Abstract

Background

One target of the Sustainable Development Goals is to achieve "universal health coverage, including financial risk protection, access to quality essential health‐care services and access to safe, effective, quality and affordable essential medicines and vaccines for all". A fundamental concern of governments in striving for this goal is how to finance such a health system. This concern is very relevant for low‐income countries.

Objectives

To provide an overview of the evidence from up‐to‐date systematic reviews about the effects of financial arrangements for health systems in low‐income countries. Secondary objectives include identifying needs and priorities for future evaluations and systematic reviews on financial arrangements, and informing refinements in the framework for financial arrangements presented in the overview.

Methods

We searched Health Systems Evidence in November 2010 and PDQ‐Evidence up to 17 December 2016 for systematic reviews. We did not apply any date, language, or publication status limitations in the searches. We included well‐conducted systematic reviews of studies that assessed the effects of financial arrangements on patient outcomes (health and health behaviours), the quality or utilisation of healthcare services, resource use, healthcare provider outcomes (such as sick leave), or social outcomes (such as poverty, employment, or financial burden of patients, e.g. out‐of‐pocket payment, catastrophic disease expenditure) and that were published after April 2005. We excluded reviews with limitations important enough to compromise the reliability of the findings. Two overview authors independently screened reviews, extracted data, and assessed the certainty of evidence using GRADE. We prepared SUPPORT Summaries for eligible reviews, including key messages, 'Summary of findings' tables (using GRADE to assess the certainty of the evidence), and assessments of the relevance of findings to low‐income countries.

Main results

We identified 7272 reviews and included 15 in this overview, on: collection of funds (2 reviews), insurance schemes (1 review), purchasing of services (1 review), recipient incentives (6 reviews), and provider incentives (5 reviews). The reviews were published between 2008 and 2015; focused on 13 subcategories; and reported results from 276 studies: 115 (42%) randomised trials, 11 (4%) non‐randomised trials, 23 (8%) controlled before‐after studies, 51 (19%) interrupted time series, 9 (3%) repeated measures, and 67 (24%) other non‐randomised studies. Forty‐three per cent (119/276) of the studies included in the reviews took place in low‐ and middle‐income countries.

Collection of funds: the effects of changes in user fees on utilisation and equity are uncertain (very low‐certainty evidence). It is also uncertain whether aid delivered under the Paris Principles (ownership, alignment, harmonisation, managing for results, and mutual accountability) improves health outcomes compared to aid delivered without conforming to those principles (very low‐certainty evidence).

Insurance schemes: community‐based health insurance may increase service utilisation (low‐certainty evidence), but the effects on health outcomes are uncertain (very low‐certainty evidence). It is uncertain whether social health insurance improves utilisation of health services or health outcomes (very low‐certainty evidence).

Purchasing of services: it is uncertain whether increasing salaries of public sector healthcare workers improves the quantity or quality of their work (very low‐certainty evidence).

Recipient incentives: recipient incentives may improve adherence to long‐term treatments (low‐certainty evidence), but it is uncertain whether they improve patient outcomes. One‐time recipient incentives probably improve patient return for start or continuation of treatment (moderate‐certainty evidence) and may improve return for tuberculosis test readings (low‐certainty evidence). However, incentives may not improve completion of tuberculosis prophylaxis, and it is uncertain whether they improve completion of treatment for active tuberculosis. Conditional cash transfer programmes probably lead to an increase in service utilisation (moderate‐certainty evidence), but their effects on health outcomes are uncertain. Vouchers may improve health service utilisation (low‐certainty evidence), but the effects on health outcomes are uncertain (very low‐certainty evidence). Introducing a restrictive cap may decrease use of medicines for symptomatic conditions and overall use of medicines, may decrease insurers' expenditures on medicines (low‐certainty evidence), and has uncertain effects on emergency department use, hospitalisations, and use of outpatient care (very low‐certainty evidence). Reference pricing, maximum pricing, and index pricing for drugs have mixed effects on drug expenditures by patients and insurers as well as the use of brand and generic drugs.

Provider incentives: the effects of provider incentives are uncertain (very low‐certainty evidence), including: the effects of provider incentives on the quality of care provided by primary care physicians or outpatient referrals from primary to secondary care, incentives for recruiting and retaining health professionals to serve in remote areas, and the effects of pay‐for‐performance on provider performance, the utilisation of services, patient outcomes, or resource use in low‐income countries.

Authors' conclusions

Research based on sound systematic review methods has evaluated numerous financial arrangements relevant to low‐income countries, targeting different levels of the health systems and assessing diverse outcomes. However, included reviews rarely reported social outcomes, resource use, equity impacts, or undesirable effects. We also identified gaps in primary research because of uncertainty about applicability of the evidence to low‐income countries. Financial arrangements for which the effects are uncertain include external funding (aid), caps and co‐payments, pay‐for‐performance, and provider incentives. Further studies evaluating the effects of these arrangements are needed in low‐income countries. Systematic reviews should include all outcomes that are relevant to decision‐makers and to people affected by changes in financial arrangements.

Plain language summary

Financial arrangements for health systems in low‐income countries

What is the aim of this overview?

The aim of this Cochrane Overview is to provide a broad summary of what is known about the effects of financial arrangements for health systems in low‐income countries.

This overview is based on 15 systematic reviews. Each of these systematic reviews searched for studies that evaluated different types of financial arrangements within the scope of the review question. The reviews included a total of 276 studies.

This overview is one of a series of four Cochrane Overviews that evaluate different health system arrangements.

Main results

What are the effects of different ways of collecting funds to pay for health services? Two reviews looked for studies that addressed this question and found the following.

‐ The effects of changes in user fees on utilisation and equity are uncertain (very low‐certainty evidence).

‐ It is uncertain whether aid delivered under Paris Principles (ownership, alignment, harmonisation, managing for results, and mutual accountability) improves health compared to aid delivered without conforming to those principles (very low‐certainty evidence).

What are the effects of different types of insurance schemes? One systematic review looked for studies that addressed this question and found the following.

‐ Community‐based health insurance may increase people's use of services (low‐certainty evidence), but the effects on people's health are uncertain. It is uncertain whether social health insurance increases people's use of services (very low‐certainty evidence).

What are the effects of different ways of paying for health services? One systematic review looked for studies that addressed this question and found the following.

‐ It is uncertain whether increasing salaries of public sector healthcare workers improves the quantity or quality of their work.

What are the effects of different types of financial incentives for recipients of care? Six systematic reviews looked for studies that addressed this question and found the following.

‐ Giving healthcare recipients incentives may improve their adherence to long‐term treatments (low‐certainty evidence), but it is uncertain whether they improve people's health.

‐ Giving healthcare recipients one‐time incentives probably leads more people to return to start or continue treatment for tuberculosis (moderate‐certainty evidence). The certainty of the evidence for other types of recipient incentives for tuberculosis is low or very low.

‐ Conditional cash transfer programmes (giving money to recipients of care on the condition that they take a specified action to improve their health) probably increase people's use of services (moderate‐certainty evidence), but have mixed effect on people's health.

‐ Vouchers may improve people's use of health services (low‐certainty evidence) but have mixed effects on people's health (low‐certainty evidence).

‐ A combination of a ceiling and co‐insurance probably slightly decreases the overall use of medicines (moderate‐certainty evidence) and may increase health service utilisation (low‐certainty evidence). The certainty of the evidence for the effects of other combinations of caps, co‐insurance, co‐payments, and ceilings is low or very low.

‐ Limits on how much insurers pay for different groups of drugs (reference pricing, maximum pricing, and index pricing) have mixed effects on drug expenditures by patients and insurers as well as the use of brand and generic drugs.

What are the effects of different types of financial incentives for health workers? Five systematic reviews looked for studies that addressed this question and found the following.

‐ We are uncertain whether pay‐for‐performance improves health worker performance, people's use of services, people's health, or resource use in low‐income countries (very low‐certainty evidence).

‐ We are uncertain whether financial incentives for health workers improve the quality of care provided by primary care physicians or outpatient referrals from primary to secondary care (very low‐certainty evidence).

