Abstract

Copy number variations (CNVs) often include non-coding sequence and putative enhancers but how these rearrangements induce disease is poorly understood. Here we investigate CNVs involving the regulatory landscape of Indian hedgehog (IHH), causing multiple, highly localised phenotypes including craniosynostosis and synpolydactyly1,2. We show through transgenic reporter and genome editing studies in mice that Ihh is regulated by a constellation of at least 9 enhancers with individual tissue specificities in the digit anlagen, growth plates, skull sutures and fingertips. Consecutive deletions show that they function in an additive manner resulting in growth defects of the skull and long bones. Duplications, in contrast, cause not only dose-dependent upregulation but also misexpression of Ihh, leading to abnormal phalanges, fusion of sutures and syndactyly. Thus, precise spatio-temporal control of developmental gene expression is achieved by complex multipartite enhancer ensembles. Alterations in the composition of such clusters can result in gene misexpression and disease.

Work by the ENCODE consortium and others has helped to characterise a wide catalogue of regulatory elements, also referred to as enhancers, that control developmental gene expression in many species3–5. One of the most intriguing characteristics of these elements is their tendency to arrange in clusters, displaying redundancy in reporter assays and similarities in transcription factor occupancy6,7. Previous studies in Drosophila revealed that the observed redundancy may provide the system with robustness and spatio-temporal precision8–10. However, how the complex patterns of gene expression during development are achieved and why this involves elements with apparently redundant/overlapping function remains elusive. Copy number variations (CNVs) generally include non-coding regions of the genome and can thus interfere with the composition and dosage of regulatory elements, but the effects of such alterations are poorly understood.

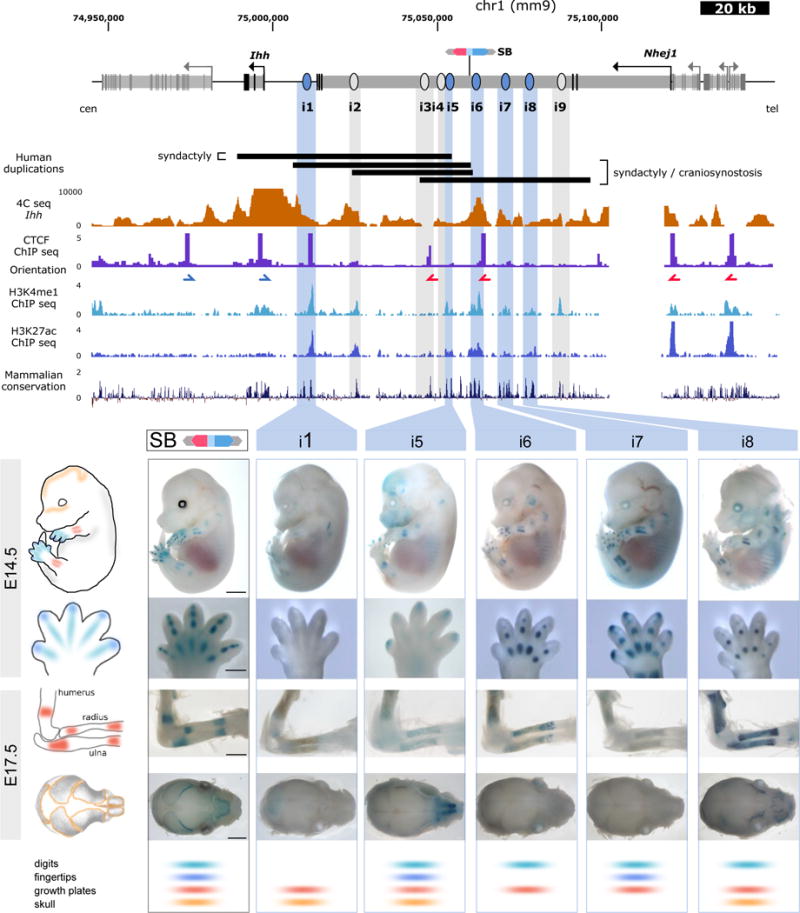

We investigated the effects of deletions and duplications upstream of Indian Hedgehog (IHH), a master gene of skeletal development involved in chondrocyte differentiation, joint formation and osteoblast differentiation. Accordingly, Ihh inactivation in mice results in extreme shortening of bones, joint fusions and almost absent ossification, ultimately causing early lethality11. Interestingly, patients carrying duplications at this locus display completely different phenotypes including craniosynostosis, syndactyly, and polydactyly1,2, indicating alternative pathomechanisms. To define the regulatory landscape of Ihh, we performed 4C-seq in E14.5 developing limbs and compared them to published datasets12. Our data show that the Ihh promoter interacts preferentially with the third intron of its upstream neighbouring gene, Nhej1 (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. 1), a genomic region affected in all reported disease-associated duplications. The region contains multiple sites positive for H3K4me1 and H3K27ac (indicative of active enhancers) and binding sites for CTCF, an architectural protein involved in facilitating enhancer-promoter contact by looping, The convergent CTCF motif orientation observed across the locus might facilitate the interactions measured in 4C-seq experiments (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. 2)13–16.

Figure 1. A cluster of enhancers interacts with the Ihh promoter during mouse development.

