Abstract

Infections with soil-transmitted helminths are among the commonest infections in Lao PDR. Recent investigation in this country determined that intestinal helminths currently infect the majority of school-aged children. The Lao Government has addressed the problem by organizing regular anti-helminthic chemotherapy with Mebendazole 500 mg for school and pre-school children in conjunction with health education activities incorporated into the national school curriculum.

The school de-worming campaign in Lao PDR reached a national coverage rate of 95% at a cost of 0.124 USD/head for two rounds of de-worming per year. The programme is under the umbrella of the national school health programme.

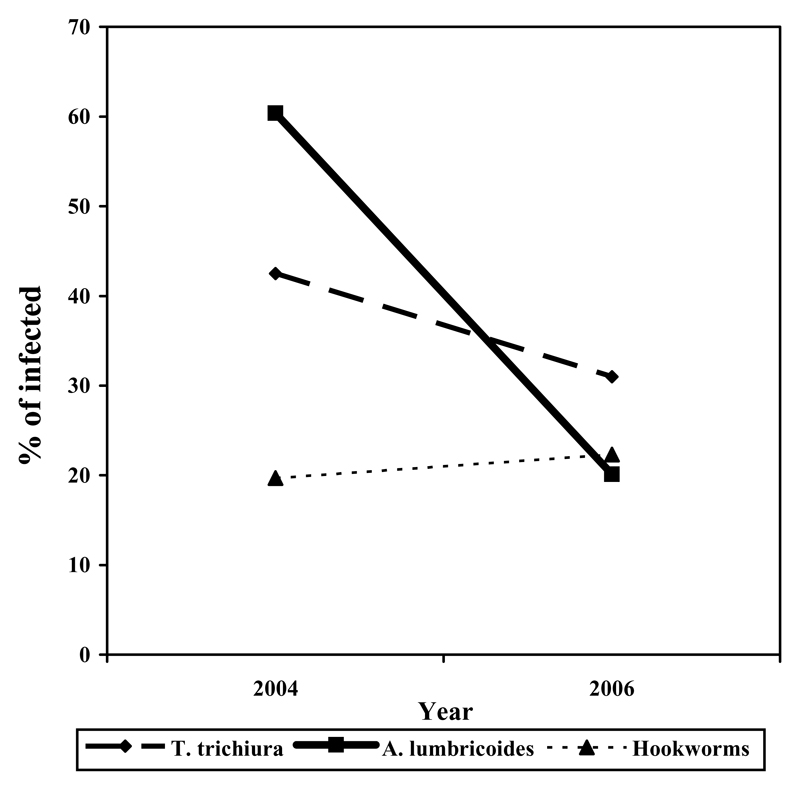

After one year (2 rounds of deworming) the intervention reduced the prevalence of Ascaris lumbricoides from 60% to 20% and of Trichuris trichiura from 42% to 31%.

Although infection was not eliminated by the de-worming interventions, of those children who remain infected, over 90% had a ‘light’ infection. The virtual absence of high and moderate intensity infection demonstrates the effectiveness of periodical de-worming in reducing the morbidity due to STH. We expect that additional rounds of deworming will further reduce the STH prevalence in Lao PDR.

Keywords: Deworming, School health, Cost, Lao PDR

Introduction

A nationwide parasitological survey of primary school-aged children in Lao PDR conducted in 2000-2002, shows that Soil Transmitted Helminth (STH) is intensively transmitted and that in some areas of the country, infection reaches a prevalence of 96 % (Rim et al 2003).

The Ministry of Health, Lao PDR consequently recognized STH infection as an important public health problem to be addressed urgently and nationwide (MoH 2003 and MoH 2008).

As a result, the “Helminth Control Policy” and the "National School Health Policy" have been formulated and a Memorandum of Understanding between the Ministries of Health and Education (MoH/MoE 2005) has been signed. Furthermore, a Joint National School Health Taskforce (JSHTF) composed of the Ministries of Health and Education has been established and now serves as a platform for additional collaboration between the two government sectors (MoH/MoE 2005).

