Abstract

Aging, the universal phenomenon, affects human health and is the primary risk factor for major disease pathologies. Progeroid diseases, which mimic aging at an accelerated rate, have provided cues in understanding the hallmarks of aging. Mutations in DNA repair genes as well as in telomerase subunits are known to cause progeroid syndromes. Werner syndrome (WS), which is characterized by accelerated aging, is an autosomal-recessive genetic disorder. Hallmarks that define the aging process include genomic instability, telomere attrition, epigenetic alterations, loss of proteostasis, deregulation of nutrient sensing, mitochondrial dysfunction, cellular senescence, stem cell exhaustion, and altered intercellular communication. WS recapitulates these hallmarks of aging and shows increased incidence and early onset of specific cancers. Genome integrity and stability ensure the normal functioning of the cell and are mainly guarded by the DNA repair machinery and telomeres. WRN, being a RecQ helicase, protects genome stability by regulating DNA repair pathways and telomeres. Recent advances in WS research have elucidated WRN’s role in DNA repair pathway choice regulation, telomere maintenance, resolution of complex DNA structures, epigenetic regulation, and stem cell maintenance.

Keywords: Werner Syndrome, WRN, DSB repair, Aging, Senescence, Telomere maintenance

Introduction

Werner syndrome (WS) is a segmental progeria. It belongs to a small group of disorders characterized by accelerated aging. WS patients in their 20s and 30s display features similar but not identical to those of normal older individuals, including skin atrophy, graying and loss of hair, wrinkles, loss of fat, cataracts, atherosclerosis, and diabetes (reviewed in Yokote et al. 1). WS is caused by mutations in the WRN gene and has an estimated global incidence ranging between 1 in 1,000,000 and 1 in 10,000,000 births; however, the incidence is higher in Japan at 1 in 100,000 births 2. WS is inherited in an autosomal-recessive manner. To date, a total of 83 different mutations in WRN have been identified and catalogued by the International Registry of WS (Seattle, WA, USA) and the Japanese Werner Consortium (Chiba, Japan) 2. Because of its resemblance to normal aging, WS is widely studied in the field of aging, and many consider WS the best example of an accelerated aging syndrome.

Diagnostic criteria for WS were proposed in 1994 3 and recently updated 4. Individuals with WS develop normally until their first decade, and the first clinical sign of the syndrome appears as lack of the pubertal growth spurt during their teen years. Affected individuals in their 20s and 30s begin to manifest skin atrophy and loss and graying of hair. Bilateral cataracts, abnormal glucose and lipid metabolism, hypogonadism, skin ulcers, and bone deformity appear by the fourth decade. Fatty liver, osteoporosis, and calcification of the Achilles tendon are also predominantly observed. WS may be a good model to study sarcopenia 5. Malignancy and atherosclerotic vascular diseases such as myocardial infarction are the major causes of death among patients with WS.

The WRN gene codes for the WRN protein. WRN is a member of the RecQ helicase family of proteins and is unique in that it possesses both helicase and exonuclease domains 6. WRN also has strand annealing activity, but its in vivo role remains unclear. Recently, López-Otín et al. created a list of pathways that are changed during aging 7. These hallmarks of aging pathways have been widely considered the key processes affected during aging. Since WS clinical features include many aspects of normal aging, it is not surprising that WRN functions in, or its loss impacts, many of these pathways. In this review, we survey the literature and compare each aging hallmark against patients with WS ( Table 1). We go on to describe a few key areas of recent WRN-related advances and then point out areas for future research.

Table 1. Hallmarks of aging in comparison with Werner syndrome.

| Aging hallmarks | Brief description | Werner syndrome (WS) | Reference for WS |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Genome

instability |

Alteration to the genetic information over time

due to DNA damage and defective DNA repair mechanisms. Genomic instability affects overall functions of the cell. |

Patient cells show gross genomic

instability. WRN-deficient cells display large deletions. |

Salk

et al.

8

Chen et al. 9 |

|

Telomere

attrition |

Progressive decrease in telomere length over

multiple cell divisions. Telomere attrition mainly occurs owing to the end-replication problem and the lack of telomerase enzyme. |

WRN interacts with Pot1 and TRF2

components of the shelterin complex to promote telomere maintenance. Telomere length in older patients with WS (40–60 years) is markedly shorter than in younger patients with WS (~30 years) and age-matched non-WS individuals. |

Opresko

et al.

11

Ishikawa et al. 10 Tokita et al. 72 |

|

Epigenetic

alterations |

Involves alterations in the DNA methylation patterns,

post-translational modification of histones, and chromatin remodeling |

Patients with WS show an increased

DNA methylation age with an average of 6.4 years. WRN interacts with methylation complex consisting of SUV39H1, HP1α, and LAP2β, which is responsible for the epigenetic histone mark H3K9 trimethylation (H3K9me3). In response to DNA damage, WRN recruits chromatin assembly factor 1 (CAF-1) to alter chromatin structure. |

Maierhofer

et al.

12

Jiao et al. 78 Zhang et al. 14 |

|

Loss of

proteostasis |

Impairment of protein homeostasis due to

accumulation of misfolded proteins and deregulation of proteolytic system. Chronic expression of misfolded, unfolded, or aggregation of proteins contributes to the development of age- related pathologies such as Alzheimer’s disease and cataracts. |

Cataracts are one of the most common

features observed in patients with WS. WRN expression is severely affected by promoter hypermethylation in age- related cataract lens cells. |

Zhu et al. 15 |

|

Mitochondrial

dysfunction |

Reduction in the biogenesis of mitochondria and

mitophagy. Reduced ATP production coupled with increased electron leakage. Oxidation of mitochondrial proteins. |

WS cells show increased reactive

oxygen species (ROS) production. Hepatocytes of Wrn (Δhel/Δhel) mice have decreased mitochondria and show altered mitochondrial functions. |

Cogger et al. 16 |

|

Cellular

senescence |

Stable arrest of the cell cycle coupled with

stereotyped phenotypic changes such as the accumulation of persistent DNA damage, senescence-associated β-galactosidase, p16 INK4A, and/or telomere shortening |

Cellular senescence is a striking feature

of WS patient cells. WRN deficiency increased the accumulation of persistent DNA damage, p16, and senescence- associated β-galactosidase. |

Norwood

et al.

