Women in jail are typically women of color who live in poverty, lack marketable job skills, and suffer from mental health and substance use problems (Lynch et al. 2012; Zierler and Krieger 1997). Over the past two decades, these women have been among the proportionately fastest-growing subgroups in America’s correctional population (Glaze 2010), reflecting the overall increasing number of women entering penal institutions and the overall decreasing number of people incarcerated. Female detainees are commonly held in jail for only a few weeks or months or sentenced for up to one year (Elias and Ricci 1997). Therefore, female detainees released from jail (as opposed to female inmates released from prison) constitute the majority of criminally involved women reentering the community from carceral settings. Nonetheless, women released from jail (Scott et al. 2014) generally receive fewer services than women released from prison (Staton-Tindall et al. 2011).

Despite the high concentration of substance-abusing women in jails, most research on substance use relapse and criminal recidivism among female offenders has focused on women returning from prison rather than from jail (Staton-Tindall et al. 2011). In light of the sheer number of formerly detained women and the raft of behavioral healthcare problems among them, more studies should be conducted to understand better how to incorporate substance use disorder (SUD) treatment and recovery services into community reentry planning. Undeniably, recovery-enhanced reentry services can improve a wide range of outcomes for criminally involved women with substance use disorders (Lynch et al. 2012; Scott and Dennis 2012). The present study was conducted to advance knowledge about reentry programming for formerly detained women. The study’s sample consisted of women who received substance abuse recovery and probation services after discharge from a large urban jail.

Addiction and its Correlates

Nearly 70% of women in jail, on average, report weekly use of alcohol or illegal substances in the month before their latest arrest (e.g., Adams et al. 2008, 2011; Bureau of Justice Statistics 2005). In contrast, women in the community only report past month rates of 51% for any alcohol use, 3.2% heavy alcohol use and 7.7% any illicit drug use (SAMHSA, 2015). Women with substance use problems and criminal involvement share common backgrounds that include trauma, family histories of addiction, child custody issues, involvement in the sex trade, homelessness, single parenthood, and a host of other social and psychological problems (Alemagno, 2001; Belenko et al. 2004; Bloom et al. 2004; Teplin et al. 2003; Young et al. 2008). These women are often subjected to violence and can experience symptoms of PTSD and other forms of emotional distress that further undermine their ability to achieve and sustain recovery from substance use disorders (DeHart 2008). Studies have shown that more than 90% of such women are sexually active (e.g., Young et al., 2008; Scott et al in press).

Between 2001 and 2010, rates of AIDS-related deaths declined an average of 16% per year among state and federal prisoners, from 24 deaths per 100,000 in 2001 to 5 per 100,000 deaths in 2010. In fact, the HIV/AIDS mortality rate among state prison inmates dipped below the rate in the general population, 6 per 100,000 versus 7 per 100,000, respectively (Maruschak, 2012). Nonetheless, many women in jail have been forced or coerced into having unprotected sex or trading sex to survive financially (Stevens et al. 1995). These behaviors place female offenders at risk for reincarceration and render them twice as likely as male offenders, and more than 7 times as likely as women in the general population, to have HIV/AIDS (CDC 2004; De Groot 2000; Fogel and Belyea 1999; Grella et al 2000; Khan et al. 2008; Maruschak 2004; McClellan et al 2002; Yard, 2015). A meta-analysis concluded that 1 in 7 people with HIV are held in jails or other correctional facilities (Iroh et al., 2015). Among jail populations, African American women are more than twice as likely to be diagnosed with HIV as white or Latino women (Minton and Golinelli 2014). Moreover, researchers have found that HIV-risk behaviors significantly increase the likelihood that female detainees will engage in criminal behaviors following release from jail (e.g. Scott et al. 2014). Jails provide opportunities for female detainees to engage in services (i.e., testing, counseling, and treatment) that particularly reduce their risk for HIV exposure as well as risky drug use and sexual activities.

Reentry Challenges and Services

Behavioral healthcare problems and their social, economic, and medical sequelae prevent successful reintegration for female releasees (Singer et al. 1995). Female detainees exiting jail are more likely than their male counterparts to be illicit drug users, homeless, and single parents. They are also more likely than men to be arrested for drug law violations and to suffer from medical conditions (Freudenberg et al. 2007). Without reentry programming, female releasees with substance use disorders are at high risk for subsequent arrests and detentions (Grella and Greenwell 2007; Oser et al. 2009; Singer et al. 1995). In contrast, participation in post-release treatment can improve and sustain a healthy adjustment and recovery among female detainees, including women on probation or in other types of community-supervision programming (Guydish et al. 2011; Taxman et al. 2007; Wexler et al. 2004). Nevertheless, only one-third of jail-based drug-treatment programs refer released women to community-based treatment, and only one-fourth of such programs assist them in obtaining recovery services (Taxman et al. 2007).

As noted above, women’s pathways into crime differ from those of men. These differences are a function of gender-specific risks and criminogenic needs (Blitz et al 2005; King & Foley, 2014). Female offenders are more likely than male offenders to enter the criminal justice system with histories of intimate partner violence and other traumatic experiences, which can propel them into illegal activities such as drug use and sexual exchanges. According to marginalization theory, women’s criminality commonly stems from relationship issues, including victimization at the hands of caretakers or partners, which exacerbates drug use and co-occurring psychiatric disorders and fosters unhealthy interpersonal dynamics that can create and accompany opportunities for crime (Chesney-Lind 1986). These issues typically persist unless they are addressed in gender-responsive programming after women are released from confinement (King and Foley 2014; Ney, et al. 2012).

Recovery Management Checkups

Half of the women in the present study were randomly assigned to receive an innovative intervention for substance use disorders known as ‘Recovery Management Checkups’ (RMCs) (Scott and Dennis 2008). Based on a public health model of monitoring and early reintervention, RMC was developed and tested to reduce the time from relapse to treatment reentry and prolong recovery (e.g., Dennis et al. 2003a; Dennis and Scott 2012; Scott et al. 2005; 2011; Scott and Dennis 2009). The current research examined RMCs as a long-term care and supervisory strategy for female releasees with substance use disorders and HIV risk. The RMC model is based on a public health model in which ongoing monitoring and prompt reintervention can detect and halt impending relapse, reduce the time to treatment readmission, and improve participants’ outcomes (Scott and Dennis 2011). RMC linkage managers facilitate connections to treatment and employ engagement and retention protocols to assist clients in obtaining long-term recovery care (Scott and Dennis 2008).

The RMC model has been tested in two large clinical trials of men and women who had participated in substance abuse treatment in the community. In the first trial (Dennis et al. 2003a; Scott et al. 2005), half of the participants were randomly assigned to receive quarterly RMCs for two years (the treatment group), while the other half received an assessment only (the control group). Members of the RMC group experienced less time between relapse and treatment reengagement, increased abstinence and rates of recovery, and lowered rates of HIV-risk behavior and recidivism compared with members of the control group.

In the second trial (Dennis and Scott 2012; McCollister et al. 2013; Scott and Dennis 2009; 2011), participants received quarterly RMCs for four years. Compared with those in the assessment-only (control) group, participants in the RMC group similarly experienced less time between relapse and treatment reengagement, increased abstinence from substance use, and higher recovery rates. The reduced costs associated with subsequent crimes and criminal justice processing (e.g., reincarceration) completely offset the costs of RMC. The second trial, which was better implemented than the first, had larger effects over the first two years (Scott and Dennis 2009). In both studies, the magnitude of RMC’s effects increased with each quarterly intervention over time (Scott and Dennis 2011).

Specialized Probation for Women

More than 80% of all adults under community correction supervision are on probation (Maruszhak and Bonczar 2014). Women comprised 25% of the adult probation population in 2013 (Herberman and Bonczar 2015). Many jurisdictions have specialized supervision programs for female probationers. More than 74% of the women participating in this investigation were on probation at some time during the three years post-release: 30% at the time of release from jail, and an average of 44% in any given quarter. Most of these women were enrolled in a specialized probation supervision program known as Promotion of Women through Education and Resources (POWER; Lurigio et al. 2007). The unit’s probation officers are specially trained to monitor small caseloads of women who are transitioning from drug treatment in the Cook County Jail’s Department of Women’s Justice Programs (DWJP) to probation-based reentry services in the community.

POWER helps women change their lives by referring them to community-based services that address their addiction- and trauma-related needs, motivating and preparing them to continue their participation in intensive mental health and substance abuse treatments (Lurigio et al. 2004; 2007). In addition, the “Moving On” cognitive behavioral curriculum supplements individual in-office dialogues between POWER clients and probation officers (Lurigio et al. 2004; 2007). Research has shown that women in the POWER program were less likely to be arrested for a new crime while on probation supervision than were women on standard probation (Lurigio et al. 2007). POWER probation officers “reach into” Department of Women’s Justice Programs in order to prepare women for participation in services after they are sentenced to probation.

