Abstract

The etiology of testicular germ cell tumor (TGCT) remains obscure, and accumulating evidence suggests that postnatal environmental or lifestyle factors may play a role. To investigate whether consumption of alcoholic beverages during adolescence or adulthood is associated with TGCT risk, we analyzed data from a USA population-based case-control study of 540 18–44 year-old TGCT cases, and 1,280 age-matched controls. Participants were queried separately about consumption of beer, wine and liquor during grades 7–8, grades 9–12 and the 5 years before reference date (date of diagnosis for cases and corresponding date for controls). We used logistic regression to estimate odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the association of TGCT risk with alcoholic beverage consumption during the different periods, both total and by specific beverage types, and separately for seminomas and nonseminomas. Compared with non-drinkers in the 5 years before reference date, the OR (95% CI) for 1–6, 7–13, and ≥14 drinks per week were 1.20 (0.85, 1.69), 1.23 (0.81, 1.85), and 1.56 (1.03, 2.37), respectively (p-trend=0.04). The corresponding results for alcohol consumption in grades 9–12 were 1.39 (1.06, 1.82), 1.07 (0.72, 1.60), 1.53 (1.01, 2.31) (p-trend=0.05). Alcohol consumption in grades 7–8 was uncommon and no statistically significant associations with TGCT were observed. Associations with alcohol consumption in the 5 years before reference date appeared stronger for nonseminomas than for seminomas, but the differences were not statistically significant (p>0.05). Associations were similar across different alcoholic beverage types. Consumption of alcoholic beverages may be associated with an increased TGCT risk.

Keywords: testicular germ cell tumor, alcohol drinking, epidemiology, seminoma, nonseminoma

BACKGROUND

Over the past several decades, testicular germ cell tumor (TGCT) incidence has increased dramatically among males of European ancestry aged 15 and older.1,2 In aggregate, the rapid increases in incidence and distinct birth cohort effects3,4 suggest an etiological role for environmental or lifestyle factors.

Alcohol is an established human carcinogen at multiple anatomic sites5 and causes perturbation of the hypothalmic-pituitary-gonadal axis, resulting in depressed testosterone and luteinizing hormone, testicular atrophy, gynecomastia, reduced spermatogenesis, and disrupted sexual function in alcoholic men.6–8 The results of previous epidemiological investigations of the association between alcohol consumption and TGCT risk have been inconsistent,9–14 and none have examined alcohol consumption specifically during adolescence, when the testes may be particularly vulnerable to environmental influences.15 We therefore examined associations between alcohol consumption during adolescence and adulthood and risk of TGCT.

METHODS

Study Population

The Adult Testicular Lifestyle and Blood Specimen (ATLAS) Study is a U.S. population-based case-control study of TGCT among 18–44-years-old male residents of 3 counties in western Washington State diagnosed with a first, invasive TGCT between January 1999 and December 2008. We identified potentially eligible cases from the Cancer Surveillance System, a part of the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results Program of the National Cancer Institute, based on International Classification of Diseases for Oncology topography C62.0 to 62.9 and histology codes 9060 to 9091.16 Of the 789 eligible cases identified, we recruited 540 (68.4%) into the study. The primary reasons that eligible men did not participate were direct refusal (n=127), inability to be located (n=55), and having moved from the study region (n=46). Because controls were ascertained through random-digit dialing of landline residential telephone numbers, we excluded from the current analysis cases that did not have a landline residential telephone at the time of diagnosis (n=50).

Controls were men without a history of TGCT who resided in the same 3 counties as controls during the case diagnosis period, were frequency-matched to the cases on 5-year age groups, and were identified using landline random digit dialing as described previously.17 Of the 2526 eligible controls who were identified, we recruited and interviewed 1280 men (50.7%). The primary reason that eligible controls did not participate was direct refusal (n=1085). The household screening proportion was 79.0%. The screening response, combined with the interview proportion, yielded an overall estimated response proportion of 40.0%.

Interviews

Cases and controls were interviewed in-person by trained interviewers using a structured questionnaire. All questions referred to the period before each participant’s reference date. For each case, the reference date was the month and year of his TGCT diagnosis. Each control was assigned a reference date that was selected at random from among possible case diagnosis years for cases identified as of the time the control was selected. The pool of potential case diagnosis years was adjusted prospectively with the intent that the recruited controls would be frequency-matched to cases on reference year. ATLAS participants were asked whether they had consumed 12 or more drinks of alcoholic beverages over their lifetime. Those who answered no were considered lifetime abstainers. Respondents that answered affirmatively were queried about their consumption of alcoholic beverages during three specific time periods (approximate age ranges): grades 7–8 (12–13 years), grades 9–12 (14–17 years), and the 5 years prior to reference date. For each of the three time periods of interest, participants were asked how many bottles of beer, glasses of wine, and shots of liquor they usually drank, and were given the choice of reporting the frequency per week, per month, or per year. Additional information collected during the interview included demographic characteristics, medical history, physical characteristics, cigarette smoking, recreational drug use, and other known or suspected TGCT risk factors. Prior to the in-person interview, each participant was asked to complete a self-administered questionnaire on family history of cancer.

Non-participant interviews

A subset of 32 cases and 170 controls that declined to participate in the study completed a brief phone survey that included some of the key questions from the main questionnaire, including the frequency of alcoholic drink consumption during the 5 years prior to reference date, in order to evaluate whether there were meaningful differences between men that participated and those that did not.

