Abstract

Here, we performed a systematic analysis to discover new biomarkers of overall survival and tumor progression in ovarian cancer patients. More specifically, we determined whether nuclear-encoded mitochondrial genes related to mitochondrial biogenesis and function are effective in predicting clinical outcome in ovarian cancer. As a consequence, we are able to provide in silico validation of the prognostic value of these mitochondrial markers, in a well-defined population of ovarian cancer patients. Towards this end, we used a group of N=111 ovarian cancer patients (serous type; stage III), with optimal de-bulking. Importantly, in this group of cancer patients, CA125 and PCNA (conventional markers) were associated with poor overall survival, as would be expected. Using this approach, we identified >100 new individual mitochondrial gene probes that effectively predicted significantly reduced overall survival, with hazard-ratios (HR) of up to 3.68 (p < 9.8e-05). These mitochondrial mRNA transcripts included membrane proteins, chaperones, anti-oxidant enzymes, as well as mitochondrial ribosomal proteins (MRPs) and key members of the OXPHOS (I-V) complexes. Based on this bioinformatics analysis and in silico validation, we conclude that mitochondrial biogenesis and OXPHOS should both be considered as new therapeutic targets, for the more effective treatment of human ovarian cancers. The mitochondrial biomarkers that we have identified could also be employed as new companion diagnostics to assist oncologists in: i) more accurately predicting clinical outcomes and ii) improving the response to therapy, in ovarian cancer patients.

Keywords: ovarian cancer, mitochondrial biomarkers, treatment failure, relapse, recurrence

INTRODUCTION

Drug-resistance dramatically limits the effectiveness of most cancer therapies, and especially for ovarian cancer patients [1, 2]. As such, treatment failure remains a significant barrier to successful cancer therapy and precision medicine [3, 4]. As a result, new biomarkers are urgently required for the treatment stratification of ovarian cancer patients, into different risk sub-groups at diagnosis (high-risk versus low-risk) [5].

In this report, we tested the hypothesis that mitochondrial markers might have prognostic value for the identification of high-risk ovarian cancer patients, with increased progression and poor overall survival. For this purpose, we used a data-mining and informatics strategy to determine the potential effectiveness of mitochondrial gene transcripts, in predicting clinical outcome.

Our results indicate that >100 mitochondrial gene probes can be used individually or in various combinations, to predict poor overall survival in ovarian cancer patients. Based on these current findings, we speculate that mitochondrial biogenesis and/or OXPHOS could be targeted therapeutically to prevent ovarian cancer recurrence and extend overall survival.

RESULTS

Prognostic value of conventional markers (CA125 and PCNA) in the patient population

To identify novel biomarkers for ovarian cancers, we employed publically available transcriptional profiling data from the tumors of patients with serous ovarian cancer (stage III), with optimal de-bulking, low CA125 levels at diagnosis, and 5-years of follow-up data (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Summary illustrating our systematic approach to ovarian cancer biomarker discovery.

For this analysis, we chose to focus on serous ovarian cancer patients, with optimal de-bulking, and 5-years of follow-up data (N = 111). In this context, we evaluated the prognostic value of mitochondrial markers for predicting overall survival (OS), progression-free survival (PFS) and post-progression survival (PPS).

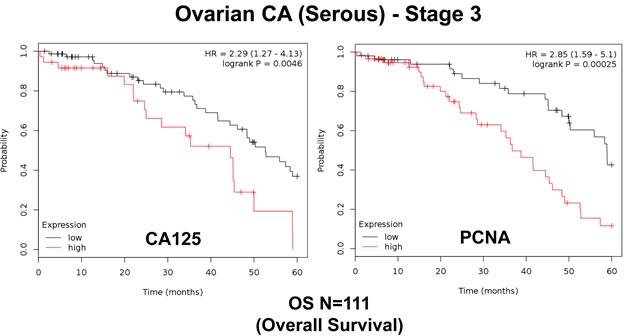

First, we assessed the prognostic value of CA125 in this context. The results of this analysis are shown in Figure 2 and Table 1. Note that the hazard-ratio (HR) for CA125 was 2.29 (p = 0.005) for overall survival (OS). As proliferative markers are often used as key endpoints in Phase II clinical trials, we next assessed the prognostic value of Ki67 and PCNA. Figure 2 and Table 2 both show the prognostic value of these markers. The results with Ki67 were not significant, but PCNA showed a hazard-ratio of 2.85 (p = 0.00025). Similarly, we determined the utility of macrophage-specific markers of inflammation. However, Table 3 shows that that CD68 and CD163 did not show significant prognostic value.

Figure 2. Traditional markers (CA125 and PCNA) predict poor overall survival in ovarian cancer patients.

We assessed the predictive value of CA125 and PCNA in N = 111 ovarian cancer patients, with optimal de-bulking. Note that high transcript levels of CA125 and PCNA are associated with significantly reduced overall survival.

Table 1. Prognostic value of CA125 in ovarian cancer.

| Gene Probe ID | Symbol | Hazard-Ratio | Log-Rank Test |

|---|---|---|---|

| 201383_s_at | CA125 | 2.29 | 0.005 |

| 220196_at | CA125 | 1.35 | 0.29 |

| 201384_s_at | CA125 | 0.66 | 0.15 |

Table 2. Prognostic value of KI67 in ovarian cancer.

| Gene Probe ID | Symbol | Hazard-Ratio | Log-Rank Test |

|---|---|---|---|

| 212020_s_at | MKI67 | 1.50 | 0.17 |

| 212023_s_at | MKI67 | 1.47 | 0.21 |

| 212021_s_at | MKI67 | 0.75 | 0.44 |

| 212022_s_at | MKI67 | 0.65 | 0.16 |

Table 3. Prognostic value of PCNA and markers of inflammation in ovarian cancer.

| Gene Probe ID | Symbol | Hazard-Ratio | Log-Rank Test |

|---|---|---|---|

| 201202_at | PCNA | 2.85 | 0.0003 |

| 217400_at | PCNA | 2.48 | 0.001 |

| 215049_x_at | CD163 | 1.43 | 0.20 |

| 203645_s_at | CD163 | 1.45 | 0.19 |

| 216233_at | CD163 | 0.47 | 0.024 |

| 203507_at | CD68 | 0.57 | 0.095 |

Thus, a subset of conventional markers (CA125 and PCNA) can be used to predict overall survival in ovarian cancer patients.

