Abstract

Efficacy of statin-based therapies in reducing cardiovascular mortality in individuals with CKD seems to diminish as eGFR declines. The strongest evidence supporting the cardiovascular benefit of statins in individuals with CKD was shown with ezetimibe plus simvastatin versus placebo. However, whether combination therapy or statin alone resulted in cardiovascular benefit is uncertain. Therefore, we estimated GFR in 18,015 individuals from the IMPROVE-IT (ezetimibe plus simvastatin versus simvastatin alone in individuals with cardiovascular disease and creatinine clearance >30 ml/min) and examined post hoc the relationship of eGFR with end points across treatment arms. For the primary end point of cardiovascular death, major coronary event, or nonfatal stroke, the relative risk reduction of combination therapy compared with monotherapy differed by eGFR (P=0.04). The difference in treatment effect was observed at eGFR≤75 ml/min per 1.73 m2 and most apparent at levels ≤60 ml/min per 1.73 m2. Compared with individuals receiving monotherapy, individuals receiving combination therapy with a baseline eGFR of 60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 experienced a 12% risk reduction (hazard ratio [HR], 0.88; 95% confidence interval [95% CI], 0.82 to 0.95); those with a baseline eGFR of 45 ml/min per 1.73 m2 had a 13% risk reduction (HR, 0.87; 95% CI, 0.78 to 0.98). In stabilized individuals within 10 days of acute coronary syndrome, combination therapy seemed to be more effective than monotherapy in individuals with moderately reduced eGFR (30–60 ml/min per 1.73 m2). Further studies examining potential benefits of combination lipid-lowering therapy in individuals with CKD are needed.

Keywords: lipids, statins, chronic kidney disease, cardiovascular

Individuals with CKD are at increased risk for death from cardiovascular disease.1 Kidney function, as measured by eGFR, is an independent and strong predictor of this risk.1–3 In many populations, hepatic hydroxymethyl glutaryl–CoA reductase inhibitors (statins) are important therapies for both primary and secondary cardiovascular risk mitigation; however, for individuals with reduced eGFR, the optimal lipid-lowering therapies for reducing cardiovascular risk remain unclear.4–12

A meta-analysis of 14 statin trials assessing the effects of LDL cholesterol reduction in individuals with impaired kidney function found that the risk of first major cardiovascular event was reduced proportional to the reduction in LDL cholesterol, with a trend toward decreased relative benefits as eGFR declined.13 Among individuals with CKD, the strongest single trial supporting cardiovascular risk–lowering benefit for statin therapies was shown with ezetimibe plus simvastatin compared with placebo in the Study of Heart and Renal Protection (SHARP).14 Largely on the basis of findings from this study, current guidelines recommend the use of statin monotherapy or ezetimibe plus statin for nearly all individuals ≥50 years old with reduced eGFR (<60 ml/min per 1.73 m2).15,16 However, in the setting of nondialysis-dependent CKD, whether the use of combination lipid-lowering therapy (ezetimibe plus statin) confers additional cardiovascular benefit beyond the use of a statin alone is unknown.

The Improved Reduction of Outcomes: Vytorin Efficacy International Trial (IMPROVE-IT) was a multicountry, double-blind, randomized, controlled study evaluating the effect of ezetimibe combined with simvastatin compared with simvastatin alone in individuals with known cardiovascular disease and baseline LDL cholesterol values <125 mg/dl.17 The trial showed an additional benefit of combination lipid-lowering therapy in preventing cardiovascular outcomes. We hypothesized that the treatment effect would vary by level of kidney function as estimated by eGFR, such that the additional cardiovascular benefit of combination therapy would be greater at reduced levels of eGFR.

Results

Baseline Characteristics

We were able to assess eGFR at the time of the qualifying event for 18,015 (99.3%) of 18,144 individuals enrolled in IMPROVE-IT (Supplemental Figure 1), including 9011 who received simvastatin monotherapy and 9004 who received combination therapy with ezetimibe plus simvastatin. A total of 3761 individuals had an eGFR<60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 at baseline, of whom 1018 had an eGFR<45 ml/min per 1.73 m2. Despite the exclusion criterion of creatinine clearance (CrCl) <30 ml/min, 126 individuals had an eGFR<30 ml/min per 1.73 m2, which was likely due to the difference in assessing kidney function by eGFR rather than CrCl.

Individuals with eGFR<60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 were older, were more frequently women, were less frequently current smokers, and had more comorbidities, including diabetes, hypertension, and prior cardiovascular events or interventions (Table 1). In both treatment arms, individuals with reduced eGFR had a shorter median time of overall and on-treatment follow-up compared with those with higher levels of eGFR. The cumulative incidence of study dropout over the 7-year study period was similar by level of eGFR and treatment arm (Supplemental Figure 2, Supplemental Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study population by eGFR (milliliters per minute per 1.73 m2) category at time of qualifying event

| Baseline Variable | eGFR<45, n=1018 | eGFR=45–59, n=2743 | eGFR=60–89, n=9572 | eGFR≥90, n=4682 | Total, n=18,015 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | 73.3 (8.96) | 69.9 (9.22) | 64.5 (9.20) | 58.0 (7.09) | 64.1 (9.76) |

| Men (%) | 602 (59.1) | 1885 (68.7) | 7367 (77.0) | 3776 (80.6) | 13,630 (75.7) |

| White (%) | 851 (83.6) | 2286 (83.3) | 8091 (84.5) | 3883 (82.9) | 15,111 (83.9) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 28.9 (5.54) | 28.3 (5.09) | 28.2 (5.12) | 28.3 (5.40) | 28.3 (5.22) |

| Current smoker (%) | 159 (15.6) | 591 (21.5) | 2905 (30.4) | 2280 (48.7) | 5935 (33.0) |

| Medical history | |||||

| Hypertension (%) | 856 (84.1) | 2015 (73.5) | 5719 (59.7) | 2483 (53.0) | 11,073 (61.5) |

| Diabetes (%) | 443 (43.5) | 830 (30.3) | 2365 (24.7) | 1264 (27.0) | 4902 (27.2) |

| Prior MI (%) | 311 (30.6) | 727 (26.5) | 1967 (20.6) | 775 (16.6) | 3780 (21.0) |

| Prior PCI (%) | 137 (25.8) | 317 (23.3) | 912 (19.2) | 418 (17.6) | 3537 (19.6) |

| Prior CABG (%) | 203 (19.9) | 365 (13.3) | 864 (9.0) | 243 (5.2) | 1675 (9.3) |