73

Lu et al. 13 |

|

Deregulated

nutrient sensing |

Somatotropic axis essentially consisting of growth

hormone, insulin-like growth factors (IGF-1 and II), and their carrier proteins and receptors regulates metabolism in mammals. In addition to insulin–IGF-1 (IIS) signaling pathway, which senses glucose, three interconnected nutrient sensing systems are associated with aging. The mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) senses high amino acid concentrations, AMPK (5′- adenosine monophosphate [AMP]-activated protein kinase) senses low-energy states by detecting high AMP levels, and sirtuins sense low-energy states by detecting high NAD + levels. With aging, IIS pathway decreases, mTOR activity increases, AMPK upregulates in skeletal muscles, and sirtuins are downregulated. |

WRN protects against starvation-induced

autophagy. Further research is required to elaborate the role of WRN in regulating nutrient-sensing mechanisms. |

Maity et al. 17 |

|

Stem cell

exhaustion |

A decline in the proliferation of stem and progenitor

cells, which are required for tissue regeneration |

WRN-deficient mesenchymal stem cells

showed progressive disorganization of heterochromatin and premature senescence. |

Zhang et al. 14 |

|

Altered

intercellular communication |

Enhanced activation of nuclear factor kappa

B (NF-κB) and increased production of tumor necrosis factor (TNF), interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β), and cytokines resulting in age-associated alteration in intercellular communication. Accumulation of pro-inflammatory tissue damage, failure of immune system to clear pathogens and dysfunctional host cells, and occurrence of defective autophagy response. Bystander effect in which senescent cells induce senescence in neighboring cells via gap junction–mediated cell-cell contacts and ROS. |

Patients with WS have elevated

levels of inflammation-driven aging- associated cytokines (IL-4, IL-6, IL-10, granulocyte macrophage colony- stimulating factor [GM-CSF], IL-2, TNF- α, interferon gamma [IFNγ], monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 [MCP-1], and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor [G- CSF]) compared with normal individuals. |

Goto et al. 18 |

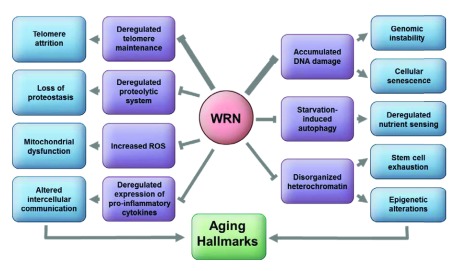

Aging research has enumerated nine hallmarks of aging: genomic instability, telomere attrition, epigenetic alterations, loss of proteostasis, deregulated nutrient sensing, mitochondrial dysfunction, cellular senescence, stem cell exhaustion, and altered intercellular communication ( Table 1) 7. Patients with WS have defects in DNA repair machinery and show genomic instability 8, 9. WRN, in association with the telomere-protecting shelterin complex, promotes telomere maintenance, and loss of WRN, as seen in vitro and in patients with WS, results in the rapid decline of telomere length 10, 11. A progressive increase in DNA methylation is considered an aging biomarker, and, consistent with this, patients with WS display increased epigenetic age 12. Increased DNA damage accumulation, genomic instability, telomere attrition, and histone methylation are contributing factors for cellular senescence and stem cell exhaustion in WS 13, 14. Although extensive research is required to sort out the molecular functions of WRN in regulating proteostasis, nutrient sensing, and mitochondria, WS is phenotypically associated with a loss in proteostasis and mitochondrial dysfunction 15, 16. WRN protects cells from starvation-induced autophagy, which is deregulated by an imbalance in nutrient-sensing mechanisms 17. Inflammation alters intercellular communication owing to the accumulation of cytokines increasing with aging. Patients with WS have elevated cytokine levels of interleukin-2 (IL-2), IL-4, IL-6, tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), interferon gamma (IFNγ), and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) 18.

In the past five years, there have been a large number of studies on WS, covering areas including those discussed in Table 1. Here, we discuss some areas of particular relevance where significant insight has been gathered in recent years. These include the role of WRN in DNA double-strand break (DSB) repair, telomere maintenance, senescence and heterochromatin stabilization, and cancer. We will discuss these selected areas in depth below.

WRN regulates double-strand break repair pathway choice

The human genome is under constant exposure to exogenous and endogenous agents. DSBs are among the most potent and deleterious forms of cellular DNA damage, causing mutagenic changes, developmental defects, gross chromosomal rearrangements, cell death, and malignancy 19. Approximately 10 to 50 DSBs are being formed per cell per day 20. DSBs are mainly detected, processed, and repaired by two pathways: homologous recombination (HR) and non-homologous end joining (NHEJ). The choice of DNA repair pathway is tightly regulated and associated with the cell cycle. While NHEJ is active throughout the cell cycle, DSBs in S and G 2 phases are preferably repaired by HR using the intact sister chromatid. WRN recruits to DSB sites in G 1 as well as in S and G 2 phases 21. The DSB sensor protein complexes Ku70/80 and MRN (MRE11, RAD50, NBS1) initiate NHEJ and HR pathways, respectively. The HR pathway is a high-fidelity DNA repair mechanism. In contrast, the NHEJ pathway is an error-prone mechanism where the DSBs are processed and ligated without relying on sequence homology 22. Despite its error-prone nature, NHEJ is the predominant form of DSB repair in human somatic cells. In addition to these DSB repair pathways, error-prone alternative (alt)-NHEJ and single-strand annealing also operate under various conditions 22.

WRN mainly localizes to the nucleolus, and then translocates to DSBs, when introduced. The acetylation of WRN by CBP/p300 affects its subcellular distribution, and deacetylation mediated by Sirt1 affects its translocation to the nucleolus 23, 24. In response to DNA damage, WRN interacts with several proteins that participate in HR, NHEJ, and single-strand annealing 6. Recent advances in DSB repair suggest the existence of two distinct mechanisms of NHEJ: classical/canonical (c)-NHEJ and alt-NHEJ 25. Alt-NHEJ is distinguished from c-NHEJ by the participating proteins, DSB resection, and the use of microhomology during end joining. The essential factors involved in c-NHEJ include Ku70/80 heterodimer, DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit (DNA-PKcs), and XRCC4/ligase IV (X4L4) complex. Alt-NHEJ mainly acts as a backup pathway to c-NHEJ and operates as a major pathway of DSB repair in Ku70/80-deficient cells and ligase IV-deficient cells 26, 27. Alt-NHEJ depends on proteins that participate in HR; however, the pathway does not depend on a homologous sister chromatid. MRE11, PARP1, CtIP, DNA ligase I, and DNA ligase III all promote alt-NHEJ 28– 30. Research from our lab and others identified physical interactions of WRN with Ku70/80, DNA-PKcs, X4L4, PARP1, DNA ligase I, DNA ligase III, and MRN 31– 37.