‐ There is no rigorous research evaluating incentives (e.g. bursaries or scholarships linked to future practice location, rural allowances) for recruiting health workers to serve in remote areas. It is uncertain whether giving health workers incentives lead more of them to stay in underserved areas (very low‐certainty evidence).

‐ No studies assessed the effects of financial interventions on the movement of health workers between public and private organisations in low‐ and middle‐income countries.

How up to date is this overview?

The overview authors searched for systematic reviews published up to 17 December 2016.

Background

This is one of four overviews of systematic reviews on evidence‐based approaches for refining health systems in low‐income countries (Ciapponi 2014; Herrera 2014; Pantoja 2014). The purpose is to provide comprehensive outlines of evidence on the effects of health system arrangements, including delivery, financial, and governance arrangements as well as implementation strategies.

The scope of each of the four overviews is summarised below.

Financial arrangements comprise variations in how funds are collected, insurance schemes, how services are purchased, and the use of targeted financial incentives or disincentives. This overview discusses financial arrangements.

Delivery arrangements include changes in who receives care and when, who provides care, the working conditions of those who provide care, coordination of care amongst different providers, where care is provided, the use of information and communication technology to deliver care, and quality and safety systems (Ciapponi 2014).

Governance arrangements include changes in rules or processes that determine authority and accountability for health policies, organisations, commercial products and health professionals, and the involvement of stakeholders in decision making (Herrera 2014).

Implementation strategies include interventions designed to bring about changes in healthcare organisations, the behaviour of healthcare professionals, or the use of health services by healthcare recipients (Pantoja 2014).

In 2005 the member states of the World Health Organization (WHO) adopted a resolution encouraging countries to develop health financing systems aimed at providing universal coverage (WHO 2005). Global support for universal health coverage gathered momentum, with the unanimous adoption of a resolution in the United Nations General Assembly that emphasises health as an essential element of international development. The resolution, adopted in 2012, "[c]alls upon Member States to ensure that health financing systems evolve so as to avoid significant direct payments at the point of delivery and include a method for prepayment of financial contributions for health care and services as well as a mechanism to pool risks among the population in order to avoid catastrophic health‐care expenditure and impoverishment of individuals as a result of seeking the care needed" (UN 2012). Global support for universal health coverage received further support in 2015 in the Sustainable Development Goals, which include the following target: "achieve universal health coverage, including financial risk protection, access to quality essential healthcare services and access to safe, effective, quality and affordable essential medicines and vaccines for all" (WHO 2015). A fundamental question that governments face in striving for this goal is how to finance such a health system (WHO 2010a).

A good health system should raise adequate funds for health in ways that ensure people can use needed services and are protected from financial hardships associated with having to pay for health services (WHO 2007). Arrangements for financing health systems include three interrelated functions: collection or acquisition of funds, pooling of prepaid funds in ways that allow risks to be shared (i.e. insurance schemes), and allocation of resources (i.e. purchasing or paying for services) (Murray 2000; WHO 2000; Kutzin 2001; WHO 2007; Van Olmen 2010).

Financial arrangements can potentially affect patient outcomes (health and health behaviours), the quality or utilisation of healthcare services, resource use, healthcare provider outcomes (such as sick leave), and social outcomes (such as poverty or employment) (EPOC 2017). Impacts on these outcomes can be intended and desirable or unintended and undesirable. In addition, the effects of financial arrangements on these outcomes can either reduce or increase inequities.

Health systems in low‐income countries differ from those in high‐income countries in terms of the availability of resources and access to services. Thus, problems related to financial arrangements in low‐income countries can be substantially different from those in high‐income countries. Our focus in this overview is specifically on financial arrangements in low‐income countries. By low‐income countries we mean countries that the World Bank classifies as low‐ or lower‐middle‐income (World Bank 2016). Because upper‐middle‐income countries often have a mixture of health systems with problems similar to both those in low‐income countries and high‐income countries, our focus is relevant to middle‐income countries but excludes consideration of conditions that are not relevant in low‐income countries and are relevant in middle‐income countries.

Description of the interventions

We outline our framework for financial arrangements in Table 1, including five categories of financial arrangements and their definitions. This framework was prepared by modifying the taxonomy for health systems arrangements developed by Lavis and colleagues (Lavis 2015). That framework was developed based on reviewing system‐wide frameworks, such as the WHO health system building blocks, and domain specific schemes, such as those related to human resources policy, pharmaceutical policy, and implementation strategies. Although this framework has fewer main categories than the WHO framework, the contents of the building blocks that are not included (human resources, information, and medical products and technologies) are included in the four categories used in the Lavis framework. We found that the Lavis framework was more parsimonious, while at the same time more detailed and comprehensive. We adjusted the framework iteratively to ensure that all of the included reviews were appropriately categorised and that all relevant financial arrangements were included and organised logically. A short description of the categories of financial arrangements follows.

1. Types of financial arrangements.

| Financial arrangement | Definition |

| Collection of funds | |

| User fees | Charges levied on any aspect of health services at the point of delivery |

| Prepaid funding | Collection of funds through general tax revenues versus earmarked tax revenues versus employer payments versus direct payments |

| Community loan funds | Funds generated from contributions of community members that families can borrow to pay for emergency transportation and hospital costs |

| Health savings accounts | Prepayment schemes for individuals or families without risk pooling |

| External funding | Financial contributions such as donations, loans, etc. from public or private entities from outside the national or local health financing system |

| Insurance schemes (pooling of funds) | |

| Social health insurance | Compulsory insurance that aims to provide universal coverage |

| Community‐based health insurance | A scheme managed and operated by an organisation, other than a government or private for‐profit company, that provides risk pooling to cover all or part of the costs of health care services |

| Private health insurance | Private for‐profit health insurance |

| Purchasing of services | |

| Funding of health service organisations | Fee‐for‐service versus capitation versus prospective payment versus line item budgets versus global budgets versus case‐based reimbursement (including diagnostic related group payment schemes) versus mixed methods of paying for health service organisations |

| Payment methods for health workers | Fee for service versus capitation versus salary versus mixed methods of paying health workers |

| Financial incentives for recipients of care | |

| Financial incentives for recipients of care | Financial or monetary incentives or removal of disincentives to change specified behaviours of recipients of care |

| Conditional cash transfers | Monetary transfers to households on the condition that they comply with pre‐defined requirements |

| Voucher schemes | Provision of vouchers that can be redeemed for health services at specified facilities |

| Caps and co‐payments | Direct patient payments for part of the cost of drugs or health services |

| Financial incentives for providers of care | |

| Pay‐for‐performance | Transfer of money or material goods to healthcare providers conditional on taking a measurable action or achieving a predetermined performance target |

| Budgets | Funds that are allocated by payers to a group or individual physicians to purchase services (including fund holding and indicative budgets) |

| Incentives to practice in underserved areas | Financial or material rewards for practicing in underserved areas |

| Incentives for career choices | Financial or material rewards for career choices; for example, choice of profession or primary care |

Collection of funds

Funds can be collected through five basic mechanisms: user fees or out‐of‐pocket payments, prepaid funding or financing of insurance (voluntary insurance rated by income, voluntary insurance rated by risk, compulsory insurance, general taxes, and earmarked taxes), community loan funds, health savings accounts, and external funding from public or private external sources such as non‐governmental organisations (NGOs) and donor agencies (Murray 2000; Ravishankar 2009). Policymakers have an obligation to decide what combination of these options to use to collect funds, including the extent to which users should pay fees at the point of delivery.