| Prior AF (%) | 125 (12.3) | 242 (8.8) | 452 (4.7) | 123 (2.6) | 942 (5.2) |

| Creatinine, mg/dl | 1.65 (0.36) | 1.26 (0.17) | 1.00 (0.14) | 0.78 (0.12) | 1.02 (0.27) |

| eGFR | 37.6 (5.82) | 53.6 (4.19) | 75.2 (8.44) | 98.7 (7.73) | 75.9 (18.8) |

| CrCl, ml/min | 44.1 (12.1) | 60.9 (15.1) | 85.4 (21.1) | 122.6 (38.1) | 89.0 (34.5) |

| SBP, mmHg | 129.8 (19.4) | 126.5 (18.7) | 125.1 (18.4) | 123.1 (17.8) | 125.0 (18.4) |

| DBP, mmHg | 72.0 (12.1) | 72.1 (11.1) | 73.2 (11.2) | 73.4 (11.1) | 73.0 (11.2) |

| LDL-C, mg/dl | 88.4 (21.1) | 90.8 (20.3) | 94.1 (19.9) | 96.1 (19.4) | 93.8 (20.0) |

| HDL-C, mg/dl | 41.4 (13.5) | 42.0 (13.5) | 42.5 (13.1) | 41.7 (13.0) | 42.1 (13.1) |

| TGs, mg/dl | 136.6 (74.1) | 135.0 (72.9) | 135.3 (74.5) | 143.6 (79.5) | 137.5 (75.7) |

| Medications before qualifying event (%) | |||||

| β-Blockers | 912 (89.6) | 2522 (92.0) | 8783 (91.8) | 4341 (92.7) | 16,558 (91.9) |

| ACEi or ARB | 681 (67.0) | 1934 (70.6) | 6755 (70.6) | 3288 (70.3) | 12,658 (70.3) |

| Statins | 454 (44.6) | 1208 (44.1) | 3253 (34.0) | 1289 (27.6) | 6204 (34.5) |

| Follow-up, mo | |||||

| Overall | |||||

| Median | 55.6 | 66.7 | 72.4 | 73.7 | 71.4 |

| Interquartile range | 30.5–78.9 | 49.0–85.0 | 52.0–86.0 | 53.2–85.9 | 51.4–85.7 |

| On Treatment | |||||

| Median | 32.7 | 50.2 | 54.7 | 55.2 | 53.1 |

| Interquartile range | 6.0–61.0 | 13.0–76.8 | 19.4–80.6 | 21.1–80.3 | 17.1–79.2 |

Data are presented as n (%) or mean (SD) unless otherwise defined. BMI, body mass index; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; AF, atrial fibrillation; SBP, systolic BP; DBP, diastolic BP; LDL-C, LDL cholesterol; HDL-C, HDL cholesterol; TG, triglyceride; ACEi, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker.

Lipid Data

Within each eGFR category, individuals in the combination therapy arm experienced a greater mean change in LDL cholesterol (P=0.01), triglycerides (P<0.001), and HDL cholesterol (P=0.03) compared with individuals in the monotherapy arm at 1 year of follow-up (Table 2). However, within each treatment arm, individuals experienced similar changes in mean LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, and triglycerides across all levels of eGFR (P>0.05 for all).

Table 2.

Lipid profiles by eGFR (milliliters per minute per 1.73 m2) and treatment arm (n=18,015)

| Lipid Profile | eGFR<45, n=1018 | eGFR=45–59, n=2743 | eGFR=60–89, n=9572 | eGFR≥90, n=4682 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S Alone, n=532 | Ez/S, n=486 | S Alone, n=1359 | Ez/S, n=1384 | S Alone, n=4748 | Ez/S, n=4824 | S Alone, n=2372 | Ez/S, n=2310 | |

| LDL-C, mg/dl | ||||||||

| Baseline, N | 526 | 475 | 1337 | 1347 | 4672 | 4734 | 2328 | 2276 |

| Mean baseline (SD) | 78.1 (25.0) | 77.6 (23.4) | 79.4 (23.5) | 78.2 (23.6) | 81.0 (23.3) | 81.3 (23.5) | 84.0 (24.1) | 82.5 (24.1) |

| Change from baseline at year 1, N | 331 | 311 | 981 | 1007 | 3659 | 3656 | 1852 | 1760 |

| Mean change from baseline at year 1 (SD) | −9.9 (27.5) | −26.5 (28) | −9.7 (27.5) | −27.4 (28.2) | −11.8 (26.2) | −27.9 (27.6) | −12.1 (26.3) | −27.9 (27.1) |

| Absolute mean difference in change from baseline between treatment arms | 16.6 | 17.7 | 16.1 | 15.8 | ||||

| HDL-C, mg/dl | ||||||||

| Baseline, N | 526 | 476 | 1339 | 1348 | 4672 | 4737 | 2329 | 2276 |

| Mean baseline (SD) | 41.7 (12.3) | 40.5 (10.9) | 41.1 (11.4) | 41.4 (11.2) | 41.7 (11.3) | 41.6 (10.9) | 40.4 (10.7) | 40.5 (10.9) |

| Change from baseline at year 1, N | 331 | 312 | 983 | 1009 | 3659 | 3663 | 1854 | 1762 |

| Mean change from baseline at year 1 (SD) | 5.9 (11.2) | 8.2 (9.9) | 6.6 (9.0) | 7.3 (9.2) | 7.0 (9.1) | 7.8 (9.0) | 7.4 (9.7) | 7.7 (9.7) |

| Triglycerides mg/dl | ||||||||

| Baseline, N | 526 | 476 | 1339 | 1348 | 4676 | 4741 | 2331 | 2277 |

| Mean baseline (SD) | 146.0 (64.3) | 150.7 (69.1) | 141.4 (63.9) | 142.3 (64.5) | 137.8 (59.7) | 139.0 (64.3) | 144.7 (69.6) | 142.2 (63.9) |

| Change from baseline at year 1, N | 332 | 313 | 985 | 1009 | 3666 | 3669 | 1856 | 1766 |

| Mean change from baseline at year 1 (SD) | 2.5 (88.9) | −21.2 (72.2) | −2.6 (63.5) | −21.8 (63.1) | −4.6 (78.9) | −21.1 (71.1) | −2.2 (86.1) | −20.1 (72.1) |

S, simvastatin; Ez/S, ezetimibe plus simvastatin; LDL-C, LDL cholesterol; HDL-C, HDL cholesterol.

