Abstract

Introduction:

The ailments afflicting the elderly population is a well-defined specialty of medicine. It calls for an immaculately designed health-care plan to treat diseases in geriatrics. For chronic illnesses such as diabetes mellitus (DM), coronary heart disease, and hypertension (HTN), they require proper management throughout the rest of patient's life. An integrated treatment pathway helps in treatment decision-making and improving standards of health care for the patient.

Case Presentation:

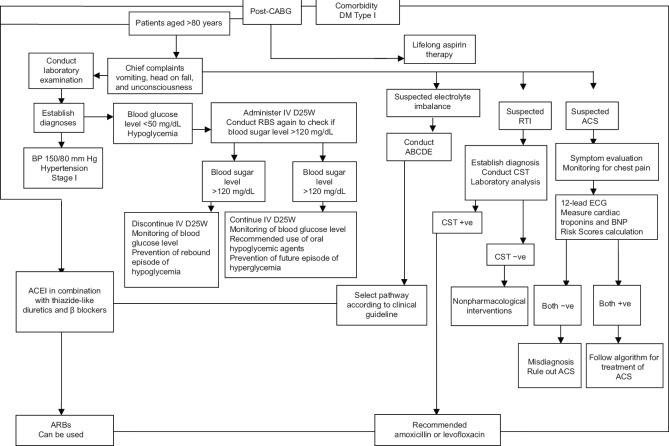

This case describes an exclusive clinical pharmacist-driven designing of an integrated treatment pathway for a post-coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) geriatric male patient with DM type I and HTN for the treatment of hypoglycemia and electrolyte imbalance.

Intervention:

The treatment begins addressing the chief complaints which were vomiting and unconsciousness. Biochemical screening is essential to establish a diagnosis of electrolyte imbalance along with blood glucose level after which the integrated pathway defines the treatment course.

Conclusion:

This individualized treatment pathway provides an outline of the course of treatment of acute hypoglycemia, electrolyte imbalance as well as some unconfirmed diagnosis, namely, acute coronary syndrome and respiratory tract infection for a post-CABG geriatric patient with HTN and type 1 DM. The eligibility criterion for patients to be treated according to treatment pathway is to fall in the defined category.

KEYWORDS: Comorbidity, diabetes mellitus, electrolyte imbalance, hypertension, hypoglycemia, medical algorithm, treatment pathway, respiratory tract infection, postcoronary artery bypass grafting

INTRODUCTION

There has been a steady increase in the geriatric population across the globe. The World Health Organization states that geriatric population include any member above the age of 60 years.[1] The ailments afflicting the elderly population is a well-defined specialty of medicine, i.e., geriatric medicine.[2] It calls for an immaculately designed health-care plan to treat diseases in geriatrics. Diseases common in geriatrics include disorders of cardiovascular, respiratory, neuromuscular, endocrine, renal, and gastrointestinal systems.[3] The onset of these diseases can begin in the late 40s and may exacerbate over time. Reduced and impaired physiological function in the elderly gives rise to a number of comorbid conditions. Most often, incomplete reporting of how patient feels, signs and symptoms are not documented, and a lack of laboratory tests to confirm the diagnosis affects the choice of drug for suitable treatment. Usually, medicines that are prescribed based on physician's “suspicion” leads to polypharmacy.[4] The implications of polypharmacy are decreased patient compliance owing to an inability to use medical devices, difficulty in administering drug regimen, and/or suffering from an adverse drug reaction.[5] This predicament can be curtailed to a large extent only by detailed and appropriate diagnosis, following a standard treatment process and prescribing the most suitable drug.

Establishing accurate diagnoses by clinical and laboratory examination not only helps the clinicians in rational prescribing but also aids the pharmacists in optimizing the medication therapy. Chronic illnesses such as diabetes mellitus (DM), coronary heart disease, and hypertension (HTN) require proper management throughout the rest of patient's life.[6] Pharmacists can suggest necessary dietary changes and counsel regarding safe use of medicines. A pharmacist-led pharmaceutical care can prevent significant adverse effects that a patient may face when undergoing pharmacotherapy.[7,8,9]

An integrated treatment pathway or an integrated care pathway is a set of instructions and mechanism developed with evidence-based information for the treatment of a disease and/or a condition for a specific population.[10] It depends on the outcome and disease progression. This pathway serves as a guide for careful selection of treatment goals, medications, monitoring parameters of the patient's health, and objectives. It can, therefore, help in treatment decision-making and improving standards of health care for the patient.[11]

