Introduction

A disease is said to be an emerging disease that is a completely new infection (Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS), Bourbon virus, discovered in Kansas) or has recently increased in incidence or impact and severity, affected newer geographical locations, or is an existing disease that has recently developed new clinical pattern, or developed resistance to existing therapy.[1] A subset of emerging diseases that was once endemic before developing a quiescence state or were controlled or even eradicated is called disease (chikungunya infection in India). The term “recent” has been defined as 2–3 decades. The term “emerging” was first given by Krause and Lederberg in 1981.[1] Thus, Lyme disease, Tuberculosis (TB), West Nile virus, Nipah virus, AIDS, and antibiotic-resistant microbial infections are all by definition, emerging infections. It is estimated that fatality rate of 17 million deaths per year worldwide is caused by rapidly spreading highly infectious diseases.

As per published reports, 47% of the total 2.1 million deaths among children below 5 years of age in 2010 were due to infectious diseases such as pneumonia and acute diarrhea.[2]

In this issue of the journal, many aspects of the important emerging infections with special focus on India and other South East Asian countries have been discussed. In the following section of this editorial, many other important issues will be discussed.

Importance of South East Asia

One of the most severe epidemics in recent history called severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) emerged from Guangdong Province of China between November 2002 and early January 2003. By the time WHO declared it a global alert on March 12, 2003, it spread to other parts of China and many other countries.[3] This event indicated the vulnerability of us to the emerging infections and weakness of our existing health-care system to protect the mankind.

South East Asia is considered a vital zone globally with regard to the risk of outbreak of the emerging infectious disease (EID). This area is inhabited by more than 30% of the global population. Despite impressive improvements in health and health-care infrastructure, infectious diseases are still the major cause of death in this region. For the presence of various factors such as poverty, overpopulate, and inadequate preventive health system, South East Asia is prone to develop many of the emerging infections.[4,5]

What Precipitates Emerging Infections?

A number of human factors play a role in the emergence of infections such as increasing population, poverty, malnutrition, international travels, mass migration of people due to war, natural calamities or economic reasons, social practices, sexual habits, global patterns in metabolic and immunosuppressive diseases (diabetes, HIV), bioterrorism, urbanization, deforestation, human encroachment on wildlife habitats, change in cultivation process, mass food processing, mixed farming, occupational exposure, recreational activities, drug resistance, and antibiotic abuse.[6] Genetic alteration in the organism is another important factor that can cause emergence of a disease. In many occasions, weakened public health infrastructure fails to control such emergence of infection.

Resistance to the drugs is one important factor in the emergence of infections. It is an irony that both overuse and inadequate use can lead to drug resistance to the anti-infectives and these two different situations are seen in developed and underdeveloped countries, respectively.[7] In developed countries, these drugs are often overused. In underdeveloped countries, frequent availability of counterfeit medicines, premature stoppage of drugs due to cost, or other factors have the same effect in increasing the drug resistance. Over-the-counter availability and rampant self-medication greatly enhance the chance of resistance. A series of 46 confidential reports during 1999–2000 evaluating many such suspected counterfeit drugs from 20 countries confirmed that 32% of such drugs had either no active molecules or grossly inadequate quantity, extraneous ingredients, or impurities.[7] Prohibitive cost often makes the much less effective drugs be used as the first choice despite availability of the first-line drug. To complicate the situation, drug resistance once developed increases the cost of therapy and risk of adverse effects exponentially and reduces the success rate. This is exactly what happened in case of multidrug-resistant TB treatment. Artemisinin-resistant malaria was found in Combodia in 2009.[8] Drug resistance is now frequent in gonorrhea, Streptococcus pneumonia, HIV, and many other hospital infections. The latest addition to this list is superficial dermatophytes that are showing high degree of resistance to most of the available oral antifungal drugs such as fluconazole. Although the resistance at the pharmacological level is being investigated, clinical experience in the field level is alarming in many South East Asian countries including India.