Insurance schemes

There are three principal types of prepaid funding or health insurance schemes, in addition to health care that is paid for via general taxation: social health insurance, community‐based health insurance, and private for‐profit health insurance. Social health insurance schemes are compulsory. Coverage is usually on a national scale but may vary from a specific large group (for example, formal sector employees) to the whole population of a country (Lagarde 2006). Social insurance is usually funded through payroll contributions from employers and or employees, but governments may also contribute (through tax revenue) to cover the poor or unemployed (Carrin 2002; Carrin 2004; Lagarde 2006; Wiysonge 2012). Community‐based health insurance schemes, in contrast to social health insurance, are voluntary (Ekman 2004; Lagarde 2006). They are managed and operated by an organisation other than a government or private for‐profit company. They can cover all or part of the costs of healthcare services (Adebayo 2015). Private for‐profit health insurance works with employer‐based or individual purchase of private insurance plans provided by private companies that compete on a market scheme. The degree of regulation of insurance schemes varies from one country to another, and companies cover part or all the costs of healthcare services depending on the characteristics of the purchased plan or package of services and – where permitted – according to the person's risk profile (Schieber 2006). In addition to deciding what combination of health insurance schemes to use, policymakers must make decisions about the extent to which there are separate insurance schemes for different population groups and the extent to which there is choice and competition among insurance schemes. They must also make decisions about the governance of health insurance schemes, including regulation of private health insurance and regulations regarding who and what is covered (Drechsler 2005).

Purchasing of services

Key decisions that policymakers need to make about arrangements for purchasing services are how to fund service organisations (via fee‐for‐service, capitation, prospective payment, line item budgets, global budgets, case‐based reimbursement, or a combination of these) and how to pay healthcare workers (via fee‐for‐service, capitation, salary, or a combination of these).

Financial incentives for providers of health care

Policymakers also need to consider a range of targeted financial incentives that are intended to motivate specific behaviours. Incentives targeted at providers include pay‐for‐performance, budgets that reward providers for savings or penalise them for overspending, and incentives to practice in underserved areas or to select careers where there is a shortage of health professionals.

Financial incentives for recipients of health care

Incentives for recipients of care include financial incentives for specific types of behaviour (such as preventive behaviours), voucher schemes, and caps or co‐payments for drugs or services that are covered by health insurance.

How the intervention might work

Variations in financial arrangements may influence health and related goals by affecting access to care (e.g. by increasing the availability of resources and services), utilisation of care (e.g. by removing financial disincentives), quality of care (e.g. by paying for performance), equity (e.g. through progressive insurance fees or using tax revenues to pay for services for disadvantaged populations), and efficiency (e.g. by having higher co‐payments for services that are less cost‐effective, thereby deterring use of less cost‐effective services). However, as with any healthcare intervention, financial arrangements can have undesirable effects, and the desirable effects and savings of any option must be weighed against any undesirable effects and costs.

Why it is important to do this overview

Our aim was to provide a broad overview of evidence from available systematic reviews about the effects of alternative financial arrangements for health systems in low‐income countries. Such a broad outline can help policymakers, their support staff, and relevant stakeholders to identify strategies for addressing problems and improving the financing of their health systems. This overview of the findings of systematic reviews also helps to identify needs and priorities for evaluations of alternative financial arrangements, as well as priorities for systematic reviews on the effects of financial arrangements. The overview also helps to refine the framework outlined in Table 1 for considering alternative arrangements for financing health systems.

Changes in health systems are complex and may be difficult to evaluate. The applicability of the findings of evaluations from one setting to another may be uncertain, and synthesising the findings of evaluations may be difficult. However, the alternative to well‐designed evaluations is poorly designed evaluations; the alternative to systematic reviews is non‐systematic reviews; and the alternative to using the findings of systematic reviews to inform decisions is using non‐systematic reviews to inform decisions.

Other types of information, including context‐specific information and judgments (such as judgments about the applicability of the findings of systematic reviews in a specific context), are still needed. Nonetheless, this overview can help people making decisions about financial arrangements by summarising the findings of available systematic reviews (including estimates of the effects of changes in financial arrangements and the certainty of those estimates), identifying important uncertainties reported by those systematic reviews, and identifying areas for new or updated systematic reviews. The overview can also help to inform judgments about the relevance of the available evidence in a specific context (Rosenbaum 2011).

Objectives

To provide an overview of the evidence from up‐to‐date systematic reviews about the effects of financial arrangements for health systems in low‐income countries. Secondary objectives include identifying needs and priorities for future evaluations and systematic reviews on financial arrangements, and informing refinements in the framework for financial arrangements presented in the overview (Table 1).

Methods

We used the methods described below in all four overviews of health system arrangements and implementation strategies in low‐income countries (Ciapponi 2014; Herrera 2014; Pantoja 2014).

Criteria for considering reviews for inclusion

We included systematic reviews that:

had a Methods section with explicit selection criteria;

assessed the effects of financial arrangements (as defined in Background);

reported at least one of the following types of outcomes: patient outcomes (health and health behaviours), the quality or utilisation of healthcare services, resource use, healthcare provider outcomes (such as sick leave), or social outcomes (such as poverty, employment, or financial burden of patients, e.g. out‐of‐pocket payment, catastrophic disease expenditure);

were relevant to low‐income countries as classified by the World Bank (World Bank 2016);

were published after April 2005.

Judging relevance to low‐income countries is sometimes difficult, and we are aware that evidence from high‐income countries is not directly generalisable to low‐income countries. We based our judgments on an assessment of the likelihood that the financial arrangements considered in a review address a problem that is important in low‐income countries, would be feasible, and would be of interest to decision‐makers in low‐income countries, regardless of where the included studies took place. So, for example, we excluded arrangements requiring technology that is not widely available in low‐income countries. At least two of the overview authors made judgments about the relevance to low‐income countries and discussed with the other authors whenever there was uncertainty. We excluded reviews that only included studies from a single high‐income country due to concerns about the wider applicability of the findings of such reviews. However, we included reviews with studies from high‐income countries only if the interventions were relevant for low‐income countries.

We excluded reviews published before April 2005 as these were highly unlikely to be up‐to‐date. We also excluded reviews with methodological limitations important enough to compromise the reliability of the findings (Appendix 1).

Search methods for identification of reviews

We searched Health Systems Evidence in November 2010 using the following filters.

Health system topics = financial arrangements.

Type of synthesis = systematic review or Cochrane Review.

Type of question = effectiveness.

Publication date range = 2000 to 2010.

We conducted subsequent searches using PDQ ('pretty darn quick')‐Evidence, which was launched in 2012. We searched PDQ up to 17 December 2016, using the filter 'Systematic reviews' with no other restrictions. We updated that search, excluding records that were entered into PDQ‐Evidence prior to the date of the last search.

PDQ‐Evidence is a database of evidence for decisions about health systems, which is derived from the Epistemonikos database of systematic reviews (Rada 2013). It includes systematic reviews, overviews of reviews (including evidence‐based policy briefs) and studies included in systematic reviews. The following databases are included in Epistemonikos and PDQ‐Evidence searches, with no language or publication status restrictions.

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR).

Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effectiveness (DARE).

Health Technology Assessment Database.

PubMed.

Embase.

CINAHL.

LILACS.

PsycINFO.

Evidence for Policy and Practice Information and Co‐ordinating Centre (EPPI‐Centre) Evidence Library.

3ie Systematic Reviews and Policy Briefs.

World Health Organization (WHO) Database.

Campbell Library.

Supporting the Use of Research Evidence (SURE) Guides for Preparing and Using Evidence‐Based Policy Briefs.

European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies.

UK Department for International Development (DFID).

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) public health guidelines and systematic reviews.

Guide to Community Preventive Services.

Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH) Rx for Change.

McMaster Plus KT+.

McMaster Health Forum Evidence Briefs.

We describe the detailed search strategies for PubMed, Embase, LILACS, CINAHL, and PsycINFO in Appendix 1. We screened all records in the other databases. PDQ staff and volunteers update these searches weekly for PubMed and monthly for the other databases, screening records continually and adding new reviews to the database daily.

In addition, we screened all of the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) Group systematic reviews in Archie (i.e. Cochrane's central server for managing documents) and the reference lists of relevant policy briefs and overviews of reviews.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of reviews

Two of the overview authors (CW and CH) independently screened the titles and abstracts found in PDQ‐Evidence to identify reviews that appeared to meet the inclusion criteria. Two other authors (AO and SL) screened all of the titles and abstracts that could not be confidently included or excluded after the first screening to identify any additional eligible reviews. One of the overview authors screened the reference lists.

