Abstract

Background

Acute-on chronic liver failure (ACLF) is defined as acute insult on previous liver disease that causes sudden worsening of liver functions.

Methods

ACLF is characterized by high incidence of organ failure and prognosis is remarkably worse than patients with cirrhosis. Incidence of organ failures is very high despite best medical care and timely liver transplant before development of multi organ failure is associated with good survival rates.

Results

At present, there are no reliable score or ways to correctly identify patients who are going to recover from patients who will need transplantation. Organ failures are important part of prognosis and to define need or futility of early liver transplantation.

Conclusion

Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver (APASL) published their recommendations regarding ACLF in 2014. Several important studies regarding course/nature of disease and transplantation for ACLF became available after 2014 APASL recommendations and still there are some unanswered areas. The current review discusses various issues regarding liver transplantation in patients with ACLF.

Abbreviations: ACLF, acute-on chronic liver failure; APASL, Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver; DDLT, deceased donor liver transplantation; EASL, European Association for the Study of the Liver; MELD, model for end stage liver disease; LDLT, living donor liver transplantation; LT, liver transplantation; OFs, organ failures; SIRS, systemic inflammatory response syndrome

Keywords: acute-on chronic liver failure, liver transplantation, living donor liver transplantation, survival, India

The syndrome of acute-on chronic liver failure (ACLF) is different from decompensated cirrhosis as it is precipitated by some acute event that leads to rapid deterioration. ACLF is characterized by hepatic/extrahepatic organ failures (OFs) and is associated with high short-term mortality.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 As name suggests there is a component of reversibility and these patients may recover to state before onset of ACLF; the prognosis is poor in absence of improvement. ACLF patients have a significant risk of development of OFs and mortality in absence of improvement and liver transplantation (LT) should be considered in such patients before development of multi-OF.7, 8, 9 Thus, these patients have a small window of opportunity (LT) before development of OFs and it is important to identify prognosis of ACLF before it is too late.10

Various Definitions of ACLF

Multiple definitions have been used in literature for ACLF.11 The first systemic attempt to define ACLF was published by Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver (APASL) in 2009 based on expert consensus. The ACLF was defined as ‘acute hepatic insult manifesting as jaundice (bilirubin >5 mg/dl), and coagulopathy (INR > 1.5) complicated within 4 weeks by ascites and or encephalopathy in a patient with previously diagnosed or undiagnosed chronic liver disease’. The cut-offs of bilirubin and INR were arbitrary.12 APASL revised this definition based on database collected from APASL ACLF Research Consortium. The revised definition included ‘occurrence of high short-term mortality at 28 days’.2 The definition given by European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) was based on prospective database from EASL-CLIF Acute-on-Chronic Liver Failure in Cirrhosis (CANONIC) study. It was based on the presence of the 3 important characteristics of ACLF syndrome: acute decompensation (inclusion criterion), OF defined by the SOFA-CLIF score (modified SOFA score) and high 28-day mortality rate.4 The EASL definition is applicable to patients with cirrhosis only as compared to APASL definition which also include noncirrhotic liver disease as underlying chronic liver disease. EASL definition include extrahepatic OFs also which APASL definition does not include.1 The World Gastroenterology Organisation also proposed a definition for ACLF including non-cirrhotic chronic liver disease as underlying chronic liver disease while the rest was kept as similar to EASL definition.5

