Abstract

Backgrounds/Aims

The challenging dilemma of Mirizzi syndrome for operating surgeons arises from the difficulty to diagnose it preoperatively, and approximately 50% of cases are diagnosed intraoperatively. In this study, we analysed the effectiveness of diagnostic modalities and treatment options in our series of Mirizzi syndrome.

Methods

Patients had a preoperative or intraoperative diagnosis of Mirizzi syndrome, and were classified into three groups: Group 1: Incidental finding of Mirizzi syndrome intraoperatively (n=34). Group 2: Patients presented with jaundice, diagnosed by endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (n=17). Group 3: Patients diagnosed initially by ultrasound (n=13). Laparoscopic cholecystectomy was conducted in all 49 patients with Cendes type I disease. Partial cholecystectomy, common bile duct exploration, repair of fistula and t-tube placement was conducted on eight patients with Cendes type II and five patients with Cendes type III. Partial cholecystectomy with Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy was conducted in two patients with Cendes type IV disease.

Results

Sixty-four patients were diagnosed with Mirizzi syndrome. Morbidity rate was 3.1%. Mortality rate was 0%. Group 3 (patients diagnosed initially by ultrasound) had the best treatment outcome, the least morbidity, and the shortest hospital stay.

Conclusions

Suspected cases of Mirizzi syndrome should not be underestimated. Difficulty in establishing preoperative diagnosis is the major dilemma. As it is mostly encountered intraoperatively, the approach should be careful and logical to identify the correct type of Mirizzi by a thorough diagnostic laparoscopy and thus, provide optimum treatment for the subtype to achieve the best outcome.

Keywords: Mirizzi syndrome, Gallbladder stone, Impacted gallstone, Cholecystocholedochal fistula, Laparoscopic cholecystectomy, Open cholecystectomy

INTRODUCTION

Mirizzi syndrome, a complication of long-standing gallstone disease, has reported prevalence rate of 0.05–2.1% in developed Western countries, and 4.7–5.7% in other regions of the world. It occurs in approximately 0.1% of patients suffering from gallstones and found in 0.7–2.5% of cholecystectomies.1,2 Proposed pathophysiology is explained by impaction of stones in the cystic duct or neck of the gallbladder (Hartmann's pouch). Persistent impaction and chronic inflammatory response will cause external obstruction of the common bile duct (CBD), necrosis, fibrosis, and ultimately fuse into the CBD to form cholecystocholedochal fistula.3,4,5

Predisposing factors for development of Mirizzi syndrome were suggested to be a long cystic duct that is parallel to the bile duct and the low insertion of the cystic duct into the CBD.4 Recurrent or continuous impaction of gallstones may lead to repeated attacks of acute cholecystitis and will cause the gallbladder to become initially distended with thick inflamed walls, and consequently will become contracted and atrophic, characterized by thicker fibrotic walls. When the gallbladder becomes atrophic, its wall may become atrophic thick or thin; and in some cases, these walls could intimately adhere to the contained gallstones.5 Proximity of acutely or chronically inflamed gallbladder to the CBD could lead walls to fuse by the edematous inflammatory tissue. In time, it will become fibrotic contributing to external compression of the CBD and resulting in characteristic obstructive jaundice seen with this condition. This late process could be acute or chronic.6

Clinically, Mirizzi syndrome is presented as recurrent episodes of obstructive jaundice (60%–100%), right upper quadrant (RUQ) abdominal pain (50%–100%), recurrent cholangitis, and fever in a patient with known or suspected gallstone disease.7 Laboratory investigations may reveal leukocytosis, hyperbilirubinemia, high alkaline phosphatase, and elevated aminotransaminase levels, often observed with acute cholecystitis, pancreatitis, or cholangitis.8

Preoperative diagnosis of Mirizzi syndrome is often difficult and can be detected in approximately 8–62.5% of patients.9 Therefore, we evaluate and analyze effectiveness of diagnostic modalities and treatment options in our series of Mirizzi Syndrome in 64 Saudi Arabian patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A retrospective cohort database analysis of results of patients diagnosed and treated for Mirizzi syndrome January 2003-December 2012 in Al Ansar general public health hospital in Medina, Saudi Arabia was conducted. Ethical approval was granted from Al Ansar hospital ethical committee and the management guidelines and clinical pathway subcommittee of the quality care program at the same hospital. Accordingly, this study was designed based on clinical pathway and guidelines of treatment for gallbladder diseases at Al Ansar hospital.

