Abstract

Despite the theoretical importance of intragenerational mobility and its connection to intergenerational mobility, no study since the 1970s has documented trends in intragenerational occupational mobility. The present article fills this intellectual gap by presenting evidence of an increasing trend in intragenerational mobility in the United States from 1969 to 2011. We decompose the trend using a nested occupational classification scheme that distinguishes between disaggregated micro-classes and progressively more aggregated meso-classes, macro-classes, and manual and nonmanual sectors. Log-linear analysis reveals that mobility increased across the occupational structure at nearly all levels of aggregation, especially after the early 1990s. Controlling for structural changes in occupational distributions modifies, but does not substantially alter, these findings. Trends are qualitatively similar for men and women. We connect increasing mobility to other macro-economic trends dating back to the 1970s, including changing labor force composition, technologies, employment relations, and industrial structures. We reassert the sociological significance of intragenerational mobility and discuss how increasing variability in occupational transitions within careers may counteract or mask trends in intergenerational mobility, across occupations and across more broadly construed social classes.

Keywords: intragenerational mobility, occupation, micro-class, intergenerational mobility

Measures of intergenerational mobility—the degree to which offspring reproduce their parents’ social statuses—are indicators of fairness in systems of social stratification. Higher mobility is thought to be a central feature of meritocratic societies with permeable class boundaries and equality of opportunity, leading to the normative view of mobility as a relatively unambiguous good (Hauser et al. 1975; Hout 1988; Mitnik, Cumberworth, and Grusky 2016; Torche 2015a, 2015b; Xie and Killewald 2013). This view has inspired concerns among social scientists and policymakers that rising income and wealth inequality will lead to declining social mobility in the twenty-first-century United States. Much of this concern stems from the “Great Gatsby Curve,” which illustrates that levels of mobility tend to be lower in countries with higher levels of social inequality (Corak 2013; Krueger 2012). The recent upswing of inequality in the United States would seem to predict increasing intergenerational persistence of social status, and hence declining equality of opportunity. Yet, recent evidence suggests only weakly negative or null trends in intergenerational mobility across occupations (Beller and Hout 2006; Mitnik et al. 2016) and no distinct trend for income mobility (Aaronson and Mazumder 2008; Bloome 2015; Chetty et al. 2014; Lee and Solon 2009).

This apparent disconnect between trends in inequality and trends in intergenerational mobility might be understood by paying closer attention to trends in intragenerational mobility—mobility between labor market positions within individual careers. We build on evidence of increasing job instability across U.S. cohorts (Bernhardt et al. 2001; Hollister 2011, 2012), but we focus attention on occupations, which are important foci in the determination of unequal economic rewards (Mouw and Kalleberg 2010a). In particular, we propose that a rising intragenerational occupational mobility trend in the United States may have forestalled declines in intergenerational occupational mobility that might be expected based on recent increases in inequality.

Understanding how increasing intragenerational mobility may defuse nascent decreases in intergenerational mobility requires viewing the latter as a chained process made up of at least three interlocking links that connect individuals’ social origins to their social destinations: educational attainment, the school-to-work transition, and within-career mobility (Blau and Duncan 1967). There is evidence that mobility has declined in the first two links. Rising inequality seems to have strengthened the relationship between parents’ socioeconomic status and offspring’s scholastic achievement: children whose parents have more socioeconomic resources, especially income, are now more likely to have high scholastic achievement compared to 40 years ago (Reardon 2011). At the same time, education, especially a college degree, has become increasingly important for job placement and job rewards (Breen and Chung 2015; Lemieux 2006). Ignoring intragenerational mobility, these intensifying associations suggest declining intergenerational mobility. But if intragenerational mobility, the last link in the chain, is increasing, this may have counteracted declining mobility in the first two links. This reasoning guides our main research question: has intragenerational occupational mobility increased in recent decades?

More generally, we ask whether occupation, by itself, remains the best measure for comparing patterns of intergenerational mobility across places and times. Social stratification researchers typically operationalize intergenerational mobility in terms of occupational mobility, because occupation, assessed at mid-career, is assumed to be a relatively stable indicator of social status. Using snapshots of parents’ and offspring’s occupational attainments to evaluate levels of mobility requires accepting that individuals’ occupations are stable indicators of social status in both generations. Comparative research requires further assuming that occupation is equally stable across societies. If these assumptions do not hold, mobility studies relying on cross-sectional assessments of occupation may underestimate the degree of intergenerational persistence of status, in ways analogous to measurement error problems affecting income mobility studies (reviewed in Black and Devereux 2011; Solon 1999). Intergenerational mobility research should pay more attention to life-cycle variations in occupational mobility and whether occupational mobility across generations provides an adequate picture of equality of opportunity when careers are erratic.

Intragenerational mobility is also important in its own right. Mobility within internal labor markets and across institutional boundaries shapes human capital accumulation and wage trajectories (Farber 1999; Fuller 2008; Rosenfeld 1980, 1992). More mobility may lead to faster wage growth for some, but disrupt growth for others, leading to diverging life chances and rising economic inequality among workers over time (DiPrete and McManus 1996; Kambourov and Manovskii 2009; Mouw and Kalleberg 2010b). Levels of intragenerational mobility also indicate opportunity and coherence in careers. Mobility signals whether there are sufficient vacancies and connections between occupations to allow workers to progress in their careers or make desired career transitions (Breiger 1981, 1990; White 1970). Intragenerational mobility is a double-edged sword: too much mobility may indicate highly unstable and unpredictable labor markets that discourage workers and undermine productivity.

Despite its importance, few studies have examined trends in intragenerational occupational mobility since the 1970s. Instead, we have accumulated substantial knowledge about career mobility primarily through single or pooled cohort studies that investigate the life-course events, job progressions, promotions, and work disruptions that make up careers (Johnson and Mortimer 2002; Kronberg 2013; Sørensen 1974, 1975; Sørensen and Grusky 1996; Spilerman 1977; Wegener 1991) and identify individual, labor market, and industrial characteristics that shape diverse career trajectories (DiPrete 1993, 2002; Hachen 1992; Haveman and Cohen 1994). However, macro-economic changes—such as skill-biased technological change (Autor, Levy, and Murnane 2003), de-unionization (Western and Rosenfeld 2011), and precarious labor (Kalleberg 2009), as well as globalization, declining occupational gender segregation (Blau, Brummund, and Liu 2012), rising educational attainments, and increasing female labor force participation—have substantially restructured the U.S. labor market since the 1970s. These changes suggest shifting rates of intragenerational mobility that are made visible only by zooming out from individual cohorts and considering the full labor force.

In this article, we examine evidence of macro-economic changes to motivate expectations for trends in mobility from 1969 to 2011, a four-decade period characterized by rising economic inequality (Piketty and Saez 2006) and widening opportunity gaps among social classes (Grusky and Kricheli-Katz 2012; Putnam 2015). Because of increases in labor force participation among women and declining occupational sex segregation, we produce separate estimates for men and women. We adopt a multilevel, stratified view of the occupational structure that allows us to observe whether mobility is increasing at the highly aggregated class level or at the level of more detailed occupations (Jonsson et al. 2009). We group together closely related occupations into 75 relatively disaggregated micro-classes. We then define a level of 10 meso-classes by tying together related micro-classes, connect these meso-classes in five macro-classes, and allocate these macro-classes to two sectors following the manual/nonmanual divide.

Drawing on data from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics, our results show that intragenerational occupational mobility, even after structural changes in the labor market are controlled, has increased over time, especially after the 1990s, and especially among men. Mobility is inconsistently increasing for closely related micro-classes nested within meso-classes. Rather, we see more consistent increases in mobility involving larger steps across the occupational distribution, as workers more frequently shift between meso- and macro-classes, and between manual and nonmanual sectors. The rise in mobility is fairly general: incumbents in nonroutine professional, managerial, and craft micro-classes, and routine occupations in clerical, service, and lower nonmanual micro-classes, have all experienced rising mobility chances. These findings provide preliminary evidence that rising intragenerational occupational mobility may be masking the dampening effects of income and wealth inequality on intergenerational mobility. Social inequality may be undermining equality of opportunity, but occupational snapshots by themselves may no longer be sufficient for operationalizing lifetime socioeconomic standing and reading off changes in social mobility. We leverage these findings into a discussion of how a better understanding of intragenerational mobility can help guide future research on the intergenerational front.

A PERIOD APPROACH TO INTRAGENERATIONAL MOBILITY TRENDS

Despite a large and fast-growing literature on trends in economic inequality and intergenerational mobility, very little is known about trends in intragenerational occupational mobility since the 1970s. Most studies have taken a cohort or age approach that asks how patterns of mobility change across individuals’ early-, mid-, and late-career stages, rather than a period approach that shows how cross-sectional occupational mobility has evolved over time. The goal of the present study is to remedy this gap in the literature and provide a nuanced picture of how occupational mobility patterns have been changing over the past four decades, to suggest how these trends are related to broader changes in the U.S. economy and labor force, and to examine their implications for trends in intergenerational mobility.

