL/6 mice have a greater tendency to develop lymphoid versus myeloid malignancies (34–36), haploinsufficiency for Dnmt3a may specifically facilitate the development of myeloid tumors. In contrast, the studies of mice with the homozygous Dnmt3afl/fl mutation, from Mayle et al. (27), Celik et al. (37), and Poitras et al. (25), reported a broader spectrum of disease, including myeloid, early thymic progenitor, B cell, and T cell malignancies. Therefore, the loss of both copies of Dnmt3a (or dominant negative mutations, such as R882H) may influence the spectrum of hematologic malignancies that arise from mutant stem cells.

Recently, 3 other groups (25, 38, 39) have reported models of Dnmt3a haploinsufficiency that are associated with hematopoietic malignancies. Although all 3 of these studies used a different Dnmt3a mutant allele (Tadokoro et al., ref. 40) from the one used here, all found evidence that haploinsufficiency may be relevant for tumor initiation. Meyer et al. (38) and Poitras et al. (25) bred a FLT3-ITD allele into Dnmt3a mice with the floxed “Tadokoro” mutation, and both noted cooperation to produce AML. Poitras et al. (25) also noted that the latency of leukemia development in Dnmt3afl/+ mice was substantially longer than that of the Dnmt3afl/fl mice. Haney et al. (39) evaluated Dnmt3afl/+ mice using a Cre-transgene system (EμSRα-tTA) that “leaks” in the germline. Mice with a germline deletion in a single Dnmt3a allele were bred into the FVB/N background, and approximately 65% developed a chronic lymphocytic leukemia–like (CLL-like) phenotype after a long latent period, whereas 20% developed a nontransplantable myeloproliferative phenotype. Inactivating mutations in DNMT3A have not yet been described in human CLL patients (41, 42), suggesting that the FVB/N background or other factors may have contributed to the B cell phenotype. Clearly, all of the models have differences in the experimental design that could influence their phenotypes and additional experiments will be required to fully understand the differences observed among these model systems. Regardless, all of these studies — as well as that described here — support a model where Dnmt3a haploinsufficiency provides an initiating “hit” that predisposes mice to developing hematologic malignancies.

Is the DNA hypomethylation phenotype associated with DNMT3A mutations critical for AML initiation? We have recently shown that human patients with DNMT3AR882H mutations have a focal, canonical hypomethylation phenotype, even in nonleukemic hematopoietic cells (15), similar to that of Dnmt3a deficiency in mice (ref. 29 and this study). The methylation phenotype of AML genomes is dramatically altered when progression occurs: CGI hypermethylation, which is normally mediated by DNMT3A in AML cells, is attenuated by DNMT3AR882 mutations, but not in AMLs with haploinsufficiency for DNMT3A — probably because the residual WT DNMT3A allele is still active (15). In this report, we show for what we believe is the first time that nonleukemic, Dnmt3a haploinsufficient bone marrow cells also have a hypomethylation phenotype. The alterations in DNA methylation are subtle and are not associated with reproducible changes in gene expression patterns in either humans or mice, even with comprehensive RNA-seq approaches in human AML samples (15) and single cell RNA-seq (this study). Alternative mechanisms have also been shown to exist (such as an altered sensitivity of Dnmt3a mutant cells to chemotherapeutic drugs) (43). However, the downstream consequences of loss-of-function mutations in DNMT3A and the mechanisms by which they act to initiate AML are unclear at this time. Although new approaches will clearly be needed to define these mechanisms, the availability of mouse models that accurately recapitulate the consequences of human DNMT3A mutations will greatly facilitate these studies in the future.

Methods

Cell culture.

HEK293Tc18 cells (ATCC CRL-10852) were cultured in DMEM (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific) plus 10% FBS (Atlanta Biologicals) and 1× penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific).