Course and Prognosis in Patients With ACLF

It is important to look at course of ACLF as LT should not be done in patients who will recover with medical treatment and early LT should be considered in patients with worsening or no improvement to before development of multi-OF. The course of ACLF (improvement or worsening) may be very rapid. Gustot et al. showed that grade of ACLF changed very rapidly (defined as within 48 h) in 40% of patients, it changed rapidly (defined as 3–7 days) in approximately 14.7% of patients and changed slowly (defined as change of ACLF grade in 8–28 days) in 14.7% of patients. The grade of ACLF at day 3–7 was better to predict prognosis than grade of ACLF at admission.7 The final grade of ACLF remained same as ACLF grade at day 3–7 in 81% of patients. As course of ACLF patients may change rapidly, it is important to identify need of LT before patients develop multi-OF and do not remain candidates for transplant.7 The authors found CLIF-C ACLF and liver failure as independent prognostic markers of early severe copurse.7 ACLF resolved or improved in 49.5% patients, it remained steady or fluctuating in 30.4% and worsened in 20.1% (CANONIC database). The resolution rates were 54.5%, 34.6% and 16% for ACLF grade 1, 2 and 3 respectively. The ACLF worsened in 21.2% of ACLF-1, 25.7% of ACLF 2 and it remained steady/fluctuating in 68% of ACLF-3.7 OFs are an important part of prognosis in patients with ACLF and prognosis worsens in patients with higher number of OFs (with higher ACLF grades). As discussed earlier, ACLF definition from EASL also include extrahepatic OFs and EASL CLIF score have been shown to be better than APASL ACLF definition.13 The SOFA score consists of 6 variables (Table 1), each OF have various categories and a higher score is given for worse organ function. The SOFA score was modified and definition of OF are proposed as shown in Table 1 (shown in bold letters). The patients of ACLF are divided as no ACLF (no OF or single non-kidney OF with creatinine <1.5 mg/dl), grade 1 ACLF (single kidney failure or 1 OF with serum creatinine 1.5 to 1.9), grade 2 ACLF (2 OFs) and grade 3 ACLF (3 or more OFs) as per EASL definition.4 While no ACLF had mortality of 1.9% and 10% at 28 days and 90 days, these mortality rates are 23% and 41% for ACLF grade 1, 31% and 55% for ACLF grade 2 and 74% and 78% for ACLF grade 3 respectively. Overall ACLF (total) had a mortality of 33% at 28 days and 51% at 90 days.4 This CLIF-OF score was further modified to CLIF-C ACLF score by creating 3 subcategories (Table 1) of OF severity and including age and white blood cell count. The CLIF-C ACLF score can be calculated online. The CLIF-C ACLF score was better to predict mortality than other scores in CANONIC database.3 Bajaj et al. analyzed data of 507 patients with inclusion of infection as acute event and overall mortality was 23%. The mortality was >50% in presence of ≥2 OFs.6 Some of the Indian studies evaluating mortality of patients with ACLF are shown in Table 2.8, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21 These studies show a mortality rate ranging from 41.4% (median of 8 days) to 74.5% at 90 days.18, 19 It has also been shown that mortality at 28 days and 90 days remains almost similar in presence of hepatic or non-hepatic acute event.19

Table 1.

Organ Failures and CLIF-C ACLF Subscores.3

| Organ/system | Subscore 1 | Subscore 2 | Subscore 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Liver (bilirubin, mg/dl) | <6 | ≥6 | ≥12 |

| Kidney (creatinine, mg/dl) | <2 | ≥2 to <3.5 | ≥3.5 |

| Brain (West-Haven grade for hepatic encephalopathy) | 0 | Grade 1 or 2 | Grade 3 or 4 |

| Coagulation (INR) | <2.0 | ≥2.0 and <2.5 | INR ≥ 2.5 |

| Circulation (mean arterial pressure) | ≥70 mm/Hg | ≤70 mm/Hg | Vasopressors |

| Respiratory (PaO2/FiO2) Or SpO2/FiO2 |

>300 >357 |

≤300 and >200 >214 and ≤357 |

<200 ≤214 |

Organ failure's cut-off is shown as bold characters.

Table 2.