Above, close-up of the Ihh genomic region. Genes and their transcription start sites are indicated, exons are shown in black, introns in light grey. The position of the LacZ reporter insertion is indicated (SB). Black bars indicate the size and position of previously described human duplications1,2 converted to the mouse genome. 4C-seq performed in E14.5 limbs using the Ihh promoter as viewpoint is shown below. Note increased interactions with intron 3 of the adjacent Nhej1 gene (see also Supplementary Fig. 1). CTCF ChIP-seq performed in E14.5 limbs is shown (ENCODE)3 and blue/red arrows indicate motif orientation. Additional tracks below show H3K4me1, H3K27ac, as well as conservation. This information was used to predict enhancers i1–i9, indicated by light blue and gray bars. Below, transgenic reporter assay (LacZ) of elements positive at E14.5 and E17.5 (marked in light blue; panel displays embryos and handplates at E14.5 and dorsal view of forelimbs and top view of skulls at E17.5). Regulatory activity of the region as indicated by the inserted LacZ reporter (SB, black outline) is shown on left. Lower panel shows scoring of each element for tissue-specificity. Elements negative at E14.5 but with positive staining at E17.5 are marked in gray and shown in Supplementary Fig. 3. Scale=2000μm (embryos/skulls), 500μm (handplates) and 1000μm (forelimbs).

The insertion of a LacZ reporter cassette (sleeping beauty)17 to capture the regulatory capacity of the region revealed a pattern consistent with Ihh expression, i.e. condensing digits, growth plates, fingertips and skull sutures. Using a combination of H3K27ac and H3K4me1 ChIP-seq of E14.5 limbs18, conservation19, and our 4C-seq interaction profiles, we defined 9 regions with enhancer potential and validated them in mouse transgenic enhancer activity assays20 (Fig. 1a). Embryos were analyzed at two time points, E14.5 and E17.5, to capture Ihh expression domains during digit development (fingertips and cartilage anlagen) and bone growth (skull sutures and growth plates), respectively. 5 of the tested elements showed activity at both stages (Fig. 1b), whereas 4 additional elements were active only at E17.5 (Supplementary Fig. 3). We scored the activity of each element in the previously identified regions (Fig. 1b, Supplementary Fig. 3 and Table 1). This revealed the inherent complexity of this cluster, where almost every individual element displayed a unique pattern of activity. All elements gave a positive signal in growth plates, whereas other domains, like fingertips, were covered only by a small subset of enhancers (i5 and i7). This suggests that the enhancers in this cluster act in a modular fashion and that the degree of overlapping activity varies between tissues and developmental time points.

To evaluate the functionality of these elements, we deleted intron 3 of Nhej1 (Fig. 2), which contains 8 of the 9 identified enhancers, using CRISVar21. Nhej1 encodes a DNA repair protein essential for the nonhomologous end-joining pathway, required for double-strand break repair. In humans, homozygous mutations in NHEJ1 result in severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) with microcephaly, growth retardation, and sensitivity to ionizing radiation, reflecting a deficiency in DNA-repair (OMIM #611291)22. In contrast, Nhej1 knockout mice are viable and do not display any morphological phenotype23,24. μCT scans of Nhej1−/− skulls revealed no abnormalities indicating that Nhej1 has no major role in skull and suture development (Supplementary Fig. 4). Mice homozygous for the Nhej1 intronic deletion [Del(2–9)] displayed very short limbs, absent cortical bone, fused joints, as well as reduced skull ossification, very similar to those observed upon Ihh inactivation11. While Nhej1 transcription levels remained basically unchanged (Supplementary Fig. 5), we observed a drastic reduction of Ihh mRNA expression in E13.5 limbs and E17.5 skulls (98% and 99%, respectively), consistent with the observed phenotype. Therefore, this region contains most of the regulatory elements required for Ihh skeletal expression.

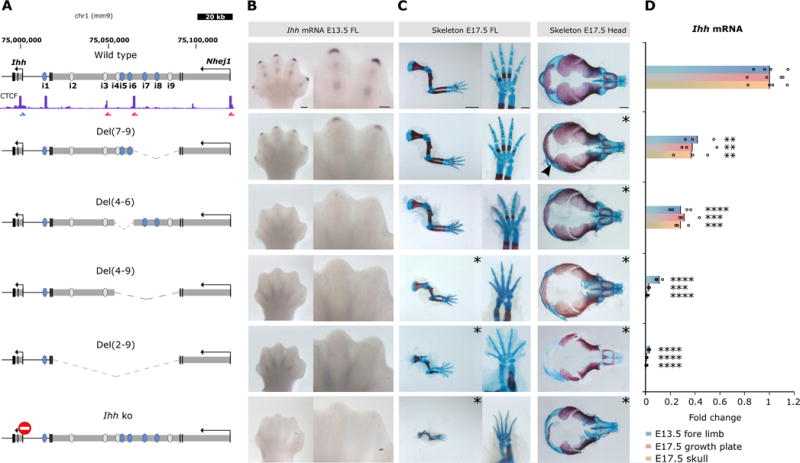

Figure 2. Deletions of regulatory elements reveal additive control of Ihh expression.

