Abstract

The bladder presents an attractive target for topical drug delivery. The barrier function of the bladder mucosa (urothelium) presents a penetration challenge for small molecules and nanoparticles. We found that focal mechanical injury of the urothelium greatly enhances the binding and penetration of intravesically-administered cell-penetrating peptide CGKRK (Cys-Gly-Lys-Arg-Lys). Notably, the CGKRK bound to the entire urothelium, and the peptide was able to penetrate into the muscular layer. This phenomenon was not dependent on intravesical bleeding and was not caused by an inflammatory response. CGKRK also efficiently penetrated the urothelium after disruption of the mucosa with ethanol, suggesting that loss of barrier function is a prerequisite for widespread binding and penetration. We further demonstrate that the ability of CGKRK to efficiently bind and penetrate the urothelium can be applied towards mucosal targeting of CGKRK-conjugated nanogels to enable efficient and widespread delivery of a model payload (rhodamine) to the bladder mucosa.

Keywords: urothelium, nanogel, peptide, delivery, bladder

Graphical Abstract

Cell penetrating peptide shows efficient binding to the bladder after focal injury to mucosa

INTRODUCTION

For many diseases and pathological conditions of the bladder, intravesical administration is the preferred method of delivery of drugs and therapeutics. In the intact bladder, the umbrella cells in the upper mucosal layer form a tight barrier that prevents the systemic absorption of molecules and solutes,(1, 2) and although this greatly improves safety of intravesical therapies, it also results in limited penetration of therapeutic molecules into the bladder urothelium. Therefore, several approaches have been explored to enhance urothelium delivery of drugs in preclinical models over the past decade.(3, 4) Thus, dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) has been shown to enhance the accumulation of paclitaxel micelles in the mucosal layer.(5) Similarly, it has been shown that the intravesical administration of protamine sulfate,(1) ethanol,(6) or diluted acid(7) disrupts the barrier function and enhances penetration of molecules and nanoparticles into the urothelium. In addition, barrier function of urothelium can also be partially overcome by bladder distension with fluid.(2) Although these studies have greatly improved our understanding of the challenges involved in intravesical therapies, these approaches have not resulted in homogenous penetration of the urothelium or pose significant risks, prompting the need to develop better bladder delivery approaches.

Several recent reports have described the use of cell-penetrating peptides in delivering therapeutic proteins and nucleic acids to the bladder.(8–11) In the majority of these studies, the tests were performed on bladders with intact mucosa, which is contrary to clinical presentations in which the urothelium layer is rarely intact as a result of underlying pathological processes and treatments. For instance, during trans-urethral resection (TUR) of non-invasive bladder carcinoma in situ (CIS),(12) the urothelium layer is scratched off together with the cancerous lesion, exposing lamina propria. Another example is interstitial cystitis, which is manifested by the leaky and dysfunctional mucosa.(13, 14) Therefore, the ability of cell-penetrating peptides and delivery of molecules to penetrate mucosal layers following damage to urothelium is an important consideration and has not been studied in detail to-date. Concurrently, since the Ruoslahti group discovered the tumor stroma-binding peptide CGKRK using in vivo phage display screening of squamous cell carcinoma mouse models(15) the efficient cell-penetrating properties of CGKRK have been demonstrated.(16) While working on experiments to study the binding and penetration of CGKRK to the bladder wall, we observed a phenomenon in which intravesically-administered CGKRK efficiently binds to the entire urothelium surface following focal damage. We also demonstrated that the CGKRK-modified nanogels efficiently delivered a model payload to the entire mucosa following the focal damage, suggesting utility of cell-penetrating peptide-mediated targeting for bladder drug delivery.

METHODS

Materials

CGKRK (Cys-Gly-Lys-Arg-Lys-amide) and KAREC (Lys-Ala-Arg-Glu-Cys-amide) were synthesized by solid-phase peptide synthesis. Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) was conjugated to the N-terminus via the 6-aminohexanoic acid linker. FITC labeled cysteine was conjugated using the same strategy. The final molecular weight of CGKRK and KAREC was 1062.5 Da and 1076.5 Da, respectively. The peptides were stored at −20°C in a dry form or reconstituted in DMSO at 10 mg/ml. BD Angiocath I.V. catheter (#381112) 24G was from BD Infusion Therapy Systems (Sandy, UT, USA). Dexamethasone phosphate and indomethacin were from Sigma. VECTASHIELD™ antifade mounting medium with DAPI was from Vector labs (Burlingame, CA, USA) and Permount™ mounting medium was from Thermo-Fisher (Waltham MA, USA). Corning Bio-Coat collagen-coated microplates were from Thermo Fisher, and heparin-coated microplates were from BioWorld (Dublin, OH, USA). 2-Hydroxyethyl acrylate (HEA), 2,2′-azobis(2-methylpropionitrile) (AIBN), triethylamine (TEA) 2-mercaptoethanol, and mercaptosuccinic acid were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO. Urethane dimethacrylate (UDMA) was donated by Esstech Inc., Essington, PA. All monomers and reagents were used as received.