A formal bridging mechanism was established to ensure that women who completed drug treatment in Department of Women’s Justice Programs and received a sentence to probation were transferred to the POWER program as a condition of their probation. This process created continuity in supervision and drug treatment services for women released from Department of Women’s Justice Programs and sentenced to probation (Lurigio et al. 2007). For example, POWER is sensitive to women’s struggles with parenting and childcare, histories of trauma, co-occurring substance use disorders and other psychiatric problems, and housing and financial challenges (Lurigio et al. 2007). The present study examined the independent and interactive effects of RMCs and specialized probation supervision (i.e., the POWER program).

Current Research

This article presents the main findings of the third trial of the RMC model (Scott et al. 2012; 2014) which was tested with a sample of 480 female offenders referred from jail or furlough-based programs to community-based substance abuse treatment. Half of the offenders were randomly assigned to a control group (interviews monthly for 90 days and quarterly for three years post-release), while the other half received the same interviews plus RMC in two phases. During the first 90 days following release from jail, women randomly assigned to the RMC condition were significantly more likely than those assigned to the control condition to return to treatment sooner and to participate in substance abuse treatment at any time during the follow-up period. Women who received any treatment were significantly more likely than those who received none to abstain from alcohol or other drug use. Those who were abstinent were significantly less likely to engage in HIV-risk behaviors and to be rearrested (Scott and Dennis 2012). This article presents the results of the subsequent three-year, post-release period.

In addition to extending the follow-up period, the present study explored the interaction between specialized probation supervision and RMCs and incorporated additional outcome data, including urinalysis findings and official arrest records. The current investigation tested the direct effects of specialized probation supervision (POWER) as a subject variable (i.e., stratum) and RMCs as an experimental intervention (within stratum) on community-based treatment utilization, self-help participation, HIV-risk behaviors, criminal recidivism, and substance-use problems and relapse. To establish temporal order, predictor variables were measured at the beginning of a given quarter and outcome variables were measured at the end of the next quarter. To minimize measurement error, several sources of information (e.g., self-report, urinalysis, official arrest records) were combined and the worst outcome within each category (e.g., drug relapse and criminal recidivism) was used in the analyses. Finally, the indirect effects of self-help activities, substance abuse treatment, HIV-risk behaviors, and alcohol and drug use (in the prior quarter) were tested on any new crime, arrest, or incarceration (in the subsequent quarter).

Method

Recruitment Site

As noted above, participants were recruited from Department of Women’s Justice Programs in Cook County Jail. Located on 96 acres in the city of Chicago, Cook County Jail houses an average of 10,000 detainees daily and is one of the largest single-site jails in the United States (Olson 2013). Women constitute nearly 13% of Cook County Jail’s population and are charged primarily with drug, property, domestic violence, driving under the influence, traffic, and prostitution offenses (Escobar and Olson 2012). Department of Women’s Justice Programs operates one of the country’s largest jail-based substance use treatment programs for women; the program includes both jail-based (residential) and furlough-based (outpatient) treatment options for nonviolent female detainees with drug problems (Scott and Dennis 2012). To reiterate, Department of Women’s Justice Programs primarily funnels women sentenced to probation into a specialized probation unit entitled “POWER.”

Target Population and Participant Eligibility

The target population for this trial consisted of adult women with substance use disorders reentering the community from Department of Women’s Justice Programs’s residential and outpatient substance abuse treatment programs. Eligibility was determined in two stages. In the first stage, women were deemed ineligible if they had not used substances in the 90 days before incarceration, had no substance use disorder symptoms, were under age 18, lived or planned to move outside Chicago within the next 12 months, were not fluent in English or Spanish, were cognitively unable to provide informed consent, or were released before the 14th day of incarceration. In the second stage, only women released to the community—as opposed to those sentenced to prison or placed in other institutions where the intervention could not be implemented—were invited to participate in the experiment.

Sample Size and Power

Based on previous studies (Dennis et al. 2003a; 2012; Scott and Dennis 2009; 2011), the proposed sample size was 425 women. This sample size was derived in order to achieve 80% power in a two-tailed test, with p < .05 for two-group effect sizes of .36 (or more) predicated on increasing levels of treatment participation and at least a 90% follow-up rate (Dennis et al. 1997). The sample size was increased to 480 to allow for more refined subgroup analyses.

Randomization

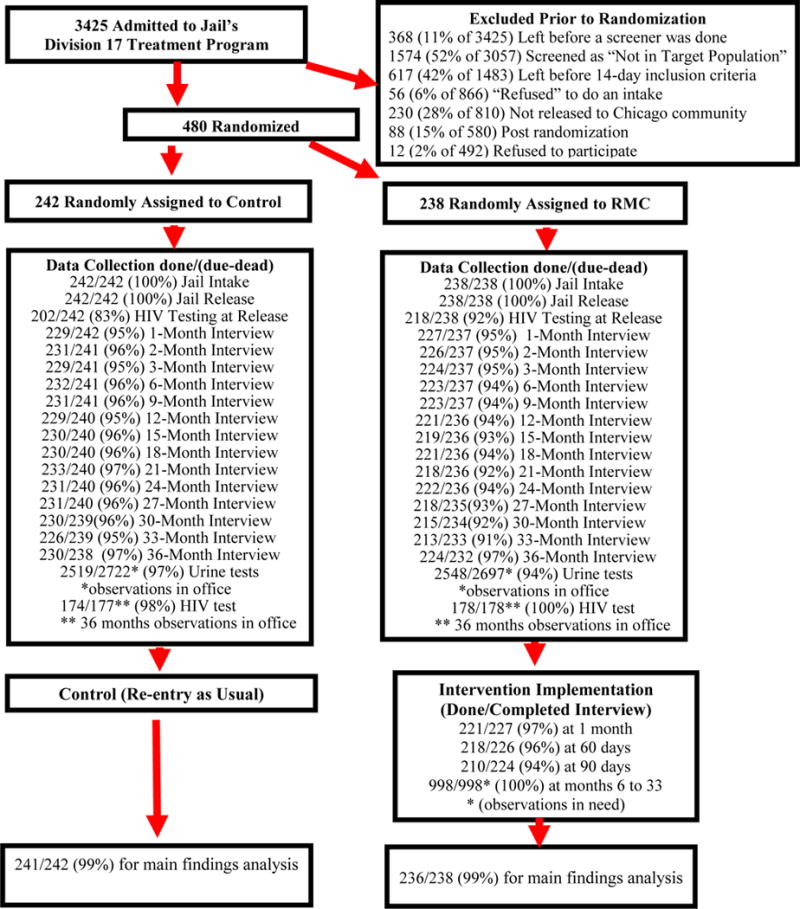

Women who were eligible at baseline and released to the community were randomly assigned by the research coordinator using gRand Urn Randomization, Version 1.10 (Charpentier 2003) to either the RMC or the control condition with a base rate of 50% to each condition (Figure 1). Urn randomization was used to balance the characteristics of the women by group on age (under 35 vs. 35+), race (African American vs. other race), substance abuse treatment (prior vs. none), jail-based services (residential vs. furlough [outpatient]), and high scores (i.e., 3+ vs. 0–2 past-year symptoms/behaviors) on each of the study’s screener tools: substance use disorder, HIV-risk behavior, internalizing disorder, externalizing disorder, and crime/violence. The order and balance of randomization were checked, and no violations of randomization or significant differences were found, by condition, on any of the Urn Randomization variables.

Figure 1.

RMC WO Experiment CONSORT Chart

Experimental RMC Condition

Women assigned to the experimental condition received RMCs (Scott and Dennis 2008). These women met with Linkage Managers after completing each research interview at release: 30, 60, and 90 days post-release and quarterly thereafter for up to 36 months. The Linkage Managers used motivational interviewing (MI) techniques to address current substance use, HIV-risk practices, or criminal activity; to discuss the barriers to desistence and strategies to refrain from those behaviors; and to assess participant’s motivation for change.

For the women in the RMC condition who reported substance use, Linkage Managers scheduled appointments for substance abuse treatment. If a woman reported that she was thinking of leaving substance abuse treatment or failed to keep a treatment appointment, the treatment staff contacted the Linkage Managers to arrange an intervention in an effort to reengage the client in programming. When women in the RMC condition reported no involvement in any of the three problematic behaviors, Linkage Managers would discuss with them the constructive life changes emanating from recovery (e.g., spending time with family).

In their monthly linkage meetings during the first 90 days post-release, RMC participants received a modified, gender-focused intervention to reduce their risk of HIV (Wechsberg et al. 2004). The intervention consisted of an assessment of HIV-risk behaviors, HIV knowledge, and condom self-efficacy; an introduction to HIV-related health conditions and health promotion strategies (assertive communication, self-empowerment, and avoidance of violent and other unsafe situations); referrals for substance abuse and HIV treatment; and the provision of male and female condoms. The linkage meetings focused on discussions about maintaining recovery and minimizing high-risk behaviors and were audiotaped.