(A) Deletions generated by CRISVar21 at the locus. Ihh knockout is shown for comparison (stop signal). CTCF ChIP-seq performed in E14.5 limbs is shown (ENCODE)3 and blue/red arrows indicate motif orientation. Deleted chromosomal region is represented as dotted line. Note that Del (4–9) and Del(7–9) delete only 1 intronic CTCF site, maintaining another intact. (B) In situ hybridization shows Ihh expression in handplates (E13.5). Note expression in digit tips and condensing digits in wt and loss of expression in all deletions containing enhancer i5. Scale bar=200 μm (handplates). (C) Skeletal stainings of forelimbs, autopod and skull (E17.5). Mutants displaying abnormal phenotypes are indicated by asterisks. Both, Del(2–9) and Del(4–9) result in massive reduction of limb size and reduced ossification similar to Ihh ko, whereas Del(4–6) and Del(7–9) mice did not show noticeable limb abnormalities. All studied mutants displayed skull defects (delayed ossification), an effect less prominent in Del(7–9) mutants (arrowhead). Scale bars=2000μm (forelimbs), 500μm (autopods) and 1000μm (skulls). (D) Ihh qPCR analysis in E13.5 forelimb, E17.5 growth plate (elbow) and skull. Deletion of intron 3 of Nhej1 encompassing enhancers i2–i9 resulted in almost complete loss of Ihh expression in all tissues, whereas smaller deletions reduce expression partially. Bars represent mean of n ≥ 3 different individuals (circles). *P< 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001; ns, not significant.

Next, we generated a series of specific deletions to assess the functional redundancy within this enhancer cluster (Fig. 2). A homozygous deletion of the enhancers located in the telomeric part of the intron [Del(4–9)] resulted in a lethal growth defect almost as severe as the deletion of the entire intron confirming that the most relevant enhancers are located in the telomeric region. Deletion of only the three central enhancers [Del(4–6)] reduced Ihh expression by approx. 70% in all tested tissues, whereas the deletion of the three more telomeric enhancers [Del(7–9)] resulted in a 60% reduction (Fig. 2). Both mutants were viable and phenotypically normal, but showed a delay in skull ossification (Fig. 2) and a 10% reduction in bone length (Supplementary Fig. 6). All deletions except Del(7–9) resulted in a loss of fingertip expression, indicating that element i5 acts as a major regulator for this region. These results demonstrate that Ihh expression is controlled by a cluster of redundant enhancers, which appear to act in an additive manner.

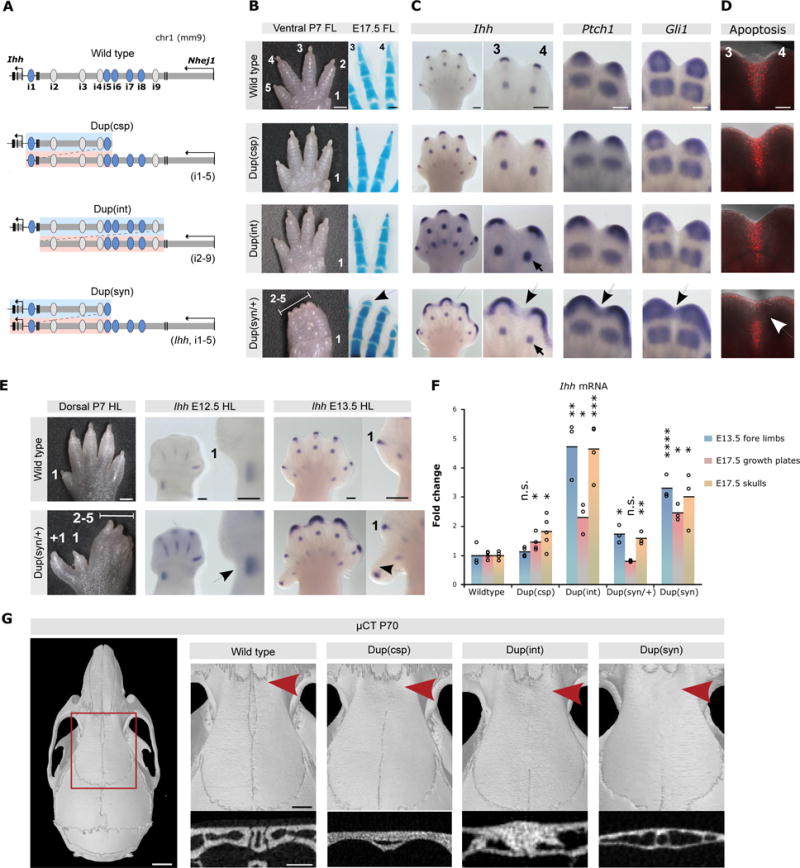

To understand the mechanisms underlying pathogenic duplications at the IHH locus, we duplicated the entire Nhej1 intron, equivalent to Del(2–9)]. In addition, we re-engineered two of the previously described human duplications: Dup(csp) encompassing the region between enhancers i1–5 (re-engineered human duplication causing craniosynostosis Philadelphia type1,2); and Dup(syn) which includes Ihh and the upstream region up to enhancer i5 (re-engineered human duplication causing syndactyly Lueken type2) (Fig. 3a). Dup(int) and Dup(csp) mutants did not show gross morphological alterations. In contrast, Dup(syn)/+ mice showed a complete cutaneous syndactyly of digits 2/5 in fore- and hindlimbs (Fig. 3b), thus recapitulating the human phenotype.

Figure 3. Duplications of enhancer elements result in Ihh over- and misexpression.