Collagen and heparin binding

CGKRK and KAREC were diluted in PBS using 2-fold factor and added to collagen and heparin-coated wells (preblocked with 5% bovine serum albumin). The plates were incubated at room temperature for 1 h, washed 4 times with 200 μL PBS and scanned at 485 nm excitation and 515 nm emission wavelength using a SpectraMax M5 fluorescence plate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). The background (PBS) was subtracted from the data points, and the data were plotted with Prism. The data were fitted into linear regression curves or into non-linear (saturation kinetics) curves.

Fluorescence Uptake Quantification

The MB49 bladder carcinoma cell line was maintained in full DMEM medium with antibiotics and L-glutamine. Peritoneal macrophages were isolated by peritoneal lavage with ice cold PBS, washed and resuspended in full RPMI medium. Cells were seeded on 24-well plates for at least 24 h to let the cells grow to confluence. Each sample was done in triplicate. The cells were incubated with 1 mM of CGKRK and KAREC or PBS. After incubation, all wells were washed three times with PBS to wash off any free fluorescence molecules. Cells were detached from wells with trypsin at 37°C for 5 min. Triton X-100 (0.3% in PBS) was added to cells. After incubating for 30 min, the solution was centrifuged at 15,000 rpm (Eppendorf microcentrifuge) and the florescence intensity of the supernatant was measured using a fluorescence plate reader. For confocal imaging, cells were grown on glass chamber slides (NalgeNunc). Following the incubation experiment, cells were imaged with a Nikon A1R Confocal STORM super-resolution microscope.

Bladder injury and instillation

All animal experiments were performed in humane conditions approved by the University of Colorado IACUC (protocol 103913(11)1D). Specifically, 8 to 12-week-old female mice (C57BL/6 or BALB/c, Charles River Labs, Wilmington, MA) were anesthetized with isoflurane using a vaporizer machine at a flow rate of 1–3 L/min. Mice were placed on their backs, and the urethra opening was pulled forward while squeezing the bladder to express urine. A lubricated 24G Angiocath catheter without the needle was inserted via the urethra into the bladder cavity to wash the bladder once with 50μL PBS. In order to imitate injury following bladder cancer surgery, where the urothelium is damaged after removal of cancer tissues, the catheter tip was inserted completely and 5 circular motions were made in the apical part of bladder. Then, a 1mL syringe filled with 100μL of the peptide solution (0.3 mg/ml in PBS/20% DMSO) was attached to the catheter and approximately 50 μL of the solution was injected into the bladder until complete distension (determined by abdominal palpation). PBS was used as the dilution medium because of need to avoid pH dependent changes in FITC fluorescence. The catheter with an attached syringe was left in the bladder for 15 min. After the incubation, the peptide was removed via negative pressure, and the bladder was washed 5 times with PBS (completely filling the bladder each time). In order to take images of the bladder in situ, a Dino-Lite camera AM4113T-GRFBY model (AnMo Electronics Corp., Hsinchu, Taiwan) equipped with 480 nm (GFP) and 570 nm (Texas Red) excitation filters and 510 nm long pass and 610 nm long pass emission filters was used. The abdominal cavity was opened by incision, and that bladder was imaged at 20–40x magnification. The images were acquired at 1280 × 1024 resolution.

Histology of the bladders and image quantification

Freshly removed bladders were washed in PBS and snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen. The tissue was embedded in OCT media (manufacturer) and cryosectioned in 7-μm consecutive steps so that one section was placed on a slide for fluorescence imaging and the next section was placed on another slide for hematoxylin-eosin staining. The tissues on each slide were fixed in a 10% buffered formalin solution (Thermo-Fisher). The tissue was mounted with appropriate medium (VECTASHIELD™ antifade mounting medium with DAPI (Vector labs, Burlingame, CA, USA) for fluorescence imaging, or Permount™ medium (Thermo-Fisher) for H&E staining) and covered with coverslip. The bladders were images with a Nikon E600 upright fluorescence microscope with SPOT RT color camera. The images in each fluorescence channel were acquired under saturation as 12-bit gray TIFF, and H&E images were acquired as RGB images. Each low magnification image covering the entire bladder area was analyzed with ImageJ software (1.49v, 32 bit, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, USA). The background was subtracted with Process_Math_Subtract tool, and the integrated gray density per image was calculated using Measure tool. The intensities were plotted as individual values using Prism software (GraphPad, San Diego, USA).

Synthesis of HEA-UDMA nanogel

Nanogels were synthesized by a free radical solution polymerization reaction using 2-hydroxyethyl acrylate (HEA) and urethane dimethacrylate (UDMA) at a molar ratio of 85:15. HEA (5.83 g) and UDMA (4.17 g) were dissolved in 100 mL of 1:1, toluene/methanol mixture in a 500-mL round bottom flask. The thermal initiator AIBN (1 wt.%), and chain transfer agents (CTA) 2-mercaptoethanol (10 mol%) and mercaptosuccinic acid (10 mol%) were added to the above mixture and stirred at 85°C for 3 h. The reaction mixture was then precipitated via drop-wise addition to a ten-fold excess of hexane (1 L). The precipitate was filtered and the residual solvent removed under reduced pressure to isolate the nanogel.