To maintain intervention quality, a Motivational Interviewing National Trainer (MINT) trained and certified all Linkage Managers. Following certification, one audiotape per week for each Linkage Manager was randomly sampled, reviewed and rated by the trainer, tapering down to one every other week. The two primary Linkage Managers’ performance was exemplary as they averaged between 4.0 and 4.7 on a 5-point scale on ratings using revised versions of global scales for the five areas that reflect the essential principles of motivational interviewing: Evocation, Collaboration, Autonomy/Support, Direction, and Empathy (Moyers et al. 2010). Tracking of interviews and RMC follow-up relied on a highly effective model that was specially developed for longitudinal studies of people with substance use disorders (Scott 2004). All interview staff were trained in these assessments, interventions, and tracking protocols.

Probation Supervision

As noted above, more than 74% of the women participating in this investigation were on probation at some time during the 3 years post release: 30% at the time of release from jail, an average 44% in any given quarter. Among women on probation, the average time on probation was 73 days during the past quarter and 1.5 years across the 3 year study. The latter included people who were left-censored (i.e., on probation when they entered jail) or right-censored (still on probation when the study ended). Although some women were sentenced to standard probation supervision, for the past decade and explicitly during the period of this investigation, the majority of the women sentenced to probation upon release from Department of Women’s Justice Programs were placed into the POWER specialized probation program describe above and elsewhere (Lurigio et al. 2007).

Outcome Measures

The primary proximal outcome for this study was increasing the rate of treatment participation (any and 10+ days) in the coming quarter. We were also interested in the extent to which probation and RMC affected other distal outcomes, including self-help involvement, substance use, HIV-risk behaviors, and recidivism. Table 1 presents the definitions of each outcome measure and includes their interclass correlation coefficient (ICC) across quarters to demonstrate the substantial variation necessary for repeated observation analyses. Outcomes were based on a combination of interviews with a modified version of the Global Appraisal of Individual Needs (GAIN) (Dennis et al. 2003b), urinalysis, and official arrest records. All interviewers were trained and certified on the use of the GAIN, and all interviews were digitally recorded. A random sample of 10% of the interviews was reviewed for quality assurance (see Titus et al. 2012).

Table 1.

Definition of Key Measures

| On Probation (Interclass Correlation Coefficient [ICC] of individuals over time = .49): Yes/No (1/0) On probation or other form of community supervision for the complete 90 days of the prior quarter. |

| Recovery Management Checkups (RMC; ICC=1.00): Yes/No (1/0) Randomized to RMC at discharge or not (happened prior to the quarter). |

| Any Substance Abuse Treatment (ICC = .17): Yes/No (1/0) Self-reported any days of treatment reported during the quarter. |

| More Than 10 days of Treatment (ICC = .16): Yes/No (1/0) Self-reported more than 10 days of treatment during the quarter. |

| Any Self-help Involvement (ICC = .44): Yes/No (1/0) A score of 1+ on the Self-help Involvement Scale (18 items alpha = .97). Days of self-help meetings attended, behaviors associated with engaging in self-help, and whether the person was “affiliated” with one or more self-help groups (Conrad, et al, in press). |

| High Self-help Involvement (ICC = .49): Yes/No (1/0) Endorsed 11+ items on the Self-help Involvement Scale. |

| Weekly Alcohol or Other Drug Use (ICC = .49): Yes/No (1/0) Self-reported weekly alcohol and/or drug use in the quarter. |

| Any Unprotected sex (ICC = .34): Yes/No (1/0) Self-reported any unprotected sex during the quarter. |

| Any HIV-Risk Behaviors (ICC = .33): Yes/No (1/0) Self-reported 1 or more of the following during the quarter: unprotected sex, having multiple sex partners, sex trading, been victimized, currently worried about being victimized, needle use, or needle sharing. |

| Any New Crimes (ICC = .13): Yes/No (1/0) Self-reported property, drug or violent crime during the quarter. |

| Any New Arrest or Incarceration (ICC = .13): Any new arrest, charges or incarceration from three sources: Cook County Jail’s, Incarceration Management and Cost (CCJ-IMAC) system; the State of Illinois’ Law Enforcement Agencies Data System (IL-LEADS); and self-reports during follow-up on the Global Appraisal of Individual Needs (GAIN). The kappa among all three sources was .63 |

| Any New Crimes, Arrests or Incarceration (ICC = .19): Combined any new self-reported crimes with any new arrest or incarceration (the last two variables described above).The kappa between these two measures was .32. |

An on-site urinalysis protocol (Scott and Dennis 2009; 2011) was used to minimize the rate of under-reported substance use. Women were informed of urinalysis results before being interviewed. During the interviews, inconsistencies between self-reported substance use and urinalysis findings were discussed. As a result of this protocol, false negative rates were low for any alcohol or other drugs (4%), opioids (4%), cocaine (3%), marijuana (2%), and alcohol (1%).

Recidivism was based on any subsequent arrest or incarcerations measured with records data from Cook County’s Incarceration Management and Cost (IMAC) Recovery System and the State of Illinois’ Law Enforcement Agencies Data System (LEADS), as well as self-reported data from the GAIN in order to identify arrests outside of Cook County and Illinois. The types of crimes included drug crime (driving under the influence, sold/make/distribute drugs), property crime (vandalism, forgery, shoplifting), prostitution, violent crime (aggravated assault, armed robbery, involved in someone’s death), and revocation of probation that resulted in a return to jail, arrest or new charges. Across the official records and self-reports, these measures were largely consistent (kappa = .64), with each source identifying some unique cases of rearrest or incarceration. Participants who self-reported the commission of crimes were not necessarily the same as those with formal arrests or incarcerations (kappa = .32); thus, a measure of criminal involvement that incorporated all four sources of information also was created.

Statistical Analysis

Analyses were conducted with IBM SPSS Statistics Version 22. Intake comparisons by random assignment were examined using Chi-Square tests. For the main analyses, the unit of analysis was the participant quarterly observation. To establish temporal order, all predictors (e.g., probation, random assignment to RMC) were based on the prior quarter observations, while all outcomes (e.g., HIV-risk, arrests, substance use) were based on subsequent-quarter observations (e.g., month 3 predicting month 6, month 6 predicting month 9, month 9 predicting month 12). In order to control for multiple observations per participant, analyses were conducted using the generalized linear mixed-model procedure. The repeated measures covariance type selected was a diagonal structure with heterogeneous variance. The outcomes were dichotomous; therefore, the binomial distribution was used with the logit link function.

The first set of analyses had probation status and assignment to RMC within probation status as the fixed set of predictors and people (across time) or the a-intercept as a random factor. In the second set of analyses, intermediate outcomes, such as treatment, self-help, weekly use and HIV risk behaviors, were the fixed predictors of the other outcomes. The second set of analyses was run to test for any indirect effects of probation status and RMC within probation status on the outcomes. The robust method for computing the parameter estimates was employed to account for any possible violations of model assumptions.

Results

Participant Flow

Women were recruited for this experiment from August 22, 2008 to April 16, 2010. During this time, 3,425 women were admitted to Department of Women’s Justice Programs. Figure 1 shows the participant flow during recruitment, randomization, data collection, and intervention. Prior to randomization, 368 (11% of 3,425) women left Department of Women’s Justice Programs before screening was completed; 1,574 (52% of 3,057) women were screened and deemed “not in target population”; 617 (42% of 1,483) women were in the jail’s custody for fewer than 14 days; 56 (6% of 866) women refused to participate in an intake interview; 230 (28% of 810) women were not released to the community; 88 (15% of 580) women were still pending release at the time recruitment ended on April 16, 2010; and 12 (2% of 492) women refused to participate in the experiment.

As shown in Figure 1, the remaining 480 women were randomly assigned at the time of release from Department of Women’s Justice Programs, either to the experimental intervention RMC group (n = 238) or to the control group (n = 242). Of these 480 women, 100% completed the jail intake and release interviews and 95% completed all three of the 30-, 60-, and 90-day post-release interviews. More than 90% completed interviews at each three-month interval from 6 to 36 months. Urine specimens were collected during 97% and 94% of the contacts with women in the control and treatment groups, respectively. HIV testing and counseling were conducted at baseline (83% and 92% completion) and follow-up (98% and 100% completion). Analyses were based on data obtained from women who participated in one or more follow-up sessions, including data from 241 (99% of the 242) of the women randomly assigned to the control group and from 236 (99% of the 238) of the women randomly assigned to the experimental group.

