Abstract

Background

These ‘Social determinants of heath’ (SDH) are non-clinical factors that profoundly impact health. Helping community health centers (CHCs) document patients’ SDH data in electronic health records (EHRs) could yield substantial health benefits, but little has been reported about CHCs’ development of EHR-based tools for SDH data collection and presentation.

Methods

We worked with 27 diverse CHC stakeholders to develop strategies for optimizing SDH data collection and presentation in their EHR, and approaches to integrating SDH data collection and use (e.g., through referrals to community resources) into CHC workflows.

Results

We iteratively developed a set of EHR-based SDH data collection, summary, and referral tools for CHCs. We describe considerations that arose during the tool development process, and present a number of preliminary lessons learned.

Discussion

Standardizing SDH data collection and presentation in EHRs could lead to improved patient and population health outcomes in CHCs and other care settings. We know of no previous reports on processes used to develop EHR-based SDH data tools. This paper provides an example of one such process.

Conclusion

Lessons from our process may be useful to healthcare organizations interested in using EHRs to collect and act on SDH data. Research is needed to empirically test the generalizability of these lessons.

Background

Numerous health outcomes are influenced by the social and physical characteristics of patients’ lives. These ‘social determinants of heath’ (SDH) can affect health via diverse mechanisms (e.g., chronic stress; hampering patients’ ability to follow care recommendations).1 This impact is so great that addressing SDH may improve health as much as addressing patients’ medical needs.2-21

The Institute of Medicine (IOM) recommended that 10 patient-reported SDH domains (and one neighborhood / community-level domain) be documented in electronic health records (EHR); Table 1.22,23 These domains were selected based on: evidence of their health impacts; their potential clinical usefulness and actionability; and the availability of valid measures. Some of these domains are already regularly collected by federally funded clinics (e.g., race/ethnicity); others are not (e.g., social isolation, financial resource strain). The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) intended that the IOM’s report inform Stage 3 Meaningful Use EHR incentive program requirements. Related to this, the Medicare Access & CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 and CMS’ 2016 Quality Strategy both emphasize care providers identifying and intervening on SDH-related needs, and the Health Resources and Services Administration and the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology have both indicated that SDH data collection should continue to expand as part of Federally Qualified Health Center reporting, and may become required for EHR certification.24-29

Table 1. IOM Phase 2 Report.

Summary of Candidate Domains for Inclusion in all EHRs

| Race / ethnicity* |

| Education |

| Financial resource strain |

| Stress |

| Depression* |

| Physical activity |

| Nicotine use / exposure* |

| Alcohol use* |

| Social connections / social isolation |

| Exposure to violence: Intimate partner violence |

| Neighborhood characteristics (e.g., census-tract median income) |

Already routinely captured in EHRs

Systematically documenting patients’ SDH data in EHRs could help care teams incorporate this information into patient care, e.g., by facilitating referrals to community resources to address identified needs. This could be especially useful in ‘safety net’ community health centers (CHCs), whose patients have higher health risks than the general US population.23,30-39 Many CHCs already try to address patients’ SDH, but their approaches to doing so have historically been manual and ad-hoc.40-44

EHRs present an opportunity to standardize the collection, presentation, and integration of SDH data in CHCs’ clinical records.45 Towards that end, a national coalition of CHC-serving organizations created the ‘Protocol for Responding to and Assessing Patient Assets, Risks, and Experiences’ (PRAPARE), which included a preliminary SDH data collection tool informed by the IOM’s Phase 1 report.45 PRAPARE includes most of the IOM-recommended domains, and a few additional questions specific to CHC populations. Building on PRAPARE and the IOM recommendations, our study team asked CHC stakeholders’ opinions on how to optimize SDH data collection, documentation and presentation in CHCs’ EHRs, and on how they would like to use EHR tools to act on identified SDH-related needs, e.g., by making referrals to community resources. This paper describes our process, and its results. As we know of no previously published reports on processes used to develop EHR-based SDH data collection, summary, and referral tools, we present this paper as an example that may be informative to others.

Methods

This work was conducted at OCHIN, a non-profit community-based organization that centrally hosts and manages an Epic© EHR for >440 primary care CHCs in 19 states; it is the nation’s largest CHC network on a single EHR system. OCHIN member CHCs’ patients’ socioeconomic risks are clear from SDH data that are already collected: 23% are uninsured and 58% are publicly insured, 25% are non-white, 33% of Hispanic ethnicity, 28% primarily non-English speakers, and 91% from households <200% of the Federal Poverty Level (among patients with available data).

The processes described here constituted the first phase of a pilot study (R18DK105463) designed to develop EHR-based tools that CHCs could use to systematically identify and act on their patients’ SDH-related needs. We call these the ‘SDH Data Tools.’

With the goal of creating SDH-related workflows that parallel clinical referral processes, we began with the assumption that there are five key steps in addressing patients’ SDH needs: 1. Collecting SDH data; 2. Reviewing patients’ SDH-related needs; 3. Identifying referral options to address those needs; 4. Ordering referrals to appropriate services; and 5. Tracking outcomes of past referrals. This assumption was based on team members’ knowledge of the CHC workflows used to refer patients to specialty medical care.

We also considered the following factors:

CHCs are federally required to collect certain SDH measures from the IOM list, including race / ethnicity, tobacco / alcohol use, and depression. Our SDH data tools had to incorporate these data, without requiring duplicate data entry.

CHCs have varying staffing structures, resources, and workflows. To accommodate this, SDH data tools should be accessible to various team members (e.g., front desk, MAs, Community Health Workers, Behavioral Health staff).

SDH tools should use existing EHR-based functionalities, to facilitate their adoption. The options that we initially considered to address each of these five steps are shown in Table 2.

Many CHCs already identify / address SDH needs using ad-hoc methods. Some may already have mechanisms for tracking local resources, such as a 3-ring binder or files on a shared drive; some use online resources (e.g., United Way 2-1-1, local department of human services, etc.). We sought to incorporate existing resources into our SDH referral tools.

Table 2. Options considered for addressing each of the five steps involved in using SDH data in CHCs.

| Step | Options |

|---|---|

| 1: Collecting SDH data |

|

| |

| |

| 2: Reviewing SDH needs, and 5: Tracking past referrals |

|

| |

| |

| 3: Identifying referral options, and 4: Ordering referrals |

|

| |

| |

| |

|

We recruited three OCHIN CHCs in Oregon and Washington as pilot sites and project partners. We also engaged OCHIN’s Clinical Operations Review Committee (CORC) – a group of CHC clinicians who collectively review proposed changes to their shared EHR – in all process steps. We also conferred with leaders from PRAPARE, Kaiser Permanente (KP), Epic©, and other national SDH experts; see Acknowledgments. These stakeholders were asked to discuss three overarching questions:

Which SDH domains should be included? The CORC reviewed the IOM-recommended SDH domains and wording for each domain, additional questions or alternate wording from PRAPARE and KP’s SDH screening tools, and other domains currently collected in OCHIN’s EHR that were not in the IOM / PRAPARE recommendations. Based on these options, they chose which patient-reported SDH measures to include and the specific wording for each included domain. Geocoded domains were not considered, as the CORC felt they were not readily actionable. The pilot CHCs were present at most of the SDH-related CORC meetings.

