Abstract

Rationale: Infants whose mothers smoked during pregnancy demonstrate lifelong decreases in pulmonary function. DNA methylation changes associated with maternal smoking during pregnancy have been described in placenta and cord blood at delivery, in fetal lung, and in buccal epithelium and blood during childhood. We demonstrated in a randomized clinical trial (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier, NCT00632476) that vitamin C supplementation to pregnant smokers can lessen the impact of maternal smoking on offspring pulmonary function and decrease the incidence of wheeze at 1 year of age.

Objectives: To determine whether vitamin C supplementation reduces changes in offspring methylation in response to maternal smoking and whether methylation at specific CpGs is also associated with respiratory outcomes.

Methods: Targeted bisulfite sequencing was performed with a subset of placentas, cord blood samples, and buccal samples collected during the NCT00632476 trial followed by independent validation of selected cord blood differentially methylated regions, using bisulfite amplicon sequencing.

Measurements and Main Results: The majority (69.03%) of CpGs with at least 10% methylation difference between placebo and nonsmoker groups were restored (by at least 50%) toward nonsmoker levels with vitamin C treatment. A significant proportion of restored CpGs were associated with phenotypic outcome with greater enrichment among hypomethylated CpGs.

Conclusions: We identified a pattern of normalization in DNA methylation by vitamin C supplementation across multiple loci. The consistency of this pattern across tissues and time suggests a systemic and persistent effect on offspring DNA methylation. Further work is necessary to determine how genome-wide changes in DNA methylation may mediate or reflect persistent effects of maternal smoking on lung function.

Keywords: epigenetics, ascorbic acid, nicotine, prenatal exposure, asthma

At a Glance Commentary

Scientific Knowledge on the Subject

Infants whose mothers smoked during pregnancy demonstrate lifelong decreases in pulmonary function and increased risk of asthma. Exposure to maternal smoking in utero is also associated with alterations in DNA methylation at birth, some of which persist into childhood and adolescence.

What This Study Adds to the Field

Vitamin C supplementation administered to pregnant women who will not quit smoking may be a safe and inexpensive measure that improves offspring respiratory function and health through a mechanism involving prevention of alterations in DNA methylation. Identification of methylation targets may point to key pathways underlying the effects of smoking on lung development and the protective effects of vitamin C supplementation.

Rates of smoking during pregnancy are surprisingly high despite antismoking efforts, and approximately 50% of all smokers will continue to smoke on becoming pregnant (1). It is estimated that at least 12% of infants born in the United States are exposed prenatally to maternal smoking (2). Tobacco smoke exposure in utero is the largest preventable cause of low birth weight, preterm delivery, and infant mortality, and is associated with lifelong decreases in pulmonary function and increased risk of childhood asthma (3–7). Thus, understanding the mechanism by which maternal smoking affects lung development and finding ways to prevent those effects are critical.

Epigenetic programming is likely involved in the lifelong consequences of maternal smoking on respiratory function. The epigenome plays a crucial role in the developmental origins of disease, and maternal smoking during pregnancy is now clearly linked to tissue-specific global and gene-specific DNA methylation patterns in the developing fetus, cord blood, and placenta (8–14). Analyses of blood and buccal methylation demonstrate that alterations at some loci persist into childhood and even adolescence (14–16). Moreover, changes in methylation at specific loci are linked to functional consequences of maternal smoking, such as preterm birth, reduced fetal growth, and increased risk of asthma and wheeze (17–20).

Vitamin C (ascorbic acid) is an essential vitamin that cannot be synthesized in humans and needs to be consumed through the diet or dietary supplements to prevent disorders of its deficiency. Cigarette smoking has been shown to significantly reduce levels of circulating vitamin C in the plasma; in pregnant smokers this deficiency extends to the developing fetus (21, 22). In addition to its well-known antioxidant function, vitamin C serves as an essential cofactor to numerous monooxygenases and dioxygenases, including the ten-eleven translocation (TET) enzyme family, which catalyzes the hydroxylation of 5-methylcytosine (5mC) to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC) in the active process of DNA demethylation (23).

In a randomized, double-blind clinical trial (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier, NCT00632476), 500 mg of daily supplemental vitamin C (started at ≤22 wk of gestation) administered to women who would not quit smoking during pregnancy improved newborn pulmonary function and decreased incidence of wheeze through 1 year of age (24). We sought to determine whether maternal smoking–associated DNA methylation levels in placentas, cord blood, or buccal epithelia (collected between 3 and 6 yr of age) within this patient cohort were prevented or restored by supplementation with vitamin C in association with improvements in lung function. Some of the results of this study have been previously published in the form of abstracts (25, 26).

Methods

Study Participants and Sample Collection

The recruitment and randomization of participants for the clinical study (Evaluating the Effects of Supplemental Vitamin C on Infant Lung Function in Pregnant Smoking Women; NCT00632476) were conducted in three sites in the Pacific Northwest between March 2007 and January 2011 (24). The study was approved by the institutional review boards at each institution, and written informed consent was obtained for each enrolled patient. Placenta and cord blood samples were collected at the time of delivery from a subset of study participants. Caregivers of infants were later reconsented to conduct follow-up buccal swab sampling in the children.

Targeted Bisulfite Sequencing

We designed a custom pool of biotinylated RNA probes to genes previously identified with methylation and/or expression changes in the offspring of pregnant smokers and additional gene candidates (477 gene regions ± 20 kb; see the online supplement for full targeting strategy) (9, 12, 27–29). Genomic DNA libraries were prepared from placentas (n = 27), cord blood (n = 27), or buccal swabs (n = 22) (ages 3–6 yr), using Methyl-Seq reagents and protocol (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). Samples from 41 study participants were used in making libraries. All three tissues were available for 5 subjects, two of three tissues were available for 28 subjects, and one tissue was represented by the remaining 8 subjects (see Figure E1 in the online supplement).

Differential Methylation Analysis

Our bioinformatic pipeline and coverage criteria are described in the online supplement. For each tissue, multiple analysis of variance (ANOVA) for group, sex, and interaction effects was performed, using a custom R script. Pairwise post hoc tests using contrast technique between groups were performed on all CpGs passing the overall significance F tests by ANOVA (P ≤ 0.05), and both unadjusted and false discovery rate (FDR)-adjusted P values were retrieved, using the R stats package.

Functional Enrichment Analysis

We used DAVID version 6.7 with default settings for functional annotation clustering (30). The background list included all gene regions captured by our custom probes. We restricted our functional analysis to CpGs associated with maternal smoking and restored by vitamin C. In cord blood and buccal DNAs, our gene lists were limited to FDR-significant CpGs. In placenta we used nominal P values, as the FDR cutoff left only one CpG. Results include clusters with enrichment score greater than 1.2 and category Benjamini-Hochberg–adjusted P values less than 0.05.

Differentially Methylated Region Analysis

Nominal P values for pairwise t tests were sorted by chromosome and position, split into chromosome-specific input using R, and read into comb-p version 0.32 (31), using the following parameters: dist, 2000; step, 500; seed, 0.05. Differentially methylated regions (DMRs) with a Šidák-corrected P value not exceeding 0.05 were annotated to the nearest gene and CpG island, using BEDTools (32) and UCSC Genome Browser tracks for the human genome version hg19 (33).

Validation of DNA Methylation Results

A subset of cord blood DMRs was selected for independent, internal validation (selection criteria described in the online supplement), using bisulfite amplicon sequencing (BSAS). BSAS primers and protocol are provided in the online supplement (Table E8). In addition, external validation by replication analysis was performed by meta-analysis of DNA methylation in newborn cord blood associated with sustained maternal smoking during pregnancy, as described in the online supplement (34).

Respiratory Phenotype Association

We evaluated whether CpGs significantly associated with maternal smoking and restored by vitamin C supplementation were enriched, relative to all CpGs tested, for association with either of two phenotypic outcomes measured in our randomized clinical trial: (1) wheeze at 1 year of age and (2) a measurement of newborn pulmonary function: the ratio of time to peak tidal expiratory flow to expiratory time (TPTEF:TE) (24). To test for enrichment, we calculated the hypergeometric probability for hypomethylated and hypermethylated CpGs separately (described in the online supplement).