Many other factors need to be considered though hard evidence in its favor is yet to be available. These are indiscriminate use of anti-infectives in animal husbandry, agriculture, and aquaculture where these drugs that are also used in human, are used for treatment or in large-scale as preventive measure.[7] These could lead to the development of cross resistance. The magnitude of this problem is yet to be documented or proved.

Some Important Emerging Infections

It is interesting to know that the about 60% of all human infectious diseases and about 75% of all human emerging infectious have originated from animals (zoonotic diseases) and no less than two-thirds of these have originated in the wildlife.[9,10] Urbanization has resulted in destruction of natural habitats of the animals leading to more close interaction of human with the animals and also the vectors. Human development has witnessed simultaneous and progressive alteration in the climate and ecosystem. These all have significantly increased the chance of transmission of animal diseases to the humans who have minimum or no inherent immunity to these animal diseases. Development of more severe, as well as drug-resistant mutant varieties of the organisms also play additive role in the emergence of the infections.

Many of the emerging infections have posed significant threat to the mankind owing to their extensive extent of involvement globally, high severity and consequently extraordinarily high degree of morbidity and mortality and huge financial loss. SARS, one of the earliest severe emerging infections in the recent time, was originated in Guangdong province of China in 2003 and then spread to many other countries of Asia, Americas, and Europe.

A more severe disease called H1N1 (bird flu/avian influenza) soon followed. It originated in Mexico and spread very fast to many countries including India. Total global death crossed 17000 with 12000 only in the USA where it has been declared as national emergency.[11]

Many large scale outbreaks of infections took place subsequently in this part of the world. There were emergence and reemergence of influenza caused by the highly pathogenic avian influenza virus (H5N1) in 2004,[12] two novel bat-associated reoviruses infection (Melaka virus, Kampar virus) in Malaysia in 2006,[13,14] and a novel tick-borne bunyavirus associated with fever and thrombocytopenia in China in 2009.[15] These all indicated a large pool of potential zoonotic pathogens in East and South East Asia.[16] One highly virulent coronavirus-associated respiratory disease caused large number of mortality mostly in Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) in 2014. This was named as MERS Coronavirus. Melioidosis has been reported to be on rise in India.[17]

Arboviral Disease

Arboviral disease (arthropod-borne viral disease) is one of the major emerging or re-emerging infections in the Indian subcontinent. These are mostly RNA virus. More than 130 arboviruses are found to cause human disease. Many fatal epidemics have been seen with arboviral disease. The examples are dengue, chikungunya, Japanese encephalitis, Kyasanur forest disease, and Crimean–Congo hemorrhagic fever. Arboviral diseases of public health importance belong to Flavivirus, Alphavirus, and bunyavirus.[18]

Reemergence of chikungunya fever (chikungunya virus) has occurred since 2006 in many parts of India. Unlike previous outbreaks during 1963 and 1973 when infection was caused by Asian strains, East African genotypes were detected this time.[19] This causes significant bone pain and other morbidity, but mortality is rare.

Dengue virus (family Flaviviridae, genus Flavivirus) is a global threat to mankind. This is transmitted by the day-biting mosquito, Aedes aegypti. This is endemic to hyperendemic in South East Asia. About 2.5 billion people living in urban areas of tropical and subtropical regions are at risk of dengue infection.[20]

This is characterized by influenza-like self-limiting illness but can also have features of more severe diseases such as dengue hemorrhagic fever (DHF) and dengue shock syndrome (DSS). Mortality may be high (about 20%) in complicated and neglected cases.

Dengue infection has increased in an alarming rate in India. The first virologically confirmed dengue case was reported in Kolkata in 1963. This has been reported from major parts of India and all 4 serotypes (DENV 1-4) have been involved, and cooccurrence of multiple serotypes is not uncommon.

In the Indian perspective, many outbreaks of the emerging and reemerging diseases have been noticed in last few decades. Many of them are zoonotic in nature. There was an outbreak of cholera (Vibrio cholerae O139) in southern peninsular India in 1992.[21] It then spread along the coast line of Bay of Bengal.

