Abstract

Objective

Body image disturbance is a distressing and interfering problem among many sexual minority men living with HIV, and is associated with elevated depressive symptoms and poor HIV self-care (e.g., antiretroviral therapy [ART] non-adherence). The current study tested the preliminary efficacy of a newly created intervention: cognitive behavioral therapy for body image and self-care (CBT-BISC) for this population.

Methods

The current study entailed a two-arm randomized controlled trial (N = 44) comparing CBT-BISC to an enhanced treatment as usual (ETAU) condition. Analyses were conducted at 3 and 6 months after baseline. The primary outcome was body image disturbance (BDD-YBOCS), and secondary outcomes were ART adherence (electronically monitored via Wisepill), depressive symptoms (MADRS), and global functioning (GAF).

Results

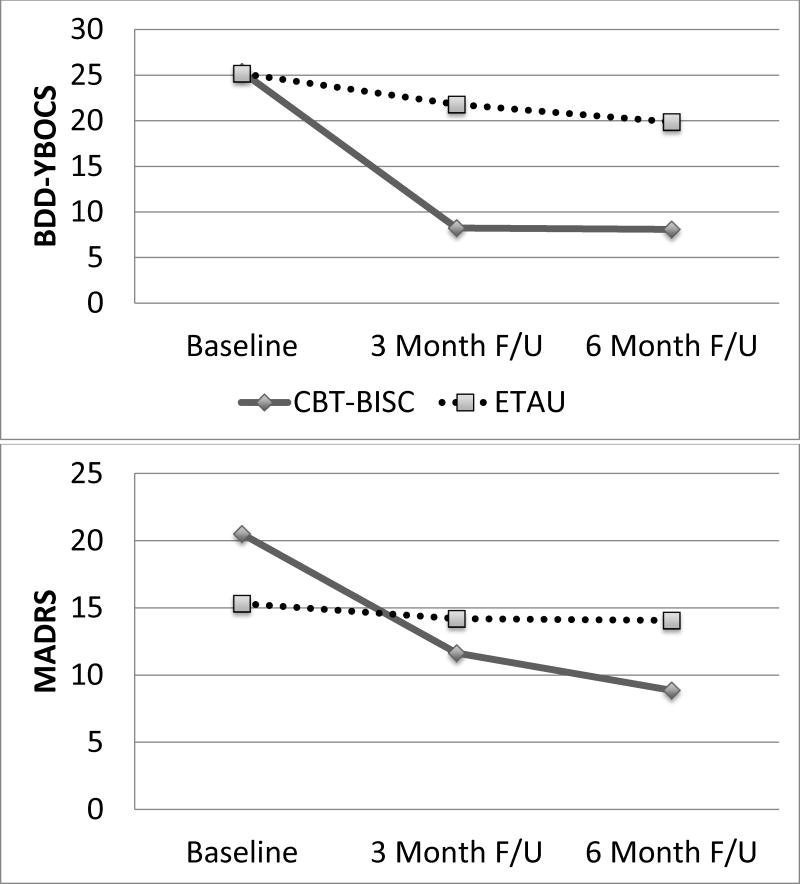

At 3 months, the CBT-BISC condition showed substantial improvement in BDD-YBOCS (b = −13.6, SE = 2.7, 95% CI: −19.0, −8.3, p < .001; dppc2 = 2.39), MADRS (b = −4.9, SE = 2.8, 95% CI: −10.6, .70, p = .086; dppc2 = .87), ART adherence (b = 8.8, SE = 3.3, 95% CI: 2.0, 15.6, p = .01; dppc2 = .94), and GAF (b = 12.3, SE = 3.2, 95% CI: 6.1, 18.6, p < .001; dppc2 = 2.91) compared to the ETAU condition. Results were generally maintained, or improved, at 6 months; although, adherence findings were mixed depending on the calculation method.

Conclusions

CBT-BISC shows preliminary efficacy in the integrated treatment of body image disturbance and HIV self-care behaviors among sexual minority men living with HIV.

Keywords: HIV, Antiretroviral therapy, ART, Adherence, Body image, Randomized controlled trial, Men who have sex with men, Sexual minority

Body image disturbance (i.e., dissatisfaction, concern, and distress regarding one’s appearance; Thompson, Heinberg, Altabe, & Tantleff-Dunn; 1999) is common among sexual minority (e.g., gay and bisexual) men (Morrison, Morrison, & Sager, 2004; Peplau, Frederick, Yee, Maisel, Lever, & Ghavami, 2009), including those living with HIV (Sharma et al., 2007). Indeed, one study found that 1/3 of sexual minority men living with HIV reported elevated body dissatisfaction (Sharma et al., 2007). Recently, in a tested biopsychosocial model of body image disturbance among sexual minority men living with HIV (Blashill, Goshe, Robbins, Mayer, & Safren, 2015), biological (i.e., lipodystrophy) and sociocultural (i.e., appearance investment) factors independently contributed to elevated body image disturbance. Lipodystrophy may be a complication of HIV infection and its treatment, defined as the presence of lipoatrophy and/or lipohypertrophy (Caron-Debarle, Lagathu, Boccara, Vigouroux, & Capeau, 2010). Lipoatrophy was associated with advanced HIV, and lipohypertrophy associated with specific antiretroviral therapy (ART) medications (e.g. stavudine), and despite a reduction over time (with the advent of earlier treatment with newer, less toxic ART), a recent study identified a prevalence rate of 53% in chronically infected patients (Price, Hoy, Ridley, Nyulasi, Paul, & Wooley, 2015). Socioculturally, internalizing unrealistic appearance ideals promulgated by Western society (e.g., high muscularity and low body fat for men) can lead to body image disturbance when individuals compare their own appearance to unattainable body ideals (Cafri, Yamamiya, Brannick, & Thompson, 2005). This process of internalizing appearance ideals, monitoring one’s own appearance, and objectifying oneself is more common among sexual minority men compared to heterosexual men (Carper, Negy, & Tantleff-Dunn, 2010; Engeln-Maddox, Miller, & Doyle, 2011). Thus, there are likely multiple pathways that lead to body image disturbance in this population.

Not only is body image disturbance inherently distressing and impairing, but it is also associated with a host of health risk behaviors in sexual minority men living with HIV (Blashill et al., 2015). For instance, body image disturbance predicts increased depressive symptoms (Blashill et al., 2015; Blashill, Gordon, & Safren, 2012), poor ART adherence (Blashill et al., 2015; Blashill & Vander Wal, 2010) and increased condomless anal sex with HIV sero-discordant partners (Blashill et al., 2015; Blashill, Wilson, Baker, Mayer, & Safren, 2014). Depression is also linked with poor ART adherence (Gonzalez, Batchelder, Psaros, & Safren, 2011), more rapid disease progression (e.g., Leserman, 2008) and mortality (e.g., Ickovics, Hamburger, Vlahov et al., 2001).

ART adherence is important not only to the individual health of people living with HIV but also to public health. ART adherence suppresses HIV replication, which prevents HIV-associated immunological destruction (e.g., Günthard, Saag, Benson, et al., 2016). From a public health perspective, individuals living with HIV who are able to reach viral suppression have a substantially reduced likelihood of transmitting HIV to sexual partners (Rodger, Cambiano, Bruun, et al., 2016).

Although the benefits of ART adherence are clear, sustaining long-term adherence (e.g., 85% or higher; Viswanathan, Justice, Alexander et al., 2015) is often challenging. Meta-analytic findings found a mean level of ART adherence of 64% (Mills, Nachega, Buchan et al., 2006), with only 62% reaching a threshold of 90% adherence or greater (Ortego, Huedo-Medina, Llorca, et al., 2011). To date, there have been many interventions developed to promote ART adherence, and these programs have often produced significant improvements in adherence; however, the magnitude of change has been relatively modest (Amico, Harman, & Johnson, 2006; Finitsis, Pellowski, & Johnson, 2014; Simoni, Amico, Pearson, & Malow, 2008). One explanation for these modest effects is that generally, traditional ART adherence interventions do not simultaneously address psychosocial problems—a crucial risk factor for non-adherence (Blashill, Bedoya, Mayer, O’Cleirigh, et al., 2015; Parsons, Rosof, & Mustanski, 2008; Gonzalez et al., 2011). Indeed, meta-analytic results have found that treating psychosocial problems (e.g., depression) improves ART adherence (Sin & DiMatteo, 2014). Although there recently have been promising studies examining the efficacy of ART adherence interventions that simultaneously treat depression and adherence (Safren et al., 2012; 2009), no known interventions exist that focus on improving body image disturbance and ART adherence among individuals living with HIV.

