Abstract

Background:

There is limited literature evaluating generational change in the physician workforce and the adjustments required of practices, practitioners and the health care system as a whole. The purpose of this study was to explore rural practitioners' experiences of their current contexts relevant to recruitment and retention and to determine how practices are responding to changing aspirations of new practitioners.

Methods:

We used qualitative methods. Participants were selected to ensure diversity of career stage. Semistructured interviews conducted with 39 physicians, 2 nurses and 1 practice administrator from rural northwestern Canada (British Columbia, the Yukon Territory and the Northwest Territories) between June and October 2016 sought participants' views on research, training, recruitment and retention in the rural setting. Interviews lasted 30-50 minutes with the exception of 4 group interviews (45-90 min). Interviews were then conducted with 4 rural practitioners on Vancouver Island to confirm emerging themes. The interviews were recorded and analyzed interpretively.

Results:

Three themes were identified that showed the interplay among practitioners, patients and resources within a rural health environment: 1) scope of practice and the changing concept of generalism, 2) connectivity and relationships and 3) divergent career aspirations. Within these themes, generational differences between early-career physicians and established practitioners influenced changes under way in rural practice in terms of adapting the practice environment to enhance recruitment and retention.

Interpretation:

Some rural practices are beginning to adapt in ways that reflect changing generational aspirations. Specifically, they provide environments that support and nurture young physicians, encourage collaborative working and include flexible working arrangements, with varying support and financial models. Rural practices that were responsive to changing aspirations reported success in recruitment and retention.

There continues to be an inequitable distribution of physicians in rural and remote areas in Canada. Whereas the 2016 Canadian census indicated that 16.8% of the population lived in rural areas,1 a 2015 assessment of physician distribution showed that only 8.2% of Canadian physicians were based outside of urban centres.2 In addition, urban centres had roughly equal numbers of family physicians and specialists, but only 14% of rural physicians were designated as specialists.2

Current evidence suggests that rural upbringing and exposure to rural practice during training can encourage interest in rural careers.3-7 Character traits such as novelty seeking and low harm avoidance have been associated with physician interest in rural practice.8 In attempts to increase recruitment of physicians to rural areas, some medical schools have sought to identify students with rural affinity during the admissions process,9 and others have noted positive impacts on the rural workforce through creating a rural generalist training pathway.10 Rural-oriented medical programs have been created in Canada11,12 and Australia.13,14 There have been examples of success from these efforts; however, many rural areas struggle to recruit and retain enough physicians and to provide equitable access to health care.

Those previous studies assumed a stable state with respect to rural work environments. There has been some consideration of the changes required of the medical educational system in response to the new generation of physicians,15 yet there is limited literature evaluating generational change in the physician workforce and the adjustments required of practices, practitioners and the health care system as a whole. The evidence suggests some commonalities across generations among physicians who choose rural practice.3-8We aimed to explore rural practitioners' experiences to understand the adaptations, successes and challenges influencing recruitment and retention in rural health care to answer the question of how practices are responding to the influence of the incoming generation of practitioners.

Methods

Setting and design

This was a qualitative interview study conducted in rural practices in northwestern Canada. The first author was the regional associate dean for the Northern Medical Program of the University of British Columbia Faculty of Medicine from 2003 to 2011 and then executive associate dean, education from 2011 to 2016 and is known throughout northern British Columbia. Some participants were former students of the Northern Medical Program and some had been met previously through community visits; most had not been met before. The study design took this into account and used an interpretive approach, related to hermeneutics,16,17 which acknowledges that the researcher comes with experiences and assumptions and that the interpretation builds on and refines or changes these. Also, in driving to the communities (about 10 000 km overall), the first author directly experienced the challenges of geography and came to a new appreciation of geographic influences on rural practice.18

Sample

We invited practitioners in rural and remote communities in northwestern Canada to participate in a semistructured interview to discuss their views on research, training, recruitment, retention and other issues they deemed relevant in the rural setting.

We sought a purposive sample from practices throughout northern BC, the Yukon Territory and the Northwest Territories. Medical directors and physician leads sent out a letter of invitation to practitioners, requesting that those interested contact the first author directly. All those who responded were interviewed by the first author. In 2 larger communities, the medical directors organized group interviews, and in other communities, the practice team elected to attend the interview, which meant that the sample contained nonphysicians. The second author recruited a confirmatory cohort using convenience sampling in another health authority on Vancouver Island to test emerging themes.

