Abstract

Natural gas (methane, CH4) is widely considered as a promising energy carrier for mobile applications. Maximizing the storage capacity is the primary goal for the design of future storage media. Here we report the CH4 storage properties in a family of isostructural (3,24)-connected porous materials, MFM-112a, MFM-115a, and MFM-132a, with different linker backbone functionalization. Both MFM-112a and MFM-115a show excellent CH4 uptakes of 236 and 256 cm3 (STP) cm–3 (v/v) at 80 bar and room temperature, respectively. Significantly, MFM-115a displays an exceptionally high deliverable CH4 capacity of 208 v/v between 5 and 80 bar at room temperature, making it among the best performing metal–organic frameworks for CH4 storage. We also synthesized the partially deuterated versions of the above materials and applied solid-state 2H NMR spectroscopy to show that these three frameworks contain molecular rotors that exhibit motion in fast, medium, and slow regimes, respectively. In situ neutron powder diffraction studies on the binding sites for CD4 within MFM-132a and MFM-115a reveal that the primary binding site is located within the small pocket enclosed by the [(Cu2)3(isophthalate)3] window and three anthracene/phenyl panels. The open Cu(II) sites are the secondary/tertiary adsorption sites in these structures. Thus, we obtained direct experimental evidence showing that a tight cavity can generate a stronger binding affinity to gas molecules than open metal sites. Solid-state 2H NMR spectroscopy and neutron diffraction studies reveal that it is the combination of optimal molecular dynamics, pore geometry and size, and favorable binding sites that leads to the exceptional and different methane uptakes in these materials.

Introduction

Natural gas (comprised primarily of 95% methane, CH4) has become an important fuel for mobile applications owing to its potentially reduced carbon emission at the point of use in comparison to gasoline-based hydrocarbon fuels.1,2 Another key advantage of utilizing CH4 as fuel lies in its abundant reserves and the widespread and mature infrastructure for its cost-viable recovery.3 However, the extensive implementation of CH4 as transportation fuel is restricted because of the underdevelopment of safe, efficient, and high-capacity storage systems. Therefore, challenges exist in the development of practical CH4 storage materials that can outperform the state-of-the-art technologies mainly based upon liquefaction in cryogenic tanks or compression in heavy-walled pressure vessels.4

Porous metal–organic framework (MOF) materials have attracted increasing research interest because of their potential applications in gas storage,5−8 separation,9,10 carbon capture,11 small-molecule sensing,12 and heterogeneous catalysis,13 among others.14,15 Constructed by bridging metal ions/clusters with organic ligands, crystalline MOFs have the unique advantage of extensive structural diversity and tunability.16,17 The crystalline nature of MOFs allows advanced crystallographic analysis of the structural change upon external stimuli and/or the host–guest interactions.18 These structural insights at a molecular level can effectively direct the design of future MOFs showing optimized capability of binding guest molecules for enhanced storage/separation performance. In the context of CH4 storage, the primary target for materials design is to maximize the adsorption capacity and more importantly the deliverable capacity with the aim of approaching the DOE target for on-board CH4 storage.19

The synthesis of MOFs based on Cu(II) with isophthalate ligands20 has been proved to be an effective strategy to achieve high CH4 storage capacity.21 A family of robust (3,24)-connected networks with ultrahigh porosity incorporating hexacarboxylate ligands and [Cu2(O2CR)4] paddlewheels has been reported to show exceptional gas adsorption properties.21−25 Open metal sites can provide strong affinity for CH4, as evidenced by previous structural studies on several MOFs such as Cu3(BTC)2 (BTC3– = benzene-1,3,5-tricarboxylate)26−28 and Mg-MOF-74.29 However, open metal sites often saturate rapidly upon guest uptake and thus have a limited role in defining the maximum gas capacity. This is particularly the case at high pressure, where adsorbate–adsorbate interactions dominate the uptake process. However, the effects of optimizing the configuration and molecular dynamics of the ligand core have been largely overlooked for the enhancement of overall CH4 adsorption capacity.

We report here the CH4 adsorption properties in a series of (3,24)-connected MOFs, MFM-112,22 MFM-115,24b and MFM-132 (MFM = Manchester Framework Material replacing the NOTT specification), incorporating a central phenyl ring, a nitrogen center at the core of the hexacarboxylate, and anthracene functionalization, respectively. Thus, variation of the central part of the hexacarboxylate ligands where three isophthalate units are covalently connected in a coplanar fashion results in structures with different functionalities and pore geometries. Significantly, desolvated MFM-115a shows an exceptionally high deliverable CH4 capacity of 208 cm3 (STP) cm–3 (v/v) between 5 and 80 bar at room temperature, making it among the best performing porous materials for CH4 storage. In most porous MOF structures, the organic linker contains mobile aromatic fragments that can rotate around a certain axis within the void. This rotation creates dynamic disorder in the framework, which effectively changes the inner geometry of the pore, as well as the positions of possible adsorption sites associated with the fragment. We report also the molecular dynamics of the rotationally dynamic aromatic rings in the partially deuterated isostructural series (desolvated MFM-112a-d12, MFM-115a-d12, and MFM-132a-d24) as revealed by solid-state 2H NMR spectroscopy. We confirm how these dynamics can be controlled in a simple manner by rational synthesis. In addition, neutron diffraction studies on CD4-loaded MFM-132a and MFM-115a afford precise details of CD4 binding in these two structures at a molecular level. In MFM-132a, a tight pocket of 6 Å diameter is formed by the anthracene rings close to the [(Cu2)3(isophthalate)3] window, and this shows an affinity for CD4 that surprisingly is stronger than at the open Cu(II) sites. Interestingly, CD4 in MFM-115a shows optimum packing efficiency within this porous structure.

