Abstract

We previously developed and characterized an adenoviral-based prostate cancer vaccine for simultaneous targeting of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) and prostate stem cell antigen (PSCA). We also demonstrated that immunization of mice with the bivalent vaccine (Ad5-PSA+PSCA) inhibited the growth of established prostate tumors. However, there are multiple challenges hindering the success of immunological therapies in the clinic. One of the prime concerns has been to overcome the immunological tolerance and maintenance of long-term effector T cells. In this study, we further characterized the use of the bivalent vaccine (Ad5- PSA+PSCA) in a transgenic mouse model expressing human PSA in the mouse prostate. We demonstrated the expression of PSA analyzed at the mRNA level (by RT-PCR) and protein level (by immunohistochemistry) in the prostate lobes harvested from the PSA-transgenic (PSA-Tg) mice. We established that the administration of the bivalent vaccine in surgifoam to the PSA-Tg mice induces strong PSA-specific effector CD8+ T cells as measured by IFN-γ secretion and in vitro cytotoxic T-cell assay. Furthermore, the use of surgifoam with Ad5-PSA+PSCA vaccine allows multiple boosting vaccinations with a significant increase in antigen-specific CD8+ T cells. These observations suggest that the formulation of the bivalent prostate cancer vaccine (Ad5-PSA+PSCA) with surgifoam bypasses the neutralizing antibody response, thus allowing multiple boosting. This formulation is also helpful for inducing an antigen-specific immune response in the presence of self-antigen, and maintains long-term effector CD8+ T cells.

Introduction

Prostate cancer remains a global health issue and is the leading cause of cancer-related deaths among men. While the treatment approaches for prostate cancer have evolved from surgery, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy to immunological therapies, a significant number of prostate cancer patients relapse with lethal metastatic disease, leading to an estimated 30,000 deaths annually in the United States alone [1]. Currently, immunotherapy represents one of the most promising approaches to treat cancer with an overall goal of educating the body’s own immune system to fight against cancer. Indeed, cancer immunotherapy is one of the priority areas of the cancer ‘moonshot program’ that aims to cure cancer.

An increased understanding of basic immunology, combined with the identification of various tumor-associated antigens, improved vaccine delivery vehicles, and the combination of vaccines with other agents to enhance antitumor response has fueled the development of novel immunological therapies for prostate cancer [2]. The personalized dendritic-cell-based prostate cancer vaccine (Sipuleucel-T) is the first FDA approved immunotherapy option for the treatment of metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) [3]. Prostvac-VF, currently in Phase III clinical trial, is another immunotherapy for prostate cancer, which has demonstrated an improvement in overall survival at early phase studies [4]. Increased attention is also being paid to adenoviruses as expression vectors where adenovirus serotype 5 (Ad5) has been the most extensively used for gene therapy and vaccine-based approaches [5]. In addition, active immunization against a murine colon cancer, breast cancer, and melanoma antigens have been induced by adenoviral vaccines [6]. A 10-year follow-up safety study supports the development of adenoviral-based therapy as a gene delivery vehicle [7, 8]. The Vaccine Research Center (VRC) at the National Institute of Health (NIAID) has developed vaccine candidates based on the Ad5 vector and has established the bio-distribution and toxicological safety of this vector, which suggests safety and suitability for investigational human use of Ad5-based vaccine candidates [9]. We have also developed and characterized the Ad5-vector-based vaccine (Ad5-PSA+PSCA) for the dual targeting of PSA and PSCA antigens with a potential for use in the clinic [10].

While the number of clinical trials for prostate cancer has increased in the past several years, no single immunotherapy approach has proven to be definitively superior to others in terms of clinical benefit [11, 12]. One of the challenges is that the targeted antigens unique to tumor cells but produced by normal cells. Because these are normal antigens, the absence of an in vivo immune response to such antigens is associated with peripheral tolerance in the form of anergy [13-15]. The development of an effective immunotherapy approach for the treatment of human cancer using cancer-associated antigens is dependent on the ability to overcome immune tolerance [16, 17]. In the present study, by using a transplantable mouse model for prostate cancer, we showed that the formulation of adenovirus-based prostate cancer vaccine (Ad5- PSA+PSCA) with surgifoam helps to circumvent immunological tolerance and induces antigen-specific effector CD8+ T cells in a transgenic mouse model.