Relationship between eGFR, Treatment Efficacy, and the Primary End Point

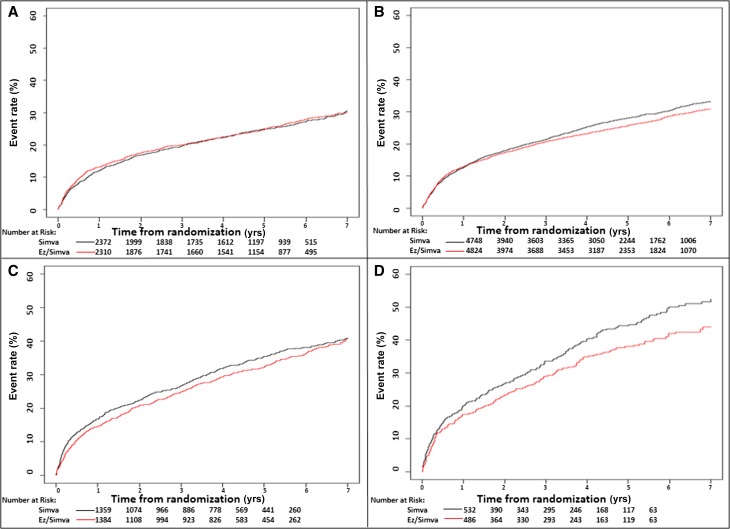

Within each treatment arm, the incidence of the primary composite end point was greater at lower eGFR levels, but at eGFR<90 ml/min per 1.73 m2, individuals in the combination therapy arm experienced comparatively fewer event rates across all of the prespecified eGFR categories (Figure 1, Table 3). We observed similar trends among the secondary and tertiary study outcomes, including all-cause mortality, major coronary event, or nonfatal stroke; death from cardiovascular disease, nonfatal myocardial infarction (MI), or nonfatal stroke; and all-cause mortality (Supplemental Table 2).

Figure 1.

Relationship between level of eGFR and event rate for primary composite end point of death from cardiovascular disease, a major coronary event, or nonfatal stroke. Kaplan-Meier curves show the primary composite end point during the 7-year study period stratified by (A) eGFR≥90 ml/min per 1.73 m2, (B) eGFR=60–89 ml/min per 1.73 m2, (C) eGFR=45–59 ml/min per 1.73 m2, and (D) eGFR<45 ml/min per 1.73 m2. EzSimva, ezetimibe and simvastatin; Simva, simvastatin.

Table 3.

Absolute incidence rates and numbers needed to treat (NNT) for the primary composite end point (death from cardiovascular disease, a major coronary event, or nonfatal stroke) by level of eGFR

| Level of eGFR | Simvastatin Monotherapy (%), n=9011 | Ezetimibe Plus Simvastatin (%), n=9004 | NNT (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall, ml/min per 1.73 m2 | 2742 (34.7) | 2572 (32.7) | |

| eGFR<45, ml/min per 1.73 m2 | 231/532 (43.4) | 180/486 (37.0) | 12 (6 to 105) |

| eGFR=45–59, ml/min per 1.73 m2 | 487/1359 (35.8) | 475/1384 (34.3) | 1000 (−24,∞,23) |

| eGFR=60–89, ml/min per 1.73 m2 | 1383/4748 (29.1) | 1303/4824 (27.0) | 42 (22 to 379) |

| eGFR≥90, ml/min per 1.73 m2 | 627/2372 (26.4) | 602/2310 (26.1) | 167 (−41,∞,27) |

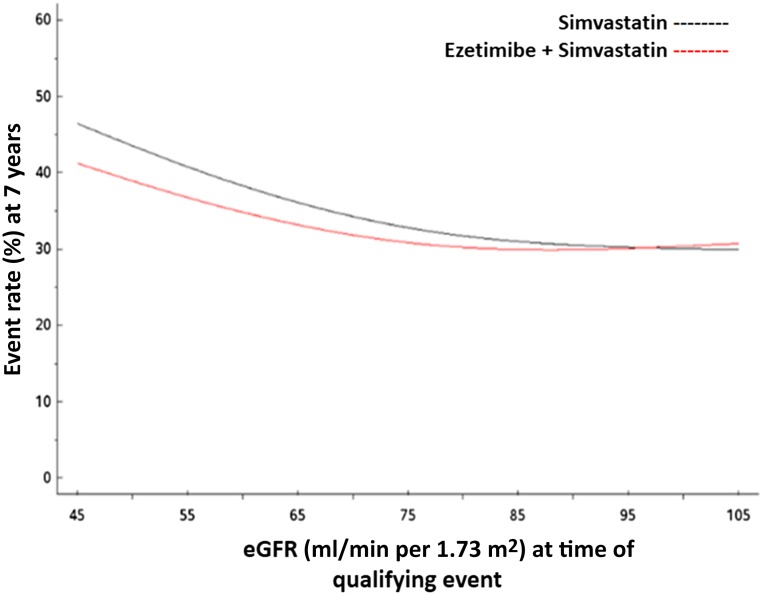

The absolute benefit seemed greatest (number needed to treat [NNT] =12; 95% confidence interval [95% CI], 6 to 105) among individuals with the most substantial reductions in eGFR (<45 ml/min per 1.73 m2). In both unadjusted and adjusted Cox proportional hazards models, we observed a difference in the effect of treatment on the occurrence of the primary end point across levels of kidney function (Figure 2). In the adjusted model, the difference in treatment was statistically significant (overall interaction P=0.04) and appeared as the baseline eGFR declined to ≤75 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (Table 4). The difference in treatment was most pronounced at eGFR levels ≤60 ml/min per 1.73 m2. At an eGFR of 60 ml/min per 1.73 m2, individuals in the combination therapy arm compared with individuals in the monotherapy arm had a 12% relative risk reduction (hazard ratio [HR], 0.88; 95% CI, 0.82 to 0.95) for the primary composite end point; at a baseline eGFR of 45 ml/min per 1.73 m2, they had a 13% relative risk reduction (HR, 0.87; 95% CI, 0.78 to 0.98) for the primary composite end point.

Figure 2.

Effect of treatment on the occurrence of the primary end point across levels of kidney function. Cox proportional hazards model shows predicted event rates for the primary end point of death from cardiovascular disease, a major coronary event, or nonfatal stroke by level of eGFR.

Table 4.