-

How do care teams want to collect, review, and act on data on patients’ SDH needs within the EHR? We asked CORC members whether and how their clinics monitor patients’ SDH, and what the SDH-related EHR tools should include. We presented options for how the SDH data could be collected and summarized using existing EHR structures, and considered how existing tools aligned with the five key steps described above. We then mocked-up a set of SDH data EHR tools and proposed workflows for using them. We presented the mock-ups and draft training materials to the CORC over multiple meetings, and to each of the pilot CHCs at staff meetings. We asked diverse CHC staff for critical feedback on the draft tools, suggestions for and potential barriers to collecting / acting on SDH data using the tools, and how best to train CHC staff in their use. Our team’s Epic programmer attended these meetings to provide real-time input about the technical feasibility of any suggestions. The SDH data tools were revised based on the feedback received, and consideration of the pilot CHCs’ various workflows and staff structures. The revised tools were presented to the CORC (in person) and the study sites (via webinar) to verify that the revisions addressed requested changes.

This review and refinement process aligns with best practices for technology development,46 e.g., user participation and prototyping.47-54 Evidence shows that for technology to be used effectively and as intended, end users must find it easy to use, and must perceive that the technology will improve efficiency.55-57 Therefore, we sought end user input to increase the probability that the tools would be used.46 The EHR tools were then built in OCHIN’s testing environment, an off-line, internal ‘copy’ of the EHR, and tested by an OCHIN quality assurance analyst.

How can care teams ensure that patients receive up-to-date referrals? The CHCs hoped to avoid referring patients to local resources that were not currently accepting new clients (service agencies sometimes close enrollment due to demand), or that had limitations about who could be assisted (e.g., some services are not open to persons with past felonies). We discussed the options and approaches for identifying resources described above. We also conferred with colleagues at KP who were considering similar choices, and spoke with representatives from organizations that create databases of community resource information (e.g., United Way 2-1-1, Health Leads and Purple Binder) to understand those options. The three pilot clinics then identified 3-5 prioritized SDH domains for which they wanted a list of community resources; based on these preferences, we provided lists of local resources for housing, food, transportation, social isolation, and intimate partner violence.

Participants

Participants from our study clinics consisted of: primary care providers (N=3), medical assistants (N=5), clinic managers (N=3), community health workers (N=4), behavioral health staff (N=2), nurses (N=5), referral specialists (N=3), EHR specialists (N=3), and medical directors (N=2).

Timeline

The development process took ten months. Five one-hour meetings with the CORC were held over the course of six months, to reach consensus on which SDH domains to include and tool functionality. The pilot sites were then given six weeks to test the tools for functional errors.

Results

Which SDH measures?

Our stakeholders asked that the SDH tools include all of the patient-reported IOM-recommended domains, made minor adaptations to the wording on some of these domains, and added a few questions (Tables 1, 3). For example, the IOM’s single question on financial resource strain asks “How hard is it for you to pay for the very basics like food, housing, heating, medical care, and medications? (Not hard at all, Somewhat hard, Very hard).” Because CHCs treat low-income patients, many of whom were likely to screen positive for financial hardship, the CHC stakeholders wanted to augment this broad question with more granular questions about specific areas of strain (e.g., food, utilities, transportation, etc.). The hope was that this granularity would identify the specific areas in which assistance was needed. The stakeholders also preferred to not use the IOM-recommended screening tool for intimate partner violence, considering its questions too sensitive for general SDH screening. They opted for a broader question about exposure to violence, from KP’s SDH questionnaire. They also opted to add two questions on social isolation from KP’s questionnaire (e.g., “How often do you feel lonely or isolated from those around you?”; “Do you have someone you could call if you needed help?”), along with the IOM-recommended questions on social isolation. They also added a question on preferred learning style (e.g., reading, listening, pictures).

Table 3.

SDH domains and measures included in ASSESS tool and overlap with IOM-recommended domains and measures

| SDH Domain | IOM-recommended measure / questions | Same in PRAPARE? | ASSESS question (if different from IOM) | Potential actions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Alcohol use*ˆ | AUDIT-C (3Q) | Not included. | Already included in OCHIN EHR. | Refer to addiction services |

| How often do you have a drink containing alcohol? (Never / Monthly or less / 2-4 times a month / 2-3 times a week / 4 or more times a week) | How many (and what type of) drinks do you have per week? (# Cans of beer / # Glasses of wine / # Shots of liquor / # Standard drinks or equivalent) | |||

| How many standard drinks containing alcohol do you have on a typical day? (1 or 2 / 3 or 4 / 5 or 6 / 7 to 9 / 10 or more) | ||||

| How often do you have four or more drinks on one occasion? (Never / Less than monthly / Monthly / Weekly / Daily or almost daily) | ||||

|

| ||||

| Race/ethnicity*ˆ | US Census (2Q) | Which race(s) are you? Check all that apply. | Already included in OCHIN EHR. | |

| What is this person’s race? (White; Black, African American, or Negro; American Indian or Alaska Native ; Asian Indian / Chinese / Filipino / Japanese / Korean / Vietnamese / Other Asian / Native Hawaiian / Guamanian or Chamorro / Samoan / Other Pacific Islander / Some other race) | (American Indian or Alaskan Native / Asian / Black or African American / Native Hawaiian / Pacific Islander / White / Other) | Race: (Alaskan Native / American Indian / Asian / Black / Native Hawaiian / Pacific Islander / Patient refused / Unknown / White) | ||

| Ethnicity: (Hispanic / Non-Hispanic / Patient refused / Unknown) | ||||

| Is this person of Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish Origin? (No / Yes, Mexican, Mexican American, Chicano / Yes, Puerto Rican / Yes, Cuban / Yes, another Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish origin) | Are you Hispanic or Latino? (Yes / No / Unreported or refused) | |||

|

| ||||

| Tobacco use and exposure*ˆ | NHIS (2Q) | Not included. | Already included in OCHIN EHR. | Refer to quit services |

| Have you smoked at least 100 cigarettes in your entire life? (Yes / No / Refused / Don’t know) | Smoking status: (Current every day smoker / Current some day smoker / Former smoker / Heavy tobacco smoker / Light tobacco smoker / Never assessed / Never smoker / Passive smoke exposure – never smoker / Smoker, current status unknown / Unknown if ever smoked) | |||

| Do you NOW smoke cigarettes every day, some days or not at all? (Every day / Some days / Not at all / Refused / Don’t know) | ||||

| Smokeless tobacco: (Current user / Former user / Never used / Unknown) | ||||

|

| ||||

| Depression*ˆ | PHQ-2 (2Q) | Not included. | Already included in OCHIN EHR. Same as IOM. | Refer to mental health services |

| Over the past 2 weeks, how often have you been bothered by any of the following problems: | ||||

| Little interest or pleasure in doing things (Not at all / Several days / More than half the days / Nearly every day) | ||||

| Feeling down, depressed or hopeless (Not at all / Several days / More than half the days / Nearly every day) | ||||

|

| ||||

| Education* | What is the highest level and years of school completed? (Elementary / High School / College / Graduate or Professional – check years completed) | What is the highest level of school that you have finished? (Less than high school / High school diploma or GED / More than high school / I choose not to answer this question) | Adapted IOM wording to be aligned with PRAPARE and more relevant to safety net populations. | Identify patients needing more intensive care management, targeted forms of outreach, or for whom teams should consider “teach back” methods, tailored handouts, etc. |

| What is the highest degree you earned? (High school diploma / GED / Vocational certificate / Associate degree (occupational, technical, or vocation program) / Associate degree (academic program) / Bachelor’s degree / Master’s degree / Professional / Doctorate) | ||||

| Refer to education services (GED / skills training) | ||||

|

| ||||

| Exposure to violence: intimate partner violence* | HARK (4Q) | In the past year, have you been afraid of your partner or ex-partner? (Yes / No) | Per recommendations of our stakeholder group, we included a more general question on violence that is aligned with Kaiser Permanente’s “Your Current Life Situation (YCLS) questionnaire. | Refer to IPV intervention services |