Results and Discussion

Structures and Porosity of MFM-112, MFM-115, and MFM-132

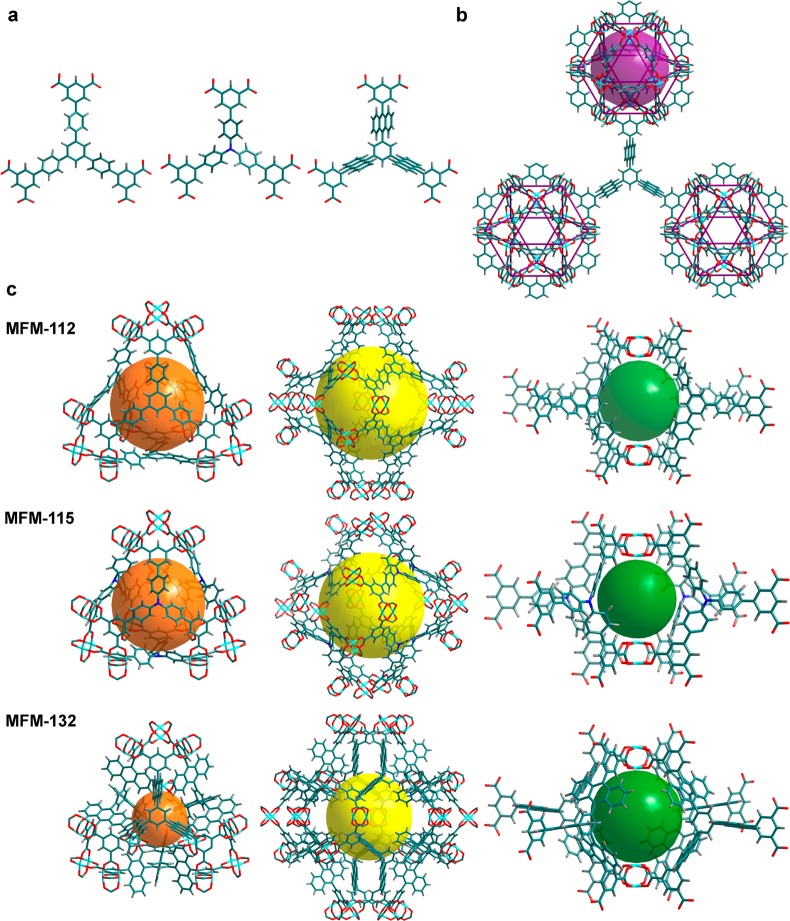

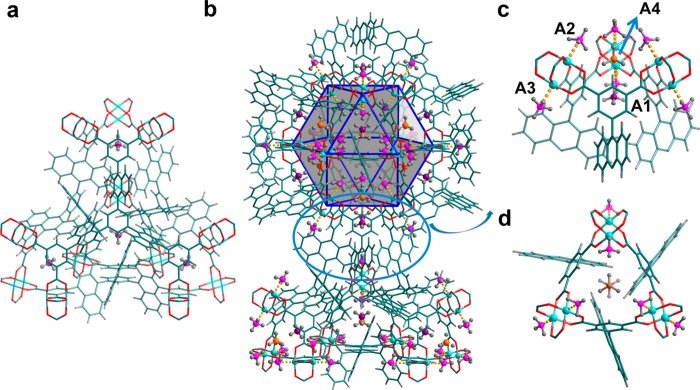

The three isostructural MOFs all have (3,24)-connected networks, where [Cu2(O2CR)4] paddlewheels are bridged by the isophthalate units from the hexacarboxylate ligands to form cuboctahedra, which are further connected by the central triangular ligand core (Figure 1). In the structure of MFM-132, a [Cu24(isophthalate)24] cuboctahedron (cage A), constructed from 12 {Cu2} paddlewheels and 24 isophthalates (from 24 independent BTAT6– units) [H6BTAT = 5,5′,5″-(benzene-1,3,5-triyltris(anthracene-10,9-diyl))triisophthalic acid], is heavily shielded by 24 anthracene units from different ligands. Upon removal of coordinated water molecules from the axial sites of the metal ions, the interior accessible void in cage A is ∼1.3 nm in diameter. This cage possesses a highly hydrophobic outer shell (anthracene panels) and an internal hydrophilic cavity [12 open Cu(II) sites in its activated phase] and is anticipated to show highly confined host–guest binding properties. Cage B, a truncated tetrahedron comprising four ligands and four [Cu6(isophthalate)3] triangular windows, with 12 anthracene units protruding into the central void, shows a diminished cage size of 6.5 Å (defined as the diameter of the largest sphere that can be fitted into the cavity taking into account the van der Waals radii of surface atoms). This is much smaller than that of the phenylene-functionalized MFM-112 (cage B ≈ 14 Å in diameter). The truncated octahedral cage C is constructed from eight BTAT6– units and six [Cu8(isophthalate)4] square windows and possesses an accessible void 13 Å in diameter despite having 24 anthracene rings protruding into the center of the cavity. The void between the two closest cuboctahera or the fused cages B and C generates the fourth cage, cage D, which is composed of eight anthracene panels from four ligands and two [Cu2(O2CR)4] paddlewheels with an enclosed spherical cavity of 10 Å in diameter and small apertures of 5 Å × 5 Å. Overall, the anthracene functionalization in MFM-132 yields a rich combination of metal–organic coordination cages of different geometry, size, and pore surface chemistry, thus representing a unique platform to study the host–guest binding in porous materials.

Figure 1.

View of the chemical structures of the ligands and crystal structures of the isostructural MFMs series. (a) The three hexacarboxylate ligands for the construction of MFM-112, MFM-115, and MFM-132, respectively. (b) In the (3,24)-connected network, the linker with C3-symmetry is connected to three cuboctahedra (cage A). The MFM-132 case is shown as an example. (c) The different cage structures (cage B, C, and D) in the above three frameworks. The colors for the spheres that fit into the void of different types of cages are magenta for cage A, orange for cage B, yellow for cage C, and green for cage D.

The three MOFs show similar thermal stability with framework decomposition at 350 °C, as confirmed by thermogravimetric analyses (Figure S9).22,24b The desolvated samples of MFM-112a, MFM-115a, and MFM-132a can be readily prepared by removing the free and coordinated solvent molecules from the pore at 100 °C under dynamic vacuum. The desolvated materials show retention of the framework structure as confirmed by PXRD analysis. The solvent-accessible void calculated using PLATON/VOID30 for MFM-132a is 63%, lower than that of MFM-112a (75%) and MFM-115a (72%) owing to the anthracene functionalization. Unsurprisingly, MFM-132a shows a lower Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) surface area (SBET = 2466 m2 g–1) and total pore volume (Vp = 1.06 cm3 g–1) than that of MFM-112a (SBET = 3800 m2 g–1; Vp = 1.62 cm3 g–1) and MFM-115a (SBET = 3394 m2 g–1; Vp = 1.38 cm3 g–1). The pore size distribution calculated using the NLDFT method indicates a homogeneous distribution of pore size of ∼12 Å in MFM-132a. MFM-112a and MFM-115a show a hierarchical pore system comprising different-sized pores, with the largest pore size being 17 and 20 Å, respectively. Because of the presence of bulky aromatic groups, MFM-132a has a calculated crystal density of 0.650 g cm–3, higher than that of MFM-112a (0.503 g cm–3) and MFM-115a (0.611 g cm–3).20 Throughout this and other reports, it is common practice for the volumetric gas uptake to be derived from the bulk material density based upon the single-crystal structure, but it should be noted that when the efficiency of packing and the polycrystalline nature of the bulk material are considered, the uptakes will be reduced accordingly; this will be subject to the different compressibility and mechanical stability of different materials.

CH4 Storage

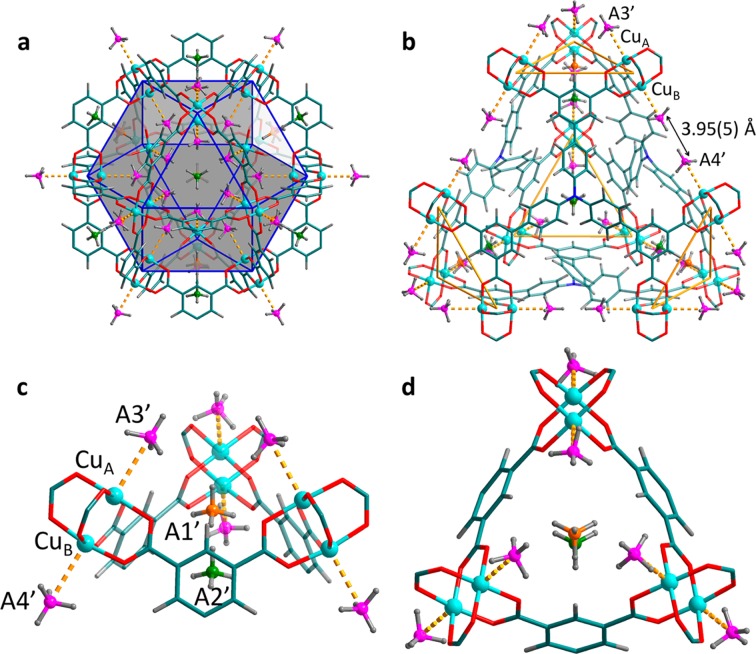

Adsorption measurements were performed using a gravimetric adsorption analyzer for the desolvated materials at 298 K over the pressure range of 0–90 bar (Figures 2, S11). The excess CH4 uptakes in these materials increase with increasing pressure until reaching the maximum in a high-pressure region (80–90 bar). The total CH4 uptake was calculated from the excess uptake by including the amount of compressed CH4 in the pore using the pore volume as determined from N2 isotherms. Although MFM-112a shows higher gravimetric CH4 uptakes than MFM-115a in the high-pressure range (30–90 bar), the volumetric uptakes show the opposite trend due to the higher crystal density of MFM-115a. At 35 bar, MFM-112a and MFM-115a show high total gravimetric CH4 uptakes of 322 and 304 cm3 (STP) g–1, respectively, comparable to those measured for the best-behaving MOFs under the same conditions.31−34 In addition, MFM-115a shows a high volumetric total CH4 capacity of 186 v/v when compared to other high-performing CH4 uptake materials such as MOF-519,35 PCN-14,36 and NU-12524a,31,37 at 35 bar and 298 K. In comparison, MFM-112a has a lower total volumetric CH4 uptake of 162 v/v at 35 bar. Although MFM-132a shows lower total gravimetric CH4 uptake of 249 cm3 (STP) g–1 than MFM-112a, it has the same volumetric uptake of 162 v/v at 35 bar and 298 K owing to the higher crystal density of MFM-132a. At 80 bar, MFM-115a and MFM-112a both show remarkable increases in their total CH4 adsorption capacities to 419 and 469 cm3 g–1, equivalent to volumetric uptakes of 256 and 236 v/v, respectively. MFM-132a has a lower surface area and pore volume, resulting in a lower uptake of 213 v/v compared to MFM-112a and MFM-115a at 80 bar and 298 K.

Figure 2.

Comparison of high-pressure CH4 adsorption data for the best-performing MOFs. (a) High-pressure volumetric CH4 adsorption isotherms for MFM-115a, MFM-112a, and MFM-132a in the pressure range 0–90 bar at 298 K. (b) Comparison of the deliverable CH4 capacity for a range of MOFs at 298 K.