Participants’ Characteristics

Table 2 compares the participant characteristics of the two groups. Urn randomization was successful in achieving a match on all of the targeted variables. In looking at a broader range of characteristics, the groups differed significantly (p < .05) on only 3 of the 51 characteristics (described below), with the women assigned to RMC being more severe in terms of substance use problems and other risky behaviors. The vast majority of women (83%) were African American. Their average age was 37 years old. Most (88%) were single. Nearly two-thirds (63%) had one or more children. A large percentage of the women (60%) had no or only shared custody of their children. Overall, the participants had severe substance use problems. Specifically, more than one-fifth reported that they first used illicit substances before the age of 15. Only 6% indicated that they had no previous episodes of treatment; 62% indicated that they had two or more previous episodes of treatment.

Table 2.

Participant Characteristics by Randomized Condition

| Characteristics | RMCWO

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control (n=242) | RMC (n=238) | Total (n=480) | Chi-sq. | P | |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||||

| African American | 81% | 85% | 83% | 2.84 | 0.416 |

| Caucasian | 8% | 8% | 8% | ||

| Hispanic | 5% | 4% | 5% | ||

| Mixed/Other | 5% | 3% | 4% 36.7 |

||

| Age (mean) | 37.2 | 36.3 | (10.4) | F=0.92 | 0.339 |

| Married/living with someone | 11% | 13% | 12% | 1.06 | 0.589 |

| Divorced/separated/widowed | 18% | 15% | 17% | ||

| Never married | 71% | 72% | 71% | ||

| Number of Children under age 21 | |||||

| None | 41% | 33% | 37% | 3.47 | 0.320 |

| 1 | 16% | 18% | 17% | ||

| 2 | 15% | 18% | 17% | ||

| 3+ | 27% | 31% | 29% | ||

| Child/Custody | (n=141) | (n=158) | (n=299) | ||

| Self Only | 43% | 39% | 41% | 0.54 | 0.768 |

| Self + Others | 28% | 27% | 27% | ||

| Others Only | 30% | 34% | 32% | ||

| Age of first use under 15 | 21% | 22% | 22% | 0.05 | 0.8 17 |

| Prior Substance Abuse Treatment | |||||

| 0 times | 6% | 5% | 6% | 0.51 | 0.776 |

| 1 time | 31% | 34% | 32% | ||

| 2+ times | 63% | 61% | 62% | ||

| Weekly Use in the 90 days before incarceration | 89% | 90% | 89% | 0.01 | 1.000 |

| Dependence (lifetime) | |||||

| Any | 81% | 79% | 80% | 0.10 | 0.820 |

| Alcohol | 15% | 13% | 14% | 0.20 | 0.653 |

| Cannabis | 10% | 10% | 10% | 0.05 | 0.831 |

| Cocaine | 43% | 39% | 41% | 0.76 | 0.384 |

| Opioid | 45% | 45% | 45% | 0.03 | 0.869 |

| Other | 22% | 27% | 24% | 1.37 | 0.242 |

| Any Co-occurring Disorder (Past Year) | 40% | 45% | 43% | 1.38 | 0.268 |

| Depression | 29% | 34% | 32% | 1.46 | 0.228 |

| Anxiety | 10% | 11% | 11% | 0.13 | 0.718 |

| Traumatic Related | 20% | 18% | 19% | 0.53 | 0.467 |

| ADHD | 13% | 17% | 15% | 1.49 | 0.222 |

| Conduct Disorder | 14% | 17% | 15% | 0.70 | 0.403 |

| Pathological Gambling | 2% | 1% | 2% | 0.47 | 0.494 |

|

| |||||

| Borderline Personality | 36% | 40% | 38% | 1.174 | 0.301 |

| Antisocial Personality Behavior | 12% | 9% | 10% | 0.70 | 0.456 |

| HIV Risk Behaviors (past 90 days) | |||||

| Unprotected Sex | 56% | 68% | 74% | 7.67 | 0.006 |

| Multiple Sex Partners | 19% | 24% | 21% | 1.76 | 0.185 |

| Sex Trading | 14% | 13% | 14% | 0.06 | 0.894 |

| Victimization | 67% | 68% | 68% | 0.16 | 0.694 |

| Worried About Victimization | 5% | 9% | 7% | 4.09 | 0.048 |

| Needle Use | 7% | 4% | 5% | 1.95 | 0.163 |

| Needle Sharing | 1% | 0% | 0% | 1.98 | 0.160 |

| Any HIV Risk Behaviors | 86% | 88% | 87% | 0.37 | 0.590 |

| HIV Positive | 4% | 2% | 3% | 1.35 | 0.381 |

| Criminal History | |||||

| First arrest under age 15 | 4% | 4% | 4% | 0.00 | 1.000 |

| 5+ arrests | 52% | 51% | 52% | 0.05 | 0.855 |

| Prior incarceration of a week or more | |||||

| (L5ac) | 88% | 85% | 86% | 0.52 | 0.506 |

| Moderate/High Crime or Violence | 50% | 55% | 53% | 1.12 | 0.289 |

| Types of Current Charges \a | |||||

| Alcohol or Other Drug Crime | 64% | 63% | 63% | 0.11 | 0.777 |

| Property Crime | 28% | 21% | 25% | 2.86 | 0.092 |

| Prostitution | 5% | 5% | 5% | 0.06 | 0.840 |

| Violent Crime | 2% | 5% | 4% | 2.18 | 0.156 |

| Criminal Justice Violations | 3% | 2% | 3% | 0.31 | 0.772 |

| Other | 8% | 8% | 8% | 0.05 | 0.868 |

| At the time of Release\b | |||||

| On Probation or Parole | 31% | 29% | 30% | 0.23 | 0.692 |

| Mandated to Treatment | 23% | 30% | 26% | 3.04 | 0.096 |

Note: Bold indicates p < .05. Only 2 of 62 (3%) of the differences were statistically significant by condition: any unprotected sex & any victimization; but working against randomization and do not show up in differences in sex trading or prostitutions.

Charges from arrest at baseline, extracted from records

Random assignment happened just after the time of release

Nine out of 10 reported that they had used substances in the 90 days before their current detention, and 80% reported that, at some point in their lifetimes, they had been dependent on alcohol or drugs. Nearly one-third reported symptoms of depression and nearly 20% reported trauma-related symptoms. Overall, 43% of the women reported symptoms of one or more disorders comorbid with substance use disorders. Nearly 40% of the subjects reported symptoms of borderline personality disorder in the year preceding their recent detention in Department of Women’s Justice Programs.

Twelve (2.5%) of the women were HIV positive, including 1.5% who became positive during the course of the 3 year study. Moreover, an overwhelming majority of them (87%) reported having engaged in one or more HIV-related risk behaviors (e.g., unprotected sex [74%], multiple sex partners [21%], or needle use [5%]) in the 90 days preceding their recent detention in Department of Women’s Justice Programs. A larger percentage of women in the RMC group than in the control group reported that they had engaged in unprotected sex (68% versus 56%, χ2 = 7.67, p < .006).

More than two-thirds of the women (68%) reported that they had been victimized in the past 90 days before their recent detention in Department of Women’s Justice Programs; a slightly larger percentage of women in the treatment condition than in the control condition reported being worried about being re-victimized (9% versus 5%, χ2 = 4.09, p < .05).

Half of the female detainees indicated at release that they had five or more previous arrests, and 86% reported that they had a previous episode of incarceration lasting a week or longer. Nearly two-thirds of the subjects (63%) had current drug- or alcohol-defined charges, and one-fourth (25%) had been charged with property crimes. Women were in Department of Women’s Justice Programs for an average of 2.4 months. At the time of release, 30% indicated that they were on probation, and a slightly lower percentage (26%) indicated that they were mandated to treatment.

Subject Effects: Probation Supervision

Probation supervision at the beginning of the quarter had wide-ranging but mixed effects on the outcomes measured during the subsequent quarter. Specifically, women in the probation group at the beginning of the quarter were more likely than those in the non-probation group in the next quarter to report any treatment (20% versus 7%, OR = 5.86, p < .001); more than 10 days of treatment (17% versus 6%, OR = 5.98, p < .001); engagement in any type of self-help (32% versus 19%, OR = 2.24, p < .01); and engagement in intensive self-help (23% versus 16%, OR = 1.87, p < .01). Furthermore, women in the probation group were less likely than those in the non-probation group to use alcohol or drugs weekly (35% versus 53%, OR = .40, p < .05) and to engage in unprotected sex (33% versus 39%, OR =.56, p < .05) and any HIV-risk behaviors (58% versus 69%, OR = .44, p < .05). However, with each of the crime-related outcomes, women in the probation group were more likely (i.e., worse) than those in the non-probation group on measures of new crimes (11% versus 9%, OR = 1.49, p < .01); new arrests or incarcerations (25% versus 12%, OR = 2.22, p < .01); and new crimes, arrests, or incarcerations (33% versus 19%, respectively), OR = 2.13, p < .01.

