Abstract

Background

Genetic research in human health relies on the participation of individuals with or at-risk for different types of diseases, including health conditions that may be stigmatized, such as mental illnesses. This preliminary study examines the differences in attitudes toward participation in genetic research among individuals with a psychiatric disorder, individuals with a physical disorder, and individuals with no known illness.

Methods

Seventy-nine individuals with a history of diabetes or depression, or no known illness, underwent a simulated consent process for a hypothetical genetic research study. They were then surveyed about their willingness to participate in the hypothetical study and their attitudes about future and family participation in genetic research.

Results

Participants with and without a history of depression ranked participating in genetic and medical research as very important and indicated that they were likely to participate in the hypothetical genetics study. Expressed willingness to participate was generally stable and consistent with future willingness. Individuals less strongly endorsed willingness to ask family members to participate in genetic research.

Conclusion

Individuals with and without a history of mental illness viewed genetic and medical research favorably and expressed willingness to participate in real-time and in the future. Informed consent processes ideally include an exploration of influences upon volunteers’ enrollment decisions. Additional empirical study of influences upon genetic research participation is important to ensure that volunteers’ rights are respected and that conditions that greatly affect the health of the public are not neglected scientifically.

Keywords: Informed consent, Genetics, Depression, Attitudes, Research participation

Genetic research is leading to a greater understanding of many diseases and has accelerated the process of identifying novel interventions to prevent and treat diverse physical and mental disorders (Jordan and Tsai, 2010; Lau and Eley, 2010). Analysis of large-scale genomic data has helped to discern valuable biomarkers, providing insights into the genetic correlates and contributions to disease and, in some cases, predicted responsiveness to pharmacological agents (Bloss et al., 2010; Hirschhorn, 2009; Jordan and Tsai, 2010; McCarty et al., 2007). In the context of neuropsychiatric conditions, genetic research may yield new strategies for earlier and more accurate diagnoses for mental disorders, improved treatments, and more positive perceptions of these illnesses in society (Braff and Freedman, 2008; Erickson and Cho, 2011; Hoop et al., 2010; Spriggs et al., 2008; Wright and Kroese, 2010).

Advances in psychiatric genetics have lagged, however, in part because of scientific challenges that accompany the fact that mental illnesses are typically complex disorders influenced by many interdependent genetic and environmental factors (LaPorte et al., 2008). Psychiatric genetics research also has intrinsic challenges because of the many issues associated with human research involving ill and potentially vulnerable volunteers (Coors and Raymond, 2009; Ryan et al., 2015). While all genetic inquiry raises certain ethical, legal, and social issues, psychiatric genetic investigation presents additional concerns (Laegsgaard and Mors, 2008). For instance, mental illness involves capacities relevant to a person’s identity to a larger extent than somatic illness (Laegsgaard and Mors, 2008). Moreover, it is unclear how the “geneticization” of mental illness will affect the stigma and guilt often associated with these disorders (Hoop, 2008). Although some theories claim that evidence of a genetic component for mood disorders would shift responsibility away from the self and to one’s biology, opposing perspectives claim that a genetic model for mood disorders may increase the perceived gravity and unchangeable nature of these illnesses, thus labeling people prior to the emergence of illness symptoms and increasing their potential stigma (Erickson and Cho, 2011; Laegsgaard and Mors, 2008; Meiser et al., 2007; Spriggs et al., 2008; Wilde et al., 2010). Empirical studies suggest that when the role of genetics is explained to individuals with psychiatric disorders and their families in the context of the role of the environment (i.e. genetic counselling), outcomes are positive (Austin and Honer, 2008), internalized stigma can decrease (Costain et al., 2014a, 2014b; Hippman, 2016), and empowerment increases (Inglis et al., 2015).

The ability of patients, society, and the scientific community to reap the potential benefits of genetic research will depend on the ethical inclusion of volunteers with psychiatric disorders such as depression, which are stigmatized conditions with genetic underpinnings that are complex and incompletely understood. At this time, there is limited research regarding individuals’ willingness and attitudes toward participation in genetic research (Bui, 2014; Erickson and Cho, 2013; Lawrence and Appelbaum, 2011; Lemke et al., 2010). To this end, the authors conducted a project involving a simulated consent process for a hypothetical genetics research study. We sought to understand the attitudes of individuals who would likely be eligible for genetic research enrollment in order to learn the views regarding their willingness to participate in the proposed hypothetical genetic research study, to participate in genetics research in the future, and to ask family members to participate in research described in the simulated consent procedure. We compared whether views of people with a history of mental illness (i.e., in this case, depression) or a physical illness (i.e., in this case, diabetes) differ and whether these views differ from the views of people without a history of illness. We explored associations between expressed willingness, personal characteristics, and other attitudes related to genetics research.