Zika virus (family Flaviviridae, genus Flavivirus), closely related to Dengue and other Flavivirus, has caused an ongoing epidemic in Brazil and many other countries in South America, Central America, Mexico, and the Caribbean since 2015. From there, it reached Singapore and Malaysia.[22]

It was first isolated in 1947 in the Zika Forest of Uganda in a rhesus macaque monkey. For many years, it was limited within a narrow equatorial belt from Africa to Asia like Central African Republic, Egypt, Gabon, Sierra Leone, Tanzania, and Uganda, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Thailand, Vietnam, and Pakistan. Its progress toward eastern world was noticed since 2007 and then crossed Pacific Ocean to reach the America. Neutralizing antibody has been detected among Indians long back indicating protective immunity.[23]

It is transmitted by the Aedes mosquitoes. Death is known to be rare. WHO has published a case definition for Zika virus infection.[24] There is no vaccine so far and the management is dependent upon only symptomatic treatment.

Other Important Emerging Viral Infections

Among the other important emerging infections, some fatal infections deserve mention. Chandipura virus (detected first in Chandipura, Nagpur, India in 1965) that was transmitted by sand flies emerged in Andhra Pradesh in 2003. Nipah virus, a food-borne disease, that was transmitted from eating dates contaminated with urine or saliva of infected bats and then person-to-person transmission occurred originated in Malaysia in 1999 then reached Bangladesh[25] and different parts of India including Siliguri, West Bengal since 2001.[26]

Many outbreaks remain etiologically diagnosed. A serious condition emerged in India since last few years when highly fatal encephalitis of unknown etiology affected large population in many states such as Uttar Pradesh, followed by Bihar, Assam, and West Bengal.[27] Reported case fatality rate was 41.13%.[28] This was named as acute encephalitis syndrome and was manifested with fever and seizures and other features of encephalitis, especially among children below 10 years. Japanese encephalitis virus detected in about 15% but actual etiology could be different.

Hand, foot, and mouth disease is one of the fastest growing emerging infections in India and many other South East Asian countries. This is caused by many species of the Enterovirus genus in the family Picornaviridae. Enterovirus 71 (EV-71) and coxsackievirus A16 (CV-A16) are two most common viruses, but other EV types such as CV-A4–CVA7, CV-A9-10, CV-B1-3, CV-B5, E-4, and E-19 have also been implicated.[29,30] In this issue, a report on virological analysis for three successive years among cases with HFMD in West Bengal has been published and authors reported the presence of EV71, CA6, as well as CA16 indicating simultaneous presence of multiple types. HFMD has caused an ongoing epidemic in China with large number of death. India has not yet seen any major incidence of such complications. Virological analysis of enterovirus is difficult and mostly unavailable commercially. Simple protective measures are often helpful. Vaccination research is yet not successful.

Rickettsial Diseases

Rickettsial diseases are one of the most important emerging as well as reemerging diseases in India and other South East Asian countries and are reported since 1930. Rickettsial infections are caused by a different obligate intracellular, Gram-negative bacteria (Rickettsia, Orientia, Ehrlichia, Neorickettsia, Neoehrlichia, and Anaplasma) and are mostly present in rodents and is transmitted by vectors such as mite, ticks, lice, and fleas. Humans are accidentally affected.

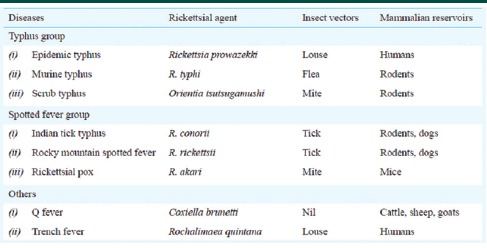

Diseases caused by rickettsia are primarily divided into two clinical groups, called the typhus group and spotted fever group [Table 1].[31]

Table 1.

