Abstract

Context

A national system of voluntary public health accreditation for state, local and tribal health departments (LHD) is part of a movement that aims to improve public health performance with ultimate impact on population health outcomes. Indiana is a good setting for the study of LHD accreditation adoption because several LHDs reported de-adopting accreditation in a recent statewide survey, and because 71% of Indiana counties serve populations of ≤ 50,000.

Design

A systematic method of analyzing qualitative data based on the performance improvement model (PIM) framework to expand our understanding of de-adoption of public health accreditation.

Setting/Participants

In 2015, we conducted a key informant interview study of the three LHDs that decided to delay their engagement in the accreditation based on findings from an Indiana survey on LHD accreditation adoption. The study is an exploration of LHD accreditation de-adoption, and of the contributions made to its understanding by the Performance Improvement Model (PIM).

Result

The study found that top management team members are those who champion accreditation adoption, and that organizational structure and culture facilitate the staff’s embracing of the change. The PIM was found to enhance the elucidation of the inner domain elements of CFIR in the context of de-adoption of public health accreditation.

Conclusion

Governing entities’ policies & priorities appear to mediate whether the LHDs are able to continue accreditation pursuit. Lacking any of these driving forces appears to be associated with decisions to de-adoption of accreditation. Further work is necessary to discern specific elements mediating decisions to pursue accreditation.

Introduction

A national system of voluntary public health accreditation for state and local health departments (LHD) is part of a movement emerging from the 1988 Institute of Medicine’s report on the future of public health and the 2002 follow-up report.1,2,3,4,5 Two central features of accreditation systems are: the principle of external review and the use of performance standards. In 2011 the Public Health Accreditation Board (PHAB) initiated a national voluntary accreditation process.6,7 As of November of 2016, 142 local health departments have been accredited by PHAB.8 The accreditation process requires that each LHD complete a series of tasks from several accreditation domains. LHD organizational characteristics may have an impact on the level of success or challenge for task completion, and to sustaining related change. For example, existing studies have found that LHD accreditation pursuit has been associated with formal quality improvement programming, and that the implementation of accreditation can be facilitated by financial and legal incentives, population size, degree of top executive, governance structure, state health department accreditation pursuit, and the existence of formal quality improvement initiatives.9,10,11,12

Health departments vary considerably in size and investment by state and local governments. Questions remain about whether adoption of accreditation as an innovation will in fact occur for all of the roughly 2000 local health departments, or whether some will opt out of adoption. Studies have identified several barriers and facilitators of accreditation.13,14,15,16,17,18,19 However, not much has been done to explore accreditation in states with low public health investment and for health departments that vary in size.20 This is an important oversight because financial incentives and characteristics that likely result from greater organizational resources appear to influence the adoption of accreditation.

Indiana is a good state to serve as a laboratory to explore accreditation adoption because it is ranked low among peers for public health investment state. The state per capita public health investment is $17.43 (ranked 37th), and Indiana is last among states for federal per capita investments from CDC (ranked 50th) and HRSA (ranked 50th).21 This investment picture has not changed appreciably in the last five years.

As part of the public health improvement effort, the Indiana Public Health Association (IPHA), an organization representing local health departments and public health professionals, conducted two surveys in 2013 and late 2014 – both with strong response rates (76.0% and 74.25 respectively).22,23 Among the respondents of the most recent survey, thirteen reported that they decided not to pursue accreditation. The top three most common reasons for this were: (1) accreditation standards exceeded the capacity of the LHD, (2) fees for accreditation were too high, and (3) time and effort required for accreditation application exceeded the benefit of accreditation. While there have been studies noting barriers to accreditation adoption, this is (to our knowledge) the first study to examine de-adoption. As organizational factors appear to influence accreditation, we sought to explore health department decisions to de-adopt accreditation among a small sample of de-adopting LHDs using an organizational framework to examine leadership rationale for non-pursuit of accreditation, and leadership perception of barriers to and facilitators of accreditation adoption and pursuit.