Adjusted HRs comparing combination therapy with monotherapy for each end point at prespecified eGFR values

| End Point | HRa (95% CI) | Interaction P Valuea |

|---|---|---|

| Primary composite end point | ||

| Death from cardiovascular disease, major coronary event, or nonfatal stroke, ml/min per 1.73 m2 | 0.04 | |

| eGFR=45 | 0.87 (0.78 to 0.98) | |

| eGFR=60 | 0.88 (0.82 to 0.95) | |

| eGFR=75 | 0.91 (0.84 to 0.99) | |

| eGFR=90 | 0.99 (0.92 to 1.06) | |

| eGFR=105 | 1.08 (0.95 to 1.22) | |

| Overall effect | 0.94 (0.89 to 0.99) | |

| Secondary composite end points | ||

| All-cause mortality, major coronary event, or nonfatal stroke, ml/min per 1.73 m2 | 0.25 | |

| eGFR=45 | 0.90 (0.82 to 0.99) | |

| eGFR=60 | 0.92 (0.86 to 0.98) | |

| eGFR=75 | 0.95 (0.88 to 1.02) | |

| eGFR=90 | 0.98 (0.92 to 1.05) | |

| eGFR=105 | 1.02 (0.91 to 1.15) | |

| Overall effect | 0.95 (0.90 to 1.00) | |

| Death from cardiovascular disease, nonfatal MI, or nonfatal stroke, ml/min per 1.73 m2 | 0.07 | |

| eGFR=45 | 0.79 (0.70 to 0.90) | |

| eGFR=60 | 0.87 (0.79 to 0.94) | |

| eGFR=75 | 0.93 (0.84 to 1.03) | |

| eGFR=90 | 0.96 (0.87 to 1.05) | |

| eGFR=105 | 0.99 (0.83 to 1.17) | |

| Overall effect | 0.95 (0.90 to 1.00) | |

| Tertiary composite end point | ||

| All-cause mortality, ml/min per 1.73 m2 | 0.06 | |

| eGFR=45 | 0.92 (0.81 to 1.05) | |

| eGFR=60 | 1.05 (0.95 to 1.16) | |

| eGFR=75 | 1.12 (0.99 to 1.25) | |

| eGFR=90 | 1.01 (0.89 to 1.14) | |

| eGFR=105 | 0.91 (0.73 to 1.13) | |

| Overall effect | 0.99 (0.91 to 1.07) |

Adjusted for age, sex, race, weight, family history of coronary artery disease, diabetes, hypertension, smoking status, history of angina, prior MI, prior percutaneous coronary intervention, prior coronary artery bypass graft, history of peripheral artery disease, prior stroke, prior congestive heart failure, percutaneous coronary intervention or catheterization at qualifying event, prior atrial fibrillation, baseline Killip class, systolic BP, heart rate, baseline medications (β-blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers, aspirin, or statin therapy), geographic region, qualifying event diagnosis, electrocardiogram changes (transient ST elevation, ST depression, or T-wave changes), hemoglobin at randomization, and baseline LDL, HDL, and triglycerides at time of qualifying event.

Relationship between eGFR, Treatment Efficacy, and the Secondary and Tertiary End Points

We observed no significant overall difference in the effect of treatment across levels of eGFR with respect to the secondary and tertiary composite end points (overall interaction P>0.05 for all) (Table 4). In those with reduced eGFR (≤60 ml/min per 1.73 m2), there was a nonsignificant risk reduction from combination therapy with respect to (1) all-cause mortality, major coronary events, or nonfatal stroke; and (2) death from cardiovascular disease, nonfatal MI, or nonfatal stroke (Supplemental Figure 3).

Safety

We observed few adverse events in either treatment arm across all levels of eGFR (Table 5). There was a trend toward increasing rates of adverse events in both treatment arms at lower eGFR levels, but individuals with the most severe reductions in eGFR (<45 ml/min per 1.73 m2) who were randomized to combination therapy experienced comparatively fewer adverse events, including gallbladder-related events (combination therapy, n=20 [4.1%]; monotherapy, n=24 [4.5%]), aspartate aminotransferase [AST] or alanine aminotransferase [ALT] elevations greater than or equal to three times the upper limit of normal (combination therapy, n=20 [4.1%]; monotherapy, n=27 [5.1%]), or severe muscle-related events with or without kidney dysfunction (combination therapy, n=7 [1.4%]; monotherapy, n=11 [2.1%]), than those randomized to simvastatin monotherapy. In both unadjusted and adjusted Cox proportional hazards models, we did not observe a significant difference in the effect of treatment on the occurrence of adverse safety events of special interest (gallbladder-related events, AST or ALT elevations greater than or equal to three times the upper limit of normal, or severe muscle-related events) across levels of kidney function (P>0.30 for all adjusted and unadjusted) (Supplemental Table 3). With respect to kidney function, we observed no significant difference (P=0.20) in the effect of treatment on change in mean eGFR over the 7-year follow-up period (Supplemental Figure 4, Supplemental Table 4).

Table 5.

Absolute incidence rates of adverse events by eGFR (milliliters per minute per 1.73 m2) and treatment arm (n=18,015)

| Adverse Event | eGFR<45 (%), n=1018 | eGFR=45–59 (%), n=2743 | eGFR=60–89 (%), n=9572 | eGFR≥90 (%), n=4682 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S Alone, n=532 | Ez/S, n=486 | S Alone, n=1359 | Ez/S, n=1384 | S Alone, n=4748 | Ez/S, n=4824 | S Alone, n=2372 | Ez/S, n=2310 | |

| Gallbladder-related adverse events | 24 (4.5) | 20 (4.1) | 57 (4.2) | 50 (3.6) | 160 (3.4) | 146 (3.0) | 78 (3.3) | 63 (2.7) |

| ALT, AST, or both ≥3×ULN | 27 (5.1) | 20 (4.1) | 38 (2.8) | 44 (3.2) | 87 (1.8) | 98 (2.0) | 54 (2.3) | 62 (2.7) |

| Myalgia | 12 (2.3) | 8 (1.6) | 14 (1.0) | 13 (0.9) | 56 (1.2) | 49 (1.0) | 20 (0.8) | 19 (0.8) |

| Myopathy | 3 (0.6) | 1 (0.2) | 3 (0.2) | 5 (0.4) | 3 (0.1) | 5 (0.1) | 1 (0.0) | 4 (0.2) |

| Rhabdomyolysis with or without kidney dysfunction | 4 (0.8) | 2 (0.4) | 3 (0.2) | 6 (0.4) | 7 (0.1) | 4 (0.1) | 3 (0.1) | 1 (0.0) |

| Myalgia with CK≥5×ULN | 4 (0.8) | 4 (0.8) | 3 (0.2) | 4 (0.3) | 17 (0.4) | 13 (0.3) | 7 (0.3) | 5 (0.2) |

| Myopathy, rhabdomyolysis, or myalgia with CK≥5×ULN | 11 (2.1) | 7 (1.4) | 9 (0.7) | 15 (1.1) | 26 (0.5) | 21 (0.4) | 11 (0.5) | 10 (0.4) |

Data are presented as n (%). S, simvastatin monotherapy; Ez/S, ezetimibe plus simvastatin; ULN, upper limit of normal; CK, creatinine kinase.

