This minireview showcases the role indole diterpenoids have played in inspiring the development of clever synthetic strategies and new chemical reactions.

This minireview showcases the role indole diterpenoids have played in inspiring the development of clever synthetic strategies and new chemical reactions.

Abstract

Indole terpenoids comprise a large class of natural products with diverse structural topologies and a broad range of biological activities. Accordingly, indole terpenoids have and continue to serve as attractive targets for chemical synthesis. Many synthetic efforts over the past few years have focused on a subclass of this family, the indole diterpenoids. This minireview showcases the role indole diterpenoids have played in inspiring the recent development of clever synthetic strategies, and new chemical reactions.

Introduction

Indole terpenoids are a natural product family of paramount importance to biology and chemistry. Several family members have had a tremendous impact on human medicine, such as the dimeric monoterpene indole alkaloids, vincristine and vinblastine, both of which are used to treat numerous types of cancer.1 Furthermore, indole terpenoids have served as structural platforms for the development of new chemical methods and strategies for many years.2 From the classic synthesis of lysergic acid3 by Woodward in 1956, to Boger's development of ingenious cascade reactions toward the Vinca alkaloids4 it is evident that indole terpenoids have played a vital role in spawning innovation in chemical synthesis.

The indole diterpenoids, a subclass of the indole terpenoid family, have recently garnered increased attention from synthetic chemists. The resulting total syntheses, several of which are the focus of this minireview, highlight the impact that indole diterpenoids have had on the development of enabling strategies and methods in chemical synthesis. This minireview, however, is not intended to be comprehensive. There are several elegant syntheses of indole diterpenoids that are not covered herein,5 including those by Li, who has accomplished impressive syntheses of a number of indole terpenoids, including xiamycin A and tubingensin A.6

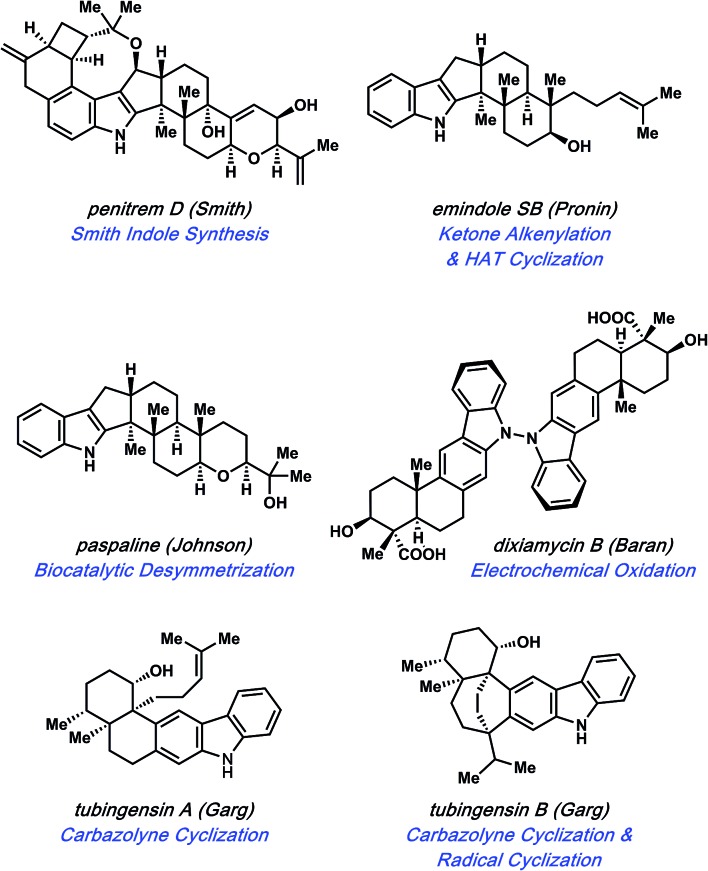

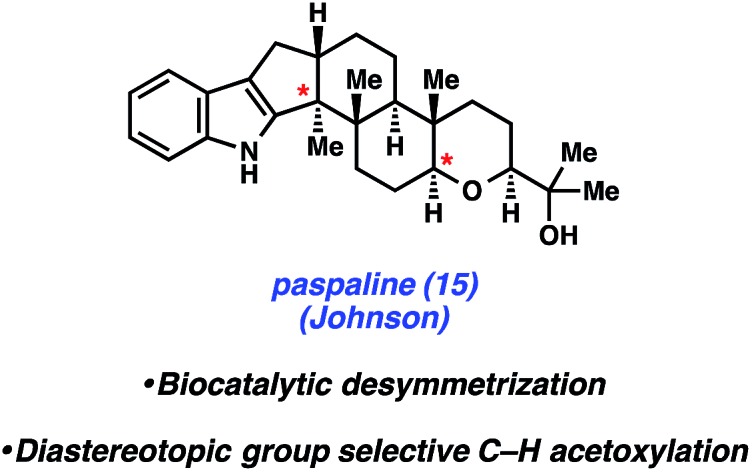

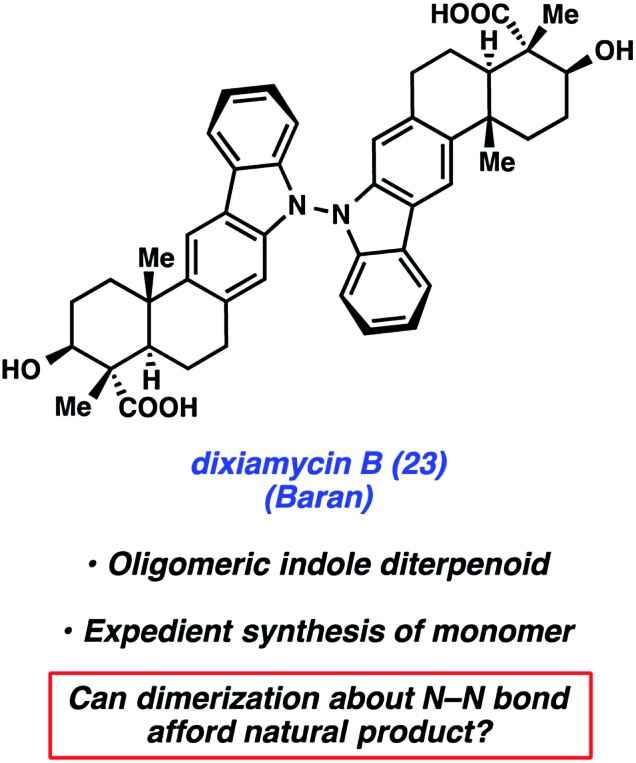

Specific natural products discussed in this review are shown in Fig. 1. The first topic presented pertains to arguably the most complex member of this natural product family, penitrem D. The synthesis of penitrem D by the Smith group features the use of an innovative fragment coupling/indole synthesis methodology.7 Next, recent efforts toward the related compounds, emindole SB8 and paspaline,9 by Johnson and Pronin, respectively, are discussed. We then highlight the Baran synthesis of dixiamycin B,10 which has led to the considerable advancement of electrochemical methods in organic synthesis. Finally, we conclude by examining the strategic use of heterocyclic arynes to enable concise total syntheses of tubingensins A and B, as reported by our laboratory.11

Fig. 1. Indole diterpenoids as platforms for discovery.