CGKRK peptide was conjugated onto the HEA/UDMA nanogel via a thiol-acrylate Michael addition reaction between the cysteine group on the peptide and the acrylate functionality on the nanogel with triethylamine as the catalyst. Briefly, a 13-mg nanogel was dispersed in 10 mL PBS with 5 wt% DMSO. To the above mixture 100 μL of 10 mM CGKRK peptide stock solution was added along with 50-μL triethylamine and stirred under ambient conditions (22 °C) for 16 h. 2-mercaptoethanol (100 μL) was added to the reaction mixture to consume any unreacted acrylate groups within the nanogel and the reaction mixture was then dialyzed using a dialysis membrane (MWCO; 3.5KDa) against deionized water for 48 h and subsequently freeze-dried to obtain the CGKRK peptide-nanogel. For Rhodamine B loading, the CGKRK peptide-nanogel (10 mg) was dispersed in 6mL PBS with 20% DMSO along with 2mg Rhodamine B in a 50-mL round bottom flask and stirred under ambient conditions (22 °C) for 16 h. The mixture was dialyzed (dialysis membrane-MWCO; 3.5KDa) against deionized water for 48 h and then freeze-dried to obtain the Rhodamine B-loaded nanogel. A similar procedure was used to load Rhodamine B onto nanogels without the peptide and used as a control for the subsequent animal studies.

Nanogel characterization

Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (400 and 4000 cm−1, in mid-IR- NICOLET iS50 FTIR -Thermo Scientific, USA) was used to quantify the conversion of the (meth)acrylate during the nanogel synthesis by monitoring the (meth)acrylate group at 814 cm−1. Once the (meth) acrylate groups attained a conversion of 85%, the reaction was terminated so as to retain (meth)acrylate functionality to facilitate the subsequent CGKRK peptide conjugation via the thiol-acrylate Michael addition reaction. The molecular weight of the nanogel, as determined by gel permeation chromatography (GPC) with triple detectors (refractive index, right-angle light scattering, and differential viscometer- Viscotek-270) with tetrahydrofuran (0.35μL min−1) as the mobile phase was observed to be 13.5 kDa. The particle size and size distribution of the nanogels were determined by dynamic light scattering (DLS) using a Zetasizer NanoZS (ZEN 3600, Malvern, Germany) and was observed to have an average hydrodynamic diameter of 43.25 ± 1.15 nm. All size measurements were performed (n =3) on 0.1 mg/mL 5% DMSO/water mixture using glass cuvettes. The zeta potential across the nanogel dispersion at a concentration 5 mg/mL in 5% DMSO/water mixture was observed to be - 23.34 ± 0.034 mV.

Rhodamine B Release kinetics

A peptide conjugated nanogel (CGKRK -nanogel) and a control nanogel, both with rhodamine swollen into the network were evaluated in this study. The nanogels (2 mg) were dispersed in a solution of 4mL PBS with 0.5% DMSO and incubated at 37°C. The rhodamine released from the nanogels were quantified at regular time intervals (1h, 2h, 4h, 6 h and 24h) by measuring the fluorescence intensity at 625 nm (excitation wavelength 524 nm) using a microplate reader (Bio Tek, Synergy 4). Each data point represents the average of three observations.

