Abstract

Background

Non-cirrhotic portal hypertension (NCPH) is a common cause of variceal bleed in developing countries. Transient elastography (TE) using Fibroscan is a useful technique for evaluation of fibrosis in patients with liver disease. There is a paucity of studies evaluating TE in patients with Non-cirrhotic portal fibrosis (NCPF) and none in Asian population. Aim of this study was to evaluate role of TE in NCPF.

Methods

Retrospective data of consecutive patients of NCPF as per Asian pacific association for the study of liver (APASL) guidelines were noted. All patients had liver biopsy, TE, computed tomography of abdomen and hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG). Twenty age and gender matched healthy subjects and forty age matched patients with cirrhosis with Child's A were taken as controls.

Results

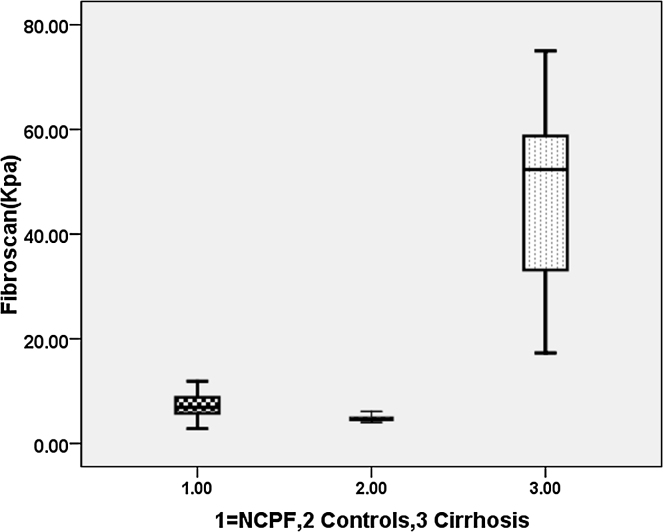

A total of 20 patients with age [median 29.5 (13–50) years], Male:Female = 11:9 with a diagnosis of NCPF were enrolled from January 2011 to December 2015. Of 20 patients 18 patients had variceal bleed and required endoscopic band ligation. There was no difference in haemoglobin and platelet count between patients with cirrhosis and NCPF, but total leucocyte count was significantly lower in patients with NCPF compared to patients with cirrhosis (3.2 vs 6.7 × 103/cumm, P = 0.01). TE (Fibroscan) was high in patients with NCPF compared to healthy controls (6.8 vs 4.7 kPa, P = 0.001) but it was significantly low compared to cirrhotic patients (6.8 vs 52.3 kPa, P = 0.001). HVPG is significant low in patients with NCPF compared to patients with cirrhosis (5.0 vs 16.0 mmHg, P = 0.001).

Conclusion

Transient elastography (Fibroscan) is significantly low in patients with NCPF compared to patients with cirrhosis. It is a very useful non-invasive technique to differentiate between Child's A cirrhosis and non-cirrhotic portal fibrosis.

Abbreviations: APASL, Asian pacific association for the study of liver; EVL, endoscopic variceal ligation; FHVP, free hepatic venous pressure; HVPG, hepatic venous pressure gradient; IPH, idiopathic portal hypertension; IQR, interquartile range; LS, liver stiffness; NCPF, non-cirrhotic portal fibrosis; PHT, portal hypertension; SR, success rate; TE, transient elastography; TM, time motion; WHVP, wedged (occluded) hepatic venous pressure

Keywords: NCPF, transient elastography, fibroscan

Non-cirrhotic Portal Fibrosis (NCPF) also called as Idiopathic portal hypertension (IPH), is a disorder of unknown aetiology. It is clinically characterised by features of portal hypertension (PHT); moderate to massive splenomegaly, with or without hypersplenism, preserved liver functions, and patent hepatic and portal veins on radiological imaging.1 The disease has been reported both from developing and developed countries.2, 3 According to the consensus statement of the Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver (APASL) on NCPF, the disease accounts for approximately 10–30% of all cases of variceal bleed in several parts of the world including India.4

Portal hypertension is defined by a portal-caval venous pressure gradient exceeding 5 mm Hg.1 Cirrhosis is the leading cause of PHT all over the world. However in many developing countries non-cirrhotic portal hypertension (NCPH) is seen in 10–30% of patients with PHT. The majority of NCPF patients present with signs or complications of portal hypertension.2, 3, 4 In Indian subcontinent two third of patients with NCPF presented with gastrointestinal haemorrhage, in contrast, a low prevalence of upper gastrointestinal bleeding as an initial manifestation has been reported in Japanese and Western patients, of which the majority presented with splenomegaly.5, 6

