Abstract

This study examined whether working memory (WM), inattentive symptoms, and/or hyperactive/impulsive symptoms significantly contributed to academic, behavioral, and global functioning in 8-year-old children. One-hundred-sixty 8-year-old children (75.6% male), who were originally recruited as preschoolers, completed subtests from the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children–Fourth Edition, Integrated and Wechsler Individual Achievement Test–Second Edition to assess WM and academic achievement, respectively. Teachers rated children’s academic and behavioral functioning using the Vanderbilt Rating Scale. Global functioning, as rated by clinicians, was assessed by the Children’s Global Assessment Scale. Multiple linear regressions were completed to determine the extent to which WM (auditory-verbal and visual-spatial) and/or inattentive and hyperactive/impulsive symptom severity significantly contributed to academic, behavioral, and/or global functioning. Both auditory-verbal and visual-spatial WM but not ADHD symptom severity, significantly and independently contributed to measures of academic achievement (all p < .01). In contrast, both WM and inattention symptoms (p < .01), but not hyperactivity-impulsivity (p > .05) significantly contributed to teacher-ratings of academic functioning. Further, inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity (p < .04), but not WM (p > .10) were significantly associated with teacher-ratings of behavioral functioning and clinician-ratings of global functioning. Taken together, it appears that WM in children may be uniquely related to academic skills, but not necessarily to overall behavioral functioning.

Keywords: attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, working memory, academic achievement, school-aged children

Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is a highly prevalent neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by developmentally inappropriate levels of inattention and/or hyperactivity/impulsivity which cause significant functional impairment in multiple settings (American Psychiatric Association, 2013; Polanczyk, de Lima, Horta, Biderman, & Rohde, 2007; Visser et al., 2014; Walkup, Stossel, & Rendleman, 2014). Further, as compared to their typically-developing peers, children with ADHD have been shown to perform poorly on an array of neurocognitive tests (Ware et al., 2012; Willcutt, Doyle, Nigg, Faraone, & Pennington, 2005). Among the many cognitive deficits that have been linked to ADHD, considerable attention has focused on working memory (WM) impairments (Kasper, Alderson, & Hudec, 2012; Martinussen, Hayden, & Hogg-Johnson, 2005). WM is a temporary storage system in which an individual can maintain, update, and/or manipulate information over brief periods in order to guide ongoing behavior and cognitive activities (Baddeley & Hitch, 1974). Substantial research has demonstrated that, as a group, children with ADHD have poorer WM as compared to their typically-developing peers (Bedard, Martinussen, Ickowicz, & Tannock, 2004; de Jong et al., 2009; Gau, Chiu, Shang, Cheng, & Soong, 2009; Kasper et al., 2012; Kerns, McInerney, & Wilde, 2001; Martinussen et al., 2005). Some data have suggested that ADHD probands manifest deficits in auditory-verbal and visual-spatial modalities (Fair, Bathula, Nikolas, & Nigg, 2012; Gau & Chiang, 2013; McInnes, Humphries, Hogg-Johnson, & Tannock, 2003; Nikolas & Nigg., 2013), yet other studies have indicated differentially greater weakness in visual-spatial relative to auditory-verbal WM (Martinussen et al. 2005; Simone, Bedard, Marks, & Halperin, 2016).

Despite group-level differences in WM between children with and without ADHD, the disorder is characterized by considerable phenotypic and neurocognitive heterogeneity (Nigg et al., 2005). Castellanos and Tannock (2002) posited that WM, among other neurocognitive processes, might represent a distinct endophenotype of ADHD, which may help to parse the vast heterogeneity of the disorder. A recent empirical study investigated the role of different executive functions as potential endophenotypes for ADHD by comparing typically-developing children to unaffected siblings of youth with ADHD and found that WM weaknesses were evident in some, but not nearly all of the unaffected siblings (Nikolas & Nigg, 2015). These findings suggest that WM weaknesses could represent a potential endophenotype for a subset of children with ADHD, however other children with the disorder may exhibit different neurocognitive deficits (or potentially none).

While WM deficits are clearly evident in some children with ADHD, the etiological role of WM in ADHD has remained elusive. Barkley (1997) has suggested that WM deficits in ADHD are largely secondary to a core deficit in inhibitory control. Others have suggested that WM weaknesses are characteristic of only a subgroup of children with the disorder (Castellanos & Tannock, 2002; Nikolas & Nigg, 2015). In contrast, Rapport and colleagues (Alderson, Rapport, Hudec, Sarver, & Kofler, 2010; Rapport, Chung, Shore, & Isaacs, 2001) have hypothesized that impaired WM is the core underlying neurocognitive deficit leading to the dysregulated behavior typical of children with ADHD (i.e., deficits in attention and behavioral inhibition). While cross-sectional studies supporting their model have identified a possible mediating role of WM vis-à-vis ADHD and response inhibition (Alderson et al., 2010), and ADHD and activity level (Rapport et al., 2009), a more definitive demonstration of mediation would require a longitudinal design (Selig & Preacher, 2009). Rapport and colleagues have also suggested that WM impairments are evident in as many as 81–98% of children with ADHD (Kasper et al., 2012; Rapport, Orban, Kofler, & Friedman, 2013), yet the methodological approach employed also resulted in 50% of typically-developing children falling below the “average” score. Taken together, there is evidence to suggest that many children with ADHD present with WM weaknesses. However, due to inconsistencies in the literature, it remains unclear how many children with the disorder actually have deficient WM, and the extent to which this specific neurocognitive weakness contributes to difficulties in daily functioning.

In addition to poor WM, relative to their typically-developing peers, children and adolescents with ADHD present with significantly higher rates of academic underachievement (DeShazo, Lyman, & Grofer, 2002; Hinshaw, 1992), as well as school drop-out (Loe & Feldman, 2007; Trampush, Miller, Newcorn, & Halperin, 2009). It has been estimated that 20 – 50% of children with ADHD meet criteria for a learning disability (LD; Pastor & Reuben, 2008; Pliszka, 2000). Yet, many children with ADHD have been shown to have poor academic functioning, even in the absence of a frank LD. As WM has also been linked to poor academic achievement in children (regardless of ADHD diagnosis; Alloway & Alloway, 2010), some investigators (Rogers, Hwang, Toplak, Weiss, & Tannock, 2011; Sjowall & Thorell, 2014) have begun to examine whether WM ability mediates the relation between ADHD symptoms and academic outcomes in school-aged children. Specifically, Rogers and colleagues (2011) found that in adolescents with ADHD, auditory-verbal and visual-spatial WM partially mediated the relation between inattentive symptoms and performance on tests of reading, but not mathematics, achievement. Similarly, Sjowall and Thorell (2014) found that WM (collapsed across auditory-verbal and visual-spatial tasks) partially mediated the relation between ADHD symptoms and teacher ratings of children’s math and language skills. Given the heterogeneity of WM impairment in samples of children with ADHD, it is still unclear whether ADHD and WM ability uniquely contribute to poor academic outcomes. Further, there have been inconsistent findings regarding the relations between ADHD, WM, and mathematics outcomes, which could be due to the different academic outcome assessments used (i.e., tests versus teacher ratings). Thus, it is important to examine within a single sample of children whether ADHD symptoms and WM ability both, or differentially, contribute to objective tests and subjective ratings of academic achievement.

To date, two studies (Alloway, Gathercole, & Elliott, 2010; Holmes et al., 2014) have compared children with ADHD to non-ADHD children with low WM and found that the groups did not appear to differ on tests of academic achievement. Alloway and colleagues (2010) divided their sample based on teacher ratings of WM (irrespective of ADHD diagnosis) and found that the low WM group performed substantially poorer on all academic achievement measures relative to those with average WM, but that the groups did not differ on teacher ratings of classroom functioning. In contrast, Holmes and colleagues (2014) found that teachers rated children with ADHD as having significantly more hyperactivity and impulsivity than their non-ADHD low WM peers. Based on these findings, it would appear that WM is contributing to poorer academic achievement in children (regardless of ADHD status), and the contribution of WM to behavioral dysfunction in children with or without ADHD is unclear. Further, it remains uncertain whether both ADHD symptom domains (inattentive and hyperactive/impulsive), as well as WM ability significantly contribute to poorer academic and behavioral functioning in school-aged children.