Discussion

In this post hoc analysis of the IMPROVE-IT, compared with simvastatin monotherapy, ezetimibe plus simvastatin was associated with a statistically significant cardiovascular relative risk reduction in individuals with moderately reduced kidney function. With respect to the primary composite end point—death from cardiovascular disease, a major coronary event, or nonfatal stroke—the treatment effect varied with baseline eGFR and was most pronounced among those with more marked reductions in eGFR (≤60 ml/min per 1.73 m2). At an eGFR of 75 ml/min per 1.73 m2, individuals in the combination treatment arm had a 9% relative risk reduction for the primary composite end point, but at eGFR levels of 60 and 45 ml/min per 1.73 m2, they experienced 12% and 13% risk reductions for the primary composite end point, respectively.

At the lowest eGFR levels (<45 ml/min per 1.73 m2), the absolute cardiovascular treatment benefit that we observed (NNT=12) was similar to other secondary prevention therapies in comparable increased risk populations. The Treating to New Targets Study, a subanalysis of individuals with known coronary heart disease and CKD, reported that, with respect to major cardiovascular events, treatment with atorvastatin 80 mg yielded an NNT of 24 over 5 years.8 In the Perindopril Protection against Recurrent Stroke Study, among individuals with known cerebrovascular disease and CKD, perindopril-based BP therapy yielded an NNT of 11 over 5 years with respect to major vascular events18; similarly, a study of individuals post-MI with heart failure and CKD from the Survival and Ventricular Enlargement study reported that treatment with captopril yielded an NNT of 9 over 3.5 years with respect to major cardiovascular events.19

After a series of trials that included large portions of individuals receiving dialysis, the benefit of statin-based therapies as eGFR declines (particularly to the point of requiring RRT) was uncertain.4,10 More recent work from the Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ Collaboration found a 21% relative risk reduction per each millimole per liter reduction in LDL cholesterol in a broad group of individuals defined as having CKD, but researchers also found that, despite an absolute benefit, the relative benefit of statin therapy seemed to decrease as eGFR declined.12 The SHARP trial showed that, compared with placebo, combination therapy with ezetimibe plus simvastatin was associated with primary cardiovascular risk reduction (major atherosclerotic events) for individuals with CKD, including those with severe reductions in eGFR.14 However, to what extent this observed benefit was due to the addition of ezetimibe, a cholesterol absorption inhibitor, is unknown. Despite important differences in the study populations—such as exclusion of individuals with CrCl<30 ml/min, higher doses of simvastatin, and a population with known coronary artery disease—our data support the efficacy of ezetimibe added to statin for further cardiovascular benefit in stabilized individuals with previous acute coronary syndrome (ACS) and moderately reduced eGFR.

Individuals with CKD have several risk factors for the development of cardiovascular disease, including malnutrition, chronic inflammation, increased oxidative stress, and vascular and endothelial dysfunction related to uremia and calcium and phosphorus dysregulation.20–22 Importantly, they also experience significant dyshomeostasis in lipid metabolism, leading to potentially modifiable atherosclerotic risks, including poor clearance of circulating triglycerides and lipoproteins, reduced lipoprotein lipase activity, increased oxidation of LDL cholesterol, and possibly, increased relative cholesterol absorption.23–26 In the IMPROVE-IT, compared with simvastatin monotherapy, individuals randomized to combination therapy with ezetimibe plus simvastatin experienced a greater mean reduction in both LDL cholesterol and triglycerides across all levels of eGFR. Because individuals with CKD are an inherently higher-risk group, achieving the same absolute level of reduction in LDL cholesterol through both inhibition of cholesterol synthesis and cholesterol absorption may be more effective in risk mitigation; however, considering the numerous mechanisms by which CKD leads to increased cardiovascular risk, the relative benefit that we observed from combination therapy as eGFR declined could also suggest that ezetimibe add-on therapy conferred pleiotropic effects beyond LDL cholesterol or triglyceride reduction alone. Statin therapies have been shown to modify vascular stiffness, inflammatory markers, oxidative stress, and endothelial function in individuals with CKD; however, the role of add-on therapy aimed at inhibiting intestinal cholesterol absorption in further altering such parameters in CKD populations and whether such changes correspond to additional reductions in cardiovascular events need further exploration.27–30

We note a few limitations of our study. In the prespecified subgroup analyses reported in the IMPROVE-IT, no interaction in treatment effect was observed across three categories of CrCl: <60, 60–89, and ≥90 ml/min. For our study, we instead assessed kidney function using GFR estimated by the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) equation, which is a putatively better estimator of kidney function,31 and we examined for a treatment effect across the entire range of kidney function rather than three fixed categories of CrCl. Given that our analyses were post hoc, they should be considered hypothesis forming and must be interpreted cautiously because they are subject to several inherent limitations, and although we did not observe differential study dropout by eGFR and treatment, unobserved biases (e.g., allocation or selection bias) may still be present. Additionally, although our study may expand the findings of the SHARP trial for individuals with moderate reductions in eGFR (30–60 ml/min per 1.73 m2), important differences remain. The IMPROVE-IT excluded individuals with CrCl<30 ml/min, incorporated higher doses of simvastatin, and included a study population with known coronary artery disease. Therefore, it remains unknown whether ezetimibe confers additional benefit over simvastatin monotherapy in individuals with more advanced CKD or individuals without known coronary artery disease. Likewise, we had no assessment of proteinuria, which limits our ability to draw conclusions about the effectiveness of these treatments for early-stage proteinuric kidney disease. With respect to safety, the SHARP trial showed that ezetimibe 10 mg plus simvastatin 20 mg can be safely used in individuals with moderate to severe reductions in kidney function.14 Consistent with these findings, our study suggests that combination therapy with ezetimibe plus simvastatin at higher doses (40 or 80 mg) can be safely used for individuals with moderately reduced kidney function; however, caution must still be applied, because these findings do not extend to individuals with severe reductions in eGFR (<30 ml/min per 1.73 m2). Finally, with respect to secondary and tertiary end points, we observed a trend toward benefit from combination therapy, but the overall treatment effects were not statistically different between the arms. The IMPROVE-IT was not powered to detect a difference in end points by level of eGFR; therefore, caution must be applied when interpreting these findings.