(A) Duplications generated by CRISVar21. Duplicated fragment shown in blue/pink. (B) Forelimb morphology (P7). Dup(int) and Dup(csp) mice (homozygous) are normal, but Dup(syn)/+ display 2/5 syndactyly. Skeletal stainings (right) show short and broad terminal phalanges in Dup(syn)/+ mice (arrow). Scale bars=1000μm (P7), 200μm (E17.5 handplates). (C) In situ hybridization shows increased and broadened expression of Ihh and downstream effectors Ptch1 and Gli1 [Dup(csp) < Dup(int) < Dup(syn)]. Expression domains in Dup(syn)/+ mice extend into distal interdigital space (arrows). Note increased Ihh expression in digit condensations in Dup(int) compared to Dup(syn)/+ (small arrow), also observed across entire handplate. Scale bars=200μm. (D) Apoptosis in interdigital space (red signal). Note lack of signal in distal region in Dup(syn)/+ mutants (arrow). Scale bars=200μm. (E) Hindlimb morphology of Dup(syn)/+ mice. Note preaxial polydactyly and syndactyly 2/5. In situ hybridization shows increased Ihh expression (arrows) in preaxial region (insets). Scale bars=1000μm (P7), 200μm (E12.5/E13.5). (F) Ihh qPCR analysis. Duplications increase Ihh expression. High levels in Dup(csp) forelimbs (no phenotype) result from digit condensations, while moderate upregulation in Dup(syn)/+ (syndactyly) derives from fingertips. Bars represent mean of n ≥ 3 different individuals (circles). *P< 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ns, not significant. (G) μCT skull analysis (P70). Red square indicates enlargement of metopic suture region (right). Below, cross section of metopic sutures (red arrow). All mutants display complete suture fusion [maximum effect in Dup(int)]. Scale bars=2mm (skull), 1mm (enlargement), 0.5μm (cross section).

Skeletal stainings revealed that the syndactyly of Dup(syn) mutants did not involve bony fusions. Digits and joints developed normally, but terminal phalanges were broad and short. In situ hybridization experiments in E13.5 limbs revealed major changes in fingertips, where Ihh expression was not only increased but also broadened. These effects were weak in Dup(csp), more pronounced in Dup(int) and most prominent in Dup(syn)/+ mice, in which Ihh expression extended into the distal interdigital space (Fig. 3c). Accordingly, the expression domains of the hedgehog downstream targets Gli1 and Ptch1 were broadened and a fusion between the normally separated domains was observed which was most pronounced in Dup(syn)/+ mutants. Except for Bmp4 and Nog, we did not observe abnormalities in other genes/pathways involved in syndactyly/interdigital cell death (Supplementary Fig. 7) suggesting that hedgehog signalling alone is sufficient to induce this type of syndactyly. Next, we quantified interdigital apoptosis, which is required for digit separation25. Consistent with the observed phenotype we observed a strong signal in the interdigital space in wt, Dup(csp) and Dup(int) embryos, but an absence of signal in the distal region in Dup(syn)/+ mice (Fig. 3d). Thus, upregulation and misexpression of Ihh in fingertips beyond a certain threshold resulted in abnormalities of the distal phalanges, most likely by interfering with the phalanx-forming region26, and syndactyly due to suppression of interdigital apoptosis.

In addition, Dup(syn) mutants displayed preaxial polydactyly on hindlimbs (50% penetrance, Fig. 3e). One major cause of polydactyly is ectopic activation of hedgehog signalling at the anterior developing limb bud27,28. Interestingly, Dup(syn)/+ mice showed a prominent increase of Ihh expression in the distal zeugopod during hindlimb development starting at E12.5 (negative at E10.5/E11.5). As Ihh is a potent diffusible morphogen, we hypothesise that the increased expression might interfere with the anterior-posterior Hedgehog gradient. The observed phenotype is thus the result of a loss of precision in spatio-temporal expression levels indicating that, similar to the syndactyly, an increase in enhancer dosage can have site-specific effects.

Expression profiling by qPCR was used to quantify the effect of the duplications on gene expression (Fig. 3f). Whereas Nhej1 and other nearby genes showed no alteration (Supplementary Fig. 5), all analysed mutants displayed increased Ihh expression in skull and limbs, with the highest expression levels observed in Dup(int) (up to 5-fold upregulation). In situ hybridization of Dup(int) forelimb autopods (Fig. 3c) showed increased expression mainly in digits, whereas in Dup(syn) mutants the expression increase was most prominent in fingertips, consistent with the observed syndactyly. To investigate the effect of increased Ihh expression on skull development and suture formation a detailed μCT analysis was performed (Fig. 3g). This revealed a fusion of the metopic suture (craniosynostosis) in all mutants, but most pronounced in Dup(int) mice. The phenotypes observed in our mouse mutants (i.e. syndactyly, polydactyly, craniosynostosis) accurately recapitulate previous observations in human patients1,2 (Supplementary Fig. 8). Thus, the induced changes in changes in enhancer composition and dosage resulted in a disturbance of level and precision of gene expression thereby causing abnormal development and disease. Interestingly, the observed phenotypes did not always correlate with the number of duplicated elements but appeared to be influenced by other factors such as the position of the duplication and the arrangement of individual elements relative to the cluster.