Data collection

We developed an interview guide (Appendix 1, available at www.cmajopen.ca/content/5/3/E710/suppl/DC1) based on a review of the literature and discussion with rural physicians. The same interview guide was used for group interviews, which were conducted as broad conversations, not focus groups. Participants were interviewed between June and October 2016 at a place of their choosing in their practice community, with the exception of 3 people interviewed by Skype or telephone. Individual interviews lasted 30-50 minutes, and the group interviews, 45-90 minutes. Disconfirming evidence was sought within the interviews and was enhanced by the diversity of participants.

The first author kept field notes and reflections about visits to the communities and tours of the health care facilities, and had informal conversations with staff during these visits. All interviews were recorded digitally and transcribed. In 2 instances there were issues with the digital recordings, and summaries and field notes were created for analysis.

Data analysis

In keeping with qualitative research approaches,17,19 we analyzed the data as data collection was ongoing and adapted subsequent interviews to explore emerging themes. All transcripts and field notes were read, coded with the use of NVivo (QSR International) and analyzed by both authors independently. Both authors kept reflective notes during this phase. Analysis continued until the authors agreed that no new themes or codes could be identified. A summary of findings and emerging themes was sent to all participants, and their feedback was incorporated into the continuing analyses. On completion of data collection, the 2 sets of themes were found to be similar but were labelled differently. A single set of themes was agreed on, and the data were further compared with these themes. At the completion of analysis and interpretation, the second author conducted 4 individual interviews with rural practitioners on Vancouver Island to test the resonance of the themes.

Ethics approval

This study received harmonized ethics approval from the University of British Columbia Behavioral Research Ethics Board and the Northern Health Ethics Committee.

Results

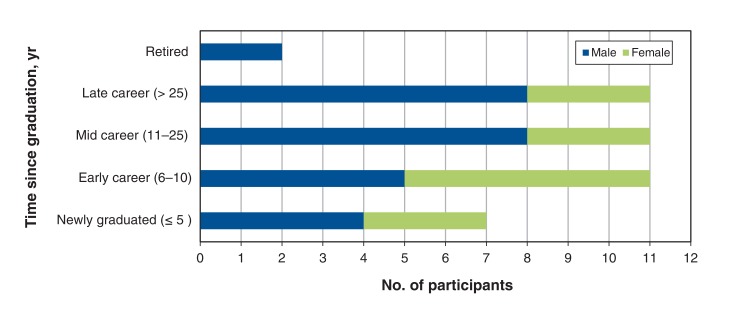

Interviews were conducted with 42 participants (35 family physicians, 4 specialist physicians [without previous family physician training], 2 nurses and 1 practice administrator) from rural northwestern Canada. The first author conducted 17 individual interviews and 2 interviews with 2 people, and interviewed 25 participants in 4 group settings. Two people participated in both a group interview and an individual interview. The 4 practitioners interviewed on Vancouver Island were 3 physicians and 1 nurse. Participants ranged in career stage from their first year of practice to recently retired (Figure 1). The nonphysicians all had valuable contributions to make, particularly on physician recruitment and retention, and their observations of new physicians entering rural practice. Physicians were remunerated by fee-for-service arrangements, alternative payment plans (income guarantee and contract salary arrangements) and return-of-service obligations.

Figure 1.

Participants by time since graduation and sex.

Identified themes

Three major themes emerged from the data, all of which contained intergenerational dynamics: 1) scope of practice and the changing concept of generalism, 2) culture, connectivity and relationships and 3) divergent career aspirations. The quotes in the boxes are illustrative of the many perspectives that came to make a theme.