The deliverable capacity, defined as the amount of CH4 released from the storage system between a high-pressure stage (generally 65–80 bar) and a low-pressure stage (typically 5 bar), is of direct relevance to the practical performance of a given storage medium. MFM-115a and MFM-112a show high deliverable CH4 capacities of 191 v/v and 181 v/v between 65 and 5 bar at 298 K, respectively, comparable with the best performing CH4 storage materials such as [Co(bdp)]38 (bdp2– = 1,4-benzenedipyrazolate) (197 v/v) and UTSA-76a (196 v/v).39 Significantly, MFM-115a exhibits an exceptionally high deliverable CH4 capacity of 208 v/v between 80 and 5 bar at room temperature, rivaling those reported for the state-of-the-art materials (Figure 2b, Table 1) such as MOF-905 (203 v/v),40 Al-soc-MOF-1 (201 v/v),41 and HKUST-1 (200 v/v).31 MFM-112a also exhibits an excellent performance in delivering 200 v/v of CH4 between 80 and 5 bar at 298 K. In contrast, compared to both MFM-112a and MFM-115a, MFM-132a shows lower deliverable (to 5 bar) CH4 capacities of 150 and 162 v/v at 65 and 80 bar, respectively. The isosteric heats of adsorption (Qst) at low CH4 loading are estimated to be 16.2, 16.3, and 15.7 kJ mol–1 for MFM-112a, MFM-115a, and MFM-132a, respectively. These values are comparable to other MOFs with open Cu(II) sites.26,32

Table 1. Comparison of CH4 Adsorption Data for a Variety of MOFs at 298 K.

| total uptake at 35 bar | deliverable CH4 capacity (5 to 35 bar) | total CH4 uptake at 65 bar | deliverable CH4 capacity (5 to 65 bar) | total uptake at 80 bar | deliverable CH4 capacity (5 to 80 bar) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| material | BET surface area (m2/g) | pore volume (cm3/g)b | crystal density (g/cm3) | v/v | v/v | v/v | v/v | v/v | v/v |

| MFM-115a | 3394 | 1.38 | 0.611 | 186 | 138 | 238 | 191 | 256 | 208 |

| MFM-112a | 3800 | 1.62 | 0.503 | 162 | 125 | 218 | 181 | 236 | 200 |

| MFM-132a | 2466 | 1.06 | 0.65 | 162 | 109 | 201 | 150 | 213 | 162 |

| Co(bdp)38 | 2911a | 1.02 | 0.774 | 161 | 155 | 203 | 197 | ||

| MOF-90540 | 3490 | 1.34 | 0.537d | 145 | 120 | 206 | 181 | 228 | 203 |

| Al-soc-MOF-141 | 5585 | 2.3 | 0.34 | 127 | 106 | 197 | 176 | 221 | 201 |

| MOF-51935,40 | 2400 | 0.938 | 0.953 | 200c | 151c | 260c | 209c | 279c | 230c |

| UTSA-76a39 | 2820 | 1.09 | 0.699 | 211 | 151 | 257 | 196 | ||

| HKUST-17,31 | 1850 | 0.78 | 0.883 | 227 | 150 | 267 | 190 | 272 | 200 |

| PCN-147,31,36 | 2000 | 0.85 | 0.829 | 195 | 128 | 230 | 157 | 250 | 178 |

| NU-125 (NOTT-122a)24a,31,37 | 3286 | 1.41 | 0.589 | 182 | 135 | 232 | 183 | ||

| Ni-MOF-747,29,31 | 1350 | 0.51 | 1.206 | 228 | 106 | 251 | 129 | 267 | 152 |

| Cu-tbo-MOF-542 | 3971 | 1.12 | 0.595 | 151 | 110 | 199 | 158 | 216 | 175 |

| MOF-17743 | 4500 | 1.89 | 0.427 | 122 | 102 | 205 | 185 | ||

| MOF-21043 | 6240 | 3.6 | 0.25 | 82 | 69 | 141 | 128 | 166 | 154 |

Langmuir surface area.

Pore volume was measured by N2 adsorption isotherms at 77 K.

These values are likely overestimated due to difficulty in controlling composition of MOF-519.40

Crystal density determined from pycnometer density data.

Comparison of the CH4 adsorption in these three materials reveals interesting findings. MFM-115a, with moderate porosity across this series of MOFs, displays the highest methane deliverable capacity, outperforming MFM-112a, which shows slightly higher surface area and pore volume. The only structural difference between MFM-112a and MFM-115a lies in the central triangular organic moiety of the hexagonal linker face (Figure 1). We therefore argued that the pore environment created by the rotating phenylene rings in the linker can affect and perhaps control the gas adsorption properties of the host materials.

2H NMR Spectroscopic Studies

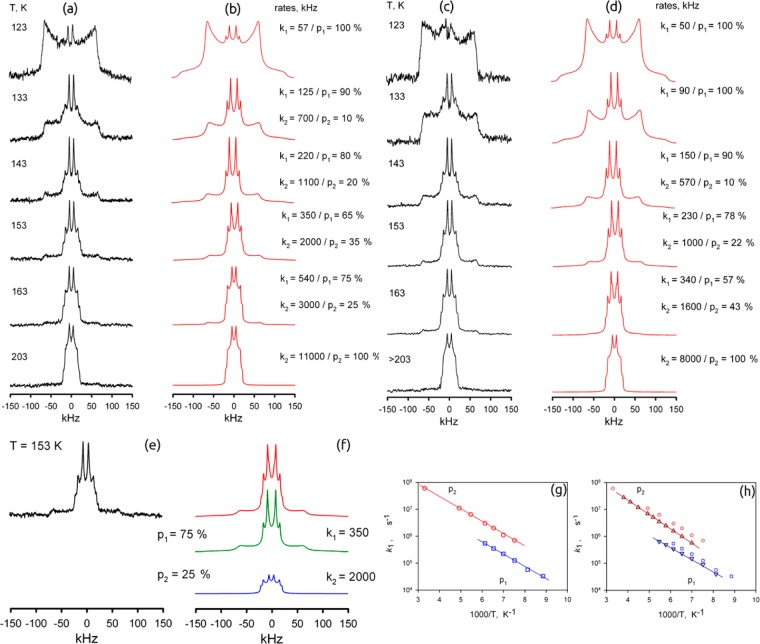

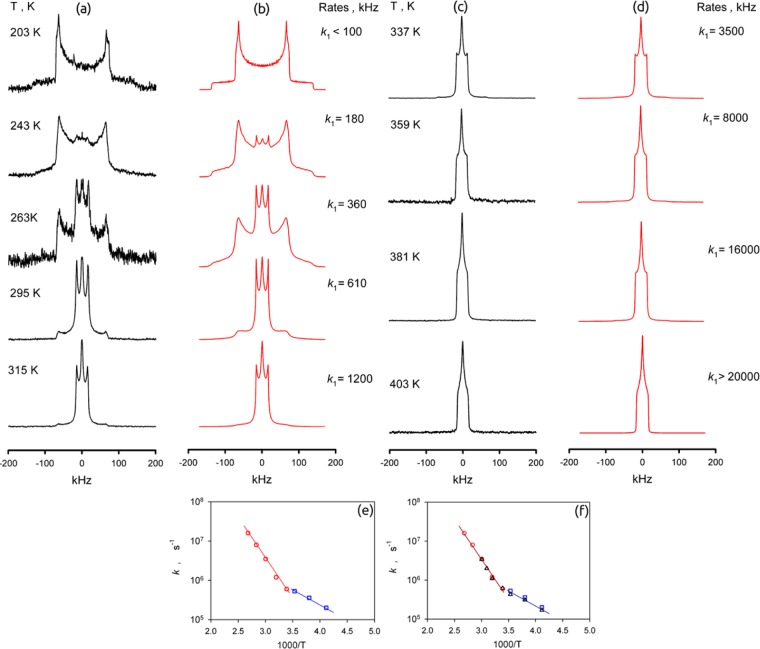

Solid-state 2H NMR spectroscopy was used to investigate the molecular dynamics of the rotating aromatic rings in this series of MOFs. This is a very powerful experimental technique well suited to monitor the molecular reorientations over a wide range of characteristic rates (103–107 s–1) and geometries (angular displacement >5°) in the solid state.44,45 The three MOFs were partially deuterated by selectively introducing D atoms on the aromatic rings in the ligands (see Supporting Information Section S4). The solid-state 2H NMR spectra for MFM-112a-d12, MFM-115a-d12, and MFM-132a-d24 were collected over a range of temperatures (100–525 K, up to the temperature limit of the NMR magnet probe) to follow their structural dynamics (Figures 3, 5, and 6). The molecular motion was analyzed by the evolution of the 2H NMR line shape arising from the perdeuterated fragments in the frameworks in a given temperature range. The temperature evolution of the 2H NMR line shape typically involves three stages: (i) static, when k < 103 s–1 (the rotational rate constant) with the line shape dependent solely on the electronic configuration of the C–D bond; (ii) intermediate exchange with 103 < k < 107 s–1 with the line shape reflecting both the rate and the geometry of the motion; and (iii) fast limit when k > 107 s–1 with an averaged line shape reflecting the final geometry but not the rate of the molecular orientation (Figure S20). We probed as wide a temperature range as possible to study the most informative, intermediate exchange regime for each material.