Materials and Methods

Reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction

All the proposed mice studies were performed in accordance with guidelines and regulations approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. An established colony of PSA-Tg mice on Balb/c background (H-2d haplotype) was a kind gift from Dr. David Lubaroff, University of Iowa. These mice have PSA production confined to the prostate through the use of the probasin promoter. To characterize the expression of human PSA in the mouse prostate, total RNA (2 μg) from the PSA-Tg mouse prostate lobe (dorso-lateral) from mice of different ages was reverse transcribed using the SUPERSCRIPT II RNase H Reverse Transcriptase System. Samples were amplified by PCR in a total reaction volume of 50 μL, following a standard protocol for PCR amplification. Oligonucleotide primers for the PSA gene were synthesized based on the published sequence (Accession No. AF019770). The amplified PCR product was resolved electrophoretically on an agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide to verify the size of the amplified product.

Immunohistochemistry

Prostate tissues embedded in paraffin block were cut to a section of 4 μm and stained with monoclonal anti-human PSA antibody (Abcam, Inc.). Prostate tissue sections were deparaffinized and treated with citrate buffer. The tissue samples were washed with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and incubated with 2% bovine serum albumin for 30 minutes to block the non-specific antigen-antibody immunoreactivity. The tissue samples were incubated with 1:50 dilution of anti-PSA antibody overnight at 40°C. Next, the slides were treated with broad spectrum secondary antibody (Invitrogen) for 30 minutes, and HRP- conjugate (Invitrogen) was then added for another 30 minutes and developed with DAB according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Invitrogen). Finally, the slides were counterstained with hematoxylin, and the intensity of immunoreactivity was evaluated.

Vaccine and Vaccination

The development and characterization of Ad5-vector-based prostate cancer vaccines expressing human prostate-specific antigen (PSA) and prostate stem cell antigen (PSCA) have been described previously [10, 18]. Following dilution of the Ad5-vaccine in PBS, 30 mg of surgifoam (absorbable gelatin powder; also known as Gelfoam) was added in 1 mL of vaccine containing 109 pfu, and then 100 μL (108 pfu) of the suspension was used to immunize mice with a 25G5/8 needle. The PSA-Tg mice (6 to 8 weeks old) were immunized subcutaneously into the back flank using Ad5-PSA or Ad5-PSA+PSCA bivalent vaccine (108 pfu) mixed with surgifoam, and Ad5-LacZ served as a control. All the experiments were performed at least twice with 2 mice each and pooled for data presentation.

Measurement of antigen-specific CD8+ T-cell response

The antigen-specific CD8+ T cells secreting IFN-γ were enumerated using Enzyme Linked ImmunoSpot (ELISPOT) assay or intracellular cytokine staining (ICS). The functional activity of effector T cells against mouse prostate tumor cells expressing cognate antigen was measured using an in vitro cytotoxic T cell assay. The details of these methods analyzing effector T-cell immune responses have been described in our previous studies [10, 19]. Briefly, 2 weeks after immunization of the PSA-Tg mice, purified CD8+ T cells from the spleen were seeded at a density of 5×105 cells per well in 96-well plates previously coated with mouse anti-IFN-γ antibody and were stimulated with A4 cells (A20 cells expressing full-length human PSA). Following overnight incubation and subsequent washings with PBS, the plates were incubated with biotinylated mouse secondary antibody. Next, the plates were processed for staining using the AEC substrate kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Vector Laboratories), and the number of spot-forming cells was analyzed. For the ICS assay, 5×106 cells were plated in round-bottom 96-well plates. Following a 4-hour stimulation of splenocytes with A4 cells, the cells were processed for staining with Cy-5-conjugated anti-CD3, FITC-conjugated anti-CD8, and PE-conjugated IFN-γ antibodies (eBiosciences, CA, USA). The cells were fixed and permeabilized with Cytofix/Cytoperm Plus Kit (Pharmingen, CA, USA) and were analyzed with FlowJo 7.5 (Tree Star, CA, USA) software.