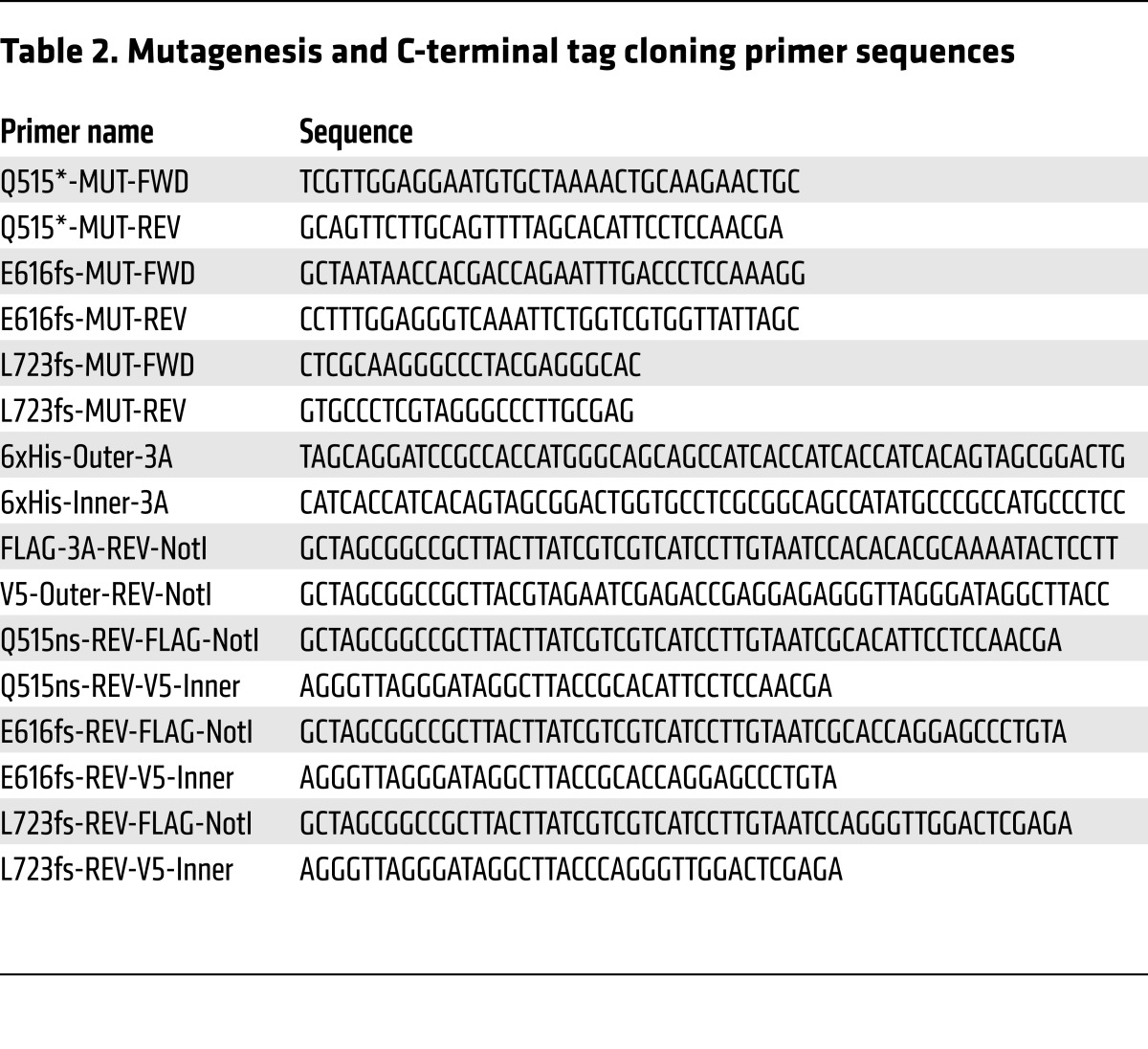

Protein purification.

N-terminal 6xHis-tags (MGSSHHHHHHSSGLVPRGSH) and C-terminal V5-tags (GKPIPNPLLGLDST) or FLAG-tags (DYKDDDDK) were cloned into a full-length DNMT3A (NM_175629.1) expression vector using the pCMV6 (Origene) backbone. Missense mutations (Q515*, E616fs, L723fs) in DNMT3A were generated using Agilent QuikChange II XL site-directed mutagenesis kit by the manufacturer’s protocol (see Table 2 for mutagenesis and C-terminal tag cloning primer sequences). Six million HEK293Tc18 cells (ATCC CRL-10852) were plated per 15-cm plate and transfected after 24 hours by standard calcium-phosphate transfection protocols with 25 μg of plasmid DNA. Cellular medium was replaced 24 hours after transfection, and cells were harvested in PBS by trituration 48 hours after transfection. Cells were centrifuged and resuspended at approximately 5 million cells/ml in 20 mM sodium phosphate pH 7.65, 250 mM NaCl, 30 mM imidazole (HisTrap Lysis Buffer) plus 1× protease inhibitor (Sigma-Aldrich, P8465). Cells were lysed by 3× snap-freezing in a dry ice/ethanol bath and rapid thawing at 37°C. Lysates were clarified by centrifugation at 10,000 g for 10 minutes at 4°C, and then supernatants were filtered through a Whatman 25 mm GD/X PES 5-μm filter before storage at –80°C. Clarified and filtered lysates were loaded onto two 1-ml GE HisTrap HP columns (in-series) using a GE AKTApurifier with UNICORN software (GE v5.11) running with HisTrap Lysis Buffer. Loaded HisTrap columns were washed with 10 ml of HisTrap Wash Buffer (20 mM sodium phosphate pH 7.65, 500 mM NaCl, 35 mM imidazole), and proteins were eluted with HisTrap Elution Buffer (20 mM sodium phosphate pH 7.65, 250 mM NaCl, 400 mM imidazole). Protein-containing fractions were then dialyzed into DNMT3A Storage Buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.65, 100 mM glycine, 10% glycerol [v/v]) and stored at –80°C. Protein concentrations were determined by Pierce BCA Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and validated by quantitative Western blot; fraction purity was confirmed using SYPRO Ruby protein gel stains (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Table 2. Mutagenesis and C-terminal tag cloning primer sequences.