Smith's total synthesis of penitrem D

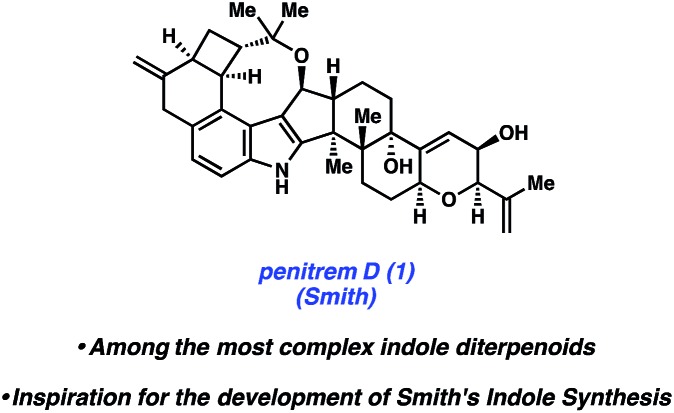

Of the groups who have targeted indole diterpenoid natural products, the Smith group has been amongst the most successful. Their work led to the total syntheses of a myriad of indole diterpenoids,12 including, but not limited to, paspaline,12a paspalicine,12b and paspalinine.12b These efforts set the stage for the pursuit of (–)-penitrem D (1, Fig. 2), a tremorgenic alkaloid isolated from Penicillium crustosum in 1983.13 Indole tremorgens are believed to cause neurological disorders in livestock by inhibition of potassium channels.14

Fig. 2. The indole diterpenoid penitrem D (1).

Penitrem D (1) is one of the most complex natural products in the indole diterpenoid family. Consequently, the Smith group reported the only total synthesis.7 The structure contains a staggering nine rings, a highly functionalized indole core, and eleven stereocenters. Of the stereocenters in 1, five are contiguous and two are vicinal quaternary centers. The total synthesis of penitrem D (1) therefore represents an extraordinary feat in and of itself.

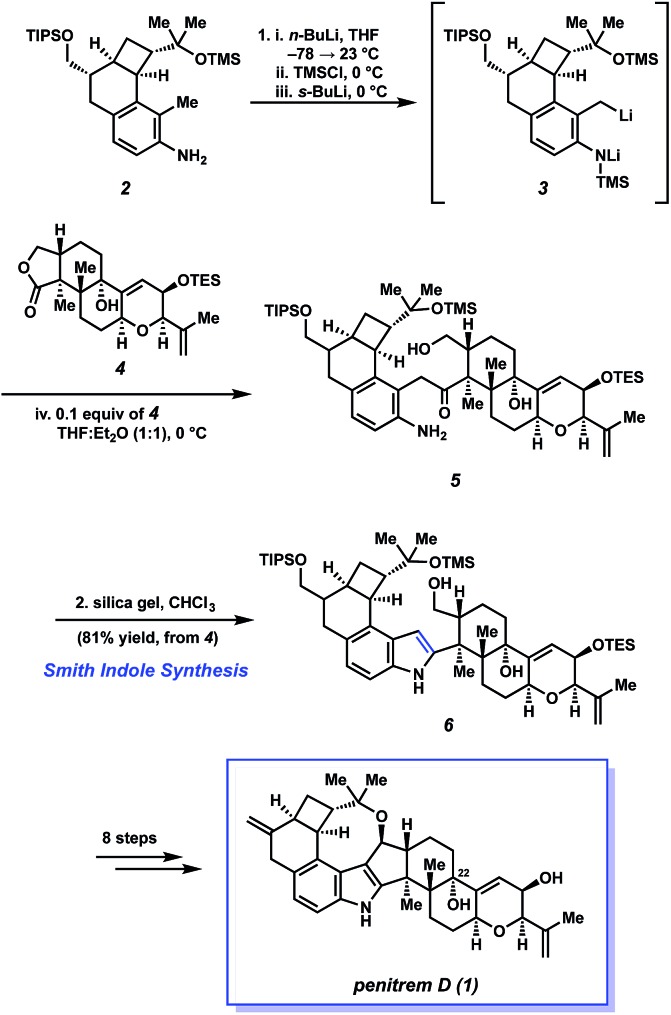

The synthesis of penitrem D (1) remains the only synthesis of any penitrem alkaloid to date, which highlights the complexity of the penitrem alkaloids. There are many noteworthy features in the total synthesis that are not discussed herein, such as a Sc(OTf)3-promoted cyclization cascade and a novel autoxidation to install the C22 hydroxyl group. Rather, as noted earlier, we focus our discussion on the indole synthesis methodology15 used to access the natural product. This method is a variant of the Madelung indole synthesis,16 albeit significantly more mild.

Scheme 1 depicts Smith's elegant indole synthesis and its use as a lynchpin in the total synthesis of 1. The transformation begins with the formation of N-TMS dianion species 3 by treatment of substituted 2-methylaniline 2 with n-BuLi and TMSCl, followed by s-BuLi. This highly reactive intermediate can be generated at low temperature, obviating the need for otherwise harsh conditions required in the Madelung reaction. The reactive intermediate 3, used in excess, is then treated with complex lactone 4 to form aminoketone 5 via concomitant addition/elimination of the alkyllithium with the lactone. Next, the authors found that subjection of 5 to silica gel led to the smooth formation of the desired 2-substituted indole, 6, in an impressive 81% yield from lactone 4. Thus, the Smith indole synthesis provides a powerful method to unite two fragments of considerable complexity, while also installing the necessary indole heterocycle.

Scheme 1. The Smith indole synthesis allows for the coupling of key fragments 2 and 4 en route to penitrem D (1).

The construction of the indole nucleus set the stage for the completion of the synthesis (Scheme 1). After eight additional steps, the Smith group succeeded in elaborating 6 to penitrem D (1). Smith's total synthesis of 1, which relies critically on his methodology for fragment coupling and indole synthesis, stands as one of the greatest feats in indole diterpenoid total synthesis.