Statistical analysis

We categorized participants according to their alcohol consumption for each of the three time periods for which alcohol use was assessed. For the time periods corresponding to 5 years prior to reference date and grades 9–12, we categorized alcohol consumption as number of drinks per week (None, 1–6, 7–13, ≥ 14), as well as number of grams of ethanol per day (none, <5, 5–14, ≥ 15). Beverage serving sizes were standardized as 12 ounces per can or bottle of beer, 4 ounces per glass of wine, and 1.5 ounces per shot of liquor. The number of grams of ethanol per alcoholic drink was assigned as 12.8 grams for beer, 11.0 grams for wine, and 14.0 grams for liquor. 18 We also created binary categories of None/Any. Because the prevalence of alcohol consumption during grades 7–8 was low, we limited categorization in this time period to the None/Any binary grouping.

We used unconditional logistic regression to estimate odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals of TGCT associated with categories of alcohol consumption for each of the three lifetime periods for which alcohol use was assessed. We selected potential adjustment variables a priori based on prior knowledge of TGCT risk factors and characteristics associated with consumption of alcohol. Factors that were associated both with TGCT and with alcohol consumption in our data were included in models as covariates. We also included terms for age and reference year in the regression models, because the controls were frequency matched to the cases on these characteristics. We fit two models: one that adjusted for age at reference and reference year (base model), and a second that additionally adjusted for educational attainment (≤high school, college, graduate school), smoking status (never, former, current), and marijuana use (never, former, current <weekly, current weekly+). To evaluate the influence of the time period during which alcoholic beverages were consumed on the risk of TGCT, we cross-classified alcohol consumption (< 1 versus ≥ 1 drink/week) during grades 9–12 (adolescence) by consumption in the 5 years prior to reference date (adulthood) among ATLAS participants >23 years of age. With participants reporting consumption of <1 drink/week in both periods serving as the reference group, we calculated odd ratios for the remaining three groups, allowing us to estimate the relative risk of TGCT for a) “heavier” drinking in adulthood but not during adolescence, b) “heavier” drinking during adolescence but not in adulthood, and c) “heavier” drinking in both time periods. In order to assess the impact of beverage type, we fit separate models for beer, wine, and liquor. Finally, we used polytomous logistic regression to calculate odds ratio estimates separately for seminoma (ICD-O histologies 9060–9064) and nonseminoma (ICD-O histologies 9070, 9071, 9080, 9082–9084, 9065, 9085, 9081, 9101) tumors.16

To evaluate the extent to which reported alcohol consumption by ATLAS controls was comparable to that reported by men in another U.S. population-based sample, we used data from the 1999–2008 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) for men aged 18–34. We compared the observed number of never-drinkers among ATLAS controls aged 18–34 with the expected number based on the age-and race-specific proportions in the NSDUH data.19 Ever-use in NSDUH was defined as ≥ 1 drink versus ≥ 12 alcoholic drinks over the lifetime in ATLAS. Comparisons of frequency of alcohol consumption were not possible due to differences in the way questions were asked in ATLAS and the NSDUH.

RESULTS

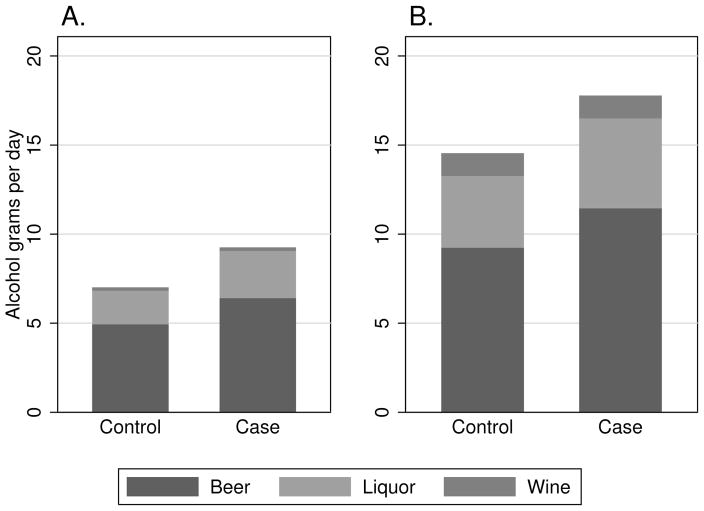

Compared with controls, cases were more often white, were less likely to have received education past high school, and reported lower annual income (Table 1). Cases more frequently reported a history of undescended testes, a family history of TGCT in a first degree relative, and marijuana use that was at least weekly. Among control participants, a higher frequency of consumption of alcoholic drinks in the 5 years previous to reference date was associated with lower educational attainment, lower income, current cigarette smoking, and more frequent marijuana use (Table 2). Similar associations were observed for consumption of alcohol during grades 9–12 (Table 3). During each of the periods for which alcohol use was ascertained, cases reported higher mean alcohol consumption than controls (Figure 1). The proportion of alcohol consumed by beverage type was similar between cases and controls. Beer comprised the largest proportion (64%) of total grams of alcohol consumed by both cases and controls, followed by liquor (28%) and wine (8%).

Table 1.