CASE PRESENTATION

An elderly geriatric male patient was brought to the emergency room (ER) after experiencing an episode of hypoglycemia. He had cough and appeared restless. He was post CABG with history of ischemic heart disease (IHD), DM type I and was recently diagnosed with HTN.[7]

Subjective information

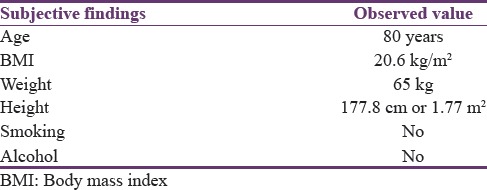

The subjective findings revealed that the patient was 80 years old with a normal body mass index (BMI), i.e., 20.6 kg/m2, weight 65 kg, and height 177.8 cm. The patient was accompanied by a caregiver. Inactive complaints include CABG which the patient underwent 10 years ago. A summary of subjective information is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Subjective findings from the patient's medical record

Objective information

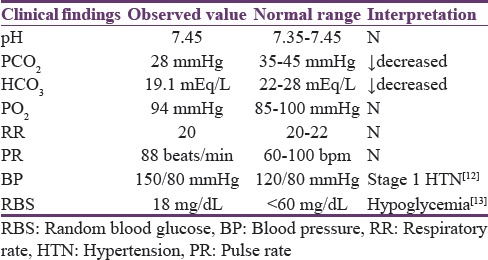

Laboratory investigations included computed tomography (CT) scan, arterial blood gas (ABG), vital signs (VS), chest X-ray (CXR), and electrocardiogram (ECG). Clinical findings revealed normal brain function, decreased partial pressure of carbon dioxide (PCO2) and oxygen (PO2), stage I HTN with systolic blood pressure (SBP) 150 mmHg and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) 80 mmHg, blood glucose level of 18 mg/dL or 1 mmol/L, and a normal ECG. Furthermore, chest examination and CXR revealed a positive bilateral baseline crepitus. The patient had no history of alcohol consumption and smoking. The summary of patient's objective information is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Objective findings from the patient's medical record

Diagnosis

Based on the patient's objective information, the clinician's note mentioned respiratory tract infection (RTI), electrolyte imbalance, acute coronary syndrome (ACS), and suspected angina attack with no proper laboratory investigations. Pharmacological therapy was initiated based on the clinician's notes.

Treatment

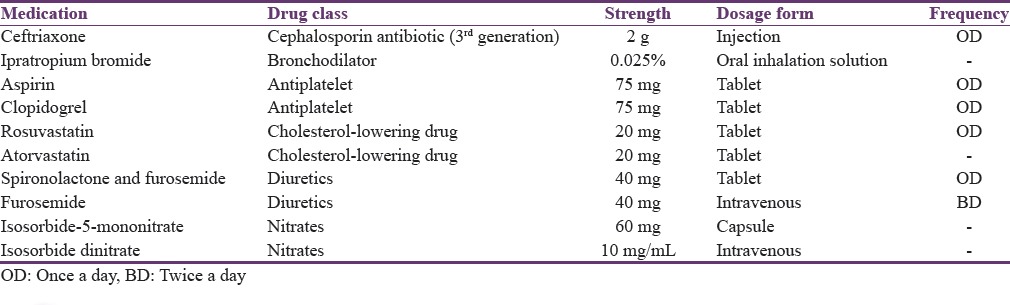

The patient's hypoglycemic episode was treated by administering 1000 ml of 25% dextrose (D25) infusion along with intravenous (IV) insulin 70/30 and metformin 500 mg PO BID to raise and maintain blood glucose level. For the management of HTN, the patient was prescribed angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEI) with loop diuretic. For the treatment of suspected RTI, the patient was prescribed an antibiotic therapy with 3rd generation cephalosporin. Two nitrates were prescribed for preventing angina attack along with two antiplatelet agents and two statins. A summary of medications are tabulated in Table 3.

Table 3.

Medication information of the patient

Assessment of therapy

This is a case of a geriatric patient aged 80 years who presented to the ER with acute hypoglycemic episode and a suspicion of electrolyte imbalance. This post-CABG geriatric patient had HTN and type 1 DM confirmed with an established diagnosis.[7] During assessment of therapy, it was observed that, apart from hypoglycemia and HTN, the chest examination revealed positive bilateral baseline crepitus indicative of the underlying disease that needs to be further evaluated; however, the physician jotted RTI as a diagnosis without laboratory analysis and prescribed ceftriaxone antibiotic treatment for RTI and a bronchodilator. Electrolyte imbalance was not confirmed through laboratory and treatment was initiated with 1000 ml D25 infusion. ACS and suspected angina attack were also mentioned in the diagnosis that lacked proper laboratory investigations. Furthermore, important laboratory and biochemical analysis such as renal function was not assessed. It was important since the patient was prescribed metformin (oral hypoglycemic drug).