RESULTS

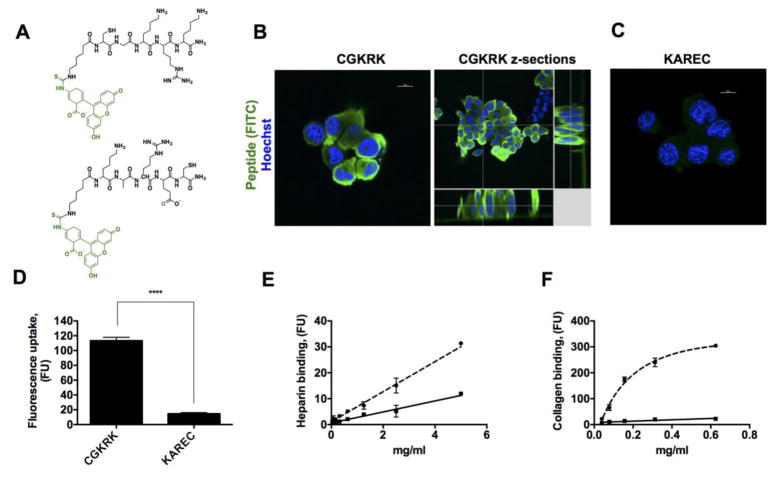

CGKRK is a tumor stroma and neovasculature binding peptide(15) that contains a highly basic sequence KRK, which is common to many cell penetrating peptides.(17) Initially, we tested cell-penetrating properties of CGKRK using MB49 murine urothelial carcinoma cells.(18) The peptide was labeled with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) via an aminohexanoic acid linker (Figure 1A), which served a dual purpose: a) to monitor the binding efficiency of CGKRK, and b) as a model “cargo drug molecule” ferried by CGKRK. As a control, FITC-labeled peptide KAREC without the cell-penetrating sequence (Figure 1A bottom) was utilized. As seen in the results from confocal microscopy (Figure 1B), the FITC labeled CGKRK peptide efficiently penetrated the cell membrane and accumulated in the cytoplasm inside the cells. The accumulation of CGKRK was not homogenous, with some cells not incorporating any fluorescence, while other cell clusters showed extremely efficient cytoplasmic accumulation (Figure 1B and Supplemental Figure 1). The reason is not clear but could be related to differences in status of the cell membrane. The control KAREC peptide did not show visible accumulation in the cells (Figure 1C). When quantified using fluorescence uptake measurements (Figure 1D), CGKRK accumulated in cells almost 10-fold more efficiently than KAREC. In addition, CGKRK, but not KAREC, showed efficient uptake by murine peritoneal macrophages (supplemental Figure 2). The binding of the peptides to heparin and collagen I, which are essential components of the cell membrane glycocalix and the extracellular matrix of the bladder mucosa,(19) was also evaluated. CGKRK and KAREC were added at concentrations ranging from 40 μg/ml to 625 μg/ml to heparin and collagen-coated plates. As seen in Figure 1E–F, CGKRK efficiently bound to both types of coatings with linear binding at concentrations below 300 μg/ml) while the KAREC binding to collagen and heparin was significantly lower than CGKRK.

Figure 1. Cell and stroma binding properties of CGKRK.

A) Peptides CGKRK (top) and KAREC (bottom) labeled with FITC via aminohexanoic acid linker were used in the study; B) Confocal microscope images of cellular uptake of peptides following incubation with MB49 bladder carcinoma cells. MB49 cells show high accumulation of CGKRK inside the cytoplasm; C) KAREC does not show appreciable accumulation in the cells; D) quantification of the peptide uptake by fluorescence spectroscopy. CGKRK showed significantly more accumulation in the cells than KAREC (p-value 0.0001, non-paired 2-tailed t-test, n = 3 replicates, repeated 3 times); F-F) Binding of CGKRK and KAREC to heparin and collagen type I, respectively. Solid line, KAREC; dotted line, CGKRK. Collagen binding of CGKRK shows saturation kinetics; the other data sets show linear binding. The experiment was done in duplicate and repeated 2 times. CGKRK shows more efficient binding to both heparin and collagen type I, which are the main components of bladder matrix and bladder mucosa.