Selected characteristics of ATLAS TGCT cases and controls, Seattle-Puget Sound region, USA, 1999–2008.

| Controls (n=1,280)

|

Cases (n=490)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | N | % | N | % |

| Reference year | ||||

| 1999–2001 | 475 | 37.1 | 162 | 33.1 |

| 2002–2004 | 373 | 29.1 | 156 | 31.8 |

| 2005–2008 | 432 | 33.8 | 172 | 35.1 |

| Age (years) | ||||

| 18–24 | 180 | 14.1 | 78 | 15.9 |

| 25–29 | 170 | 13.3 | 86 | 17.6 |

| 30–34 | 350 | 27.3 | 123 | 25.1 |

| 35–39 | 302 | 23.6 | 106 | 21.6 |

| 40–44 | 278 | 21.7 | 97 | 19.8 |

| Race/Hispanic ethnicity | ||||

| White non-Hispanic | 998 | 80.0 | 418 | 85.3 |

| African-American non-Hispanic | 42 | 3.3 | 0 | 0 |

| White Hispanic | 35 | 2.7 | 17 | 3.5 |

| Other non-Hispanic | 173 | 13.5 | 44 | 9.0 |

| Other Hispanic | 32 | 2.5 | 11 | 2.2 |

| History of undescended testes | ||||

| No | 1,252 | 97.8 | 440 | 90.5 |

| Yes | 28 | 2.2 | 46 | 9.5 |

| Family history TGCT in 1o relative | ||||

| No | 1135 | 88.7 | 424 | 86.5 |

| Yes | 13 | 1.0 | 12 | 2.5 |

| Unknown† | 132 | 10.3 | 54 | 11.0 |

| Educational attainment | ||||

| High school or less | 305 | 23.8 | 140 | 28.6 |

| College/Trade school | 783 | 61.2 | 294 | 60.9 |

| Graduate school | 192 | 15.0 | 56 | 11.4 |

| Annual household income | ||||

| <$25K | 136 | 10.6 | 70 | 14.3 |

| $25–<50k | 299 | 23.4 | 134 | 27.4 |

| $50–<90k | 504 | 39.4 | 167 | 34.1 |

| $90k+ | 334 | 26.1 | 116 | 23.7 |

| Missing | 7 | 0.6 | 3 | 0.6 |

| Cigarette smoking status | ||||

| Never | 753 | 58.8 | 277 | 56.5 |

| Former | 240 | 18.8 | 93 | 19.0 |

| Current | 287 | 22.4 | 120 | 24.5 |

| Frequency of marijuana use | ||||

| Never | 430 | 33.6 | 141 | 28.8 |

| Former | 603 | 47.2 | 216 | 44.1 |

| Less than weekly | 119 | 9.3 | 55 | 11.2 |

| At least weekly | 127 | 9.9 | 78 | 15.9 |

values shown are column percentages; columns may not add to 100 due to rounding.

Unknown category includes participants that did not know family history (72 controls, 33 cases) and those that did not complete family history questionnaire (60 controls, 21 cases)

Table 2.

Distribution of selected characteristics among ATLAS controls by average total alcohol consumption during the 5 years prior to reference date, Seattle-Puget Sound region, 1999–2008.

| Number alcoholic drinks per week | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic* | None (n=193) | 1–6 (n=680) | 7–13 (n=219) | 14+ (n=188) |