Prognostic value of individual mitochondrial markers

Our hypothesis is that increased mitochondrial biogenesis drives poor overall survival in ovarian cancer patients. To directly test this hypothesis, we next determined the prognostic value of a series of mitochondrial markers.

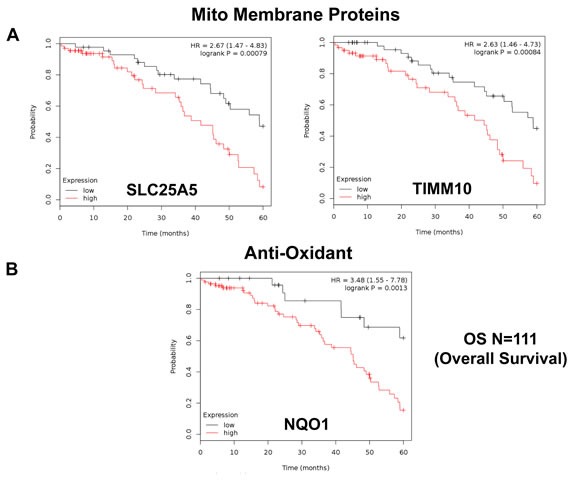

Firstly, we interrogated the utility of the behavior of mitochondrial chaperones and mitochondrial membrane proteins. Table 4 and Figure 3A both show that SLC25A5 and TIMM10 have significant prognostic value, with hazard-ratios of 2.67 and 2.63, respectively. Other members of the SLC25A, TIMM, TOMM and VDAC families also had prognostic value. Mitochondrial-related antioxidant proteins (NQO1 and SOD2), as well as mitochondrial creatine kinase, also had significant value (summarized in Table 4 and Figure 3B).

Table 4. Prognostic value of chaperones, mitochondrial membrane proteins, anti-oxidants and creatine kinase.

| Gene Probe ID | Symbol | Hazard-Ratio | Log-Rank Test |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chaperones/HSPs | |||

| 200691_s_at | HSPA9 | 1.77 | 0.047 |

| Membrane Proteins | |||

| 200955_at | IMMT | 2.61 | 0.002 |

| 218408_at | TIMM10 | 2.63 | 0.0008 |

| 201821_s_at | TIMM17A | 2.46 | 0.003 |

| 217981_s_at | TIMM10B | 1.94 | 0.05 |

| 218118_s_at | TIMM23 | 1.79 | 0.05 |

| 201519_at | TOMM70A | 2.28 | 0.005 |

| 211662_s_at | VDAC2 | 2.32 | 0.01 |

| 208845_at | VDAC3 | 2.07 | 0.01 |

| 208846_s_at | VDAC3 | 1.96 | 0.048 |

| 200657_at | SLC25A5 | 2.67 | 0.0008 |

| 221020_s_at | SLC25A32 | 1.98 | 0.05 |

| Anti-Oxidant Proteins | |||

| 201468_s_at | NQO1 | 3.48 | 0.001 |

| 210519_s_at | NQO1 | 2.37 | 0.006 |

| 215223_s_at | SOD2 | 1.82 | 0.048 |

| Mitochondrial Creatine Kinase | |||

| 205295_at | CKMT2 | 2.27 | 0.0035 |

Figure 3. Mitochondrial membrane proteins and NQO1 are associated with poor clinical outcome in ovarian cancer patients.

A. Note that that high transcript levels of SLC25A5 and TIMM10 are associated with significantly reduced overall survival. B. Note that that high transcript levels of NQO1 are associated with significantly reduced overall survival.

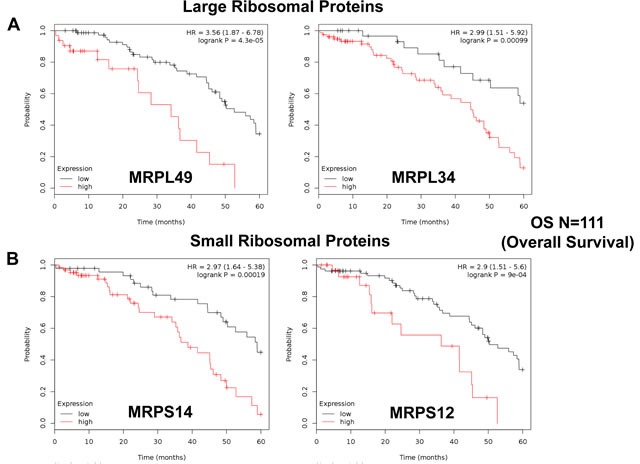

Next, we carefully examined the prognostic value of mitochondrial ribosomal proteins (MRPs). They functionally control the biosynthesis of essential components of the OXPHOS complexes, driving mitochondrial biogenesis (Table 5). Ten members of the large subunit (MRPLs) showed significant prognostic value, with hazard-ratios between 3.56 and 1.90. Interestingly, MRPL49 had the best prognostic value. Eleven different members of the small subunit (MRPSs) showed significant prognostic value, with hazard-ratios between 2.90 and 1.88. In summary, twenty-one different MRPs all predicted poor overall survival. Kaplan-Meier curves for representative examples are shown in Figure 4, panels A & B.