The present study examined whether WM ability (auditory-verbal and visual-spatial), inattentive symptoms, and/or hyperactive/impulsive symptoms significantly contribute to academic, behavioral, and global functioning among 8-year-old children. Children completed tests of academic achievement; teachers rated the children on academic and behavioral functioning; and clinicians judged overall global functioning. As findings regarding distinct associations of modality-specific WM processes and academic abilities are mixed (Brady, 1991; Jorm, 1983; McLean & Hitch, 1999; Schuchardt, Maehler, & Hasselhorn, 2008; Swanson & Sachse-Lee, 2001), we made no specific hypotheses regarding differential relations between WM modalities and academic achievement. Therefore, irrespective of modality, we hypothesized that:

WM ability, but not ADHD symptom severity, would be significantly associated with all measures of academic functioning (objective and subjective).

Inattentive and hyperactive/impulsive symptom severity, but not WM ability, would significantly predict teacher ratings of behavioral functioning and clinician ratings of global functioning.

If these hypotheses are supported, it would suggest a double dissociation whereby WM ability would be linked to learning and academic problems rather than behavioral functioning in school-aged children; and inattentive and hyperactive/impulsive symptoms, but not WM ability, would be more closely associated with poorer behavioral functioning.

Method

Participants

The participants in the current study were part of a larger longitudinal investigation (n = 216) in which preschoolers were initially recruited at 3–4 years old via screenings at local preschools and direct referrals from preschools and community mental health providers. All were rated by parents and teachers using the ADHD-Rating Scale IV (ADHD-RS; DuPaul, Power, Anastopoulus, & Reid, 1998) and categorized as “hyperactive/inattentive” (i.e., “at-risk” for developing ADHD) or “typically-developing.” Those rated as having at least six symptoms (i.e., rated as occurring often or very often) of either inattention and/or hyperactivity/impulsivity by a combination of parent and teacher reports were considered hyperactive/inattentive; those rated as having fewer than three symptoms in both domains by parents and teachers were classified as typically-developing. Recruitment was set such that approximately twice as many children were entered into the hyperactive/inattentive group (n = 140) than the typically-developing group (n = 76). At study entry, participants were required to be English-speaking and attending preschool or daycare. Exclusionary criteria were: Full Scale IQ < 80 as assessed by the Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence–Third Edition (WPPSI-III; Wechsler, 2006), systemic medication use (including for ADHD), and presence of a neurological, post-traumatic stress, and/or pervasive developmental disorder. Additional recruitment and selection details for the original sample can be found in Rajendran et al. (2013).

Of the 216 preschoolers initially recruited for the longitudinal study, 160 returned for their 8-year-old evaluation (Mean age = 8.56, SD = 0.31, range = 7.91 – 9.33): 53 were typically-developing at preschool and did not have ADHD at 8-years-old; 11 were typically-developing at preschool and did have ADHD at 8-years old; 21 were at-risk for ADHD at preschool and did not have ADHD at 8-years-old; 75 were at-risk for ADHD at preschool and did have ADHD at 8-years-old. The children who returned for this follow-up evaluation did not differ from those lost to follow-up on any key demographic variables assessed at the initial evaluation, which included age, socioeconomic status (SES), WPPSI-III IQ scores, or parent- and teacher-ratings of ADHD. The 8-year-old evaluation was used in this study largely for practical reasons, as it was the first time in our longitudinal study in which both auditory-verbal and visual-spatial WM were assessed. No additional exclusionary criteria were used at the 8-year-old evaluation.

At 8-years-old the sample was predominantly male (75.6%) and largely middle class, but included youth from a range of socioeconomic backgrounds (see Table 1). The children were of varied racial and ethnic backgrounds: White/Caucasian (58.8%), Other/Mixed Race (18.1%), Asian/Pacific Islander (12.5%), and Black/African-American (10.6%); 70.0% were non-Hispanic (70.0%). ADHD symptom severity and diagnoses were determined using the Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia – Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL; Kaufman, Birmaher, Brent, Rao, & Ryan, 1996), which was administered to a parent or caregiver. Of the children assessed at 8-years-old, 53.8% met criteria for a DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association, 2013) ADHD diagnosis (Inattentive Presentation = 15.6%, Hyperactive/Impulsive Presentation = 5.0%, Combined Presentation = 29.4%, Not Otherwise Specified = 3.8%). Several children in the sample met criteria for internalizing (20.6%) and externalizing disorders (8.8%). In accordance with DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association, 2013), 4.4% (n = 7) of our sample met diagnostic criteria for a specific learning disorder (LD; i.e., having a score falling 1.5 standard deviations or lower than the population mean on any of the academic achievement measures). Of these children, all but one was deemed at-risk for developing ADHD at the baseline evaluation and met diagnostic criteria for ADHD at the 8-year-old evaluation.

Table 1.

Descriptive characteristics of the sample of children at 8-years-old

| Full Sample | Non-ADHD | ADHD | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean (SD) | Range | N | Mean (SD) | N | Mean (SD) | T | |

| Age in years | 160 | 8.56 (0.31) | 7.91 – 9.33 | 74 | 8.54 (0.30) | 86 | 8.57 (0.31) | −0.62 |

| Socioeconomic Status (SES) | 160 | 63.91 (17.94) | 20 – 97 | 74 | 68.85 (15.92) | 86 | 59.65 (18.56) | 3.38† |

| WPPSI-III Full Scale IQ at 3–4 years old | 160 | 107.35 (13.41) | 80 – 144 | 74 | 112.11 (12.52) | 86 | 103.26 (12.85) | 4.40‡ |

| Working Memory Index (WMI) | 157 | 99.68 (13.99) | 65 – 135 | 73 | 105.04 (12.94) | 84 | 95.02 (13.25) | 4.79‡ |

| Spatial Span Averaged Scaled Score | 160 | 10.60 (2.95) | 2 – 18 | 74 | 11.61 (2.50) | 86 | 9.74 (3.04) | 4.27‡ |

| KSADS Inattentive Severity Score | 160 | 9.42 (6.57) | 0 – 18 | 74 | 3.15 (3.16) | 86 | 14.81 (2.90) | −24.20‡ |

| KSADS Hyperactive/Impulsive Severity Score | 160 | 8.20 (6.04) | 0 – 18 | 74 | 3.12 (3.36) | 86 | 12.57 (4.10) | −16.01‡ |

| WIAT-II Word Reading | 160 | 112.90 (10.80) | 65 – 131 | 74 | 115.51 (8.16) | 86 | 110.65 (12.24) | 2.99† |

| WIAT-II Reading Comprehension | 158 | 108.80 (12.95) | 65 – 150 | 74 | 112.68 (11.90) | 84 | 105.38 (12.93) | 3.69‡ |

| WIAT-II Pseudoword Decoding | 160 | 110.57 (12.67) | 75 – 130 | 74 | 113.24 (10.70) | 86 | 108.28 (13.79) | 2.56 |

| WIAT-II Numerical Operations | 159 | 108.88 (15.13) | 52 – 149 | 74 | 113.36 (13.23) | 85 | 104.98 (15.67) | 3.66‡ |

| WIAT-II Spelling | 158 | 114.15 (16.25) | 57 – 151 | 74 | 118.27 (14.74) | 84 | 110.52 (16.73) | 3.09† |