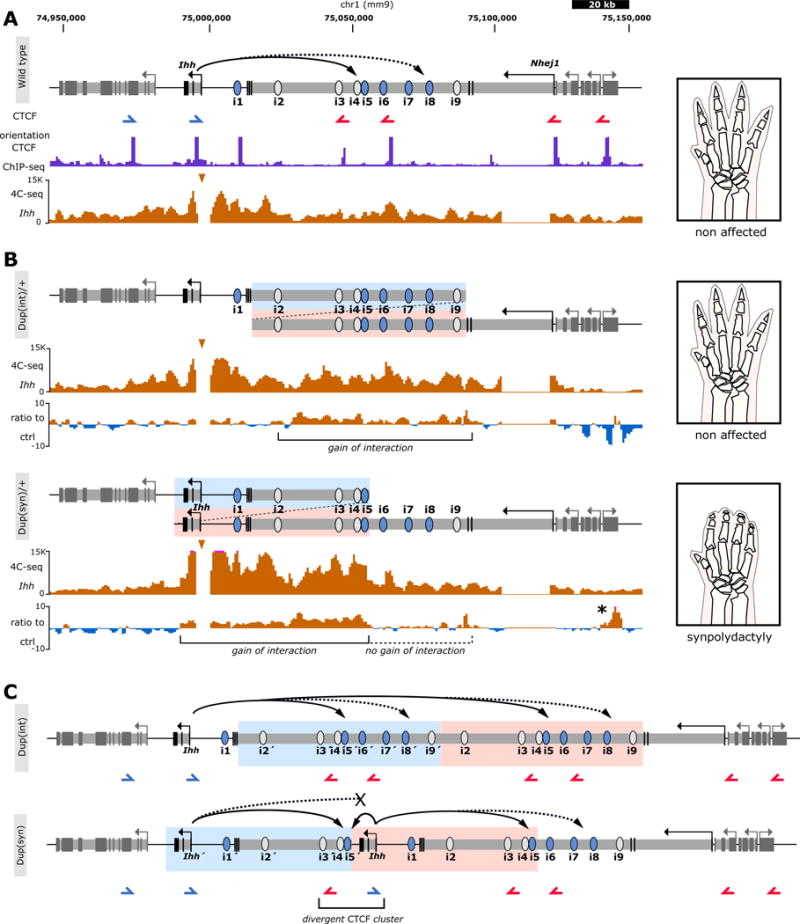

To investigate a possible effect of the spatial configuration on the duplicated alleles, we performed 4C-seq experiments in E14.5 limbs (viewpoint=Ihh; Fig. 4a). In Dup(int)/+ mutants (i2–9 enhancer duplication) we observed increased interactions across the entire duplicated region. In contrast, Dup(syn)/+ mutants (Ihh and i1–5 enhancer duplication) only showed increased contact with the centromeric region of the enhancer cluster, suggesting that the centromeric Ihh copy created an own regulatory domain containing only the duplicated regulatory elements i1–5 (Fig. 4b). The presence of a divergently oriented CTCF pair near the telomeric Ihh promoter might explain this domain separation by limiting chromatin interaction beyond this site. Moreover, the larger contact areas in Dup(int)/+ mutants correlate with the observed levels of Ihh upregulation compared to Dup(syn)/+. As illustrated in Fig. 4c, the syndactyly in Dup(syn)/+ mice is likely due to two types of interactions of the major fingertip enhancer i5 with the two copies of Ihh, one via long range, the other by placing the i5 enhancer in direct proximity to Ihh. Together, this results in a localized upregulation of Ihh expression in the fingertips. An increased expression mediated by the disconnection from a repressor element is unlikely, as none of the studied deletions resulted in any observable upregulation of Ihh. To further evaluate whether the observed limb phenotypes in the Ihh containing duplication [Dup(syn)] was merely a gene dosage effect, we crossed Dup(syn)/+ mice with Ihh−/+ mice and with mice lacking the enhancer cluster [Del(2–9)]. In both cases, double heterozygous mice displayed the same syndactyly and polydactyly as observed in Dup(syn)/+ mice (Supplementary Fig. 9) indicating that the misexpression was due to the specific, partially duplicated regulatory landscape.

Figure 4. 4C-seq reveals specific regulatory configurations in duplications.

(A) Schematic of wt locus. Continuous arrow indicates interaction between Ihh and enhancers i4–6, while discontinuous arrows indicate interaction of Ihh with i7–9. Below, CTCF ChIP-seq (E14.5 limbs, ENCODE)3. Blue/red arrows indicate motif orientation. 4C-seq (viewpoint=Ihh promoter) shows interaction profile in E14.5 handplates. A schematic of limb morphology is shown on right panel. (B) Duplication of intron 3 of Nhej1 [Dup(int)] and re-engineered human duplication causing syndactyly [Dup(syn)] below. Duplicated regions are indicated by blue/pink. 4C-seq profile (viewpoint=Ihh promoter) and ratio to wt control are shown for each duplication. Brackets indicate regions with gain of interaction. Note no gain of interaction with the region containing enhancers i6–i9 (black dashed bracket) in Dup(syn)/+, indicating that the duplicated Ihh copy does not interact with this region. Observed phenotypes are schematically shown on right panel. Asterisk indicates increased interactions with Cnppd1 and Fam134a genes, which does not have functional consequences (see Supplementary Fig. 5). (C) Model of regulatory interactions of duplicated alleles. In Dup(int), Ihh can interact with the entire duplicated landscape, including two copies of the main digit enhancer (i5). In Dup(syn), both Ihh copies interact with a downstream copy of the i5 enhancer (large continuous arrows) but only the telomeric Ihh copy has access to i7–9 (discontinuous arrows) due to the presence of the divergent CTCF cluster (bracket). Additionally, the duplicated i5 enhancer interacts with the telomeric Ihh copy due to genomic proximity (short continuous arrow). Duplicated regions are indicated in blue/pink.