Table 5. Prognostic value of mitochondrial ribosomal proteins.

| Gene Probe ID | Symbol | Hazard-Ratio | Log-Rank Test |

|---|---|---|---|

| Large Ribosomal Subunit | |||

| 201717_at | MRPL49 | 3.56 | 4.3e-05 |

| 221692_s_at | MRPL34 | 2.99 | 0.001 |

| 218890_x_at | MRPL35 | 2.48 | 0.002 |

| 213897_s_at | MRPL23 | 2.48 | 0.01 |

| 217907_at | MRPL18 | 2.36 | 0.006 |

| 218281_at | MRPL48 | 2.29 | 0.007 |

| 222216_s_at | MRPL17 | 2.17 | 0.007 |

| 217980_s_at | MRPL16 | 2.17 | 0.008 |

| 219162_s_at | MRPL11 | 2.14 | 0.02 |

| 218105_s_at | MRPL4 | 1.90 | 0.03 |

| Small Ribosomal Subunit | |||

| 203800_s_at | MRPS14 | 2.97 | 0.0002 |

| 204331_s_at | MRPS12 | 2.90 | 9e-04 |

| 210008_s_at | MRPS12 | 2.46 | 0.0035 |

| 221688_s_at | MRPS4 | 2.88 | 0.002 |

| 219819_s_at | MRPS28 | 2.64 | 0.0008 |

| 218001_at | MRPS2 | 2.15 | 0.01 |

| 219220_x_at | MRPS22 | 2.13 | 0.025 |

| 218654_s_at | MRPS33 | 2.05 | 0.02 |

| 217942_at | MRPS35 | 2.05 | 0.03 |

| 212604_at | MRPS31 | 2.02 | 0.02 |

| 221437_s_at | MRPS15 | 1.88 | 0.05 |

Figure 4. Mitochondrial ribosomal proteins (MRPs) are associated with poor clinical outcome in ovarian cancer patients.

A. Note that high transcript levels of MRPL49 and MRPL34 predict significantly reduced overall survival. B. Similarly, high transcript levels of MRPS14 and MRPS12 predict significantly reduced overall survival.

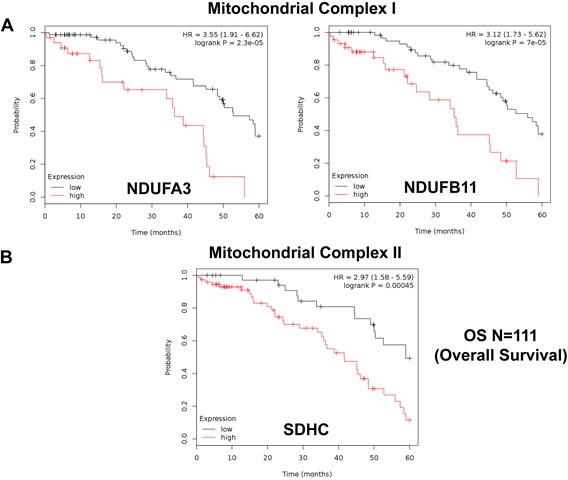

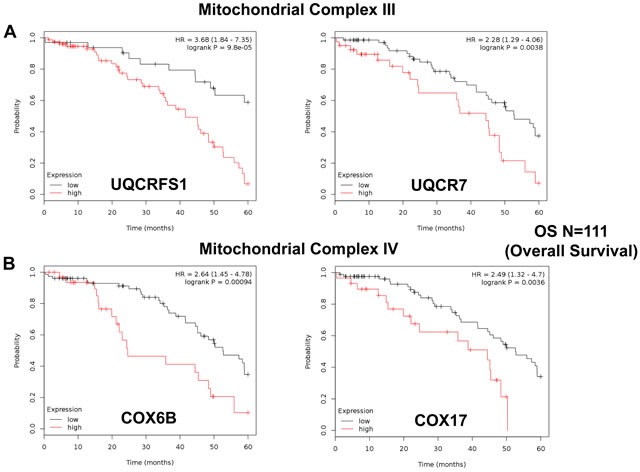

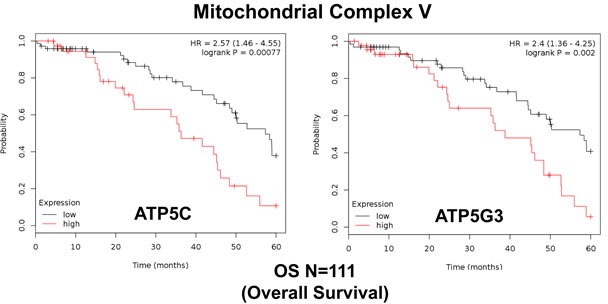

Similarly, we also determined the prognostic value of key components of the OXPHOS complex. These results are summarized in Table 6. Surprisingly, 52 different gene probes for the OXPHOS complexes showed hazard-ratios between 3.68 and 1.76. Complex I had the most subunits with significant prognostic value (21 in total). However, UQCRFS1 (complex III) had the best individual prognostic value (HR = 3.68; p = 9.8e-05). NDUFA3 (complex I) also showed significant prognostic value (HR = 3.55; p = 2.3e-05). Kaplan-Meier curves for members of complex I and II are shown in Figure 5A & 5B, while results with members of complex III and IV are shown in Figure 6A & 6B. Results with complex V are shown in Figure 7.