The Ku70/80 heterodimer in association with DNA-PKcs initiates a cascade of events that constitutes the c-NHEJ pathway 38. The Ku70/80 complex interacts directly with WRN and stimulates its exonuclease activity 31, 39. WRN has two putative Ku-binding motifs, one in the N-terminus and another in the C-terminus, which accelerate DSB repair. The N-terminal Ku-binding motif mediates Ku-dependent stimulation of WRN exonuclease activity 40. DNA-PKcs, which gains robust kinase activity by interacting with DSB-bound Ku70/80, phosphorylates WRN at S440 and S467 positions and regulates WRN’s enzymatic activities 32, 41, 42. With its nuclease activity, WRN processes DNA ends and generates substrates suitable for ligation mediated by the X4L4 complex 33. Ku-mediated c-NHEJ dominates over all other DSB repair pathways, while alt-NHEJ is the default DNA repair pathway in Ku-deficient cells or under conditions that inhibit c-NHEJ 43. WRN’s role in DSB repair pathways is complex; however, findings clearly demonstrate that WRN stimulates c-NHEJ with its enzymatic activities and inhibits alt-NHEJ with its non-enzyme functions 21.

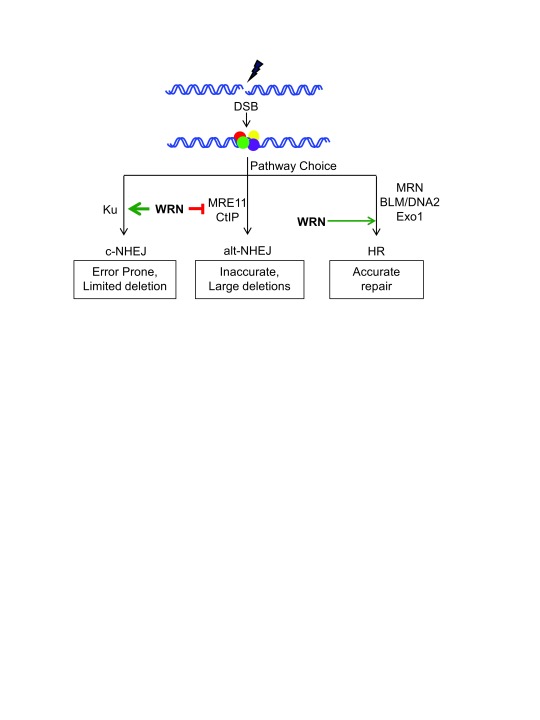

The accurate repair of DSBs depends on the regulation of end processing. Resection of DSBs is very limited during c-NHEJ and is extensive during HR and alt-NHEJ. End resection is carried out in a two-step process: initial resection (short-range), which is regulated by MRN complex with CtIP, and extended resection (long-range) performed by DNA2/BLM or EXO1 44. End resection during HR and alt-NHEJ is initiated by MRE11 in association with CtIP. Interestingly, WRN actively restrains 5′-3′ end resection by inhibiting the recruitment of MRE11 and CtIP to DSBs, specifically in G 1 phase. Consequently, alt-NHEJ is upregulated in WS cells and WRN-deficient cells, resulting in telomere fusions. Consistent with this finding, the inhibition of alt-NHEJ by downregulation of CtIP suppresses telomere fusions in WRN-deficient cells 21. WRN has also recently been shown to inhibit MRE11/Exo1-dependent end resection and generation of single-stranded DNA in camptothecin (CPT)-treated cells 45. CPT is an anti-cancer agent which blocks replication and induces WRN degradation 46, 47. Replication fork progression in CPT-treated (low-dose) WS cells was rescued by expressing wild-type WRN 42, and the exonuclease activity of WRN was required to protect DSBs at replication forks from MRE11-dependent processing 45. WRN and DNA2 physically interact with each other and coordinate their enzyme activities to promote double-stranded DNA degradation and resection 48, 49. Interestingly, the phosphorylation of WRN at S1133 by cyclin-dependent kinase 1 (CDK1), which occurs during late S/G 2 and M phases, regulates DSB repair pathway choice between HR and NHEJ 50. Taken together, WRN plays a major role in DSB repair pathway choice ( Figure 1).

Figure 1. Double-strand break (DSB) repair pathway choice.

DSBs generated by extrinsic and intrinsic factors are recognized by the sensor proteins Ku70/Ku80, WRN, MRN, and PARP1 to mediate repair. DSBs are repaired via classical/canonical non-homologous end joining (c-NHEJ), alternative (alt)-NHEJ, and homologous recombination (HR) pathways. WRN promotes Ku-dependent c-NHEJ with its catalytic activities and strongly inhibits alt-NHEJ with its non-catalytic activities. WRN suppresses the recruitment and downstream functions of MRE11 and CtIP to inhibit alt-NHEJ. During S/G 2 phases of the cell cycle, WRN promotes HR. Accurate repair of DSBs is required for genome stability without loss of genetic information.

Telomere maintenance

Chromosome ends, the telomeres, are unique DNA structures that must be replicated and protected. Human telomeres are approximately 11–15 kilobases in length and composed of about 2,500 repeats of TTAGGG sequence followed by a single-stranded 3′ tail region of the same sequence. With age, telomere length is reduced mainly owing to end-replication problems. Telomeres are packed into protein-DNA complexes with the aid of shelterin proteins. We and others have previously shown that WRN interacts with TRF1, TRF2, and POT1 components of the shelterin complex 11, 51– 53.