The dearth of knowledge about trends in intragenerational occupational mobility is not for lack of scholarly attention to mobility processes. Analyses of longitudinal data for single cohorts or pools of cohorts show how occupational mobility is associated with individual-, firm-, occupation-, and industry-level characteristics, as well as overall economic conditions. At the individual level, mobility is generally suppressed by age, work experience, education, and job tenure (Carroll and Mayer 1986; Manzoni, Härkönen, and Mayer 2014; Mayer and Carroll 1987; Robst 1995; Sicherman and Galor 1990). At the occupation level, workers in occupations requiring skills that are easily transferable to other occupations tend to have higher mobility rates (Shaw 1987). Industries with higher rates of turnover and lower rates of growth typically have higher rates of occupational mobility (DiPrete et al. 1997; DiPrete and Nonnemaker 1997). Overall labor market conditions also influence career patterns, depressing occupation switching during recessions and enhancing switching during economic expansions (Blossfeld 1986; Kambourov and Manovskii 2008; Moscarini and Thomsson 2008). This research is invaluable in providing insights into how careers evolve, but it tells us relatively little about large-scale social changes in occupational mobility patterns.

In contrast to these cohort-based studies, we adopt a period approach to consider macro-level changes in mobility patterns. A period approach has been a fixture in studies of trends in intergenerational mobility (e.g., Featherman and Hauser 1978; Hout 1988; Long and Ferrie 2013; Torche 2011), but only two studies have examined period trends in intragenerational mobility since the 1970s. These studies show either a substantial increase in mobility between 1970 and 1997 (Kambourov and Manovskii 2008) or weak positive trends overlaid with pro-cyclical mobility patterns (Moscarini and Thomsson 2008). This prior work eschews the structural analysis of mobility tables common to the sociological literature, exclusively focusing on overall mobility rates. This work ignores a key advantage of the period approach: the ability to examine mobility net of substantial changes in the marginal distributions of occupations that define the opportunity structure for all cohorts (DiPrete and Forristal 1995).1

To put it another way, our period approach allows us to hone in on trends in exchange mobility, separating this key component of mobility from trends in structural mobility. In a trend analysis, structural mobility stems from changes in the sizes of occupational origins and destinations across and within periods. A between-period shift in the distribution of workers toward occupational origins with higher (or lower) rates of mobility will increase (or decrease) overall mobility rates ceteris paribus. For example, a shift away from low-mobility occupations (e.g., lawyers and judges) to higher mobility occupations (e.g., accountants) should yield increased mobility. In addition, periods characterized by greater within-period changes in the occupational structure will have higher rates of mobility. For example, if employment in manufacturing is flat in one period but declines in a subsequent period, the latter period should display higher mobility as workers depart manufacturing occupations and find employment elsewhere. In contrast, exchange mobility indicates mobility net of changes in the occupational structure within and across periods. It tells us, for example, who would be more likely to become an accountant: a former lawyer or a former welder, if each occupation were to contain a fixed number of workers with perfectly balanced employment inflows and outflows. Structural mobility may be overwhelmingly upward or downward, but exchange mobility is directionless: it encompasses upward, downward, and lateral mobility. Finding increasing (or decreasing) exchange mobility would indicate more (or less) circulation between positions in the occupational structure net of changes in that structure.

A few single-period studies of intragenerational mobility address the distinction between structural and exchange mobility (Rosenfeld and Sørensen 1979; Sørensen and Grusky 1996; Stier and Grusky 1990), but prior research on trends in intragenerational mobility ignores the distinction and confounds trends in structural and exchange mobility. This can lead to an overstatement of how mobility chances (i.e., exchange mobility) have changed, or prevent one from seeing changes in mobility chances that are disguised by changes in the occupational structure (Hauser et al. 1975; Sobel, Hout, and Duncan 1985). The intergenerational mobility literature has long looked to exchange mobility as an appropriate indicator of changes in stratification systems. Structural mobility is an important area of research, but we align our inquiry with the intergenerational literature and focus on changes in exchange mobility, and we see whether these trends closely follow trends in gross mobility.

A MULTILEVEL SCHEME FOR DETECTING MOBILITY TRENDS

We use a nested class scheme to examine period trends in exchange mobility at multiple levels of occupational aggregation. There are two ideal-typical approaches to aggregation: big-classes and micro-classes (Jonsson et al. 2009; Sørensen and Grusky 1996; Weeden and Grusky 2005, 2012). Big-classes join together many occupations and aim to represent broad differences in kind in the social relations of production, or in the types of tasks performed by incumbents (e.g., Breen 2004; Erikson and Goldthorpe 1992; Wright and Perrone 1977). Micro-classes are narrowly defined clusters of occupations sharing similar tasks, duties, and responsibilities and around which formal and informal institutions—licensing bodies, trade groups, unions, clubs—have organized (Weeden 2002; Weeden and Grusky 2005).2

In this article, we adopt a micro-meso-macro class scheme developed by Jonsson and colleagues (2009) that integrates the big-class and micro-class views. Jonsson and colleagues’ occupational structure features four nested levels of aggregation: a sectoral level pertaining to the manual-nonmanual divide, within which are nested macro-classes, meso-classes, and micro-classes.3,4 Table 1 illustrates the nesting structure of the occupational classifications with an abbreviated list of the micro-classes.

Table 1.

Macro-, Meso-, and Micro-Class Occupational Schemes

| Sectors (2 categories) |

Macro-Classes (5 categories) |

Meso-Classes (10 categories) |

Micro-Classes (75 categories) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Nonmanual | 11. Professional-managerial | 111. Classical professions | 11101. Jurists |

| 11102. Health professionals | |||

| 11103. Professors and instructors | |||

| … | |||

| 112. Managers and officials | 11201. Officials, government and NGO | ||

| 11202. Other managers | |||

| 11203. Commercial managers | |||

| … | |||

| 113. Other professions | 11301. Systems analysts and programmers | ||

| 11302. Aircraft pilots and navigators | |||

| 11303. Personnel and labor relations workers | |||

| … | |||

| 12. Proprietors | 121. Proprietors | 12101. Proprietors | |

| 13. Routine nonmanual | 131. Sales | 13101. Real estate agents | |

| 13102. Agents, NEC | |||

| 13103. Insurance agents | |||

| … | |||

| 132. Clerical | 13201. Telephone operators | ||

| 13202. Bookkeepers | |||

| 13203. Office and clerical workers | |||

| … | |||

|

| |||

| 2. Manual | 24. Non-farm manual | 241. Craft | 24101. Craftsmen, NEC |

| 24102. Foremen | |||

| 24103. Electronics service and repair | |||

| … | |||

| 242. Lower manual | 24201. Truck drivers | ||

| 24202. Chemical processors | |||

| 24203. Miners and related workers | |||

| … | |||

| 243. Service workers | 24301. Protective service workers | ||

| 24302. Transport conductors | |||

| 24303. Guards and watchmen | |||

| … | |||

| 25. Primary | 252. Farmers, fishermen, and other primary | 25201. Farmers, fishermen, and hunters | |

| 25202. Farm labours | |||

Note: This occupational scheme is adapted from Jonsson and colleagues (2009). A full list of the micro-classes is included in Table S2 in the online supplement and the descriptive statistics are presented in Table S3. Jonsson and colleagues’ scheme originally included two meso-classes in the primary macro-class: 25201. fisherman and hunters and 25202. farming. The PSID contained very few fishermen and hunters, so we aggregated these micro-classes with the farmers micro-class.

Our decision to use Jonsson and colleagues’ scheme is driven by our expectation that some of the macro-economic trends affecting the U.S. labor market, discussed in greater detail in the following sections, have produced different mobility trends at different levels of aggregation. The nesting of the micro-meso-macro scheme allows us to differentiate between micro-class mobility within narrow meso-classes (e.g., short-distance mobility between professor and engineer) and mobility between meso-classes, macro-classes, and sectors (e.g., long-distance mobility between professor and sales worker). This allows us to decompose mobility rates to show the extent to which changes in mobility are occurring at the macro-, meso-, and micro-levels, and whether these changes are moving in the same directions.

The nested class scheme offers two additional advantages. First, it provides insight into whether changes in mobility chances are shifting for vertical or lateral dimensions of the mobility table. For example, if changes in mobility predominantly stem from increasing mobility between macro-classes, but with constant mobility within meso-classes, the result would suggest that lateral relationships between micro-classes (within meso-classes) are holding, but that vertically arranged macro-classes are becoming less coherent. Second, the multilevel scheme is sufficiently disaggregated to allow us to discern persistence in relatively detailed occupations, a likely consequence of job immobility. Failing to account for occupational persistence at the disaggregated micro-class level may cause us to misattribute micro-class persistence to persistence at the level of meso- or macro-classes. This misattribution could confound our attempts to relate observed mobility trends to recent changes in the U.S. economy.

INTRAGENERATIONAL MOBILITY AND MACRO-SOCIAL CHANGES

The United States has experienced dramatic changes in macro-social conditions over the past four decades, all of which might bear on trends in intragenerational occupational exchange mobility. We review these changes in terms of macro-level shifts in (1) the social and demographic composition of the labor force, (2) technologies and employment relationships in the workplace, and (3) industrial structures. Our goal is not to assemble specific, testable hypotheses based on explicit measures of these phenomena—the temporal pattern is not yet well established—but to situate possible changes in mobility against the backdrop of broader shifts in the labor market.

