Abstract

Globally, women are at increased vulnerability to HIV due to biological, social, structural, and political reasons. Women living with HIV also experience unique issues related to their medical and social healthcare, which makes a clinical care model specific to their needs worthy of exploration. Furthermore, there is a dearth of research specific to women living with HIV. Research for this population has often been narrowly focused on pregnancy-related issues without considering their complex structural inequalities, social roles, and healthcare and biological needs. For these reasons, we have come together, as researchers, clinicians and community members in Canada, to develop the Canadian HIV Women’s Sexual and Reproductive Health Cohort Study (CHIWOS) to investigate the concept of women-centred HIV care (WCHC) and its impact on the overall, HIV, women’s, mental, sexual, and reproductive health outcomes of women living with HIV. Here, we present the CHIWOS cohort profile, which describes the cohort and presents preliminary findings related to perceived WCHC. CHIWOS is a prospective, observational cohort study of women living with HIV in British Columbia (BC), Ontario, and Quebec. Two additional Canadian provinces, Saskatchewan and Manitoba, will join the cohort in 2018. Using community-based research principles, CHIWOS engages women living with HIV throughout the entire research process meeting the requirements of the ‘Greater Involvement of People living with HIV/AIDS’. Study data are collected through an interviewer-administered questionnaire that uses a web-based platform. From August 2013 to May 2015, a total of 1422 women living with HIV in BC, Ontario, and Quebec were enrolled and completed the baseline visit. Follow-up interviews are being conducted at 18-month intervals. Of the 1422 participants at baseline, 356 were from BC (25%), 713 from Ontario (50%), 353 from Quebec (25%). The median age of the participants at baseline was 43 years (range, 16–74). 22% identified as Indigenous, 30% as African, Caribbean or Black, 41% as Caucasian/White, and 7% as other ethnicities. Overall, 83% of women were taking antiretroviral therapy at the time of the baseline interview and of them, 87% reported an undetectable viral load. Of the 1326 women who received HIV medical care in the previous year and responded to corresponding questions, 57% (95% CI: 54%-60%) perceived that the care they received from their primary HIV doctor had been women-centred. There were provincial and age differences among women who indicated that they received WCHC versus not; women from BC or Ontario were more likely to report WCHC compared to participants in Quebec. They were also more likely to be younger. CHIWOS will be an important tool to develop care models specific for women living with HIV. Moreover, CHIWOS is collecting extensive information on socio-demographics, social determinants of health, psychological factors, and sexual and reproductive health and offers an important platform to answer many relevant research questions for and with women living with HIV. Information on the cohort can be found on the study website (http://www.chiwos.ca).

Introduction

Life expectancy and quality of life for people with HIV in Canada have rapidly improved due to the successes of antiretroviral therapy (ART) and improved HIV care [1–3]. However, dampening these achievements is a persistent gender gap in access to, retention in, and quality of care that favours men in the Canadian context despite a steady representation of women in the HIV-positive population [4, 5]. The Public Health Agency of Canada estimated that the number of people with HIV at the end of 2014 was 75 500, of which 16 880 were women [6]. The number of positive HIV tests attributed to women in Canada has increased since the beginning of the epidemic with 23% of new infections occurring in women in 2014. While the proportion of all incident HIV cases occurring in women has stabilized at approximately one quarter, it is noted to be a concern that it has not decreased [6]. Globally, biological, social, structural, and political factors intersect to increase women’s vulnerability to HIV. In Canada, and many high-income countries, these inequities subsequently impact women’s experiences after HIV diagnosis; a phenomenon known as the feminization of HIV [5, 7–9]. This differs from the HIV gender gap in countries throughout sub-Saharan Africa [10–12], where women have been found to more readily engaged in care in some regions due to efforts focused within Maternal and Child Health Programs. However, this finding also highlights the 'gendered' vulnerability of HIV for women and how this calls for attention at national and regional levels for women-specific HIV services in Canada. In Canada, women’s vulnerability is the result of the complex intersection of gender with other dimensions of identity in systems where racism, colonial legacies, homophobia, transphobia, heterosexism, and sexism are inherent [13–15]. As such, Indigenous women, women from or who partner with men from HIV-endemic countries, women who use or used drugs, women involved in sex work, young women, and trans women are particularly vulnerable to HIV and constitute the majority of women with HIV in Canada [6,15].

Women with HIV also encounter added obstacles in healthcare in a clinical model that does not recognize their gendered experiences of HIV. Women with HIV frequently report worse clinical outcomes than men, including higher rates of viral rebound [16], lower quality of care [17] and inattention to their health and social needs [18]. Perpetuating this clinical insufficiency is the longstanding lack of research specific to women with HIV [19, 20]. When available, research for women with HIV has often been narrowly focused on pregnancy-related issues without considering their broader health issues [19]. Given the distinct ways that women with HIV are situated with respect to structural inequalities, social roles, biological needs, and healthcare complexities, it is crucial to address women with HIV’s specific health needs. As such, we have come together to develop and investigate the impact of a model of care called ‘women-centred HIV care (WCHC)’ in addressing these inequities. Recently, the World Health Organization (WHO) released a consolidated guideline on the sexual and reproductive health and rights of women living with HIV [21]. This WHO guideline calls for women-centred care [21], however, to date, little is known about this care model.

The Canadian HIV Women’s Sexual and Reproductive Health Cohort Study (CHIWOS), was created by, with, and for women with HIV in collaboration with academic researchers, clinicians, and community partners in response to calls from women with HIV for increased research focusing on the lives and care of women with HIV [22]. This cohort was developed to longitudinally investigate the concept of WCHC and its impact on the overall (quality of life), HIV (e.g., ART use, viral suppression), women’s (e.g., cervical cancer screening), mental (e.g., depression), sexual (e.g., sexual functioning and satisfaction), and reproductive (e.g., contraceptive use, pregnancy) health outcomes of women with HIV. Through a literature review and focus groups with women with HIV, an initial definition of WCHC was created: “care that supports women living with HIV to achieve the best health and wellbeing as defined by them. This type of care recognizes, respects, and addresses women’s unique health and social concerns, and recognizes that they are connected. Because this care is driven by women’s diverse experiences, it is flexible and takes their different needs into consideration”. The purpose of this paper is to describe our methodology and present the cohort and preliminary findings related to perceived WCHC.

Material & methods

Study guiding frameworks

Crucial to the functioning of the project, CHIWOS operates using a community-based research (CBR) approach [23], with the Greater Involvement of People Living with HIV (GIPA) [24] at its centre and follows the theoretical approaches of critical feminism, anti-oppression and intersectionality [25, 26]. Women with HIV have been involved with the project from the beginning and at every stage, and have been hired and trained in research conduction, as peer research associates (PRAs). The operationalization of CBR in this study is reviewed in detail elsewhere [27].