Patients' inclusion criteria were preoperative, intraoperative, or postoperative diagnosis of Mirizzi syndrome in adults (older than 12 years old as per the Saudi Arabian ministry of health age guidelines). Consequently, presenting symptoms, positive abdominal signs, laboratory results, ultrasound report, computed tomography (CT) scan, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), patient's age, gender, and histopathological findings, type of Mirizzi syndrome, operative procedure, postoperative course, and complications were criteria tested in patients and recorded on a computerized database sheet.

Patients had the same standard preoperative workup protocol (complete blood count, coagulation profile, blood chemistry, chest x-ray, electrocardiogram, and abdominal ultrasound). Patients presented with jaundice had an abdominal CT scan with an intravenous contrast and preoperative diagnostic ERCP. Procedure and postoperative care were thoroughly explained to patients. All patients were admitted to the surgical ward one day before surgery, and discharged home after completing postoperative care.

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy was the standard surgical option for noncomplicated cases, and it started with a thorough diagnostic identification of the anatomy and pathology of the gallbladder, cystic duct, and CBD with screenshots to document findings. Open cholecystectomy and other surgical procedures were conducted according to advanced pathology encountered.

A digital database file was used to document patients' data. Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) program (Release 22) was used for data analysis. Results were represented by absolute frequencies, percentages, and mean.

RESULTS

A total of 64 patients were diagnosed as Mirizzi syndrome; 49 (76.6%) were females and 15 (23.4%) were males with females to males ratio of 3.3:1. Mean age was 41 years (range: 29–53). Incidence rate of Mirizzi syndrome in our hospital is 6.6%.

RUQ abdominal pain was the most common complaint, followed by nausea, vomiting. Tenderness at the right upper quadrant was the most frequent sign in the physical examination (Table 1).

Table 1. The presenting symptoms, signs, laboratory, ultrasound, and ERCP data of patients diagnosed with Mirizzi syndrome.

RUQ, right upper quadrant; AST, aspartate transaminase; ALT, alanine transaminase; ERCP, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography

