Supplemental Digital Content is available in the text

Keywords: community health services, cross-sectional study, gatekeeper policy, satisfaction

Abstract

To assess the effects of the gatekeeper policy implemented in Shenzhen, China, in conjunction with a labor health insurance program, on channeling patients toward community health centers (CHCs).

Eight thousand patients who visited 8 CHCs in Shenzhen were surveyed between May 1, 2013 and July 28, 2013. Half of the patients were subject to gatekeeper policy and the other half of them were not. Structured questionnaire was used to collect patients’ choices of initial medical institution, use of CHCs and their satisfaction with health care. Bivariate and regression analyses were used to compare patient's choice, utilization, and satisfaction of CHCs.

Compared with patients who were free to seek medical care at any place, patients with gatekeepers were 1.77 (95% CI 1.37–2.30) times more likely to choose CHCs first when seeking care. In the past year, the group with gatekeeper made 0.88 more visits to CHCs in the past year than the group without gatekeeper (P < .01), controlling for influencing factors. The 2 groups were equally satisfied with all satisfaction measures except for “waiting time,” which was higher among patients without gatekeepers (P < .01).

Our study indicates that, as repeatedly proven in other parts of the world, gatekeeping is effective in orienting patients toward primary care system. Along with increased efforts in rebuilding China's primary care network and expanding health insurance coverage, implementation of gatekeeper policy may help increase access to care, reduce inappropriate use of health resources, and strengthen primary care institutions.

1. Introduction

China once had a widespread, 3-tiered healthcare system that offered preliminary yet comprehensive, equitable health services to all. Albeit poorly equipped and poorly financed, the system relied heavily on the first-tier, a network of community health centers (CHCs) and their satellite stations that reached everyone. The primary care-centric system was accredited for drastically reducing communicable diseases and improving overall health and life expectancy in a short time in China.[1] However, this system, which depended on public financing, collapsed quickly after China started the market-oriented economic reforms in the early 1980s and the reduced role of government in financing and regulating the health care sector.[2,3] The disintegration of the community healthcare network and fragmented health care delivery system resulted in dual problems: lack of access to basic care in general and lack of affordability when patients have to seek care in hospitals in cities.[4] As the overall economy improves, China has been making great efforts in rebuilding its community health system for over a decade, for instance, investing in substantial amount of financial resources for establishing CHCs and community health stations, training primary care providers, enabling supply of essential medicines, and equipment.[5,6] At the same time, the government has initiated and supported the establishment of public–private partnership health insurance schemes, notably, the New Rural Cooperative Medical System in rural areas and Labor Health Insurance System in urban areas.[7]

Despite these many efforts, the “too difficult and too expensive to see a doctor” remains the biggest complain among patients in China.[8,9] A persistent problem exacerbating health care access and affordability is the population's distrust of community health facilities.[10] The general perceptions among patients are that CHCs and stations lack well-trained healthcare providers, medicines, and equipment, and therefore, they provide poor care. Such perceptions lead patients to crowd large, famous hospitals, and renowned specialists. This tendency not only increases the overall access difficulties, but also threatens the financial sustainability of community health facilities since revenues from providing care, paid by insurance and patients, is expected to cover substantial portions of their operational expenses.

To address this complicated problem, Chinese government has been experimenting with gatekeeper policy.[11] Essentially, a gatekeeper system requires a patient to visit a primary care provider first, and the patient needs to get his or her primary care provider's referral before seeing a specialist or going to a hospital. This policy is widely implemented in tax-funded health systems, such as those in the United Kingdom and Spain, and in other social health insurance systems, such as those in Switzerland and the Netherlands.[12–15] This policy orients a health system toward primary care by channeling patients and health resources to primary care providers.[16,17] Researchers have repeatedly proven that this policy improves care continuity and coordination, and reduces inappropriate use of special care and hospitalization, and reduces overall health expenditure; however, patients are not necessarily dissatisfied because of restrictions on their choices.[18–20] As with most gatekeeper systems, China's experiment on gatekeeper policy centered primarily around payment policy and compulsory referral mechanism: only a patient does seek care from a community health facility, or was referred by designated CHC, his or her health insurance covers all or a substantial portion of the charge; or he or she pays all of charges out-of-pocket.[21,22]

Since the Ministry of Health issued in 2006 a directive endorsing this policy, health administrations in many provinces, districts, and cities had launched various pilot schemes to implement it, mostly in combination with other reforming initiatives aimed at promoting essential medicines use, chronic disease management, health promotion, etc.[23–26] Our previous study showed that patients’ willingness for visiting CHCs is high[27] and another study indicated that patient satisfaction with the gatekeeper policy was low[28], however, the effects of the gatekeeper policy in China and patient satisfaction with community health service between patients with and without gatekeeper policy were not evaluated or compared.