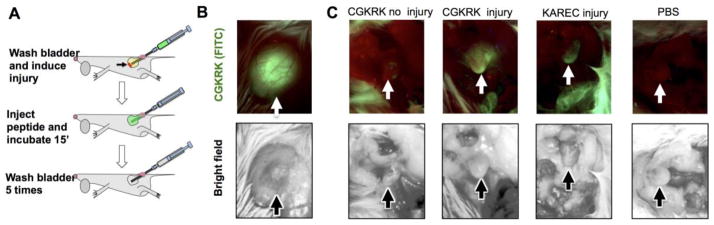

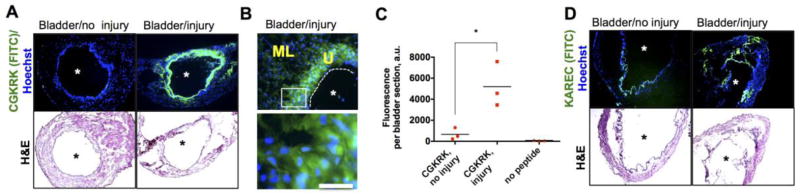

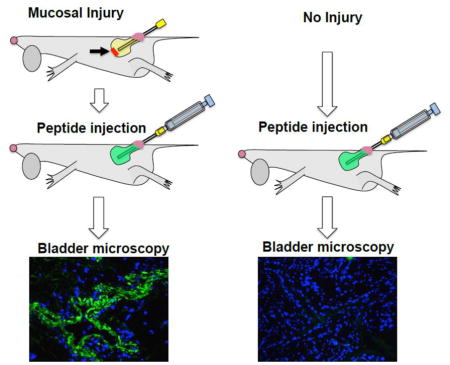

Encouraged by the efficient uptake by bladder epithelial cells and binding to the cell membrane and extracellular matrix components, we asked whether CGKRK could be a good candidate for injury-triggered bladder delivery. A catheter was introduced into bladders of anesthetized female mice via the urethra to scratch the apical layer of the bladder mucosa (Figure 2A). A peptide solution was administered intravesically until distension (~50 μL) and was kept inside for 15 min. We used a low magnification fluorescence microscope camera to monitor the changes in bladder fluorescence in situ. The completely filled bladder was highly fluorescent (Figure 2B). After voiding and washing the bladder, the images were taken again. As seen in Figure 2C, there was almost no residual fluorescence in the intact bladder, but a significant amount of fluorescence was present in the injured bladder. Notably, the fluorescence not only accumulated at the place of injury (bladder apex), but also was evenly distributed throughout the organ. Instillation of KAREC into the injured bladder resulted in less efficient binding than CGKRK, and the binding was mostly concentrated in the injured apex area (Figure 2C). Low magnification histological images corroborated the findings of in situ microscopy: there was little accumulation of CGKRK in the non-injured bladder, but a widespread accumulation of CGKRK in the urothelium of the injured bladder (Figure 3A). A high magnification image (Figure 3B) shows that CGKRK accumulated in all layers of the urothelium cells. Some penetration was also observed in the muscular layer. Quantification of fluorescence in the histological images (Figure 3C) showed that the injured bladder accumulated significantly more CGKRK than the non-injured bladder (p-value <0.05). Further, KAREC instilled into intact or injured bladders showed less binding than CGKRK and the fluorescence was concentrated in spots rather than being homogenously distributed around the lumen (Figure 3D). In addition, FITC-labeled cysteine did not show much penetration into injured bladder (Supplemental Figure 3).

Figure 2. Effect of mechanical injury on accumulation of peptides in the bladder.

A) Scheme of bladder injury of the apex via intravesical 24G catheter. Bladder was filled to distension with fluorescent peptide solution for 15 min and washed 5 times with PBS. Details of the procedure are provided in Methods. Images were acquired in situ through abdominal incision using Dino-Lite portable fluorescence microscope. Top image is fluorescence; bottom image is bright field; B) image of distended bladder filled with peptide solution; C) Images of bladders were taken in situ after peptide instillation and washing steps, but prior to bladder removal. There was no binding of CGKRK in the absence of focal injury, but efficient binding after the injury. KAREC showed limited binding in the apex (place of injury). There was no fluorescence in PBS treated bladders. All images were taken with the same exposure. Arrows point to the bladder apical region.

Figure 3. Histological analysis of peptide binding to the urothelium.

A) Low magnification (2x objective) images of entire bladders treated with CGKRK as described in Figure 2A. Upper image is fluorescence; lower image is the corresponding H&E staining (consecutive sections). There was widespread binding of CGKRK around the lumen (asterisk); B) High magnification (20x) objective of CGKRK treated bladder revealed accumulation of the peptide in the urothelium layer (U) and also some penetration in the muscle layer (ML). Cropped image below shows significant accumulation in the cells; C) FITC intensity in the bladder was quantified with ImageJ (p-value<0.05, non-paired two-tailed t-test, 3 sections per group). The experiment was repeated 3 times; D) low magnification (2x objective) images of entire bladder treated with KAREC show some fluorescence deposition in the area of injury, although it was less efficient and less widespread than CGKRK. Asterisk marks bladder lumen, and dotted line delineates the urothelium/lumen boundary. Size bar = 200 μm.