The scaling up and cost of the de-worming activities in Lao PDR from September 2005 to April 2007 is presented here.

Materials and methods

In Lao PDR, according to statistics from the Ministry of Education (MoE, 2006):

The number of enrolled school children is 891 881.

The number of non-enrolled children is estimated at 123 000 individuals

The number of primary schools is more than 8 600

The total number of school-aged children is therefore estimated at 1 014 881 individuals. Primary schools are grouped into school clusters composed of 4-6 neighboring schools. In order to increase school attendance, in remote villages there are sub-schools (composed only by 1st or 2nd grade classes and that are administratively dependant by another school).

Programme Scale- up

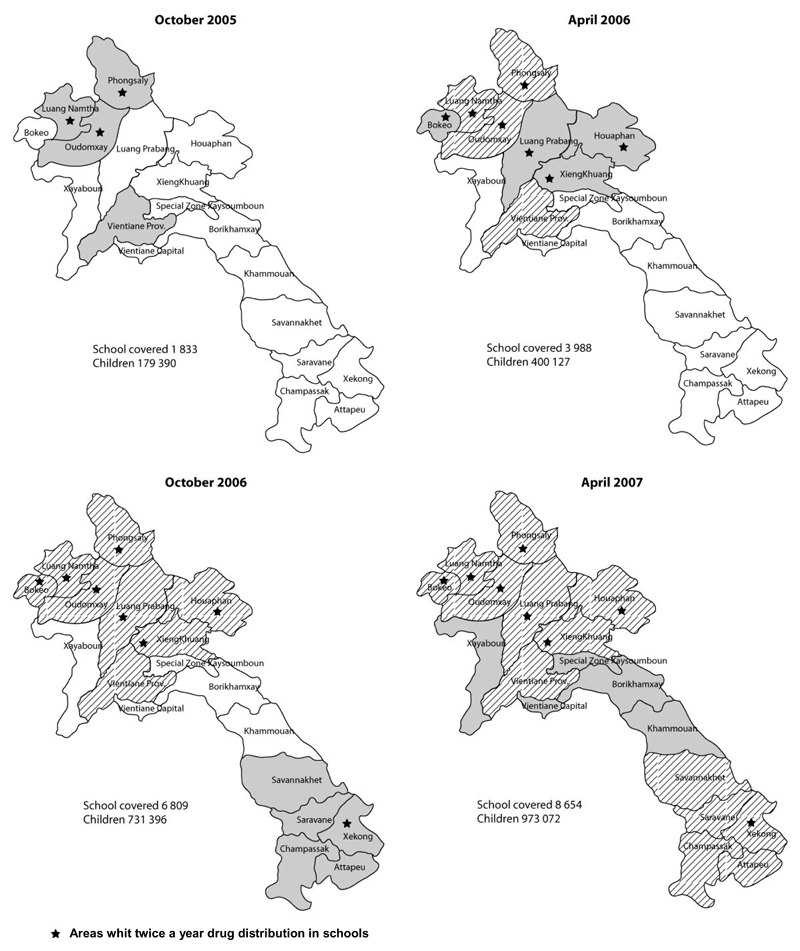

In September 2005, the National School Deworming Programme began under leadership of the JSHTF and covered only 4 provinces. The programme has since expanded progressively every 6 months (see Figure 1) and by April 2007 national coverage was reached. The school de-worming programme is presently targeting over 1 million primary school-aged children every year. Mass treatment is provided every 6 months, in April and October, of each school year in 8 provinces, and once per year in the remaining 9 provinces (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Scale-up of the Coverage of the School De-worming campaign in Loa PDR. The provinces in full color pattern are those de-wormed for the first time. The provinces with a striped pattern are those treated during the previous round. A star identifies the areas where schoolchildren are de-wormed twice a year.

Development of health education material

A set of Information, Education and Communication (IEC) materials was developed by JSHTF, in collaboration with a group of schoolteachers from Vientiane. The materials were pre-tested in 6 primary schools in Vientiane and were considered user friendly by the teachers and clearly understandable by the children. In total, 27 000 sets of IEC materials (including three posters, one comic book for children, and one information book for teachers) were produced at an approximate price of 1.1 USD/set. A set of IEC materials was distributed to each school and to each sub-school. The materials developed for this intervention have now become part of the National Health Education Curriculum for Primary Schools.