Changing Labor Force Composition

The United States labor force has become older, more educated, and more female since the 1970s. Cohort studies suggest that these compositional shifts should change patterns of occupational mobility. First, the gradual aging of the U.S. labor force would suggest declining occupational mobility. The proportion of the working-age population older than 55 has increased from 15 to 19 percent for men and 13 to 20 percent for women from 1980 to 2010 (Lee and Mather 2008; U.S. Census Bureau 2012). Micro-economic models of job and occupational mobility suggest that this aging should lead to less mobility across levels of the class structure, as older workers with longer job tenures may avoid risk more than younger workers, and enjoy less time over which to realize returns from new occupational investments (Miller 1984; Mincer and Jovanovic 1981; Neal 1999). In contrast, sociological theories of vacancy chains suggest that labor force aging can spur mobility in some circumstances, as retirements among older workers create occupational vacancies for younger workers to fill, resulting in cascades of mobility events (e.g., Chase 1991; Sørensen 1974, 1975; White 1970). Our study covers the prime working (i.e., pre-retirement) ages of the baby boom generation. We thus expect the mobility suppressing effects of age to dominate, leading to declining mobility across all levels of occupational aggregation.

Increasing levels of educational attainment in the United States labor force also suggest declining mobility, although with subtle differences between genders. College completion rates rose for young men and women during the 1960s, with men enjoying a distinct advantage. However, while college completion rates among men topped out in the mid-1970s and stagnated until the late-2000s, completion rates continued to rise for women throughout the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s, surpassing the rate for men in the 1990s (Bailey and Dynarski 2011; DiPrete and Buchmann 2006; Ryan and Bauman 2016). Both economic and sociological research suggests that higher educational attainments, involving greater pre-labor market investments in training and human capital as well as better chances of obtaining a job match, lead to less mobility across jobs and occupations (e.g., Mincer and Jovanovic 1981; Robst 1995; Rosen 1972; Sicherman and Galor 1990; Sørensen and Grusky 1996; Stier and Grusky 1990). Net of changes in the occupational structure, we expect rising levels of education will tend to reduce mobility rates at all levels of aggregation, perhaps more so for women because they have experienced more consistent increases in educational attainment.

Finally, labor force participation among women continued its long-run, twentieth-century increase through the 1970s and 1980s before plateauing in the 1990s (Juhn and Potter 2006; Killingsworth and Heckman 1986). How increasing labor force participation has affected mobility for women will depend on new participants’ educational attainments, their labor force commitments, and shifting barriers to occupational entry (Farber 1994; Felmlee 1982; Hollister and Smith 2014). Such trends might also influence men’s labor market experiences and job mobility, because of the widely observed phenomena of labor supply adjustment within couples and risk pooling within families (Cheng 2016; Chiappori 1992; Killingsworth 1983; Western et al. 2012). It is difficult to generate a priori expectations as to how increasing female labor force participation would affect mobility for women and men. At the very least, the trends militate against pooling men and women in our analysis. We thus analyze men and women separately.

Changing Employment Relationships

The changing composition of the labor force coincided with changes in work conditions at “the site of production” (Weeden and Grusky 2005:142). Weeden and Grusky (2012) argue that recent economic and social trends have reduced the institutional hold of highly aggregated classes, but that selection into occupations and workplaces, and socialization in these units of labor market organization, have allowed micro-classes to maintain an institutional hold on their incumbents. Empirically, these trends have resulted in declining homogeneity of workers’ social characteristics—their “life chances, attitudes, behaviors, and consumption practices” (Weeden and Grusky 2012:1726)—within macro-classes, but stability within micro-classes. Weeden and Grusky’s findings do not address mobility, but they suggest a restructuring of relationships among workers and between workers and employers that, at the very least, undermines career retention in aggregated classes. In our view, this restructuring involves three important changes.

First, recent decades have seen a dramatic influx of new computer and automation technologies into the workplace (Autor et al. 2003; Cappelli 1993; Green, Felstead, and Gallie 2003; Kristal 2013; Spitz-Oener 2006). Scholars of skill-biased technological change argue that computer technologies complement nonroutine cognitive tasks and replace routine cognitive tasks, while mechanical automation continues to displace routine manual tasks (Goldin and Katz 1998). We are not aware of any cohort studies that examine how technological changes in the workplace have influenced mobility for occupational incumbents, but we tentatively draw out two implications. First, the increasing prevalence of computer technologies has made computer use a common denominator across many occupations, potentially creating a new set of transferable skills and weakening barriers to mobility (Shaw 1987). Yet, technological change also may have created a digital divide between highly skilled and unskilled/semiskilled workers, creating distinctions between workers who design and maintain computer architectures, or use these architectures for analytic tasks, and workers who are primarily operators, like data entry clerks or cashiers. These two considerations lead us to expect lower mobility across sectors and macro-classes, but increasing mobility between closely related micro-classes nested in the same meso-classes.

Declining union membership also may have affected mobility, especially for workers in the private sector (Farber and Western 2001; Kristal and Cohen 2015; Rosenfeld 2014). Private sector union membership rates declined from 33 percent in the early 1970s to less than 10 percent in the mid-2000s (Western and Rosenfeld 2011). Unionization has traditionally been an occupational closure strategy that protects the positions and wages of occupational incumbents (Weeden 2002). Unions have offered benefits, set predictable wage grades, and insulated workers from turbulent labor markets (Rosenfeld 2014). One effect of these worker protections is to reduce rates of job mobility (Mincer 1983). We expect that by eroding institutional worker protections and attenuating workers’ attachments to jobs and industries, de-unionization has led to greater likelihood of short-range occupational switching between micro- and meso-classes within the manual sector, where union density has undergone the most change. It is unclear if de-unionization should affect switching across the manual/nonmanual divide.

Related to de-unionization, forms of precarious labor have been gradually spreading to many classes of workers (Kalleberg 2009, 2011). Contract, fixed-term, temporary, and part-time work all stand under the precarious work banner and are generally on the rise, especially for workers with few labor market resources (Hollister 2011; Valletta and Bengali 2013). Many workers can no longer work for the same employer for decades, but have to change employers frequently to build careers (Kronberg 2013). The advent of precarious labor may increase rates of occupational mobility through at least two channels. On the one hand, the expiration of employment contracts forces workers to make job and employer switches, with each switch entailing some risk of occupational mobility. On the other hand, precarious job conditions may destabilize gradual and predictable patterns of human capital accumulation and career development, while simultaneously short-circuiting the accumulation of job tenure—a strong predictor of immobility (Farber 1999). Increasing prevalence of temporary and short-term contracts thus suggests rising occupational mobility, potentially across all classes and at all levels of aggregation.

Changing Industrial Structure

Changing employment relationships have accompanied a broader shift in the U.S. industrial and occupational structure. Manufacturing occupations have undergone a long-term and persistent decline, while service, professional, and technical occupations have grown (Dwyer 2013; Featherman and Hauser 1978; Lee and Mather 2008). A considerable literature in labor economics examines how skill-biased technological change has induced changes in the occupation structure (Acemoglu 2002; Autor et al. 2003; Card and DiNardo 2002). These changes should manifest primarily in the form of structural mobility, which is not the focus of the present study.

Economic research has also examined how globalization—including international offshoring, import penetration, and international migration—has been a force in reshaping the U.S. labor market. International trade has substantial negative effects on employment in manufacturing and related occupations (Autor, Dorn, and Hanson 2013; Berman, Bound, and Griliches 1994), but it also affects employment in professional, technical, and clerical occupations (Ebenstein et al. 2013; Goos, Manning, and Salomons 2014). Immigration is another key aspect of globalization’s impact on the U.S. labor market. As select work activities have been offshored, the United States has also received a large number of foreign workers, primarily from countries in Asia and Latin America (Pew Research Center 2015). Immigrants, especially those arriving since 1970, have been highly polarized in education and expertise, flowing into occupations at both the bottom and top of the skill distribution (Portes and Rumbaut 2014). Previous work has extensively discussed the wage and unemployment consequences of rising international trade and immigration for native workers, but much of this research focuses on overall changes in labor market opportunities for natives, including changes in the occupational structure, rather than flows of native workers among specific occupations (for a review, see Okkerse 2008). The available evidence is suggestive of mobility effects, but it is too thin to offer much guidance for how globalization has affected patterns of exchange mobility.

Finally, decreases in the segregation of men and women across occupations at the end of the twentieth century have uncertain implications for changes in mobility for both genders (Bielby and Baron 1986; Blau et al. 2012; Jacobs 1989; Reskin 1993). On one hand, declining gender segregation suggests declining barriers to occupational mobility for women, and therefore increasing exchange mobility. On the other hand, women entering male-dominated occupations often find persistence difficult (Cha 2013; Maume 1999; Torre 2014). Increasing representation of women in (some) traditionally male-dominated occupations may have increased retention rates for women in these occupations, and hence reduced exchange mobility for women. No existing studies show how changes in gender segregation are altering mobility chances for men. As with rising female labor force participation, these gendered changes in the economy lead us to provide separate descriptions of mobility for men and women.

Table 2 provides an overview of these rough expectations. To summarize, previous studies suggest that labor force aging and rising educational attainment might reduce exchange mobility at all levels of aggregation across the occupational distribution. In the workplace, technological change, de-unionization, and precarious labor suggest increasing exchange mobility within meso- and macro-classes, but with conflicting implications for changes in long-range mobility across macro-classes and sectors. Globalization and skill-biased technological change should increase structural mobility, but it is unclear what their implications are for changes in exchange mobility. Finally, the role of decreasing gender segregation in shifting exchange mobility for women is ambiguous.

Table 2.

