Abstract

Purpose

This study aimed to evaluate the clinicopathological characteristics of pregnancy-associated breast cancer (PABC) in comparison with non-pregnancy associated breast cancer (non-PABC).

Methods

A total of 344 eligible patients with PABC were identified in the Korean Breast Cancer Society Registry database. PABC was defined as ductal carcinoma in situ, invasive ductal carcinoma, or invasive lobular carcinoma diagnosed during pregnancy or within 1 year after the birth of a child. Patients with non-PABC were selected from the same database using a 1:2 matching method. The matching variables were operation, age, and initial stage.

Results

Patients with PABC had significantly lower survival rates than patient with non-PABC (10-year survival rate: PABC, 76.4%; non-PABC, 85.1%; p=0.011). PABC patients had higher histologic grade and were more frequently hormone receptor negative than non-PABC patients. Being overweight (body mass index [BMI], ≥23 kg/m2), early menarche (≤13 years), late age at first childbirth (≥30 years), and a family history of breast cancer were more common in the PABC group than in the non-PABC group. Multivariate analysis showed the following factors to be significantly associated with PABC (vs. non-PABC): early menarche (odds ratio [OR], 2.165; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.566–2.994; p<0.001), late age at first childbirth (OR, 2.446; 95% CI, 1.722–3.473; p<0.001), and being overweight (OR, 1.389; 95% CI, 1.007–1.917; p=0.045).

Conclusion

Early menarche, late age at first childbirth, and BMI ≥23 kg/m2 were more associated with PABC than non-PABC.

Keywords: Breast neoplasms, Pregnancy, Survival

INTRODUCTION

Pregnancy-associated breast cancer (PABC) is breast cancer diagnosed during pregnancy or the first postpartum year [1,2]. The incidence of PABC comprises 0.76% to 3.8% of all breast cancer cases [1]. The outcomes of treatment for PABC are generally poor. Bladström et al. [3] have used a Swedish population-based registry to study the survival rates of women with breast cancer who recently gave birth. They found that the 5- and 10-year survival rates were 52.1% and 43.9%, respectively, for patients who had been diagnosed during pregnancy. By contrast, the 5- and 10-year survival rates were 80% and 68.6%, respectively, for patients who had been diagnosed more than 10 years after childbirth [3]. Azim et al. [4] have investigated the prognosis of PABC in a meta-analysis and found that PABC was independently associated with worse overall and progression-free survival rates.

The poor prognosis of PABC might be caused by delays in diagnosis and obstacles to treatment. Diagnostic delay is a common phenomenon in PABC because the normal changes that occur during pregnancy obscure the signs and symptoms of the cancer. Furthermore, the fetus should be protected as much as possible during the treatment of the mother [1]. To improve the outcomes of patients with PABC, understanding its risk factors and tumor characteristics is important. However, this is difficult because the incidence of PABC is low. The Korean Breast Cancer Society (KBCS) Registry database provides a wide variety of information, including whether cases are PABC or non-PABC. We analyzed this nationwide database, which included data collected prospectively more than 15 years ago, to evaluate the clinicopathological characteristics of PABC patients compared with non-PABC patients.

METHODS

Korean Breast Cancer Society Registry

Managed by the KBCS, the KBCS Registry is a database that has been prospectively collecting data on breast cancer patients since 1996. A total of 102 general hospitals with at least 400 beds have decided to join this program. The registered factors include age, sex, surgical method, cancer pathologic stage (based on the seventh American Joint Committee on Cancer classification), height, weight, age at menarche, age at menopause, age at first childbirth, lactation history, hormone replacement therapy, family history, PABC or non-PABC, hormone receptor status, human epidermal receptor 2 status, and neoadjuvant or adjuvant treatments [5,6,7]. The details of the KBCS database have been described in a previous study [5].