Scope of practice and the changing concept of generalism (Box 1)

Box 1:

Scope of practice and the changing concept of generalism

Excitement of rural medicine: "I like practising rural medicine because of the spectrum. I like the action, I'm a bit of an adrenaline junkie when it comes to, you know, working under stress. I like that. I like the acute care. I like that I am it, I'm the person who will make the decisions when the critical care comes." - Family physician, new to practice

Importance of not restricting scope: "I think to keep a physician motivated in a rural area, you need to be a generalist. Otherwise you're going to sit in Edmonton in the middle of the city and just do office work. And there's a big difference between being an office physician and being a rural physician." - Family physician, late career

Considerations with generalist accreditation: "We have basically anything that occurs in the big centres, not as often as in a bigger centre, but we have everything that comes through the door we deal with. And that is exciting and stressful and challenging sometimes with the limited resources and equipment as well." - Family physician, new to practice

Disproportionate impact of policies developed in an urban environment: "The protocols have their place, and they can be helpful, but I think sometimes big hospital protocols are extrapolated out to rural communities and places where they just don't work. You know, it's a totally different setting here. I haven't had huge issues, I mean sometimes it can be something as simple as, well, recently there's been some protocol shift in terms of sterilization and with our autoclave in particular, they want to do away with it. So they want us to use just disposable equipment, which I think is pretty awful, overall. … Based on hospital protocol or what they think is an acceptable sterilization technique is, we'll be stuck with plastic utensils to try and do things." - Family physician, early career

Interactions with specialists: "I think the specialists, well, not all of them, but I think most of them sort of appreciate where we are. Sometimes we run into situations where we have newer docs who don't realize sort of how resource poor it can be in a rural setting." - Family physician, early career

Burden of negative interactions with urban-based colleagues: "I used to see it as my issues always when I was calling south and someone was mean and, you know, you'd be kind of bending over backwards to give the story in the right order and not upset them." - Family physician, new to practice

Administrative challenges: "People are more stressed about transferring the patients than managing the [myocardial infarction] or managing the polytrauma or whatever it might be." - Family physician, late career

Impact on recruitment: "What I'm looking for is a community where I can sort of grow and also a community that has a need and not wanting to be stuck in a family practice clinic and that's all I do. I enjoy doing the emergency and the obstetrics. So it's sort of doing the [general practitioner] thing and having a multidisciplinary practice." - Family physician, new to practice

Impact on retention: "I think rural practice is certainly my passion. I think I'd probably shrivel up and die in a walk-in clinic in Vancouver, so, yeah, I do like what I do and I like to share it, too." - Family physician, new to practice

Participants spoke positively about the breadth of rural practice, the opportunity to solve complex issues and the challenge of the unexpected. They considered generalism to be the capacity to deal with any condition that presented, with emergency skills or, for some, extended skills such as obstetrics, oncology, general practice surgery or anesthesia. The data indicated that generalism as a concept is evolving, with some of the extended skills of generalism being vested in a team rather than within 1 person; this increases the importance of supportive, accessible colleagues and specialty services. The participants hesitated to endorse formal certification of generalism and extended skills, as the needs of each community are different and the interests of physicians change over their career.

Many participants provided examples of policies or protocols developed in fully resourced urban environments that had a disproportionate effect on rural communities lacking a full complement of specialists, equipment and/or support staff. In some instances, the tone and tenor of specialist consultations and interactions with urban-based colleagues were less than desirable. These negative experiences, as well as administrative challenges, appeared to be rooted in a limited understanding of rural health care delivery on the part of specialist physicians and services. This was frustrating for rural physicians, who are acutely aware of the resource limitations of their communities. Of major concern were difficulties arranging patient transport to larger centres. Many participants commented strongly on the importance of ensuring that best practices and protocols are scalable to each rural practice context.

Some participants spoke of limiting the scope of practice because of lack of support, resources or confidence; this was cited primarily with regard to new physicians, both by them and of them. Despite the challenges, participants commented that good specialist relationships do exist, and many newly graduated and early-career physicians spoke of networks formed through training that served them well in their transition to rural practice. Where specialists were part of or visited communities, or where video links connected specialists, family physicians and patients, an added supportive network existed to attract and retain rural physicians.

Culture, connectivity and relationships (Box 2)

Box 2: Culture, connectivity and relationships.

