Abstract

One 2-year-old undernourished girl presented to our outpatient with large erythematous scaly plaques in arm along with multiple bony swellings over nose, fingers, left foot, and back for the past 1 year. Apart from skin and bone lesions the girl was also had intermittent fever, pallor, irritability, and malnourishment. Her parents gave a history of incomplete healing at the BCG vaccination site. The case was diagnosed to be case of disseminated mycobacterial infection skin and bone with the help of histopathology, radiological examination, and DNA polymerase chain reaction (PCR). DNA PCR from the skin lesion came positive for mycobacteria tuberculosis complex. The girl was treated with 6 months of standard antitubercular drug treatment with very good improvement not only of her cutaneous and bone changes but also of her general health and growth. We report the case because paucity of similar infection in literature and for greater recognition of potential epidemiological threat.

KEY WORDS: BCG, disseminated mycobacterial infection, immunocompetent, lupus vulgaris, polymerase chain reaction

What was known?

BCG was rarely reported to cause skin or bone Tuberculosis in immunocompromised hosts

Introduction

BCG is a live vaccine derived from an attenuated strain of Mycobacterium bovis. It is recommended as a routine vaccination in tuberculosis endemic areas by the WHO and is a part of the National immunization schedule in India.[1] Although the vaccine is considered avirulent, very rarely cutaneous complications in the form of nonhealing ulcer (>3 months), lupus vulgaris, hypertrophic scar and keloid, abscess formation, etc., have been reported.[2] Lupus vulgaris following BCG is a rare phenomenon. Following a single injection of BCG, the risk is estimated at between 1 per 100,000 and 200,000 vaccinated persons.[3,4] Hence, the vaccine is considered extremely safe as the number of such cases is exceedingly low considering the wide usage of this vaccine as a part of routine vaccination. However, a proven case of disseminated mycobacterial infection following BCG vaccine, extending to involve not only skin but also multiple bones has not been reported to the best of our knowledge.[5] Here, we report this unusual case of cutaneous mycobacterial infection with extensive bony involvement following a single injection of BCG vaccine in an otherwise immunocompetent 2-year-old child.

Case Report

A 2-year-old malnourished girl presented to our outpatient department with erythematous scaly plaque over left upper arm. She also had bony swellings over nose, fingers, left foot, and back for the past 1 year. The child was highly irritable and pale looking and as per the parents, suffered from intermittent low-grade fever. History revealed that the girl was delivered as a healthy baby of an apparently healthy mother in a hospital setting. She was in perfect health at birth with a normal birth weight. BCG vaccine as a part of national immunization protocol was given to the baby at the age of 6 weeks. She received other vaccines on time. As reported by the parents the vaccination was followed by development of an erythematous papule over the arm, which ulcerated after 1 month. However, the ulcer never actually healed completely in spite of various topical medications. The ulcerated lesion kept increasing in size slowly for the next 3 to 4 months; finally, developing into a large plaque of size 5 cm × 8 cm [Figure 1]. The lesion was painless. At around 1 year of age however, the parents noted appearance of multiple bony swellings involving fingers, foot, root of nose, and vertebral column. [Figures 2–4] The swelling over the fingers was painful and associated with ulceration and discharge. The skin overlying foot and back swelling was relatively normal, except for mild ichthyotic changes. Throughout this period, the plaque over the arm kept on increasing in size slowly.

Figure 1.

Scaly erythematous plaque over left upper arm

Figure 2.

Bony swellings of phalanges with scaly plaques on the overlying skin

Figure 4.

Bony swelling over back

Figure 3.

Bony swelling on right foot with ichthyotic changes of skin

Apart from the skin and bone changes, the child also suffered from low-grade intermittent fever and loss of appetite. However, there was no history of chronic cough, hemoptysis; neither there was any symptoms of gastrointestinal or central nervous system involvement. There was also no history of contact in the family or neighborhood. The child had been treated with oral and intravenous antibiotics on several occasions over the past year but the symptoms persisted.