Western blotting.

Protein samples were separated by SDS-PAGE using NuPAGE (Thermo Fisher Scientific) gels and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (GE Amersham). Membranes were blocked with Western blocking solution (5% nonfat dry milk in Tris-buffered saline with Tween-20 [TBST]) for at least 1 hour at room temperature or at 4°C for 16 hours, then probed with primary antibodies in Western blocking solution for either 2 hours at room temperature or 16 hours at 4°C. Membranes were rinsed 3 times in TBST and then incubated with horseradish-peroxidase–conjugated anti-rabbit (1:5000; GE NA9340V) or anti-mouse (1:5000; GE NXA931) secondary antibodies for 1 hour at room temperature. Membranes were then washed 5 times in TBST, after which ECL (Bio-Rad Clarity Western ECL) was applied according to the manufacturer’s protocols; then membranes were imaged with a Thermo Fisher Scientific myECL Imager. The primary antibodies used were as follows: anti-DNMT3A (1:2000, Cell Signaling Technology, D23G1/3598), anti-FLAG (1:2000, Sigma-Aldrich, F1804), and anti-V5 (1:2000, Thermo Fisher Scientific, R960-25).

In vitro methylation.

In vitro methylation reactions were performed on EcoRI-linearized pcDNA3.1+ vector (Thermo Fisher Scientific, V790-20). Reactions were carried out in 35 μl at 37°C, including 20 mM HEPES pH 7.65, 30 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM DTT, 1 mM EDTA, 0.2 mg/ml BSA, and 5 μM 3H-labeled SAM (Perkin-Elmer) plus DNA substrate and purified recombinant DNMT3A enzyme. To stop the reactions, they were added to 35 μg tRNA carrier (Sigma-Aldrich) in borosilicate tubes on ice, then quenched with 100-fold ice-cold 10% TCA. DNA was allowed to precipitate for 10 minutes. Samples were then spotted onto Whatman GF/C 25-mm filters on a 30-well multi-plater, and washed with 2 ml ice-cold 10% TCA, then 2 ml of 95% ethanol once, after which they were dried and measured using a scintillation counter.

AlphaLISA assays.

Two-and-a-half million HEK293Tc18 cells were plated per 10-cm plate and transfected after 24 hours by standard calcium-phosphate transfection protocols with 8 μg of plasmid DNA (expression vectors from above with C-terminal V5- or FLAG-tags). Cellular medium was replaced 24 hours after transfection, and cells were harvested in PBS by trituration 48 hours after transfection. Cells were centrifuged and resuspended at approximately 5,000 cells/μl in PBS plus 1× protease inhibitor (Sigma-Aldrich, P8465). Cells were lysed by 3× snap-freezing in a dry ice/ethanol bath and rapid thawing at 37°C. Lysates were clarified by centrifugation at 10,000 g for 10 minutes at 4°C, and then supernatants were aliquoted and stored at –80°C. To correct for transfection efficiency and protein stability across lysate samples, total FLAG- or V5-tagged DNMT3A was assessed via quantitative anti-DNMT3A Western blots such that accurate mixing (2:1, 1:1, 1:2, etc.) of FLAG- and V5-tagged DNMT3A could be achieved. AlphaLISA assays were performed in either 96- or 384-well plates (PerkinElmer catalog 6005560 and 6008350). For 96-well assays, lysates were diluted in PBS + 1% FBS to 1,000 normalized (see above) cell equivalents/5 μl, and FLAG- and V5-tagged DNMT3A lysates were mixed at desired ratios and brought to a final volume of 20 μl (in PBS + 1% FBS) with 2,000 total (FLAG-tagged + V5-tagged) normalized cell equivalents. Mixed lysates were incubated for 120 minutes at 4°C in sealed PCR tubes, then transferred to the 96-well plates. AlphaLISA anti-FLAG donor (PerkinElmer catalog AS103) and anti-V5 acceptor (PerkinElmer catalog AL129) beads were mixed in PBS + 1% FBS to make a master-mix with 40 μg/ml of each bead, and 20 μl of bead master-mix was added to each sample in the 96-well plate 15 minutes prior to analysis. For 384-well assays, lysates were diluted in PBS + 1% FBS to 250 normalized (see above) cell equivalents/5 μl, and FLAG- and V5-tagged DNMT3A lysates were mixed at desired ratios to a final volume of 10 μl (in PBS + 1% FBS) with 500 total (FLAG-tagged + V5-tagged) normalized cell equivalents. Mixed lysates were incubated for 120 minutes at 4°C in sealed PCR tubes, then transferred to the 384-well plates. AlphaLISA anti-FLAG donor (PerkinElmer catalog AS103) and anti-V5 acceptor (PerkinElmer catalog AL129) beads were mixed in PBS + 1% FBS to make a master-mix with 60 μg/ml of each bead, and 5 μl of bead master-mix was added to each sample in the 384-well plate 15 minutes prior to analysis. For assays testing effects of NaCl or KCl on DNMT3A oligomerization, PBS + 1% FBS used for dilution of input lysates was replaced with 1.06 mM potassium phosphate (monobasic), 2.97 mM sodium phosphate (dibasic) pH 7.4 + 1% FBS, with appropriate NaCl or KCl required to achieve desired final concentrations. AlphaLISA plates were analyzed using a BioTek Synergy 2-plate reader, with a 680/20 nm excitation filter and a 620/20 nm emission filter.