Training

Teacher training was organized as a cascade pathway:

Master Trainers, from JSHTF, were trained at central level in the following subjects:

how to administer de-worming drug to children in school

how to record the results

how to use two-way communication methods and materials to provide preventive health messages to the children

Each of these Master Trainers then conducted similar training for all health and education officials at provincial and district levels.

Drug Selection, transport and distribution

The Ministry of Health selected a single dose of Mebendazole 500 mg to be used for mass treatment because of its efficacy, safety and low cost. (WHO, 2002). The drug was transported from central to provincial capitals by the postal service or by public bus. From each provincial capital, the drug was then transported to the districts where monthly meetings between provincial and district education staff took place. District teams then re-packaged the drugs and education materials and distributed to each school cluster during cluster school meetings. Each teacher was encouraged to provide regular health education by using the IEC materials provided and to distribute one tablet of Mebendazole to each child during the day specifically selected for de-worming. (Figure 1 shows which provinces organized a de-worming day once or twice a year). No special financial incentives were provided to the teachers for distributing the drug. However, as compensation for the time spent during the de-worming activities they received four tablets of Mebendazole for the treatment of their family members.

Involvement of non enrolled school-age children

During the preparation phase of the de-worming day, teachers were requested to inform the schoolchildren in advance about the drug distribution. In addition, teachers asked the enrolled children to inform non-enrolled relatives or friends of primary school-age about the de-worming programme and to bring non-enrolled relatives or friends to school in occasion of the de-worming day. Furthermore, school directors informed village authorities about the campaign and asked them to disseminate the information to parents.

Programme monitoring

The programme coverage was monitored in two ways:

by recording the number of children dewormed reported in the forms completed by teachers during de-worming day

by carrying out Coverage Confirmation Surveys (CCS) conducted by JSHTF in the two weeks following the distribution.

Teachers were requested to record the number of children receiving de-worming tablets on de-worming days. This data was summarized by district and provincial education offices. Data was also collected on side effects occurring during the drug distribution and on the satisfaction of the parents about the intervention.

To validate the results collected with the standard forms, a JSHTF team conducted a survey in 92 randomly selected schools in 12 provinces. A stratified sampling procedure was applied to account for the presence of the seven different ecological areas in the country.

Parasitological monitoring

A base line cross-sectional parasitological survey was conducted between May 2000 and June 2002 (Rim et al 2003) among 30 000 children in the 17 provinces of Lao PDR.

In October 2006 a cross-sectional parasitological survey among 1000 children in 4 randomly selected schools was carried out in four provinces (Bokeo, Houaphan, Luan Prabang and Xieng Khuang).

The results of the survey in 2006 have been compared with the results of the baseline survey collected in the same provinces (corresponding to a total of 2 885 school children). A parasitological follow-up survey is planned for the end of 2008.

Cost

All direct costs incurred during the organization, conduction and monitoring of the de-worming campaign were recorded and analyzed.

Results

Coverage

According with the forms completed by teachers and summarized at district and provincial level, the total number of drugs administered during the drug distribution round of April 2007 was 973 073, which corresponds to an overall coverage rate for enrolled and non-enrolled children of 95.8% (887 939 tablets were provided to school enrolled children corresponding to a coverage of 99.5 % and 85 134 to non-enrolled children corresponding to a coverage of 68.9%).The CCS survey conducted in May 2007 evaluated a coverage of 99,2 % of enrolled children which is consistent with the data collected directly by the teachers responsible for drug distribution.

Parasitological monitoring

The parasitological survey indicated a reduction in prevalence of 16.6% after 2 rounds of treatment. Details on infection prevalence and infection intensity are presented in Table 1 and Figure 2.

Table 1.