Study setting and population

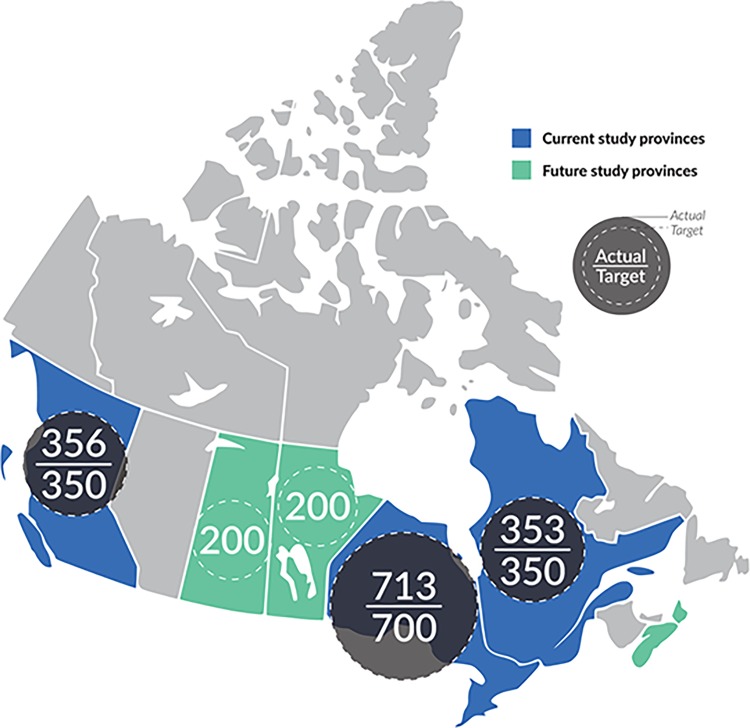

CHIWOS is currently being conducted in the three Canadian provinces of British Columbia (BC), Ontario (ON), and Quebec (QC) (Fig 1). These three provinces were initially selected because of the high percentage of women with HIV in Canada that would be captured in these study provinces (82%) [6]. Two additional Canadian provinces, Saskatchewan and Manitoba, are joining the cohort in 2018.

Fig 1. CHIWOS provinces with target and actual enrolment numbers.

Current Canadian HIV Women’s Sexual and Reproductive Cohort Study (CHIWOS) sites (in blue)–i.e. British Columbia, Ontario, and Quebec, and upcoming sites (in green)–i.e. Saskatchewan and Manitoba. Also shown are the target (dotted circles) and actual (dark circles) recruitment numbers per province.

Eligible participants self-identified as: women (including cis, trans, intersex, two-spirit and gender queer or questioning people who identified as women); being 16 years of age or older; being diagnosed with HIV; and living in one of the study provinces at the time of the baseline visit.

Study sampling and recruitment

The study applied a non-random, purposive sampling frame. Women with HIV were geographically enrolled based on the distribution of women with HIV in each provincial region as found in provincial public health reports [28, 29, 30]. Our sample size target was 350 women from BC, 700 women from ON, and 350 from QC, which allowed us to detect a 50% probability of a binary outcome at the provincial level, with +/- 10% margin of error, and a 90% confidence interval.

Our purposive sampling also aimed to enrol women who were potentially harder-to-reach and underserved to enable analysis regarding the healthcare access and needs, and health outcomes of a group of women often left out of research [31]. The groups of women defined as harder-to-reach were determined by investigators’ clinical expertise and difficulty in enrolling these populations into other studies [32]. The groups of women included as harder-to-reach are described in a supplemental Table and included trans women, Indigenous women, women who inject drugs and young women (< 30 years of age) (S1 Table).

Recruitment occurred from August 2013 to May 2015 through: 1) personal networks of and word-of-mouth by the PRAs and other women with HIV; 2) community-based and AIDS service organizations; 3) HIV clinics; 4) online through our website, Facebook page, and Twitter presence; 5) our provincial community advisory board members; and 5) posters and flyers posted in non-HIV-specific community settings where women attend such as women’s shelters.

Study procedures

Primary ethics approval was obtained from Women’s College Hospital (ON), Simon Fraser University (BC), University of British Columbia/Providence Health (BC), and McGill University Health Centre (QC) from their respective Research Ethics Boards (REBs). Study sites with independent REBs obtained their own approval prior to commencing enrolment.

Potential participants were screened by a trained PRA or the provincial coordinator. If they met the inclusion criteria, they were then provided with the informed consent to participate. After consenting, participants were asked to complete a PRA-administered web-based questionnaire, programmed using White Label FluidSurveys™ data capture software. Whenever possible, the interviewer-administered survey was carried out in person but when required was done by phone or Skype. The online programming included skip patterns and response validation towards maximizing data quality and providing ‘real time’ data capture. Surveys could be completed in English or French. For women who did not speak either language, the survey could be completed with the assistance of a translator. The median length of time to complete the baseline survey was 120 minutes [interquartile range (IQR): 90,150]. The lengthy survey completion time was vetted by the PRAs and deemed acceptable as important topics often left out of other research projects were included (e.g. violence and sexual health).

Follow-up visits are occurring at 18-month intervals. Eighteen-month follow-up was chosen so as to not over-burden women with research participation while allowing enough time to pass for changes to occur. An 18-month interval was also selected in an attempt to minimize recall bias and risks of loss-to-follow-up (LTFU).

Visit 2 questionnaires began June 23, 2015 and finished January 31, 2017. Follow-up was carried out by the same PRA (when possible) by contacting the participants by phone or email depending on the preferred means indicated by the participant. In order to maximize retention, follow up interviews were permitted beyond the 18-month window so long as they were completed before official closure of the follow up period. A follow-up procedure was developed including three attempts by the PRA, followed by contacting the community-based organization if one was involved in the initial recruitment. If not, re-contacting through the participant’s clinic was sought as long as the clinic had REB approval. Several additional methods were also used to minimize LTFU including an online presence and having close partnerships with community-based organizations. Visit 3 questionnaires began February 1, 2017.

Questionnaires and study variables

The baseline CHIWOS questionnaire collected extensive data on demographics, social determinants of health, HIV clinical outcomes, use of WCHC, health and social services use, psychological and emotional health, sexual and reproductive health, substance use, and experiences of violence, stigma, and discrimination [33]. The survey contained 436 questions and 2136 variables; however, participants completed only those questions relevant to their identity and experience. As the survey was the only means of data collection, all variables are self-reported including clinical variables such as viral load (VL) and hepatitis status. An extensive CBR approach to survey development was used and is described elsewhere [34]. The survey development team used validated scales when available. The final baseline questionnaire included nine sections that are presented in Table 1. Detailed descriptions of the themes covered and validated scales used in each questionnaire section are presented in S2 Table.

Table 1. CHIWOS questionnaire sections.

| Section | Section Topic |

|---|---|

| SECTION 1 | Demographics and Socio-economic Status |

| SECTION 2 | Medical and HIV Disease Information |

| SECTION 3 | Health Care and Support Service Utilization |

| SECTION 4 | Women’s Reproductive Health |

| SECTION 5 | Stigma and Discrimination |

| SECTION 6 | Substance Use |

| SECTION 7 | Violence and Abuse |

| SECTION 8 | Women's Sexual Health |

| SECTION 9 | Emotional Wellbeing, Resiliency, and Health Related Quality of Life |

Every question had the options of “don’t know” and “prefer not to answer” for the participant to answer. An answer was required for each question to move on to the next page. Sections 7 and 8 on Violence and Abuse and Women’s Sexual Health could be self-administered or declined due to the sensitivity of the topics and the risk of triggering.