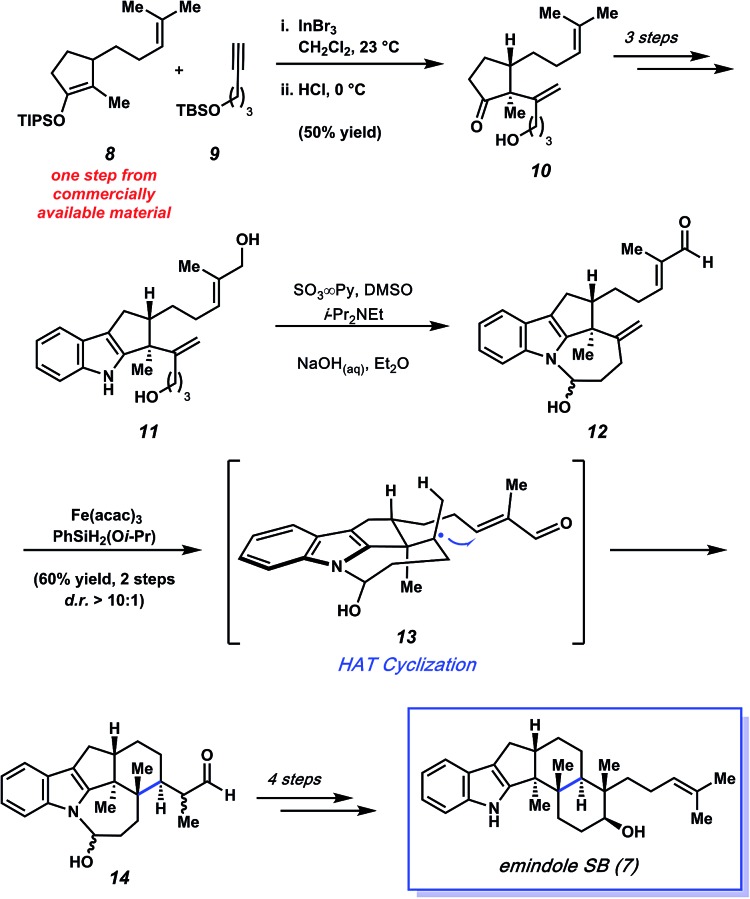

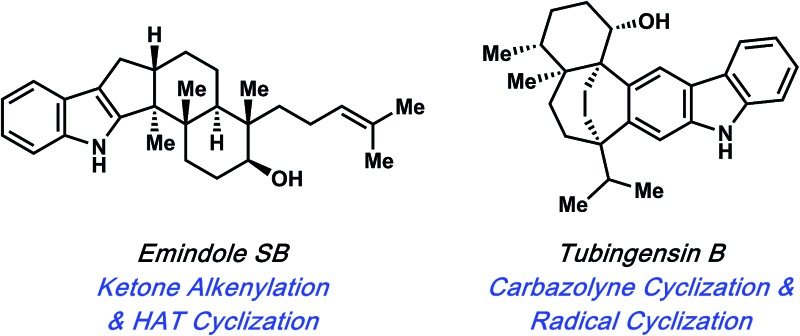

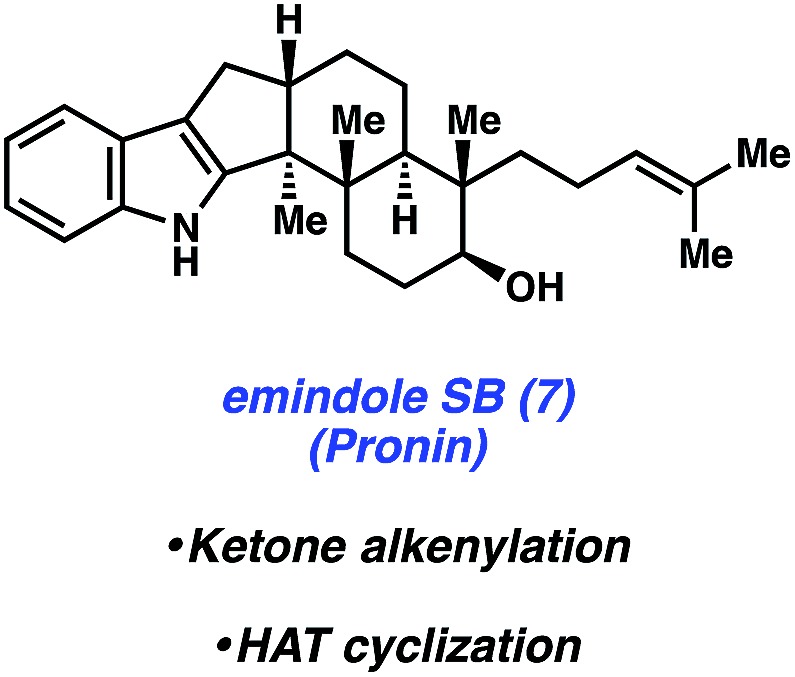

Pronin's synthesis of emindole SB

In 2015, Pronin and co-workers reported the first total synthesis of (±)-emindole SB (7, Fig. 3), an indole diterpenoid isolated from the fungus Emericella striata,8,17 that shows promising antiproliferative, antimigratory, and anti-invasive properties against human breast cancer cells.18 Comparable to penitrem D (1), the natural product contains an indole unit fused to a tricyclic carbon scaffold. Emindole SB (7) possesses six contiguous stereocenters, including vicinal quaternary centers on the western cyclohexyl ring. The Pronin group's approach to 7 features a novel ketone alkenylation reaction, in addition to a radical cyclization initiated by chemoselective hydrogen atom transfer (HAT) to install the trans-hexahydroindene moiety bearing vicinal quaternary centers.

Fig. 3. Emindole SB (7) and key strategies employed in Pronin's total synthesis.

As shown in Scheme 2, the synthesis of 7 commenced with silyl enol ether 8, which was prepared in one step from commercially available materials. Treatment of 8 with substoichiometric amounts of indium(iii) bromide in the presence of terminal alkyne 9,19,20 followed by a mild acidic workup, afforded alkenylated product 10 in 50% yield. Notably, an α-quaternary center was introduced with complete diastereoselectivity, showcasing the utility of this new method.

Scheme 2. Total synthesis of emindole SB (7) featuring a novel alkenylation reaction to afford 10 and an impressive HAT cyclization to furnish 14.

Ketone 10 was then elaborated in three steps to diol 11, an important precursor toward constructing the natural product's trans-hexahydroindene moiety (Scheme 2). Parikh–Doering oxidation21 of diol 11 provided hemiaminal 12 as the substrate for the ensuing key radical cyclization reaction. Using conditions developed independently by Baran and Shenvi, hemiaminal 12 was treated with iron(iii) acetylacetonate22 and (isopropoxy)phenylsilane23 to afford cyclized product 14 in 60% yield over two steps (from diol 11, >10 : 1 d.r.). This key radical cyclization, which constructs a new C–C bond and installs vicinal stereocenters, is thought to proceed by formation of tertiary radical intermediate 13 via chemoselective hydrogen atom transfer (HAT), followed by 1,4-addition. Of note, restricting the rotation of the radical intermediate by formation of a hemiaminal was crucial for the diasteroselectivity of the radical cyclization step. When the structure was not restricted as a hemiaminal, it resulted in the indiscriminate attack of the enone and poor diastereoselectivity. Nonetheless, pentacycle 14 was quickly elaborated to emindole SB (7) after a final four-step sequence involving cleavage of the hemiaminal fragment, cyclization to forge the final six-membered ring, and installation of the requisite homoprenyl group.

The Pronin approach to emindole SB (7) provides access to the natural product in only eleven steps from commercially available materials. Critical to the success and brevity of the total synthesis was creative invention. Specifically, the total synthesis of 7 was greatly facilitated by the novel alkenylation and diastereoselective radical cyclization reactions highlighted herein.

Johnson's total synthesis of paspaline

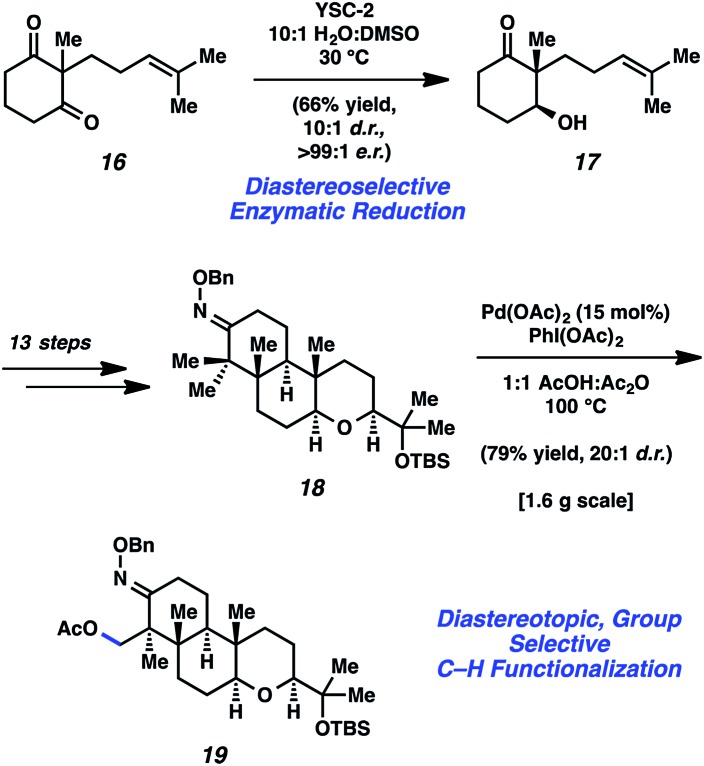

In 2015, Johnson and coworkers reported an enantioselective total synthesis of (–)-paspaline (15, Fig. 4).9 Paspaline (15) was isolated from the ergot fungus Claviceps paspali in 1966.24 The natural product's structure and bioactivity profile18 is similar to that of emindole SB (7), discussed previously, although 15 possesses an additional ring and rests in a higher oxidation state. Johnson's synthesis of paspaline (15) hinges on two impressive desymmetrization transformations: a biocatalytic desymmetrization and a diastereotopic group selective C–H acetoxylation.