This study was the first attempt. We surveyed a convenient sample of 8000 patients who visited a selected set of CHCs in the city of Shenzhen between May 1, 2013 and July 28, 2013. Two groups of patients were identified, 1 group who had labor health insurance with gatekeeper policy and the other group who had no insurance and therefore were not subject to gatekeeper policy. We compared their choices of first contact, community health services utilization, and satisfaction. Our objective was to understand to what extent the financial incentive-based gatekeeper policy affects the patients’ utilization of community healthcare services.

2. Methods

2.1. Ethical review

Our study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology and was carried out in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. All the respondents were provided with the informed consent form, and were informed that they had the right to participate or refute the investigation. All the questionnaires were filled in by respondents anonymously.

2.2. Study setting and subjects

The study was conducted in the city of Shenzhen, neighboring Hong Kong. It is the first city to start the market-based economic forms in China. As it was a fishing village 30 years ago, the city becomes a symbol of the new economy in China and has witnessed drastic transformation. Migrant workers and their families come from all over the country and account for over 80% of the city's current population. In addition to building a strong community healthcare network to serve the highly mobile populations in the city, Shenzhen government has had great success in building the labor health insurance system. Since 2006, the labor health insurance system has offered coverage to all migrant workers and their families, each enrollee is now bonded to a CHC for all health services and is required to get referral from his or her designated CHC before seeking care elsewhere. Enrollees who seek care without CHC referrals have to pay all charge out-of-pocket. However, a substantial percentage of migrant workers and their families, especially those working for small businesses or self-employed, have no health insurance and pay for their medical care by themselves regardless of where they seek the medical care. These people are free to choose and use any healthcare facility, or forgo care, depending on their financial ability, but are not subject to any gatekeeping restriction.

To investigate how the gatekeeper policy affects the patients’ utilization of CHCs, we conducted a cross-sectional study and selected 4 street zones of Bao’an District, a district containing more than 60% of the labors of Shenzhen. In each zone, we randomly selected 2 CHCs and obtained their collaboration for this study. At each selected CHC, 1000 patients were intercepted and interviewed after they completed their visits, of whom 500 were patients with the labor health insurance policy and 500 were self-pay patients. The inclusion criteria for participants were as follows: patients who were over 18 years old; patients who had the ability to identify their own physical conditions and judge their health care experience. The survey was conducted between May and July in 2013, with a targeted total sample of 8000 patients. There were 7911 valid questionnaires and 89 questionnaires were excluded with the lack of large amounts of data, of the 7911 subjects, 150 were excluded with the lack of socio-demographic data or aged below 18 years old. Finally, 7761 patients were included in the database.[27]

2.3. Questionnaire design and data collection

The questionnaire was first developed by reviewing similar literatures and improved through group discussions and mock interviews. We then conducted a pilot survey at a CHC for further refining the questionnaire. The completed questionnaire contains 3 parts: socio-demographic characteristics; health status and care seeking behavior; and satisfaction of care. The satisfaction was scored using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “very dissatisfying” (1) to “very satisfying” (5).

The survey was conducted at the payment service department, which was the last step for each patient visiting a CHC. A staff member from the CHC was responsible to approach a patient who was about to leave the center, provide the patient with an overview of our research, and then request the patients’ willingness to participate in the study before asking the patient to complete the survey questionnaire.

2.4. Statistical analysis

The data was analyzed using SPSS, version 16.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL). We tabulated the characteristics of the respondents and used the t test of 2 independent-samples and χ2 tests to compare the differences between the 2 groups of patients. Logistic regression was carried out to determine the factors significantly associated with the probability of patients choosing CHCs as their first treatment choice. Linear regression was applied to explore the influencing factors of utilization and satisfaction of care at CHCs. All differences were tested using 2-tailed tests and a P value of.05 was considered statistically significant. In the present study, we excluded 874 patients who did not fill in some key questions such as patient's choice of a CHC as the first contact, patient satisfaction, etc. And we also compared the included patients and 7761 patients, and no statistical differences were found about socio-demographic characteristics between the 2 groups (supplementary material Table 1).