Classification of rickettsial diseases[31]

Scrub typhus is the most common rickettsial disease in India. Other rickettsial diseases seen in India are murine flea-borne typhus, Indian tick typhus, and Q fever. Scrub typhus is reported from Kumaon region, Assam, Jammu and Kashmir, Himachal Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Bihar, West Bengal (Darjeeling), Meghalaya, Rajasthan, Maharashtra, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, and Kerala. Many cases of scrub typhus go unnoticed and undiagnosed; the magnitude may even reach 50% of all cases of undifferentiated fever presenting to hospital for some regions.

In this issue, scrub typhus has been reported from the southern districts of West Bengal. Rickettsial diseases may have poor prognosis unless treated early. In a recently published guideline by ICMR, it has been mentioned that doxycycline or azithromycin should be started as soon as clinical diagnosis is made without waiting for laboratory confirmation. Management guideline for the children has also been published by Indian Academy of Pediatrics.[32]

Bacterial Infections

Emergence of antibiotic bacterial infection has been posing a great threat. The prevalence of community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus has been showing a steady increase. These are primarily causing skin and soft tissue infections.[33,34]

Vancomycin-intermediate S. aureus and virulent toxin-producing strains of Group A beta-hemolytic streptococci that cause streptococcal toxic shock syndrome are gradually showing increased prevalence.[35]

The prevalence of Acinetobacter baumannii, an important nosocomial pathogen, that can cause pneumonia, bacteremia, meningitis, urinary tract infections, and skin and soft tissue infections as well as multidrug-resistant strains is increasingly being reported.[36]

It is interesting to find a gradual shift from Mycobacterium scrofulaceum to Mycobacterium avium causing cervical lymphadenitis in children. M. avium is more resistant to therapy, and this shift might have been caused by increased water chlorination of the swimming pools leading to selective survival of more resistant strains.[37]

Current Scenario, Prevention and Our Role

Emerging infections have tremendous impact on the psychosocial and economic aspect of mankind. This is a major threat to life and does not discriminate sex, age, social, economic, or political background. Both developed and underdeveloped countries are at risk. Despite the significant advancement in health-care system, the suddenness and unpredictable nature of the events leave limited scope for an immediately effective strategy that might be useful to abort an imminent attack. Thus, a well-planned health-care system should be built for halting the spread and to minimize the damage incurred by the emerging infection.

Each and every factor that increases the risk of infection spread should be addressed and executed. Population control and financial upliftment of the society are two most important steps. However, both of these need a long-term unbiased and apolitical plan.

Primary prevention (removal of risk factor through vector eradication, immunizations, provision of uncontaminated drinking water), secondary prevention (surveillance), early therapeutic interventions, and infrastructure development for proper distribution of such care to the community are the basis of perfect health-care strategy to prevent the emerging infections.

Extensive immunization is one of the most effective ways to prevent the spread of many emerging infections. Vaccine has been made and is being marketed for Japanese encephalitis. Vaccination strategies have been modified for other diseases such as measles. However, there remained many hurdles, and vaccination for most other diseases is still far from a targeted level.

Surveillance plays a vital role in disease prevention. This is meant for early detection and stopping further spread. This allows characterization of the infections, modification of vaccine strategies, and subsequent intense immunization campaign. Unfortunately, this has never been less than adequately addressed in South East Asia. Much of the surveillance in this region has been centered in a few well-established laboratories.

Funding in health care especially the preventive health care is often neglected. Policymakers frequently choose to avoid investment in preventive health care as it is less rewarding in the short term.

Poor research activity which is the direct result of research funding is possibly the greatest threat to scientific development. Research interest should be streamlined and research priorities need to be scientifically monitored. Lack of coordination between clinical and basic research scientists should be addressed to achieve target-oriented outcome.

Early suspicion and rapid confirmation of diagnosis is vital in preventing an emerging infection. Availability of simple, easy to perform, and affordable tests are a basic necessity that the government should ensure. Availability of the anti-infective drugs should be restricted over the counter and should be dispensed exclusively on prescription. Price control is another major step that administrative authorities should look into. Quality control of the available drugs is frequently neglected while price is being cut down. Monitoring this is equally vital.