One of the overview authors applied the selection criteria to the full text of potentially eligible reviews and assessed the reliability of reviews that met all of the other selection criteria (Appendix 2). Two other authors (AO or SL) independently checked these judgments.

Data extraction and management

We summarised each included review using the approach developed by the SUPPORT Collaboration (Rosenbaum 2011). We used standardised forms to extract data on the background of the review (interventions, participants, settings and outcomes); key findings; and considerations of applicability, equity, economic considerations, and monitoring and evaluation. We assessed the certainty of the evidence for the main comparisons using the GRADE approach (Guyatt 2008; Schünemann 2011a; Schünemann 2011b; EPOC 2016).

Each completed SUPPORT Summary underwent peer review and was published on an open access website, where there are details about how the summaries were prepared, including how we assessed the applicability of the findings, impacts on equity, economic considerations, and the need for monitoring and evaluation. The rationale for the criteria that we used for these assessments is described in the SUPPORT Tools for evidence‐informed health policymaking (Fretheim 2009; Lavis 2009; Oxman 2009a; Oxman 2009b). As noted there, "a local applicability assessment must be done by individuals with a very good understanding of on‐the‐ground realities and constraints, health system arrangements, and the baseline conditions in the specific setting" (Lavis 2009). In this overview we have made broad assessments of the applicability of findings from studies in high‐income countries to low‐income countries using the criteria described in the SUPPORT Summaries database with input from people with relevant experience and expertise in low‐income countries.

Assessment of methodological quality of included reviews

We assessed the reliability of systematic reviews that met our inclusion criteria using criteria developed by the SUPPORT and SURE collaborations (Appendix 2). Based on these criteria, we categorised each review as having:

only minor limitations;

limitations that are important enough that it would be worthwhile to search for another systematic review and to interpret the results of this review cautiously, if no better review is available; and

limitations that are important enough to compromise the reliability of the findings and prompt the exclusion of the review.

Data synthesis

We describe the methods used to prepare a SUPPORT Summary of each review in detail on the SUPPORT Summaries website. Briefly, for each included systematic review we prepared a table summarising what the review authors searched for and what they found, we prepared 'Summary of findings' tables for each main comparison, and we assessed the relevance of the findings for low‐income countries. The SUPPORT Summaries include key messages, important background information, a summary of the findings of the review, and structured assessments of the relevance of the review for low‐income countries. We subjected the SUPPORT Summaries to review by the lead author of each review, at least one content area expert, people with practical experience in low‐income settings, and a Cochrane EPOC Group editor (AO or SL). The authors of the SUPPORT Summaries responded to each comment and made appropriate revisions, and the summaries underwent copy‐editing. The editor determined whether the overview authors had adequately addressed comments and the summary was ready for publication on the SUPPORT Summary website.

We organised the review using a modification of the taxonomy that Health Systems Evidence uses for health systems arrangements (Lavis 2015). We adjusted this framework iteratively to ensure that we appropriately categorised all of the included reviews and included and logically organised all relevant health system financial arrangements. We prepared a table listing the included reviews as well as the types of financial arrangements for which we were not able to identify a reliable, up‐to‐date review (Table 2). We also prepared a table of excluded reviews (Table 3), describing reviews that addressed a question for which another (more up‐to‐date or reliable) review was included, reviews that were published before April 2005 (for which a previous SUPPORT Summary was available), reviews with results that we considered non‐transferable to low‐income countries, and reviews with limitations that were important enough to compromise the reliability of the findings.

2. Included reviews.

| FINANCIAL ARRANGEMENT | INCLUDED REVIEWS |

| Collection of funds | |

| Financing of insurance | No eligible systematic review found |

| User fees | The impact of user fees on access to health services in low‐ and middle‐income countries (Lagarde 2011) |

| Community loan funds | No eligible systematic review found |

| Health savings accounts | No eligible systematic review found |

| External funding | The impact of aid on maternal and reproductive health: a systematic review to evaluate the effect of aid on the outcomes of Millennium Development Goal 5 (Hayman 2011) |

| Insurance schemes | |

| Social health insurance | Impact of national health insurance for the poor and the informal sector in low‐ and middle‐income countries: a systematic review (Acharya 2012) |

| Community based health insurance | Impact of national health insurance for the poor and the informal sector in low‐ and middle‐income countries: a systematic review (Acharya 2012) |

| Private health insurance | No eligible systematic review found |

| Purchasing of services | |

| Funding of health service organisations | No eligible systematic review found |

| Payment methods for health workers ‐ primary care physicians |

What is the evidence of the impact of increasing salaries on improving the performance of public servants, including teachers, nurses and mid‐level occupations, in low‐ and middle‐income countries: is it time to give pay a chance? (Carr 2011) |

| Payment methods for health workers ‐ specialist physicians |

No eligible systematic review found |

| Payment methods for health workers ‐ non‐physician health workers |

No eligible systematic review found |

| Financial incentives and disincentives for recipients of care | |

| Financial incentives for recipients of care ‐ medication adherence |

Interventions for enhancing medication adherence (Haynes 2008) |

| Financial incentives for recipients of care ‐ TB adherence |

Incentives and enablers to improve adherence in tuberculosis(Lutge 2015) |

| Conditional cash transfers | The impact of conditional cash transfers on health outcomes and use of health services in low and middle income countries (Lagarde 2009) |

| Non‐conditional financial benefits | No eligible systematic review found |

| Voucher schemes | The Impact of vouchers on the use and quality of health care in developing countries: a systematic review (Brody 2013) |

| Caps and co‐payments ‐ drugs |

Pharmaceutical policies: effects of cap and co‐payment on rational use of medicines (Luiza 2015) |

| Reference pricing ‐ health services |

Pharmaceutical policies: effects of reference pricing, other pricing, and purchasing policies (Acosta 2014) |

| Financial incentives and disincentives for providers of care | |

| Pay‐for‐performance ‐ effects on delivery of health interventions |

Paying for performance to improve the delivery of health interventions in low‐ and middle‐income countries (Witter 2012) |

| Pay‐for‐performance ‐ effects on outpatient referrals from primary care to secondary care |

Interventions to improve outpatient referrals from primary care to secondary care (Akbari 2008) |

| Pay‐for‐performance ‐ effects on the quality of health care provided by primary care physicians |

The effect of financial incentives on the quality of health care provided by primary care physicians (Scott 2011) |

| Budgets | No eligible systematic review found |

| Incentives to practice in underserved areas | Interventions for increasing the proportion of health professionals practising in underserved communities (Grobler 2015) |

| Managing the movement of health workers | Financial interventions and movement restrictions for managing the movement of health workers between public and private organisations in low and middle‐income countries (Rutebemberwa 2014) |

| Incentives for career choices | No eligible systematic review found |

TB: tuberculosis.

3. Excluded reviews.

| Review ID | Excluded reviews | Reasons for exclusion |

| Attree 2006 | The social costs of child poverty: a systematic review of the qualitative evidence | Major limitations |

| Barnighausen 2009 | Financial incentives for return of service in underserved areas: a systematic review | More relevant review found |

| Bellows 2011 | The use of vouchers for reproductive health services in developing countries: systematic review | Major limitations |

| Bhutta 2009 | Delivering interventions to reduce the global burden of stillbirths: improving service supply and community demand | Major limitations |

| Bock 2001 | A spoonful of sugar: improving adherence to tuberculosis treatment using financial incentives | Out of date |

| Borghi 2006 | Mobilising financial resources for maternal health | More relevant review found |

| Bosch‐Capblanch 2007 | Contracts between patients and healthcare practitioners for improving patients' adherence to treatment, prevention and health promotion activities | More relevant review found |

| Buchmueller 2005 | The effect of health insurance on medical care utilization and implications for insurance expansion | Major limitations |

| Chaix‐Couturier 2000 | Effects of financial incentives on medical practice | More relevant review found |

| De Janvry 2006 | Making conditional cash transfer programs more efficient | Major limitations |

| Doran 2006 | Pay‐for‐performance programs in family practices in the United Kingdom | More relevant review found |

