Abstract

Prevention of mental illness and mental health promotion activities across Europe have gathered some pace since the launch of the European Union’s Pact for Mental Health and Well-Being in 2008. Within the context of a large treatment gap in mental health and limited resources to meet the high demand for mental healthcare, a concerted effort is now needed to ensure that initiatives in both mental illness prevention and mental health promotion become a fundamental part of where we are educated, work and live. Cost-effective, evidence-based approaches in prevention and promotion make these initiatives more accessible.

The importance of prevention of mental illness (PMI) and mental health promotion (MHP) cannot be emphasised enough. Samele et al (2013) profiled current mental health systems and developments in PMI and MHP in 29 European countries, including all the member states of the European Union (EU). The European Pact for Mental Health and Well-Being (2008) laid the foundations for encouraging EU member states to adopt PMI and MHP interventions. The Council of Europe (2011) reiterated the importance of PMI and MHP. The need to encourage EU member states to implement such initiatives has become pressing.

Large numbers of people experience mental health problems in Europe (Wittchen et al, 2011). The economic costs alone were estimated to be €798 billion in 2010 (Gustavsson et al, 2011). The treatment gap is another source of major concern – many people who need mental healthcare and treatment are not receiving it. Alonso et al (2007) found that almost half of those who need treatment do not seek professional help.

Suggestions for tackling these seemingly insurmountable issues have centred on improving access to treatment, expanding the existing mental health workforce and improving treatments, particularly talking therapies. For example, the Mental Health Gap Action Programme (mhGAP) for low- and middle-income countries was developed to facilitate the delivery of evidence-based interventions in non-specialised healthcare settings, with some opportunities for PMI and MHP (World Health Organization, 2010).

While these suggestions are important, a concerted effort is also needed to ensure that PMI and MHP feature both within and alongside evidence-based treatments and, more importantly, that PMI and MHP become a fundamental part of where we are educated, work and live. Coordinating such activities may appear tricky, but the key is to involve agencies outside the health sector, such as schools, the workplace and local communities. Convincing such agencies to adopt best practice has become easier with a growing evidence base on what works in PMI and MHP, and can produce significant cost savings. For example, every £1 spent on mental health promotion in the workplace results in a net saving of £10 (Knapp et al, 2011). The economic case alone is compelling: it makes good sense to invest in PMI and MHP.

Findings from the European Profile of Prevention and Promotion in Mental Health (EuroPoPP-MH) project show that improving the mental health and well-being of the population is slowly becoming a reality (Samele et al, 2013). These are important themes for around two-thirds of the countries examined, at least in policy terms. Suicide prevention is a key priority, particularly for countries with traditionally high rates of suicide (Hungary, Latvia and Lithuania). Early detection and early intervention have also been prioritised in an effort to reduce the potential for enduring and severe mental illness and to prevent further relapse. Combating stigma has also featured in recent mental health policies for Greece, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Slovenia and Spain.

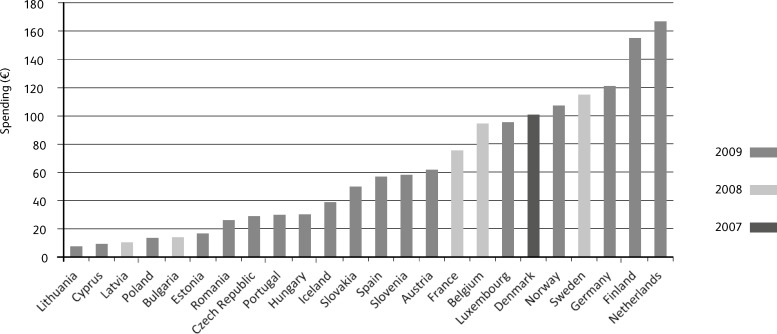

However, limited or no financial backing for these policy priorities often stalls their implementation. Precise figures for investments in PMI and MHP across EU countries are not available but expenditure on general illness prevention and public health services are. Fig. 1 illustrates the huge variation between 24 EU countries in expenditure on illness prevention and public health services. Ten of these countries spend less than €30 per head, while six spend more than €100 per capita. In the UK, less than 0.0005% of the National Health Service budget for mental health is spent on prevention and promotion (Campion, 2013).

