Abstract

Six new compounds, omaezol, intricatriol, hachijojimallenes A and B, debromoaplysinal, and 11,12-dihydro-3-hydroxyretinol have been isolated from four collections of Laurencia sp. These structures were determined by MS and NMR analyses. Their antifouling activities were evaluated together with eight previously known compounds isolated from the same samples. In particular, omaezol and hachijojimallene A showed potent activities (EC50 = 0.15–0.23 µg/mL) against larvae of the barnacle Amphibalanus amphitrite.

Keywords: antifouling, biofouling, barnacle, terpenoid, acetogenin, Laurencia, Rhodophyta

1. Introduction

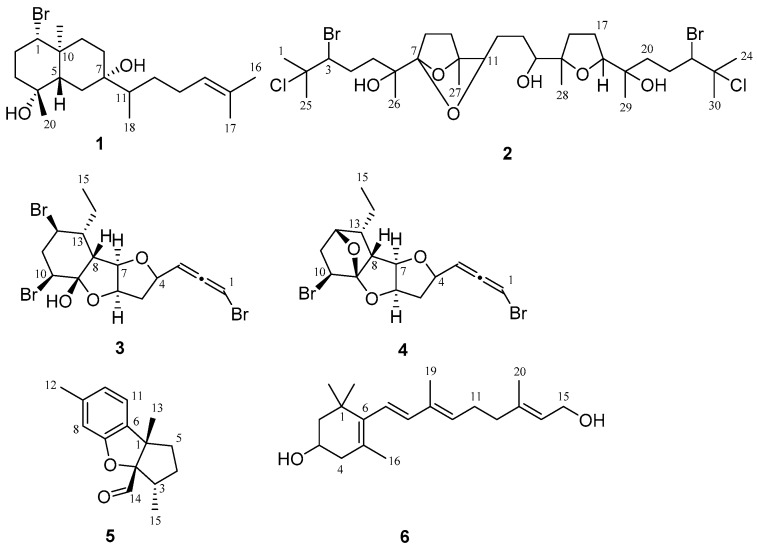

Biofouling is a major cause of increased fuel consumption of ships and facilitates the spread of invasive marine organisms [1]. After many years of utilizing toxic antifoulants to control biofouling, the IMO (International Maritime Organization) banned the use of organotin compounds in 2008, paving the way for the development of environmentally friendly fouling-resistant coatings [2]. In addition, effective and new fouling treatment is needed to control and curb the introduction of non-indigenous species (NIS), that are introduced into local waters partly via ballast water uptake and discharge in vessels. The ballast water management convention will enter into force in September 2017. However, to effectively control NIS introduction, an effective antifouling treatment approach is still needed [3]. Search for natural antifouling compounds to solve biofouling has been “a work in progress” for almost four decades. Lately, a number of natural antifouling products have been reported and some of them have shown potent activities [4,5]. Furthermore, recent efforts to identify molecular mechanisms of antifouling compounds improve the possibility of their industrial importance [6]. As expected, industrial utilization of natural products as antifouling agents would warrant systematic synthetic efforts, and these have been implemented [5]. The total synthesis of 10-isocyano-4-cadinene [7] and dolastatin 16 [8] were achieved by our group [9,10]. The red alga Laurencia sp. is a rich source of biologically active secondary metabolites [11,12] and produces antifouling compounds such as elatol [13], omaezallene [14], and 2,10-dibromo-3-chloro-7-chamigrene [15]. As a continuous effort, our group has been searching for novel and potent antifouling compounds from Laurencia sp. by using barnacle larvae and epiphytic diatom assays. Hence, here we report the structures (Figure 1) and activities of new antifouling compounds from Laurencia sp.

Figure 1.

Structures of new compounds isolated from Laurencia sp.