The assessment of patient's medical record further highlighted major medication-related problems. The use of wrong drug, that is, loop diuretic for treating his HTN. The patient was also prescribed a bronchodilator, ipratropium bromide which was not needed. The patient was also given IV 3rd generation cephalosporin on a suspected RTI diagnosis and without a proper diagnosis and culture sensitivity test (CST). This has potential for antibiotic misuse and may cause resistance. Keeping in view the age of the patient, this may possess detrimental consequences for his health. There was also a case of misdiagnosis as the physician suspected stable angina and prescribed two nitrates for preventing an angina episode. In addition, there was a case of concomitant prescribing of two statins and an unnecessary antiplatelet drug combination.

RECOMMENDATION

Before starting the treatment for the patient, appropriate diagnosis supported with accurate laboratory investigation is required. The second step usually involves prioritizing patient complaints. In this case, the patient had suffered from a hypoglycemic episode, hence priority is to treat this acute condition. Secondly, the clinician mentioned a number of suspected diagnoses such as electrolyte imbalance, RTI, ACS, and angina in patient medical record without appropriate laboratory results. It is important to supplement the diagnoses with accurate laboratory results before treatment.

INTERVENTION

The post-CABG geriatric patient in our case had type I DM and HTN. The treatment began addressing his chief complaints which were vomiting and unconsciousness. Biochemical screening is essential to establish a diagnosis of electrolyte imbalance along with blood glucose level. For the treatment of hypoglycemia, administration of IV D25 is required after which random blood sugar (RBS) test can confirm whether the patient has recovered from the episode. If the blood glucose level has recovered above 120 mg/dL, the IV line may be discontinued and follow-up goals be defined; however if not, the IV line may be continued and the need for prescribing oral hypoglycemic agents to prevent hyperglycemia be evaluated. If there is a need to prescribe oral hypoglycemic agents such as metformin, assessment of renal function is required.[13]

For the treatment of electrolyte imbalance, the National Institute of Care and Health Excellence (NICE) recommended a set of algorithms to address IV fluid therapy in adults. Using the assessment of airway, breathing, circulation, disability, and exposure approach can help analyze if there is a need of fluids and electrolyte replenishment.[14]

According to the patient's VS, he had SBP of 150 and DBP of 80 that rendered him Stage I hypertensive as per the 7th Joint National Committee (JNC) guidelines criteria (identified as standard). For such patients with comorbid DM and post-CABG, the JNC 7 guidelines recommend using ACEI in combination with a diuretic or β-blocker as 1st line therapy for treatment. Since the patient had cough due to suspected RTI, using ACEI is not recommended in this situation. In addition, the patient had DM, and hence β-blockers are contraindicated. Moreover, in the state of electrolyte imbalance, using loop diuretics is not appropriate. Angiotensin receptor blockers can be used in place of ACEIs with thiazide diuretics.[12]

Regarding the suspected RTI, proper clinical assessment including laboratory investigation of elevated white blood cell count counts, sputum CST, and associated signs and symptoms is needed to decide prescribing an antibiotic. Pharmacotherapy for treatment of RTI with antibiotics such as amoxicillin or levofloxacin (if allergic to penicillin) is recommended only if the CST is positive. If the CST is negative, the patient can be initiated nonpharmacological therapy.[15,16] However considering patient's age, it is debatable whether awaiting laboratory results before starting an empirical therapy with a broad-spectrum antibiotic may be beneficial.

Regarding the suspicion of ACS, proper clinical history is needed to understand the condition supplemented with a 12-lead ECG and estimation of cardiac troponins and brain natriuretic peptide (BNP). ACS is diagnosed if there are abnormal changes in the ECG and/or abnormally elevated troponin levels. Following the diagnosis, treatment pathway for treating ACS needs to be followed.[17] The whole treatment is presented as an integrated treatment pathway in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Integrated treatment pathway

CONCLUSION

The scope of this case report is to propose an integrated treatment pathway to treat such patients. This provides an outline of the course of treatment of hypoglycemic emergency, electrolyte imbalance; ACS and RTI for a post-CABG geriatric patient with HTN and type 1 DM. The eligibility criterion for patients to be treated according to the proposed treatment pathway is to fall in the defined category. By following the pathway, it is believed that patients can be effectively managed, symptomatically treated, and advised for further evaluation without the risks of medication errors and drug-related problems.