Figure 3.

Temperature-dependent 2H NMR line shapes for the deuterated phenylene fragments in guest-free MFM-112a-d12: (a) experimental and (b) simulation; MFM-112a-d12 loaded with CH4 (10 bar at 298 K): (c) experimental and (d) simulation. (e) 2H NMR spectrum for the guest-free MFM-112a-d12 comprising (f) two dynamic phases at T = 153 K. (g) Arrhenius plots of the rotation rate constants k1 (□) and k2 (○) for the two corresponding phases of the guest-free MFM-112a-d12 and (h) k1 (∇) and k2 (Δ) for MFM-112a-d12 loaded with CH4 at 10 bar and 298 K.

Figure 5.

Temperature-dependent 2H NMR line shapes for the deuterated phenylene fragments in guest-free MFM-115a-d12: (a, c) experimental and (b, d) simulation. (e) Arrhenius plots of the rotation rate constant k1 (○ and □) for the guest-free MFM-115a-d12 and (f) k1 (Δ) for the MFM-115a-d12 framework loaded with CH4 at 10 bar and 298 K.

Figure 6.

Variable-temperature 2H NMR line shapes for MFM-132-d24: (a) experimental and (b) simulation. The 2H NMR spectrum of MFM-132-d24, (c) experimental and (d) simulation, is composed of two signals (e and f), which correspond to geometrically different C–D groups on the anthracene fragment. The green spheres represent deuterium atoms.

MFM-112a-d12

As shown in Figure 3, the numerical line shape analysis indicates that the rotation of the phenylene fragment in MFM-112a-d12 is realized by a four-site jump exchange between four positions given by the following axial angles: φ1 = 40°, φ2 = 140°, φ3 = 220°, φ4 = 320° (Figure 4 and Figure S21). Interestingly the 2H NMR spectroscopic data reveal two dynamically different states for rotation of the linker in MFM-112a-d12. In each state the geometry of the rotation is the same, but the rate at each temperature is different. These two dynamic phases (states) of MFM-112a-d12 coexist between 133 and 163 K. Below 133 K the material is the phase p1 (rate k1), while above 163 K it fully switches to phase p2 (rate k2). In both states the corresponding rate constants k1 and k2 obey the simple Arrhenius law (Figure 3g) and are characterized by the same activation barrier (E = 8.6 kJ mol–1). The only difference is in the pre-exponential (collision) factor, which differs by a factor of six: k1,0 = 3 × 108 s–1, k2,0 = 18 × 108 s–1. The nature of these two states requires additional investigation, and the change of the dynamic state for the mobile fragment in the linker in MFM-112-d12 is most likely associated with the change of the steric interactions between the rotating phenylene rings and the central immobile phenyl ring at different temperatures.46

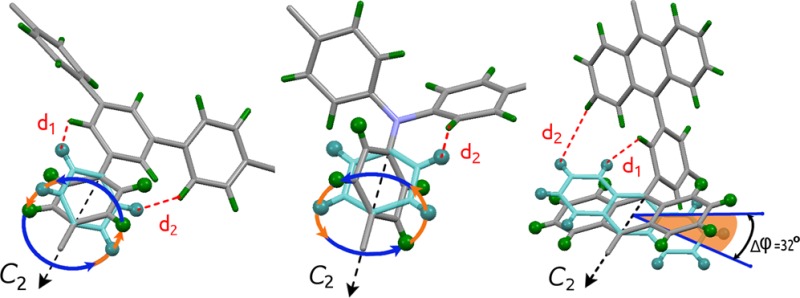

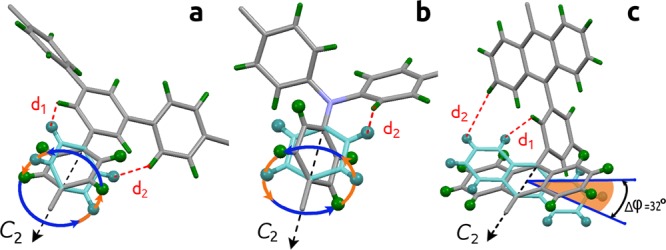

Figure 4.

View of the rotational models probed by solid-state 2H NMR spectroscopy for the partially deuterated MFM series in this study: (a) MFM-112a-d12, (b) MFM-115a-d12, and (c) MFM-132a-d12.

Line shape analysis for MFM-112a-d12 loaded with CH4 (10 bar of equilibrium pressure above the MOF at 298 K in a sealed glass NMR cell) (Figure 3c,d) shows that the linker rotation mechanism remains unchanged, but the actual rates are affected as the CH4 guest molecules partially block the linker rotation.47 The corresponding rates and temperature dependences are shown in Figure 3h. It follows that for the low-temperature phase p1 the effect of CH4 presence is reflected in the collision factor, which is smaller by a factor of ∼0.62 relative to the guest-free material. The second phase p2 is also characterized by a smaller rotation rate compared to the guest-free material, but the barrier is slightly increased up to E ≈ 10 kJ mol–1 (k2,0 = 29 × 108 s–1). However, it should be noted that this small increase in activation energy is most likely related to the partial desorption of CH4 from the pores above 200 K.

MFM-115a-d12

As shown in Figure 5 the line shape develops from a static pattern to a dynamically averaged one between 203 and 315 K. However, in the static case, the pattern is characterized by a nuclear quadrupolar coupling constant Q0 = 184 kHz and an asymmetry parameter η0 = 0.06, which is unusual and shows how strongly the electronic state of the mobile phenylene groups is distorted by the nitrogen core of the ligand. The averaged pattern is given by a narrowed line shape, as expected for axial rotation of the phenylene groups around the C2 symmetry axis (Q1 ≈ 20 kHz ≈ Q0/8).48 However, the narrowed patterns are characterized by an even larger asymmetry parameter η ≈ 1, indicating that the geometry of the rotation is different from that in MFM-112a-d12. As observed in the Arrhenius plot (Figure 5e), the temperature dependence of the exchange rate constant k is characterized by two regions: below 283 K the motion is characterized by a barrier E = 14 kJ mol–1 and a collision factor k0 = 2 × 108 s–1; above 283 K the barrier increases to E = 40 kJ mol–1 and a collision factor k0 = 5 × 1012 s–1. The mechanism of rotation is given by a four-site jump rotation, but above 283 K the six-site jump rotation gives slightly better agreement with the experimental patterns (Figure S21). The positions for the four-site rotation are given by the following axial angles: φ1 = 42°, φ2 = 138°, φ3 = 222°, φ4 = 318°. Those for the positions for the six-site rotation are φ1 = 42°, φ2 = 90°, φ3 = 138°, φ4 = 222°, φ5 = 270°, φ6 = 318°.

Such drastic changes in both activation barrier and the pre-exponential factor indicate that there are two possible rotational stochastic mechanisms that compete, with the 2H NMR line shape reflecting the faster motion. In MFM-115a-d12 the three rotating phenylene groups are bound to a single N-center, and hence their steric interaction is expected to be notably stronger than in MFM-112a-d12. Thus, the individual rotation of each phenylene ring is expected to be characterized by a high activation energy and a normal pre-exponential factor of ∼1012 s–1. However, since the three phenylene groups create a molecular “gear-like” mechanism, we might expect correlated rotation. In such a case the overall activation barrier might be expected to be much lower compared to individual rotations. However, the chance for such cooperative motion occurring (i.e., the number of attempts) is much lower as well. Therefore, the low-energy mode is characterized by a much lower pre-exponential factor of ∼108 s–1. To our knowledge, this is the first example of direct observation of how the cooperative molecular rotations in MOFs are switched to an individual motif.

The CH4-loaded sample of MFM-115a-d12 (10 bar of equilibrium pressure above the MOF at 298 K in a sealed glass NMR cell) showed identical line shape and temperature dependence compared to the guest-free material. The corresponding rate constants are shown in Figure 5f. Thus, the effect of CH4 on the rotation of the phenylene rings in MFM-115a-d12, even at elevated pressure, is negligible, probably reflecting the higher temperatures required for rotational mobility in MFM-115a-d12 compared with MFM-112a-d12.