Theoretical Framework

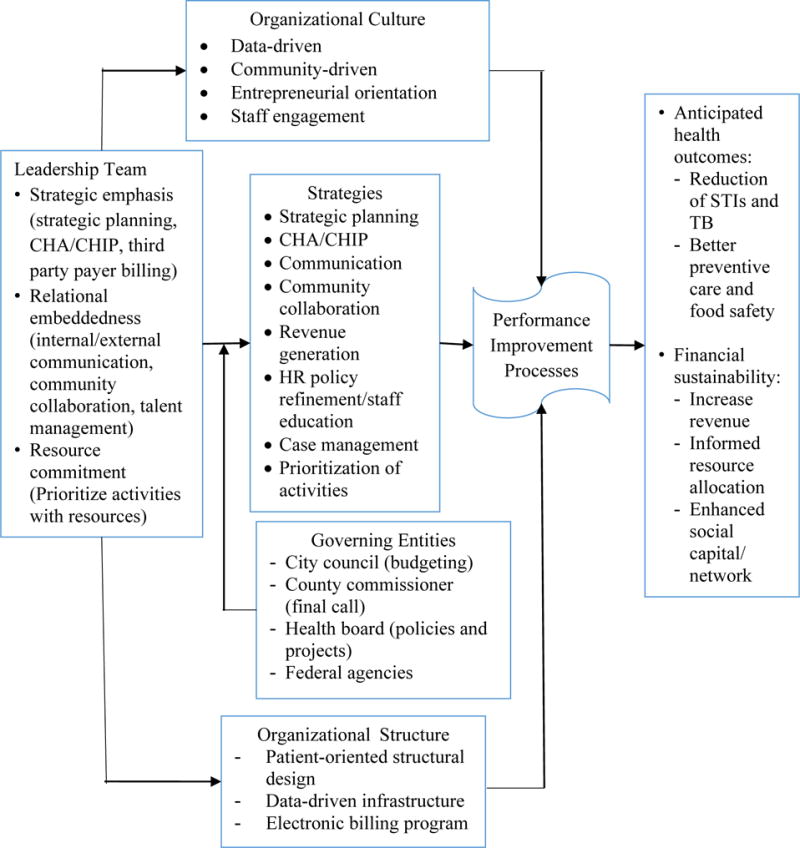

Health services researchers have advocated adoption of the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) for guiding formative evaluations and building implementation knowledge that translate into meaningful patient care outcomes across multiple contexts.24 Public health accreditation, in theory, facilitates formal quality improvement programming. As an intervention, accreditation guides LHDs to systematically improve public health services delivery and, ultimately, effectively address health concerns and priorities in their respective communities. This study was the first attempt to adopt the overall CFIR framework to explore developing strategies that drive effective implementation of quality improvement programs for sustainably producing positive health outcomes. We focus mainly on the constructs relating to the inner setting of CFIR, such as culture and leadership engagement and enhance the use of CFIR by integrating aspects of the Performance Improvement Model (PIM). The PIM is a composite model based on previous work in the business domain, where performance improvement occurs with the championship of the leadership team through strategic emphases, relational embeddedness, and resource commitment.25,26 A strategic emphasis is important for task initiation and completion, while relational embeddedness provides social support to and approval of the leader’s requests and tasks. The PIM further elucidates inner domain elements of the CFIR as shown in Figure 1. Our sample size reflects the exploratory nature of this study, as we sought to understand how well the PIM enhanced CFIR framework provides explanatory value to the question of accreditation de-adoption. The ethnographic perspectives of the interviewees in Indiana and their insights may reflect the challenges and lessons that are encountered by their counterparts in Indiana and in other states. Theory development will allow the construction of measures related to key components of the PIM-enhanced CFIR framework in larger accreditation de-adoption studies. These elements are briefly discussed below.

Figure 1.

Proposed Performance Improvement Model (PIM) – Enhanced Internal Domain Elements of the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR)

Leadership Team

Leadership foresight and experience affect problem solving capabilities, which in turn impact the organizational performance.27 Resource commitment is the leader’s ability to identify a task that needs to be done, find the resource necessary, and use it to accomplish a project. Studies have shown that environmental changes may drive an entrepreneurial practice, such as identifying opportunities and modifying practices to adapt to the impetus for change, and such a process could be mediated by the leadership team.28

Organizational Structure

Organizational structure consists of the employees within the LHD and how they function in relation to others as a whole for accomplishing certain goals. Both organizational structure and its relationship with the governing entities play an important role in organizational performance.29,30 The desired process in the PIM model is quality improvement. More recent studies have essentially echoed the discourse of sociology with respect to the relationship between organizational structure and performance. Increasing division of labor through an organizational network and its interdependency leads to more innovation, having more active internal communication channels.31,32 Leaders determine the organization’s strategic choice, and institutionalization of management infrastructure promotes organizational performance in increasing customer capital.24,33