METHODS

The Human Research Review Committee (IRB) of the University of New Mexico (UNM) provided prospective approval of this minimal risk study.

Study population

Adult participants were recruited through flyers posted in outpatient clinic settings at a university-based medical school for participation in the simulated consent process for a hypothetical genetics research project. Individuals who reported having depression or diabetes, or no known illness were invited to volunteer. All volunteers provided written informed consent.

Procedures

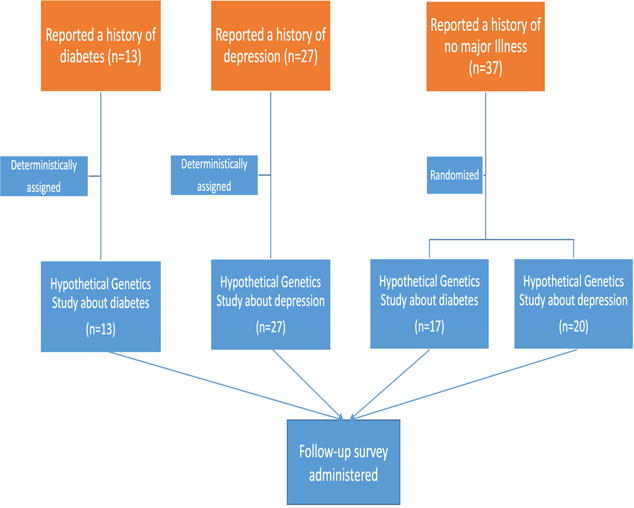

Our study procedure is depicted in Figure 1. Volunteers who self-reported a past diagnosis of depression were assigned to a depression simulated consent process; volunteers who reported no prior depression experience but had history of diabetes were assigned to a diabetes simulated consent process; and those with no illness experience were randomly assigned to either the depression simulated consent process or to the diabetes simulated consent process. Our project was not a deception study, i.e., potential participants were informed that they would not be enrolled in an actual genetic research protocol and that we were trying to learn about their views by engaging in a simulated consent process.

Figure 1.

Study design

Participants underwent a simulated informed consent process resembling those used in other genetic studies. A trained interviewer explained the hypothetical protocol and explained to participants that they would be asked to fill out questionnaires about their physical (or mental) health and family history of health and give a blood sample, which will be stored indefinitely and used by future studies. Risks and benefits, information about confidentiality information, policies regarding research-related injuries, and payments concerning the hypothetical study were also explained. Participants read their respective simulated consent form and discussed it with the interviewer. This interaction was intended to resemble the consent interaction at the beginning of an actual research study.

Measurement of Outcomes

Upon completion of the simulated consent process, a survey was administered to study participants to assess their attitudes regarding the consent process and their willingness to participate in genetics research resembling the hypothetical study. This survey included 31 scaled or open-ended questions concerning the simulated consent experience and attitudes toward research participation, 11 demographic questions, and 7 additional items related to the interaction with the interviewer during the simulated consent experience. The survey took approximately 30 minutes to complete. Study participants were compensated $20 for their time and effort.

Main outcome measures

Main outcome measures were attitudes regarding respondents’ willingness to (1) participate in the proposed hypothetical genetic research study, (2) participate in genetics research in the future, and (3) ask family members to participate in a trial like the one described in the simulated consent procedure. The first outcome was addressed in two questions. Participants were first asked if they would agree or not agree to participate in the described hypothetical genetic study (see Supplementary Material). Measures included respondents’ willingness to participate in the genetic research study (rated on a 9-point scale; yes or no). “Endorsements” of beliefs and “strong agreement” were defined by dichotomizing 9-point Likert items as 6 and greater, or 5 or less.