Prognosis of patient with variceal bleed differs in patient with NCPH compared to patients with cirrhosis. Radiological and biochemical tests are often done to evaluate of patients of variceal bleed.7, 8 However they are non-contributory in some patients and liver biopsy or hepatic venous pressure gradient is done to know fibrosis of liver and degree of portal hypertension. Due to invasive nature of these procedures, patient acceptability is limited. So to differentiate Child Pugh Class A and NCPF is often a problem in clinical practice.

Liver stiffness (LS) measurement by transient elastography (TE) is a very promising non-invasive method for the diagnosis of fibrosis in chronic liver diseases.9, 10, 11 A strong correlation between LS measurements and liver fibrosis stages, assessed by simultaneous liver biopsies, have been reported in chronic hepatitis B, C and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). There is no data on TE (Fibroscan) in patients with NCPF. The aim of this study was to evaluate the role of TE (Fibroscan) in differentiating patients with NCPF and Cirrhosis with Child Pugh class A (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Box Plot diagram showing Transient elastography in patients with cirrhosis, controls and non-cirrhotic portal fibrosis.

Materials and Methods

Patient Characteristics

This is a retrospective study of patients which included patients diagnosed with NCPF between January 2011 to December 2015. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of our Hospital. Consecutive patients of NCPF were included during this period. Patients were diagnosed as NCPF on basis of liver biopsy according to APASL recommendations.4 Patients were excluded if they had associated hepatitis B, C, history of alcohol intake, patients with jaundice and portal biliopathy and any shunt surgery in the past.

Twenty healthy subjects were taken as control. All these controls were asymptomatic and were screened to rule out underlying liver disease based on normal ultrasound abdomen, normal liver function tests and negative serology for hepatitis B and C. Similarly, for inclusion of cirrhotic patients, retrospective data (from January 2011 to December 2015) was analysed. All patients were age matched and belonged to Child Pugh class A. All were confirmed liver cirrhosis on basis of liver biopsy and had undergone a TE (fibroscan) and HVPG. Patients who had active alcohol consumption in last 6 months, had HCC or portal vein thrombosis were excluded from the study.

Liver Stiffness Measurement by Fibroscan and Hepatic Venous Pressure Gradient (HVPG)

TE was performed by hepatologist with 5 years of experience and who had performed more than 1500 fibroscans using the FibroScan apparatus (Echosens, Paris, France), which consists of a 5-MHz ultrasound transducer probe mounted on the axis of a vibrator. The tip of the transducer (M-probe) was covered with a drop of gel and placed perpendicularly in the intercostal space with the patient lying in dorsal decubitus position with the right arm in the maximal abduction. Under control one in time motion (TM) and A-mode, the operator chose a liver portion within the right liver lobe at least 6 cm thick, free of large vascular structures and gallbladder. The median value of 10 successful acquisitions, expressed in kilopascal (kPa), was kept as representative of the LS measurement. LS failure was recorded when no value was obtained after at least 10 shots. The results were considered unreliable in the following circumstances: valid shots fewer than 10, success rate (SR) less than 60%, or interquartile range (IQR)/LS greater than 30%.8

HVPG Measurement

HVPG was measured after an overnight fast and haemodynamic assessment were carried out using standard procedure. Briefly, under local anaesthesia and in supine position, a venous introducer was placed in the right femoral vein by the Seldinger technique. Under fluoroscopic guidance, a 7F balloon-tipped Swan Ganz catheter (Boston Scientific, Massachusetts, USA) was introduced in to the main right hepatic vein. Free hepatic venous pressure (FHVP) and wedged (occluded) hepatic venous pressure (WHVP) were measured using Nihon Kohden (Tokyo, Japan) haemodynamic monitor with pressure transducers. Measurements were made in triplicate, and the mean of three readings was taken in each case. If there was a difference of more than 1 mmHg between the readings, all the readings were repeated. Hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG) was obtained as the difference between WHVP and FHVP.12

Blood Tests, Imaging and Biochemical Examinations

Patient venous blood was taken and analysed for routine liver function tests and hematologic parameters by conventional methods and evaluation of viral markers like hepatitis B and hepatic C. All patients had ultrasound abdomen along with Doppler study for splenoportal axis and computed tomography (triple phase) for liver and spleen size. All patients had liver biopsy which was analysed by two pathologists who had vast experience in the field of liver histology. All patients had upper gastrointestinal endoscopy for evaluation of varices.