Supporting information

All information concerning the case was reproduced with permission from the authors. The treatment pathway used references which were identified as standards of treatment in the clinical setting where the patient was previously treated. This paper is second installment of a case study research project undertaken as a part of evidence-based improvement initiative for partial fulfillment of Doctor of Pharmacy (Pharm. D) degree at the Faculty of Pharmacy, Ziauddin University by Miss. Amna Shah (Ref# 5-2/2011/062) during 2014–2015.[18,19] The treatment pathway represents agreement of the practicing physicians and pharmacists in the clinical setting currently and may not be exhaustive. The practical application of this work is currently underway in ER of a private sector tertiary care hospital of Karachi, Pakistan (Ref # CH-19-2-17).

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

We extend our gratitude to Dr. Muntazir A. Zaidi, CEO of Clifton Hospital Karachi and the medical staff of the hospital for their moral support in the course of this work.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization (WHO) Ageing. [Last cited on 2017 Apr 09]. Available from: http://www.who.int/topics/ageing/en/

- 2.Cassel CK. Geriatric Medicine: An Evidence Based Approach. 4th ed. USA: Springer Science and Business Media; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 3.7 Health Challenges of Aging. WebMD. 2017. [Last cited on 2017 April 10]. Available from: http://www.webmd.com/healthy-aging/features/aging-health-challenges#1 .

- 4.Dagli RJ, Sharma A. Polypharmacy: A global risk factor for elderly people. J Int Oral Health. 2014;6:i–ii. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maher RL, Hanlon J, Hajjar ER. Clinical consequences of polypharmacy in elderly. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2014;13:57–65. doi: 10.1517/14740338.2013.827660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barlow J, Wright C, Sheasby J, Turner A, Hainsworth J. Self-management approaches for people with chronic conditions: A review. Patient Educ Couns. 2002;48:177–87. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(02)00032-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shah A, Naqvi AA, Ahmad R. The need for providing pharmaceutical care in geriatrics: A case study of diagnostic errors leading to medication-related problems in a patient treatment plan. Arch Pharma Pract. 2016;7:87–94. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adnan S, Tanwir S, Abbas A, Beg AE, Sabah A, Safdar H, et al. Perception of physicians regarding patient counselling by pharmacist: A blend of quantitative and qualitative insight. Int J Pharm Ther. 2014;5:117–21. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abbas A, Khan N. Clinical trials involving pharmacists in Pakistan's healthcare system: A leap from paper to practice. Pharmacy. 2014;2:244–7. [Google Scholar]

- 10.How to Produce and Evaluate an Integrated Care Pathway (ICP): Information for Staff. NHS Choices. NHS, United Kingdom. 2010. [Last cited on 2017 Apr 10]. Available from: http://www.gosh.nhs.uk/health-professionals/integrated-care-pathways .

- 11.Johnson KA, Svirbely JR, Sriram MG, Smith JW, Kantor G, Rodriguez JR. Automated medical algorithms: Issues for medical errors. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2002;9(6 Suppl 1):s56–7. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL, Jr, et al. The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure: The JNC 7 Report. JAMA. 2003;289:2560–72. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.19.2560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McNaughton CD, Self WH, Slovis C. Diabetes in the emergency department: Acute care of diabetes patients. Clin Diabetes. 2011;29:51–9. doi: 10.1007/s40138-012-0007-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence NICE. Algorithms for IV Fluid Therapy in Adults. [Last cited on 2017 Apr 11]. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg174/resources/intravenous-fluid-therapy-in-adults-in-hospital-algorithm-poster-set-191627821 .

- 15.Wong DM, Blumberg DA, Lowe LG. Guidelines for the use of antibiotics in acute upper respiratory tract infections. Am Fam Physician. 2006;74:956–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Self-limiting Respiratory Tract Infections – Antibiotic Prescribing Overview. 2016. [Last cited on 2017 Apr 11]. Available from: https://www.pathway.snice.org.uk/pathways/self-limiting-respiratory-tract-infections---antibiotic-prescribing .

- 17.Amsterdam EA, Wenger NK, Brindis RG, Casey DE, Jr, Ganiats TG, Holmes DR, Jr, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC Guideline for the management of patients with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes. American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:24. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abbas A. Evidence based improvements in clinical pharmacy clerkship program in undergraduate pharmacy education: The evidence based improvement (EBI) initiative. Pharmacy. 2014;2:270–5. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Naqvi AA. Evolution of clinical pharmacy teaching practices in Pakistan. Arch Pharma Pract. 2016;7:26–7. [Google Scholar]