In vitro cytotoxic assay

In earlier studies, we have described the details of an in vitro cytotoxic assay [18, 19]. Briefly, PSA-specific lytic activity was measured using a standard chromium (51Cr) release assay. Splenocytes harvested from the PSA-Tg immunized mice were seeded at a density of 1×107 cells/well in the presence of interleukin-2 in 24-well plates and were stimulated with mitomycin C-treated A4 cells. Following a 5-day co-culture, the effectors were harvested and were incubated in graded numbers with radiolabeled target cells (RM11 cells expressing PSA). After a 4-hour incubation, 100 μL of the supernatant was removed from each well and counted in an auto-gamma counter to analyze the antigen-specific percentage lytic activity.

Tumor growth study

As described previously [10], 6 to 9-week-old PSA-Tg mice were inoculated subcutaneously with 2×105 viable RM11 tumor cells co-expressing cognate antigens prior to immunization. Tumor outgrowth as a function of time was measured twice a week and tumor volume was calculated. The experimental groups consisted of 5 mice each, and the experiment was repeated twice.

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed by Student’s t test using GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad Software, Inc., CA). The value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

PSA-Tg mouse model characterization

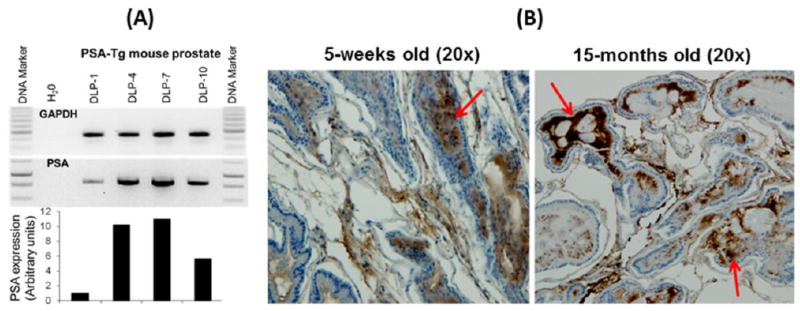

In this study, we determined the impact of an adenovirus-based bivalent vaccine using a transplantable mouse model (PSA-Tg) of prostate cancer. The PSA-Tg mice mimic the human condition with respect to secretion of and tolerance to PSA, as PSA secretion is confined to the prostate and is responsive to androgen through the use of the probasin promoter (prostate tissue-specific promoter). The choice of this PSA-Tg mouse enabled us to examine immunological responses in the presence of self-antigen (prostate-specific antigen: PSA) to which we developed the adenovirus-based vaccine expressing a combination of PSA and PSCA (Ad5-PSA+PSCA) antigens. Dorsolateral prostate (DLP) lobes were harvested from different age groups of PSA-Tg mice; the mRNA expression level of PSA was verified using PCR assay (Figure 1A), and PSA protein expression was validated using immunohistochemistry (Figure 1B). The overall intensity and the amount of PSA secretion seemed to be associated with increasing age (higher in 15-month-old mice), and the secretion of PSA was confined to the lumen. This observation suggests that PSA secretion in these PSA-Tg mice is under the control of hormonal regulation.

Figure 1.

Analysis of human prostate-specific antigen (PSA) in the dorsolateral prostate (DLP) of different age groups of PSA-Tg mice, (A) at the mRNA level, and (B) PSA protein level using IHC, where secretion of PSA is accumulated in the lumen and increases with the age. DLP-1, -4, -7, and -10 represents dorsolateral prostate harvested at different ages of PSA-Tg mice in weeks.