Definitions

PABC was defined as breast cancer diagnosed during pregnancy or within 1 year of childbirth [1,2]. Overweight was defined as body mass index (BMI) ≥23.0 kg/m2, and obesity was defined as BMI ≥25.0 kg/m2, following recommendations for Asian populations [8].

Patients

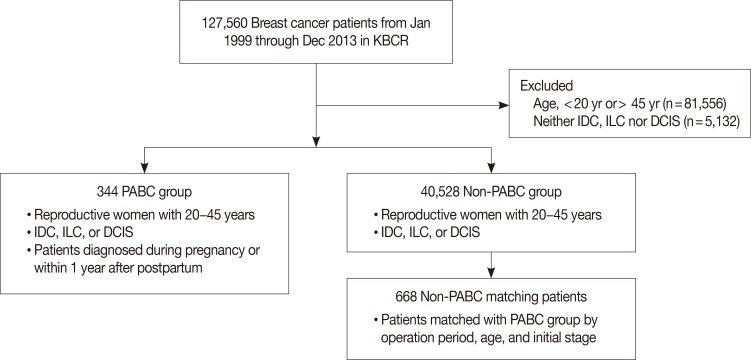

PABC and non-PABC patients were selected based on information from the KBCS Registry database. Using this database, 344 patients diagnosed with PABC between January 1989 and December 2013 were identified. Patients had to be between 20 and 45 years old to be included in the study. Figure 1 shows the flow diagram of patient selection. Non-PABC patients were selected from the KBCS Registry database using a general 1:2 matching method. The matching variables were year of operation, age, and initial stage. We began by matching patients by year of operation. Because different treatment strategies are associated with different operation periods, non-PABC patients were selected such that they underwent operations during the same year as did the PABC patients. Age and initial stage are typical prognostic factors. Therefore, we also matched patients in the two groups on these variables, to analyze the differences that remained in other characteristics. The matched patients were defined to have undergone their operations during the same year, to be the same age, and to have the same stage of disease. We showed supplementary table for full data compared non-PABC matching patient and non-PABC non-matching patient (Supplementary Table 1, available online). This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Korea Cancer Center Hospital (IRB number: K-1512-002-044).

Figure 1. Flow chart of patient selection.

KBCR=Korean Breast Cancer Society Registry; IDC=invasive ductal carcinoma; ILC=invasive lobular carcinoma; DCIS=ductal carcinoma in situ; PABC=pregnancy-associated breast cancer.

Statistical analyses

Chi-square tests were used to compare clinical values between the PABC group and non-PABC group. Binary logistic regression analysis was performed to evaluate PABC risk factors. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05. All statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS version 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA).

RESULTS

Patient symptoms

Asymptomatic disease was observed less frequently in PABC patients than in non-PABC patients (4.3% of PABC patients versus 9.1% of non-PABC patients). A lump was the most commonly reported symptom in both patients groups (Table 1).

Table 1. Patient-reported symptoms at diagnosis.

| Symptom | PABC (n = 344) No. (%) |

Non-PABC (n = 668) No. (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Asymptomatic | 14 (4.3) | 54 (9.1) |

| Lump | 283 (86.3) | 510 (86.0) |

| Pain | 24 (7.3) | 23 (3.9) |

| Nipple discharge | 30 (9.1) | 29 (4.9) |

| Skin change | 8 (2.4) | 7 (1.2) |

| Nipple retraction | 17 (5.2) | 12 (2.0) |

| Axillary mass | 16 (4.9) | 19 (3.2) |

PABC=pregnancy-associated breast cancer.