Primary variable of interest

The primary variable of interest is the concept of WCHC that is measured in Section 3 with a scale that we developed based on our literature review and focus groups [5, 31]. We also developed a brief scale to assess overall perceived WCHC of the women’s HIV doctor and clinic. Perceived WCHC of one’s HIV clinic or doctor was assessed using a 5-point Likert scale measuring agreement with statements such as “Overall, I think that the care I have received from my HIV clinic (or doctor) has been women-centred”. Responses were categorized into: Strongly Agree/Agree (‘Perceived WCHC') vs. Neutral (‘Neutral WCHC’) vs. Strongly Disagree/Disagree (‘No perceived WCHC’). Our definition of WCHC was provided to participants prior to asking the set of WCHC questions.

Validity and test-retest reliability

An a priori strategy for ensuring and determining the baseline questionnaire’s validity and reliability was developed [22]. Test-rest reliability of the questionnaire measures was assessed among 30 participants (10 per province) completing the baseline questionnaire twice, separated by approximately 2 weeks [35]. The Kappa statistic and the intraclass correlation coefficient were used to assess reliability of categorical variables and continuous variables, respectively. We used the following cut-offs to interpret the strength of agreement for the Kappa coefficient: ≤0 = poor, .01–.20 = slight, .21–.40 = fair, .41–.60 = moderate, .61–.80 = substantial, and .81–1 = almost perfect.

Statistical analyses

The sociodemographic, clinical and WCHC variables were determined for the overall population and by province using frequencies and proportions for categorical variables and medians and either ranges or IQRs for continuous variables. Comparisons were made between provinces using the Chi-square test for categorical variables and the Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous variables.

Potential linkage to other data sources

CHIWOS has been designed to allow for data linkages to existing provincial and national administrative and research datasets, including the Drug Treatment Program (DTP) in BC, the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES) population-level data and the Ontario HIV Treatment Network Cohort Study (OCS) [36] in ON, and the Montreal HIV patient database of the AIDS Network of Fonds de Recherche du Québec-Santé (FRQS) and the Régie de l'assurance maladie du Québec (RAMQ) in QC. In addition, CHIWOS is affiliated with the Canadian Observational Cohort Collaboration (CANOC) [37, 38]. Linkage to administrative datasets allows for the validation of self-reported clinical and laboratory responses (e.g. VLs, CD4+ count and ART use). Also, such linkages could allow the merging and analyses of an administrative dataset with the CHIWOS dataset, which is rich in psychosocial and social determinant variables.

Results

Study population

As is seen in Table 2, CHIWOS has successfully enrolled a diverse cohort of 1422 women with HIV (356 from BC [25%], 713 from ON [50%], 353 from QC [25%]). Baseline demographics are presented in Table 2. The median age of the participants was 43 years (range, 16–74). Participants represented diverse communities: 22% identified as Indigenous, 30% as African, Caribbean, or Black, 41% as Caucasian/White, and 7% as other ethnicities. The CHIWOS cohort successfully enrolled harder-to-reach or underserved communities of women with 31% and 6% reporting injection drug use history and current sex work, respectively. Overall, 83% of women were currently taking ART and 87% of them reporting an undetectable VL.

Table 2. Baseline characteristics of study participants overall and by province.

| Demographic Characteristics | N with | Total | British Columbia | Ontario | Quebec | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| responses | N = 1422 | N = 356 | N = 713 | N = 353 | ||

| Median Age (IQR) | 1422 | 43(36–51) | 44(37–51) | 41(34–49) | 46(38–53) | <0.001 |

| Gender identity | 1422 | |||||

| Woman | 1359 (96%) | 342 (96%) | 679 (95%) | 338 (96%) | 0.804 | |

| Trans woman/Two-spirit/Queer/Intersex/Other | 63 (4%) | 14 (4%) | 34 (5%) | 15 (4%) | ||

| Sexual orientation | 1417 | |||||

| Heterosexual | 1237 (87%) | 294 (83%) | 617 (87%) | 326 (92%) | <0.001 | |

| LBQQ2S | 180 (13%) | 61 (17%) | 92 (13%) | 27 (8%) | ||

| Ethnicity | 1422 | |||||

| Indigenous–First Nations, Métis or Inuit | 318 (22%) | 161 (45%) | 149 (21%) | 8 (2%) | <0.001 | |

| African/Caribbean/Black | 418 (30%) | 28 (8%) | 227 (32%) | 163 (46%) | ||

| Caucasian/White | 585 (41%) | 139 (39%) | 280 (39%) | 165 (47%) | ||

| Other* | 103 (7%) | 28 (8%) | 57 (8%) | 17 (5%) | ||

| Ever incarcerated | 1420 | 524 (37%) | 222 (62%) | 205 (29%) | 97 (28%) | <0.001 |

| Injection drug use history | 1396 | 439 (31%) | 225 (63%) | 132 (19%) | 83 (24%) | <0.001 |

| Involved in sex work | 1422 | <0.001 | ||||

| Yes | 82 (6%) | 36 (10%) | 30 (4%) | 16 (5%) | ||

| No | 1225 (86%) | 300 (84%) | 614 (86%) | 311 (88%) | ||

| Don’t’ know/Prefer not to answer | 115 (8%) | 20 (6%) | 69 (10%) | 26 (7%) | ||

| Clinical Characteristics | ||||||

| HCV co-infection | 1415 | 451 (32%) | 201 (56%) | 147 (21%) | 103 (29%) | <0.001 |

| HBV co-infection | 1405 | 119 (8%) | 48 (13%) | 35 (5%) | 36 (10%) | <0.001 |

| Median years living with HIV (IQR) | 1374 | 11 (6–17) | 12 (7–18) | 10 (5–15) | 13 (8–18) | <0.001 |

| Received HIV medical care in last year | 1420 | 1330 (94%) | 350 (98%) | 641 (90%) | 339 (96%) | <0.001 |

| Currently taking ART | 1415 | 1175 (83%) | 318 (89%) | 534 (75%) | 323 (92%) | <0.001 |

| Undetectable viral load (self-report)# | 1377 | <0.001 | ||||

| Undetectable (below 50 c/mL) | 1099 (80%) | 286 (82%) | 503 (74%) | 308 (88%) | ||

| Detectable (over 50 c/mL) | 204 (15%) | 51 (14%) | 122 (18%) | 31 (9%) | ||

| Don’t’ know/Prefer not to answer | 76 (5%) | 13 (4%) | 52 (8%) | 11 (3%) | ||

| Most recent CD4 (self-report) | 1382 | |||||

| <200 cells/mm3 | 75 (5%) | 30 (9%) | 22 (3%) | 23 (6%) | <0.001 | |

| 200–500 cells/mm3 | 386 (28%) | 114 (32%) | 173 (26%) | 99 (28%) | ||

| >500 cells/mm3 | 698 (51%) | 166 (47%) | 363 (53%) | 169 (48%) | ||

| Don’t’ know/Prefer not to answer | 223 (16%) | 42 (12%) | 122 (18%) | 59 (17%) | ||

IQR, interquartile range; LBQQ2S, lesbian, bisexual, queer, questioning, or two-spirit; HCV, hepatitis C; HBV, hepatitis B; ART, antiretroviral therapy.