Coimmunoprecipitation.

Two-hundred-and-fifty-thousand HEK293Tc18 cells were plated per well of a 6-well plate and transfected after 24 hours by standard calcium-phosphate transfection protocols with 2 μg of plasmid DNA. Cellular media was replaced 24 hours after transfection, and cells were harvested in PBS by trituration 48 hours after transfection. Cells were pelleted by centrifugation at 400 g for 5 minutes at 4°C and then resuspended at 1 million cells/ml in PBS plus 1× protease inhibitor (Sigma-Aldrich, P8465). Cells were lysed by 3× snap-freezing in a dry ice/ethanol bath and rapid thawing at 37°C. Lysates were clarified by centrifugation at 10,000 g for 10 minutes at 4°C, and supernatants were stored at –80°C. DNMT3A abundance was assessed by quantitative Western blotting using 100,000 cell equivalents per sample, allowing effective concentrations of total DNMT3A in each lysate to be normalized between conditions. Aliquots of WT DNMT3A-FLAG lysates (200,000 cell equivalents) were mixed with either an equal abundance of DNMT3A-V5 (either WT, Q515*, E616fs, or L723fs) or equivalent protein from untransfected cells and brought to a total volume of 600 μl in PBS, mixed with 20 μl prepared anti-FLAG M2 magnetic beads (Sigma-Aldrich, M8823), and rotated for 16 hours at 4°C. After immunoprecipitation, the beads were washed 3× with 1 ml PBS with 1× protease inhibitor cocktail, and proteins were eluted with 0.1 M glycine HCl, pH 3.0. Western blot bands at approximately 64 kD and 26 kD represent coelution of heavy and light chains of immunoprecipitation IgG, recognized by Western blot secondary antibody.

Primary AML samples.

All cryopreserved primary AML samples (TCGA ID nos. 2839, 2851, 2879, 2993) were collected. Primary AML cells from bone marrow (cryopreserved in 10% DMSO) were quickly thawed in the presence of a 1× protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich, P8465) and 1 mM PMSF (Sigma-Aldrich, 10837091001) resuspended in 10 ml of PBS with 20% FBS with 1× protease inhibitor cocktail and 1 mM PMSF and centrifuged at 400 g for 5 minutes at 4°C. Cells were lysed for 10 minutes on ice, at 5 million per 100 μl, in ice-cold RIPA buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 89900) with 1× protease inhibitor cocktail and 1 mM PMSF. Lysates were centrifuged at 10,000 g for 5 minutes at 4°C, and supernatants were collected and stored at –80°C after quantification by BCA assay. Western blots of primary samples were performed with 120 μg total protein per sample for DNMT3A detection and 1 μg total protein per sample for actin detection.

Mice.

Dnmt3a+/– mice (17) were obtained from the Mutant Mouse Regional Resource Centers repository (MMRRC Strain Name B5.129S4-Dnmt3atm2Enl/Mmnc) and were backcrossed for more than 10 generations in the B6 strain prior to use in these studies. Whenever possible, littermate controls were used for all experiments.

Bone marrow harvest and transplantation.

Bone marrow was harvested from femurs, tibias, pelvi, and humeri of mice. After lysis of red blood cells (ACK buffer: 0.15 M NH4Cl, 10 mM KHCO3, 0.1 mM Na2EDTA), cells were washed with FACS buffer, filtered through 50-μm cell strainers (Partek), and resuspended in PBS at 1 million cells/100 μl for transplantation. For competitive transplant experiments, bone marrow was mixed 50:50 with freshly harvested cells from 6-week-old Ly5.1x5.2 mice (The Jackson Laboratory). Transplantation was performed by retroorbital injection of 1 × 106 total bone marrow cells into lethally irradiated Ly5.1 recipients that had received 2 split doses of 550 cGy total body irradiation spaced at 4 hours (Mark 1 Cesium-137 irradiator, JL Shepherd) 24 hours prior to transplantation. For tumor transplants, recipient Ly5.1 mice were sublethally irradiated (600 cGy) and retroorbitally injected with 1 million tumor cells.

Intracellular DNMT3A staining.