Patient characteristics and overall survival

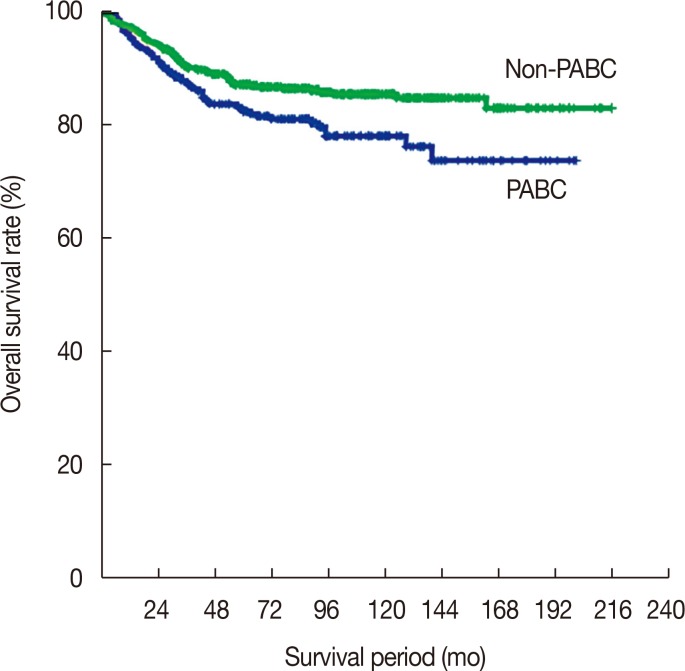

A total of 1,012 patients were analyzed in this study. The clinicopathological characteristics of PABC patients and non-PABC patients are shown in Table 2. The mean age was 33.7±4.3 years for PABC patients and 34.2±4.4 years for non-PABC patients (p=0.134). Because of our matching method, no significant difference in initial stage was noted between the PABC and non-PABC groups (p=0.121). However, the 10-year overall survival rate of PABC patients was worse than that of non-PABC patients (76.4% for PABC and 85.1% for non-PABC, p=0.011). The overall survival rates of PABC and non-PABC patients are shown in Figure 2. The median follow-up period was 84.9 months (range, 1–216 months). Compared with non-PABC patients, a significantly larger proportion of PABC patients were diagnosed with histologic grade 3 breast cancer. In addition, PABC patients were more likely to have hormone receptor negative cancer compared with non-PABC patients. In a multivariate analysis, hormone receptor negativity was associated with poor overall survival (hazard ratio [HR], 2.249; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.403–3.605; p=0.001). Histologic grade 3 did not show a statistically significant association with overall survival (HR, 1.026; 95% CI, 0.648–1.626; p=0.912).

Table 2. Clinicopathological characteristics of PABC patients and non-PABC patients.

| Characteristic | PABC (n = 344) No. (%) | Non-PABC (n = 668) No. (%) | p-value | Characteristic | PABC (n = 344) No. (%) | Non-PABC (n = 668) No. (%) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr)* | 33.7 ± 4.3 | 34.2 ± 4.4 | 0.134 | Nuclear grade | < 0.001 | ||