| NICHQ Classroom Academic Functioning | 126 | 8.67 (2.86) | 1 – 15 | 50 | 7.26 (2.28) | 72 | 9.79 (2.75) | −5.53‡ |

| NICHQ Classroom Behavioral Functioning | 126 | 14.72 (5.91) | 1 – 25 | 50 | 11.28 (4.58) | 72 | 17.31 (5.38) | −6.65‡ |

| Children’s Global Assessment Scale (CGAS) | 160 | 58.49 (16.96) | 30 – 92 | 74 | 73.73 (11.69) | 86 | 45.37 (6.67) | 18.44‡ |

| Percentages (N = 160) | Percentages (N = 74) | Percentages (N = 86) | X2 | |||||

| Gender (% males) | 75.6 | 70.3 | 80.2 | 2.14 | ||||

| Race | 11.97† | |||||||

| White/Caucasian (%) | 58.8 | 52.7 | 64.0 | |||||

| Black/African-American (%) | 10.6 | 5.4 | 15.1 | |||||

| Asian/Pacific Islander (%) | 12.5 | 20.3 | 5.8 | |||||

| Other/Mixed Race (%) | 18.1 | 21.6 | 15.1 | |||||

| Ethnicity | 1.23 | |||||||

| Non-Hispanic (%) | 70 | 74.3 | 66.3 | |||||

| Hispanic (%) | 30 | 25.7 | 33.7 | |||||

SD = Standard Deviation; KSADS = Kiddie-Schedule of Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia; WIAT-II = Wechsler Individual Achievement Test, Second Edition; NICHQ = National Institute of Children’s Healthcare Quality Vanderbilt Assessment Scale, Teacher Version

p < 0.01

p<0.001

Materials

Diagnostic Measures

Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia – Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL; Kaufman et al., 1996)

Parents/caregivers were administered the K-SADS-PL by well-trained psychology graduate students or postdoctoral fellows who were supervised by a licensed psychologist to determine diagnoses and ADHD symptom severity. Each symptom was recoded from the original K-SADS-PL scale (1 = not present, 2 = subthreshold, and 3 = threshold) to a 0 – 2 scale. Thus, for each symptom domain (inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity), total severity scores could range from 0 to 18. These severity scores for each ADHD symptom domain were used in the final analyses.

Working Memory Measures

Auditory-verbal WM was assessed using the Working Memory Index (WMI) of the WISC-IV Integrated (Kaplan et al., 2004). This index is comprised of the Digit Span and Letter-Number Sequencing subtests. The Digit Span subtest is separated into two parts: Forward and Backward. For the Forward condition, children listen and repeat back series of numbers, whereas in the Backward condition children report them in the reverse order. For both conditions the task consists of two trials for each span length that increases in length until the child fails both trials within a set or finishes the last sequence of the task. For Letter-Number Sequencing, children listen to a series of numbers and letters and are instructed to first recite the numbers in sequential order and then the letters in alphabetical order. The Letter-Number Sequencing task consists of three trials per span length that increase in length until the child fails all three trials within a set or completes the final sequence of the task. The WMI at 8-years-old has been shown to have strong internal consistency (r = 0.91) and test-retest reliability (r = 0.84; Kaplan et al., 2004).

Visual-spatial WM was assessed using the Spatial Span subtest from the WISC-IV Integrated that contains two conditions, Spatial Span Forward and Spatial Span Backward. In Spatial Span Forward, children watch the examiner tap a series of blocks and then tap the blocks in the same order as was presented. In Spatial Span Backward, children tap them in the reverse order to what was presented. Similar to the Digit Span subtest, for both Spatial Span conditions each span length contains two trials and ends when an individual fails both trials of a set or finishes the last sequence of the task. As the Spatial Span subtest does not calculate a standardized score for the total collapsed performance on the forward and backward conditions, we averaged the individual scaled scores for these two conditions to arrive at a combined scaled score of visual-spatial WM.

Within our sample, the WMI and averaged Spatial Span scaled scores demonstrated a moderate, positive correlation (r = 0.576, p < .001), suggesting some overlap between these measures, but that they are relatively distinct from each other. Among those who did and did not meet criteria for ADHD, 34.5% and 13.7% fell below the 25%ile on the WMI (X2 = 9.07, p = .003) and 24.4% and 5.5% fell below the 25%ile on the Spatial Span tests (X2 = 10.91, p = .001), respectively. Thus, more children with ADHD had WM difficulties relative to controls, but even with this liberal cut score, the majority of children with ADHD had normatively intact WM ability.

Academic Achievement Measures

Wechsler Individual Achievement Tests – Second Edition (WIAT-II; Wechsler, 2005)

Children were administered selected subtests from the WIAT-II (referenced below) to yield an objective assessment of academic achievement. Each subtest is administered separately with its own instructions, which include reversal and discontinue rules. For each subtest, raw scores are calculated and then transformed into individual standard scores (M = 100, SD = 15).

Word Reading

The Word Reading subtest requires individuals to read a series of American English words. The task begins with simpler words and progresses in word complexity and is discontinued when the participant is unable to accurately read six consecutive words or the final word of the test is read.

Pseudoword Decoding

This subtest requires individuals to read a series of nonsense words phonetically. The task begins with simpler nonsense words and progresses in complexity. The task is discontinued when the participant is unable to accurately read six consecutive nonsense words or the final nonsense word of the test is read.

Spelling

The Spelling subtest requires individuals to listen to sentences read aloud by an examiner, and to write a specified target word from the sentence. The task begins with simpler words and progresses in word complexity. The task is discontinued when the participant is unable to accurately spell six consecutive words or the final word of the test is administered.

Reading Comprehension

This subtest requires individuals to read a series of short sentences and passages and then answer questions about what they previously read. Participants begin the task based on their current grade level (or most recent grade level completed) and the task is discontinued when the participant reaches the final sentence or passage within their grade section.

Numerical Operations

The Numerical Operations subtest requires individuals to complete various mathematical problems (e.g., addition, subtraction, percentages, fractions, etc.) that increase in complexity as the task progresses. The task is discontinued when the participant completes six consecutive problems incorrectly or when the final problem is reached.

Table 2 shows correlations among the WM, academic achievement, and ADHD symptom severity scores. As shown in Table 2, all of the WM, academic achievement measures, preschool IQ, and ADHD symptom domains are moderately correlated; thus suggesting that while there is some overlap between these variables, they are all relatively distinct from each other.

Table 2.

Pearson Bivariate Correlations for WM, preschool IQ, academic achievement measures, and symptom severity scores

| Spatial Span Averaged Scale Score | WPPSI FSIQ | Word Reading | Reading Comprehension | Psuedoword Decoding | Numerical Operations | Spelling | Inattentive Severity Score | Hyperactive/Impulsive Severity Score | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WMI | .576** | .533** | .563** | .500** | .533** | .591** | .555** | −.375** | −.241** |

|

|

|||||||||

| Spatial Span Averaged Scaled Score | 1 | .414** | .367** | .346** | .309** | .459** | .360** | −.388** | −.304** |

|

|

|||||||||

| WPPSI-III FSIQ | 1 | .378** | .538** | .319** | .459** | .284** | −.309** | −.205* | |

|

|

|||||||||

| Word Reading | 1 | .583** | .860** | .576** | .803** | −.213** | −.195* | ||

|

|

|||||||||

| Reading Comprehension | 1 | .507** | .550** | .503** | −.247** | −.204* | |||

|

|

|||||||||

| Psuedoword Decoding | 1 | .552** | .753** | −.226** | −.191* | ||||

|

|

|||||||||

| Numerical Operations | 1 | .617** | −.238** | −.158* | |||||

|

|

|||||||||

| Spelling | 1 | −.256** | −.161* | ||||||

|

|

|||||||||

| Inattentive Severity Score | 1 | .759** | |||||||

|

|

|||||||||

Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed).

Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

School/Classroom Functioning Measure

National Institute for Children’s Health Quality (NICHQ) Vanderbilt Assessment Scale – Teacher Version (Wolraich et al., 2003)

The NICHQ was used to assess children’s overall school/classroom functioning. Teachers completed these rating scales, which probed for the student’s performance in mathematics, reading, and written expression. Teachers also rated the students on their behavioral functioning in the classroom: 1) relationship with peers, 2) following directions, 3) disrupting the classroom, 4) assignment completion, and 5) organizational skills. For each of the above academic and behavioral dimensions, teachers rated students on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = excellent, 2 = above average, 3 = average, 4 = somewhat of a problem, and 5 = problematic). For our analyses, we used the sum of each of these scales (i.e., three items of academic functioning and five items of behavioral functioning) as our outcome measure. For our sample, coefficient alphas for the teacher-reported academic functioning and behavioral functioning scales were 0.81 and 0.88, respectively.

Global Functioning Measure

Following a comprehensive evaluation, which included the K-SADS-PL interview with parents and rating scale data from parents and teachers, each child’s case was presented to a group of clinicians who independently rated the child on the Children’s Global Assessment Scale (CGAS; Schaffer et al., 1983) based on the child’s lowest level of functioning over the previous evaluation year. Scores on this scale range from 1 to 100, with scores below 60 typically representing impaired functioning (Shaffer et al., 1983). Median scores across clinicians were calculated for each child, and this score was used in the final analyses. Across the 160 participants assessed at age 8, the number of clinician-raters varied from 4 through 13. Reliability among raters was calculated separately for each number of raters (except 4 and 13 where there was only one case each) using intra-class correlations (ICC). Reliability was excellent with ICC values ranging from 0.938 – 0.976.

Procedure

A member of the research team tested child participants individually while a different evaluator interviewed the child’s parent/caregiver using the K-SADS-PL. Both evaluators were blind to the child’s prior diagnostic status. For those children who were prescribed stimulant medication (n = 30, 18.8%), parents were instructed to withhold medication on the day of the evaluation. The full evaluation lasted approximately 2–3 hours, during which children completed the academic tests, WM tasks, as well as other neuropsychological measures. Children were given a small prize at the end of the session for participating in the study. Parents received compensation for their time and expenses associated with study participation. This study was approved by the institutional review board (IRB) of the affiliated institution. Following a description of the study and their rights as participants, parents/caregivers signed informed consent, and children gave verbal assent.

Statistical Analyses

Multiple linear regressions were conducted to assess whether WM ability and ADHD symptom severity (inattentive and hyperactive/impulsive symptoms) significantly contributed to each outcome variable (i.e., academic achievement tests, teacher-rated academic functioning, teacher-rated behavioral functioning, and clinician-rated global functioning). As SES has been shown to be a strong predictor of academic outcomes (Sirin, 2005), as well as health and social-emotional functioning in children (Bradley & Corwyn, 2002), it was entered into the first step of each model to control for its effects on the dependent variables.

For the second step, WM ability (either auditory-verbal or visual-spatial), and K-SADS inattentive and hyperactive/impulsive symptom severity were added into the model to determine their individual associations with the outcome variables. For the final step, interaction variables between centered WM x inattentive symptoms and centered WM x hyperactive/impulsive symptoms were added into the model.

The first set of regression analyses was conducted with auditory-verbal WM (AVWM) ability, and then a second set of analyses using the same statistical procedures was conducted with visual-spatial WM (VSWM) ability.

Results

Auditory-Verbal WM (see Table 3)

Table 3.

Multiple Linear Regressions with Auditory-Verbal WM – Final Model

| Academic Achievement Tests | β | t | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Word Reading | |||

| SES | 0.206 | 2.912 | 0.004 |

| WMI | 0.519 | 7.124 | <0.001 |

| K-SADS Inattentive Symptom Severity | 0.091 | 0.838 | 0.404 |

| K-SADS Hyperactive/Impulsive Symptom Severity | −0.081 | −0.764 | 0.446 |

| WMI x K-SADS Inattentive Symptom Severity | −0.049 | −0.496 | 0.620 |

| WMI x K-SADS Hyperactive/Impulsive Symptom Severity | 0.021 | 0.206 | 0.837 |

| Reading Comprehension | |||

| SES | 0.284 | 3.956 | <0.001 |

| WMI | 0.397 | 5.376 | <0.001 |

| K-SADS Inattentive Symptom Severity | −0.041 | −0.376 | 0.707 |

| K-SADS Hyperactive/Impulsive Symptom Severity | −0.007 | −0.066 | 0.947 |

| WMI x K-SADS Inattentive Symptom Severity | 0.035 | 0.343 | 0.732 |

| WMI x K-SADS Hyperactive/Impulsive Symptom Severity | 0.101 | 1.003 | 0.317 |

| Pseudoword Decoding | |||

| SES | 0.178 | 2.441 | 0.016 |

| WMI | 0.496 | 6.596 | <0.001 |

| K-SADS Inattentive Symptom Severity | 0.038 | 0.343 | 0.732 |

| K-SADS Hyperactive/Impulsive Symptom Severity | −0.052 | −0.473 | 0.637 |

| WMI x K-SADS Inattentive Symptom Severity | −0.015 | −0.150 | 0.881 |

| WMI x K-SADS Hyperactive/Impulsive Symptom Severity | −0.049 | −0.473 | 0.637 |

| Numerical Operations | |||

| SES | 0.191 | 2.764 | 0.006 |

| WMI | 0.525 | 7.367 | <0.001 |

| K-SADS Inattentive Symptom Severity | −0.025 | −0.239 | 0.812 |

| K-SADS Hyperactive/Impulsive Symptom Severity | 0.047 | 0.460 | 0.646 |

| WMI x K-SADS Inattentive Symptom Severity | −0.082 | −0.840 | 0.402 |

| WMI x K-SADS Hyperactive/Impulsive Symptom Severity | 0.132 | 1.348 | 0.180 |

| Spelling | |||

| SES | 0.156 | 2.157 | 0.033 |

| WMI | 0.488 | 6.539 | <0.001 |

| K-SADS Inattentive Symptom Severity | −0.050 | −0.456 | 0.649 |

| K-SADS Hyperactive/Impulsive Symptom Severity | 0.044 | 0.412 | 0.681 |

| WMI x K-SADS Inattentive Symptom Severity | −0.157 | −1.547 | 0.124 |

| WMI x K-SADS Hyperactive/Impulsive Symptom Severity | 0.113 | −1.107 | 0.270 |

| Teacher Ratings | |||

| Academic Functioning | |||

| SES | −0.137 | −1.674 | 0.097 |

| WMI | −0.368 | −4.127 | <0.001 |

| K-SADS Inattentive Symptom Severity | 0.334 | 2.660 | 0.009 |

| K-SADS Hyperactive/Impulsive Symptom Severity | −0.089 | −0.738 | 0.462 |

| WMI x K-SADS Inattentive Symptom Severity | 0.041 | 0.358 | 0.721 |

| WMI x K-SADS Hyperactive/Impulsive Symptom Severity | −0.033 | −0.278 | 0.782 |

| Behavioral Functioning | |||

| SES | −0.060 | −0.731 | 0.466 |

| WMI | −0.035 | −0.389 | 0.698 |

| K-SADS Inattentive Symptom Severity | 0.355 | 2.811 | 0.006 |

| K-SADS Hyperactive/Impulsive Symptom Severity | 0.249 | 2.041 | 0.044 |

| WMI x K-SADS Inattentive Symptom Severity | −0.64 | −0.554 | 0.581 |

| WMI x K-SADS Hyperactive/Impulsive Symptom Severity | 0.083 | 0.693 | 0.490 |

| Clinician Rated Children’s Global Assessment Scale | |||

| SES | 0.075 | 1.694 | 0.092 |

| WMI | 0.069 | 1.526 | 0.129 |

| K-SADS Inattentive Symptom Severity | −0.604 | −8.923 | <0.001 |

| K-SADS Hyperactive/Impulsive Symptom Severity | −0.262 | −3.979 | <0.001 |

| WMI x K-SADS Inattentive Symptom Severity | 0.017 | 0.281 | 0.779 |

| WMI x K-SADS Hyperactive/Impulsive Symptom Severity | −0.006 | −0.090 | 0.928 |

Bold denotes significant predictor variables

Academic Achievement Tests

Word Reading

SES and AVWM significantly contributed to Word Reading, accounting for 12.5% and 23.9% of the variance, respectively. Inattentive and hyperactive/impulsive symptom severity, as well as the two interaction terms, was not significantly related to Word Reading scores.