2. Results

2.1. Omaezol (1) and Intricatriol (2)

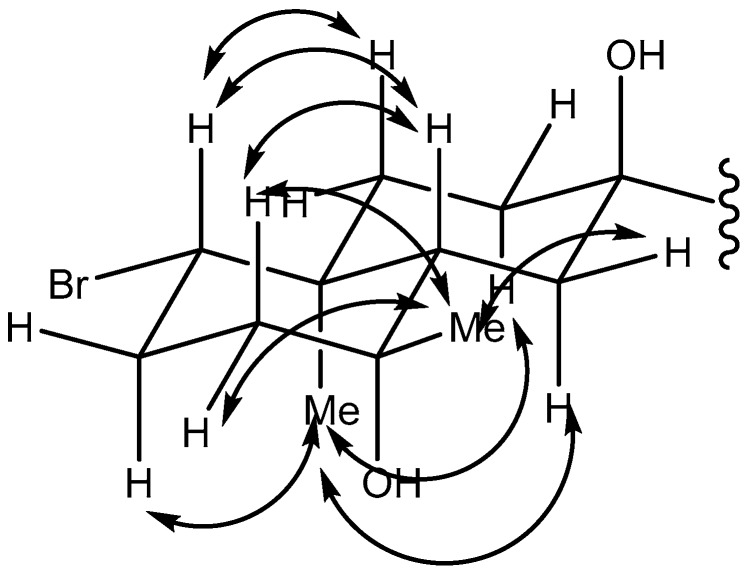

Laurencia sp., which was collected in Omaezaki, Japan, was extracted with MeOH. The extract yielded omaezol (1), intricatriol (2), in addition to the previously isolated omaezallenes and intricatetraol [14]. The molecular formula of 1 was determined to be C20H35BrO2 (m/z 368.1707, calcd. for C20H33BrO, 368.1709 [M − H2O]+) by HR-EIMS (High Resolution-Electron Ionization Mass Spectrometry), suggesting three degrees of unsaturation. The existence of a hydroxy group was revealed by an IR absorption at 3386 cm−1. 13C NMR data (Table 1) showed the presence of one double bond, suggesting a bicyclic structure. COSY correlations connected C-1 to C-3. HMBC peaks from H-19 to C-1, 5, 9, 10 and from H-20 to C-3, 4, 5 concluded a cyclohexane ring (Figure S1). Based on 13C NMR chemical shifts, a bromine atom is attached to C-1 (δ 67.6) and a hydroxy group is connected to C-4 (δ71.4). A side chain was determined by COSY correlation (H-11/H-18 and H-12/H-13) and HMBC peaks (H-18/C-7, 12 and H-14/C-13, 16, 17). Another hydroxy group is attached to C-7 (δ 74.6). Overlapping of NMR chemical shifts (C-6; δ 32.1, C-8; δ 31.8, C-9; δ 38.7, C-10; δ 39.4, H-6; δ 1.48, H-8; δ 1.49) hampered the positioning of the two remaining methylenes. However, HSQC-TOCSY peaks from H-8 to C-9 and H-6 to C-5 concluded the planar structure of 1. NOESY correlations determined relative configurations of the trans-decalin (Figure 2).

Table 1.

1H and 13C NMR spectroscopic data for compounds 1 and 2 in CDCl3.

| Carbon Number | Compound 1 | Compound 2 | Carbon Number | Compound 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 13C | 1H | 13C | 1H | 13C | 1H | ||

| 1 | 67.6 | 3.91 | 27.8 | 1.689 | 24 | 27.5 | 1.695 |

| 2 | 30.2 | 2.44, 2.01 | 72.0 | 23 | 72.0 | ||

| 3 | 41.9 | 1.55, 1.70 | 67.1 | 4.07 | 22 | 67.1 | 4.08 |

| 4 | 71.4 | 28.7 | 1.85, 2.61 | 21 | 28.9 | 1.75, 2.45 | |

| 5 | 48.2 | 1.10 | 36.8 | 1.72, 1.89 | 20 | 36.9 | 1.47, 1.72 |

| 6 | 32.1 | 1.48, 2.00 | 72.2 | 19 | 73.3 | ||

| 7 | 74.6 | 113.4 | 18 | 84.3 | 3.85 | ||

| 8 | 31.8 | 1.49, 1.90 | 27.9 | 1.60, 1.70 | 17 | 26.4 | 1.93 |

| 9 | 38.7 | 1.05, 1.76 | 32.8 | 1.91 | 16 | 32.7 | 1.57, 2.19 |

| 10 | 39.4 | 86.7 | 15 | 85.6 | |||

| 11 | 33.6 | 1.67 | 84.7 | 3.61 | 14 | 76.0 | 3.57 |

| 12 | 30.2 | 1.52 | 29.6 | 1.55, 2.40 | 13 | 29.4 | 1.74 |

| 13 | 26.5 | 1.12 | 25 | 33.1 | 1.785 | ||

| 14 | 124.3 | 5.10 | 30 | 32.9 | 1.793 | ||

| 15 | 131.7 | 26 | 21.2 | 1.28 | |||

| 16 | 25.5 | 1.70 | 29 | 24.5 | 1.26 | ||

| 17 | 17.6 | 1.62 | 27 | 17.6 | 1.45 | ||

| 18 | 12.3 | 0.90 | 28 | 23.0 | 1.19 | ||

| 19 | 14.4 | 1.26 | |||||

| 20 | 29.7 | 1.18 | |||||

Figure 2.

Key NOESY correlations observed in 2D NMR of compound 1.

The molecular formula of 2 was determined to be C30H52Br2Cl2O6 (m/z 757.1584, calcd. for C30H53Br2Cl2O6, 757.1581 [M + H]+) by HR-FABMS (High Resolution-Fast Atom Bombardment Mass Spectrometry). The 1H and 13C NMR spectra of 2 (Table 1) were similar to intricatetraol [16,17], but were not symmetric. The 2D NMR interpretations (Figure S2) showed that both compounds had the same carbon skeleton. However, 13C chemical shift changes were observed (C-7: δ 84.1 in intricatetraol, δ 113.4 in 2, and C-11: δ 77.5 in intricatetraol, δ 84.7 in 2). C-7 in 2 was proposed to be an acetal carbon and C-11 was suggested to be a part of an ether instead of a secondary alcohol to make another five-membered ring. In conclusion, the planar structure of 2 was determined and its configuration was assumed to be the same as intricatetraol [16,17], which was extracted from the same sample.