Summary of Possible Exchange Mobility Trends Resulting from Macro-Social Change

| Level of Class Aggregation | ||

|---|---|---|

|

|

||

| Sector or Macro- Class Mobility |

Meso- or Micro- Class Mobility |

|

| Changing Labor Force Composition | ||

| Labor force aging | − | − |

| Increasing levels of educational attainment | − | − |

| Rising female labor force participation | 0 | 0 |

| Changing Employment Relationships | ||

| Technological change | − | + |

| De-unionization | ? | + |

| Precarious labor | + | + |

| Changing Industrial Structure | ||

| Globalization | ? | ? |

| Occupational gender segregation | ? | ? |

Note: + indicates that the macro-social change would likely increase mobility, − indicates that the change would likely lead to a decrease in mobility, 0 indicates no change, and ? indicates that the effect on mobility is indeterminate.

DATA, SAMPLE, AND MEASURES

Data

We pool data from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID) to assess the trend in intragenerational occupational mobility (Institute for Social Research 2015).5 The PSID survey asked household heads and wives to report their occupations every year from 1968 to 1997 and biennially thereafter. These data have been coded into detailed Census categories, with the data for 1968 to 1980 only recently coded as part of a retrospective project. Whereas most studies use the PSID dataset for longitudinal analysis by restricting the sample to include only those respondents who are followed over years, we use it as repeated cross-sectional data by including both followable and non-followable sample members. These data provide a representative picture of the nonimmigrant U.S. population in each year because of the PSID rules for sampling individuals and families (Institute for Social Research 2013).6

Sample

We draw on PSID data from the years 1969 to 2011. We use only the baseline PSID samples, dropping observations from the immigrant and Hispanic supplementary samples. Because the PSID sampling design changed from annual to biennial in 1997, we keep only odd years in our sample, and we additionally limit the sample to individuals reporting occupations at both the beginning and end of each resulting two-year interval.7 Instead of measuring intragenerational mobility by first job to current job, a common approach adopted in previous mobility studies based on cross-sectional data (e.g., Blau and Duncan 1967; Featherman, Jones, and Hauser 1975; Sørensen and Grusky 1996), we fix the time interval between the occupational origin and destination at two years. One reason we use a fixed interval is that with the increase in college attendance and completion over the past several decades, the time difference between first and current jobs for individuals at a given age has supposedly declined as individuals extend the number of years spent in school.

We restrict our analysis to male and female workers who were 25 to 64 years old at the beginning of each two-year interval. We reweight our sample by age and race within sex groups based on the 1970, 1980, 1990, 2000, and 2010 Census counts for employed individuals born in the United States or arriving to the United States prior to 1970, with interpolation of counts in intercensal years (Ruggles et al. 2015). For analysis, we add a very small number (i.e., .01) to cells with zeros, under the assumption that these are sampling zeros and not structural zeros.8

Measures

We code each worker’s occupation at the beginning and end of each two-year interval into Jonsson and colleagues’ micro-meso-macro scheme to obtain occupational codes that are consistent across the study period. To take an example, the 1970 occupation codes for bulldozer operators, cranemen, derrick-men, hoist men and excavating, grading, and road machine operators are grouped into a “heavy machine operators” micro-class, which is nested in the craft meso-class, the nonmanual macro-class, and the nonmanual sector. We omit the 2001 to 2003 interval from our mobility table analysis because of the PSID’s switch from 1970 to 2000 Census occupation codes in the 2003 survey year. Besides switching between occupational codes, the PSID also changed its coding procedures over time. Table S1 in the online supplement summarizes these changes. In particular, 1969 to 1977 shows systematically lower mobility compared to the other years primarily because the detailed occupation codes in these years were assigned as part of a retrospective coding project that used a dependent coding procedure. We include 1969 to 1977 in our tables and figures, but our interpretation focuses on 1979 and later years.

Because of the limited number of biennial observations, we represent the time dimension with five periods aggregated based on the year when the occupational origin is measured: 1969 to 1977, 1979 to 1985, 1987 to 1993, 1995 to 1999, and 2003 to 2009. These periods roughly correspond to different economic and political eras in the United States: the era of stagflation, the Reagan administration, the pre- and post- 1990 to 1991 recession era, the Clinton economic expansion, and the post-9/11 years. From a practical point of view, these periods are of roughly equal length. We also combine survey years with consistent Census occupation codes and coding procedures.

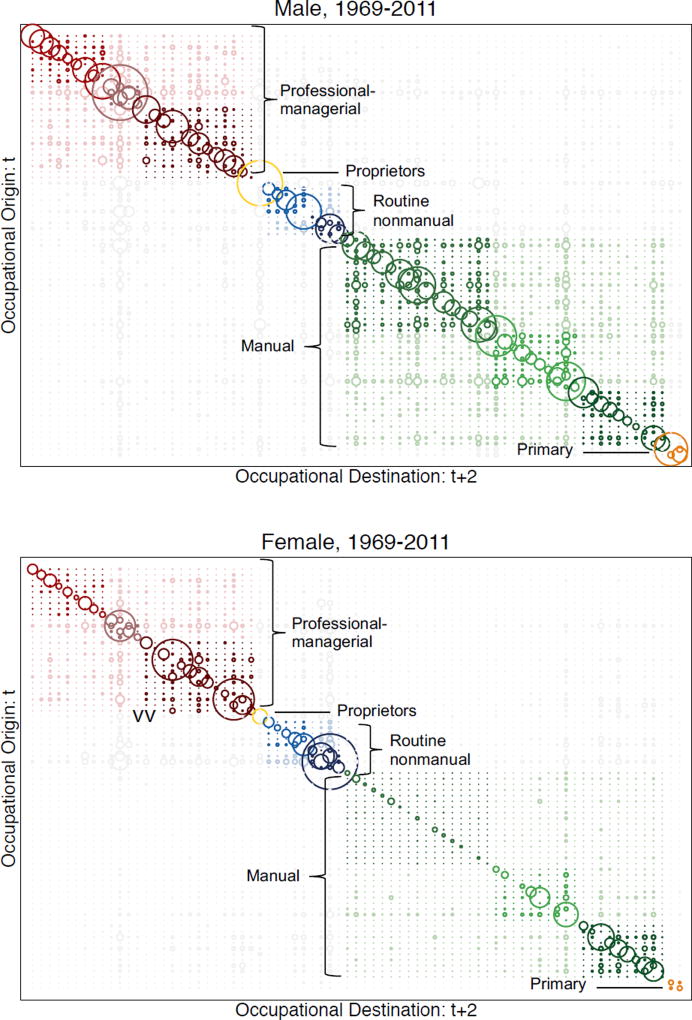

We collapse the two-year mobility data into separate mobility tables by period and, to test trends separately for men and women, by gender.9 Figure 1 displays the intragenerational mobility matrices over all years. Each circle represents a cell in the mobility table, with the size of the circle determined by the number of individuals in the origin-destination micro-class pair. The circle shades indicate different levels of aggregation. Darker shades are micro- and meso-classes, and lighter shades are higher levels of aggregation. A comparison of the two graphs suggests that occupational distributions differ by gender, with women much less likely to engage in certain occupations, such as those in the manual macro-class. Also, more men than women are located on the diagonal of the graphs, suggesting that micro-class immobility is more prevalent among men. We discuss trends in these occupational mobility tables in the next section.

Figure 1. Observed Intragenerational Mobility by Pooling All PSID Years.

Note: Macro-class occupations are labeled in the graph. Occupations with various shades within the same macro-class refer to different meso-classes. The 10 meso-class clusters from top to bottom include classical professions, managers, other professions, proprietors, sales, clerical, craft, lower manual, service workers, and farmers. The size of the circles is proportionate to the number of workers within each origin-destination pair of micro-classes.

TRENDS IN GROSS MOBILITY

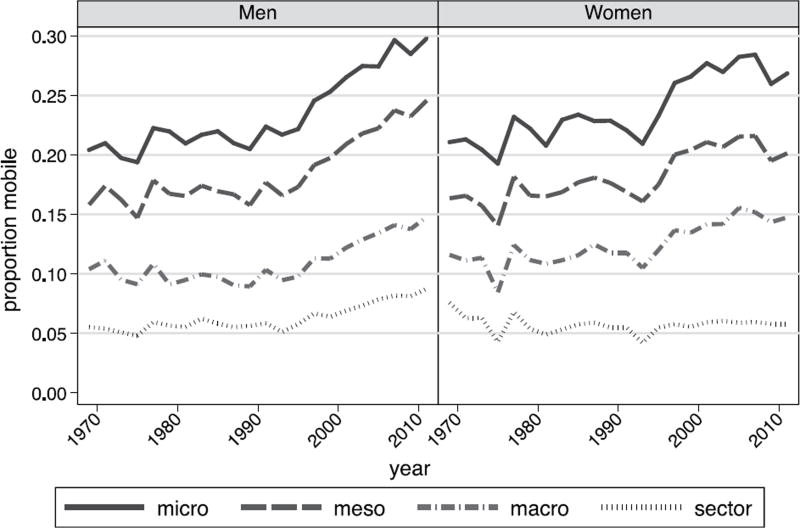

We begin by confirming and extending previous evidence of rising gross mobility (i.e., the proportion of workers switching occupation) for men and women in the PSID (Kambourov and Manovskii 2008). This analysis ignores the difference between structural and exchange mobility, but in this section we also develop a decomposition that helps us consider mobility trends across different levels of aggregation in subsequent exchange mobility analyses. Figure 2 depicts a steady increasing trend since the 1990s for both men and women at almost all levels of aggregation. We adjusted these trend lines for changes in the PSID’s coding procedures using an “affine shift” method detailed in the online supplement. The lines for meso- and macro-classes reflect trends similar to those that would be calculated based on conventional big occupational classes (e.g., EGP class). Focusing on trends in micro-class mobility, we find that the proportion of occupational switchers among men increased by nearly 10 percentage points, which represents a substantial proportional increase in mobility rates of approximately 50 percent. Among women, the increase in mobility is similar. The trends are roughly consistent across different levels of aggregation, although the trend disappears for women when we define occupations by the highly aggregated manual-nonmanual binary. Finally, the figure shows how mobility rates are lower at higher levels of occupational aggregation, and less aggregation allows us to observe more mobility.