On examination, the child was found to be malnourished. Her body weight was 8 kg, which was around 70% of the expected weight for a child her age. She was pale, irritable, and her body temperature was 98.7 F. The plaque over the left arm was 5 cm × 8 cm in size at the time. It was erythematous, indurated, and scaly with a raised and irregular border. There was central atrophy with areas of scarring and surrounding xerotic skin. At the root of the nose, a hard swelling was seen but with no surface changes. Tender bony swellings were also seen over left middle finger and right thumb with overlying scaly, erythematous plaque. A diffuse swelling could also be felt over dorsum of left foot, which was firm and tender. Similar such swelling was seen over the upper back in midline. No lymphadenopathy was noted however, with spleen and liver apparently normal, the child was otherwise normal.

Laboratory investigations showed normocytic normochromic anemia (Hemoglobin- 8.3 gm%), raised white blood cell count and a raised ESR. Mantoux test was done and was positive (9 mm × 10 mm). X-ray of the bones revealed lytic lesions in the involved areas [Figures 5 and 6]. USG of whole abdomen and the chest X-ray were within normal limits. ELISA for HIV was negative.

Figure 5.

Skiagram of feet showing lytic changes in involved bones

Figure 6.

Skiagram of hands showing lytic changes in phalanges

At this moment, in consultations with her pediatrician we had two differential diagnoses: Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) or disseminated tuberculosis following BCG vaccination.

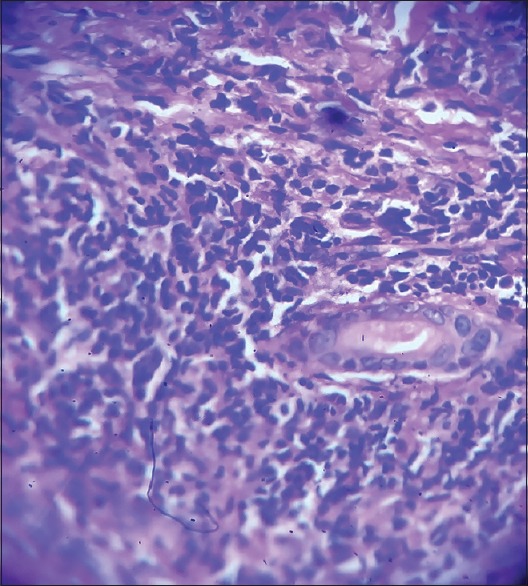

To establish the diagnosis, a skin biopsy was taken from the plaque and histopathology was done. Under light microscopy, tuberculoid granulomas were seen with giant cells in the dermis [Figure 7]. Ziehl-Neelsen stain for acid-fast bacilli was negative, and so was Periodic acid–Schiff stain for fungus. We also did the special immune-stain for CD1a. However, the immune-stain came negative ruling out LCH.

Figure 7.

Histopathology of skin lesion showed tuberculoid granulomas with giant cell formation (H and E, ×40)

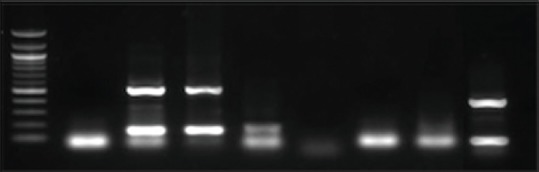

To avoid delay in treatment, the child was admitted and started on a trial of standard antitubercular drugs, with a provisional diagnosis of disseminated BCG infection. In the meantime, a culture was done for Mycobacterium, but it came out to be negative with no growth seen after 8 weeks. However the child responded very well to the treatment. Furthermore, to further establish the diagnosis, a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) sample was sent. The PCR showed positivity for Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex (MTC) [Figure 8].

Figure 8.

DNA polymerase chain reaction done on skin sample showed positivity for Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex

The case was diagnosed as disseminated tuberculosis with multiple skin and bony involvement, initiated by BCG vaccination.

The child was kept admitted to the department of Pediatrics and her treatment on standard antitubercular drugs were continued. Improvement was noted in her general condition too, soon after start of the treatment. The fever subsided and appetite returned to normal gradually. Cutaneous lesions as well as bone swellings started to regress. After 6 months of treatment, lesions had resolved completely with only residual scarring and deformity for which she was referred to department of Orthopedics [Figures 9–11].

Figure 9.

Improvement of plaque over left upper arm after 6 months of antitubercular drug

Figure 11.

Improvement seen of foot lesion post antitubercular drug

Figure 10.