| Breast operation | 0.946 | 1 | 12 (3.5) | 45 (6.7) | |||

| BCS | 149 (43.3) | 301 (45.1) | 2 | 73 (21.2) | 193 (28.9) | ||

| Total mastectomy | 180 (52.3) | 357 (53.4) | 3 | 156 (45.4) | 215 (32.2) | ||

| Biopsy only | 15 (4.4) | 8 (1.2) | Unknown | 103 (29.9) | 215 (32.2) | ||

| Unknown | 0 | 2 (0.3) | Hormone receptor | < 0.001 | |||

| Axillary operation | 0.068 | Positive | 136 (39.5) | 358 (53.6) | |||

| SLNB | 41 (11.9) | 72 (10.8) | Negative | 172 (50.0) | 241 (36.1) | ||

| ALND | 276 (80.2) | 566 (84.7) | Unknown | 36 (10.5) | 69 (10.3) | ||

| No operation | 27 (7.9) | 30 (4.5) | HER2 status | 0.520 | |||

| T stage | 0.251 | Positive | 69 (20.1) | 129 (19.3) | |||

| T0 | 13 (3.8) | 18 (2.7) | Negative | 177 (51.5) | 331 (49.6) | ||

| T1 | 83 (24.1) | 179 (26.8) | Unknown | 98 (28.4) | 208 (21.2) | ||

| T2 | 155 (45.1) | 327 (49.0) | Chemotherapy | 1.000 | |||

| T3 | 66 (19.2) | 104 (15.6) | Yes | 289 (84.0) | 530 (79.3) | ||

| T4 | 25 (7.3) | 36 (5.4) | No | 34 (9.9) | 64 (9.6) | ||

| Unknown | 2 (0.6) | 4 (0.6) | Unknown | 21 (6.1) | 74 (11.1) | ||

| N stage | 0.827 | Radiotherapy | 0.178 | ||||

| N0 | 165 (48.0) | 339 (50.7) | Yes | ||||

| N1 | 97 (28.2) | 183 (27.4) | Post-BCS | 114 (33.1) | 247 (37.0) | ||

| N2 | 45 (13.1) | 77 (11.5) | PMRT | 62 (18.0) | 115 (17.2) | ||

| N3 | 31 (9.0) | 64 (9.6) | Palliative | 2 (0.6) | 1 (0.1) | ||

| Unknown | 6 (1.7) | 5 (0.7) | No | 124 (36.0) | 198 (29.6) | ||

| Stage | 0.123 | Unknown | 42 (12.2) | 107 (16.0) | |||

| 0 | 13 (3.8) | 18 (2.7) | Hormone therapy | < 0.001 | |||

| I | 62 (18.0) | 144 (21.6) | Yes | 123 (35.8) | 306 (45.8) | ||

| II | 154 (44.8) | 318 (47.6) | No | 164 (47.7) | 231 (34.6) | ||

| III | 95 (27.6) | 167 (25.0) | Unknown | 57 (16.6) | 131 (19.6) | ||

| IV | 20 (5.8) | 21 (3.1) | |||||

| Histologic grade | < 0.001 | ||||||

| 1 | 10 (2.9) | 55 (8.2) | |||||

| 2 | 94 (27.3) | 221 (33.1) | |||||

| 3 | 170 (49.4) | 249 (37.3) | |||||

| Unknown | 70 (20.4) | 143 (21.4) |

PABC=pregnancy-associated breast cancer; BCS=breast-conserving surgery; SLNB=sentinel lymph node biopsy; ALND=axillary lymph node dissection; HER2=human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; Post-BCS=post-breast conserving surgery radiotherapy; PMRT=post-mastectomy radiotherapy.

*Mean±SD.

Figure 2. Kaplan-Meier analysis of overall survival rates for pregnancy-associated breast cancer (PABC) patients and non-PABC patients (10-year overall survival rate: PABC, 76.4%; non-PABC, 85.1%; p=0.011).

Table 3 shows the differences in characteristics between PABC patients and non-PABC patients. The PABC patients were more likely to be overweight (≥23.0 kg/m2), have an early age at menarche (≤13 years), and have a late age at first delivery (≥30 years). Multivariate analysis showed that late age at first delivery (odds ratio [OR], 2.446; 95% CI, 1.722–3.473; p<0.001), early age at menarche (OR, 2.165; 95% CI, 1.566–2.994; p<0.001), and overweight (OR, 1.389; 95% CI, 1.007–1.917; p=0.045) were more associated with PABC than non-PABC (Table 4).

Table 3. Univariate analysis of characteristics of PABC compared with non-PABC.

| Characteristic | OR (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| BMI ( ≥ 23 kg/m2 vs. < 23 kg/m2) | 1.427 (1.086–1.876) | 0.011 |

| Oral pill (yes vs. no) | 1.265 (0.767–2.086) | 0.356 |

| Family history (yes vs. no) | 1.431 (0.921–2.225) | 0.111 |

| First delivery ( ≥ 30 yr vs. < 30 yr) | 2.655 (1.902–3.707) | < 0.001 |

| Menarche ( < 13 yr vs. ≥ 13 yr) | 1.762 (1.322–2.348) | < 0.001 |

PABC=pregnancy-associated breast cancer; OR=odds ratio; CI=confidence interval; BMI=body mass index.