Indian Studies on Mortality in Patients With ACLF.

| Author (yr) | n | Mortality | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Duseja (2010)14 | 102 | 46% in hospital/1st month | Infections included as acute event |

| Duseja (2013)8 | 100 | 53% in hospital/1st month | APACHE better than other scores |

| Garg (2012)15 | 91 | 63% at 3 months | Alcoholic and hepatitis B population |

| Amarapurkar (2015)16 | 62 | >60% | If both EASL/APASL criteria present in patients |

| Shalimar (2016)9 | 213 | 43.4% in hospital mortality | HEV-ACLF has lower mortality, alcohol worse |

| Pati (2016)17 | 123 | 71.2% at 90 days | Alcoholics had worse outcomes |

| Shalimar (2016)18 (INASL consortium) | 1049 | 41.6%, median 8 days | Creatinine, encephalopathy, requirement of ventilator support were independent predictors |

| Gupta (2017)19 | 122 | 53% (hepatic) vs. 56% at 28 days 85% (hepatic) vs. 74.5% at 90 days |

Hepatic versus extrahepatic acute insults: similar mortality |

| Choudhary (2017)20 | 561 | 61.6% at 90 days | Without SIRS at presentation 42.8%, with SIRS—65% |

| Agrawal (2015)21 | 106 | 48% in hospital | OF count better than CANONIC grading to predict mortality |

HEV: hepatitis E related; OF: organ failure; SIRS: systemic inflammatory response syndrome.

ACLF is very heterogeneous condition with different combinations of acute and chronic events. Acute event ranges acute viral hepatitic illness to non-hepatototropic infections, alcohol, drug induced liver injury, surgery, reactivation/flare up of basic disease (hepatitis B, Wilson's disease, autoimmune hepatitis).2, 4, 14 Alcohol as acute event has been shown to be associated with worse outcomes.9, 17 Shalimar et al. analyzed data of 213 patients of ACLF prospectively from Delhi, India. Acute event was continuous alcohol consumption in 77 (33.3%) and acute hepatitis E in 39 patients. The mortality rates were higher for alcohol with hazard ratios of 4.08. The etiology was independent predictor of mortality. The mortality was 54% in alcoholic group versus 12.8% in hepatitis E group.9 Pati et al. also showed more mortality in alcohol group (81.1%) versus nonalcoholics (55.8%).17 Shalimar et al. showed that mortality was higher in patients with silent chronic liver disease (33.9%) as compared to patients with overt chronic liver disease (53.5%).9 One study from Dr. Sarin's group (Delhi, India) showed that absence of systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) in patients with ACLF was associated with good prognosis.20 New onset SIRS and sepsis developed in 75% and 8% at a median 7 days. The mortality was 42.8% in no SIRS group as compared to 65% in SIRS group.20

LT for ACLF

As course of ACLF changes rapidly and higher ACLF grades do not improve in majority and are associated with high short term mortality, it is important to identify patients for LT before development of multi-OF. The recommendations for LT were given by APASL in 2014; the guidelines state that there are no validated criteria and scoring systems for identification for early LT and model-for end stage liver disease (MELD score) need further evaluation. ACLF patient with MELD ≥ 30 should be considered for urgent transplantation; LT should not be considered in presence cardiac/pulmonary OF or in cases with rapidly progressive OF at day 4 to day 7. There were slightly different criteria proposed for patients with hepatitis B reactivation.2 Table 3 shows outcome of LT for ACLF.7, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33 The majority of studies have shown good outcomes and comparable survival rates in patients transplanted for non-ACLF, however, most of these studies have not included patients with higher ACLF grades (multi-OF). Patients with severe ACLF have been shown to have lower survival rates in some of these studies30, 32 as compared to patients transplanted for non-ACLF, however, even this survival rate is much better than survival of patients without transplantation. Gustot et al. showed a survival rate of 80.9% at 6 months in patients with ACLF 2–3 as compared to 10% in similar grades of ACLF patients who could not undergo LT. The data from our centre33 published as abstract in international liver transplant society meet 2017 shows survival rate of 80% in transplant recipients as compared to 32% in patients without transplant at 6 months. Moon et al. showed survival of 80% in patients with grade 3 ACLF as compared to 7.9% in controls.31 The wait list mortality is also quite high in patients with ACLF.29

Table 3.