Within the past year, have you been:

|

Do you feel physically and emotionally safe where you currently live? (Yes / No) | Have you ever been physically or emotionally hurt or threatened by a spouse/partner or someone else you know? (Yes / No) | ||

| (Yes / No) | ||||

| Within the last year, have you been kicked hit, slapped, or otherwise physically hurt by your partner or ex-partner? (Yes / No) | In addition, the CORC opted to include the 4-item validated HITS (Hurt-Insult-Threaten-Scream) domestic violence screening tool67,68 in the OCHIN EHR. This question will not be part of the SDH flowsheet, but positive responses will be pulled into the SDH summary and synopsis. | |||

How often does your partner:

|

||||

| (Never / Rarely / Sometimes / Fairly Often / Frequently) | ||||

|

| ||||

| Physical activity* | Exercise Vital Signs (2Q) | Not included. | Same as IOM. | Refer to local physical activity resources (e.g., YMCA; Parks and Recreation services) |

| On average, how many days per week do you engage in moderate to strenuous exercise (like walking fast, running, jogging, dancing, swimming, biking, or other activities that cause a light or heavy sweat)? On average, how many minutes do you engage in exercise at this level? | ||||

|

| ||||

| Social connections & social isolation* | NHANES III | How often do you see or talk to people that you care about and feel close to? (For example: talking to friends on the phone, visiting friends or family, going to church or club meetings) (Less than once a week / 1 or 2 times a week / 3 to 5 times a week / more than 5 times a week / I choose not to answer this question) | Same as IOM. Plus, per the recommendation of our stakeholders, we added an additional response to the NHANES question on weekly social contacts to encompass alternative forms of communication. | Refer to community resources / support groups / group activities / volunteer services Provide more intensive case management; develop an emergency action plan |

| Are you married or living together with someone in a partnership? (Married or domestic partner / Living with partner in committed relationship / In a serious or committed relationship, but not living together / Single / Separated / Divorced / Widowed) |

In a typical week, how often do you:

|

|||

In a typical week, how often do you:

|

||||

| (Never / Once a week / 2 days week / 3-5 days week / Nearly every day) | Our stakeholders also recommended including two more general questions on social isolation that are part of the Kaiser Permanente YCLS questionnaire. | |||

How often do you:

|

How often do you feel lonely or isolated from those around you? (Never / Rarely / Sometimes / Often / Always) | |||

| (Never / Once a year / 2-3 times a year / 4 or more times a year / At least once a week) | Do you have someone you could call if you needed help?* (Yes / No) | |||

| * Modified from item in PROMIS Item Bank v. 1.0 – Emotional Distress - Anger – Short Form 1 – and AARP overall loneliness item from AARP survey about loneliness in older adults; Original PROMIS item written in 1st person; loneliness added to reduce literacy level. | ||||

|

| ||||

| Stress* | Stress means a situation in which a person feels tense, restless, nervous, or unable to sleep at night because his/her mind is troubled all the time. Do you feel this kind of stress these days? (Not at all / A little bit / Somewhat / Quite a bit / Very much) | Stress is when someone feels tense, nervous, anxious, or can’t sleep at night because their mind is troubled. How stressed are you? (Not at all / A little bit / Somewhat / Quite a bit / Very much / I choose not to answer this question) | We used the PRAPARE version of the question due to difficulties obtaining copyright. | Refer to stress management programs Advise closer monitoring of BP, cholesterol |

|

| ||||

| Financial resource strain* | How hard is it for you to pay for the very basics like food, housing, heating, medical care, and medications? (Not hard at all / Somewhat hard / Very hard)69,70,67,68,66,67 | In the past year, have your or any family members you live with been unable to get any of the following when it was really needed? Check all that apply (Food / Transportation / Clothing / Child care / Utilities / Medicine or medical care / Rent or mortgage / Phone / Health insurance / Other / I choose not to answer this question) | Same as IOM, plus an additional follow-up question if they answered somewhat hard or very hard that is used in the Kaiser Permanente YCLS. | Assess food / housing insecurity; refer to relevant social and legal services. |

| What is it hard to pay for? (Food / Utilities Food, Utilities, Transportation, Medicine or Medical Care, Health Insurance, Clothing, Rent/Mortgage Payment, Child Care, Phone) | ||||

|

| ||||

| Housing | Not included in the final list of IOM-recommended domains. | What is your housing situation today? (I have housing / I do not have housing (staying with others, in a hotel, on the street, in a shelter) / I choose not to answer this question) | In the last month, have you slept outside, in a shelter, or in a place not meant for sleeping?71 (Yes / No) | |

| In the last month, have you had concerns about the conditions and quality of your housing? (Yes / No) | ||||

| In the last 12 months, how many times have you moved from one home to another? | ||||

|

| ||||

| Food | Not included in the final list of IOM-recommended domains. | Not included. | USDA Household Food Security Survey Module | |

| Which of the following describes the amount of food your household has to eat (Enough of the kinds of food we want to eat / Enough but not always the kinds of food we want / Sometimes not enough to eat / Often not enough to eat / Don’t know or Refused) | ||||

| Please tell me whether the statement was often true, sometimes true, or never true for (you/your household) in the last 12 months: | ||||

| (I/We) worried whether (my/our) food would run out before (I/we) got money to buy more. | ||||

| The food that (I/we) bought just didn’t last, and (I/we) didn’t have money to get more. | ||||

| (I/we) couldn’t afford to eat balanced meals. | ||||

|

| ||||

| Sexual orientation and gender identity | Not included in the final list of IOM-recommended domains. | Not included. | This is a required UDS data element beginning in 201672,73 and is slated for inclusion in MU-3 requirements. | |

| Sexual orientation: | ||||

| Lesbian or Gay, Straight (not lesbian or gay), Bisexual, Something else, | ||||

| I don’t know, | ||||

| Choose not to disclose, | ||||

| Other sexual orientation: comment for other | ||||

| Gender Identity: | ||||

| Female, Male, Transgender Female / Male to Female, Transgender Male - Female to Male, Other, Choose not to disclose, Other Identity: comment for other | ||||

| Preferred pronoun: he / him, she / her, they / them, ze / zim, declines to answer, unknown | ||||

IOM-recommended domain

Already routinely collected in EHR

Collecting SDH data

Stakeholder feedback, and our understanding that CHC workflows vary, indicated the need to enable SDH data collection by different care team members. As EHR security measures limit which staff can access aspects of the EHR (for example, front desk staff often cannot access the problem list), we created several options for SDH data entry:

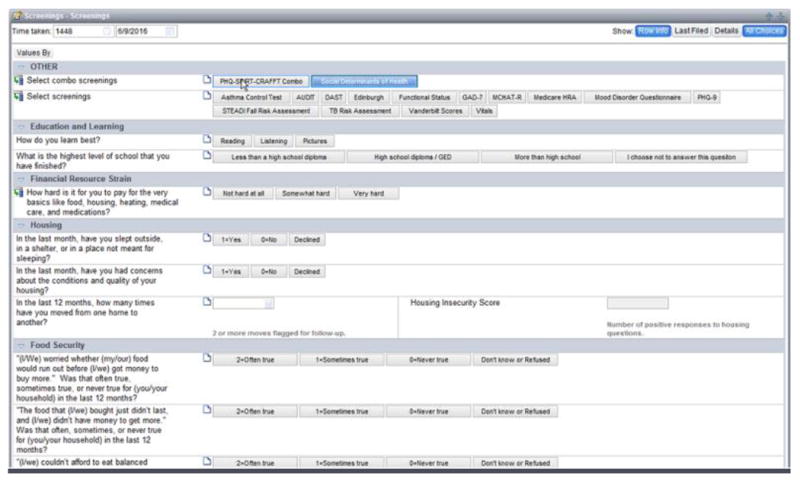

SDH ‘documentation flowsheets’ accessible to front desk staff at check-in, rooming staff, or community health workers; Figure 1.