Table 4. Multivariate analysis of characteristics of PABC compared with non-PABC.

| Characteristic | OR (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| BMI ( ≥ 23 kg/m2 vs. < 23 kg/m2) | 1.389 (1.007−1.917) | 0.045 |

| First delivery ( ≥ 30 yr vs. < 30 yr) | 2.446 (1.722−3.473) | < 0.001 |

| Menarche ( < 13 yr vs. ≥ 13 yr) | 2.165 (1.566−2.994) | < 0.001 |

PABC=pregnancy-associated breast cancer; OR=odds ratio; CI=confidence interval; BMI=body mass index.

DISCUSSION

This study is the first nationwide analysis of women with PABC in Korea. The overall survival rate was worse for the PABC group than for the non-PABC group. Symptomatic disease was more frequent in the PABC group. For both groups, a lump was the most commonly reported symptom. The following factors were significantly and independently associated with PABC (as compared with non-PABC): early age at menarche (≤13 years), late age at first delivery (≥30 years), and overweight (BMI ≥23.0 kg/m2). This study compared PABC patients and matched non-PABC patients. The number of non-PABC patients was higher than that of PABC patients. We used the matching method to analyze the characteristics of PABC and non-PABC in a comparative manner.

The poor overall survival rate that we observed among PABC patients is consistent with other studies [3,4]. In a study that compared risk factors between PABC patients and age-matched non-PABC patients, the following variables were significantly associated with the overall survival of patients with PABC: stage (stage III vs. stage I; HR, 5.25; 95% CI, 4.15–6.63; p<0.001), surgery type (modified total mastectomy vs. breast conserving surgery; HR, 1.17; 95% CI, 1.05–1.30; p=0.005), and negative status of hormone receptor (estrogen receptor negative and progesterone receptor negative) (HR, 1.20; 95% CI, 1.07–1.36; p=0.003). This study also showed that, among patients with localized stages of breast cancer, PABC is a significant risk factor for worse survival after controlling for several factors, such as surgery type, age, race, and hormone receptor status (p=0.049) [9]. In our study, the overall survival rate was poorer for PABC than non-PABC after applying the 1:2 matching method. This result may be attributable to PABC patients having cancers with worse biological features, such as negative status of hormone receptor. Furthermore, we studied the factors associated with PABC.

When women become pregnant, various physiological changes occur in the breast, including engorgement, hypertrophy, and nipple discharge. These changes can obscure the symptoms of breast cancer during pregnancy and confuse physicians [10], which may explain the low frequency of symptomatic patients in the PABC group.

Because PABC has not been investigated thoroughly, no generally accepted risk factors have been established for this disease [10]. In a recent study, Strasser-Weippl et al. [11] compared the characteristics between PABC patients and non-PABC patients. They showed that the age at first gestation was higher in PABC patients than in non-PABC patients (≥30 years, PABC 30.3% vs. non-PABC 10.8%, p<0.001). This result is consistent with our own finding that late age at delivery is more associated with PABC than with non-PABC. Moreover, we also found that early age at menarche and obesity were more associated with PABC than with non-PABC.

Compared with non-PABC patients, the higher rate of overweight among PABC patients may have resulted from the weight gain during pregnancy. To confirm whether rates of being overweight are truly higher in patients with PABC than those with non-PABC, future studies will need to investigate patient weights before pregnancy. This information is not part of the KBCS Registry database.

Our study had some limitations. First, disease-free survival rates and pregnancy outcomes could not be analyzed. However, the overall survival rate is an acceptable and powerful end-point in oncology. Although we did not investigate the disease-free survival rate or pregnancy outcomes, we believe that analyzing these factors would not change the power of our study. Second, like many other large databases, the KBCS Registry is missing some data.

