Abstract

Objectives:

The primary objective of this retrospective study was to determine the prevalence of leprosy in families, and the secondary objective was to study the clinicoepidemiological features of leprosy in families.

Results:

There were a total of 901 cases of leprosy who attended our leprosy centre during this 18 year period. There were 49 cases of leprosy in this group whose family members also had documented leprosy (n = 49). A total of 61 family members of the index cases were affected by leprosy, thus making a total of 110 cases. There were 30 males (61.22%) and 19 females (38.78%) in the index cases. The age group of 21–40 years comprised the maximum number of cases in the index group, accounting for 24.49%. Borderline tuberculoid (BT) was the commonest type of leprosy in both the index cases and family members accounting for 48.98% and 55.74%, respectively. Conjugal leprosy was present in 16 couples. In 68.75% of leprosy in couples, one member was of the lepromatous type. Children (10–15 years age group) accounted for 10 cases in this study (9.09%). In children, 90% of the cases had one member with lepromatous leprosy.

Conclusions:

The prevalence of leprosy in families in this study was 5.44%. BT was the most common type of leprosy in both the index cases and family members. The prevalence of conjugal leprosy was 1.78%, with majority of the partners having the lepromatous type. Of the affected children, 90% had family members with lepromatous type of leprosy.

Keywords: Conjugal leprosy, family, leprosy

Introduction

Leprosy occurring in families is a well-established fact because the spread of leprosy is predominantly through nasal droplets and close contact among family members living in the same environment, which is conducive for the spread of leprosy, especially if one member is borderline lepromatous (BL) or lepromatous leprosy type (LL), smear positive “open case”[1] Leprosy occurring in families is a grave epidemiological and social problem, because affected children in these families can be a source of infection to other children in their schools. There is a paucity of studies regarding leprosy in families worldwide, and hence, we conducted this study. The primary objective of this study was to determine the prevalence of leprosy in families in this part of the country, and the secondary objective was to study the clinical and epidemiological features of leprosy in families.

Materials and Methods

This was an 18-year (1997–2014) retrospective, descriptive study performed in an urban leprosy centre of a tertiary care hospital. The study population included all new cases of leprosy who attended our centre during the study period with documented leprosy in their families. The data were collected from the preformatted standard leprosy cards of the aforementioned centre. An “index case” was defined as the leprosy patient who first consulted our centre and was registered at our centre for their disease.[2] A “family member” was defined as a blood relative or the marital partner of the index case and residing under the same roof.[2] Age, sex, and duration of illness was the main demographic data collected. A thorough family history was obtained, and the data regarding similar illness in the family were collected. The nature of the residence, type of housing, and socioeconomic status were also noted down. The clinical details of the index cases and affected family members were thoroughly recorded. Histopathology slides were reviewed. The types of leprosy were classified by combining the Ridley–Jopling and the Indian system of classification.[3] The collected data was analyzed in terms of descriptive statistics.

Permission to conduct this study was sought from the Institutional ethical Review Board; however, this being a retrospective, case records based study with no direct patient involvement, permission was not required.

Results

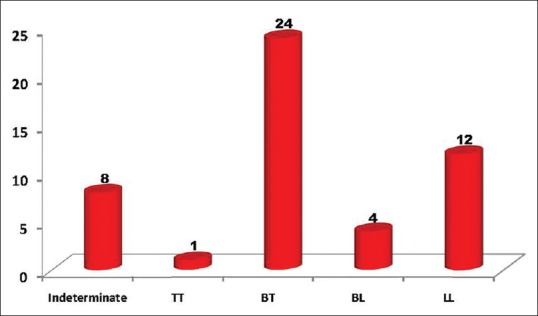

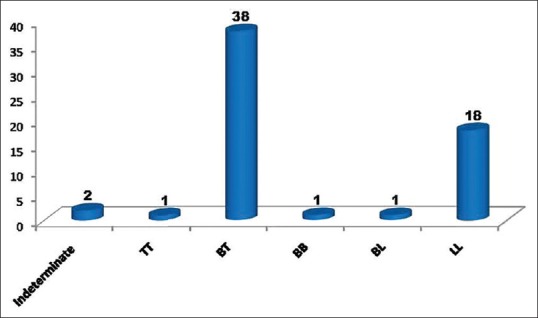

There were a total of 901 new cases of leprosy who attended our urban leprosy centre during the 18-year study period. There were 49 cases of leprosy in this group whose family members also had documented leprosy (n = 49). This accounted for a prevalence of 5.44%. A total of 61 family members (n = 61) of these index cases were affected by leprosy. Thus, the index and the family members accounted for a total of 110 cases. In addition to the index case, in 2 families 3 members were affected, in 8 families 2 members were affected, and in 39 families only one member was affected. Thirty-five cases (71.43%) of the index group belonged to the lower socioeconomic status (income of <500 INR per month). The salient demographic and clinical features of the index cases and the family members are presented in Table 1. Figures 1 and 2 show the type of leprosy in the index cases and the family members, respectively. BT was the most common type of leprosy in both the index cases and the family members, accounting for 48.98% and 55.74%, respectively. Conjugal leprosy was present in 16 couples, thus accounting for a prevalence of 1.78%. In 68.75% (11/16) of leprosy in couples, one member was of the BL/LL type. Children (10–15 years age group) accounted for 10 cases in this study (10/110, 9.09%). In children, 90% (9/10) of the cases had one member with LL.

Table 1.

The salient demographic and clinical features of leprosy in the index case and family members

Figure 1.