Outcomes of Liver Transplantation for ACLF.

| Study | n | Survival | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Liu et al. (2003)22 | 32 | 88% at 1 year | Hepatitis B patients |

| Wang et al. (2007)23 | 42 | 83.3% at 1 year | Both DDLT and LDLT were done |

| Chan et al. (2009)24 | 149 | 95.3% at 1 year 90% at 5 years |

Both DDLT and LDLT were done |

| Bahirwani et al. (2011)25 | 157 | 74.5% at 1 year | 175 patients had no ACLF, post transplant outcomes similar including eGFR |

| Ling et al. (2012)26 | 126 | 73% at 1 year | Downgrading MELD improved survival, both DDLT and LDLT |

| Duan et al. (2013)27 | 100 | 80% at 1 year 74% at 5 years |

Both DDLT and LDLT |

| Xing et al. (2013)28 | 133 | 78.1% at 1 year 72.8% at 5 years |

Hepatorenal syndrome improved with LT, good outcome of combined liver kidney transplantation for patients with ESRD |

| Finkenstedt et al. (2013)29 | 33 | 84.8% at 1 year 82% at 5 years |

High wait list mortality in ACLF group, survival after LT comparable to non-ACLF |

| Gustot et al. (2014)7 | 35 | 80.9% at 6 months | 10% in those not transplanted for ACLF2–3 |

| Levesque et al. (2017)32 | 140 | 70% 1 year as compared to 92% in without ACLF | ACLF-3 poor than lower grades, 17/30 (56%) mortality at 1 yr in ACLF 3 |

| Artru et al. (2017)30 | 73 | 83.9% at 1 year, baseline ACLF grade 3 | 7.9% survival in not LT, all patients had complications and longer hospital stay |

| Moon et al. (2017)31 | 189 ACLF 136 (non-ACLF) |

76.8% at 1 year 70.5% at 5 years |

ACLF longer stay in ICU as compared to without ACLF, survival worse than patients without ACLF (89.8% and 81.0%, respectively at 1 and 5 years) |

| Yadav et al. (2017)33 | 52 | 88.5% at 90 days | Non-LT (n = 68) had 32.4% survival at 6 months |

Some studies have not reported 5 year survival; DDLT: deceased donor liver transplantation; LDLT: living donor liver transplantation; eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate; LT: liver transplantation.