Figure 2. Trends in Intragenerational Gross Mobility Rates by Gender, 1969 to 2011.

Data source: Panel Study of Income Dynamics, 1969 to 2011.

Note: The trends refer to adjusted mobility rates estimated after removing the effect of potential measurement errors caused by coding procedures (“affine shift” method). We adjust mobility rates to what would have been expected for dependent coding procedures, as discussed in the online supplement. The trends show gross (or crude) mobility for men and women based on occupational schemes that vary by levels of aggregation.

We use the nested design of our class scheme to decompose the gross-mobility shown in Figure 2 into mobility across multiple levels of aggregation. First, let YMicro, YMeso, YMacro, and YM/NM be indicator variables taking the value 1 if a worker changed occupation at the given level of occupational aggregation and 0 otherwise. Second, observe that the sum of the mobility probabilities and the micro-class immobility probability must be one:

where the overall probability of mobility is expressed as the sum of mobility probabilities at the micro-class, meso-class, macro-class, and sectoral levels. Note that mobility between aggregated classes requires mobility between less aggregated classes as well (but not vice versa), and thus many terms implied by the above equation are inherently zero. For example, it is not possible for a worker to change his macro-class but not his meso-class, namely,

Therefore, the above equation can be reduced to Thus, the gross mobility is a mixture of (2) mobility between micro-classes within meso-classes (net micro-class mobility); (3) mobility between meso-classes within macro-classes (net meso-class mobility); (4) mobility between macro-classes within manual or nonmanual sectors (net macro-class mobility); and (5) mobility between manual and nonmanual sectors (net manual/nonmanual mobility).

Table 3 provides a picture of rising mobility chances based on calculating net mobility probabilities by period and gender. The percentage of workers who stay in the same micro-class during a two-year observation interval declined from 1969 to 2009 for both men and women. The most dramatic decline happened during the 1969 to 1977 and 1979 to 1985 periods. Much of this change is likely attributable to the PSID’s switch from dependent to independent occupation coding. But even after excluding observations before 1979, we still observe a decline in immobility rates of 8.8 percentage points for men and 7.5 points for women from the 1979 to 1985 period to the 2003 to 2009 period. Among respondents who changed their occupations at the micro-class level, the percentage of mobility occurring between micro-classes within meso-classes slightly increased from 8.5 to 9.5 percent for men and fluctuates between 7.6 and 9.0 percent for women from the 1980s to the 2010s. For both sexes, we observe more notable increases in meso-class mobility within macro-classes, macro-class mobility within manual/nonmanual sectors, and mobility across the manual/nonmanual divide regardless of whether the 1969 to 1977 period is included. Together, these descriptive trends suggest that increasing intragenerational occupational mobility is driven by increases at almost all levels of aggregation, but especially increasing medium- and long-range mobility between meso-classes, macro-classes, and sectors.

Table 3.

Decomposition of Gross Mobility Rates

| Levels of Mobility | Period | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||||||

| Manual | Macro | Meso | Micro | 1969 to 1977 |

1979 to 1985 |

1987 to 1993 |

1995 to 1999 |

2003 to 2009 |

|

| Men | |||||||||

| (1) Immobility | No | No | No | No | 79.4 | 64.6 | 64.5 | 59.7 | 55.8 |

| (2) Net micro-class mobility | No | No | No | Yes | 4.2 | 8.5 | 8.5 | 9.3 | 9.5 |

| (3) Net meso-class mobility | No | No | Yes | Yes | 6.1 | 10.4 | 10.4 | 11.5 | 12.9 |

| (4) Net macro-class mobility | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | 4.8 | 6.2 | 6.6 | 7.5 | 8.1 |

| (5) Net manual/nonmanual mobility | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 5.4 | 10.3 | 10.1 | 12.0 | 13.7 |

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||||

| N | 10,481 | 10,388 | 12,685 | 8,596 | 14,050 | ||||

| Women | |||||||||

| (1) Immobility | No | No | No | No | 78.9 | 67.5 | 67.5 | 62.2 | 60.0 |

| (2) Net micro-class mobility | No | No | No | Yes | 4.9 | 8.2 | 7.6 | 9.0 | 8.3 |

| (3) Net meso-class mobility | No | No | Yes | Yes | 5.2 | 7.0 | 6.7 | 7.9 | 9.3 |

| (4) Net macro-class mobility | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | 4.8 | 10.2 | 11.2 | 13.1 | 12.9 |

| (5) Net manual/nonmanual mobility | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 6.2 | 7.1 | 7.0 | 7.8 | 9.5 |

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||||

| N | 7,534 | 7,933 | 10,564 | 7,585 | 13,564 | ||||

Data source: Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID), 1969 to 2011.

Note: We restrict the sample to the employed population age 25 to 64, excluding the military, unemployed, student, disabled, housekeeper, and retired populations from the analysis. The years shown for each period correspond to the starts of the two-year intervals making up the period. We dropped the 2001 to 2003 interval because of PSID’s switch from 1970 to 2000 occupation codes in this interval.

MODELING TRENDS IN EXCHANGE MOBILITY

The descriptive analyses only show mobility trends resulting from the combination of structural and exchange mobility. We implement topological, “overlapping persistence” (Stier and Grusky 1990) models to explicitly test whether descriptive mobility trends still hold after we control for marginal changes in occupational distributions. Our main aim is to test a model of no exchange mobility trend against a model that allows for differences in exchange mobility over time. We describe the model specifications in more detail below.

A Topological Mobility Model

We first posit a baseline model that assumes patterns of exchange mobility have not changed over time, while accounting for changes in the marginal distributions of occupations within and across periods. Model 2, presented in Table 4, corresponds to this constant-association-over-time model. It includes all two-way interactions among micro-class occupational origin, occupational destination, and period dummy variables. Model 2 builds on two, more parsimonious models, also shown in Table 4—Model 0 that omits all two-way interactions, and Model 1 that omits the two-way interaction between occupational origin and destination. Model 2 takes the following log-additive form:

| (1) |

where i indexes occupational origins, j indexes destinations, and t indexes periods with five categories. Fijt refers to the expected value in cell ijt. The parameter μ refers to the overall mean, and μi, μj, and μt refer to origin, destination, and period marginal effects, respectively. The parameters μit and μjt are time-varying origin and destination marginal effects that capture structural mobility caused by changes in the relative sizes of micro-classes. μij refers to the occupation origin-destination association effect capturing the time-constant pattern of exchange mobility. Because the two-way interaction, μij, involves too many parameters, and many of these parameters fall on cells with zero counts, we simplify the full occupational origin-destination interactions with four topological matrices:

| (2) |

The term refers to micro-class immobility parameters covering the micro-class diagonal; the term refers to net micro-class mobility parameters, which capture mobility within meso-classes. We specify distinct net micro-class mobility parameters for each meso-class. The term refers to net meso-class mobility within macro-classes, with a unique parameter for each macro-class. Finally, the term denotes unique net macro-class mobility parameters for the manual and nonmanual sectors. Because of the constraint that the sum of the micro-level immobility probability and net mobility probabilities equals 1, we need to choose one reference group. Thus, we omit the manual/nonmanual mobility term. Model fit statistics (not shown) suggest that the model in Equation 2 provides a reasonable and substantially more parsimonious fit than that in Equation 1. Table S10 in the online supplement provides an illustrative sketch of the model design matrix.

Table 4.

Log-Linear Model Fit Statistics

| Model | df | L2 | p-value | BIC | Δ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men (N = 56,200) | |||||

| Baseline Models | |||||

| 0a: Origin + Destination + Period | 27,972 | 244,675 | <.01 | −61,245 | 69.0 |

| 1a: 0a + Origin×Period + Destination×Period | 27,380 | 239,997 | <.01 | −59,449 | 68.5 |

| 2a: 1a + Parameter-ABCD | 27,292 | 27,431 | .28 | −271,052 | 18.2 |

| Period-Varying Topological Mobility Models | |||||

| 3a: 2a + Period×Parameter-A | 26,992 | 24,874 | >.99 | −270,328 | 14.2 |

| 4a: 2a + Period×Parameter-AB | 26,956 | 24,723 | >.99 | −270,086 | 14.1 |

| 5a: 2a + Period×Parameter-ABC | 26,944 | 24,661 | >.99 | −270,017 | 14.1 |

| 6a: 2a + Period×Parameter-ABCD | 26,940 | 24,648 | >.99 | −269,986 | 14.1 |

| 7a: 2a + Period×Parameter-A'B'C'D' | 27,276 | 25,659 | >.99 | −272,650 | 16.0 |

| Women (N = 47,180) | |||||

| Baseline Models | |||||

| 0b: Origin + Destination + Period | 27,972 | 174,593 | <.01 | −126,434 | 66.6 |

| 1b: 0b + Origin×Period + Destination×Period | 27,380 | 166,191 | <.01 | −128,465 | 65.7 |

| 2b: 1b + Parameter-ABCD | 27,292 | 19,635 | >.99 | −274,074 | 15.2 |

| Period-Varying Topological Mobility Models | |||||

| 3b: 2b + Period×Parameter-A | 26,992 | 18,287 | >.99 | −272,193 | 12.3 |

| 4b: 2b + Period×Parameter-AB | 26,956 | 18,154 | >.99 | −271,939 | 12.2 |

| 5b: 2b + Period×Parameter-ABC | 26,944 | 18,102 | >.99 | −271,862 | 12.1 |

| 6b: 2b + Period×Parameter-ABCD | 26,940 | 18,077 | >.99 | −271,844 | 12.1 |

| 7b: 2b + Period×Parameter-A'B'C'D' | 27,276 | 18,879 | >.99 | −274,657 | 13.9 |

Data source: Panel Study of Income Dynamics, 1969 to 2011.