Experimental Intervention Effects: RMC (Nested within Probation Status)

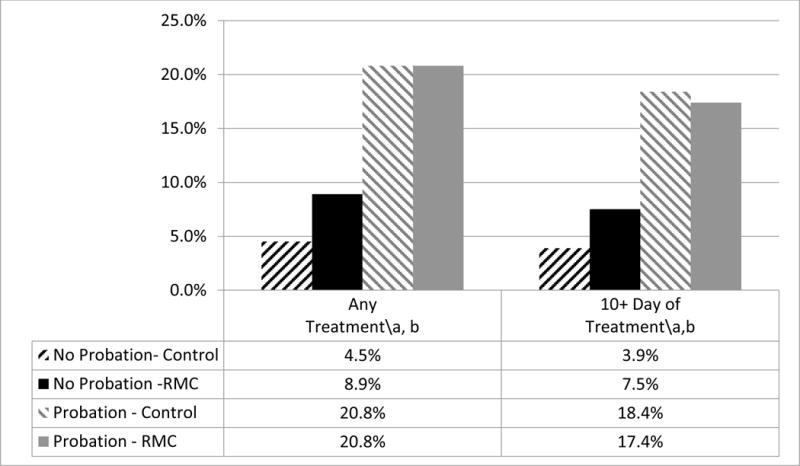

As seen in Table 3, RMCs had a significant subject by intervention interaction effect; specifically, RMCs had favorable effects on women in the community who were not on probation but no effect on those on probation. Among non-probation women at the beginning of the quarter, those who were randomly assigned to RMCs were more likely than those assigned to the control group to engage in any days of substance abuse treatment (8.9% versus 4.5%, OR = 2.12, p < .01) and in more than 10 days of treatment (7.5% versus 3.9%, OR = 2.06, p < .01). They were also less likely to engage in weekly alcohol and drug use (47% versus 60%, OR = .59, p < .05), any unprotected sex (34% versus 46%, OR = .59, p < .01) and any HIV-risk behavior (66% versus 73%, OR = .72, p < .05). Among women on probation, none of these effects was present. As illustrated in Figure 2, probation supervision produced a ceiling effect on treatment and self-help participation (the primary mechanisms by which RMCs can foster client changes).

Table 3.

Direct Effects of Probation and RMC nested within Probation

| No Probation | Probation | Effect of Probation | Effect of RMC nested within Probation

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

RMC (no Pro.)

|

RMC (Pro.)

|

|||||||

| Next Wave Outcomes | Prevalence (o=4,500) | Control (o=1,320) | RMC (o=1,196) | Control (o=983) | RMC (o=1,001) | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI |

| Any Days of treatment | 12.9% | 4.5% | 8.9% | 20.8% | 20.8% | 5.86 | (4.00, 8.57) | 2.12 | (1.40, 3.20) | 0.98 | (0.070, 1.38) |

| More than 10 days of treatment | 11.0% | 3.9% | 7.5% | 18.4% | 17.4% | 5.98 | (3.95, 9.06) | 2.06 | (1.29, 3.27) | 0.94 | (0.67, 1.33) |

| Any Self-help involvement | 25.0% | 16.4% | 22.2% | 30.9% | 34.0% | 2.24 | (1.56, 3.20) | 1.45 | (0.95, 2.24) | 1.15 | (0.83, 1.61) |

| High Self-help involvement | 18.4% | 12.5% | 16.9% | 21.4% | 24.9% | 1.87 | (1.26, 2.76) | 1.42 | (0.86, 2.32) | 1.22 | (0.84, 1.78) |

| Weekly Alcohol or Other Drug use | 45.8% | 60.4% | 47.2% | 37.8% | 32.8% | 0.40 | (0.30, 0.54) | 0.59 | (0.41, 0.84) | 0.80 | (0.57, 1.12) |

| Had unprotected sex | 36.8% | 46.0% | 33.5% | 32.2% | 33.3% | 0.56 | (0.42, 0.74) | 0.59 | (0.44, 0.79) | 1.05 | (0.75, 1.47) |

| Any HIV Risk Behaviors | 64.7% | 73.1% | 66.3% | 54.8% | 61.4% | 0.44 | (0.34, 0.58) | 0.72 | (0.53, 0.98) | 1.31 | (0.96, 1.78) |

| Any new crimes | 10.0% | 8.9% | 9.3% | 12.7% | 9.8% | 1.49 | (1.04, 2.15) | 1.09 | (0.73, 1.55) | 0.77 | (0.53, 1.11) |

| Any new arrest or incarceration* | 18.0% | 12.5% | 12.0% | 24.4% | 26.3% | 2.22 | (1.70, 2.90) | 0.94 | (0.67, 1.31) | 1.10 | (0.86, 1.40) |

| Any new crimes, arrests or incarceration* | 25.8% | 19.7% | 19.3% | 34.3% | 33.1% | 2.13 | (1.66, 2.74) | 0.97 | (0.72, 1.31) | 0.95 | (0.73, 1.24) |

Note: Bold Black indicates positive effect with p < .05; Bold Italic indicated negative effect with p < .05

Based on self-report, county or state records

Figure 2. Subject (Probation) by Treatment (RMC) Interaction.

\a Significant effect of Probation vs no probation at p<.05

\b Significant effect of RMC vs Control within the no-probation strata.

Indirect Effects: Probation, Self-Help, and RMCs

The effects of services in the previous quarter on proximal outcomes in the subsequent quarter were examined in order to understand how treatment and self-help were indirectly related to longer-term outcomes. In the analyses of indirect effects, treatment (in the previous quarter) was positively related in the subsequent quarter to weekly alcohol and drug use (OR = 1.66, p < .01) as well as to the likelihood of new crimes (OR = 1.76, p < .01); new arrests or incarcerations (OR = 2.19, p < .01); and new crimes, arrests, or incarcerations (OR = 2.58, p < .01). In contrast, 10 or more days of treatment (OR = .40, p < .05), and participation in self-help (OR = .67, p < .05) and intensive self-help activities (OR = .28, p < .05) predicted a lower likelihood of weekly alcohol and drug use (Table 4).

Table 4.

Indirect Effects Probation and RMC

| Outcomes from End of the Quarter | Prevalence | Predictors from the Beginning of the Quarter

|

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any Treatment | More than 10 days of Treatment | Any Self-Help | High Self-Help Involvement | Weekly Alcohol or Other Drug use | Any unprotected Sex | Any HIV risk Behaviors | |||||||||

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | ||

| Weekly Alcohol or Other Drug use | 45.8% | 1.66 | (1.06, 2.59) | 0.40 | (0.25, 0.64) | 0.67 | (0.50, 0.90) | 0.28 | (0.20, 0.40) | ||||||

| Had unprotected sex | 36.8% | 0.98 | (0.63, 1.53) | 0.82 | (0.51, 1.34) | 1.09 | (0.81, 1.39) | 1.23 | (0.89, 1.72) | 1.69 | (1.39, 2.07) | ||||

| Any HIV Risk Behaviors | 64.7% | 0.78 | (0.50, 1.22) | 0.93 | (0.58, 1.51) | 1.14 | (0.84, 1.54) | 0.99 | (0.70, 1.41) | 2.38 | (1.94, 2.93) | ||||

| Any new crimes | 10.0% | 1.76 | (1.01, 3.06) | 0.66 | (0.35, 1.25) | 1.07 | (0.70, 1.63) | 0.74 | (0.45, 1.22) | 2.54 | (1.96, 3.30) | 1.10 | (0.82, 1.47) | 1.58 | (1.14, 2.18) |

| Any new arrest or incarceration* | 18.0% | 2.19 | (1.35, 3.56) | 1.64 | (0.97, 2.76) | 0.82 | (0.60, 1.13) | 0.56 | (0.39, 0.80) | 0.93 | (0.75, 1.14) | 0.98 | (0.77, 1.23) | 0.66 | (0.53, 0.81) |

| Any new crimes, arrests or incarceration* | 25.8% | 2.58 | (1.66, 4.03) | 1.15 | (0.71, 1.86) | 0.82 | (0.62, 1.09) | 0.64 | (0.46, 0.89) | 1.28 | (1.06, 1.55) | 1.10 | (0.90, 1.36) | 0.77 | (0.63, 0.95) |

Note: Bold Black indicates positive effect with p < .05; Bold Italic indicated negative effect with p < .05

Based on self-report, county or state records

Participation in intensive self-help activities in the previous quarter also was related to fewer new arrests and incarcerations (OR = .56, p < .05), crimes, arrests, or incarcerations (OR = .64, p < .05) in the next quarter (Table 4). In addition, weekly alcohol and drug use was related to unprotected sex (OR = 1.69, p < .05); HIV-risk behaviors (OR = 2.38, p < .05); new crimes (OR = 2.54, p < .05); and new crimes, arrests, or incarcerations (OR = 1.28, p < .05). Finally, HIV-risk behaviors were positively related to any new crimes (OR = 1.58, p < .05), but they were negatively related to new arrests or incarcerations (OR = .66, p < .05) and new crimes, arrests, or incarcerations (OR = .63, p < .05) (Table 4).