Reading Comprehension

SES and AVWM were significantly associated with Reading Comprehension and accounted for 17.5% and 16.3% of the variance, respectively. Neither ADHD symptom domain nor their interactions with AVWM significantly predicted Reading Comprehension scores.

Pseuodoword Decoding

Again, SES and AVWM significantly contributed to Pseudoword Decoding accounting for 9.8% and 22.3% of the variance, respectively. None of the other predictor variables were significantly related to Pseudoword Decoding scores.

Numerical Operations

SES and AVWM were significantly related to Numerical Operations scores and accounted for 11.7% and 26.9% of the variance, respectively. Inattentive and hyperactive/impulsive symptom severity, as well as their interactions with AVWM, were not significantly related to Numerical Operations.

Spelling

Similar to the other WIAT-II subtests, SES and AVWM significantly contributed to Spelling scores accounting for 8.8% and 24.4% of the variance, respectively. Neither of the ADHD symptom domain nor their interactions with significantly predicted Spelling scores.

School Functioning as Rated by Teachers

As shown in Table 3, after accounting for SES, AVWM and inattentive symptom severity significantly contributed to classroom academic functioning accounting for 20.4% and 6.1% of the variance, respectively. None of the other predictor variables were significantly associated with teacher ratings of academic functioning. In contrast, after accounting for SES, inattentive symptom severity and hyperactive/impulsive symptom severity were significantly associated with classroom behavioral functioning, in which inattentive symptom severity accounted for 28.5% of the variance and hyperactive/impulsive symptom severity accounted for an additional 2.9% of the variance. Neither AVWM nor any of the other predictor variables were associated with teacher ratings of behavioral functioning.

Global Functioning as Rated by Clinicians

Similar to teacher ratings of behavioral functioning, both inattentive and hyperactive/impulsive symptom severity significantly contributed to clinician ratings of children’s overall global functioning, in which inattentive symptom severity contributed 64.4% of the variance and hyperactive/impulsive symptom severity contributed an additional 2.6% of the variance.

Visual-Spatial WM (see Table 4)

Table 4.

Multiple Linear Regressions with Visual-Spatial WM – Final Model

| Academic Achievement Tests | β | t | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Word Reading | |||

| SES | 0.303 | 4.019 | <0.001 |

| Spatial Span | 0.303 | 3.852 | <0.001 |

| K-SADS Inattentive Symptom Severity | −0.054 | −0.459 | 0.647 |

| K-SADS Hyperactive/Impulsive Symptom Severity | 0.020 | 0.177 | 0.860 |

| Spatial Span x K-SADS Inattentive Symptom Severity | 0.016 | 0.145 | 0.885 |

| Spatial Span x K-SADS Hyperactive/Impulsive Symptom Severity | −0.011 | −0.102 | 0.919 |

| Reading Comprehension | |||

| SES | 0.346 | 4.752 | <0.001 |

| Spatial Span | 0.228 | 3.033 | 0.003 |

| K-SADS Inattentive Symptom Severity | −0.141 | −1.261 | 0.209 |

| K-SADS Hyperactive/Impulsive Symptom Severity | 0.053 | 0.485 | 0.629 |

| Spatial Span x K-SADS Inattentive Symptom Severity | −0.114 | −1.076 | 0.284 |

| Spatial Span x K-SADS Hyperactive/Impulsive Symptom Severity | 0.264 | 2.531 | 0.012 |

| Pseudoword Decoding | |||

| SES | 0.269 | 3.447 | 0.001 |

| Spatial Span | 0.221 | 2.709 | 0.008 |

| K-SADS Inattentive Symptom Severity | −0.115 | −0.953 | 0.342 |

| K-SADS Hyperactive/Impulsive Symptom Severity | 0.034 | 0.292 | 0.771 |

| Spatial Span x K-SADS Inattentive Symptom Severity | 0.013 | 0.113 | 0.910 |

| Spatial Span x K-SADS Hyperactive/Impulsive Symptom Severity | −0.023 | −0.206 | 0.837 |

| Numerical Operations | |||

| SES | 0.296 | 4.210 | <0.001 |

| Spatial Span | 0.420 | 5.735 | <0.001 |

| K-SADS Inattentive Symptom Severity | −0.132 | −1.216 | 0.226 |

| K-SADS Hyperactive/Impulsive Symptom Severity | 0.143 | 1.355 | 0.177 |

| Spatial Span x K-SADS Inattentive Symptom Severity | −0.090 | −0.869 | 0.386 |

| Spatial Span x K-SADS Hyperactive/Impulsive Symptom Severity | 0.166 | 1.623 | 0.107 |

| Spelling | |||

| SES | 0.243 | 3.162 | 0.002 |

| Spatial Span | 0.274 | 3.410 | 0.001 |

| K-SADS Inattentive Symptom Severity | −0.219 | −1.858 | 0.065 |

| K-SADS Hyperactive/Impulsive Symptom Severity | 0.159 | 1.377 | 0.171 |

| Spatial Span x K-SADS Inattentive Symptom Severity | −0.039 | −0.352 | 0.726 |

| Spatial Span x K-SADS Hyperactive/Impulsive Symptom Severity | 0.082 | 0.739 | 0.461 |

| Teacher Ratings | |||

| Academic Functioning | |||

| SES | −0.226 | −2.819 | 0.006 |

| Spatial Span | −0.257 | −2.862 | 0.005 |

| K-SADS Inattentive Symptom Severity | 0.440 | 3.571 | 0.001 |

| K-SADS Hyperactive/Impulsive Symptom Severity | −0.162 | −1.340 | 0.183 |

| Spatial Span x K-SADS Inattentive Symptom Severity | −0.054 | −0.466 | 0.642 |

| Spatial Span x K-SADS Hyperactive/Impulsive Symptom Severity | 0.027 | 0.236 | 0.814 |

| Behavioral Functioning | |||

| SES | −0.054 | −0.697 | 0.487 |

| Spatial Span | 0.008 | 0.093 | 0.926 |

| K-SADS Inattentive Symptom Severity | 0.357 | 2.973 | 0.004 |

| K-SADS Hyperactive/Impulsive Symptom Severity | 0.264 | 2.240 | 0.027 |

| Spatial Span x K-SADS Inattentive Symptom Severity | 0.001 | 0.009 | 0.993 |

| Spatial Span x K-SADS Hyperactive/Impulsive Symptom Severity | −0.006 | −0.058 | 0.954 |

| Clinician Ratings of Children’s Global Assessment Scale | |||

| SES | 0.074 | 1.750 | 0.082 |

| Spatial Span | 0.034 | 0.783 | 0.435 |

| K-SADS Inattentive Symptom Severity | −0.624 | −9.603 | <0.001 |

| K-SADS Hyperactive/Impulsive Symptom Severity | −0.255 | −4.012 | <0.001 |

| Spatial Span x K-SADS Inattentive Symptom Severity | −0.017 | −0.273 | 0.785 |

| Spatial Span x K-SADS Hyperactive/Impulsive Symptom Severity | 0.102 | 1.665 | 0.098 |

Bold denotes significant predictor variables

Academic Achievement Tests

Word Reading

SES and VSWM significantly contributed to Word Reading, accounting for 12.3% and 10.0% of the variance, respectively. Inattentive and hyperactive/impulsive symptom severity, as well as the two interaction terms were not significantly related to Word Reading scores.