Our study shows that a multipartite enhancer ensemble regulates Ihh expression in fingertips, digit condensations, growth plates and skull sutures. The described functional redundancy appears to be a common phenomenon of these types of enhancers, as recently shown for the alpha-globin or the Wap super-enhancers29,30. At the Ihh locus, we observed a complex scenario as not all enhancers display the same combination of expression domains, a phenomenon also described for the HoxD cluster and Fgf831,32. This modular nature and, in particular, the correct dosage appears critical to confer the required precision of gene expression. This is supported by our finding that an increase in enhancer number resulted in an increase in gene expression. However, this effect was site-specific and dependent not only on the enhancer number but also on their position. CNVs, and in particular duplications, may affect this delicate balance, thereby causing over- and/or misexpression resulting in disease. The reported duplications do not interfere with topologically associating domain (TAD) boundaries, as reported at the Epha4 and Sox9 loci33,34, thus highlighting alternative mechanisms that should be considered when interpreting genomic duplications. Our study highlights the importance of analysing regulatory elements in the complex setting of their native genomic environment since reductionist approaches relying on reporter assays and deletions of individual enhancers insufficiently capture the multifaceted redundant and complementary functions of enhancer clusters.

ONLINE METHODS

No statistical methods were used to predetermine sample size. All experiments and analyses were performed using samples from at least 3 different animals and repeated at least 2 times in the laboratory. Samples/animals were included/excluded according to genotype by PCR. Experiments were not randomized, and investigators were not blinded to allocation during experiments and outcome assessment.

ES cell targeting and transgenic mouse strains

Embryonic stem (ES) cell culture was performed as described previously21. ES and feeder cells were tested for mycoplasma contamination using Mycoalert detection kit (Lonza) and Mycoalert assay control set (Lonza).

Duplications and deletions were generated in G4 ES cells (129/Sv × C57BL/6 F1 hybrid) using CRISVar as described previously21. Target regions, sizes and guide sequences are listed in Supplementary Table 2. Embryos and live animals from ES cells were generated by diploid or tetraploid complementation35. Genotyping was performed by PCR analysis.

A Sleeping Beauty (SB) cassette17 was inserted in G4 ES cells at the center of the third intron of the Nhej1 gene (chr1:75,060,87; mm9), by homologous recombination using standard protocols36. The SB transgene carries a single a LacZ reporter gene with a minimal human β-globin promoter and a Neomycin resistance cassette, flanked by transposable elements. Coordinates and primer sequences for amplifying homology sequences are provided in Supplementary Table 3. Positive ES cell clones were injected into donor blastocysts to generate chimaeras. Neomycin cassette was removed by crossing chimaeric animals with a Flpe-deleter line. Genotyping was performed by PCR analysis.

Mouse strains were maintained by crossing them with C57BL6/J mice. All animal procedures were conducted as approved by the local authorities (LAGeSo Berlin) under the license numbers G0368/08 and G0247/13.

In vivo enhancer validation

Putative enhancer regions were amplified by PCR from mouse genomic DNA and cloned into a Hsp68-promoter-LacZ reporter vector as previously described20 (see Supplementary Table 4). Transgenic embryos were generated and tested for LacZ reporter activity at E14.5 and E17.5. All animal work performed at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory was reviewed and approved by the institutional Animal Welfare and Research Committee (AWRC). Sample sizes were selected empirically based on our previous experience of performing transgenic mouse assays for >2,000 total putative enhancers. A summary of all transgenic mice can be found in Supplementary Table 1. As all transgenic mice were treated with identical experimental conditions, and as there were no groups of animals directly compared in this section of the study, randomization and experimenter blinding were unnecessary and not performed.

Quantitative Real-Time PCR

Handplates (E13.5), fore- and hindlimb growth plates (E17.5) and cranium (E17.5) were dissected from wild type and mutant embryos (n≥3) in ice cold PBS/DEPC and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen. RNA isolation was performed using RNAeasy Kit (Qiagen), and cDNA was transcribed using TaqMan Reverse Transcription Kit (Roche) according to the specification of the manufacturer. qPCR was performed using SYBRGreen (Qiagen) in a ABIPrism HT 7900 Real-time Cycler. GAPDH was used as an internal control, and fold changes were calculated by relative quantification (2−ΔΔCt). Primers are summarized in Supplementary Table 5.

4C-seq

4C-seq libraries were generated from microdissected E14.5 mouse forelimb tissue (digit 2–5) as described previously37. The starting material for all 4C-seq libraries was 5×106–1×107 cells. All 4C-seq experiments were carried out in heterozygous animals and compared to wildtype controls. 4-bp cutters were used as primary (Csp6I) and secondary (BfaI) restriction enzymes. A total of 1 to 1.6 μg DNA was amplified by PCR (primer sequence in Supplementary Table 6). All samples were sequenced with Illumina Hi-Seq technology according to standard protocols. 4C-seq experiments were carried out in two biological replicates in wild type, Dup(int) and Dup(syn)/+ mutants. A representative result is shown in the Figure 4.

For 4C-seq data analysis, reads were pre-processed, mapped to a corresponding reference (mm9) using BWA-MEM38 and coverage normalized as reported previously34. The viewpoint and adjacent fragments 1.5 kb up and downstream were removed and a window of 2 fragments was chosen to normalize the data per million mapped reads (RPM). To compare interaction profiles of different samples, we obtained the log2 fold change for each window of normalized reads. To obtain ratios duplicated regions were excluded for calculation of the scaling parameter used in RPM normalization. Code is available upon request.