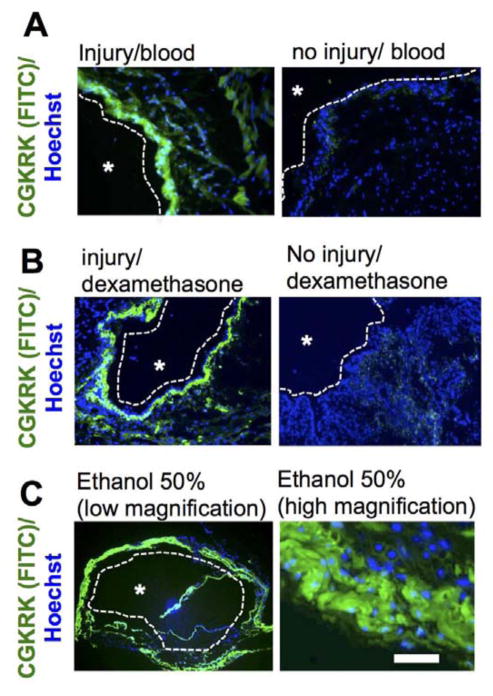

In order to further understand mechanisms of injury-triggered binding to the urothelium, the following set of experiments were performed. To test the possibility that intravesical bleeding following injury triggered the enhanced binding of the CGKRK peptide, mouse blood (treated with EDTA as an anticoagulant) was mixed together with CGKRK and the mixture was administered intravesically into either intact or injured bladders. As seen in Figure 4A, there was no binding of CGKRK to the urothelium in the absence of injury, suggesting that intravesical bleeding alone is unlikely to trigger the enhanced binding. To test whether acute inflammatory response after mechanical urothelium cell injury(20) was responsible for the phenomenon, mice were pretreated with dexamethasone solution in saline by subcutaneous injection (10.55 μg/mouse) 2 h prior to the intravesical injury and CGKRK administration. According to Figure 4B, the delivery of CGKRK to dexamethasone-pretreated mice did not block the widespread binding of the peptide to the injured bladder. Therefore, this set of data suggests that acute inflammatory response induced by the injury is not responsible for the CGKRK binding. Ethanol and acid are known to induce loss of urothelial barrier function.(6, 7) To test the hypothesis that chemical injury of the urothelium in the absence of mechanical injury is responsible for the observed enhanced binding of the CGKRK peptide, mice were intravesically instilled with 50% ethanol prior to delivery of the CGKRK peptide. As shown in Figure 5C, these treatments resulted in widespread binding of the peptide and accumulation inside the cells and penetration into the stroma, suggesting that loss of the urothelium barrier is important for enhanced binding.

Figure 4. Investigation of mechanisms of injury-induced accumulation of CGKRK.

A) CGKRK was mixed with EDTA-treated blood and administered intravesically. Low magnification images (10x objective) show the lumen, urothelial and muscular layers. Blood did not induce the binding in the absence of injury, suggesting that bleeding caused by the injury per se is not responsible for the widespread binding; B) Mice were pretreated with anti-inflammatory agent dexamethasone prior to injury. Pretreatment did not block injury-induced binding of CGKRK; C) chemical disruption of the urothelium barrier with ethanol resulted in widespread accumulation of CGKRK, suggesting that loss of the barrier’s function is required for CGKRK binding. Low magnification = 2x objective; high magnification = 20x objective (cropped image). An asterisk marks bladder lumen in all images. A dotted line delineates the urothelium/lumen boundary. Size bar = 200 μm.

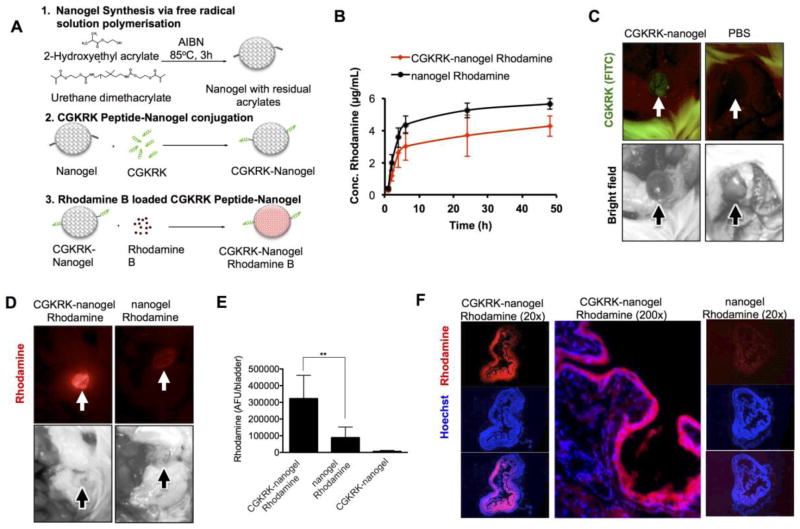

Figure 5. Targeting of nanogel loaded Rhodamine to the bladder.

A) Synthesis of nanogel, CGKRK-nanogel and CGKRK-nanogel Rhodamine B. Full description of the synthesis is in Methods section; B) Release profile of Rhodamine B from plain nanogel and CGKRK-nanogel. CGKRK-nanogel shows a slightly slower release rate than plain nanogel, likely due to additional mesh that delays the exit of the rhodamine from the nanogel. The difference was not statistically significant. C) Administration of CGKRK-nanogel (without Rhodamine B) to the focally injured bladder results in FITC fluorescence accumulation (arrow); D) Administration of Rhodamine B-loaded nanogel to the focally injured bladder results in Rhodamine B fluorescence for CGKRK-nanogel Rhodamine (left), but not for non-targeted nanogel Rhodamine B (right). FITC fluorescence is not shown due to an overwhelming bleed through of Rhodamine B into the FITC channel; E) quantification of Rhodamine B fluorescence shows significantly higher accumulation for the CGKRK-nanogel Rhodamine B (n=5 for targeted nanogel, n=6 for non-targeted nanogel Rhodamine B, n=2 for CGKRK-nanogel (empty), p-value 0.0049, parametric 2-sided t-test); F) histological sections of the nanogel-treated bladders show widespread accumulation of Rhodamine fluorescence in the bladder treated with CGKRK-nanogel Rhodamine B but not in the bladder treated with nanogel Rhodamine B.