Given that morphological changes in muscularity and adiposity are common among individuals living with HIV, primarily due to the side effects of ART, it follows that individuals with elevated body image disturbance may have poor adherence given concerns about expressing lipodystrophic features. Additionally, body image disturbance may impact ART adherence indirectly through elevated depressive symptoms. With this in mind, the aim of the current study was to test the acceptability, feasibility and preliminary efficacy of a cognitive behavioral intervention for adherence and body image disturbance (cognitive behavioral therapy for body image and self-care; CBT-BISC) among sexual minority men living with HIV.

CBT-BISC is an individual treatment that integrates an existing single-session ART adherence intervention (LifeSteps; Safren et al., 1999) with established CBT interventions for body image disturbance (Cash, 2008; Wilhelm et al., 2013). Prior to the current study, a small open-pilot study with 3 sexual minority men living with HIV was conducted to initially assess and refine the CBT-BISC treatment manual. However, the focus of the open-trial was largely on qualitative feedback from participants, and thus, the current study represents the first empirical examination of the intervention’s efficacy. Accordingly, we hypothesized that CBT-BISC would reduce body image disturbance and depressive symptoms, while also improving ART adherence compared to an enhanced treatment as usual (ETAU) condition. These hypothesized benefits were predicted at 3 (acute) and 6 months (follow-up) after baseline.

Method

Study Design and Participants

Participants were 44 (22 randomized to CBT-BISC; 22 randomized to ETAU) sexual minority men living with HIV who reported elevated appearance concerns. Inclusion criteria for the study were: 1) HIV-infected; 2) reported oral or anal sex (with or without condoms) with men in the prior 12 months; 3) self-identified as male gender; 4) age 18 to 65; 5) prescribed ART for the past two months or longer; and 6) significant body image disturbance, as indicated by a score of 16 or higher on the clinician-administered Body Dysmorphic Disorder modification of the Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (BDD-YBOCS; Phillips, Hollander, Rasmussen & Aronowitz, 1997). The cut score of 16 on the BDD-YBOCS was chosen as it is roughly .5 SD below the score of 20, which is typically the minimum score used to denote clinically diagnosable body dysphormic disorder (BDD). A score of 16 captures elevated body image disturbance, without restricting inclusion to only those with levels consistent with a full scale BDD diagnosis. In addition, the following exclusion criteria were used: 1) presence of another severe psychiatric disorder that would interfere with study participation (e.g., unstable bipolar disorder); and 2) received CBT for body image disturbance within the past 12 months.

Participant characteristics are presented in Table 1. Table 2 depicts the unadjusted study outcomes across major assessment time points. At baseline, the majority of participants presented with substantial psychiatric comorbidity, with 72.7% diagnosed with more than one DSM-IV condition. The most prevalent diagnosis was body dysmoprhic disorder at 68.2%, followed by major depressive disorder (45.5%), generalized anxiety disorder (34.1%), and dysthymic disorder (27.3%). Overall, the sample displayed high levels of viral suppression, with roughly 95% having an undetectable viral load at baseline and follow-ups. Additionally, only 16% of participants were working or attending school full-time during the study period.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics

| Variable | Total | CBT-BISC | ETAU |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| N (%) | |||

| Race | |||

| African American/Black | 15 (34.10) | 10 (45.45) | 5 (22.72) |

| White | 28 (63.60) | 12 (54.54) | 16 (72.72) |

| Native American | 2 (4.50) | 1 (4.54) | 1 (4.54) |

| Other | 2 (4.50) | 1 (4.54) | 1 (4.54) |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Hispanic/Latino | 10 (22.70) | 5 (22.72) | 5 (22.72) |

| Sexual Orientation | |||

| Gay | 43 (97.70) | 21 (95.45) | 22 (100) |

| Bisexual | 1 (2.30) | 1 (4.54) | 0 (0) |

| Employment | |||

| Full-time work or school | 7 (15.90) | 5 (22.72) | 2 (9.09) |

| Part-time work or school | 13 (29.50) | 6 (27.27) | 7 (31.81) |

| Neither work nor school | 5 (11.40) | 2 (9.09) | 3 (13.63) |

| On disability | 19 (43.20) | 8 (36.36) | 11 (50.00) |

| Education Level | |||

| Partial high school | 1 (2.30) | 0 (0) | 1 (4.54) |

| High school graduate/GED | 9 (20.50) | 3 (13.63) | 6 (27.27) |

| Partial college | 15 (34.10) | 7 (31.81) | 8 (36.36) |

| College graduate | 19 (43.20) | 12 (54.54) | 7 (31.81) |

| Psychiatric Diagnoses | |||

| At least one diagnosis | 42 (95.50) | 21 (95.45) | 21 (95.45) |

| Two or more diagnoses | 32 (72.72) | 17 (77.27) | 15 (68.18) |

| Body dysmorphic disorder | 30 (68.20) | 14 (63.63) | 16 (72.72) |

| Major depressive disorder | 20 (45.50) | 12 (54.54) | 8 (36.36) |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 15 (34.10) | 10 (45.45) | 5 (22.72) |

| Dysthymic disorder | 12 (27.30) | 8 (36.36) | 4 (18.18) |

| Substance dependence | 9 (20.50) | 5 (22.72) | 4 (18.18) |

| Eating disorder† | 8 (18.20) | 7 (31.81) | 1 (4.54) |

| Social anxiety disorder | 7 (15.90) | 3 (13.63) | 4 (18.18) |

| Alcohol dependence | 7 (15.90) | 4 (18.18) | 3 (13.63) |

| Viral Load Detectable* | 2 (5.40) | 1 (4.54) | 1 (4.54) |

|

| |||

| M (SD) | |||

|

| |||

| CD4 Count** | 820.47 (402.10) | 859.94 (428.58) | 785.15 (385.13) |

| Age | 46.18 (11.03) | 45.68 (11.75) | 46.68 (10.51) |

| BMI | 27.34 (4.88) | 28.23 (5.17) | 26.48 (4.53) |

Note. Race percentages sum to greater than 100% as responses were not mutually exclusive;

n = 37;

n = 36;

Binge eating disorder or Eating disorder not otherwise specified; BMI = body mass index.

Table 2.