3. Results

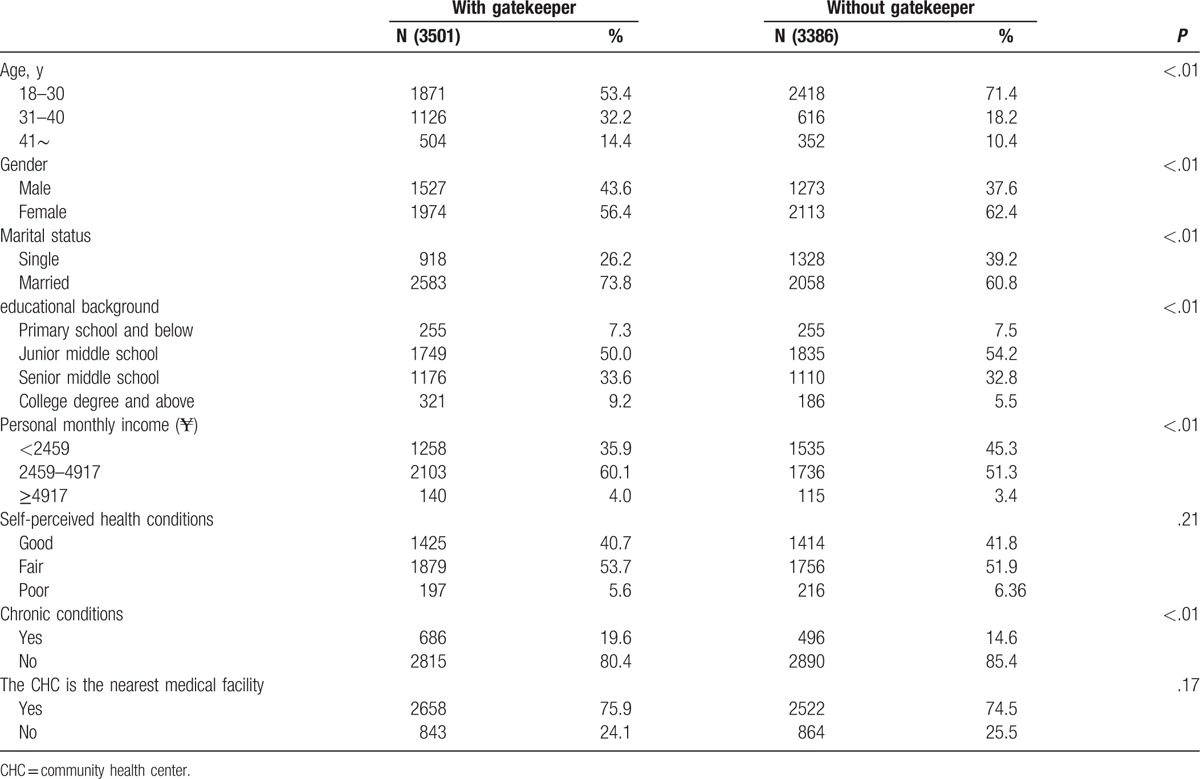

Of the 8000 patients surveyed, 1113 had missing values on key questions and were dropped from the analysis. In total, 6887 questionnaires were eligible for analysis, including 3501 participants in “with gatekeeper” group and 3386 participants in “without gatekeeper” group. Table 1 shows the socio-demographic characteristics of the 2 groups of patients. Compared with the “with gatekeeper” group, the “without gatekeeper” group appeared to be younger, with higher percentage of female (62.4% vs 56.4%, P < .01), less likely to be married (60.8% vs 73.8%, P < .01), with lower income (P < .01), and less likely to have chronic conditions (14.6% vs 19.6%, P < .01). The differences between the 2 groups in self-perceived health conditions and the distances to the nearest CHCs were not statistically significant (P > .05).

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents.