MFM-132-d24

The 2H NMR spectrum is composed of two signals, which correspond to geometrically different C–D groups on the anthracene (Figure 6e,f), the line shape (Figure 6) of which does not change from 203 K up to 525 K. However, the C–D groups on the bulky anthracene ring are also different in terms of their capability to sense dynamics. The angle between the C–D bond and the rotational axis (the C2 symmetry axis along C9 and C10 of the anthracene ring) is 60 degrees for D at positions 2, 3, 6, and 7, i.e., the same as for a typical phenylene group, and is 0 degree for the C–D groups at positions 1, 4, 5, and 8. The latter will not sense any motion around the rotational axis due to its angular configuration.48 Therefore, the line shape splits into a pattern with Q1 = 153 kHz and an asymmetry parameter η1 = 0.08 for the C–D groups at 2, 3, 6, and 7 positions, and a pattern with typical static parameters Q2 = 176 kHz and η2 = 0.0 for the C–D groups at the 1, 4, 5, and 8 positions. Since the line shapes do not change within this temperature range, no large-amplitude motions are present. But the slightly averaged pattern of the terminal C–D group indicates that the anthracene fragments are in fact involved in fast but limited (Δφ = 32°) angular librations. Similar librations of organic groups in porous materials have been observed recently for ZIF-8.49 The CH4-loaded sample of MFM-132a-d24 (10 bar of equilibrium pressure above the MOF at 298 K in a sealed glass NMR cell), as for MFM-115a-d12, shows identical line shape and temperature dependence to the guest-free material.

NMR Spectroscopic Summary

Comparison of the NMR spectroscopic results shows that the least sterically hindered phenylene rings in MFM-112a-d12 are involved in full 360° rotation around the C2 symmetry axis and are static only for T < 100 K; the intermediate region occurs around 153 K, and these rings show fast motion at T > 203 K. In the case of MFM-115a-d12, the full axial rotation of the deuterated phenylene rings persists, but the whole dynamic range is shifted to higher temperature by ∼150 K. Thus, there is no rotation at 200 K, with the intermediate stage occurring around 300 K, with the fast limit reached above 403 K. The greater steric confinement of the branched phenylene rings in the hexacarboxylate linkers in MFM-115a-d12 compared to MFM-112a-d12 is well described by the activation barriers of the rotation: 40 kJ mol–1 for MFM-115a-d12 versus 8.6 kJ mol–1 for MFM-112a-d12. This is also consistent with the geometric environment of the branched phenylene rings in MFM-112 and MFM-115 obtained from the single-crystal X-ray structural analysis. Two distances are thus defined: d1 is the distance between the closest hydrogens of the mobile fragment and the nonrotating central core in the ligand face, while d2 is the distance between the closest hydrogens of two neighboring mobile fragments (Figure 4). When the central phenyl core in the hexacarboxylate unit in MFM-112 is replaced with a nitrogen atom in MFM-115, the shortest possible distance between the phenylene hydrogens decreases from 1.9 Å (d1 in MFM-112) to 0.8 Å (d2 in MFM-115), thereby creating a considerably tighter confinement for the phenylene ring rotation in MFM-115.

In contrast, the NMR spectroscopic analysis of MFM-132a-d24 confirms that no full rotation of the anthracene rings is possible due to the steric hindrance of neighboring anthracene rings in this (3,24)-connected network. Indeed, no notable motion was detected up to the thermal decomposition of the material at T > 567 K. However, the observed line shapes show that the anthracene rings are not completely static, being involved in fast but limited angular librations. Thus, for MFM-132a, the steric restriction is sufficient to render the anthracene group almost immobilized in a well-defined position.

In situ2H NMR spectra for the three samples loaded with CH4 were collected to probe the effect of CH4 adsorption on the rotational molecular dynamics of the frameworks. The line shape analysis indicates that the ligand rotation in MFM-112a-d12 is affected by the adsorption of CH4, revealing a reduced rate of rotation. This indicates that CH4 interacts with linkers by random collision and inhibits the rotation in the range T = 123–203 K. In contrast, addition of CH4 to MFM-115a-d12 (or to MFM-132a-d24, where there is only libration) causes no observed changes to the rotation of the phenylene groups. Rotation for MFM-115a-d12 occurs over the range T = 203–403 K, much higher than for MFM-112a-d12, and it appears that rotation of phenylene groups at this elevated temperature will therefore not be effected by the relatively low energy collisions with CH4 molecules.

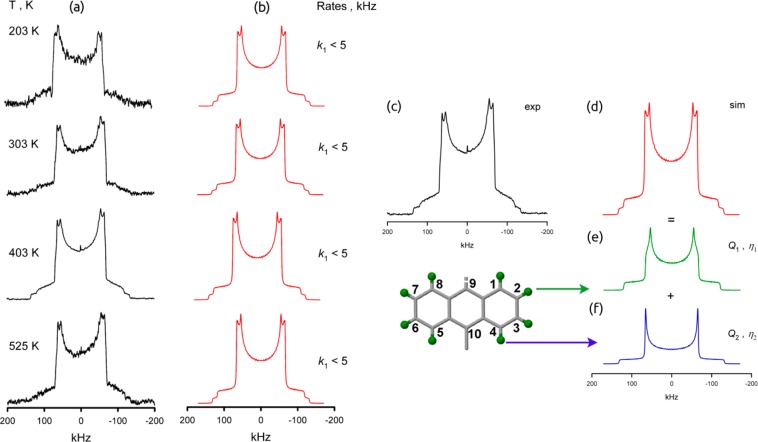

Neutron Powder Diffraction (NPD) Studies

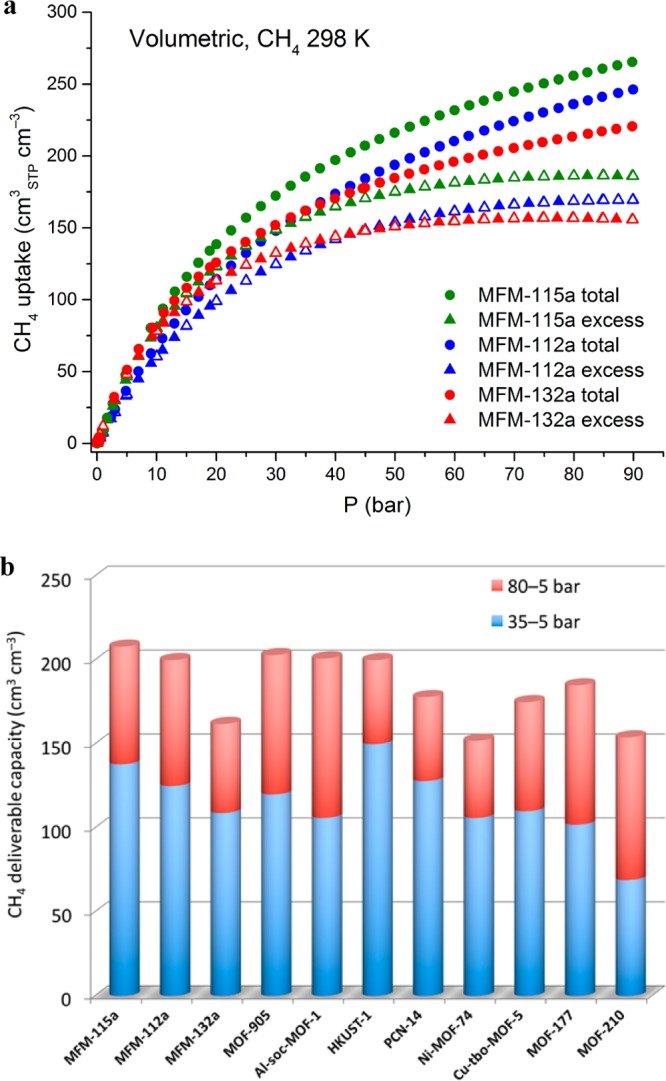

The locations of adsorbed molecules within MFM-132a and MFM-115a were determined by in situ NPD as a function of CD4 loading. NPD patterns were recorded at 10 K for the desolvated materials and at loadings of 0.25 and 0.5 CD4/Cu for MFM-132a and of 1.0 and 1.5 CD4/Cu for MFM-115a (see Supporting Information Section 6). MFM-132a shows highly hindered cage geometry and restricted molecular dynamics owing to the anthracene functionalization and was therefore selected for the investigation of CH4 binding at low loading where adsorption is dominated by pore geometry and surface chemistry. In parallel, CH4 binding at higher surface coverage was studied in MFM-115a, which displays a record high CH4 storage capacity, in order to probe the distribution of CH4 within the structure to a wider extent. Fourier difference map analysis of the NPD data of the desolvated MOFs indicates no residual nuclear density peak in the pore, thus confirming the effective activation and structural stability of the desolvated samples. Upon loading of the targeted amount of CD4 into the desolvated MOFs, sequential Fourier difference map analysis revealed the position of the center of mass of the adsorbed CD4 molecules, which were further developed by Rietveld refinement of these data. Analysis of the lattice parameters of gas-loaded MOFs confirms the absence of notable structural changes.