Unadjusted Means, Standard Deviations and Frequencies of Outcomes Across Conditions and Time

| Baseline (T1) | 3 Month (T2) | 6 Month (T3) | dppc2 (T2) | dppc2 (T3) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BDD-YBOCS | |||||

| CBT-BISC | 25.36 (6.19) | 8.24 (8.95) | 8.08 (10.08) | 2.39 | 2.09 |

| ETAU | 25.18 (5.15) | 21.80 (9.70) | 19.87 (12.24) | ||

| Total Adherence | |||||

| CBT-BISC | 93.83 (10.64) | 94.32 (13.08) | 95.86 (12.52) | .50 | 1.35 |

| ETAU | 97.33 (4.83) | 93.67 (9.94) | 88.18 (14.77) | ||

| On-time Adherence | |||||

| CBT-BISC | 78.24 (18.66) | 88.22 (19.51) | 86.55 (23.07) | .94 | .93 |

| ETAU | 85.60 (15.52) | 79.29 (24.34) | 77.91 (23.87) | ||

| BABS | |||||

| CBT-BISC | 7.36 (7.87) | 2.17 (5.53) | 2.09 (5.58) | .72 | .62 |

| ETAU | 8.00 (5.39) | 7.71 (7.78) | 6.92 (7.97) | ||

| BIDQ | |||||

| CBT-BISC | 3.26 (0.56) | 1.76 (0.84) | 1.66 (0.79) | 1.34 | 1.52 |

| ETAU | 3.16 (0.79) | 2.58 (1.03) | 2.61 (1.07) | ||

| % (n) BDD-YBOCS Responders | |||||

| CBT-BISC | - | 95.45% (21) | 90.90% (20) | - | - |

| ETAU | - | 22.72% (5) | 27.27% (6) | ||

| MADRS | |||||

| CBT-BISC | 20.50 (7.41) | 11.64 (9.75) | 8.86 (9.23) | .87 | 1.17 |

| ETAU | 15.31 (10.03) | 14.19 (10.41) | 14.06 (10.55) | ||

| GAF | |||||

| CBT-BISC | 50.40 (5.44) | 68.69 (12.00) | 72.61 (13.88) | 2.91 | 3.39 |

| ETAU | 53.59 (4.64) | 57.07 (9.84) | 58.55 (12.52) | ||

Note. CBT-BISC = Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Body Image and Self-Care; ETAU = Enhanced Treatment as Usual; BDD-YBOCS = the Body Dysmorphic Disorder modification of the Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale; BABS = Brown Assessment of Beliefs Scale; BIDQ = Body Image Disturbance Questionnaire; MADRS = Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale; GAF = Global Assessment of Functioning.

Setting and Recruitment

The study visits took place at Fenway Health, a community health center in Boston serving the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) community. Recruitment occurred primarily at Fenway Health, with study flyers placed on medical and research floors. Recruitment also included community outreach (e.g., AIDS service organizations in the Boston area) and online advertisement via mobile geo-location based social apps targeted towards sexual minority men (i.e., Grindr). Enrollment occurred between November of 2013 and March of 2016. At the beginning of the baseline assessment session, the project coordinator met with each potential participant and thoroughly reviewed the informed consent document, after which, participants gave their written consent to participate. All assessment and intervention sessions, across both conditions, were audio recorded after consent to do so was obtained from participants. The Institutional Review Boards at Fenway Health, Partner’s Healthcare, and San Diego State University approved all study procedures.

Sample Size

Given that the current study was a pilot RCT, the aims were not necessarily to detect statistically significant group differences. Rather, emphasis in this trial was on establishing acceptability, feasibility and preliminary efficacy. Thus, in lieu of a formal a priori power analysis, sample size estimates were based on recommendations by Rounsaville, Carroll, and Onken (2001), who suggest that for behavioral pilot RCTs, randomizing between 15 and 30 participants per condition should be sufficient.

Randomization

Participants were randomly assigned in blocks of four by the study coordinator, and were stratified based on body image disturbance score (i.e., scores of 36 or higher on the BDD-YBOCS, which denotes severe symptoms). Prior to the beginning of the study, a randomization chart was created, corresponding to each participant identification number. Assignment to study condition (CBT-BISC or ETAU) was concealed from participants and study clinicians until the end of session 1. Specifically, condition assignment was written on a sheet of paper, with an opaque sticker over it, so as the clinician would not see the assignment until the sticker was removed at the end of session 1.

Study Visits

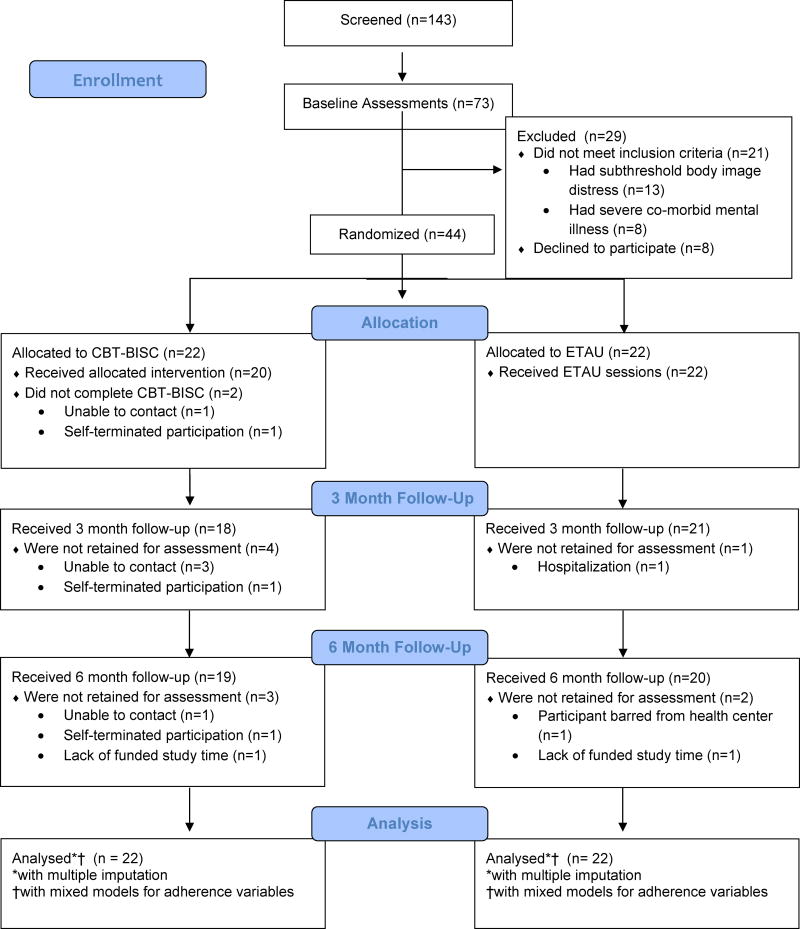

All participants were initially evaluated to determine study eligibility at baseline assessment (T1, time 1), and if found to be eligible, were scheduled for session 1 roughly two weeks after baseline (this period established an ART adherence baseline; see measures for more details). Each participant, regardless of their condition assignment, received session 1, “Life Steps”, at the conclusion of which they learned of their randomization assignment. In the CBT-BISC condition, participants were scheduled for 11 additional, weekly, 50-minute individual sessions with a study clinician. In the ETAU condition, participants were scheduled for 5 additional bi-weekly visits with the project coordinator. At the end of treatment, participants completed an immediate assessment, which occurred roughly 3 months after baseline (T2; Time 2). Additionally, participants completed a follow-up assessment roughly 3 months after treatment completion/6 months after baseline (T3; Time 3). Baseline, T2 and T3 assessment sessions included clinician-based assessment, self-reports, and electronic monitoring of ART adherence. See Figure 1 for the CONSORT Flow Chart. Participants were compensated $310 over the course of the study.

Figure 1.

CONSORT Flow Chart

Independent Assessors

Several independent assessors, all of whom were blind to study condition, conducted the clinician-administered outcome assessments. Independent assessors included a doctoral student in clinical psychology, a postdoctoral fellow in clinical psychology, and a doctoral-level social worker. All had significant experience in clinical assessment. The independent assessors administered: 1) the BDD-YBOCS (Phillips et al., 1997); 2) the Brown Assessment of Beliefs Scale (BABS; Eisen et al., 1998); 3) the Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS; Montgomery & Asberg, 1979); and 4) the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF; American Psychiatric Association, 2000). Independent assessors received ongoing supervision with an expert (a clinical psychologist) in the administration of the primary outcome variable (the BDD-YBOCS). The assessment supervisor reviewed randomly selected audio files (10%) from assessment sessions to review the BDD-YBOCS, and was blind to study condition. Participants were also reminded by the project coordinator before major assessment sessions to not disclose their randomization assignment to the independent assessor. In the few instances where there were discrepancies between the assessment supervisor and independent assessor’s rating on the BDD-YBOCS, the assessment supervisor’s score was entered into the data set as the score of record.