| Eichler 2006 | Can "pay for performance" increase utilization by the poor and improve the quality of health services? | More relevant review found |

| Ekman 2004 | Community‐based health insurance in low‐income countries: a systematic review of the evidence | Major limitations |

| Ensor 2004 | Overcoming barriers to health service access and influencing the demand side through purchasing | Major limitations |

| Faden 2011 | Active pharmaceutical management strategies of health insurance systems to improve cost‐effective use of medicines in low‐ and middle‐income countries | Major limitations |

| Forbes 2002 | Interventions targeted at women to encourage the uptake of cervical screening | Out of date |

| Fournier 2009 | Improved access to comprehensive emergency obstetric care and its effect on institutional maternal mortality in rural Mali | More relevant review found |

| Gemmill 2008 | What impact do prescription drug charges have on efficiency and equity? | More relevant review found |

| Giuffrida 1997 | Should we pay the patient? | Out of date |

| Giuffrida 1999 | Target payments in primary care: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes | Out of date |

| Gosden 2000 | Capitation, salary, fee‐for‐service and mixed systems of payment: effects on the behaviour of primary care physicians | More relevant review found |

| Gosden 2001 | Impact of payment method on behaviour of primary care physicians: a systematic review | Out of date |

| Handa 2006 | The experience of conditional cash transfers in Latin America and the Caribbean | More relevant review found |

| Yoong 2012 | The impact of economic resource transfers to women versus men | More relevant review found |

| Kane 2004 | A structured review of the effect of economic incentives on consumers' preventive behavior | Out of date |

| Giuffrida 2000 | Target payments in primary care: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes | More relevant review found |

| Lagarde 2006 | Evidence from systematic reviews to inform decision making regarding financing mechanisms that improve access to health services for poor people | More relevant review found |

| Lagarde 2007 | Conditional cash transfers for improving uptake of health interventions in low‐ and middle‐income countries | More relevant review found |

| Lagarde 2008 | The impact of user fees on health service utilization in low‐ and middle‐income countries: how strong is the evidence? | Major limitations |

| Lawn 2009 | Two million intrapartum‐related stillbirths and neonatal deaths: where, why, and what can be done? | More relevant review found |

| Lee 2009 | Linking families and facilities for care at birth: what works to avert intrapartum‐related deaths? | Major limitations |

| Lucas 2008 | Financial benefits for child health and well‐being in low‐income or socially disadvantaged families in developed world countries | Not transferable to low‐income countries |

| Mannion 2008 | Payment for performance in health care | More relevant review found |

| Meyer 2011 | The impact of vouchers on the use and quality of health goods and services in developing countries: a systematic review | Major limitations |

| Oxman 2008 | An overview of research on the effects of results‐based financing | More relevant review found |

| Petersen 2006 | Does pay‐for‐performance improve the quality of health care? | More relevant review found |

| Patouillard 2007 | Can working with the private for‐profit sector improve utilization of quality health services by the poor? | Major limitations |

| Petry 2012 | Financial reinforcers for improving medication adherence: findings from a meta‐analysis | More relevant review found |

| Rosenthal 2006 | What is the empirical basis for paying for quality in health care? | More relevant review found |

| Siddiqi 2007 | Towards environment assessment model for early childhood development | Major limitations |

| Sutherland 2008 | Paying the patient: does it work? A review of patient‐targeted incentives | More relevant review found |

| Van Herck 2010 | Systematic review: effects, design choices, and context of pay‐for‐performance in health care | More relevant review found |

| WHO 1996 | Maternity waiting homes: a review of experiences | More relevant review found |

| WHO 2003 | Adherence to long‐term therapies: evidence for action | More relevant review found |

| WHO 2010b | Increasing access to health workers in remote and rural areas through improved retention: global policy recommendations | More relevant review found |

We described the characteristics of the included reviews in a table that included the date of the last search, any important limitations, and what the review authors searched for and what they found (Appendix 3). We summarised our detailed assessments of the reliability of the included reviews in a separate table (Table 4) showing whether individual reviews met each criterion in Appendix 2.

4. Reliability of included reviews.

| Review | A. Identification, selection and critical appraisal of studiesa | B. Analysisb | C. Overallc | |||||||||||

| 1. Selection criteria | 2. Search | 3. Up‐to‐date | 4. Study selection | 5. Risk of bias | 6. Overall | 1. Study characteristics | 2. Analytic methods | 3. Heterogeneity | 4. Appropriate synthesis | 5. Exploratory factors | 6. Overall | 1. Other considerations | 2. Reliability of the review | |

| Acharya 2012 | + | ? | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Acosta 2014 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Akbari 2008 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Brody 2013 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ? | + | + | + |

| Carr 2011 | + | + | + | + | + | + | ? | + | + | + | ? | + | + | + |

| Grobler 2015 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Hayman 2011 | + | + | + | + | ? | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Haynes 2008 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Lagarde 2009 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Lagarde 2011 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Luiza 2015 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Lutge 2015 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Rutebemberwa 2014 | + | ? | + | + | + | + | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | + | + | + |

| Scott 2011 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Witter 2012 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

aIdentification, selection and critical appraisal of studies

1. Selection criteria: were the criteria used for deciding which studies to include in the review reported? (+ yes; ? can't tell/partially; − no)

2. Search: was the search for evidence reasonably comprehensive? (+ yes; ? can't tell/partially; − no)

3. Up‐to‐date: is the review reasonably up‐to‐date? (+ yes; ? can't tell/partially; − no)

4. Study selection: was bias in the selection of articles avoided? (+ yes; ? can't tell/partially; − no)

5. Risk of bias: did the authors use appropriate criteria to assess the risk for bias in analysing the studies that are included? (+ yes; ? can't tell/partially; − no)

6. Overall: how would you rate the methods used to identify, include and critically appraise studies? (+ only minor limitations, − important limitations)

bAnalysis

1. Study characteristics: were the characteristics and results of the included studies reliably reported? (+ yes; ? can't tell/partially; − no, NA: Not applicable; e.g. no studies or data)

2. Analytic methods: were the methods used by the review authors to analyse the findings of the included studies reported? (+ yes; ? can't tell/partially; − no, NA = Not applicable; e.g. no studies or data)

3. Heterogeneity: did the review describe the extent of heterogeneity? (+ yes; ? can't tell/partially; − no, NA: not applicable; e.g. no studies or data)

4. Appropriate synthesis: were the findings of the relevant studies combined (or not combined) appropriately relative to the primary question the review addresses and the available data? (+ yes; ? can't tell/partially; − no, NA: not applicable; e.g. no studies or data)

5. Exploratory factors: did the review examine the extent to which specific factors might explain differences in the results of the included studies? (+ yes; ? can't tell/partially; − no, NA: not applicable; e.g. no studies or data)

6. Overall: how would you rate the methods used to analyse the findings relative to the primary question addressed in the review? (+ only minor limitations, − important limitations)

cOverall

1. Other considerations: are there any other aspects of the review not mentioned before which lead you to question the results? (+ yes; ? can't tell/partially; − no)

2. Reliability of the review: based on the above assessments of the methods how would you rate the reliability of the review? (+ only minor limitations, − important limitations)

Our structured synthesis of the findings of our overview was based on two tables. We summarised the main findings of each review in a table that included the key messages from each SUPPORT Summary (Table 5). In a second table (Table 6), we reported the direction of the results and the certainty of the evidence for each of the following types of outcomes: health and other patient outcomes; access, coverage or utilisation; quality of care; resource use; social outcomes; impacts on equity; healthcare provider outcomes; adverse effects (not captured by undesirable effects on any of the preceding types of outcomes); and any other important outcomes (that did not fit into any of the preceding types of outcomes) (EPOC 2016). The direction of results were categorised as: a desirable effect, little or no effect, an uncertain effect (very low‐certainty evidence), no included studies, an undesirable effect, not reported (i.e. not specified as a type of outcome that was considered by the review authors), or not relevant (i.e. no plausible mechanism by which the type of health system arrangement could affect the type of outcomes).