Secondary outcome measures included respondents’ willingness to participate in the genetic research study on a 9-point scale, under various influences (see supplemental material and Table 2b), including: a) if one had the illness being studied in the genetic study, b) if the study concerned a disease that a family member had, c) if the study in question would yield personal or family benefit, d) if the study in question would yield societal benefit (but no personal benefit), and e) if the study would yield scientific understanding (but no immediate personal or societal benefit).

Table 2b.

Influences on participation willingness overall and amongst the most highly willing to volunteer

| Overall | Participants “highly” willing | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| mean | sd | % | |

| If the research would help you or your family in some way | 8.40 | 1.13 | 92 |

| If the study concerned a disease that one of your family members had | 8.14 | 1.34 | 88 |

| If your family doctor recommended that you participate | 7.78 | 1.75 | 82 |

| If the research would help other people in some way, but not you or your family | 7.73 | 1.59 | 83 |

| If the research would increase scientific understanding, but not help people right away | 7.68 | 1.63 | 82 |

| If you were given more time to think about participating | 7.62 | 1.72 | 79 |

| If your family members encouraged you to participate | 7.51 | 2.08 | 74 |

Statistical analysis

We summarized overall trends of respondents’ perspectives on endorsements of research and their influences on participation willingness using descriptive statistics such as T-tests and chi-squared tests as appropriate. As a secondary aim, we assessed the association between participation willingness and covariates.

Covariates

Covariates in this study were respondent age, gender, race, self-reported history of illness, prior experience with a genetic test, endorsements of the importance of medical and genetic research, and family history of illness. Illness histories were not based on medical records but on self-report.

Tools

We took responses of multiple items as a vector outcome (i.e. willingness to participate now, future willingness to participate in the future, future willingness to participate in genetics study somewhat similar to the read protocol). Because items within each vector outcome were correlated for each individual, we used generalized estimating equations (GEE) with unstructured correlation structures to model associations between repeated outcome measures and covariates. Covariates used for the GEE model were indicators for the item type as well as the covariates listed above.

Missing data

Of the ninety-one individuals who were invited to participate, 12 individuals declined to participate, leaving 79 individuals in the study. Outcomes were missing for 2 out of 79 records. A complete case analysis was performed on 77 observations.

Software

We used R Studio v0.99.892 for all statistical analyses.

RESULTS

Study population characteristics

Our study had 77 adult volunteers. A majority of respondents were women (54%). Mean age was 42.5 years +/− 13.2 years. A majority of respondents were not married (i.e. either single, divorced or widowed, 56%). Ninety-two percent of study participants had at least a high school or GED diploma, and 57% had at least some college or higher graduate degrees. A summary of the study participant characteristics, stratified by past diagnosis (from self-report), is reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of study participants by illness group

| Depression N = 27 |

Diabetes N = 13 |

Healthy N = 37 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Women | 59% (16) | 69% ( 9) | 49% (18) |

| Men | 41% (11) | 31% ( 4) | 51% (19) |

| Median age | 37 45 51 | 38 41 59 | 30 38 48 |

| Education | |||

| Less than HS | 4% ( 1) | 8% ( 1) | 11% ( 4) |

| HS or GED | 30% ( 8) | 15% ( 2) | 41% (15) |

| Some college or 2-year degree | 41% (11) | 46% ( 6) | 35% (13) |

| College | 4% ( 1) | 23% ( 3) | 8% ( 3) |

| Graduate degree | 22% ( 6) | 8% ( 1) | 5% ( 2) |

| Marital Status | |||

| Single | 44% (12) | 8% ( 1) | 35% (13) |

| Divorced or widowed | 22% ( 6) | 23% ( 3) | 22% ( 8) |

| Married/Partner | 33% ( 9) | 69% ( 9) | 43& (16) |

| Race/Ethnicity* | |||

| Hispanic | 24% ( 6) | 54% ( 7) | 38% (12) |

| Native American | 4% ( 1) | 38% ( 5) | 31% (10) |

| White | 72% (18) | 8% ( 1) | 31% (10) |

| Protocol Assignment | |||

| Hypothetical Depression Study | 93% (27) | 0% ( 0) | 54% (20) |

| Hypothetical Diabetes Study | 0% ( 0) | 100% (13) | 46% (17) |

| Family history of illness | |||

| Yes | 93% (25) | 85% (11) | 84% (31) |

| None or unknown | 7% ( 2) | 15% ( 2) | 13% ( 6) |

| Prior exposure to genetic study | |||

| Yes | 22% ( 6) | 15% ( 2) | 19% ( 7) |

| No | 78% (23) | 85% (13) | 81% (29) |

a b c represent the lower quartile a, the median b, and the upper quartile c for continuous variables. Numbers after percents are frequencies.