Fig. 4. Paspaline (15) and summary of tactics used by Johnson to achieve the total synthesis.

The two desymmetrization reactions utilized in Johnson's synthesis of paspaline (15) are summarized in Scheme 3. The first involved desymmetrization of diketone 16. Biocatalytic reduction with yeast from Saccharomyces cerevisiae type 2 (YSC-2) furnished hydroxyketone 17 in 66% yield with excellent diastereo- and enantioselectivity.25 This enzymatic process was essential for the synthesis, as the stereochemistry in alcohol 17 would ultimately be transferred to the 2,6-cis-tetrahydropyran ring. Alcohol 17 was then converted into oxime 18, the substrate for the desired C–H acetoxylation. Inspired by chemistry developed in the Sanford laboratory,26 treatment of oxime 18 with palladium(ii) acetate and iodosobenzene diacetate produced acetate 19 in 79% yield (gram-scale) as a single diastereomer. It was hypothesized that the oxime directing group guided the palladium catalyst in proximity to the equatorial methyl group, resulting in diastereotopic, group selective C–H functionalization. This intriguing local desymmetrization approach to install a quaternary stereogenic center allowed access to the trans-hexahydroindene moiety present in the natural product.

Scheme 3. Enzymatic reduction and C–H functionalization creatively applied toward the total synthesis of paspaline (15).

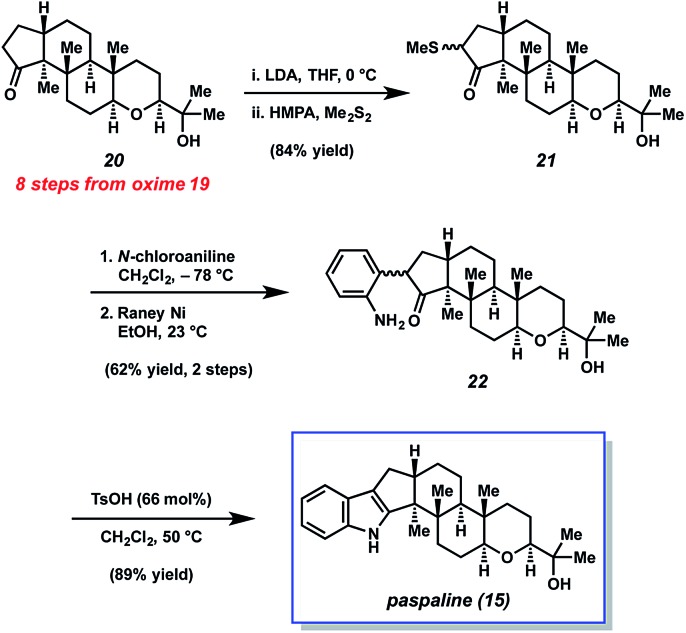

The endgame of Johnson's total synthesis of paspaline (15), which utilizes a Gassman indole synthesis,12a,27 is depicted in Scheme 4. Ketone 20, an intermediate derived from oxime 19 was first synthesized. Of note, 20 contains all the requisite stereocenters of the natural product. An enolate was then generated from ketone 20 and trapped with dimethyl disulfide to provide sulfide 21 in excellent yield. Next, sulfide 21 was treated with N-chloroaniline, followed by RANEY® nickel, to afford aniline 22 in 62% yield over two steps. Lastly, aniline 22 was treated with mild acid to generate the indole unit thereby completing the total synthesis of 15.

Scheme 4. Gassman indolization and completed synthesis of paspaline (15).

The Johnson synthesis of paspaline (15) showcases a number of elegant transformations. Central to the success of their approach was the clever utilization of desymmetrization reactions. The early enzymatic desymmetrization established two key stereocenters, including a challenging quaternary center. Subsequently, the judicious application of C–H functionalization chemistry produced a local desymmetrization event and installed another quaternary stereocenter. The execution of these processes not only facilitated the total synthesis of 15, but also underscores innovation prompted by the complexity of an indole diterpenoid.

Baran's synthesis of dixiamycin B

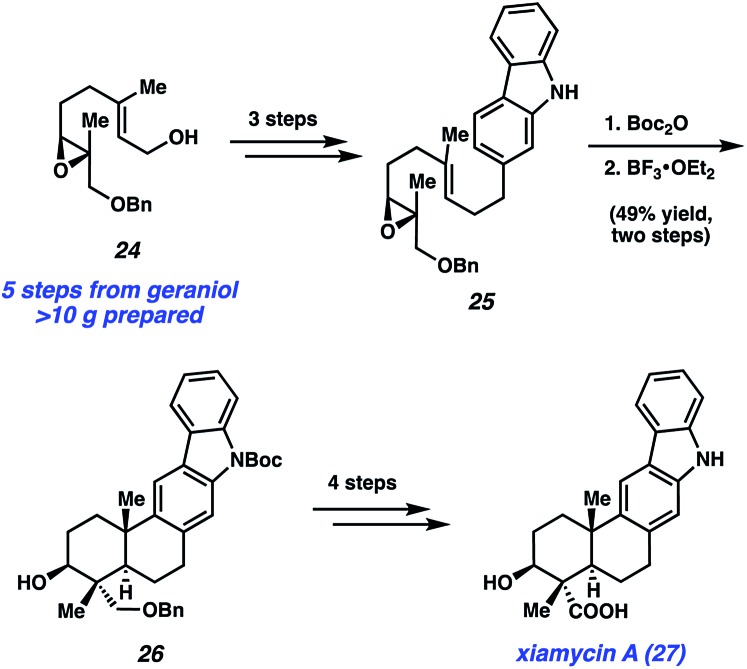

Dixiamycin B (23) is an oligomeric indole alkaloid that was isolated independently by Zhang and Hertweck from Streptomyces sp. SCSIO 02999 in 2012.28 The compound exhibits low μM antibacterial activity against several bacteria, including E. coli, S. auereus, B. subtilis, and B. thuringensis. Dixiamycin B (23) is a dimer of an indole diterpenoid, xiamycin A (27), which contains a carbazole fused to a trans-decalin core with four contiguous stereocenters, three of which are quaternary. In the dimerized natural product, the monomer units are uniquely linked via a N–N bond. Baran's laboratory tackled the total synthesis of dixiamycin B (23) by implementing a novel application of electrochemical oxidation to form this unusual bond (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5. Indole diterpenoid alkaloid dixiamycin B (23).

To validate their dimerization strategy, the group first tested oxidation methods on a simpler substrate, carbazole, to form the N–N bond. After examining chemical oxidants, which were largely deemed unfruitful, the authors turned to electrochemistry to facilitate the desired oxidative dimerization. Inspired by previous mechanistic electrochemical studies,29 they found that efficient dimerization of carbazole took place using a potential of +1.2 V with a carbon anode (i.e., 63% yield of carbazole dimer).