Note: L2 is the log-likelihood ratio chi-square statistic with the degrees of freedom (df) reported in column df. The Bayesian Information Criteria (BIC) = L2 − (df)×log(N), where N is the total number of observations. A: micro-class immobility parameters; B: net micro-class mobility within meso-class parameters; C: net meso-class mobility within macro-class parameters; D: net macro-class mobility within manual/nonmanual sector parameters. Period×Parameter-: interaction between period and mobility parameters. A', B', C', and D' indicate that trend parameters are constrained to be equal across classes at the micro-class, meso-class, macro-class, and sectoral levels, respectively.

We use Models 3, 4, 5, and 6 to test for evidence of changes in exchange mobility across periods. These models incorporate time-varying occupation origin-destination association parameters. They take the following form:

| (3) |

Here the parameters , and allow us to test whether micro-class immobility, net micro-class mobility, net meso-class mobility, and net macro-class mobility are changing over time, respectively. Because job persistence, and hence micro-class persistence, is such a key aspect of intragenerational mobility, we layer in period-varying topological parameters from the bottom up. Model 3 adds period-varying micro-class immobility effects ( ); Model 4 adds period-varying net micro-class mobility effects ( ); Model 5 adds period-varying net meso-class mobility effects ( ); and Model 6 adds period-varying net macro-class mobility effects ( ). Table 4 distinguishes identical model specifications fit separately to data for men and women using the suffixes “a” and “b,” respectively.

Model Fit

We use three statistics that are commonly used as criteria for assessing model fit in the stratification literature (Hout 1983). L2, also commonly known as the model deviance, can be used to perform chi-square tests of model fit. An insignificant test statistic suggests that the more parsimonious model is preferred. BIC provides an alternative indicator of fit that is more stringent than L2 because it penalizes models that use large numbers of parameters. Smaller BIC values indicate better fit. Finally, Δ is the dissimilarity index, which runs from 0 to 100, with values closer to zero indicating better agreement between the model and the data.

According to BIC, Models 7a and 7b, which constrain the period differences to be the same across classes at each level of aggregation, are the most strongly favored among all the models.10 However, L2 and Δ favor Models 6a and 6b, more complicated models that assume period heterogeneity across occupational classes. In the sections that follow, we focus on Models 6a and 6b, which allow us to examine whether there has been polarization in mobility chances across different occupations at each level of aggregation.11

RESULTS

Overall, results from our preferred models (Table 4, Models 6a and 6b) suggest that intragenerational occupational mobility is changing across periods, even after controlling for potentially confounding structural mobility. But the model fit statistics do not tell us directly whether mobility is increasing, decreasing, or fluctuating, or which occupations and which levels of aggregation are most strongly affected. To this end, we present mobility changes graphically, in terms of both observed and counterfactually predicted mobility rates. We estimated the observed mobility rates from model coefficients in Models 6a and 6b, which perfectly match the observed levels of net mobility for each sex in each period. We obtained counterfactual mobility rates by assuming the occupational structure remained fixed as observed in the 1979 to 1985 period, and only the exchange mobility coefficients evolved over time.12 Overall, we find evidence of declining micro-class persistence, but not simply because of substantial increases in mobility between micro-classes within meso-classes. Instead, mobility between meso-classes, macro-classes, and sectors has been on the rise. Close alignment between observed and counterfactual mobility suggests that changes in exchange mobility are driving these patterns.

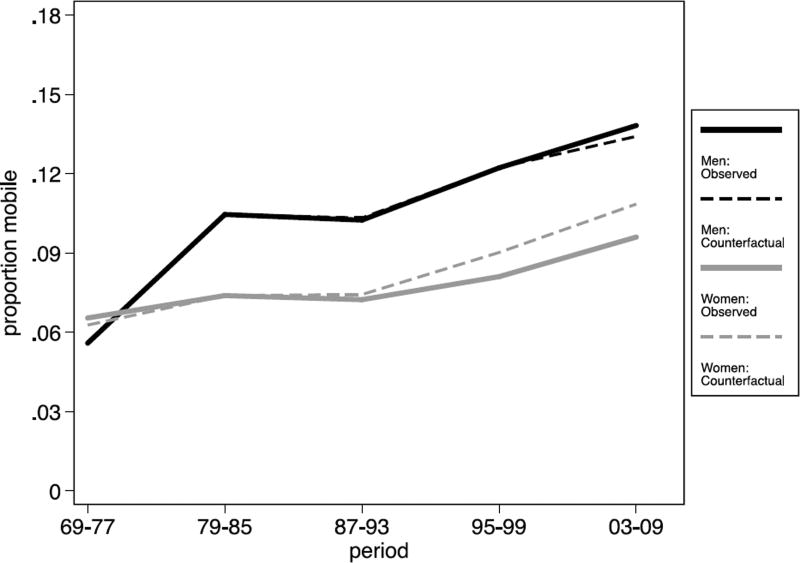

Trends in Mobility between Manual and Nonmanual Sectors

The trend in mobility between manual and nonmanual sectors is increasing for both men and women, indicating more switching back and forth between sectors. Figure 3 depicts the trend from 1969 forward, but as discussed earlier, changes in PSID coding procedures make comparisons between 1969–1977 and later periods suspect. Whether we ignore the first period or not, Figure 3 clearly shows an increase in between-sector mobility that is most pronounced from 1987 onward. Observed rates of sectoral mobility increased from approximately 10 percent to nearly 14 percent for men, and from just above 7 percent to about 9.5 percent for women between the 1979–1985 and 2003–2009 periods. Once we account for changes in the marginal distributions (the dotted, counterfactual lines in Figure 3), the trend for women is more pronounced, and the trend for men is mostly unaffected. These trends suggest that changes in the distribution of women across occupations (i.e., structural mobility) have partly obscured increases in exchange mobility for women.

Figure 3. Trends in Observed and Counterfactual Intragenerational Mobility between Manual and Nonmanual Sectors by Gender.

Data source: Panel Study of Income Dynamics, 1969 to 2011.

Note: Proportion mobile is the share of persons moving between manual and nonmanual sectors over two-year mobility intervals within the periods indicated on the x-axis. The years correspond to the starts of the two-year intervals making up the period. The 2001 to 2003 interval is omitted because of PSID’s switch from 1970 to 2000 occupation codes in this interval. The solid lines correspond to predictions from the full model, which fit observed mobility. The dashed lines are based on counterfactual predictions in which the relative mobility rates are fixed at levels predicted in each period, but the marginal distributions of origin and destination occupations are fixed at levels observed in the 1979 to 1985 period. Margins are treated separately for men and women.