Table 6. Prognostic value of mitochondrial OXPHOS complexes.

| Gene Probe ID | Symbol | Hazard-Ratio | Log-Rank Test |

|---|---|---|---|

| Complex I | |||

| 218563_at | NDUFA3 | 3.55 | 2.3e-05 |

| 218320_s_at | NDUFB11 | 3.12 | 7e-05 |

| 201740_at | NDUFS3 | 2.93 | 0.001 |

| 218200_s_at | NDUFB2 | 2.60 | 0.001 |

| 203371_s_at | NDUFB3 | 2.56 | 0.0008 |

| 203189_s_at | NDUFS8 | 2.43 | 0.002 |

| 218201_at | NDUFB2 | 2.43 | 0.002 |

| 203613_s_at | NDUFB6 | 2.43 | 0.008 |

| 202000_at | NDUFA6 | 2.43 | 0.0015 |

| 202785_at | NDUFA7 | 2.30 | 0.01 |

| 220864_s_at | NDUFA13 | 2.25 | 0.006 |

| 209303_at | NDUFS4 | 2.20 | 0.009 |

| 218160_at | NDUFA8 | 2.16 | 0.008 |

| 203190_at | NDUFS8 | 2.15 | 0.01 |

| 202941_at | NDUFV2 | 2.13 | 0.02 |

| 208714_at | NDUFV1 | 2.07 | 0.03 |

| 209224_s_at | NDUFA2 | 2.03 | 0.044 |

| 211752_s_at | NDUFS7 | 1.98 | 0.02 |

| 217860_at | NDUFA10 | 1.95 | 0.037 |

| 202298_at | NDUFA1 | 1.91 | 0.03 |

| 208969_at | NDUFA9 | 1.89 | 0.26 |

| 201966_at | NDUFS2 | 1.86 | 0.035 |

| Complex II | |||

| 210131_x_at | SDHC | 2.97 | 0.0005 |

| 202004_x_at | SDHC | 2.78 | 0.0005 |

| 202675_at | SDHB | 1.83 | 0.04 |

| Complex III | |||

| 208909_at | UQCRFS1 | 3.68 | 9.8e-05 |

| 201568_at | UQCR7 | 2.28 | 0.004 |

| 209065_at | UQCR6 | 2.12 | 0.04 |

| 202090_s_at | UQCR | 1.86 | 0.04 |

| 212600_s_at | UQCR2 | 1.76 | 0.047 |

| Complex IV | |||

| 201441_at | COX6B | 2.64 | 0.0009 |

| 203880_at | COX17 | 2.49 | 0.004 |

| 203858_s_at | COX10 | 2.47 | 0.002 |

| 211025_x_at | COX5B | 2.34 | 0.004 |

| 202343_x_at | COX5B | 2.32 | 0.004 |

| 202110_at | COX7B | 2.30 | 0.02 |

| 218057_x_at | COX4NB | 2.08 | 0.01 |

| 202698_x_at | COX4I1 | 1.89 | 0.03 |

| 201119_s_at | COX8A | 1.87 | 0.04 |

| 204570_at | COX7A | 1.76 | 0.05 |

| Complex V | |||

| 208870_x_at | ATP5C | 2.57 | 0.0008 |

| 213366_x_at | ATP5C | 2.44 | 0.002 |

| 205711_x_at | ATP5C | 2.08 | 0.01 |

| 207507_s_at | ATP5G3 | 2.40 | 0.002 |

| 210453_x_at | ATP5L | 2.35 | 0.003 |

| 208746_x_at | ATP5L | 2.24 | 0.005 |

| 207573_x_at | ATP5L | 2.20 | 0.006 |

| 208972_s_at | ATP5G | 2.15 | 0.007 |

| 207508_at | ATP5G3 | 2.12 | 0.01 |

| 202961_s_at | ATP5J2 | 1.91 | 0.02 |

| 217848_s_at | PPA1 | 1.89 | 0.03 |

| 202325_s_at | ATP5J | 1.78 | 0.05 |

Figure 5. Mitochondrial complex I and II proteins are associated with poor clinical outcome in ovarian cancer patients.

A. Note that high levels of NDUFA3 and NDUFB11 predict significantly reduced overall survival. B. Similarly, high levels of SDHC predict significantly reduced overall survival.

Figure 6. Mitochondrial complex III and IV proteins are associated with poor clinical outcome in ovarian cancer patients.

A. Note that high levels of UQCRFS1 and UQCR7 predict significantly reduced overall survival. B. Similarly, high levels of COX6B and COX17 predict significantly reduced overall survival.

Figure 7. Mitochondrial complex V proteins are associated with poor clinical outcome in ovarian cancer patients.

Note that high levels of ATP5C and ATP5G3 predict significantly reduced overall survival.

Three new mitochondrial gene signatures for predicting overall survival, recurrence and the response to therapy

To significantly amplify the prognostic power of these unique mitochondrial markers, we then combined the most promising markers and to derive three new mitochondrial gene signatures.

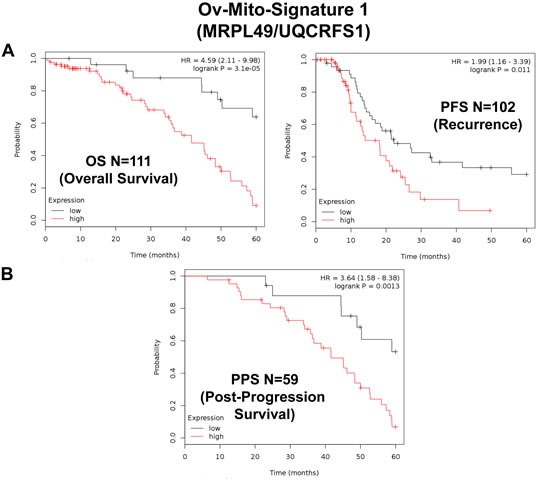

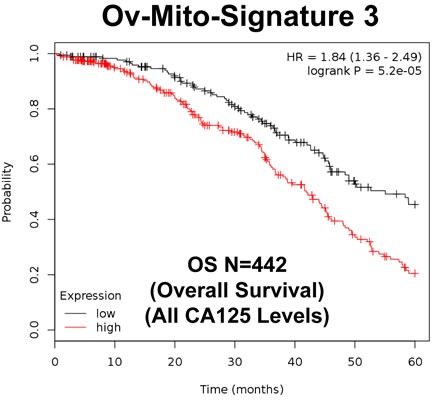

Ov-Mito-Signature-1 contains 2 genes (MRPL49/UQCRFS1). One component is an MRPL, while the other is part of the OXPHOS machinery (complex III). Ov-Mito-Signature-2 also consists of 2 genes (NDUFA3/UQCRFS1). Both components are part of the OXPHOS machinery (complexes I and III). In addition, Ov-Mito-Signature-3 consists of 3 genes (NDUFA3/UQCRFS1/PCNA), namely 2 mitochondrial genes and a proliferative marker (PCNA) (See Tables 7-9). K-M curves for these three signatures are shown in Figures 8-14.