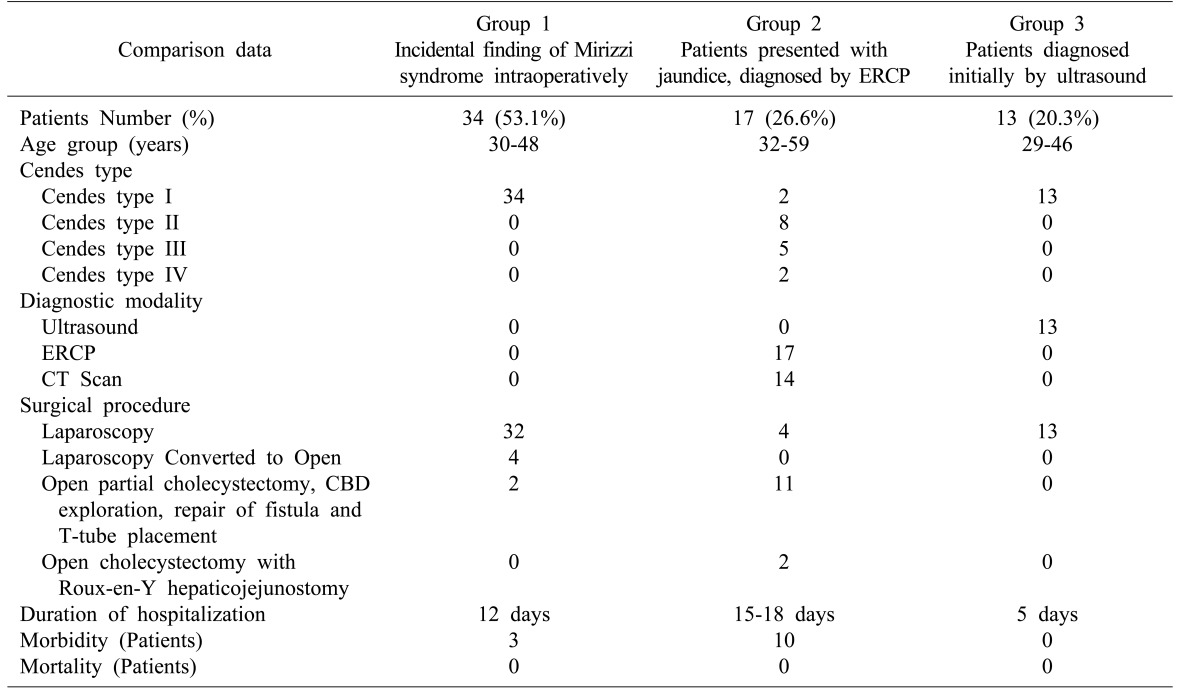

Patients were classified into three clinical groups: Group 1: Incidental finding of Mirizzi syndrome intraoperatively= 34 (53.1%) patients. Group 2: Patients presented with jaundice, diagnosed by ERCP=17 (26.6%) patients. Group 3: Patients diagnosed initially by ultrasound= 13 (20.3%) patients (Table 2).

Table 2. Comparison of the clinical pattern and treatment outcome between the three clinical study groups.

ERCP, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; CT, computed tomography; CBD, common bile duct

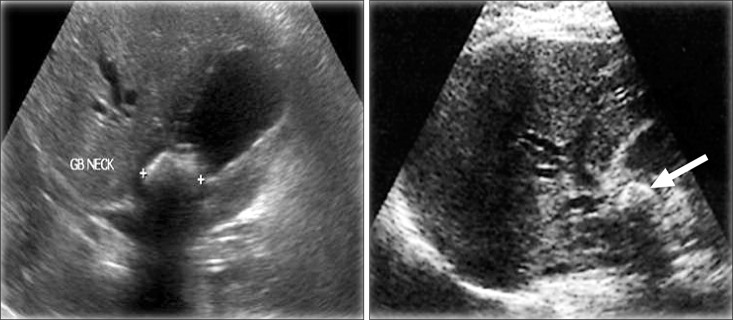

Ultrasound diagnosed gallbladder stones in all patients, 64 (100%), but only detected 13 (20.3%) of Mirizzi cases; ERCP detected 17 (26.6%), and CT scan detected 14 (21.9%). While the incidental finding of Mirizzi syndrome intraoperatively was 53.1% (Figs. 1 and 2).

Fig. 1. Ultrasound showing features of Mirizzi syndrome, a thick wall gallbladder with a large gallstone impacted in the Hartmann's pouch.

Fig. 2. Computed tomography showing features of Mirizzi syndrome, moderate to significant dilatation of intrahepatic biliary ducts and both common hepatic duct and the upper end of the common bile duct (CBD). There is a rounded lobulated area of hypodensity observed near the hepatic hilum 2.9 cm×2.7 cm in size likely a tortuous dilated hepatic duct. Distended gallbladder (around 12 cm) and showing a low density 2 cm size stone at the gallbladder neck likely causing pressure effects on the upper CBD and hepatic ducts and counting in the intrahepatic biliary dilatation. There are some faint hyperdensities observed at the distal CBD could be tiny stones or sludge.

According to Cendes classification, we classified patients based on intraoperative findings to 49 (76.6%) patients had Cendes type I disease, eight (12.5%) patients had Cendes type II disease, 5 (7.8 %) patients had Cendes type III disease, 2 (3.1%) patients had Cendes Type IV cholecystocholedochal fistula. There were no patients with Cendes type V disease.

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy was conducted in all 49 patients with Cendes type 1 disease, without CBD exploration. Conversion of laparoscopic cholecystectomy procedure to open cholecystectomy was conducted in four patients with Cendes type I. Open partial cholecystectomy, CBD exploration, repair of fistula and T-tube placement was conducted in eight patients with Cendes type II and five with Cendes type III. Open cholecystectomy with Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy conducted with two patients with Cendes type IV disease.