Armed with these results, they then embarked on the synthesis of the monomeric natural product, xiamycin A (27), as summarized in Scheme 5. The synthesis began with elaboration of epoxide 24, available in >10 g quantity in five steps from geraniol,30 to carbazole 25 in three steps. Boc protection, followed by treatment with BF3·OEt2, initiated a cationic polycyclization reaction, which established the core of the natural product. Of note, the product from this transformation, pentacycle 26, possesses the four contiguous stereocenters present in the natural product. From pentacycle 26, xiamycin A (27) was accessed in four steps involving removal of the Boc and Bn protecting groups, as well as oxidation to introduce the necessary carboxylic acid.

Scheme 5. Expedient synthesis of monomeric natural product xiamycin A (27).

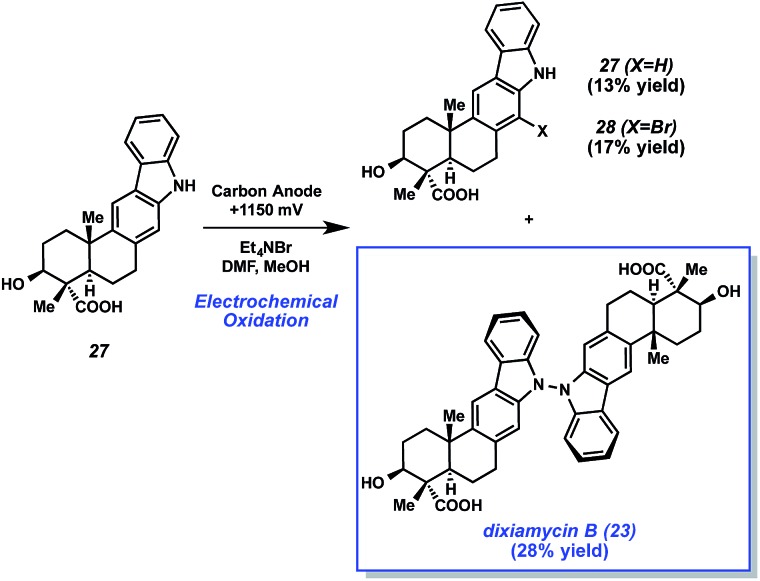

With xiamycin A (27) in hand, the authors attempted the critical dimerization reaction (Scheme 6). Upon subjection of xiamycin A (27) to electrochemical oxidation conditions involving 1.15 V using a carbon anode, the desired oxidative dimerization took place. Consequently, dixiamycin B (23) was obtained in 28% yield. The reaction also gave 13% of recovered starting material, along with 17% yield of brominated xiamycin derivative 28.

Scheme 6. Electrochemical oxidation forges key N–N bond of dixiamycin B (23).

With the success of the electrochemical dimerization reaction, not only did the Baran laboratory accomplish an expedient synthesis of an unusual natural product, but they also brought forth much deserved attention to the use of electrochemistry as an enabling tool in total synthesis.31 Numerous advances in electrochemical organic reactions have been disclosed,32 thus providing exciting tactics for chemists to consider when tackling challenging bond formations.

Garg's total syntheses of tubingensins A & B

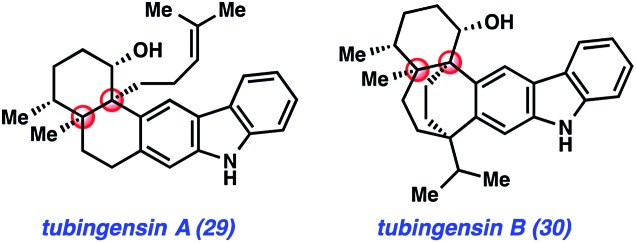

The final natural products highlighted in this minireview are tubingensin A (29) and tubingensin B (30) (Fig. 6). Due to their intriguing structures, these indole diterpenoids have sparked interest from the synthetic community. Both compounds were isolated from the fungus Aspergillus tubingensis by Gloer and coworkers in 1989 and display antiviral, anticancer, and insecticidal activity.33 Tubingensin A (29) has been the subject of previous synthetic studies,34 and has now been synthesized twice. The first synthesis was reported by Li and Nicolaou in 2012.6c Two years later, we described an enantiospecific route to the natural product.11a Recently, our laboratory completed the first total synthesis of tubingensin B (30).11b

Fig. 6. Tubingensins A (29) & B (30) featuring synthetically challenging vicinal quaternary centers.

Our lab first became interested in pursuing the total synthesis of the tubingensin alkaloids due to the structural complexity of these targets. Both compounds possess ortho-disubstituted carbazoles fused to intricate ring systems. In the case of tubingensin A (29), the natural product features four contiguous stereocenters, two of which are vicinal quaternary centers. Regarding tubingensin B (30), the natural product scaffold is significantly more complex due to the presence of the bicyclo[3.2.2]nonane core. In both cases, we viewed the natural product cores and the presence of quaternary centers as excellent testing grounds for aryne chemistry. Specifically, we questioned if carbazole-derived arynes, or ‘carbazolynes’ could be used to assemble the stereochemically complex frameworks present in the tubingensin alkaloids.

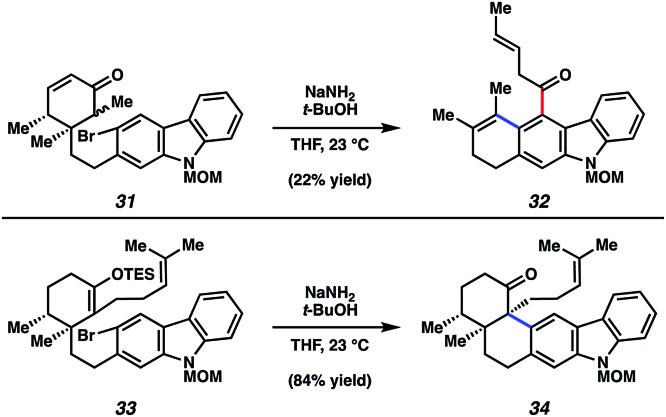

Although the discussion herein will largely focus on tubingensin B (30), some mention of carbazolyne cyclization studies in the context of tubingensin A (29) is warranted. In fact, considerable effort was required to find a substrate prone to undergo the desired carbazolyne cyclization. Two key results are depicted in Fig. 7. In the first, bromoketone 31, a model substrate lacking the homoprenyl sidechain, was treated with NaNH2/t-BuOH.35 These conditions, which are commonly used to generate arynes by dehydrohalogenation, were intended to facilitate both enolate formation and aryne formation en route to C–C bond construction. However, the major product obtained was tetracyclic ketone 32. This reaction is believed to proceed through the intended intermediate, which underwent formal [2 + 2] cycloaddition, followed by retro [4 + 2] reaction.11a Ultimately, the desired aryne cyclization was accomplished using TES enol ether 33 as the substrate. Exposure to NaNH2/t-BuOH furnished the desired pentacyclic ketone 34 in a gratifying 84% yield. Ketone 34 was then elaborated to the natural product, tubingensin A (29), in two additional steps.

Fig. 7. Attempted aryne cyclization to provide undesired adduct 32 and successful aryne cyclization to deliver ketone 34 en route to tubingensin A (29).

Having established the utility of aryne chemistry for the assembly of the tubingensin A scaffold, we directed our attention to the more complex family member, tubingensin B (30). In designing our synthesis, we envisioned the use of a carbazolyne cyclization to assemble a 7-membered ring. Aryne cyclizations to construct medium-sized rings are rare36 and no such examples involving the formation of vicinal quaternary stereocenters were available in the literature.

