Abstract

This paper details the grounds for compulsory treatment, compulsory admissions in an emergency department and compulsory out-patient treatment in Portugal. Portuguese mental health legislation has improved significantly over recent years, with enhanced safeguards, rapid and rigorous review and clear criteria for compulsory treatment, although much remains to be done, especially in relation to the ‘move into the community’.

Portugal is a country in south-western Europe with a total area of 92 345 km2 and a population of around 10.5 million people. There are 6.14 psychiatrists per 100 000 population (World Health Organization, 2011).

The first Mental Health Act in Portugal was adopted in 1963. At around that time the need to integrate mental health services with the general healthcare system was becoming increasingly clear. National mental health programmes in 1985 and 1989 included important measures to integrate mental healthcare in general hospitals and to develop community mental health. In 1992 legislation stipulated the integration of all mental health centres into general hospitals. However, the development of community mental health services initiated in the 1980s was interrupted in the early 1990s, for political reasons. The need to review the mental health law in Portugal and consequently the way mental health services were organised became increasingly urgent with the recommendations from the United Nations and the World Health Organization (WHO) that the provision of mental healthcare be undertaken primarily at the community level and in the least restrictive environment possible. They went on to direct that psychosocial rehabilitation should occur in residential structures, day centres and training and professional rehabilitation units, which were part of the community and adapted to the patient’s specific degree of autonomy.

Current legislation

New mental health legislation was approved in 1998 (Law 36/98), which resulted from the pressure of the movements in favour of community care and human rights. It faced strong opposition from the most conservative groups of the psychiatric establishment (the same groups behind the interruption to the introduction of community care).

The 1998 law has national coverage and applies to all Portuguese citizens. It defines the principles governing compulsory detention of people who are mentally ill and their rights. It also establishes the general principles of the organisation and provision of services and the mental health policy. Decree 35/99, which regulates the law, includes the basis of the mental health policy and describes in great detail the organisation of mental health services.

The law emphasises that mental healthcare should be primarily provided at the community level and in the least restrictive environment. In the ensuing years important steps have been taken in this direction, but hospitalisation continues to consume the majority of resources (Caldas de Almeida, 2009) and the treatment of mental disorder usually takes place on an in-patient basis in large general hospitals. Another important issue is the fact that the law does not provide for the institution of compulsory treatment in the community, although compulsory community treatment can follow admission.

According to the law all patients using mental health services have the right to:

adequate information regarding their rights, the proposed treatment plan, and expected effects

treatment and protection based on respect for individuality and dignity

autonomy to accept or decline interventions, except in cases of compulsory detention or in emergency situations in which non-intervention would pose verifiable risks to the person or to others

not be submitted to electroconvulsive therapy without previous written consent

accept or refuse to participate in investigations, clinical trials or training activities

benefit from ‘proper’ conditions in hospital and residential services

have outside contact and be visited by family, friends and legal representatives

receive just remuneration for activities performed or services rendered

receive support in exercising the rights of protest and complaint.

Psychosurgery requires previous written consent and the favourable opinion of two psychiatrists designated by the National Council of Mental Health (a government advisory body).

A person can be detained only where it is deemed proportionate to the risk and it is the only way of guaranteeing that the patient receives treatment. Whenever possible, detention should be converted to out-patient treatment and compulsion should be suspended as soon as possible. If a patient is unable to give informed consent or if the patient is under the age of 14 this shall be exercised by legal representatives.

Grounds for compulsion

The criteria for compulsory detention and treatment are:

a person suffering from a serious mental disorder by virtue of this condition represents a danger to him- or herself, or others, and refuses to submit to the necessary medical treatment

the person suffering from a serious mental disorder lacks the necessary capacity to evaluate the meaning and implications of consent and the absence of treatment could result in a significant deterioration of his or her condition.

Detention may be petitioned by: the legal representative of a person suffering from a mental disorder; any person eligible to apply for his/her interdiction; public health authorities; the Public Prosecution Service; doctors; or the clinical director of an institution, in cases where detection of a mental disorder occurs in the course of a voluntary admission to that institution.