Statistical Analysis and Data Management

Data processing was performed by using the software packages SPSS. For a comparison of categorical variables, chi square and Fisher's exact tests were used, and for continuous variables, a Mann–Whitney test for unpaired data. Liver biopsy scoring was done by Ishak fibrosis score. The probability level of P < 0.05 was set for statistical significance.

Results

A total of 20 patients with a diagnosis of NCPF were enrolled from January 2011 to December 2015. Of 20 patients 18 patients had history of variceal bleed and required endoscopic band ligation. Large esophageal varices were seen in 16 (80%), gastric varices in 6(30%) and rest had small esophageal varices (20%) at the time of first presentation to hospital. There were 40 cirrhotics in this study. The aetiology of cirrhosis was Alcohol in 16 (40%), NASH (Non-Alcoholic Steatohepatitis) in 11 (27.5%), Hepatitis B infection in 8 (20%), and Hepatitis C infection in 5 (12.5%) patients. Among these patients 30 had variceal bleed and 10 had no variceal bleed. Baseline characteristics of patients are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinical and Biochemical Profile of Patients.

| Parameters Median (range) |

NCPF Patients (n = 20) |

Controls (n = 20) |

P (NCPF vs Controls) | Cirrhosis (n = 40) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yrs) | 29.5 (13–49) | 32 (13–49) | 0.81 | 32 (15–49) |

| M:F | 11:9 | 10:10 | 0.7 | 29:11 |

| Haemoglobin (g%) | 9.15 (3.8–13.7) | 13.5 (12–16) | 0.01 | 9.9 (7–15.9) |

| Total leucocyte count (mm3/dl) | 3.25 (1.7–10.5) | 7.45 (3.4–11.0) | 0.001 | 6.1 (1.6–16.7) |

| Platelets (103 ml–1) | 94 (23–134) | 210 (138–400) | 0.001 | 102 (33–199) |

| Total bilirubin (mg%) | 1.3 (0.8–4.1) | 0.8 (0.4–1.3) | 0.004 | 2.0 (0.5–2.8) |

| AST (IU/l) | 40 (18–121) | 31 (23–40) | 0.006 | 46 (17–221) |

| ALT (IU/l) | 32 (12–134) | 30 (23–40) | 0.006 | 55 (23–184) |

| Serum albumin (gm/dl) | 3.4 (2.9–4.0) | 3.9 (3.8–4.3) | 0.001 | 3.1 (2.9–4.2) |

| INR | 1.3 (1.0–1.8) | 1.0 (0.8–1.1) | 0.32 | 1.79 (1.0–2.1) |

| Variceal size none:small (≤5 mm):large(>5 mm) |

0:4:16 | – | – | 0:10:30 |

AST/ALT: Aspartate transaminases and alanine transaminases; INR: International normalised ratio.

Imaging in Patients with NCPF

All patients had ultrasound of abdomen along with Doppler to see for patency of portal vein and hepatic veins. Triple phase Computed Scan of abdomen was also done to confirm the findings of ultrasound.

All patients with cirrhosis had radiological features of cirrhosis with no portal vein thrombosis or HCC in any of the patient enrolled. Impression by radiologist matches with liver biopsy findings of cirrhosis in all patients. However in patients with NCPF features of portal hypertension were present as reflected by large Splenomegaly, dilated portal vein and collaterals. However of 20 patients 18 patients were labelled as having cirrhosis by radiologist based on altered liver contour, Splenomegaly and dilated portal vein.

Liver Biopsy

The diagnosis of NCPF was made on the basis of liver biopsy findings. Transjugular liver biopsy was done in 8 patients while percutaneous was done in 12 patients after platelet transfusion in these patients. 16 (80%) patients showed intralobular fibrous septa and mild portal fibrosis. Portal inflammations was seen in 10 (50%) of patients. Few abnormal vessels in parenchyma was seen in 6 (30%). Patchy and segmental subendothelial thickening was present in 8 (40%) of these patients. Cirrhosis was confirmed histologically in all patients of cirrhosis and showed nodule formation in all patients.