Intracellular DNMT3A was detected with the BD Biosciences — Pharmingen Transcription Factor Buffer Set 562574 according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, bone marrow cells were isolated from femurs and tibias and lysed with red cell lysis buffer. Cells were stained with cell-surface markers to identify cell type by flow cytometry and then fixed for 40 minutes at 4°C. Cells were washed with perm wash buffer and incubated with primary antibody against DNMT3A (1:400 dilution, D23G1, Cell Signaling Technology) for 30 minutes at 4°C. Cells were rinsed in perm wash buffer and incubated in secondary antibody (1:500 dilution, chicken anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 647, Molecular Probes) for 30 minutes at 4°C. Cells were rinsed in perm wash buffer and analyzed by flow cytometry. The mean fluorescence intensity was calculated for the AF647 signal, and values were normalized against the values of each bone marrow compartment for the first Dnmt3a+/+ mouse in each experiment set.

Mouse analysis and tumor watch.

Peripheral blood counts were assessed at regular intervals, as indicated, by automated CBC (Hemavet 950, Drew Scientific Group). For long-term tumor watch experiments, mice were monitored daily and animals displaying signs of illness (lethargy, hunched posture, ruffled fur, dyspnea, or pallor) were euthanized and spleen and bone marrow harvested for analysis. Diagnosis of leukemia was made by light microscopic examination of spleen and/or peripheral blood cells according to the Bethesda criteria. Cytospin tissue slides were stained with Wright-Giemsa stain (Sigma-Aldrich) and were imaged using a Nikon MICROPHOT-SA microscope equipped with an oil-immersion ×50/0.90 or ×100/1.30 objective lens (Nikon Corp.). The tumor watch was terminated after 2 years.

Methylcellulose colony formation assay.

Ten thousand cells per plate were plated in triplicate in M3534 MethoCult media containing IL-3, IL-6, and stem cell factor (SCF) (Stem Cell Technologies) and incubated at 37°C for 1 week. Each week, clusters of cells meeting the morphologic criteria for CFU-GEMM, CFU-GM, CFU-G, or CFU-M (http://www.stemcell.com/~/media/Technical%20Resources/8/3/E/9/0/28405_methocult%20M.pdf?la=en) were counted as myeloid colonies and cells were lifted using warm DMEM media + 2% FBS, spun down, and replated as before. An aliquot of cells was taken for analysis of myeloid markers by flow cytometry.

Cell staining and flow cytometry.

After ACK lysis of red blood cells, peripheral blood, bone marrow, or spleen cells were treated with anti-mouse CD16/32 (clone 93, eBioscience) and stained with the indicated combinations of the following antibodies (all antibodies are from eBioscience unless indicated): CD34 FITC (clone RAM34), CD11b PE or APC-e780 (clone M1/70), c-kit PerCP-Cy5.5 or APC-e780 (clone 2B8), CD115 APC or PE (clone AFS98), Gr-1 Pacific blue (Invitrogen, clone RM3028), Gr-1 biotin (clone RB6-8C5), B220 PE, APC, or biotin (clone RA3-6B2), CD3 e450 or PE (clone 145-2C11), CD71 PE(clone R17217), Ter-119 Pacific blue (clone TER-119), CD16/32 APC (clone 93), Flk2 APC (clone A2F10), CD150 PE (BioLegend 115903, clone TC15-12F12.2), Ly5.1 PE or FITC (clone A20), Ly 5.2 APC or e450 (clone 104), and streptavidin 605 NC (clone 93-4317-42). The following flow phenotypes were used for stem and progenitor cell flow: Lin– (lineage negative): B220–, CD3e–, Gr-1–, Ter-119–; KLS: Lin–, Sca-1+, c-Kit+; KLS-SLAM: Lin–, Sca-1+, c-Kit+, CD150+; LT-HSC: Lin–, Sca-1+, c-Kit+, CD34–, Flk2–; MPP: Lin–, Sca-1+, c-Kit+, CD34+; GMP: Lin–, Sca-1–, c-Kit+, CD34+, CD16/32+; CMP: Lin–, Sca-1–, c-Kit+, CD34+, CD16/32–; and MEP: Lin–, Sca-1–, c-Kit+, CD34–, CD16/32–. Analysis was performed using a FACScan (Beckman Coulter) or I-Cyt Synergy II Aorter (I-Cyt Technologies) and data analyzed using FlowJo (Tree Star), Excel (Microsoft), and Prism 5 (GraphPad).