Assessment Measures

Body image disturbance

Body image disturbance was assessed by clinician-administered semi-structured interviews and self-report. Clinicians administered the BDD-YBOCS (Phillips et al., 1997), a 12-item semi-structured interview that assesses body image disturbance symptoms over the past week, ranging on a five-point scale from 0 (least severe) to 4 (most severe). The BDD-YBOCS has previously demonstrated strong internal consistency, test-retest reliability, and convergent validity (Phillips & Diaz, 1997; Phillips, Hart & Menard, 2014). A total score was calculated by summing the responses to all items. Higher scores denote greater body image disturbance. Internal consistency estimates from the current sample ranged from α = .84 (baseline) to α = .93 (3 month), and a two-way random model of absolute agreement was ICC = .99. Additionally, a dichotomous responder status variable was defined as 1 (30% or greater BDD-YBOCS reduction from baseline) vs. 0 (less than 30% reduction from baseline). This 30% reduction cut-point has previously been established as a marker of substantial symptom improvement, demonstrating 90% sensitivity and 86% specificity in correctly identifying participants as “much improved” or greater on the Clinical Global Impression of Improvement (CGI-I; National Institute of Mental Health, 1985) scale (Phillips et al., 1997; Phillips et al., 2014).

Clinicians also administered the Brown Assessment of Beliefs Scale (BABS; Eisen et al., 1998), a 6-item semi-structured interview that measures insight regarding participants’ appearance-based beliefs over the past week, ranging on a five-point scale from 0 (least severe) to 4 (most severe). The BABS has previously demonstrated strong psychometric properties (Eisen et al., 1998). Internal consistency estimates from the current sample ranged from α = .94 (baseline) to α = .96 (3 month).

Additionally, participants completed a self-report measure of body image disturbance—the Body Image Disturbance Questionnaire (BIDQ; Cash, Phillips, Santos, & Hrabosky, 2004). The BIDQ consists of seven items, responded to on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (least severe) to 5 (most severe). Responses were averaged, with higher scores denoting increased body image disturbance. The BIDQ has demonstrated strong internal consistency, concurrent, discriminate, construct, and incremental validity (Cash et al., 2004). Internal consistency estimates from the current sample ranged from α = .88 (baseline) to α = .96 (3 month).

ART Adherence

Adherence to ART was assessed via an electronic adherence monitor: Wisepill (Wispill Technologies, Cape Town, South Africa). Wisepill is a device that contains a 7-day plastic pillbox that can hold up to 30 pills. When the device is opened, in real-time a digital signal is sent to a server located in Cape Town, South Africa. The data sent to the server was accessible to study staff via a secure website. The device is relatively compact, and can be transported in one’s pocket, and only needs to be charged every 4 months. In a series of studies conducted in Africa, Wisepill demonstrated feasibility, acceptability, construct validity, and was also found to predict loss of viral suppression (Haberer, Kahane, Kigozi, et al., 2010; Haberer, Kiwanuka, Nansera, et al., 2013). If participants could not fit their entire ART regimen into Wisepill, they were instructed to place inside the device a single ART medication that was most difficult to remember or most difficult to take. If participants reported that their medications were equally difficult to remember or take, they used Wisepill for the pill that they took most frequently. To account for doses that participants may have taken without opening the Wisepill (e.g., took out afternoon doses when they opened it in the morning), a dose was counted as taken if participants could recall, with certainty, specific instances when they took their medication but did not use the Wisepill. This procedure is consistent with studies comparing multiple measures of adherence with HIV outcomes (e.g., Liu et al., 2001, 2006).

ART adherence scores were calculated in two ways. First, an “on-time” adherence score was calculated by dividing the number of doses taken within an established time window (± 2 hours from target adherence time) by the number of prescribed doses. This designated time was established with the clinician and the participant at the baseline visit, but could be modified at any point in the study, if the participant wished. Second, “total” adherence scores were calculated by dividing the number of doses taken, irrespective of whether these doses fell within the adherence window, by the number of prescribed doses. For weekly visit sessions, T2 and T3 assessments, past two week monitoring periods were used for adherence outcomes. The baseline value of adherence was calculated at session 1, two weeks after baseline (given that participants were not given Wisepill until the end of their baseline visit, session 1 data represents the first two week period of participants using Wisepill). On-time adherence scores have been found to significantly predict viral load, over and above total adherence counts, highlighting their importance in managing HIV (Gill, Sabin, Hamer et al., 2010; Liu, Miller, Hays et al., 2006).

Depressive symptoms

Clinicians administered the Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS; Montgomery & Asberg, 1979), a 10-item semi-structured interview that assesses severity of depressive symptoms. The MADRS is a widely used clinical measure of depression with strong psychometric properties (Davidson, Turnbull, Strickland, 1986; Muller, Himmerich, Kienzle, & Szegedi, 2003; Khan, Khan, Shankles, & Polissar, 2002). Each item assesses the severity of depressive symptoms over the past week, ranging on a seven-point scale from 0 (least severe) to 7 (most severe), and a total score was calculated by summing the responses to all items. Higher scores indicate elevated depressive symptoms. Internal consistency estimates from the current sample ranged from α = .84 (baseline) to α = .88 (3 month).

Assessment of functioning

The Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF; American Psychiatric Association, 2000) is a clinician-based assessment of general social, occupation, and psychological functioning and symptom severity. The scale ranges from 0 to 100, with higher scores denoting superior functioning. The GAF demonstrates stronger inter-rater reliability and concurrent validity with global symptom severity indices (Hilsenroth, Ackerman, Blagys et al., 2000; Jones, Thornicroft, Coffey, & Dunn, 1995).

Psychiatric diagnosis

Clinician-based evaluation of DSM-IV diagnoses were assessed via the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI; Sheehan et al., 1997; 1998), a widely used psychiatric interview with psychometric data comparable to the Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-IV (SCID-I; First, Spitzer, Gibbon Miriam & Williams, 2002; Amorim, 2000). Because the MINI doses not assess body image disorders (i.e., body dysmorphic disorder, and eating disorders), clinicians also administered the body dysmorphic disorder and eating disorder modules from the SCID-I (First et al., 2002).

Biometric variables

Height and weight were assessed at each major assessment session by the project coordinator. Height was measured via a stadiometer and weight was assessed with an electronic scale. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated with the following formula: (703 * weight in pounds)/(height in inches * height in inches). Additionally, relevant HIV care-related assays (CD4 count and HIV viral RNA) were accessed from participants’ medical records. Records were matched as closely as possible to the date of participants’ major assessment sessions (e.g., record date must have been within 6 months ± from the study assessment date). BMI and CD4 counts are presented as continuous variables, whereas HIV RNA was presented dichotomously--viral load detectable (greater than 74 copies/ml) vs. undetectable (less than 74 copies/ml).

Participant satisfaction

Participants in the CBT-BISC condition completed an author created 8-item self-report measure of satisfaction with clinical services offered within the intervention, at T2. Responses ranged from 1 (most dissatisfied) to 4 (most satisfied). Example items included: “In an overall, general sense, how satisfied are you with the help you received?” and “Has the help you received helped you to deal more effectively with your problems?” Internal consistency estimates from the current sample was α = .84.

Treatment fidelity

Clinician competence and adherence to the intervention manual was assessed via an author created Therapist Adherence Rating Form (TARF). The TARF includes 9 generic session structure ratings, which assess CBT techniques that should be included in each of the CBT-BISC sessions. These items are rated on a 7-point scale ranging from 0 (least adherent) to 6 (most adherent). In addition to these generic scores, there are also 8 module specific scores (corresponding to each of the CBT-BISC modules and Life-Steps). Number of items within each module varied (range 4 to 11). Count scores were calculated for each technique applied within the specific module. Given the varying response scales across modules, the possible total raw score was different depending on which session was being rated, thus, a total percent score is presented: raw generic + raw module specific rating/total possible raw generic + module specific score. Audio recordings from treatment sessions were utilized, with a random sample of 29 sessions selected for rating, constituting roughly 10% of all CBT-BISC study sessions. Study clinicians made these ratings, with the caveat that they could not rate their own sessions.