Results

Patient characteristics of the NCT00632476 cohort were published previously (see Table 1 in Reference 24) along with data on pulmonary function and wheeze. We achieved greater than 10× sequence depth for 10,902 of the 11,703 probes (93.2%) included in our capture design, which corresponds to more than 70,000 CpGs per tissue (placenta, 79,258; cord blood, 81,461; buccal epithelium, 71,955). On average, the median depth per sample was 45× in placenta, 39× in cord blood, and 37× in buccal epithelium. Covariate analysis (described in the online supplement) identified significant correlation of raw methylation with sex and library batch, prompting us to perform ComBat adjustment for batch effects (35) and to include sex in our statistical model (Figure E2).

Table 1.

Summary of CpG Changes Associated with Maternal Smoking and Reversed by Vitamin C Supplementation

| Placenta | Cord Blood | Buccal Cells | Overall | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (nonsmokers, placebo, vitamin C) | (12, 6, 9) | (11, 8, 9) | (6, 8, 8) | |

| CpGs tested by ANOVA | 79,258 | 81,464 | 71,955 | |

| Hypomethylated* | 267 | 300 | 214 | 781 |

| Proportion restored (95% CI)† | 64.42% (58.32–70.10%) | 81.33% (76.36–85.49%) | 87.85% (82.53–91.77%) | 77.34% (74.20–80.20%) |

| Hypermethylated‡ | 191 | 209 | 227 | 627 |

| Proportion restored (95% CI)† | 51.31% (44.01–58.56%) | 59.33% (52.32–65.99%) | 64.32% (57.67–70.47%) | 58.69% (54.72–62.56%) |

Definition of abbreviations: ANOVA = analysis of variance; CI = confidence interval.

Mean placebo − mean nonsmoker ≤ −10%; nominal P ≤ 0.05.

−(mean vitamin C − mean placebo)/(mean placebo − mean nonsmoker) × 100 ≥ 50%; proportion and CI calculated with prop.test in R.

Mean placebo − mean nonsmoker ≥ 10%; nominal P ≤ 0.05.

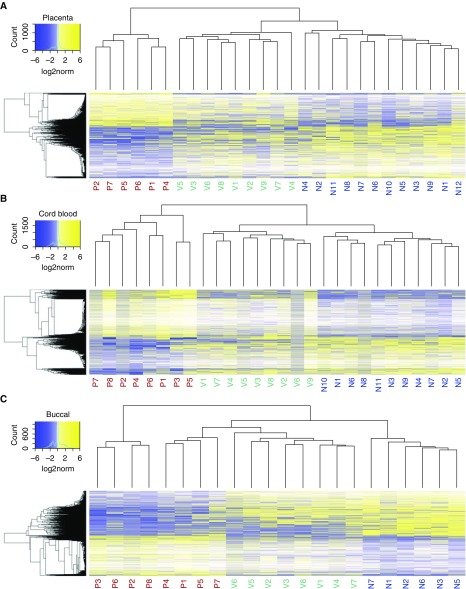

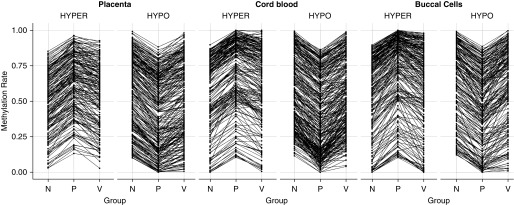

In each tissue, we detected more than 3,000 CpGs with variable methylation between groups (P ≤ 0.05; placenta, 3,112 CpGs; cord blood, 4,527 CpGs; buccal epithelium, 3,378 CpGs). Consistent with previous studies, maternal smoking was associated with significant differences in DNA methylation between the offspring of nonsmokers versus those of placebo-treated smokers (nominal pairwise P ≤ 0.05; placenta, 1,297 CpGs; cord blood, 2,337 CpGs; buccal epithelium, 1,572 CpGs). Unsupervised hierarchical clustering of CpGs differentially methylated with maternal smoking (based on nominal P value, regardless of magnitude) revealed that DNA methylation of patients born to vitamin C–supplemented smokers was more similar to that of nonsmokers than to that of placebo-treated smokers in all three tissues (Figure 1). Remarkably, 77.34% of hypomethylated CpGs and 58.69% of hypermethylated CpGs in placebo versus nonsmokers (nominal pairwise P ≤ 0.05; change in methylation ≥ 10%) were restored by vitamin C treatment by at least 50% of the difference between smokers and placebo (Figure 2 and Table 1).

Figure 1.

DNA methylation changes associated with maternal smoking at targeted loci are blunted by vitamin C supplementation. Heatmaps were generated with CpGs differentially methylated between nonsmokers and placebo groups by pairwise t test (nominal P ≤ 0.05). Raw methylation was log2 scaled and mean centered for each CpG to normalize distribution before statistical testing (see the color keys). Samples from patients born to vitamin C–supplemented smokers (green, V1–Vn) cluster closer to the nonsmoking group (blue, N1–Nn) than to the placebo group (red, P1–Pn) in (A) placenta, (B) cord blood, and (C) buccal epithelium.

Figure 2.

Vitamin C treatment reverses the majority of significant DNA methylation changes associated with maternal smoking at targeted loci. Points represent mean methylation for nonsmokers (N), placebo-treated smokers (P), and vitamin C–supplemented smokers (V) at each CpG with significant change in methylation (≥10%; nominal P ≤ 0.05) between the placebo and nonsmoker groups. CpGs are clustered by the direction of change with maternal smoking (HYPER/HYPO) and lines represent the direction of change at each CpG in nonsmokers versus placebo and placebo versus vitamin C mean methylation.

After removing CpGs affected by sex and performing FDR adjustment of pairwise P values for both nonsmokers versus placebo and placebo versus vitamin C, we identified 203 significantly restored CpGs among all three tissues (top 10 per tissue in Table 2; no magnitude filter). Overlap between tissues at the CpG level was minimal, with only nine CpGs nominally significant in both cord blood and buccal DNA. In cord blood, 118 restored CpGs (72 hypomethylated with maternal smoking, 46 hypermethylated) mapped to 99 unique loci. Functional annotation clustering revealed enrichment for categories involved in neuronal and placental development, cancer and oncogenesis, chromosomal rearrangement, and drug and glutathione metabolism. In buccal epithelium, 84 restored CpGs (60 hypomethylated, 24 hypermethylated) mapped to 76 unique loci, enriched for gene categories related to signaling and glycoproteins as well as cancer. Only one hypermethylated placental CpG survived FDR multiple testing correction between nonsmokers and placebo, located in a CpG island within the promoter of ST3GAL1. The majority of functionally enriched categories for nominally significant CpGs in placenta included terms related to extracellular matrix (Table E2).

Table 2.