LT for Sick Patients or ACLF Grade 3

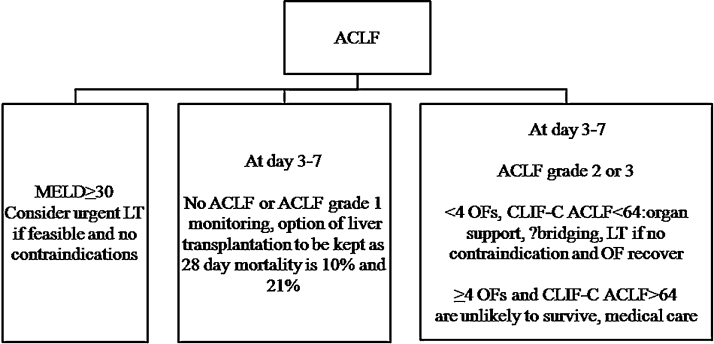

It should be noted that results of LT for very sick patient are not as good as for non-ACLF patients. Both deceased donor liver transplantation (DDLT) and living donor liver transplantation (LDLT) have been used for patients with ACLF. Moon et al. analyzed outcomes of 327 (including 189 ACLF) LDLTs for high MELD scores (≥30). The 5 year survival patient and graft survival in high MELD group was 76.4% and 75.2% which was significantly worse than in patients with lower and intermediate MELD scores. The lower survival was mainly attributed to presence of ACLF. The 5 year graft survival was 70.55 in ACLF group as compared to 81% in no ACFL group, P = 0.035. The ACLF group also had longer hospital stay.30 LT needs careful patient selection in very sick patients. There is lack of data regarding LT in patients with ACLF and multi-OF. Older studies done in cirrhosis patients showed inferior survival after LT in presence of OF. Knnak et al. showed 19% mortality at 1 year when patients were intubated and were on low doses of ionotropes.34 Petrowsky et al. showed 22% mortality in patients with MELD > 40 in a series of 169 LTs.35 The authors showed almost 50% mortality at 3 months if all of following 4 were present; high MELD, shock, cardiac risk and Charlson Comorbidity Index.35 Umgelter et al. analyzed data of 23 patients with increasing MELD and SOFA score. Eight of these patients had 3 or 4 OFs, 10 were on renal replacement therapy and all were on ventilator and on ionotropes. The mortality was 39% at 3 months and 54% at 1 year.36 Data on LT in patients with multi-OF is limited. Duan et al. showed 27% mortality after LT in presence of high MELD (median 32) and at least one OF.27 Recently 2 studies analyzed results of LT for ACLF grade 3 and have shown contradicting results.30, 31 Artru et al. included 73 patients with grade 3 ACLF. These patients had mean MELD of 40, CLIF-C ACLF 63.5. LT was done at median of 9 days after admission, OF improved from 4.03 to 3.67, P = 0.009 before LT. The patients had stabilization or improvement of hemodynamic status (not on high noradrenalin) and respiratory parameters (not in severe ARDS) in absence of uncontrolled sepsis. This short period of improvement/stabilization worked as “transplantation window”. One-year survival of was 83.9% in this cohort. This survival was not different from matched patients with no ACLF (90%) or from ACLF1 (82.3%) or ACLF2 (86.2%). The authors noted complications in 100% of patients with ACLF 3 and hospital stay was longer in this group. A total of 15.8% patients had respiratory OF at LT also (43% at admission).31 The other study of LT for ACLF 3 showed lower survival (17/30, 56.7% mortality) in ACLF 3 as compared to no ACLF or ACLF grade 1 and 2.30 Seventy-six percent patients had respiratory failure and 60% had cardiac failure in ACLF 3 group. The difference of mortality after LT in these 2 studies is likely secondary to higher incidence of respiratory failure in study by Levesque et al. and improving trend of patients in study by Artru et al.30, 31 The proposed follow up chart of patients with ACLF (based on references 7, 10, 37, 38, 39) is shown as Figure 1. Table 4 summarizes unresolved issues and current knowledge regarding LT for patients with ACLF.

Figure 1.

The proposed algorithm for patients with ACLF.

Table 4.

Unresolved Issues in LT for ACLF.

| Issues | What do we know | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Selection criteria for LT | Urgent transplantation is suggested if MELD ≥ 30 ACLF grade 2–3 at day 3–7 in absence of contraindications for LT should be taken to LT |

MELD < 30, ACLF-C < 30, showing improvement in first week-monitor No ACLF or ACLF grade 1 at day 3–7 (10% and 21% mortality at 28 days, and 38% and 47% mortality at 180 days, keep option of LT on) ≥4 OFs and CLIF-C ACLF > 64 are unlikely to survive, medical care |

| How long to wait for spontaneous improvement | If no improvement and OF at first week then LT should be considered | Development of SIRS is a poor prognostic sign |

| How to prioritize these patients for LT as | Scores including multiple OFs are better to predict prognosis | MELD is used for organ allocation, not good for prognosis in ACLF |

| How to access prognosis very early in course | No good model | Trend of OFs is important |

| Role of bridge in presence of organ failure | May help | Cost and availability |

| When not to consider for LT | No defined delisting criteria | Multiple OFs (worsening trend), pulmonary failure, high ionotropes, active infection |

MELD: model-for end stage liver disease; OF: organ failure; SIRS: systemic inflammatory response syndrome.