Organizational culture

Organizational culture refers to beliefs and values shared by employees, as well as employee expectations, attitudes, and norms.34,35 The cultivation of organizational culture is a dynamic process and has served as a tactic for leaders to facilitate strategic organizational transformation.36,37 Prior studies have observed the influence of organizational culture on strategic implementation, organizational change, learning, innovation, performance and effectiveness.38,39,40 The attitudes and beliefs of the individuals within the organization shape the culture of the organization. In turn, the culture drives a collective view and attitude as to how things should be done within the organization and shapes the individuals within the organization over time.

Governing entities

The institutional environment is ubiquitous and influences an organization’s strategy, customer relationships and performance.41 The institutional network tends to be overlooked for managing strategies and customer relationships. In the public health sector, the governing entity directly affects organizational operations through policies and regulations.42 The governing entity is expected to play an instrumental role throughout the accreditation process. It can provide guidance, but can also be a roadblock in the operations of the organization, particularly when determining available resources for the accreditation process. These entities can be at many different levels, whether managerial or governmental. In the case of LHDs, that could include a county board of health, county commission, administrative leadership within the executive branch of government at local, state, and federal levels, and the legislative branch at the state and federal levels.

Methodology

The study aims to initially explore LHD de-adoption of accreditation through the application of an enhanced theoretical framework that highlight evidence-based aspects of facilitators and barriers to accreditation adoption. Through this, we seek an in-depth understanding of individual LHD practices and the underlying issues contributing to reported barriers to public health accreditation pursuit. We use a case study approach with three selected LHDs among those reported de-adoption of accreditation in Indiana in the 2015 survey. This approach will allow theoretical synthesis to conceptualize needed components for successful implementation of accreditation pursuit strategies.43 Data gathering was conducted through individual interviews with selected LHD staff. The interviews were conducted by a group of three researchers to each LHD. The personal interviews lasted approximately 90 minutes and were audio-recorded and then transcribed into transcripts for analysis. A guided interview instrument with open-ended questions was developed based on the PIM-enhanced CFIR framework and the PHAB accreditation domains. The questions were piloted with a health department that was working with the PI on their preparation for public health accreditation application to ensure the questions were clear and relevant. Three researchers coded the interview transcripts together in reference to the PIM-enhanced CFIR with focus on the following constructs: Leadership Team, Organizational Culture, Organizational Structure, and Governing Entities, Policies, and Regulations. Coding consensus was reached through conference with the principal investigator. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Purdue University (IRB #1603017352). Data will be reported using pseudonyms of “LHD A”, “LHD B”, and “LHD C”.

Sample

Three LHDs among the 13 reporting accreditation de-adoption agreed to participate in this exploratory study. They were selected by convenience. Each served varying population sizes: above 350,000, around 200,000, and less than 50,000, respectively. Prior to each interview, the research team collected publically available secondary data about LHD characteristics: organization information, services offered, and the community that it serves.

A total of six interviewees participated in this exploratory study. LHDs A and C had only the Administrator joined the interview. LHD B had the Health Officer, Emergency Preparedness Coordinator, the Nurse/Health Educator, and the Food and Environment Inspector.

Findings

Participant LHDs served similar populations: predominantly White, non-Hispanic populations with similar characteristics in educational levels (which were mostly high school graduates and higher (between 75–89% of the population) and median household income level around $47K to 49K. Table 1 details some of their demographic characteristics.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of the Sample Indiana Local Health Departments (LHDs) De-adopting Public Health Accreditation, (N=3)

| People | A | B | C |

|---|---|---|---|

| Population (July 1, 2015) | 368,450 | 203,474 | 32,906 |

| Female (July 1, 2015) | 51.2% | 50.5% | 50.0% |

| Under 18 years (July 1, 2015) | 26.1% | 28.0% | 29.2% |

| 65 years and over (July 1, 2015) | 13.4% | 13.6% | 14.7% |

| White alone, not Hispanic or Latino (July 1, 2015) | 74.5% | 75.5% | 92.4% |

| African American alone (July 1, 2015) | 12.1% | 6.3% | 1.3% |

| Hispanic or Latino (July 1, 2015) | 7.3% | 15.3% | 4.6% |

| Asian alone (July 1, 2015) | 3.8% | 1.2% | 0.7% |

| High school graduate or higher, % of persons age 25 years+, 2011–2015 | 89.3% | 80.8% | 74.8% |

| Median household income (in 2015 dollars), 2011–2015 | $49,092 | $47,913 | $47,342 |