Analysis of effector T-cells response in presence of self-antigen

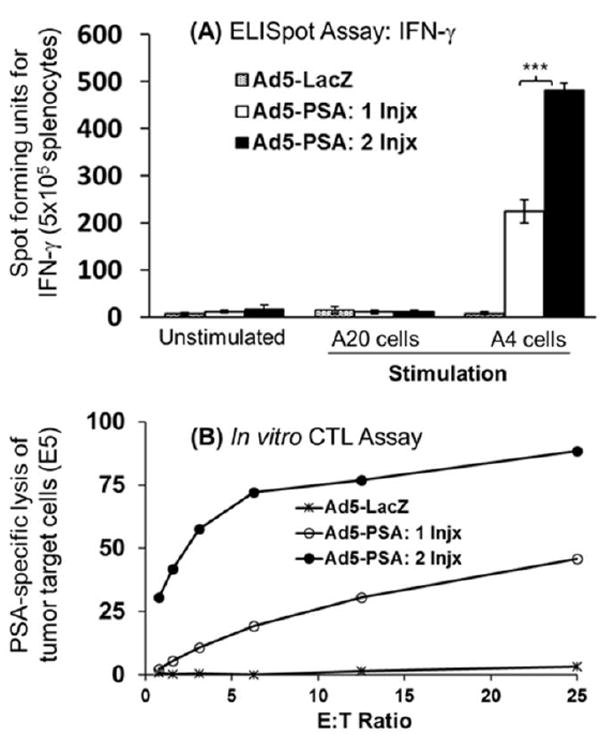

The ability of the Ad5-vector expressing prostate-specific antigens (Ad5-PSA or Ad5-PSA+PSCA) to induce antigen-specific T-cell immune responses against self-antigen was investigated. The PSA-Tg mice were immunized subcutaneously with the Ad5-PSA vaccine, either as an aqueous suspension or in the surgifoam. Mice that were vaccinated once with Ad5-PSA in aqueous solution (108 pfu) showed a very weak PSA-specific immune response (data not shown). However, vaccination of the PSA-Tg mice once with the Ad5-PSA vaccine (108 pfu) in surgifoam resulted in the induction of a strong response. The magnitude of the anti-PSA immune response was significantly enhanced following a second immunization, as illustrated by ELISpot assay for IFN-γ (Figure 2A) and an in vitro CTL assay using RM11/PSA tumor cells as the specific target (Figure 2B). These observations supported the effectiveness of the Ad5-based vaccine formulation with surgifoam for inducing functional immune effector T cells in PSA-Tg mice.

Figure 2.

(A) Measurement of IFN-γ secreting anti-PSA CD8+ T cells using ELISpot assay following injection of PSA-Tg mice (n = 4) with Ad5-vaccine in surgifoam, and (B) in vitro CTL assay to measure the effector function of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells. In this experiment, mice received 2 injections of vaccine mixed with surgifoam at 1 week apart and were sacrificed 14 days after the second immunization to harvest the splenocytes for analysis.

Analysis of long-term immune response following multiple vaccinations in PSA-Tg mice