Several lines of evidence suggest that telomere dysfunction contributes to WS pathology. Cells from WS patients and WRN-deficient cells undergo early replicative senescence and display telomere loss and chromosomal rearrangements. Telomere fusions and chromosome translocations are also well documented in WS patient and WRN-deficient mouse cells 54– 58. Importantly, re-introduction of telomerase activity into WS cells prevents senescence and telomere loss 54, 59. Additionally, although the WRN protein is ubiquitously expressed, WS patient cells preferentially display premature aging of mesenchymal cells 60. Reprogramming of induced pluripotent WS stem cells has reinforced the importance of the roles WRN plays in telomere maintenance because differentiation into any cell which naturally expresses telomerase extends the proliferative capacity of WS cells 61. A Wrn-null mouse model further substantiates the importance of WRN in telomere maintenance. These mice failed to show significant pathology until bred with late-generation telomerase-deficient mice, demonstrating that short telomeres were critical to revealing WS-like premature aging features 62, 63.

WRN acts at telomeres to promote replication and suppress recombination. Cells use telomerase, a reverse transcriptase enzyme with an RNA component, Terc, to replicate and lengthen telomeres. It is thought that WRN’s helicase activity contributes to telomere replication through the resolution or dissolution of complex DNA structures found at telomeres such as T-loops, D-loops, and G-quartets (G4s) 11, 64– 66. G4s are formed by four guanines associated through Hoogsteen base pairing. They are thought to arise in areas of single-stranded DNA, in regions undergoing replication and transcription, and preferentially in the telomeric G-rich strand. G4s may promote genomic instability; therefore, enzymes, like WRN, exist to unwind them, thereby suppressing recombination 66– 69.

In the absence of telomerase, cells maintain their telomeres via recombination mechanisms termed alternative lengthening of telomeres (ALT). ALT cells and cells without WRN protein show increases in telomere-sister chromatid exchanges 21, 56, 70. This increase has been, in part, attributed to a rise in alt-NHEJ in WRN-deficient cells 21. Interestingly, knockdown of WRN in three different ALT cell lines demonstrated variable dependence on WRN to prevent telomere loss 71. This suggests that there are multiple telomerase-independent mechanisms that contribute to telomere maintenance.

Although it is routinely reported that skin cells from patients with WS have shorter telomere length 10, it is still debated whether this is true in all organs and how it contributes to the pathology found in patients with WS. In one study of two patients with WS at autopsy, the authors did not find substantially shorter telomeres from the liver relative to controls 72. However, the liver is considered a regenerative organ and therefore may have the capacity to re-activate telomerase in this tissue, negating the impact of WRN loss. In another recent study, younger WS patients with intractable ulcers had normal terminal restriction fragment lengths, suggesting that telomere length was not likely driving this phenotype 10. While the prevailing theory is that telomere-driven replicative senescence promotes pathology in WS, this may need to be revised as we learn more about telomeres in different organs from patients with WS.

Epigenetic modification and senescence

In vitro, premature cellular senescence is a striking feature of WRN-deficient cells 73. Senescent cells are defined as viable growth-arrested cells. Senescence and exhaustion of stem cells are thought to contribute to tissue degeneration and aging. There are many actions which induce cellular senescence: extended cellular division, oncogene activation, telomere attrition, and exposure to DNA-damaging agents 74. Senescent cells typically have an altered appearance and elevated secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines which promote inflammation 75. Until recently, cellular senescence in WRN-deficient cells was believed to be due to telomere issues and the accumulation of replication-associated endogenous DNA damage.

The genome-wide distribution of histone methylation marks changes during aging 76. Consistent with WS as an aging model, patients with WS display increased epigenetic age as measured by DNA methylation of known aging biomarkers 12. In humans, H3K9 trimethylation (H3K9me3) denotes constitutive heterochromatin and is mainly methylated by SUV39H1/2 histone methyltransferase (HMTase) 77. Though not fully characterized, loss of heterochromatin is considered to increase the susceptibility of genomic DNA to mutations and reduce transcriptional precision, both of which promote genomic instability during aging 76. Interestingly, Zhang et al. 14 reported that WRN exists in complex with SUV39H1, HP1α, and LAP2β, which together are responsible for the epigenetic histone mark H3K9me3. WRN also interacts with the chromatin remodeling chaperone chromatin assembly factor 1 (CAF-1) 78, which deposits histones H3 and H4 onto newly replicated DNA 79. In response to DNA damage, WRN recruits CAF-1 and participates in chromatin structure restoration 78.

In stem cells, the histone methylation pattern is preserved over generations and is associated with the maintenance of stem cell potential. Mesenchymal stem cells differentiated from WRN-null embryonic stem cells display genome-wide reductions in H3K9me3 levels contributing to heterochromatin disorganization and stem cell exhaustion 14. Specifically, the loss of WRN resulted in loss of heterochromatin in subtelomeric and subcentromeric regions and altered the transcription of repetitive satellite DNA. Since epigenetic changes are a known hallmark of aging, Zhang et al. tested whether disorganized heterochromatin could induce cellular senescence 14. Disorganized heterochromatin, without concomitant DNA damage, does in fact induce cellular senescence, and restoration of heterochromatin suppresses the senescence phenotype. Thus, the authors suggested that WRN participates in heterochromatin stability and demonstrated that heterochromatin disorganization is yet another mechanism whereby WRN deficiency can promote cellular senescence and aging.

Attempts to safely destroy senescent cells is a burgeoning field and one in which patients with WS may derive benefits. Since replicative senescence is a classic feature of WS cells, several groups are using WS cells to identify and characterize anti-senescent agents. An inhibitor of p38, a mitogen-activated protein kinase, improved replication capacity in WS fibroblasts 80, 81. Rapamycin, a mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) kinase inhibitor, decreased 53BP1 foci, a marker for DNA damage, and increased proliferation in WRN-knockdown cells after long-term treatment 82. Rapamycin and hydrogen sulfide both have been shown to decrease senescence in WS patient cells, perhaps through Sirt1, although this needs further investigation 83. Translational applications developed from WRN-deficient systems may not only benefit patients with WS but also provide insight into basic mechanisms of aging.

WRN in cancer research

WRN promotes DNA repair and genome stability, and consequently patients with WS are predisposed to various cancers. The most common neoplasia in patients with WS are thyroid cancer, malignant melanoma, meningioma, soft tissue sarcoma, osteosarcoma, breast cancer, and leukemias 84, 85. Additionally, there is a higher prevalence of mesenchymal or non-epithelial malignancies (that is, so-called sarcomas) in patients with WS in contrast to normal older individuals who usually develop malignancies of epithelial origin. It is widely believed that WRN functions as a tumor suppressor gene. Although patients with WS develop various cancers, limited studies have been conducted to correlate WRN mutations in cancers in non-WS individuals. Interestingly, race-specific mutations in WRN were found to be associated with increased breast cancer risk. Breast cancer risk was increased by the Cys1367Arg mutation in German and Austrian populations and by the Phe1074Leu mutation in Taiwanese and Chinese populations 86– 89.