In conclusion, our analysis shows that the following clinicopathological characteristics were more associated with PABC than with non-PABC: early age at menarche, late age at first childbirth, and BMI ≥23 kg/m2. Based on our results, future studies can identify risk factors for PABC by comparing PABC patients with healthy individuals. Such studies could contribute to improving survival by allowing early detection of PABC.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This article was supported by the Korean Breast Cancer Society. The contributors and their affiliations are as follows:

Sei Hyun Ahn, Asan Medical Center; Dong-Young Noh, Seoul National University Hospital; Seok Jin Nam, Samsung Medical Center; Eun Sook Lee, National Cancer Center; Byeong-Woo Park, Yonsei University Severance Hospital; Woo Chul Noh, Korea Cancer Center Hospital; Jung Han Yoon, Chonnam National University Hwasun Hospital; Soo Jung Lee, Yeungnam University Medical Center; Eun Kyu Lee, Seoul National University Bundang Hospital; Joon Jeong, Yonsei University Gangnam Severance Hospital; Sehwan Han, Ajou University School of Medicine; Ho Yong Park, Kyungpook National University Medical Center; Nam-Sun Paik, Ewha Womans University Mokdong Hospital; Young Tae Bae, Pusan National University Hospital; Hyouk Jin Lee, Saegyaero Hospital; Heung Kyu Park, Gachon University Gil Hospital; Seung Sang Ko, Dankook University Cheil General Hospital and Women's Healthcare Center; Byung Joo Song, The Catholic University of Korea Bucheon St. Mary's Hospital; Young Jin Suh, The Catholic University of Korea St. Vincent's Hospital; Sung Hoo Jung, Chonbuk National University Hospital; Se Heon Cho, Dong-A University Hospital; Sei Joong Kim, Inha University Hospital; Se Jeong Oh, The Catholic University of Korea Incheon St. Mary's Hospital; Byung Kyun Ko, Ulsan University Hospital; Ku Sang Kim, Ulsan City Hospital; Chanheun Park, Sungkyunkwan University Kangbuk Samsung Hospital; Jong-Min Baek, The Catholic University of Korea Yeuido St. Mary's Hospital; Ki-Tae Hwang, Seoul National University Boramae Medical Center; Je Ryong Kim, Chungnam National University Hospital; Jeoung Won Bae, Korea University Anam Hospital; Jeong-Soo Kim, The Catholic University of Korea Uijeongbu St. Mary's Hospital; Sun Hee Kang, Keimyung University School of Medicine Dongsan Medical Center; Geumhee Gwak, Inje University Sanggye Paik Hospital; Jee Hyun Lee, Soonchunhyang University Seoul Hospital; Tae Hyun Kim, Inje University Busan Paik Hospital; Myungchul Chang, Dankook University Hospital; Sung Yong Kim, Soonchunhyang University College of Medicine Cheonan Hospital; Jung Sun Lee, Inje University College of Medicine Haeundae Paik Hospital; Jeong-Yoon Song, Kyung Hee University Hospital at Gangdong; Hai Lin Park, Gangnam CHA University Hospital; Sun Young Min, Kyung Hee University Medical Center; Jung-Hyun Yang, Konkuk University Medical Center; Sung Hwan Park, Catholic University of Daegu Hospital; Woo-Chan Park, The Catholic University of Korea Seoul St. Mary's Hospital; Lee Su Kim, Hallym University Hallym Sacred Heart Hospital; Dong Won Ryu, Kosin University Gospel Hospital; Kweon Cheon Kim, Chosun University Hospital; Min Sung Chung, Hanyang University Seoul Hospital; Hee Boong Park, Park Hee Boong Surgical Clinic; Cheol Wan Lim, Soonchunhyang University Bucheon Hospital; Un Jong Choi, Wonkwang University Hospital; Beom Seok Kwak, Dongguk University Ilsan Hospital; Young Sam Park, Presbyterian Medical Center; Hyuk Jai Shin, Myongji Hospital; Young Jin Choi, Chungbuk National University Hospital; Doyil Kim, MizMedi Hospital; Airi Han, Yonsei University Wonju Severance Christian Hospital; Jong Hyun Koh, Cheongju St. Mary's Hospital; Sangyong Choi, Gwangmyeong Sungae Hospital; Daesung Yoon, Konyang University Hospital; Soo Youn Choi, Hallym University Kangdong Sacred Heart Hospital; Shin Hee Chul, Chung-Ang University Hospital; Jae Il Kim, Inje University Ilsan Paik Hospital; Jae Hyuck Choi, Jeju National University Hospital; Jin Woo Ryu, Chungmu General Hospital; Chang Dae Ko, Dr. Ko's Breast Clinic; Il Kyun Lee, The Catholic Kwandong University International St. Mary's Hospital; Dong Seok Lee, Bun Hong Hospital; Seunghye Choi, The Catholic University of Korea St. Paul's Hospital; Youn Ki Min, Cheju Halla General Hospital; Young San Jeon, Goo Hospital; Eun-Hwa Park, Ulsan University Gangneung Asan Hospital.