CTCF motif orientation analysis

Orientation of the motifs within conserved CTCF peaks was obtained using FIMO (see URLs) with standard parameters39. CTCF motif40 was obtained from JASPAR database (see URLs).

Phenotypic analysis

Phenotypic analysis for mutant mouse lines was carried out for at least three animals per analysis and developmental stage (E17.5, P7 and P70), in homo- and heterozygous animals. Penetrance of phenotypes was determined by analyzing n>20 animals and considered fully penetrant if all mutants were similarly affected.

Micro-computer tomography (μCT)

Skulls and autopods of control and mutant mice (n > 3) were scanned using a Skyscan 1172 X-ray microtomography system (Brucker microCT, Belgium) at 10μm resolution. 3D model reconstruction and length measurements were performed with the Skyscan image analysis software CT-Analyser and CT-volume (Brucker microCT, Belgium). Cross-sections were performed at 10μm resolution. Relative length was determined relative to wildtype controls.

Whole-mount in situ hybridization and skeletal preparations

Whole-mount in situ hybridization was performed in wild type and mutant E13.5 embryos (n=4) according to standard procedures. All probes were generated by PCR amplification using mouse limb bud cDNA. For skeletal preparations, wildtype and mutant E17.5 embryos (n=4) were stained with Alcian Blue/Alizarin red according to standard protocols.

LacZ-staining

E14.5 and E17.5 mouse embryos (n > 5) were dissected in cold PBS, fixed in 4% PFA/PBS on ice for 30 min, washed twice with ice cold PBS and once at room temperature (19–24°C), and then stained overnight for β-galactosidase activity in a humid chamber at 37°C as previously described17. After staining, embryos were washed in PBS and stored at 4°C in 4% PFA/PBS.

Statistical analyses

Results are presented as the mean ± s.d. of at least 3 independent biological replicates (n≥3). Statistical differences between the means were examined by two-sided Student’s t-test. *P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Prespecified effect size was not defined.

DATA AVAILABILITY AND ACCESSION CODE AVAILABILITY STATEMENTS

Data availability

Gene Expression Omnibus

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?token=sjsdyygmxtinvwl&acc=GSE95062

Code availability

Custom computer codes used to generate results reported in the manuscript will be made available upon request.

URLs

FIMO, http://meme-suite.org/tools/fimoJASPAR database, http://jaspar.binf.ku.dk/

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft to SM and EK. SM was supported by the European Community’s Seventh Framework Programme, grant agreement no. 602300 (SYBIL). MO was supported by a Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF) fellowship. AV was supported by National Institutes of Health grants R01HG003988, U54HG006997, U01DE024427 and U01DE024427. We thank the sequencing core, transgenic unit and animal facilities of the Max Planck Institute for Molecular Genetics for technical assistance.

Footnotes

CONTRIBUTIONS

A.J.W., D.G.L. and S.M. conceived the study and designed the experiments. M.O. and A.V. performed LacZ experiments and analysis of individual enhancers, A.J.W. of the Sleeping Beauty insertion. A.J.W. and L.W. generated transgenic mouse models. W.-L.C., J.P.dV. and G.C. contributed to histological analysis. A.J.W., N.B. and G.C. performed qPCR, in situ hybridizations and phenotype analysis. G.C., N.B. and W.-L.C. provided technical support. E.K., M.O. and A.V. contributed to scientific discussion. A.J.W. performed 4C-seq experiments and V.H., M.V. and D.G.L performed bioinformatics analysis. A.J.W., D.G.L. and S.M. wrote the manuscript with input from all authors.