Primary tumors of colorectal cancer patients and cell lines display decreased WRN mRNA and protein expression 90, 91; however, no WRN mutations have been associated with colorectal cancer risk 92, 93. Irinotecan (CPT-11), a semi-synthetic derivative of CPT, which is routinely used in colorectal cancer therapy, enhances the survival of colorectal cancer patients with hypermethylated WRN promoter 90. In contrast, Bosch et al. reported that hypermethylation of the WRN promoter does not have predictive value for personalized irinotecan-based therapy 91. The observed differences could be due to the complex nature of promoter hypermethylation and varied expression of WRN. CPT and its derivatives inhibit DNA topoisomerase I (Top1) and generate DSBs during replication. WRN physically and functionally interacts with Top1, and WRN helps in resolving CPT-induced DNA lesions. Furthermore, the ectopic expression of WRN inhibits CPT-induced cellular senescence, cell death, and enhanced replication fork recovery and DSB repair 45, 46, 48. Interestingly, recent studies suggest that CPT induces WRN and Top1 degradation via the ubiquitin proteasome pathway 46, 47. CPT-induced WRN degradation, but not Top1 degradation, was found specifically in CPT-sensitive cells 30. Thus, it is possible that WRN expression or degradation (or both) could be used as a biomarker for personalized chemotherapy, and further research should explore this potential.

Conclusions and future perspectives

As shown in Table 1, many of the hallmarks of aging are found in patients with WS and altered as a direct consequence of WRN loss. Although there is strong evidence for a role for WRN in several of the pathways ( Figure 2), others show a weak association and need further investigation. Patients with WS display many aging features, but the initiating pathology for most is still not known. For example, patients with WS suffer from severe intractable foot ulcers; however, the underlying pathology has yet to be understood. Cataracts are another cardinal feature found in patients with WS, but the mechanism or mechanisms instigating cataracts in patients with WS have to be identified. Age-associated cataracts occur because of an imbalance in the proteostasis in the lens cells 94; perhaps a similar mechanism is at play in WS. Recent studies suggest that WRN regulates cellular functions, like DSB repair, via catalytic and non-catalytic functions. Further investigations into its catalytic and non-catalytic functions may help elucidate disease pathology. Additional research is also needed to further define the specific functions for the exonuclease and helicase domains and to understand why these two activities are present in the same protein. They may cooperate in some pathways such as base excision repair 95 or telomere maintenance 11 or they may not. Model organisms may be of benefit in this research because not all species express both the helicase and the exonuclease from one gene. In Caenorhabditis elegans and Drosophila, the two domains are expressed from separate genes. Additionally, the analysis of WRN functions in model organisms will help identify conserved and divergent WRN roles over an organism’s life span.

Figure 2. The role of WRN in the contexts of the known hallmarks of aging 7.

The widths of the lines showing inhibition indicate the estimated relative involvement of WRN in the processes. ROS, reactive oxygen species.

Mammals have five RecQ helicases; it is important to dissect out why and how they cooperate in genome maintenance. Mutations in three of the five human RecQ helicases cause unique syndromes, indicating that they have non-overlapping functions. Patients with WS are affected by certain types of cancers compared with patients with Bloom and Rothmund-Thomson syndrome. Studies identifying the mechanisms behind the susceptibility of these patients to certain type of cancers are still needed. Furthermore, the reason why patients with WS are prone to non-epithelial malignant tumors remains to be determined.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to our past and present colleagues for sharing insights and stimulating discussions. We thank Tyler Demarest and Sanket Awate for their suggestions on the manuscript.

Editorial Note on the Review Process

F1000 Faculty Reviews are commissioned from members of the prestigious F1000 Faculty and are edited as a service to readers. In order to make these reviews as comprehensive and accessible as possible, the referees provide input before publication and only the final, revised version is published. The referees who approved the final version are listed with their names and affiliations but without their reports on earlier versions (any comments will already have been addressed in the published version).

The referees who approved this article are:

Koutaro Yokote, Department of Clinical Cell Biology and Medicine‚ Graduate School of Medicine, Chiba University, Chiba, Japan

Junko Oshima, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, USA

Asaithamby Aroumougame, Department of Radiation Oncology, University of Texas Health Science Center at Dallas, Dallas, Texas, USA

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Aging.

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

[version 1; referees: 3 approved]