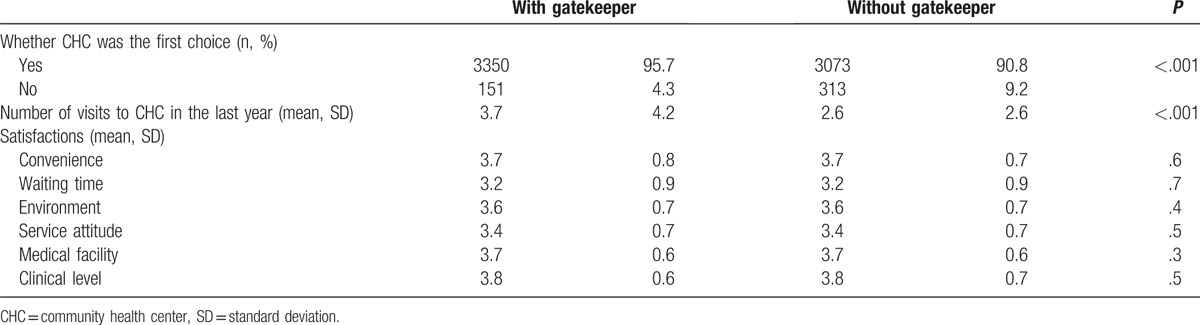

Table 2 shows the results of the bivariate analysis of the differences in 3 indicators of use of community health services. Although over 90% in the both groups considered CHCs as their first choice, this proportion was significantly higher in the with gatekeeper group when compared with the without gatekeeper group (96% vs 91%, P < .01). In accordance with the previous finding, the group with gatekeeper also made 0.88 more visits to CHCs in the past year than the group without gatekeeper. In the meantime, bivariate analysis found no differences in the 6 patient satisfaction measures (P > .05).

Table 2.

Utilization of CHCs in the past year.