*Other ethnicities included Chinese/Filipino/Japanese/Korean/Latin America/South Asian/Southeast Asian/Arab/West Asian/Multiple ethnicities.

#80% (1097/1377) of the overall cohort self-reported having an undetectable viral load; of the 1175/1415 women on ART, 87% (1025/1175) had an undetectable viral load.

Refusal data were collected qualitatively from PRAs during the baseline enrolment period. As per the PRAs, the reasons for not enrolling were infrequently due to refusal, but tended to be due to practical issues, personal health concerns, and difficulty re-connecting with a potential participant. In addition, some women who were screened were not enrolled due to stratified sampling targets to enroll women from under-represented priority populations.

As all variables were self-reported, attempts are underway to validate them compared to objective ones such as laboratory data. Thus far, we have compared the self-reported VLs with laboratory-confirmed VL data from participants in BC and found a high degree of validity of self-report [39]. BC is the only study province where linkage to clinical data is possible as the DTP database held at the BC Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS is a population-based registry capturing 100% of laboratory VL data in BC. The survey VL data were linked to the clinical DTP data for 99% of participants (n = 355 of 356); only one participant remained unlinked and 19 were excluded due to missing self-reported or lab data. The positive predictive value was 94 [95% confidence interval (CI): 90–96] and the negative predictive value was 80 (95% CI: 67–90).

Self-reported perceived women-centred HIV care (WCHC)

Of the 1330 women who received HIV medical care in the previous year (out of 1420 who responded), all reported on corresponding women-centred questions. Of these 1330 women, 61% (95% CI: 58%-63%) perceived that the care they received from their primary HIV doctor or clinic had been women-centred (Table 3).

Table 3. Perceived experience of women-centred HIV care of HIV doctor and clinic overall and by province of participants receiving HIV care (N = 1330).

| Total N | Total | British Columbia | Ontario | Quebec | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 1332 | N = 350 | N = 641 | N = 341 | |||

| Perceived WCHC of HIV Doctor and/or Clinic | ||||||

| Perceive care by HIV doctor to be women-centred | 1326 | 757 (57%) | 232 (67%) | 401 (63%) | 124 (37%) | <0.001 |

| Perceive care at HIV clinic to be women-centred | 1323 | 709 (53%) | 214 (61%) | 380 (59%) | 115 (34%) | <0.001 |

| Perceive care by HIV doctor and/or clinic to be women-centred | 1329 | 807 (61%) | 243 (69%) | 418 (65%) | 146 (43%) | <0.001 |

| Women-centred care is important to me | 1328 | 1065 (80%) | 289 (83%) | 524 (82%) | 252 (74%) | <0.001 |

| Satisfaction with care from HIV Doctor and Clinic | ||||||

| Satisfied with the care received from HIV doctor | 1329 | 1228 (92%) | 318 (91%) | 589 (92%) | 321 (95%) | 0.167 |

| Satisfied with the care received from HIV clinic | 1328 | 1226 (92%) | 315 (90%) | 591 (92%) | 320 (94%) | 0.160 |

| Care satisfaction depends on how women-centred it is | 1323 | 791 (59%) | 204 (58%) | 430 (67%) | 157 (46%) | <0.001 |

WCHC, women-centred HIV care.

Bivariate analyses of perceived WCHC by HIV doctor

Table 4 shows the bivariate analyses of demographic, clinical participant variables, and reporting of WCHC provided by the women’s HIV doctor. It should be noted that although 61% of the total sample perceived that their primary HIV care was women-centred, significant regional differences were reported. While 67% and 63% of women in BC and ON, respectively, reported perceived WCHC, only 37% women reported WCHC in QC. Also, women reporting WCHC were more likely to be younger; however, only by a median of two years.

Table 4. Bivariate analysis of characteristics by perceived women-centred HIV care from HIV doctor.

| Socio-Demographic Characteristics | N with responses | Perceived WCHC | Neutral WCHC |

No perceived WCHC | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1326 | N = 757 | N = 271 | N = 298 | |||

| n (%) | ||||||

| Province | 1326 | |||||

| British Columbia | 232 (67%) | 46 (13%) | 70 (20%) | <0.001 | ||

| Ontario | 401 (63%) | 129 (20%) | 111 (17%) | |||

| Quebec | 124 (37%) | 96 (28%) | 117 (35%) | |||

| Median Age [IQR] | 1326 | 43 (35–50) | 45 (37–53) | 45 (38–52) | 0.006 | |

| Age categories | 1326 | |||||

| <30 | 82 (71%) | 16 (14%) | 18 (15%) | 0.007 | ||

| 30–50 | 476 (58%) | 162 (20%) | 187 (22%) | |||

| >50 | 199 (52%) | 93 (24%) | 93 (24%) | |||

| Gender identity | 1326 | |||||

| Woman | 725 (57%) | 260 (20%) | 289 (23%) | 0.656 | ||

| Trans woman/Two-spirited/Queer/Other | 32 (62%) |

11 (21%) |

9 (17%) |

|||

| Sexual orientation | 1321 | |||||

| Heterosexual | 664 (57%) | 236 (20%) | 260 (23%) | 0.983 | ||

| LBQQ2S | 91 (57%) | 33 (20%) | 37 (23%) | |||

| Ethnicity | 1326 | |||||

| Indigenous–First Nations, Métis or Inuit | 177 (63%) | 41 (15%) | 62 (22%) | 0.022 | ||

| White/Caucasian | 217 (55%) | 94 (24%) | 80 (21%) | |||

| African/Caribbean/Black | 302 (54%) | 123 (22%) | 132 (24%) | |||

| Other# | 62 (62%) | 13 (13%) | 24 (25%) | |||

| Relationship Status | 1324 | 0.271 | ||||

| Partnered or married or in a relationship | 247 (59%) | 79 (19%) | 94 (22%) | |||

| Single | 372 (58%) | 130 (21%) | 136 (21%) | |||

| Separated / Divorced / Widowed / Other | 136 (51%) | 62 (23%) | 68 (26%) | |||

| Ever incarcerated | 1324 | |||||

| Yes | 255 (53%) | 90 (19%) | 134 (28%) | 0.001 | ||

| No | 502 (60%) | 180 (21%) | 163 (19%) | |||

| HIV Health Outcomes | ||||||

| Median years living with HIV (IQR) | 1285 | 11 (6–17) | 11 (6–16) | 12 (7–18) | 0.078 | |