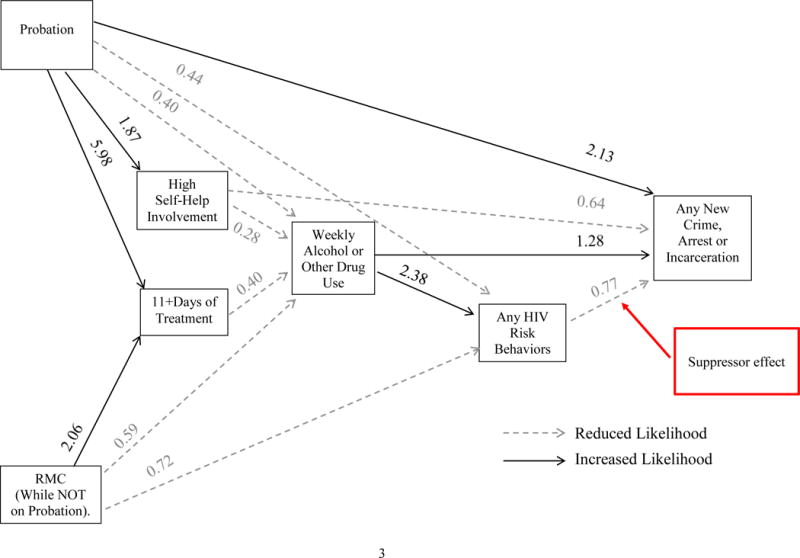

Figure 3 provides a summary of the odds ratios for the primary direct and indirect effects of probation and RMC (while not on probation) on treatment and self-help involvement, showing how each then affects weekly alcohol and other drug use, then HIV-risk behaviors, and finally recidivism. The solid bars signify that the predictor was associated with an increased likelihood in the subsequent variable, whereas the dashed bars signify that the predictor was associated with a decreased likelihood in the subsequent variable. The odds ratios are taken directly from Tables 3 and 4, not the results of a path analysis. Probation and RMC were associated with both increases in treatment participation (the primary outcome) and self-help involvement, as well as decreases in weekly alcohol or other drug use and HIV-risk behavior. High levels of treatment and self-help participation were related to reductions in weekly alcohol or other drug use but not HIV-risk behavior. The effect of self-help involvement on weekly use was less than treatment’s effects but exerted an additional direct effect on recidivism. Weekly alcohol or other drug use was related to higher rates of HIV-risk behaviors and recidivism; however, HIV-risk behaviors, were related to a reduction in the odds of recidivism (a suppressor effect).

Figure 3.

Summary of Direct and Indirect Effects (odds ratios) on Any Crime, Arrest, or Incarceration

Discussion

Reprise of Major Findings

Overview

Among female detainees released from Department of Women’s Justice Programs to community-based substance abuse treatment programs, the current study found mixed effects for specialized probation, a probation (subject) by RMCs (intervention) interaction, and indirect effects for probation and RMCs (via treatment and self-help) on substance abuse, HIV, and criminal justice-related outcomes. Each of these effects are discussed below.

Mixed Effects of Probation

Women in the probation group were more likely than those in the non-probation group to be engaged in any days of treatment, more than 10 days of treatment, any self-help activities, and more intensive self-help activities. They also were more likely than women in the non-probation group to refrain from weekly alcohol or other drug use, HIV-risk behaviors, and unprotected sexual activities. The favorable effects of probation on participant outcomes can be explained largely by the particular nature of the probation programming that most participants experienced during the study. Many of the women were in a specialized probation program (POWER), which strongly encouraged participation in therapeutic groups and other recovery-focused activities both while in Department of Women’s Justice Programs and after release (Lurigio et al. 2007). The POWER program also epitomized the type of gender-responsive supervision that fosters “positive change” in the lives of female probationers, in contrast to standard probation supervision, which more often leaves women with limited oversight, little access to resources and weak or nonexistent relations with supervising officers and staff. (Morash et al 2015).

The positive effects of probation extended only to behavioral health outcomes. Within the cohort, those sentenced to probation were more likely than those in the community with no supervision to be convicted of more serious crimes and to have more previous arrests (Lurigio et al. 2004)—factors that are correlated with recidivism while on supervision (Olson and Lurigio 2000). With all other things being equal, police are more likely to re-arrest people on probation than to arrest free citizens. In addition, arrest while on probation is in itself a violation of probation that increases the likelihood of reincarceration (Seng and Lurigio 2005). Taken together, these factors might explain why women on probation at the beginning of the quarter (vs. those who were not) had poorer criminal justice outcomes at the end of the quarter.

Probation by RMC Interaction Effects

Most women were on probation at some point in the 3 years of the study, but not on average in any given quarter. This study found probation (subject) by RMCs (intervention) interaction effects on outcomes. Within the observations in which women were not on probation at the beginning of the quarter, the results showed that randomization to RMC (vs. control) exerted a strong and positive impact on any days of treatment, more than 10 days of treatment, weekly alcohol or other drug use, unprotected sex, and HIV-risk behaviors. These findings are consistent with those reported in earlier studies of RMCs (Dennis et al. 2003a; Dennis and Scott 2012; Scott et al. 2005; 2011; Scott and Dennis 2009; 2012).

In contrast, within the observations in which women started the quarter on probation, randomization to RMC had no effect. This unexpected outcome appears to be due to a ceiling effect of probation on treatment participation (the primary mechanism by with both probation and RMC work). As shown in Figure 2, during observations when women were already on probation and assigned to the control group, they actually performed better on treatment and self-help participation outcomes than women who were not on probation but assigned to RMC (see Figure 2). Thus, this study suggests that women sentenced to the type of specialized probation programming described above, are unlikely to benefit from RMC.

Indirect Effects

The summary of the significant findings from Tables 3 and 4 provided in Figure 3 helps illustrate the complex nature of treatment, self-help, alcohol or other drug use, and HIV-risk behaviors in predicting recidivism. Both probation and RMC (while not on probation) both affect some of the same key services and behavioral outcomes. Findings show that treatment has a large direct effect on alcohol or other drug use. The current results also strongly support the direct and indirect effects of high levels of engagement in self-help on reducing substance use and criminal behaviors (Humphreys 2004). Although HIV-risk behaviors are often omitted from criminological research, such behaviors appear to be important in understanding the impact of RMC and weekly alcohol or other drug use on recidivism. Participation in POWER and RMC could have lowered the risk of harmful behavior by preparing women to identify with an evolving prosocial network of others, moving participants toward similar situations and mind-sets on the recovery trajectory. Growing support in the criminological literature suggests that differential social support from networks of confiding partners can lead to reductions in various antisocial behaviors (Colvin et al. 2002).

The unexpected negative relationship between HIV-risk practices and any new arrest or reincarceration (suppressor effect) might also be attributable to developments in the local criminal justice system as well as changes in the nature of the sex trade in Chicago and Cook County. Specifically, the Cook County Criminal Courts have launched several specialized courts to focus on defendants with behavioral healthcare problems. These include drug treatment courts, mental health courts, and veterans’ courts. Among the most recently implemented specialized courts is prostitution and trafficking intervention court, which provides women in the sex trade with diversionary services. Less formalized versions of this court were already being implemented locally during the late 2000s. A forerunner to the establishment of prostitution court was the decision to downgrade prostitution from a felony to a misdemeanor and to afford police officers with more discretion in forgoing the arrests of women for solicitation.

A trend toward the decriminalization of prostitution began more than a decade ago in Cook County and coincides with a local and nationwide shift in the sex trade from a primarily outdoor (street-based) to a primarily indoor market (massage parlors, escort services, and online venues) (Cunningham and Kendall 2011). Thus, behaviors associated with elevated HIV-risk such as trading sex for money or drugs (i.e., prostitution) might have unexpectedly led to fewer arrests and incarcerations due to policy changes seeking less formal (e.g., deferred prosecutions) and more service-oriented responses to prostitution cases. Coincidentally, changes in the local sex market (i.e., less outdoor sex purveying), might have made sex workers less susceptible to arrests.

Strengths and Limitations

The current study had several strengths. Substantively, it addressed a growing but often-understudied population (women released to the community from jail) over a 3-year period in which their situations repeatedly changed. Methodologically, it included a large sample size, high participation and follow-up rates, strict implementation of clinical and experimental protocols (i.e., high fidelities), varied sources of data, standardized measures, long-term follow-up periods, and many repeated measures and temporal-order analyses.