Intervention Conditions

All participants received session 1, Life-Steps (Safren et al., 1999), a single-session that focuses on ART adherence. Techniques within Life-Steps include psychoeducation, motivational interviewing, problem-solving, and other behavioral skills (e.g., creating schedules for adherence, use of visual/auditory cues to remember to take ART). During this session, participants also identified their ART adherence goal (i.e., at what percent of total and on-time adherence they aimed for over the course of the study). Also, briefly, at the end of Life-Steps, participants were asked to define sexual health for themselves, and this subsequently lead to identification of a sexual health goal (e.g., to increase sexual satisfaction; reduce condomless anal sex; increase HIV disclosure before sex). At the conclusion of session 1, all participants were also given the option of having the study send a letter to their primary care physician, describing the nature of the current study, and suggesting that body image concerns, mood, and HIV self-care continue to be monitored/treated by the participants’ medical care team.

In the ETAU condition, after the completion of session 1, participants met with the project coordinator biweekly over the subsequent 3 months (6 total sessions). During these visits, the project coordinator reviewed participants’ ART adherence over the previous 2 weeks via Wisepill. During the review of adherence, the project coordinator made corrections for “pocketed doses” and/or electronic transmission error. Participants also completed several brief self-report instruments during these visits; each ETAU was roughly 15 minutes. Finally, the project coordinator provided referral information for mental health treatment to all participants assigned to the ETAU condition.

In the CBT-BISC condition, after the completion of session 1, participants met with a clinician weekly, over the subsequent 3 months (12 total sessions). Sessions were individual, and lasted roughly 50 minutes. CBT-BISC consists of 7 modules (plus LifeSteps), and follows a treatment manual (written by the first author). The modules were designed to be administered in a flexible approach. That is, clinicians utilized clinical judgment in the ordering of, and number of sessions devoted to, the modules. However, each participant in the CBT-BISC condition received at least one session of each module. In each of the 11 CBT-BISC sessions, clinicians continued to address strategies for, and barriers to, ART adherence, with a review of Wisepill data at the beginning of each session. Within these discussions, clinicians would also highlight the role body image may have had in impacting participants’ adherence goals. Review of and discussion of adherence was limited to the beginning 10 minutes of each session. Cognitive behavioral techniques to reduce body image disturbance were adopted from existing CBT manuals on the topic (Cash, 2008; Wilhelm, Phillips, Steketee, 2013).

All CBT-BISC sessions followed a similar structure: setting of the agenda, review of adherence data, review of homework, introduction of new material for the session, and concluded with the assignment of homework for the next week. Module 1 was an orientation to CBT, in which the clinician and participant reviewed the subjective nature of beauty, biopsychosocial theories of body image, and discussed the CBT model of body image and application of it to the participant’s presentation of symptoms. Module 2 focused on mindfulness and acceptance-based strategies. Module 3 centered on perceptual retraining—an exposure-based technique focused on participants’ experience with mirrors, which also incorporated aspects of mindfulness (e.g., as participants expose themselves to their reflection they describe their appearance in objective value-neutral terms, focusing on processing the gestalt as opposed to becoming fixated on specific areas of their body). Module 4’s focus was on cognitive restructuring. Participants learned to identify, challenge, and replace maladaptive cognitions. Module 5 was a continuation of exposure-based techniques. Although participants began exposure work with perceptual retraining, this module focused more broadly on situations that participants avoided due to body image disturbance. Module 6 addressed response prevention, with the goal to reduce the frequency of ritualistic behaviors that might maintain or exacerbate body image disturbance (e.g., camouflaging, reassurance seeking). Finally, Module 7 focused on relapse prevention, with participants reviewing skills learned throughout the intervention, and actively planning for how to address future stressors.

In the present study, clinicians were a licensed clinical psychologist, a post-doctoral fellow in clinical psychology, and pre-doctoral graduate student in clinical psychology. All had prior experience with CBT. Trainings included didactic learning of each module and review of audio recordings of sessions from initial pilot work (conducted by the first author). Additionally, each clinician met weekly with the first author for ongoing clinical supervision. This supervision involved review and feedback from audiotaped sessions.

Statistical Analyses

Generalized linear modeling (GENLIN) via SPSS (version 23) was employed to test longitudinal effects of BDD-YBOCS, MADRS, and GAF. BDD-YBOCS responder status was tested via Fisher’s exact test. Within GENLIN, baseline values of each outcome variable were entered, along with the binary condition variable (CBT-BISC vs. ETAU). Robust (Huber-White sandwich) estimators were used in all models, which is a corrected model-based estimator that produces reliable estimates of the covariance structure, even in scenarios when variance specifications and link functions are incorrect. For outcome variables, two models were tested: 1) testing group differences in T2 controlling for T1 value; and 2) testing group differences in T3 controlling for T1 value. Alternative analytic strategies were considered (e.g., generalized linear mixed models, generalized estimating equations); however, due to group differences at T1 for a number of outcome variables, baseline values needed to be controlled for, and with only three time points, precluded the use of mixed-effects modeling. Intent to treat (ITT) analyses was performed with all outcome variables. To utilize ITT analyses within GENLIN, multiple imputations (MI; Rubin, 1987) were conducted to correct for missing data (9% to 14% of data were missing). When conducting MI, 25 simulated values for each missing value were calculated, with the pooled results across the 25 simulations used as the final complete dataset; consistent with the recommendations of Graham, Olchowski, and Gilreath (2007).

Generalized linear mixed models (GENLINMIXED) via SPSS (version 23) were employed to test the treatment effects on adherence outcomes from T1 through T2. This approach was chosen as corrected adherence data were available at each of the study visit sessions during active treatment. To be consistent across conditions, we utilized 6 time points to test active treatment effects (week 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, and 3 month follow-up), whilst controlling for the baseline (week 1) adherence value. Within GENLINMIXED, random intercepts were selected, allowing each participant to have a unique starting value, and robust estimators were used to calculate standard error. As with the previous analyses, ITT procedures were used; however, multiple imputations were not necessary, as GENLINMIXED uses all available data through maximum likelihood estimation. Although adherence continued to be monitored via Wisepill from T2 through T3, participants did not have study visits during this period, and thus, these values are uncorrected. Given this, to test treatment effects at T3, GENLIN was employed, while controlling for the baseline adherence score.

Additionally, outliers were assessed, and values that were ± 3.3 standard deviations from the mean were replaced with the next highest (or lowest) value (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2006). The only variables in which outliers were detected were ART total and on-time adherence. For total adherence, 8 of 318 (2.5%) values were identified as outliers, whereas 4 of 318 (1.2%) values for on-time adherence were identified as outliers.

For all continuous outcome measures, estimates of effect size were calculated based on dppc2 (unadjusted mean change in CBT- unadjusted mean change in ETAU/unadjusted pooled standard deviations from baseline; Morris, 2008), which is appropriate for pre-test-posttest-control (PPC) designs (see Feingold, 2013). Specifically, dppc2 provides a more precise estimate of the population treatment effect by pooling the pre-test standard deviations from the treatment and control groups. Indeed, simulation studies found dppc2 to outperform other metrics of effect size (Morris, 2008). The interpretation of dppc2 is analogous to the benchmarks provided by Cohen (1992): dppc2 = 0.2 (small); dppc2 = 0.5 (moderate); and dppc2 = 0.8 (large). For dichotomous outcome variables, odds ratios and relative risks are presented as metrics of effect size.

Results

Participant Characteristics

Figure 1 depicts participant flow through the study. Eighty-nine percent of participants randomized were retained for 3 month (T2), and 6 month (T3) assessments. Twenty of the 22 participants (90%) randomized to CBT-BISC completed all intervention sessions. Table 2 depicts unadjusted scores for each study outcome as a function of time and condition.