COMPETING FINANCIAL INTERESTS STATEMENT

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Barroso E, et al. Identification of the fourth duplication of upstream IHH regulatory elements, in a family with craniosynostosis Philadelphia type, helps to define the phenotypic characterization of these regulatory elements. Am J Med Genet A. 2015;167A:902–6. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.36811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klopocki E, et al. Copy-number variations involving the IHH locus are associated with syndactyly and craniosynostosis. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;88:70–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.ENCODE Project Consortium. The ENCODE (ENCyclopedia Of DNA Elements) Project. Science. 2004;306:636–40. doi: 10.1126/science.1105136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andersson R, et al. An atlas of active enhancers across human cell types and tissues. Nature. 2014;507:455–61. doi: 10.1038/nature12787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bernstein BE, et al. The NIH Roadmap Epigenomics Mapping Consortium. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28:1045–8. doi: 10.1038/nbt1010-1045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hong JW, Hendrix DA, Levine MS. Shadow enhancers as a source of evolutionary novelty. Science. 2008;321:1314. doi: 10.1126/science.1160631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perry MW, Boettiger AN, Bothma JP, Levine M. Shadow enhancers foster robustness of Drosophila gastrulation. Curr Biol. 2010;20:1562–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.07.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dunipace L, Ozdemir A, Stathopoulos A. Complex interactions between cis-regulatory modules in native conformation are critical for Drosophila snail expression. Development. 2011;138:4075–84. doi: 10.1242/dev.069146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cannavo E, et al. Shadow Enhancers Are Pervasive Features of Developmental Regulatory Networks. Curr Biol. 2016;26:38–51. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.11.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Perry MW, Bothma JP, Luu RD, Levine M. Precision of hunchback expression in the Drosophila embryo. Curr Biol. 2012;22:2247–52. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.09.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.St-Jacques B, Hammerschmidt M, McMahon AP. Indian hedgehog signaling regulates proliferation and differentiation of chondrocytes and is essential for bone formation. Genes Dev. 1999;13:2072–86. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.16.2072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Andrey G, et al. Characterization of hundreds of regulatory landscapes in developing limbs reveals two regimes of chromatin folding. Genome Res. 2017;27:223–233. doi: 10.1101/gr.213066.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guo Y, et al. CRISPR Inversion of CTCF Sites Alters Genome Topology and Enhancer/Promoter Function. Cell. 2015;162:900–10. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.07.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rao SS, et al. A 3D map of the human genome at kilobase resolution reveals principles of chromatin looping. Cell. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sanborn AL, et al. Chromatin extrusion explains key features of loop and domain formation in wild-type and engineered genomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:E6456–65. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1518552112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vietri Rudan M, et al. Comparative Hi-C reveals that CTCF underlies evolution of chromosomal domain architecture. Cell Rep. 2015;10:1297–309. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ruf S, et al. Large-scale analysis of the regulatory architecture of the mouse genome with a transposon-associated sensor. Nat Genet. 2011;43:379–86. doi: 10.1038/ng.790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Creyghton MP, et al. Histone H3K27ac separates active from poised enhancers and predicts developmental state. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:21931–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016071107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pollard KS, Hubisz MJ, Rosenbloom KR, Siepel A. Detection of nonneutral substitution rates on mammalian phylogenies. Genome Res. 2010;20:110–21. doi: 10.1101/gr.097857.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Visel A, Minovitsky S, Dubchak I, Pennacchio LA. VISTA Enhancer Browser–a database of tissue-specific human enhancers. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:D88–92. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kraft K, et al. Deletions, Inversions, Duplications: Engineering of Structural Variants using CRISPR/Cas in Mice. Cell Rep. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Buck D, et al. Cernunnos, a novel nonhomologous end-joining factor, is mutated in human immunodeficiency with microcephaly. Cell. 2006;124:287–99. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li G, et al. Lymphocyte-specific compensation for XLF/cernunnos end-joining functions in V(D)J recombination. Mol Cell. 2008;31:631–40. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vera G, et al. Cernunnos deficiency reduces thymocyte life span and alters the T cell repertoire in mice and humans. Mol Cell Biol. 2013;33:701–11. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01057-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hernandez-Martinez R, Castro-Obregon S, Covarrubias L. Progressive interdigital cell death: regulation by the antagonistic interaction between fibroblast growth factor 8 and retinoic acid. Development. 2009;136:3669–78. doi: 10.1242/dev.041954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Witte F, Chan D, Economides AN, Mundlos S, Stricker S. Receptor tyrosine kinase-like orphan receptor 2 (ROR2) and Indian hedgehog regulate digit outgrowth mediated by the phalanx-forming region. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:14211–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009314107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Anderson E, Peluso S, Lettice LA, Hill RE. Human limb abnormalities caused by disruption of hedgehog signaling. Trends Genet. 2012;28:364–73. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2012.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hill RE. How to make a zone of polarizing activity: insights into limb development via the abnormality preaxial polydactyly. Dev Growth Differ. 2007;49:439–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-169X.2007.00943.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hay D, et al. Genetic dissection of the alpha-globin super-enhancer in vivo. Nat Genet. 2016;48:895–903. doi: 10.1038/ng.3605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shin HY, et al. Hierarchy within the mammary STAT5-driven Wap super-enhancer. Nat Genet. 2016;48:904–11. doi: 10.1038/ng.3606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marinic M, Aktas T, Ruf S, Spitz F. An integrated holo-enhancer unit defines tissue and gene specificity of the Fgf8 regulatory landscape. Dev Cell. 2013;24:530–42. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Montavon T, et al. A regulatory archipelago controls Hox genes transcription in digits. Cell. 2011;147:1132–45. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Franke M, et al. Formation of new chromatin domains determines pathogenicity of genomic duplications. Nature. 2016;538:265–269. doi: 10.1038/nature19800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lupianez DG, et al. Disruptions of topological chromatin domains cause pathogenic rewiring of gene-enhancer interactions. Cell. 2015;161:1012–25. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Artus J, Hadjantonakis AK. Generation of chimeras by aggregation of embryonic stem cells with diploid or tetraploid mouse embryos. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;693:37–56. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-974-1_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hooper M, Hardy K, Handyside A, Hunter S, Monk M. HPRT-deficient (Lesch-Nyhan) mouse embryos derived from germline colonization by cultured cells. Nature. 1987;326:292–5. doi: 10.1038/326292a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van de Werken HJ, et al. 4C technology: protocols and data analysis. Methods Enzymol. 2012;513:89–112. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-391938-0.00004-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1754–60. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Grant CE, Bailey TL, Noble WS. FIMO: scanning for occurrences of a given motif. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:1017–8. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Barski A, et al. High-resolution profiling of histone methylations in the human genome. Cell. 2007;129:823–37. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data availability

Gene Expression Omnibus

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?token=sjsdyygmxtinvwl&acc=GSE95062

Code availability

Custom computer codes used to generate results reported in the manuscript will be made available upon request.

URLs

FIMO, http://meme-suite.org/tools/fimoJASPAR database, http://jaspar.binf.ku.dk/

Gene Expression Omnibus

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?token=sjsdyygmxtinvwl&acc=GSE95062