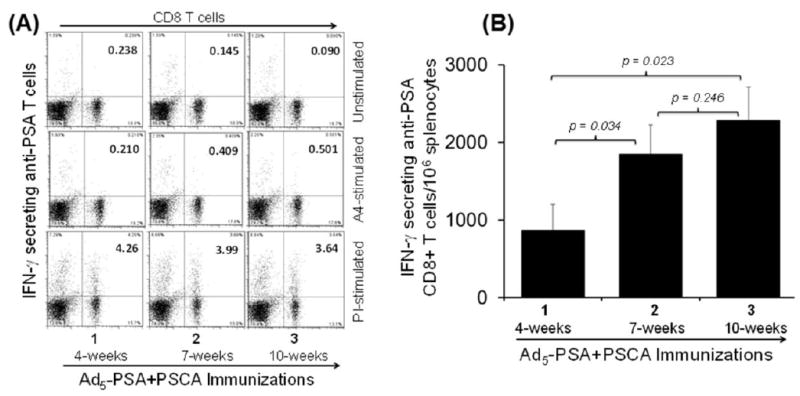

A major problem with adenovirus vaccines is that neutralizing antibodies severely limit the number of vaccinations. Therefore, to further determine whether the use of surgifoam would allow multiple boosting vaccinations, we immunized PSA-Tg mice twice or thrice with the Ad5-PSA+PSCA bivalent vaccine in formulation with surgifoam 3 weeks apart. To analyze the anti-PSA T-cell response using intracellular cytokine staining, mice were sacrificed to harvest the spleen 4 weeks after the third (Ad5-PSA+PSCA) immunization. We observed a significant increase in anti-PSA T cells between one vs two injections (P = 0.034), and one vs three injections (P = 0.023). There was an increase in anti-PSA CD8+ T cells after the third immunization, but this increase appeared non-significant (P = 0.246) compared to the second immunization (Figure 3). These observations indicated that the use of surgifoam with the bivalent vaccine was helpful in inducing long-term antigen-specific T-cell response in the presence of self-antigen, and bypassing the neutralizing antibody response.

Figure 3.

Development of long-term immune response in PSA-Tg mice (n = 4) measured for IFN-γ secreting anti-PSA CD8+ T-cells using ICS assay following multiple injections with the bivalent Ad5-PSA+PSCA vaccine in Surgifoam. (A) Representative dot plot from CD3-gated PSA-specific IFN-γ secreting CD8+ T cells; and (B) data pooled from 2 independent experiments depicting IFN-γ secreting antigen-specific CD8+ T cells. In this experiment, mice received 2 or 3 injections of vaccine mixed with surgifoam at 3 weeks apart, and were sacrificed 4 weeks after the third immunization to harvest the splenocytes. The numbers 1, 2, and 3 on the x-axis represents the number of immunizations at 4, 7, and 10 weeks respectively.

In vivo tumor growth study

To further characterize the mouse model, tumor-bearing PSA-Tg mice were vaccinated once, and the tumor outgrowth followed. In both groups (Ad5-LacZ control or Ad5-PSA+PSCA vaccine), PSA-Tg mice did not allow the establishment and growth of tumor cells expressing cognate antigens (Figure 4). Initially, these mice showed a minimal tumor outgrowth and then were tumor free (no measurable tumor outgrowth) by the end of 4 weeks. At any time point, there was no significant difference (7 days: P = 0.36; 10 days: P = 0.53; 14 days: P = 0.96; 17 days: P = 0.54; 21 days: P = 0.54; 24 days: P = 0.59) in tumor outgrowth between Ad5-LacZ (control) and Ad5-PSA+PSCA (vaccine) immunized mice. Long-term follow-up until day 75 did not reveal any sign of tumor growth recurrence; this suggested that the inoculated tumor cells expressing cognate antigen primed the PSA-Tg mice and induced anti-tumor immunity to clear the established tumors.

Figure 4.

Analysis of tumor outgrowth in PSA-Tg mice. Following subcutaneous injection of tumor cells on the back flank, tumor-bearing PSA-Tg mice were immunized once with Ad5-LacZ (control) or Ad5-PSA+PSCA vaccine. Tumor growth is expressed as mean ± standard error (n = 5). The experiment was repeated twice using 5 mice each. In the second set of experiments, the tumor regression time was shorter (~14 days) than presented in this figure (~28 days), although with similar results.

Discussion

The area of cancer immunotherapy is rapidly expanding with a goal to cure cancer. With such expansion, a number of investigators are dissecting the challenges facing immunological therapy to improve the immunization process and induce strong antitumor immunity. There is a long list of immunotherapy approaches approved or currently undergoing clinical testing for prostate cancer [11]. However, immunotherapy for prostate cancer primarily revolves around 3 fundamental approaches: GVAX, Sipuleucel-T, and Prostavac-VF, which have some limitations. Additional new approaches including the immune checkpoint inhibitor ipilimumab improved progression-free survival and PSA response compared with placebo, but failed to improve overall survival in a randomized phase III trial [20]. Ipilimumab also exposes patients to a risk of significant toxicity [21]. In addition, studies using anti-PD-1 are ongoing, and this checkpoint inhibitor has shown activity at early stages of clinical trials [22].