6 missing values.

Previous research experience and family history

Most respondents, 87% (n=67), reported a family history of either physical or mental illness. Approximately 42% of study participants reported a family history of both diabetes and depression.

Among all volunteers, only 13% (n=10) of respondents had ever been asked previously to have a genetic test for any reason. Moreover, only 13% of respondents had a family member who had a genetic test in the past. A small proportion of respondents (27%, n=21) had ever participated in any medical research study other than the current study.

Perceived importance of research and likelihood of participation

Overall trends

Respondents on average expressed positive views regarding the importance of genetic research and medical research (means = 8.15 to 8.38 on a 9-point scale, SDs = 1.32). Table 2 reports respondents’ average endorsements of the importance of research specific to diagnosis group. Of all respondents in the study, an overwhelming majority, 94% (n=74), endorsed the importance of genetic research and a similarly high proportion (95%, n=75) endorsed the importance of medical research that does not involve genetics.

Table 2a.

Outcomes: participation willingness by self-reported history of illness

| Depression (N=29) |

Diabetes (N=13) |

Healthy /(N=37) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mean | sd | mean | sd | mean | sd | p-value | |

| Likelihood of participation in the genetic study* | |||||||

| If asked to participate now | 7.77 | 1.34 | 7.46 | 1.56 | 6.95 | 2.13 | 0.20 |

| If asked to participate in the future | 7.85 | 1.43 | 7.92 | 1.19 | 7.35 | 1.93 | 0.39 |

| Willingness to approach family members* | |||||||

| If asked to approach for the genetic study | 6.11 | 2.87 | 7.85 | 1.34 | 6.43 | 2.09 | 0.08 |

Respondents on average endorsed the view that people should participate in genetic and medical research (means = 7.24 to 7.68, SDs = 1.70). A greater majority, 86% (n=67), of participants agreed that people should participate in genetic research, and 79% (n=62), agreed that people should participate in medical research. Such trends were consistent across individuals with varied self-reported histories of health.

Influences of participation willingness

Overall trends

Participants rated their influences on their willingness to participate in the genetic study (see Table 2b). Out of the nine given circumstances, participants were most influenced to participate in the genetic study “if the research would help [them] or [their] family in some way” (mean = 8.48, SD = 1.05). Table 2b summarizes the rankings of these influences.

Willingness to participate, willingness to involve family members, and predictors of willingness outcomes

Participation Willingness – overall trends

When asked in simple terms if they would agree or disagree to participate in the described genetic research study, 94% (n=72) of respondents indicated that they would participate. When asked to rate their participation likelihood on a 9-point scale, they expressed on average a moderately high likelihood of participation (mean = 7.32, SD=1.80). Of the people who initially agreed to participate in simple terms, 15% of these study participants rated their likelihood as only “somewhat likely” or below. On the other hand, all individuals who said they would not agree to participate in the initial question held consistent views and subsequently responded that they were either not at all likely to somewhat likely to participate in such a study. A high proportion of study participants expressed willingness to participate in a genetics study in the future (85%).

Exploratory findings related to expressed willingness

Perceived importance of research was associated with higher levels of participation likelihood related to genetic research (β from GEE = 0.57, 95% CI = [0.30, 0.83], p-value = 3*10^−5). For example, a 2-point increase in respondents’ average perceived importance of research was associated with a 1-point increase in participation likelihood. Moreover, a strong endorsement of medical and genetic research was associated with an increased likelihood of participation willingness (β from GEE = 0.44, 95% CI = [0.14, 0.74], p-value = 0.004).

Willingness to involve family members in genetic research – overall trends

Irrespective of family history of illness, respondents indicated that they would be moderately willing (mean = 6.6, SD = 2.4) to ask family members to participate in the hypothetical genetic study described in the simulated consent process, and 70% (n=54), reported that they would be likely or very likely to ask family members to participate.