| Age, years | ||||

| 18–24 | 23.8 | 11.5 | 11.9 | 16.0 |

| 25–29 | 15.0 | 11.6 | 13.7 | 17.0 |

| 30–34 | 18.1 | 31.8 | 29.2 | 18.6 |

| 35–39 | 21.2 | 23.5 | 22.8 | 27.1 |

| 40–44 | 21.8 | 21.6 | 22.4 | 21.3 |

| Reference year | ||||

| 1999–2001 | 36.8 | 37.3 | 37.4 | 36.2 |

| 2002–2004 | 28.0 | 29.6 | 25.1 | 33.5 |

| 2005–2008 | 35.2 | 33.1 | 37.4 | 30.3 |

| Birth Cohort | ||||

| 1954–63 | 25.9 | 27.1 | 23.7 | 27.1 |

| 1964–73 | 34.7 | 46.2 | 48.4 | 41.5 |

| 1974–83 | 28.5 | 23.4 | 25.6 | 27.7 |

| 1984–90 | 10.9 | 3.4 | 2.3 | 3.7 |

| Educational attainment | ||||

| High school or less | 25.4 | 20.0 | 19.6 | 41.0 |

| College/Trade school | 59.1 | 63.1 | 63.9 | 53.2 |

| Graduate school | 15.5 | 16.9 | 16.4 | 5.8 |

| Annual household income | ||||

| <$25K | 12.7 | 8.9 | 10.1 | 16.0 |

| $25–<50k | 29.6 | 21.3 | 19.6 | 29.8 |

| $50–<90k | 38.1 | 40.5 | 38.8 | 38.8 |

| $90k+ | 19.6 | 29.4 | 31.5 | 15.4 |

| Race/Hispanic ethnicity | ||||

| White non-Hispanic | 72.0 | 77.1 | 86.3 | 77.7 |

| AA non-Hispanic | 5.2 | 2.6 | 2.3 | 4.8 |

| White Hispanic | 1.5 | 3.2 | 1.8 | 3.2 |

| Other non-Hispanic | 18.7 | 14.6 | 8.2 | 10.6 |

| Other Hispanic | 2.6 | 2.5 | 1.4 | 3.7 |

| Cigarette smoking status | ||||

| Never | 73.6 | 64.4 | 52.5 | 30.8 |

| Former | 12.4 | 18.4 | 24.7 | 19.7 |

| Current | 14.0 | 17.2 | 22.8 | 49.5 |

| Marijuana use | ||||

| Never | 62.2 | 36.8 | 21.1 | 7.4 |

| Former | 29.0 | 49.9 | 54.1 | 47.9 |

| Less than weekly | 2.6 | 7.6 | 14.2 | 16.5 |

| At least weekly | 6.2 | 5.7 | 10.6 | 28.2 |

values shown are column percentages; columns may not add to 100 due to rounding.

Table 3.

Distribution of selected characteristics among ATLAS controls by average total alcohol consumption during the grades 9–12, Seattle-Puget Sound region, 1999–2008.

| Number alcoholic drinks per week | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic* | None (n=778) | 1–6 (n=296) | 7–13 (n=117) | 14+ (n=88) |

| Age, years | ||||

| 18–24 | 15.6 | 8.4 | 13.7 | 20.5 |

| 25–29 | 14.4 | 8.5 | 18.8 | 12.5 |

| 30–34 | 28.5 | 29.1 | 16.2 | 26.1 |

| 35–39 | 22.9 | 25.3 | 26.5 | 19.3 |

| 40–44 | 18.6 | 28.7 | 24.8 | 21.6 |

| Reference year | ||||

| 1999–2001 | 34.7 | 38.5 | 46.1 | 40.9 |

| 2002–2004 | 28.5 | 29.7 | 30.8 | 30.7 |

| 2005–2008 | 36.8 | 31.8 | 23.1 | 28.4 |

| Birth Cohort | ||||

| 1954–63 | 23.4 | 33.8 | 29.9 | 22.7 |

| 1964–73 | 43.3 | 46.6 | 41.9 | 45.5 |

| 1974–83 | 28.2 | 16.6 | 23.9 | 29.5 |

| 1984–90 | 5.1 | 3.0 | 4.3 | 2.3 |

| Education | ||||

| High school or less | 18.6 | 22.0 | 36.8 | 59.1 |

| College/Trade school | 63.5 | 63.8 | 56.4 | 37.5 |

| Graduate school | 17.9 | 14.2 | 6.8 | 3.4 |

| Income | ||||

| <$25K | 9.7 | 5.4 | 18.8 | 26.1 |

| $25–<50k | 22.4 | 21.4 | 31.6 | 28.4 |

| $50–<90k | 39.4 | 44.7 | 35.1 | 30.7 |

| $90k+ | 28.5 | 28.5 | 14.5 | 14.8 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| White non-Hispanic | 77.6 | 82.4 | 75.2 | 69.3 |

| AA non-Hispanic | 4.1 | 1.0 | 3.4 | 3.4 |

| White Hispanic | 2.1 | 2.4 | 6.0 | 5.7 |

| Other non-Hispanic | 13.8 | 12.5 | 11.1 | 18.2 |

| Other Hispanic | 2.4 | 1.7 | 4.3 | 3.4 |

| Smoking Status | ||||

| Never | 71.9 | 48.3 | 28.2 | 20.4 |

| Former | 12.8 | 28.4 | 26.5 | 27.3 |

| Current | 15.3 | 23.3 | 45.3 | 52.3 |

| Marijuana use | ||||

| Never | 48.7 | 12.9 | 5.1 | 8.0 |

| Former | 37.3 | 65.8 | 66.7 | 45.4 |

| Less than weekly | 7.6 | 10.8 | 13.7 | 13.6 |

| At least weekly | 6.4 | 10.5 | 14.5 | 33.0 |

values shown are column percentages; columns may not add to 100 due to rounding.

Figure 1.

Mean alcohol consumption in grams per day among ATLAS participants during high school (Panel A.) and the 5 years prior to reference date (Panel B.), by beverage type.

Relative to non-drinkers, participants who reported consuming any alcoholic drinks during grades 9–12 had a 30% increased risk of TGCT in the fully adjusted model (OR=1.34; 95% CI: 1.05–1.70; Table 4). We observed a increase in TGCT risk associated with greater frequency of alcohol consumption (ptrend=0.05). Compared to abstainers during this period, men who drank 14 or more drinks per week had a risk of TGCT that was 50% higher (OR=1.53; 95% CI: 1.01–2.31). Similar patterns were observed when the data were analyzed as grams of alcohol per day, and for alcohol consumption during the 5 years prior to reference date (Table 4). Odds ratio estimates were attenuated in the fully adjusted model as compared to the base model adjusted for age and reference year, largely due to control for marijuana use. Use of finer categories for marijuana (never, former, current: daily, current: weekly, current: monthly, current: yearly) had no meaningful effect on the adjusted OR estimates, therefore the estimates presented are from models using the more parsimonious classification of marijuana use. When we analyzed the joint association of alcohol consumption during high school (adolescence) and in the 5 years prior to reference date (adulthood) we found no evidence of effect modification on an additive or multiplicative scale (results not shown).

Table 4.