Lastly, we set out to test the ability of CGKRK to promote delivery of larger cargo to the injured urothelium. Previously,(21) we synthesized and characterized a nano-sized gel (nanogel (22)) consisting of co-polymers of 2-hydroxyethyl acrylate and urethane dimethacrylate (Figure 5A). The 3-dimensional cross-linked network, which can be swollen, enables a high loading ratio of drugs.(21) The nanogels were conjugated with CGKRK (Figure 5A) at approximately 2 peptides per polymer chain and subsequently was loaded with Rhodamine B resulting in 4.64% w/w incorporation efficiency. The control nanogel without rhodamine released 24% of the loaded rhodamine within 48 h, whereas only 18% of the rhodamine was released from CGKRK-nanogel rhodamine in the same time frame (Figure 5B). The bladders were induced with a focal catheter injury as described above and the control nanogel (rhodamine), CGKRK-nanogel (rhodamine) and CGKRK-nanogel (empty) were instilled, washed and imaged with a low magnification microscope. As shown in Figure 5C, the instillation of CGKRK-nanogel (empty) resulted in a detectable signal of fluorescein in the bladder. The signal was much lower than that after instillation of free CGKRK (Figure 2C) due to a much lower amount of fluorescent peptides being instilled with the CGKRK-nanogel formulation. CGKRK-nanogel (rhodamine) produced a widespread accumulation of rhodamine in the entire bladder lumen (Figure 5D–E), whereas non-targeted nanogel showed a significantly lower level of fluorescence (Figure 5D–E). Histological examination of the bladders revealed an intense accumulation of rhodamine in the entire bladder lumen, with some fluorescence penetrating beyond the mucosal layer (Figure 5F), whereas non-targeted nanogel showed minimal rhodamine signal in the bladder.

DISCUSSION

We have demonstrated that focal mechanical injury to the bladder mucosa opens up the barrier to binding and penetration of cell-penetrating peptide CGKRK to the entire urothelium. The experiments suggest specificity of the binding of CGKRK towards injured mucosa. The conclusions are based on the experiments that showed that firstly, CGKRK has shown significantly more binding to the injured than to intact bladders. Secondly, CGKRK has better binding efficiency than KAREC when it comes to ECM binding and cell-penetrating properties. In the future, it would be interesting to test other cell penetrating peptides for improved delivery to injured mucosa. A recent report described that CPP derived from the tat domain of HIV(17) improves delivery of therapeutic proteins and nucleic acids to the bladder.(8, 9) Moreover, the ability of other CPPs to bind bladder urothelium has been reported.(10, 11)

We limited the study to 15 min incubation in the bladder. Typically, for urinary cystitis or other diseases in which catheter instillation of a therapeutic is an option, the patient has a catheter inserted using sterile techniques to drain the bladder, after which medication is instilled into the bladder via the catheter, and the catheter is then clamped for about 15–20 minutes. At the end of the treatment, the patient is released and allowed to void the bladder if needed. The washes in our experiments were intended to mimic the washout of the compounds by voiding. In the future, studies to understand the long-term retention of therapies will need to be performed.