An intraperitoneal drain was placed in all cases. In patients with Cendes type I, the intraperitoneal drain was removed on the third postoperative day (when draining less than 50 ml/day); serosanguinous fluid was the most commonly recorded drained liquid. In patients with Cendes type II and III diseases; T-tube was removed on the seventh day according to our standard clinical pathway and intraperitoneal drain on the eighth day after conducting a follow-up abdominal CT scan with oral and intravenous contrast to check for biliary leaks (no cases recorded-0%). In patients with Cendes type IV disease, the intraperitoneal drain was removed on the eighth day. No significant drainage occurrence was recorded and no bile leak was reported.

Mean stone size for Mirizzi syndrome was 57 mm (range: 18–96 mm). Single large size stone was detected in 48 (75%) patients. Multiple small-medium size stone were detected in 16 (25%) patients. Dense fibrous adhesions were reported in all cases (100%). Thick wall gallbladder was reported in 54 (84.4%) patients. Contracted gallbladder was reported in 8 (12.5%) patients. Atrophic gallbladder was reported in only two (3.1%) patients.

Mean duration of hospitalization was as follows: Patients with Cendes type I: five days. Patients with Cendes type II: 12 days. Patients with Cendes type III: 15 days. Patients with Cendes type IV: 18 days.

The postoperative course was uneventful. Complications were of minor occurrence and not related to surgical procedures (fever in six patients due to atelectasis in smoking patients, chest infection in three patients, and urinary tract infection in two patients due to folly's catheter). Only two patients developed wound infections; all were Cendes type IV. Incidence of gallbladder cancer in postcholecystectomy specimen of Mirizzi syndrome patients was 0%.

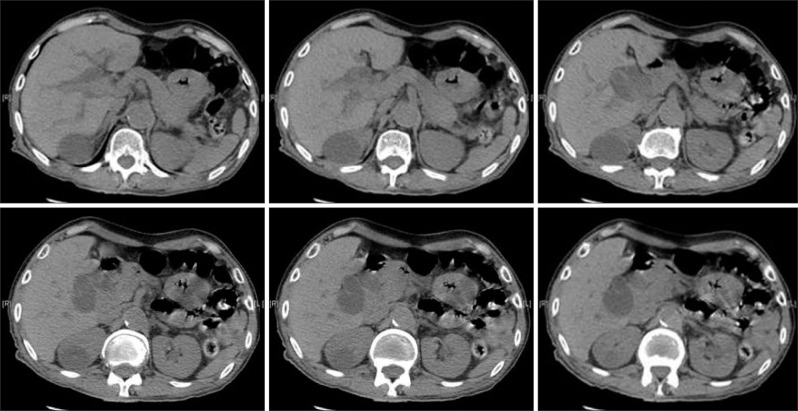

Patients completed three years follow-up postoperatively, and no late complications were recorded. Morbidity rate was (3.1%) and the mortality rate was 0% (Fig. 3, Table 3).

Fig. 3. Postoperative complications of patients diagnosed with Mirizzi syndrome.

Table 3. Comparison of the morbidity and mortality results from our study and international published articles.

DISCUSSION

Patient's age group in our series is 29–53 that is much lower than reported range worldwide and could be explained by the fact that most of our gallbladder disease patients are in the same age range. Conversely, female to male ratio agrees with results reported in the literature.10

In our study, 49 (76.6%) patients had Cendes type I disease. The majority of studies published in the literature have reported type I disease as the most frequent type (10.5% to 51%), and Mirizzi IV as uncommon (1% to 4%). Mirizzi V could manifest in up to 29% patients with other subtypes of Mirizzi.8 Only 2 (3.1%) patients in our series had Cendes type IV, consistent with the literature. In 1989, Csendes et al.11 classified Mirizzi syndrome into five (I to V) groups, to aid surgical treatment of patients. Beltran proposed a more simplified classification for Mirizzi syndrome12 (Tables 4 and 5).

Table 4. Csendes et al. classification of Mirizzi syndrome.

Table 5. Beltran simplified classification for Mirizzi syndrome.