Impact of rural practice culture: "I haven't found anywhere like it, and I think that [culture] is a big part of it for sure. And even small towns locuming around, you know, some small towns, you'll have colleagues that are just so supportive, local colleagues, who say 'Call me in a pinch, any problems, let me know.' And other places in which that is not the case for whatever reason. And it makes a huge difference to practice." - Family physician, early career

Collegial support: "So as far as supports go, that's one thing that I find different here compared to a lot of places ... I know if at 3 in the morning I was really stuck, I could call anybody in town and get help. ... I don't have to keep it to [my clinic], we all support and help each other, and there have been times when I've struggled with things and had to call someone in or get advice or things like that. So I think as far as collegiality despite being short-staffed, despite being from different clinics, I think we have pretty good collegiality for that." - Family physician, new to practice

Barriers to support: "The team here, it's a very diverse ... and overworked team. We're short-staffed, so ... I didn't feel like I had kind of a mentorship and support where I could go and just chat about things, because people are just overworked and busy and just trying to keep afloat." - Family physician, new to practice

Flexibility in scheduling: "People really appreciate the flexibility of coming into a site like this one when they can take, assume a fraction of a full-time equivalent. To be honest, in the way of my recruitment strategy over the past few years, I haven't seen many physicians who want to take on a full-time right off the bat, so what we get here, and I think why we're so successful in the way of recruitment, is a lot of young locums who are coming right out of residency working with us, checking the site out, and a lot of them like to float around and do rural locums in different communities, so this sort of allows them that flexibility to do that. Yeah, so, it's been good, I think, you know,as opposed to committing to a full-time and just being here sort of nonstop." - Family physician, early career

Supportive culture differentiating itself: "In that context, the younger generation usually comes in and says 'But I am not so competent, and I don't do so well with obstetrics,' and then we tell them 'Okay, but we'll take you through that. We will make sure that we support and help you. We've got a mentor program … that we've done before that helped [other physicians] to a level that they were very comfortable and gained their privileges.' So in the emergency [department], we have a support system that, even if there's no [official] second on-call … there's always a second on-call available. And so that gives that support system, and so what I've seen now with the first resident, when he left here, he sat me down, he says 'My mind is blown. I did not expect this in a rural, underserviced area without any supports to experience this kind of support.'" - Family physician, late career

Developing confidence in rural environments: "I think the competence is there but the confidence is not. That's something I see as a big challenge with the new grads coming out is that, even if they are capable and able, they don't feel capable and able. So we do need to look at supporting them in that confidence piece." - Family physician, late career

Influence of training on transition to rural practice: "I do feel like my residency training prepared me well for [rural practice], but ultimately it's this process that we all go through in the first few years, and it's hard to go through, and I don't think actually that more training would make it better. I think it's really just a, it's hard to be the [most responsible physician], and the only way you really get good at that is by experience with adequate support, ideally." - Family physician, early career

Importance of mentorship embedded in community: "Mentorship [is critically important] for new arrivals in practice, whether they are experienced old hands in medicine or brand-new grads. Being mentored by someone experienced with the community, who can help the new arrival to develop a deep appreciation for the community and all its 'weirdness,' is often helpful to the healthy practice ecosystem, but also to the community itself." - Family physician, retired

Collegial support in early years of practice: "This is really important for any new doctor coming into the practice, especially a strange place and especially a multiracial community and the rest of it, coming from a different country especially, that support is very key. Because the positive reinforcement is what keeps you going when every other thing goes down. And I'm so happy, like, [here] I have colleagues who support me, there were times they didn't know, but they gave me a positive reinforcement. I didn't say this back to them, that kept me going and kept me [knowing] that, yeah, I can actually survive here." - Family physician, mid career

Participants revealed that the culture of a rural practice is a major determinant of the ability of communities to recruit and retain physicians. Practice cultures were influenced by the level of collegial support and mentorship, integration within the broader interdisciplinary health care team and relationships with the community. Factors that helped establish this supportive culture were reductions in administrative burdens, the development of trust between colleagues and a strong relationship between clinicians and the local health authority. Participants from communities with a supportive culture differentiated themselves positively from those without and noted a positive effect on recruitment and retention.

Established physicians mentioned that new graduates are highly skilled but often need to gain confidence in rural environments, with those trained in low-resource environments through residency or clerkships adjusting more easily. Newer physicians noted that collegial support in the early years of practice was key to building confidence and was facilitated by the availability of experienced people, embedded in the community, who were willing and able to provide early mentorship and reinforcement. This component allowed new recruits to learn about the community itself and form connections to the multidisciplinary team, health authorities and referral centres. Access to telehealth and connectivity in general emerged as important ways of accessing information and enabling relationships with specialists, members of the health care team near and far, and patients. Ultimately, established physicians felt that the newer generation of physicians were competent to work in rural areas but required on-site support and connectivity to develop confidence, which, in turn, determined comfort and success in practice.