Risk of TGCT associated with average alcohol consumption during different periods, Seattle-Puget Sound region, USA, 1999–2008.

| Alcohol use | No. cases (%) | No. controls* (%) | OR (95% CI)1 | OR (95% CI)2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grades 7–8 | ||||

| None | 407 (83.1) | 1,100 (86.0) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Any | 83 (16.9) | 179 (14.0) | 1.30 (0.97–1.74) | 1.19 (0.87–1.62) |

| Grades 9–12 | ||||

| None | 259 (52.9) | 778 (60.8) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Any | 231 (47.2) | 501 (39.2) | 1.42 (1.15–1.77) | 1.34 (1.05–1.70) |

| None | 259 (52.9) | 778 (60.8) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 1–6 drinks/wk | 134 (27.4) | 296 (23.1) | 1.43 (1.11–1.85) | 1.39 (1.06–1.82) |

| 7–13 drinks/wk | 45 (9.2) | 117 (9.2) | 1.13 (0.77–1.65) | 1.07 (0.72–1.60) |

| 14+ drinks/wk | 52 (10.6) | 88 (6.9) | 1.79 (1.23–2.61) | 1.53 (1.01–2.31) |

| p for trend | 0.002 | 0.05 | ||

| None | 259 (52.9) | 778 (60.8) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| <5 grams/day | 61 (12.5) | 132 (10.3) | 1.47 (1.04–2.08) | 1.41 (0.99–2.02) |

| 5–14 grams/day | 77 (15.7) | 184 (14.4) | 1.32 (0.97–1.79) | 1.29 (0.93–1.79) |

| 15+ grams/day | 93 (19.0) | 185 (14.5) | 1.49 (1.11–2.00) | 1.33 (0.96–1.84) |

| p for trend | 0.003 | 0.05 | ||

| 5 years prior to reference date | ||||

| None | 58 (11.8) | 193 (15.1) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Any | 432 (88.2) | 1,087 (84.9) | 1.34 (0.97–1.85) | 1.25 (0.90–1.75) |

| None | 58 (11.8) | 193 (15.1) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 1–6 drinks/wk | 244 (49.8) | 680 (53.1) | 1.23 (0.88–1.72) | 1.20 (0.85–1.69) |

| 7–13 drinks/wk | 87 (17.8) | 219 (17.1) | 1.31 (0.88–1.94) | 1.23 (0.81–1.85) |

| 14+ drinks/wk | 101 (20.6) | 188 (14.7) | 1.79 (1.21–2.65) | 1.56 (1.03–2.37) |

| p for trend | 0.003 | 0.04 | ||

| None | 58 (11.8) | 193 (15.1) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| <5 grams/day | 137 (28.8) | 431 (33.7) | 1.09 (0.76–1.56) | 1.08 (0.75–1.55) |

| 5–14 grams/day | 125 (25.5) | 297 (23.2) | 1.44 (0.99–2.09) | 1.41 (0.96–2.07) |

| 15+ grams/day | 170 (34.7) | 359 (28.1) | 1.57 (1.10–2.24) | 1.42 (0.97–2.08) |

| p for trend | 0.001 | 0.02 | ||

1 control declined to answer questions regarding alcohol use in grades 7–12

adjusted for age at reference and reference year

adjusted for age at reference, educational attainment (≤high school, college, graduate school), smoking status (never, former, current), and marijuana use (never, former, current <weekly, current weekly+)

TGCT odds ratio estimates were similar when calculated separately for beer, wine, and liquor (data not shown). When stratified by histologic type, alcohol consumption appeared to be more strongly associated with TGCT among men with nonseminomas than seminomas (Table 5), however, these differences were not statistically significant (p>0.10 for all).

Table 5.

Risk of TGCC associated with average alcohol consumption during different periods, by histologic type, Seattle-Puget Sound region, 1999–2008.

| Alcohol use | Seminoma1 | Nonseminoma1 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. controls* (%) | No. cases (%) | OR (95% CI)2 | No. cases (%) | OR (95% CI)2 | |

| Grades 7–8 | |||||

| None | 1,100 (86.0) | 249 (83.6) | 1.00 | 158 (82.3) | 1.00 |

| Any | 179 (14.0) | 49 (16.4) | 1.19 (0.82–1.72) | 34 (17.7) | 1.27 (0.81–2.00) |

| Grades 9–12 | |||||

| None | 778 (60.8) | 163 (54.7) | 1.00 | 96 (50.0) | 1.00 |

| Any | 501 (39.2) | 135 (45.3) | 1.20 (0.90–1.60) | 96 (50.0) | 1.63 (1.13–2.34) |

| None | 778 (60.8) | 163 (54.7) | 1.00 | 96 (50.0) | 1.00 |

| 1–6 drinks/wk | 296 (23.1) | 83 (27.9) | 1.25 (0.91–1.73) | 51 (26.6) | 1.67 (1.10–2.53) |

| 7–13 drinks/wk | 117 (9.2) | 26 (8.7) | 1.00 (0.61–1.64) | 19 (9.9) | 1.20 (0.67–2.16) |

| 14+ drinks/wk | 88 (6.9) | 26 (8.7) | 1.27 (0.76–2.14) | 26 (13.5) | 2.11 (1.19–3.73) |