When Not to Transplant

Patients showing improvement in first week or patient who were previously well or with hepatitis E as acute event are more likely to improve and monitoring can be done.7, 9 Patients with ongoing sepsis or multi-OF (particularly worsening trend) should not be considered for transplantation. More caution is needed in patients with respiratory failure in absence of large data and current high mortality. There are no universal delisting criteria and it is based on individual choice. The patients who improve initially may worsen later in course and have risk of mortality, thus these patients should be kept under monitoring as they may need LT.7

Place of Bridging Therapy

Artificial liver support systems may help in bridging sick patients with ACLF to LT by removing toxins and supporting liver functions. Improvement of biochemical parameters and hemodynamic parameters has been reported.40, 41 However, 2 large randomized controlled studies (RELEIF and HELIOS) failed to show any survival benefit in patients with ACLF. The RELIEF trial compared Molecular Adsorbent Recirculating System (MARS, n = 95) to standard therapy (SMT) (n = 94). The MARS group had better creatinine, bilirubin and improvement of hepatic encephalopathy, however, mortality was similar at 28 days.42 The HELIOS trial compared fractionated plasma separation and adsorption (FPSA by Prometheus liver support system, n = 77) to SMT (n = 68). There was no difference of survival at 28 days, subgroup analysis showed survival benefit in MELD > 30.43 Recently a study compared results of molecular adsorbent recirculating system (n = 47) with standard medical treatment (n = 54) in patients with ACLF. The authors demonstrated decreased 14-day mortality rate in the molecular adsorbent recirculating system group (9.5% versus 50.0%) in with standard medical treatment, especially in patients with ACLF 2–3.44 A meta-analysis of 371 patients with ACLF has also shown benefit of artificial liver support systems in ACLF.45 Ling et al. showed that improving MELD improves survival in responder group after LT.26 The bridging therapy may help ACLF patients to reach LT, however, more data is needed.

Conclusions

To summarize LT should be offered in early course of ACLF before onset of sepsis and multi-OF. Patients with ACLF have high short-term mortality and transplant free survival is very poor in grade 3 ACLF patients. LT has been shown to be safe and effective with good outcome in patients with ACLF, more data is needed in patients with grade 3 ACLF and outcomes are relatively inferior in patients with multi-OF. As ACLF is a heterogeneous condition and has a dynamic course, so decision for LT should be individualized. Decision for transplantation should be taken early and first week is probably the best time to decide.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have none to declare.

Acknowledgement

Mr. Yogesh Saini (research coordinator).