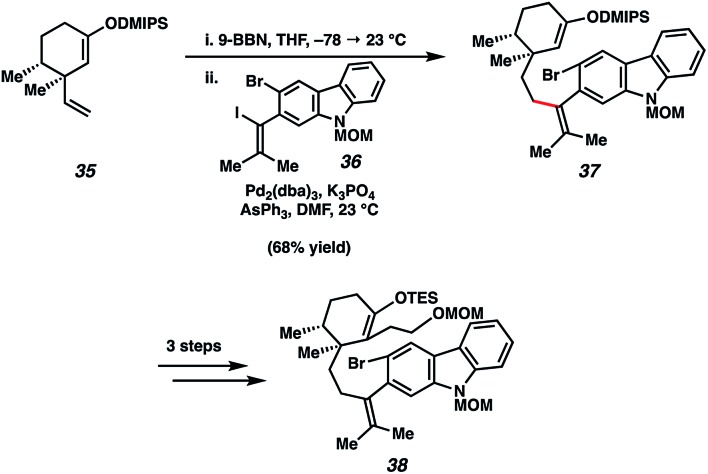

Our first major hurdle in the total synthesis of tubingensin B (29) was the construction of an appropriate aryne cyclization precursor. As shown in Scheme 7, our strategy involved B-alkyl Suzuki–Miyaura coupling of known olefin fragment 35 with vinyl iodide 36. Unification of these two fragments was far from trivial due to the congested nature of the tetrasubstituted olefin being formed, which is also positioned ortho to the aryl bromide. The necessary survival of the dimethylisopropylsilyl (DMIPS) enol ether added another layer of complexity to this transformation. After extensive optimization, we found that Pd2(dba)3 and AsPh3 facilitated the desired bond formation.37 In three steps, silyl enol ether 37 could be further elaborated to α-functionalized TES enol ether 38.

Scheme 7. Challenging B-alkyl Suzuki–Miyaura coupling affords tetrasubstituted olefin 37, which was subsequently converted to aryne cyclization substrate 38.

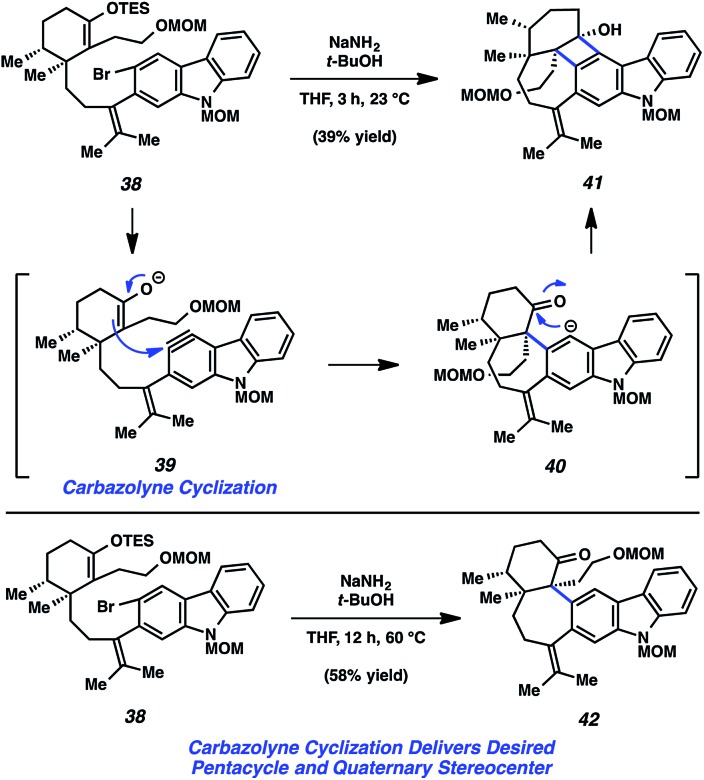

With TES enol ether 38 in hand, the key carbazolyne cyclization to form the seven-membered ring of the natural product was examined (Fig. 8). Exposure of 38 to NaNH2/t-BuOH was expected to result in enolate formation and dehydrohalogenation, with subsequent C–C bond formation. However, rather than obtaining the desired product, cyclobutenol 41 was observed. As expected, the desired enolate/aryne is first believed to form and undergo C–C bond formation (see transition structure 39). The resulting carbanion is thought to then cyclize onto the proximal ketone (see 40), thus giving rise to 41, rather than undergo protonation. It was ultimately found, however, that by performing the reaction at higher temperature, the desired product, ketone 42, could be accessed in 58% yield. Presumably, the formal [2 + 2] cycloaddition still occurs under these conditions, but the resulting intermediate undergoes in situ fragmentation to eventually give 42. Notably, this carbazolyne cyclization reaction establishes both the pentacyclic core and the vicinal quaternary centers of the natural product.

Fig. 8. Carbazolyne cyclization studies toward the total synthesis of tubingensin B (30).

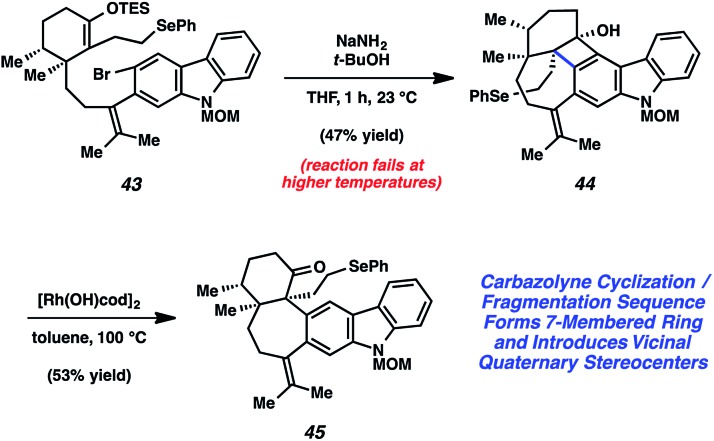

We were delighted to find that the carbazolyne cyclization provided access to ketone 42 and subsequently focused our efforts on elaborating 42 to the natural product. Although we were able to synthesize tubingensin B (30) from ketone 42, the route required several functional group interconversions and redox manipulations that we wished to circumvent. Thus, we redesigned our aryne precursor to include a different functional group handle in place of the MOM ether and eventually settled on selenide 43 (Scheme 8). Exposure of this substrate to NaNH2/t-BuOH afforded cyclobutenol 44. Unfortunately, attempts to induce in situ fragmentation by heating the reaction led to elimination of the alkyl selenide. Thus, we turned to the rhodium-catalyzed cyclobutenol ring opening conditions developed by Murakami and coworkers.38 Gratifyingly, subjection of cyclobutenol 44 to catalytic [Rh(OH)cod]2 in toluene at 100 °C led to the appropriate C–C bond cleavage to supply ketone 45.

Scheme 8. Carbazolyne cyclization/fragmentation sequence furnished ketone 45.