A strong endorsement of the importance of medical and genetic research was associated with a greater likelihood to ask family members to participate in genetic research (β from linear model = 0.49, 95% CI = [0.10, 0.88], p-value = 0.02). Similarly, a perceived importance of medical and genetic research was associated with a higher likelihood of asking family members to participate in genetic research (β from linear model = 0.81, 95% CI = [0.30, 1.32], p-value = 0.003).

Self-reported family history of illness was found to be associated with a positive willingness to participate in such a genetic study. Individuals with family history of illness endorsed participation likelihood compared to individuals without or unsure of family history of illness. Of respondents who reported a family history of illness, 97% (n=67) of individuals responded with a positive willingness to participate in a genetic research study, compared to 70% of individuals who reported no family history of diabetes or depression (n=10) (p-value from pearson chi-squared test of association = 0.013).

DISCUSSION

This is the first published study, to our knowledge, to examine genetic research participation willingness in the context of a carefully constructed simulated informed consent process, comparing individuals with a mental illness (depression), physical illness (diabetes), or no such history of illness, and to assess influences on the expressions of willingness or unwillingness by these potential volunteers. For our study, we engaged with individuals in the locale of an academic medical center using recruitment techniques routinely used in health research. These individuals were certainly, on some level, receptive to research participation, as evidenced by their willingness to engage in our project and, not unexpectedly, we found that these individuals view genetic and medical research as very important. Most but not all of those in our study indicated that they would likely participate in the genetic research project described in the simulated consent process, now and even more so in the future. The overall pattern of willingness to participate was no different by history of illness (i.e., mental illness, physical illness, or neither) and appeared to be greatly shaped by individuals’ hopes that their participation might help to serve others, science or medicine, or their own health. Self-reported family history of depression or diabetes appeared to positively influence expressed willingness to participate in the proposed genetic research project. Interestingly, among the small minority who consistently expressed unwillingness to participate in the genetic research project, there was some openness to future participation. Most individuals in our project indicated that they would be willing to involve family members in a genetic research study, but this this was endorsed less strongly than personal willingness.

Whether individuals with mental illness should have special and additional protections in the context of human research has been debated for many years without resolution. Our findings suggest that there is no clear case that individuals with depression who are considering participation in genetic research require an “exception” to usual approaches or rules in human research. In our study, individuals with self-reported depression expressed views that were similar overall to those of individuals with a chronic physical illness, namely diabetes, and to individuals with no past experience of depression or diabetes. Individuals with depression affirmed the importance of self-benefit and altruism in genetic research, consistent with our and others’ prior findings (Lemke et al., 2012; Roberts et al., 2005). Recognition of the strengths of people with mental illness is important so that they are not inappropriately excluded from opportunities to participate in research, which may diminish the rights and respect owed to those with mental illness and inadvertently perpetuate scientific neglect of neuropsychiatric disorders (Humphreys et al., 2015; Roberts and Kim, 2014).

In this study, individuals with mental illness expressed interest in participating in genetic research. It is well documented that there is a strong interest in genetic testing for the risk of mental illness in clinical settings (Laegsgaard and Mors, 2008; Laegsgaard et al., 2009; Meiser et al., 2008; Smith et al., 1996; Trippitelli et al., 1998). Much remains unknown about the causes and care of mental illness, thus there is much need to advance genetic inquiry for neuropsychiatric and other brain-based conditions (Cichon et al., 2009; Lake and Baumer, 2010; Lau and Eley, 2010; Merikangas, 2007). Finding ways to accelerate such research is important to the health of the public, given the prevalence and significant suffering and social and economic effects associated with these disorders (Fung et al., 2015; Kassenbaum et al., 2016; Mechanic et al., 1994).

This novel study has the limitations inherent in a preliminary study using a self-report survey method. Moreover, the survey was created de novo for this project and has yet to be fully tested for its psychometric strengths or weaknesses. Another limitation derives from the fact that stated interest in hypothetical genetic research may or may not be a robust predictor of actual research enrollment or genetic testing “uptake” (e.g., Lerman et al., 2002); therefore the high numbers of individuals expressing intention to participate in this study may not reflect the true proportion of individuals who would actually choose to enroll. Finally, these findings may or may not be generalizable to other mental health populations or generalizable beyond the single site recruitment population. For these reasons, the study should be repeated with a larger, more diverse sample.