Therapist Adherence and Acceptability

Overall, clinicians were highly adherent to the treatment manual, with a mean total percent score of 97.17% (SD = 4.05) for the random sample of 29 intervention sessions rated. CBT-BISC participants rated the intervention to be highly acceptable, with a mean Patient Satisfaction Questionnaire score of 3.68 (SD = .41). For example, 83% of CBT-BISC participants reported they were “very satisfied” with the help they received, and 100% reported they were “mostly satisfied” or “very satisfied.”

Body Image Disturbance

CBT-BISC had significantly lower BDD-YBOCS scores compared to ETAU at T2 (b = −13.6, SE = 2.7, 95% CI: −19.0, −8.3, p < .001; dppc2 = 2.39) and T3 (b = −11.9, SE = 3.2, 95% CI: −18.1, −5.6, p < .001; dppc2 = 2.09). CBT-BISC also had a significantly greater proportion of BDD-YBOCS responders compared to ETAU, with 95% (n = 21) in CBT-BISC and 23% (n = 5) in ETAU, at T2 (χ2 = 24.1, Fisher’s Exact Test < .001, Odds Ratio = 71.4, 95% CI: 7.6, 670, Relative Risk = 4.2). At T3, 91% (n = 20) of CBT-BISC participants were responders compared to 27% (n = 6) of ETAU participants (χ2 = 18.4, Fisher’s Exact Test < .001, Odds Ratio = 26.6, 95% CI: 4.7, 150.4, Relative Risk = 3.3). CBT-BISC had significantly lower BIDQ scores compared to ETAU at T2 (b = −.88, SE = .25, 95% CI: −1.4, −.39, p < .001; dppc2 = 1.34) and T3 (b = −1.0, SE = .25, 95% CI: −1.5, −.54, p < .001; dppc2 = 1.52). CBT-BISC had significantly lower BABS scores compared to ETAU at T2 (b = −5.2, SE = 1.6, 95% CI: −8.2, −2.1, p = .001; dppc2 = .72), and T3 (b = −4.5, SE = 1.7, 95% CI: −7.7, −1.3, p = .007; dppc2 = .62).

ART Adherence

CBT-BISC had significantly higher on-time adherence than ETAU across the active treatment period (b = 8.8, SE = 3.3, 95% CI: 2.0, 15.6, p = .01; dppc2 = .94), but no statistically significant differences were found at T3 (b = 10.7, SE = 7.1, 95% CI: −3.1, 24.6, p = .13; dppc2 = .93). CBT-BISC did not significantly differ from ETAU across the active treatment period on total adherence (b = 1.8, SE = 1.7, 95% CI: −2.8, 6.3, p = .35; dppc2 = .50), but did have significantly higher total adherence compared to ETAU at T3 (b = 8.6, SE = 4.2, 95% CI: .44, 16.8, p = .039; dppc2 = 1.35).

Depressive Symptoms

CBT-BISC did not significantly differ from ETAU at T2 on the MADRS (b = −4.9, SE = 2.8, 95% CI: −10.6, .70, p = .086; dppc2 = .87), but did have significantly lower MADRS scores compared to ETAU at T3 (b = −7.7, SE = 2.9, 95% CI: −13.3, −2.1, p = .008; dppc2 = 1.17).

Global Functioning

CBT-BICS had significantly higher GAF scores compared to ETAU at T2 (b = 12.3, SE = 3.2, 95% CI: 6.1, 18.6, p < .001; dppc2 = 2.91), and T3 (b = 15.5, SE = 4.1, 95% CI: 7.5, 23.6, p < .001; dppc2 = 3.39).

Discussion

The current study is the first known to test the efficacy of an integrated treatment for body image disturbance and ART adherence among sexual minority men living with HIV. Results indicated that the intervention was feasible, acceptable, and was generally efficacious in reducing body image disturbance and depression, while improving ART adherence. Moreover, the effect size estimates highlighted large magnitude treatment effects, which were maintained 6 months after baseline.

Participants in the CBT-BISC condition demonstrated substantial reductions in body image disturbance 3 and 6 months after baseline, with both clinician-based interviews and self-report measures. Indeed, 95% and 91% of CBT-BISC participants at 3 and 6 months, respectively, were identified as treatment responders for the primary outcome variable, using the BDD-YBOCS criteria. Further, the average percent reduction in symptoms at 3 and 6 months were 67.5% and 68.1%, respectively. A recent meta-analysis on the efficacy of CBT for BDD symptoms revealed a mean effect size of d = 1.22 at post-treatment and d = .89 at 2 to 4 months post-treatment (Harrison, Fernández de la Cruz, Enander, Radua, & Mataix-Cols, 2016). Similarly, a meta-analysis on standalone CBT intervention for body image revealed a mean effect size of d = 1.01 (Jarry & Ip, 2005). Accordingly, the present results demonstrate that CBT-BISC was highly effective in reducing body image disturbance, and the effects are consistent with, or stronger in magnitude, than other CBT treatments for body image disturbance.

Similarly, participants in the CBT-BISC condition also demonstrated substantial reductions in depressive symptoms 3 and 6 months after baseline. Although statistically significant differences from the ETAU condition were only noted at 6 months, the effect size estimates at both time points were large. Here too, effects were consistent with previous studies that have tested integrated ART adherence and depression interventions for individuals living with HIV (Safren et al., 2009, 2012), and are larger than effects typically found when treating subthreshold depression (Cuijpers, Smit, & van Straten, 2007), and depressive symptoms among individuals living with HIV (Crepaz, Passin, Herbst et al., 2008; Himelhoch, Medoff, & Oyeniyi, 2007).

Not only did CBT-BISC substantially reduce body image disturbance and depressive symptoms, but large effects were also found on clinician-rated Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF). Participants in CBT-BISC moved from GAF scores at baseline indicative of moderate/severe symptoms/impairment to mild symptoms/slight impairment. This suggests that skills learned through the intervention translated broadly to participants’ lives.

Findings regarding ART adherence varied depending on which marker of adherence was tested. One explanation for this may be that adherence at baseline, in both conditions, was high (over 90% total adherence) which is discrepant from estimates of mean adherence levels for individuals living with HIV, which are between 62% and 64% (Mills et al., 2006; Ortego et al., 2011). Use of an electronic adherence monitor, in both conditions, has been shown to have potential intervention effects itself, and given that the baseline value for adherence was defined as the two week interval between the baseline assessment and session 1, the first time point of adherence in the current study is likely an overestimate of participants’ “true” adherence. Indeed, past work with electronic adherence monitors have found significant gains in adherence solely as a function of using the monitor (Deschamps, Van Wijnaerden, Denhaerynck, De Geest, & Vandamme, 2006; Wagner & Ghosh-Dastidar, 2002), which tend to last for one to two months. The high levels of total adherence found in the current study may have created a ceiling effect.

However, with respect to the adherence findings, the CBT-BISC participants were generally able to maintain their high levels of total adherence (and even increase it slightly) over the course of the study, whereas a downward trajectory was noted among ETAU participants over time. The magnitude of the adherence effect varied from d = .50 to 1.35. Generally, however, the size of the adherence effects were large, and equivalent, if not greater, than effects typically found for ART adherence interventions, which, on average, yield effects of d = .62 (e.g., Amico et al., 2006). These effects were also consistent with those found for interventions that simultaneously target depression and adherence (e.g., Safren et al., 2009, 2012). Additionally, the raw difference in adherence change scores between conditions was 11.17% from baseline to 6 months for total adherence, and 16.00% from baseline to 6 months for on-time adherence. This highlights that the adherence improvement seen in CBT-BISC may constitute a clinically meaningful effect, as improvements in adherence of roughly 10% correspond to improvements in virologic suppression (Bangsberg, 2006; Liu et al., 2006; Viswanathan et al., 2015).