References

- 1.Duseja A., Singh S.P. Toward a better definition of acute-on-chronic liver failure. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2017;7:262–265. doi: 10.1016/j.jceh.2017.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sarin S.K., Kedarisetty C.K., Abbas Z. Acute-on-chronic liver failure: consensus recommendations of the Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver (APASL) 2014. Hepatol Int. 2014;8:453–471. doi: 10.1007/s12072-014-9580-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jalan R., Saliba F., Pavesi M. Development and validation of a prognostic score to predict mortality in patients with acute-on-chronic liver failure. J Hepatol. 2014;61:1038–1047. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moreau R., Jalan R., Gines P. Acute-on-chronic liver failure is a distinct syndrome that develops in patients with acute decompensation of cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:1426–1437. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.02.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jalan R., Yurdaydin C., Bajaj J.S., World Gastroenterology Organization Working Party Toward an improved definition of acute-on-chronic liver failure. Gastroenterology. 2014;147:4–10. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bajaj J., O’Leary J., Reddy K. Survival in sepsis-related acute-on-chronic liver failure is defined by extrahepatic organ failures. Hepatology. 2014;60:250–256. doi: 10.1002/hep.27077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gustot T., Fernandez J., García E. Short-term (28-day) clinical course and transplant-free mortality in acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF): evidence for reversibility of ACLF (a study from the CANONIC database) J Hepatol. 2014;60:S228. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duseja A., Choudhary N.S., Gupta S., Dhiman R.K., Chawla Y. APACHE II score is superior to SOFA, CTP and MELD in predicting the short-term mortality in patients with acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF) J Dig Dis. 2013;14:484–490. doi: 10.1111/1751-2980.12074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shalimar, Kumar D., Vadiraja P.K. Acute on chronic liver failure because of acute hepatic insults: etiologies, course, extrahepatic organ failure and predictors of mortality. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;31:856–864. doi: 10.1111/jgh.13213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pamecha V., Kumar S., Bharathy K.G. Liver transplantation in acute on chronic liver failure: challenges and an algorithm for patient selection and management. Hepatol Int. 2015;9:534–542. doi: 10.1007/s12072-015-9646-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anand A.C., Dhiman R.K. Acute on chronic liver failure—what is in a ‘definition’? J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2016;6:233–240. doi: 10.1016/j.jceh.2016.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sarin K., Kumar A., Almeida J. Acute-on-chronic liver failure: consensus recommendations of the Asian Pacific association for the study of the liver (APASL) Hepatol Int. 2009;3:269–282. doi: 10.1007/s12072-008-9106-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dhiman R.K., Agrawal S., Gupta T., Duseja A., Chawla Y. Chronic Liver Failure-Sequential Organ Failure Assessment is better than the Asia-Pacific Association for the Study of Liver criteria for defining acute-on-chronic liver failure and predicting outcome. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:14934–14941. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i40.14934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Duseja A., Chawla Y.K., Dhiman R.K., Kumar A., Choudhary N., Taneja S. Non-hepatic insults are common acute precipitants in patients with acute on chronic liver failure (ACLF) Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:3188–3192. doi: 10.1007/s10620-010-1377-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garg H., Kumar A., Garg V., Sharma P., Sharma B.C., Sarin S.K. Clinical profile and predictors of mortality in patients of acute-on-chronic liver failure. Dig Liver Dis. 2012;44:16671. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2011.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Amarapurkar D., Dharod M.V., Chandnani M. Acute-on-chronic liver failure: a prospective study to determine the clinical profile, outcome, and factors predicting mortality. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2015;34:216–224. doi: 10.1007/s12664-015-0574-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pati G.K., Singh A., Misra B. Acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF) in coastal eastern India: “a single-center experience”. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2016;6:26–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jceh.2015.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shalimar, Saraswat V., Singh S.P. Acute-on-chronic liver failure in India: the Indian National Association for Study of the Liver consortium experience. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;31:1742–1749. doi: 10.1111/jgh.13340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gupta T., Dhiman R.K., Rathi S. Impact of hepatic and extrahepatic insults on the outcome of acute-on-chronic liver failure. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2017;7:9–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jceh.2016.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Choudhary A., Kumar M., Sharma B.C. Systemic inflammatory response syndrome in acute on chronic liver failure—relevance of ‘Golden Window’—a prospective study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017 doi: 10.1111/jgh.13799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Agrawal S., Duseja A., Gupta T., Dhiman R.K., Chawla Y. Simple organ failure count versus CANONIC grading system for predicting mortality in acute-on-chronic liver failure. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;30:575–581. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu C.L., Fan S.T., Lo C.M. Live-donor liver transplantation for acute-on-chronic hepatitis B liver failure. Transplantation. 