The study also was limited. Specifically, it involved a single-site trial in a large urban jail with a predominately minority female population and therefore should be replicated in more diverse sites and populations. The current study focused on quarterly changes because women shifted in and out of probation supervision; however, the study did not explore their more complex trajectories throughout the study’s three-year period. For logistical reasons, the study excluded women who were released from jail or furlough in 14 or fewer days, limiting its generalizability to all releasees.

Finally, while we know anecdotally that most women on probation during the study were participating in POWER, we were unable to measure directly neither when women were actually in POWER or other types of probation programs nor the actual intensity of those programs. Thus, a limitation of the current investigation is the absence of data on participants’ exact probation status and experiences throughout the years in question. Specifically, the direct mechanism to transfer women at sentencing from Department of Women’s Justice Programs to POWER was in place during the duration of the study (2008–2013) (personal communication, M. Bacula, 2015). Unknown is the exact percentage of the probation clients who were supervised in POWER or on a standard probation caseload. Nonetheless, many of our comments regarding the lack of an effect for RMCs on probationers would likely apply to both programs albeit in differing degrees. For example, women in either type of program would have enjoyed a supportive relationship with probation officers who solicited services for their female clients, particularly programming in the behavioral healthcare arena (Seng and Lurigio 2005). Therefore, women on standard probation, akin to those in POWER but to a less intensive and perhaps gender-sensitive degree, would also have received one-on-one counseling, affirmation and encouragement during drug treatment, as well as assistance with housing and psychiatric rehabilitation. These interventions could have also swamped the impact of RMCs on the study’s outcomes.

Conclusions

Substance abuse can lock female offenders into patterns of addiction, HIV-risk behaviors, and criminal activity that are severe and dynamic (Inciardi et al. 1997; Lurigio et al. 2007). Far too often, female offenders are prevented from accessing treatment or self-help opportunities. Specialized probation (e.g., POWER) and RMCs (absent probation) significantly increased access to both types of interventions, which reduced subsequent alcohol or other drug use, HIV-risk behaviors, illegal activity, rearrest, and incarceration.

Initial access to and retention in community-based treatment post-release would be adequate if the nature of addiction was acute. Evidence suggests that most substance abusers who enter publicly funded treatment suffer from more chronic conditions that cause them to cycle through periods of relapse, treatment reentry, reincarceration, and recovery (Scott and Dennis 2009; 2011). These cyclical periods often persist for several years, particularly when accompanied by co-occurring conditions. Female releasees from jail with substance use disorders are no exception; they regularly require help accessing services even after they have reentered the community for three years. In a similar way, women’s probation status and illegal activity move in cycles of three years. Both probation and RMC (absent probation) help increase treatment participation and self-help involvement as well as reduce alcohol or other drug use, HIV-risk behaviors, and resultant recidivism. The next challenge is to learn more about the cost-effectiveness and duration of the therapeutic effects of the approaches explored in the current study.

Acknowledgments

This article was supported by National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) Grants DA021174. The authors thank Rod Funk for assistance in preparing the manuscript; the women who participated in the interviews; and the Cook County Jail’s Division 17 staff and administration. The opinions are those of the authors and do not reflect official positions of the government.

Biographies

Christy K. Scott, Ph.D., is the director of the Lighthouse Institute and the Illinois Survey Laboratory, Chestnut Health Systems, Chicago, IL. Her research focuses on understanding and predicting how people move through the cycles of substance use, crime, treatment, incarceration, and periods of recovery, as well as how to experimentally test strategies for improving recovery management over time. Publishing widely on recovery management, how to achieve greater than 90% follow-up rates in longitudinal studies, and intensive data collection with smart phones, she has developed and tested different interventions for managing addiction over time.

Michael L. Dennis, Ph.D., is a senior research psychologist at the Lighthouse Institute and director of the GAIN Coordinating Center at Chestnut Health Systems, Normal, IL. His research focus is understanding and predicting how people move through the cycles of substance abuse, crime, treatment, incarceration, and periods of recovery, as well as how to experimentally test strategies for improving recovery management over time. He has published widely on recovery management, integrating clinical and research assessment, measurement, intensive data collection with smart phones, and evaluation research.

Arthur J. Lurigio, PhD, a psychologist, is senior associate dean for faculty in the College of Arts and Sciences and a professor of criminal justice and criminology and psychology, Loyola University Chicago. Named a 2003 Faculty Scholar, the highest honor bestowed on senior faculty at Loyola, he was named a Master Researcher in 2013 by the College of Arts and Sciences in recognition of his continued scholarly productivity.

Contributor Information

Christy K Scott, Chestnut Health Systems, Chicago & Normal, IL.

Michael L. Dennis, Chestnut Health Systems, Chicago & Normal, IL

Arthur J. Lurigio, College of Arts and Sciences, Loyola University Chicago, Chicago, IL

References

- Adams S, Leukefeld CG, Peden AR. Substance abuse treatment for women offenders: A research review. Journal of Addictions Nursing. 2008;19:61–75. [Google Scholar]

- Adams SM, Peden AR, Hall LA, Rayens MK, Staten RR, Leukefeld CG. Predictors of retention of women offenders in a community-based residential substance abuse treatment program. Journal of Addictions Nursing. 2011;22:103–116. [Google Scholar]

- Alemagno SA. Women in jail: Is substance abuse treatment enough? American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91:798–800. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.5.798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belenko S, Langley S, Crimmins S, Chaple M. HIV risk behaviors, knowledge, and prevention education among offenders under community supervision: A hidden risk group. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2004;16:367–385. doi: 10.1521/aeap.16.4.367.40394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blitz CL, Wolff N, Pan KY, Pogorzelski W. Gender-specific behavioral health and community release patterns among New Jersey prison inmates: Implications for treatment and community reentry. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95:1741–1746. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.059733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloom B, Owen B, Covington S. Women offenders and the gendered effects of public policy. Review of Policy Research. 2004;21:31–48. [Google Scholar]

- Bureau of Justice Statistics. Prison statistics: Summary findings. U.S. Department of Justice; Washington D.C.: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV/AIDS surveillance report. 15. Vol. 2003. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Charpentier PA. Urn randomization program gRand v1.10. New Haven: Connecticut: Yale University; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Colvin M, Cullen FT, Vander Ven T. Coercion, social support, and crime: An emerging theoretical consensus. Criminology. 2002;40:19–42. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham S, Kendall TD. Prostitution 2.0: The changing face of sex work. Journal of Urban Economics. 2011;69:273–287. [Google Scholar]

- De Groot A. HIV infection among incarcerated women: epidemic behind bars. AIDS Reader. 2000;10:287–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeHart DD. Pathways to prison: Impact of victimization in the lives of incarcerated women. Violence Against Women. 2008;14:1362–1381. doi: 10.1177/1077801208327018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis ML, Lennox RI, Foss M. Practical power analysis for substance abuse health services research. In: Bryant KJ, Windle M, West SG, editors. The science of prevention: Methodological advances from alcohol and substance abuse research. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1997. pp. 367–405. [Google Scholar]

- Dennis ML, Scott CK. Four-year outcomes from the Early Re-Intervention Experiment (ERI) with Recovery Management Checkups (RMC) Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2012;121:10–17. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.07.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis M, Scott CK, Funk R. An experimental evaluation of recovery management checkups (RMC) for people with chronic substance use disorders. Evaluation and Program Planning. 2003a;26(3):339–352. doi: 10.1016/S0149-7189(03)00037-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis ML, Titus JC, White M, Unsicker J, Hodgkins D. Global Appraisal of Individual Needs (GAIN): Administration guide for the GAIN and related measures. Bloomington, IL: Illinois Chestnut Health Systems; 2003b. Version 5 ed. Retrieved from http://www.gaincc.org/gaini. [Google Scholar]

- Elias GL, Ricci K. Women in jail: Facility planning issues. Washington, DC: National Institute of Corrections, US Department of Justice; 1997. Retrieve from https://www.ncjrs.gov/app/abstractdb/AbstractDBDetails.aspx?id=166146. [Google Scholar]

- Escobar G, Olson DE. A profile of women released into Cook County communities from jail and prison. Criminal Justice and Criminology: Faculty publications and other works, Paper. 2012;8 Retrieved July 23, 2014, from http://ecommons.luc.edu/crimnaljsuitce_facpubs/8. [Google Scholar]

- Fogel C, Belyea M. The lives of incarcerated women: Violence, substances abuse, and at risk for HIV. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. 1999;10:66–74. doi: 10.1016/S1055-3290(06)60322-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freudenberg N, Moseley J, Labriola M, Daniels J, Murrill C. Comparison of health and social characteristics of people leaving New York City jails by age, gender, and race/ethnicity: Implications for public health interventions. Public Health Reports. 2007;122:733–743. doi: 10.1177/003335490712200605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaze LE. Correctional population in the United States. Vol. 2009. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Program, Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Grella CE, Annon JJ, Anglin MD. Drug use and risk for HIV among women arrestees in California. AIDS and Behavior. 2000;4:289–295. [Google Scholar]