Radiological diagnosis is initially by abdominal ultrasound that has diagnostic accuracy of 29%, with reported sensitivity varying from 8.3%–27%.9 CT has a sensitivity of 42%.13 Only 17 (26.6%) of our patients presented with clinically detected jaundice had a diagnostic CT scan. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) has a diagnostic accuracy of 50%.14 Unfortunately, MRCP was not available in our facility during the study period to be evaluated as preoperative diagnostic modality. Seventeen (26.6%) patients presented with clinically detected jaundice had a diagnostic ERCP, no therapeutic options were recorded. Reported diagnostic accuracy of Mirizzi syndrome with ERCP is approximately 55%–90%, with failure rate ranging from 5%–10%.15

Incidence of CBD injuries in patients operated for Mirizzi syndrome without preoperative diagnosis could be as high as 17%. If preoperative diagnosis could not be achieved, intraoperative recognition and proper management become essential. Inadequate appreciation of this condition leads to high preoperative morbidity and mortality.16 In our approach, a thorough initial diagnostic laparoscopy was the standard option to explicitly identify anatomy as well as pathology associated with CBD taking several screenshots for documentation, followed by careful and meticulous dissection and exploration of the cystic duct and artery with minimal traction conducted and a second diagnostic broad panoramic view before clipping and cutting the cystic artery and duct.

Management of Mirizzi syndrome is always surgical and is challenging for the operating surgeon because the condition is difficult to diagnose preoperatively and in 50% of cases is diagnosed during surgery. Distorted anatomy and dense adhesions due to severe inflammation are associated with significantly increased risk of CBD injury and bleeding.17 Intraoperative diagnosis is suggested by presence of dense fibrous adhesions between the gallbladder and CBD, and a contracted gallbladder.15 In our study, 53.1% of cases that identified intraoperatively had the same features. Dense adhesions were reported in all cases.

It has been suggested that in patients with suspected Mirizzi syndrome, fundus first approach is recommended.16 Fundus of the gallbladder is opened, the stone is extracted and cystic duct stone is retrieved from the gallbladder, a reasonable approach we conducted in four cases, but it needs much attention not to cause perforation or avulsion of the cystic duct, and more importantly, to avoid CBD injury.

The most common surgical option for Cendes type I is partial, open, or laparoscopic cholecystectomy. In our series, laparoscopic cholecystectomy was conducted in 49 patients with Cendes type I disease. Dissection of fibrous adhesion was the difficult part of the procedure. Fortunately, no complications were recorded, and no CBD injury was documented.

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy was a choice that could be carefully conducted in most patients with Mirizzi syndrome type I. Conversely, it is not recommended for type II or higher. A safe, successful laparoscopic cholecystectomy in patients with Mirizzi type I could be predicted by clear visualization of the cystic duct during initial dissection of Calot's triangle. In 2003, an article reported results of laparoscopic cholecystectomy with Mirizzi syndrome. It had a conversion rate to open of 31%–100%, complication rate of 0%–60%, CBD injury rate of 0%–22%, and mortality rate of 0%–25%.17 In our series, conversion from laparoscopic cholecystectomy to open cholecystectomy was conducted in four patients due to severe inflammation in Calot's triangle that made dissection of the cystic duct and cystic artery hazardous. We preferred clipping rather than suturing for all procedures conducted to minimize tissue trauma.

As disease progresses, the anatomy will eventually become much disturbed, thus making conventional surgery considerably difficult. Patients with Cendes types II–IV will ultimately require other intervention in addition to partial cholecystectomy. Partial cholecystectomy followed by closure of the fistula with T-tube placement in the CBD was reported as adequate for most of the patients with Cendes type II and III disease.18 In our study, eight patients with Cendes type II and three patients with Cendes type III diseases underwent partial cholecystectomy and repair over T-tube and recovered without complication.

Most published clinical reports recommended Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy as the procedure suitable for type IV disease. Conversely, choledochoduodenostomy should be avoided in the absence of adequately dilated CBD.19 In our study, Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy was the choice for the two patients with type IV Mirizzi syndrome.

Postoperative complications and mortality rates in our study were minimal despite that complexity of the diseases had progressed in approximately one-third of patients while other earlier studies revealed that as the disease progresses, mortality and morbidity rates increase.7,20,21,22,23,24 Due to the careful approach we used in all patients, and that is the most significant message of this study, Mirizzi syndrome cases should not be underestimated.

Recent published reports associated gallbladder cancer with subtypes of Mirizzi syndrome with an incidence of 5.3%–28% of patients. It was discovered exclusively in patients with subtype II or higher, and patients diagnosed with Mirizzi syndrome with biliary-enteric fistulas (Mirizzi subtype Va).25 In our series, histopathology examination of the gallbladder postoperatively was negative for malignant changes in all patients.