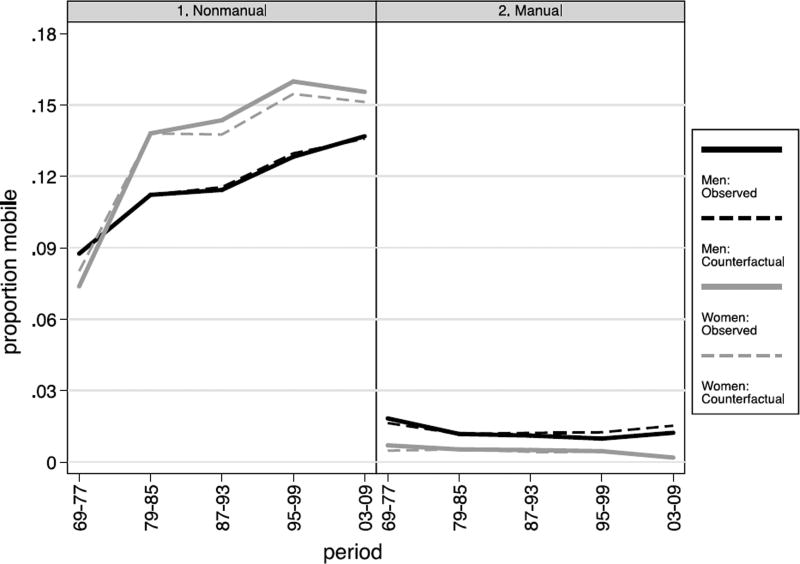

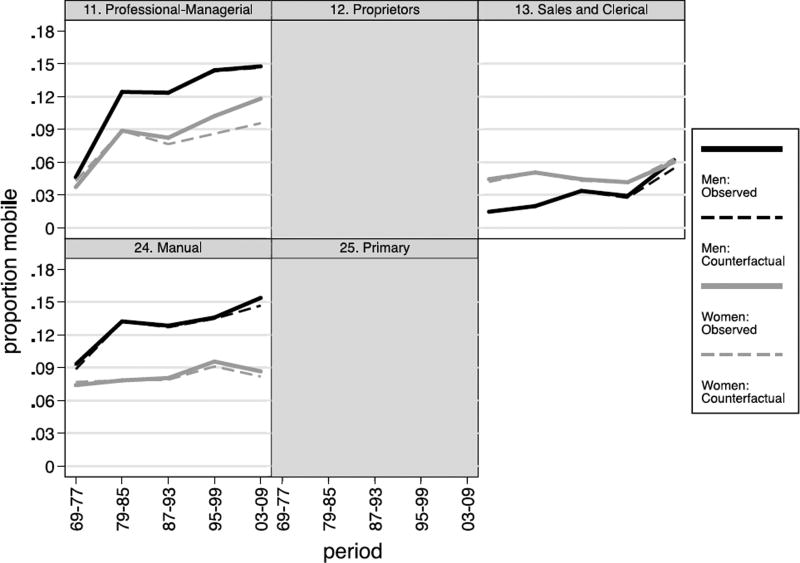

Trends in Net Macro-Class Mobility

Figure 4 presents net macro-class mobility trends calculated for the observed data and in our counterfactual scenarios with the margins fixed at the 1979 to 1985 levels. Net macro-class mobility includes mobility between three macro-classes (professional-managerial, proprietor, and sales and clerical) within the nonmanual sector, and between two macro-classes (manual and farming) within the manual sector. This includes both upward and downward mobility (e.g., moving from professional-managerial occupations to sales and clerical occupations, and in the other direction). Both observed and counterfactual mobility for men and women suggest increasing mobility between macro-classes within the nonmanual sector, but low and relatively flat mobility chances between macro-classes within the manual sector.

Figure 4. Trends in Observed and Counterfactual Net Intragenerational Mobility between Macro-Classes (within Sectors) by Gender.

Data source: Panel Study of Income Dynamics, 1969 to 2011.

Note: Proportion mobile is the share of persons with the given sector origins moving between macro-classes within those sectors over two-year mobility intervals within the periods indicated on the x-axis. The years correspond to the starts of the two-year intervals making up the period. The 2001 to 2003 interval is omitted because of PSID’s switch from 1970 to 2000 occupation codes in this interval. The solid lines correspond to predictions from the full model, which match the observed data. The dashed lines are based on counterfactual predictions in which the relative mobility rates are fixed at levels observed in each period, but the marginal distributions of origin and destination occupations are fixed at the numbers observed in the 1979 to 1985 period. Margins are treated separately for men and women.

In the nonmanual sector, increases in net macro-mobility differ somewhat between men and women. For men, we observe a monotonic increase in mobility between macro-classes. Between the 1979–1985 and 2003–2009 periods, macro-class mobility for men increased from just above 11 percent to nearly 14 percent, a proportional increase of over 20 percent. The increase is insensitive to our counterfactual assumptions about the marginal distributions of men across occupations, suggesting that increasing exchange mobility is the main source of the trend. For women, the trends are more complex. Overall, women’s mobility between macro-classes in the nonmanual sector is higher than for men, but increases are less dramatic and non-monotonic. The steepest increases in mobility for women occur between the 1987–1993 period and the 1995–1999 period, and we see slightly declining mobility chances in the final period. We observe a smaller increase in mobility when we hold the marginal distributions fixed at their 1979–1985 levels. This suggests that a portion of the observed increase in mobility for women is due to structural change in the distribution of women across occupations within the nonmanual sector. The results indicate that the career holding power of macro-classes has declined for both sexes, but especially for men.

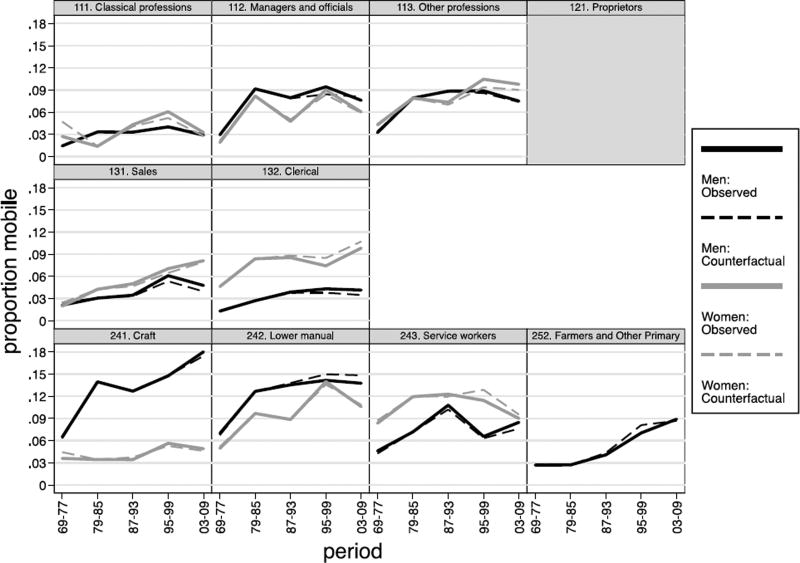

Trends in Net Meso-Class Mobility

Net meso-class mobility, which we depict in Figure 5, is also increasing for men and women. Net meso-class mobility involves switching between meso-classes within macro-classes. This includes, for example, mobility between classical professions, managerial occupations, and other professions within the professional-managerial macro-class. We omit meso-class mobility within two macro-classes, proprietors and farming, because these macro-classes contain only one meso-class.

Figure 5. Trends in Observed and Counterfactual Net Intragenerational Mobility between Meso-Classes (within Macro-Classes) by Gender.

Data source: Panel Study of Income Dynamics, 1969 to 2011.

Note: Proportion mobile is the share of persons with the given macro-class origins moving between meso-classes within those macro-classes over two-year mobility intervals within the periods indicated on the x-axis. The years correspond to the starts of the two-year intervals making up the period. The 2001 to 2003 interval is omitted because of PSID’s switch from 1970 to 2000 occupation codes in this interval. The solid lines correspond to predictions from the full model, which match the observed data. The dashed lines are based on counterfactual predictions in which the relative mobility rates are fixed at levels observed in each period, but the marginal distributions of origin and destination occupations are fixed at the numbers observed in the 1979 to 1985 period. Margins are treated separately for men and women. The “proprietors” and “primary” macro-classes each contain only one meso-class, and so net meso mobility is undefined in these cases.

For men, rates of mobility between meso-classes within macro-classes have increased across all macro-classes. Observed increases were largest in the sales/clerical macro-class, followed by the professional-managerial macro-class and then the manual macro-class. The counterfactual lines, which assume that the marginal distributions of origins and destinations are fixed at their 1979 to 1985 levels, fall only slightly below the lines for observed mobility. This result suggests that the changes in net meso-class mobility for men are primarily driven by changes in exchange mobility, not structural mobility.

We observe similar, but weaker, net meso-class mobility trends for women. Trends in the professional-managerial macro-class stand out. The observed meso-class mobility of women within professional-managerial occupations increased from nearly 9 percent to nearly 12 percent between the 1979–1985 and 2003–2009 periods. However, if the occupational structure had remained unchanged, the counterfactual results show almost no trend in mobility chances for professional-managerial women. This flat trend suggests that increasing mobility is mainly driven by changes in the distribution of women across occupations, rather than changes in exchange mobility. In the manual macro-class, mobility trends are also noticeably weaker for women. Controlling for changes in the marginal distributions, the trend was essentially null, mainly because of a downturn in the last period. Overall, the trends imply a weakening of the barriers between meso-classes for men, but more enduring barriers for women.

Trends in Net Micro-Class Mobility

If barriers between occupations are breaking down, as suggested by the patterns of mobility we have shown, we might expect the erosion of these barriers to be most apparent among occupations nested together within meso-classes. Presumably lateral mobility within meso-classes is more vulnerable to changing macro-economic conditions than is vertical mobility (both upward and downward) between meso- and macro-classes. However, our results for net micro-class mobility, displayed in Figure 6, do not entirely bear this out.

Figure 6. Trends in Observed and Counterfactual Net Intragenerational Mobility between Micro-Classes (within Meso-Classes) by Gender.

Data source: Panel Study of Income Dynamics, 1969 to 2011.

Note: Proportion mobile is the share of persons with given meso-class origins moving between micro-classes within those meso-classes over two-year mobility intervals within the periods indicated on the x-axis. The years correspond to the starts of the two-year intervals making up the period. The 2001 to 2003 interval is omitted because of PSID’s switch from 1970 to 2000 occupation codes in this interval. The solid lines correspond to predictions from the full model, which match the observed data. The dashed lines are based on counterfactual predictions in which the relative mobility rates are fixed at levels observed in each period, but the marginal distributions of origin and destination occupations are fixed at the numbers observed in the 1979 to 1985 period. Margins are treated separately for men and women. Women are omitted from the “farmers and other primary” sub-plot because of low sample sizes. The “proprietors” meso-class contains only one micro-class, and so net micro mobility is undefined in this case.