| p for trend | 0.37 | 0.02 | |||

| None | 778 (60.8) | 163 (54.7) | 1.00 | 96 (50.0) | 1.00 |

| <5 grams/day | 132 (10.3) | 37 (12.4) | 1.30 (0.85–1.98) | 24 (12.5) | 1.63 (0.95–2.79) |

| 5–14 grams/day | 184 (14.4) | 48 (16.1) | 1.15 (0.78–1.70) | 29 (15.1) | 1.57 (0.95–2.60) |

| 15+ grams/day | 185 (14.5) | 50 (16.8) | 1.18 (0.79–1.75) | 43 (22.4) | 1.67 (1.05–2.65) |

| p for trend | 0.35 | 0.02 | |||

| 5 years prior to reference date | |||||

| None | 193 (15.1) | 37 (12.4) | 1.00 | 21 (10.9) | 1.00 |

| Any | 1,087 (84.9) | 261 (87.6) | 1.11 (0.75–1.65) | 171 (89.1) | 1.52 (0.89–2.59) |

| None | 193 (15.1) | 37 (12.4) | 1.00 | 21 (10.9) | 1.00 |

| 1–6 drinks/wk | 680 (53.1) | 153 (51.3) | 1.07 (0.71–1.61) | 91 (47.4) | 1.43 (0.83–2.46) |

| 7–13 drinks/wk | 219 (17.1) | 54 (18.1) | 1.10 (0.68–1.79) | 33 (17.2) | 1.47 (0.77–2.82) |

| 14+ drinks/wk | 188 (14.7) | 54 (18.1) | 1.31 (0.79–2.16) | 47 (24.5) | 2.12 (1.11–4.03) |

| p for trend | 0.28 | 0.03 | |||

| None | 193 (15.1) | 37 (12.4) | 1.00 | 21 (10.9) | 1.00 |

| <5 grams/day | 431 (33.7) | 83 (27.9) | 0.94 (0.61–1.46) | 54 (28.1) | 1.35 (0.76–2.38) |

| 5–14 grams/day | 297 (23.2) | 85 (28.5) | 1.32 (0.84–2.07) | 40 (20.8) | 1.50 (0.81–2.80) |

| 15+ grams/day | 359 (28.1) | 93 (31.2) | 1.20 (0.76–1.88) | 77 (40.1) | 1.90 (1.05–3.44) |

| p for trend | 0.17 | 0.03 | |||

1 control declined to answer questions regarding alcohol use in grades 7–12

test for interaction by histologic type p-value > 0.05 for all

adjusted for age at reference, reference year, educational attainment (≤high school, college, graduate school), smoking status (never, former, current), and marijuana use (never, former, current <weekly, current weekly+)

Surveyed non-participating cases and controls were of similar ages to cases and controls who participated in the study, but non-participating cases and controls both had lower levels of educational attainment than those who participated. Among controls, 24% of non-participants versus 32% of participants had completed high school or less, and among cases the corresponding values were 29% versus 57%. The proportion of moderate (7–13 drinks/week) and heavy (≥ 14 drinks/week) drinking reported in the 5 years prior to reference date among surveyed non-participating controls (7% and 3%, respectively) was lower than that of participating controls (17% and 15%, respectively). The corresponding proportions for non-participating (19% and 16% for moderate and heavy drinking, respectively) and participating cases (19% and 21% for moderate and heavy drinking, respectively) were similar. The proportion of never-drinkers was similar among ATLAS controls and NSDUH respondents (O/E ratio: 0.96; 95% CI: 0.89–1.04)

DISCUSSION

In this population-based study, we observed an increase in the risk of TGCT associated with greater consumption of alcoholic beverages during adolescence and adulthood. Compared with non-drinkers, men who consumed 14+ drinks per week during high school or during the 5 years prior to reference date had an approximately 50% increased risk of TGCT after accounting for potential confounding factors. The risk of TGCT associated with alcohol did not vary appreciably by beverage type, but appeared stronger for nonseminoma or mixed histology tumors as opposed to seminomas.

Previous studies of TGCT have not provided clear evidence of an association with adult consumption of alcoholic beverages. In a U.K. case-control study (259 cases, 489 controls) men who reported regular consumption of wine had an increased risk of TGCT (OR=1.7; 95% CI: 1.21–2.43), but there was no dose-response relationship or association with regular consumption of beer, cider, or liquor.9 In three other TGCT case-control studies that collectively included 1,558 cases and 1,860 controls, there were no associations with alcohol consumption.11 Two cohort studies of persons with a history of heavy alcohol consumption (manifested as diagnoses of liver cirrhosis and alcoholism) gave conflicting results, with an increased TGCT risk relative to the general population in one study, but not the other.10,12

A number of limitations of the present study should be noted. The proportion of eligible cases and controls who participated in the study was relatively low (68% and 51%, respectively). Low participation could have led to our results if alcohol consumption was higher among non-participating controls than participating controls (and not so for cases), or if alcohol consumption was lower among non-participating cases than participating cases (and not so for controls). However, to the extent that surveyed non-participants were representative of all non-participants, our data suggest that any bias introduced by low participation would have dampened a true association, rather than caused a spurious association.