References

- 1. Yokote K, Chanprasert S, Lee L, et al. : WRN Mutation Update: Mutation Spectrum, Patient Registries, and Translational Prospects. Hum Mutat. 2017;38(1):7–15. 10.1002/humu.23128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 2. Masala MV, Scapaticci S, Olivieri C, et al. : Epidemiology and clinical aspects of Werner's syndrome in North Sardinia: description of a cluster. Eur J Dermatol. 2007;17(3):213–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Nakura J, Wijsman EM, Miki T, et al. : Homozygosity mapping of the Werner syndrome locus (WRN). Genomics. 1994;23(3):600–8. 10.1006/geno.1994.1548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Takemoto M, Mori S, Kuzuya M, et al. : Diagnostic criteria for Werner syndrome based on Japanese nationwide epidemiological survey. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2013;13(2):475–81. 10.1111/j.1447-0594.2012.00913.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yamaga M, Takemoto M, Shoji M, et al. : Werner syndrome: a model for sarcopenia due to accelerated aging. Aging (Albany NY). 2017;9(7):1738–44. 10.18632/aging.101265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 6. Croteau DL, Popuri V, Opresko PL, et al. : Human RecQ helicases in DNA repair, recombination, and replication. Annu Rev Biochem. 2014;83:519–52. 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060713-035428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. López-Otín C, Blasco MA, Partridge L, et al. : The hallmarks of aging. Cell. 2013;153(6):1194–217. 10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 8. Salk D, Au K, Hoehn H, et al. : Evidence of clonal attenuation, clonal succession, and clonal expansion in mass cultures of aging Werner's syndrome skin fibroblasts. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 1981;30(2):108–17. 10.1159/000131597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chen L, Huang S, Lee L, et al. : WRN, the protein deficient in Werner syndrome, plays a critical structural role in optimizing DNA repair. Aging Cell. 2003;2(4):191–9. 10.1046/j.1474-9728.2003.00052.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ishikawa N, Nakamura K, Izumiyama-Shimomura N, et al. : Accelerated in vivo epidermal telomere loss in Werner syndrome. Aging (Albany NY). 2011;3(4):417–29. 10.18632/aging.100315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Opresko PL, Otterlei M, Graakjaer J, et al. : The Werner syndrome helicase and exonuclease cooperate to resolve telomeric D loops in a manner regulated by TRF1 and TRF2. Mol Cell. 2004;14(6):763–74. 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.05.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Maierhofer A, Flunkert J, Oshima J, et al. : Accelerated epigenetic aging in Werner syndrome. Aging (Albany NY). 2017;9(4):1143–52. 10.18632/aging.101217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 13. Lu H, Fang EF, Sykora P, et al. : Senescence induced by RECQL4 dysfunction contributes to Rothmund-Thomson syndrome features in mice. Cell Death Dis. 2014;5:e1226. 10.1038/cddis.2014.168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zhang W, Li J, Suzuki K, et al. : Aging stem cells. A Werner syndrome stem cell model unveils heterochromatin alterations as a driver of human aging. Science. 2015;348(6239):1160–3. 10.1126/science.aaa1356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 15. Zhu X, Zhang G, Kang L, et al. : Epigenetic Regulation of Werner Syndrome Gene in Age-Related Cataract. J Ophthalmol. 2015;2015:579695. 10.1155/2015/579695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 16. Cogger VC, Svistounov D, Warren A, et al. : Liver aging and pseudocapillarization in a Werner syndrome mouse model. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2014;69(9):1076–86. 10.1093/gerona/glt169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Maity J, Bohr VA, Laskar A, et al. : Transient overexpression of Werner protein rescues starvation induced autophagy in Werner syndrome cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1842(12 Pt A):2387–94. 10.1016/j.bbadis.2014.09.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Goto M, Hayata K, Chiba J, et al. : Multiplex cytokine analysis of Werner syndrome. Intractable Rare Dis Res. 2015;4(4):190–7. 10.5582/irdr.2015.01035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 19. Jackson SP, Bartek J: The DNA-damage response in human biology and disease. Nature. 2009;461(7267):1071–8. 10.1038/nature08467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Vilenchik MM, Knudson AG: Endogenous DNA double-strand breaks: production, fidelity of repair, and induction of cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(22):12871–6. 10.1073/pnas.2135498100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Shamanna RA, Lu H, de Freitas JK, et al. : WRN regulates pathway choice between classical and alternative non-homologous end joining. Nat Commun. 2016;7:13785. 10.1038/ncomms13785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ceccaldi R, Rondinelli B, D'Andrea AD: Repair Pathway Choices and Consequences at the Double-Strand Break. Trends Cell Biol. 2016;26(1):52–64. 10.1016/j.tcb.2015.07.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 23. Blander G, Zalle N, Daniely Y, et al. : DNA damage-induced translocation of the Werner helicase is regulated by acetylation. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(52):50934–40. 10.1074/jbc.M210479200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Li K, Casta A, Wang R, et al. : Regulation of WRN protein cellular localization and enzymatic activities by SIRT1-mediated deacetylation. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(12):7590–8. 10.1074/jbc.M709707200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chang HHY, Pannunzio NR, Adachi N, et al. : Non-homologous DNA end joining and alternative pathways to double-strand break repair. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2017;18(8):495–506. 10.1038/nrm.2017.48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 26. Wang H, Perrault AR, Takeda Y, et al. : Biochemical evidence for Ku-independent backup pathways of NHEJ. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31(18):5377–88. 10.1093/nar/gkg728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kabotyanski EB, Gomelsky L, Han JO, et al. : Double-strand break repair in Ku86- and XRCC4-deficient cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26(23):5333–42. 10.1093/nar/26.23.5333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Xie A, Kwok A, Scully R: Role of mammalian Mre11 in classical and alternative nonhomologous end joining. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009;16(8):814–8. 10.1038/nsmb.1640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wang M, Wu W, Wu W, et al. : PARP-1 and Ku compete for repair of DNA double strand breaks by distinct NHEJ pathways. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34(21):6170–82. 10.1093/nar/gkl840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bennardo N, Cheng A, Huang N, et al. : Alternative-NHEJ is a mechanistically distinct pathway of mammalian chromosome break repair. PLoS Genet. 2008;4(6):e1000110. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Cooper MP, Machwe A, Orren DK, et al. : Ku complex interacts with and stimulates the Werner protein. Genes Dev. 2000;14(8):907–12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Karmakar P, Piotrowski J, Brosh RM, Jr, et al. : Werner protein is a target of DNA-dependent protein kinase in vivo and in vitro, and its catalytic activities are regulated by phosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(21):18291–302. 10.1074/jbc.M111523200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kusumoto R, Dawut L, Marchetti C, et al. : Werner protein cooperates with the XRCC4-DNA ligase IV complex in end-processing. Biochemistry. 2008;47(28):7548–56. 