5. Key messages of included reviews.

| FINANCIAL ARRANGEMENT | KEY MESSAGES |

| Collection of funds | |

|

User fees Lagarde 2011 |

➡ The effects for the following are uncertain.

➡ The impacts of changes in user fees on utilisation may depend on whether they are for preventive or curative services, whether increases are combined with quality improvement efforts, and the size of the change in fees. ➡ The impact of changes in user fees on equity are uncertain. However, poorer people may be more sensitive to changes in user fees. ➡ Changes to user fees should be carefully planned and monitored, and the impacts of changes to user fees should be rigorously evaluated. |

|

External funding Hayman 2011 |

➡ It is uncertain whether aid delivered under the Paris Principles improves maternal and reproductive health outcomes. ➡ Aid‐supported interventions to improve maternal and reproductive health should include an evaluation plan. |

| Insurance schemes | |

|

Social health insurance/ Community‐based health insurance Acharya 2012 |

➡ Community health insurance may increase utilisation of health services, but it is uncertain if it improves health outcomes or changes out‐of‐pocket expenditure among those insured in low‐income countries. ➡ It is uncertain if social health insurance improves utilisation of health services and health outcomes, leads to changes in out‐of‐pocket expenditure, or improves equity among those insured in low‐income countries. ➡ Most of the included studies were conducted in low‐ and middle‐income countries in Latin America, Asia, and Africa. |

| Purchasing of services | |

|

Payment methods for primary care physicians Carr 2011 |

➡ It is uncertain whether increasing the salaries of health professionals or other professionals in the public sector improves either the quantity or quality of their work. ➡ Rather than making assumptions about the intended or unintended effects of fixed salary reforms that increase the salaries of health professionals, such policies should be evaluated, if possible using randomised trials or interrupted time series studies. |

| Financial incentives and disincentives for recipients of care | |

|

Financial incentives for recipients of care ‐ medication adherence Haynes 2008 |

➡ It is uncertain whether interventions to increase adherence to short‐term treatments improve adherence or patient outcomes. ➡ Interventions aimed at increasing adherence to long‐term treatments may improve adherence, but it is uncertain whether they improve patient outcomes. ➡ Most of the included studies assessed complex interventions with multiple components in high‐income countries. Adherence interventions may be difficult to implement in low‐income countries where health systems face greater challenges. |

|

Financial incentives for recipients of care ‐ TB adherence Lutge 2015 |

➡ Sustained material incentives may lead to little or no difference in cure or completion of treatment for active TB, compared to no incentive. ➡ It is not clear if sustained material incentives improve completion of TB prophylaxis, compared to no incentive, because findings varied across studies. ➡ A one‐time‐only incentive may increase the number of people who return to a clinic for reading of their tuberculin skin test, compared to no incentive. ➡ A one‐time‐only incentive probably increases the number of people who return to a clinic to start or continue TB prophylaxis, compared to no incentive. ➡ Compared to a non‐cash incentive, cash incentives may slightly increase the number of people who return to a clinic for reading of their tuberculin skin test and may increase the number of people who complete TB prophylaxis. ➡ Compared to counselling or education interventions, material incentives may increase the number of people who return to a clinic for reading of their tuberculin skin test. ➡ Compared to counselling or education interventions, material incentives may lead to little or no difference in the number of people who return to a clinic to start or continue TB prophylaxis or in the number of people who complete TB prophylaxis. ➡ Higher cash incentives may slightly improve the number of people who return to a clinic for reading of their tuberculin skin test, compared to lower cash incentives. |

|

Conditional cash transfers Lagarde 2009 |

➡ Conditional cash transfer programmes in low‐ and middle‐income countries probably lead to an increase in the use of health services and mixed effects on immunisation coverage and health status. ➡ The capacity of each health system to deal with the increased demand should be considered, particularly in low‐income countries where the capacity of health systems may not be sufficient. ➡ The cost‐effectiveness of conditional cash transfer programmes, compared with supply‐side strategies and other policy options, has not been evaluated. |

|

Voucher schemes Brody 2013 |

➡ Vouchers may improve the utilisation of reproductive health services, targeting specific populations, quality of care, and health outcomes. ➡ Vouchers may improve the utilisation of insecticide‐treated bed nets and targeting specific populations. ➡ The effect of vouchers for insecticide‐treated bed nets on quality of care and health outcomes is uncertain. ➡ The cost‐effectiveness of voucher programmes is uncertain for both reproductive health services and insecticide‐treated bed nets. ➡ All the included studies were conducted in low‐ and middle‐income countries. |

|

Caps and co‐payments for drugs Luiza 2015 |

➡ Restrictive caps may decrease use of medicines for symptomatic conditions and overall use of medicines and insurers' expenditures on medicines, and they may have uncertain effects on health service utilisation. ➡ A combination of a cap, co‐insurance, and a ceiling may increase the use of medicines overall and for symptomatic and asymptomatic conditions, and decrease the cost of medicines for both patients and insurers. ➡ A combination of a cap and fixed co‐payments may increase the use of medicines for symptomatic conditions, and it has uncertain effects on the insurer's cost of medicines. ➡ Fixed co‐payments may decrease the use of medicines for symptomatic and asymptomatic conditions and the insurer's expenditures on medicines. ➡ Fixed and tier co‐payments have uncertain effects on the use of medicines and the insurer's expenditures on medicines. ➡ A combination of a ceiling and fixed co‐payments may slightly decrease the use of medicines and lead to little or no difference in health service utilisation. ➡ A combination of a ceiling and co‐insurance probably slightly decreases the overall use of medicines, may decrease the use of medicines for symptomatic conditions, may slightly decrease the insurer's short‐term expenditures on medicines, and may increase health service utilisation. ➡ None of the included studies were conducted in a low‐income country or reported health outcomes. |

|

Caps and co‐payments for health services Acosta 2014 |

➡ Reference pricing may reduce insurers' cumulative drug expenditures by shifting drug use from cost‐share drugs to reference drugs. ➡ Index pricing may increase the use of the generic drugs, may reduce the use of brand drugs, slightly reduce the price of generic drugs, and may have little or no effect on the price of brand drugs. ➡ It is uncertain whether maximum pricing affects drug expenditures. ➡ The effects of these policies on healthcare utilisation or health outcomes are uncertain. ➡ None of the included studies were conducted in a low‐income country. ➡ The effects of other pharmaceutical pricing and purchasing policies are uncertain. |

| Financial incentives and disincentives for providers of care | |

|

Paying for performance ‐ effects on delivery of health interventions Witter 2012 |

➡ We are very uncertain whether pay‐for‐performance improves provider performance, the utilisation of services, patient outcomes or resource use in low‐ and middle‐income countries. ➡ Unintended effects of pay‐for‐performance schemes may include:

➡ There is a lack of evidence about the economic consequences of pay‐for‐performance schemes in low‐ and middle‐income countries. ➡ It is uncertain whether pay‐for‐performance improves provider performance, the utilisation of services, patient outcomes, or resource use in low‐ and middle‐income countries. |

|

Paying for performance ‐ effects on outpatient referrals from primary care to secondary care Akbari 2008. |

➡ The effects of financial incentives on referral rates are uncertain. |

|

Pay‐for‐performance ‐ effects on the quality of health care provided by primary care physicians Scott 2011 |

➡ The effects of financial incentives to improve the quality of healthcare provided by primary care physicians are uncertain. ➡ If financial incentives for quality improvement are used, they should be carefully designed and evaluated. ➡ Unintended consequences and economic consequences should be evaluated, as well as impacts on the quality of care and access to care. |

|

Financial incentives to practice in underserved areas Grobler 2015 |

➡ It is uncertain whether any of the following types of interventions to recruit or retain health professionals increase the number of health professionals practising in underserved areas,

|

|

Managing the movement of health workers Rutebemberwa 2014 |

➡ No rigorous studies have evaluated the effects of interventions to manage the movement of health workers between public and private organisations. ➡ There is a need for well‐designed studies to evaluate the impact of interventions that attempt to regulate health worker movement between public and private organisations in low‐income countries. |

TB: tuberculosis.