Table 7. Prognostic value of ovarian mitochondrial signature 1.

| Gene Probe ID | Symbol | Hazard-Ratio | Log-Rank Test |

|---|---|---|---|

| 208909_at | UQCRFS1 | 3.68 | 9.8e-05 |

| 201717_at | MRPL49 | 3.56 | 4.3e-05 |

| Combination | 4.59 | 3.1e-05 |

Table 9. Prognostic value of ovarian mitochondrial signature 3.

| Gene Probe ID | Symbol | Hazard-Ratio | Log-Rank Test |

|---|---|---|---|

| 208909_at | UQCRFS1 | 3.68 | 9.8e-05 |

| 218563_at | NDUFA3 | 3.55 | 2.3e-05 |

| 201202_at | PCNA | 2.85 | 0.0003 |

| Combination | 5.63 | 7.6e-06 |

Figure 8. Ov-Mito-Signature 1 predicts patient outcome in ovarian cancer patients.

Note that high levels of Ov-Mito-Signature 1 (MRPL49/UQCRFS1) effectively predicts overall survival (OS), progression-free survival (PFS) and post-progression survival (PPS). OS and PFS are shown in panel A. PPS is shown in panel B.

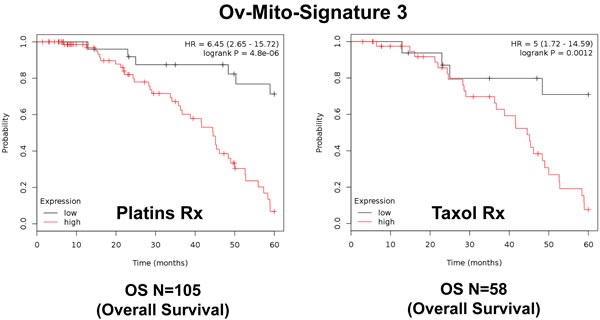

Figure 14. Ov-Mito-Signature 3 predicts patient outcome in ovarian cancer patients.

Note that high levels of Ov-Mito-Signature 3 (NDUFA3/UQCRFS1/PCNA) effectively predicts overall survival (OS), in a larger group of ovarian cancer patients (N = 442).

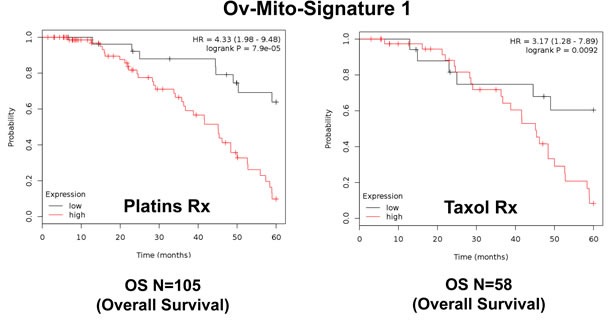

Importantly, Ov-Mito-Signature-1 yielded a significantly improved hazard-ratio for overall survival of 4.59 (p = 3.1e-05) (Table 7 and Figure 8A, left). It was also highly predictive for progression-free survival (Figure 8A, right) and post-progression survival (Figure 8B), in the same group of patients. In addition, it effectively predicted the response to chemotherapy and treatment failure, in patients that received “Platin-derivatives” or “Taxol” (Figure 9).

Figure 9. Ov-Mito-Signature 1 predicts the response to therapy in ovarian cancer patients.

Note that high levels of Ov-Mito-Signature 1 (MRPL49/UQCRFS1) effectively predicts drug-resistance and treatment failure, illustrated here as overall survival. Results with Platin and Taxol therapy (Rx) are shown.

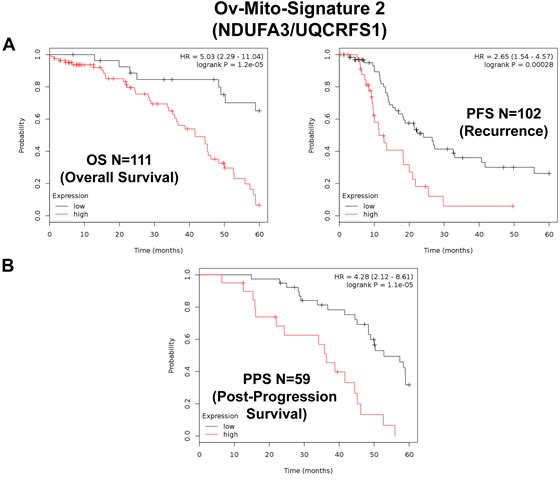

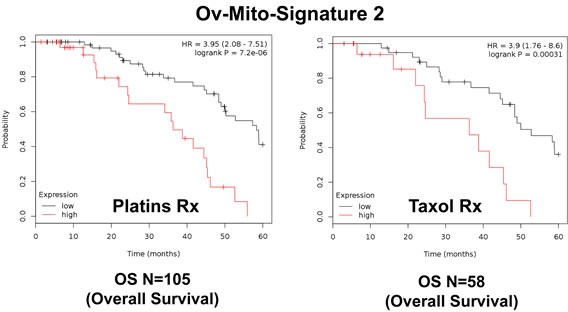

Similarly, Ov-Mito-Signature-2 showed a hazard-ratio for overall survival of 5.03 (p = 1.2e-05) (Table 8 and Figure 10A, left). Ov-Mito-Signature-2 was also highly predictive for progression-free survival (Figure 10A, right) and post-progression survival (Figure 10B). Also, it effectively predicted the response to chemotherapy (Figure 11).