Top Ten CpGs Associated with Maternal Smoking and Restored with Vitamin C per Tissue*

| Mapped Gene | Chr | Position (bp) | Nonsmoker (Mean ± SE) | Placebo (Mean ± SE) | Vitamin C (Mean ± SE) |

P Value |

% Restored† | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nonsmoker vs. Placebo FDR | Vitamin C vs. Placebo FDR | |||||||

| Top 10 CpGs in placenta | ||||||||

| ST3GAL1 | 8 | 134583256 | 0.005 ± 0.001 | 0.092 ± 0.007 | 0.004 ± 0.001 | 3.26 × 10−3 | 3.12 × 10−3 | 101.15 |

| COL11A2 | 6 | 33147259 | 0.936 ± 0.003 | 1 ± 0 | 0.9 ± 0.003 | 6.67 × 10−2 | 5.79 × 10−3 | 156.25 |

| RXRA | 9 | 137263360 | 0.95 ± 0.003 | 0.844 ± 0.006 | 0.969 ± 0.003 | 6.67 × 10−2 | 1.28 × 10−2 | 117.92 |

| NCOR2 | 12 | 124893686 | 0.991 ± 0.001 | 0.943 ± 0.003 | 0.994 ± 0.002 | 6.67 × 10−2 | 2.37 × 10−2 | 106.25 |

| CCBE1 | 18 | 57362673 | 0.847 ± 0.003 | 0.773 ± 0.004 | 0.874 ± 0.005 | 6.67 × 10−2 | 2.47 × 10−2 | 136.49 |

| ZCCHC14 | 16 | 87442996 | 0.939 ± 0.003 | 0.875 ± 0.008 | 0.965 ± 0.002 | 6.67 × 10−2 | 5.03 × 10−2 | 140.63 |

| CCM2 | 7 | 45038259 | 0.627 ± 0.003 | 0.562 ± 0.012 | 0.673 ± 0.007 | 6.67 × 10−2 | 5.03 × 10−2 | 170.77 |

| CTSK | 1 | 150780799 | 0.363 ± 0.009 | 0.204 ± 0.013 | 0.396 ± 0.01 | 6.67 × 10−2 | 5.17 × 10−2 | 120.75 |

| RUNX3 | 1 | 25257550 | 0.112 ± 0.006 | 0.035 ± 0.007 | 0.109 ± 0.007 | 6.67 × 10−2 | 5.17 × 10−2 | 96.10 |

| RUNX3 | 1 | 25277242 | 0.973 ± 0.003 | 0.927 ± 0.001 | 0.984 ± 0.002 | 6.67 × 10−2 | 5.17 × 10−2 | 123.91 |

| Top 10 CpGs in cord blood | ||||||||

| HIF1A-AS2 | 14 | 62217871 | 0 ± 0 | 0.096 ± 0.007 | 0 ± 0 | 8.76 × 10−7 | 1.01 × 10−6 | 100.00 |

| SOD1 | 21 | 33031886 | 0 ± 0 | 0.058 ± 0.003 | 0 ± 0 | 2.02 × 10−6 | 1.01 × 10−6 | 100.00 |

| LIF | 22 | 30642901 | 0 ± 0 | 0.045 ± 0.002 | 0 ± 0 | 2.49 × 10−4 | 1.22 × 10−4 | 100.00 |

| TVP23B | 17 | 18684432 | 0 ± 0 | 0.047 ± 0.004 | 0.004 ± 0.001 | 3.34 × 10−3 | 1.28 × 10−2 | 91.49 |

| CNTNAP2 | 7 | 145814109 | 0.038 ± 0.003 | 0.002 ± 0.001 | 0.017 ± 0.001 | 3.34 × 10−3 | 4.50 × 10−2 | 41.67 |

| MAOB | X | 43741933 | 0.732 ± 0.004 | 0.474 ± 0.01 | 0.706 ± 0.009 | 3.34 × 10−3 | 8.18 × 10−3 | 89.92 |

| CTNNA2 | 2 | 80529735 | 0 ± 0 | 0.037 ± 0.001 | 0.006 ± 0.001 | 5.12 × 10−3 | 2.93 × 10−2 | 83.78 |

| CTNNA2 | 2 | 80530146 | 0.048 ± 0.002 | 0.006 ± 0.001 | 0.049 ± 0.004 | 5.12 × 10−3 | 1.02 × 10−2 | 102.38 |

| COL11A2 | 6 | 33116173 | 0.065 ± 0.004 | 0.014 ± 0.004 | 0.047 ± 0.004 | 8.42 × 10−3 | 2.93 × 10−2 | 64.71 |

| UBE3C | 7 | 156913122 | 0.98 ± 0.003 | 0.882 ± 0.006 | 0.968 ± 0.003 | 8.42 × 10−3 | 2.83 × 10−2 | 87.76 |

| Top 10 CpGs in buccal epithelium | ||||||||

| TTC7B | 14 | 91121520 | 0.234 ± 0.016 | 0 ± 0 | 0.231 ± 0.032 | 1.46 × 10−2 | 1.51 × 10−2 | 98.72 |

| ATP10A | 15 | 25955129 | 0.926 ± 0.011 | 0.763 ± 0.007 | 0.936 ± 0.005 | 2.83 × 10−2 | 1.23 × 10−2 | 106.13 |

| LOC1019280 | 1 | 153518418 | 0.303 ± 0.014 | 0.026 ± 0.006 | 0.296 ± 0.013 | 3.19 × 10−2 | 2.07 × 10−2 | 97.47 |

| CATIP | 2 | 219232376 | 0.058 ± 0.008 | 0 ± 0 | 0.053 ± 0.004 | 3.19 × 10−2 | 1.23 × 10−2 | 91.38 |

| DLGAP2 | 8 | 1501244 | 0.54 ± 0.02 | 0.812 ± 0.011 | 0.647 ± 0.008 | 3.19 × 10−2 | 4.88 × 10−2 | 60.66 |

| IGSF21 | 1 | 18703322 | 0.83 ± 0.012 | 0.956 ± 0.007 | 0.872 ± 0.006 | 3.28 × 10−2 | 4.39 × 10−2 | 66.67 |

| CYP26C1 | 10 | 94829036 | 0.272 ± 0.026 | 0.062 ± 0.007 | 0.355 ± 0.027 | 3.28 × 10−2 | 2.15 × 10−2 | 139.52 |

| CLSTN3 | 12 | 7295553 | 0.948 ± 0.007 | 0.762 ± 0.013 | 0.96 ± 0.004 | 3.28 × 10−2 | 2.15 × 10−2 | 106.45 |

| SERPINA3 | 14 | 95090393 | 0.893 ± 0.006 | 0.757 ± 0.008 | 0.875 ± 0.01 | 3.28 × 10−2 | 2.81 × 10−2 | 86.76 |

| CORO2B | 15 | 68851394 | 0.101 ± 0.011 | 0.021 ± 0.005 | 0.053 ± 0.005 | 3.28 × 10−2 | 3.39 × 10−2 | 40.00 |

Definition of abbreviations: Chr = chromosome; FDR = false discovery rate.

Top CpGs as ranked by FDR-adjusted P value following pairwise t test between nonsmokers and placebo after removing CpGs with significant sex effects.

Percent restored calculated as −(mean V − mean P)/(mean P − mean N) × 100, where N = nonsmoker, P = placebo, and V = vitamin C.

An advantage to targeted bisulfite sequencing is the generation of high-density, single CpG resolution information within a given region, allowing identification of DMRs across contiguous CpGs, which may be more biologically meaningful than methylation rates at individual CpGs. Therefore, we used comb-p (31) to identify DMRs between nonsmokers and placebo-treated smokers (referred to as NP DMRs) and between placebo- and vitamin C–treated smokers (PV DMRs). comb-p scans across spatially related nominal P values to identify significant regions and applies a distance-related correction factor (i.e., P values will be reduced if CpGs nearby are also significant) before applying FDR and multiple-testing correction for each region (described in detail in Reference 31).