Among the three LHDs, participant organization “A” faced more challenges in terms of increasing number of transient populations from the neighboring states, according to the interviewer’s observation, when the county already had higher percentages of African Americans (12.1% vs. 6.3% in LHD B and 1.3% in LHD C) and Asians (3.8% vs. 1.2% and 0.7%, respectively). They all have about 50–50 males and females. The distribution of age groups among all three LHDs seem comparable, more children under 18 years of age (around 26–28%) compared to the senior population at 65 years of age and older (13–14%). The health rankings of these three LHDs were in the middle range among ninety-three local health departments in Indiana.44

Table 2 lists exemplar statements related to the emerging themes and issues from interviews.

Table 2.

Key Themes and Exemplar Statements from Indiana LHDs Deferring Public Health Accreditation based on the PIM-Enhanced CFIR Framework, 2016 (N=6)

| Theme | Category/Coding Node | Exemplar |

|---|---|---|

| Leadership |

|

|

| Organizational Culture |

|

|

| Organizational structure |

|

|

| Governing entities |

|

|

| Quality Improvement |

|

|

| Resources |

|

|

| Barriers |

|

|

Leadership Team

Overall, the leadership team presented itself as an important driving force or change agent for undertaking quality and performance improvement processes, which could not be possible if there were not having a champion for the cause, convincing others that they should participate, and locating the resources necessary to follow it through. The barriers identified for continual pursuit of accreditation primarily fell into five categories: workforce, funding, usability of evaluation tools, relevance, and time. Figure 2 presents these barriers and the linkages among some of the barriers. However, all the leaders of the three case LHDs were actively engaged in and committed to performance improvement efforts. None of these leaders could be convinced of the immediate benefits of the accreditation exercise. The leadership team’s perception drove the decision of deterring the pursuit of accreditation.

Figure 2.

Perceived Barriers to Public Health Accreditation Adoption of the Sample Indiana Local Health Departments (LHDs), (N=6)

Participants reported formulated strategies for quality and performance improvement efforts based on their vision and needs. LHD C was a smaller LHD, serving a community of < 50,000 residents, with few staff and a small budget. The Administrator tended to wear multiple hats; constantly experiencing tension between the time needed for routine operations and for attending to accreditation time frames. In view of the resource constraints, LHD C strategically formed alliances this LHDs and other community partners in serving the communities at large. However, there had not been resources for conducting any of the community health assessment, community health improvement program, or strategic plan. The other two LHDs reported having more staff support. As such, they ventured into formulating community health improvement plans based on their own community health assessment. LHD B outsourced an effort to develop their strategic plan.

While all participants recognized the importance of continually improving the efficiency and effectiveness of their public health service delivery, each reported experiencing budget sequestration in recent years. All reported that there were no available funds from the local governing entities or the State for the accreditation process, such as for membership dues, service charges, and staffing costs. For those engaging in some aspects of accreditation readiness (LHD A and B), they operated mainly on the general budget. There were some funding opportunities, such as for emergency preparedness, but acquiring resources from their County Councils has always been an arduous effort. Consequently, the case LHDs participants all held the view that they would rather focus on improving specific division effectiveness in serving the community as opposed to spending money and time on trying to become accredited. That said, a main concern appeared to be whether accredited status would strengthen LHD’s future position in seeking grant funds from the funding agencies at the state or the federal level. When discussing accreditation, all six participants interviewed shared a concern about the fabrication of accreditation documentation due to its complexity and unfamiliarity of the process on the part of the staff. It was thought necessary to have a designated personnel for managing all the documentation requirements.

Organizational Culture

Three LHDs shared a common culture that community needs drive LHD services offered. Each, however, cultivated their respective organizational culture based on their leader’s vision. LHD A placed more emphasis on staff engagement. The administrator refined human resource policies to retain the best talent, and attempted to cultivate a shared quality assurance mindset through staff education. With their “data-and community-driven culture”, LHD A strived to excel in case management.