The major significance of the results reported here is in demonstrating feasibility of delivery to the injured bladder urothelium via nano-sized carriers. For example, the observed widespread binding of the peptide to the entire urothelium surface could have a significant impact on the efficiency of current therapies for bladder cancer. As large percentage of relapses are in the areas distant from the primary tumor due to the “field effect,” or the presence of tumor cells not removed by the surgery,(23) the ability of the peptide to function as a drug delivery conduit can be used to deliver chemotherapy and immunotherapy towards eradicating cells and improve treatment outcomes. Likely, other conditions manifested by mucosal injury, such as interstitial cystitis, or cyclophosphamide(24) and irradiation(25) induced cystitis can also benefit from the proposed targeting approach. Indeed, in view of increased interest in effective delivery of supramolecular carriers and hydrogels to the bladder pathologies, (26, 27) the use of CPP-coupled nano- and microcarriers could offers exciting possibilities in management of acute and chronic disease of bladder mucosa. The focal catheter injury is used to mimic the pathological conditions wherein the mucosa is injured. This method of drug delivery will be applied to bladders with preexisting urothelial injuries, hence no additional damage to improve delivery will be done. Further disease-specific studies will have to be undertaken to establish if this delivery system can be used for long-term therapy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: NIH CA167524, CA194058-01A1 to DS.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Lavelle J, Meyers S, Ramage R, Bastacky S, Doty D, Apodaca G, et al. Bladder permeability barrier: recovery from selective injury of surface epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2002;283:F242–53. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00307.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Negrete HO, Lavelle JP, Berg J, Lewis SA, Zeidel ML. Permeability properties of the intact mammalian bladder epithelium. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:F886–94. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1996.271.4.F886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Giannantoni A, Di Stasi SM, Chancellor MB, Costantini E, Porena M. New frontiers in intravesical therapies and drug delivery. Eur Urol. 2006;50:1183–93. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2006.08.025. discussion 93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tyagi P, Tyagi S, Kaufman J, Huang L, de Miguel F. Local drug delivery to bladder using technology innovations. Urol Clin N Am. 2006;33:519-+. doi: 10.1016/j.ucl.2006.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen D, Song D, Wientjes MG, Au JL. Effect of dimethyl sulfoxide on bladder tissue penetration of intravesical paclitaxel. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:363–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Engler H, Anderson SC, Machemer TR, Philopena JM, Connor RJ, Wen SF, et al. Ethanol improves adenovirus-mediated gene transfer and expression to the bladder epithelium of rodents. Urology. 1999;53:1049–53. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(98)00641-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hauser PJ, Buethe DA, Califano J, Sofinowski TM, Culkin DJ, Hurst RE. Restoring barrier function to acid damaged bladder by intravesical chondroitin sulfate. J Urol. 2009;182:2477–82. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gao XF, Feng JF, Wang W, Xiang ZH, Liu XJ, Zhu C, et al. Pirt reduces bladder overactivity by inhibiting purinergic receptor P2X3. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7650. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tyagi P, Banerjee R, Basu S, Yoshimura N, Chancellor M, Huang L. Intravesical antisense therapy for cystitis using TAT-peptide nucleic acid conjugates. Mol Pharmaceut. 2006;3:398–406. doi: 10.1021/mp050093x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hsieh JT, Zhou J, Gore C, Zimmern P. R11, a novel cell-permeable peptide, as an intravesical delivery vehicle. Bju International. 2011;108:1666–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2011.10185.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee SM, Lee EJ, Hong HY, Kwon MK, Kwon TH, Choi JY, et al. Targeting bladder tumor cells in vivo and in the urine with a peptide identified by phage display. Mol Cancer Res. 2007;5:11–9. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-06-0069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stewart BW, Wild C International Agency for Research on Cancer, World Health Organization. World cancer report 2014. Lyon, France Geneva, Switzerland: International Agency for Research on Cancer WHO Press; 2014. p. xiv.p. 630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Teichman JM, Parsons CL. Contemporary clinical presentation of interstitial cystitis. Urology. 2007;69:41–7. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2006.08.1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parsons CL. The role of a leaky epithelium and potassium in the generation of bladder symptoms in interstitial cystitis/overactive bladder, urethral syndrome, prostatitis and gynaecological chronic pelvic pain. BJU Int. 2011;107:370–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09843.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoffman JA, Giraudo E, Singh M, Zhang L, Inoue M, Porkka K, et al. Progressive vascular changes in a transgenic mouse model of squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Cell. 2003;4:383–91. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00273-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Agemy L, Kotamraju VR, Friedmann-Morvinski D, Sharma S, Sugahara KN, Ruoslahti E. Proapoptotic peptide-mediated cancer therapy targeted to cell surface p32. Mol Ther. 2013;21:2195–204. doi: 10.1038/mt.2013.191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Copolovici DM, Langel K, Eriste E, Langel U. Cell-penetrating peptides: design, synthesis, and applications. ACS Nano. 2014;8:1972–94. doi: 10.1021/nn4057269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen F, Zhang G, Cao Y, Hessner MJ, See WA. MB49 murine urothelial carcinoma: molecular and phenotypic comparison to human cell lines as a model of the direct tumor response to bacillus Calmette-Guerin. J Urol. 2009;182:2932–7. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aitken KJ, Bagli DJ. The bladder extracellular matrix. Part I: architecture, development and disease. Nat Rev Urol. 2009;6:596–611. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2009.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Elwood CN, Lange D, Nadeau R, Seney S, Summers K, Chew BH, et al. Novel in vitro model for studying ureteric stent-induced cell injury. BJU Int. 2010;105:1318–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2009.09001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saraswathy M, Stansbury J, Nair D. Water dispersible siloxane nanogels: a novel technique to control surface characteristics and drug release kinetics. Journal of Materials Chemistry B. 2016;4:5299–307. doi: 10.1039/c6tb01002d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chacko RT, Ventura J, Zhuang J, Thayumanavan S. Polymer nanogels: a versatile nanoscopic drug delivery platform. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2012;64:836–51. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2012.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hafner C, Knuechel R, Zanardo L, Dietmaier W, Blaszyk H, Cheville J, et al. Evidence for oligoclonality and tumor spread by intraluminal seeding in multifocal urothelial carcinomas of the upper and lower urinary tract. Oncogene. 2001;20:4910–5. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Philips FS, Sternberg SS, Cronin AP, Vidal PM. Cyclophosphamide and urinary bladder toxicity. Cancer Res. 1961;21:1577–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Browne C, Davis NF, Mac Craith E, Lennon GM, Mulvin DW, Quinlan DM, et al. A Narrative Review on the Pathophysiology and Management for Radiation Cystitis. Adv Urol. 2015;2015:346812. doi: 10.1155/2015/346812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zacche MM, Srikrishna S, Cardozo L. Novel targeted bladder drug-delivery systems: a review. Res Rep Urol. 2015;7:169–78. doi: 10.2147/RRU.S56168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Janicki JJ, Gruber MA, Chancellor MB. Intravesical liposome drug delivery and IC/BPS. Transl Androl Urol. 2015;4:572–8. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2223-4683.2015.08.03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.