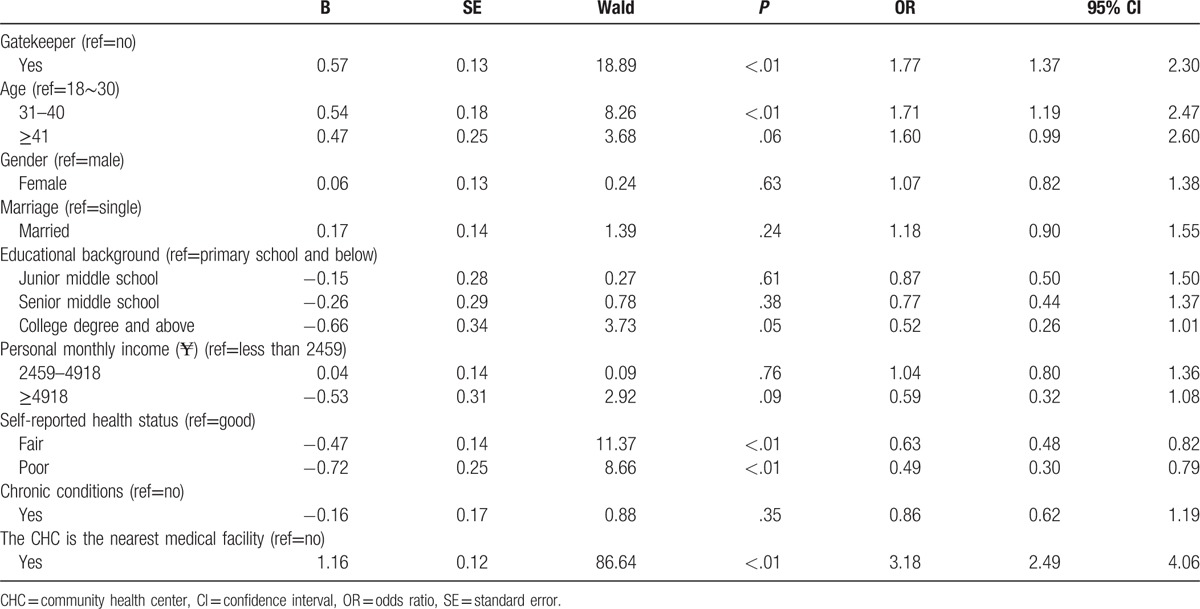

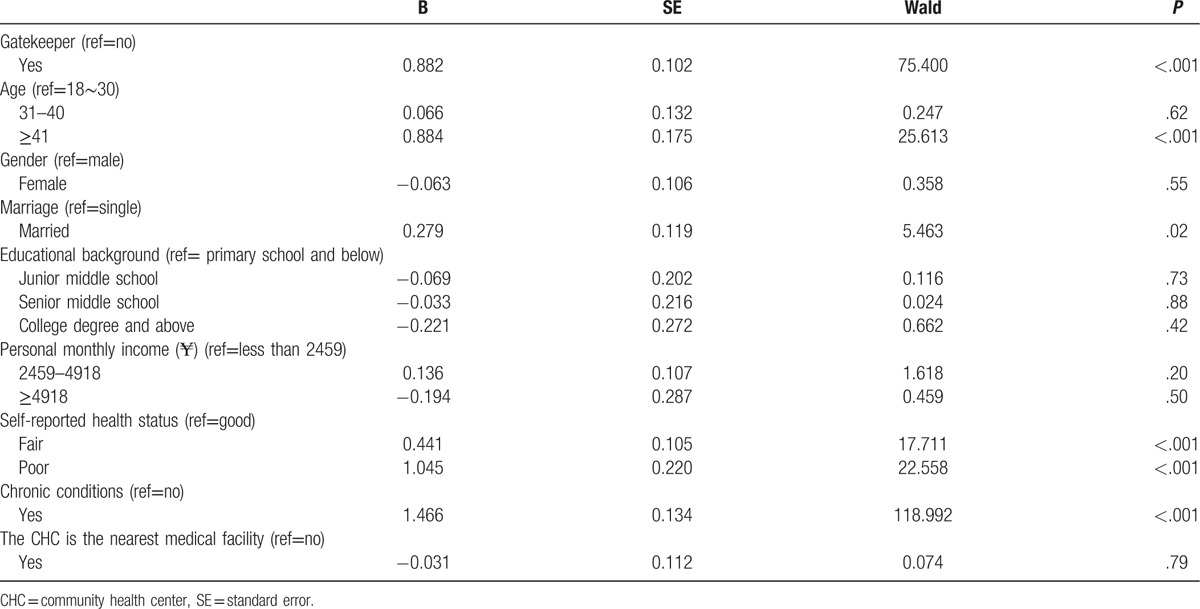

Results show that the OR of gatekeeping on patient's choice of a CHC as the first contact when seeking medical care was statistically significantly (Table 3). Controlling for demographics, income, health status, and the distance to the nearest medical facilities, patients locked with gatekeeper policy were 1.77 (95% CI 1.37–2.30) times more likely to choose CHCs first. The logistic regression also indicated that patients who were older, with healthier and living closer to CHCs were more likely to choose CHCs first. Results reveal that, consistently, patients with gatekeeper visited CHCs more often in the past year, controlling for other factors (Table 4). In addition, older age, poorer health, and chronic conditions were independently associated with higher number of visits to CHCs.

Table 3.

Logistic regression analysis of factors associated with making CHCs as the first choice for healthcare.

Table 4.

Multivariable analysis of factors associated with number of visits to CHCs in the past year.