NCPF Patient Comparison with Healthy Controls and Cirrhosis

Of 20 patients 18 (90%) patients were bleeders and were on endoscopic variceal ligation (EVL) protocol. None of the patients were on non-selective beta blocker. There was significant difference in haemoglobin, total leucocyte count and platelets between NCPF patients and healthy controls. However there was no difference in haemoglobin and platelet count between patients with cirrhosis and NCPF, but total leucocyte count was significantly lower in patients with NCPF compared to patients with cirrhosis (3.2 vs 6.7 × 103/cumm, P = 0.01).

Hepatic Venous Pressure Gradient and Transient Elastography

All patients with NCPF and cirrhosis underwent HVPG. None of the patients with NCPF or cirrhosis were on beta blocker prior to HVPG prior to HVPG. We found significant difference in HVPG between patients with cirrhosis and NCPF (Table 2). Transient elastography using Fibroscan was done within week time of HVPG in all patients. Fibroscan was high in patients with NCPF compared to healthy controls but it was significantly lower compared to cirrhotic patients (Table 2).

Table 2.

Hepatic Venous Pressure Gradient and Transient Elastography in Patients with Non-cirrhotic Portal Fibrosis, Cirrhosis and Controls.

| NCPF | Controls | Cirrhosis | P (NCPF vs C) | P (NCPF vs cirrhosis) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HVPG (mmHg) | 5 (2–10) | – | 16 (11–22.5) | – | 0.001 |

| Transient Elastography (Fibroscan) (kPa) | 6.8 (2.8–11.9) | 4.7 (4–5.9) | 52 (17.3–75) | 0.005 | 0.001 |

HVPG: hepatic venous pressure gradient.

Discussion

NCPF has been reported from all over the world; however, the condition is more common in the developing than in the developed countries.2, 3, 5 The patients are normally young and may present with one or more well-tolerated episodes of gastrointestinal haemorrhage, long-standing mass in the left upper quadrant (splenomegaly) and consequences of hypersplenism. Development of ascites, jaundice and hepatic encephalopathy is not common and may rarely be seen after an episode of variceal bleed.1 Diagnosis needs demonstration of portal hypertension with patent portal vein and liver biopsy which reveals no cirrhosis.4 As most of these patients had low platelet count doing a percutaneous liver biopsy is not easy in day to day clinical practice.

We noticed that the median age of these patients was 29.5 (13–50) years and slightly male predominance. This is in accordance to previous published studies.2, 3 Features of hypersplenism were present in 14(70%) of these patients.

Median hepatic venous pressure gradient in patients with NCPF was 5.02, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 mmHg which was significantly lower than the patients with cirrhosis which confirmed the presinusoidal nature of portal hypertension in these patients. Our previous published study in patients with NCPF (N = 20) had shown similar results in which we found the hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG) was significantly lower than in the cirrhotic patients (4.9 ± 1.5 mmHg vs. 15.7 ± 4.5 mmHg; P < 0.01). NCPF patients had hyperdynamic circulation and peripheral vasodilatation comparable to cirrhotic patients.12 However HVPG is an invasive procedure to differentiate non-cirrhotic portal hypertension and portal hypertension due to cirrhosis and is not widely done in many centres of the world.

Non-invasive imaging like ultrasound of abdomen and computed tomography is usually done for the evaluation of portal hypertension. Doppler USG is the first line radiological investigation in patients with NCPF which normally shows liver is normal in size and echotexture. Spleen is enlarged with presence of gamma-gandy bodies; splenoportal axis is dilated and patent in NCPF. PV is thickened (>3 mm) with echogenic walls and its intrahepatic radicles are smooth and regular.3 However in our patients 18 of 20 were labelled as cirrhosis and portal hypertension based on ultrasound and Doppler study. As cirrhosis of liver is far more common than NCPF, we attribute this reason for the radiologist to label all our patients as cirrhosis rather than NCPF. This is common in all centres so getting a ultrasound with Doppler probably will not help the clinicians in their day to day practice to differentiate cirrhosis and NCPF.