To advance immunotherapy for prostate cancer, we previously developed and characterized an adenovirus-based vaccine targeting dual antigens (PSA and PSCA) on prostate cancer cells. We also demonstrated that this bivalent vaccine (Ad5-PSA+PSCA) inhibited the growth of established prostate tumors in mice. Nonetheless, when using Ad5-vector-based vaccination there are 2 general concerns: 1) Adenovirus type5 is a common cold virus, and a high prevalence of pre-existing anti-Ad5 immunity in the human population may suppress the immunogenicity of Ad5-vaccine as well as limit the number of vaccinations in prostate cancer patients and 2) Because human antigens to the mouse are xenogeneic, we expect an induction of antigen-specific T-cell response in non-transgenic mice. Occasionally, clinical studies have reported that Ad5-based vaccination induced strong immune responses in patients despite pre-existing anti-adenovirus immunity [23]. To further address these questions, we characterized a mouse model expressing human PSA in the prostate, and demonstrated the development of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells with effector function in the presence of self-antigen following immunization with Ad5-vaccine with surgifoam. Our study provides evidence that the use of surgifoam allows 2 or more immunizations inducing strong antigen-specific T-cell response and is consistent with the previously published study in that the surgifoam formulation circumvents the preexisting adenovirus neutralizing antibody [24]. A Phase I clinical study using the first generation of adenovirus vaccines targeting PSA (Ad5-PSA) administered in surgifoam has induced antigenic immune response [25]. An early stage analysis of an ongoing Phase II study with Ad5-PSA vaccine, using 2 different protocols for patients with recurrent or hormone-refractory prostate cancer, showed the induction of anti-PSA T-cell responses in a high percentage of vaccinated patients. In addition, there was an increase in PSA doubling time in about 64% of the patients [26]. These studies provide supportive evidence for the potential use of a second generation Ad5-PSA+PSCA bivalent vaccine for prostate cancer in clinical testing.

Another obstacle to the success of immunotherapy approaches has been the immunological tolerance against the self-antigens, therefore limiting the effect of the antitumor response. Certain approaches of immunotherapy such as adoptive transfer of effector T cells, antitumor antibodies, or chimeric antigen receptor T cells bypass many of the mechanistic events associated with immunological tolerance [27]. Combination treatments including addition of adjuvants are being tested to overcome immune tolerance [13, 28]. When following an active immunization approach, the generation of potent antigen-specific effector T-cell response requires antigen-presenting cells (APCs) to process and present the targeted antigen, activation of co-stimulatory signals between the APC and T cells, and the environment to proliferate and maintain a long-term effector T-cell function. We previously demonstrated that the immunization of mice with the bone-marrow-derived dendritic cells infected with adenovirus expressing cognate antigen induces antigen-specific T cells and inhibits the growth of tumors [10]. Because the role of dendritic cells is central to augment immunotherapy, the use of a bivalent vaccine (Ad5-PSA+PSCA) may be promising in treating cancer or preventing tumor escape.

Formulation of the bivalent vaccine with surgifoam induces an antigen-specific immune response in PSA-Tg mice; however, the mechanistic role of surgifoam and its contribution to overcome immunological tolerance remains uncharacterized. Surgifoam is a porcine gelatin absorbable powder that provides a matrix for platelet adhesion and aggregation. It has been reported that the use of surgifoam induces a CD40-CD40L interaction to augment effector CD8+ T-cell function [29]. Activation of co-stimulatory molecules is important in the induction of the adaptive immune response, and it plays a significant role in the development of CD8+ T-cell memory response and cross-presentation of MHC-I restricted antigen [30-32]. It is likely that the surgifoam may serve as an adjuvant augmenting CD8+ T-cell response.