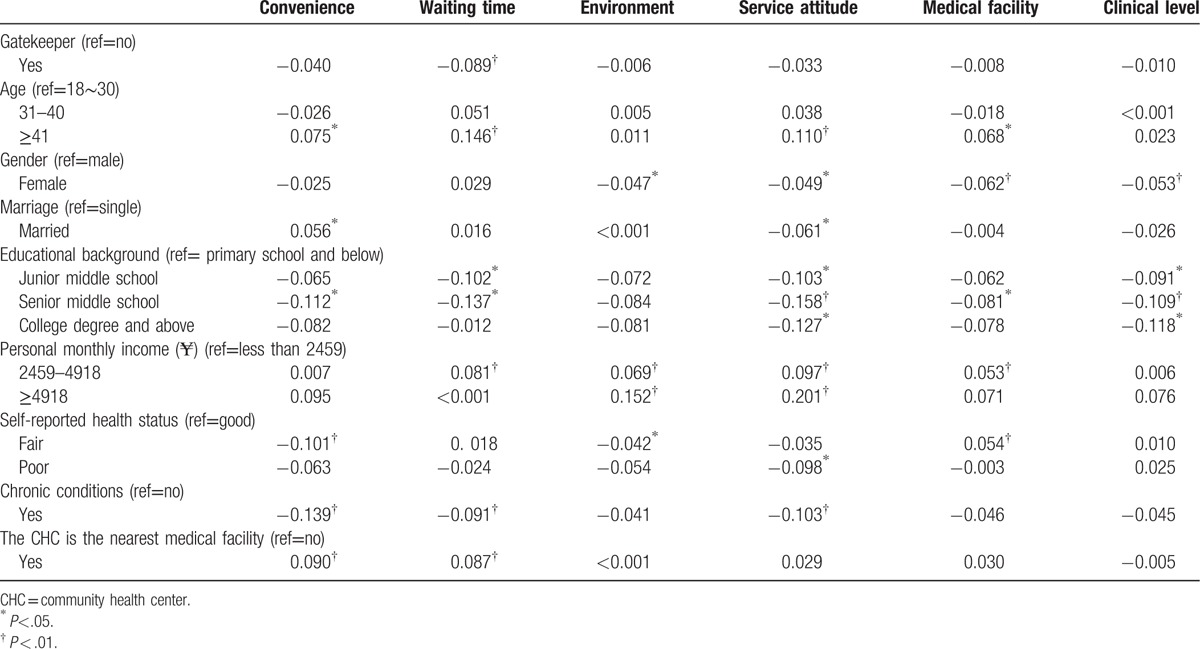

Results on the 6 measures of patient satisfaction with the care they received at the CHCs are presented in Table 5. When controlling for confounding factors, 5 of the 6 measures were not significantly associated with gatekeeper policy. However, patients with gatekeepers were less satisfied with waiting time at CHCs. Additionally, younger age, female, higher education, lower income, poorer health, with chronic conditions, and living farther away from CHCs were, in general, associated with lower satisfaction with their care at CHCs.

Table 5.

Multivariable analysis of factors associated with patient satisfaction with care at CHCs.

4. Discussion

Our bivariate and multivariable analyses suggested that the gatekeeper policy in Shenzhen, China, did have its intended effects. Compared with patients without gatekeeping restriction, patients with insurance policy who contacted CHCs first were more likely to choose CHCs first, visit more often regularly, and, equally satisfied with their care at CHCs. Overall, our findings were consistent with previous studies, which had shown that gatekeeping increased the use of primary care[27,29–31] and reduced the use of specialists and hospital care,[14,16,31–34] but without adverse impact on patient satisfaction and health outcomes[27,29,35–37].

Various policies similar to gatekeeper policy in Shenzhen have been implemented in many areas of China for the past decade. In Beijing, the elders and the unemployed who purchase the urban residents’ basic medical insurance are required to go to designated CHC for care and referral; in Nanjing, the gatekeeper policy applies to all residents who join in the urban residents’ basic medical insurance; and, in Zhuhai, each insured person must sign a contact with a CHC at the enrollment and agree to the gatekeeper policy; in the Changning District of Shanghai, similar network had also formed.[22–25,38] Mostly, the gatekeeper policy is embodied in the substantially reduced reimbursement rates for patients who seek care without referral from their designated CHCs.[39,40] In the published literature, much has been said about the significance and necessity of having gatekeepers in strengthening primary care and improving rational use of health resources,[41,42] but little has been reported on how gatekeeper policy affects the patients’ choice and use of community health services in China. Our study, although based on convenient sample and conducted in 1 city, suggests that gatekeeper policy may help strengthen primary care facilities, supporting broad implementation of gatekeeper policy in China.

This study has some limitations. First, to address our research questions, it could have been ideal to compare community health services between insured patients with gatekeepers and patients without gatekeepers, but such data are not available. As CHCs are usually cheaper than hospital care, self-pay patients may choose CHCs first for economic reasons. As a result, our estimates on the effect of gatekeepers may be under-estimated. However, the expected underestimation serves to strengthen our conclusion that gatekeeper policy has a positive effect in channeling patients to CHCs.

Second, our study was based on a convenient sample of patients who just completed their visits to CHCs. The fact that they were in the CHCs at the moment of the survey may already indicate their willingness to seek medical care in CHCs, which explains why over 90% of the patients in both the groups considered CHCs as their first choice. However, since both the groups of patients were compared in the same setting, and the analyses were done with controlling for confounders, we found that the differences between the 2 groups in choice and utilization of community health services should not be biased toward either group. Besides, we did not consider patients with other insurance among all surveyed patients without labor insurance when we conducted the survey, which may influence our results. However, our conclusion will not be changed because the proportion of other insured patients was low among all surveyed patients without labor insurance. Further study with such confounders should be conducted to assess the effect of gatekeeper policy more accurately.