Reading Comprehension

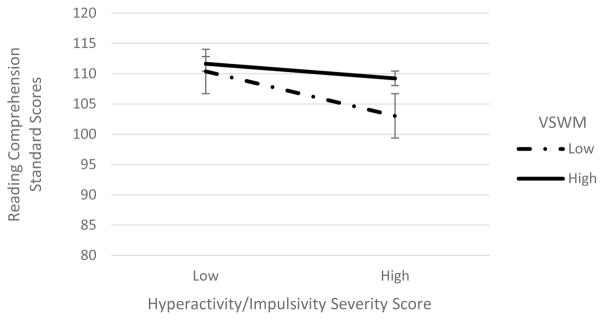

SES and VSWM significantly contributed to Reading Comprehension, accounting for 17.3% and 8.0% of the variance, respectively. In addition, the interaction between VSWM x hyperactive/impulsive symptom severity was significantly associated with Reading Comprehension and accounted for an additional 3.7% of the variance. The nature of this interaction was such that children with higher hyperactive/impulsive symptom severity and lower VSWM had differentially poorer reading comprehension scores when compared to children with low levels of hyperactive/impulsive symptoms irrespective of VSWM and those with high levels of symptoms but stronger VSWM (see Figure 1). None of the other predictor variables were significantly related to Reading Comprehension scores.

Figure 1.

Interaction of hyperactivity/impulsivity symptom severity and visual-spatial working memory on reading comprehension scores. Error bars represent standard deviation (SD).

Pseudoword Decoding

SES and VSWM significantly contributed to Pseudoword Decoding, accounting for 9.8% and 7.0% of the variance, respectively. Inattentive and hyperactive/impulsive symptom severity and the two interaction terms were not significantly related to Pseudoword Decoding scores.

Numerical Operations

SES and VSWM significantly contributed to Numerical Operations, accounting for 12.6% and 19.4% of the variance, respectively. Inattentive and hyperactive/impulsive symptom severity, as well as the two interaction terms were not significantly related to Numerical Operations.

Spelling

SES and VSWM significantly contributed to Spelling, accounting for 8.6% and 11.5% of the variance, respectively. Inattentive and hyperactive/impulsive symptom severity, as well as the two interaction terms were not significantly related to Spelling.

School Functioning as Rated by Teachers

As displayed in Table 4, SES, VSWM, and inattentive symptom severity significantly contributed to classroom academic functioning. After accounting for SES, VSWM and inattentive symptom severity contributed 6.5% and 15.2% of the variance, respectively. Hyperactive/impulsive symptom severity and the two interaction terms were not significantly associated with teacher ratings of academic functioning.

Both inattentive and hyperactive/impulsive symptom severity significantly contributed to classroom behavioral functioning, in which inattentive symptom severity accounted for 29.1% of the variance and hyperactive/impulsive symptom severity accounted for an additional 2.9% of the variance. SES, VSWM, and the two interaction terms were not significantly associated with teacher ratings of behavioral functioning.

Global Functioning as Rated by Clinicians

Both inattentive and hyperactive/impulsive symptom severity significantly contributed to clinician ratings of children’s overall global functioning, in which inattentive symptom severity accounted for 64.6% of the variance and hyperactive/impulsive symptom severity accounted for an additional 2.5% of the variance. SES, VSWM, and the two interaction terms were not significantly related to clinician ratings of children’s global functioning.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge this was the first systematic examination of differential relations of both WM modalities, as well as inattentive and hyperactive/impulsive symptom severity with academic, behavioral, and global functioning in children. As hypothesized, our data indicated that, regardless of which WM modality was assessed (auditory-verbal or visual-spatial), WM ability was significantly associated with all tests of academic achievement, but not with measures of behavior problems or overall global impairment. In contrast, inattentive and hyperactive/impulsive symptoms were associated with measures of behavior problems and global functioning, but not with academic achievement. These findings indicate that compromised WM ability is specifically related to poor academic achievement in children and that the presence of inattentive and hyperactive/impulsive symptoms per se have little to no relation to academic skills. Moreover, while SES was also shown to significantly predict academic achievement, the amount of additional variance accounted for by WM ability across many tests of academic achievement was nearly double what SES accounted for alone.

Interestingly, teacher-ratings of school-based academic performance yielded a somewhat different pattern of predictors. Across both modalities, WM and inattentive symptoms (but not hyperactive/impulsive symptoms) significantly contributed to teachers’ ratings of academic functioning (math, reading, and written expression). This discrepancy between objective test measures and teacher ratings of academic performance may be accounted for by either a difference between skills and performance in children with ADHD, or by negative biases affecting teacher ratings. For the first scenario, several studies (Barkley & Fischer, 2011; Barkley & Murphy, 2010) have shown that children’s performance on tests in an individual setting is often not strongly predictive to real-world environments (e.g., in school) and thus their behavioral dysregulation prevents them from communicating such knowledge in the classroom. Not surprisingly, inattentive symptom severity is more closely linked to classroom performance than hyperactivity/impulsivity, and more closely associated with classroom performance than test performance. Alternatively, teacher-ratings might be affected by halo effects (Abikoff, Courtney, Pelham Jr., & Koplewicz, 1993). Specifically, behavior management issues may elicit a negative bias from classroom instructors, which in turn, influences their ratings of students’ academic functioning.

As hypothesized, we also found that both inattentive and hyperactive/impulsive symptoms, but not WM ability, significantly predicted both teachers’ and clinicians’ ratings of impairment and overall functioning. Specifically, these findings indicate that ADHD symptom severity was significantly associated with teachers rating children as exhibiting more problematic classroom behaviors (e.g., relationships with peers, difficulties organizing tasks and completing assignments, disrupting the classroom environment), and with clinicians rating children as having poorer overall global functioning. If WM was a core deficit in children with ADHD (Rapport et al., 2001), we would expect that WM ability would have also significantly contributed to teachers’ and clinicians’ ratings of these maladaptive behaviors. To the contrary, WM ability did not independently contribute to any measure of behavioral functioning. Thus, WM weaknesses do not appear to be contributing to or acting as a driver of ADHD-like behaviors. Rather, our findings indicate that WM ability, but not ADHD symptoms, is specifically related to academic functioning. This is consistent with findings from Alloway and colleagues (2010) who found that children with poor WM (irrespective of ADHD), were more likely to perform worse on academic measures as compared to their peers with average WM.

While not of primary interest for this study, it is notable that among the children with ADHD in our sample, fewer than half had compromised WM ability even when based on a liberal-cut off criterion (i.e., 25th percentile). These findings are consistent with other reports (Nigg et al., 2005; Nikolas & Nigg, 2015), which suggest that only a minority of children with ADHD present with WM difficulties, again suggesting that WM is not a core underlying deficit of ADHD, but rather points to notable cognitive heterogeneity of the disorder (Castellanos & Tannock, 2002).

It is notable within our data that there were virtually no differences observed on academic, behavioral, and global functioning measures when the analyses were conducted by using children’s auditory-verbal or visual-spatial WM ability. Prior studies have reported closer associations between reading skills and auditory-verbal as compared to visual-spatial WM (Brady, 1991; Jorm, 1983; Schuchardt et al., 2008), and less consistently between math ability and visual-spatial WM (McLean & Hitch, 1999; Schuchardt et al., 2008). Yet our data might suggest that academic achievement is more related to the ability set forth by the central executive component of WM as opposed to the modality-specific slave systems, although this speculation was not directly tested in our study.