Paper versions of the SDH questions, in English or Spanish, that can be printed out and handed to the patient to complete at check-in or rooming, were provided on OCHIN’s member wiki site. These data would have to be hand-entered by CHC staff into one of the EHR flowsheets described above.

A questionnaire on the patient portal, so patients who had an online portal account could be emailed and asked to enter the data online before a visit. The EHR’s panel management tool can identify patients with pending visits, enabling bulk secure messages to these patients. Within the portal, patients can choose navigational instructions in Spanish, but the screening questions are only available in English.

Figure 1.

SDH Flowsheet in EPIC

Considerations discussed in this process were as follows.

Making an electronic tablet available in the clinics’ waiting rooms or exam rooms, on which patients could complete their SDH screening. Two of the pilot CHCs decided it would be too complex to manage, e.g., who would be the tablet’s ‘keeper,’ where it would be stored, and how to identify which patients should use it.

Creating a setting in the exam room computer where patients could sign up for a patient portal account, then complete the SDH data through the portal immediately. In the end, this proved unfeasible because the patient must be sent the questionnaire after they sign up for the portal, necessitating an impractical multi-step workflow.

Clinicians did not want to collect SDH data themselves, preferring to transfer that responsibility to another team member. Two of the pilot sites opted to use the paper forms for data collection, then have a staff person enter the data into the EHR. This approach creates potential workflow barriers to use of the SDH tools, since until the responses are manually transferred into the chart, the data will not be available to care team members to act on during the encounter.

All options for reminding the team to conduct SDH screening were considered inadequate. Clinics said that Best Practice Advisories (BPAs, aka alerts) are largely ignored. They preferred Health Maintenance Advisories (HMAs), which are closely integrated into clinic workflows. However, HMAs must be standardized across all clinics using a shared EHR; since a universal HMA was not possible, HMAs were not a feasible option.

Similar to other screening questionnaires administered in clinical settings, clinics asked that the patient-facing data collection form not include a ‘refused to answer’ option. The staff-entered methods did include this option.

Reviewing data on patients’ SDH needs

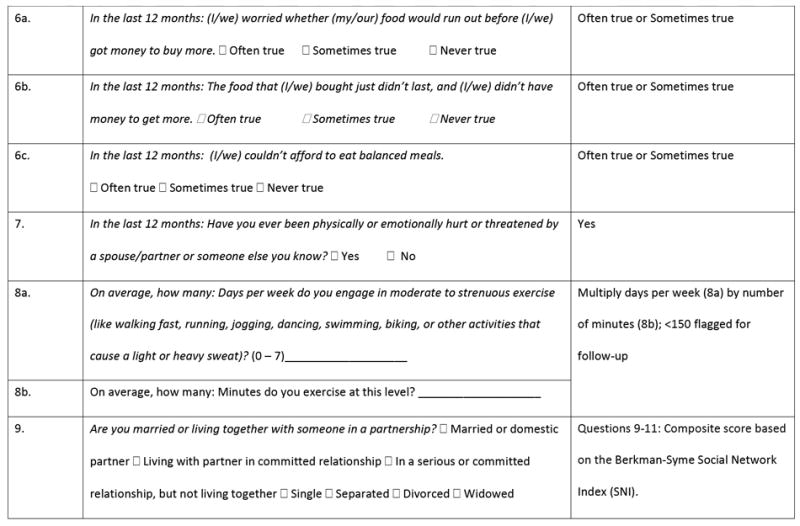

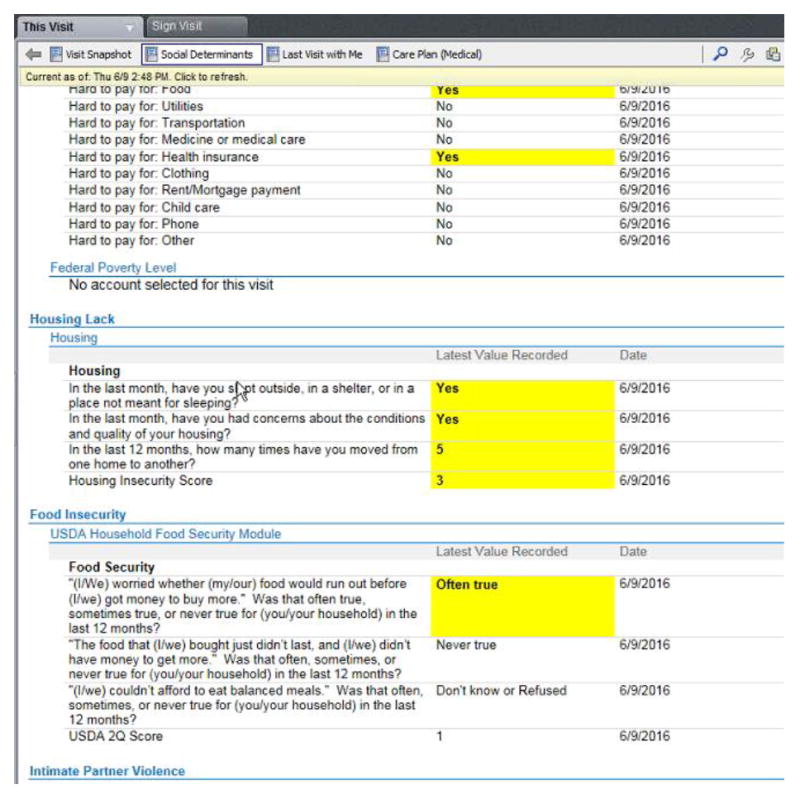

SDH data might be collected via multiple routes, and certain SDH data are already collected regularly by most CHCs. Thus, there was a need for an EHR-based summary with all of a patient’s SDH data. We created an SDH data summary that is automatically populated with data from any of the SDH data entry options, and from SDH-related data elsewhere in the EHR. The ‘SDH Summary’ also shows any SDH-related ICD-10 codes from the patient’s problem list, and any past SDH referrals if associated with an SDH-related ICD-10 code (more in “Tracking past referrals,” below). ‘Positive screens’ for SDH needs are visually highlighted. The algorithm used to identify ‘positive screens’ is in Table 4. This summary could be accessed in two ways:

An SDH Summary Tab that can be accessed in an open Office Visit or Patient Outreach encounter. The most recent SDH data for the patient is displayed, and date of data collection and referral are shown; Figure 2.