Third, a number of confounding factors were adjusted in our study, however, there were still some other factors that were not included, such as wait-time, accessibility to higher-than-CHC hospitals, different severity and categorizes of diseases, psychological factors, which could also affect patient's choice. For instance, patients may choose CHCs for the longer wait time in higher-than-CHC hospitals. Besides, although we controlled for health status when analyzing the use of CHCs, some of the differences in the number of visits to CHCs in the past year may be due to the use of alternative, essentially primary care. For example, self-pay patients may use more private, traditional healers, which are usually cheaper, instead of going to CHCs. As a result, our findings may over-estimate the channeling effects of gatekeepers. Furthermore, patient satisfaction measures, defined as 5-point Likert scale and solicited as we did, may not be sensitive enough to detect the different levels of satisfaction. All these measurement issues are common to studies of this type, and should not substantially affect the overall research findings. Besides, more advanced model such as regularized logistic regression[43] may be more effective when too many factors in model, which should be tried to be used in the future research. Last but not the least, the results of the present study were limited because of the relatively young age of the subjects, and should therefore be interpreted with caution.

5. Conclusion

Patients in China, and the entire population, have the tendency to seek care from the best possible health care facilities regardless of how serious their medical conditions are. Efforts have been made to channel patients toward primary care institutions, with the hope that such a policy not only improves access to care, but also improves rational use of health resources and helps strengthen primary care institutions financially.

Our study indicates that, as repeatedly proven in other parts of the world, gatekeeper policy is effective in orienting patients toward community health facilities in China without substantially lowering patient satisfaction. Along with increased investments in rebuilding China's primary care network and expanding insurance coverage, implementation of gatekeeper policy, more specifically, making reimbursement conditional on CHC referral, can help alleviate the prevailing problem of “too difficult and too expensive to see a doctor” in China.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Abbreviations: CHC = community health center, CI = confidence interval, OR = odds ratio, SD = standard deviation, SE = standard error.

WL and YG contributed equally to this work.

This study was supported by Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC, 71373090, “Study on the gatekeeper policy of community health service”).

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Supplemental Digital Content is available for this article.

References

- [1].Zhou W, Dong Y, Lin X, et al. Community health service capacity in China: a survey in three municipalities. J Eval Clin Pract 2013;19:167–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Meng Q, Yuan J, Hou Z. Service and function ananlysis of grassroots health institutions in China. Health Policy Anal China 2009;2:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Wang X, Birch S, Zhu W, et al. Coordination of care in the Chinese health care systems: a gap analysis of service delivery from a provider perspective. BMC Health Serv Res 2016;16:571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Tang C, Luo Z, Fang P, et al. Do patients choose community health services for first treatment in China? Results from a community health survey in urban areas. J Community Health 2013;38:864–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Zhang X, Xiong Y, Ye J, et al. Analysis of government investment in primary healthcare institutions to promote equity during the three-year health reform program in China. BMC Health Serv Res 2013;13:114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Yip WC, Hsiao WC, Chen W, et al. Early appraisal of China's huge and complex health-care reforms. Lancet 2012;379:833–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Blumenthal D, Hsiao W. Lessons from the East—China's rapidly evolving health care system. N Engl J Med 2015;327:1281–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Liu H, Wang Q, Lu Z, et al. Reproductive health service use and social determinants among the floating population: a quantitative comparative study in Guangzhou City. BMC Health Serv Res 2014;14:502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Eggleston K, Ling L, Qingyue M, et al. Health service delivery in China: a literature review. Health Econ 2008;17:149–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Tang L. The influences of patient's trust in medical service and attitude towards health policy on patient's overall satisfaction with medical service and sub satisfaction in China. BMC Public Health 2011;11:472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Du J, Lu X, Wang Y, et al. Mutual referral: a survey of GPs in Beijing. Fam Pract 2012;29:441–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].McEvoy P, Richards D. Gatekeeping access to community mental health teams: a qualitative study. Int J Nurs Stud 2007;44:387–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Gervas J, Perez Fernandez M, Starfield BH. Primary care, financing and gatekeeping in western Europe. Fam Pract 1994;11:307–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Schwenkglenks M, Preiswerk G, Lehner R, et al. Economic efficiency of gate-keeping compared with fee for service plans: a Swiss example. J Epidemiol Community Health 2006;60:24–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Linden M, Gothe H, Ormel J. Pathways to care and psychological problems of general practice patients in a “gate keeper” and an “open access” health care system: a comparison of Germany and the Netherlands. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2003;38:690–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Martin DP, Diehr P, Price KF, et al. Effect of a gatekeeper plan on health services use and charges: a randomized trial. Am J Public Health 1989;79:1628–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Etter JF, Perneger TV. Health care expenditures after introduction of a gatekeeper and a global budget in a Swiss health insurance plan. J Epidemiol Community Health 1998;52:370–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Starfield B, Shi L, Macinko J. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Q 2005;83:457–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Khamis K, Njau B. Patients’ level of satisfaction on quality of health care at Mwananyamala hospital in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. BMC Health Serv Res 2014;14:400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Perneger TV, Etter JF, Rougemont A. Switching Swiss enrollees from indemnity health insurance to managed care: the effect on health status and stisfaction with care. Am J Public Health 1996;86:388–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Zhu M, Dib HH, Zhang X, et al. The influence of health insurance towards accessing essential medicines: the experience from Shenzhen labor health insurance. Health Policy 2008;88:371–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Ye T, Niehoff JU, Zhang Y, et al. Which medical institution should perform gatekeeping in rural china? results from a cross-sectional study. Gesundheitswesen 2017;79:e10–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Zhou LZ. The early experience of community-first option and two-way referral (in Chinese). Chongqing Med Sci 2010;39:2. [Google Scholar]