For MFM-132a at 0.25 CD4/Cu loading, Rietveld analysis revealed four distinct CD4 binding sites, the strongest of which was located in the [(Cu2)3(isophthalate)3] window pocket (denoted site A1; Figure 7). The cavity formed by three isophthalate rings and the enclosed anthracene moieties shows an internal void with a diameter of only ∼6 Å, which can accommodate only one CD4 molecule; this molecule sits on the C3-axis of the pocket at a distance of 3.88(1) Å from the center of the isophthalate ring. The three anthracene units at the bottom of the pocket further stabilize the CD4 molecule via strong space confinement with a close distance of 2.41(1) Å between the D atoms of CD4 and the H atoms on the anthracene rings. Significantly, nearly 50% of loaded CD4 is found on site A1, confirming the presence of strongly geometrical-hindered binding sites in MFM-132a. In addition, ∼40% of loaded CD4 is found equally distributed on the two open Cu(II) sites with one protruding into the cuboctahedral cage while the other is pointing outside the cage, denoted as the second (A2) and third (A3) binding sites, respectively. Thus, in the case of MFM-132a, a tight pocket constructed solely from aromatic rings that matches the symmetry of a CD4 molecule shows higher affinity for CD4 than open Cu(II) sites. Importantly, the open Cu(II) centers in MOFs are found not to be the strongest binding site for adsorbed methane molecules, and this may be in part due to the introduction of steric hindrance within the pores of the MOF.

Figure 7.

CD4 adsorption sites revealed by Rietveld analysis of the NPD data for MFM-132a with CD4 dosing at 0.25 and 0.5 CD4/Cu. (a) The strongest CD4 binding site is located in the small pocket created by the [(Cu2)3(isophthalate)3] window and three anthracene rings. There are four of this type of pocket in a truncated tetrahedron (cage B). (b) The four binding sites within the partial structure showing cage A and cage B, both sharing the triangular [(Cu2)3(isophthalate)3] window. (c) Side and (d) top-down view of the tight pocket created by the [(Cu2)3(isophthalate)3] window and three anthracene rings. The two Cu(II) ions on the same [Cu2(O2CR)4] paddlewheel show similar CD4 binding. Color scheme: C, teal; H, gray; Cu, aqua; site A1, violet; sites A2 and A3, pink; site A4, orange.

The fourth adsorption site (A4) is located inside the cuboctahedron and near the [(Cu2)3(isophthalate)3] window with a distance of 3.56(6) Å from the A1 site and accounts for ∼10% of loaded CD4. The CD4 molecule on this site also sits on the 3-fold axis of the triangular window. A4 also shows close contacts [CD4 (centroid)···CD4 (centroid) = 3.84(6) Å] with the CD4 molecules on site A2. The CD4 on site A4 therefore occupies the pocket created by the three CD4 molecules adsorbed on the three closest open Cu(II) sites of the triangular window and the encapsulated CD4 within the small 6 Å cavity (site A1), indicating the presence of intermolecular adsorbate–adsorbate interaction that stabilizes the packing of methane molecules in the structure. No additional site was identified at the higher loading of 0.5 CD4/Cu, where the occupancies for all four binding sites increase proportionately. Notably, the A1 site occupancy remains the highest of the four sites identified, further confirming the strong affinity between CD4 molecules and this tight pocket.

The NPD study of MFM-115a at both 1.0 and 1.5 CD4/Cu loadings revealed four binding sites (denoted A1′, A2′, A3′, and A4′ in order of decreasing occupancy; Figure 8). A1′ and A2′ are found within the triangular [(Cu2)3(isophthalate)3] window, and A3′ and A4′ are located on the open Cu(II) sites. At the first loading, site A1′ is located on the 3-fold axis of the [(Cu2)3(isophthalate)3] window. This is not surprising because site A1′ sits in the tight pocket created by three CD4 molecules on site A3′ and one CD4 on site A2′, indicating the presence of strong intermolecular dipole interaction. Site A2′ also resides on the 3-fold axis of the small triangular window, having a similar location to the strongest adsorption site A1 observed in MFM-132a, but with a longer distance of 4.34(3) Å to the center of the isophthalate ring. The reduction in binding affinity of A2′ in MFM-115a is a direct result of the absence of a tight cavity formed by organic moieties as found in MFM-132a. To our surprise, the two types of open Cu(II) sites in MFM-115a have distinct occupancies, with the one located inside the cuboctahedral cage showing almost five times the occupancy as the other one outside this cage. This observation indicates that 12 methane molecules inside the cuboctahedral cage show a compact geometry in MFM-115a. The two opposite [Cu2(O2CR)4] paddlewheels in cage D are separated by a shorter distance in MFM-115a than in MFM-132a due to the smaller size of the hexacarboxylate ligand in the former. This effectively accounts for the difference of CD4 binding behavior on the open Cu(II) sites in these two structures. Thus, the distance between two opposite Cu(II) sites in cage D in MFM-115a is 3.95(5) Å, much shorter than that [6.83(5) Å] observed in MFM-132a. At the 1.5 CD4/Cu loading, additional CD4 molecules are mainly populated across sites A1′, A2′, and A3′, further indicating a unique and optimized CD4 packing geometry in MFM-115a.

Figure 8.

CD4 adsorption sites in MFM-115a revealed by neutron powder diffraction at a loading of 1.0 CD4/Cu. (a) CD4 sites in the cuboctahedral cage showing CD4 molecules are compacted within this cage. (b) CD4 sites within the partial structure of a tetrahedral cage. Due to the shorter distance between the two opposite [Cu2(O2CR)4] paddlewheels in cage D (on the edge of the tetrahedron) in MFM-115a compared with that in MFM-132a, the two CD4 sites (A4′) show a close contact of 3.95(5) Å. (c) Close view of the four binding sites. Site A1′ sits within the tight pocket created by three CD4 on site A3′ and one CD4 on site A2′, indicating an optimum packing geometry of CD4 molecules in MFM-115a. (d) Top-down view of the small triangular window. Color scheme: C, teal; H, gray; Cu, aqua; site A1′, orange; site A2′, green; sites A3′ and A4′, pink.

Conclusions

A family of isostructural (3,24)-connected frameworks, MFM-112a, MFM-115a, and MFM-132a, shows interesting and distinct CH4 adsorption properties. The overall structures of these materials are constructed by alternate packing of four types of metal–organic coordination cages with varying geometry and sizes. Specifically, MFM-132 contains a type of highly geometrically hindered cages (diameter of ∼6 Å) because of the anthracene functionalization. MFM-112a, MFM-115a, and MFM-132a possess high, moderate, and relatively low porosity, respectively. Significantly, MFM-115a displays exceptionally high deliverable CH4 storage capacity [208 v/v (5–80 bar)] at room temperature, comparable with the best performing porous solids reported to date. MFM-112a also reveals excellent CH4 adsorption capacity at high pressure owing to its high surface area and pore volume. In contrast, MFM-132a shows relatively low CH4 storage capacity. Thus, there is a direct correlation between the structure design and materials function across this series of MOFs.

The molecular motions of the rotating aromatic rings in the corresponding partially deuterated materials MFM-112a-d12, MFM-115a-d12, and MFM-132a-d24 were investigated using in situ solid-state 2H NMR spectroscopy. The results reveal that the branched phenylene ring rotation in MFM-115a-d12 shows an energy barrier that is almost 5 times higher than that in MFM-112a-d12. The anthracene ring in MFM-132a-d24 shows very limited angular librations within its confinement, which allows the anthracene rings to form stable well-defined cavities within the framework. The CH4 loading affects the ligand rotation in MFM-112a-d12 slightly, but does not pose any notable hindrance for the ligand mobility in MFM-115a-d12 and MFM-132a-d24. The NMR spectroscopic study confirms that MFM-112a, MFM-115a, and MFM-132a have fast, medium, and slow molecular dynamics, respectively. Investigations on the binding sites for CD4 within MFM-132a and MFM-115a reveal that the primary binding site is located within the small pocket enclosed by the [(Cu2)3(isophthalate)3] window and three anthracene/phenyl panels. This pocket shows strong van der Waals interactions with CD4 due to the small cavity size and has an excellent size and geometric match for a single CD4 molecule. The open Cu(II) sites are the secondary/tertiary adsorption sites in these structures. Thus, direct experimental evidence has been obtained showing that a tight cavity can generate a stronger binding affinity for gas molecules than open metal sites, which are widely reported as the primary binding sites in various MOFs. Thus, the NPD coupled with 2H NMR spectroscopy confirms that a combination of optimum molecular dynamics and pore geometry/size leads to the interesting CH4 adsorption performance in these materials.

Experimental Section

Synthesis of MFM-112 and MFM-115

MFM-112 and MFM-115 were synthesized following the methods adapted from previous reports.22,24b Specifically, a solution of H6TDBB (1,3,5-tris(3′,5′-dicarboxy[1,1′-biphenyl]-4-yl)benzene) (or H6NTBD = 4′,4″,4‴-nitrilotribiphenyl-3,5-dicarboxylic acid, 0.1 mmol, 1.0 equiv) and Cu(NO3)2·2.5H2O (93 mg, 4.0 equiv) in N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF, 40 mL) and H2O (4 mL) was placed in a 100 mL pressure flask. To the mixture was added 2M HCl (0.5mL), and the pressure flask was sealed and heated at 90 °C in an oil bath for 24 h. The obtained crystals were filtered and washed with DMF (20 mL × 2). The as-synthesized materials were exchanged in acetone for 3 days before being activated for gas sorption experiments.