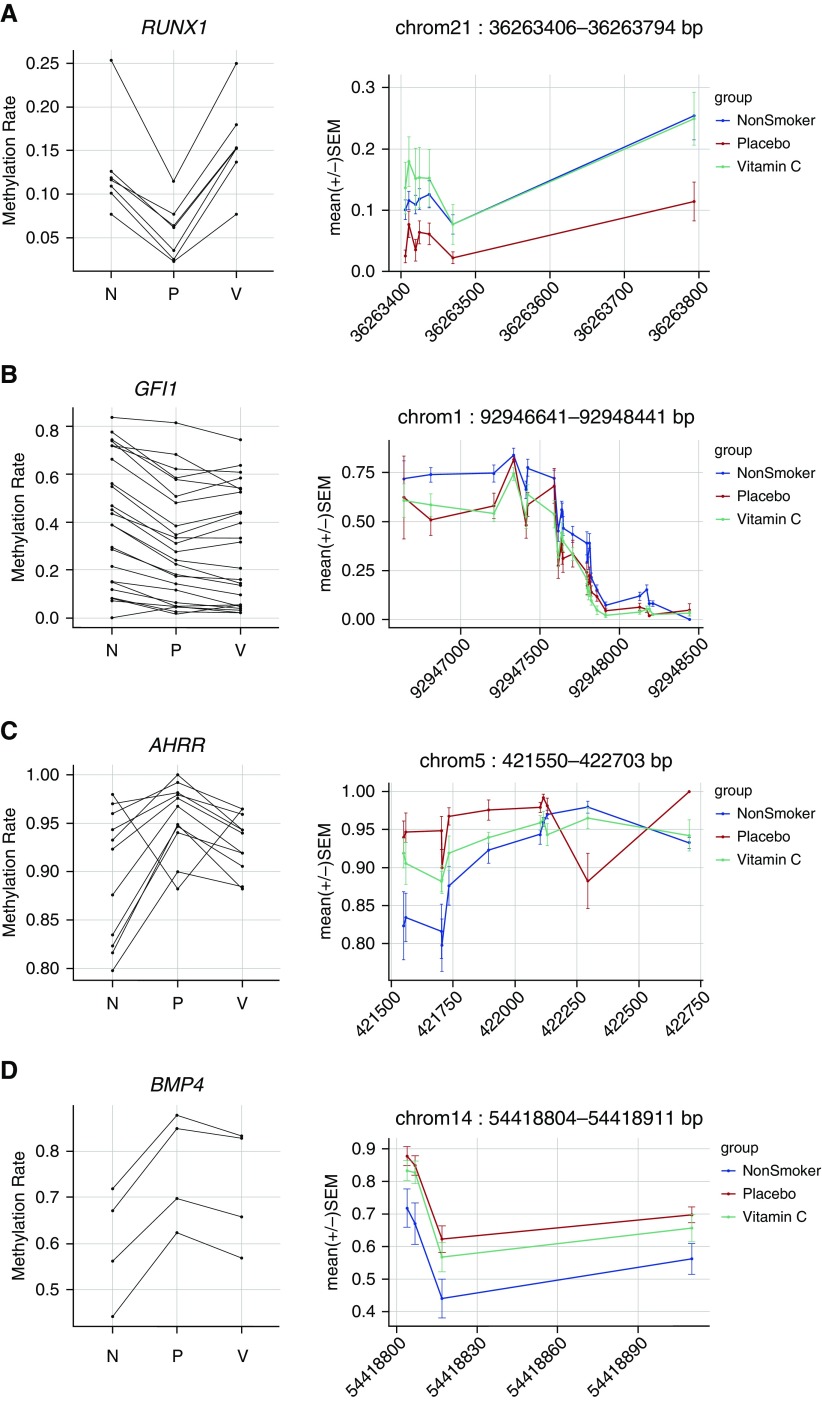

The 10 largest DMRs associated with maternal smoking (NP DMRs) and significantly restored by vitamin C (PV DMRs) per tissue are presented in Table 3, and a complete list is provided in Table E3. In cord blood, we identified 43 significantly restored DMRs (Table E4), with the largest located in RUNX1 (6 CpGs hypomethylated with maternal smoking and restored with vitamin C) (Table 3 and Figure 3A). In placenta, we identified 64 NP DMRs and 108 PV DMRs (Table E5). Among these, 20 DMRs overlapped, and 19 were restored by at least 50% with vitamin C supplementation (Table E3). The largest significantly restored placental DMR mapped within the promoter of HIVEP3 (12 CpGs significant after FDR adjustment by comb-p; Table 3). Last, in buccal epithelium, 32 of 111 DMRs associated with maternal smoking were significantly restored in the vitamin C–supplemented group versus placebo (Table E6). A DMR mapping to SLC18A3, also known as VACHT (vesicular acetylcholine transporter), contained the largest number of CpGs restored by vitamin C in buccal DNA (Table E3).

Table 3.

Top Differentially Methylated Regions Associated with Maternal Smoking and Restored with Vitamin C*

| Mapped Gene | Chr | Chr Start (bp) | Chr End (bp) | Mean P − N† | Mean V − P‡ | % Restored§ | # CpGs FDR |

Šidák P Value|| | Absolute Distance to Nearest CpG Island (bp) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P ≤ 0.05 (comb-p) | P ≤ 0.05 (Pairwise) | |||||||||