Footnotes

This study was supported by the Korean Breast Cancer Society.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Clinicopathologic characteristics of matching patients and non-matching patients in non-PABC

References

- 1.Pavlidis N, Pentheroudakis G. The pregnant mother with breast cancer: diagnostic and therapeutic management. Cancer Treat Rev. 2005;31:439–447. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2005.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bodner-Adler B, Bodner K, Zeisler H. Breast cancer diagnosed during pregnancy. Anticancer Res. 2007;27:1705–1707. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bladström A, Anderson H, Olsson H. Worse survival in breast cancer among women with recent childbirth: results from a Swedish population-based register study. Clin Breast Cancer. 2003;4:280–285. doi: 10.3816/cbc.2003.n.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Azim HA, Jr, Santoro L, Russell-Edu W, Pentheroudakis G, Pavlidis N, Peccatori FA. Prognosis of pregnancy-associated breast cancer: a metaanalysis of 30 studies. Cancer Treat Rev. 2012;38:834–842. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2012.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ahn SH, Son BH, Kim SW, Kim SI, Jeong J, Ko SS, et al. Poor outcome of hormone receptor-positive breast cancer at very young age is due to tamoxifen resistance: nationwide survival data in Korea: a report from the Korean Breast Cancer Society. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2360–2368. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.3754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ko BS, Noh WC, Kang SS, Park BW, Kang EY, Paik NS, et al. Changing patterns in the clinical characteristics of Korean breast cancer from 1996-2010 using an online nationwide breast cancer database. J Breast Cancer. 2012;15:393–400. doi: 10.4048/jbc.2012.15.4.393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Park HS, Chae BJ, Song BJ, Jung SS, Han W, Nam SJ, et al. Effect of axillary lymph node dissection after sentinel lymph node biopsy on overall survival in patients with T1 or T2 node-positive breast cancer: report from the Korean Breast Cancer Society. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21:1231–1236. doi: 10.1245/s10434-013-3350-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Inoue S, Zimmet P, Caterson I, Chunming C, Ikeda Y, Khalid AK, et al. The Asia-Pacific Perspective: Redefining Obesity and Its Treatment. Sydney: Health Communications Australia; 2000. p. 19. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rodriguez AO, Chew H, Cress R, Xing G, McElvy S, Danielsen B, et al. Evidence of poorer survival in pregnancy-associated breast cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112:71–78. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31817c4ebc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Amant F, Loibl S, Neven P, Van Calsteren K. Breast cancer in pregnancy. Lancet. 2012;379:570–579. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61092-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Strasser-Weippl K, Ramchandani R, Fan L, Li J, Hurlbert M, Finkelstein D, et al. Pregnancy-associated breast cancer in women from Shanghai: risk and prognosis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2015;149:255–261. doi: 10.1007/s10549-014-3219-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Clinicopathologic characteristics of matching patients and non-matching patients in non-PABC