10.1021/bi702325t [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lebel M, Lavoie J, Gaudreault I, et al. : Genetic cooperation between the Werner syndrome protein and poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 in preventing chromatid breaks, complex chromosomal rearrangements, and cancer in mice. Am J Pathol. 2003;162(5):1559–69. 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64290-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sallmyr A, Tomkinson AE, Rassool FV: Up-regulation of WRN and DNA ligase IIIalpha in chronic myeloid leukemia: consequences for the repair of DNA double-strand breaks. Blood. 2008;112(4):1413–23. 10.1182/blood-2007-07-104257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lachapelle S, Gagné JP, Garand C, et al. : Proteome-wide identification of WRN-interacting proteins in untreated and nuclease-treated samples. J Proteome Res. 2011;10(3):1216–27. 10.1021/pr100990s [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Cheng WH, von Kobbe C, Opresko PL, et al. : Linkage between Werner syndrome protein and the Mre11 complex via Nbs1. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(20):21169–76. 10.1074/jbc.M312770200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Walker JR, Corpina RA, Goldberg J: Structure of the Ku heterodimer bound to DNA and its implications for double-strand break repair. Nature. 2001;412(6847):607–14. 10.1038/35088000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 39. Li B, Comai L: Functional interaction between Ku and the werner syndrome protein in DNA end processing. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(37):28349–52. 10.1074/jbc.C000289200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Grundy GJ, Rulten SL, Arribas-Bosacoma R, et al. : The Ku-binding motif is a conserved module for recruitment and stimulation of non-homologous end-joining proteins. Nat Commun. 2016;7:11242. 10.1038/ncomms11242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 41. Yannone SM, Roy S, Chan DW, et al. : Werner syndrome protein is regulated and phosphorylated by DNA-dependent protein kinase. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(41):38242–8. 10.1074/jbc.M101913200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kusumoto-Matsuo R, Ghosh D, Karmakar P, et al. : Serines 440 and 467 in the Werner syndrome protein are phosphorylated by DNA-PK and affects its dynamics in response to DNA double strand breaks. Aging (Albany NY). 2014;6(1):70–81. 10.18632/aging.100629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Keijzers G, Maynard S, Shamanna RA, et al. : The role of RecQ helicases in non-homologous end-joining. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2014;49(6):463–72. 10.3109/10409238.2014.942450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Cejka P: DNA End Resection: Nucleases Team Up with the Right Partners to Initiate Homologous Recombination. J Biol Chem. 2015;290(38):22931–8. 10.1074/jbc.R115.675942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 45. Iannascoli C, Palermo V, Murfuni I, et al. : The WRN exonuclease domain protects nascent strands from pathological MRE11/EXO1-dependent degradation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(20):9788–803. 10.1093/nar/gkv836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 46. Shamanna RA, Lu H, Croteau DL, et al. : Camptothecin targets WRN protein: mechanism and relevance in clinical breast cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7(12):13269–84. 10.18632/oncotarget.7906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Su F, Bhattacharya S, Abdisalaam S, et al. : Replication stress induced site-specific phosphorylation targets WRN to the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Oncotarget. 2016;7(1):46–65. 10.18632/oncotarget.6659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Sturzenegger A, Burdova K, Kanagaraj R, et al. : DNA2 cooperates with the WRN and BLM RecQ helicases to mediate long-range DNA end resection in human cells. J Biol Chem. 2014;289(39):27314–26. 10.1074/jbc.M114.578823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Pinto C, Kasaciunaite K, Seidel R, et al. : Human DNA2 possesses a cryptic DNA unwinding activity that functionally integrates with BLM or WRN helicases. eLife. 2016;5: pii: e18574. 10.7554/eLife.18574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Palermo V, Rinalducci S, Sanchez M, et al. : CDK1 phosphorylates WRN at collapsed replication forks. Nat Commun. 2016;7:12880. 10.1038/ncomms12880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 51. Opresko PL, von Kobbe C, Laine JP, et al. : Telomere-binding protein TRF2 binds to and stimulates the Werner and Bloom syndrome helicases. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(43):41110–9. 10.1074/jbc.M205396200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Machwe A, Xiao L, Orren DK: TRF2 recruits the Werner syndrome (WRN) exonuclease for processing of telomeric DNA. Oncogene. 2004;23(1):149–56. 10.1038/sj.onc.1206906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Opresko PL, Mason PA, Podell ER, et al. : POT1 stimulates RecQ helicases WRN and BLM to unwind telomeric DNA substrates. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(37):32069–80. 10.1074/jbc.M505211200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Crabbe L, Jauch A, Naeger CM, et al. : Telomere dysfunction as a cause of genomic instability in Werner syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(7):2205–10. 10.1073/pnas.0609410104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Melcher R, von Golitschek R, Steinlein C, et al. : Spectral karyotyping of Werner syndrome fibroblast cultures. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 2000;91(1–4):180–5. 10.1159/000056841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Laud PR, Multani AS, Bailey SM, et al. : Elevated telomere-telomere recombination in WRN-deficient, telomere dysfunctional cells promotes escape from senescence and engagement of the ALT pathway. Genes Dev. 2005;19(21):2560–70. 10.1101/gad.1321305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Oshima J, Huang S, Pae C, et al. : Lack of WRN results in extensive deletion at nonhomologous joining ends. Cancer Res. 2002;62(2):547–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Fukuchi K, Martin GM, Monnat RJ, Jr: Mutator phenotype of Werner syndrome is characterized by extensive deletions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86(15):5893–7. 10.1073/pnas.86.15.5893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Grandori C, Wu KJ, Fernandez P, et al. : Werner syndrome protein limits MYC-induced cellular senescence. Genes Dev. 2003;17(13):1569–74. 10.1101/gad.1100303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 60. Ibrahim B, Sheerin AN, Jennert-Burston K, et al. : Absence of premature senescence in Werner's syndrome keratinocytes. Exp Gerontol. 2016;83:139–47. 10.1016/j.exger.2016.07.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 61. Shimamoto A, Yokote K, Tahara H: Werner Syndrome-specific induced pluripotent stem cells: recovery of telomere function by reprogramming. Front Genet. 2015;6:10. 10.3389/fgene.2015.00010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 62. Lombard DB, Beard C, Johnson B, et al. : Mutations in the WRN gene in mice accelerate mortality in a p53-null background. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20(9):3286–91. 10.1128/MCB.20.9.3286-3291.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Chang S, Multani AS, Cabrera NG, et al. : Essential role of limiting telomeres in the pathogenesis of Werner syndrome. Nat Genet. 2004;36(8):877–82. 10.1038/ng1389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 64. Nora GJ, Buncher NA, Opresko PL: Telomeric protein TRF2 protects Holliday junctions with telomeric arms from displacement by the Werner syndrome helicase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38(12):3984–98. 10.1093/nar/gkq144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Damerla RR, Knickelbein KE, Strutt S, et al. : Werner syndrome protein suppresses the formation of large deletions during the replication of human telomeric sequences. Cell Cycle. 