Synthesis of [Cu3(BTAT)(H2O)3]·9DMF (MFM-132)

H6BTAT (50 mg, 0.045 mmol) (see Supporting Information Section S1) and Cu(NO3)2·2.5H2O (63 mg, 0.27 mmol) were dissolved in a mixture of DMF (8.0 mL) and H2O (0.5 mL), and the solution placed in a pressure tube (15 mL). Upon addition of 6 M HCl (15 μL), the tube was capped and heated at 90 °C for 16 h. A large amount of microcrystalline product precipitated: the blue crystals were collected by filtration and washed with warm DMF and dried in air. Yield: 77 mg (85%). Selected FTIR (neat, cm–1): 1655 (vs), 1632 (vs), 1587 (w), 1493 (w), 1434 (s), 1366 (vs), 1299 (w), 1253 (m), 1195 (w), 1149 (w), 1095 (s), 1060 (w), 1027 (w), 942 (w), 922 (w), 864 (w), 774 (vs), 734 (m), 701 (m), 660 (s), 648 (m). Anal. Calcd (%) for C99H105Cu3N9O24: C, 59.59; H, 5.30; N, 6.32. Found (%): C, 60.38; H, 5.31; N, 6.78.

High-Pressure CH4 Adsorption Measurements

CH4 sorption measurements (0–90 bar) were performed using a XEMIS gravimetric adsorption apparatus (Hiden Isochema, Warrington, UK) equipped with a clean ultra-high-vacuum system. The pressure in the system is accurately regulated by mass flow controllers. All measurements were made with ultra-high-purity grade (99.999%) CH4 or He, the latter being used for framework skeletal volume measurements. Sample containers of a known weight were loaded with ∼100 mg of desolvated sample under Ar, and the samples were further degassed at 100 °C for 16 h before adsorption of CH4.

Solid-State 2H NMR Spectroscopy

To prepare samples for the NMR experiments, 50–70 mg of partially deuterated MOF was loaded as a fine powder into a 5 mm (o.d.) glass tube and connected to a high-vacuum line. The sample was heated at 100 °C for 24 h under vacuum to a final pressure above the sample of 10–2 Pa to ensure removal of any remaining traces of guest molecules. The neck of the tube was then flame-sealed, while the sample was maintained in liquid nitrogen in order to prevent the heating from the flame. The sealed sample was then transferred into an NMR probe for analysis with 2H NMR spectroscopy.

2H NMR spectroscopic experiments were performed at the Larmor frequency ωz/2π = 61.42 MHz on a Bruker Avance-400 spectrometer using a high-power probe with 5 mm horizontal solenoid coil. All 2H NMR spectra were obtained by Fourier transformation of the quadrature-detected phase-cycled quadrupole echo arising in the pulse sequence (90x° – τ1 – 90y – τ2 – acquisition – t), where τ1 = 20 μs, τ2 = 21 μs, and t is the repetition time of the sequence during the accumulation of the NMR signal.50 The duration of the π/2 pulse was 1.6 μs. Spectra were typically obtained with 1000–20000 scans with a repetition time of ∼0.4 s. The temperature of the samples was controlled with a flow of N2 gas using a BVT-3000 variable-temperature unit with a precision of ∼1 K. The 2H NMR spectra line shape simulations were performed using an in-house FORTRAN program package based on the general formalism given in the Supporting Information Section S5.

Neutron Powder Diffraction

NPD measurements were performed on the bare MOF and the same sample loaded with CD4 using the WISH high-resolution powder diffractometer at the ISIS pulsed neutron source, Rutherford Appleton Laboratory, UK. Prior to NPD experiments, the desolvated sample of MFM-132a (1.4 g) or MFM-115a (1.8 g) was loaded into a cylindrical vanadium sample container with an indium ring vacuum seal and connected to a gas handling system. The sample was further degassed at 10–7 mbar and 100 °C for 24 h to remove any remaining trace guest solvents. The temperature during data collection was controlled using a helium cryostat operating at 10 ± 0.2 K. The loadings of CD4 were performed by a volumetric method at 150 K in order to ensure that CD4 was present in the gas phase when not adsorbed and also to ensure sufficient mobility of CD4 inside the crystalline structure. After collecting the NPD data for the bare material, target amounts of CD4 were introduced from the gas-panel system. The sample was then slowly cooled (over a period of 2 h) to 10 K to ensure that CD4 was completely adsorbed. Sufficient time was allowed to achieve thermal equilibrium before data collection. Time-of-flight neutron diffraction data were collected by five detector banks centered at 2θ = 27.1°, 58.3°, 90.0°, 121.7°, and 152.9°.

Due to the large unit cell of these two frameworks, rigid bodies were applied to the organic ligand and the CD4 molecules in the Rietveld refinements. Difference Fourier maps calculated from neutron diffraction data were used to locate the adsorbed CD4 molecules. The refinements on all the parameters including fractional coordinates, occupancies for the adsorbed CD4 molecules, and background/profile coefficients yielded satisfactory agreement factors. The total occupancies of CD4 molecules obtained from the refinement are also in good agreement with the experimental values for the CD4 loading. The refined structural parameters including the refined positions of the CD4 molecules are detailed in the Supporting Information Section S6.

Acknowledgments

We thank the EPSRC and the Universities of Manchester and Nottingham for funding. We are grateful to STFC and the ISIS Neutron Facility for access to Beamline WISH and to Diamond Light Source for access to Beamlines I11 and I19. M.S. gratefully thanks the ERC for an Advanced Grant (AdG 226593) and EPSRC (EP/I011870) for funding and acknowledges the Russian Ministry of Science and Education for the award of a Russian Megagrant (14.Z50.31.0006). M.S. and D.I.K. gratefully acknowledge receipt of the Royal Society International Exchanges Scheme grant ref IE150114. D.I.K. and A.G.S. acknowledge financial support by the Russian Academy of Sciences (budget project No. 0303-2016-0003 for Boreskov Institute of Catalysis).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/jacs.7b05453.

Synthetic details for organic linkers and partially deuterated compounds; gas adsorption data; solid-state 2H NMR spectroscopic and neutron powder diffraction analysis (PDF)

Author Contributions

¶ Y. Yan, D. I. Kolokolov, and I. da Silva contributed equally to this work.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Notes

CIF files can be obtained free of charge from the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif (CCDC 1499823–1499831).

Supplementary Material

References

- Service R. F. Science 2014, 346, 538–541. 10.1126/science.346.6209.538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh S. Energy Policy 2007, 35, 5865–5875. 10.1016/j.enpol.2007.06.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- International Energy Agency, World Energy Outlook 2011: Are We Entering a Golden Age of Gas, http://www.worldenergyoutlook.org.

- Makal T. A.; Li J.-R.; Lu W.; Zhou H.-C. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 7761–7779. 10.1039/c2cs35251f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin X.; Jia J.; Hubberstey P.; Schröder M.; Champness N. R. CrystEngComm 2007, 9, 438–448. 10.1039/B706207A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Murray L. J.; Dincă M.; Long J. R. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009, 38, 1294–1314. 10.1039/b802256a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason J. A.; Veenstra M.; Long J. R. Chem. Sci. 2014, 5, 32–51. 10.1039/C3SC52633J. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- He Y.; Zhou W.; Qian G.; Chen B. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 5657–5678. 10.1039/C4CS00032C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J.-R.; Sculley J.; Zhou H.-C. Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, 869–932. 10.1021/cr200190s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloch E. D.; Queen W. L.; Krishna R.; Zadrozny J. M.; Brown C. M.; Long J. R. Science 2012, 335, 1606–1610. 10.1126/science.1217544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang S.; Sun J.; Ramirez-Cuesta A. J.; Callear S. K.; David W. I. F.; Anderson D. P.; Newby R.; Blake A. J.; Parker J. E.; Tang C. C.; Schröder M. Nat. Chem. 2012, 4, 887–894. 10.1038/nchem.1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreno L. E.; Leong K.; Farha O. K.; Allendorf M.; Van Duyne R. P.; Hupp J. T. Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, 1105–1125. 10.1021/cr200324t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao M.; Ou S.; Wu C.-D. Acc. Chem. Res. 2014, 47, 1199–1207. 10.1021/ar400265x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui Y.; Li B.; He H.; Zhou W.; Chen B.; Qian G. Acc. Chem. Res. 2016, 49, 483–493. 10.1021/acs.accounts.5b00530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa H.; Cordova K. E.; O’Keeffe M.; Yaghi O. M. Science 2013, 341, 974–986. 10.1126/science.1230444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao D.; Timmons D. J.; Yuan D.; Zhou H.-C. Acc. Chem. Res. 2011, 44, 123–133. 10.1021/ar100112y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillerm V.; Kim D.; Eubank J. F.; Luebke R.; Liu X.; Adil K.; Lah M. S.; Eddaoudi M. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 6141–6172. 10.1039/C4CS00135D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Easun T. L.; Moreau F.; Yan Y.; Yang S.; Schröder M. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2017, 46, 239–274. 10.1039/C6CS00603E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Zhang J.-P.; Liao P.-Q.; Zhou H.-L.; Lin R.-B.; Chen X.-M. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 5789–5814. 10.1039/C4CS00129J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Methane Opportunities for Vehicular Energy, Advanced Research Project Agency – Energy, U.S. Dept. of Energy, Funding Opportunity No. DE-FOA-0000672, 2012. https://arpa-e-foa.energy.gov/Default.aspx?Search=DE-FOA-0000672.