Single cell RNA-seq.

cDNA libraries were prepared from individual cells using the Chromium Single Cell 3′ Solution from 10× Genomics (including the Chromium Single Cell 3′ Chip Kit v2 [PN-120236], Library & Gel Bead Kit v2 [PN-120237], and Chromium i7 Multiplex Kit [PN-120262]), according to the instructions in the Chromium Single Cell 3′ Reagent Kits v2 User Guide, Rev A (31). cDNA libraries were sequenced on the Illumina HiSeq 25001T in Rapid Run mode. All analyses were performed using R 3.3.1 and Cell Ranger 1.3.1. Cell Ranger was used to demultiplex and align the sequencing reads, correct and count the UMIs for each gene in each cell, normalize the data to account for differences in sequencing depth across samples, exclude genes with 0 UMI counts, and normalize each cell to the median (using normalize_barcode_sums_to_median). We assigned each cell in the data set to one of 13 hematopoietic lineages by training a k-Nearest Neighbors algorithm on expression data from Haemopedia (http://haemosphere.org/), an atlas of microarray expression data for 54 murine cell types, spanning all mature hematopoietic cell lineages and several progenitor populations (32). Specifically, we constructed a reference matrix of expression profiles, where each column represents one of the 54 cell types and each row represents one of 2,978 lineage-specific genes (32). We extracted single-cell RNA-seq data for the 2,353 lineage-specific genes that are measurably expressed in our data. We calculated Spearman correlations between the cells from our single-cell data sets and each cell type in the reference matrix, ranked the reference cell types by correlation, and chose the top 3. We assigned a cell to a lineage if at least 2 of the top 3 reference cell types belonged to that lineage. Cells with fewer than 200 measured genes were not assigned a lineage. Fisher’s exact test (with Bonferroni’s correction) was used to compare the proportion of cells assigned to a given lineage in each sample. Using Cell Ranger 1.3.1, median-normalized expression data were clustered using the k-means algorithm (k = 10). Cluster-specific (or sample-specific) genes were identified by applying the “sseq” differential expression method to the unnormalized data, and by requiring a fold-change of at least 2 between the clusters (samples). t-SNE plots were created using Cell Ranger 1.3.1. Data were deposited into the NCBI’s Sequence Read Archive (SRA BioProject PRJNA392335).

Whole-genome bisulfite sequencing and analysis.

Bisulfite sequencing was performed using whole-genome bisulfite-converted sequencing libraries generated with the Epigenome library preparation kit. DNA was isolated using a QiaAmp DNA Mini Kit (QIAGEN 51304). Input DNA (200 ng) from each sample was bisulfite converted using the DNA Methylation Gold Kit (Zymo Research). The converted single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) was eluted into 27 μl. Each sample underwent 4 individual library preps, 9 μl/library prep, using the EpiGnome TruSeq DNA Methylation Kit (Illumina EGMK81312). Library prep was completed per the manufacturer’s protocol. After library prep, all 4 reactions for each sample were pooled and quantified by dsDNA HS Qubit (Life Technologies Q32851) and sized with the High Sensitivity DNA Chip Kit (Agilent 5067-4626). Samples were assayed by quantitative PCR (qPCR), and on the basis of qPCR results, diluted to a 2 nM solution. Indexed sequencing was performed on Illumina HiSeq 2000 or 25001T instruments and reads were mapped with BSMap (version 1.037) using default parameters (44). Methylation ratios were obtained using the methratio.py script. The program “metilene” (45) was used to analyze the raw methylation ratios at all CpGs to identify DMRs with more than 10 CpGs and a mean methylation difference between the same groups of more than 0.2. DMRs were filtered to retain those with an FDR of less than 0.05, and adjacent DMRs less than 50 bp apart were merged. Following these procedures, methylation data from individual CpGs were imported into R as bsseq objects (46) for manipulation and analysis, which included “smoothing” using the BSmooth function with the parameters ns = 35 and h = 500 to impute missing methylation values for visualization; all statistical procedures and analysis used raw methylation ratios (or methylation counts) from individual CpGs or summed data for DMRs. Data were deposited into NCBI’s SRA (BioProject PRJNA392335).

Illumina library construction and exome sequencing.

Genomic DNA from all tumor samples and/or matched normal samples were fragmented using a Covaris LE220 DNA Sonicator (Covaris) within a size range between 100 and 400 bp using the following settings: volume = 50 μl, temperature = 4°C, duty cycle = 20, intensity = 5, cycle burst = 500, time = 120 seconds. The fragmented samples were transferred from the Covaris plate and dispensed into a 96-well Bio-Rad Cycle plate by a CyBio-SELMA instrument. Small insert dual indexed Illumina paired-end libraries were constructed with the KAPA HTP Sample Prep Kit (KAPA Biosystems) on the SciClone instrument (PerkinElmer) according to the manufacturers’ recommendations. Dual indexed adaptors were incorporated during ligation; the same 8-bp index sequence is embedded within both arms of the library adaptor. Libraries were enriched with a single PCR reaction for 8 cycles. The final size selection of the library was achieved by a single AMPure XP Paramagnetic Bead (Agencourt, Beckman Coulter Genomics) cleanup targeting a final library size of 300 to 500 bp. The libraries underwent a qualitative (final size distribution) and quantitative assay using the HT DNA Hi Sens Dual Protocol Assay with the HT DNA 1K/12K chip on the LabChip GX instrument (PerkinElmer). Libraries were captured using the Nimblegen SeqCap EZ Library Reagent. The final concentration of each capture pool was verified through qPCR utilizing the KAPA Library Quantification Kit — Illumina/LightCycler 480 kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Kapa Biosystems) to produce cluster counts appropriate for the Illumina HiSeq2000 platform. Each capture pool was loaded on the HiSeq2000 version 3 flow cell according to the manufacturer’s recommendations (Illumina). For each sample, 2 × 101 bp read pairs were generated, yielding approximately 7 to 25 Gb of data per tumor sample and 4 to 16 Gb per normal sample. Data were deposited into the NCBI’s SRA (BioProject PRJNA392335).