2.2. Hachijojimallenes A (3) and B (4)

Hachijojimallenes A (3) and B (4) were isolated together with N-methyl-2,3,6-tribromoindole [18] and pinnaterpene C [19] from a red alga, Laurencia sp., which was collected in Hachijojima Island, Japan. Based on HR-EIMS data, the molecular formula of 3 was determined to be C15H19Br3O3 (m/z 466.8851, calcd. for C15H18Br3O2, 466.8852 [M − OH]+). The existence of a bromoallene moiety was suggested by an IR absorption at 1957 cm−1, 13C NMR chemical shifts (δ 74.1, 99.4, and 201.9), and 1H NMR chemical shifts (δ 5.45 and 6.08) (Table 2). COSY correlations established a carbon skeleton C-3—C-8—C-13—C-10 and an ethyl group. 13C chemical shifts revealed that C-4, 6, and 7 were oxymethines and C-10 and 12 were brominated. These carbons and an acetal carbon (δ 102.1) were assembled by HMBC data to conclude the planar structure of 3 (Figure S3). Relative configurations were determined by NOEs (H-6/H-10, H-10/H-11 α, H-11 α/H-12, H-7/H-12, and H-8/H-13).

Table 2.

1H and 13C NMR spectroscopic data for compounds 3–5 in CDCl3.

| Carbon Number | Compound 3 | Compound 4 | Compound 5 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 13C | 1H | 13C | 1H | 13C | 1H | |

| 1 | 74.1 | 6.08 | 74.0 | 3.09 | 58.7 | |

| 2 | 201.9 | 201.9 | 103.4 | |||

| 3 | 99.4 | 5.45 | 100.0 | 5.48 | 42.4 | 2.59 |

| 4 | 73.8 | 4.73 | 74.1 | 4.72 | 31.7 | 1.26, 1.74 |

| 5 | 39.3 | 1.81, 2.26 | 39.6 | 1.82, 2.35 | 43.0 | 1.74, 1.92 |

| 6 | 79.4 | 4.56 | 88.6 | 5.11 | 131.6 | |

| 7 | 81.4 | 4.61 | 82.8 | 4.77 | 159.4 | |

| 8 | 50.5 | 2.77 | 51.0 | 3.19 | 110.0 | 6.72 |

| 9 | 102.1 | 119.7 | 138.8 | |||

| 10 | 53.6 | 4.07 | 42.8 | 4.13 | 122.1 | 6.74 |

| 11 | 44.3 | 2.50, 2.76 | 40.6 | 1.74, 2.70 | 122.4 | 6.92 |

| 12 | 51.3 | 3.79 | 75.6 | 4.03 | 21.5 | 2.33 |

| 13 | 44.7 | 1.97 | 50.2 | 2.13 | 24.2 | 1.31 |

| 14 | 24.7 | 1.47, 2.11 | 23.3 | 1.44, 1.60 | 203.5 | 9.78 |

| 15 | 11.6 | 1.03 | 12.5 | 0.99 | 13.1 | 1.04 |

| 9-OH | 3.65 | |||||

The molecular formula of 4 was determined to be C15H18Br2O3 (m/z 403.9627, calcd. for C15H18Br2O3, 403.9617 [M]+) by HR-EIMS, suggesting the existence of another ring. The striking difference in its 13C NMR (Table 2) was observed in C-9 (3; δ 102.1, 4; δ 119.7) and C-12 (3; δ 51.3, 4; δ 75.6). In addition, HMBC was observed from H-12 to C-9. In conclusion, the hemiacetal in 3 was replaced by acetal in 4 to form an ether between C-9 and C-12, which was debrominated at C-12. NOEs of 4 supported its relative configurations, similar to those of 3.

2.3. Debromoaplysinal (5)

Re-investigation of the red alga L. okamurae, collected at Oshoro Bay, Hokkaido, Japan, yielded debromoaplysinal (5). The molecular formula of 5 was determined to be C15H18O2 (m/z 231.1379, calcd. for C15H19O2, 231.1380 [M + H]+) by ESI-TOFMS. Its 1D NMR spectra (Table 2) revealed the existence of an aldehyde and a trisubstituted benzene. COSY and HMBC correlations (Figure S4) clarified its planar structure, which is similar to aplysinal and debromoaplysinol. In fact, chemical shifts in the trisubstituted benzene of 5 are similar to those of debromoaplysinol, and those in the cyclopentane of 5 are similar to those of aplysinal. NOESY peaks between H-13 and H-14 suggested cis configuration of Me-13 and the aldehyde. Irradiation of H-3 by DPFGSE 1D NOE showed the enhancement of H-13. In conclusion, H-3, Me-13, and the aldehyde are located on the same face.