- Grella CE, Greenwell L. Treatment needs and completion of community-based aftercare among substance-abusing women offenders. Women’s Health Issues. 2007;17:244–255. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2006.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guydish J, Chan M, Bostrom A, Jessup MA, Davis TB, Marsh C. A randomized trial of probation case management for drug-involved women offenders. Crime and Delinquency. 2011;57:167–198. doi: 10.1177/0011128708318944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herberman Erinn JD, Bonczar TP. Probation and parole in the United States. Vol. 2013. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2015. Retrieved from http://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/ppus13.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- HIV Education Prison Project. HIV infection among incarcerated women. HEEP News. 2001;4:3–5. [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys K. Circles of recovery: Self-help organizations for addictions. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, UK: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Inciardi JA, Martin SS, Butzin CF, Hooper RM, Harrison LD. An effective model of prison-based treatment for drug-involved offenders. Journal of Drug Issues. 1997;27:261–278. [Google Scholar]

- Iroh PA, Mayo H, Nijhawan AE. The HIV care cascade before, during, and after incarceration: a systematic review and data synthesis. American Journal of Public Health. 2015;105(7):e5–e16. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan MR, Wohl DA, Weir SS, Adimora AA, Moseley C, Norcott K, Miller WC. Incarceration and risky sexual partnerships in a southern U.S. city. Journal of Urban Health. 2008;85:100–113. doi: 10.1007/s11524-007-9237-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King E, Foley JE. Gender-responsive policy development in corrections: What we know and roadmaps for change. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice National Institute of Corrections; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lurigio AJ, Roque L, Stalans L, Seng M. Evaluation of the Cook County Promotion of Women Education and Resources (POWER) Probation Program. Paper presented at the Center for the Advancement of Research, Training, and Education; Loyola University, Chicago, IL. 2004. Apr, [Google Scholar]

- Lurigio AJ, Stalans L, Roque L, Seng M, Ritchie J. The effects of specialized supervision on women probationers: An evaluation of the POWER program. In: Muraskin R, editor. It’s a crime: Women and justice. 4th. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 2007. pp. 127–145. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch S, Fritch A, Heath N. Looking beneath the surface: The nature of incarcerated women’s experiences of interpersonal violence, treatment needs, and mental health. Feminist Criminology. 2012;7:381–400. [Google Scholar]

- Maruschak LM. HIV in prisons. Vol. 2001. Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2004. Retrieved on 1/12/2010 from http://bjs.ojp.usdoj.gov/ [Google Scholar]

- Maruschak LM. HIV prisons. 2001–2010. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Maruszhak LM, Bonczar TP. Probation and parole in the United States. Vol. 2012. Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics, Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- McClelland GM, Teplin LA, Abram KM, Jacobs N. HIV and AIDS risk behaviors among female jail detainees: Implications for public health policy. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92:818–825. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.5.818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesney-Lind M. “Women and Crime”: The Female Offender. Signs. 1986;12(1):78–96. [Google Scholar]

- Minton TD, Golinelli D. Jail inmates at mid-year 2013: Statistical tables. Washington, D.C.: Bureau of Justice Statistics, Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- McCollister K, French MT, Freitas DM, Dennis ML, Scott CK, Funk RR. Cost-Effectiveness analysis of Recovery Management Checkups (RMC) for adults with chronic substance use disorders: evidence from a four-year randomized trial. Addiction. 2013;108:2166–2174. doi: 10.1111/add.12335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morash M, Kashy DA, Smith SW, Cobbina JE. The effects of probation or parole agent relationship style and women offenders’ criminogenic needs on offenders’ responses to supervision interactions. Criminal Justice and Behavior. 2015;42:412–434. [Google Scholar]

- Moyers TB, Martin T, Manuel JK, Miller WR, Ernst D. Revised Global Scales: Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity 3.1.1. University of New Mexico Center on Alcoholism, Substance Abuse and Addictions (CASAA); Albuquerque, NM: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ney B, Ramirez R, Van Dieten M. Ten truths that matter when working with justice involved women. Silver Spring, MD: National Resource Center on Justice Involved Women; 2012. Retrieved July 9, 2015 from http://cjinvolvedwomen.org/sites/all/documents/Ten_Truths.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Olson DE. Cook County Sheriff’s Reentry Council Research Bulletin. Chicago: Cook County Sheriff’s Office; 2013. An examination of admissions, discharges, and the population of the Cook County Jail, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Olson DE, Lurigio AJ. Predicting probation outcomes: Factors associated with probation rearrests, revocations, and technical violations during supervision. Justice Research and Policy. 2000;1:73–86. [Google Scholar]

- Oser C, Knudsen H, Staton-Tindall M, Leukefeld C. The adoption of wraparound services among substance abuse treatment organizations serving criminal offenders: The role of a women-specific program. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2009;103:S82–S90. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott CK. A replicable model for achieving over 90% follow-up rates in longitudinal studies of substance abusers. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2004;74:21–36. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2003.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott CK, Dennis ML. Recovery Management Check-ups (RMC) Procedure Manual. Chestnut Health Systems; Illinois: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Scott CK, Dennis ML. Results from two randomized clinical trials evaluating the impact of quarterly recovery management checkups with adult chronic substance users. Addiction. 2009;104:959–971. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02525.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott CK, Dennis ML. Recovery management checkups with adult chronic substance users. In: Kelly JF, White WL, editors. Addiction recovery management: Theory, science, and practice. New York: Springer Science; 2011. pp. 87–102. [Google Scholar]

- Scott CK, Dennis ML. The first 90 days following release from jail: Findings from the Recovery Management Checkups for Women Offenders (RMCWO) experiment. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2012;125:110–118. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.03.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott CK, Dennis ML, Foss MA. Utilizing recovery management checkups to shorten the cycle of relapse, treatment reentry, and recovery. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2005;78:325–338. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott CK, Dennis ML, Laudet A, Funk RR, Simeone RS. Surviving drug addiction: The effect of treatment and abstinence on mortality. American Journal of Public Health. 2011;101:737–744. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.197038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott CK, Dennis ML, Lurigio AJ. HIV risk among female detainees: A description of practices, perceptions, and knowledge. Journal of Forensic Social Work in press. [Google Scholar]

- Scott CK, Grella CE, Dennis ML, Funk RR. Predictors of recidivism over 3 years among substance-using women released from jail. Criminal Justice and Behavior. 2014;41:1257–1289. doi: 10.1177/0093854814546894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seng M, Lurigio AJ. Probation officers’ views on supervising women probationers. Women and Criminal Justice. 2005;16:65–86. [Google Scholar]

- Singer MI, Bussey J, Song LY, Lunghofer L. The psychosocial issues of women serving time in jail. Social Work. 1995;40:103–113. doi: 10.1093/sw/40.1.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staton-Tindall M, Duvall J, McNees E, Walker R, Leukefeld C. Outcomes following prison and jail-based treatment among women residing in metro and non-metro communities following release. Journal of Drug Issues. 2011;41:197–215. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens J, Zierler S, Cram V, Dean D, DeGroot A, Mayer K. Risk for HIV infection in incarcerated women. Journal of Women’s Health. 1995;4:569–577. [Google Scholar]

- Stout KJ, Sullivan PJ, Dong WP, Mainsah E, Lou N, Mathia T, Zahouani H. The development of methods for the characterization of roughness on three dimensions. Publication no EUR 15178 EN of the Commission of the European Communities; Luxembourg: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Taxman FS, Perdoni ML, Harrison LD. Drug treatment services for adult offenders: The state of the art. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2007;32:329–254. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teplin LA, Mericle AA, McClelland GM, Abram KM. HIV and AIDS risk behaviors in juvenile detainees: Implications for public health policy. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93:906–912. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.6.906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Titus JC, Smith D, Dennis ML, Ives M, Twanow L, White MK. Impact of a training and certification program on the quality of interviewer-collected self-report assessment data. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2012;42:201–212. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2011.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsberg WM, Lam WKK, Zule WA, Bobashev G. Efficacy of a woman-focused intervention to reduce HIV risk and increase self-sufficiency among African American crack abusers. American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94:1165–1173. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.7.1165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wexler HK, Prendergast ML, Melnick G. Introduction to a special issue: Correctional drug treatment outcomes—Focus on California. The Prison Journal. 2004;84:3–7. [Google Scholar]

- Young AM, Boyd C, Hubbell A. Prostitution, drug use, and coping with psychological distress. Journal of Drug Issues. 2008;30:789–800. [Google Scholar]

- Zierler S, Krieger N. Reframing women’s risk: Social inequalities and HIV infection. Annual Review of Public Health. 1997;18:401–36. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.18.1.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]