| Top 10 DMRs in placenta | ||||||||||

| HIVEP3 | 1 | 42383975 | 42385071 | −0.091 | 0.104 | 114.60 | 12 | 12 | 5.96 × 10−5 | 0 |

| COL4A1 | 13 | 110951171 | 110951346 | −0.177 | 0.147 | 83.09 | 3 | 3 | 1.53 × 10−11 | 7,546 |

| COL4A2 | 13 | 110960293 | 110961359 | 0.016 | −0.010 | 62.28 | 6 | 3 | 2.28 × 10−4 | 0 |

| SLC8A1 | 2 | 40678493 | 40678601 | −0.056 | 0.047 | 83.98 | 2 | 2 | 3.46 × 10−5 | 0 |

| KLHL29 | 2 | 23777199 | 23777252 | −0.094 | 0.095 | 100.92 | 2 | 2 | 1.54 × 10−4 | 7,798 |

| HOXA4 | 7 | 27172606 | 27172632 | 0.118 | −0.110 | 92.90 | 2 | 2 | 2.26 × 10−4 | 1,969 |

| CDCA4 | 14 | 105499940 | 105499982 | 0.093 | −0.089 | 94.87 | 4 | 2 | 2.43 × 10−4 | 0 |

| COL11A2 | 6 | 33147254 | 33147260 | 0.126 | −0.202 | 159.56 | 2 | 2 | 3.22 × 10−4 | 12,732 |

| DLK1 | 14 | 101175833 | 101175950 | −0.134 | 0.192 | 142.69 | 3 | 2 | 5.33 × 10−4 | 0 |

| EPHX2 | 8 | 27348921 | 27348932 | −0.072 | 0.077 | 107.09 | 2 | 2 | 7.68 × 10−4 | 39 |

| Top 10 DMRs in cord blood | ||||||||||

| RUNX1 | 21 | 36263406 | 36263794 | −0.077 | 0.100 | 129.69 | 7 | 6 | 1.21 × 10−5 | 0 |

| HOXA | 7 | 27188195 | 27188771 | −0.107 | 0.117 | 109.32 | 6 | 5 | 4.49 × 10−5 | 504 |

| ZSWIM8 | 10 | 75545173 | 75545829 | 0.024 | −0.026 | 107.38 | 6 | 4 | 1.10 × 10−10 | 0 |

| CYP26A1 | 10 | 94834219 | 94835121 | −0.047 | 0.042 | 88.69 | 6 | 4 | 1.69 × 10−7 | 0 |

| GJD3 | 17 | 38520011 | 38520082 | −0.137 | 0.164 | 119.82 | 4 | 4 | 1.21 × 10−5 | 0 |

| PEG10 | 7 | 94293859 | 94294699 | 0.003 | −0.004 | 152.98 | 4 | 4 | 1.85 × 10−5 | 0 |

| CD14 | 5 | 140012294 | 140013016 | −0.050 | 0.040 | 81.75 | 5 | 4 | 1.59 × 10−4 | 0 |

| FILIP1L | 3 | 99536309 | 99536927 | −0.028 | 0.017 | 59.93 | 5 | 3 | 1.00 × 10−6 | 0 |

| CHAT | 10 | 50821342 | 50821648 | −0.037 | 0.068 | 183.48 | 3 | 3 | 1.49 × 10−6 | 0 |

| NUPL1 | 13 | 25874931 | 25875647 | −0.055 | 0.087 | 158.83 | 6 | 3 | 9.88 × 10−6 | 0 |

| Top 10 DMRs in buccal epithelium | ||||||||||

| SLC18A3 | 10 | 50819293 | 50821023 | −0.041 | 0.045 | 108.99 | 10 | 7 | 6.89 × 10−6 | 0 |

| COL20A1 | 20 | 61959687 | 61960482 | 0.175 | −0.120 | 68.62 | 5 | 5 | 3.47 × 10−5 | 5,280 |

| EPHB2 | 1 | 23110978 | 23111512 | 0.053 | −0.033 | 63.27 | 7 | 5 | 5.43 × 10−5 | 0 |

| TFPT | 19 | 54617892 | 54618399 | −0.060 | 0.061 | 100.67 | 4 | 4 | 7.35 × 10−5 | 254 |

| HIVEP3 | 1 | 42505911 | 42506606 | 0.058 | −0.044 | 75.77 | 6 | 4 | 1.62 × 10−4 | 3,932 |

| CD14 | 5 | 140011903 | 140012736 | −0.024 | 0.034 | 140.87 | 5 | 3 | 1.68 × 10−7 | 0 |

| RXRG | 1 | 165414395 | 165414605 | −0.092 | 0.047 | 50.57 | 3 | 3 | 2.90 × 10−5 | 88,068 |

| DLX6 | 7 | 96636103 | 96636289 | −0.092 | 0.082 | 88.44 | 3 | 3 | 4.04 × 10−5 | 355 |

| HTRA1 | 10 | 124222565 | 124222793 | −0.075 | 0.084 | 112.45 | 3 | 3 | 1.91 × 10−4 | 326 |

| GNG12 | 1 | 68517287 | 68517365 | 0.184 | −0.142 | 77.11 | 4 | 3 | 4.50 × 10−4 | 0 |

Definition of abbreviations: Chr = chromosome; DMRs = differentially methylated regions; FDR = false discovery rate; N = nonsmoker; P = placebo; V = vitamin C.

Top DMRs as ranked by number of pairwise FDR-significant CpGs in DMR between nonsmokers and placebo.

Average difference in methylation between placebo and nonsmokers across all FDR-significant CpGs within DMR.

Average difference in methylation between vitamin C and placebo across all FDR-significant CpGs within DMR.

Percent restored calculated as −(mean V − mean P)/(mean P − mean N) × 100.

The one-step Šidák corrected P value for the DMR region calculated by comb-p (31).

Figure 3.

Select cord blood differentially methylated regions (DMRs) associated with maternal smoking: (A) Runt related transcription factor 1 (RUNX1); (B) growth factor independent 1 transcriptional repressor (GFI1); (C) aryl-hydrocarbon receptor repressor (AHRR); and (D) bone morphogenetic protein 4 (BMP4). DMRs were defined with the comb-p package to identify enriched regions of spatially related pairwise P values between nonsmokers and placebo samples. Plots on the left demonstrate the overall trend in methylation changes across the DMR by showing the mean methylation for nonsmokers (N), placebo (P), and vitamin C (V) at each false discovery rate–significant CpG. On the right, DMRs are plotted by treatment group with spatial orientation to the genome, with base position on the x-axis and methylation (mean ± SEM) on the y-axis.

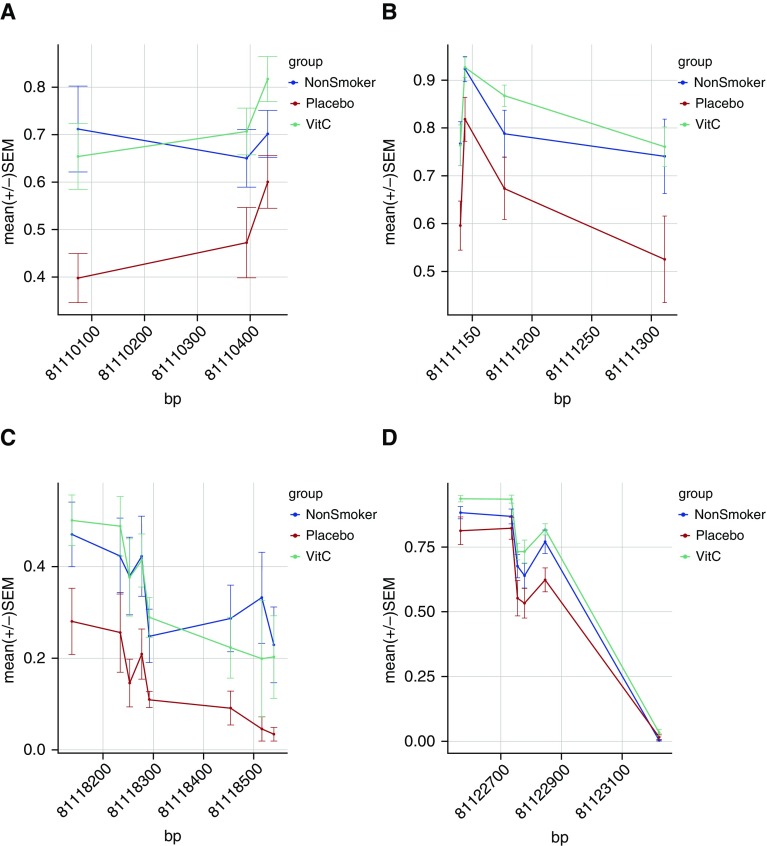

We performed internal technical validation for a subset of 14 cord blood DMRs, using the alternate approach of BSAS. The median depth of coverage for all 321 CpGs covered by BSAS amplicons was 337×. Across 14 DMRs (12 genes) we obtained matching targeted bisulfite sequencing (TBS) and BSAS data for 24 patients and 191 CpGs. Correlation analysis demonstrated strong interpatient concordance between TBS and BSAS methylation (Pearson r2 = 0.931; P < 2.2 × 10−16). The difference in methylation between TBS and BSAS for 95.7% of CpGs was within 1.96 SD of the mean difference, showing strong agreement of the two methods and no systematic bias (Figure E3). Both methods identified a pattern of hypermethylation with maternal smoking at BMP4 and COL5A1, and hypomethylation at PR domain–containing 8 (PRDM8), RUNX1, NOS3, SLC18A3, CHAT, and HOXA7. In both data sets, vitamin C significantly reversed hypomethylation within PRDM8 (Figure 4 and Figure E4) and RUNX1 (Figure 3A and Figure E4).

Figure 4.

PR domain–containing 8 (PRDM8) is hypomethylated across multiple cord blood differentially methylated regions (DMRs) and restored by vitamin C (VitC). PRDM8 CpGs identified by meta-analysis as hypomethylated with maternal smoking overlapped with four regions identified in the NCT00632476 cohort with significantly increased methylation in vitamin C–supplemented smokers relative to placebo-treated smokers. The DMR plots (A–D) show the mean ± SEM methylation for each group in cord blood relative to chromosomal position. (A) chr4_81110074_PRDM8; (B) chr4_81111140_PRDM8; (C) chr4_81118138_PRDM8; (D) chr4_81122567_PRDM8.

We also examined the generalizability of our findings by correlation with results from a meta-analysis of maternal smoking in newborn cord blood. Meta-analysis by the PACE (Pregnancy and Childhood Epigenetics) Consortium of 13 cohorts identified more than 6,000 CpGs with epigenome-wide association with maternal smoking, including 2,965 CpG loci not previously reaching statistical significance by any individual study (34). Our targeted analysis in cord blood covered 323 of the 6,073 CpGs reaching FDR significance in the meta-analysis (see Table S3 in Reference 34). Of these 323 CpGs, 35 mapped within 24 unique DMRs identified in our study and 26 of 35 CpGs followed a consistent direction of change between meta-analysis data and our results with maternal smoking: six hypomethylated CpGs in GFI1 (Figure 3B), five in the aryl-hydrocarbon receptor repressor gene (AHRR) (Figure 3C; one hypo- and four hypermethylated), five hypomethylated in PRDM8 (Figure 4), two hypermethylated in BMP4 (Figure 3D) and ADORA2B, and two hypomethylated in CNTNAP2 (Table E7). The coefficients for sustained smoking and newborn methylation by meta-analysis were significantly correlated with mean difference per DMR between nonsmokers and placebo in our study (Spearman r = 0.5460; P = 0.0002). Among individual CpGs replicated by meta-analysis as significant for association to maternal smoking in cord blood and not in the above-cited DMRs, partial to full reversal of methylation with vitamin C supplementation was identified for CpGs mapping to RUNX3, KLHL29, RARB, PRDM8, AHRR, CNTNAP2, and FERMT3 (Table 4).