Divergent career aspirations (Box 3)

Box 3: Divergent career aspirations.

Different practice styles of new physicians: "I think we have a different approach ... that's drilled into us in family medicine residency and med school around patient-centred care ... which takes a lot more time than a more paternalistic, traditional form of medicine, right. [Compared] with the doctor who had been there for 20 years, it took us a lot more time to see the same patients than it took him, and that was because we talked more, or maybe we were a bit more thorough, maybe we took a longer history. Part of that would've been because we were younger and maybe less efficient, but part of it was because I do think we have a different approach as well, we're taught a different approach these days." - Family physician, early career

Patient rosters: "So what we're seeing is that as an average we used to have practice panels of, I would say, about 1800 to 2400 per doc. But some of our new recruits, the new docs that have been here now for a year or 2 or longer and the newest ones, we're looking currently at practice panels of 800 to 1200. So even though you're getting new physicians, your unattachment pool is actually growing, so the net effect of that is that we need higher numbers of docs to do the same amount of work." - Family physician, mid career

Not generating sufficient billings: "An interesting thing that I see, and we need to back it up a little bit, is when you say you know the guy looked after 3000 patients and he made this much money. The young people coming in want to look after 800, and many of them want to make almost that same amount of money. But they only want to look after 800. And so that's a little bit of a disconnect as well. So finding a way to actually build some reality into younger physicians coming in. They want to work [fewer] hours, less hard but the same kind of income." - Family physician, late career

Different approach to medical careers: "I think this will be the new model. I think things will really change, and it was the old generation, and I have a lot of respect for older doctors. I mean, they've worked very hard, but I think there's a big shift, people demanding an adequate lifestyle. They're no longer willing to sort of sacrifice everything for medicine, and I respect that, too." - Family physician, early career

Valuing flexibility in scheduling: "We had to become more flexible with how we allotted our positions, right, and we found out very quickly that to maintain full-time positions, although it creates the best continuity, is not really a way forward in this sort of new environment that we're in." - Family physician, mid career

Shared accountability and integration of care: "Ultimately it is a shared practice, and when I'm away, someone's checking my results and dealing with things and they're not a locum that I've handpicked, and so there's a lot of trust required and knowing that everybody is kind of on the same page in general. … I always think about narcotic prescriptions because I had some horrible experiences with a locum where you're just being asked to refill things all the time that you don't feel comfortable with, but even simple things like not using statins for primary prevention or some ways that we're oriented in how we provide care. … Especially the longer I'm in practice, I have stronger and stronger ideas about how I like to do things for better or for worse. I wouldn't want to share a practice with people who were really divergent in their values. I think that would be really hard, so we're lucky to have [shared values here]." - Family physician, early career

Working hard but working differently:Dr. A: "I think our sort of cohort of doctors is really moving in the direction of doctoring being a job and not a life, which we certainly are trying to maintain as well. So, certainly, having the flexibility to not always be on-call and to not be working 100 hours a week is important."Dr. B: "You know, all of us know through training that 100-hour weeks are something you're going to deal with one way or another, it's just not being every week."Dr. A: "Yeah, yeah, we do them, but just not all the time." - Family physicians, new to practice

Importance of work-life balance to prevent burn-out: "I definitely think there is a change in the kind of way people want to do things. I'm really wary of my own kind of mindfulness of the youth of today, you know, 'When we were young,' and I think that's a problem we deal with as human beings all the time, is we always attribute things to a generational thing that may not even be a generational thing. It just may be kind of the lens that we're looking at it through. We're looking back and they're looking forward, and so, but I do see kind of work-life balance being more important and overtly more important. So, and I think that's really important, and I think there's a lot of value in that around sustainability, because you have a bit of a pattern of a whole bunch of people going to rural communities burning out, a lot of them, and a few of us sticking it out. And maybe part of the reason for it is we've been a bit more intentional around the work-life balance. Maybe part of it is we mentally adjusted somehow." - Family physician, late career

Participants expressed both positive and negative opinions about how the practice philosophy of new physicians contrasts with the traditional expectations of a rural physician. Some established physicians noted that newer physicians were not taking a full roster of patients, had longer appointment times, did not generate sufficient billings and/or preferred non-fee-for-service funding arrangements. In contrast, other established physicians noted the high quality of care provided through patient-centred and comprehensively documented approaches. Practices that encouraged shared accountability and integration of care by adapting their environment and cost-sharing models reported positive effects on culture, collegiality, recruitment and retention.