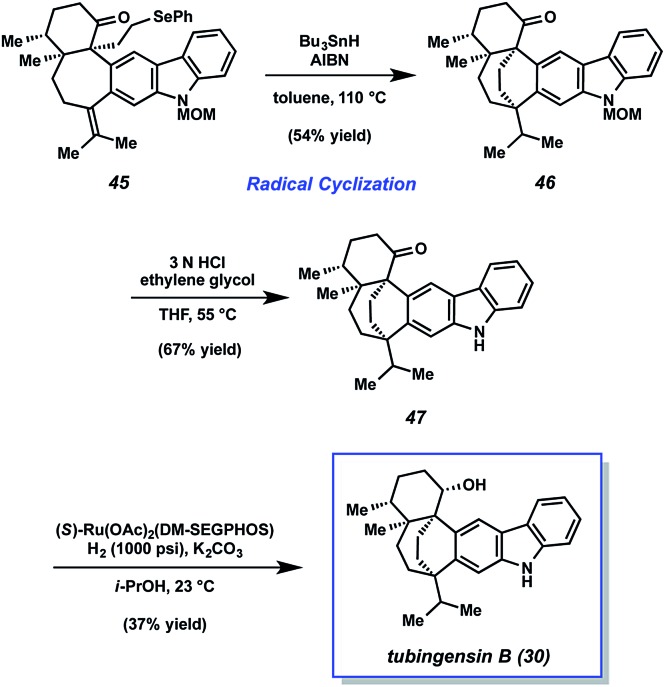

From alkyl selenide 45, completion of the total synthesis of tubingensin B (30) was achieved using the sequence highlighted in Scheme 9. Exposure of selenide 45 to tributyltin hydride and AIBN in toluene at 110 °C resulted in the desired radical cyclization39 to give product 46 in 54% yield. Of note, this reaction installed the bicyclo[3.2.2]nonane core and the final C–C bond of the natural product. From 46, all that remained was deprotection of the carbazole nitrogen and reduction of the ketone. Treatment of N-MOM ketone 46 with 3 N HCl and ethylene glycol at 55 °C delivered ketone 47 in 67% yield. Although diastereoselective ketone reduction proved difficult, an exhaustive survey of conditions led us to identify suitable conditions. Treatment of ketone 47 to (R)-Ru(OAc)2(DM-SEGPHOS), KOH, and H2 (1500 psi) gave synthetic tubingensin B (30).40

Scheme 9. Radical cyclization, deprotection, and late-stage reduction furnishes tubingensin B (30).

The concise total syntheses of tubingensin A (29) and tubingensin B (30) were made possible by the strategic use of aryne chemistry. More specifically, the carbazolyne cyclizations facilitated construction of the pentacyclic cores and installed the vicinal quaternary stereocenters of the natural products. The synthesis of tubingensin B (30) was further enabled by (a) the Rh-catalyzed fragmentation of an unexpected cyclobutenol intermediate and (b) a late-stage radical cyclization stemming from a phenylselenide intermediate to install a final quaternary stereocenter and the [3.2.2]-bridged bicyclic framework of the natural product. These results underscore the fact that arynes, despite often being considered ‘too reactive’ and therefore undesirable, can be used strategically to access challenging structural motifs, such as medium-sized rings and vicinal quaternary stereocenters.

Conclusions

In this minireview, we have demonstrated that indole diterpenoid natural products serve as excellent stepping-stones for innovation in chemical synthesis. Penitrem D, arguably the most complex member of this natural product family, featured the Smith indole synthesis, as a means to not only introduce the indole unit, but also to couple two complex fragments. The synthesis of emindole SB from the Pronin group showcased the development of a new ketone alkenylation protocol, as well as an elegant application of hydrogen atom transfer chemistry in total synthesis. Johnson's synthesis of paspaline demonstrated clever use of desymmetrization reactions in the context of an enzymatic reduction and a C–H functionalization to install stereochemical complexity. Moreover, through the synthesis of dixiamycin B, the Baran laboratory has shown that electrochemistry can be a powerful complement to traditional chemical oxidants. Finally, our laboratory's forays toward the tubingensin alkaloids have demonstrated the effectiveness of heterocyclic aryne chemistry in building stereochemically complex molecules, including vicinal quaternary centers. We envision that indole diterpenoids will continue to foster creativity in chemical synthesis for years to come.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the National Science Foundation (graduate fellowship for MAC; DGE-1144087) and the University of California, Los Angeles for financial support.

Biographies

Michael A. Corsello

Michael Corsello was born in Philadelphia, PA in 1990. He received his B.S. in Biochemistry from Rowan University, where he performed undergraduate research with Professor Subash C. Jonnalagadda on the synthesis of small molecules as potential anticancer and antifungal agents. In the summer of 2012, he began his graduate studies at the University of California, Los Angeles. He recently completed his Ph.D. in the laboratory of Professor Neil K. Garg, pursuing the total synthesis of tubingensin natural products.

Junyong Kim

Junyong Kim was born in Seoul, South Korea in 1988. He received his B.S. in Chemistry from Seoul National University, where he performed undergraduate research with Professor David Y.-K. Chen on the total synthesis of dendrobine. In the summer of 2013, he began his graduate studies at the University of California, Los Angeles. He is currently a fourth year graduate student in the laboratory of Professor Neil K. Garg, pursuing the total synthesis of tubingensin natural products and nickel-catalyzed reaction methodologies.

Neil K. Garg

Neil Garg is a Professor of Chemistry at the University of California, Los Angeles. Professor Garg received a B.S. degree in Chemistry from New York University where he carried out undergraduate research with Professor Marc Walters. During his undergraduate years, he spent several months in Strasbourg, France conducting research with Professor Wais Hosseini at the Université Louis Pasteur as an NSF REU Fellow. Subsequently, he obtained his Ph.D. degree in 2005 from the California Institute of Technology under the direction of Professor Brian Stoltz. He then spent two years in Professor Larry Overman's research laboratory at the University of California, Irvine as an NIH Postdoctoral Scholar. Professor Garg started his independent career at UCLA in 2007, where his laboratory develops synthetic strategies and methodologies to enable the total synthesis of complex bioactive molecules.

References

- Jordan M. A., Wilson L. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2004;4:253. doi: 10.1038/nrc1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For reviews of indole terpenoid synthesis, see: ; (a) Ishikura M., Yamada K. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2009;26:803. doi: 10.1039/b820693g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Ishikura M., Yamada K., Abe T. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2010;27:1630. doi: 10.1039/c005345g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Ishikura M., Abe T., Choshib T., Hibinob S. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2013;30:694. doi: 10.1039/c3np20118j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Marcos I. S., Moro R. F., Costales I., Basabe P., Díez D. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2013;30:1509. doi: 10.1039/c3np70067d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Baunach M., Franke J., Hertweck C. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015;54:2604. doi: 10.1002/anie.201407883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornfeld E. C., Fornefeld E. J., Kline G. B., Mann M. J., Morrison D. E., Jones R. G., Woodward R. B. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1956;78:3087. [Google Scholar]

- Sears J. E., Boger D. L., Acc. Chem. Res., 2015, 48 , 653 , , and references therein . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Enomoto M., Morita A., Kuwahara S. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012;51:12833. doi: 10.1002/anie.201206299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Teranishi T., Murokawa T., Enomoto M., Kuwahara S. Biosci., Biotechnol., Biochem. 2015;79:11. doi: 10.1080/09168451.2014.955455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Zhou S., Zhang D., Sun Y., Li R., Zhang W., Li A. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2014;356:2867. [Google Scholar]; (b) Xiong X., Zhang D., Li J., Sun Y., Zhou S., Yang M., Shao H., Li A. Chem.–Asian J. 2015;10:869. doi: 10.1002/asia.201403312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Bian M., Wang Z., Xiong X., Sun Y., Matera C., Nicolaou K. C., Li A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:8078. doi: 10.1021/ja302765m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Sun Y., Meng Z., Chen P., Zhang D., Baunach M., Hertweck C., Li A., Org. Chem. Front., 2016, 3 , 368 , , and references therein . [Google Scholar]