6. Intervention‐outcome matrix.

| Financial arrangement | Patient outcomes | Access, coverage, utilisation | Quality of care | Resource use | Social outcomes | Impacts on equity | Healthcare provider outcomes | Adverse effects | Other |

| Collection of funds | |||||||||

| User fees Lagarde 2011 |

NR | ?㊉㊀㊀㊀ | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| External funding Hayman 2011 |

?㊉㊀㊀㊀ | ?㊉㊀㊀㊀ | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Insurance schemes | |||||||||

| Social health insurance Acharya 2012 |

?㊉㊀㊀㊀ | ?㊉㊀㊀㊀ | NR | NR | NR | ?㊉㊀㊀㊀ | NR | NR | NR |

| Community‐based health insurance Acharya 2012 |

?㊉㊀㊀㊀ | ✔㊉㊉㊀㊀ | NR | NR | NR | ?㊉㊀㊀㊀ | NR | NR | NR |

| Purchasing of services | |||||||||

| Payment methods for primary care physicians Carr 2011 |

NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Financial incentives and disincentives for recipients of care | |||||||||

| Financial incentives for recipients of care ‐ medication adherence Haynes 2008 |

?㊉㊀㊀㊀ | ✔㊉㊉㊀㊀ | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Financial incentives for recipients of care ‐ TB adherence Lutge 2015 ‐ Sustained material incentives |

Ø㊉㊉㊀㊀ | ?㊉㊀㊀㊀ | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| ‐ One‐time only incentive | NR | ✔㊉㊉㊀㊀1 ✔㊉㊉㊉㊀2 |

NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| ‐ Cash incentives3 | NR | ✔㊉㊉㊀㊀4 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| ‐ Material incentives5 | NR | ✔㊉㊉㊀㊀6 ∅㊉㊉㊀㊀7 |

NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| ‐ Higher cash incentives8 | NR | ✔㊉㊉㊀㊀9 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Conditional cash transfers Lagarde 2009 |

✔㊉㊉㊉㊀ | ✔㊉㊉㊉㊀ | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Voucher schemes Brody 2013 ‐ Reproductive health services ‐ Insecticide‐treated bednets |

✔㊉㊉㊀㊀ ? ㊉㊀㊀㊀ |

✔㊉㊉㊀㊀ ✔㊉㊉㊀㊀ |

✔㊉㊉㊀㊀ NR |

?㊉㊀㊀㊀ NR |

NR | ✔㊉㊉㊀㊀ ✔㊉㊉㊀㊀ |

NR | NR | NR |

| Caps and co‐payments for drugs Luiza 2015 ‐ Restrictive caps |

NR |

x㊉㊉㊀㊀10 ?㊉㊀㊀㊀11 |

NR | ✔㊉㊉㊀㊀12 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| ‐ Combination of a cap, co‐insurance, and a ceiling | NR | ✔㊉㊉㊀㊀13 | NR | ✔㊉㊉㊀㊀14 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| ‐ Combination of a cap and fixed co‐payments | NR | ✔㊉㊉㊀㊀15 | NR | ?㊉㊀㊀㊀12 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| ‐ Fixed co‐payments | NR | x㊉㊉㊀㊀16 | NR | ✔㊉㊉㊀㊀12 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| ‐ Fixed and tier co‐payments | NR | ?㊉㊀㊀㊀17 | NR | ?㊉㊀㊀㊀12 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| ‐ Combination of a ceiling and fixed co‐payments | NR |

x㊉㊉㊀㊀18 ∅㊉㊉㊀㊀11 |

NR | ?㊉㊀㊀㊀12 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| ‐ Combination of a ceiling and co‐insurance | NR |

x ㊉㊉㊉㊀18 x ㊉㊉㊀㊀15 x ㊉㊉㊀㊀19 |

NR | ✔㊉㊉㊀㊀20 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Reference pricing Acosta 2014 |

NR | NR | NR | ✔㊉㊉㊀㊀14 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Financial incentives and disincentives for providers of care | |||||||||

| Pay‐for‐performance ‐ effects on delivery of health interventions Akbari 2008 |

NR | NR | ?㊉㊀㊀㊀ | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Pay‐for‐performance ‐ effects on outpatient referrals from primary to secondary care Scott 2011 |

NR | NR | ?㊉㊀㊀㊀ | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Pay‐for‐performance ‐ effects on the quality of healthcare provided by primary care physicians Witter 2012 |

✔㊉㊉㊀㊀ | ?㊉㊀㊀㊀ | ?㊉㊀㊀㊀ | ?㊉㊀㊀㊀ | NR | NR | NR | ?㊉㊀㊀㊀ | NR |

| Incentives to practice in underserved areas Grobler 2015 |

NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | ?㊉㊀㊀㊀ | NR | NR | NR |

| Managing the movement of health workers Rutebemberwa 2014 |

NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS |

✔ = a desirable effect

Ø = little or no effect

? = uncertain effect

x = undesirable effect

NR = not reported

NS = no studies were included

1. Return for reading of tuberculin skin test

2. Starting or continuing TB prophylaxis

3. Compared to non‐cash incentives

4. Completion of TB prophylaxis and slight increase in return for reading of tuberculin skin test

5. Compared to counselling or education interventions

6. Return for reading of tuberculin skin test

7. Starting, continuing, or completing TB prophylaxis

8. Compared to lower cash incentives

9. Slightly increased return for reading of tuberculin skin test

10. Decreased use of medicines for symptomatic conditions and overall use of medicines

11. Health service utilisation

12. Insurers expenditures on medicines

13. Increased use of medicines overall, for symptomatic conditions, and for asymptomatic conditions

14. Cost of medicines for both patients and insurers

15. Decreased use of medicines for symptomatic conditions

16. Decreased use of medicines for symptomatic and asymptomatic conditions

17. Use of medicines

18. Slightly decreased overall use of medicines

19. Increased health service utilisation

20. Slightly decreased insurer’s short‐term

⊕⊕⊕⊖ = Moderate‐certainty evidence

Definition: this research provides a good indication of the likely effect. The likelihood that the effect will be substantially different is moderate.

Implications: this evidence provides a good basis for making a decision about whether to implement the intervention. Monitoring of the impact is likely to be needed and impact evaluation may be warranted if it is implemented.

⊕⊕⊖⊖ = Low‐certainty evidence

Definition: this research provides some indication of the likely effect. However, the likelihood that it will be substantially different is high.

Implications: this evidence provides some basis for making a decision about whether to implement the intervention. Impact evaluation is likely to be warranted if it is implemented.

⊕⊖⊖⊖ = Very low certainty evidence

Definition: this research does not provide a reliable indication of the likely effect. The likelihood that the effect will be substantially different is very high.

Implications: this evidence does not provide a good basis for making a decision about whether to implement the intervention. Impact evaluation is very likely to be warranted if it is implemented.

We took into account all other relevant considerations besides the findings of the included reviews when drawing conclusions about implications for practice (EPOC 2016). Our conclusions about implications for systematic reviews were based on types of financial arrangements for which we were unable to find a reliable up‐to‐date review along with limitations identified in the included reviews. These limitations include considerations related to the applicability of the findings and likely impacts on equity. Our conclusions about implications for future evaluations were based on the findings of the included reviews (EPOC 2016).