| Categories | 1285 | |||||

| <5 years | 142 (60%) | 47 (20%) | 46 (20%) | 0.248 | ||

| 5–10 years | 195 (59%) | 73 (22%) | 65 (19%) | |||

| >10 | 397 (55%) | 142 (20%) | 178 (25%) | |||

| Hepatitis B | 1311 | |||||

| Yes | 57 (8%) | 25 (9%) | 31 (11%) | 0.274 | ||

| No | 693 (92%) | 243 (91%) | 262 (89%) | |||

| Hepatitis C | 1321 | |||||

| Yes | 226 (30%) | 79 (29%) | 116 (39%) | 0.012 | ||

| No | 527 (70%) | 191 (71%) | 182 (61%) | |||

| Currently taking ART | 1319 | |||||

| Currently taking ART | 639 (85%) | 251 (93%) | 256 (86%) | <0.001 | ||

| Not currently taking ART, but previously | 28 (4%) | 6 (2%) | 21 (7%) | |||

| Never on ART | 85 (11%) | 13 (5%) | 20 (7%) | |||

| Undetectable viral load (self-report) | 1316 | |||||

| Undetectable (below 50 c/mL) | 600 (80%) | 221 (82%) | 248 (84%) | 0.591 | ||

| Detectable (over 50 c/mL) | 109 (15%) | 34 (13%) | 37 (13%) | |||

| Don’t know/Prefer not to answer | 42 (5%) | 14 (5%) | 11 (3%) | |||

| Most recent CD4 count (self-report) | 1321 | 0.113 | ||||

| <200 cells/mm3 | 30 (4%) | 18 (7%) | 22 (7%) | |||

| 200–500 cells/mm3 | 223 (29%) | 71 (26%) | 76 (26%) | |||

| >500 cells/mm3 | 397 (53%) | 142 (52%) | 145 (49%) | |||

| Don’t know/Prefer not to answer | 105 (14%) | 40 (15%) | 53 (18%) | |||

WCHC, women-centred HIV care; IQR, interquartile range; LBQQ2S, lesbian, bisexual, queer, questioning, or two-spirit; HCV, hepatitis C; HBV, hepatitis B; ART, antiretroviral therapy.

#Other ethnicities included Chinese/Filipino/Japanese/Korean/Latin America/South Asian/Southeast Asian/Arab/West Asian/Multiple ethnicities

Test-retest reliability assessment

Test-rest reliability of the baseline questionnaire measures is presented in Table 5. The majority of the variables of interest scored either “substantial” or “almost perfect”, with some scoring “moderate”. As perceived WCHC by HIV doctor was more reliable than by clinic, we have chosen it to be our primary variable of interest (see Table 4).

Table 5. Test-retest reliability of key CHIWOS variables.

| Demographic Characteristics | Kappa*/ICC# | 95% CI of Kappa statistic or ICC | Strength of agreement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at interview | 1 | (1, 1) | Almost Perfect |

| Gender identity | 0.78 | (0.37, 1.00) | Substantial |

| Sexual orientation | 1 | (1, 1) | Almost Perfect |

| Ethnicity | 0.93 | (0.79, 1.00) | Almost Perfect |

| Ever incarcerated | 1 | (1, 1) | Almost Perfect |

| Injection drug use history (ever) | 0.96 | (0.88, 1.00) | Almost Perfect |

| Clinical characteristics | |||

| HCV co-infection | 0.93 | (0.79, 1.00) | Almost Perfect |

| HBV co-infection | 0.72 | (0.36, 1.00) | Substantial |

| Median years living with HIV | 0.93 | (0.86, 0.97) | NA |

| Received HIV medical care in last year | 1 | (1, 1) | Almost Perfect |

| Currently taking ART | 1 | (1, 1) | Almost Perfect |

| Undetectable viral load (self-report) | 1 | (1, 1) | Almost Perfect |

| Most recent CD4 (self-report) | 0.71 | (0.41, 1.00) | Substantial |

| Perceived women-centred care by HIV Doctor or Clinic | |||

| Perceive care by HIV doctor to be women-centred | 0.67 | (0.41, 0.93) | Substantial |

| Perceive care at HIV clinic to be women-centred | 0.6 | (0.32, 0.88) | Moderate |

| Women-centred care is important to me | 0.49 | (0.16, 0.81) | Moderate |

| Satisfied with the care received from HIV doctor | 0.8 | (0.69, 1.00) | Substantial |

| Satisfied with the care received from HIV clinic | 0.86 | (0.75, 1.00) | Almost Perfect |

| Care satisfaction depends on how women-centred it is | 0.66 | (0.40, 0.93) | Substantial |

CHIWOS, Canadian HIV Women’s Sexual and Reproductive Health Cohort Study; CI, confidence intervals; ICC, intraclass correlation coefficient

Note:

*Standard Kappas were calculated for nominal variables, weighted Kappas for ordinal variables and prevalence adjusted Kappa for rare observations.

#ICCs were calculated for continuous variables; strength of agreement not available.

Retention rates for visit 2

The overall retention rate for the study was 88% with 1252 participants (of 1422) having completed visit 2. The provincial retention rates were 84% (299 of 356) in BC, 89% (632 of 713) in ON and 91% (321 of 353) in QC. Of the 170 women who did not complete visit 2, 26 were deceased (12 in BC, 10 in ON and 4 in QC); 22 women withdrew from the study, including 7 who moved to another province and 3 who were palliative. 24 opted out of completing visit 2 (but are potentially interested in completing visit 3), including 5 women who were incarcerated; and we were unable to contact 98 (i.e., LTFU) (31 in BC, 54 in ON and 13 in QC) but outreach efforts will continue for Wave 3.

Discussion

CHIWOS has greatly contributed to the field of women and HIV by: 1) applying a CBR approach to a large national cohort study, 2) meaningfully applying the GIPA principles, and 3) enrolling harder-to-reach, and underserved communities of women with HIV in Canada. We enrolled 1422 diverse women with HIV from BC, ON and QC and have retained 1252 in our second study visit.

The primary objective of CHIWOS, which is to develop and test the concept of WCHC, is novel. As such, the study team had to develop a new scale used to determine perceived WCHC. Therefore, test-retest reliability was an important step before identifying the best variable for perceived WCHC. Interestingly, we only found moderate test-retest time reliability for perceived WHCH by the clinic. Also, care from a clinic is often provided by multiple people and care providers, which could complicate the conceptualization of WCHC from the clinic as a whole. The fact that these questions were created and being used for the first time may suggest that they were not well understood by the participants in relation to their clinic. Fortunately, the variable of WCHC by HIV doctor had substantially better reliability and was thus used as the primary variable of interest. The team intends to continue to explore the variable of WCHC by clinic to determine if our scale could be altered to better measure this variable.

Preliminary findings suggest some important considerations regarding our primary objective of exploring the concept of WCHC. The results of Visit 1 suggest that self-reported perception of WCHC varies by province with a significant difference between women in BC and ON and their peers in QC. The study team has given this finding substantial consideration to explore possible explanations. For participant in BC, one potential explanation is the highly integrated care that many women with HIV received at the Oak Tree Clinic in Vancouver. As the only centralized, women and family-focused care centre in Canada, the benefit of Oak Tree Clinic may be captured in this result. As for the high rate of self-reported WCHC in ON, the explanation for this finding remains unclear and will continue to be unpacked through the results of Visits 2 and 3, as will the low rates of self-reported WCHC in the province of QC.

Age also appears to be an important construct to evaluate in relation to WCHC with significantly more younger women reporting WCHC. The clinical attention to reproductive health in younger women with HIV may contribute to this finding. However, with an aging population of women with HIV, WCHC will need to broaden and include life-course issues such as menopause and other age-related co-morbidities. Finally, the results presented in Table 4 capture an interesting finding that ART-naïve participants were significantly more likely to report WCHC, the nuances of this finding are hard to interpret given the small sample size but will continue to be explored throughout the course of this longitudinal cohort.