Conclusions

We demonstrated that the formulation of the bivalent vaccine (Ad5-PSA+PSCA) with surgifoam allows multiple boosting vaccinations bypassing the neutralizing antibody response. Although PSA-Tg mice failed to establish tumors at the given dose, the approach of immunization could be helpful in overcoming immunological tolerance and inducing long-term antigen-specific immune response in the presence of self-antigen. Additionally, enhanced therapeutic efficacy of the bivalent vaccine (Ad5-PSA+PSCA) inhibiting the growth of established prostate tumors in wild-type mice further supports the clinical potential of a second generation Ad5-PSA+PSCA bivalent vaccine with surgifoam formulation as a therapeutic vaccine for prostate cancer. These studies provide a strong rationale to test the bivalent vaccine Ad5-PSA+PSCA in combination with other therapies such as androgen deprivation therapy, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and checkpoint inhibitors in future clinical settings.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Karan is supported by National Institute of Health grant R01 CA204786.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The author declares no competing financial interests.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer Statistics, 2017. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2017;67:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Karan D, Holzbeierlein JM, Van Veldhuizen P, Thrasher JB. Cancer immunotherapy: a paradigm shift for prostate cancer treatment. Nat Rev Urol. 2012;9:376–85. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2012.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kantoff PW, Higano CS, Shore ND, Berger ER, Small EJ, Penson DF, et al. Sipuleucel-T immunotherapy for castration-resistant prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:411–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1001294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kantoff PW, Schuetz TJ, Blumenstein BA, Glode LM, Bilhartz DL, Wyand M, et al. Overall survival analysis of a phase II randomized controlled trial of a Poxviral-based PSA-targeted immunotherapy in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1099–105. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.0597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dubey S, Vanveldhuizen P, Karan D. Adenovirus-based immunotherapy for prostate cancer. Current Cancer Therapy Reviews. 2012;8:264–70. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tatsis N, Ertl HC. Adenoviruses as vaccine vectors. Mol Ther. 2004;10:616–29. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2004.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stratford-Perricaudet LD, Levrero M, Chasse JF, Perricaudet M, Briand P. Evaluation of the transfer and expression in mice of an enzyme-encoding gene using a human adenovirus vector. Hum Gene Ther. 1990;1:241–56. doi: 10.1089/hum.1990.1.3-241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Muona K, Makinen K, Hedman M, Manninen H, Yla-Herttuala S. 10-year safety follow-up in patients with local VEGF gene transfer to ischemic lower limb. Gene Ther. 2011 doi: 10.1038/gt.2011.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sheets RL, Stein J, Bailer RT, Koup RA, Andrews C, Nason M, et al. Biodistribution and toxicological safety of adenovirus type 5 and type 35 vectored vaccines against human immunodeficiency virus-1 (HIV-1), Ebola, or Marburg are similar despite differing adenovirus serotype vector, manufacturer’s construct, or gene inserts. J Immunotoxicol. 2008;5:315–35. doi: 10.1080/15376510802312464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karan D, Dubey S, Van Veldhuizen P, Holzbeierlein JM, Tawfik O, Thrasher JB. Dual antigen target-based immunotherapy for prostate cancer eliminates the growth of established tumors in mice. Immunotherapy. 2011;3:735–46. doi: 10.2217/imt.11.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rekoske BT, McNeel DG. Immunotherapy for prostate cancer: False promises or true hope? Cancer. 2016;122:3598–607. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim W, Fong L. Can Prostate Cancer Really Respond to Immunotherapy? Journal of clinical oncology. 2017;35:4–5. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.70.4791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Overwijk WW. Breaking tolerance in cancer immunotherapy: time to ACT. Curr Opin Immunol. 2005;17:187–94. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2005.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ostrand-Rosenberg S. Tolerance and immune suppression in the tumor microenvironment. Cell Immunol. 2016;299:23–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2015.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rolinski J, Hus I. Breaking immunotolerance of tumors: a new perspective for dendritic cell therapy. J Immunotoxicol. 2014;11:311–8. doi: 10.3109/1547691X.2013.865094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Desbois M, Champiat S, Chaput N. Breaking immune tolerance in cancer. B Cancer. 