Table 4.

Overlap of CpGs Associated with Sustained Maternal Smoking during Pregnancy in Newborn Blood by Published Meta-analysis with Significant Cord Blood CpGs in the NCT00632476 Cohort

| CpG from Meta-analysis | Mapped Gene | Chr | Position (bp) | Meta-analysis Regression Coefficient* |

NCT00632476 Cohort |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo − Nonsmoker | Vitamin C − Placebo | |||||

| cg27058497 | RUNX3 | 1 | 25291546 | −0.011 | −0.078 | 0.017 |

| cg04535902 | GFI1 | 1 | 92947332 | −0.024 | −0.022 | −0.073 |

| cg09935388 | GFI1 | 1 | 92947588 | −0.099 | −0.037 | −0.145 |

| cg25560443 | KLHL29 | 2 | 23726440 | −0.008 | −0.115 | 0.186 |

| cg24230340 | HTRA2 | 2 | 74758080 | −0.009 | 0.001 | −0.073 |

| cg15607292 | RARB | 3 | 25426810 | 0.007 | 0.045 | −0.059 |

| cg27111250 | PRDM8 | 4 | 81111177 | −0.020 | −0.115 | 0.194 |

| cg08606254 | AHRR | 5 | 323969 | 0.025 | 0.021 | −0.128 |

| cg23916896 | AHRR | 5 | 368804 | −0.012 | −0.076 | 0.026 |

| cg22937882 | AHRR | 5 | 405774 | 0.013 | 0.053 | 0.000 |

| cg00976097 | AHRR | 5 | 421733 | 0.012 | 0.091 | −0.049 |

| cg17656608 | LOC100505636 | 5 | 139486020 | 0.008 | −0.065 | 0.008 |

| cg16254309 | CNTNAP2 | 7 | 145814152 | −0.003 | −0.006 | 0.024 |

| cg25949550 | CNTNAP2 | 7 | 145814306 | −0.014 | −0.014 | −0.021 |

| cg11207515 | CNTNAP2 | 7 | 146904205 | −0.023 | −0.029 | −0.074 |

| cg11694510 | IFITM1 | 11 | 313354 | −0.007 | 0.106 | −0.091 |

| cg20160996 | FERMT3 | 11 | 63990575 | 0.002 | 0.028 | −0.078 |

| cg03848267 | STAT6 | 12 | 57506361 | −0.001 | 0.016 | −0.011 |

| cg05923197 | BMP4 | 14 | 54418804 | 0.029 | 0.159 | −0.045 |

| cg20244340 | SLC24A3 | 20 | 19193989 | −0.012 | 0.028 | −0.089 |

| cg17072519 | AIFM3 | 22 | 21322063 | 0.009 | 0.168 | 0.041 |

Definition of abbreviation: Chr = chromosome.

Regression coefficient for CpG association with sustained maternal smoking during pregnancy by meta-analysis of 13 cohorts (34).

Last, we examined whether methylation changes with maternal smoking at specific loci restored by vitamin C treatment were also associated with respiratory outcomes. We calculated the hypergeometric probability of overlap between restored CpGs and CpGs associated with either incidence of wheeze at 1 year of age or TPTEF:TE at birth. A summary of the results is presented in Table E9. In all three tissues, we observed significant enrichment for restored CpGs associated with pulmonary function at birth (TPTEF:TE; Table E10). We also identified significant enrichment for hypomethylated CpGs reversed by vitamin C treatment and associated with wheeze in cord blood. Notably, we identified three or more CpGs in AHRR, RXRA, PRDM8, DLGAP2, and TBC1D16, which were hypomethylated with maternal smoking and hypomethylated with wheeze, but for which methylation was restored on treatment with vitamin C (full list available in Table E11).

Discussion

It is now well established that maternal smoking during pregnancy causes lifelong decreases in pulmonary function in offspring and increased risk of asthma (36, 37). Forced expiratory flows in the offspring of smokers are decreased at birth (38), and similar decreases can be measured in high school students (39) and even adults. The mechanism by which in utero smoke exposure causes lifelong changes in pulmonary function is unknown, but may involve epigenetics. Consistent with this hypothesis, multiple studies have observed alterations in DNA methylation after in utero exposure to maternal smoking (8–10, 13–15, 18, 34, 40).

In agreement with previous reports, our study identified significant changes in DNA methylation associated with maternal smoking in cord blood and placenta collected at birth, and in buccal epithelium collected between the ages of 3 and 6 years. Maternal supplementation with vitamin C during pregnancy was associated with a reduction or reversal in smoking-related changes across the genome and across tissues at both hypo- and hypermethylated loci (Figure 2). This is in line with a study that found that topical vitamin C restored methylation changes at 88% of hypermethylated regions and 76% of hypomethylated regions in mouse skin treated chronically with a low concentration of benzo[a]pyrene, a common carcinogen found in cigarette smoke (41). The direction of change in DNA methylation in response to environmental stressors, such as maternal smoking, is complex and varies according to gene function and proximity to regulatory elements such as promoters and CpG islands (42). However, the underlying mechanism(s) by which maternal smoking/vitamin C affect gene-specific hypo- and hypermethylation have yet to be determined.

RUNX transcription factors play an essential role in lung development, embryonic development, hematopoiesis, and immune responses (43–45). RUNX1 polymorphisms are associated with airway hyperresponsiveness in pediatric asthma, and expression of RUNX1 is elevated in embryonic human lung after intrauterine smoke exposure (20). Maternal smoking has been previously associated with hypermethylation of RUNX3 and RUNX1 in placenta and cord blood, respectively (9, 13), and with hypomethylation in RUNX3 at cg27058497 in cord blood (34) (Table 4). In cord blood, we observed RUNX1 hypomethylation within the proximal promoter that was restored to the level of nonsmokers with vitamin C supplementation, a result we further validated by BSAS (Figure E4). In placenta, we identified two RUNX3 CpGs among the top 10 CpGs modified with maternal smoking (Table 2) in addition to a hypomethylated CpG 16 bp away from cg24019564 (13). Notably, hypomethylation of RUNX3 in placenta was restored by vitamin C supplementation, and methylation of RUNX3 in buccal epithelium was also significantly associated with pulmonary function at birth (Table E10).

We observed widespread hypomethylation of PRDM8 in cord blood across five DMRs restored with vitamin C treatment to the level of nonsmokers (Table E4 and Figure 4), an effect also confirmed by BSAS (Figure E4). PRDM8 encodes a histone methyltransferase belonging to the PR domain zinc finger protein family, whose members have been implicated in malignant transformation of multiple tissues, including lung, through epigenetic silencing mediated by DNA hypermethylation (46). In additional support of our findings, 18 CpGs mapping to PRDM8 were shown to be significantly hypomethylated with maternal smoking by the meta-analysis (Table E7) (34). Most interestingly, three PRDM8 CpGs were hypomethylated in cord blood and associated with wheeze at 1 year of age (Table E11).

The CpG most frequently associated with maternal smoking is cg0557921, located in AHRR (8–10, 14, 15, 18). AHRR has been described as a biomarker for exposure to cigarette smoke (47), and its hypomethylation is also associated with smoking pack-years in both blood and buccal cells of adult smokers (48). We observed hypomethylation at cg05575921 in our cohort that did not reach statistical significance. However, we identified a DMR 61 bp upstream of cg05575921 that was significantly hypomethylated with maternal smoking but not significantly changed with vitamin C (Table E4). Methylation in cord blood at four AHRR CpGs outside this DMR were, however, restored by vitamin C by greater than 69% and were also associated with wheeze outcome at 1 year of age (Table E11).

We observed relatively little overlap in DNA methylation patterns between tissues, which is consistent with previous studies of genome-wide differential DNA methylation (9). For example, Novakovic and colleagues identified persistent hypomethylation with exposure to maternal smoking over a region containing cg05575921 in AHRR out to 18 months of age in peripheral blood, but no changes in buccal epithelium or placenta (15). Clearly, DNA methylation is highly dynamic in response to environmental insults, in combination with temporal changes that occur during normal differentiation, development, and aging (42).