In addition, uncontrolled confounding may partly explain the results. Marijuana use has been associated with TGCT in 3 previous studies,14,17,20 including one in this same population,17 and is also associated with alcohol use in the ATLAS population. Although we adjusted for marijuana use, residual confounding may be present due to errors in measuring this characteristic. It is noteworthy that OR estimates for both alcohol and marijuana use were similarly attenuated in models that included variables for both, suggesting that both may be independently associated with TGCT, and each may confound the other. Additionally, adjustment for marijuana use in finer categories had no appreciable effect on the OR estimates for alcohol consumption. Higher levels of alcohol use may also be associated with other dietary or behavioral characteristics that are causally related to TGCT.

We relied on self-report of alcohol consumption, and due to social desirability bias, controls may have been more likely to underestimate alcohol consumption than cases. However, it has been demonstrated that compared to prospectively collected data prior to diagnosis, retrospective reports of alcohol intake in a case-control study may have only minor effects on alcohol reporting and risk estimates.21 Moreover, the proportion of never-drinkers among our controls was very comparable to that from a national sample, suggesting that our controls are not unusual in their alcohol use history.

Each of our measures of alcohol consumption is subject to measurement error which may have resulted in misclassification of the total amount of ethanol consumed. The drinks/day measure does not account for differences in ethanol contact by beverage type, and is therefore an imperfect estimate of the amount of ethanol consumed. The grams/day measure attempts to more accurately estimate ethanol intake, however it relies on assumptions about the ethanol content of specific beverages and on accurate reporting of beverage types by participants. Both methods of quantifying alcohol consumption assume average serving sizes, which may also contribute to exposure misclassification. If these various sources of measurement error are the same for cases and controls, then misclassification of exposure would be non-differential, resulting in a dampening of the odds ratio estimates. Participants’ reporting of drinking during their teenage years may be particularly subject to errors as underage drinking is illegal in the United States and adolescence is a time during which behaviors can vary greatly from year to year. It is also possible that aspects of alcohol use other than those we examined are more strongly related to TGCT risk. These could include lifetime cumulative alcohol consumption, duration of use or drinking patterns, none of which could be assessed with the data collected. Quantity versus frequency of alcohol consumption, in particular, may have differential associations with cancer than more global measures of alcohol consumption.22 In Washington State (and nationally), occasions of heavy quantity or “binge” drinking are common among young men, including high-school students, and may be particularly important aspects of exposure.23–25

Alcohol is an established human carcinogen at multiple anatomical sites, although the mechanisms are not fully understood, and likely vary by organ.26 Proposed mechanisms of alcohol carcinogenesis include DNA damage by the ethanol metabolite acetaldehyde, production of reactive oxygen species leading to oxidative stress, increased activation and delayed clearance of carcinogens, reduction of immune surveillance, induction of nutritional deficiencies, alterations in folate metabolism, and alterations in steroid hormone levels.26 Given the well-documented negative effects of alcohol consumption on testicular structure and function,6–8 it is plausible that one or more of these mechanisms could contribute to TGCT etiology.

The prevailing model for TGCT pathogenesis hypothesizes that testicular neoplasms originate in utero, but evidence from a number of sources suggests that postnatal factors may also be important. Associations have been reported between TGCT risk and postnatal characteristics such as later age of puberty,27 severe acne 28,29 male pattern baldness,28–30 occupational exposures,31 and marijuana use.14,17,20 Based on a comparison of trends in adult (20–24 years) versus childhood (0–4 years) TGCT in 8 populations, the incidence of adult TGCT doubled over 20 years, with no substantial increase in the incidence of childhood TGCT during the same time period.32 Age-period-cohort models of TGCT incidence demonstrate robust calendar period deviation, adding additional support for the role of postnatal exposures in the etiology of these tumors.32

In summary, our results suggest that consumption of alcohol during adolescence and adulthood is associated with a greater risk of TGCT. Additional studies of alcohol consumption and TGCT incidence are warranted, particularly studies which collect detailed data on lifetime patterns of consumption. If the results of the present analysis are confirmed in other studies, alcohol consumption would be an important modifiable risk factor for TGCT.

Novelty and impact.

Little is known about modifiable risk factors for testicular germ cell tumor (TCGT). In this study, the authors analyzed the association between consumption of alcoholic beverages in adolescence and adulthood and the risk of TGCT. Men who drank ≥14 drinks per week during high school (ages 14–17 years), or during the past 5 years, had an approximately 50% increased risk of developing TGCT. This association appeared to be stronger for nonseminoma versus seminoma tumors.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants and contracts from U.S. National Cancer Institute (R01CA085914; N01PC067009; N01PC35142; T32ES007262) and institutional resources provided by the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center.