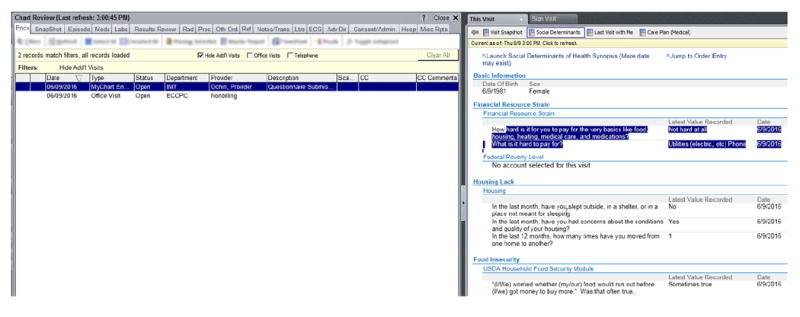

A view in the EHR’s ‘Synopsis’ window that can be accessed in a closed chart or open encounter. It displays a patient’s SDH questionnaire responses over time, in text and graphically; Figure 3.

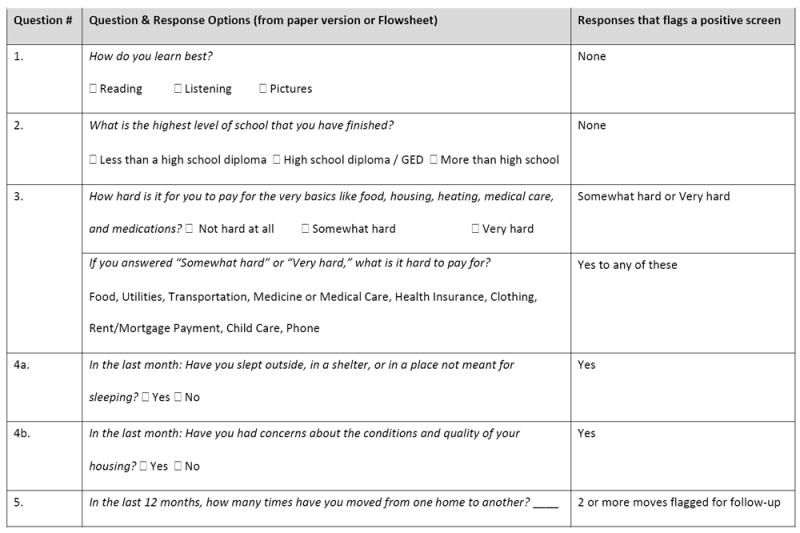

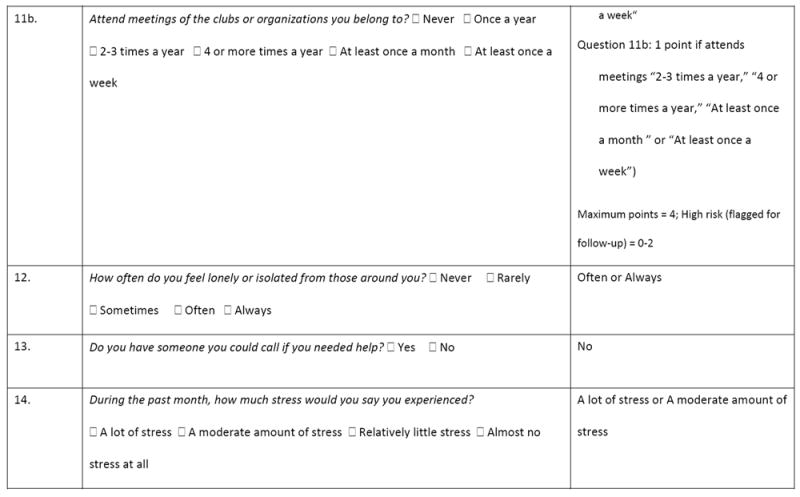

Table 4. Algorithm for identifying positive SDH screens.

|

|

|

|

SOCIAL DETERMINANTS OF HEALTH (SDH) Citations and Copyright Information June 1, 2016

Developed by OCHIN’s Clinical Operations Review Committee.

Adapted from standard education questions to align with patient population of OCHIN membership.

Slight modification of IOM-recommended financial hardship item (medications added to list of examples) Puterman E, Haritatos J, Adler NE Sidney S, Schwartz JE, Epel ESl. 2013. Indirect effect of financial strain on daily cortisol output through daily negative to positive affect in the coronary artery risk Psychoneuroendocrinology 2013; 38:12. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2013.07.016. Hall, MH., Matthews KA, Kravitz HM, Gold EB, et al. 2009. Race and financial strain are independent correlates of sleep in midlife women: The SWAN Sleep Study. Sleep 32(1):73 82. Follow-up question, “What is it hard to pay for?” was added to get more granularity and enable care team to identify needed interventions. This follow-up question was adapted from a Kaiser Permanente SDH questionnaire, with permission.

Housing questions from Health Begins Upstream Risk Screening Tool (http://www.healthbegins.org/).

US Department of Agriculture 18-item Household Food Security Survey (HFSS).

Adapted from a Kaiser Permanente SDH questionnaire, with permission.

Exercise Vital Sign – Question 1 & 2. Sallis RE. Developing health care systems to support exercise: exercise as the fifth vital sign. Br J Sports Med. 2011;45:473 4. Epic already has copyright permission.

Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III). Epic already has copyright permission to use this question. Scoring is based on the Berkman-Syme Social Network Index (SNI). Pantell M, Rehkopf D, Jutte D, Syme SL, Balmes J, Adler N. Social isolation: A predictor of mortality comparable to traditional clinical risk factors. American Journal of Public Health 2013; 103(11):2056 62. Item 10c was created as a parallel to items 10a and 10b to capture social connection via newer electronic modes that weren’t available when Berkman-Syme SNI was created. Frequency categories for 10-11 slightly modified from original. Kaiser is also using this approach in their screening tool. Epic already has copyright permission to use this question.

Modified from item in PROMIS Item Bank v. 1.0 – Emotional Distress - Anger - Short Form 1 – and AARP overall loneliness item from AARP survey about loneliness in older adults; Original PROMIS item written in 1st person; loneliness added to reduce literacy level.

Your Current Life Situation Questionnaire, Kaiser Permanente.

1998 Adult Prevention Module of the National Health Interview Survey.

Figure 2.

SDH Summary Tab

Figure 3.

SDH Summary in Synopsis

For technical reasons, it was not feasible to show problem list data or referrals in the Synopsis version of the SDH Summary. Thus, each Summary had information that the other lacked; i.e., one had past referral information but only the most recent SDH data for a given patient; the other did not have past referrals but did present patients’ SDH history, rather than just their most recent SDH data.