2.4. 11,12-Dihydro-3-hydroxyretinol (6)

Re-investigation of the red alga L. nipponica collected at Muroran, Hokkaido, Japan, yielded 11,12-dihydro-3-hydroxyretinol (6), along with three known halogenated chamigrene-type sesquiterpenoids [20,21]. The molecular formula of 6 was deduced to be C20H32O2 (m/z 304.2400, calcd. for C20H32O2, 304.2397 [M]+) by HR-EIMS, accounting for five degrees of unsaturation. The 1H- and 13C-NMR spectroscopic data (Table 3) as well as the HSQC experiment of 6 showed the presence of eight sp2 carbons, three vinyl methyls, a pair of geminal methyls, an oxymethylene, an oxymethine, four methylenes, and a quaternary carbon. These signals explained four degrees of unsaturation, implying that one ring was present in 6. COSY and HMBC data (Figure S5) clearly indicated the gross structure of 6. The E configurations of double bonds were deduced from the 1H-1H coupling constants (3J7–8 15.9 Hz) and 13C-NMR chemical shifts of vinyl methyls (C-19; δ 13.2, and C-20; δ 17.2). Unfortunately, the configuration at C-3 was not determined due to its limited amount.

Table 3.

1H and 13C NMR spectroscopic data for compound 6 in CDCl3.

| Carbon Number | 13C | 1H | Carbon Number | 13C | 1H |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 37.9 | 11 | 27.5 | 2.29 | |