Conclusion

The current symposium of the journal has focused discussion on “Emerging Infections” and has addressed various vital aspects of the major emerging and reemerging diseases with particular emphasis on India and other South East Asian countries. It is expected that readers will enjoy reading this, and in a larger perspective, it will help to fight many known and unknown emerging infections in a much better way.

References

- 1.Daszak P, Cunningham AA. Anthropogenic change, biodiversity loss, and a new agenda for emerging diseases. J Parasitol Suppl. 2003;89:37–41. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu L, Johnson HL, Cousens S, Perin J, Scott S, Lawn JE, et al. Global, regional, and national causes of child mortality: An updated systematic analysis for 2010 with time trends since 2000. Lancet. 2012;379:2151–61. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60560-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhong NS, Zheng BJ, Li YM, Poon, Xie ZH, Chan KH, et al. Epidemiology and cause of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in Guangdong, People's Republic of China, in February, 2003. Lancet. 2003;362:1353–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14630-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.WHO Global Burden Disease 2004 Update. [Last accessed on 2017 Aug 13]. Available from: http://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/GBD_report_2004update_full.pdf .

- 5.Morens DM, Folkers GK, Fauci AS. The challenge of emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases. Nature. 2004;430:242–9. doi: 10.1038/nature02759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mani RS, Ravi V, Desai A, Madhusudana SN. Emerging viral infections in India. Proc Natl Acad Sci India B Biol Sci. 2012;82:5–21. doi: 10.1007/s40011-011-0001-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heymann DL. Resistance to anti-infective drugs and the threat to public health. Cell. 2006;124:671–5. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dondorp AM, Nosten F, Yi P, Das D, Phyo AP, Tarning J, et al. Artemisinin resistance in Plasmodium falciparum malaria. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:455–67. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization, South-East Asia Region, Western Pacific Region. Asia Pacific Strategy for Emerging Diseases: 2010. New Delhi, Manila: WHO-SEARO, WHO-WPRO; 2011. [Last accessed on 2017 Aug 13]. Available from: http://www.wpro.who.int/emerging_diseases/documents/docs/ASPED_2010.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fauci AS. Infectious diseases: Considerations for the 21st century. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32:675–85. doi: 10.1086/319235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Health Organization. Situation Updates – Pandemic 7. (H1N1) 2009. [Last accessed on 2012 Sep 06]. Available from: http://www.who.int/csr/disease/swineflu/updates/en/

- 12.Tran TH, Nguyen TL, Nguyen TD, Luong TS, Pham PM, Nguyen VV, et al. Avian influenza A (H5N1) in 10 patients in Vietnam. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1179–88. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chua KB, Crameri G, Hyatt A, Yu M, Tompang MR, Rosli J, et al. A previously unknown reovirus of bat origin is associated with an acute respiratory disease in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:11424–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701372104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chua KB, Voon K, Crameri G, Tan HS, Rosli J, McEachern JA, et al. Identification and characterization of a new orthoreovirus from patients with acute respiratory infections. PLoS One. 2008;3:e3803. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yu XJ, Liang MF, Zhang SY, Liu Y, Li JD, Sun YL, et al. Fever with thrombocytopenia associated with a novel bunyavirus in China. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1523–32. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1010095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Horby PW, Pfeiffer D, Oshitani H. Prospects for emerging infections in East and Southeast Asia 10 years after severe acute respiratory syndrome. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013;19:853–60. doi: 10.3201/eid1906.121783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gopalakrishnan R, Sureshkumar D, Thirunarayan MA, Ramasubramanian V. Melioidosis: An emerging infection in India. J Assoc Physicians India. 2013;61:612–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dash AP, Bhatia R, Sunyoto T, Mourya DT. Emerging and re-emerging arboviral diseases in Southeast Asia. J Vector Borne Dis. 2013;50:77–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Vector Borne Disease Control Programme, 47. Chikungunya. Government of India; update. [Last accessed on 2017 Aug 13]. Available from: http://www.nvbdcp.gov.in/Doc/Facts%20about%20Chikungunya17806.pdf .