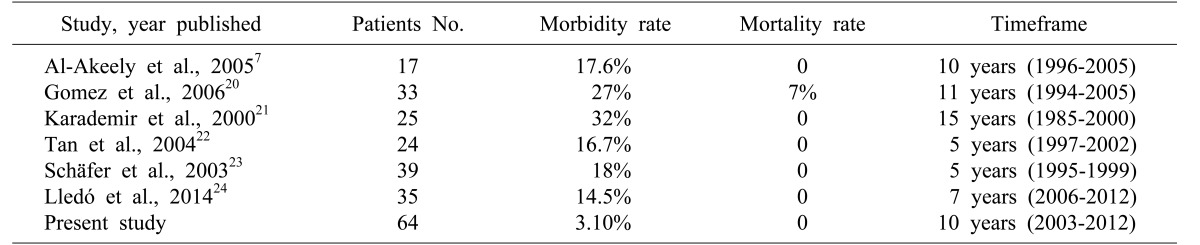

Comparing the three groups in our study, group 3 (patients diagnosed initially by ultrasound) had the best treatment outcome, the least morbidity, and the shortest hospital stay. It indicates the significance of preoperative diagnosis and thus, a careful treatment approach. Accordingly, we developed a treatment algorithm and clinical pathway for management of Mirizzi syndrome in our hospital that significantly improved our safe approach to address challenges of Mirizzi syndrome cases (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Clinical algorithm for management of Mirizzi syndrome.

Given our results and based on our protocol, we would like to emphasize stress significant messages of this study. First, for suspected cases of Mirizzi syndrome preoperatively by abdominal ultrasound, a more specialized radiological investigation should be considered. We recommend abdominal CT scan and ERCP, or MRCP if available. Second, for the incidental intraoperative not suspected case of Mirizzi syndrome preoperatively by abdominal ultrasound, we recommend a meticulous, thorough, initial diagnostic laparoscopy to evaluate anatomy and pathology encountered, and carefully assess the length of the cystic duct for safe clipping and cutting. Third, we strongly emphasize meticulous, careful dissection and minimal traction to avoid CBD injury. Documentation by screenshots is always a prudent step clinically and medicolegally. Fourth, if laparoscopic dissection is difficult or the pathology encountered is too hazardous to be managed by laparoscopy, conversion to open is mandatory and safer; no hesitation should be considered even by an experienced surgeon.

In conclusion, suspected cases of Mirizzi syndrome should not be underestimated. Difficulty in establishing preoperative diagnosis is a major dilemma. As it is mostly encountered intraoperatively, the approach should be careful and logical to identify the correct type of Mirizzi by a thorough diagnostic laparoscopy and thus, provide optimum treatment for the particular subtype to achieve the best management outcome.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge the late Dr. Abdul monem Al hadi (died 2013), and the late Dr. Ahmad Deghaidi (died 2014) for their clinical participation in the surgical part of this study.