Given the current findings linking WM to academic performance, but not ADHD, it is not surprising that WM training, which does improve WM in children with ADHD, seems to have little or no effect on ADHD symptoms (Chacko et al., 2014; Rapport, Orban, Kofler, & Friedman, 2013; van-Dongen-Boomsma, Vollebregt, Buitelaar, & Slaats-Willemse, 2014). We (Simone et al., 2016) previously suggested that cognitive heterogeneity in ADHD might account for the limited efficacy of WM training, and that greater benefits may be obtained if the treatment is limited specifically to those children who have ADHD and poor WM. Our present data suggest that, while WM might improve the acquisition of academic skills in such children (given that WM significantly contributed to performance on academic achievement tests), it would likely have only limited effects on ADHD symptoms as WM did not significantly contribute to school behavioral performance or global functioning. Nevertheless, further research is needed to clarify the extent to which children with ADHD with low or intact WM would benefit from WM training in improving their acquisition and application of academic skills, as well as reducing the manifestation of ADHD symptoms and their impact in real-world settings.

The current study has several notable strengths. First, this is a well-characterized sample of children with and without ADHD who have been followed annually from preschool age through 8-years-old. Second, we used well-established diagnostic measures along with objective measures of auditory-verbal and visual-spatial WM to classify the children. We had a diversity of outcome measures including objective tests, teacher reports, and clinician impressions. Finally, by utilizing a regression approach, we were able to assess for significant and unique contributions of our independent variables on each outcome measure.

Nevertheless, there were some limitations to the current study, which must be considered. First, our sample was comprised of a narrow age range (only 8-year-old children). While this likely reduced variability in findings, caution is warranted when generalizing these results to older or younger children. Second, the scales used to assess teacher judgments of academic functioning, and to a lesser extent classroom behavioral functioning, were comprised of only three and five items, respectively. It is possible that there were too few items to make a valid estimate of each construct we proposed we were assessing. As the sample was originally recruited with strict exclusionary criteria for preschool Full Scale IQ, it likely limited the number of children with truly impaired WM (i.e., ≥ 2 standard deviations below the mean) and may limit generalization of findings to some clinical settings. Also, we did not collect information from the children regarding their actual in-school academic performance (e.g., report cards), and therefore it remains open whether teacher-ratings of academic functioning in the classroom are reliable estimates of their actual school academic performance. Finally, it is important to note that moderate correlations were observed among the WM measures, academic achievement tests, and ADHD symptom domains. While this suggests there is some overlap among these variables, they are also relatively distinct from each other. Nevertheless, while WM was observed to be a significantly unique contributor to academic test achievement, it remains possible that shared aspects of WM and the ADHD symptom domains could be partially responsible for this as well.

Overall, our findings indicate that WM ability is specifically associated with academic achievement across a wide array of skills in children with and without ADHD and not with the presence or severity of ADHD symptoms. Further, severity of ADHD symptoms is unrelated to academic achievement, although symptoms of inattention may have an impact on classroom performance.

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grant R01 MH068286 from NIMH.

This study was funded by the National Institute of Health (NIH grant number: R01 MH068286).

Footnotes

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Ashley N. Simone, The Graduate Center, City University of New York, New York

David J. Marks, Langone Medical Center, New York University, New York

Anne-Claude Bedard, Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, the University of Toronto, Canada.

Jeffrey M. Halperin, Queens College and The Graduate Center, City University of New York, New York

References

- Abikoff H, Courtney M, Pelham WE, Jr, Koplewicz HS. Teachers’ ratings of disruptive behaviors: The influence of halo effects. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1993;21:519–533. doi: 10.1007/BF00916317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alderson RM, Rapport MD, Hudec KL, Sarver DE, Kofler MJ. Competing core processes in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): Do working memory deficiencies underlie behavioral inhibition deficits? Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2010;38:497–507. doi: 10.1007/s10802-010-9387-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alloway TP, Alloway RG. Investigating the predictive roles of working memory and IQ in academic attainment. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 2010;106:20–29. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2009.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alloway TP, Gathercole SE, Elliott J. Examining the link between working memory behavior and academic attainment in children with ADHD. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology. 2010;52:632–636. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2009.03603.x. doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8749.2009.03603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Baddeley A, Gathercole S, Papagno C. The phonological loop as a language learning device. Psychological Review. 1998;105:158–173. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.105.1.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baddeley AD, Hitch G. Working memory. Psychology of Learning and Motivation. 1974;8:47–89. doi: 10.1016/S0079-7421(08)60452-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barkley RA. Behavioral inhibition, sustained attention, and executive function: Constructing a unified theory of ADHD. Psychological Bulletin. 1997;121:65–94. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.121.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkley RA, Fischer M. Predicting impairment in major life activities and occupational functioning in hyperactive children as adults: Self-reported executive function (EF) deficits versus EF tests. Developmental neuropsychology. 2011;36:137–161. doi: 10.1080/87565641.2010.549877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkley RA, Murphy KR. Impairment in occupational functioning and adult ADHD: The predictive utility of executive function (EF) ratings versus EF tests. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology. 2010;25:157–173. doi: 10.1093/arclin/acq014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedard AC, Martinussen R, Ickowicz A, Tannock R. Methylphenidate improves visual-spatial memory in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2004;43:260–280. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200403000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biederman J, Monuteaux MC, Doyle AE, Seidman LJ, Wilens TE, Ferrero F, … Faraone S. Impact of executive function deficits and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder on academic outcomes in children. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:757–766. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.5.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley RH, Corwyn RF. Socioeconomic status and child development. Annual Review of Psychology. 2002;53:371–399. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady SA. The role of working memory in reading disability. Haskins Laboratories Status Report on Speech Research. 1991;105/106:9–22. [Google Scholar]

- Castellanos FX, Tannock R. Neuroscience of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: The search for endophenotypes. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2002;3:617–628. doi: 10.1038/nrn896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chacko A, Bedard AC, Marks DJ, Feirsen N, Uderman JZ, Chimiklis A, … Ramon M. A randomized clinical trial of Cogmed working memory training in school-age children with ADHD: A replication in a diverse sample using a control condition. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2014;55:247–255. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jong CGW, Van De Voorde S, Roeyers H, Raymakers R, Oosterlaan J, Sergeant JA. How distinctive are ADHD and RD? Results of a double dissociation study. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2009;37:1007–1017. doi: 10.1007/s10802-009-9328-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeShazo T, Lyman RD, Grofer L. Academic underachievement and ADHD: The negative impact of symptom severity on school performance. Journal of School Psychology. 2002;40:259–283. [Google Scholar]