Abbreviations

- TGCT

testicular germ cell tumor

- OR

odds ratio

- CIs

confidence intervals

- ATLAS

Adult Testicular Lifestyle and Blood Specimen

- NSDUH

National Survey on Drug Use and Health

- O/E

Observed/Expected

References

- 1.Chia VM, Quraishi SM, Devesa SS, Purdue MP, Cook MB, McGlynn KA. International trends in the incidence of testicular cancer, 1973–2002. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19(5):1151–1159. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Trabert B, Chen J, Devesa SS, Bray F, McGlynn KA. International patterns and trends in testicular cancer incidence, overall and by histologic subtype, 1973–2007. Andrology. 2015;3(1):4–12. doi: 10.1111/andr.293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McGlynn KA, Devesa SS, Sigurdson AJ, Brown LM, Tsao L, Tarone RE. Trends in the incidence of testicular germ cell tumors in the United States. Cancer. 2003;97(1):63–70. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ekbom A, Akre O. Increasing incidence of testicular cancer--birth cohort effects. APMIS. 1998;106(1):225–229. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1998.tb01340.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baan R, Straif K, Grosse Y, et al. Carcinogenicity of alcoholic beverages. Lancet Oncol. 2007;8(4):292–293. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(07)70099-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Green GR. Mechanism of hypogonadism in cirrhotic males. Gut. 1977;18(10):843–853. doi: 10.1136/gut.18.10.843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bannister P, Losowsky MS. Ethanol and hypogonadism. Alcohol Alcohol. 1987;22(3):213–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vatsalya V, Issa JE, Hommer DW, Ramchandani VA. Pharmacodynamic effects of intravenous alcohol on hepatic and gonadal hormones: influence of age and sex. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2012;36(2):207–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01600.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Swerdlow AJ, Huttly SR, Smith PG. Testis cancer: post-natal hormonal factors, sexual behaviour and fertility. Int J Cancer. 1989;43(4):549–553. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910430403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adami HO, McLaughlin JK, Hsing AW, et al. Alcoholism and cancer risk: a population-based cohort study. Cancer Causes Control. 1992;3(5):419–425. doi: 10.1007/BF00051354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Social, behavioural and medical factors in the aetiology of testicular cancer: results from the UK study. UK Testicular Cancer Study Group. Br J Cancer. 1994;70(3):513–520. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1994.337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sorensen HT, Friis S, Olsen JH, et al. Risk of liver and other types of cancer in patients with cirrhosis: a nationwide cohort study in Denmark. Hepatology. 1998;28(4):921–925. doi: 10.1002/hep.510280404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garner MJ, Birkett NJ, Johnson KC, et al. Dietary risk factors for testicular carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2003;106(6):934–941. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lacson JC, Carroll JD, Tuazon E, Castelao EJ, Bernstein L, Cortessis VK. Population-based case-control study of recreational drug use and testis cancer risk confirms an association between marijuana use and nonseminoma risk. Cancer. 2012;118(21):5374–5383. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Richiardi L, Pettersson A, Akre O. Genetic and environmental risk factors for testicular cancer. Int J Androl. 2007;30(4):230–240. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.2007.00760.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.International Calssification of Diseases for Oncology. 3. World Health Organization; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Daling JR, Doody DR, Sun X, et al. Association of marijuana use and the incidence of testicular germ cell tumors. Cancer. 2009;115(6):1215–1223. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.U.S Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service. USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference, Release 15. Nutrient Data Laboratory Home Page. 2002 http://www.ars.usda.gov/ba/bhnrc/ndl.

- 19.Liddell FD. Simple exact analysis of the standardised mortality ratio. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1984;38(1):85–88. doi: 10.1136/jech.38.1.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Trabert B, Sigurdson AJ, Sweeney AM, Strom SS, McGlynn KA. Marijuana use and testicular germ cell tumors. Cancer. 2011;117(4):848–853. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Giovannucci E, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, et al. Recall and selection bias in reporting past alcohol consumption among breast cancer cases. Cancer Causes Control. 1993;4(5):441–448. doi: 10.1007/BF00050863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Breslow RA, Chen CM, Graubard BI, Mukamal KJ. Prospective study of alcohol consumption quantity and frequency and cancer-specific mortality in the US population. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;174(9):1044–1053. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Washington 2006 Calculated Variables Report. [Accessed October 19, 2014];Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, March 2, 2007. 2014 Available at: http://www.doh.wa.gov/Portals/1/Documents/5300/BRFSSWA06CALC.pdf.

- 24.Washington State Healthy Youth Survey 2006 Analytic Report. Washington State Department of Health, Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction, Department of Social and Health Services, Department of Community, Trade and Economic Development, and Family Policy Council; Jun, 2007. [Accessed 10-19-2014]. Available at: http://www.doh.wa.gov/Portals/1/Documents/1200/EP1-3-1doh1.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Vital signs: binge drinking among high school students and adults --- United States, 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59(39):1274–1279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boffetta P, Hashibe M. Alcohol and cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7(2):149–156. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70577-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maule M, Malavassi JL, Richiardi L. Age at puberty and risk of testicular cancer: a meta-analysis. Int J Androl. 2012;35(6):828–834. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.2012.01286.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Depue RH, Pike MC, Henderson BE. Estrogen exposure during gestation and risk of testicular cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1983;71(6):1151–1155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Trabert B, Sigurdson AJ, Sweeney AM, Amato RJ, Strom SS, McGlynn KA. Baldness, acne and testicular germ cell tumours. Int J Androl. 2011;34(4 Pt 2):e59–e67. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.2010.01125.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Petridou E, Roukas KI, Dessypris N, et al. Baldness and other correlates of sex hormones in relation to testicular cancer. Int J Cancer. 1997;71(6):982–985. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19970611)71:6<982::aid-ijc13>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McGlynn KA, Trabert B. Adolescent and adult risk factors for testicular cancer. Nat Rev Urol. 2012;9(6):339–349. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2012.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lacerda HM, Akre O, Merletti F, Richiardi L. Time trends in the incidence of testicular cancer in childhood and young adulthood. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18(7):2042–2045. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]