What presented as divergent practice styles during initial interviews became more clearly generational in nature, with newer physicians approaching their medical careers differently from established physicians. The former valued flexibility over scheduling and working arrangements that change over time; prioritizing work-life blend over remuneration; team-based, patient-centred care; and using technology to ensure information transfer. Some established practitioners viewed new recruits as having a sense of entitlement and being unwilling to work the same kind of hours as they had, thus necessitating more physicians to serve the same population. The propensity for burnout in rural health care was noted across the spectrum; however, newer physicians seemed more comfortable setting boundaries to prevent it. Overall, the data indicated that newer physicians are working hard but working differently.

Interpretation

This study of rural physicians showed evidence that generational change is affecting the health care system. The findings highlight the importance of understanding changing generational aspirations in order to support recruitment and retention to rural communities in the context of the changing health care system. The new generation of physicians are seeking practice environments that are collegial and supportive, have well-developed internal and external relationships, and allow flexibility in practice and financial arrangements. The Strauss-Howe generational theory20 gives us one way of considering the impact of these changes, a theory further supported by the NextGen global generational study of over 44 000 employees commissioned by PwC (PricewaterhouseCoopers) in direct response to retention issues with "millennials" (those born between 1982 and 2004).21 In the PwC cohort, a higher proportion of millennials than previous generations valued work-life balance over greater compensation, a cohesive team-based culture with a sense of community, diversity of career experiences, and being supported and appreciated - all issues that emerged from our analysis and that affect the broader workforce as a whole.22 As millennial physicians are only just now entering practice owing to increased length of education, the experiences of other professions with recruitment and retention of millennials could hold the key to understanding the incoming generation of physicians.

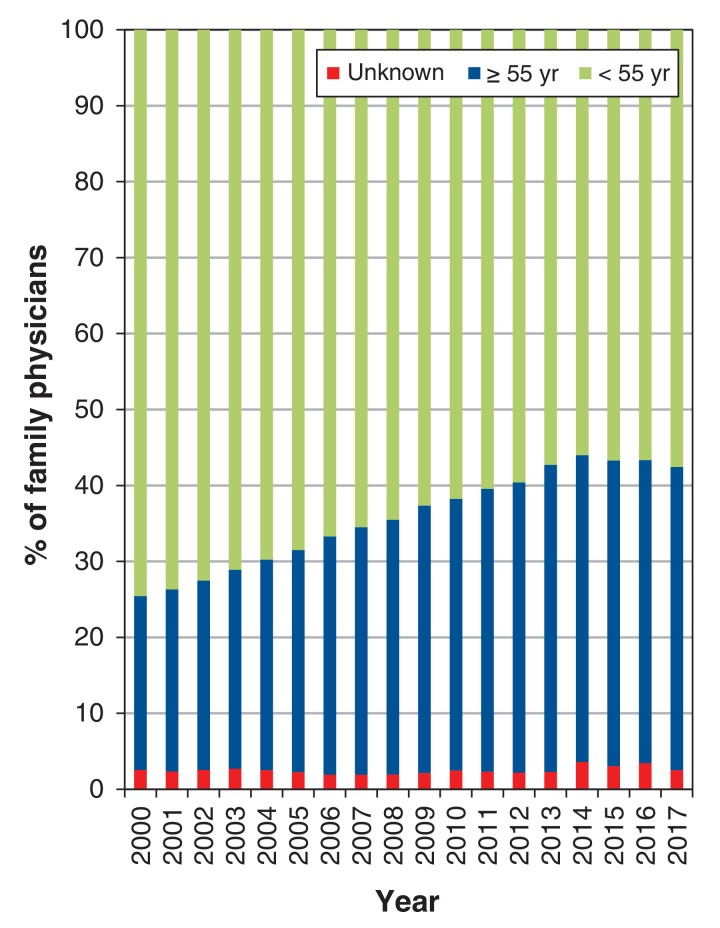

Renewal of the rural physician workforce will also require attention to shifting demographic characteristics. Adaptations will be needed, as family physicians, who account for 86% of rural practitioners in Canada, are aging steadily - 23% were aged 55 years or more in 2000, compared to 40% in 201723 (Figure 2) - and will be replaced by a new generation of physicians.