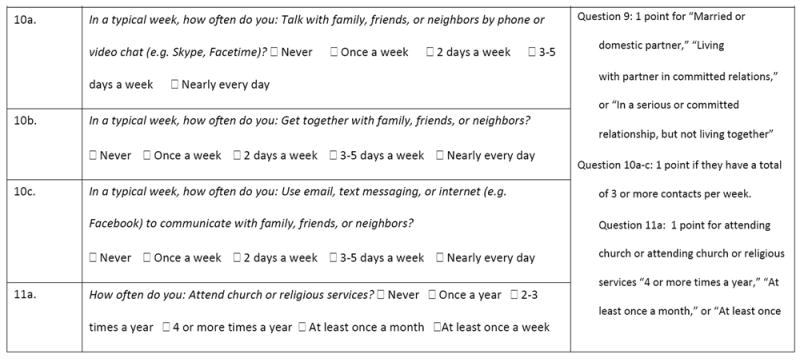

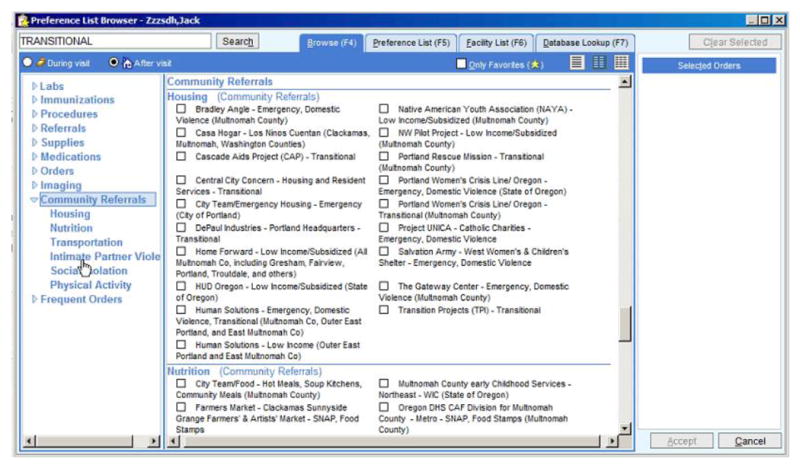

Identifying referral options

The pilot CHCs already had lists of SDH-related local resources in binders or shared drives. These were not updated systematically, but rather only when someone on the team received new information and thought to update the list. The options for how CHC teams could do this systematically, using EHR-based tools, are shown in Table 2. All of them would be accessed via a hyperlink on the ‘SDH Summary.’

The preference list option was selected for several reasons. Creating linkages to an external agency’s website was cost-prohibitive, and required organizational contracts; thus, the study clinics might learn to rely on something that would incur costs, post-study. Furthermore, some searches on these websites yielded results that were not location-specific but rather gave statewide or nationwide data. The wiki options were rejected because users would have to leave the EHR system to access them, and the study sites were concerned about how to ensure that these documents were updated. The preference lists, however, used the same EHR function that the CHCs used for other referrals; involved discrete data fields, creating trackable data; and built on the CHC teams’ local knowledge. One concern about the preference lists was that they must be kept up to date manually. However, the study CHCs currently designate a staff member to update other preference lists (e.g., for ordering laboratory tests), and the same person could be responsible for updating the SDH lists.

We helped the study clinics create ‘starter’ preference lists for the SDH areas they prioritized; Figure 4. The resources listed in each were populated with data from each clinic’s current method for keeping such information, then augmented by web searches and reviewed by staff. The lists include names and contact information of relevant services / agencies, and information such as ‘women and children only’ and hours of operation, when available.

Figure 4.

SDH Preference Lists

Ordering referrals

The SDH referrals preference lists can be used to: make internal referrals (e.g., to the community health worker); have clinic staff facilitate external referrals (e.g., calling the agency to schedule an appointment for the patient); or share agency information with the patient at the encounter or in the After Visit Summary, to follow up on their own. To make these easier to use, we created a new referral priority option of ‘no follow-up needed,’ which, if selected, informed CHC staff that they were not required to follow up on SDH referrals as they would for others. We also created a new referral type – ‘Community Referral, Non-Medical’ – so that SDH referrals would be excluded from related care quality measures. Another consideration here is that only certain care team members are authorized to make referrals of any kind; thus, support staff may need to be trained and authorized to use these tools.

Tracking past referrals

As described above, the ‘SDH Summary’ accessed through the Summary Tab (Figure 3) is automatically populated with information on past SDH-related referrals, to enable CHC teams to track them. Referrals appear in the SDH Summary if tied to a relevant ICD-10 code and / or if the SDH referral preference list was used. Presented data included date of referral, contact information about the community resource, status of the referral, and who ordered it. Care team members authorized to edit referrals can manually update the referral status.

Lessons learned

Lessons learned here may inform future efforts to build EHR tools for collecting and acting on SDH data. Since these lessons come from a pilot study conducted in three CHCs, we present them for consideration, not as a set of directions for SDH data tool development.

Considerations for which SDH questions to include

Consider striking a balance between standardized SDH data collection (i.e., aligned with the IOM-recommended measures) and the need to adapt to meet local needs, especially given that SDH data collection may become required for EHR certification and UDS reporting.

Considerations for designing SDH data collection tools

Patients may decline to answer SDH questions. Consider having SDH tools include a ‘Patient refused to answer’ option. Consider the advisability of including a ‘decline to answer’ option on patient-facing data collection tools, which might make it too easy for patients to decline.

Ensure that EHR-based SDH data tools do not require duplicate entry of SDH data collected elsewhere in workflows.

Patients with a positive SDH screening result may not want assistance in addressing the identified need. Consider creating EHR-based SDH data tools that include response options to indicate this preference, or to otherwise note that help was offered and declined.

Considerations for designing SDH data summary tools

Carefully consider which SDH data sources should populate the SDH data summary, and how to manage potentially conflicting data.

Considerations for designing SDH referral tracking tools

Monitoring the outcomes of past SDH-related referrals is challenging, often requiring outreach calls to patients. Consider whether this ability is desired.

ICD-10 codes related to SDH needs enable tracking of such needs, but may add to the problem list’s complexity. Consider creating an SDH ‘box’ within the problem list.

Considerations for maintaining up-to-date SDH referral tools

SDH referral tools rely on updated lists of local resources. Consider whether established processes for maintaining other referral lists can be applied to SDH tools. Consider partnering with organizations that maintain such lists.

Considerations for SDH-related workflows

EHR-based SDH data tools need to accommodate diverse staffing structures, resources, and workflows. Consider ensuring that the appropriate care team members are authorized to access all aspects of the tools.

To avoid overwhelming clinic staff and care teams with SDH-related work, consider limiting SDH screening to a subset of patients, and ensuring that EHR-based SDH data tools enable targeting this subset. Consider creating an alert to identify overdue patients.

To avoid overwhelming care teams, consider designing the EHR tools so that SDH-related referrals can be marked ‘no follow-up needed.’

Consider using electronic tablets58-60 to enable SDH screening at registration or rooming, with workflows for using and tracking them. Clinics will need wireless internet to enable tablets transmitting SDH data to the EHR.

To use patient portals for SDH data collection, consider developing workflows for helping patients create portal accounts at registration, then entering their SDH data through the portal on the spot. Tablets may be useful here as well.

Discussion

Standardized SDH data collection and presentation using EHR tools could facilitate diverse pathways to improved patient and population health outcomes, in CHCs and other care settings. It could provide important contextual information to care teams, facilitate referrals to local resources, inform clinical decision-making,61 enable targeted outreach efforts, and support care coordination with community resources.22,61,62 (We focused on how SDH data could be used to facilitate referring patients to local resources; research is needed on how else SDH data could inform clinical decisions). Such standardization will also provide data needed to document the SDH needs of CHC communities, inform policy and public health initiatives to improve health, and evaluate how addressing SDH risks affects health.