References

- 1.Elhanafy E, Atef E, El Nakeeb A, Hamdy E, Elhemaly M, Sultan AM. Mirizzi syndrome: How it could be a challenge. Hepatogastroenterology. 2014;61:1182–1186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnson LW, Sehon JK, Lee WC, Zibari GB, McDonald JC. Mirizzi's syndrome: experience from a multi-institutional review. Am Surg. 2001;67:11–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chan CY, Liau KH, Ho CK, Chew SP. Mirizzi syndrome: a diagnostic and operative challenge. Surgeon. 2003;1:273–278. doi: 10.1016/s1479-666x(03)80044-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abou-Saif A, Al-Kawas FH. Complications of gallstone disease: Mirizzi syndrome, cholecystocholedochal fistula, and gallstone ileus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:249–254. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05451.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bedirli A, Kerem M, Bostanci H, Karakan T, Sahin TT, Akyurek N. Coexistence of Mirizzi syndrome with adenomyomatosis in the gallbladder: report of a case. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2007;6:438–441. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beltran MA, Csendes A. Mirizzi syndrome and gallstone ileus: an unusual presentation of gallstone disease. J Gastrointest Surg. 2005;9:686–689. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2004.09.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Al-Akeely MH, Alam MK, Bismar HA, Khalid K, Al-Teimi I, Al-Dossary NF. Mirizzi syndrome: ten years experience from a teaching hospital in Riyadh. World J Surg. 2005;29:1687–1692. doi: 10.1007/s00268-005-0100-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karakoyunlar O, Sivrel E, Koc O, Denecli AG. Mirizzi's syndrome must be ruled out in the differential diagnosis of any patients with obstructive jaundice. Hepatogastroenterology. 1999;46:2178–2182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yonetci N, Kutluana U, Yilmaz M, Sungurtekin U, Tekin K. The incidence of Mirizzi syndrome in patients undergoing endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2008;7:520–524. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhong H, Gong JP. Mirizzi syndrome: experience in diagnosis and treatment of 25 cases. Am Surg. 2012;78:61–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Csendes A, Díaz JC, Burdiles P, Maluenda F, Nava O. Mirizzi syndrome and cholecystobiliary fistula: a unifying classification. Br J Surg. 1989;76:1139–1143. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800761110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beltrán MA. Mirizzi syndrome: history, current knowledge and proposal of a simplified classification. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:4639–4650. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i34.4639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Waisberg J, Corona A, de Abreu IW, Farah JF, Lupinacci RA, Goffi FS. Benign obstruction of the common hepatic duct (Mirizzi syndrome): diagnosis and operative management. Arq Gastroenterol. 2005;42:13–18. doi: 10.1590/s0004-28032005000100005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lai EC, Lau WY. Mirizzi syndrome: history, present and future development. ANZ J Surg. 2006;76:251–257. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2006.03690.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kamalesh NP, Prakash K, Pramil K, George TD, Sylesh A, Shaji P. Laparoscopic approach is safe and effective in the management of Mirizzi syndrome. J Minim Access Surg. 2015;11:246–250. doi: 10.4103/0972-9941.140216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hubert C, Annet L, van Beers BE, Gigot JF. The "inside approach of the gallbladder" is an alternative to the classic Calot's triangle dissection for a safe operation in severe cholecystitis. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:2626–2632. doi: 10.1007/s00464-010-0966-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kwon AH, Inui H. Preoperative diagnosis and efficacy of laparoscopic procedures in the treatment of Mirizzi syndrome. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;204:409–415. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2006.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beltran MA, Csendes A, Cruces KS. The relationship of Mirizzi syndrome and cholecystoenteric fistula: validation of a modified classification. World J Surg. 2008;32:2237–2243. doi: 10.1007/s00268-008-9660-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Safioleas M, Stamatakos M, Safioleas P, Smyrnis A, Revenas C, Safioleas C. Mirizzi syndrome: an unexpected problem of cholelithiasis. Our experience with 27 cases. Int Semin Surg Oncol. 2008;5:12. doi: 10.1186/1477-7800-5-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gomez D, Rahman SH, Toogood GJ, Prasad KR, Lodge JP, Guillou PJ, et al. Mirizzi's syndrome--results from a large western experience. HPB (Oxford) 2006;8:474–479. doi: 10.1080/13651820600840082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karademir S, Astarcioğlu H, Sökmen S, Atila K, Tankurt E, Akpinar H, et al. Mirizzi's syndrome: diagnostic and surgical considerations in 25 patients. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2000;7:72–77. doi: 10.1007/s005340050157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tan KY, Chng HC, Chen CY, Tan SM, Poh BK, Hoe MN. Mirizzi syndrome: noteworthy aspects of a retrospective study in one centre. ANZ J Surg. 2004;74:833–837. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-1433.2004.03184.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schäfer M, Schneiter R, Krähenbühl L. Incidence and management of Mirizzi syndrome during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. 2003;17:1186–1190. doi: 10.1007/s00464-002-8865-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lledó JB, Barber SM, Ibañez JC, Torregrosa AG, Lopez-Andujar R. Update on the diagnosis and treatment of mirizzi syndrome in laparoscopic era: our experience in 7 years. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2014;24:495–501. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0000000000000079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Prasad TL, Kumar A, Sikora SS, Saxena R, Kapoor VK. Mirizzi syndrome and gallbladder cancer. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2006;13:323–326. doi: 10.1007/s00534-005-1072-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]