Table 8. Prognostic value of ovarian mitochondrial signature 2.

| Gene Probe ID | Symbol | Hazard-Ratio | Log-Rank Test |

|---|---|---|---|

| 208909_at | UQCRFS1 | 3.68 | 9.8e-05 |

| 218563_at | NDUFA3 | 3.55 | 2.3e-05 |

| Combination | 5.03 | 1.2e-05 |

Figure 10. Ov-Mito-Signature 2 predicts patient outcome in ovarian cancer patients.

Note that high levels of Ov-Mito-Signature 2 (NDUFA3/UQCRFS1) effectively predicts overall survival (OS), progression-free survival (PFS) and post-progression survival (PPS). OS and PFS are shown in panel A. PPS is shown in panel B.

Figure 11. Ov-Mito-Signature 2 predicts the response to therapy in ovarian cancer patients.

Note that high levels of Ov-Mito-Signature 2 (NDUFA3/UQCRFS1) effectively predicts drug-resistance and treatment failure, illustrated here as overall survival. Results with Platin and Taxol therapy (Rx) are shown.

As such, both of these Ov-Mito-Signature(s) were a dramatic improvement over individual mitochondrial biomarkers, as well as CA125 and PCNA (Tables 1 & 3; Figure 2).

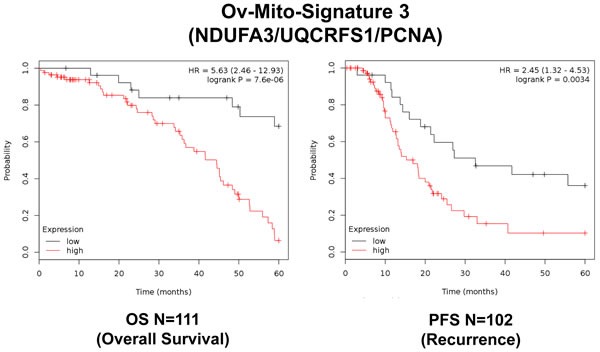

To further improve the predictive value of Ov-Mito-Signature-2, we next added the proliferative marker PCNA, to create Ov-Mito-Signature-3. The robust nature of Ov-Mito-Signature-3 is highlighted in Table 9 and Figures 12-14, which shows a hazard-ratio of 5.63 (p = 7.6e-06). Ov-Mito-Signature-3 was also the most effective in predicting the response to therapy (Figure 13). Importantly, Ov-Mito-Signature-3 retained its prognostic value in a larger group of serous ovarian cancer patients (N = 442), without restricting our analysis to patients with low serum CA125 levels (Figure 14).

Figure 12. Ov-Mito-Signature 3 predicts patient outcome in ovarian cancer patients.

Note that high levels of Ov-Mito-Signature 3 (NDUFA3/UQCRFS1/PCNA) effectively predicts overall survival (OS), and progression-free survival (PFS).

Figure 13. Ov-Mito-Signature 3 predicts the response to therapy in ovarian cancer patients.

Note that high levels of Ov-Mito-Signature 3 (NDUFA3/UQCRFS1/PCNA) effectively predicts drug-resistance and treatment failure, illustrated here as overall survival. Results with Platin and Taxol therapy (Rx) are shown.

DISCUSSION

Understanding CSCs, telomerase and mitochondrial activity: targeting ovarian cancer with doxycycline and/or palbociclib

The exact functional role of telomerase activity in ovarian cancer stem cell (CSC) propagation remains largely unknown. Recently, to address this issue, we indirectly monitored telomerase activity, by linking the hTERT-promoter to eGFP [6, 7]. Using SKOV3 ovarian cancer cells, stably-transfected with the hTERT-GFP reporter, we then used GFP-fluorescence to fractionate these cell lines into GFP-high and GFP-low populations. We functionally compared the phenotype of these GFP-high and GFP-low cell sub-populations. Importantly, we showed that ovarian cancer cells with higher telomerase activity (GFP-high) are energetically-activated, with increased mitochondrial OXPHOS and glycolysis [6]. This was confirmed by unbiased label-free proteomics analysis. A sub-population of SKOV3 cells with high telomerase activity showed i) increased “stemness” (3D-spheroid formation) and ii) enhanced cell migration (Boyden-chamber assay). These cellular phenotypes were halted by inhibitors of energy-metabolism, targeting either OXPHOS or glycolysis, or by using doxycycline, a clinically-approved antibiotic, that inhibits mitochondrial biogenesis [6, 7].

Telomerase activity also determined the ability of hTERT-high ovarian CSCs to proliferate, as determined by monitoring DNA-synthesis. Use of Palbociclib, a CDK4/6 inhibitor (an FDA-approved drug) specifically blocked ovarian CSC propagation, with an IC-50 of ∼100 nM [6]. Thus, telomerase-high ovarian CSCs are the most energetically-activated, migratory and proliferative cell sub-population [6]. These findings suggest a mechanistic interpretation for why long telomere length (a specific marker of high telomerase activity) is strictly correlated with metastasis disease progression and poor outcome in ovarian tumors and other cancer types [8, 9].

As such, elevated telomerase activity may “fuel” the propagation of ovarian CSCs

by activating mitochondrial biogenesis, ultimately leading to poor clinical outcome. These observations may help explain why combining mitochondrial markers, together with the proliferation marker PCNA, so significantly increased the prognostic value of this Ov-Mito-Signature.