Despite the promising findings revealed in the current study, there are also important limitations to note. Although substantial differences in adherence were noted, the sample overall possessed good HIV health, as evidenced by only 2 participants (5%) having a detectable vial load. This precluded examining viral load as a biological measure of adherence. Thus, future studies sampling participants with detectable viral loads would allow for analysis of viral suppression as a marker of ART adherence. Additionally, given that the majority of the sample was virally suppressed, it is unlikely that participants would be considered at-risk for transmitting HIV to sexual partners, and thus, we were unable to assess the intervention’s impact of HIV sexual transmission risk. Also, given the nature of the design, it is not clear that intervention effects were driven by CBT-BISC, per se, but rather, through common psychotherapy factors inherent with meeting weekly with a clinician. However, even though the ETAU condition was not fully time and attention-matched, participants did have much more contact with study staff then is typical in TAU conditions. For instance, ETAU participants met with study staff for 6 sessions (compared to 12 sessions in CBT-BISC), and although skills for achieving adherence were not discussed during these sessions, adherence scores were reviewed. Additionally, the mechanisms driving treatment effects are unclear. Future studies assessing the longitudinal mechanisms of changes within CBT-BISC could address whether improvements in body image disturbance, depressive symptoms, or both, predict changes in ART adherence. Future studies may also wish to assess whether an intervention that simultaneously targeted depression and body image disturbance would improve HIV outcomes further.

In sum, the findings from the current study indicate that CBT-BISC is feasible, acceptable, and displayed preliminary efficacy in improving body image disturbance, depressive symptoms, general functioning, and ART adherence among sexual minority men living with HIV. Generally the size of the treatment effects, across outcomes, was large in magnitude. However, the small sample size leaves questions regarding the generalizability of the findings. Previous correlational studies have found significant associations between body image disturbance and ART non-adherence; however, this is the first known study to demonstrate a positive impact on adherence when body image concerns are addressed.

Figure 2.

Body Image Disturbance, Depression, and ART Adherence by Time and Condition

Acknowledgments

Funding from this project came from K23MH096647. Author time for Dr. Safren was supported by K24DA040489 (formally K24MH094214). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Mental Health or the National Institutes of Health.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. Global assessment of functioning scale; p. 34. text revision. [Google Scholar]

- Amico KR, Harman JJ, Johnson BT. Efficacy of antiretroviral therapy adherence interventions: A research synthesis of trials, 1996 to 2004. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes (1999) 2006;41:285–297. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000197870.99196.ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amorim P. Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI): Validation of a short structured diagnostic psychiatric interview. Revista Brasileira de Psiquiatria. 2000;22:106–115. doi: 10.1590/S1516-44462000000300003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bangsberg DR. Less than 95% adherence to nonnucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitor therapy can lead to viral suppression. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2006;43:939–941. doi: 10.1086/507526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blashill AJ, Bedoya CA, Mayer KH, O’Cleirigh C, Pinkston MM, Remmert JE, … Safren SA. Psychosocial syndemics are additively associated with worse ART adherence in HIV-infected individuals. AIDS and Behavior. 2015;19:981–986. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0925-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blashill AJ, Gordon JR, Safren SA. Appearance concerns and psychological distress among HIV-infected individuals with injection drug use histories: Prospective analyses. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2012;26:557–561. doi: 10.1089/apc.2012.0122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blashill AJ, Goshe BM, Robbins GK, Mayer KH, Safren SA. Body image disturbance and health behaviors among sexual minority men living with HIV. Health Psychology. 2015;33:677–680. doi: 10.1037/hea0000081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blashill AJ, Vander Wal JS. The role of body image dissatisfaction and depression on HAART adherence in HIV positive men: Tests of mediation models. AIDS and Behavior. 2010;14:280–288. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9630-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blashill AJ, Wilson JM, Baker JS, Mayer KH, Safren SA. Assessing appearance-related disturbances in HIV-infected men who have sex with men (MSM): Psychometrics of the body change and distress questionnaire-short form (ABCD-SF) AIDS and Behavior. 2014;18:1075–1084. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0620-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cafri G, Yamamiya Y, Brannick M, Thompson JK. The influence of sociocultural factors on body image: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2005;12:421–433. doi: 10.1093/clipsy.bpi053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Caron-Debarle M, Lagathu C, Boccara F, Vigouroux C, Capeau J. HIV-associated lipodystrophy: From fat injury to premature aging. Trends in Molecular Medicine. 2010;16:218–229. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2010.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carper TL, Negy C, Tantleff-Dunn S. Relations among media influence, body image, eating concerns, and sexual orientation in men: A preliminary investigation. Body Image. 2010;7:301–309. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2010.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cash TF. The body image workbook: An 8-step program for learning to like your looks. 2. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Cash TF, Phillips KA, Santos MT, Hrabosky JI. Measuring “negative body image”: Validation of the Body Image Disturbance Questionnaire in a nonclinical population. Body Image. 2004;1:363–372. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2004.10.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. A power primer. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;112:155–159. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crepaz N, Passin WF, Herbst JH, Rama SM, Malow RM, Purcell DW … HIV/AIDS Prevention Research Synthesis Team. Meta-analysis of cognitive-behavioral interventions on HIV-positive persons’ mental health and immune functioning. Health Psychology. 2008;27:4–14. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.1.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuijpers P, Smit F, van Straten A. Psychological treatments of subthreshold depression: A meta-analytic review. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2007;115:434–441. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2007.00998.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson J, Turnbull CD, Strickland R, Miller R, Graves K. The Montgomery-Asberg Depression Scale: Reliability and validity. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 1986;73:544–548. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1986.tb02723.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deschamps AE, Van Wijngaerden E, Denhaerynck K, De Geest S, Vandamme AM. Use of electronic monitoring induces a 40-day intervention effect in HIV patients. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes (1999) 2006;43:247–248. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000246034.86135.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisen JL, Phillips KA, Baer L, Beer DA, Atala KD, Rasmussen SA. The Brown Assessment of Beliefs Scale: Reliability and validity. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 1998;155:102–108. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.1.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engeln-Maddox R, Miller SA, Doyle DM. Tests of objectification theory in gay, lesbian, and heterosexual community samples: Mixed evidence for proposed pathways. Sex Roles. 2011;65:518–532. doi: 10.1007/s11199-011-9958-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Feingold A. A regression framework for effect size assessments in longitudinal modeling of group differences. Review of General Psychology. 2013;17:111–121. doi: 10.1037/a0030048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finitsis DJ, Pellowski JA, Johnson BT. Text message intervention designs to promote adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART): A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PloS One. 2014;9:e88166. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0088166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JB. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV-TR axis I disorders, research version, patient edition (SCID-I/P) New York: New York State Psychiatric Institute Biometrics Research; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Gill CJ, Sabin LL, Hamer DH, Keyi X, Jianbo Z, Li T, … Desilva MB. Importance of dose timing to achieving undetectable viral loads. AIDS and Behavior. 2010;14:785–793. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9555-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez JS, Batchelder AW, Psaros C, Safren SA. Depression and HIV/AIDS treatment nonadherence: A review and meta-analysis. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes (1999) 2011;58:181–187. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31822d490a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham JW, Olchowski AE, Gilreath TD. How many imputations are really needed? Some practical clarifications of multiple imputation theory. Prevention Science. 2007;8:206–213. doi: 10.1007/s11121-007-0070-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Günthard HF, Saag MS, Benson CA, del Rio C, Eron JJ, Gallant JE, … Volberding PA. Antiretroviral drugs for treatment and prevention of HIV infection in adults 2016 recommendations of the International Antiretroviral Society-USA panel. JAMA. 2016;316:191–210. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.8900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haberer JE, Kahane J, Kigozi I, Emenyonu N, Hunt P, Martin J, Bangsberg DR. Real-time adherence monitoring for HIV antiretroviral therapy. AIDS and Behavior. 2010;14:1340–1346. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9799-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haberer JE, Kiwanuka J, Nansera D, Muzoora C, Hunt PW, So J, … Bangsberg DR. Realtime adherence monitoring of antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected adults and children in rural Uganda. AIDS (London, England) 2013;27:2166–2168. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328363b53f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison A, Fernández de la Cruz L, Enander J, Radua J, Mataix-Cols D. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for body dysmorphic disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clinical Psychology Review. 2016;48:43–51. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2016.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilsenroth MJ, Ackerman SJ, Blagys MD, Baumann BD, Baity MR, Smith SR, … Holdwick DJ. Reliability and validity of DSM-IV axis V. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;157:1858–1863. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.11.1858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Himelhoch S, Medoff DR, Oyeniyi G. Efficacy of group psychotherapy to reduce depressive symptoms among HIV-infected individuals: A systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2007;21:732–739. doi: 10.1089/apc.2007.0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ickovics JR, Hamburger ME, Vlahov D, Schoenbaum EE, Schuman P, Boland RJ … HIV Epidemiology Research Study Group. Mortality, CD4 cell count decline, and depressive symptoms among HIV-seropositive women: Longitudinal analysis from the HIV Epidemiology Research Study. JAMA. 2001;285:1466–1474. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.11.1466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarry JL, Ip K. The effectiveness of stand-alone cognitive-behavioural therapy for body image: A meta-analysis. Body Image. 2005;2:317–331. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2005.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones SH, Thornicroft G, Coffey M, Dunn G. A brief mental health outcome scale-reliability and validity of the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science. 1995;166:654–659. doi: 10.1192/bjp.166.5.654. doi:0.1192/bjp.166.5.654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan A, Khan SR, Shankles EB, Polissar NL. Relative sensitivity of the Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale, the Hamilton Depression rating scale and the Clinical Global Impressions rating scale in antidepressant clinical trials. International Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2002;17:281–285. doi: 10.1097/00004850-200211000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leserman J. Role of depression, stress, and trauma in HIV disease progression. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2008;70:539–545. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181777a5f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Golin CE, Miller LG, Hays RD, Beck CK, Sanandaji S, … Wenger NS. A comparison study of multiple measures of adherence to HIV protease inhibitors. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2001;134:968–977. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-134-10-200105150-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Miller LG, Hays RD, Golin CE, Wu T, Wenger NS, Kaplan AH. Repeated measures longitudinal analyses of HIV virologic response as a function of percent adherence, dose timing, genotypic sensitivity, and other factors. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes (1999) 2006;41:315–322. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000197071.77482.6e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills EJ, Nachega JB, Buchan I, Orbinski J, Attaran A, Singh S, … Bangsberg DR. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy in sub-Saharan Africa and North America: A meta-analysis. JAMA. 2006;296:679–690. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.6.679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery SA, Asberg M. A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science. 1979;134:382–389. doi: 10.1192/bjp.134.4.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris SB. Estimating effect sizes from pretest-posttest-control group designs. Organizational Research Methods. 2008;11:364–386. doi: 10.1177/1094428106291059. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison MA, Morrison TG, Sager CL. Does body satisfaction differ between gay men and lesbian women and heterosexual men and women? A meta-analytic review. Body Image. 2004;1:127–138. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2004.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller MJ, Himmerich H, Kienzle B, Szegedi A. Differentiating moderate and severe depression using the Montgomery-Asberg depression rating scale (MADRS) Journal of Affective Disorders. 2003;77:255–260. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2004.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Mental Health. CGI (Clinical Global Impression) scale—NIMH. Psychopharmacology Bulletin. 1985;21:839–844. [Google Scholar]