To further validate our findings we examined replication of our results on the basis of a more recently published meta-analysis (34). Of note, the largest DMR in our data set mapped to GFI1 (24 hypomethylated CpGs; Table E7), consistent with the meta-analysis and previously associated with maternal plasma cotinine and fetal birth weight (9, 18). Two hypermethylated BMP4 DMRs in our data set partially overlapped six hypermethylated CpGs in BMP4 identified by Joubert and colleagues (34). Bone morphogenetic proteins such as that encoded by BMP4 play a crucial role in lung development, and chronic exposure to cigarette smoke increases expression of BMP4 in the lungs of Sprague-Dawley rats (49).

Limitations of our study include lack of a cell-type correction model, and therefore it is possible that the observed DNA methylation changes are the result of a shift in the proportions of cell populations (50). However, the top methylation changes identified in other studies of maternal smoking in utero are preserved after cell type correction (9, 14). Observed increases in methylation rates among smokers (hypermethylation) could also be indicative of increased 5hmC, which is indistinguishable from 5mC with traditional bisulfite sequencing platforms. For buccal DNA methylation we have not adjusted for postnatal exposure because of the small sample size. However, it is highly likely that these children continue to be exposed to parental smoking postnatally, given that the women enrolled in this study were unable to quit during pregnancy even with cessation counseling as part of each study visit. Surprisingly, the reversal pattern in DNA methylation levels with vitamin C supplementation persisted in buccal epithelium collected 3–6 years after birth (and the end of vitamin C supplementation), despite likely continued postnatal smoke exposure (Figure 2).

We and others have observed sex-specific DNA methylation differences in response to maternal smoking, and therefore stratified analysis by sex in a larger cohort may be informative of sex-specific susceptibility to respiratory phenotypes. Samples were collected opportunistically as available and therefore, as described in Methods, we did not have matching tissues for all samples studied. Because of this, statistical tests were performed in the various tissues separately. Replication with a larger sample size and careful consideration of confounders and covariates are necessary and are currently in progress as part of an ongoing clinical trial, “Vitamin C to Decrease Effects of Smoking in Pregnancy on Infant Lung Function” (NCT01723696).

Last, we focused our initial methylation analysis of this clinical trial cohort on an a priori set of genes. Therefore, we were able to identify enrichment of biological pathways only within these targeted loci. Follow-up studies should include both longitudinal and genome-wide analysis of the methylome to improve our understanding of the molecular targets and potential mechanisms underlying the observed effects of vitamin C on the smoking methylome in association with lung function. If replicated, these findings could have significant implications for the respiratory health of hundreds of thousands of babies born each year who are exposed in utero to smoking due to the highly addictive nature of nicotine (2).

Footnotes

Supported by National Institutes of Health grants F32HL123246, HL080231 (with an administrative supplement from the Office of Dietary Supplements), HL105447, UL1 RR024140, UG3 OD023288, and P51 OD011092.

Author Contributions: Substantial contributions to conception, design, acquisition, analysis, and preparation: L.E.S.-K., C.T.M., and E.R.S.; substantial contributions to design and analysis: B.F., J.B., L.G., B.S.P., and C.D.M.; substantial contributions to acquisition and analysis: B.H.V. and K.F.M.

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of contents at www.atsjournals.org.

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.201610-2141OC on April 19, 2017