- (a) Smith III A. B., Kanoh N., Ishiyama H., Hartz R. A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:11254. [Google Scholar]; (b) Smith III A. B., Kanoh N., Ishiyama H., Minakawa N., Rainier J., Hartz R. A., Cho Y. S., Cui H., Moser W. H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:8228. doi: 10.1021/ja034842k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George D. T., Kuenstner E. J., Pronin S. V. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015;137:15410. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b11129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Sharpe R. J., Johnson J. S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015;137:4968. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b02631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Sharpe R. J., Johnson J. S. J. Org. Chem. 2015;80:9740. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.5b01844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen B. R., Werner E. W., O'Brien A. G., Baran P. S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:5571. doi: 10.1021/ja5013323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Goetz A. E., Silberstein A. L., Corsello M. A., Garg N. K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:3036. doi: 10.1021/ja501142e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Corsello M. A., Kim J., Garg N. K. Nat. Chem. 2017 doi: 10.1038/nchem.2801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Smith III A. B., Mewshaw R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1985;107:1769. [Google Scholar]; (b) Smith III A. B., Sunazuka T., Leenay T. L., Kingery-Wood J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990;112:8197. [Google Scholar]; (c) Smith III A. B., Leenay T. L. Tetrahedron Lett. 1988;29:2787. [Google Scholar]; (d) Smith III A. B., Leenay T. L. Tetrahedron Lett. 1988;29:2791. [Google Scholar]; (e) Mewshaw R. E., Taylor M. D., Smith III A. B. J. Org. Chem. 1989;54:3449. [Google Scholar]; (f) Smith III A. B., Leenay T. L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1989;111:5761. [Google Scholar]; (g) Smith III A. B., Kingery-Wood J., Leenay T. L., Nolen E. G., Sunazuka T. J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992;114:1438. [Google Scholar]; (h) Rainier J. D., Smith III A. B. Tetrahedron Lett. 2000;41:9419. [Google Scholar]; (i) Smith III A. B., Cui H. Org. Lett. 2003;5:587. doi: 10.1021/ol027575g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (j) Zou Y., Melvin J. E., Gonzales S. S., Spafford M. J., Smith III A. B. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015;137:7095. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b04728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jesus A. E., Steyn P. S., van Heerden F. R., Vleggaar R., Wessels P. L., Hull W. E. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1. 1983:1847. [Google Scholar]

- Knaus H.-G., McManus O. B., Lee S. H., Schmalhofer W. A., Garcia-Calvo M., Helms L. M. H., Sanchez M., Giangiacomo K., Reuben J. P., Smith III A. B., Kaczorowski G. J., Garcia M. L. Biochemistry. 1994;33:5819. doi: 10.1021/bi00185a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith III A. B., Visnick M. Tetrahedron Lett. 1985;26:3757. [Google Scholar]

- Madelung W. Ber. Dtsch. Chem. Ges. 1912;45:1128. [Google Scholar]

- Nozawa K., Nakajima S., Kawai K.-i. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1. 1988:2607. [Google Scholar]

- Sallam A. A., Houssen W. E., Gissendanner C. R., Orabi K. Y., Foudah A. I., El Sayed K. A. MedChemComm. 2013;4:1360. doi: 10.1039/C3MD00198A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimoto Y., Moritoh R., Yasuda M., Baba A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009;48:4577. doi: 10.1002/anie.200901417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmbo S. D., Godfrey N. A., Hirner J. J., Pronin S. V. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016;138:12316. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b06847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parikh J. R., Doering W. E. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1967;89:5505. [Google Scholar]

- (a) Lo J. C., Yabe Y., Baran P. S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:1304. doi: 10.1021/ja4117632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Lo J. C., Gui J., Yabe Y., Pan C.-M., Baran P. S. Nature. 2014;516:343. doi: 10.1038/nature14006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obradors C., Martinez R. M., Shenvi R. A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016;138:4962. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b02032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fehr T., Acklin W. Helv. Chim. Acta. 1966;49:1907. doi: 10.1002/hlca.19750580829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Watanabe H., Iwamoto M., Nakada M. J. Org. Chem. 2005;70:4652. doi: 10.1021/jo050349a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Katoh T., Mizumoto S., Fudesaka M., Nakashima Y., Kajimoto T., Node M. Synlett. 2006:2176. [Google Scholar]; (c) Katoh T., Mizumoto S., Fudesaka M., Takeo M., Kajimoto T., Node M. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2006;17:1655. [Google Scholar]

- (a) Desai L. V., Hull K. L., Sanford M. S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:9542. doi: 10.1021/ja046831c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Neufeldt S. R., Sanford M. S. Org. Lett. 2010;12:532. doi: 10.1021/ol902720d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gassman P. G., van Bergen T. J., Gilbert D. P., Cue Jr B. W. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1974;96:5495. [Google Scholar]

- (a) Zhang Q., Mańdi A., Li S., Chen Y., Zhang W., Tian X., Zhang H., Li H., Zhang W., Zhang S., Ju J., Kurtań T., Zhang C. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2012:5256. [Google Scholar]; (b) Xu Z., Baunach M., Ding L., Hertweck C. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012;51:10293. doi: 10.1002/anie.201204087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Ambrose J. F., Carpenter L. L., Nelson R. F. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1975;122:876. [Google Scholar]; (b) Bobbitt J. M., Kuljarni C. L., Willis J. P. Heterocycles. 1981;15:495. [Google Scholar]; (c) Berti C., Greci L., Andruzzi R., Trazza A. J. Org. Chem. 1985;50:368. [Google Scholar]

- Tanis S. P., Chuang Y.-H., Head D. B. J. Org. Chem. 1988;53:4929. [Google Scholar]

- (a) Liu B., Duan S., Sutterer A. C., Moeller K. D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:10101. doi: 10.1021/ja026739l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Mihelcic J., Moeller K. D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:36. doi: 10.1021/ja029064v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Hughes C. C., Miller A. K., Trauner D. Org. Lett. 2005;7:3425. doi: 10.1021/ol047387l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Xu H.-C., Brandt J. D., Moeller K. D. Tetrahedron Lett. 2008;49:3868. [Google Scholar]

- (a) Moeller K. D. Tetrahedron. 2000;56:9527. [Google Scholar]; (b) Horn E. J., Rosen B. R., Baran P. S. ACS Cent. Sci. 2016;2:302. doi: 10.1021/acscentsci.6b00091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) TePaske M. R., Gloer J. B., Wicklow D. T., Dowd P. F. J. Org. Chem. 1989;54:4743. [Google Scholar]; (b) TePaske M. R., Gloer J. B., Wicklow D. T., Dowd P. F. Tetrahedron Lett. 1989;30:5965. [Google Scholar]

- Bradshaw B., Etxebarria-Jardí G., Bonjoch J. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2008;6:772. doi: 10.1039/b718280e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caubere P. Acc. Chem. Res. 1974;7:301. [Google Scholar]

- (a) Tadross P. M., Stoltz B. M. Chem. Rev. 2012;112:3550. doi: 10.1021/cr200478h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Boente J. M., Castedo L., Rodriguez de Lera A., Saá J. M., Suau R., Vidal M. C. Tetrahedron Lett. 1983;24:2295. [Google Scholar]; (c) Huters A. D., Quasdorf K. W., Styduhar E. D., Garg N. K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:15797. doi: 10.1021/ja206538k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kojima A., Honzawa S., Boden C. D. J., Shibasaki M. Tetrahedron Lett. 1997;38:3455. [Google Scholar]

- Ishida N., Sawano S., Masuda Y., Murakami M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:17502. doi: 10.1021/ja309013a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clive D. L. J., Cole D. C., Tao Y. J. Org. Chem. 1994;59:1396. [Google Scholar]

- Tang W., Zhang X. Chem. Rev. 2003;103:3029. doi: 10.1021/cr020049i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]