- DuPaul GJ, Power TJ, Anastopoulus AD, Reid R. ADHD-Rating Scale-IV (for children and adolescents): Checklists, norms, and clinical interpretation. New York: Guilford Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Fair DA, Bathula D, Nikolas MA, Nigg JT. Distinct neuropsychological subgroups in typically-developing youth inform heterogeneity in children with ADHD. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2012;109:6769–6774. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1115365109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gathercole SE, Pickering SJ. Working memory deficits in children with low achievements in the national curriculum at 7 years of age. British Journal of Educational Psychology. 2000;70:177–194. doi: 10.1348/000709900158047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gathercole SE, Pickering SJ, Ambridge B, Wearing H. The structure of working memory from 4 to 15 years of age. Developmental Psychology. 2004;40:177–190. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.40.2.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gau SS, Chiang H. Association between early attention-deficit/hyperactivity symptoms and current verbal and visuo-spatial short-term memory. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2013;34:710–720. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2012.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gau SS, Chiu CD, Shang CY, Cheng AT, Soong WT. Executive function in adolescence among children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in Taiwan. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics. 2009;30:525–534. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e3181c21c97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Healey DM, Gopin C, Grossman BR, Campbell SB, Halperin JM. Mother-child dyadic synchrony is associated with better functioning in hyperactive/inattentive preschool children. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2010;51:1058–1066. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02220.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinshaw SP. Externalizing behavior problems and academic underachievement in childhood and adolescence: Causal relationships and underlying mechanisms. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;111:127–155. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.111.1.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes J, Hilton KA, Place M, Alloway TP, Elliott JG, Gathercole SE. Children with low working memory and children with ADHD: Same or different? Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 2014;8:1–13. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2014.00976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorm AF. Specific reading retardation and working memory: A review. British Journal of Psychology. 1983;74:311–342. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8295.1983.tb01865.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan E, Fein D, Kramer J, Morris R, Delis D, Maerlender A. Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children – Fourth Edition Integrated (WISC-IV Integrated) San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kasper LJ, Alderson RM, Hudec KL. Moderators of working memory deficits in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2012;32:605–617. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2012.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, Rao U, Ryan N. The schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia for school-aged children and lifetime version (version 1.0) Pittsburgh, PA: Department of Psychiatry, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Kerns KA, McInerney RJ, Wilde NJ. Time reproduction, working memory, and behavioral inhibition in children with ADHD. Child Neuropsychology. 2001;7:21–31. doi: 10.1076/chin.7.1.21.3149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loe IM, Feldman HM. Academic and educational outcomes of children with ADHD. Ambulatory Pediatrics. 2007;7:82–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ambp.2006.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinussen R, Hayden J, Hogg-Johnson STR. A meta-analysis of working memory impairments in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2005;44:377–384. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000153228.72591.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinussen R, Tannock R. Working memory impairments in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder with and without comorbid language learning disorders. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 2006;28:1073–1094. doi: 10.1080/13803390500205700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattfeld AT, Whitfield-Gabrieli S, Biederman J, Spencer T, Brown A, Fried R, Gabrieli JD. Dissociation of working memory impairments and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in the brain. NeuroImage: Clinical. 2016;10:274–282. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2015.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McInnes A, Humphries T, Hogg-Johnson S, Tannock R. Listening comprehension and working memory are impaired in attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder irrespective of language impairment. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2003;31:427–443. doi: 10.1023/A:1023895602957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean JF, Hitch GJ. Working memory impairments in children with specific arithmetic learning difficulties. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 1999;74:240–260. doi: 10.1006/jecp.1999.2516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nigg JT, Willcutt EG, Doyle AE, Sonuga-Barke EJS. Causal heterogeneity in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: Do we need neuropsychologically impaired subtypes? Biological Psychiatry. 2005;57:1224–1230. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikolas MA, Nigg JT. Neuropsychological performance and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder subtypes and symptom dimensions. Neuropsychology. 2013;27:107–120. doi: 10.1037/a0030685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikolas MA, Nigg JT. Moderators of neuropsychological mechanism in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2015;43:271–281. doi: 10.1007/s10802-014-9904-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pastor PN, Reuben CA. Vital and Health Statistics. 237. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 1600 Clifton Road, Atlanta, GA 30333: 2008. Diagnosed Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder and Learning Disability: United States, 2004–2006. Data from the National Health Interview Survey. Series 10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pliszka SR. Patterns of psychiatric comorbidity with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2000;9:525–540. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polanczyk G, de Lima MS, Horta BL, Biderman J, Rohde LA. The worldwide prevalence of ADHD: A systematic review and metaregression analysis. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;164:942–948. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.6.942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajendran K, Trampush JW, Rindskopf D, Marks DJ, O’Neill S, Halperin JM. Association between variation in neuropsychological development and trajectory of ADHD severity in early childhood. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2013;170:1205–1211. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12101360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapport MD, Bolder J, Kofler MJ, Sarver DE, Raiker JS, Alderson RM. Hyperactivity in boys with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): A ubiquitous core symptom or manifestation of working memory deficits? Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2009;37:521–534. doi: 10.1007/s10802-008-9287-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapport MD, Chung KM, Shore G, Issacs P. A conceptual model of child psychopathology: Implications for understanding attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and treatment efficacy. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 2001;30:48–58. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3001_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapport MD, Orban SA, Kofler MJ, Friedman LM. Do programs designed to train working memory, other executive functions, and attention benefit children with ADHD? A meta-analytic review of cognitive, academic, and behavioral outcomes. Clinical Psychology Review. 2013;33:1237–1252. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2013.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers M, Hwang H, Toplak M, Weiss M, Tannock R. Inattention, working memory, and academic achievement in adolescents referred for attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) Child Neuropsychology. 2011;17:444–458. doi: 10.1080/09297049.2010.544648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaffer D, Gould MS, Brasic J, Ambrosini P, Fisher P, Bird H, Aluwahlia S. A children’s global assessment scale (CGAS) Archives of General Psychiatry. 1983;40:1228–1231. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1983.01790100074010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuchardt K, Maehler C, Hasselhorn M. Working memory deficits in children with specific learning disorders. Journal of Learning Disabilities. 2008;41:514–523. doi: 10.1177/0022219408317856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selig JP, Preacher KJ. Mediation models for longitudinal data. Research in Human Development. 2009;6:144–164. doi: 10.1080/1542760000902911247. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel LS, Ryan EB. The development of working memory in normally achieving and subtypes of learning disabled children. Child Development. 1989;60:973–980. doi: 10.2307/1131037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simone AN, Bedard AC, Marks DJ, Halperin JM. Good holders, bad shufflers: An examination of working memory processes and modalities among children with and without attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2016;22:1–11. doi: 10.1017/S1355617715001010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirin SR. Socioeconomic status and academic achievement: A meta-analytic review of research. Review of Educational Research. 2005;75:417–453. [Google Scholar]

- Sjowall D, Thorell LB. Functional impairments in attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: The mediating role of neuropsychological functioning. Developmental Neuropsychology. 2014;39:187–204. doi: 10.1080/87565641.2014.886691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson HL, Sachse-Lee C. Mathematical problem solving and working memory in children with learning disabilities: Both executive and phonological processes are important. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 2001;79:294–321. doi: 10.1006/jecp.2000.2587. doi.org/10.1006/jecp.2000/2587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trampush JW, Miller CJ, Newcorn JH, Halperin JM. The impact of childhood ADHD on dropping out of high school in urban adolescents/young adults. Journal of Attention Disorders. 2009;13:127–136. doi: 10.1177/1087054708323040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Dongen-Boomsma M, Vollebregt MA, Buitelaar JK, Slaats-Willemse D. Working memory training in young children with ADHD: A randomized placebo-controlled trial. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2014;55:886–896. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visser SN, Danielson ML, Bitsko RH, Holbrook JR, Kogan MD, Ghandour R, … Blumberg SJ. Trends in the parent-report of health care provider-diagnosed and medicated attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: United States, 2003–2011. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2014;53:34–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walkup JT, Stossel L, Rendleman R. Beyond rising rates: Personalized medicine and public health approaches to the diagnosis and treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2014;53:14–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Gathercole SE. Working memory deficits in children with reading difficulties: Memory span and dual task coordination. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 2013;115:188–197. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2012.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware AL, Crocker N, O’Brien JW, Deweese BN, Roesch SC, Coles CD, … Mattson SN. Executive function predicts adaptive behavior in children with histories of heavy prenatal alcohol exposure and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2012;36:1431–1441. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01718.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Wechsler Individual Achievement Test – Second Edition (WIAT-II) San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence- Third Edition (WPPSI-III) San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Willcutt EG, Doyle AE, Nigg JT, Faraone SV, Pennington BF. Validity of the executive function theory of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A meta-analytic review. Biological Psychiatry. 2005;57:1336–1346. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolraich ML, Lambert W, Doffing MA, Bickman L, Simmons T, Worley K. Psychometric properties of the Vanderbilt ADHD diagnostic parent rating scale in a referred population. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2003;28:559–567. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsg046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]