Cultural elements appeared to infuse the approach to the resource constrained environment. For example, LHD B embraced financial challenges with more entrepreneurial approaches. Its Health Officer not only obtained legal authority to generate revenue through third party reimbursement for services provided in their clinical setting but also cultivated the market-driven orientation of the staff as to how to expand their clientele and provide patient-centered care to improve patient loyalty. In contrast, the Administrator of the smaller LHD C was working to change the staff’s perception that public health services should be offered free to the residents in need, particularly to the uninsured and medically underserved populations.

Organizational Structure

Participating LHDs shared similar basic organizational structure. These structures appeared to ensure delivery of a wide range of activities for which the LHD was responsible; and each appeared to have sufficient span of control to alter the structure in order to meet service needs. LHD C had only six full time employees, and each had job responsibilities across multiple areas. Both LHDs A and B, on the other hand, had organized multiple functions in divisions managed by division directors. Each of these two LHDs had internal communication channels to ensure timely communication of the vision, policy change, and guidelines, and external channels with their governing entities and other community partners. LHD B, for example, modified their STI clinics from appointment-based to walk-in to respond to community needs and feedback. They also established a data-driven infrastructure and an electronic billing program. Staff of LHD A instituted a county-wide network to ensure that all individuals diagnosed with TB were taking their medication.

All participating LHDs reported collaborating with a wide variety of community partners, including local physicians, surrounding county health departments, and local hospitals. Participants felt that building this social capital through networks contributed to greater organizational and service efficiency. For example, local physicians provided LHD C with professional guidance, and some served on the board of health. This LHD’s relationship with surrounding counties primarily focused on sharing clinic resources with other LHDs, since these other LHDs generally lacked sufficient medical services to run their own independent clinics.

Governing Entities, Policies, and Regulations

LHDs reported that their governing entities served as mediators in the strategic decision making process. Examples include working with the city or county councils funding, working with the Board of Health to address policy and project concerns, and working with federal agencies, such as CDC, for relevant information and guidance. The LHDs reported occasionally receiving grant funding for emergency preparedness from Homeland Security and the U.S. Center for Disease Control (CDC) through the state government. Those LHDs that have designated personnel to write grants tend to have better funding. Both LHDs A and B had a better outcome in this aspect as a result. Overall, the state entities did not support the local departments in the accreditation efforts. These grants usually have designated use or for desired health outcomes, such as smoking cessation, or emergency preparedness. The local governing entities guided the LHDs in creating their budgets by providing a specific budget target for annual spending. Participant LHDs reported that these local governing entities were important forces in determining the goals and direction of the health department. Government efficiency seemed to be the major concern of these entities. LHDs shared similar views about the importance that of requesting appropriation in line with the council’s target.

Figure 3 summarizes the findings of the existing efforts of the participating LHDs toward quality improvement of their service delivery, which leads to improved health outcomes in the community and financial sustainability for the department. The figure illustrates the four driving forces of the existing strategies and their relationships.

Figure 3.

Mapping of Current Quality Improvement Activities in Sample Local Health Departments (LHDs), (N=3)

Discussion and Recommendations

Contemporary public health service delivery requires a workforce capable of making data-driven decisions, providing population based patient-centered care, and managing solution-based operations. Within their own transformational environments, each LHD reported being challenged with funding, staffing, and time. Preparation for accreditation further intensified the extent of these perceived challenges. While the twelve domains of public health accreditation provide a comprehensive quality improvement model found to be associated with tangible benefits, the burden for PHAB remains how best to connect the model with value propositions perceived relevant and beneficial by the LHDs as well as well as their governing entities and community partners. It is not enough to convince the LHDs of this, as each participant recognized the benefit of accreditation. LHD perceptions of their external environment appeared to sufficiently limit the span of perceived opportunity for accreditation pursuit. For example, if budget targets were set for already fiscally austere LHDs, then new resources to pursue accreditation would be out of the question. If human resources were such that grant development was not possible – even if not related to accreditation, then new grant resource pursuit would not be possible. That said, if public health accreditation were recognized as an important value proposition by the governing entities, then perhaps targeted investments from federal, state and local partners would be made. LHD pursuit of such resource from county commissions today is not likely. As has been previously found, LHDs generally do not have an orientation toward policy engagement.45,46 The Meyerson and Sayegh study found that LHDs in smaller states (such as Indiana) engaged less with their local governing bodies than those in larger states. Thus, the challenge is not only with the governing entities, but the LHD policy behavior orientation and skill set.