Liver stiffness (LS) measurement by transient elastography (TE) is a very promising non-invasive method for the diagnosis of fibrosis in chronic liver diseases.10, 11 However role of LS in patients with non-cirrhotic portal hypertension has not been well studied. We had shown earlier that LS in patients with Liver(6.7 ± 2.3 kPa) and spleen(51.7 ± 21.5 kPa) stiffness in patients with extrahepatic portal vein obstruction(EHPVO) is significantly higher than liver(4.6 ± 0.7 kPa) and spleen(16.0 ± 3.0 kPa) stiffness in healthy controls. However it was significantly lower than patient with cirrhosis who had varices.13 There is no study to evaluate the role of LS in patients with NCPF. In this study we found LS in patients with NCPF (6.6 ± 2.7 kPa) which is significantly lower than compared to age matched patients with cirrhosis (48.7 ± 17.8 kPa). Similar results were observed Seijo et al. in a study in western population.14 Mean liver stiffness in idiopathic portal hypertension was 8.4 ± 3.3 kPa; and in cirrhosis it was 40.9 ± 20.5 kPa (P = 0.005).

Hence, TE is an easy non-invasive way to differentiate whether portal hypertension is due to cirrhosis or non-cirrhosis.

This is the first study in Asian population which has evaluated role of TE in patients with NCPF. HVPG and liver biopsy was done to substantiate our diagnosis of NCPF. In conclusion TE using Fibroscan is an easy technique to differentiate patients with cirrhosis and NCPF and we advised all patients of PHT to have TE at baseline to identify subgroup of patients with non-cirrhotic portal hypertension who has better prognosis.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have none to declare.

References

- 1.Sarin S.K., Kumar A. Noncirrhotic portal hypertension. Clin Liver Dis. 2006;10:627–651. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2006.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Madhu K., Avinash B., Ramakrishna B. Idiopathic non-cirrhotic intrahepatic portal hypertension: common cause of cryptogenic intrahepatic portal hypertension in a Southern Indian tertiary hospital. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2009;28:83–87. doi: 10.1007/s12664-009-0030-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dhiman R.K., Chawla Y., Vasishta R.K. Non-cirrhotic portal fibrosis (idiopathic portal hypertension): experience with 151 patients and a review of the literature. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;17:6–16. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2002.02596.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sarin S.K., Kumar A., Chawla Y.K. Noncirrhotic portal fibrosis/idiopathic portal hypertension: APASL recommendations for diagnosis and treatment. Hepatol Int. 2007;1:398–413. doi: 10.1007/s12072-007-9010-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hillaire S., Bonte E., Denninger M.H. Idiopathic non-cirrhotic intrahepatic portal hypertension in the West: a re-evaluation in 28 patients. Gut. 2002;51:275–280. doi: 10.1136/gut.51.2.275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schouten J.N.L., García-Pagán J.C., Valla D.C. Idiopathic noncirrhotic portal hypertension. Hepatology. 2011;54:1071–1081. doi: 10.1002/hep.24422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Siramolpiwat S., Seijo S., Miquel R. Idiopathic portal hypertension: natural history and long-term outcome. Hepatology. 2014;59:2276–2285. doi: 10.1002/hep.26904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Qureshi H., Kamal S., Khan R.A. Differentiation of cirrhotic vs idiopathic portal hypertension using 99mTc-Sn colloid dynamic and static scintigraphy. J Pak Med Assoc. 1991;41:126–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Foucher J., Chanteloup E., Vergniol J. Diagnosis of cirrhosis by transient elastography (FibroScan): a prospective study. Gut. 2006;55(3):403–408. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.069153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Friedrich-Rust M., Ong M.F., Martens S. Performance of transient elastography for the staging of liver fibrosis: a metaanalysis. Gastroenterology. 2008;134(4):960–974. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fraquelli M., Rigamonti C., Casazza G. Reproducibility of transient elastography in the evaluation of liver fibrosis in patients with chronic liver disease. Gut. 2007;56:968–973. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.111302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sharma P., Kumar A., Mehta V. Systemic and pulmonary hemodynamics in patients with non-cirrhotic portal fibrosis (NCPF) is similar to compensated cirrhosis. Hepatol Int. 2007;1(1):275–280. doi: 10.1007/s12072-007-5006-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sharma P., Mishra S.R., Kumar M. Liver and spleen stiffness in patients with extrahepatic portal vein obstruction. Radiology. 2012;263(3):893–899. doi: 10.1148/radiol.12111046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seijo Susana, Reverter Enric, Miquel Rosa. Role of hepatic vein catheterisation and transient elastography in the diagnosis of idiopathic portal hypertension. Digestive and Liver Disease. 2012;44:855–860. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2012.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]