- [24].Ma JS. The first treatment in the community (in Chinese). Prevent Med Tribune 2010;16:3. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Dong YM, Du XP, Dong JQ. Feasibility of Implementing gatekeeping by family doctors in Yuetan district of Beijing (in Chinese). Chin Gen Pract 2009;12:3. [Google Scholar]

- [26].Zhang Z, Zhang XT. Promoting community first contact care by the force of system design (in Chinese). Chin Med Insurance 2012;1:53–4. [Google Scholar]

- [27].Gan Y, Li W, Cao S, et al. Patients’ willingness on community health centers as gatekeepers and associated factors in Shenzhen, China: a cross-sectional Study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95:e3261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Wu J, Zhang S, Chen H, et al. Patient satisfaction with community health service centers as gatekeepers and the influencing factors: a cross-sectional study in Shenzhen, China. PLoS One 2016;11:e0161683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Meyer TJ, Prochazka AV, Hannaford M, et al. Randomized controlled trial of residents as gatekeepers. Arch Intern Med 1996;156:2483–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Schillinger D, Bibbins-Domingo K, Vranizan K, et al. Effects of primary care coordination on public hospital patients. J Gen Intern Med 2000;15:329–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Olivarius ND, Jensen FI, Gannik D, et al. Self-referral and self-payment in Danish primary care. Health Policy 1994;28:15–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Ferris TG, Perrin JM, Manganello JA, et al. Switching to gatekeeping: changes in expenditures and utilization for children. Pediatrics 2001;108:283–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Etter JF, Perneger TV. Introducing managed care in Switzerland: impact on use of health services. Public Health 1997;111:417–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Hurley RE, Freund DA, Gage BJ. Gatekeeper effects on patterns of physician use. J Fam Pract 1991;32:167–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Hurley RE, Freund DA, Taylor DE. Emergency room use and primary care case management: evidence from four Medicaid demonstration programs. Am J Public Health 1989;79:843–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Paone G, Higgins RS, Spencer T, et al. Enrollment in the Health Alliance Plan HMO is not an independent risk factor for coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Circulation 1995;92(9 suppl): II69–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Rask KJ, Deaton C, Culler SD, et al. The effect of primary care gatekeepers on the management of patients with chest pain. Am J Manag Care 1999;5:1274–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Zheng T, Xie W, Xu L, et al. A machine learning-based framework to identify type 2 diabetes through electronic health records. Int J Med Inform 2017;97:120–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Lu D. A Research of Preliminary Diagnoses in Lin Yi Community (in Chinese). 2011;Jiaotong: Southwest Jiaotong University, 32–38. [Google Scholar]

- [40].Liu B, Ji EQ. The new and old system of “three steps” boosting community-first option (in Chinese). Social Security 2008;5:34–5. [Google Scholar]

- [41].Wang C, Zhang L. Analysis of the necessity and feasibility of first-treatment-in-community system (in Chinese). Health Econ Res 2009;8:2. [Google Scholar]

- [42].Liu B, Li XF. Thoughts on the first contact in Urban Community Health Services in China (in Chinese). Chin Gen Pract 2007;10:2. [Google Scholar]

- [43].Li W, Liu H, Yang P, et al. Supporting regularized logistic regression privately and efficiently. PLoS One 2016;11:e0156479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.