This exploratory case study confirmed and verified the value of the PIM-enhanced CFIR framework, as it allowed deeper exploration of CFIR internal domain issues that might impact accreditation adoption or de-adoption. Specifically, the findings of the impact of organizational structure, governing entities, and organizational culture of PIM are in line with the proposed structural characteristics, communication and network, and culture elements of the CFIR framework. Future studies are called to further test whether the additional implementation climate of CFIR should be considered as an independent construct of organizational culture.

The accreditation process in fact promotes LHDs to undertake performance improvement effort. Table 3 Compares and contrasts the perceived barriers to accreditation adoption between the PHAB domains and the PIM-enhanced CFIR internal domains; and proposes strategies for the decision makers to consider for their public health services performance improvement efforts.

Table 3.

Barriers to Public Health Accreditation Adoption by PHAB Domain and Informed by the PIM-enhanced CFIR, Indiana, 2016

| Barriers | Domain | Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Leadership | ||

| Funding | Domain 12 - Maintain capacity to engage the public health governing entity |

|

| Personnel | Domain 8 - Maintain a competent public health workforce Domain 11- Maintain administrative and management capacity |

|

| Policy (favoring/facilitating accreditation) | Domain 11- Maintain administrative and management capacity Domain 12 - Maintain capacity to engage the public health governing entity |

|

| Relevance | Domain 11- Maintain administrative and management capacity |

|

| Organizational Structure and Culture | ||

| Workforce | Domain 8 – Maintain a competent public health workforce Domain 11 – Maintain administrative and management capacity |

|

| Infrastructure | Domains 1&2 – Monitor health and investigate problems Domain 4 – Mobilize community partnership Domain 11- Maintain administrative and management capacity |

|

| Governing Entities | ||

| Competing priorities |

|

|

While external and resource environments loomed large for participants, it also appeared that leadership was an important driver for formulating accreditation preparedness strategies. PHAB has to be able to not only facilitate the development of an LHD leadership charge, but also help frame the perspective of governing entities with respect to the value proposition of accreditation. As for working with LHD leadership, PHAB may further delineate Domains 8, 11, and 12 in accordance with LHD concern about funding, personnel, policies that promotes accreditation, and relevance of the accreditation process with their routine challenges. In other words, the PHAB domains, standards and measures are expressed through the strategies which LHD champions are able to undertake in order to build their organizational culture, structure, and to communicate effectively with their respective governing entities around accreditation.

PHAB’s trainers have been working closely with the LHDs. Their roles as consultants to LHD leadership and staff may further facilitate efforts to develop the workforce in terms of LHD orientation and skillset; and to build infrastructure for knowledge management (i.e., data management and utilization), project management (i.e., platform for planning and execution of initiatives), talent management (i.e., human resource policies) and collaboration with their partners.

Implications for Policy and Practice

This initial case study suggests that the Performance Improvement Model (PIM) strengthens the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) framework for building implementation science in the context of public health. The PIM-enhanced CFIR framework can help to systematically map the ongoing performance and quality improvement efforts of LHDs. Its use with future, larger studies of LHD accreditation adoption or de-adoption will further clarify its explanatory value relate to the internal LHD environment and its perceptions about the external environment of LHDs.

Limitations

Due to its exploratory nature, this study examined only three out of thirteen de-adopters. There is an ongoing effort in further investigate the perceptions from all the de-adopters and compare them with that of the adopters in the State of Indiana. The low public health investment in Indiana may inherently impact the applicability of the findings from Indiana to the other better-funded states. A thorough examination of both internal and external domain elements should be considered for developing CFIR framework for enhancing public health accreditation nationwide.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported, in part, with support from the Project Development Team within the ICTSI NIH/NCRR Grant Number UL1TR001108. We appreciated the guidance from the PDT members and the Editorial Board of JPHMP. We also would like to thank all the undergraduate students and the staff members from the local health departments who contributed to this research projects.

Disclosure of funding: This publication was supported by a Project Development Team within the ICTSI NIH/NCRR Grant Number UL1TR001108.

Contributor Information

Sandra S. Liu, Department of Consumer Science, College of Health and Human Sciences, Purdue University, 812 W. State Street, Room 318, West Lafayette, IN 47907, Tel: 765-494-8310, liuss@purdue.edu.