Fig. 1. Spending (euros) per capita on general illness prevention and public health services (source: Eurostat, 2012).

The Netherlands and Finland spend over €140 per capita on health prevention and public health services (Fig. 1). The Netherlands has built within its national health policy a national infrastructure to enhance health prevention and promotion work (e.g. prevention workers, health promoters), including specific activities in mental health. Municipalities have the main responsibility for prevention work. In Finland, several national programmes for mental health have been in place over the past decade encouraging people to make healthy lifestyle choices (e.g. the Meaningful Life Programme).

The EuroPoPP-MH project found schools to be a common setting for PMI and MHP programmes, which is appropriate given that half of adult mental health problems start in adolescence, with many resulting in lifelong disability (Jones, 2013). Of the 381 programmes reported to the project, 44.3% were located in schools and 22.6% in the workplace, while 26.5% were aimed at the general population. Only 6.6% targeted older people, yet the prevalence of depression among those aged 50 years and more can be as high as 19.5% (Volkert et al, 2013).

There is still much to be done and further pursuit of PMI and MHP initiatives is critically important. Guidance on PMI and MHP and evidence-based interventions is available. The European Psychiatric Association, for example, has produced guidance on PMI (Campion et al, 2012) and MHP (Kalra et al, 2012). There is also guidance (Joint Commissioning Panel for Mental Health, 2013) on commissioning these initiatives locally and on interventions to prevent and treat mental illness early and promote well-being, particularly for those at high risk. Monitoring PMI and MHP interventions is also key to assessing improved health, public health and social outcomes, reduction in inequalities and economic savings.

The considerable gains that PMI and MHP can achieve warrant serious investment, particularly within the context of an ageing population and ever decreasing resources to meet the growing demand for mental healthcare and social care.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the Executive Agency for Health and Consumers which funded the EuroPoPP-MH project.

References

- Alonso, J., Codony, M., Kovess, V., et al. (2007) Population level of unmet need for mental healthcare in Europe. British Journal of Psychiatry, 190, 299–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campion, J. (2013) Public mental health commissioning guidance: embedding mental health in local public health work. Perspectives in Public Health, 133, 87–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campion, J., Bhui, K. & Bhugra, D. (2012) European Psychiatric Association (EPA) guidance on prevention of mental disorders. European Psychiatry, 27, 68–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Council of Europe (2011) The European Pact for Mental Health and Well-Being: Results and Future Action. Council of Europe. [Google Scholar]

- Eurostat (2012) Healthcare expenditure by function. At http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Healthcare_statistics (accessed December 2015).

- Gustavsson, A., Svensson, M., Jacobi, F., et al. (2011) Cost of disorders of the brain in Europe 2010. European Neuropsycho-pharmacology, 21, 718–779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joint Commissioning Panel for Mental Health (2013) Guidance for Commissioning Public Mental Health Services. JCPMH. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, P. B. (2013) Adult mental health disorders and their age at onset. British Journal of Psychiatry, 202, S5–S10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalra, G., Christodoulou, G., Jenkins, R., et al. (2012) Mental health promotion: guidance and strategies. European Psychiatry, 27, 81–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knapp, M., McDaid, D. & Parsonage, M. (eds) (2011) Mental Health Promotion and Mental Illness Prevention: The Economic Case. Department of Health. [Google Scholar]

- Samele, C., Frew, S. & Urquia (2013) Mental Health Systems in the European Union Member States, Status of Mental Health in Populations and Benefits to be Expected from Investments into Mental Health (EuroPoPP-MH). A report prepared on behalf of the Institute of Mental Health, Nottingham, for the EU Executive Agency for Health and Consumers. Available at http://ec.europa.eu/health/mental_health/docs/europopp_full_en.pdf (accessed December 2015).

- Volkert, J., Schulz, H., Harter, M., et al. (2013) The prevalence of mental disorders in older people in Western countries – a metaanalysis. Ageing Research Reviews, 12, 339–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittchen, H. U., Jacobi, F., Rehm, J., et al. (2011) The size and burden of mental disorders and other disorders of the brain in Europe 2010. European Neuropsychopharmacology, 21, 655–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2010) mhGAP Intervention Guide for Mental, Neurological and Substance Use Disorders in Non-specialized Health Settings. WHO. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]