Figure 2.

Age distribution of family physicians in Canada, 2000-2017.

Although we found no research applying multigenerational understanding to rural practices, generational theory has been used to gain insight and shape interventions in academic medicine to address issues very similar to those being faced in rural health care.24 A generational forecasting model and specific programs were developed to address differences in work-life balance, compensation, team versus solo work and diversity. Interventions included formalized succession planning programs, financial support programs leveraging the success of "baby boomers" to provide opportunities for the next generation, programs to develop leadership and mentorship skills, and an emphasis on cultivating a team-based culture that facilitates connectivity and collaboration,25 all similar to interventions observed in our study. Given their clinical workloads, our participants reported little appetite for practices to engage in research, and research did not emerge as an important theme with the exception that rural practitioners want to ensure that there is relevant research to advocate for rural health. Our data did not show sex differences, and the relevance of connection to a rural "place" did not emerge other than through the importance of community relationships, which has been reported by other investigators.26

Strengths and limitations

Separate analysis by the 2 authors strengthened the findings, as perspectives were brought to bear independently, and increased the sensitivity of the findings. The themes were commonly held across diverse contexts and practitioners, which strengthened the authenticity and transferability of the findings. This study represents the experiences of practitioners in rural northwestern Canada but may be relevant to other practitioners and transferrable to other practice settings.,

Limitations include partial failure of digital recording on 2 occasions, with subsequent use of field notes for analysis. However, field notes were made immediately after the interviews and resonated well with the main data. Skype and telephone interviews were digitally recorded, and their content was not found to be inferior to data obtained by in-person interview. However, there is a definite advantage to interviewing people in their own settings in that one can develop an appreciation for their contexts. This limitation was mitigated by the first author's having visited all the communities in the study.

Conclusion

Rural medicine remains exciting for many physicians, with collegial relationships, in-house mentorship and educational support found to improve confidence in its wide scope of practice. Academic settings prepare physicians to work as part of a team and emphasize patient-centred approaches, but not all rural practice environments incorporate these ideas. Practices can allow flexibility for physicians in their work arrangements, yet there is limited flexibility in physician compensation and how clinics are run and funded. This creates a disconnect for new physicians, who are trained differently only to graduate into a system that requires them to leave a large part of what they learned behind. The transition from residency program to rural practice is supported by providing easy access to advice and addressing the tension between established practitioners and the aspirations of new physicians. Experienced practitioners have a critical role to play in helping new practitioners understand the unique features of their communities. How to develop healthy supportive practice environments is an area for further research. Another potential area of research is whether there are sex differences as opposed to generational differences in aspirations.

Established physicians and health authorities seeking to enhance rural recruitment and retention need to consider the practice environment desired by new recruits in terms of internal and external relationships, the flexibility of work and compensation arrangements, team-based care with comprehensive shared information systems, and access to rapid support through specialist and telehealth networks. The willingness and ability to respond to shifting generational aspirations has a direct impact on the health of rural practices, and our results indicate that communities that embrace this reality will more readily recruit and retain physicians.

Supplemental information

For reviewer comments and the original submission of this manuscript, please see www.cmajopen.ca/content/5/3/E710/suppl/DC1.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge administrative help from the University of British Columbia Department of Family Practice, Northern Health and the Rural Coordination Centre of BC. They are grateful to Martha MacLeod, Northern Health - UNBC Knowledge Mobilization Research Chair and School of Nursing, University of Northern British Columbia and Kevin Eva, Centre for Health Education Scholarship, University of British Columbia for their comments on an early draft of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Bollman R. 2016 census update: update of rural and small town population; 2017. [accessed 2017 July 31]. Available http://datacat.cbrdi.ca/resource/update-rural-and-small-town-population-2016.

- 2.Supply distribution and migration of physicians in Canada, 2015: data tables. Ottawa: Canadian Institute for Health Information; 2015. [accessed 2016 Oct. 15]. Available https://secure.cihi.ca/estore/productFamily.htm?pf=PFC3269&lang=en&media=0.