Employing mitochondrial markers and mito-signatures, as companion diagnostics for treatment stratification: implications for drug re-purposing

In support of our current hypothesis, integrating telomerase activity with increased mitochondrial function, we demonstrate that a sub-set of mitochondrial gene transcripts are able to predict survival in serous ovarian cancer patients, with optimal de-bulking. As such, these particular mitochondrial markers could ultimately be used to select high-risk ovarian cancer patients at diagnosis, up to 5 years in advance, for close monitoring. As such, our results provide an excellent justification for the therapeutic targeting of mitochondria in ovarian cancer cells, to improve patient survival.

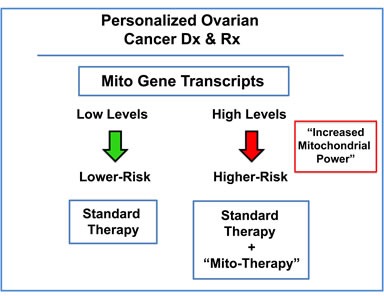

In this new paradigm, high-risk patients would be identified at diagnosis by the over-expression of mitochondrial mRNA transcripts in their ovarian tumors (Figure 15). As a consequence, these patients could then be treated with certain FDA-approved drugs (e.g., Doxycycline or Palbociclib; together with the standard of care), to improve overall survival. These therapeutics have been previously documented to halt the proliferation of the ovarian CSC population [6].

Figure 15. Ovarian cancer: mitochondrial-based companion diagnostics for personalized cancer therapy.

In this diagram, mitochondrial-based diagnostics would be used to separate ovarian cancer patients into higher-risk and lower-risk groups. Then, patients with high levels of mitochondrial markers in their primary tumor (“bad prognosis”) would be treated with mitochondrial-based therapies (such as “Doxycycline”), as an add-on to the standard of care, to prevent tumor progression and increase overall survival.

FDA-approved antibiotics can safely prevent mitochondrial biogenesis and/or OXPHOS as a manageable, off-target, “side-effect” [6, 7, 10–16]. These antibiotics include the tetracyclines, the erythromycins, as well as pyrvinium pamoate, atovaquone, and bedaquiline [10, 11, 13, 14]. For example, the new mitochondrial markers and Mito-Signatures we have discovered, could be used as companion diagnostics, for re-purposing these FDA-approved drugs as novel anti-cancer agents. More specifically, this would facilitate the ability of medical oncologists to identify the correct patient sub-population for new phase II clinical trials for drug re-purposing/re-positioning in serous ovarian patients, as an add on to conventional chemo-therapy (e.g., platins and taxol).

Mitochondrial markers and mito-signatures: implications for new drug discovery

The three new Mito-Signatures that we developed may also be useful for selecting new “druggable” targets for new drug development, to prevent treatment failure and improve overall survival. As a consequence of our K-M analyses, the mitochondrial ribosome would be an attractive new target for developing novel inhibitors of mitochondrial protein translation in cancer cells; similarly, mitochondrial chaperones, the OXPHOS complexes and the mitochondrial ATP-synthase may also be suitable drug targets. Multiple members of these multi-subunit protein complexes show significant prognostic value, suggesting that modulation of their intrinsic activity may provide therapeutic benefits. Targeting of these large complexes would be predicted to suppress tumor recurrence and prevent disease progression in these serous ovarian cancer patients.

In addition, such mitochondrial markers could also be employed as companion diagnostics for novel therapies targeting either mitochondria or telomerase (hTERT) and/or cell proliferation, to select the high-risk sub-population of ovarian cancer patients, resulting in the necessary treatment stratification. In direct support of this assertion, we showed here that three different Mito-Signature(s) could be used to successfully identify the sub-population of high-risk ovarian cancer patients that failed “platin” or “taxol” based therapies. These results indicate that mitochondrial markers could be used to monitor and/or predict the response to therapy, specifically identifying patients at high-risk for treatment failure at diagnosis, up to 5 years in advance, even before therapy is initiated.

METHOD OF ANALYSIS

Kaplan-Meier (K-M) Analyses. To perform K-M analysis on nuclear mitochondrial gene transcripts, we used an open-access online survival analysis tool to interrogate publically available microarray data from up to 1,435 ovarian cancer patients [5]. This allowed us to determine their overall prognostic value. For this purpose, we primarily analyzed 5-year follow-up data from serous ovarian cancer patients (stage III) that had optimal de-bulking (N = 111). Biased array data were excluded from the analysis. This allowed us to identify >100 nuclear mitochondrial gene probes, with significant prognostic value. Hazard-ratios for overall survival (OS), progression free survival (PFS; recurrence) and post-progression survival (PPS) were calculated, at the best auto-selected cut-off, and p-values were calculated using the logrank test and plotted in R [5]. K-M curves were also generated online using the K-M-plotter (as high-resolution TIFF files), using univariate analysis:

http://kmplot.com/analysis/index.php?p=service&cancer=ovar.

This allowed us to directly perform in silico validation of these mitochondrial biomarker candidates. The 2012 version of the database was originally utilized for all these analyses; however, virtually identical results were also obtained with the 2015 and 2017 versions.

Acknowledgments

It should be noted that this bioinformatics analysis, focused on nuclear-encoded mitochondrial gene transcripts, was not funded by a specific grant and did not require any research expenditures, since no “wet” laboratory experiments were performed.