Comparison between baseline (2004) and the 1st monitoring after the intervention (2006) of the Prevalence and Intensity of Intestinal Parasite Infection in 4 Schools.

| No. of children examined | Parasite specie | Intensity of infection | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative (%) | Light | Moderate | Heavy | |||||||

| 2004 | 2006 | 2004 | 2006 | 2004 | 2006 | 2004 | 2006 | 2004 | 2006 | |

| 2885 | 1000 | T. trichiura | 57.5 | 69.0 | 32.3 | 27.2 | 10.0 | 3.8 | 0.3 | 0.0 |

| A. lumbricoides | 39.6 | 79.9 | 23.1 | 10.9 | 31.1 | 7.3 | 6.7 | 1.9 | ||

| Hookworm | 80.3 | 77.7 | 17.6 | 20.1 | 0.8 | 1.5 | 0.3 | 0.7 | ||

Figure 2.

Changes in the Prevalence of STH Infection after 2 Rounds of MDA Treatment

Cost

Direct costs of the intervention, including training, drug procurement, printing of health education materials, are presented in Table 2. Capital costs are estimated at 0.11 USD per child per year, while the recurrent costs are estimated at 0.06 USD per round of treatment.

Table 2.

Financial cost of annual school deworming campaign among 973,073 school-aged children in Lao PDR.

| Cost | details | USD | Total (USD) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Capital cost | Training | Cost of cascade training for teachers in all primary schools* | 74 935 | |

| Health education | Development and printing of material | 32 237 | ||

| Total capital cost | 107 172 | |||

| Capital cost per child | 0.11 | |||

| Recurrent costs 1 round (17 provinces, 973,073 children) | Drug procurement | 1100 000 tablets of Mebendazole 500 mg | 43 016 | |

| Drug distribution | Distribution of the drug from central level to the 8 654 schools | 3 326 | ||

| Media Campaign | Radio and television advertising | 2 937 | ||

| Supervision and monitoring visits | 12 000 | |||

| Recurrent cost 1 round | 61 279 | |||

| Recurrent costs 2 round (8 provinces, 316,228 children) | Drug procurement | 363 662 tablets of Mebendazole 500 mg | 14 221 | |

| Drug distribution | Distribution of the drug from central level to the 3636 schools | 1 397 | ||

| Supervision and monitoring visits | 5 647 | |||

| Recurrent cost 2 round | 21 264 | |||

| Total recurrent cost per year | 82 543 | |||

| Recurrent cost per child treatment per year | 0.06 | |||

Training activities have been conducted in parallel with the scaling up of the programme.

In provinces requiring two treatments a year, the total cost (including capital costs and recurrent costs) was 0.23 USD per child per year, while in provinces requiring one treatment a year the cost was 0.17 USD per child per year.

After the first round of treatment only recurrent costs are incurred. We consider the capital cost would be repeated only every 5 years and therefore, considering a 10% discount rate, the total yearly cost 0.124 USD per child per year for two yearly rounds of de-worming.

Discussion

According to national statistics, about 40% of schools in Lao PDR are equipped with latrines and clean water (MOH, 2006). This low latrine coverage in schools exists alongside a similar situation at household level, the combination of which will maintain high re-infection rates for intestinal parasites among children. Given that the achievement of universal hygienic standards is expensive, difficult, and time consuming, it is therefore critical to execute effective de-worming to reduce the morbidity caused by STH in parallel to the promotion of a substantial improvement of hygienic standards and practice.

The school de-worming program in Lao PDR reported here demonstrates the capacity of this approach for attaining very high treatment coverage with low costs, similar to that reported in similar school de-worming programs in nearby Cambodia (where the estimated cost was between 0.122 and 0.057 USD –Sinuon et al., 2005) and Vietnam (where the estimated cost was between 0.03 and 0.11 USD – Montresor et al., 2006).

The Lao school de-worming programme also shows a higher coverage of non enrolled school age children than in other countries (Montresor et al, 2001, Talaat et al 2000,).

Although infection was not eliminated by the de-worming interventions among children, of those who remain infected, over 90% had a ‘light’ infection as defined by WHO (2002). The virtual absence of high and moderate intensity infection demonstrates the effectiveness of periodical de-worming in reducing the morbidity due to STH.