Mild contracture of fingers remained at the end of 6 months

Discussion

Although there are at least 65 cases of inoculation tuberculosis reported after BCG vaccination till date,[6] our case was peculiar in many regards. First, it is a case of disseminated mycobacterial infection involving not only the site of BCG vaccination but also remote sites like fingers of both hands. Disseminated mycobacterial infection had been reported very infrequently in medical literature, incidence of disseminated BCG being 0.19–1.56 cases per million of vaccinated children.[7,8] Second, our case also had multiple bone involvement ranging from axial structure to the peripheral small bones. To the best of our knowledge, mycobacterial involvement of bone and skin following BCG vaccination was only reported once in medical literature, that too in 1954.[9] Third, the few cases of disseminated infection following BCG vaccination reported till date, were mostly seen in the immunocompromised patients;[7,8] however, in our case the child had no sign of immune depression. Fourth, in disseminated mycobacterial infection there are often reports of fever, lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, fistulization, stunted growth, etc., as associated clinical features. In our case, the patient had no associated feature of growth reduction, lymphadenopathy, or hepatosplenomegaly. However, our patient had weight loss, low-grade intermittent fever, and lupus vulgaris such as skin lesions and bone involvement in the form of multiple swellings over fingers, foot, and back and most importantly a history of nonhealing BCG scar which progressed to form a plaque in course of time, all of these pointed toward a diagnosis of disseminated mycobacterial infection in an immunocompetent child.

However, fifth and most important feature in our case was that we did PCR to confirm the diagnosis of mycobacterial infection following BCG vaccination, which was positive for MTC. To the best of our knowledge, a proven case of disseminated infection of both skin and bones after BCG injection is yet to be reported.

Soon after the treatment was started with standard antitubercular drugs, the child showed very good improvement. Not only the skin lesions but also the bones showed marked improvement after 6 months of treatment. After completion of treatment, she had only a few scars remaining, she had no fever and irritability, and her weight and appetite improved.

This child for some reason could not be given vaccine at birth that may have some effect on the immune status of the child. BCG vaccination though universal and regarded very safe, our case shows that there may be a chance of disseminated mycobacterial infection, especially if the vaccination is delayed. High degree of clinical suspicion is required in case of delayed healing in the BCG site. A positive culture can always clinch the diagnosis. Moreover, whenever possible, an early PCR should be done.

We report this unusual case of disseminated mycobacterial infection following BCG vaccination involving both skin and bones in an immunocompetent child where PCR showed positivity for MTC.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

What is new?

This is an unusual case of disseminated mycobacterial infection following BCG vaccination involving both skin and bones in an immunocompetent child.

Along with histopathology and other investigations, PCR was used to show positivity for MTC.

The patient responded very well with healing of both skin and bone lesions with standard Antitubercular regimen.

References

- 1.Fine PE, Carneiro IA, Milstien JB, Clements CJ. Issues relating to the use of BCG in immunization programs: A discussion document. Department of Vaccines and Biologicals. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1999. p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bellet JS, Prose NS. Skin complications of Bacillus Calmette-Guérin immunization. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2005;18:97–100. doi: 10.1097/01.qco.0000160895.97362.4f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Waaler H, Rouillon A. BCG vaccination policies as a function of the epidemiological situation. Bull Int Union Tuberc. 1974;49:181–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Horwitz O, Meyer J. The safety record of BCG vaccination and untoward reactions observed after vaccination. Bibl Tuberc. 1957;13:245–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aggarwal A, Aneja S, Taluja V, Anand R. Multifocal cystic bone tuberculosis with lupus vulgaris and lymphadenitis. Indian Pediatr. 1997;34:443–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Farsinejad K, Daneshpazhooh M, Sairafi H, Barzegar M, Mortazavizadeh M. Lupus vulgaris at the site of BCG vaccination: Report of three cases. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:e167–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2008.03041.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scheifele D, Law B, Jadavji T. Disseminated bacille Calmette-Guérin infection: Three recent Canadian cases. IMPACT. Immunization Monitoring Program, Active. Can Commun Dis Rep. 1998;24:69–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marciano BE, Huang CY, Joshi G, Rezaei N, Carvalho BC, Allwood Z, et al. BCG vaccination in patients with severe combined immunodeficiency: Complications, risks and vaccination policies. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:1134–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.02.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Imerslund O, Jonsen T. Lupus vulgaris and multiple bone lesions caused by BCG. Acta Tuberc Scand. 1954;30:116–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]