Strengths and weaknesses

Having enrolled 1422 women with HIV, CHIWOS is the largest Canadian cohort study of women with HIV and will contribute data to our understanding of the current state of care and wellbeing of women with HIV in Canada. An acknowledged limitation of CHIWOS is that the cohort is not a random sample and may not be statistically representative of the wider population of women with HIV in Canada. Having also used purposive selection to enrol marginalized women, there is the potential for selection bias in those marginalized women who did enrol and thus findings may not be representative of all marginalized women with HIV in Canada. Nonetheless, CHIWOS has enrolled approximately 10% of all women with HIV in Canada and will provide important findings.

An additional concern is the potential for attrition given the relatively long period between visits and the risk of loss-to-follow-up of a harder-to-reach population. In an attempt to mitigate loss-to-follow-up, we have requested multiple means of contacting participants. We have also created a strong study presence online and via social media, and strong connections with clinics and community partners. This has not been an issue between the first and second data collection points.

Self-report may lead to social desirability bias, whereby participants provide answers to questions that they think the interviewer wants to hear, regardless of whether the answer is truthful or not. We have attempted to minimize this and other forms of reporting bias through PRA training, “smart survey” design with definitions for terms used, and the option to complete certain parts of the survey without the interviewer (i.e., sexual health and violence). While HIV clinical data may be poorly reported (e.g., VL), an initial analysis carried out in BC found excellent correlation with confirmed laboratory values [39]. This method of data capture also potentiates limitations in the reporting of clinical variables such as hepatitis C status, in that nuances like whether an infection has spontaneously cleared would not be captured. A general weakness of questionnaire-based studies is missing data. We attempted to mitigate missing data with PRA training and by electronically requiring an answer before moving to the next question. This means that it was impossible to skip a question and thus there is no missing data. “Don’t know” and “prefer not to answer” were choices for every question and can be used as needed. Thus far, overall results have not yielded a high frequency of these responses.

CHIWOS’s use of CBR from inception, prioritizing GIPA and the expertise of women with HIV is a strength of the study and fills a long-standing gap for gender transformative HIV research in Canada. The formative study phase also provided the advantage of knowledge creation using qualitative methods. Developing and finalizing the survey using an extensive process of community-based survey development enabled the needs of various community members and stakeholders to shape the sections and questions [34]. The longitudinal nature of CHIWOS enables the research team to adapt the survey to include questions about areas of emerging priority for women with HIV.

Conclusion

CHIWOS aims to be a CBR leader in explicating the concept of WCHC among diverse women with HIV living in Canada. It is achieving this aim through carrying out a large bilingual longitudinal cohort study of diverse women with HIV from across Canada, which is led by women with HIV, themselves, in partnership with academic researchers and clinicians. As a group, we are excited to further develop this model of care specific to women with HIV. CHIWOS also provides an opportunity to investigate many social, structural, behavioural, and clinical questions as they relate to diverse groups of women living with HIV across Canada, with results applicable to policy and programming in Canada, and around the world.

Additional resources

The CHIWOS investigators believe in open access of the operational resources to all interested in CBR and/or HIV women’s health and they can be found on our website: www.chiwos.ca.

Other specific resources available on our website are:

The full baseline questionnaire: (http://www.chiwos.ca/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/CHIWOS-May-13-2014-En.pdf).

The a priori strategy for ensuring and determining the validity and reliability: (http://www.chiwos.ca/wp-content/uploads/2012/04/CHIWOS-Questionnaire-Development-Description_Feb-11-2014.pdf).

Visit us online at:

We aim to hasten knowledge creation regarding improving the health and wellbeing of women with HIV. We welcome collaborations regarding research ideas and questions, using the CHIWOS data and KT initiatives; please contact us via our website if you have interest.

Supporting information

Explanation of harder-to-reach populations that were purposively recruited for the study.

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

Acknowledgments

The Canadian HIV Women’s Sexual and Reproductive Health Cohort Study (CHIWOS) Research Team would like to especially thank all of the women living with HIV who participate in the research and entrust CHIWOS with their experiences of HIV treatment, care, and support. We also thank the entire national team of Co-Investigators, Collaborators, and Peer Research Associates. We would like to acknowledge the three provincial Community Advisory Boards, and the national CHIWOS Indigenous Advisory Board, CHIWOS African, Caribbean and Black Advisory Board, and our partnering organizations for supporting the study. We also acknowledge the BC Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS for in kind data management and analytic support.