| 2 | 49.1 | 1.47, 1.76 | 12 | 40.0 | 2.12 |

| 3 | 65.9 | 4.00 | 13 | 140.0 | |

| 4 | 43.2 | 2.02, 2.37 | 14 | 124.2 | 5.44 |

| 5 | 125.9 | 15 | 60.1 | 4.18 | |

| 6 | 138.2 | 16 | 22.4 | 1.71 | |

| 7 | 124.0 | 5.92 | 17 | 31.0 | 1.06 |

| 8 | 139.0 | 6.00 | 18 | 29.5 | 1.06 |

| 9 | 134.6 | 19 | 13.2 | 1.79 | |

| 10 | 131.4 | 5.40 | 20 | 17.2 | 1.71 |

2.5. Antifouling Activity

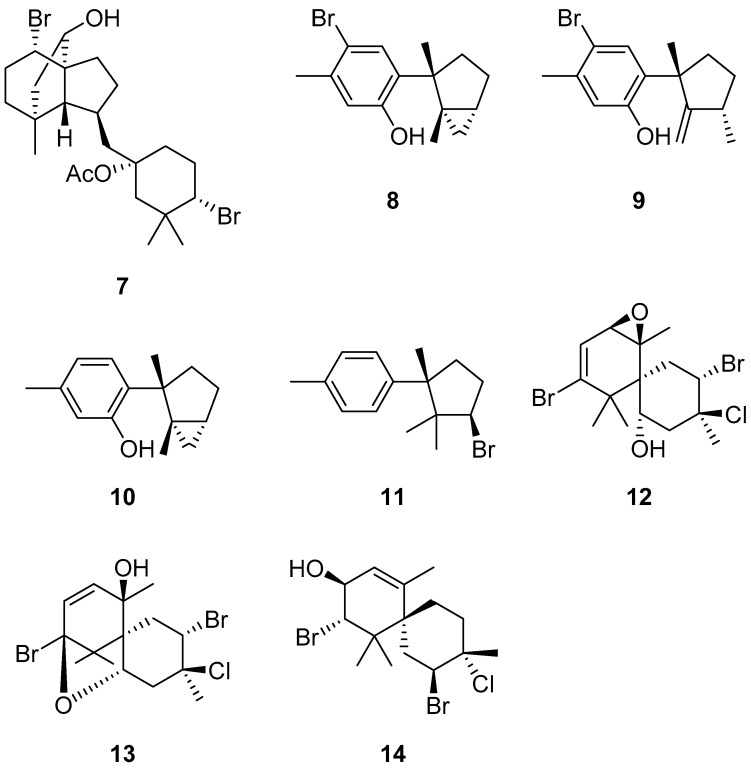

Most of the compounds obtained in this study were tested for antifouling activity against larvae of the barnacle Amphibalanus amphitrite (Table 4). The antifouling activity of 1 was potent (EC50 = 0.23 µg/mL) and its toxicity was low (LC50 = 3.7 µg/mL), while 2 was not potent (EC50 > 10 µg/mL). The antifouling activity of 3 was potent (EC50 = 0.15 µg/mL) and its toxicity was low (LC50 = 9.8 µg/mL), while 4 was a little less potent (EC50 = 0.31 µg/mL, LC50 = 6.8 µg/mL). The antifouling activity of the known compound, pinnaterpene C (7, EC50 = 0.82 µg/mL, LC50 > 10 µg/mL), was similar to that of 4, while another known compound, N-methyl-2,3,6-tribromoindole, showed weak activity (EC50 = 4.3 µg/mL, not toxic at 10 µg/mL). Compound 5 also showed moderate antifouling activity (EC50 = 1.0 µg/mL) and did not kill any larvae at 10 µg/mL. Some known compounds (Figure 3) isolated from L. okamurae were tested. Three aromatic sesquiterpenoids [22] showed antifouling activities (laurinterol 8: EC50 = 0.65 µg/mL, LC50 = 5.8 µg/mL; isolaurinterol 9: EC50 = 0.34 µg/mL, LC50 > 10 µg/mL; debromolaurinterol 10: EC50 = 0.5 µg/mL, LC50 > 10 µg/mL), while α-bromocuparene (11) was inactive. Three sesquiterpenoids (Figure 3) isolated from L. nipponica collected in Muroran showed antifouling activities (prepacifenol 12: EC50 = 0.63 µg/mL, LC50 > 10 µg/mL; pacifenol 13: EC50 = 2.36 µg/mL, LC50 > 10 µg/mL; 2,10-dibromo-3-chloro-9-hydroxy-α-chamigrene 14 EC50 = 2.51 µg/mL, LC50 > 10 µg/mL). In addition, anti-diatom activities against the epiphytic marine diatoms, Nitzschia sp. and Cylindrotheca closterium, were tested for three chamigrenes and 6. Compounds 6, 12, and 14 showed inhibition against both diatoms at 5–10 µg/cm2.

Table 4.

Antifouling activities (µM) against barnacle larvae.

| Compound | EC50 | LC50 |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.59 | 9.6 |

| 2 | — | — |

| 3 | 0.31 | 20 |

| 4 | 0.76 | 17 |

| 5 | 4.3 | — |

| 7 | 1.6 | — |

| 8 | 2.2 | 20 |

| 9 | 1.2 | — |

| 10 | 2.3 | — |

| 11 | — | — |

| 12 | 1.5 | — |

| 13 | 5.5 | — |

| 14 | 6.1 | — |

| CuSO4 | 0.72 | 1.4 |

—: EC50 or LC50 is more than 10 µg/mL.

Figure 3.

Structures of tested known compounds isolated from Laurencia sp.

3. Discussion

From a chemical point of view, 1 is a rare halo-diterpenoid, prenylated selinene-type compound like anhydroaplysiadiol [23]. Oxasqualenoids such as 2 have been proposed to be synthesized by the epoxide-opening cascades. These reactions could be catalyzed by vanadium-dependent bromoperoxidases [24]. However, we do not know how different cyclization patterns are controlled to produce 2 and the similar compound intricatetraol [16,17]. Although most of C15 acetogenins from Laurencia contain only ether rings, 3 and 4 contain a carbocyclic ring, similar to lembynes [25]. Compound 5 is one of common laurane-type sesquiterpenes. Retinols occur in nature only in animals and in the limited green algae Caulerpa sp. [26] This is the first record of a retinane-type diterpene (6) isolated from Laurencia. Although the genus of Laurencia is one of the most studied organisms in marine natural product chemistry [11,12], recent isolation techniques yielded six new compounds in this study. Twelve compounds showed antifouling activities against the barnacle larvae. Notably, the activities of 1 and 3 were equivalent to CuSO4 (EC50 = 0.18 µg/mL). Three compounds showed antifouling activities against diatoms. However, most of compounds isolated from Laurencia sp. so far have not been tested for antifouling activity. Our results suggest that Laurencia is a potential source of antifouling compounds.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. General Procedures

IR spectra were measured on a JASCO IR-700 spectrophotometer (JASCO, Tokyo, Japan). 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra were recorded in CDCl3 by using JEOL JNM-ECA600 (JEOL, Tokyo, Japan), JEOL JNM-EX400 (JEOL, Tokyo, Japan), or BRUKER ASX300 spectrometer (Bruker BioSpin, Faellanden, Switzerland), unless otherwise stated. EI-MS were obtained on a JEOL JMS-FABmate spectrometer (JEOL, Tokyo, Japan). FAB-MS were obtained on a JEOL JMS-HX110 spectrometer (JEOL, Tokyo, Japan). ESI-MS were obtained on a JEOL JMS-700TZ (JEOL, Tokyo, Japan) or BRUKER DALTONICS micro TOF-HS focus spectrometer (Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany). Optical rotations were recorded on a HORIBA SEPA-300 polarimeter (Horiba, Kyoto, Japan).

4.2. Plant Material

Algal samples of Laurencia sp. were collected at Omaezaki, Shizuoka Prefecture, and Hachijojima Island, Tokyo, Japan. L. okamurae was collected at Oshoro Bay and L. nipponica was collected at Muroran, Hokkaido, Japan. The voucher specimens are deposited in the Herbarium of Graduate School of Science, Hokkaido University.

4.3. Omaezol and Intricatriol

The dried algal sample (250 g) was extracted and separated as described in a previous paper [12]. Omaezol (1, 3.2 mg) and intricatriol (2, 17.0 mg) were isolated by HPLC (YMC-Pack Pro C18 (YMC, Kyoto, Japan) with CH3CN and H2O) from the omaezallene containing silica-gel fraction.