Trends in net micro-class mobility for men differ across meso-classes, but generally range from null to weakly positive. Disregarding the 1969–1977 period, we see no clear mobility trends within classical professions, managerial occupations, other professions, and service meso-classes; mild increases within sales, clerical, and lower-manual meso-classes; and larger increases in mobility in the craft (nearly 14 to 18 percent) and farming (less than 3 to nearly 9 percent) meso-classes. Changes in the marginal distributions of men across occupations are not leading us to misinterpret mobility trends: differences between the observed and counterfactual lines are negligible.

Among women we observe consistently increasing mobility only within the sales meso-class. Women in other meso-classes—including classical professions, other professions, clerical occupations, craft occupations, and lower manual occupations—endured uneven increases in mobility, including occasional mobility declines. Mobility changes in the manager meso-class are highly erratic and give the impression of no strong trend. Finally, women appear less mobile within service occupations. The close alignment of the counterfactual and observed lines indicates that these patterns reflect changes in exchange mobility.

These results suggest that whatever forces are acting to increase mobility are not inducing substantially more mobility between micro-classes within the professional, managerial, and service meso-classes, but are affecting this mobility in sales, clerical, craft, and lower manual meso-classes. This trend is suggestive of some polarization in the mobility experiences of the top and bottom of the occupational distribution, but primarily because individuals at the bottom of the distribution, especially men, are becoming more mobile, not because people at the top are becoming less mobile.

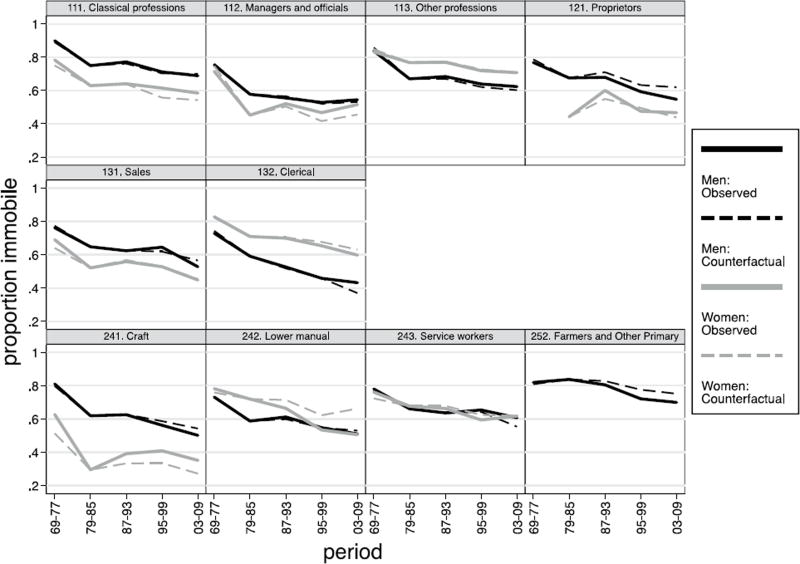

Trends in Micro-Class Immobility

Declining trends in micro-class immobility are suggested by previously discussed rising trends in mobility within and between more aggregated classes. Because there are too many micro-classes to display, we average micro-class immobility rates at their respective meso-class levels in Figure 7. Each figure is a weighted average of several micro-class immobility rates.

Figure 7. Trends in Observed and Counterfactual Micro-Class Immobility Averaged within Meso-Classes.

Data source: Panel Study of Income Dynamics, 1969 to 2011.

Note: Proportion immobile is the share of persons with the given meso-class origins who persist in their origin micro-classes over two-year mobility intervals within the periods indicated on the x-axis. The years correspond to the starts of the two-year intervals making up the period. The 2001 to 2003 interval is omitted because of PSID’s switch from 1970 to 2000 occupation codes in this interval. These immobility rates are averaged by meso-class. The solid lines correspond to predictions from the full model, which match the observed data. The dashed lines are based on counterfactual predictions in which the relative mobility rates are fixed at levels observed in each period, but the marginal distributions of origin and destination occupations are fixed at the numbers observed in the 1979 to 1985 period. Margins are treated separately for men and women. Women are omitted from the “farmers and other primary” graph because of low sample sizes that yield unreliable estimates in some periods. Likewise, very few women are observed in the “proprietors” micro-class in the 1969 to 1977 period, and so no point is drawn in this case.

Three points stand out. First, men have experienced declining micro-class immobility across all meso-classes, but there are some meso-classes, such as managers and officials, proprietors, and craft occupations, in which women show no change, or even slightly increasing immobility. Second, our results for women are more sensitive to changes in the marginal distributions, which suggests a stronger role of structural mobility for women. Finally, declines in micro-class immobility have been most stark in the clerical occupations for both men and women. Persistence in clerical micro-classes among men declined from around 60 percent in the 1979–1985 period to near 40 percent in the 2003–2009 period, and for women, from nearly 70 percent to nearly 60 percent persistence. In general, the results suggest that despite the overall rising trends in mobility, some occupations have experienced more substantial transformations in mobility chances than others, even after structural changes in occupations are accounted for.

SENSITIVITY ANALYSIS

Measurement errors and changing coding schemes

The PSID changed occupational coding procedures several times between 1968 and 2011. Even though we mapped the PSID’s occupation codes into a comparable micro-meso-macro class scheme, the changes in coding procedures introduce potential measurement errors that can lead to biased mobility estimates. Table S1 in the online supplement summarizes the coding changes. In estimating trends in gross mobility (Figure 2), we accounted for coding procedure changes using an “affine shift” method (Kambourov and Manovskii 2008). The details of this analysis are contained in the online supplement. The results suggest that potential measurement errors may bias the mobility rate estimates to some degree, but the overall trends of increasing mobility are still significant for both men and women. It is less clear if other multilevel approaches to aggregating occupations, besides the micro-meso-macro scheme we adopt here, would reveal similar changes in mobility patterns as in our log-linear analyses. The restriction to a single occupation coding scheme is a limitation of the present study that future research should scrutinize.

Effect of the two-year mobility interval

The amount of mobility we detect may depend on the time interval we use to identify moves between occupational origins and destinations (Mouw and Kalleberg 2010b). In the present study, we chose a two-year interval to maximize our usable sample, but we also experimented with four- and six-year intervals. The results for longer intervals are consistent with those presented here regarding an upward trend in mobility over time, but the degree of mobility increases and the sample size declines as a function of the increasing length of the observation interval. Tables S6 and S7 in the online supplement contain relevant fit statistics, and the results are consistent with those presented in Table 5, suggesting changing associations between occupational origins and destinations at all four aggregation levels.

Table 5.

Summary of Mobility Trends at Various Levels of Aggregation from Log-Linear Models

| Trends | ||

|---|---|---|

|

|

||

| Level of Aggregation | Overall | By Occupation |

| Manual–Nonmanual Sector Mobility | Increased | |

| Net Macro-Class Mobility | Increased | Increasing mobility in the nonmanual sector, not in the manual sector. |

| Net Meso-Class Mobility | Increased | Increasing mobility within macro-classes, especially for men in professional-managerial and sales-clerical macro-classes. |

| Net Micro-Class Mobility | Mixed | Stable in professional, managerial, and service meso-classes, increasing mobility elsewhere. |

| Micro-Class Immobility | Declined | Declining immobility, especially in clerical micro-classes, but no change for women in some meso-classes. |

Composition effects of demographic trends

We suggested that demographic trends, including aging and educational upgrading, might be responsible for changing mobility. Indeed, descriptive statistics for the PSID reweighted sample indicate a mild aging of the working population from the 1980s onward (Table S4 in the online supplement). To test the sensitivity of our results to the age definition of the analytic sample (age 25 to 64), we replicated our analyses by including younger workers (respondents age 18 to 24; Table S8 in the online supplement) and excluding older workers (respondents older than 54; Table S9 in the online supplement). To some degree, we can also explicitly examine the effects of changing labor force demographics using multinomial logistic regression models (Breen 1994). The multinomial models are roughly equivalent to our topological log-linear models but account for individual characteristics—such as age, education, gender, and race—that may influence the likelihood of occupational immobility. Using these models, we find qualitatively similar trends in mobility at the micro-class, meso-class, macro-class, and sectoral levels (results available upon request).

DISCUSSION

Our analysis shows increasing trends in intragenerational occupational mobility that emerge most strongly around 1990. The trends do not appear to result simply from changes in the relative numbers of workers in each occupation. Whether we speak of men or women, routine or nonroutine occupations, or the bottom, middle, or top of the occupational distribution, intragenerational occupational exchange mobility has generally been on the rise. Some occupations have resisted the trend more than others, but very few occupations have defied it. We summarize these major findings in Table 5. These findings offer some hints about which macro-social factors—labor force aging, increasing educational attainment, computerization, de-unionization, precarious labor practices, or occupational gender desegregation—are the most likely sources of change, suggesting limitations of the present study and directions for future research.

Our results suggest that we cannot easily pin changes in mobility on changes in the demographic composition of the labor force. The rising trends in mobility defy expectations, derived from micro-economic models, that labor force aging and increasing educational attainment would reduce mobility. We tentatively dismiss demographic change as driving the changes in mobility, but we must note that labor force–wide levels of mobility may result from more than a simplistic aggregating-up of individual-level changes in mobility propensities. For example, if the mobility of younger workers depends on the retirement of older workers, then labor force aging may lead to greater mobility under some circumstances. Our lack of attention to complex interdependencies between older and younger workers, or between workers with similar levels of educational credentials, is a limitation that future research should seek to remedy.