Abbreviations

- CSCs

cancer stem-like cells

- HR

hazard ratio

- K-M

Kaplan-Meier

- MRPL

mitochondrial ribosomal proteins, large subunit

- MRPS

mitochondrial ribosomal proteins, small subunit

- N

number of patients in a given data set

- OS

overall survival

- OXPHOS

oxidative phosphorylation (mitochondrial respiration)

- PPS

post progression survival

- PFS

progression-free survival

Footnotes

Author contributions

Professor Lisanti and Dr. Sotgia conceived and initiated this project. Professor Lisanti and Dr. Sotgia both performed the bioinformatics analysis, and wrote the manuscript.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

MPL and FS hold a minority interest in Lunella, Inc.

REFERENCES

- 1.Worzfeld T, Pogge von Strandmann E, Huber M, Adhikary T, Wagner U, Reinartz S, Müller R. The Unique Molecular and Cellular Microenvironment of Ovarian Cancer. Front Oncol. 2017;7:24. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2017.00024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saglam O, Xiong Y, Marchion DC, Strosberg C, Wenham RM, Johnson JJ, Saeed-Vafa D, Cubitt C, Hakam A, Magliocco AM. ERBB4 Expression in Ovarian Serous Carcinoma Resistant to Platinum-Based Therapy. Cancer Control. 2017;24:89–95. doi: 10.1177/107327481702400115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Salomon-Perzyński A, Salomon-Perzyńska M, Michalski B, Skrzypulec-Plinta V. High-grade serous ovarian cancer: the clone wars. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2017;295:569–76. doi: 10.1007/s00404-017-4292-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haltia UM, Andersson N, Yadav B, Färkkilä A, Kulesskiy E, Kankainen M, Tang J, Bützow R, Riska A, Leminen A, Heikinheimo M, Kallioniemi O, Unkila-Kallio L, et al. Systematic drug sensitivity testing reveals synergistic growth inhibition by dasatinib or mTOR inhibitors with paclitaxel in ovarian granulosa cell tumor cells. Gynecol Oncol. 2017;144:621–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2016.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gyorffy B, Lánczky A, Szállási Z. Implementing an online tool for genome-wide validation of survival-associated biomarkers in ovarian-cancer using microarray data from 1287 patients. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2012;19:197–208. doi: 10.1530/ERC-11-0329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bonuccelli G, Peiris-Pages M, Ozsvari B, Martinez-Outschoorn UE, Sotgia F, Lisanti MP. Targeting cancer stem cell propagation with palbociclib, a CDK4/6 inhibitor: Telomerase drives tumor cell heterogeneity. Oncotarget. 2017;8:9868–84. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.14196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lamb R, Ozsvari B, Bonuccelli G, Smith DL, Pestell RG, Martinez-Outschoorn UE, Clarke RB, Sotgia F, Lisanti MP. Dissecting tumor metabolic heterogeneity: Telomerase and large cell size metabolically define a sub-population of stem-like, mitochondrial-rich, cancer cells. Oncotarget. 2015;6:21892–905. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.5260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Falandry C, Horard B, Bruyas A, Legouffe E, Cretin J, Meunier J, Alexandre J, Delecroix V, Fabbro M, Certain MN, Maraval-Gaget R, Pujade-Lauraine E, Gilson E, Freyer G. Telomere length is a prognostic biomarker in elderly advanced ovarian cancer patients: a multicenter GINECO study. Aging (Albany NY) 2015;7:1066–76. doi: 10.18632/aging.100840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kotsopoulos J, Prescott J, De Vivo I, Fan I, Mclaughlin J, Rosen B, Risch H, Sun P, Narod SA. Telomere length and mortality following a diagnosis of ovarian cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2014;23:2603–6. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-14-0885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lamb R, Ozsvari B, Lisanti CL, Tanowitz HB, Howell A, Martinez-Outschoorn UE, Sotgia F, Lisanti MP. Antibiotics that target mitochondria effectively eradicate cancer stem cells, across multiple tumor types: treating cancer like an infectious disease. Oncotarget. 2015;6:4569–84. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lamb R, Fiorillo M, Chadwick A, Ozsvari B, Reeves KJ, Smith DL, Clarke RB, Howell SJ, Cappello AR, Martinez-Outschoorn UE, Peiris-Pagès M, Sotgia F, Lisanti MP. Doxycycline down-regulates DNA-PK and radiosensitizes tumor initiating cells: Implications for more effective radiation therapy. Oncotarget. 2015;6:14005–25. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Luca A, Fiorillo M, Peiris-Pagès M, Ozsvari B, Smith DL, Sanchez-Alvarez R, Martinez-Outschoorn UE, Cappello AR, Pezzi V, Lisanti MP, Sotgia F. Mitochondrial biogenesis is required for the anchorage-independent survival and propagation of stem-like cancer cells. Oncotarget. 2015;6:14777–95. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fiorillo M, Lamb R, Tanowitz HB, Cappello AR, Martinez-Outschoorn UE, Sotgia F, Lisanti MP. Bedaquiline, an FDA-approved antibiotic, inhibits mitochondrial function and potently blocks the proliferative expansion of stem-like cancer cells (CSCs) Aging (Albany NY) 2016;8:1593–607. doi: 10.18632/aging.100983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fiorillo M, Lamb R, Tanowitz HB, Mutti L, Krstic-Demonacos M, Cappello AR, Martinez-Outschoorn UE, Sotgia F, Lisanti MP. Repurposing atovaquone: targeting mitochondrial complex III and OXPHOS to eradicate cancer stem cells. Oncotarget. 2016;7:34084–99. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.9122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Farnie G, Sotgia F, Lisanti MP. High mitochondrial mass identifies a sub-population of stem-like cancer cells that are chemo-resistant. Oncotarget. 2015;6:30472–86. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.5401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lamb R, Harrison H, Hulit J, Smith DL, Lisanti MP, Sotgia F. Mitochondria as new therapeutic targets for eradicating cancer stem cells: Quantitative proteomics and functional validation via MCT1/2 inhibition. Oncotarget. 2014;5:11029–37. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]