Variant detection pipeline.

Sequence data were aligned to mouse reference sequence mm9 (with the OSK vector sequence added) using bwa version 0.5.9 (47) (parameters: -t 4 -q 5::). Bam files were deduplicated using picard version 1.46. Single nucleotide variants (SNVs) were detected using the union of 3 callers: (a) samtools version r963 (48) (parameters: -A -B) intersected with Somatic Sniper version 1.0.2 (49) (parameters: -F vcf -q 1 -Q 15) and processed through false-positive filter v1 (parameters: --bam-readcount-version 0.4 --bam-readcount-min-base-quality 15 --min-mapping-quality 40 --min-somatic-score 40) (b) VarScan version 2.2.6 (50) filtered by varscan-high-confidence filter version v1 and processed through false-positive filter v1 (parameters: --bam-readcount-version 0.4 --bam-readcount-min-base-quality 15 --min-mapping-quality 40 --min-somatic-score 40), and (c) Strelka version 0.4.6.2 (51) (parameters: isSkipDepthFilters = 1). Indels were detected using the union of 4 callers: (a) GATK somatic-indel version 5336 (52) filtered by false-indel version v1 (parameters: --bam-readcount-version 0.4 --bam-readcount-min-base-quality 15), (b) pindel version 0.5 (53) filtered with pindel false-positive and vaf filters (parameters: --variant-freq-cutoff=0.08), (c) VarScan version 2.2.6 (50) [filtered by varscan-high-confidence-indel version v1 then false-indel version v1 (parameters: --bam-readcount-version 0.4 --bam-readcount-min-base-quality 15), and (d) Strelka version 0.4.6.2 (51) (parameters: isSkipDepthFilters = 1). Variants were filtered using a Bayesian classifier (https://github.com/genome/genome/blob/master/lib/perl/Genome/Model/Tools/Validation/IdentifyOutliers.pm), retaining variants classified as somatic with a binomial log-likelihood of at least 5. Manual review also resulted in the removal of all variants in the region chr1:90,100,000–151,800,000, which appeared to be artifacts. Putative variants that differed significantly from the expected homozygous or heterozygous ratios were removed using an R script (https://raw.githubusercontent.com/genome/genome/master/lib/perl/Genome/Model/Tools/Analysis/RemoveContaminatingVariants.R). The Dnmt3a locus was manually inspected for mutations, insertions, and deletions by displaying sequencing data in the Integrated Genomics Viewer and subsequently analyzed for copy number changes using CopyCat2, which compares exome sequence against a pooled normal control for detection of CNVs (https://github.com/abelhj/cc2/). Additional copy number analysis was performed using Varscan 2.3.6 (50) and segmented with the DNAcopy package (54). Segments of less than 50 probes were filtered to remove noise, followed by merging of adjacent segments with absolute copy number difference of less than 0.2. The Dnmt3a locus was manually reviewed for copy number alterations using both the raw and segmented data.

Exon array gene expression analysis.

For expression array profiling, total cellular RNA was purified using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen), quantified using UV spectroscopy (Nanodrop Technologies), and qualitatively assessed using an Experion Bioanalyzer. Amplified cDNA was prepared from 20 ng total RNA using the whole transcript Ovation RNA Amplification System and biotin labeled using the Encore Biotin Module, both from NuGen Technologies, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Labeled targets were then hybridized to Mouse Exon 1.0 ST arrays (Affymetrix), washed, stained, and scanned using standard protocols from the Siteman Cancer Center, Molecular and Genomic Analysis Core Facility (https://pathology.wustl.edu/research/core-facilities/biomedical-informatics-cmbi/). Affymetrix Expression Console software was used to process array images, export signal data, and evaluate image and data quality relative to standard Affymetrix quality control metrics. Affymetrix CEL files were imported into Partek Genomics Suite 6.6 (Partek Inc.). Probe-level data were preprocessed, including background correction, normalization, and summarization, using robust multiarray average (RMA) analysis. RMA adjusts for background noise on each array using only perfect match (PM) probe intensities and subsequently normalizes data across all arrays using quantile normalization (55, 56), followed by median polish summarization to generate a single measure of expression (56). Data were filtered to include only core probe sets having a raw expression signal greater than 200 in all samples in order to limit the analysis within well-annotated exons. The ANOVA and multi-test correction for P values in the Partek Genomics Suite were used to identify differentially expressed genes. Sample genotypes (Dnmt3a+/+, Dnmt3a+/–, Dnmt3a–/–) were chosen as the candidate variables in the ANOVA model to obtain genotype-specific expression changes. ANOVA P values were corrected using Bonferroni’s method. The list of genes with significant variation in expression levels was generated on the basis of a fold change of 2 and a 0.05 FDR criterion as a significant cutoff. Data were deposited into the NCBI’s Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO GSE100702).