Even with the low programme-cost, it is difficult for the Ministry of Health to cover all the associated expenditure. Continued financial and technical support of external donors is essential for the sustainability of the programme. This is an area of concern. However, new initiatives, like the Mebendazole Donation Initiative (Task Force For Child Survival and Development 2007) are being started with the aim of providing free anti-helminthic drugs to endemic countries. These drug donation initiatives could address sustainability problems in Lao PDR since the drug cost represents 70% of the recurrent cost and 50% of the total cost of the program.

The new national policy for helminth control of Lao PDR (MoH 2008) recommends the regular treatment of the group most at risk for STH infections (pre-school children, primary school age children and women of child bearing age) and the integration of such interventions with other programs providing mass drug administration for the control of lymphatic filariasis, schistosomiasis and Opistorchiasis. If successfully executed, this would be a firm basis for an integrated parasite control intervention across the country. We hope that sufficient funding will be available for control of all these infections.

Acknowledgement

This article is dedicated to the memory of Dr. Carlo Urbani, who devoted his life to the control of parasitic infections. We wish to acknowledge the significant contributions of all Lao teachers and local health staff in the implementation of this school de-worming campaign. Financial support for the de-worming campaign was provided from the Government of Luxemburg.

We would like to thank Dr P. Rogers for the help in editing the manuscript.

Funding: None

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None declared

Ethical approval: Not requested

Authorship statement

CC, JH and AM designed the study protocol; BP, KS, HS and DS organized the intervention and the data collection. CC, VN-F and AM analyzed the data, CC, AM and HS drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. AM and JH are guarantors of the paper.

References

- MoE. Statistics for school year 2006-07. Lao PDR Government Internal document; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- MoH. National Intestinal Helminth Prevention and Control Policy. Lao PDR Government Internal document; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- MoH. Final Report on Intestinal Parasite Control among primary schoolchildren in Lao PDR (2000-2005) Lao PDR Government Internal document; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- MoH. National Policy and strategy to Prevent and Control Helminths. Lao PDR Government Internal document; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- MoH/MoE. National School Health Policy, Joint school Health taskforce of the Ministry of Education and Ministry of Health. Lao PDR Government; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Montresor A, Ramsan M, Chwaya HM, Ameir H, Foum A, Albonico M, Gyorkos TW, Savioli L. Extending anthelminthic coverage to non-enrolled school-age children using a simple and low-cost method. Trop Med Int Health. 2001;6:535–537. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2001.00750.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montresor A, Cong DT, Anh TL, Ehrhardt A, Thach CT, Thuan LK, Albonico M, Palmer K. Cost containment in school-deworming programme targeting over 2.7 million children in Vietnam. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2007;101:461–4. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2006.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rim HJ, Chai JY, Min DY, Cho SY, Eom KS, Hong SJ, Sohn WM, Yong TS, Deodato G, Standgaard H, Phommasack B, et al. Prevalence of intestinal parasite infections on a national scale among primary schoolchildren in Laos. Parasitol Res. 2003;1:67–72. doi: 10.1007/s00436-003-0963-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinuon M, Tsuyuoka R, Socheat D, Montresor A, Palmer K. Financial costs of deworming children in all primary schools in Cambodia. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2005;99:664–668. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2004.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talaat M, Evans D. The cost and coverage of a strategy to control schistosomiasis morbidity in non-enrolled school-age children in Egypt. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2000;94:449–454. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(00)90137-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Task Force for Child Survival and Development. A new partnership between Johnson & Johnson and the Task Force for Child Survival and Development. 2007 Available at the site: http://www.taskforce.org/

- WHO. Prevention and control of schistosomiasis and soil transmitted helminthiasis. Report of a WHO Expert Committee, Technical Report Series 912. Geneva: WHO; 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO. The Millennium Development Goals. The evidence is in: deworming helps meet the Millennium Development Goals. 2005. WHO/CDS/CPE/PVC/2005.12. [Google Scholar]