#CHIWOS RESEARCH TEAM: Rahma Abdul-Noor (Women’s College Research Institute), Aranka Anema (University of British Columbia), Jonathan Angel (Ottawa Hospital Research Institute), Jean-Guy Baril (Clinique du Quartier Latin), Fatimatou Barry (Women’s College Research Institute), Greta Bauer (University of Western Ontario), Kerrigan Beaver (Women’s College Research Institute), Denise Becker (Positive Living Society of British Columbia), Anita Benoit (Women’s College Research Institute), Jason Brophy (Children's Hospital of Eastern Ontario), Lori Brotto (University of British Columbia), Ann Burchell (Ontario HIV Treatment Network), Claudette Cardinal (Simon Fraser University), Allison Carlson (Women’s College Research Institute), Allison Carter (British Columbia Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS and Simon Fraser University), Angela Cescon (British Columbia Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS), Lynne Cioppa (Women’s College Research Institute), Jeffrey Cohen (Windsor Regional Hospital), Guillaume Colley (British Columbia Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS), Tracey Conway (Women’s College Research Institute), Curtis Cooper (Ottawa Hospital Research Institute), Jasmine Cotnam (Women’s College Research Institute), Janette Cousineau (Women’s College Research Institute), Janice Dayle, (McGill University Health Centre), Marisol Desbiens (Women’s College Research Institute), Hania Dubinsky, (McGill University Health Centre), Danièle Dubuc, (McGill University Health Centre), Janice Duddy (Pacific AIDS Network), Brenda Gagnier (Women’s College Research Institute), Jacqueline Gahagan (Dalhousie University), Claudine Gasingirwa (Women’s College Research Institute), Nada Gataric (British Columbia Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS), Saara Greene (McMaster University), Trevor Hart (Ryerson University), Catherine Hankins (UNAIDS), Bob Hogg (British Columbia Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS and Simon Fraser University), Terry Howard (Positive Living Society of British Columbia), Shazia Islam (Women’s College Research Institute), Evin Jones (Pacific AIDS Network),Charu Kaushic (McMaster University), Alexandria Keating (ViVA and Southern Gulf Islands AIDS Society), Logan Kennedy (Women’s College Research Institute), Mary Kestler (Oak Tree Clinic, BC Women’s Hospital and Health Centre), Maxime Kiboyogo (McGill University Health Centre), Marina Klein (McGill University Health Centre), Gladys Kwaramba (Women’s College Research Institute), Andrea Langlois (Pacific AIDS Network), Melanie Lee (Simon Fraser University), Rebecca Lee (CIHR Canadian HIV Trials Network), Lynne Leonard (University of Ottawa), Johanna Lewis (Women’s College Research Institute),Viviane Lima (British Columbia Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS), Elisa Lloyd-Smith (Providence Health Care), Carmen Logie (University of Toronto), Shari Margolese (Women’s College Research Institute), Carrie Martin (Native Women`s Shelter of Montreal), Renee Masching (Canadian Aboriginal AIDS Network), Lyne Massie, (Université du Québec à Montréal), Melissa Medjuck (Positive Women’s Network), Brigitte Ménard, (McGill University Health Centre), Cari Miller (Simon Fraser University), Deborah Money (Women’s Health Research Institute), Marvelous Muchenje (Women’s Health in Women’s Hands), Mary Mwalwanda (Women’s College Research Institute), Mary (Muthoni) Ndung'u (Women’s College Research Institute), Valerie Nicholson (Simon Fraser University), Illuminée Nzikwikiza (McGill University Health Centre), Kelly O’Brien (University of Toronto), Nadia O'Brien (McGill University Health Centre and McGill University), Gina Ogilvie (British Columbia Centre for Disease Control), Susanna Ogunnaike-Cooke (Public Health Agency of Canada), Joanne Otis (Université du Québec à Montréal), Ali Palmer (Simon Fraser University), Sophie Patterson (Simon Fraser University), Doris Peltier (Canadian Aboriginal AIDS Network), Yasmeen (Ashria) Persad (Women’s College Research Institute), Neora Pick (Oak Tree Clinic, BC Women’s Hospital and Health Centre), Alie Pierre, (McGill University Health Centre), Jeff Powis (Toronto East General Hospital), Karène Proulx-Boucher (McGill University Health Centre), Corinna Quan (Windsor Regional Hospital), Janet Raboud (Ontario HIV Treatment Network), Anita Rachlis (Sunnybrook Health Science Centre), Edward Ralph (St. Joseph’s Health Care), Stephanie Rawson, (Simon Fraser University, BC), Eric Roth (University of Victoria), Danielle Rouleau (Centre Hospitalier de l’Université de Montréal), Sean Rourke (Ontario HIV Treatment Network), Sergio Rueda (Centre for Addiction and Metal Health), Mercy Saavedra (Women’s College Research Institute), Kate Salters (Simon Fraser University), Margarite Sanchez (ViVA and Southern Gulf Islands AIDS Society), Roger Sandre (Haven Clinic), Jacquie Sas (CIHR Canadian HIV Trials Network), Paul Sereda (British Columbia Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS), Fiona Smaill (McMaster University), Stephanie Smith (Women’s College Research Institute), Marcie Summers (Positive Women’s Network), Tsitsi Tigere (Women’s College Research Institute), Wangari Tharao (Women’s Health in Women’s Hands), Jamie Thomas-Pavanel (Women’s College Research Institute), Christina Tom (Simon Fraser University, BC), Cécile Tremblay (Centre Hospitalier de l’Université de Montréal), Benoit Trottier (Clinique l’Actuel), Sylvie Trottier (Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Québec), Christos Tsoukas (McGill University Health Centre), Anne Wagner (Ryerson University), Sharon Walmsley (Toronto General Research Institute), Kath Webster (Simon Fraser University), Wendy Wobeser (Kingston University), Jessica Yee (Native Youth Sexual Health Network), Mark Yudin (St-Michael’s Hospital), Wendy Zhang (British Columbia Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS). All other CHIWOS Research Team Members who wish to remain anonymous.

Data Availability

Data are available from the Women's College Research Institute Women and HIV Research Program Data Access Coordinator for researchers and students who meet the criteria for access to confidential data. The current Data Access Coordinator is Angela Underhill and she can be reached at angela.underhill@wchospital.ca. The criteria for access to the confidential data includes 1) being added as a CHIWOS researcher or student to the research ethics board (REB) application and 2) signing a CHIWOS Data Sharing and Collaboration Agreement. The de-identified data set cannot be publicly shared at this point as we do not have community or REB approval to do so. Co-authorship is a requirement for data access as per the CHIWOS authorship policy (www.chiwos.ca) which includes the requirement that the ICMJE authorship criteria be met by all authors.

Funding Statement

This work was funded by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Operating Grant (grant# MOP-111041), the CIHR Canadian HIV Trials Network (CTN 262), the Ontario HIV Treatment Network, and the Academic Health Science Centres (AHSC) Alternative Funding Plans (AFP) Innovation Fund. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.UNAIDS [internet]. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2011. Global AIDS response progress reporting 2014; 2013 [cited 2016 Feb 29]. Available from http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/GARPR_2014_guidelines_en_0.pdf

- 2.Oguntibeju O. Quality of life of people living with HIV and AIDS and antiretroviral therapy. HIV AIDS. 2012. August; 117–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Patterson S, Cescon A, Samji H, Chan K, Zhang W, Raboud J, et al. Life expectancy of HIV-positive individuals on combination antiretroviral therapy in Canada. BMC Infect Dis. 2015. July; 274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.U.S. Department of Health and Human Safety [internet]. Washington (DC): Office of Women’s Health; [date unknown]. HIV/AIDS; 2011 July 01 [cited 2016 March 02]. Available from: http://www.womenshealth.gov/hiv-aids/living-with-hiv-aids/barriers-to-care-for-hiv-aids.html#pubs.

- 5.Carter A, Min EJ, Chau W, Lima VD, Kestler M, Pick N, et al. Gender inequities in quality of care among HIV-positive individuals initiating antiretroviral treatment in British Columbia, Canada (2000–2010). Plos ONE [Internet]. 2014. March [cited 2016 March 02]. Available from http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0092334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Public Health Agency of Canada [internet]. [Place unknown]; Summary: Estimates of HIV incidence, prevalence and proportion undiagnosed in Canada, 2014; 2015 Nov 30 [cited 2017 June 23]. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/diseases-conditions/summary-estimates-hiv-incidence-prevalence-proportion-undiagnosed-canada-2014.html.

- 7.Raikhel E. Somatmatosphere [interent]. [Place unknown]: Eugene Raikhel; [date unknown]. Epistemological frameworks and the ‘feminization’ of the HIV/AIDS pandemic; 2009 Nov 12 [cited 2016 March 2]. Available from: http://somatosphere.net/2009/11/feminization-of-hivaids-epidemic.html.

- 8.Dworkin SL, Ehrhardt AA. Going beyond “ABC” to include “GEM”: Critical reflections on progress in the HIV/AIDS epidemic. Am Journal Public Health. 2007. January; 97:13–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wingood GM. Feminization of the HIV epidemic in the United States: Major research findings and future research needs. J Urban Health. 2003. September;80: iii67–iii76. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jtg084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cornell M, Schomaker M, Garone DB, et al. Gender differences in survival among adult patients starting antiretroviral therapy in South Africa: a multicentre cohort study. Plos ONE [Internet]. 2012. September [cited 2016 March 02]. Available from http://journals.plos.org/plosmedicine/article?id=10.1371/journal.pmed.1001304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Druyts E, Dybul M, Kanters S, Nachega J, Birungi J, Ford N, et al. Male sex and the risk of mortality among individuals enrolled in antiretroviral therapy programs in Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS. 2013. January; 27: 417–25. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328359b89b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mills EJ, Bakanda C, Birungi J, Chan K, Hogg RS, Ford N et al. Male gender predicts mortality in a large cohort of patients receiving antiretroviral therapy in Uganda. J Int AIDS Soc. 2011. November; 14: 52 doi: 10.1186/1758-2652-14-52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bowleg L. When black + lesbian + woman: The methodological challenges of qualitative and quantitative intersectionality research. Sex Roles. 2008. March; 59:312–325. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hankivsky O, Reid C, Cormier R, Varcoe C, Clark N, Benoit C et al. Exploring the promises of intersectionality for advancing women's health research. Int J Equity Health. 2010. February; 9: 5 doi: 10.1186/1475-9276-9-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ontario HIV Treatment Network [internet]. Toronto; Intersectionality in HIV and other health-related research; 2013 June [cited 2016 March 02]. Available from: http://www.biomedcentral.com/submissions/preparing-your-manuscript-and-supporting-information.