Supplemental figures.

Supplemental Figure 1 shows Dnmt3a protein levels in Dnmt3a+/– mice. Supplemental Figure 2 shows normal hematopoiesis of young Dnmt3a+/– mice. Supplemental Figure 3 shows representative flow phenotyping of secondary tumors. Supplemental Figure 4 shows methylation data from a locus that is differentially methylated in both Dnmt3a–/– and Dnmt3a+/– bone marrow cells. Supplemental Figure 5 shows a representation of expression array data from the purified KLS cells of Dnmt3a+/+ versus Dnmt3a+/– cells. Supplemental Figure 6 shows the 10 k-means clusters overlaid on the t-SNE plot of the single cell RNA-seq from this study and the genes that are most differentially expressed within each cluster.

Supplemental tables.

Supplemental Table 1 shows DNA and RNA VAFs for DNMT3A truncation mutants. Supplemental Table 2 shows detailed Bethesda criteria and flow cytometry characteristics of murine tumors. Supplemental Tables 3, 4, and 5 show SNVs from exome sequencing of 3 Dnmt3a+/– tumors. Supplemental Table 6 shows the VAFs of activated Ras mutations detected in AML samples. Supplemental Table 7 shows a list of all genes on the copy number–altered regions of tumor E that may be relevant for AML pathogenesis. Supplemental Table 8 shows the locations of all significant DMRs detected between Dnmt3a+/+ and Dnmt3a–/– mice, with methylation values of the DMRs. Mean methylation values for the same DMRs are also shown for all Dnmt3a+/– samples by age of harvest. Supplemental Table 9 shows the average, median, and maximal number of sequencing reads from each of the genes used to assign cells to the myeloid lineage, for Dnmt3a+/+ (WT) versus Dnmt3a+/– (3a het) cells.

Statistics.

All statistical comparisons were made using GraphPad Prism 5 software, except for statistics on sequencing data, which were calculated using the R statistical programming software as described above. Statistical tests employed and significance cut-offs are detailed in each figure legend. All data represent mean ±SD or SEM, as specified in figure legends.

Study approval.

All mouse experiments were performed in accordance with institutional guidelines and current NIH policies and were approved by the Animal Studies Committee of Washington University. All cryopreserved primary AML samples (TCGA ID nos. 2839, 2851, 2879, 2993) were collected as part of a study approved by the Human Research Protection Office at Washington University School of Medicine after patients provided informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Author contributions

CBC, DARG, AMV, SK, NMH, AMS, CVB, and MG performed the experiments. CBC, DARG, AMV, SK, NMH, MG, JMK, GSC, AAP, CAM, and TJL interpreted the data. SOL, CF, and RF provided technical assistance and access to essential equipment. CBC, DARG, SK, and TJL designed the experiments and wrote the paper.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants T32-HL007088 to CBC and DARG as well as CA101937, CA197561, and a Barnes-Jewish Hospital Foundation grant (00335-0505-02) to TJL. The authors thank Mieke Hoock for superb animal husbandry support for the study and David Spencer for important support and helpful discussions.

Version 1. 09/01/2017

Electronic publication

Version 2. 09/20/2017

Print issue publication

Funding Statement

PRE-AND POSTGRADUATE TRAINING IN MOLECULAR HEMATOLOGY

NATIONAL RESEARCH SCIENCE AWARD - MEDICAL SCIENTIST TRAINING PROGRAM

R01 DNMT3A MUTATIONS IN ACUTE MYELOID LEUKEMIA

R35 MOLECULAR PATHOGENESIS OF ACUTE MYELOID LEUKEMIA

Footnotes

CBC’s present address is: Department of Medicine, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

AMV’s present address is: Department of Pathology, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

CVB’s present address is: The Ohio State University School of Medicine, Columbus, Ohio, USA.

Conflict of interest: The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

Reference information: J Clin Invest. 2017;127(10):3657–3674.https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI93041.

Contributor Information

Shamika Ketkar, Email: sketkar@go.wustl.edu.

Mindy Guo, Email: mindyguo@wustl.edu.

Jeffery M. Klco, Email: Jeffery.Klco@STJUDE.ORG.

Shelly O’Laughlin, Email: mharriso@wustl.edu.

Catrina Fronick, Email: cfronick@wustl.edu.

Robert Fulton, Email: bfulton@genome.wustl.edu.

Gue Su Chang, Email: gchang@wustl.edu.

References

- 1.Ley TJ, et al. DNMT3A mutations in acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(25):2424–2433. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1005143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walter MJ, et al. Recurrent DNMT3A mutations in patients with myelodysplastic syndromes. Leukemia. 2011;25(7):1153–1158. doi: 10.1038/leu.2011.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]