Nevertheless, our findings indicate that individuals across the groups assessed are inclined to participate in genetic research, as has been found in prior empirical work with other populations (Hoeyer et al. 2004; Wang et al., 2001). Individuals in our study were, overall, willing to engage with their families around genetic research and endorsed relevant and logical influences on their intentions to participate in genetic research. Clarifying motivations and influences upon research enrollment decision-making may be of value in the informed consent process, especially in the context of novel genetic research, if only to affirm the strengths of individuals who generously volunteer to enroll in human studies. In particular, our findings underscore the importance of assessing the understanding of participants, making certain that they are aware that research results, as with all human investigations, may not bring personal benefit. Moreover, genetic research may result in increased biopsychosocial risks, such as social stigma and negative health implications for genetic family members, particularly if the research volunteer has other sources of vulnerability in the research context (Biesecker and Peay, 2003; Bortolotti and Widdows, 2011; Coors and Raymond, 2009; Nwulia et al., 2011). Efforts to ensure a robust informed consent process may serve to reassure investigators that they have engaged with their volunteers in a careful manner that supports authentic decision-making, ensures that decisions are grounded in accurate information, and diminishes the chance of exploiting volunteers who may be potentially vulnerable by virtue of their illness experience (DeLisi and Bertisch, 2006; Roberts et al., 2005).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors express their appreciation to Jessica Alcalay Erickson, Jennifer Niskala Apps, Teddy Warner, Ph.D., Kate Green Hammond, Ph.D., and Rene M. Paulson, Ph.D., for their assistance in the development of this project and the data analyses performed and to Megan Smithpeter, M.D., who served as the project assistant for this work. Additional appreciation is expressed to Ann Tennier, ELS, for her editorial assistance.

Role of Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health and National Human Genome Research Institute [grant number 5 R01 MH074080].

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributors

Dr. Laura Roberts designed the study and wrote the protocol. Dr. Jane Kim managed and undertook the statistical analyses. Dr. Laura Roberts wrote the first draft of the articles, and both authors contributed to and have approved the final article.

References

- Austin JC, Honer WG. Psychiatric genetic counselling for parents of individuals affected with psychotic disorders: a pilot study. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2008;2(2):80–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7893.2008.00062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biesecker BB, Peay HL. Ethical issues in psychiatric genetics research: points to consider. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2003;171(1):27–35. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1502-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloss CS, Schiabor KM, Schork NJ. Human behavioral informatics in genetic studies of neuropsychiatric disease: multivariate profile-based analysis. Brain Res Bull. 2010;83:177–188. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2010.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bondy B. Genetics in psychiatry: are the promises met? World J Biol Psychiatry. 2011;12(2):81–88. doi: 10.3109/15622975.2010.546428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bortolotti L, Widdows H. The right not to know: the case of psychiatric disorders. J Med Ethics. 2011;37(11):673–676. doi: 10.1136/jme.2010.041111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braff DL, Freedman R. Clinically responsible genetic testing in neuropsychiatric patients: A bridge too far and too soon. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165:952–955. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08050717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bui ET, Anderson NK, Kassem L, McMahon LJ. Do participants in genome sequencing studies of psychiatric disorders wish to be informed of their results? A survey study PLoS One. 2014;9(7):e101111. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0101111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cichon S, Craddock N, Daly M, et al. Genomewide association studies: history, rationale, and prospects for psychiatric disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166:540–556. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08091354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coors ME, Raymond KM. Substance use disorder genetic research: investigators and participants grapple with the ethical issues. Psychiatr Genet. 2009;19(2):83–90. doi: 10.1097/YPG.0b013e328320800e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costain G, Esplen MJ, Toner B, Hodgkinson KA, Bassett AS. Evaluating genetic counseling for family members of individuals with schizophrenia in the molecular age. Schizophr Bull. 2014a;40(1):88–99. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbs124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costain G, Esplen MJ, Toner B, et al. Evaluating genetic counseling for individuals with schizophrenia in the molecular age. Schizophr Bull. 2014b;40(1):78–87. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbs138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLisi LE, Bertisch H. A preliminary comparison of the hopes of researchers, clinicians, and families for the future ethical use of genetic findings on schizophrenia. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2006;141B(1):110–115. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson JA, Cho MK. Ethical considerations and risks in psychiatric genetics: preliminary findings of a study on psychiatric genetic researchers. Am J Bioethics Primary Res. 2011;2(4):52–60. [Google Scholar]