1: −67.4 (c 0.17, CHCl3); IR (neat), νmax 3428, 1259, 1185, 1088, 1065, 954, 801 cm−1; 1H NMR and 13C NMR, see Table 1.

2: −45.2 (c 0.39, CHCl3) ; IR (neat), νmax 3414, 2972, 1451, 1369, 1214, 1101, 756 cm−1; 1H NMR and 13C NMR, see Table 1.

4.4. Hachijojimallenes A and B

The air-dried algae (80 g) were soaked in MeOH (500 mL) for seven days. The MeOH solution was concentrated in vacuo, and the residue was partitioned between EtOAc and H2O. The EtOAc layer was then washed with water, dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, and evaporated in vacuo to leave a dark green oily substance (1.23 g). The extract (700 mg) was fractionated by Si gel CC with a step gradient (hexane and EtOAc). The fraction (41 mg) eluted with hexane-EtOAc (9:1) was further subjected to PTLC (preparative thin-layer chromatography) with hexane to give 1-methyl-2,3,6-tribromoindole (4.0 mg), which was determined on the basis of 1H NMR and MS data. The fraction (411 mg) eluted with hexane–EtOAc (7:3) was further chromatographed on a Si gel column with hexane–EtOAc (3:1) (each eluate, 10 mL) to give 10 fractions. The fourth fraction (79.1 mg) was then separated by PTLC with hexane-EtOAc (3:1) to afford hachijojimallene B (4) (3.5 mg). The combined fifth and sixth fractions (74.9 mg) were further separated by repeated PTLC with hexane–EtOAc (1:1) to give hachijojimallene A (3) (40.0 mg). The seventh fraction (43.8 mg) was subjected to PTLC with hexane–EtOAc (3:1) followed by HPLC (Develosil-ODS-T-5 with CH3CN and H2O) to give pinnaterpene C (7, 15.0 mg).

3: −88.2 (c 0.13, CHCl3); IR (neat), νmax 3490, 1957, 1258, 1184, 1165, 1143, 1120, 1038, 959, 788, 756 cm−1; 1H NMR and 13C NMR, see Table 1.

4: −151 (c 0.71, CHCl3); IR (neat), νmax 1950, 1243, 1181, 1127, 1080, 1045, 1022, 970, 855, 821 cm−1; 1H NMR and 13C NMR, see Table 1.

4.5. Debromoaplysinal

The air-dried algae (100 g) were soaked in MeOH (3 L) for seven days. The MeOH solution was concentrated in vacuo, and the residue was partitioned between EtOAc and H2O. The EtOAc layer was then washed with water, dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, and evaporated in vacuo to obtain the crude extract (4.3 g). The extract (2.1 g) was fractionated by Si gel column chromatography with a step gradient (hexane and EtOAc). The fraction (1.4 g) eluted with hexane-EtOAc (3:1) was further subjected to two sets of Si gel column chromatography and PTLC with toluene to give debromoaplysinal (5) (0.9 mg). The other known compounds (laurinterol 8, 30.6 mg; isolaurinterol 9, 12.4 mg; debromolaurinterol 10, 11.0 mg; α-bromocuparene 11, 1.1 mg) were isolated from the same fraction (hexane–EtOAc 3:1) in a similar way.

5: −91.9 (c 0.08, CHCl3); IR (neat), νmax 2927, 2856, 1731, 1593, 1499, 1456, 1377, 1266, 1146, 1117, 971, 805 cm−1; 1H NMR and 13C NMR, see Table 1.

4.6. 11,12-Dihydro-3-hydroxyretinol

Fresh algal sample (400 g wet weight) was extracted in MeOH at room temperature for three days. The resulting MeOH extract was concentrated in vacuo and partitioned between diethyl ether and H2O. The diethyl ether fraction (340 mg) was subjected to Si gel CC eluting with a gradient of hexane and EtOAc in an increasing polarity. Fraction 4, eluted with hexane-EtOAc (3:1), was subjected to PTLC to yield pacifenol (12, 4.1 mg) and prepacifenol (13, 6.3 mg). Fraction 5, eluted with hexane-EtOAc (1:1), was subjected to PTLC with CHCl3-MeOH (97:3) to yield 2,10-dibromo-3-chloro-9-hydroxy-α-chamigrene (14, 7.3 mg). Fraction 7, eluted with hexane-EtOAc (1:3), gave 6 (1.3 mg) after purification with PTLC using CHCl3-MeOH (95:5).

6: −61.9 (c 0.07, CHCl3); 1H NMR and 13C NMR, see Table 1.