- 16.Hirschhorn LR, McInnes K, Landon BE, Wilson IB, Ding L, Marsden PV, et al. Gender differences in quality of HIV care in Ryan White CARE Act-funded clinics. Womens Health Issues. 2006. May-Jun;16:104–112. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2006.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mrus JM, Williams PL, Tsevat J, Cohn SE, Wu Aw. Gender differences in health-related quality of life in patients with HIV/AIDS. Qual Life Res. 2005. March;14: 479–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carter A, Greene S, Nicholson V, O'Brien N, Sanchez M, de Pokomandy A, et al. Breaking the glass ceiling: Increasing the meaningful involvement of women living with HIV/AIDS (MIWA) in the design and delivery of HIV/AIDS services. Health Care Women Int. 2014;36: 936–964. doi: 10.1080/07399332.2014.954703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.d'Arminio Monforte A, González L, Haberl A, Sherr L, Ssanyu-Sseruma W, Walmsley SL. Better mind the gap: addressing the shortage of HIV-positive women in clinical trials. AIDS. 2010. May;24:1091–1094. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283390db3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Walmsley SL. HIV-positive women in clinical trials: A gap in the facts. HIV Treatment Update. 2010. June:197. [Google Scholar]

- 21.World Health Organization [internet]. [Place unknown]; Consolidated guideline on sexual and reproductive health and rights of women living with HIV; 2017 [cited 2017 June 23]. Available from http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/gender_rights/srhr-women-hiv/en/ [PubMed]

- 22.CHIWOS [internet]. [Place unknown]; The Canadian HIV Women’s Sexual and Reproductive Health Cohort Study; 2013 [cited 2016 March 02]. Available from http://www.chiwos.ca.

- 23.Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB. Review of community-based research: assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annu Rev Public Health. 1998;19:173–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.UNAIDS [internet]. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2011. The greater involvement of people living with HIV (GIPA); 2007 [cited 2016 March 02]. Available from: http://data.unaids.org/pub/BriefingNote/2007/jc1299_policy_brief_gipa.pdf.

- 25.DeReus L, Few AL, Blume LB. Multicultural and critical race feminisms: theorizing families in the 3rd Wave. Thound Oaks Ca: Sage; c2005. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bredstrom A. Intersectionality: A Challenge for Feminist HIV/AIDS Research. Eur J Womens Stud. 2006. August;13:229–43. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Loutfy M, Greene S, Kennedy VL, et al. Establishing the Canadian HIV Women’s Sexual and Reproductive Health Cohort Study (CHIWOS): operationalizing community-based research in a large national quantitative study. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2016. August; 16: 101 doi: 10.1186/s12874-016-0190-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Remis RS, Lui J. [internet]. Toronto: Report on HIV/AIDS in Ontario 2011; 2013 August [cited 2017 June 23]. Available from: http://www.ohemu.utoronto.ca/doc/PHERO2011_report_preliminary.pdf

- 29.BC Centre for Disease Control. [internet]. Vancouver: [Data request: Females testing newly positive for HIV in BC by Health Service Delivery Area, 1994–2009]. Unpublished raw data."; 2011 [cited 2017 July 11]. Available from: http://libguides.lib.msu.edu/c.php?g=96245&p=626239:

- 30.Institut national de santé publique Québec. [internet]. Surveillance des infections transmissibles sexuellement et par le sang; 2012 September [cited 2017 July 11]. Available from: https://www.inspq.qc.ca/pdf/publications/1579_ProgSurvInfectionVIHQc_CasCumul2002-2011.pdf

- 31.O’Brien N, S Greene S, A Carter A, Lewis J, Nicholson V, Rawson S et al. Envisioning Women-Centred HIV Care: Perspectives from Women Living with HIV in Canada. Poster session presented at: 6th International Workshop on HIV & Women. 2016 February 20–21; Boston, Massachusetts.

- 32.Gray K, Tharao W, Calzavara L [internet]. Toronto Canada: [date unknown]. Conducting research with hard-to-reach populations: Lessons learned from the East Africa health study in Toronto [EAST]; 2012 February [cited 2016 March 02]. Available from http://www.srchiv.ca/uploads/media/Lessons%20Learned%20from%20East%20African%20Health%20Study%20in%20Toronto%20(EAST).pdf.

- 33.CHIWOS [internet]. [Place unknown]; CHIWOS paper questionnaire; 2014 May 13 [cited 2016 March 02]. Available from: http://www.chiwos.ca/wp- content/uploads/2014/08/CHIWOS-May-13-2014-En.pdf.

- 34.Abelsohn K, Benoit AC, Conway T, Cioppa L, Smith S, Kwaramba G. “Hear(ing) new voices”: Peer reflections from community based survey development with women living with HIV. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2015. Winter;9: 561–9. 35. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2015.0079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Burns K, Duffett M, Kho M, et al. A guide to the design and conduct of self administered survey of clinicians. CMAJ. 2008;179: 245–52. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.080372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ontario HIV Treatment Network [internet]. Toronto; [date unknown]. The Ontario HIV Treatment Network Cohort Study 2014 [cited 2016 March 2]. Available from: http://ohtncohortstudy.ca.

- 37.Palmer AK, Yip B, Milan D, Cooper C, Hosein S, Loutfy M. Cohort Profile: The Canadian Observational Cohort (CANOC) Collaboration. Int J Epidemiol. 2011. February;40:25–32. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyp393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.CANOC: Canadian observation cohort collaboration [internet]. [Place unknown]. CANOC 2008 [cited 2016 March 02]. Available from: http://www.canoc.ca.

- 39.Carter A, de Pokomandy A, Loutfy M, Ding E, Sereda P, Webster K et al. Validating a self-report measure of HIV viral suppression: an analysis of linked questionnaire and clinical data from the Canadian HIV Women’s Sexual and Reproductive Health Cohort Study. BMC Research Notes. 2017. March doi: 10.1186/s13104-017-2453-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Explanation of harder-to-reach populations that were purposively recruited for the study.

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available from the Women's College Research Institute Women and HIV Research Program Data Access Coordinator for researchers and students who meet the criteria for access to confidential data. The current Data Access Coordinator is Angela Underhill and she can be reached at angela.underhill@wchospital.ca. The criteria for access to the confidential data includes 1) being added as a CHIWOS researcher or student to the research ethics board (REB) application and 2) signing a CHIWOS Data Sharing and Collaboration Agreement. The de-identified data set cannot be publicly shared at this point as we do not have community or REB approval to do so. Co-authorship is a requirement for data access as per the CHIWOS authorship policy (www.chiwos.ca) which includes the requirement that the ICMJE authorship criteria be met by all authors.