In conclusion, in stable individuals with prior ACS and LDL cholesterol levels within guideline recommendations, combination therapy with ezetimibe plus simvastatin seemed to be more effective than simvastatin monotherapy in reducing death from cardiovascular disease, major coronary events, or nonfatal stroke at moderately reduced levels of kidney function. The difference in treatment effect was observed as eGFR declined below 75 ml/min per 1.73 m2, and the benefit of combination therapy seemed to be most pronounced at eGFR levels ≤60 ml/min per 1.73 m2. Further studies examining the benefits of combination lipid-lowering therapy in individuals with CKD are needed, especially among those with more severe reductions in eGFR.

Concise Methods

Study Design and Patient Population

The study design and primary results of the IMPROVE-IT have been previously published.17,32,33 In brief, men and women ≥50 years old were eligible for inclusion if they had been hospitalized and stabilized within the preceding 10 days for an ACS defined as acute MI with or without electrocardiographic ST-segment elevation or high-risk unstable angina. Additionally, eligible individuals were required to have an LDL cholesterol level between 50 mg/dl (1.3 mmol/L) and 125 mg/dl (3.2 mmol/L) if not receiving lipid-lowering therapy or between 50 mg/dl (1.3 mmol/L) and 100 mg/dl (2.6 mmol/L) if receiving lipid-lowering therapy. Because of a lack of safety data for higher simvastatin doses at the start of the IMPROVE-IT, individuals with a CrCl<30 ml/min estimated by the Cockcroft–Gault equation or who had received dialysis within the previous 30 days were excluded. Individuals whose CrCl fell below 30 ml/min during follow-up were subject to discontinuation of therapy.

Between 2005 and 2010, a total of 18,144 individuals from 39 countries were randomized to receive, in a double-blinded method, either placebo plus simvastatin 40 mg once daily or combination ezetimibe 10 mg plus simvastatin 40 mg once daily. Both therapies were given in addition to standard ACS therapy, and simvastatin dose was increased to 80 mg in each arm if consecutive measures of LDL cholesterol were >79 mg/dl (2.0 mmol/L).

Individuals were followed up at 30 days, 4 months, and every 4 months thereafter. The primary end point was a composite of death from cardiovascular disease, a major coronary event (nonfatal MI, unstable angina requiring hospitalization, or coronary revascularization occurring ≥30 days after randomization), or nonfatal stroke. For this analysis, we also prespecified as outcomes of interest the secondary and tertiary study end points of (1) all-cause mortality, major coronary event, or nonfatal stroke; (2) death from cardiovascular disease, nonfatal MI, or nonfatal stroke; and (3) all-cause mortality. Treatment-blinded independent clinical events committees adjudicated all adverse safety events of special interest (elevations of AST or ALT, myalgias, myopathy, rhabdomyolysis with or without kidney dysfunction, and gallbladder-related events) and the components of the primary and secondary end points, except for revascularization.

Assessment of Kidney Function

We estimated GFR using the CKD-EPI equation34 on the basis of serum creatinine at the time of the qualifying event. For categorical analyses, we classified individuals by level of eGFR (<45, 45–59, 60–89, or ≥90 ml/min per 1.73 m2) to correspond with the Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes guidelines.35

Statistical Analyses

We conducted a post hoc investigation for an interaction between baseline eGFR and treatment arm with respect to the clinical end points. All data were analyzed using SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Baseline data were summarized by counts and percentages, means and SDs, or medians and interquartile ranges. For the primary composite end point, we performed Kaplan–Meier analyses stratified by treatment arm and eGFR categories to examine differences in event rates over 7 years of follow-up. To investigate the association between eGFR and clinical end points, we used Cox proportional hazards models, in which we used piecewise linear splines for eGFR to test for an interaction between eGFR and treatment arm and construct HRs. Because eGFR was treated as a continuous variable in these models, we calculated HRs for eGFR point estimates in prespecified 15-ml/min per 1.73 m2 increments (45, 60, 75, 90, and 105 ml/min per 1.73 m2). To account for varying follow-up time, we calculated the NNT using the Kaplan–Meier event rates rather than raw incidence rates.

Unadjusted models included linear splines for eGFR, treatment, and eGFR by treatment interaction terms. For graphical display, we used restricted cubic splines for eGFR to show the univariable relationship to each outcome for each treatment arm, and Figure 1 shows predicted event rates at 7 years of follow-up. The adjusted models included the same components along with the following covariates: age, sex, race, weight, family history of coronary artery disease, diabetes, hypertension, smoking status, history of angina, prior MI, prior percutaneous coronary intervention, prior coronary artery bypass graft, history of peripheral artery disease, prior stroke, prior congestive heart failure, percutaneous coronary intervention or catheterization at qualifying event, prior atrial fibrillation, baseline Killip class, systolic BP, heart rate, baseline medications (β-blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers, aspirin, or statin therapy), geographic region, qualifying event diagnosis, electrocardiographic changes (transient ST elevation, ST depression, and T-wave changes), hemoglobin at randomization, and baseline LDL, HDL, and triglycerides at time of qualifying event. Missing baseline data were imputed for all models both adjusted and unadjusted. With respect to the eGFR by treatment interactions, P values <0.05 were considered significant.

To examine the relationships between baseline eGFR and changes in lipid values at 1 year, linear modeling was performed. For all lipid models, covariates included randomized treatment arm, eGFR category at the time of qualifying event, and an interaction term between eGFR and treatment. We summarized incidence rates for adverse events of special interest, including elevations of AST or ALT, myalgias, myopathy, rhabdomyolysis with or without kidney dysfunction, and gallbladder-related events, stratified by treatment arm and eGFR category, and we used Cox proportional hazards models for eGFR to test for an interaction between eGFR and treatment arm with respect to gallbladder-related events, AST or ALT elevations greater than or equal to three times the upper limit of normal, or severe muscle-related events. To investigate the effect of treatment on change in eGFR over time, longitudinal modeling was used. Covariates in the model included randomized treatment, eGFR at the time of qualifying event, and visit period for on-treatment eGFR values.