Results

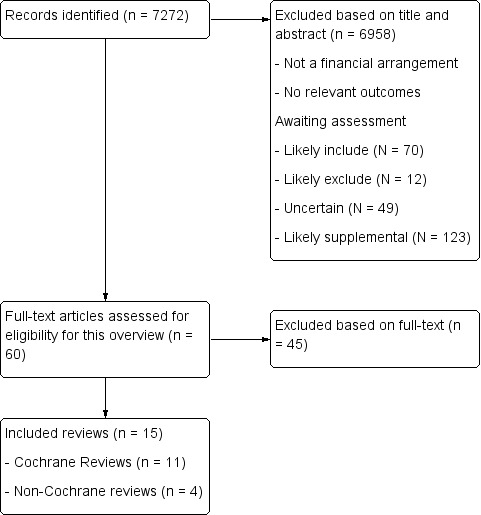

We identified 7272 systematic reviews for eligibility across all four overviews. Following the screening of titles and abstracts, we excluded 6958 reviews as clearly irrelevant for this overview (Figure 1). We assessed the full texts of 60 reviews for eligibility and found 15 of them to meet the inclusion criteria for this overview (Table 2). We list excluded reviews of financial arrangements in Table 3. We excluded 13 reviews because of important methodological limitations (Ekman 2004; Ensor 2004; Buchmueller 2005; Attree 2006; De Janvry 2006; Siddiqi 2007; Patouillard 2007; Lagarde 2008; Bhutta 2009; Lee 2009; Bellows 2011; Faden 2011; Meyer 2011), 6 for being out‐of‐date (Giuffrida 1997; Giuffrida 1999; Bock 2001; Gosden 2001; Forbes 2002; Kane 2004), 25 because a more relevant review was available (WHO 1996; Chaix‐Couturier 2000; Giuffrida 2000; Gosden 2000; WHO 2003; Borghi 2006; Doran 2006; Eichler 2006; Handa 2006; Lagarde 2006; Petersen 2006; Rosenthal 2006; Bosch‐Capblanch 2007; Lagarde 2007; Gemmill 2008; Mannion 2008; Oxman 2008; Sutherland 2008; Barnighausen 2009; Fournier 2009; Lawn 2009; Van Herck 2010; WHO 2010b; Petry 2012; Yoong 2012), and 1 because it was not transferable to low‐income countries (Lucas 2008). Appendix 4 lists the reviews still awaiting classification.

1.

Flow diagram

Description of included reviews

The 15 included systematic reviews were published between 2008 and 2015 (Table 2). Of these, 11 were Cochrane Reviews (Akbari 2008; Haynes 2008; Lagarde 2009; Lagarde 2011; Scott 2011; Witter 2012; Acosta 2014; Rutebemberwa 2014; Grobler 2015; Luiza 2015; Lutge 2015). The dates of the most recent search reported in the included reviews ranged from February 2007 in Haynes 2008 to June 2015 in Lutge 2015. The number of primary studies on financial arrangements in each included review ranged from zero in Rutebemberwa 2014 to 78 in Haynes 2008.

Four reviews had no included studies from a low‐ or middle‐income country (Scott 2011; Acosta 2014; Grobler 2015; Luiza 2015), while six reviews included only studies conducted in low‐ and middle‐income countries (Lagarde 2009; Carr 2011; Hayman 2011; Lagarde 2011; Acharya 2012; Witter 2012). Four reviews included studies from a mix of low‐, middle‐ and high‐income countries (Akbari 2008; Haynes 2008; Brody 2013; Lutge 2015) .One review did not have any included studies (Rutebemberwa 2014).

The reviews reported results on financial arrangements from 276 studies with the following designs.

115 (42%) randomised trials.

11 (4%) non‐randomised trials.

23 (8%) controlled before‐after studies.

51 (19%) interrupted time series studies.

9 (3%) repeated measures studies.

67 (24%) other non‐randomised studies (including cohort and case‐control studies).

Overall, 119 (43%) of the studies in the 15 included reviews were conducted in low‐ and middle‐income countries, 67 (24%) in the USA, 25 (9%) in Canada, and 55 (20%) in Western Europe. The other 10 studies (4%) were conducted in Australia (8 studies), the United Arab Emirates (1), and Taiwan (1).

Study settings varied and included primary care; family, workplace and community settings; and outpatient and inpatient settings in hospitals and non‐primary care health centres. The studies included in the reviews involved various health workers, including physicians, nurses, and pharmacists. Recipients of care participating in studies included in the reviews included children and adults. Outcomes examined by the reviews included healthcare provider performance, patient outcomes, access to care, coverage, utilisation of healthcare services, equity, and adverse effects.

We grouped the financial arrangements addressed in the reviews into five categories.

Collection of funds: two reviews (Hayman 2011; Lagarde 2011).

Insurance schemes: one review (Acharya 2012).

Purchasing of services: one review (Carr 2011).

Incentives for providers of care: five reviews (Akbari 2008; Scott 2011; Witter 2012; Rutebemberwa 2014; Grobler 2015).

Incentives for recipients of health care: six reviews (Haynes 2008; Lagarde 2009; Lutge 2015; Brody 2013; Luiza 2015; Acosta 2014).

Methodological quality of included reviews

We describe the methodological quality (reliability) of the included reviews in Table 4. We judged the 15 reviews to have only minor limitations.

Effect of interventions

We summarise the key messages from the included reviews in Table 5. Table 6 summarises the key findings of the different financial interventions considered by each of the included reviews and the certainty of this evidence by outcome. Table 7 provides a summary of the main findings, organised into the following categories.

7. Summary of effects of interventions and certainty of evidence.

| Interventions found to have desirable effects on at least one outcome with moderate‐ or high‐certainty evidence and no moderate‐ or high‐certainty evidence of undesirable effects |

Financial incentives and disincentives for recipients of care

|

| Interventions found to have moderate or high certainty evidence of at least one outcome with an undesirable effect and no moderate or high certainty evidence of desirable effects |

Financial incentives and disincentives for recipients of care

|

| Interventions for which the certainty of the evidence was low or very low (or no studies were found) for all outcomes examined |

Collection of funds

Insurance schemes

Purchasing of services

Financial incentives and disincentives for recipients of care

Financial incentives and disincentives for providers of care

|

Interventions found to have desirable effects on at least one outcome with moderate‐ or high‐certainty evidence and no moderate‐ or high‐certainty evidence of undesirable effects.

Interventions found to have moderate or high certainty evidence of at least one outcome with an undesirable effect and no moderate or high certainty evidence of desirable effects.

Interventions for which the certainty of the evidence was low or very low (or no studies were found) for all outcomes examined.

Collection of funds

We included one review of the effects of user fees, Lagarde 2011, and one of the effects of external funding (aid), Hayman 2011. We found no relevant systematic reviews for financing of insurance, community loan funds, or health saving accounts.

Lagarde and Palmer conducted a review of the impact of user fees on access to health services in low‐ and middle‐income countries (Lagarde 2011). The authors included 17 studies from 17 countries. The type of health services and the level and nature of payments varied. While some of the studies assessed the effects of large‐scale national reforms, other studies looked at small‐scale pilot projects. All of the evidence was of very low certainty, so it is uncertain whether changes in user fees impact utilisation or equity.

Hayman and colleagues compared the effects of aid delivered under the Paris Principles (Paris Declaration 2005) versus aid delivered outside this framework, on Millennium Development Goal 5 (maternal health) outcomes (Hayman 2011). The principles of the Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness include ownership (i.e. recipient countries set their own development strategies); alignment (i.e. donor countries and organisations bring their support in line with strategies set by recipient countries and use local systems to deliver that support); harmonisation (i.e. donors coordinate their actions, simplify procedures and share information to avoid duplication); management for results (i.e. recipient countries and donors focus on producing and measuring results); and mutual accountability (i.e. donors and recipient countries are accountable for development results). The authors included 10 studies for aid delivered under the Paris Principles and 20 studies for aid in general. The review shows that it is uncertain whether aid delivered under the Paris Principles improves maternal and reproductive health outcomes compared to aid delivered without conforming to those principles (Hayman 2011).

Insurance schemes

We included one review that assessed the effects of both community‐based health insurance and social health insurance in low‐ and middle‐income countries (Acharya 2012). We did not find any eligible reviews of the effects of private health insurance. Acharya 2012 included 24 studies conducted in sub‐Saharan Africa, Latin America, Southeast Asia, and Eastern Europe. The studies found that community‐based health insurance may increase utilisation of health services, but it is uncertain if it improves health outcomes or changes out‐of‐pocket expenditure among those insured in low‐income countries (Acharya 2012). It is uncertain if social health insurance improves utilisation of health services and health outcomes, leads to changes in out‐of‐pocket expenditures, or improves equity among those insured in low‐income countries (very low‐certainty evidence).

Purchasing of services