- 3.Viscomi M, Larkins S, Gupta TS. Recruitment and retention of general practitioners in rural Canada and Australia: a review of the literature. Can J Rural Med. 2013;18:13–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Verma P, Ford JA, Stuart A, et al. A systematic review of strategies to recruit and retain primary care doctors. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16:126. doi: 10.1186/s12913-016-1370-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grobler L, Marais BJ, Mabunda S. Interventions for increasing the proportion of health professionals practising in rural and other underserved areas. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015:CD005314. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005314.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Increasing access to health workers in remote and rural areas through improved retention: global policy recommendations. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Soles TL, Wilson RC, Oandasan IF. Family medicine education in rural communities as a health service intervention supporting recruitment and retention of physicians: advancing rural family medicine: the Canadian Collaborative Taskforce. Can Fam Physician. 2017;63:32–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eley D, Young L, Przybeck TR. Exploring the temperament and character traits of rural and urban doctors. J Rural Health. 2009;25:43–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2009.00197.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bates J, Frinton V, Voaklander D. A new evaluation tool for admissions. Med Educ. 2005;39:1146. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2005.02308.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Woolley T, Sen Gupta T, Murray R. James Cook University's decentralised medical training model: an important part of the rural workforce pipeline in northern Australia. Rural Remote Health. 2016;16:3611. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Strasser S, Strasser RP. The Northern Ontario School of Medicine: a long-term strategy to enhance the rural medical workforce. Cah Sociol Demogr Med. 2007;47:469–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Snadden D, Bates J. Expanding undergraduate medical education in British Columbia: a distributed campus model. CMAJ. 2005;173:589–90. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.050439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hays R. Rural initiatives at the JCU School of Medicine: a vertically integrated regional/rural/remote medical provider. Aust J Rural Health. 2001;9(Suppl 1):S2–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Evaluation of the University Departments of Rural Health Program and the Rural Clinical Schools Program. Canberra (AU): Australian Government Department of Health; 2009. [accessed 2017 Mar. 4]. Available www.health.gov.au/internet/publications/publishing.nsf/Content/work-pubs-eval-udrh-toc~work-pubs-eval-udrh-5.

- 15.Boysen PG. 2ndDaste L, Northern T. Multigenerational challenges and the future of graduate medical education. Ochsner J. 2016;16:101–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gadamer HG, Weinsheimer J, Marshall DG. Truth and method. 2nd revised ed. New York: Bloomsbury Academic; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moules NJ, McCaffrey G, Field JC, et al. Conducting hermeneutic research: from philosophy to practice. New York: Peter Laing; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dubé TV, Schinke RJ, Strasser R, et al. Interviewing in situ: employing the guided walk as a dynamic form of qualitative inquiry. Med Educ. 2014;48:1092–100. doi: 10.1111/medu.12532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patton MQ. Qualitative evaluation and research methods: integrating theory and practice. 4th ed. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Strauss W, Howe N. Generations: the history of America's future, 1548 to 2069. New York: William Morrow & Co.; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Finn D, Donovan A. PwC's NextGen: a global generational study. Los Angeles: University of Southern California; 2013. [accessed 2017 Jan. 15]. Available www.pwc.com/gx/en/hr-management-services/publications/assets/pwc-nextgen.pdf.

- 22.Howe N, Strauss W. The next 20 years: how customer and workforce attitudes will evolve. Harv Bus Rev. 2007;85:41–52, 191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Number of physicians by specialty and age, Canada 2017. Ottawa: Canadian Medical Association; 2017. [accessed 2017 May 30]. Available https://www.cma.ca/Assets/assets-library/document/en/advocacy/01-physicians-by-specialty-province-e.pdf.

- 24.Howell LP, Servis G, Bonham A. Multigenerational challenges in academic medicine: UCDavis's responses. Acad Med. 2005;80:527–32. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200506000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Howell LP, Joad JP, Callahan E, et al. Generational forecasting in academic medicine: a unique method of planning for success in the next two decades. Acad Med. 2009;84:985–93. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181acf408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kearns R, Myers J, Adair V, et al. What makes 'place' attractive to overseas-trained doctors in rural New Zealand? Health Soc Care Community. 2006;14:532–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2006.00641.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.