- Erickson JA, Cho MK. Interest, rationale, and potential clinical applications of genetic testing for mood disorders: a survey of stakeholders. J Affect Disord. 2013;145(2):240–245. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.05.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fung LK, Akil M, Widge A, Roberts LW, Etkin A. Attitudes toward neuroscience education in psychiatry: a national multi-stakeholder survey. Acad Psychiatry. 2015;39(2):139–46. doi: 10.1007/s40596-014-0183-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschhorn JN. Genomewide association studies—illuminating biologic pathways. NEJM. 2009;360(17):1699–1701. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0808934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hippman C, Ringrose A, Inglis A, et al. A pilot randomized clinical trial evaluating the impact of genetic counseling for serious mental illnesses. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77(2):e190–8. doi: 10.4088/JCP.14m09710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoeyer K, Olofsson B, Mjörndal T, Lynöe N. Informed consent and biobanks: a population-based study of attitudes towards tissue donation for genetic research. Scand J Public Health. 2004;32:224. doi: 10.1080/14034940310019506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoop JG. Ethical considerations in psychiatric genetics. Harvard Rev Psychiatry. 2008;16:322–338. doi: 10.1080/10673220802576859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoop JG, Lapid MI, Paulson RM, Roberts LW. Clinical and ethical considerations in pharmacogenetic testing: Views of physicians in 3 “early adopting” departments of psychiatry. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71:745–753. doi: 10.4088/JCP.08m04695whi. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys K, Blodgett JC, Roberts LW. The exclusion of people with psychiatric disorders from medical research. J Psychiatr Res. 2015;70L:28–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2015.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inglis A, Koehn D, McGillivray B, Stewart SE, Austin J. Evaluating a unique, specialist psychiatric genetic counseling clinic: uptake and impact. Clin Genet. 2015;87(3):218–24. doi: 10.1111/cge.12415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffee SR, Price TS. Gene-environment correlations: a review of the evidence and implications for prevention of mental illness. Molecular Psychiatry. 2007;12:432–442. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan BR, Tsai DFC. Whole-genome association studies for multigenic diseases: Ethical dilemmas arising from commercialization—the case of genetic testing for autism. J Med Ethics. 2010;36:440–444. doi: 10.1136/jme.2009.031385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassenbaum NJ, Arora M, Barber RM, et al. Global, regional, and national disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) for 315 disease and injuries and healthy life expectancy (HALE), 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. 2016;388(10053):1603–58. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31460-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klitzman R, Abbate KJ, Chung WK, et al. Psychiatrists’ views of the genetic bases of mental disorders and behavioral traits and their use of genetic tests. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2014;202(7):530–538. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laegsgaard MM, Mors O. Psychiatric genetic testing: Attitudes and intentions among future users and providers. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2008;147B:375–384. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laegsgaard MM, Kristensen AS, Mors O. Potential consumers’ attitudes toward psychiatric genetic research and testing and factors influencing their intentions to test. Genet Test. 2009;13:1–9. doi: 10.1089/gtmb.2008.0022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lake CR, Baumer J. Academic psychiatry’s responsibility for increasing the recognition of mood disorders and risk for suicide in primary care. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2010;23:157–166. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e328333e195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaPorte JL, Ren-Patterson RF, Murphy DL, Kelueff AV. Refining psychiatric genetics: from ‘mouse psychiatry’ to understanding complex human disorders. Behav Pharmacol. 2008;19(5–6):377–384. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e32830dc09b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau JYF, Eley TC. The genetics of mood disorders. Ann Rev Clin Psychol. 2010;6:313–337. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.121208.131308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence RE, Appelbaum PS. Genetic testing in psychiatry: a review of attitudes and beliefs. Psychiatry. 2011;74(4):315–331. doi: 10.1521/psyc.2011.74.4.315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemke AA, Halverson C, Ross LF. Biobank participation and returning research results: perspectives from a deliberate engagement in South Side Chicago. Am J Med Genet A. 2012;158A(5):1029–1037. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.34414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemke AA, Wolf WA, Hebert-Beirne J, Smith ME. Public and biobank participant attitudes toward genetic research participation and data sharing. Public Health Genomics. 