Beth Meyerson, Department of Applied Health Science, Indiana University School of Public Health – Bloomington.

Jerry King, Indiana Public Health Association.

Yuehwern Yih, School of Industrial Engineering, Purdue University.

Mina Ostovari, School of Industrial Engineering, Purdue University.

References

- 1.Fortes MTR, Baptista TWDF. (2012). Accreditation: Tool or policy for health systems organizations? Acta Paulista de Enfermagem. 2012;25(4):626–631. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scrivens EA. Taxonomy of the dimensions of accreditation systems. Social Policy & Administration. 1996;30(2):114–124. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Institute of Medicine (U.S.), editor. The Future of Public Health. Washington, D.C: National Academy Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carman AL, Timsina L. Public health accreditation: Rubber stamp or roadmap for improvement. American Journal of Public Health. 2015;105(S2):S353–S359. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mays G, Beitsch LM, Corso L, Chang C, Brewer R. States gathering momentum: Promising strategies for accreditation and assessment activities in multistate learning collaborative applicant states. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice. 2007;13(4):364–373. doi: 10.1097/01.PHH.0000278029.33949.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Riley WJ, Bender K, Lownik E. Public health department accreditation implementation: Transforming public health department performance. American Journal of Public Health. 2012;102(2):237–242. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shah GH, Beatty K, Leep C. Do PHAB accreditation prerequisites predict local health departments’ intentions to seek voluntary national accreditation? 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Public Health Accreditation Board. http://www.phaboard.org/news-room/accredited-health-departments/. Accessed on Jan. 9. 2017.

- 9.Beatty KE, Mayer J, Elliott M, Brownson RC, Abdulloeva S, Wojciehowski K. Barriers and incentives to rural health department accreditation. J Public Health Management Practice. 2015 doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000264. Published ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yeager VA, Ye J, Kronstadt J, Robin N, Leep C, Beitsch LM. National voluntary public health accreditation: Are more local health departments intending to take part? J Public Health Management Practice. 2015 doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000242. published ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yeager VA, Ferdinand AO, Beitsch LM, Menachemi N. Local public health department characteristics associated with likelihood to participate in national accreditation. Am J Pub Health. 2015;105:1653–1659. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shah GH, Leep C, Ye J, Sellers K, Liss-Levinson R, Williams KS. Public health agencies’ level of engagement in and perceived barriers to PHAB national voluntary accreditation. J Public Health Management Practice. 2015;21(1):107–115. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Joly BM, Booth M, Shaler G, Conway A. Quality improvement learning collaboratives in public health: Findings from a multisite case study. J Public Health Management Practice. 2012;18(1):87–94. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0b013e3182367db1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gillen SM, McKeever J, Edwards KF, Thielen L. Promoting quality improvement and achieving measurable change: The lead states initiative. J Public Health Manag Practice. 2010;16(1):55–60. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0b013e3181bedb5d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thielen L, Leff M, Corso L, Monteiro E, Fisher LS, Pearsol J. A study of incentives to support and promote public health accreditation. J Public Health Management Practice. 2014;20(1):98–103. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0b013e31829ed746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beitsch LM, Landrum LB, Chang C, Wojciehowski K. Public health laws and implications for a national accreditation program: Parallel roadways without intersection? J Public Health Management and Practice. 2007;13(4):383–387. doi: 10.1097/01.PHH.0000278032.87314.6d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Livingood WC, Morris M, Sorensen B, Chapman K, Rivera L, Beitsch L, et al. Revenue sources for essential services in Florida: Findings and implications for organizing and funding public health. J Public Health Management Practice. 2013;19(4):371–378. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0b013e318269e41c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shah GH, Beatty K, Leep C. Do PHAB accreditation prerequisites predict local health departments’ intentions to seek voluntary national accreditation? Frontiers in Public Health Services and Systems Research. 2013;2(3):4. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davis MV, Cannon MM, Stone DO, Wood BW, Reed J, Baker EL. Informing the nation public health accreditation movement: Lessons from North Carolina’s accredited local health departments. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(9):1543–1548. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Riley WJ, Lownik EM, Scutchfield FD, Mays GP, Corso LC, Beitsch LM. Public health department accreditation: Setting the research agenda. Am J Prevent Med. 2012;42(3):263–271. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Trust for America’s Health. Key Health Data about Indiana. Accessed Feb. 11, 2015. http://healthyamericans.org/states/?stateid=IN#section=3,year=2013,code=undefined.