To attain these potential benefits, healthcare organizations need guidance on how to facilitate systematic SDH screening in primary care settings using EHR-based tools.63-65 Little such guidance currently exists; we know of no previous published reports on processes used to develop EHR-based SDH data collection, summary, and referral tools. This paper is meant to present an example of a process through which stakeholder input informed the development of a preliminary set of SDH-focused EHR tools. While the results and lessons learned from our process may be useful to other organizations undertaking such efforts, they are preliminary and based on opinions from a relatively small group of stakeholders, health informaticists, and health services researchers. Extensive research is needed to empirically test the generalizability of these lessons.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate the contributions of Edward Mossman, MPH (OCHIN, Inc.) Marla Dearing (OCHIN, Inc.) and Katie Dambrun, MPH towards this manuscript and overall ASSESS & DO planning efforts. The authors also greatly appreciate the contributions of staff at our pilot sites, Jennifer Hale, RN (Cowlitz Family Health Center), James Stoltz, RN (Cowlitz Family Health Center), and Maria Zambrano (La Clinica Health Center) who provided feedback on clinic workflows and implementation efforts. We would also like to thank collaborators, Ranu Pandey, MHA (Kaiser Permanente Care Management Institute) and Matthew C. Stiefel, MS, MPA (Kaiser Permanente Care Management Institute) and OCHIN’s Clinical Operations Review Committee (CORC) for their input on development of the SDH data collection tool.

Funding Statement: This publication was supported by grant from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK), R18DK105463.

Footnotes

Conflicting and competing Interests: The authors of this manuscript have nothing to disclose and no conflicts of interest. The funder had no role in the design and conduct of the study, in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data, and in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. What are social determinants of health? [10-3-0016];2016 Feb 5; http://www.who.int/social_determinants/sdh_definition/en/

- 2.US Department of Health & Human Services (DHHS) Healthy People 2010. 2. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR. Unequal treatment: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. In: Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, editors. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Understanding and Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stringhini S, Sabia S, Shipley M, et al. Association of socioeconomic position with health behaviors and mortality. JAMA. 2010;303:1159–1166. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kann L, Olsen EO, McManus T, et al. Sexual identity, sex of sexual contacts, and health-risk behaviors among students in grades 9-12--youth risk behavior surveillance, selected sites, United States, 2001-2009. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2011;60:1–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tarlov AR. Public Policy Frameworks for Improving Population Health. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;896:281–293. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb08123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marmot MG, Shipley MJ. Do socioeconomic differences in mortality persist after retirement? 25 year follow up of civil servants from the first Whitehall study. BMJ. 1996;313:1177–1180. doi: 10.1136/bmj.313.7066.1177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frieden TR. A framework for public health action: the health impact pyramid. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:590–595. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.185652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fenton . Health Care’s Blind Side: The Overlooked Connection between Social Needs and Good Health. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Woolf SH, Johnson RE, Phillips RL, Jr, Philipsen M. Giving everyone the health of the educated: an examination of whether social change would save more lives than medical advances. Am J Public Health. 2007;97:679–683. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.084848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chandola T, Ferrie J, Sacker A, Marmot M. Social inequalities in self reported health in early old age: follow-up of prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2007;334:990. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39167.439792.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Galobardes B, Davey SG, Jeffreys M, McCarron P. Childhood socioeconomic circumstances predict specific causes of death in adulthood: the Glasgow student cohort study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006;60:527–529. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.044727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hammig O, Bauer GF. The social gradient in work and health: a cross-sectional study exploring the relationship between working conditions and health inequalities. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:1170. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-1170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krieger N, Kosheleva A, Waterman PD, Chen JT, Beckfield J, Kiang MV. 50-year trends in US socioeconomic inequalities in health: US-born Black and White Americans, 1959-2008. Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43:1294–1313. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyu047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lahiri S, Moure-Eraso R, Flum M, Tilly C, Karasek R, Massawe E. Employment conditions as social determinants of health. Part I: the external domain. New Solut. 2006;16:267–288. doi: 10.2190/U6U0-355M-3K77-P486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moure-Eraso R, Flum M, Lahiri S, Tilly C, Massawe E. A review of employment conditions as social determinants of health part II: the workplace. New Solut. 2006;16:429–448. doi: 10.2190/R8Q2-41L5-H4W5-7838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lahelma E, Laaksonen M, Aittomaki A. Occupational class inequalities in health across employment sectors: the contribution of working conditions. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2009;82:185–190. doi: 10.1007/s00420-008-0320-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ferrie JE, Shipley MJ, Davey SG, Stansfeld SA, Marmot MG. Change in health inequalities among British civil servants: the Whitehall II study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2002;56:922–926. doi: 10.1136/jech.56.12.922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Lenthe FJ, Borrell LN, Costa G, et al. Neighbourhood unemployment and all cause mortality: a comparison of six countries. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2005;59:231–237. doi: 10.1136/jech.2004.022574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barnett E, Casper M. A definition of “social environment”. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:465. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.3.465a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kawachi I, Berkman LF. Neighborhoods and health. Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Institute of Medicine. Recommended social and behavioral domains and measures for electronic health records. National Academies of Science; 2014. [2-5-0216]. http://www.iom.edu/Activities/PublicHealth/SocialDeterminantsEHR.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Adler NE, Stead WW. Patients in context--EHR capture of social and behavioral determinants of health. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:698–701. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1413945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology. [10-2-2016];The Federal Health IT Strategic Plan 2015-2020. 2016 https://www.healthit.gov/sites/default/files/9-5-federalhealthitstratplanfinal_0.pdf.

- 25.Committee on the Recommended Social and Behavioral Domains and Measures for Electronic Health Records - Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice. Capturing Social and Behavioral Domains and Measures in Electronic Health Records PHASE 2. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CMS Timeline of Important MU Dates. [9-9-2016];2016 http://www.cdc.gov/ehrmeaningfuluse/timeline.html.

- 27.Tagalicod R, Reider J. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; 2016. [9-12-2016]. Progress on Adoption of Electronic Health Records. https://www.cms.gov/eHealth/ListServ_Stage3Implementation.html. [Google Scholar]

- 28.HealthIT.gov. HITPC Meaningful Use Stage 3 Final Recommendations. 2014 Apr 1; https://www.healthit.gov/facas/sites/faca/files/HITPC_MUWG_Stage3_Recs_2014-04-01.pdf.

- 29.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. MACRA: Delivery System Reform, Medicare Payment Reform. [9-9-2016];2016 https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/Value-Based-Programs/MACRA-MIPS-and-APMs/MACRA-MIPS-and-APMs.html.