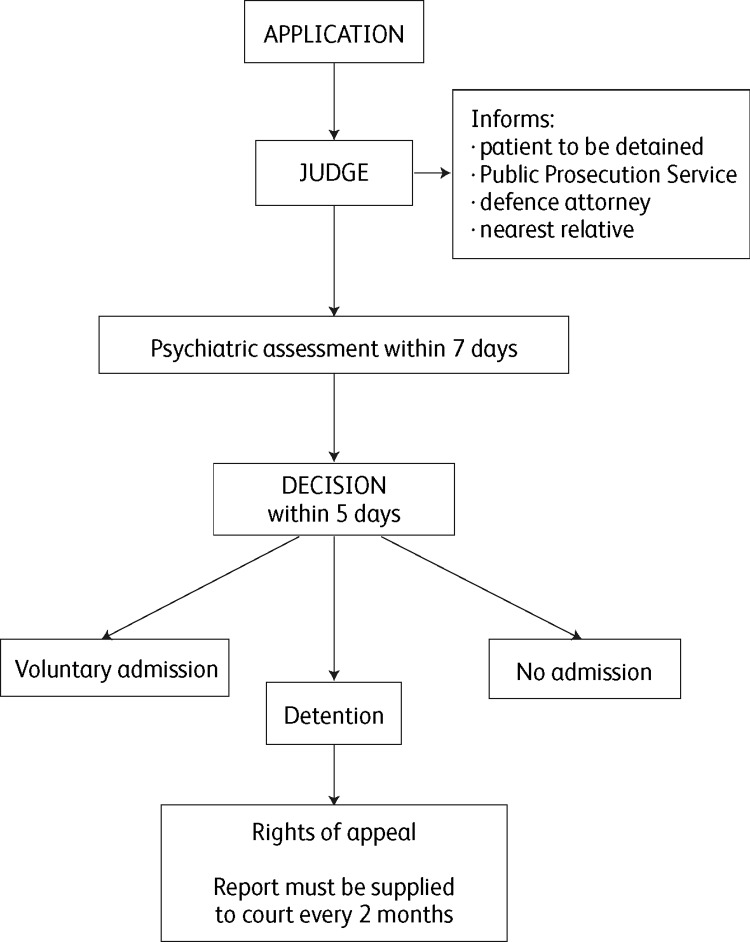

The final decision on compulsory detention is made by a judge on the advice of psychiatrists (based on their psychiatric assessment report). The decision-making process for compulsory detention and subsequent provisions are described in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. The decision-making process for compulsory detention and subsequent provisions.

Patients must be informed of their rights to be present in the procedural acts and to be heard by a judge, to be assisted by an appointed or nominated defence attorney, to submit evidence and to request the proceedings deemed necessary, and to appeal the decision. Patients also have the right to vote, to send and receive mail, and to communicate with the Monitoring Commission.

The detained patient is required to accept medically prescribed treatments.

Emergency admission

A person suffering from a serious mental disorder may be subject to emergency compulsory detention if there is imminent danger due to an acute deterioration of the person’s state.

The police or public health authorities may determine that the person suffering from a mental disorder be escorted to the nearest institution with a psychiatric emergency department for formal psychiatric assessment and the provision of appropriate medical assistance.

In cases where delay might be dangerous, any police officer may proceed with the immediate escort of the patient. The local Public Prosecution Service must be advised immediately.

In cases when the psychiatric assessment determines the need for detention and the patient opposes such a measure, the institution shall immediately communicate the admission of the patient to the relevant court, with a copy of the warrant and assessment report. After conducting the necessary steps, the judge shall issue a decision regarding whether detention should or should not be maintained, within a maximum of 48 hours from the deprivation of liberty. Upon receipt of the communication, the judge shall begin the compulsory detention process and shall therefore order a new psychiatric assessment to take place within 5 days by two independent psychiatrists and with the possible assistance of other mental health professionals. Upon receipt of the psychiatric assessment a date shall be set for the joint session.

In cases where the psychiatric assessment does not determine the need for detention, the person must be immediately set free.

Compulsory out-patient treatment

Compulsory out-patient treatment can be used instead of compulsory detention if it is deemed safe and as long as the patient complies with the necessary requirements. These requirements are stipulated by the attending psychiatrist. Whenever the patient does not meet the stipulated conditions, this situation shall be reported to the competent court and detention shall be resumed (if necessary with warrants to be executed by the police). We could find no data at service level or patient level regarding the use of community compulsion.

Conclusions

A new National Mental Health Policy and Plan (2007–16) has been developed. It aims to achieve equal access to quality care for everyone with mental disorders in the country, including those belonging to vulnerable groups. It aims to promote and protect the human rights of people with mental disorders, reduce the impact of illness and contribute to the promotion of mental health. The integration and community focus of mental healthcare and the reduction of stigma are additional objectives.

One of the biggest challenges is proving to be the ‘move into the community’. This is undoubtedly for complex reasons but the effect of the recent financial crisis on health budgets is a very important factor.

Portuguese mental health legislation has improved significantly over recent years, with enhanced safeguards for patients, rapid and rigorous review and clear criteria for compulsory treatment. However, much remains to be done overall. Data regarding compulsory detention in Portugal are scarce. We could find data for compulsory admissions from 1999 and 2000 in only one paper (Xavier, 2002). Rates of compulsory admission were apparently very low, at 2.8% and 3.2% of overall admissions; this we believe is an artefact of historically poor recording of such data and bears little relation to the true extent of compulsory care. This poor recording of important legal and health interventions is unacceptable and there is a critical need for it to be remedied to provide evidence on which to base care.

Both routine service data and empirical research can bring clarity, and this information is urgently needed. Such initiatives should allow for a better understanding of the legal position and the use of both compulsory powers and the associated safeguards. There are encouraging signs, at least in Oporto, that this is beginning to happen.

References

- Caldas de Almeida, J. M. (2009) Portuguese National Mental Health Plan (2007–2016) executive summary. Mental Health in Family Medicine, 6, 233–244. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2011) Global Health Observatory Data Repository – Portugal statistics summary. Available at http://apps.who.int/gho/data/node.country.country-PRT?lang=en (accessed December 2015).

- Xavier, M. (2002) Member states: Portugal. In Compulsory Admission and Involuntary Treatment of Mentally Ill Patients – Legislation and Practice in EU-Member States: Final Report (eds Salize H., Dressing H. & Peitz M.), pp. 123–130. Central Institute of Mental Health. [Google Scholar]