4.7. Antifouling Assay

An antifouling assay against larvae of the barnacle Amphibalanus amphitrite was conducted according to the previous literature [9]. The antifouling assay against diatoms Nitzschia sp. and Cylindrotheca closterium was conducted as follows. The diatoms were maintained in test tubes under 16 h light and 8 h dark cycle conditions at 25 °C in modified Jorgensen’s medium. Pure compounds were applied to a sample zone (16 mm in diameter) of cellulose TLC aluminum sheet (58 × 58 mm), and then each treated sheet was placed in Petri dish (15 × 90 mm in diameter). After that, 25-mL aliquots of modified Jorgensen’s medium were introduced into Petri dishes with treated sheets, and inoculated with 1 mL of cultivated diatom suspension in equivalent cell densities. Petri dishes were sealed with Parafilm to ensure a closed system, and were incubated under the same conditions. Cell growth was estimated daily, and the adhesive condition was evaluated and compared to those of the control after seven days of incubation.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 16H04975 and JST. The authors would like to thank Tomohiko Kawamura (University of Tokyo) for providing the diatoms.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at www.mdpi.com/1660-3397/15/9/267/s1, Figure S1: Key 2D NMR correlations of compound 1; Figure S2: Key 2D NMR correlations of compound 2; Figure S3: Key 2D NMR correlations of compound 3; Figure S4: Key 2D NMR correlations of compound 5; Figure S5: Key 2D NMR correlations of compound 6; Figure S6: 1H NMR spectrum of omaezol (1) in CDCl3; Figure S7: 13C NMR spectrum of omaezol (1) in CDCl3; Figure S8: 1H NMR spectrum of intricatriol (2) in CDCl3; Figure S9: 13C NMR spectrum of intricatriol (2) in CDCl3; Figure S10: 1H–1H COSY spectrum of intricatriol (2) in CDCl3; Figure S11: HSQC spectrum of intricatriol (2) in CDCl3; Figure S12: HMBC spectrum of intricatriol (2) in CDCl3; Figure S13: NOESY spectrum of intricatriol (2) in CDCl3; Figure S14: 1H NMR spectrum of hachijojimallene A (3) in CDCl3; Figure S15: 13C NMR spectrum of hachijojimallene A (3) in CDCl3; Figure S16: 1H–1H COSY spectrum of hachijojimallene A (3) in CDCl3; Figure S17: HMQC spectrum of hachijojimallene A (3) in CDCl3; Figure S18: HMBC spectrum of hachijojimallene A (3) in CDCl3. Figure S19: NOESY spectrum of hachijojimallene A (3) in CDCl3; Figure S20: 1H NMR spectrum of hachijojimallene B (4) in CDCl3; Figure S21: 13C NMR spectrum of hachijojimallene B (4) in CDCl3. Figure S22. HMQC spectrum of hachijojimallene B (4) in CDCl3; Figure S23: HMBC spectrum of hachijojimallene B (4) in CDCl3; Figure S24: 1H NMR spectrum of debromoaplysinal (5) in CDCl3; Figure S25: 13C NMR spectrum of debromoaplysinal (5) in CDCl3; Figure S26: DPFGSE 1D NOE spectrum of debromoaplysinal (5) in CDCl3; Figure S27: 1H NMR spectrum of 11,12-dihydro-3-hydroxyretinol (6) in CDCl3; Figure S28: 13C NMR spectrum of 11,12-dihydro-3-hydroxyretinol (6) in CDCl3.

Author Contributions

T.O. conceived and designed the experiments; Y.O., M.W., H.M., C.S.V., and M.S. performed the experiments and analyzed the data on omaezol, intricatriol, and hachijojimallenes; T.I. and K.K. contributed the debromoaplysinal experiments; T.K. and T.I. contributed the 11,12-dihydro-3-hydroxyretinol experiments; E.Y. and Y.N. contributed the larval assays; T.O. wrote the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The founding sponsors had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, and in the decision to publish the results.