2003;76:1174–1179. doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000087341.88471.E5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang Z.X., Yan L.N., Wang W.T., Xu M.Q., Yang J.Y. Impact of pretransplant MELD score on posttransplant outcome in orthotopic liver transplantationfor patients with acute-on-chronic hepatitis B liver failure. Transplant Proc. 2007;39:1501–1504. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2007.02.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chan A.C., Fan S.T., Lo C.M. Liver transplantation for acute-on-chronic liver failure. Hepatol Int. 2009;3:571–581. doi: 10.1007/s12072-009-9148-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bahirwani R., Shaked O., Bewtra M., Forde K., Reddy K.R. Acute-on-chronic liver failure before liver transplantation: impact on posttransplant outcomes. Transplantation. 2011;92:952–957. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31822e6eda. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ling Q., Xu X., Wei Q. Downgrading MELD improves the outcomes after liver transplantation in patients with acute-on-chronic hepatitis B liver failure. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e30322. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 27.Duan B.W., Lu S.C., Wang M.L. Liver transplantation in acute-on-chronic liver failure patients with high model for end-stage liverdisease (MELD) scores: a single center experience of 100 consecutive cases. J Surg Res. 2013;183:936–943. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2013.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xing T., Zhong L., Chen D., Peng Z. Experience of combined liver-kidney transplantation for acute-on-chronic liver failure patients with renal dysfunction. Transplant Proc. 2013;45:2307–2313. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2013.02.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Finkenstedt A., Nachbaur K., Zoller H. Acute-on-chronic liver failure: excellent outcomes after liver transplantation but high mortality on the wait list. Liver Transplant. 2013;19:879–886. doi: 10.1002/lt.23678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Artru F., Louvet A., Ruiz I. Liver transplantation in the most severely ill cirrhotic patients: a multicenter study in acute-on-chronic liverfailure grade 3. J Hepatol. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2017.06.009. pii: S0168-8278(17)32079-2. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moon D.B., Lee S.G., Kang W.H. Adult living donor liver transplantation for acute-on-chronic liver failure in high-model for end-stage liver disease score patients. Am J Transplant. 2017;17:1833–1842. doi: 10.1111/ajt.14198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Levesque E., Winter A., Noorah Z. Impact of acute-on-chronic liver failure on 90-day mortality following a first liver transplantation. Liver Int. 2017;37:684–693. doi: 10.1111/liv.13355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yadav S.K., Saraf N., Raut V. Living donor liver transplant for acute on chronic liver failure: single centre experience. O-112. Transplantation. 2017;101(5S2):S66–S67. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Knaak J., McVey M., Bazerbachi F. Liver transplantation in patients with end-stage liver disease requiring intensive care unit admission and intubation. Liver Transplant. 2015;21:761–767. doi: 10.1002/lt.24115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Petrowsky H., Rana A., Kaldas F.M. Liver transplantation in highest acuity recipients: identifying factors to avoid futility. Ann Surg. 2014;259:1186–1194. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Umgelter A., Lange K., Kornberg A., Büchler P., Friess H., Schmid R.M. Orthotopic liver transplantation in critically ill cirrhotic patients with multi-organ failure: a single-center experience. Transplant Proc. 2011;43:3762–3768. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2011.08.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Putignano A., Gustot T. New concepts in acute-on-chronic liver failure: implications for liver transplantation. Liver Transplant. 2017;23:234–243. doi: 10.1002/lt.24654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sarin S.K., Choudhary A. Acute-on-chronic liver failure: terminology, mechanisms and management. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;13:131–149. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2015.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Arroyo V., Moreau R., Kamath P.S. Acute-on-chronic liver failure in cirrhosis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2016;2:16041. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2016.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sen S., Davies N.A., Mookerjee R.P. Pathophysiological effects of albumin dialysis in acute-on-chronic liver failure: a randomized controlled study. Liver Transplant. 2004;10:1109–1119. doi: 10.1002/lt.20236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Laleman W., Wilmer A., Evenepoel P. Effect of the molecular adsorbent recirculating system and Prometheus devices on systemic haemodynamics and vasoactive agents in patients with acute-on-chronic alcoholic liver failure. Crit Care. 2006;10:R108. doi: 10.1186/cc4985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bañares R., Nevens F., Larsen F.S. Extracorporeal albumin dialysis with the molecular adsorbent recirculating system in acute-on-chronic liver failure: the RELIEF trial. Hepatology. 2013;57:1153–1162. doi: 10.1002/hep.26185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kribben A., Gerken G., Haag S. Effects of fractionated plasma separation and adsorption on survival in patients with acute-on-chronic liver failure. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:782–789.e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.12.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gerth H.U., Pohlen M., Thölking G. Molecular adsorbent recirculating system can reduce short-term mortality among patients with acute-on-chronic liver failure—a retrospective analysis. Crit Care Med. 2017 doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002562. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zheng Z., Li X., Li Z., Ma X. Artificial and bioartificial liver support systems for acute and acute-on-chronichepatic failure: a meta-analysis and meta-regression. Exp Ther Med. 2013;6:929–936. doi: 10.3892/etm.2013.1241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]