2012;11(16):3036–44. 10.4161/cc.21399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Johnson JE, Cao K, Ryvkin P, et al. : Altered gene expression in the Werner and Bloom syndromes is associated with sequences having G-quadruplex forming potential. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38(4):1114–22. 10.1093/nar/gkp1103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Tang W, Robles AI, Beyer RP, et al. : The Werner syndrome RECQ helicase targets G4 DNA in human cells to modulate transcription. Hum Mol Genet. 2016;25(10):2060–9. 10.1093/hmg/ddw079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 68. Tippana R, Hwang H, Opresko PL, et al. : Single-molecule imaging reveals a common mechanism shared by G-quadruplex-resolving helicases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113(30):8448–53. 10.1073/pnas.1603724113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Tarsounas M, Tijsterman M: Genomes and G-quadruplexes: for better or for worse. J Mol Biol. 2013;425(23):4782–9. 10.1016/j.jmb.2013.09.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Londoño-Vallejo JA, Der-Sarkissian H, Cazes L, et al. : Alternative lengthening of telomeres is characterized by high rates of telomeric exchange. Cancer Res. 2004;64(7):2324–7. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-4035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Gocha ARS, Acharya S, Groden J: WRN loss induces switching of telomerase-independent mechanisms of telomere elongation. PLoS One. 2014;9(4):e93991. 10.1371/journal.pone.0093991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Tokita M, Kennedy SR, Risques RA, et al. : Werner syndrome through the lens of tissue and tumour genomics. Sci Rep. 2016;6:32038. 10.1038/srep32038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 73. Norwood TH, Hoehn H, Salk D, et al. : Cellular aging in Werner's syndrome: a unique phenotype? J Invest Dermatol. 1979;73(1):92–6. 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12532778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Rodier F, Campisi J: Four faces of cellular senescence. J Cell Biol. 2011;192(4):547–56. 10.1083/jcb.201009094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Freund A, Orjalo AV, Desprez P, et al. : Inflammatory networks during cellular senescence: causes and consequences. Trends Mol Med. 2010;16(5):238–46. 10.1016/j.molmed.2010.03.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Benayoun BA, Pollina EA, Brunet A: Epigenetic regulation of ageing: linking environmental inputs to genomic stability. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2015;16(10):593–610. 10.1038/nrm4048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 77. Peters AH, O'Carroll D, Scherthan H, et al. : Loss of the Suv39h histone methyltransferases impairs mammalian heterochromatin and genome stability. Cell. 2001;107(3):323–37. 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00542-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 78. Jiao R, Harrigan JA, Shevelev I, et al. : The Werner syndrome protein is required for recruitment of chromatin assembly factor 1 following DNA damage. Oncogene. 2007;26(26):3811–22. 10.1038/sj.onc.1210150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Smith S, Stillman B: Purification and characterization of CAF-I, a human cell factor required for chromatin assembly during DNA replication in vitro. Cell. 1989;58(1):15–25. 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90398-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Tivey HS, Brook AJ, Rokicki MJ, et al. : p38 MAPK stress signalling in replicative senescence in fibroblasts from progeroid and genomic instability syndromes. Biogerontology. 2013;14(1):47–62. 10.1007/s10522-012-9407-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Davis T, Brook AJ, Rokicki MJ, et al. : Evaluating the Role of p38 MAPK in the Accelerated Cell Senescence of Werner Syndrome Fibroblasts. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2016;9: pii: E23. 10.3390/ph9020023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 82. Talaei F, van Praag VM, Henning RH: Hydrogen sulfide restores a normal morphological phenotype in Werner syndrome fibroblasts, attenuates oxidative damage and modulates mTOR pathway. Pharmacol Res. 2013;74:34–44. 10.1016/j.phrs.2013.04.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Saha B, Cypro A, Martin GM, et al. : Rapamycin decreases DNA damage accumulation and enhances cell growth of WRN-deficient human fibroblasts. Aging Cell. 2014;13(3):573–5. 10.1111/acel.12190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Lauper JM, Krause A, Vaughan TL, et al. : Spectrum and risk of neoplasia in Werner syndrome: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2013;8(4):e59709. 10.1371/journal.pone.0059709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Sugimoto M, Furuichi Y, Ide T, et al. : Involvement of WRN helicase in immortalization and tumorigenesis by the telomeric crisis pathway (Review). Oncol Lett. 2011;2(4):609–11. 10.3892/ol.2011.298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Wirtenberger M, Frank B, Hemminki K, et al. : Interaction of Werner and Bloom syndrome genes with p53 in familial breast cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2006;27(8):1655–60. 10.1093/carcin/bgi374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Zins K, Frech B, Taubenschuss E, et al. : Association of the rs1346044 Polymorphism of the Werner Syndrome Gene RECQL2 with Increased Risk and Premature Onset of Breast Cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2015;16(12):29643–53. 10.3390/ijms161226192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 88. Ding S, Yu JC, Chen ST, et al. : Genetic variation in the premature aging gene WRN: a case-control study on breast cancer susceptibility. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16(2):263–9. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Wang Z, Xu Y, Tang J, et al. : A polymorphism in Werner syndrome gene is associated with breast cancer susceptibility in Chinese women. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;118(1):169–75. 10.1007/s10549-009-0327-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Agrelo R, Cheng WH, Setien F, et al. : Epigenetic inactivation of the premature aging Werner syndrome gene in human cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(23):8822–7. 10.1073/pnas.0600645103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Bosch LJ, Luo Y, Lao VV, et al. : WRN Promoter CpG Island Hypermethylation Does Not Predict More Favorable Outcomes for Patients with Metastatic Colorectal Cancer Treated with Irinotecan-Based Therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22(18):4612–22. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-2703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 92. Frank B, Hoffmeister M, Klopp N, et al. : Colorectal cancer and polymorphisms in DNA repair genes WRN, RMI1 and BLM. Carcinogenesis. 2010;31(3):442–5. 10.1093/carcin/bgp293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Sun K, Gong A, Liang P: Predictive impact of genetic polymorphisms in DNA repair genes on susceptibility and therapeutic outcomes to colorectal cancer patients. Tumour Biol. 2015;36(3):1549–59. 10.1007/s13277-014-2721-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 94. Makley LN, McMenimen KA, DeVree BT, et al. : Pharmacological chaperone for α-crystallin partially restores transparency in cataract models. Science. 2015;350(6261):674–7. 10.1126/science.aac9145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 95. Harrigan JA, Wilson DM, 3rd, Prasad R, et al. : The Werner syndrome protein operates in base excision repair and cooperates with DNA polymerase beta. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34(2):745–54. 10.1093/nar/gkj475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]