- 30.Bailey SR, O’Malley JP, Gold R, Heintzman J, Marino M, DeVoe JE. Receipt of diabetes preventive services differs by insurance status at visit. Am J Prev Med. 2015;48:229–233. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.08.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gold R, DeVoe JE, McIntire PJ, Puro JE, Chauvie SL, Shah AR. Receipt of diabetes preventive care among safety net patients associated with differing levels of insurance coverage. J Am Board Fam Med. 2012;25:42–49. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2012.01.110142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gold R, DeVoe J, Shah A, Chauvie S. Insurance continuity and receipt of diabetes preventive care in a network of federally qualified health centers. Med Care. 2009;47:431–439. doi: 10.1097/mlr.0b013e318190ccac. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hsu CC, Lee CH, Wahlqvist ML, et al. Poverty increases type 2 diabetes incidence and inequality of care despite universal health coverage. Diabetes Care. 2012;35:2286–2292. doi: 10.2337/dc11-2052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lipton RB, Liao Y, Cao G, Cooper RS, McGee D. Determinants of incident non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus among blacks and whites in a national sample. The NHANES I Epidemiologic Follow-up Study. Am J Epidemiol. 1993;138:826–839. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lysy Z, Booth GL, Shah BR, Austin PC, Luo J, Lipscombe LL. The impact of income on the incidence of diabetes: a population-based study. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2013;99:372–379. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2012.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jones-Smith JC, Karter AJ, Warton EM, et al. Obesity and the food environment: income and ethnicity differences among people with diabetes: the Diabetes Study of Northern California (DISTANCE) Diabetes Care. 2013;36:2697–2705. doi: 10.2337/dc12-2190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Muennig P, Franks P, Jia H, Lubetkin E, Gold MR. The income-associated burden of disease in the United States. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61:2018–2026. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li V, McBurnie MA, Simon M, et al. Impact of Social Determinants of Health on Patients with Complex Diabetes Who Are Served by National Safety-Net Health Centers. J Am Board Fam Med. 2016;29:356–370. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2016.03.150226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Frieden TR. Forward: CDC Health Disparities and Inequalities Report - United States, 2011. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2011;60(Suppl):1–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.The Menges Group. Positively Impacting Social Determinants of Health: How Safety Net Health Plans Lead the Way. 2014 http://www.communityplans.net/Portals/0/Fact%20Sheets/ACAP_Plans_and_Social_Determinants_of_Health.pdf.

- 41.Institute for Alternative Futures. Community Health Centers Leveraging the Social Determinants of Health. Alexandria, VA: 2012. [5-5-2014]. http://www.altfutures.org/pubs/leveragingSDH/IAF-CHCsLeveragingSDH.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bachrach D, Pfister H, Wallis K, Lipson M. Addressing Patients’ Social Needs: An Emerging Business Case for Provider Investment. The Commonwealth Fund, The Skoll Foundation, and the Pershing Square Foundation; [5-29-2014]. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Garg A, Toy S, Tripodis Y, Silverstein M, Freeman E. Addressing Social Determinants of Health at Well Child Care Visits: A Cluster RCT. Pediatrics. 2015;135:e296–e304. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-2888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chung EK, Siegel BS, Garg A, et al. Screening for Social Determinants of Health Among Children and Families Living in Poverty: A Guide for Clinicians. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2016;46:135–153. doi: 10.1016/j.cppeds.2016.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Institute of Medicine. Capturing Social and Behavioral Domains in Electronic Health Records: Phase 1. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Karsh BT. Beyond usability: designing effective technology implementation systems to promote patient safety. Qual Saf Health Care. 2004;13:388–394. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2004.010322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Aoyama M. Beyond software factories: concurrent-development process and an evolution of software process technology in Japan. Information and Software Technology. 1996;38:133–143. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Miller WL, Crabtree BF, McDaniel R, Stange KC. Understanding change in primary care practice using complexity theory. J Fam Pract. 1998;46:369–376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rauterberg M, Strohm O. Work organization and software development. Annual Review in Automatic Programming. 1992;16:128. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rauterberg M, Strohm O. Benefits of user-oriented software development based on an iterative cyclic process model for simultaneous engineering. International Journal of Industrial Ergonomics. 1995;16:391–410. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Boehm B, Egyed A. Optimizing software product integrity through life-cycle process integration. Computer Standards and Interfaces. 1999;21:63–75. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cooper RG. Overhauling the New Product Process. Journal of Consumer Research. 1996;25:482. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gurses AP, Marsteller JA, Ozok AA, Xiao Y, Owens S, Pronovost PJ. Using an interdisciplinary approach to identify factors that affect clinicians’ compliance with evidence-based guidelines. Crit Care Med. 2010;38:S282–S291. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181e69e02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pronovost PJ, Goeschel CA, Marsteller JA, Sexton JB, Pham JC, Berenholtz SM. Framework for patient safety research and improvement. Circulation. 2009;119:330–337. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.729848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Davis FD, Bagozzi RP, Warshaw PR. User acceptance of computer technology: a comparison of two theoretical models. Management Science. 1989;35:982–1003. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Davis FD. User acceptance of information technology: system characteristics, user perceptions and behavioral impacts. Int J Man-Machine Stud. 1993;38:475–487. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Venkatesh V. Determinants of perceived ease of use: Integrating control, intrinsic motivation, and emotion into the technology acceptance model. Information systems research. 2000;11:342–365. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Harris SK, Knight JR. Putting the Screen in Screening: Technology-Based Alcohol Screening and Brief Interventions in Medical Settings. Alcohol Res. 2014;36:63–79. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Beadnall HN, Kuppanda KE, O’Connell A, Hardy TA, Reddel SW, Barnett MH. Tablet-based screening improves continence management in multiple sclerosis. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2015;2:679–687. doi: 10.1002/acn3.205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Anand V, McKee S, Dugan TM, Downs SM. Leveraging electronic tablets for general pediatric care: a pilot study. Appl Clin Inform. 2015;6:1–15. doi: 10.4338/ACI-2014-09-RA-0071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gottlieb LM, Tirozzi KJ, Manchanda R, Burns AR, Sandel MT. Moving electronic medical records upstream: Incorporating social determinants of health. Am J Prev Med. 2015;48 doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gottlieb L, Sandel M, Adler NE. Collecting and applying data on social determinants of health in health care settings. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:1017–1020. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Garg A, Butz AM, Dworkin PH, Lewis RA, Thompson RE, Serwint JR. Improving the management of family psychosocial problems at low-income children’s well-child care visits: the WE CARE Project. Pediatrics. 2007;120:547–558. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-0398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Garg A, Toy S, Tripodis Y, Silverstein M, Freeman E. Addressing Social Determinants of Health at Well Child Care Visits: A Cluster RCT. Pediatrics. 2015;135:e296–e304. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-2888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gottlieb L, Hessler D, Long D, Amaya A, Adler N. A randomized trial on screening for social determinants of health: the iScreen study. Pediatrics. 2014;134:e1611–e1618. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-1439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.US Preventive Services Task Force. Grade Definitions. [10-29-2016];2016 https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Name/grade-definitions.

- 67.Sherin KM, Sinacore JM, Li XQ, Zitter RE, Shakil A. HITS: a short domestic violence screening tool for use in a family practice setting. Fam Med. 1998;30:508–512. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bardwell J, Sherin K, Sinacore J, Zitter R, Shakil A. Journal of Advocate Health Care. 1999;1:5–7. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Puterman E, Haritatos J, Adler NE, Sidney S, Schwartz JE, Epel ES. Indirect effect of financial strain on daily cortisol output through daily negative to positive affect index in the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults Study. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2013;38:2883–2889. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2013.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hall MH, Matthews KA, Kravitz HM, et al. Race and financial strain are independent correlates of sleep in midlife women: the SWAN sleep study. Sleep. 2009;32:73–82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Manchanda R, Gottlieb L. Upstream Risks Screening Tool and Guide V2.6. Los Angeles, CA: HealthBegins; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bureau of Primary Healthcare. [10-20-2016];2016 Uniform Data System (UDS) Reporting Changes. 2016 http://bphc.hrsa.gov/datareporting/reporting/2016udsreportingchanges.pdf.

- 73.Caiazza T. STATEMENT: New HHS Rules Require Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity Data Collection in Electronic Health Records Program. [10-20-2016];2015 Oct 7; https://www.americanprogress.org/press/statement/2015/10/07/122884/statement-new-hhs-rules-require-sexual-orientation-and-gender-identity-data-collection-in-electronic-health-records-program/