References

- 1.Davidson I., Scianni C., Hewitt C., Everett R., Holm E., Tamburri M., Ruiz G. Assessing the drivers of ship biofouling management—Aligning industry and biosecurity goals. Biofouling. 2016;32:411–428. doi: 10.1080/08927014.2016.1149572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Callow J.A., Callow M.E. Trends in the development of environmentally friendly fouling-resistant marine coatings. Nat. Commun. 2011;2:244. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fernandes J.A., Santos L., Vance T., Fileman T., Smith D., Bishop J.D.D., Viard F., Queirós A.M., Merino G., Vuisman E., et al. Costs and benefits to European shipping of ballast-water and hull-fouling treatment: Impacts of native and non-indigenous species. Mar. Policy. 2016;64:148–155. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2015.11.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Almeida J.R., Vasconcelos V. Natural antifouling compounds: Effectiveness in preventing invertebrate settlement and adhesion. Biotechnol. Adv. 2015;33:343–357. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2015.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Qian P., Li Z., Xu Y., Fusetani N. Marine natural products and their synthetic analogs as antifouling compounds: 2009–2014. Biofouling. 2015;31:101–122. doi: 10.1080/08927014.2014.997226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Qian P., Chen L., Xu Y. Molecular mechanisms of antifouling compounds. Biofouling. 2013;29:381–400. doi: 10.1080/08927014.2013.776546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Okino T., Yoshimura E., Hirota H., Fusetani N. New antifouling sesquiterpenes from four nudibranchs of the family Phyllidiidae. Tetrahedron. 1996;52:9447–9454. doi: 10.1016/0040-4020(96)00481-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tan L.T., Goh B.P.L., Tripathi A., Lim M.G., Dickinson G.H., Lee S.S.C., Teo S.L.M. Natural antifoulants from the marine cyanobacterium Lyngbya majuscula. Biofouling. 2010;26:685–695. doi: 10.1080/08927014.2010.508343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Casalme L.O., Yamauchi A., Sato A., Petitbois J.G., Nogata Y., Yoshimura E., Okino T., Umezawa T., Matsuda F. Total synthesis and biological activity of dolastatin 16. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2017;15:1140–1150. doi: 10.1039/C6OB02657E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nishikawa K., Nakahara H., Shirokura Y., Nogata Y., Yoshimura E., Umezawa T., Okino T., Matsuda F. Total synthesis of 10-isocyano-4-cadinene and its stereoisomers and evaluations of antifouling activities. J. Org. Chem. 2011;76:6558–6573. doi: 10.1021/jo2008109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Suzuki M., Vairappan C.S. Halogenated secondary metabolites from Japanese species of the red algal genus Laurencia (Rhodomelaceae, Ceramiales) Curr. Top. Phytochem. 2005;7:1–34. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang B.G., Gloer J.B., Ji N.Y., Zhao J.C. Halogenated organic molecules of Rohodomelaceae origin: Chemistry and biology. Chem. Rev. 2013;113:3632–3685. doi: 10.1021/cr9002215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.König G.M., Wright A.D. Laurencia rigida: Chemical investigation of its antifouling dichloromethane extract. J. Nat. Prod. 1997;60:967–970. doi: 10.1021/np970181r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Umezawa T., Oguri Y., Matsuura H., Yamazaki S., Suzuki M., Yoshimura E., Furuta T., Nogata Y., Serisawa Y., Matsuyama-Serisawa K., et al. Omaezallene from red alga Laurencia sp.: Structure elucidation, total synthesis, and antifouling activity. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014;53:3909–3912. doi: 10.1002/anie.201311175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Al-Lihaibi S.S., Abdel-Lateff A., Alarif W.M., Nogata Y., Ayyad S.N., Okino T. Potent antifouling metabolites form Red Sea organisms. Asian J. Chem. 2015;27:2252–2256. doi: 10.14233/ajchem.2015.18701. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Suzuki M., Matsuo Y., Takeda S., Suzuki T. Intricatetraol, a halogenated triterpene alcohol from the red alga Laurencia intricata. Phytochemistry. 1993;33:651–656. doi: 10.1016/0031-9422(93)85467-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morimoto Y., Okita T., Takaishi M., Tanaka T. Total synthesis and determination of the absolute configuration of (+)-intricatetraol. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007;46:1132–1135. doi: 10.1002/anie.200603806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carter G.T., Rimehart K.L., Jr., Li L.H., Kuentzel S.L., Connor J.L. Brominated indoles from Laurencia brongniartii. Tetrahedron Lett. 1978;19:4479–4482. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4039(01)95257-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fukuzawa A., Kumagai Y., Masamune T., Furusaki A., Matsumoto T., Katayama C. Pinnaterpenes A, B, and C, new dibromoditerpenes from the red alga Laurencia pinnata Yamada. Chem. Lett. 1982;11:1389–1392. doi: 10.1246/cl.1982.1389. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Suzuki M., Kurosawa E., Furusaki A. The structure and absolute stereochemistry of a halogenated chamigrene derivative from the red alga Laurencia species. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1988;61:3371–3373. doi: 10.1246/bcsj.61.3371. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abe T., Masuda M., Suzuki T., Suzuki M. Chemical races in the red alga Laurencia nipponica (Rhodomelaeae, Ceramiales) Phycol. Res. 1999;47:87–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1835.1999.tb00288.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Suzuki M., Kurosawa E. Halogenated and non-halogenated aromatic sesquiterpenes from the red algae Laurencia okamurae Yamada. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1979;52:3352–3354. doi: 10.1246/bcsj.52.3352. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Takahashi Y., Suzuki M., Abe T., Masuda M. Anhydroaplysiadiol from Laurencia japonensis. Phytochemistry. 1998;48:987–990. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(98)00099-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaneko K., Washio K., Umezawa T., Matsuda F., Morikawa M., Okino T. cDNA cloning and characterization of vanadium-dependent bromoperoxidases from the red alga Laurencia nipponica. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2014;78:1310–1319. doi: 10.1080/09168451.2014.918482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vairappan C.S., Daitoh M., Suzuki M., Abe T., Masuda M. Antibacterial halogenated metabolites from the Malaysian Laurencia species. Phytochemistry. 2001;58:291–297. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(01)00243-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Blackman A.J., Wells R.J. Caulerpol, a diterpene alcohol, related to vitamin A, from Caulerpa brownii (algae) Tetrahedron Lett. 1976;17:2729–2730. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)77810-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.