2015;102:34–52. doi: 10.1016/j.bulcan.2014.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zheng YW, Dou Y, Duan LL, Cong CS, Gao AQ, Lai QH, et al. Using chemo-drugs or irradiation to break immune tolerance and facilitate immunotherapy in solid cancer. Cellular Immunology. 2015;294:54–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2015.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lubaroff DM, Karan D, Andrews MP, Acosta A, Abouassaly C, Sharma M, et al. Decreased cytotoxic T cell activity generated by co-administration of PSA vaccine and CpG ODN is associated with increased tumor protection in a mouse model of prostate cancer. Vaccine. 2006;24:6155–62. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Karan D, Krieg AM, Lubaroff DM. Paradoxical enhancement of CD8 T cell-dependent anti-tumor protection despite reduced CD8 T cell responses with addition of a TLR9 agonist to a tumor vaccine. International journal of cancer Journal international du cancer. 2007;121:1520–8. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kwon ED, Drake CG, Scher HI, Fizazi K, Bossi A, van den Eertwegh AJ, et al. Ipilimumab versus placebo after radiotherapy in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer that had progressed after docetaxel chemotherapy (CA184-043): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial. The Lancet Oncology. 2014;15:700–12. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70189-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schadendorf D, Hodi FS, Robert C, Weber JS, Margolin K, Hamid O, et al. Pooled Analysis of Long-Term Survival Data From Phase II and Phase III Trials of Ipilimumab in Unresectable or Metastatic Melanoma. Journal of clinical oncology. 2015;33:1889–94. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.56.2736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Graff JN, Alumkal JJ, Drake CG, Thomas GV, Redmond WL, Farhad M, et al. Early evidence of anti-PD-1 activity in enzalutamide-resistant prostate cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7:52810–7. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.10547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Molnar-Kimber KL, Sterman DH, Chang M, Kang EH, ElBash M, Lanuti M, et al. Impact of preexisting and induced humoral and cellular immune responses in an adenovirus-based gene therapy phase I clinical trial for localized mesothelioma. Hum Gene Ther. 1998;9:2121–33. doi: 10.1089/hum.1998.9.14-2121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Siemens DR, Elzey BD, Lubaroff DM, Bohlken C, Jensen RJ, Swanson AK, et al. Cutting edge: restoration of the ability to generate CTL in mice immune to adenovirus by delivery of virus in a collagen-based matrix. Journal of immunology. 2001;166:731–5. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.2.731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lubaroff DM, Konety BR, Link B, Gerstbrein J, Madsen T, Shannon M, et al. Phase I clinical trial of an adenovirus/prostate-specific antigen vaccine for prostate cancer: safety and immunologic results. Clinical cancer research. 2009;15:7375–80. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lubaroff DM, Williams RD, Vaena D, Joudi F, Brown J, Smith M, et al. An ongoing Phase II trial of an adenovirus/PSA vaccine for prostate cancer. Cancer research. 2012;72 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Makkouk A, Weiner GJ. Cancer immunotherapy and breaking immune tolerance: new approaches to an old challenge. Cancer research. 2015;75:5–10. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-2538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Abe K, Ohira H, Kobayashi H, Saito H, Takahashi A, Rai T, et al. Breakthrough of immune self-tolerance to calreticulin induced by CpG-oligodeoxynucleotides as adjuvant. Fukushima J Med Sci. 2007;53:95–108. doi: 10.5387/fms.53.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Elzey BD, Schmidt NW, Crist SA, Kresowik TP, Harty JT, Nieswandt B, et al. Platelet-derived CD154 enables T-cell priming and protection against Listeria monocytogenes challenge. Blood. 2008;111:3684–91. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-05-091728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Borrow P, Tishon A, Lee S, Xu JC, Grewal IS, Oldstone MBA, et al. CD40L-deficient mice show deficits in antiviral immunity and have an impaired memory CD8(+) CTL response. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1996;183:2129–42. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.5.2129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bourgeois C, Rocha B, Tanchot C. A role for CD40 expression on CD8(+) T cells in the generation of CD8(+) T cell memory. Science. 2002;297:2060–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1072615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Trella E, Raafat N, Mengus C, Traunecker E, Governa V, Heidtmann S, et al. CD40 ligand-expressing recombinant vaccinia virus promotes the generation of CD8(+) central memory T cells. Eur J Immunol. 2016;46:420–31. doi: 10.1002/eji.201545554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]