- 20.Halstead SB. Dengue. Lancet. 2007;370:1644–52. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61687-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ramamurthy T, Yamasaki S, Takeda Y, Nair GB. Vibrio cholerae O139 Bengal: Odyssey of a fortuitous variant. Microbes Infect. 2003;5:329–44. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(03)00035-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Singapore Zika Study Group. Outbreak of Zika virus infection in Singapore: An epidemiological, entomological, virological, and clinical analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2017;17:813–21. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30249-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smithburn KC, Kerr JA, Gatne PB. Neutralizing antibodies against certain viruses in the sera of residents of India. J Immunol. 1954;72:248–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zika Virus Disease. Interim Case Definitions. WHO/ZIKV/SUR/16.1. World Health Organization. 2016. Feb 12, [Last accessed on 2017 Aug 13]. Available from: http://www.apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/204381/1/WHO_ZIKV_SUR_161_eng.pdf?ua=1 .

- 25.Luby SP, Rahman M, Hossain MJ, Blum LS, Husain MM, Gurley E, et al. Foodborne transmission of Nipah virus, Bangladesh. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:1888–94. doi: 10.3201/eid1212.060732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harit AK, Ichhpujani RL, Gupta S, Gill KS, Lal S, Ganguly NK, et al. Nipah/Hendra virus outbreak in Siliguri, West Bengal, India in 2001. Indian J Med Res. 2006;123:553–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dikid T, Jain SK, Sharma A, Kumar A, Narain JP. Emerging and re-emerging infections in India: An overview. Indian J Med Res. 2013;138:19–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shrivastava A, Srikantiah P, Kumar A, Bhushan G, Goel K, Kumar S, et al. Outbreaks of unexplained neurologic illness – Muzaffarpur, India, 2013-2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64:49–53. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Russo DH, Luchs A, Machado BC, Carmona Rde C, Timenetsky Mdo C. Echovirus 4 associated to hand, foot and mouth disease. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2006;48:197–9. doi: 10.1590/s0036-46652006000400004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhu Z, Xu WB, Xu AQ, Wang HY, Zhang Y, Song LZ, et al. Molecular epidemiological analysis of echovirus 19 isolated from an outbreak associated with hand, foot, and mouth disease (HFMD) in Shandong Province of China. Biomed Environ Sci. 2007;20:321–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rahi M, Gupte MD, Bhargava A, Varghese GM, Arora R. DHR-ICMR guidelines for diagnosis and management of rickettsial diseases in India. Indian J Med Res. 2015;141:417–22. doi: 10.4103/0971-5916.159279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rathi N, Kulkarni A, Yewale V. For Indian Academy of Pediatrics Guidelines on Rickettsial Diseases in Children Committee. IAP guidelines on rickettsial diseases in children. Indian Pediatr. 2017;54:223–229. doi: 10.1007/s13312-017-1035-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eady EA, Cove JH. Staphylococcal resistance revisited: Community-acquired methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus – An emerging problem for the management of skin and soft tissue infections. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2003;16:103–24. doi: 10.1097/00001432-200304000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cohen PR, Grossman ME. Management of cutaneous lesions associated with an emerging epidemic: Community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus skin infections. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:132–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2004.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Naimi TS, Anderson D, O’Boyle C, Boxrud DJ, Johnson SK, Tenover FC, et al. Vancomycin-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus with phenotypic susceptibility to methicillin in a patient with recurrent bacteremia. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:1609–12. doi: 10.1086/375228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jain R, Danziger LH. Multidrug-resistant acinetobacter infections: An emerging challenge to clinicians. Ann Pharmacother. 2004;38:1449–59. doi: 10.1345/aph.1D592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Primm TP, Lucero CA, Falkinham JO., 3rd Health impacts of environmental mycobacteria. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2004;17:98–106. doi: 10.1128/CMR.17.1.98-106.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]