Types of leprosy in the index case (n = 49)

Figure 2.

Types of leprosy in the family members (n = 61)

Discussion

This retrospective study detected a prevalence of 5.44% of leprosy in families. This prevalence rate is much less than similar studies. A study conducted in China in multiple provinces by Shen et al. showed prevalence rates ranging from 14.1% to 22%.[4] A similar study done by Deps et al. in Brazil showed a prevalence rate of 18.2%.[5] Brazil is a country with high prevalence of leprosy. The low prevalence of leprosy in families in this study could be due to the fact that India is now in the elimination phase of leprosy, where the prevalence is less than 1 in 10000. The number of family members afflicted by leprosy was more (61 cases) than the number of index cases (49), because, in 10 families, more than 1 member was affected. The majority of the index cases (71.43%) were from the lower socioeconomic class with 2–3 room houses. In 90% of these families, multiple family members were sleeping in the same room. Overcrowding and close contact among family members is an important cause for leprosy occurring in families, as leprosy is predominantly transmitted by nasal droplets. Studies have shown that poor quality of indoor air as in small dwellings and overcrowding facilitate the transmission of air-borne infections.[6] There was not much difference in the sex ratio, affected age group, and mean duration of illness in both the index and family members, indicating no significant epidemiological differences between the index and family members afflicted by leprosy [Table 1]. In both the index cases and the family members, males were predominant accounting for 61.22% and 52.46%, respectively. Most studies have shown that, in all age groups, males are more susceptible to leprosy than females. This could be due to genetic factors and because of the fact that, males owing to their outdoor activity, pertaining to occupation, frequently come into contact with more people than females. BT was the most common type of leprosy in both the index cases (48.98%) and the family members (55.74%). This can be explained by the fact that the most common type of leprosy in India is the BT type. However, 35 cases (31.81%) belonging to either the index cases or family members were of the BL/LL type. The presence of LL in one family member increases the chances of other members acquiring leprosy [Figure 3].[2,6]

Figure 3.

Leprosy in a family: (a) Infiltrated papules and plaques with positive acid fast bacilli of lepromatous leprosy in the father, (b) annular anesthetic plaques of borderline tuberculoid in the mother, (c) anesthetic macule of borderline tuberculoid in their son

There were 16 couples with leprosy (conjugal leprosy) in this study with a prevalence of 1.78%. Studies have shown that “bedroom contact” has greater risk for transmission of leprosy than “household” contact.[7] In 68.75% of the married couples, one partner was BL/LL type [Figure 3]. In a recent study conducted in South India, among newly diagnosed 257 cases of leprosy, there was a known index case in 71 cases, which included household as well as social contacts.[8]

In the present study children (10–15 years) accounted for 10 cases (11%). In children also, males were predominant (70%). This is similar to the study by Prasad et al. and Kant et al.[9,10] BT/TT were the most common type of leprosy (70%) seen in children, whereas, BL/LL were the most common type (90%) seen in their family members, again indicating that leprosy in children was acquired from their family members who were smear positive. Parents were the main source of infection in children. Similar findings were present in the study of childhood leprosy by Jain et al., where family contact was present in 95% of cases, and 35% of the family members were multibacillary cases.[11] Childhood leprosy has ominous implications because children can spread the disease to other children in their schools. Moreover, childhood leprosy always indicates smouldering infection in the community.

Because of lack of similar studies in India, we could not compare our data with a national study. Future similar studies may ascertain the general trend in our country regarding leprosy in families.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study showed a prevalence of 5.44% of leprosy in families. Males were predominant in both the index cases and family members. BT was the most common type in both the groups. The prevalence of conjugal leprosy was 1.78% with the majority having BL/LL. Children constituted 9.09% in this study, with majority of the parents of these children having BL/LL.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Moet FJ, Meima A, Oskam L, Richardus JH. Risk factors for the development of clinical leprosy among contacts, and their relevance for targeted interventions. Lepr Rev. 2004;75:310–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.George R, Rao PS, Mathai R, Jacob M. Intrafamilial transmission of leprosy in Vellore Town, India. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 1993;61:550–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ridley DS, Jopling WH. A classification of leprosy according to immunity – A five group system. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 1966;34:255–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shen J, Wang Y, Zhou M, Li W. Analysis on value of household contact survey in case detection of leprosy at a low endemic situation in China. Indian J DermatolVenereolLeprol. 2009;75:152–6. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.48660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deps PD, Guides BV, Filho JB, Andreatta MK, Marcari RL, Rodriges LC. Characteristics of known leprosy contact in a high endemic area in Bazil. Lepr Rev. 2006;77:34–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jesudasan K, Bradley D, Smith PG, Christian M. Incidence rates of leprosy among household contacts of ‘primary cases’. Ind J Lepr. 1984;56:600–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burge HA. Indoor air and infectious disease. Occup Med. 1989;4:713–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anjum V, Vijayakumaran P. Presence of an index case in household contacts of newly registered leprosy cases: Experience from a referral leprosy center in South India. Lepr Rev. 2015;86:383–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prasad PVS. Childhood leprosy in a rural hospital. Ind J Pediatr. 1998;65:751–4. doi: 10.1007/BF02731059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kant L, Mukherji D. Childhood leprosy. IndPediatr. 1987;24:105–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jain S, Reddy RG, Osmani SN, Lockwood DNJ, Sunitha S. Childhood leprosy in an urban clinic, Hyderabad, India: Clinical presentation and the role of household contacts. Lepr Rev. 2002;73:248–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]