Disclosures

J.W.S., J.W., and Y.L. have no conflicts of interest. D.M.C. received research support from Jannssen and consulted for Lilly. C.P.C. received grants from Accumetrics, Arisaph, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Merck, and Takeda and honoraria from BI, BMS, CSL Behring, Essentialis, GlaxoSmithKline, Kowa, Merck, Takeda, Lipimedix, Pfizer, Regeneron, and Sanofi. M.T.R. received grants from AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly & Co., Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Sanofi-Aventis, Daiichi-Sankyo, the Familial Hypercholesterolemia Foundation, and Ferring Pharmaceuticals; was involved in educational activities for Amgen and Bristol-Myers Squibb; and received honoraria from AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly & Co., Merck & Co., Daiichi-Sankyo, Elsevier Publishers, Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, PriMed, and Myokardia. M.A.B. was an advisory board member for Merck and consulted for AstraZeneca and Novartis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Merck & Co., Inc.

J.W.S. and M.A.B. had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

The sponsor provided funding for the Improved Reduction of Outcomes: Vytorin Efficacy International Trial; participated in the design, conduct, collection, management, and analysis of the data; and confirmed statistical analyses that were primarily performed by the Duke Clinical Research Institute. The sponsor’s participation was under the direction of the executive committee.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://jasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1681/ASN.2016090957/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Go AS, Chertow GM, Fan D, McCulloch CE, Hsu CY: Chronic kidney disease and the risks of death, cardiovascular events, and hospitalization. N Engl J Med 351: 1296–1305, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sarnak MJ, Levey AS, Schoolwerth AC, Coresh J, Culleton B, Hamm LL, McCullough PA, Kasiske BL, Kelepouris E, Klag MJ, Parfrey P, Pfeffer M, Raij L, Spinosa DJ, Wilson PW; American Heart Association Councils on Kidney in Cardiovascular Disease, High Blood Pressure Research, Clinical Cardiology, and Epidemiology and Prevention : Kidney disease as a risk factor for development of cardiovascular disease: A statement from the American Heart Association Councils on Kidney in cardiovascular disease, high blood pressure research, clinical cardiology, and epidemiology and prevention. Hypertension 42: 1050–1065, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matsushita K, van der Velde M, Astor BC, Woodward M, Levey AS, de Jong PE, Coresh J, Gansevoort RT; Chronic Kidney Disease Prognosis Consortium : Association of estimated glomerular filtration rate and albuminuria with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in general population cohorts: A collaborative meta-analysis. Lancet 375: 2073–2081, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fellström BC, Jardine AG, Schmieder RE, Holdaas H, Bannister K, Beutler J, Chae DW, Chevaile A, Cobbe SM, Grönhagen-Riska C, De Lima JJ, Lins R, Mayer G, McMahon AW, Parving HH, Remuzzi G, Samuelsson O, Sonkodi S, Sci D, Süleymanlar G, Tsakiris D, Tesar V, Todorov V, Wiecek A, Wüthrich RP, Gottlow M, Johnsson E, Zannad F; AURORA Study Group : Rosuvastatin and cardiovascular events in patients undergoing hemodialysis. N Engl J Med 360: 1395–1407, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hou W, Lv J, Perkovic V, Yang L, Zhao N, Jardine MJ, Cass A, Zhang H, Wang H: Effect of statin therapy on cardiovascular and renal outcomes in patients with chronic kidney disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Heart J 34: 1807–1817, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Palmer SC, Craig JC, Navaneethan SD, Tonelli M, Pellegrini F, Strippoli GF: Benefits and harms of statin therapy for persons with chronic kidney disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 157: 263–275, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Palmer SC, Navaneethan SD, Craig JC, Johnson DW, Perkovic V, Hegbrant J, Strippoli GF: HMG CoA reductase inhibitors (statins) for people with chronic kidney disease not requiring dialysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 5: CD007784, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shepherd J, Kastelein JJ, Bittner V, Deedwania P, Breazna A, Dobson S, Wilson DJ, Zuckerman A, Wenger NK; TNT (Treating to New Targets) Investigators : Intensive lipid lowering with atorvastatin in patients with coronary heart disease and chronic kidney disease: The TNT (Treating to New Targets) study. J Am Coll Cardiol 51: 1448–1454, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tonelli M, Isles C, Curhan GC, Tonkin A, Pfeffer MA, Shepherd J, Sacks FM, Furberg C, Cobbe SM, Simes J, Craven T, West M: Effect of pravastatin on cardiovascular events in people with chronic kidney disease. Circulation 110: 1557–1563, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wanner C, Krane V, März W, Olschewski M, Mann JF, Ruf G, Ritz E; German Diabetes and Dialysis Study Investigators : Atorvastatin in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus undergoing hemodialysis. N Engl J Med 353: 238–248, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yan YL, Qiu B, Wang J, Deng SB, Wu L, Jing XD, Du JL, Liu YJ, She Q: High-intensity statin therapy in patients with chronic kidney disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 5: e006886, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cholesterol Treatment Trialists' (CTT) Collaboration, Herrington WG, Emberson J, Mihaylova B, Blackwell L, Reith C, Solbu MD, Mark PB, Fellström B, Jardine AG, Wanner C, Holdaas H, Fulcher J, Haynes R, Landray MJ, Keech A, Simes J, Collins R, Baigent C: Impact of renal function on the effects of LDL cholesterol lowering with statin-based regimens: A meta-analysis of individual participant data from 28 randomised trials. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 4: 829–839, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Baigent C, Keech A, Kearney PM, Blackwell L, Buck G, Pollicino C, Kirby A, Sourjina T, Peto R, Collins R, Simes R; Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ (CTT) Collaborators : Efficacy and safety of cholesterol-lowering treatment: Prospective meta-analysis of data from 90,056 participants in 14 randomised trials of statins. Lancet 366: 1267–1278, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baigent C, Landray MJ, Reith C, Emberson J, Wheeler DC, Tomson C, Wanner C, Krane V, Cass A, Craig J, Neal B, Jiang L, Hooi LS, Levin A, Agodoa L, Gaziano M, Kasiske B, Walker R, Massy ZA, Feldt-Rasmussen B, Krairittichai U, Ophascharoensuk V, Fellström B, Holdaas H, Tesar V, Wiecek A, Grobbee D, de Zeeuw D, Grönhagen-Riska C, Dasgupta T, Lewis D, Herrington W, Mafham M, Majoni W, Wallendszus K, Grimm R, Pedersen T, Tobert J, Armitage J, Baxter A, Bray C, Chen Y, Chen Z, Hill M, Knott C, Parish S, Simpson D, Sleight P, Young A, Collins R; SHARP Investigators : The effects of lowering LDL cholesterol with simvastatin plus ezetimibe in patients with chronic kidney disease (Study of Heart and Renal Protection): A randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 377: 2181–2192, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wanner C, Tonelli M; Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes Lipid Guideline Development Work Group Members : KDIGO clinical practice guideline for lipid management in CKD: Summary of recommendation statements and clinical approach to the patient. Kidney Int 85: 1303–1309, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stone NJ, Robinson JG, Lichtenstein AH, Bairey Merz CN, Blum CB, Eckel RH, Goldberg AC, Gordon D, Levy D, Lloyd-Jones DM, McBride P, Schwartz JS, Shero ST, Smith SC Jr., Watson K, Wilson PW, Eddleman KM, Jarrett NM, LaBresh K, Nevo L, Wnek J, Anderson JL, Halperin JL, Albert NM, Bozkurt B, Brindis RG, Curtis LH, DeMets D, Hochman JS, Kovacs RJ, Ohman EM, Pressler SJ, Sellke FW, Shen WK, Smith SC Jr., Tomaselli GF; American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines : 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. Circulation 129[Suppl 2]: S1–S45, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cannon CP, Blazing MA, Giugliano RP, McCagg A, White JA, Theroux P, Darius H, Lewis BS, Ophuis TO, Jukema JW, De Ferrari GM, Ruzyllo W, De Lucca P, Im K, Bohula EA, Reist C, Wiviott SD, Tershakovec AM, Musliner TA, Braunwald E, Califf RM; IMPROVE-IT Investigators : Ezetimibe added to statin therapy after acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med 372: 2387–2397, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Perkovic V, Ninomiya T, Arima H, Gallagher M, Jardine M, Cass A, Neal B, Macmahon S, Chalmers J: Chronic kidney disease, cardiovascular events, and the effects of perindopril-based blood pressure lowering: Data from the PROGRESS study. J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 2766–2772, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tokmakova MP, Skali H, Kenchaiah S, Braunwald E, Rouleau JL, Packer M, Chertow GM, Moyé LA, Pfeffer MA, Solomon SD: Chronic kidney disease, cardiovascular risk, and response to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition after myocardial infarction: The Survival And Ventricular Enlargement (SAVE) study. Circulation 110: 3667–3673, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yamamoto S, Kon V: Mechanisms for increased cardiovascular disease in chronic kidney dysfunction. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 18: 181–188, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kestenbaum B, Sampson JN, Rudser KD, Patterson DJ, Seliger SL, Young B, Sherrard DJ, Andress DL: Serum phosphate levels and mortality risk among people with chronic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 16: 520–528, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peev V, Nayer A, Contreras G: Dyslipidemia, malnutrition, inflammation, cardiovascular disease and mortality in chronic kidney disease. Curr Opin Lipidol 25: 54–60, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Frischmann ME, Kronenberg F, Trenkwalder E, Schaefer JR, Schweer H, Dieplinger B, Koenig P, Ikewaki K, Dieplinger H: In vivo turnover study demonstrates diminished clearance of lipoprotein(a) in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int 71: 1036–1043, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kwan BC, Kronenberg F, Beddhu S, Cheung AK: Lipoprotein metabolism and lipid management in chronic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 1246–1261, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Silbernagel G, Fauler G, Genser B, Drechsler C, Krane V, Scharnagl H, Grammer TB, Baumgartner I, Ritz E, Wanner C, März W: Intestinal cholesterol absorption, treatment with atorvastatin, and cardiovascular risk in hemodialysis patients. J Am Coll Cardiol 65: 2291–2298, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baigent C: Cholesterol metabolism and statin effectiveness in hemodialysis patients. J Am Coll Cardiol 65: 2299–2301, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ichihara A, Hayashi M, Ryuzaki M, Handa M, Furukawa T, Saruta T: Fluvastatin prevents development of arterial stiffness in haemodialysis patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nephrol Dial Transplant 17: 1513–1517, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nakamura T, Ushiyama C, Hirokawa K, Osada S, Shimada N, Koide H: Effect of cerivastatin on urinary albumin excretion and plasma endothelin-1 concentrations in type 2 diabetes patients with microalbuminuria and dyslipidemia. Am J Nephrol 21: 449–454, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dogra G, Irish A, Chan D, Watts G: A randomized trial of the effect of statin and fibrate therapy on arterial function in CKD. Am J Kidney Dis 49: 776–785, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chang JW, Yang WS, Min WK, Lee SK, Park JS, Kim SB: Effects of simvastatin on high-sensitivity C-reactive protein and serum albumin in hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis 39: 1213–1217, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Michels WM, Grootendorst DC, Verduijn M, Elliott EG, Dekker FW, Krediet RT: Performance of the Cockcroft-Gault, MDRD, and new CKD-EPI formulas in relation to GFR, age, and body size. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 5: 1003–1009, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cannon CP, Giugliano RP, Blazing MA, Harrington RA, Peterson JL, Sisk CM, Strony J, Musliner TA, McCabe CH, Veltri E, Braunwald E, Califf RM; IMPROVE-IT Investigators : Rationale and design of IMPROVE-IT (IMProved Reduction of Outcomes: Vytorin Efficacy International Trial): Comparison of ezetimbe/simvastatin versus simvastatin monotherapy on cardiovascular outcomes in patients with acute coronary syndromes. Am Heart J 156: 826–832, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Blazing MA, Giugliano RP, Cannon CP, Musliner TA, Tershakovec AM, White JA, Reist C, McCagg A, Braunwald E, Califf RM: Evaluating cardiovascular event reduction with ezetimibe as an adjunct to simvastatin in 18,144 patients after acute coronary syndromes: Final baseline characteristics of the IMPROVE-IT study population. Am Heart J 168: 205–212.e1, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro AF 3rd, Feldman HI, Kusek JW, Eggers P, Van Lente F, Greene T, Coresh J; CKD-EPI (Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration) : A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med 150: 604–612, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes Working Group : KDIGO 2012 clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int Suppl 3: 1–150, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.