- 22.Meyerson BE, Barnes PR, King J, Halverson P, Degi L, Polmanski HF. Measuring accreditation activity and progress: Findings from a survey of Indiana local health departments. Public Health Reports. 2015;130(5):447–452. doi: 10.1177/003335491513000507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meyerson BE, King J, Comer K, Liu SS, Miller L. It’s not just a yes or no answer: Expression of local health department accreditation. Frontiers in Public Health. 2016;4(21):1–7. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2016.00021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implementation Science. 2009 doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50. http://www.implementationscience.com/content/4/1/50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Hambrick DC, Mason PA. Upper echelons: the organization as a reflection of its top managers. Academy of Management Review. 1984;9(2):193–206. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu SS, Lin CY. Building customer capital through knowledge management processes in the health care context. Health Care Management Review. 2007;32(2):92–101. doi: 10.1097/01.HMR.0000267786.94437.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Govindarajan V. Implementing competitive strategies at the business unit level: implications of matching managers to strategies. Strategic Management Journal. 1989;10:251–269. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu SS, Lu JR, Guo KL. Using a social entrepreneurial approach to enhance the financial and social value of health care organizations. Journal of Health Care Finance. 2014;40(3):31–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Luo X, Griffith DA, Liu SS, Shi YZ. The effects of customer relationships and social capital on firm performance: A Chinese business illustration. Journal of International Marketing. 2004;12(4):25–45. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pennings J. Measures of organizational structure: a methodological note. The American Journal of Sociology. 1973;79(3):686–704. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aiken M, Hage J. Organizational interdependence and intra-organizational structure. American Sociological Review. 1968;33(6):912–930. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Child J. Organizational structure, environment and performance: the role of strategic choice. Sociology. 1972;6:1–22. doi: 10.1177/003803857200600101. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.DiMaggo PJ, Powell W. The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review. 1983;48(2):147–160. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lund DB Organizational culture and job satisfaction. Journal of Business and Industrial Marketing. 2003;18(3):219–236. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alvesson M. On the popularity of organizational culture. Acta Sociologica. 1990;33(1):31–49. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schein EH. Working Paper 3831. MIT Sloan School Management; Cambridge, MA: 1995. Organizational and managerial culture as a facilitator or inhibitor of organizational transformation. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mehta S, Krishnam VR. Impact of organizational culture and influence tactics on transformational leadership. Journal of Management and Labor Studies. 2004;29(4):281–290. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lopez SP, Peon JMM, Ordas CJV. Managing knowledge: The link between culture and organizational learning. Journal of Knowledge Management. 2004;8(6):93–104. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dodek P, Cahill NE, Heyland DK. The relationship between organizational culture and implementation of clinical practice guidelines: A narrative review. Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition. 2010;34(6):669–674. doi: 10.1177/0148607110361905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rashid MZA, Sambasiavn M, AdbulRahman A. The influence of organizational culture on attitudes toward organizational change. Leadership & Organizational Development Journal. 2004;25(2):161–179. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Luo X, Hsu MK, Liu SS. The moderating role of institutional networking in the customer orientation-trust/commitment-performance causal chain in China. J of the Academy of Marketing Science. 2008;36:202–214. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wallace H, Tilson H, Carlson VP, Valasek T. Instrumental roles of governance in accreditation: Responsibilities of public health governing entities. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice. 2014;20(1):61–63. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0b013e3182a45141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Eisenhardt KM. Building theories from case study research. Academy of Management Review. 1989;14(4):532–550. [Google Scholar]

- 44.County Health Rankings & Roadmaps. Indiana. http://www.countyhealthrankings.org/app/indiana/2016/rankings/outcomes/overall. Published 2011. Accessed 2016.

- 45.Harris JK, Mueller NL. Policy activity and policy adoption in rural, suburban and urban local health departments. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2013;19(2):E1–E8. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0b013e318252ee8c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Meyerson BE, Sayegh MA. State Size and Government Level Matter Most: A Structural Equation Model of Local Health Department Policy Behaviors. J Public Health Management Practice. 2016;22(2):157–163. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000244. (Published online in 2015) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]