2010;13:368–377. doi: 10.1159/000276767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerman C, Croyle RT, Tercyak KP, Hamann H. Genetic testing: psychological aspects and implications. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2002;70:784–797. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.3.784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarty CA, Nair A, Austin DM, Giampietro PM. Informed consent and subject motivation to participate in a large, population-based genomics study: The Marshfield Clinic Personalized Medicine Research Project. J Community Genet. 2007;10:2–9. doi: 10.1159/000096274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mechanic D, McAlpine D, Rosenfield S, Davis D. Effects of illness attribution and depression of the quality of life among persons with serious mental illness. Soc Sci Med. 1994;39:155–164. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90324-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meiser B, Mitchell PB, Kasparian NA, et al. Attitudes towards childbearing, causal attributions for bipolar disorder and psychological distress: a study of families with multiple cases of bipolar disorder. Psychol Med. 2007;37:1601–1611. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707000852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meiser B, Kasparian NA, Mitchell PB, et al. Attitudes to genetic testing in families with multiple cases of bipolar disorder. Genet Test. 2008;12:233–244. doi: 10.1089/gte.2007.0100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas K, Akiskal H, Angst H, et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of bipolar spectrum disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(5):543–552. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.5.543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell PB, Meiser B, Wilde A, et al. Predictive and diagnostic genetic testing in psychiatry. Clin Lab Med. 2010;30:829–846. doi: 10.1016/j.cll.2010.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nwulia EA, Hipolito MM, Aamir S, et al. Ethnic disparities in the perception of ethical risks from psychiatric genetic studies. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2011;156B(5):569–80. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.31198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts LW, Geppert CM, Warner TD, Green Hammond KA, Lamberton LP. Bioethics principles, informed consent, and ethical care for special populations: curricular needs expressed by men and women physicians-in-training. Psychosomatics. 2005;46(5):440–450. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.46.5.440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts LW, Warner TD, Geppert CM, Rogers M, Green Hammond KA. Employees’ perspectives on ethically important aspects of genetic research. Compr Psychiatry. 2005;46(1):27–33. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2004.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts LW, Kim JP. Giving voice to study volunteers: comparing views of mentally ill, physically ill, and healthy protocol participants on ethical aspects of clinical research. J Psychiatr Res. 2014;56:90–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2014.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan J, Virani A, Austin JC. Ethical issues associated with genetic counseling in the context of adolescent psychiatry. Appl Transl Genom. 2015;5:23–29. doi: 10.1016/j.atg.2015.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salm M, Abbate K, Appelbaum P, et al. Use of genetic tests among neurologists and psychiatrists: knowledge, attitudes, behaviors, and needs for training. J Genet Couns. 2014;23(2):156–163. doi: 10.1007/s10897-013-9624-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith LB, Sapers B, Reus VI, Freimer NB. Attitudes towards bipolar disorder and predictive genetic testing among patients and providers. J Med Genet. 1996;33:544–549. doi: 10.1136/jmg.33.7.544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spriggs M, Olsson CA, Hall W. How will information about the genetic risk of mental disorders impact on stigma? Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2008;42:214–220. doi: 10.1080/00048670701827226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trippitelli CL, Jamison KR, Folstein MF, Bartko JJ, DePaulo JR. Pilot study on patients’ and spouses’ attitudes toward potential genetic testing for bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155(7):899–904. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.7.899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang SS, Fridlinger F, Sheedy KM, Khoury MJ. Public attitudes regarding the donation and storage of blood specimens for genetic research. Community Genet. 2001;4:18–26. doi: 10.1159/000051152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilde A, Meiser B, Mitchel PB, Schofield PR. Public interest in predictive genetic testing, including direct-to-consumer testing, for susceptibility to major depression: preliminary findings. Eur J Hum Genet. 2010;18:47–51. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2009.138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright CF, Kroese M. Evaluation of genetic tests for susceptibility to common complex diseases: why, when and how? Hum Genet. 2010;127:125–134. doi: 10.1007/s00439-009-0767-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.