- Ortego C, Huedo-Medina TB, Llorca J, Sevilla L, Santos P, Rodríguez E, … Vejo J. Adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART): A meta-analysis. AIDS and Behavior. 2011;15:1381–1396. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-9942-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons JT, Rosof E, Mustanski B. The temporal relationship between alcohol consumption and HIV-medication adherence: A multilevel model of direct and moderating effects. Health Psychology. 2008;27:628–637. doi: 10.1037/a0012664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peplau LA, Frederick DA, Yee C, Maisel N, Lever J, Ghavami N. Body image satisfaction in heterosexual, gay, and lesbian adults. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2009;38:713–725. doi: 10.1007/s10508-008-9378-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips KA, Diaz SF. Gender differences in body dysmorphic disorder. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1997;185:570–577. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199709000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips KA, Hart AS, Menard W. Psychometric evaluation of the Yale–Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale Modified for Body Dysmorphic Disorder (BDD-YBOCS) Journal of Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders. 2014;3:205–208. doi: 10.1016/j.jocrd.2014.04.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips KA, Hollander E, Rasmussen SA, Aronowitz BR, DeCaria C, Goodman WK. A severity rating scale for body dysmorphic disorder: Development, reliability, and validity of a modified version of the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale. Psychopharmacology Bulletin. 1997;33:17–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price J, Hoy J, Ridley E, Nyulasi I, Paul E, Woolley I. Changes in the prevalence of lipodystrophy, metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease risk in HIV-infected men. Sexual Health. 2015;12:240–248. doi: 10.1071/SH14084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodger AJ, Cambiano V, Bruun T, Vernazza P, Collins S, van Lunzen J … PARTNER Study Group. Sexual activity without condoms and risk of HIV transmission in serodifferent couples when the HIV-positive partner is using suppressive antiretroviral therapy. JAMA. 2016;316:171–181. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.5148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rounsaville BJ, Carroll KM, Onken LS. A stage model of behavioral therapies research: Getting started and moving on from stage I. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2001;8:133–142. doi: 10.1093/clipsy.8.2.133. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin DB. Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Safren SA, O’Cleirigh CM, Bullis JR, Otto MW, Stein MD, Pollack MH. Cognitive behavioral therapy for adherence and depression (CBT-AD) in HIV-infected injection drug users: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2012;80:404–415. doi: 10.1037/a0028208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safren SA, O’Cleirigh C, Tan JY, Raminani SR, Reilly LC, Otto MW, Mayer KH. A randomized controlled trial of cognitive behavioral therapy for adherence and depression (CBT-AD) in HIV-infected individuals. Health Psychology. 2009;28:1–10. doi: 10.1037/a0012715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safren SA, Otto MW, Worth JL. Life-steps: Applying cognitive behavioral therapy to HIV medication adherence. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 1999;6:332–341. doi: 10.1016/S1077-7229(99)80052-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma A, Howard AA, Klein RS, Schoenbaum EE, Buono D, Webber MP. Body image in older men with or at-risk for HIV infection. AIDS Care. 2007;19:235–241. doi: 10.1080/09540120600774354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan D, Lecrubier Y, Harnett Sheehan K, Janavs J, Weiller E, Keskiner A, … Dunbar G. The validity of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) according to the SCID-P and its reliability. European Psychiatry. 1997;12:232–241. doi: 10.1016/S0924-9338(97)83297-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Harnett K, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, … Dunbar GC. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I): The development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 1998;59:22–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simoni JM, Amico KR, Pearson CR, Malow R. Strategies for promoting adherence to antiretroviral therapy: A review of the literature. Current Infectious Disease Reports. 2008;10:515–521. doi: 10.1007/s11908-008-0083-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sin NL, DiMatteo MR. Depression treatment enhances adherence to antiretroviral therapy: A meta-analysis. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2014;47:259–269. doi: 10.1007/s12160-013-9559-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using Multivariate Statistics. 5. Boston, MA: Pearson Education; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JK, Heinberg LJ, Altabe MN, Tantleff-Dunn S. Exacting beauty: Theory, assessment and treatment of body image disturbance. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Viswanathan S, Justice AC, Alexander GC, Brown TT, Gandhi NR, McNicholl IR, … Jacobson LP. Adherence and HIV RNA suppression in the current era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes (1999) 2015:493–498. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner GJ, Ghosh-Dastidar B. Electronic monitoring: Adherence assessment or intervention? HIV Clinical Trials. 2002;3:45–51. doi: 10.1310/XGXU-FUDK-A9QT-MPTF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelm S, Phillips KA, Steketee G. A cognitive behavioral treatment manual for body dysmorphic disorder. New York: Guilford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]