- Yan Y.; Yang S.; Blake A. J.; Schröder M. Acc. Chem. Res. 2014, 47, 296–307. 10.1021/ar400049h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farha O. K.; Yazaydın A. Ö.; Eryazici I.; Malliakas C. D.; Hauser B. G.; Kanatzidis M. G.; Nguyen S. T.; Snurr R. Q.; Hupp J. T. Nat. Chem. 2010, 2, 944–948. 10.1038/nchem.834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan Y.; Lin X.; Yang S.; Blake A. J.; Dailly A.; Champness N. R.; Hubberstey P.; Schröder M. Chem. Commun. 2009, 9, 1025–1027. 10.1039/b900013e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan Y.; Telepeni I.; Yang S.; Lin X.; Kockelmann W.; Dailly A.; Blake A. J.; Lewis W.; Walker G. S.; Allan D. R.; Barnett S. A.; Champness N. R.; Schröder M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 4092–4094. 10.1021/ja1001407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Yan Y.; Suyetin M.; Bichoutskaia E.; Blake A. J.; Allan D. R.; Barnett S. A.; Schröder M. Chem. Sci. 2013, 4, 1731–1736. 10.1039/c3sc21769h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Yan Y.; Blake A. J.; Lewis W.; Barnett S. A.; Dailly A.; Champness N. R.; Schröder M. Chem. - Eur. J. 2011, 17, 11162–11170. 10.1002/chem.201101341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan D.; Zhao D.; Sun D.; Zhou H.-C. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 5357–5361. 10.1002/anie.201001009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu H.; Simmons J. M.; Liu Y.; Brown C. M.; Wang X.-S.; Ma S.; Peterson V. K.; Southon P. D.; Kepert C. J.; Zhou H.-C.; Yildirim T.; Zhou W. Chem. - Eur. J. 2010, 16, 5205–5214. 10.1002/chem.200902719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulvey Z.; Vlaisavljevich B.; Mason J. A.; Tsivion E.; Dougherty T. P.; Bloch E. D.; Head-Gordon M.; Smit B.; Long J. R.; Brown C. M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 10816–10825. 10.1021/jacs.5b06657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Getzschmann J.; Senkovska I.; Wallacher D.; Tovar M.; Fairen-Jimenez D.; Düren T.; van Baten J. M.; Krishna R.; Kaskel S. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2010, 136, 50–58. 10.1016/j.micromeso.2010.07.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu H.; Zhou W.; Yildirim T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 4995–5000. 10.1021/ja900258t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spek A. L. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. D: Biol. Crystallogr. 2009, 65, 148–155. 10.1107/S090744490804362X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng Y.; Krungleviciute V.; Eryazici I.; Hupp J. T.; Farha O. K.; Yildirim T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 11887–11894. 10.1021/ja4045289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Y.; Zhou W.; Yildirim T.; Chen B. Energy Environ. Sci. 2013, 6, 2735–2744. 10.1039/c3ee41166d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X.-S.; Ma S.; Rauch K.; Simmons J. M.; Yuan D.; Wang X.; Yildirim T.; Cole W. C.; López J. J.; de Meijere A.; Zhou H.-C. Chem. Mater. 2008, 20, 3145–3152. 10.1021/cm800403d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy R. D.; Krungleviciute V.; Clingerman D. J.; Mondloch J. E.; Peng Y.; Wilmer C. E.; Sarjeant A. A.; Snurr R. Q.; Hupp J. T.; Yildirim T.; Farha O. K.; Mirkin C. A. Chem. Mater. 2013, 25, 3539–3543. 10.1021/cm4020942. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gándara F.; Furukawa H.; Lee S.; Yaghi O. M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 5271–5274. 10.1021/ja501606h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma S.; Sun D.; Simmons J. M.; Collier C. D.; Yuan D.; Zhou H.-C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 1012–1016. 10.1021/ja0771639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilmer C. E.; Farha O. K.; Yildirim T.; Eryazici I.; Krungleviciute V.; Sarjeant A. A.; Snurr R. Q.; Hupp J. T. Energy Environ. Sci. 2013, 6, 1158–1163. 10.1039/c3ee24506c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mason J. A.; Oktawiec J.; Taylor M. K.; Hudson M. R.; Rodriguez J.; Bachman J. E.; Gonzalez M. I.; Cervellino A.; Guagliardi A.; Brown C. B.; Llewellyn P. L.; Masciocchi N.; Long J. R. Nature 2015, 527, 357–361. 10.1038/nature15732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B.; Wen H.-M.; Wang H.; Wu H.; Tyagi M.; Yildirim T.; Zhou W.; Chen B. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 6207–6210. 10.1021/ja501810r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang J.; Furukawa H.; Zhang Y.-B.; Yaghi O. M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 10244–10251. 10.1021/jacs.6b05261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alezi D.; Belmabkhout Y.; Suyetin M.; Bhatt P. M.; Weseliński Ł. J.; Solovyeva V.; Adil K.; Spanopoulos I.; Trikalitis P. N.; Emwas A.-H.; Eddaoudi M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 13308–13318. 10.1021/jacs.5b07053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spanopoulos I.; Tsangarakis C.; Klontzas E.; Tylianakis E.; Froudakis G.; Adil K.; Belmabkhout Y.; Eddaoudi M.; Trikalitis P. N. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 1568–1574. 10.1021/jacs.5b11079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa H.; Ko N.; Go Y. B.; Aratani N.; Choi S. B.; Choi E.; Yazaydin A. Ö.; Snurr R. Q.; O’Keeffe M.; Kim J.; Yaghi O. M. Science 2010, 329, 424–428. 10.1126/science.1192160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tycko R.Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Probes of Molecular Dynamics; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- a Horike S.; Matsuda R.; Tanaka D.; Matsubara S.; Mizuno M.; Endo K.; Kitagawa S. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2006, 45, 7226–7230. 10.1002/anie.200603196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Gould S. L.; Tranchemontagne D.; Yaghi O. M.; Garcia-Garibay M. A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 3246–3247. 10.1021/ja077122c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Comotti A.; Bracco S.; Sozzani P. Acc. Chem. Res. 2016, 49, 1701–1710. 10.1021/acs.accounts.6b00215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Jiang X.; O’Brien Z. J.; Yang S.; Lai L. H.; Buenaflor J.; Tan C.; Khan S.; Houk K. N.; Garcia-Garibay M. A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 4650–4656. 10.1021/jacs.6b01398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Comotti A.; Bracco S.; Yamamoto A.; Beretta M.; Hirukawa T.; Tohnai N.; Miyata M.; Sozzani P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 618–621. 10.1021/ja411233p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Comotti A.; Bracco S.; Ben T.; Qiu S.; Sozzani P. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 1043–1047. 10.1002/anie.201309362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shustova N. B.; Ong T.-C.; Cozzolino A. F.; Michaelis V. K.; Griffin R. G.; Dincă M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 15061–15070. 10.1021/ja306042w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bracco S.; Miyano T.; Negroni M.; Bassanetti I.; Marchio’ L.; Sozzani P.; Tohnai N.; Comotti A. Chem. Commun. 2017, 53, 7776–7779. 10.1039/C7CC02983G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jelinski L. W.Deuterium NMR of Solid Polymers. In High Resolution NMR Spectroscopy of Synthetic Polymers in Bulk; Komoroski R. A., Ed.; VCH Publishers: New York, 1986; Vol. 7, p 335. [Google Scholar]

- Kolokolov D. I.; Stepanov A. G.; Jobic H. J. Phys. Chem. C 2015, 119, 27512–27520. 10.1021/acs.jpcc.5b09312. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Powles J. G.; Strange J. H. Proc. Phys. Soc., London 1963, 82, 6–15. 10.1088/0370-1328/82/1/303. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.