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Alshaarawy O, Anthony JC. Month-wise estimates of tobacco smoking during pregnancy for the United States, 2002–2009. Matern Child Health J. 2015;19:1010–1015. doi: 10.1007/s10995-014-1599-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tong VT, Dietz PM, Morrow B, D’Angelo DV, Farr SL, Rockhill KM, England LJ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Trends in smoking before, during, and after pregnancy: Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System, United States, 40 sites, 2000–2010. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2013;62:1–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burke H, Leonardi-Bee J, Hashim A, Pine-Abata H, Chen Y, Cook DG, Britton JR, McKeever TM. Prenatal and passive smoke exposure and incidence of asthma and wheeze: systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2012;129:735–744. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dietz PM, England LJ, Shapiro-Mendoza CK, Tong VT, Farr SL, Callaghan WM. Infant morbidity and mortality attributable to prenatal smoking in the U.S. Am J Prev Med. 2010;39:45–52. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hollams EM, de Klerk NH, Holt PG, Sly PD. Persistent effects of maternal smoking during pregnancy on lung function and asthma in adolescents. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;189:401–407. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201302-0323OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu P. Maternal smoking during pregnancy and its effect on childhood asthma: understanding the puzzle. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186:941–942. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201209-1618ED. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Neuman Å, Hohmann C, Orsini N, Pershagen G, Eller E, Kjaer HF, Gehring U, Granell R, Henderson J, Heinrich J, et al. ENRIECO Consortium. Maternal smoking in pregnancy and asthma in preschool children: a pooled analysis of eight birth cohorts. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186:1037–1043. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201203-0501OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nielsen CH, Larsen A, Nielsen AL. DNA methylation alterations in response to prenatal exposure of maternal cigarette smoking: a persistent epigenetic impact on health from maternal lifestyle? Arch Toxicol. 2016;90:231–245. doi: 10.1007/s00204-014-1426-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Joubert BR, Håberg SE, Nilsen RM, Wang X, Vollset SE, Murphy SK, Huang Z, Hoyo C, Midttun Ø, Cupul-Uicab LA, et al. 450K epigenome-wide scan identifies differential DNA methylation in newborns related to maternal smoking during pregnancy. Environ Health Perspect. 2012;120:1425–1431. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1205412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee KW, Richmond R, Hu P, French L, Shin J, Bourdon C, Reischl E, Waldenberger M, Zeilinger S, Gaunt T, et al. Prenatal exposure to maternal cigarette smoking and DNA methylation: epigenome-wide association in a discovery sample of adolescents and replication in an independent cohort at birth through 17 years of age. Environ Health Perspect. 2015;123:193–199. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1408614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chhabra D, Sharma S, Kho AT, Gaedigk R, Vyhlidal CA, Leeder JS, Morrow J, Carey VJ, Weiss ST, Tantisira KG, et al. Fetal lung and placental methylation is associated with in utero nicotine exposure. Epigenetics. 2014;9:1473–1484. doi: 10.4161/15592294.2014.971593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Suter M, Ma J, Harris A, Patterson L, Brown KA, Shope C, Showalter L, Abramovici A, Aagaard-Tillery KM. Maternal tobacco use modestly alters correlated epigenome-wide placental DNA methylation and gene expression. Epigenetics. 2011;6:1284–1294. doi: 10.4161/epi.6.11.17819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maccani JZ, Koestler DC, Houseman EA, Marsit CJ, Kelsey KT. Placental DNA methylation alterations associated with maternal tobacco smoking at the RUNX3 gene are also associated with gestational age. Epigenomics. 2013;5:619–630. doi: 10.2217/epi.13.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Richmond RC, Simpkin AJ, Woodward G, Gaunt TR, Lyttleton O, McArdle WL, Ring SM, Smith AD, Timpson NJ, Tilling K, et al. Prenatal exposure to maternal smoking and offspring DNA methylation across the lifecourse: findings from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC) Hum Mol Genet. 2015;24:2201–2217. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddu739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Novakovic B, Ryan J, Pereira N, Boughton B, Craig JM, Saffery R. Postnatal stability, tissue, and time specific effects of AHRR methylation change in response to maternal smoking in pregnancy. Epigenetics. 2014;9:377–386. doi: 10.4161/epi.27248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Breton CV, Byun HM, Wang X, Salam MT, Siegmund K, Gilliland FD. DNA methylation in the arginase–nitric oxide synthase pathway is associated with exhaled nitric oxide in children with asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184:191–197. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201012-2029OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morales E, Bustamante M, Vilahur N, Escaramis G, Montfort M, de Cid R, Garcia-Esteban R, Torrent M, Estivill X, Grimalt JO, et al. DNA hypomethylation at ALOX12 is associated with persistent wheezing in childhood. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185:937–943. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201105-0870OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Küpers LK, Xu X, Jankipersadsing SA, Vaez A, la Bastide-van Gemert S, Scholtens S, Nolte IM, Richmond RC, Relton CL, Felix JF, et al. DNA methylation mediates the effect of maternal smoking during pregnancy on birthweight of the offspring. Int J Epidemiol. 2015;44:1224–1237. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyv048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bouwland-Both MI, van Mil NH, Tolhoek CP, Stolk L, Eilers PH, Verbiest MM, Heijmans BT, Uitterlinden AG, Hofman A, van Ijzendoorn MH, et al. Prenatal parental tobacco smoking, gene specific DNA methylation, and newborns size: the Generation R Study. Clin Epigenetics. 2015;7:83. doi: 10.1186/s13148-015-0115-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haley KJ, Lasky-Su J, Manoli SE, Smith LA, Shahsafaei A, Weiss ST, Tantisira K. RUNX transcription factors: association with pediatric asthma and modulated by maternal smoking. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2011;301:L693–L701. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00348.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schleicher RL, Carroll MD, Ford ES, Lacher DA. Serum vitamin C and the prevalence of vitamin C deficiency in the United States: 2003–2004 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;90:1252–1263. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.27016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Madruga de Oliveira A, Rondó PH, Barros SB. Concentrations of ascorbic acid in the plasma of pregnant smokers and nonsmokers and their newborns. Int J Vitam Nutr Res. 2004;74:193–198. doi: 10.1024/0300-9831.74.3.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Camarena V, Wang G. The epigenetic role of vitamin C in health and disease. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2016;73:1645–1658. doi: 10.1007/s00018-016-2145-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McEvoy CT, Schilling D, Clay N, Jackson K, Go MD, Spitale P, Bunten C, Leiva M, Gonzales D, Hollister-Smith J, et al. Vitamin C supplementation for pregnant smoking women and pulmonary function in their newborn infants: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;311:2074–2082. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.5217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shorey-Kendrick LE, McEvoy CT, Wilhelm LJ, Vuylsteke BH, Milner KF, Spindel ER. Smoking-associated changes in DNA methylation are widely abolished by vitamin C supplementation to pregnant smokers [abstract] Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193:A2937. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shorey-Kendrick LE, McEvoy CT, Wilhelm LJ, Milner KF, Selleck-Smith CM, Spindel ER. Vitamin C supplementation to pregnant smokers restores many DNA methylation changes in placenta in parallel with preventing alterations in offspring pulmonary function [abstract] Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;191:A5459. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Breton CV, Byun HM, Wenten M, Pan F, Yang A, Gilliland FD. Prenatal tobacco smoke exposure affects global and gene-specific DNA methylation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180:462–467. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200901-0135OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bruchova H, Vasikova A, Merkerova M, Milcova A, Topinka J, Balascak I, Pastorkova A, Sram RJ, Brdicka R. Effect of maternal tobacco smoke exposure on the placental transcriptome. Placenta. 2010;31:186–191. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2009.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huuskonen P, Storvik M, Reinisalo M, Honkakoski P, Rysä J, Hakkola J, Pasanen M. Microarray analysis of the global alterations in the gene expression in the placentas from cigarette-smoking mothers. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2008;83:542–550. doi: 10.1038/sj.clpt.6100376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang W, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:44–57. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pedersen BS, Schwartz DA, Yang IV, Kechris KJ. Comb-p: software for combining, analyzing, grouping and correcting spatially correlated P-values. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:2986–2988. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Quinlan AR, Hall IM. BEDTools: a flexible suite of utilities for comparing genomic features. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:841–842. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kent WJ, Sugnet CW, Furey TS, Roskin KM, Pringle TH, Zahler AM, Haussler D. The human genome browser at UCSC Genome Res 2002 Jun12996–1006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Joubert BR, Felix JF, Yousefi P, Bakulski KM, Just AC, Breton C, Reese SE, Markunas CA, Richmond RC, Xu CJ, et al. DNA methylation in newborns and maternal smoking in pregnancy: genome-wide consortium meta-analysis. Am J Hum Genet. 2016;98:680–696. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2016.02.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Johnson WE, Li C, Rabinovic A. Adjusting batch effects in microarray expression data using empirical Bayes methods. Biostatistics. 2007;8:118–127. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/kxj037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bjerg A, Hedman L, Perzanowski M, Lundbäck B, Rönmark E. A strong synergism of low birth weight and prenatal smoking on asthma in schoolchildren. Pediatrics. 2011;127:e905–e912. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-2850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zlotkowska R, Zejda JE. Fetal and postnatal exposure to tobacco smoke and respiratory health in children. Eur J Epidemiol. 2005;20:719–727. doi: 10.1007/s10654-005-0033-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hoo AF, Henschen M, Dezateux C, Costeloe K, Stocks J. Respiratory function among preterm infants whose mothers smoked during pregnancy. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;158:700–705. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.158.3.9711057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gilliland FD, Berhane K, McConnell R, Gauderman WJ, Vora H, Rappaport EB, Avol E, Peters JM. Maternal smoking during pregnancy, environmental tobacco smoke exposure and childhood lung function. Thorax. 2000;55:271–276. doi: 10.1136/thorax.55.4.271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rotroff DM, Joubert BR, Marvel SW, Håberg SE, Wu MC, Nilsen RM, Ueland PM, Nystad W, London SJ, Motsinger-Reif A. Maternal smoking impacts key biological pathways in newborns through epigenetic modification in utero. BMC Genomics. 2016;17:976. doi: 10.1186/s12864-016-3310-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jiang CL, He SW, Zhang YD, Duan HX, Huang T, Huang YC, Li GF, Wang P, Ma LJ, Zhou GB, et al. Air pollution and DNA methylation alterations in lung cancer: a systematic and comparative study. Oncotarget. 2017;8:1369–1391. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.13622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Christensen BC, Houseman EA, Marsit CJ, Zheng S, Wrensch MR, Wiemels JL, Nelson HH, Karagas MR, Padbury JF, Bueno R, et al. Aging and environmental exposures alter tissue-specific DNA methylation dependent upon CpG island context. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000602. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.de Bruijn M, Dzierzak E. Runx transcription factors in the development and function of the definitive hematopoietic system. Blood. 2017;129:2061–2069. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-12-689109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Voon DC, Hor YT, Ito Y. The RUNX complex: reaching beyond haematopoiesis into immunity. Immunology. 2015;146:523–536. doi: 10.1111/imm.12535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee JM, Kwon HJ, Lai WF, Jung HS. Requirement of Runx3 in pulmonary vasculogenesis. Cell Tissue Res. 2014;356:445–449. doi: 10.1007/s00441-014-1816-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tan SX, Hu RC, Liu JJ, Tan YL, Liu WE. Methylation of PRDM2, PRDM5 and PRDM16 genes in lung cancer cells. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7:2305–2311. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Philibert RA, Beach SR, Brody GH. Demethylation of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor repressor as a biomarker for nascent smokers. Epigenetics. 2012;7:1331–1338. doi: 10.4161/epi.22520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Teschendorff AE, Yang Z, Wong A, Pipinikas CP, Jiao Y, Jones A, Anjum S, Hardy R, Salvesen HB, Thirlwell C, et al. Correlation of smoking-associated DNA methylation changes in buccal cells with DNA methylation changes in epithelial cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1:476–485. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhao L, Wang J, Wang L, Liang YT, Chen YQ, Lu WJ, Zhou WL. Remodeling of rat pulmonary artery induced by chronic smoking exposure. J Thorac Dis. 2014;6:818–828. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2014.03.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Houseman EA, Accomando WP, Koestler DC, Christensen BC, Marsit CJ, Nelson HH, Wiencke JK, Kelsey KT. DNA methylation arrays as surrogate measures of cell mixture distribution. BMC Bioinformatics. 2012;13:86. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-13-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]